Current Issues in Criminal Justice

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Current Issues in Criminal Justice |

|

The Bali Nine, Capital Punishment and Australia’s Obligation to

Seek Abolition

Amy Maguire[*] and Shelby Houghton[†]

Abstract

The executions of Australian nationals Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran in April 2015 brought capital punishment to the forefront of public consciousness in Australia. Indonesia carried out their death sentences, and those of six others convicted of drug offences, despite Australia’s determined advocacy for clemency. Their deaths represent a tiny fraction of the numbers killed in execution of the death penalty each year, but ought to prompt a renewed inquiry into the global practice of capital punishment and Australia’s position in relation to it. This article identifies the states which continue to impose the death penalty and those which oppose it. It then situates capital punishment as a human rights issue, and explores how Australia can fully undertake its international legal commitments through more prominent and effective advocacy for the abolition of the death penalty worldwide.

Keywords: death penalty – Australia – Indonesia – human rights – abolition – advocacy – international law – Bali Nine – Chan – Sukumaran

On 29 April 2015, Australian citizens Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran were executed by firing squad on the prison island of Nusakambangan in Indonesia. Five other foreign nationals, four from Nigeria and one from Brazil, and one Indonesian were also put to death that night. All of those executed had been convicted of drug offences. The Brazilian man, Rodrigo Gularte, was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. He was not aware until he walked to the execution yard that the authorities would kill him (Saul 2015). The only woman in the group scheduled for execution that day, Philippines national Mary Jane Fiesta Veloso, was given a last-minute reprieve in order to give testimony against a person accused of human and drug trafficking. Her death sentence has not been permanently commuted and could be reinstated (The Guardian (online) 28 April 2016). One Frenchman’s execution had previously been delayed while a legal challenge is considered in an Indonesian court (The Guardian (online) 22 June 2015). Indonesian President Joko Widodo has now authorised at least 14 executions to take place during his administration, which began in October 2014. Widodo has a policy of refusing all clemency applications for those sentenced to death following drug convictions (ANTARA News (online) 9 December 2014).

In the remainder of this introduction, we briefly discuss the case of Sukumaran and Chan, Australia’s lobbying on their behalf and the official responses to their executions. After that the article explores the death penalty in the Australian and international legal and political contexts, then considers capital punishment through the lens of international human rights law. Finally, we argue that Australia could enhance the legitimacy of its position in relation to human rights by becoming a vocal advocate for the abolition of capital punishment worldwide. The partiality of Australia’s advocacy in this context — that is, Australia’s tendency to publicly object to the death penalty only in cases where it will be imposed on Australian nationals — is not justifiable ethically or according to international legal obligations.

Sukumaran and Chan were arrested in Bali in 2005 and convicted of drug smuggling offences in 2006. They were imprisoned, mostly in Bali’s Kerobokan Prison, until their executions in early 2015. The two were found to be the ringleaders of a drug smuggling ring known as the ‘Bali Nine’. The other seven members of this group were sentenced to 20 years or life imprisonment and remain in Indonesian prisons to date. In their ten years of imprisonment, Chan and Sukumaran were widely accepted to have shown remarkable rehabilitation. Sukumaran had become an established artist and gained a university qualification in fine art. He had established art classes and other outreach initiatives for prisoners in Kerobokan. Chan had been ordained as a Christian minister and offered counselling to drug addicts and others in prison. He was married shortly before his execution.

The executions were carried out despite strong and consistent advocacy on the part of the Australian government. Foreign Minister Julie Bishop was particularly prominent in lobbying Indonesia for clemency for Chan and Sukumaran. In doing so, Bishop and others in government frequently emphasised the men’s rehabilitation as a primary justification for sparing their lives. On 12 February 2015, Bishop stated in federal Parliament:

Both men are deeply, sincerely remorseful for their actions. Both men have made extraordinary efforts to rehabilitate. Andrew and Myuran are the model of what penal systems the world over long to achieve ... A decade on from their crimes, Andrew and Myuran are changed men. They are deeply committed to a new path. Both men are paying their debt to society. With dedication and unwavering commitment, they are improving and enriching the lives of their fellow prisoners (Commonwealth of Australia 2015:656).

In its lobbying of Indonesia, Australia also emphasised its opposition to capital punishment in all cases. Foreign Minister Julie Bishop described Chan and Sukumaran’s sentence as a ‘grave injustice’. She noted Australia’s ‘strong opposition to the death penalty at home and abroad’ (Commonwealth of Australia 2015:656). However, beyond this general expression of ‘opposition’ to capital punishment, Australia did not emphasise specific human rights principles in its lobbying of Indonesia for clemency. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott appeared to advance a moral argument against the executions in February 2015, when he cited Australia’s financial and military aid to Indonesia following the Indian Ocean tsunami, perhaps with the aim of suggesting that Indonesia had an ethical obligation to spare Australian lives (Tufft 2015). This argument was received by some in Indonesia as a threat (ABC 2015a) and was not repeated by Abbott or others in government. Instead, Australian lobbying efforts coalesced around the rehabilitation argument and the restatement of Australia’s general opposition to capital punishment.

In executing Chan and Sukumaran, Indonesia arguably violated the rule of law as it is understood under international law and Australian common law, by preventing two separate courts from hearing legal claims due to be raised in May or June 2015. In the days prior to the executions, the Constitutional Court said that it would hold a hearing on 12 May 2015 into allegations that the original trial judges requested a bribe of $130 000 in return for reduced sentences of 20 years’ imprisonment (The Australian 2015). An Indonesian Judicial Commission was also intending to investigate allegations of corruption in relation to the case, perhaps as early as 7 May 2015 (SBS 2015).[‡] The rule of law requires that the state avoid the arbitrary exercise of its power by making that power subordinate to defined and legitimate laws, and ensuring that the state and every individual and organisation within it are subject to the same laws (Dicey 1915). Justice and the rule of law therefore require that all legal processes be concluded before capital punishment is imposed. By authorising the executions when legal appeals were outstanding, President Widodo demonstrated that the power of his office is not entirely subject to judicial process in Indonesia.

In calling for clemency for its nationals, Australia sought no more from Indonesia than Indonesia seeks from other states, where its nationals are subject to the death penalty, including for drug offences. At the time of Chan and Sukumaran’s executions in 2015, Indonesia was simultaneously seeking clemency for 360 of its nationals facing the death penalty in other countries, including 230 of these for drug offences (Lamb 2015). In March 2015, Indonesia participated in a High-Level Panel on the death penalty at the United Nations (‘UN’) Human Rights Council. Indonesia noted that it had operated a unilateral moratorium between 2008 and 2013, and claimed that it was only forced to reinstate the penalty for serious drug crimes due to the aggravated situation such crimes had created in Indonesian society (UN Human Rights Council 2015). Also in March 2015, President Widodo suggested that capital punishment could be removed from operation again if such a change were demanded by the Indonesian people (Thals 2015). However, this statement arguably alludes to the strong element of populism guiding the Indonesian approach to capital punishment for drug offenders (Lindsey 2015). There is also a strong strain of resistance to what are perceived as external attacks on Indonesia’s sovereignty and right to implement its own laws (Connelly 2015:6, 17; Tapsell 2015).

Hours after the executions, former Prime Minister Tony Abbott announced the ‘unprecedented step’ of recalling Australia’s ambassador to Indonesia (Grattan 2015). Australia has not withdrawn ambassadors in other cases where Australian nationals were executed overseas. Abbott also suspended all ministerial contact with Indonesia (Abbott 2015). Some commentators and members of the public called for the withdrawal of aid from Indonesia and the 2015–16 federal Budget did cut this aid, although it has been reported (Whyte 2015) that this would have happened regardless and was not a policy decision linked to the executions.

Opposition Leader Bill Shorten and his deputy, then Shadow Foreign Minister Tanya Plibersek, condemned the death penalty as barbaric and argued that its practice ‘diminishes us all’ (Plibersek and Shorten 2015). They described the executions as undermining the rule of law because they went ahead before the Indonesian Constitutional Court and Judicial Commission could hold their planned hearings relating to Chan and Sukumaran’s case.

