Current Issues in Criminal Justice

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Current Issues in Criminal Justice |

|

“Rack ‘em, Pack ‘em and Stack ‘em”: Decarceration in an Age of

Zero Tolerance

Don Weatherburn[*]

Abstract

This article traces the recent history of prison population growth in Australia, discusses its causes, costs and benefits, and suggests ways in which the growth in Australian imprisonment rates may be contained or reversed without threat to public safety. Several options are discussed. They include abolishing short sentences, restoring discretion to the courts to set the relationship between the aggregate sentence and the non-parole period, giving Parole Boards greater discretion to deal with breaches of parole, reform of community corrections, and bail reform.

Keywords: prison – crime – sentencing – parole – public safety –

cost-benefit – Australia

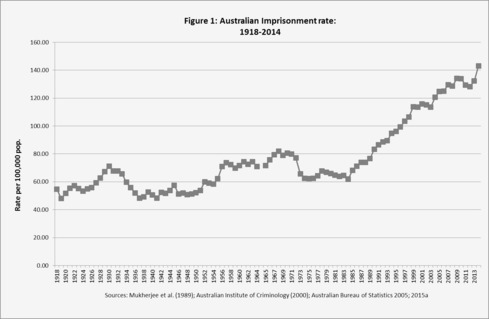

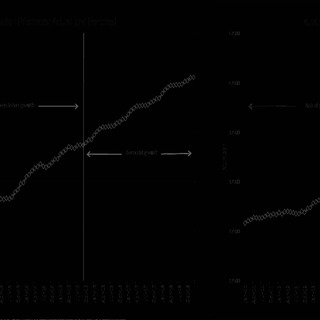

In the 66 years between 1918 and 1984, the Australian imprisonment rate rose by just 13 per cent (see Figure 1). In the 29 years that followed, it more than doubled. No state or territory escaped the prison boom. Tasmania (the state with the smallest imprisonment rate) showed the smallest increase, but even in that state the imprisonment rate rose by 58.2 per cent between 1982 and 2015. Over the same period, the imprisonment rates of Western Australia (‘WA’), Queensland and New South Wales (‘NSW’) rose by 78.7 per cent, 87.4 per cent and 90.9 per cent, respectively. The imprisonment rates of Victoria, South Australia and the Northern Territory more than doubled (Australian Institute of Criminology 1983; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2015b).

The increase has been particularly marked in the case of Indigenous Australians and women. The Indigenous imprisonment is now more than 45 per cent higher than it was at the time of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (Australian Institute of Criminology 1995; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2015b). This is despite the fact that all states and territories agreed (in response to the Royal Commission) to try and reduce the rate of Indigenous imprisonment. The increase in the rate of female imprisonment, though much less often remarked upon, has been even more rapid. In 1982, the female imprisonment rate stood at 6.9 per 100 000 of population (Australian Institute of Criminology 1983). By 2015, it had reached 30.8 per 100 000 of population (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2015b),

a 4.5-fold increase in the rate of imprisonment.

Australia now has more than 37 000 people behind bars (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2015a). Our imprisonment rate exceeds that of Canada, the United Kingdom (‘UK’) and most of Europe (Institute for Criminal Policy Research 2016). If the imprisonment rate in Australia continues to grow at the rate it has over the last five years, in three years we will have more than 43 000 people in prison and be spending more than A$3.5 billion a year keeping them there (see Appendix). It costs about A$377 000 per bed to build a new prison in a green field site, so the capital cost of accommodating an additional (43 000 – 36 000 =) 7000 prisoners will exceed A$2.6 billion.

This article reflects on how we got to this point, what costs and benefits we have accrued along the way and whether it is possible to reduce the Australian prison population without jeopardising public safety. The first section examines the growth in imprisonment between the mid-1970s and 2000, when rising crime rates contributed significantly to the growth in imprisonment rates. The second discusses the growth between 2001 and 2015, a period during which most of the growth was policy driven. The third section lays out the benefits and costs of the prison boom. In the final section, options for reducing the prison population without suffering an increase in crime are proposed.

The period between 1970 and 1985 was a turbulent one for Australia’s prison systems. As O’Toole (2006:93) states: ‘The process of steady reform that had been politically palatable across the country for decades was suddenly questioned. It was as if the corrections system had finally been exposed as being out of step with the changing values and culture of the wider society.’

