ALTA Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

ALTA Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 29 June 2012

CORPORATE REFORM – EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION?

PROFESSOR MICHAEL ADAMS[1]

School of Law, University of Western Sydney

ABSTRACT

In Greek mythology, Theseus used a ball of string to get out of a labyrinth;

so this paper will do the same in the field of Australian

corporate reform. This

paper examines the difficult issue of predicting future developments in

corporate law reform, based on historical

developments to date. The many topics

to be discussed are grouped according to three predominant themes, first,

officers/directors;

second, shareholders/institutions & AGMs; and third,

global corporate governance. The key assessment of the paper will concern

the

question of whether the corporate reform agenda has evolved over the last twenty

years, or whether there has been a revolution,

or even, whether the future holds

the possibility of revolutionary reform?

I INTRODUCTION

It is interesting to note that Australian corporate reform has been continuing consistently since 1989. It can be argued that at times we have had a revolution of corporate reform, but it is far easier to argue that it has been an evolution. This paper explores the bigger picture, beyond the usual developments in case law and legislation/regulation. Although it is important for governance professionals, directors, lawyers and company secretaries to keep up-to-date with changes, it is also important to look beyond the usual boundaries. In effect this paper provides ‘clues’ to the anticipated corporate reforms, by way of commentary on the current state-of-play.

It is said in Greek mythology that Theseus had a ball of string (called a ‘clews’) which he unwound as he travelled through a labyrinth, so he would not get lost. This paper will in turn string together contemporary clues to the labyrinth of corporate regulations. I also note that Saint Ives (the person, rather than the three English towns, and the Sydney suburb) was the Patron Saint of Lawyers and on his tomb its states “Saint Ives was Breton; A lawyer and not a thief; A marvellous thing to the people”.

A Big Ideas Outside This Paper:

When we ponder on the bigger picture it is possible to overlook that the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in May 2012, projected that Australia would be the fourth fastest growing developed economy, at the rate of 3.1%, only behind South Korea, Mexico and Chile. One need not mention that New Zealand’s predicted growth is 1.9%, USA’s 2.4%, UK’s 0.5% and poor Greece is at negative 5.3%![2]

Alternatively, we could focus on the remarkable rate of insolvencies that are occurring in Australia. We are all aware of the two-speed economy, but the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) are reporting the highest levels of insolvencies since statistical records were introduced in 1999. In February 2012 over 1,123 businesses were placed in administration compared to 518 in January 2012. 40% of the businesses placed into administration were court ordered. Of greater concern is the fact that the 97% of corporate administrations only return 11 cents in every dollar of debt.

The full impact of the financial crisis, around the world, post-2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) is still having repercussions on the local economies and securities markets. A few weeks ago A$56billion was wiped from the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) market and SuperRatings warned of superannuation being down by 3.2% on balanced funds, as there is a global flight to safety at this time of uncertainty. By the end of May 2012, it was calculated that a total of A$105billion was wiped off the ASX.[3]

Finally, the world is watching to see if Greece defaults and is forced (or elects) to leave the Euro-zone as well as what that might mean for the banking and finance sector. It is hard to see if this is a cause of corporate reform or time for a revolution.

B Big Ideas Within This Paper:

Now that we know what I am not going to discuss, we need to focus on the three big topic areas I do intend to cover:

II OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS

There are some really important developments occurring in the area of officers’ duties, or more commonly called ‘directors’ duties’. It is worth remembering that there are approximately 1.9 million registered companies, and each must have at least one director. Each year, ASIC, through the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions, has successfully prosecuted over 25 directors!

However, the corporate reform agenda has focused primarily on the definitions of officers and directors, the various roles management play (company secretary and general counsel are examples – what should a CFO know etc). It has been effected through key case law (and pending cases), as well as a constant flow of legislative reform.

Finally, there are increasingly important issues relating to diversity within the boardroom, which hold the potential to add value to the corporation. This diversity might be linked to gender, culture (race/ethnicity) or even technology.

A Some Definitional Issues:

It is worth noting that the legal term ‘officer’ is defined in s 9 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) as:

(a) a director or secretary of the corporation; or

(b) a person:

(i) who makes, or participates in making, decisions that affect the whole, or a substantial part, of the business of the corporation; or

(ii) who has the capacity to affect significantly the corporation's financial standing.

In most cases, the majority of officers of a corporation are the directors, but this does include the chief executive officer (CEO), possibly the chief financial officer (CFO) and other senior executives, depending upon the size and structure of the corporation. In a small corporation, there is likely to be only one director, who is also the CEO. The 2003 Royal Commission into the collapse of HIH Insurance recommended the change of terminology from ‘executives to the more functional approach of ‘officer’.[4]

The Corporations Act also provides a definition of ‘director’, which is also found in s 9, as:

(a) a person who:

(i) is appointed to the position of a director; or (ii) is appointed to the position of an alternate director and is acting in that capacity; regardless of the name that is given to their position; and

(b) unless the contrary intention appears, a person who is not validly appointed as a director if:

(i) they act in the position of a director; or

(ii) the directors of the company or body are accustomed to act in

accordance with the person's instructions or wishes.

In 99% of cases, it is

very clear who is an officer of a company, insofar as it includes all the

directors and the company secretary

(if appointed). In small corporations, the

CEO or managing director is nearly always a registered director. Even if he or

she is

not, they would be deemed to be an officer of the company and thus bound

by the same laws.

Officers of a company have very well defined legal obligations and there is a clear link to the role of corporate governance in all entities.[5] Over the last decade, corporate governance, and in particular the role of officers’ duties, has come under the microscope of the Australian courts, in all jurisdictions.[6] No director, company secretary, general counsel or CFO could argue they did not know what is expected of them in terms of the basic legal duties owed to the company. The HIH Insurance Royal Commissioner, the Hon Justice Neville Owen, in May 2008, re-stated the need for a commitment to education on the fiduciary principle and for greater professionalism in governance.

This paper builds on some earlier published work on directors’ and officers’ duties.[7] The Federal Minister responsible for developments in this area of law has noted that a review into the Safe Harbour Rule (known as the Business Judgment Rule[8]) in the Review of Sanctions in Corporate Law[9] paper, did not expect any quick changes at the moment. This is a very true statement, as there has been no change to this officers’ defence and few directors have ever been able to successfully rely upon it as a defence. The details of the business judgment rule are discussed below.

It is fair to say that any lay person might feel confused over the state of Australian corporate law. This is sharply brought into focus for directors and company officers that have an increasingly high expectations imposed upon them by a number of stakeholders.

But the courts do not remain static, in large part due to the wonders of the common law system of precedent. A broader meaning of the term officer was given in the recent Victorian Supreme Court case of Hodgson v Amcor,[10] where a senior manager was deemed to be an officer for the purposes of the Corporations Act. Similarly, the more complex issue of de facto directors occurs and in another recent case, Grimaldi v Chameleon Mining NL (no 2)[11] stresses the need to look beyond the formal appointment procedures to determine whether a person owes a fiduciary duty.

B Basic Review of Australian Officers’ Duties

In April 2010 the Australian Government’s reform body for corporate law, the Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee (CAMAC) published a more detailed guide for directors.[12] This report outlined in detail the challenges facing directors and the various guidance to be drawn from legislation, the case law, the regulators and the ASX Corporate Governance Council. It also provides an international comparison with the United Kingdom and North America. However the report is a more useful resource for public companies and those listed on the ASX, rather than smaller entities.