Indonesia responded that Australia’s post-execution diplomatic actions were merely temporary signs of protest on Australia’s part, carried out in line with Australia’s diplomatic rights and not of great concern due to the continuing need the two countries have for each other (Topsfield 2015). This was an accurate assessment, with Australia returning its Ambassador in June 2015 (ABC 2015b). Australia represented the Ambassador’s withdrawal as a strong diplomatic statement, but it stopped short of other protest actions such as the targeted withdrawal of aid or suspension of military contact. Indonesia was no doubt well aware of Australia’s unwillingness to harm an important trade and strategic alliance. Indeed, Australia has been faced with the option to take action against other neighbouring Asian countries as a strategic move in the past, most notably when Singapore executed Australian national Van Nguyen in 2005. There were suggestions for Australia to boycott Singapore Airlines’ access to flying routes, or to impose trade sanctions in response (Grattan 2005 cited in Fullilove 2006:7). Yet these actions were not taken, perhaps because sovereign nations do not respond well to bullying (Fullilove 2006:7). Australia therefore sits in a precarious position — as Klein and Knapman (2011:106) posit, the more force used to exert its views, the greater the risk for Australia of inflaming bilateral tensions.

Ultimately, Australia’s advocacy for Sukumaran and Chan was determined and genuine but a failure on both key measures; Australia’s nationals were executed, along with six others, and Indonesia remains determined to carry out the death penalty against drug offenders. It is therefore timely and important for Australia and Australians to step back from the immediate case and confront the broader reality of capital punishment globally. Such an inquiry may empower Australia to adopt a more considered and effective strategy for opposing capital punishment and contributing to the global abolition movement.

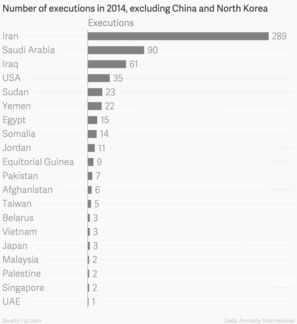

Each year, Amnesty International publishes a report on the imposition of the death penalty globally. The data it provides comprises minimum figures, because it only reports figures where reasonable confirmation exists. Some states, including China, treat such information as a state secret and the report therefore does not estimate executions or death sentences therein. Amnesty International (2015) can only estimate from available information that China executes and sentences to death thousands of people annually. On the reliable evidence available to it, Amnesty also found that, in 2014, 22 states carried out the death penalty and at least 2466 people were sentenced to death globally. At least 607 were put to death in states other than China (Amnesty International 2015). The chart below (Wener-Fligner 2015) represents executions by country in 2014, excluding China and North Korea, which did not report the necessary data:

Capital punishment is imposed globally for a wide variety of criminal offences, some of which do not exist as offences in Australia and many other states (Amnesty International 2015:8). Cornell University Law School’s Death Penalty Database reveals that, in Afghanistan, for example, the death penalty is available for adultery, consensual homosexual sex and apostasy (Cornell University 2012). In Iran, recidivist theft can attract the death penalty (Cornell University 2014a). Serious graft or bribery offences involving large sums of money may justify capital punishment in China (Cornell University 2014b). In Saudi Arabia, sorcery, witchcraft and repeat partaking of alcohol may all give rise to imposition of the death penalty (Cornell University 2011).

The methods of carrying out the death penalty similarly vary widely around the world. In 2014, one woman in the United Arab Emirates was sentenced to death by stoning, but no executions by stoning were carried out (Amnesty International 2015:7). Methods of execution reported in use during 2014 included beheading, hanging, lethal injection and shooting. In the United States (‘US’) in 2014, 3035 people were living on death row, including large numbers in California, Florida and Texas (Amnesty International 2015:13). Although all death sentences carried out in the US in 2014 involved lethal injection, some US states retain other methods of execution, including hanging, shooting, the gas chamber and the electric chair (Cornell University 2014c).

Capital punishment continues to be imposed against particularly vulnerable people, including those with mental and intellectual disabilities (Amnesty International 2014b). As a general principle of international law, mental and intellectual disabilities can constitute grounds to exclude criminal responsibility if the condition affects the person’s capacity in a certain way (Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, art 31.1(a)). Criminal responsibility is absolved if a disability affects a person’s capacity ‘to appreciate the unlawfulness or nature of his or her conduct, or capacity to control his or her conduct to conform to the requirements of law’ (Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, art 31.1(a)). The UN Economic and Social Council has affirmed this view in its Safeguards guaranteeing protection of the rights of those facing the death penalty (1984) that ‘the death sentence shall not be carried out on ... persons who have become insane’. Even in the US, where the death penalty is still readily used by some states, the Supreme Court has highlighted (Atkins v Virginia) the weight of international disapproval of the death penalty against mentally ill patients. The practice of capital punishment in the US is also known to be racially discriminatory, as it disproportionately targets African-American offenders (Drilling 2013–2014:858). In clear contravention of international law, several countries continue to sentence juvenile offenders to death, including Egypt, Iran, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Yemen (Amnesty International 2015:7).

Despite these troubling circumstances, human rights organisations have welcomed the growing international trend towards abolition of capital punishment. Amnesty International (2015) figures show that more than two-thirds of the states in the international community have abolished capital punishment in law or practice. These numbers include the 98 states that are ‘abolitionist’ for all crimes, seven further states which do not allow the death penalty for ‘ordinary crimes’ (which means that the states in question only retain the death penalty for exceptional crimes, for example those committed under military law). It also includes 35 states that have not carried out executions for ten years or more and are believed to have a policy against capital punishment (Amnesty International 2015:64–5). All states in the Americas other than the US have either abolished or ceased employing capital punishment. Similarly, Belarus is the outlier in Europe and Central Asia, with no other state in that region imposing the death penalty.

In 1998, the European Union (‘EU’) made it a precondition of membership that states abolish capital punishment in their domestic legal systems (Hood and Hoyle 2009:22). The EU further promotes the goal of universal abolition (EU Guidelines on the Death Penalty 2008). Canada has demonstrated its commitment to abolition by refusing to extradite defendants to the US where no assurance has been given that those defendants will not be put to death if convicted (United States v Burns). The United Kingdom has a longstanding policy of opposing the death penalty in all circumstances and is committed through government policy to work for global abolition (Human Rights and Democracy Department 2011).

Australia sits at a unique juncture in the international community, considering that the Pacific region is the only ‘death penalty free zone’ while the Asian region is responsible for more executions than any other region globally (Doherty 2015). Having removed capital punishment from its penal code in 2002, Fiji confirmed the abolitionist position of the Pacific states in February 2015 by also removing the death penalty from its military code. Fiji’s Attorney-General Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum sought Parliament’s support for this final stage of abolition by reference to Fiji’s Constitution, which guarantees the right to life (Sayed-Khaiyum 2015). Fiji’s move was welcomed by the international abolition movement as further proof that capital punishment is not an acceptable contemporary form of punishment and that the goal of universal abolition is getting closer (Gaughran 2015; France Diplomatie 2015).

In the early colonial period in New South Wales, imported English law authorised capital punishment for many crimes, while permitting the Governor to commute sentences of death (Letters Patent 1787 cited in Lennan and Williams 2012:663). Up to 90 people per year may have been executed in Australia during the 1800s (Potas and Walker 1987) for crimes ranging from murder to forgery to sheep theft (Mukherjee et al 1986). By the time of Federation in 1901, there was significant divergence between the Australian colonies in terms of the number of capital crimes and the frequency of imposition of capital punishment (Lennan and Williams 2012:667–8). The use of the death penalty declined significantly from this point, with 114 prisoners executed in Australia during the 20th century (Jones 1968).

The last person executed in Australia was Ronald Ryan, who was hanged in Melbourne’s Pentridge Prison in 1967, having been convicted of killing a prison officer during an escape. Ryan’s lawyer always maintained his innocence (Australian Coalition Against the Death Penalty 2004), and Ryan’s hanging has been described (Duff 2014) as a tipping point beyond which public and political support for capital punishment in Australia disappeared entirely.

In subsequent years, capital punishment was removed from the statute books in all Australian jurisdictions and it seems unlikely that capital punishment would be reintroduced in Australia in future. Although the death penalty is raised periodically in public debate, particularly in the wake of horrendous crimes, no senior officials have lobbied for its reinstatement (Abjorensen 2015). There have, however, been comments made by Australian politicians recording support or acceptance for the use of the penalty in some circumstances (Marr 2010). In 2010, then Opposition Leader and former Prime Minister Tony Abbott told the Herald Sun that despite his opposition to the use of the death penalty:

I sometimes find myself thinking, though, that there are some crimes so horrific that maybe that’s the only way to adequately convey the horror of what’s been done ... I mean, you’ve got to ask yourself, what punishment would fit that crime? That’s when you do start to think that maybe the only appropriate punishment is death (Toohey 2010).

