Current Issues in Criminal Justice

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Current Issues in Criminal Justice |

|

Fighting Like a Girl ... or a Boy?

An Analysis of Videos of Violence between Young Girls Posted on

Online Fight Websites

Ashleigh Larkin[*] and Angela Dwyer[†]

Abstract

How young women engage in physical violence with other young women is an issue that raises specific concerns in both criminological literature and theories. Current theoretical explanations construct young women’s violence in one of two ways: young women are not physically violent at all, and adhere to an accepted performance of hegemonic femininity; or young women reject accepted performances of hegemonic femininity in favour of a masculine gendered performance to engage in violence successfully. This article draws on qualitative and quantitative data obtained from a structured observation and thematic analysis of 60 online videos featuring young women’s violent altercations. It argues that, contrary to this dichotomous construction, there appears to be a third way young women are performing violence, underpinned by masculine characteristics of aggression but upholding a hegemonic feminine gender performance. In making this argument, this article demonstrates that a more complex exploration and conceptualisation of young women’s violence, away from gendered constructs, is required for greater understanding of the issue.

Keywords: young girls – young women – violence – gender – fight sites – videos – theories – masculinity – femininity

Young women engaging in physically violent behaviour against other young women have always intrigued the media and the general public. While a universal definition of ‘physical violence’ has yet to be agreed upon, this article broadly defines it as ‘an intentionally harmful interpersonal physical act’ (Batchelor, Burman and Brown 2001:127). Currently, the issue of young women using social media platforms to display their violent behaviours is capturing the attention of criminological inquiry and the general public. This is because violence is a behaviour synonymous with masculinity, which has resulted in an expectation that young women should refrain from engaging in violent behaviours (Connell 1999; Gilbert 2002). The introduction of social media and other communication technologies has provided a global platform where acts of violence proliferate, with young women increasingly using social media to demonstrate their own physical violence (Carrington and Pereira 2009; Carrington 2013). This is well evidenced by the more than 600 million videos available online featuring incidences of violence between young women (Carrington and Pereira 2009; Carrington 2013). Resultant increased public attention is illustrated through media discussions regarding how young women use social media to demonstrate their violence. News media outlets publish articles with titles such as ‘Girl-on-girl Violence and Attacks Are an Issue’ (News Mail Bundaberg 2014); and ‘Five Teenage Girls Charged over Violent Brawl at Western Australian School’ (Spriggs and De Poloni 2014). Online videos featuring violence between young women vastly outnumber those featuring young men’s altercations, and appear to be increasing exponentially (Carrington and Pereira 2009; Carrington 2013). Despite the evidence that young women are actively choosing violent behaviours, explanations for young women’s violence continue to revolve around masculine gendered constructions. Existing criminological theories have yet to conceptualise violence in a way that allows young women to behave in a physically violent way without first requiring them to be constructed as masculine (Carrington 2006; Carrington 2013; Jackson 2006; Muncer et al 2001).

This article reports on empirical research examining videos of young women’s physical violence published via social media. The analysis demonstrates that, in contrast to masculine constructions of violence, young physically violent women appear to be opting into an alternative performance of gender underpinned by elements of both hegemonic masculinity and femininity. This article argues the need to move beyond masculine constructions of violence to better understand the complexity of young women’s altercations. First, the article demonstrates how current literature and theoretical approaches continue to conceptualise violence as a masculine construction. It then outlines the methodological approach of the research project and analyses the qualitative and quantitative data collected to demonstrate the disconnect between what young women’s violence should look like (according to existing literature and theories) and what young women’s violence actually looks like. Finally, it proposes that moving beyond masculine constructions of violence, and examining violence beyond the masculine–feminine dichotomy, will lead to a better understanding of and response to young women’s violence.