Before examining the recent developments in Australian case law on officers and, in particular, director’s duties, it is valuable to review the existing legal framework. There is a natural overlap between the legislation imposed by Parliament and the case law developed over the last couple of centuries. Companies have existed since the 1600s[13] but the modern, incorporated (registered) company can be traced back to 1844.[14] Australia has , for the most part, followed the corporate laws of the United Kingdom but has only moved to registered corporations as part of the change, in 1991, to a national system, under what is now the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

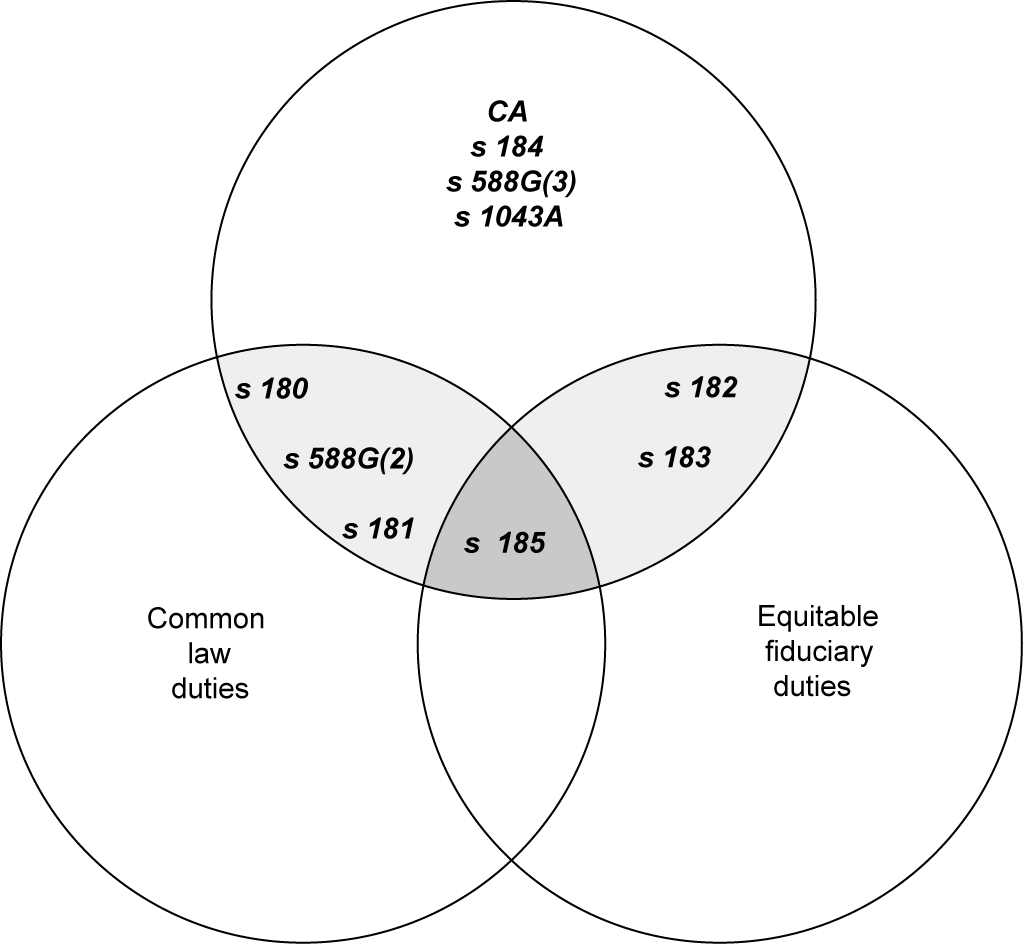

In Australia, the laws relating to officers and directors can be divided into three parts:

• Statutory duties;

• Common law duties (such as the duties of care, skill and diligence); and

• Equitable fiduciary duties.

The fundamental duties, that are imposed on all officers of all registered companies, can be illustrated in a simple Venn diagram. The overlapping areas represent how the Corporations Act reflects aspects of both the common law and equitable principles.

Figure 1: Overview of officers’ duties[15] (Adams, 1992 – updated 2011)

Some duties are specifically laid out in statute, such as the prohibition on insider trading in s 1043A. Other duties, such as when directors have interests in company contracts, are both statutory (s 191) and fiduciary duties (s 182). Directors must not trade while insolvent, by virtue of s 588G, and have a common law duty to consider creditors in times of financial trouble, as in the High Court case of Spies v R.[16]

The three circles intersect at s 185, which provides that the duties imposed by legislation are additional to, and not exclusive from, the duties imposed at common law and in equity. Thus a director could be sued for all three bases of action, rather than just the Corporations Act or the common law/equity principles. An example of a director being held liable for all three types of actions occurred in South Australia State Bank v Clark.[17]

A breach of ss 180–183 may result in a civil penalty order, under s 1317E, but this is not applied under the common law or equity. However, further criminal liability may also arise under s 184, in relation to the types of breaches found in ss 181–183. This is important due to the different kinds of remedies that apply to civil, civil penalty and criminal cases.

C Beyond Recent Case Law

However, it is worth noting that at common law, officers are expected to be honest and to take reasonable care in exercising their duties. At the same time, s 181 provides that officers are required to discharge their duties in good faith and for a proper purpose, whilst s 180(1) provides that they must do so with reasonable care and diligence. This is comparable to the tort of negligence, which was recognised in the corporate directors’ context in ASIC v Adler.[18] Also, the equitable principles of avoiding conflicts of interest and not taking advantage of confidential information are reflected in ss 182 and 183 respectively.

Working, professional directors and officers (as well as the many non-executive and part-time directors) have difficulty keeping up-to-date with the many cases surrounding the same factual circumstances, but which often deal with different aspects of the law. For example the One.Tel litigation, which is often cited as the decision of ASIC v Rich,[19] involves many different sub-cases. Obviously, the HIH litigation and the GIO litigation all produced many cases surrounding the directors’ duties. In the future, the 2007-2008 collapses of Opes Prime brokers’ litigation and Centro shopping centres will produce multiple cases to confuse, or possibly enlighten, directors and company secretaries.

One of the most significant decisions was the ASIC v Rich[20] (known as the ‘Greaves One.Tel case’) which occurred in 2003, as it examined the precise role of a chairman of the collapsed telecommunications company. Austin J held that Mr Greaves had been a paid, non-executive director with finance experience and thus owed a higher duty of care under the common law and statute than other directors. This original case was a procedural action, which was to be struck out, but went on to an out-of-court settlement for $20 million, which was paid to the liquidator. This settlement, plus an agreed banning order, had to be formally certified by White J and thus gives legal status to the earlier decision of Austin J in the NSW Supreme Court. The final case of Jodee Rich did not work out positively for ASIC in 2009. Before detailing the failed litigation of ASIC, it is important to note the limited success in the James Hardie litigation and other major cases.