In 1973, the Australian Parliament passed legislation prohibiting capital punishment for any federal crime (Death Penalty Abolition Act 1973 (Cth), s 4). Some states did not remove capital punishment formally until after that time, but any death sentence handed down after 1973 was commuted by the courts to life imprisonment (Lennan and Williams 2012:668–81). Current Australian law is unequivocal in its rejection of capital punishment.

In 2010, Australia passed the Crimes Legislation Amendment (Torture Prohibition and Death Penalty Abolition) Act 2010 (Cth), s 6 of which had the effect of prohibiting capital punishment in all Australian jurisdictions. Further, Australia acted to ensure that a person may only be deported to another country to face trial where an assurance has been given that the death penalty will not be imposed as a punishment (Extradition Act 1988 (Cth), s 22(3)(c)). These legislative changes enacted Australia’s commitment to the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Aiming at the Abolition of the Death Penalty (1989). In his second reading speech for the 2010 Bill, then Attorney-General Robert McClelland explained Australia’s abolitionist stance:

[The proposed Bill] will ensure that the death penalty cannot be reintroduced anywhere in Australia in the future. ... Such a comprehensive rejection of capital punishment will also demonstrate Australia’s commitment to the worldwide abolitionist movement and complement Australia’s international lobbying efforts against the death penalty. ... [T]his bill contains important measures which again demonstrate this government’s ongoing commitment to better recognise Australia’s international human rights obligations (Commonwealth of Australia 2009:12197).

The Rudd and Gillard Labor Governments acted in a range of ways to demonstrate their commitment to the abolition of capital punishment. During those administrations, Australia repeatedly called on other states to abolish the death penalty, sponsored UN General Assembly resolutions proposing a moratorium on executions, and lobbied for clemency for all Australian nationals facing execution (Carne 2011:47–8). Australia also established new guidelines for the international law enforcement efforts of the Australian Federal Police following the conviction of Chan, Sukumaran and the other members of the Bali Nine (Carne 2011:49). These guidelines require senior AFP management to consider whether and how to provide assistance to foreign law enforcement agencies in cases where it is possible that a person may face the death penalty as an eventual result of that assistance (AFP Governance 2010).

At the height of public awareness of the Sukumaran and Chan death sentences, it became clear that Australian public opinion is not as unequivocal as Australian law in relation to the death penalty. A 2009 poll found a clear majority preferred imprisonment to capital punishment as a penalty in Australian murder trials, however, 53 per cent of those polled said death sentences against drug offenders in Southeast Asia should be carried out (Roy Morgan Research 2009). In 2015, a Roy Morgan poll showed 52 per cent supported the death penalty in those particular circumstances. A contrasting Lowy Institute (2015) poll found that 62 per cent of Australian adults opposed the executions of Chan and Sukumaran. These conflicting results demonstrate the difficulty of gauging public opinion on capital punishment.

In online commentary surrounding the executions in Indonesia (The Drum 2015; Hood and Hoyle 2015; Maguire 2015), a strain of public opinion emerged to emphasise that Sukumaran and Chan ‘knew what was coming to them’, particularly as the prospect of capital punishment for drug offences in Indonesia is widely publicised. This view appears resistant to the argument that justice systems are not (and arguably cannot be) consistent in their application of punishments across all cases. This much is apparent in the April 2015 executions themselves; the eight men killed were convicted of a very wide range of drug offences, from trafficking to simple possession. The differential outcomes for other members of the Bali Nine, and other Australians convicted of drug offences in Bali (including, for example, Schapelle Corby), demonstrate that it is extremely difficult for prospective offenders or others to predict how they may be punished for criminal activities.

The Australian Government’s advocacy for Chan and Sukumaran stood at odds with the position of some in the community, who would have left the men to their ‘just deserts’ (Marcus 2015). Indeed, Julie Bishop (Commonwealth of Australia 2015:656) questioned the accuracy of the poll finding that a majority thought the executions should proceed. In taking a principled stand in this case, Australia was effectively standing for human rights. However, as noted above, Australia did not strongly emphasise human rights arguments in its advocacy for Sukumaran and Chan. Australian officials may have determined that Indonesia would not respond well to lobbying grounded in human rights discourse, particularly due to the strong strain of nationalistic sentiment supporting the use of capital punishment against foreign drug offenders in Indonesia. Australia was certainly careful to consistently emphasise its respect for Indonesia’s sovereignty throughout its advocacy, and Indonesia repeatedly defended its entitlement to prosecute its own laws free from foreign interference.

Australia might also have avoided human rights ‘talk’ because the current government tends not to express itself through these principles. For example, the Coalition has consistently rejected proposals for a Human Rights Act or similar mechanism, on the basis that the common law and existing statutory provisions are sufficient to protect human rights. Tony Abbott (in Margarey and Jordan 2010) put forward such a view while in Opposition when he stated: ‘Bills of rights are left-wing tricks to allow judges to change society in ways a parliament would never dare.’ In the following section, we explore the human rights arguments at the heart of opposition to capital punishment, and conclude by arguing that Australia ought to establish itself as a key advocate for abolition.

There are three central arguments against capital punishment based in international human rights law: that it violates the right to life; that it contravenes the prohibition on capital punishment for all but the most severe crimes; and that it constitutes torture. These arguments are a central, if not always emphasised, element in Australia’s opposition to the death penalty. They are crucial grounds for advocacy which Australia can use more consistently in its efforts towards global abolition.

The right to life is the foundation principle of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the international legal framework that has been built around it. Article 3 of the Declaration explicitly states ‘everyone has a right to life’, reflective of the post-WWII focus on entrenching human rights protections and preventing further mass state-sanctioned killings (Bae 2007:2). Protection for the right to life was entrenched in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (‘ICCPR’), which states ‘no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life’. As the Secretary General of Amnesty International Salil Shetty (2014:44–5) explained, art 6(2) of the ICCPR codified a ‘limited retention’ of the death penalty ‘only for the most serious crimes’ in states which have not yet abolished the punishment. It also included various safeguards against the use of the penalty for children and pregnant women, with the view for the death penalty to be gradually phased out (Lehrfreund 2013:25). Saul Lehfreund (2013) has characterised this residual acknowledgement of the death penalty in art 6(2) as a product of its time, and by no means evidence that the right to life can be derogated from.

Indeed, there are no limitations to the right to life under human rights law — it must always be respected (although, in situations of armed conflict, international humanitarian law holds sway and seeks to regulate the realities of the loss of human life (Byrnes 2007:35)). The Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR (1989), to which Australia is a party, obliges states to work for the abolition of the death penalty globally. States are obliged to refrain from imposing capital punishment and from removing people to other states where it is reasonably possible that they will be subject to capital punishment. For the right to life to function as an effective basis for argument, it is important that it be advanced in every case, even where an individual facing capital punishment has been convicted of taking another’s life. In advocating for clemency for Chan and Sukumaran, Australia implicitly acknowledged that a person’s guilt or innocence — or the gravity of the person’s crimes — should not determine whether or not his or her claim for a reprieve is worthy of support.

The ICCPR acknowledges that some states continue to impose capital punishment, despite the fact that this violates the right to life. ICCPR, art 6(2) obliges those states to only impose capital punishment for the most serious of crimes. There is no legal standard to assess which crimes are sufficiently serious for this purpose; however, some guidelines are available. The UN Economic and Social Council resolution on ‘Safeguards guaranteeing protection of the rights of those facing the death penalty’ (1984) states the scope of ‘most serious crimes’ should ‘not go beyond intentional crimes with lethal or extremely grave consequences’. Further, the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Phillip Alston, has also posited that the concept should be interpreted in a limited way only to cover ‘intentional killings’ (Shetty 2014:46). Alston (2007:53) notes that the UN Human Rights Committee and other bodies deem a ‘serious’ crime to be one that occurs ‘in cases where it can be shown that there was an intention to kill which resulted in the loss of life’.