Constructions of young women’s violence in both criminological theories and literature are underpinned by the notion of hegemonic masculinity, defined as ‘the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees ... the dominant position of men and the subordinate position of women’ (Connell 2005:77). It is a socially fluid concept that dictates the scope of accepted masculine gendered performance to which all men must aspire in order to demonstrate their masculine identity (Salter and Tomsen 2012; Connell 2008; Messerschmidt 2008; Tomsen 2008). In its current dominant construction, hegemonic masculinity requires men to be dominant, assertive and aggressive (Connell 2008; Connell 1999; Connell and Messerschmidt 2005; Carrington, McIntosh and Scott 2010). This construction allows men to use violence as a way of demonstrating their masculinity, especially if they lack the social status or economic resources to otherwise demonstrate it (Salter and Tomsen 2012; Connell 2008; Messerschmidt 2008; Tomsen 2008). This has resulted in young men’s participation in violence being largely unquestioned as it is seen as an inevitable part of being masculine and plays a key role in the construction of a masculine gender identity (Salter and Tomsen 2012:309; Tomsen 2005:283; Connell 2008:90; Messerschmitt 2008:198; Carrington, McIntosh and Scott 2010).

On the other hand, the current construct of hegemonic femininity states that young women should be quiet, passive and demure (Wesley 2006; Jones 2008; Jones and Flores 2012). Adhering to accepted performances of hegemonic femininity provides no scope for young women to engage in violent or aggressive behaviours. This has resulted in a social expectation that women abstain from enacting violence, which contributes to both traditional and feminist criminological theories continuing to conceptualise violence using a masculine construction (Cunneen and White 2002; Irwin and Chesney-Lind 2008; Wesley 2006; Boots and Wareham 2012).

Traditional criminological theories were postulated to apply to the offending behaviours of men because men commit the majority of criminal offences, especially those involving physical violence (Carrington and Pereira 2009). The fact that men offend at much higher rates than young women meant women’s engagement in crime and violence was not considered significant enough to warrant consideration. As a result, these traditional theories provided limited consideration of young women’s offending behaviours (Chesney-Lind 1997; Chesney-Lind and Shelden 1992). Where young women’s offending was considered, it was assumed that theories used to explain young men’s criminality were equally applicable to young women.

Feminist criminologies aimed to move beyond the approach taken by traditional theorists, but they continue to construct violence around masculine gendered behaviours and provide limited theoretical consideration of young women as perpetrators of violence (Chesney-Lind 1997; Sharpe 2012). How feminist criminologies continue to examine violence as a gendered construct is best illustrated by examining four theories: the sexualisation thesis, the sisters in crime thesis, structural opportunity theories and the ladette thesis. All four aim to consider young women’s increasing crime and violence, yet each continues to examine violence as a predominantly masculine behaviour (Carrington 2006, 1993). Feminist criminologies have yet to conceptualise young women’s violence away from the gender dichotomy. For example, the sexualisation thesis shows how young women were routinely processed through welfare systems for offences such as sexual promiscuity, running away or being in moral danger. These offences were rarely — if ever — applied to young men’s behaviour and led to young women being institutionalised for failing to adhere to accepted feminine gendered behaviours (Carrington 1993, 1996).

The sisters in crime thesis, structural opportunity theories and the ladette thesis all demonstrate how young women’s violence continues to be conceptualised as a masculine gendered behaviour, and how it is explained using the masculinity of femininity. The first two were written around the time of women’s liberation and argue that as women obtained social and structural opportunities equal to men, their engagement in crime and violence would also become more equal due to the masculinisation of feminine behaviour (Carrington and Pereira 2009; Carrington 2006). The ladette thesis takes this argument one step further and proposes that young women now actively reject traditional feminine behaviours in favour of masculine ones when being violent (Sharpe 2012; Jackson 2006). The continued construction of physical violence as a masculine gendered behaviour, and the failure of feminist criminologies to conceptualise beyond this, has impacted how young women’s violence is explained in current literature.

In line with considerations offered by criminological theories, the literature in this area provides two dominant arguments about young women’s violence. The first is the masculinity of femininity argument, which suggests some young women aim to be perceived as token males and take steps to completely disguise their femininity when being physically violent, as this allows them to enact violence underpinned by masculine characteristics of aggression (Miller 2001; Mullins and Miller 2008). Doing so requires young women to completely reject all elements of their femininity in favour of a masculine gender performance — to such an extent they are perceived as token males (Miller 2001; Jones 2009). This provides young women a way to perform violence in an acceptable way, especially in the context of male-dominant youth gangs, or street violence (Miller 2002; Mullins and Miller 2008; Jones 2008; Batchelor 2011).