The High Court of Australia does not often examine corporate law cases, but one of the many One.Tel cases which it did consider, Rich v ASIC,[21] examined the importance of procedures in the area of civil penalties. The HIH Insurance cases around ASIC v Adler[22] scrutinised in depth the civil penalty standards of directors’ duties. In particular whether Mr Rodney Adler acted dishonestly (a breach of s181) and the failure to take reasonable care and diligence (a breach of s 180) by Mr Ray Williams and Mr Adler. Unusually, a separate criminal prosecution was launched against Mr Williams[23] and Mr Adler,[24] resulting in a conviction and jail sentence. This was followed by the high profile case of Steve Vizard, which involved the misuse of confidential information, from the boardroom of Telstra, for personal gain.[25] This case could have been brought under the insider trading laws, but was in fact brought under the directors’ duties provision for misusing confidential information.

Hot on the heels of the HIH Insurance cases were the GIO cases (the hostile takeover by AMP of GIO) which resulted in ASIC v Vines.[26] In this case the three CFOs of the various GIO companies were held liable for a breach of their duties as officers of the target company. A higher duty of care had been expected of a chair of a company, or even a board audit committee, following Hall v Poolman.[27]

Thus, after a number of successes against directors in the civil and criminal courts, ASIC potentially hit a wall. The initial highs of the successful 2009 James Hardie litigation[28] has resulted in an appellate court over-ruling Gzell J in a number of ways and exonerating most of the directors held liable. The case of Morley v ASIC[29] and James Hardie Industries NV v ASIC[30] was a huge step backwards for the regulator. The outcome of the appeal was that the company (JHL) was found to have made misleading statements to the ASX in June 2002 and failed to comply with continuous disclosure obligations. The CFO at the time, Mr Morley, was in breach of his duty in advising the board and thereby limited the nature of the predicted analysis of compensation. Similarly, the company secretary and general counsel, Mr Shafron, had part of his appeal upheld, but was still found to be in breach of his duty to advise the board. The other non-executive directors, including the chair, Ms Hellicar, were successful in their appeals such that the finding of breaches of the officers’ duty in s 180 were removed (in respect of the approved minutes of the board meeting, which became the ASX announcement on asbestos compensation). ASIC was criticised for not calling a particular witness (an external lawyer) who was present at the relevant board meeting of JHL.[31]

In May 2012, the High Court finally ruled on the James Hardie litigation with a clear statement, holding the non-executive directors liable in ASIC v Hellicar.[32] The matter was also remitted to the NSW Court of Appeal for the determination of the appropriate penalty for the non-executive. But the executive director that appealed, the company secretary and general counsel, was dismissed and the person was held to have failed to advice the CEO and board of information from the professional advisors and the famous media release of 16th February 2001, in Shafron v ASIC.[33]

One of the most important contemporary decisions involved the entrepreneur and miner, Mr Andrew ‘Twiggy’ Forrest and his ASX listed company, Fortescue Metals Group Ltd (FMG). Mr Forrest, on behalf of FMG, announced through both media releases and ASX announcements that ‘binding agreements’ with various Chinese, state-owned, corporations had been made to develop the Pilbara region of Western Australia for iron ore exploration. From August 2004 until November 2004 the share price rose of FMG from 59 cents to $1.93. By March 2005 the share price had reached a high of $5.05 per share. The Australian Financial Review investigated the claims of the so-called binding agreement and as a result the price started to drop (once the agreements were formally disclosed to the ASX).

ASIC started proceedings against the FMG for making misleading statements and failing to comply with continuous disclosure laws. In addition, Mr Forrest, as an officer of the company, was alleged to have breached his officers’ duty of reasonable care under s 180(1) Corporations Act. The Federal Court found that there was no breach of the Act in ASIC v Fortescue Metal Group [No 5].[34]

ASIC decided to appeal the decision of the trial judge, Gilmour J, and were successful on all counts in ASIC v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd.[35] The actual penalty imposed on FMG for the misleading conduct, contravening s 1041H, failure to comply with continuous disclosure, contravening s 674(2)), or personally against Mr Forrest for the officers’ duty of reasonable care, contrary to s 180(1)) and his involvement in the breach of continuous disclosure, pursuant to s 674(2A)), has not yet been determined.[36] Significantly an application for leave to appeal to the High Court has been made such that we await the decision sometime in 2012.

The Centro litigation has raised many concerns about the ability of directors and officers to personally equip themselves with the financial literacy and the converse ability to rely upon others, such as an external expert or even the audit committee. The decision in ASIC v Healey[37] showed that the board did not take the necessary care with the financial accounts, but accepted their individual forthrightness and thus did not impose penalties. A separate class action has just been settled, in May 2012, against the auditors and companies for $200million, with the legal costs at $15m and IMF funders receiving $60m and leaving the shareholders to split the remaining $125m for their losses.[38] A further example is the case of Kirby v Centro Properties Ltd (No 2)[39] which dealt with the difficult issue of legal privilege in advice provided to the board.

Finally, all directors and officers tend to place a high level of reliance upon directors and officers insurance policies (known as ‘D&O’ policies) for protection. However, D&O policies were recently brought under the microscope of the New Zealand High Court in Steigrad & Ors v BFSL 2007 Ltd & Ors.[40] The court ruled that the creditors are entitled to any money paid by the insurer to the company in satisfaction of specific debts. This principle could be applied to Australian policies in the future.

All of the above comments only touch on a tiny proportion of the corporate reform case law that occurs every year. It is important to note that many of the principles of law discussed above can be derived from the basic legal duties which were borrowed, by way of an analogy to the duties owed by the trustees to the beneficiaries, from Re German Mining Co; ex parte Chippendale.[41] Although the Corporations Act in many ways codifies the common law and equitable duties, there is still an overlap even though they have different outcomes in terms of remedies or sanctions.

ASIC must take risks with litigation, as it is the only way to really test the complex statutory provisions of the Corporations Act. However, there is a publicity risk when the regulators lose a major case, which makes proper case preparation absolutely crucial.

D Beyond Corporate Reform in Legislation

Over the last twenty years, we have lived with the constant reform in corporate law, from the Simplification Task Force to the Corporate Law Economic Reform Program (CLERP), and towards a more ad hoc approach of naming legislation. As well as the primary legislation, there are literally thousands of regulations and other minor changes which constantly flow through the corporate environment, depending upon the particular industry or service or government policy – carbon tax would be an example.

For the purposes of this paper, the focus is on the seven noteworthy areas but these will be deakt with at bird’s eye view, as all will require detailed examination if they directly relate to your business entity.

Personal Liability for Corporate Fault Reform Bill 2012 – has been debated for a while and was intended to provide better clarity for officers of corporations in certain circumstances. As discussed above, the business judgement rule could have been applied broadly to the Corporations Act, but rather it has been applied narrowly to s 180 reasonable care and diligence actions. There is some good news for company secretaries, by way of the suggested amendments, in reducing liability under s 188, but an increase to the general penalties in Schedule 3 of the Corporations Act.[42]

Future of Financial Advice (FOFA) reforms – will build on the amendments of the Financial Services Reform Act 2001, which greatly altered the licensing regime under the Corporations Act. The focus is on protecting consumers and clients who receive financial advice, but such reforms come at the cost of compliance.[43]

Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (‘PPSA’) – became operational from 30 January 2012 and completely changed the way personal security arrangements are facilitated. It also introduces a new regime with new terminology, in respect of regulation and compliance, such as the reference to a ‘security interest’ and requirement that it be ‘perfect’. A two-year transitional period applies to the legislation, but all corporations should be working with their professional advisers so as to be prepared for the new PPSA priority rules and enforcement provisions which will be applied.[44]