As outlined above, some states execute people for actions that would not be regarded as crimes in Australian society, such as adultery in Afghanistan or sorcery in Saudi Arabia. These crimes result in no intentional killings, yet they are punished in such a way by the state. Such executions can thus be seen as a breach of international standards, as they do not meet the ‘most serious crimes’ threshold. Indonesia, among other countries, has been criticised for continuing to impose the death penalty for drug trafficking offences. Yet, in 2007, the Indonesian Constitutional Court in Sianturi v Indonesia took the step of ruling the use of capital punishment for drug offences was properly characterised within ‘the most serious crimes’ and in line with international and customary law, on the basis of the severe impacts that drug-related crimes have on Indonesian society. This decision is starkly contrasted with the sentiment of the UN. In 2013, the UN Human Rights Committee (2013) condemned the country’s continued use of the death penalty for drug trafficking as not meeting the threshold of ‘most serious crimes’. The Committee instead recommended a review of legislation ‘to ensure that crimes involving narcotics are not amenable to the death penalty’ (2013:10). In a follow-up evaluation last year, the Committee again deplored Indonesia’s continued execution of prisoners in drug cases and took the rare step of awarding Indonesia an ‘E’ rating on the committee’s rating scale of ‘A’ to ‘E’ (UN Human Rights Committee 2015).

Further, in cases where capital punishment is imposed for its alleged deterrent effect, rather than as a punishment for intentional killing, the practice is arbitrary and is said to contravene the basic standard that ‘no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of life’ (Byrnes 2007b in Lynch 2009:535).

The prohibition of torture is a jus cogens standard under international law (de Wet 2004:97).[§] Capital punishment is a violation of the right to freedom from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (ICCPR, art 7; Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment). Not only does capital punishment inflict inhumane pain and suffering at the time of execution, but it imposes long periods — sometimes many years — of mental anguish on death row inmates. Further, some people sentenced to death have been subjected to torture as a means of extracting their confessions. Shetty (2014:50) reports the prevalence of this practice in Iraq in recent years, particularly in relation to people convicted of offences under the Anti-Terrorism Act 2005 (Cth).

Capital punishment is torturous because those subject to it are forced to anticipate their killing by the state on a nominated date and using a certain method. This experience is starkly at odds with the more typical human tendency to avoid awareness of impending mortality. Knowing their fate, however, prisoners may wait many years on death row. Even in cases where offenders have made determined and persuasive efforts to rehabilitate, capital punishment robs them of the anticipation of a constructive future. Sukumaran and Chan were widely accepted to have rehabilitated themselves and could likely have accepted the quality of life available as lifelong prison inmates in Indonesia. Instead, for the two Australians and thousands of others, the time on death row entails multiple cycles of hope and despair; a new legal challenge might be the one needed to alter the sentence, or it may not generate much positive change.

In addition, none of the methods used to carry out death sentences can be shown to be ‘humane’ or painless. Lethal injection, widely used in the US, may sometimes appear painless only because a paralysing agent is injected first. The UN Committee on Torture (2014) recently expressed concern that procedural problems in some US jurisdictions have resulted in the imposition of ‘excruciating pain and prolonged suffering’ for condemned prisoners during their executions. It is impossible to imagine the pain and suffering inflicted by the various other means of execution still available globally, including death by firing squad, hanging, electrocution, gassing and stoning. In 2008, Indonesia’s Constitutional Court was explicitly asked to consider whether the method of death by firing squad amounted to torture (Amrozi Bin Nurhasyim v Republic of Indonesia, also known as the ‘Firing Squad Case’ 2008). Judge Mohammad Mahfud concluded that it was not, instead finding that any feeling of pain was a logical and thereby unavoidable consequence of the lawful execution of a prisoner (McRae 2012:8),

Capital punishment also inflicts torture on the families and loved ones of those subject to it. At one extreme, the families of Chan and Sukumaran faced the constant, looming fear of the executions being carried out. As Roberts (2015) reported, they were then forced to say a final goodbye, knowing that their loved ones would be shot the next day. In some states, such as Belarus, an opposite form of torture is apparent; families are kept in the dark and do not find out about the executions until after they occur, denying them the opportunity to say goodbye (Shetty 2014:42). In 2013, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture stated that ‘secrecy is an especially cruel feature of capital punishment, highlighting the need for total transparency and avoidance of harm to innocents in the whole process’ (Méndez 2013:52).

Arguments against capital punishment grounded in human rights theory reflect the immutable value of human life. Nevertheless, not all people find human rights arguments persuasive, and instead may believe that people facing execution overseas should suffer the consequences of actions committed in foreign jurisdictions. In this context, there are several strong pragmatic arguments against capital punishment. As abolition advocate Roger Hood wrote in 2002, recent decades have confronted ‘those who still favour capital punishment “in principle” ... with yet more convincing evidence of the abuses, discrimination, mistakes, and inhumanity that appear inevitably to accompany it in practice’ (Hood 2002:7).

Judges and juries can make mistakes, but capital punishment is irreversible. The standard of proof in criminal cases — often ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ — does not preclude doubt altogether. Indeed, in the US since 1973, 150 people have been exonerated after being sent to death row (Amnesty International 2015:13). Drilling (2013–2014:859) has recently suggested that the American public may be losing faith in capital punishment, due in part to the rising numbers of DNA evidence-based exonerations. Clearly, the practice of capital punishment risks the killing of innocents. Former Australian Prime Minister John Howard objected to the death penalty (Mitchell 2013), not so much on the basis of human rights concerns, but for ‘pragmatic’ reasons, including the need to prevent the execution of innocents.

The Indonesian justice system is a salient case in this context:

Corruption has been so extensive in the Indonesian judiciary that an external audit conducted in 2001 found that ‘the entire judicial system would “probably collapse” were it not for unlawful payments to the Attorney-General’s office’ ... (Linton 2006 cited in Lynch 2008–2009:558).

Where the integrity of a justice system is in doubt, the likelihood is greater that innocents may be subjected to capital punishment (Lynch 2008–2009:559). In the case of Indonesia, corruption is so prevalent that specially designated corruption courts have even fallen victim to the practice. The state-funded Corruption Eradication Commission (more commonly known by its Indonesian acronym KPK) and the Tipikor Court were established to ‘circumvent entirely a judicial system known to be complicit in protecting corruptors’ (Fenwick 2008:413). However, as Butt and Schutte (2014:612) note, the KPK arrested an ad hoc judge of the Semarang Tipikor Court in 2012 for receiving a Rp 150 million bribe for a corruption case she was presiding over. If a judicial system specifically responsible for eradicating corruption is not immune to the practice, the question must then be asked whether the broader legal and appeals process is infallible. Advocates for the death penalty must be challenged to consider whether the death penalty should be maintained in countries where the true independence of the legal system cannot be guaranteed.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo argues for the death penalty to deter drug traffickers, whom he regards as responsible for creating a massive drug problem in Indonesian society (Stoicescu 2015). There is no doubt that drug addiction can have wide-ranging and highly damaging impacts on individuals, families and communities. In its advocacy for Sukumaran and Chan, Australia did not seek to minimise the significance of their crimes. However, the executions that Widodo termed ‘shock therapy’ will not address drug addiction or promote harm reduction programs. Nor has it been established more generally that capital punishment is any more effective a deterrent to serious criminal offending than life imprisonment (Shetty 2014:48–9). Indeed, an economic analysis (Cohen-Cole et al 2009:364) of possible deterrent effects could not conclude that capital punishment is or is not an effective deterrent of murder, and that it is impossible to make inferences on the magnitude of any deterrent effect, particularly when it is ethically abhorrent to experiment with the death penalty (Hood and Hoyle 2015).

In some cases, notably for some contemporary terrorist offenders, the likelihood of the death penalty being imposed against them can actually motivate offending. Bali bombers Amrozi, Mukhlas and Imam Saumudra were quoted (SMH 2015) as saying that they dearly wished for martyrdom, and they welcomed their death sentences in court.

It may be natural for human beings to wish for revenge when they are wronged. As Byron (2000:307) has written, proponents of capital punishment sometimes seek to clinch the rightness of their cause by asking: ‘What if it had been your daughter or son who was murdered? Wouldn’t you demand the death penalty then?’ But revenge is a very partial and emotive idea — the sort of wrongs that one person might demand revenge for and those that someone else might seek retribution over may be very different. If revenge were the genuine and appropriate motivating force behind criminal punishment, it would arguably make more sense to bypass the courts and instead permit victims of crime to decide on appropriate sentences for convicted criminals.