By contrast, the second argument suggests that young women can ‘do gender differently’ when engaging in violence (Messerschmidt 2008; Miller 2002; Mullins and Miller 2008). This literature looks at how young women can maintain their femininity while behaving in ways that are traditionally defined as masculine, and begins to move beyond constructing violence as a purely masculine behaviour (Miller 2002; Batchelor 2011; Messerschmidt and Tomsen 2011). There are two elements to this argument. Some authors indicate young women gender-cross by adhering to a masculine gender performance when being physically violent, yet embrace a feminine performance of gender in other areas of their lives (Miller 2002; Batchelor 2011; Miller and White 2004). Other authors indicate that young women do gender differently and perform violence in a feminine way, and distinguish their acts of violence from masculine acts of aggression (Jones 2008; Wesley 2006; Cameron and Taggar 2008). According to this viewpoint, young women do not see violence as something that women do; rather, it is something young women do out of necessity. To date, studies of young women’s violence have emphasised the key role that violence plays in the lives of young men in establishing their masculine identity (Jones 2008; Wesley 2006; Cameron and Taggar 2008). This construction allows young women to distinguish their acts of violence from violence committed by young men, and to engage in violence in a feminine way. However successful performances of violence continue to revolve around accepted conceptions of masculinity and masculine characteristics of aggression (Mullins and Miller 2008; Miller 2001).

Intertwining accepted performances of violence with masculinity has resulted in the literature providing distinct definitions of what it means to fight like a girl and fight like a boy. ‘Fighting like a girl’ is defined as using relational aggression or verbal abuse, scratching, hair-pulling, pinching, biting, or spitting (Ness 2004; Talbott et al 2010). In contrast, ‘fighting like a boy’ means to punch, kick, knee, and wrestle opponents (Talbott et al 2010:208; Daly 2008:117; Mullins and Miller 2008:45). However, there are numerous other factors that could underpin young women’s violence that move well beyond the definition, such as humiliation, provocation, revenge, edgework (that is, voluntary risk taking) or the thrill of it (Katz 1988; Katz 1972; Lyng 1990; Tomsen and Mason 2001). These definitions of what it means to fight like a girl or fight like a boy emerge from literature that demonstrates the negative connotations of the characteristics associated with fighting like a girl. The young women studied who enacted violence underpinned by these characteristics were portrayed as weak or as poor fighters (Ryder 2010:132; Daly 2008:118; Jones 2008:72; Ness 2004:42; Chesney-Lind, Morash and Stevens 2008).

As a result, research examining young women’s participation in violence assumes that this violence will have distinctive characteristics depending on which performance of violence the young women adhere to. For example, if young women perform violence in a masculine way, and aim to be considered ‘one of the boys’ when doing so, it is argued that young women’s violence should have the same key characteristics as young men’s violence (Miller 2001). This requires young women to practise masculine fighting techniques and to avoid feminine characteristics of aggression (Miller 2001). This construction assumes young women will enact violence in a brutal and masculine way, and that there should be minimal differences between young women’s and young men’s performances of violence (Miller 2001). Thus, young women must adopt a masculine gender performance when engaging in physical violence underpinned by masculine characteristics of aggression (Miller 2001).

Alternatively, if young women perform violence in a feminine way, existing studies of young men’s and women’s violence assume such violence will be qualitatively different. This performance of violence requires young women to distinguish their acts of violence from young men’s physical altercations and favour more feminine fighting techniques (Ness 2004; Talbott et al 2010). The young women who engage in violence underpinned by these feminine characteristics of aggression are required to adhere to a traditional feminine performance of gender (Ness 2004; Jones 2008; Jones 2009). However, most studies of young women’s violence found young women aimed to avoid these feminine characteristics of aggression. This again highlights how accepted performances of violence are intertwined with masculine characteristics of aggression, which reinforces masculine constructions of violence and confirms the incompatibility of successful performances of violence and femininity. More importantly, it shows the limited knowledge we have of what young women’s violence actually looks like and how young women perform the violence.

To document what young women’s violence looks like, we undertook a structured observation and thematic analysis of 60 videos featuring physical altercations between young women aged 14–25 years. These fight videos were uploaded onto five social media platforms or fight sites between January 2012 and July 2013. For the purposes of this research, social media platforms or fights sites were defined as web-based applications that produce user-generated content, shared by communities based on mutual interest (Bluett-Boyd et al 2013:88). Both the fight sites and fight videos were selected using a purposive sampling method (Champion 2006; Hagen 2010). The fight sites were selected on the basis that they allowed online viewers to post comments to specific fight videos and they included more than ten fight videos uploaded during the selected timeframe. The specific sites and timeframe were chosen to ensure the most up-to-date fight sites and fight videos formed part of the sample (Champion 2006; Hagen 2010).