The rising discontent with prisons reflected the growing discontent with most forms of institutional authority during the 1960s and 1970s, but it was also fuelled by changing views about the role of prison (Chan 1992) and unrest within the prison system itself (Brown 2005). The result was that, for a relatively brief period, the climate of opinion toward offenders took a rather liberal turn.

Sentencing law and practice at the time reflected this relatively benign attitude toward offenders. In contrast to the present situation where ‘life’ means imprisonment for life, most offenders given life sentences were eventually released, usually after a period of between 11 and 14 years (Freiberg and Biles 1975:51–8). Prison was used much more sparingly than it is now; for example, in 1980, 29 per cent of those convicted of break, enter and steal were sentenced to a term of imprisonment. In 2015, 50 per cent of the same group received a sentence of imprisonment. Formerly, prisoners in all states and territories could still earn reductions on their sentences through good behaviour. There was a general presumption in favour of bail for all but the most serious charges. Indeed, as late as 1983, the NSW Parole Board was required to release an offender on parole, unless it had good reason to believe that he or she could not adapt to normal lawful community life (Probation and Parole Act 1983 (NSW), s 26(1)). This was the high watermark of public support for rehabilitation. Behind the scenes, though, forces were at work that would eventually replace this liberal perspective with a much harsher constellation of attitudes toward offenders and offending.

Between 1973–74 and 1988–89, the per capita rate of: recorded assault rose 381 per cent; robbery rose 121 per cent; break and enter rose 122 per cent; motor vehicle theft rose 106 per cent; fraud rose 220 per cent; stealing rose 80 per cent (Australian Institute of Criminology 1990). By 1983, nearly one in ten Australian households had been victims of some form of household property crime in the preceding 12 months (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1986). The first international crime victim survey results in 1990 showed Australia had higher property crime rates than any other country surveyed (van Dijk, Mayhew and Killias 1990). Even so, rates of assault, robbery, break and enter, and theft continued to rise to the end of the decade (Mukherjee, Carcach and Higgens 1997; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2001b).

Over the period during which assault, robbery, burglary and theft offences were rising there were, not surprisingly, large increases in the number of offenders in prison for assault, robbery, burglary and theft offences (Australian Institute of Criminology 1986, 1999). The growth in crime, however, was not the only cause of rising imprisonment rates.

As in the UK

(Garland 2001), the growth in crime was accompanied by rising public concern about crime.

Between 1990 and 2000, for example, the proportion of NSW residents expressing concern about crime in their neighbourhood grew from 30.6 per cent to 33.0 per cent for home burglary; 18.9 to 21.8 per cent for car theft; 17.1 per cent to 19.5 per cent for ‘louts/youth gangs’; 10.3 per cent to 17.3 per cent for illegal drugs; and 17.4 per cent to 24.2 per cent for vandalism/graffiti (Australian Bureau of Statistics 1991, 2000).

Politicians and the media were quick to exploit rising public concern about crime and falling public confidence in offender rehabilitation (see, for example, Cunneen, Baldry, Brown, Schwartz, Steel & Brown 2013). The result was a growth in public support (and political commitment to) tougher law and order policies. The process began first in the United States, where crime rates started rising well before those in Australia. As American legislatures began to rebuild their sentencing systems around punishment and incapacitation, however, Australian legislatures began to follow suit. Over the next 20 years (Freiberg and Ross 1999; Warner 2002; Freiberg 2005; Anderson 2012); we saw:

• the introduction of ‘three strikes’ sentencing legislation in the Northern Territory (NT) and WA;

• the creation of mandatory minimum penalties (in NSW, the NT and WA);

• consecutive life sentences;

• increased maximum penalties;

• the abolition of prison remissions (in all states except Tasmania);

• the requirement that non-parole periods be a fixed proportion of the total sentence (in NSW, WA and Tasmania);

• the requirement in NSW that offenders given life sentences spend the rest of their lives in gaol; and the

• repeated toughening of bail laws especially in NSW.

Such was the mood of antipathy toward rehabilitation in the 1980s, even the Australian Law Reform Commission — a body not normally thought of as a bastion of conservative opinion — called for the abolition of parole (Australian Law Reform Commission 1980). And so the 1990s progressed to their close, with imprisonment rates pushed ever higher by a spiral of rising crime rates and tougher law and order policies.