Instead, members of the Australian community generally accept that powers over criminal trials and punishments are properly handed over to courts, to enable the justice system to set its sights above retribution. The courts are better placed than individuals in the community to decide whether an offender ought to be removed from society for a time or permanently, and to balance the various goals of punishment including deterrence, incapacitation, restorative justice and rehabilitation. This is not to say that the experiences of victims of crime should not be taken into account by the courts in sentencing but that, as Byron (2000:313) asserts, ‘the pursuit of vengeance has no place in a just society or healthy community’.

Imposing capital punishment debases a legal system. When it imposes the death penalty, a legal system effectively says to an offender: ‘It is wrong for you to kill (or commit whatever the relevant crime is), and to prove this you must be put to death.’ This reduces the state to inflicting violence against the person, in circumstances where it is typically seeking to sanction the use of violence by an offender. Further, the use of capital punishment reduces the responsibility of the state and society to confront the most serious crimes and explore how criminal behaviour ought to be addressed. As Drilling has recognised, there is no justification for the retention of capital punishment when practical and socially acceptable alternatives exist:

[The US] federal and state governments now have advanced prison systems, and with the emergence of life without the possibility of parole as a sentencing option, capital punishment is unnecessary as the primary defense for even the most atrocious crimes (Drilling 2013–2014:850).

Drilling’s argument implicitly acknowledges that certain criminal behaviour is sufficiently reprehensible that the offender should not be permitted to rejoin society in his or her lifetime. It also notes that the total incapacitation of offenders can be achieved by a life imprisonment sentence, such that it is never necessary for the state to kill in response to a crime.

The international community has seen a definitive push towards universal abolition of the death penalty. In 2007, for example, the UN General Assembly passed Resolution No 62/149 with an overwhelming 104:54 majority adopting a moratorium on executions (Lehrfreund 2013 cited in Hood and Deva 2013:25). Five years later, the General Assembly adopted a fourth resolution calling for an end to the use of the death penalty. This time, 111 countries voted in favour, and only 41 voted against, with 34 abstaining countries. This pattern, according to Drilling (2013–2014:860–1) can be explained by an increasing awareness of capital punishment as a human rights issue. On the eve of World War II, before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or any such international law instruments existed, only eight countries had completely abolished the death penalty (and a further six for ‘ordinary crimes’ only) (Drilling 2013–2014:860–1). Today, there are 101 abolitionist countries (Amnesty International 2014a) — and burgeoning pressure by human rights groups, governments and treaties calling for others to change.

Proponents of abolition see the value of a justice system directed towards rehabilitation and restorative justice. This is a forward-looking approach to punishment, which acknowledges that offenders continue to be members of society and the ideal outcome is that they can be reformed and make positive future contributions.

Chan and Sukumaran were apparently rehabilitated, model prisoners, who not only repented their own crimes but helped other prisoners to acknowledge and seek to address their wrongdoing. Geoffrey Robertson, the renowned human rights lawyer, said at a candlelight vigil in Sydney the night before the executions that Indonesia was ‘not killing “the same people who committed the crime”’ (Sky News 2015). Yet these arguments about rehabilitation have been explicitly rejected by the Indonesian Constitutional Court. In 2007, the Court handed down a split decision in a case relating to Australian prisoners — including Chan and Sukumaran — commenting that the correct aim of punishment was to restore the ‘social harmony of society’, rather than reform an individual prisoner (Klein and Knapman 2011:103).

With such diversity in the reasons why states believe capital punishment is carried out, it is crucial that abolitionist advocacy be directed at the policy and practice of capital punishment rather than as critique that could be seen as insulting or culturally insensitive to states that maintain the practice.

In the weeks following the executions of Chan and Sukumaran, some prominent commentators from across the political spectrum have advocated for Australia to build its anti-death penalty advocacy worldwide. Former Howard Government Minister Peter Reith (2015) asked whether it should make any difference to Australia’s response if a planned execution involves Australians or not. Current Coalition Member Philip Ruddock has approached the diplomats of other states whose nationals have been or face execution in Indonesia, asking them to join with Australia in advocating for abolition. Ruddock said: ‘I think it is timely that Australia indicates it has a principled position on this matter and that we’re prepared to be on the front foot in advocating change’ (McInerny 2015).

It remains to be seen whether these efforts will generate broader community or official support for the abolitionist movement. In other areas, it is arguable that Australia’s foreign policy is becoming more isolationist rather than directed towards effective regional or global engagement. For example, the 2015–16 federal Budget saw foreign aid drop from A$5.03 billion in 2014–15, to a projected A$4.05 billion in 2015–16 (Refugee Council of Australia 2015). Indonesia in particular was stripped of its aid funding, and is said to have had its DFAT-administered aid cut by 40 per cent. If, in the future, Australia seeks to change the policy stance of other states to capital punishment, it risks rebuff on the basis that it provides little support in other areas in times of crisis.

For Australia to move towards a stronger abolitionist position in the future, an early consideration should be which means of advocacy will be most effective. Withdrawing ambassadors in protest, as happened following the executions of Sukumaran and Chan, is unlikely to change the policy positions of foreign governments. Other efforts that may be more effective include increased engagement and dialogue, working with Indonesia and other death penalty states to free their nationals facing capital punishment in foreign jurisdictions, and developing nuanced bilateral and regional approaches to drug trafficking. While all useful practical solutions, the problem is these rely on Australia being perceived as a consistent objector to capital punishment in the first place in order to influence other nations.

To be a serious abolitionist country, Australia must be committed to taking a clear and principled opposition to the death penalty in all circumstances. Despite what Lennan and Williams (2012:694) call a ‘continued affirmation’ of Australia’s stance against the death penalty, as discussed above, Australia was loath to emphasise human rights arguments in lobbying for clemency in Sukumaran and Chan’s case. With its dualist approach to the domestic incorporation of international law (Rothwell et al 2014:206), Australia can afford to be selective in its commitment to human rights. Indeed, successive governments have taken advantage of the fact that international law is not automatically absorbed into Australian domestic law. For example, Australia has given its belated assent to the principles contained in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007); however, no action has been taken to incorporate these principles into Australian law. This selective approach is noteworthy, as it undermines the international image Australia regards itself as holding. Australia depicts itself as a responsible member of the international community and campaigns internationally on a range of human rights standards. Yet Australian governments tend to be highly selective in the incorporation of those standards in domestic legislation and policy.

A number of commentators (Sifris 2007; Harrison 2006; Klein and Knapman 2011) have also highlighted a perceived inconsistency in the way Australia has been complicit in the use of death penalty in its bilateral relationships when dealing with international crime. The involvement of the Australian Federal Police (‘AFP’) in the arrest of the Bali Nine members is of particular relevance at this point. In April 2005, the AFP sent a letter to their Indonesian counterparts, informing them:

The AFP in Australia have received information that a group of persons are allegedly importing a narcotic substance (believed to be Heroin) from Bali to Australia using 8 individual people carrying body packs strapped to their legs and back’ and that they should ‘take what action they deem appropriate (Rush v Commissioner of Police at [22]).

The Indonesian National Police acted on this information, and arrested the members (including Chan and Sukumaran) before they could return to Australia. As Ronli Sifris (2007:84) argues, if Australia was serious about its abolitionist standpoint, it could have waited until they committed the actual act of drug trafficking on Australian soil — where they could be tried in accordance with Australian laws and without the possibility of capital punishment being inflicted.

This line of criticism, however, has been strongly refuted by the AFP. Following the May 2015 executions of Chan and Sukumaran, the leaders of the AFP gave an hour-long press conference in which they defended their actions in the 2005 arrests, and for the first time explained what information they held about the drug syndicate at that time. AFP Commissioner Andrew Colvin stated that ‘the simple facts are that at the time we were working with a very incomplete picture ... We were not in a position to arrest any of the Bali Nine prior to their departure from Australia’ (AFP 2015:2). Deputy Commissioner Michael Phelan countered suggestions that the members could have been charged with conspiracy to commit the crime before actually leaving Australia by saying ‘if we had charged someone with conspiracy at the time, a first-year lawyer would’ve been able to walk at first hearing. We had no evidence’ (AFP 2015:8). Further, Deputy Commissioner Phelan argued that waiting for the suspects to return and arresting them after the commission of the anticipated crime could have risked the chances of a successful prosecution of the wider drug syndicate (AFP 2015:2). The decision to provide information to Indonesian authorities was therefore seen by the AFP as the most effective option to stop the drug trafficking and limit the effect of the wider syndicate.