Business Names Registration Act 2011 – it has been flagged for some time that ASIC will take regulatory control of all national business names and apply similar tests and procedures that already occur with corporate names and the Australian Trade Marks Register. The new law became effective on 28 May 2012, but there are still some states and territories that have yet to pass enabling legislation to make the Business Names Register fully national and functional.[45]

Work Health and Safety national legislation (WHS) – there has long been a push to create a simplified version of occupational health and safety (OHS) laws which is harmonised between the states and territories. The Commonwealth, NSW, Queensland and ACT have passed the necessary laws and others are following suit. It has had the effect of creating new terminology, such as the movement from ‘employers’ to ‘PCBU’ (persons conducting a business or undertaking). Also employees, visitors and even volunteers have clearer duties owed to them (even when working from home). A lot has already been written on WHS and in the next few years, even more will be published.[46]

Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (‘CCA’) – ACL – carbon tax – the conversion of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) into the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) helped split the anti-competitive (monopolies, price-fixing etc) provisions from the consumer protection provisions. The creation of Schedule 2 to the CCA, which is known as the Australian Consumer Law (‘ACL’), brought together the wide-ranging provisions of the federal, state and territories consumer laws under one structure. A simplification of the enforcement of remedies and sanctions, the consistency for national businesses, as well as giving equal consumer rights to all Australians, were positive steps. However, as with all change there are direct costs, for instance overtime will become just part of the ‘licence to do business’. One particular area of focus of consumer protection has always been ‘misleading or deceptive conduct’, which was known as a section 52 action, which is now officially dealt with by section 18 of the ACL. There is currently a particular focus on misleading environment claims (known as ‘greenwash’).[47] The regulator, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), has set up a specific surveillance unit relating to misleading claims arising from the introduction of the ‘carbon tax’ in July 2012.

Corruption legislation – the introduction of which has become a prominent global issue. The Corruption Perceptions Index that is published by Transparency International, which covers 182 countries, indicates corruption risks. There are already some provisions, in the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth), which cover Australian companies, as well as Australian and International Standards.[48] The Bribery Act 2010 (UK) and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act 1977 15 U.S.C. §§ 78dd-1 have been amended and updated to tackle a number of global concerns. These international statutes have a broad reach, covering US and UK companies operating in Australia, as well as Australian companies operating internationally.[49] The damage of reputation for the Reserve Bank of Australia (through its subsidiary Securency Note Printing); Lend Lease’s fraud settlement for US$56million and even the News Limited phone hacking scandal, are immense.

The question for the board is about the perception of risk, as much as the actual likelihood of risk, to the board, for breaching either case law or the developing legislation. Boards need to be educated, advised and guided, but not so as to be paralysed by fear of making an incorrect decision. This requires a tricky balancing act.

E Diversity in the Boardroom

One of the continuing debates in the field of corporate reform is the role of diversity in the boardroom. The days in which all directors of a board personally knew each other, and/or had a series of mutual friends, should have changed decades ago. The problem with the debate on diversity is that it gets bogged down on just gender diversity, thus overlooking the need for cultural giversity (traditionally expressed as race, now more commonly as ethnicity), generational diversity (baby-boomers to generation ‘Y’ or even ‘i-Generation’) to diversity in the use of technology!

There is research to support the proposition that diversity in the boardroom will increase profitability and sustainability of organisations.[50] In respect of gender, the celebration of International Women’s Day on 8 March 2012 saw the release of a report by the Australian Institute of Company Directors on female appointments to ASX listed companies. In 2012, the percentage had increased in the top 200 companies to 13.8%, compared to only 11.2% in 2011 and below 10% in 2010. This translates as 68 new female appointments to ASX 200 boards, which is one in three of all new appointments. There is a strong representation in the biggest companies, thus the ASX top 20 companies have 20% female directors and top 100 ASX companies have 17.3%.[51]

The European Union (EU) is planning to impose mandatory quotas in order to increase the number of women on boards. In 2012, a three-month consultation outlining the EU’s proposals has commenced. It will seek views on the levels of quotas and methods for monitoring and enforcement. The EU Justice Commissioner stated that this is necessary as so little progress has been made towards a 40% target, as a minimum proportion of women on boards. The EU figures show only 13.7% of board members at large listed companies as women. In respect of the UK, there are just ten all-male boards in the FTSE100 and the proportion has increased to 14.9% from 12.5% last year.[52]

Following from the discussion around gender diversity, there needs to be some recognition of the impact of cultural diversity.[53] This might include race or ethnicity issues or generational aspects. The majority of directors on listed companies would be classified as baby-boomers,[54] with a few Generation ‘X’ directors.[55] Thus, a technology company might wish to have inter-generation board members to reflect its workforce, customers or other stakeholders. To take the line of thought further, it might be a technology gab that requires diversity within the boardroom.[56]

The move from fixed devices and controlled standard operating environments will most likely change to a policy of ‘BYOD’[57] and have drastic impacts on the way businesses operate. The flexibility and cost transfer will be positive, but security, viruses, bandwidth/downloads and support costs will change dramatically.[58]

III SHAREHOLDERS, INSTITUTIONS AND AGMS

There are a number of internationally developing themes relating to the question of the influence and power of shareholders; the role of institutional investors and in part a question as to the real value of the annual general meeting (AGM). This part of the paper simply summarises some of the key issues and provides an elementary discussion and observation.

A Annual General Meetings (AGMs)

The annual general meeting continues to be as a necessity, as the Corporations Act requires all public companies to go through the mechanics, albeit without any evaluation of the costs nor benefits of this process. The 2011 AGM season is likely to be challenging for many companies.[59]

There has been limited research on the true costs and benefits of AGMs. One key question is the changing face of shareholders and the role of technology at AGMs. There needs to be much more analysis of the appropriateness and effectiveness of all meetings, but in particular the traditional AGM. In 1995 Parliament deemed the AGM unnecessary for private companies, but felt it was still appropriate for public companies.

The real contentions seem to be around the voting issues at AGMs, the role of the notices and proxy appointments and the need for an overall communication strategy with shareholders – both individuals and large institutional members.

1 Impact of Executive Remuneration on Meetings

There has been a huge debate on the merits of disclosing executive remuneration and the value of shareholders voting on a non-binding resolution. The laws have been amended over time to result in an ambiguous ‘two-strikes rule’ under the Corporations Act, as well as provisions in the APRA Guidelines and ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Principles.[60]

A bigger question around the growth in institutional power and through the block voting capacity of superannuation trusts, is the diminishing role of minority members. Well over half of the adult Australian population owns shares in publicly listed companies directly (and a huge number, indirectly, through superannuation).[61]

At the time the original ‘non-binding vote’ was passed into law in 2005, I personally wrote a submission to Treasury, recorded in Hansard, equating ‘it [to] being as useful as a chocolate tea-pot’. Senator Stephen Conroy, at the time, disagreed and we would have to wait and see what would eventuate. The fact that, in 2012, we now have legislation requiring the two-strikes rule means that it is safe to assume that the previous provisions did not work as expected! There are questions around whether laws for 1.9 million companies, are the same as the 20,000 public companies and the sub-set of 2,100 listed public companies on the securities exchanges?