To draw conclusions about how accepted performances of gender impact young women’s engagement in physical violence, the fight videos were selected according to the presence of key words in the titles or comments such as: chicks; chick-fight; street fight; brutal; extreme fight; and insane girl fight. For example, one title read, ‘Mexican chicks fight it out street fighting’. The comments were made by fight participants or the audience watching the physical altercation in the video, or were posted by online viewers. This sampling method was used due to the large number of videos featuring physical violence between women available online; it ensured that analysed fight videos made some reference to how gender was being performed by young women enacting violence, in turn ensuring the data collected could address the research questions (Champion 2006; Hagen 2010). It was assumed young women who presented as feminine were identified as feminine, when they may not identify in this way. More research is needed to determine how these young women describe their gender identity and how they describe their gender performance when engaging in violence.

The research methodology involved conducting a structured observation that coded and analysed each fight video according to predetermined characteristics using a coding schedule. This involved collecting both qualitative and quantitative variables relating to each analysed fight video (Martinko 1990; Martinko and Gardner 1985; Given 2008). The quantitative characteristics of fight videos coded included: age and ethnicity of fight participants (where this information was available); the number and ratio of fight participants; what fight participants were wearing, including whether they were wearing makeup or jewellery; and where the fight took place. The qualitative information collected included: verbal comments made by fight participants or audience to the altercation; detailed information regarding events that led to the altercation; and detailed descriptions of what the physical altercation looked like. These coded characteristics, combined with comments posted to fight videos by online viewers, were analysed using a thematic analysis according to the presence of gendered themes in the data. The central themes present across all analysed fight videos were:

• the need for fight participants to employ normative feminine performances of gender;

• the masculine nature of the physical altercations;

• characteristics of a good fight;

• physical violence as an alternative performance of femininity; and

• racism and eroticisation of the fight participants.

This process analysed 60 videos, each of which depicted physical altercations between young women. It allowed detailed conclusions to be drawn about: what young women’s physical violence looks like; how young women in fight videos performed gender; and how they used masculine violence techniques in fights uploaded to social media. Additionally, there were a number of general characteristics underpinning each analysed video. First, of the 60 fight videos, only two depicted physical altercations that had been staged for the purposes of recording and uploading footage of them to social media. However, in 65 per cent of analysed videos, the physical altercations appeared to be organised, meaning that fight participants and the audience had gathered at a location for the purpose of watching young women fight. This was evidenced in the research sample in a number of ways. Some fight videos commenced with footage of fight participants facing one another surrounded by a large audience of spectators, where one spectator would indicate when the fighting could commence. Alternatively, audience members would make comments like ‘It’s going down!’ or ‘I can’t believe they are going to be fighting’, which indicated that the physical altercation was not spontaneous or opportunistic. Even more fight videos may have been organised in this way as in 13 per cent of the altercations fighting had commenced prior to video recording so how they were organised is unknowable. As a result, this research data cannot firmly establish whether most physical altercations were staged for recording and uploading footage to social media. The two fight videos that were staged were classified in this way because footage involved no physical contact between fight participants. In these videos, participants used makeup and made sound effects in an attempt to make altercations look authentic. How participants perform violence in staged altercations may be different to how it is performed in non-staged altercations. More research is needed to elaborate these dynamics. Further, 88 per cent of altercations occurred in a public place, such as a schoolyard, park or residential street, which contributed to most fight videos having large audiences of spectators.

In each analysed fight video, young women performed violence in a particular way. The key characteristics of that physical violence demonstrated how the young women were not adhering to masculine constructions of violence. Rather, young women in the sampled videos appeared to be balancing masculine characteristics of aggression with some elements of hegemonic femininity. The young women used physical violence as a problem-solving mechanism to deal with interpersonal peer group conflict — which is a key feature of young men’s violence (Salter and Tomsen 2012; Tomsen and Mason 2001; Tomsen 2005). Hegemonic femininity contends that young women should use techniques such as relational aggression to resolve peer group conflict (Henriksen and Miller 2012). In line with this, the vast majority of the analysed altercations appeared to be caused by conflict between two groups of young women. While there is some research exploring the normalisation of young women’s violence, violence itself has yet to be conceptualised in a way that allows young women to use violence to resolve peer group conflict and to engage in violence without breaching feminine gender norms (Arif 2015).