While a detailed examination of the laws and policies regulating Australia’s information sharing with retentionist nations is outside the scope of this article (see, for example, Lennan and Williams 2012), the underlying premise can, and should, be further interrogated. The Law Council of Australia (2010:2) has previously argued that ‘Australia’s leadership and credibility in this area has been undermined in recent years by an inconsistent and equivocal approach to the provision of agency to agency assistance in death penalty cases’. Klein and Knapman (2011:110) and Sifris (2007:107) similarly take the view that in providing international cooperation with law enforcement agencies, Australia is privileging its bilateral relationships at the expense of enforcing a strong abolitionist stance. According to Malkani: ‘The abolition and opposition of the death penalty is not a public policy objective that can be set aside when expedient to do so, and therefore assistance should be withheld when assurances are not forthcoming, regardless of the State interest in combating crime’ (2013:549). The question must then be asked, how can Australia exert a strong moral influence over its Asian neighbours, if it cannot even take a consistent approach to capital punishment?

It is acknowledged there are some practical difficulties in ensuring uniform opposition to the death penalty. Sam Garkawe (2013:101–2) draws a distinction between this so-called ‘idealist’ approach, which advocates curtailing interaction with retentionist nations in all circumstances where capital punishment is involved, and a ‘constructive engagement’ approach, which sees the benefit of maintaining relationships to be in a better position to then influence the nations to abolish the death penalty. He suggests the latter, more cooperative approach, as a more effective means of actually persuading these nations to follow Australia’s abolitionist stance. Further as Lorraine Finley (2011:96–8) argues, it could be seen as unreasonable for Australia to limit all interaction with retentionist nations, as it may have a ‘chilling effect’ on international crime going unpunished.

To this end, it is argued Australia will be in the strongest position to influence its retentionist neighbours by continuing to pursue this approach of constructive engagement. A recent request for information sharing between Australia and Indonesia is illustrative of the power of this approach. In January 2016, young Indonesian woman Jessica Kumala Wongso was charged with allegedly murdering her friend in Jakarta with a cyanide-laced coffee (Sydney Morning Herald 2016). Wongso had previously been a student in Australia, leading Indonesian authorities to request information regarding her history and criminal record from the AFP. The AFP only agreed to cooperate on the strict condition that the murder suspect would not face the death penalty if found guilty of the crime. Further, the information was only provided with ministerial approval — in line with the AFP National Guideline on International Police-to-Police Assistance in Death Penalty Situations. A spokeswoman for federal Justice Minister Michael Keenan confirmed that ‘the Indonesian government has given an assurance to the Australian government that the death penalty will not be sought nor carried out in relation to the alleged offending’ (Topsfield and Rosa 2016). By providing information in this way, Australia can maintain bilateral relationships and the benefits that information sharing brings in addressing transnational crime, while still encouraging regional neighbours to move away from capital punishment. Although this approach may enable only a slow transition, it at least shifts momentum away from a reliance on the death penalty as an answer to crime. Further, this approach is in line with what Bharat Malkani (2013:550) argues is an obligation on abolitionist states to ‘ensure that assistance is only provided when assurances have been received that the death penalty will not be imposed as the result of any such aid or assistance’.

At a broader level, continued advocacy against the death penalty in all situations would enhance Australia’s perceived legitimacy on the issue. Australia could follow the lead of the United Kingdom in developing a foreign affairs public strategy aiming at universal abolition (Amnesty International et al 2015).[**] In future lobbying efforts, Australia could be seen as a consistent and principled opponent of capital punishment globally. If Australia lobbies key allies like China and the US against capital punishment, then specific advocacy efforts may be less likely to be received as attacks on the state in question. In this context, Michael Fullilove (2006:6) argues ‘vigorous opposition to capital punishment in general is likely to bolster a government’s credibility in opposing specific executions’. Acknowledging the difficulty of protesting every case of the death penalty worldwide, he suggests Australia should instead focus on developing a ‘regional coalition’ against the death penalty. By concentrating efforts in South East Asia, rallying countries who already have a de facto stance against capital punishment — such as South Korea (Bae 2007:2) — and urging them to make it a formality, Australia would be seen to be taking a principled stance on the issue, and thus could claim greater legitimacy in times when Australians face execution overseas (Fullilove 2006:6).

The Australian Government strongly condemned the execution of two of its nationals in Indonesia in April 2015. More recently, further steps have been taken to demonstrate a broader commitment to abolitionist advocacy. Notably, the Human Rights Sub-Committee of the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade inquired into ‘Australia’s Advocacy for the Abolition of the Death Penalty’ (Parliament of Australia 2015). On 5 May 2016, the Committee released a report, ‘A World Without the Death Penalty’, which included 13 recommendations for enhancing Australia’s abolitionist advocacy (Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade 2016). The report has been tabled in Parliament, but the Government is yet to respond (Maguire 2016).

Further, Foreign Affairs Minister Julie Bishop announced in September 2015 that Australia would seek a seat on the UN Human Rights Council in 2018–20. Bishop noted that such a position would be used to campaign against capital punishment globally (O’Malley 2015). Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull is reported to be more supportive of Australia’s international engagement on such matters than his predecessor (O’Malley 2015).

The challenge now is to craft a long-standing and fruitful response to the deaths of Chan, Sukumaran and all others who face this ultimate punishment. The execution of human beings by the state should be opposed wherever it is carried out, and whomever is its subject. Australia can take on a position of ethical strength by broadening not only its advocacy, but also its range of argument. The wide range of human rights-based and more pragmatic reasons for opposing capital punishment provides the global abolition movement with a strong ethical foundation. Australia can advance on this basis, confident that its laws and policies are already aligned with its ethical obligations on the global stage.

Amrozi Bin Nurhasyim v Republic of Indonesia, Constitutional Review, Case no 21/PUU-VI/2008, ILDC 1151 (ID 2008)

Atkins v Virginia[2002] USSC 3164; , 536 US 304, 316-317 (2002)

Rush v Commissioner of Police [2006] FCA 12; (2006) 150 FCR 165

Sianturi v Indonesia, Constitutional Review, Nos 2-3/PUU-V/2007, ILDC 1041 (ID 2007)

Crimes Legislation Amendment (Torture Prohibition and Death Penalty Abolition) Act 2010 (Cth)

Death Penalty Abolition Act 1973 (Cth)

Extradition Act 1988 (Cth)

Alston P, Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, UN Doc A/HRC/4/20 (29 January 2007)

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 1465 UNTS 85, opened for signature 4 February 1985, entered into force 26 June 1987

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 999 UNTS 171, opened for signature 16 December 1966, entered into force 23 March 1976

Méndez J (2013) Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, UN Doc A/HRC/25/60/Add.2 (11 March 2013)

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, 2187 UNTS 90, opened for signature 17 July 1998, entered into force 1 July 2002

Safeguards Guaranteeing the Rights of Those Facing the Death Penalty, ESCOR Res 1984/50, 21st plen mtg (25 May 1984)

Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Aiming at the Abolition of the Death Penalty, GA Res 44/128, UN GAOR, UN Doc A/RES/44/128, 15 December 1989, entered into force 11 July 1991

The Rule of Law at the National and International Levels, GA Res 67/97, UN GAOR, 67th sess, 56th plen mtg, Agenda Item 83, UN Doc A/RES/67/97 (14 December 2012)

United Nations Committee Against Torture, Concluding Observations on the Combined Third to Fifth Periodic Reports of the United States of America, UN Doc CAT/C/USA/CO/3-5 (19 December 2014)

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, GA Res 61/295, UN GAOR, 61st sess, 107th plen mtg, Supp no 49, UN Doc A/RES/61/295 (13 September 2007)

United Nations Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations on Indonesia, UN Doc CCPR/C/IDN/O/1 (21 August 2013)

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, GA Res 217A (III), UN GAOR, 3rd sess, 183rd plen mtg, UN Doc A/810 (10 December 1948)