IV GLOBAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

There have been many reviews, reports, commissions, academic scholarly works on, and practical application to, the question of whether corporate governance adds value to an organisation, and in turn, whether one system better than another. The answers have not always been carefully provided and there is overwhelming, corroborative, empirical evidence as to the impact of sustainability in governance.[62] There is also a growing body of evidence as to the value-add of governance and international scholarship to demonstrate that one system is not superior to another. Thus, there is no direct evidence that the Anglo-American system of governance is superior to the European two-tiered boards or the examined Japanese or other Asian family-based (small control span) entities.

The 2008 global financial crisis (GFC) and the many 2011-2012 aftershocks with the European financial crisis, can be stated to be a consequence of the failure of corporate governance. Without a doubt this is too simplistic an approach and a greater understanding of how global corporate governance actually works is required. There is an arguable connection or correlation, but is it significant enough of a result to have a major change in government policy or a need for the private sector to react differently? It is fair to say that the debate as to what constitute ‘good corporate governance’ is still open; practical and empirical research in law, economics, finance, accounting and management, does not always arrive at the same conclusions.

A Convergence Debate

There is a level of arrogance in the Anglo-American literature that the one model of corporate governance is far superior to the other purported systems of governance. In the early 2000s there was a lot of material written by academic scholars suggesting that there would be a natural convergence of corporate governance practices into a single model. [63] But subsequently there has been a very strong argument that governance is jurisdictionally irrelevant and that culture can play a major role in economic development. It is not appropriate to maintain a simplistic view of insider corporate governance systems, or for that matter for countries like Germany and Japan to receive global pressure in favour of a ‘superior’, shareholder orientated, outsider corporate governance system, such as those applied in the USA, UK and Australia. This is not really convergence, but a move to transformation of capital markets and an end to globalisation.[64]

Corporate governance is not a moral position for a few jurisdictions, but rather is naturally open to all types of jurisdictions and capital markets. Over the last several decades it has proven to be a strong economic indicator, but not a predictor, of corporate failure in any country.

B Changing Nature of Governance – Global Communication

The last 20 years of contemporary corporate governance, post the 1992 Cadbury Report[65] and its equivalent reviews in New Zealand, Australia, USA, South Africa and many other countries, have seen a major shift, which is described well in Boards that Work.[66] The ease of communication, around the world, enables not only the multi-national or even transnational corporation to access the latest governance trends, but simple ‘Google searches’ provide ample resources to examine, in depth, the practical and theoretical aspects of governance.[67] The ability to compare and contrast successes and failures of systems of governance around the globe has become an effective tool in governance developments. In Australia, it was common for a director to sit on a board in Melbourne and get ideas for the board he or she might sit on in Sydney. Now with a click of an iPad or smartphone, the innovative director can be checking on governance developments in Poland, Sweden or even New Zealand.

C Global Trends

There are numerous studies as to the benefits of corporate governance for global entities, whether they be transnational corporations or the more traditional multi-national companies.[68] However, by far the majority of business entities are privately owned (and/or family businesses) with a small percentage being quoted on a local stock exchange, in a single legal jurisdiction. As such, the often cited ‘trickle-down effect’ of big business adds on the cost of compliance without any real tangible benefit. For an interesting and detailed analysis of corporate governance in the Asia-Pacific region, ‘Corporate Governance: An Asia-Pacific Critique’[69] is an excellent starting point, with the 2012 Global Corporate Governance Forum review, [70] bringing the literature right up-to-date.

The breath in literature and issues of governance, primarily from the legal regulation literature (rather than accounting, economic, finance or management) includes Professor Farrar on the developments in greater China[71] to Professor Armstrong dealing with tangible value of governance standards.[72] Professor Tomasic in 2000 analysed the international challenges of good corporate governance[73] to Dr Tricker on cultural dependence of governance[74] to the more local focus of Dr Comino’s article on better corporate regulation in 2011.[75] All demonstrate a move away from convergence and towards a global transformation model.

D Conflict with Role of Global Governance

If there is little agreement with the role of corporate governance by legal scholars, there is even less so by economists. This conflict of views was illustrated at the CSA national conference in December 2011, when David Thomas[76] described the impact of the BRIC economies with a positive slant, which was immediately followed by Satyajit Das[77] on the unstable economic state of affairs. Therefore one can conclude that governance is not a clear indicator of economic growth or stability.

E Useful Resources

The academic and practical literature continues to grow on what seems to be a monthly basis. This reflects the global understanding of the importance of corporate governance. Two recent resources, in late 2011 and January 2012, provide reliable sources. One has a very practical framework and was produced by the global consulting firm Deloitte, whereas the other is by two academics already referred to, Claessens and Yurtoglu.

Deloitte’s ‘Director360°’ (November 2011) report,[78] which is freely available on the internet, and was based on research conducted on Deloitte clients, and covered 215 directors in 12 different countries. The reports subtitle ‘Changing Roles, New Challenges’ reflects practical outcomes of concerns directors are facing in an economic downturn. What is interesting to note is that the findings across South Africa, Sweden, Germany, India, Japan, UK, Australia and USA are very similar to the empirical study conducted by Professors Clarke and Adams on purely Australian listed entities in 2007.[79]

The focus of the study by Deloitte was on how boards were evolving in strategy, overseeing risk and board effectiveness generally. They also asked the directors to rate what was on the current board agendas, as well as the top issues for next 24 months. There is a clear debate over the monitoring role of the board of management (in particular the CEO), the performance of CEO and his or her capacity to act as a mentor. Key findings included that more than half of the directors are experiencing high levels of scrutiny by the regulators and 85% felt they were developing strategy for the corporation. The majority of directors felt the board had a balance between governance and performance, but that compliance was a distraction in the economic downturn. The economic conditions were forcing the board and management to clarify roles and the top agenda items were consistent around the world.

At a much more substantial level, one of the most detailed international, comparative reviews of the corporate governance literature over the last decade was undertaken by Professors Claessens and Yurtoglu. This covers economics, finance, management and legal scholarship and studies in many different countries and jurisdictions. The survey provides overwhelming evidence of the importance of corporate governance at a number of economic points.

Claessens and Yurtoglu’s ‘10 Focus: Corporate Governance and Development – An Update’[80] is a document that provides evidence of a link between economic development and corporate governance, based on extensive studies in many countries, sectors and business organisations (from state-owned corporations to public listed entities). In sifting through the scores of academic studies the article attempts to determine what matters most in the way corporate governance can support economic development and what is needed to implement good practices.

The extensive cross-country research shows financial development, such as sophisticated and quality banking systems is a powerful determiner of sound economic growth. Weak corporate governance prevails in financial markets, which tend to function poorly. Poor governance increases market volatility, through a lack of transparency and by giving insiders the edge on information crucial to the market integrity and the basis of fair trading. Blind faith is not a substitute for a thorough verifiable reporting by firms, led by boards of directors that clearly articulate their responsibilities and duties.

Countries and companies adopting corporate governance best practices are not guaranteed success, but rather a move towards sustainability and establishing long-term success. This report provides ample evidence as to why adopting good corporate governance practices is a worthwhile activity and goal of every board.

F Education May be the Answer...