How young women in fight videos blur the gender dichotomy and employ elements of both hegemonic masculinity and femininity was most clearly illustrated by the clothes they wore when engaging in violence. While most wore jeans, sneakers and singlet tops, these clothes were distinctly feminine. However, all fight participants distanced themselves from a hyper-feminine gender performance, with only 30 per cent wearing visible makeup, and 60 per cent not wearing jewellery. Furthermore, while no young women wore high heels, 21 fought barefoot, which indicates they did not want to fight in the shoes they were wearing. Finally, a number of young women were observed removing jewellery and other accessories prior to commencing fighting. This could mean that a higher percentage of fight participants were wearing makeup or jewellery prior to the altercation but their removal was not shown in the fight video. However, many of the altercations took place at school, which may have influenced the number of young women not wearing makeup, high heels or jewellery on the basis that they would breach school policy.

Young women removing their shoes and jewellery before fighting suggests a number of issues about how they balance femininity with physical violence. First, they might have removed their shoes simply because the shoes they were wearing were not practical for fighting — they may have been wearing feminine footwear prior to the fight, as sandals or high-heels would be more difficult to fight in, as opposed to gender-neutral footwear like sneakers, which the majority who had footwear wore. Second, not wearing jewellery, or taking it off prior to the fight commencing, could indicate that any jewellery the young women were wearing prior to the altercation was not practical to wear during a fight. Alternatively, the young women may have removed their jewellery because using items such as rings as weapons during fights is actively discouraged (Miller 2001; Jones 2009, 2008), as evidenced in the analysed fight videos where the audience or other fight participants demanded that young women wearing jewellery take it off before the fight, saying, for example, ‘She is not hitting me wearing that ring.’

Most importantly, however, the fact that young women distanced themselves from these hyper-feminine gendered behaviours when engaging in violence demonstrates how existing theoretical frameworks offer inadequate explanations for young women’s violence. Existing frameworks assume that young women who perform violence actively avoid traditional feminine gendered behaviours in favour of masculine gendered norms in all facets of their lives, not just when they are being violent. In actuality, young women in the analysed fight videos appeared to be adhering to a feminine performance of gender overall, by removing shoes and jewellery for practical purposes, and by placing handbags, purses and other feminine clothing and accessories to one side so they would not interfere with the physical altercation.

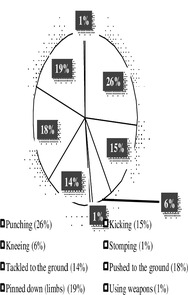

In all the analysed fight videos, there appears to be an expectation by the audience and online viewers that young women continue to uphold some elements of hegemonic femininity while participating in violence underpinned by masculine characteristics of aggression. Those young women who engaged in a less feminine gendered performance were labelled as ‘manly’ or as a ‘tomboy’. However, this expectation was most succinctly expressed in one comment posted by an online viewer: ‘Word of advice while fighting: look like a lady, fight like a man.’ How young women adhered to this expectation was evident in their fighting techniques. The majority utilised masculine characteristics of aggression, as most feminine fighting techniques were actively discouraged and avoided (Talbott et al 2010:208; Daly 2008:117; Mullins and Miller 2008:45). In fact, it appeared to be an unspoken rule underpinning all analysed altercations. Engaging in some feminine characteristics of aggression, such as biting or scratching, was enough to bring an altercation to an end. In one video, where one fight participant bit the other, a young woman watching the altercation pulled the participants apart and yelled, ‘You bit her? You serious, we bite now? That’s nasty get home!’ Other fight videos included less extreme examples, where young women would simply not engage in feminine characteristics of aggression at all or, if they did, for example, pull each other’s hair, it would attract negative comments from other fight participants, audience and online viewers. This avoidance and discouragement of young women using feminine fighting techniques was coupled with a presumption that fight participants would employ masculine characteristics of aggression, most commonly punching, kicking, kneeing, tackling an opponent to the ground, pushing an opponent to the ground, and pinning an opponent’s limbs down (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Masculine characteristics of aggression displayed by fight participants