Abbott T (2015) Executions of Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran, Media release, 29 April 2015, Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Canberra <http://www.pm.gov.au/media/2015-04-29/executions-andrew-chan-and-myuran-sukumaran-0>

ABC (2015a) ‘Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran “Relieved” over Transfer Delay, Says Julie Bishop’, ABC News (online), 19 February 2015 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-02-18/bali-nine-abbott-asks-indonesia-remember-australias-past-help/6139032>

ABC (2015b) ‘Indonesian Ambassador Paul Grigson returns to Jakarta after Recall in Protest of Bali Nine Executions’, ABC News (online), 10 June 2015 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-06-10/indonesian-ambassador-returns-to-jakarta-following-withdrawal/6534176>

Abjorensen N (2015) ‘Death Penalty: Are We Really United in Our Opposition?’, The Drum

(online), 1 May 2015 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-01/abjorensen-are-we-really-united-in-our-opposition/6436942>

Amnesty International (2014a) Death Penalty: Overview, Amnesty International Australia <https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/death-penalty/>

Amnesty International (2014b) ‘2014 World Day against the Death Penalty: Protecting People with Mental and Intellectual Disabilities from the Use of the Death Penalty’ <https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/ACT51/005/2014/en/>

Amnesty International (2015) Death Sentences and Executions 2014, February 2015, 7, 11–13 <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2015/02/death-sentences-and-executions-2014/>

Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the Human Rights Law Centre, Reprieve Australia, Australians Detained Abroad, Civil Liberties Australia, the NSW Council of Civil Liberties and Uniting Justice Australia (2015), ‘Australian Government and the Death Penalty: A Way Forward’ <http://www.amnesty.org.au/resources/activist/Death_Penalty_-_A_Way_Forward.pdf>

ANTARA News (2014) ‘Indonesia in State of Emergency over Drugs: President’, ANTARA News (online), 9 December 2014 <http://www.antaranews.com/en/news/96850/indonesia-in-state-of-emergency-over-drugs-president>

Associated Press (2015) ‘Indonesian Court Rejects Serge Atlaoui’s Final Appeal against Execution’, The Guardian Australia (online), 22 June 2015 <http://www.theguardian.

com/world/2015/jun/22/indonesian-court-rejects-serge-atlaouis-final-appeal-against-execution>

Australian Coalition against Death Penalty (2004) Interview with Dr Philip Opas QC, 1 March 2004 <http://www.acadp.com/>

Australian Federal Police (2015) ‘Transcript: Commissioner Andrew Colvin, Deputy Commissioner Michael Phelan and Deputy Commissioner Leanne Close discuss Bali Nine’, 1–30 (4 May 2015) <http://www.afp.gov.au/~/media/afp/pdf/b/bali9-150504-soc-transcript.pdf>

Australian Federal Police Governance (2010) AFP National Guideline on International Police-to-police Assistance in Death Penalty Situations <http://www.afp.gov.au/~/media/afp/pdf/ips-foi-documents/ips/publication-list/afp%20national%20guideline%20on%20international%20police-to-police%20assistance%20in%20death%20penalty%20situations.pdf>

Bae S (2007) When the State No Longer Kills: International Human Rights Norms and Abolition of Capital Punishment, State University of New York Press

Butt S and Schutte S (2014) ‘Assessing Judicial Performance in Indonesia: The Court for Corruption Crimes’, Crime, Law and Social Change 62(5), 603–19

Byrnes A (2007a) ‘The Right to Life, the Death Penalty and Human Rights Law: An International and Australian Perspective’, University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series 35

Byrnes A (2007b) ‘Drug Offences, the Death Penalty and Indonesia's Human Rights Obligations in the Case of the Bali 9: Opinion Submitted to the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Indonesia 3(a)’, University of New South Wales Law Resolution Series, Paper No 44 cited in Lynch C (2009) ‘Indonesia’s Use of Capital Punishment for Drug Trafficking Crimes: Legal Obligations, Extralegal Factors and the Bali Nine Case’, Columbia Human Rights Law Review 40(2), 523–93, 535

Byron M (2000) ‘Why My Opinion Shouldn’t Count: Revenge, Retribution, and the Death Penalty Debate’, Journal of Social Philosophy 31, 307–15

Carne G (2011), ‘Abolitionist or Relativist? Australia’s Legislative and International Responses to its International Human Rights Death Penalty Abolition Obligations’, University of Western Sydney Law Review 3, 40–79

Cohen-Cole E, Derlauf S, Fagan J and Nagin D (2009) ‘Modern Uncertainty and the Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment’, American Law and Economics Review 11, 335–69

Commonwealth of Australia (2009) Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 19 November 2009, 12197 (Robert McClelland, Attorney-General).

Commonwealth of Australia (2015) Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 12 February 2015, 656 (Julie Bishop, Foreign Minister)

Connelly A (2015) ‘Sovereignty and the Sea: President Joko Widodo’s Foreign Policy Challenges’ Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 37(1), 1–28

Cornell University Law School (2011) Death Penalty Database: Saudi Arabia, 4 April 2011 <http://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org/country-search-post.cfm?country=Saudi+Arabia#f72-3>

Cornell University Law School (2012) Death Penalty Database: Afghanistan, 11 December 2012 <http://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org/country-search-post.cfm?country=Afghanistan>

Cornell University Law School (2014a) Death Penalty Database: Iran, 7 April 2014 <http://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org/country-search-post.cfm?country=Iran>

Cornell University Law School (2014b) Death Penalty Database: China, 10 April 2014 <http://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org/country-search-post.cfm?country=China#f97-3>

Cornell University Law School (2014c) Death Penalty Database: United States of America, 10 March 2014 <http://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org/country-search-post.cfm?country=United+States+of+

America>

Cornell University Law School (2016) Death Penalty Worldwide <http://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.

org/search.cfm>

de Wet E (2004) ‘The Prohibition of Torture as an International Norm of jus cogens and Its Implications for National and Customary Law’, European Journal of International Law 15, 97–121

Dicey AV (1915) Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution, 8th ed, Macmillan, 173

Doherty B (2015) ‘Death Penalty Shunned in Pacific, But Asia Re-adopts Executions — Report’, The Guardian (online), 1 April 2015 <http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/01/indonesias-renewed-use-of-death-penalty-is-part-of-wider-trend-report>

Drilling A (2013–14) ‘Capital Punishment: The Global Trend toward Abolition and Its Implications for the United States’, Ohio Northern University Law Review 40, 837–72

Duff X (2014) Noose, Five Mile Press

Fenwick S (2008) ‘Measuring Up? Indonesia’s Anti-corruption Commission and the New Corruption Agenda’ in T Lindsey (ed), Indonesia: Law and Society, 2nd ed, Federation Press, 406–29

Finlay L (2011) ‘Exporting the Death Penalty? Reconciling International Police Cooperation and the Abolition of the Death Penalty in Australia’, Sydney Law Review 33, 95–117

France Diplomatie (2015) ‘Fiji — Permanent Abolition of the Death Penalty’, Press release, 13 February 2015 <http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/fiji-islands/france-and-fiji-islands/political-relations-6849/article/fiji-permanent-abolition-of-the>

Fullilove M (2006) Capital Punishment and Australian Foreign Policy, Lowy Institute, 2006

Garkawe S (2013) ‘The Role of Abolitionist Nations in Stopping the Use of the Death Penalty in Asia: The Case of Australia’ in R Hood and S Deva (eds), Confronting Capital Punishment in Asia: Human Rights, Politics and Public Opinion, Oxford University Press, 90–104

Gaughran A (2015) ‘One Hundred Death Penalty Free Countries Within Reach after Fiji Becomes Number 99’, Amnesty International (online), 13 March 2015 <https://www.amnesty.

org/en/latest/campaigns/2015/03/one-hundred-death-penalty-free-countries-within-reach-after-fiji-becomes-number-99-1/>

General Affairs Council of the European Union (2008) EU Guidelines on the Death Penalty

Grattan M (2015) ‘Australia Withdraws its Indonesian Ambassador in Execution Response’, The Conversation, 29 April 2015 <https://theconversation.com/australia-withdraws-its-indonesian-ambassador-in-execution-response-4095>