In 2001, the major categories of theft and robbery started to fall. Figure 3 shows the national trends in break and enter; vehicle theft; robbery and other theft offences, for the period 2000-2014. The motor vehicle theft and robbery rates have been scaled up to make it easier to see the trends. Over the last 15 years (see Australian Institute of Criminology 1990; Australian Institute of Criminology 1997; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010):

• the recorded robbery rate has fallen 66 per cent;

• the recorded burglary rate has fallen by 67 per cent;

• the recorded motor vehicle theft rate has fallen by 71 per cent; and

•

the recorded rate of ‘other theft’ has fallen by 43 per cent.

There is no national set of recorded assault data from 2000 onwards, but the evidence from victim survey data suggests that assaults remained stable or fell slightly from 2001 to 2010. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016a), in 2002, 4.7 per cent of Australians aged 15 years and over were victims of assault in the preceding 12 months. The prevalence of assault has been lower in every year since 2008–09 (when annual Australian crime victim surveys began). Last year the estimated prevalence of assault was 2.1 per cent. National recorded crime data suggest that the incidence of sexual assault has been comparatively stable since 2001 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2010, 2015b). In short, from 2001 onwards, most major categories of crime either fell or remained stable. The only categories of serious reported crime known to have increased since 2001 are sexual assault, drug trafficking and fraud.

The decline in crime might have been expected to eventually result in a stabilisation or reduction in imprisonment rates and a decline in the salience of law and order as a policy issue. This did not happen. Crime might have been falling, but large sections of the general public remained convinced that it was still rising (Halstead 2015). As always, sections of the media remained willing to exploit public concern about crime. The tougher laws kept coming and imprisonment rates kept rising. Figure 4 shows the net percentage change in imprisonment rates since 1999, broken down by jurisdiction. Since crime rates started falling in 2000, the Australian imprisonment rate has risen by nearly 30 per cent. Only Queensland managed to keep its imprisonment rate comparatively stable for most of the decade.

The top five offence categories in terms of prison population growth since 1999 have been acts intended to cause injury, illicit drug offences, sexual assault and related offences, offences against justice procedures and unlawful entry with intent/break and enter (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2015c). Collectively these offences accounted for more than 80 per cent of the growth in prisoner numbers between 2001 and 2015. Yet most of these offences have remained stable or fallen. The only offence in the top five contributors to imprisonment rate growth, which has unquestionably increased is that of illicit drug offences (Australian Crime Commission 2015; Health Stats NSW 2016). This category accounts for only 13 per cent of the prison population growth in Australia since 2001 (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2015c).

In contrast to the situation between 1985 and 2000, most of the growth in Australian imprisonment rates since 2001 has been the result of factors endogenous to the criminal justice system (for example, changes in policing policy, changes in court bail and sentencing decisions) rather than by rising crime (see, for example, Freeman 2015). Given that much of the growth in imprisonment rates between 1985 and the present has been driven by political, judicial and police reactions to crime (rather than crime itself), we might expect state and territory governments to be pleased about the growth. Some declared they were. Former NSW State Premier, Bob Carr remarked that the growth in the NSW imprisonment rate should ‘provide comfort to law-abiding citizens’ (Noonan 2005). Former South Australian Premier Kevin Foley went even further, declaring that he would ‘Rack ‘em, pack ‘em and stack ‘em if that’s what it takes to keep our streets safe’ (ABC 2008).

Despite appearances, however, concerns were almost certainly growing about the rising rate of imprisonment. Total Australian expenditure on corrective services in 1982–83 was around about A$450 million per annum. By 1994–95 it had almost doubled in real terms, to A$883 million per annum (Productivity Commission 1995). Policy makers started introducing alternatives to custody. The first wave of alternatives included periodic detention, community service orders and suspended sentences. By the end of the 1980s, all states and territories had some form of community service order (Chan and Zdenkowski 1986a, 1986b) and, by the end of the 1990s, all had some form of suspended sentence (Victorian Sentencing Council 2006).

These options, it turned out, had little effect on the rate of imprisonment. Parliament might have intended them to be used as alternatives to prison, but courts for the most part preferred to use them as alternatives to other non-custodial sanctions, such as fines and bonds (Chan and Zdenkowski 1986a, 1986b; McInnes and Jones 2010; Menendez and Weatherburn 2014). From 2000 onwards, a second wave of alternatives to custody began to appear, most of which placed more emphasis on reducing the risk of further offending. Examples of this wave include restorative justice programs like Circle Sentencing (Marchetti and Daly 2004) and Forum sentencing (Jones 2009), as well as drug treatment programs like CREDIT (Donnelly, Trimboli and Poynton 2013), Drug Courts (Lind et al 2002) and MERIT (Lulham 2009).

