ALTA Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

ALTA Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 5 July 2009

Officers’ Duties:

Are We Keeping Up With the Changes?

Professor Michael Adams FCIS[1], School of Law, University of Western Sydney

Over the last decade corporate governance and in particular the role of officers’ duties has closely come under the microscope of the courts in all jurisdictions. No director, company secretary, general counsel or chief financial officer could argue they did not know what is expected of them in terms of the basic legal duties owed to the company. Recently, the Royal Commissioner, the Hon Justice Neville Owen[2], in May 2008, re-stated the need for a commitment to education on the fiduciary principle and for greater professionalism in governance.[3] Also, in May 2008, Mr Alan Cameron, former chairman of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) stated that lawyers and directors could still not believe that through the common law an additional higher duty had been imposed upon the chair of a finance committee because of his or her expertise.[4]

This article re-caps on some earlier published work on directors and officers’ duties in Keeping Good Companies by the author[5] and brings those articles up-to-date with the latest decisions. The Federal Minister responsible for developments in this area of law has noted that a review into the Safe Harbour Rule (also known as the Business Judgment Rule[6] in the Review of Sanctions in Corporate Law (2007) paper, does not expect any quick changes at the moment.[7]

It is fair to say that any lay person might feel confused over the state of Australian corporate law. This is sharply brought into focus for directors and company officers that have an increasingly high expectations imposed upon them by a number of stakeholders.

Before 1991, Australia had a state-based corporate law scheme, as the Australian Constitution provided that commercial law and in particular the regulation of companies was a state-matter. It will be called that the Commonwealth of Australia through the Federal Government, proposed to shift corporate law to a single act of parliament in 1989, which became effective law in 1991. Sir Anthony Mason CJ[8] wrote in 1992 that “Oscar Wilde described fox-hunting as “the unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable”. Oscar Wilde, the supreme stylist, would have regarded our modern Corporations Law not only as uneatable but also as indigestible and incomprehensible.”[9]

By 2008 one would hope the world of corporate law and regulation would be so much simpler! Particular as Australia has had a Simplification Task Force and a Corporate Law Economic Reform Program (CLERP) for over a decade! But unfortunately, as stated by Justice Graham in Ku v Song in late 2007, “Whoever coined the expression “as clear as mud” must have been slaving over the extraordinary, and unnecessarily complex provisions of the Corporations Act and the Corporations Regulations....Gaining an understanding of the relevant law on this subject [share transfers] back in 1961 involved a five minute exercise...Today, it requires hours of study, reference to numerous sections and regulations...Why the law had to be expressed in such an obscure way beggars belief.”[10]

If there is ever a reason for all directors and officers to understand their legal duties, it is the fear of litigation and in particular, a criminal prosecution resulting in a criminal conviction and potentially a gaol sentence. The most recent ASIC annual report[11] shows that the regulator spent approximately 50 per cent ($135 million) of its budget on enforcement. ASIC had 21 criminals gaoled; it further had 110 people removed from directing companies; took another 76 civil proceedings, which resulted in more $102 million in recoveries, compensation orders and frozen assets. Over the last ten years my research has shown that approximately 250 officers have been sent to gaol in that period (1997-2007) and that this averages at about 25 directors per year. The maximum sentence imposed in this period was 12 years and the minimum is one month. The average sentence has changed over the period from approximately two years to three years and two months. These numbers only relate to criminal convictions under the Corporations Act and ignore other Crimes Act cases and under the Trade Practices Act or tax legislation.

Officers and Directors’ Duties in Australia

A quick re-cap of the various definitions and issues relating to officers and directors is required as a refresher of the legal duties.[12] Over the last decade there have been a number of different statutory definitions of an officer. However, following the HIH Royal Commission, Justice Neville Owen recommended that there should be one definition. This was implemented as part of the CLERP 9 reforms from 1 July 2004 and is found in the ‘dictionary’ found in section 9 Corporations Act 2001. These meanings are applied unless there is a contrary intention stated in another part of the legislation.