There is no doubt that boards of directors need to be continually educated, across a range of matters. In Lighting the Way to a Better Future Nelson Mandela said that ‘[e]ducation is the most powerful weapon we can use to change the world’.[81] This applies to everyone, in every capacity. There has been much discussion about the ‘life-long learners’ and the need for continuing professionalism. Directors, particularly non-executive, heavily rely upon the professional expertise of the company secretary and others within the management team. As such, the idea to continuously up-date education aspects beyond formal courses, so as to be up-to-date is critical. The demand for financial literacy courses since the outcome of the Centro litigation has been exponential. It is understandable that directors are nervous about their legal responsibilities and are truly accountable to shareholders, creditors and the regulators.

V CONCLUSION

It is easy to be side-tracked by the latest trend of cases (such as the High Court decision in the James Hardie litigation)[82] or the latest changes in legislation (such as the application of the PPSA). However, the board’s focus has to be on the company’s strategy and performance. It is notoriously difficult to predict the future,[83] but we need to learn from the mistakes of the past. We can be prepared as governance develops in what has previously been discussed as clear trends, locally, regionally and internationally. This paper is intended to start the conversation to help educate boards on an on-going basis. Directors, like all humans, have a variety of learning styles, which means that anything from reading a document, to watching a TED YouTube video,[84] or listening to a good presentation can be effective.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A Articles/Books/Reports

Adams, Michael, ‘The Convergence of International Governance – Where is Australia Heading?’ (2002) 54 Keeping Good Companies 14

Adams, Michael, ‘Are All Directors Created Equal? Reassessing the Role of the Chair in the Light of ASIC v Rich’ (2003) 55 Keeping Good Companies 204

Adams, Michael, ‘Whether to Protect or Punish: Legal Consequences of Contravening the Corporations Act’ (2004) 56 Keeping Good Companies 592

Adams, Michael, ‘Officers’ Duties Under the Microscope’ (2005) 57 Keeping Good Companies 516

Adams, Michael ‘Officers’ Duties – Are We Keeping Up With the Changes?’ (2008) 60 Keeping Good Companies 344

Adams, Michael ‘Lessons for Non-Executives from James Hardie Litigation’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 263

Ahrens, Michael and Georgie Farrant, ‘Bribery of Foreign Officials

– Key Steps in Mitigating the Risks’ (2012) March,

the Australian

Corporate Lawyer 14

Adams, Michael and Marina Nehme, ‘No New

Specific Legislation Required to Deal With “Greenwashing”’

(2011) 63 Keeping Good Companies 419

Armstrong, Anona, ‘Corporate Governance Standards: Intangibles and Their Intangible Value’, (2004) 17 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 97

Comino, Vicky, ‘Towards Better Corporate Regulation in Australia’ (2011) 26 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 6

Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee, Parliament of Australia, Guidance for Directors Report, (2010)

Das, Satyajit, ‘A Vulnerable State – The Economic Outlook for Australia’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 15

Dignam, Alan and Michael Galanis, The globalization of Corporate Governance (Ashgate, 2009)

Dooley, Greg, ‘2011 AGM Season – Providing Clues to What Lies Ahead’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 86

Douglas, Marnie, ‘Putting Workplace Health and Safety Laws to Work’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 89

Editor, ‘Embracing Technology in the Boardroom by Moving Board Papers Into the Digital Realm’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 76

Editor, ‘EU Outlines Plan for Board Gender Quotas’ (London) April 2012, Chartered Secretary 5.

Farrar, John, ‘Developing Corporate Governance in Greater China’ [2002] UNSWLawJl 29; (2002) 25(2) UNSW Law Journal 462

Ferguson, Adele, ‘More Women Join Boards but Glass Ceiling Remains

Intact’, Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 08 March 2012,

3

Gilkison, Flora, ‘Diversity and the Governance Double Glazing

Trap’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 97

Hargovan, Anil,

‘Directors’ and Officers’ Duty of Care Following James

Hardie’ (2009) 61 Keeping Good Companies 586

Hargovan,

Anil, ‘Raising the Bar for General Counsel and Company Secretaries - High

Court Decision in James Hardie’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies

260

Harpur, Andrew ‘It’s a Privilege – Company Secretary’s Notes of Legal Advice to Board Protected’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 156

Harris, Jsaon, Anil Hargovan and Michael Adams, Australian Corporate Law, (LexisNexis:Butterworths, 3rd ed, 2011) 449

Harris, Jason and Nicholas Mirzai, ‘The Personal Property Securities Act and Company Secretaries’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 92

Head, Michael, Scott Mann and Simon Kozlina (eds), Transnational Governance: Emerging Models of Global Legal Regulation (Ashgate, 2012)

Head, Richard, ‘Directors and Officers Still in the Firing Line – A Guide to Managing Risk’ (2010) 62 Keeping Good Companies 57

Kiel, Geoffrey and Gavin Nicholson, ‘The Changing Nature of Corporate Governance’ in Boards That Work: A New Guide for Directors (McGraw-Hill, 2003)

Klettner, Alice, Thomas Clarke, and Michael Adams, ‘Balancing Act – Tightrope of Corporate Governance Reform’ (2007) 59 Keeping Good Companies 648

Klettner, Alice, Thomas Clarke and Michael Adams, ‘Corporate Governance Reform,: An Empirical Study of the Changing Roles and Responsibilities of Australian Boards and Directors’ (2010) 24 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 148

Low (Ed), Chee Keong, Corporate Governance: An Asia-Pacific Critique (Sweet & Maxwell Asia, 2002)

MacGibbon, Ainslie, ‘Smarter Use of Home Devices’, Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 28 May 2012, 17

MacMillan, Claire, ‘Impact of Regulatory Reforms on Executive Remuneration in Australia – AGMs in 2011’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 100

Mandela, Nelson, Lighting the way to a better future (South Africa,

2003)

Martin, Peter, ‘Housing a Worry but Economy Booming, Says

OECD’, Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 23 May 2012,

3

Moodie, Anne Maree, ‘International Governance – Leading a Truly

Diversely-Composed Board’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies

6

Morgan, Gemma, ‘De Facto Directors and Duties –

Chameleon Mining’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 222

Nicholson, Diana and Josh Underhill, ‘Government Releases First Tranche of Reforms to Company Officer Liability’ (2012) 64(2) Keeping Good Companies 70

Nicholson, Gavin and Natalie Elms, ‘Corruption, Corporate Culture and the Board’s Responsibility’ (2011) 63 Keeping Good Companies 594

Thomas, David, ‘Building With New BRICs’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 10

Thomas, Keith ‘The Bridgecorp Case – Could Creditors Stop a Company’s D&O Insurers Paying Defence Costs to Directors?’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 45

Tomasic, Roman, ‘Good Corporate Governance: The International Challenge’, (2000) 12 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 142

Tricker, Bob ‘Culture Dependence of Corporate Governance’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 27

Wood, Leonie, ‘Funder Gets $60m from Centro Deal’ Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 11 May 2012, 3

Yeates, Clancy, ‘Advisers Allowed ‘Opt-In’ Exemption’ Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 23 March 2012, 3

B Cases

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Adler [2002] NSWSC 171; (2002) 168 FLR 253

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Fortescue Metal Group [No 5] [2009] FCA 1586; (2009) 264 ALR 201

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd [2011] FCAFC 19; (2011) 190 FCR 364

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Healey [2011] FCAFC 717; (2011) 278 ALR 618

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Hellicar (2012) 86 ALJR 522

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v MacDonald (No 11) [2009] NSWSC 287; (2009) 230 FLR 1

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v MacDonald (No 12) (2009) 259 ALR 116