There is no evidence that this second wave of alternatives to custody had any more effect on inmate populations than the first wave, and there is little reason to believe they could have had any effect. To begin with, some of the second-wave options (for example, Forum Sentencing, Circle Sentencing, and CREDIT) had no discernible effect on rates of

re-offending (Fitzgerald 2008; Jones 2009; Lulham 2009; Donnelly, Trimboli and Poynton 2013). Second, programs that were effective in reducing re-offending (for example, Drug Courts) were never expanded to the point that they could make a material difference to the rate of entry into prison. Third, any benefits that these alternatives might have in terms of prison reduction were swamped by other factors (for example, rising rates of bail refusal, increases in the proportion of convicted offenders given a prison sentence) (see, for example, Freeman 2015).

Armed with a clearer picture of what caused the rise in Australian imprisonment rates and why efforts to stem the increase failed, we can now turn to the question of whether the benefits of the Australian prison boom have outweighed its costs. Since it is impossible to separate the contribution rising crime and tougher law and order policies made to the growth in imprisonment rates between 1975 and 2000, this discussion focuses on the period from 2001 onwards.

A key question of interest regarding benefit is whether and to what extent the reduction in crime in Australia since 2001 is attributable to the rise in imprisonment rates. To obtain an answer to this question we need a plausible estimate of the effect of prison on crime. There are two key challenges in obtaining such an estimate. The first is the omitted variable problem — finding some way of controlling for the effect of exogenous factors that may influence both imprisonment rates and crime rates. The second is the endogeneity problem — finding some way of controlling for the reciprocal effect of crime and imprisonment (see Nagin 1998 for more details on these problems).

In the last two decades, a small number of studies have emerged that have satisfactorily addressed both the omitted variable and endogeneity problems (Marvell and Moody 1994; Levitt 1996; Becsi 1999; Spelman 2000). In his review of these studies, Spelman (2000) concluded that a 10 per cent increase in the imprisonment rate in the United States (‘US’) yielded a reduction in serious crime of between 2 and 4 per cent. All the studies Spelman reviewed, however, assumed constant elasticity — they assumed that a given percentage increase in the imprisonment rate produced a constant percentage reduction in crime, regardless of the size of the prison population. In 2006, Lidka, Piehl and Useem (2006) tested this assumption and found that, as the size of the US prison population increased, prison had less and less effect on crime.

The most recent review of relevant studies (Donahue 2009) puts the effect on crime of a 10 per cent increase in the prison population at 1 to 1.5 per cent, rather than the 2 to 4 per cent suggested by Spelman. This figure fits with Wan et al (2012), who conducted a fixed effect panel analysis of crime trends across 153 Local Government Areas in NSW between 1996 and 2008. Their modelling indicates that a 10 per cent increase in the likelihood of imprisonment in NSW would produce a long-run reduction in property crime of 1.1 per cent and a long-run reduction in violent crime of 1.7 per cent.

We can use these figures to obtain an estimate of the impact of the rise in Australian imprisonment rates on crime. Erring on the side of caution, let us assume that each 10 per cent increase in the Australian prison population produces a 2 per cent reduction in crime. Between 2000 and 2014, the Australian imprisonment rate rose by 28 per cent. On the assumption just adopted, that should have reduced theft and robbery rates in Australian by around 5.6 per cent. But, in fact, over this period, break and enter fell by 67 per cent, motor vehicle theft fell by 71 per cent, robbery fell by 77 per cent, and stealing fell by 43 per cent.

What accounts for the larger-than-expected fall? Wan et al (2012) found that most of the fall in crime had stemmed from improvements in average weekly earnings (where every one percentage point rise in average weekly earnings was associated with a long-run reduction of 1.9 per cent in property crime), rather than any factors normally associated with law and order policy. There is strong reason to believe, then, that the remarkable reduction in theft and robbery offences in Australia since 2000 has had very little to do with the rising rate of imprisonment in Australia over this period. If further evidence of this were needed it is only necessary to look at trends in crime and imprisonment in Queensland. That state experienced similar falls to NSW in terms of theft and robbery offences (Queensland Police Service 2016) without any contemporaneous increase in its imprisonment rate.