Prior to March 2000, the term ‘executive’ was used, but this caused difficulty with definitions and application. This has been removed and replaced with the concept of a person who makes decisions that affect a substantial part of the corporation’s business or has the capacity to significantly affect its financial standing. The use of the word ‘person’ follows the case of a holding company impacting on a subsidiary, as in Standard Chartered Bank of Australia v Antico (No 2).[13] The term ‘shadow’ director or officer is also covered in s 9 under which an officer is a person in accordance with whose instructions or wishes the directors of the corporation are accustomed to act (excluding professional advisers). CLERP 9 also introduced the idea of the position of ‘senior manager’ which can be an officer.

In Australia the law relating to officers and directors can be divided into three:

• statutory duties

• common law duties of care, skill and diligence

• equitable fiduciary duties.

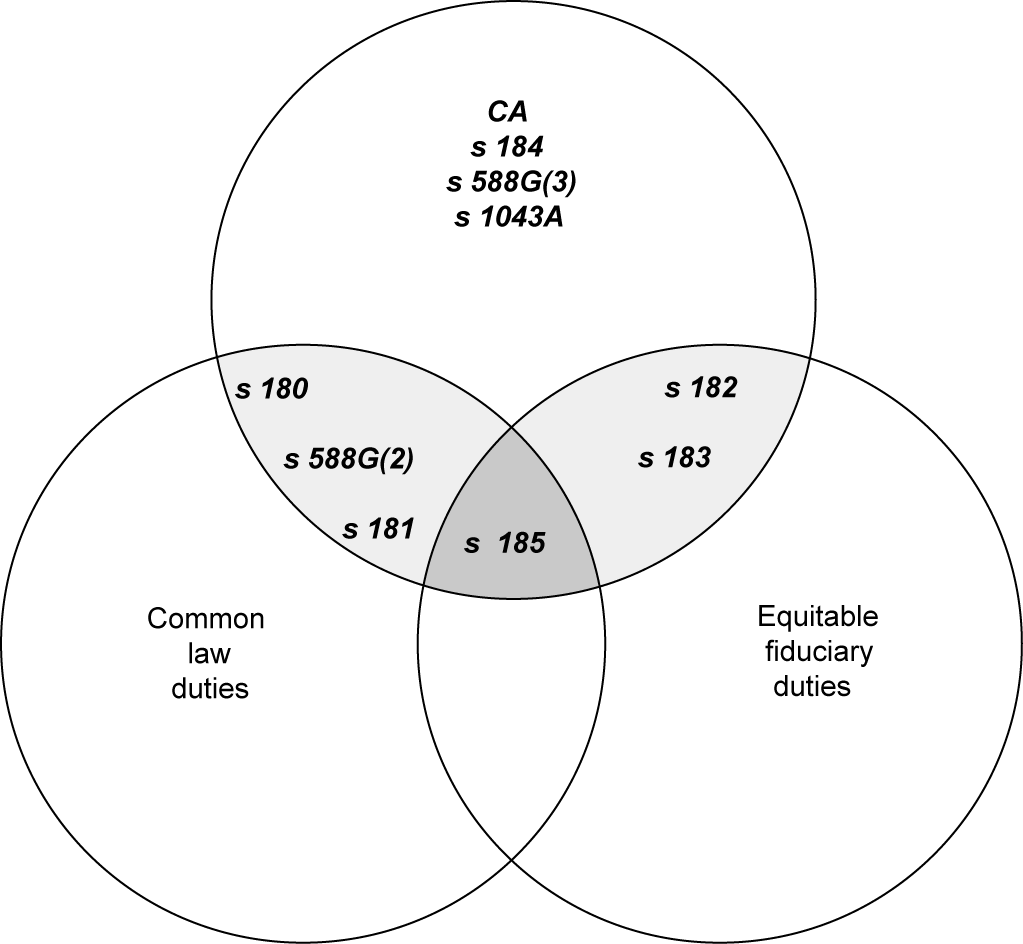

The fundamental duties that are imposed on all officers can be illustrated in a diagram. Figure 1 is an overview of officers’ duties and shows the interrelationship between the Corporations Act 2001, the common law and equitable duties. The overlapping areas represent how the Corporations Act 2001 in Part 2D.1 reflects parts of the common law and equitable principle. Some duties are specifically laid out in statute, such as insider trading in s 1043A. Other duties, such as when directors have interests in company contracts, are both statutory (s 191) and fiduciary duties. Directors must not trade while insolvent by s 588G and have a common law duty to consider creditors in times of financial trouble, as in the High Court of Australia case of Spies v R (2000).

Figure 1: Adams’ overview of officers’ duties (1992/2004)[14]

Where the three circles intersect represents s 185 which provides that the duties imposed by legislation are additional to the duties imposed at common law and in equity, rather than exclusive of them. Thus a director could be sued for all three actions rather than just the Corporations Act or the common law/equity principles. An example of a director being held liable for all three types of actions occurred in South Australia State Bank v Clark.[15]

A breach of ss 180–183 may result in a civil penalty order under s 1317E but this is not applied under the common law or equity. However, further criminal liability may also arise under s 184 in relation to the types of breaches found in ss 181–183.

However, it is worth noting that at common law officers are expected to be honest and to take reasonable care in exercising their duties. At the same time, s 181 provides that officers are required to discharge their duties in good faith and for a proper purpose, whilst s 180(1) provides that they must do so with reasonable care and diligence. Also, the equitable principles of avoiding conflicts of interest and not taking advantage of confidential information are reflected in both ss 182 and 183.[16]