(by percentage of participants)

In all analysed fight videos, young women were encouraged by both the audience to the altercation and online viewers to engage in brutal and masculine fighting techniques, and fight participants appeared to respond to this encouragement. The audience would yell things like ‘Hit her!’; ‘Beat her ass!’; ‘Get her to the ground!’ This encouragement was reinforced by online viewers posting comments like: ‘That girl know[s] how to fight’; ‘Damn ... She destroyed her face’; ‘Why are these females so strong now ... they hit like dudes now’. Alternatively, where the physical altercation was not deemed masculine enough, or young women were not performing masculine characteristics of aggression effectively, online viewers would comment: ‘[T]hat ... was weak none of them did no damage ... where the blood at?’; ‘That girl in orange shorts punches like a disabled person ... fists all bent and shit!! She can’t fight for shit!!’; ‘Really, no wonder why girls have bad reps, because these girls don’t know how to fight’; and ‘lol [laugh out loud]. Those chicks can’t even punch’. These comments clearly illustrate the expectations of both audience and online viewers that female fight participants engage in violence using brutal and masculine fighting techniques.

This expectation was made explicit in comments made in one particular fight video involving one young woman utilising a very masculine fighting technique and another whose fighting style was very feminine. The fight took place at a beach in front of a small audience (also of only young women). This altercation appeared to be caused by a conflict between two young women from the same peer group, with physical violence being used as a problem-solving technique. Both young women were wearing short shorts and bikini tops. The young woman with a feminine fighting style was described as having ‘girly punches’, while her opponent ‘rumbles like a cage fighter’ because, during the altercation, the young woman using masculine fighting techniques very quickly overpowered and dominated her opponent and repeatedly punched her in the head. Her opponent, on the other hand, was unable to fight back and resorted to hitting and hair-pulling. While the footage did not provide insight into about the cause of the altercation, young women in the audience allowed the fight to continue until it became obvious that the young woman with the masculine fighting style was not going to be defeated.

Other analysed fight videos followed a similar theme, where one fight participant employed brutal and masculine fighting techniques, easily beating her opponent whose fighting technique was more feminine. In these altercations, both audience and online viewers provided encouragement to young women using masculine fighting techniques, while dismissing young women using more feminine fighting styles as weak. In the videos where this occurred the online viewers made comments such as: ‘[I]t’s not the other girl’s fault that she can’t fight’; ‘[A]t least she tried #failed’; and ‘[T]hat girl in the shorts slammed the crap out of her’. In a number of videos, where fighters focused on pulling each other’s hair to prevent an opponent from effectively participating in the fight, audience members shouted: ‘[A]lright guys, no dirty, just let go of the hair right now!’ Alternatively, where only one fight participant utilised feminine characteristics of aggression, the other fight participant said: ‘[D]on’t pull my hair bitch, hit me in the face!’ Online viewers of the videos supported the negative comments made by audience members watching the altercation, posting negative comments to videos where young women were not engaging in expected characteristics of aggression, such as: ‘Omg [oh my god] worst fighting ever like hair pulling doesn’t make you a fighter’; ‘Sorry to say but they don’t know how to fight! All they do is pull hair lame’; ‘Stupid hoes always grabbing hair, none of you bitches can fight’; ‘[T]he first thing the girl in the blue did was grab her hair lol [laugh out loud] all in all this fight was lame’.

Nonetheless, most young women utilised some form of feminine fighting techniques, especially hair-pulling. Ninety-one percent of the analysed fight videos showed participants using both masculine and feminine fighting techniques. Feminine fighting techniques most commonly employed by fight participants were hair-pulling, hitting and pushing (see Figure 2).

[*] PhD Candidate and Sessional Academic, School of Justice, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology, 2 George Street, Brisbane Qld 4001 Australia. Email: aj.larkin@qut.edu.au.

[†] Associate Professor, Police Studies and Emergency Management, School of Social Science, University of Tasmania, Churchill Avenue, Sandy Bay Tas 7005 Australia. Email: angela.dwyer@utas.edu.au.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/CICrimJust/2016/2.html