Harrison N (2006) ‘Extradition of the “Bali Nine”: Can and Should the Risk of Capital Punishment Facing Australians be Relevant to Extradition Decisions?’, International Journal of Punishment and Sentencing 1(4), 221–39

Holmes O (2016) ‘Mary Jane Veloso: What Happened to the Woman who Escaped Execution in Indonesia?’, The Guardian (online), 28 April 2016 <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/28/

mary-jane-veloso-indonesia-execution-reprieve>

Hood R (2002) The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective, 3rd ed, Oxford University Press, 7

Hood R and Hoyle C (2009) ‘Abolishing the Death Penalty Worldwide: The Impact of a “New Dynamic”’, Crime and Justice 38(1), 1–63

Hood R and Hoyle C (2015) ‘There is No Evidence that the Death Penalty Acts as a Deterrent’,

The Conversation, 25 April 2015 <https://theconversation.com/there-is-no-evidence-that-the-death-penalty-acts-as-a-deterrent-37886>

Human Rights and Democracy Department (2011) HMG Strategy for Abolition of the Death Penalty 2010–2015, Foreign and Commonwealth Office

Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (2016) A World Without the Death Penalty: Australia’s Advocacy for the Abolition of the Death Penalty, Commonwealth of Australia

Jones B (ed) (1968) The Penalty is Death: Capital Punishment in the Twentieth Century, Sun Books

Klein N and Knapman L (2011) ‘Australians Sentenced to Death Overseas: Promoting Bilateral Dialogues to Avoid International Law Disputes’, Monash University Law Review 37(2), 89–113

Lamb K (2015) ‘Bali Nine: Indonesia Has Death Penalty Double Standard, Says Brother of Spared Maid’, The Guardian (online), 16 February 2015 <http://www.theguardian.com/world/

2015/feb/16/bali-nine-indonesia-has-death-penalty-double-standard-says-brother-of-spared-maid>

Lehrfreund S (2013) ‘The Impact and Importance of International Human Rights Standards: Asia in World Perspective’ in R Hood and S Deva (eds), Confronting Capital Punishment in Asia: Human Rights, Politics and Public Opinion, Oxford University Press, 25

Lennan J and Williams G (2012) ‘The Death Penalty in Australian Law’, Sydney Law Review 34,

659–94

Letter from Law Council of Australia to Federal Attorney-General and Minister for Home Affairs, ‘AFP Practical Guide on International Police to Police Assistance in Potential Death Penalty Situations,

29 January 2010, 2 <http://www.lawcouncil.asn.au/lawcouncil/images/LCA-PDF/docs-dated/

20100129-MinisterforHomeAffairsrenewAFPGuide.pdf>

Lindsey T (2015) ‘Indonesia’s Stance on the Death Penalty Has Become Incoherent’, The Conversation, 16 February 2015 <https://theconversation.com/indonesias-stance-on-the-death-penalty-has-become-incoherent-37619>

Lowy Institute (2015) New Lowy Institute Poll Finds that 62% of Australians Oppose the Execution of Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran, Media Release, 16 February 2015 <http://www.lowyinstitute.org/news-and-media/press-releases/new-lowy-institute-poll-finds-62-australians-oppose-execution-andrew-chan-and-myuran-sukumaran>

Lynch C (2008–2009) ‘Indonesia’s Use of Capital Punishment for Drug-Trafficking Crimes:

Legal Obligations, Extralegal Factors, and the Bali Nine Case’, Columbia Human Rights Law Review 40, 523–93

McInerney M (2015) ‘Australian Campaign to Abolish the Death Penalty’, BBC News (online), 4 May 2015 <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-32579232>

McRae D (2012) ‘A Key Domino? Indonesia’s Death Penalty Politics’, Lowy Institute for International Policy (online), March 2012 <http://www.lowyinstitute.org/files/mcrae_a_key_domino_web-1.pdf>

Maguire A (2015) ‘Hardline on Refugees Undermines Principled Opposition to Execution’,

The Conversation, 30 April 2015 <https://theconversation.com/hard-line-on-refugees-undermines-principled-opposition-to-execution-40953>

Maguire A (2016) ‘As Indonesia Conducts More Executions, Australia’s Anti-death-penalty Advocacy Still Lacking’, The Conversation, 29 July 2016 <https://theconversation.com/as-indonesia-conducts-more-executions-australias-anti-death-penalty-advocacy-is-still-lacking-63058>

Malkani B (2013) ‘The Obligation to Refrain from Assisting the Use of the Death Penalty’, International and Comparative Law Quarterly 62, 523–56

Marcus C (2015) ‘The Bali Nine Ringleaders Traded in Death by Smuggling Heroin and Now Must Face the Consequences’, The Sunday Mail (online), 18 January 2015 <http://www.couriermail.

com.au/news/opinion/opinion-the-bali-nine-ringleaders-traded-in-death-by-smuggling-heroin-and-now-must-face-the-consequences/story-fnihsr9v-1227188153470>

Margarey K and Jordan R (2010) ‘Parliament and the Protection of Human Rights’, Parliamentary Library Briefing Book, 12 October 2010 <http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_

Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook43p/humanrightsprotection>

Marr D (2010) ‘Death and the State’, The Sydney Morning Herald (online), 23 October 2010 <http://www.smh.com.au/national/death-and-the-state-20101022-16xw5.html>

Mitchell N (2003) Interview with Prime Minister John Howard (Radio 3AW, 8 August 2003)

Mukherjee SK, Walker J and Jacobsen E (1986) Crime and Punishment in the Colonies: A Statistical Profile, History Project Inc

O’Malley N (2015) ‘Julie Bishop: Ending Death Penalty Worldwide on Australia’s UN Agenda’, Sydney Morning Herald (online), 30 September 2015 <http://www.smh.com.au/world/julie-bishop-ending-death-penalty-worldwide-on-australias-un-agenda-20150930-gjxxxg.html>

Parliament of Australia (2015) Inquiry: Australia’s Advocacy for the Abolition of the Death Penalty <http://www.aph.gov.au/deathpenalty>

Plibersek T and Shorten B (2015) ‘The Execution of Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran’, Media release, 29 April 2015 <http://tanyaplibersek.com/2015/04/statement-the-execution-of-andrew-chan-and-myuran-sukumaran/>

Potas I and Walker J (1987) ‘Capital Punishment’, Trends and Issues in Criminal Justice Paper No 3, Australian Institute of Criminology, February 1987

Refugee Council of Australia (2015) 2015–16 Federal Budget in Brief <http://www.refugeecouncil.

org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/2015-16-Budget.pdf>

Reith P (2015) ‘Why No Outcry over Death Penalty in the US?’, Sydney Morning Herald (online), 18 May 2015 <http://www.smh.com.au/comment/why-no-outcry-over-death-penalty-in-the-us-20150

518-gh40v2.html>

Roberts G, Jennett G and staff (2015) ‘Bali Nine Pair Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran “Dignified” Ahead of Executions’, ABC News (online), 29 April 2015 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-04-28/bali-nine-andrew-chan-myuran-sukumaran-dignified-executions/6428222>

Rothwell D, Kaye S, Akhtarkhavari A and Davis R (2014), International Law: Cases and Materials with Australian Perspectives, 2nd ed, Cambridge University Press

Roy Morgan Research (2009), Australians Say Penalty for Murder Should be Imprisonment (64%) Rather than the Death Penalty (23%), Finding No 4411 <http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/finding-4411-201302260051>

Roy Morgan Research (2015), Australians Think Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran Should be Executed, Finding No 6044 <http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/6044-executions-andrew-chan-myuran-sukumaran-january-2015-201501270609>

Saul H (2015) ‘Bali Nine: Schizophrenic Man Rodrigo Gularte Did Not Understand He Was Going to Be Executed Until Final Moments Before His Death’, The Independent (online), 30 April 2015 <http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/bali-nine-schizophrenic-man-rodrigo-gularte-did-not-understand-he-was-going-to-be-executed-until-final-moments-before-his-death-10214446.html>

Sayed-Khaiyum A (2015) Republic of Fiji, Parliamentary Debates, Parliament of Fiji, 9 February 2015, 680

SBS (2015) ‘Bali Nine Bribe Probe Takes Evidence’, SBS Online, 11 May 2015 <http://www.sbs.com.

au/news/article/2015/05/11/bali-nine-bribe-probe-takes-evidence>