The consequences for breaching any one of these duties may vary depending upon whether there is a criminal element or if damage has occurred to the company and its shareholders. The decision to sue a director or other officer for a particular section or common law duty will depend upon the individual circumstances. The statutory action under s 1317E may result in either a civil or criminal action or even a civil penalty order. The criminal actions are brought be either ASIC or the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP). Civil penalty actions are brought by ASIC, unless it is for compensation only, then a corporation may bring it, as in One.Tel Ltd (in liquidation) v Rich.[17]

Working professional directors and officers (as well as the many non-executive and part-time directors) have difficulty with keeping up-to-date with the many cases surrounding the same factual circumstances, but deal with different aspects of the law. For example the One.Tel litigation, which is often cited as the ASIC v Rich case involves many different sub-cases. Obviously, the HIH litigation and the GIO litigation, all produced many cases surrounding the directors duties. In the future, the Opes Brokers litigation will produce multiple cases to confuse directors and company secretaries.

One of the most significant decisions was the ASIC v Rich[18] (known as the “Greaves One.Tel” case) which occurred in 2003, as it examined the precise role of a chairman of the collapsed tele-communications company, One.Tel. Mr Greaves was held to have been a paid non-executive director with finance experience and thus owed a higher duty of care under the common law and statute than other directors by Justice Austin.[19] This original case was a procedural action which was to be struck out, went on to an out-of-court settlement for $20 million, which was paid to the liquidator. This settlement plus an agreed banning order had to be formally certified by Justice White and thus gives legal status to the earlier decision of Justice Austin in the NSW Supreme Court.

This particular decision by Justices White and Austin, and more importantly the principle behind it, has been subsequently followed in ASIC v Vines[20] (GIO case)[21] in 2005. Research shows that consistently two thirds of all corporate litigation relates to companies in financial trouble (insolvency or external administration including receivership) and the issue of directors’ duties during insolvency is critical. The application of the principle from the Greaves One.Tel case was applied in Hall v Poolman[22] in 2007 where Justice Palmer stated that the chair owed a higher duty of care due to the possession of “special knowledge”.