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Rich [2003] NSWSC 85; (2003) 174 FLR 128

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Vines [2005] NSWSC 738

Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Vizard [2005] FCA 1037; (2005) 145 FCR 57

Grimaldi v Chameleon Mining NL (no 2) [2012] FCAFC 6; (2012) 200 FCR 296

Hall v Poolman [2007] NSWSC 1330; (2007) 215 FLR 243

Hodgson v Amcor [2012] VSC 94

James Hardie Industries NV v Australian Securities and Investment Commission [2010] NSWCA 332; (2010) 274 ALR 85

Kirby v Centro Properties Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCA 70; (2012) 87 ACSR 229

Morley v Australian Securities and Investment Commission [2010] NSWCA 331; (2010) 247 FLR 140

R v Adler [2005] NSWSC 274

R v Williams [2005] NSWSC 315; (2005) 216 ALR 113

Re German Mining Co; ex parte Chippendale [1854] EngR 664; (1853) 43 E.R. 415

Rich v Australian Securities and Investment Commission [2004] HCA 42; (2004) 220 CLR 129

Shafron v Australian Securities and Investment Commission (2012) 86 ALJR 584

Spies v R [2000] HCA 43; (2000) 201 CLR 603

South Australia State Bank v Clark [1996] SASC 5499; (1996) 66 SASR

199

Steigrad & Ors v BFSL 2007 Ltd & Ors [2011] NZHC

1037

C Legislation

Bribery Act 2010 (UK)

Business Names Registration Act 2001 (Cth)

Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)

Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)

Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth)

Financial Services Reform Act 2001 (Cth)

Foreign Corrupt Practices Act 1977 15 U.S.C

Joint Stock Companies Act 1844 (UK)

Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth)

Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)

E Other

Australian Standard on Fraud and Corruption Control (AS8001-2008) and International Standard ISO31000:2009 Risk Management: Principles and Guidelines

Australian Stock Exchange, 2010 Australian Share Ownership Study, <http://www.asx.com.au/documents/resources/2010_australian_share_ownership_study.pdf> (viewed 7th June 2012)

<http://asicconnect.asic.gov.au> (viewed 1 June 2012)

Commonwealth, The HIH Royal Commission, The failure of HIH (2003) <http://www.hihroyalcom.gov.au/finalreport/index.htm> (viewed 25 May 2012)

Claessens, Stijn and Burcin Yurtoglu, 10 Focus: Corporate Governance and Development – An Update, (2012) Global Corporate Governance Forum <http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/cgf.nsf/Content/Focus10>

Deloitte, Director360° (2011) <http://www.deloitte.com/view/en_GX/global/press/dc1da3e2f7213310VgnVCM3000001c56f00aRCRD.htm>

<http://www.youtube.com/user/TEDtalksDirector> (viewed 7th June 2012)

<http://www.treasury.gov.au/contentitem.asp?NavId=037 & ContentID=1182> (viewed 10 August 2012)

Sir Adrian Cadbury, The Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance (1992) <http://www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/cadbury.pdf> (viewed 1 June 2012)

[1] Professor Michael Adams is the Dean of School of Law at the University of Western Sydney and any comments may be emailed to: Michael.Adams@uws.edu.au This DRAFT paper is from a presentation delivered at the 2012 Annual Corporate Update¸ held in Sydney on 30th May and in Melbourne on 5th June. The paper may only be quoted with author’s express permission.

[2] Peter Martin, ‘Housing a

Worry but Economy Booming, Says OECD’, Sydney Morning Herald

(Sydney), 23 May 2012,

3.

[3] Australian Financial

Review (2012) 5th June, 17.

[4] Commonwealth, The HIH Royal Commission, The failure of HIH (2003). <http://www.hihroyalcom.gov.au/finalreport/index.htm> (viewed 25 May 2012).

[5] Alice Klettner, Thomas Clarke, and Michael Adams, ‘Balancing Act – Tightrope of Corporate Governance Reform’ (2007) 59 Keeping Good Companies 648.

[6] Alice Klettner, Thomas Clarke and Michael Adams, ‘Corporate Governance Reform: An Empirical Study of the Changing Role and Responsibilities of Australian Boards and Directors’ (2010) 24 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 148.

[7] Michael Adams, ‘Are All

Directors Created Equal? Reassessing the Role of the Chair in the Light of

ASIC v Rich’ (2003) 55 Keeping Good Companies 204; Michael

Adams, ‘Officers’ Duties Under the Microscope’ (2005) 57

Keeping Good Companies 516; and Michael Adams, ‘Officers’

Duties – Are We Keeping Up With the Changes?’ (2008) 60 Keeping

Good Companies 344.

[8]

Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 180(2).

[9]

<http://www.treasury.gov.au/contentitem.asp?NavId=037 & ContentID=1182>

(viewed 10 August 2011)

[10]

[2012] VSC 94.

[11] [2012] FCAFC 6; (2012) 200 FCR 296; Gemma Morgan, ‘De Facto Directors and Duties – Chameleon Mining’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 222.

[12] Corporations and Markets

Advisory Committee, Parliament of Australia, Guidance for Directors

Report, (2010).

[13] The

Honourable East India Company, 1600

England.

[14] Joint Stock

Companies Act 1844 (UK).

[15] Jason Harris, Anil Hargovan

and Michael Adams, Australian Corporate Law, (LexisNexis:Butterworths,

3rd ed, 2011)

449.

[16] [2000] HCA 43; (2000) 201 CLR

603.

[17] [1996] SASC 5499; (1996) 66 SASR

199.

[18] [2002] NSWSC 171; (2002) 168 FLR

253.

[19] [2003] NSWSC 85; (2003) 174 FLR

128.

[20] Ibid.

[21] [2004] HCA 42; (2004) 220 CLR 129. For a

detailed discussion on this case, see Michael Adams, ‘Whether to Protect

or Punish: Legal Consequences of Contravening

the Corporations Act’

(2004) 56 Keeping Good Companies

592.

[22] [2002] NSWSC 171; (2002) 168 FLR

253.

[23] R v Williams

[2005] NSWSC 315; (2005) 216 ALR 113.

[24]

R v Adler [2005] NSWSC

274.

[25] ASIC v Vizard

[2005] FCA 1037; (2005) 145 FCR 57..

[26] [2005] NSWSC 738. For a

detailed discussion of this case, see: Michael Adams, ‘Officers’

Duties Under the Microscope’ (2005) 57 Keeping Good Companies

516.

[27] [2007] NSWSC 1330; (2007) 215 FLR

243.

[28] ASIC v MacDonald (No

11) [2009] NSWSC 287; (2009) 230 FLR 1 and penalties imposed at ASIC v MacDonald (No 12)

(2009) 259 ALR 116.

[29]

[2010] NSWCA 331; (2010) 247 FLR 140.

[30] [2010] NSWCA 332; (2010)

274 ALR 85.

[31] For more detailed discussions see Anil Hargovan, ‘Directors’ and Officers’ Duty of Care Following James Hardie’ (2009) 61 Keeping Good Companies 586 and Richard Head, ‘Directors and Officers Still in the Firing Line – A Guide to Managing Risk’ (2010) 62 Keeping Good Companies 57.

[32] (2012) 86 ALJR 522; see Michael Adams, ‘Lessons for Non-Executives from James Hardie Litigation’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 263.