It is important to note that many of the principles of law discussed above can be derived from the general or basic law duties which were borrowed by way of an analogy of the trustees’ duties owed to the beneficiaries, from as long ago as 1853 in Re German Mining Co; ex parte Chippendale.[23] Although the Corporations Act in many ways codifies the common law and equitable duties, there is still an overlap and clearly have different outcomes depending upon what type of legal action is brought before the courts.

Conclusion

It is safe to say to all boards of directors in Australia from the smallest proprietary company to the largest multi-national listed on the Australian Securities Exchange, that the duties of corporate officers are onerous. There are over 1.5 million companies in Australia, all of them with at least one director and officer. On the ASX there are approximately 1,800 companies, each with at least three directors and officers. The proportion that results in legal actions is less than 1,000 per year and as stated above only 25 per year ever receive a gaol sentence for contravention of their legal duty. However, the twin peaks of the reputational damage and the courts’ attitude to executives, send out a strong message to do the right thing. The role of insurance (particular directors and officers, “D&O”) also plays a significant role in how directors’ cases are played out in the courts. However, insurance does not cover the outcome of a criminal prosecution nor civil penalties, as a matter of public policy and statutory intervention. All officers and directors are advised to keep a careful watching brief on the ever changes currents of litigation. The general duties of honesty and diligence will never change for professional officers.

10th June 2008

Word count = 2,031

[1] BA(Hons), LLM(Lond), FCIS, FACE, FAAL; Professor of Law and Head of the School of Law, and Provost Parramatta campus, University of Western Sydney. Contact author on michael.adams@uws.edu.au or 02-9685-9123.

[2] Justice of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Western Australia and the Royal Commissioner into the collapse of HIH Insurance.

[3] Neville Owen, “Idle musings on business decision making: Standards of corporate accountability after HIH and other disasters” (2008 5 May, Monash University, Australia.

[4] Alan Cameron “Directors’ duties: Navigating the storm on board” (2008, May 1st, Centre for Corporate Law and Securities Regulation seminar, Sydney).

[5] Michael Adams

“Are all directors created equal? Reassessing the role of the chair in the

light of ASIC v Rich” (2003)

vol 55 KGC p 204 and Michael Adams

“Officers’ duties under the microscope” (2005) vol 57 KGC p

516

[6] Section

180(2) Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

[7] Kristyn Briggs

and Evan Richards “Time for a new business judgment rule?” (2008)

vol 60 Keeping Good Companies p

288.

[8] Chief

Justice of the High Court of Australia at that time.

[9] Anthony Mason, “Corporate Law: The challenge of complexity” (1992) vol 2(1) Australian Journal of Corporate Law p 1.

[10] Ku v Song

[2007] FCA 1189 @ [175]. Quoted from Harris, Hargovan & Adams,

Australian Corporate Law LexisNexis 2008 p

vii.

[11] ASIC

annual report 2006–07.

[12] A more

detailed account was provided in Michael Adams “Whether to protect or

punish: legal consequences of contravening the

Corporations Act” (2004)

vol 56 KGC p

592.

[13] (1995)

131 ALR; 18 ACSR 1

[14] Harris,

Hargovan & Adams, Australian Corporate Law LexisNexis 2008 p

413.

[15] (1996) 16

ACSR 606

[16] These

concepts are explained in more detail in Harris, Hargovan & Adams,

Australian Corporate Law, LexisNexis:Butterworths

2008.

[17] [2005]

NSWSC 226

[18]

[2003] NSWSC 85

[19] This initial

case was the basis of the article Michael Adams “Are all directors created

equal? Reassessing the role of the

chair in the light of ASIC v Rich”

(2003) vol 55 KGC p

204

[20] [2005]

NSWSC 738

[21] This case was

discussed in detail in Michael Adams “Officers’ duties under the

microscope” (2005) vol 57 KGC p

516

[22] [2007]

NSWSC 1330

[23]

(1853) 3 De GM & G 19

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ALRS/2008/1.html