[33] (2012) 86 ALJR 584; see

Anil Hargovan, ‘Raising the Bar for General Counsel and Company

Secretaries - High Court Decision

in James Hardie’ (2012) 64

Keeping Good Companies

260.

[34] [2009] FCA 1586; (2009) 264 ALR

201.

[35] [2011] FCAFC 19; (2011) 190 FCR

364.

[36] The Full Bench of the

Federal Court has remitted the matter of penalties to a single judge of the

Federal Court for determination.

Mr Forrest and FMG have appealed to the High

Court of Australia.

[37] [2011] FCAFC 717; (2011)

278 ALR 618.

[38] Leonie Wood, ‘Funder Gets $60m from Centro Deal’ Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 11 May 2012, 3.

[39] [2012] FCA 70; (2012) 87 ACSR 229; see Andrew Harpur, ‘It’s a Privilege – Company Secretary’s Notes of Legal Advice to Board Protected’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 156.

[40] [2011] NZHC 1037

(‘Bridgecorp case’); see Keith Thomas, ‘The Bridgecorp

Case – Could Creditors Stop a Company’s D&O Insurers Paying

Defence Costs to Directors?’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies

45.

[41] [1854] EngR 664; (1853) 43 E.R.

415.

[42] Diana Nicholson and Josh Underhill, ‘Government Releases First Tranche of Reforms to Company Officer Liability’ (2012) 64(2) Keeping Good Companies 70.

[43] Clancy Yeates, ‘Advisers Allowed “Opt-In” Exemption’, Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 23 March 2012, 3.

[44] Jason Harris and Nicholas Mirzai, ‘The Personal Property Securities Act and Company Secretaries’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 92.

[45] <http://asicconnect.asic.gov.au> (viewed 1 June 2012).

[46] Marnie Douglas, ‘Putting Workplace Health and Safety Laws to Work’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 89.

[47] Michael Adams and Marina Nehme, ‘No New Specific Legislation Required to Deal With “Greenwashing”’ (2011) 63 Keeping Good Companies 419.

[48] Australian Standard on Fraud and Corruption Control (AS8001-2008) and International Standard ISO31000:2009 Risk Management: Principles and Guidelines.

[49] Gavin Nicholson and Natalie Elms, ‘Corruption, Corporate Culture and the Board’s Responsibility’ (2011) 63 Keeping Good Companies 594; Michael Ahrens and Georgie Farrant, ‘Bribery of Foreign Officials – Key Steps in Mitigating the Risks’ (2012) March, the Australian Corporate Lawyer 14.

[50] Flora Gilkison, ‘Diversity and the Governance Double Glazing Trap’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 97.

[51] Adele Ferguson, ‘More Women Join Boards but Glass Ceiling Remains Intact’, Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 8 March 2012, 3.

[52] Editor, ‘EU Outlines Plan for Board Gender Quotas’ (London) (2012) April, Chartered Secretary 5.

[53] Ann-Maree Moodie, ‘International Governance – Leading a Truly Diversely-Composed Board’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 6.

[54] Identified as those notionally born after the World War II (between 1946 and 1961) by Bernard Salt in The Big Shift (Hardie Grant Books, 2004).

[55] Notionally born between 1962 and 1981 (then replaced with Generation ‘Y’ after 1982, and it is argued that there is a Generation ‘Z’ or ‘iGeneration’ from 1995 to now).

[56] See Editor, ‘Embracing Technology in the Boardroom by Moving Board Papers Into the Digital Realm’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 76.

[57] BYOD means ‘bring your own device or sometimes’ BYOT, bring your own technology.

[58] Ainslie MacGibbon, ‘Smarter Use of Home Devices’ Sydney Morning Herald (Sydney) 28 May 2012, 17.

[59] Greg Dooley, ‘2011 AGM Season – Providing Clues to What Lies Ahead’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 86.

[60] Claire MacMillan, ‘Impact of Regulatory Reforms on Executive Remuneration in Australia – AGMs in 2011’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 100.

[61] For a detailed discussion, see Australian Stock Exchange, 2010 Australian Share Ownership Study, <http://www.asx.com.au/documents/resources/2010_australian_share_ownership_study.pdf> (viewed 7th June 2012)

[62] Alice Klettner, Thomas Clarke and Michael Adams, ‘Corporate Governance Reform: An Empirical Study of the Changing Roles and Responsibilities of Australian Boards and Directors’ (2010) 24 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 148.

[63] In fact the author wrote a series of articles arguing this was the likely outcome: see Michael Adams, ‘The Convergence of International Governance – Where is Australia Heading?’ (2002) 54 Keeping Good Companies 14, 82, 144.

[64] Alan Dignam and Michael Galanis, The Globalization of Corporate Governance (Ashgate, 2009).

[65] Sir Adrian Cadbury, The Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance (1992) <http://www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/cadbury.pdf> (viewed 1 June 2012)

[66] Geoffrey Kiel and Gavin Nicholson, ‘The Changing Nature of Corporate Governance’ in Boards That Work: A New Guide for Directors (McGraw-Hill, 2003).

[67] Stijn Claessens and Burcin Yurtoglu, 10 Focus: Corporate Governance and Development – An Update, (2012) Global Corporate Governance Forum <http://www.ifc.org/ifcext/cgf.nsf/Content/Focus10> .

[68] For an interesting discussion of issues relating to transnational corporations, see Michael Head, Scott Mann and Simon Kozlina (eds), Transnational Governance: Emerging Models of Global Legal Regulation (Ashgate, 2012).

[69] Chee Keong Low (Ed), Corporate Governance: An Asia-Pacific Critique (Sweet & Maxwell Asia, 2002).

[70] Claessens and Yurtoglu, above n 70.

[71] John Farrar, ‘Developing Corporate Governance in Greater China’ [2002] UNSWLawJl 29; (2002) 25(2) UNSW Law Journal 462.

[72] Anona Armstrong, ‘Corporate Governance Standards: Intangibles and Their Intangible Value’, (2004) 17 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 97.

[73] Roman Tomasic, ‘Good Corporate Governance: The International Challenge’, (2000) 12 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 142.

[74] Bob Tricker, ‘Culture Dependence of Corporate Governance’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 27.

[75] Vicky Comino, ‘Towards Better Corporate Regulation in Australia’ (2011) 26 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 6.

[76] David Thomas, ‘Building With New BRICs’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 10.

[77] Satyajit Das, ‘A Vulnerable State – The Economic Outlook for Australia’ (2012) 64 Keeping Good Companies 15.

[78] Deloitte, Director360° (2011) <http://www.deloitte.com/view/en_GX/global/press/dc1da3e2f7213310VgnVCM3000001c56f00aRCRD.htm> .

[79] Alice Klettner, Thomas Clarke and Michael Adams, ‘Corporate Governance Reform,: An Empirical Study of the Changing Roles and Responsibilities of Australian Boards and Directors’ (2010) 24 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 148.

[80] Claessens and Yurtoglu, above n 70.

[81] Nelson Mandela, Lighting the way to a better future (South Africa, 2003).

[82] Note that a UK works inspector Lucy Deane, identified a clear link between asbestos and lung disease, in 1898!

[83] Niels Bohr (Danish physicist, 1885-1962) stated “prediction is very difficult, especially about the future”.

[84] <http://www.youtube.com/user/TEDtalksDirector> (viewed 7th June 2012).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ALRS/2012/1.html