What are the costs associated with Australia’s high and growing imprisonment rate? The most obvious cost is financial. It currently costs Australian state and territory governments more than A$2.6 billion a year keeping people in secure custody (SCRGSP 2015). That is enough to put more than 100 000 students through university.[†] The opportunity costs associated with high imprisonment rates are not the only drawback. When you put someone in prison you reduce their future employment and earnings prospects (Holzer 2009). This further increases the burden on the taxpayer. Quilty (2005) estimated that 38 000 Australian children experience the loss of one or both parents to prison every year. The number of men and women in prison has risen by one-third since that estimate was published. Parental incarceration has been linked with adverse effects on child development, even after controlling for family factors influencing both parental and child outcomes (Johnson 2009).

Perhaps the most insidious feature of rising imprisonment rates, however, is that they are autocatalytic. Courts are much more likely to send a person to prison if he or she has already been imprisoned, even after adjusting for other factors that influence the risk of a prison sentence (Snowball and Weatherburn 2007). So each increase in the reach of prison to offenders who would not previously have gone to prison lays the foundation for the next round of prison growth. Thus, even if the initial investment in measures designed to incarcerate more offenders makes sense from a public safety viewpoint, there is an inherent tendency for expenditure on prisons to exceed that which is warranted or intended.

Recognition of the inherent limitations of prison as a crime control tool has prompted some to call for what has become popularly known as ‘justice reinvestment.’ As originally conceived, justice investment meant taking the funds currently tied up keeping people in prison and re-investing them in services designed to reduce problems like drug dependence, poor mental health, unemployment and homelessness in areas blighted by high imprisonment rates (for example, Tucker and Cadora 2003; Brown, Schwartz and Boseley 2012). Evidence on the effectiveness of this form of intervention is not very encouraging (Rosenbaum and Schuck 2012; Bushway and Reuter 1997; Welsh and Hoshi 2002; Kain and Persky 1969), perhaps because the crime-reduction benefits of this sort of intervention do not become apparent until the children who benefit from it reach their teenage years.

There is, however, another narrower sense of justice reinvestment which holds more immediate promise. This is the transfer of resources from prison to less expensive but equally (or more) effective policies and programs designed to reduce re-offending, such as more effective community supervision and/or community-based offender rehabilitation programs (for example, Kleiman 2011; Aos, Miller and Drake 2006b). The cause of justice reinvestment in this second sense received a substantial fillip with the publication in 2006 of a report by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (‘WSIPP’) (Aos, Miller and Drake 2006b). The WSIPP report reviewed the literature on the effectiveness of various rehabilitation programs and estimated the cost and benefits of these programs compared with prison. It argued that if a model suite of correctional programs was expanded to reach 40 per cent or even just 20 per cent of the target audience, substantial reductions in the demand for prison accommodation in Washington could be achieved.

Undoubtedly there are programs that reduce the rate of recidivism (Aos, Miller and Drake 2006a). The extent to which these programs can be used to generate substantial reductions in both prisoner numbers and crime, however, depends on two key issues:

1. What scope is there for expanding the reach of our existing suite of evidence-based rehabilitation programs?

2. What contribution do convicted offenders (or those programs can reach) make to the total volume of crime?

The first issue is important because the smaller the number of offenders we reach with a suite of evidence-based rehabilitation programs, the smaller the effect the programs will have on overall levels of crime. The second issue is important for the same reason: the smaller the contribution convicted offenders make to the total volume of crime, the smaller the reduction in crime obtained when they are placed in treatment or rehabilitation programs.

The scope for expanding the reach of rehabilitation programs seems fairly limited. In Australia, the vast majority of known offenders are not placed under any form of supervision let alone placed on an evidence-based rehabilitation or treatment program. Australian Bureau of Statistics figures indicate that only 29 per cent of offenders appearing in court across Australia in 2014–15 were placed in custody or on some form of community-based order (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016b). It turns out, moreover, that many community-based sanctions involve no supervision at all (for example, fines, unsupervised bonds and suspended sentences). In NSW in 2015, for instance, only 16 per cent of non-custodial sanctions involved some form of supervision (NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research 2015a). Thus, even if a suite of evidence-based rehabilitation programs expanded to reach all those currently under some form of correctional supervision, the vast majority of known offenders would remain untouched.

The second question raised above is even more important. To determine the contribution each known offender makes to the total volume of crime (and thereby estimate the effect on crime of a reduction in re-offending), WSIPP had to estimate the number of ‘victimizations’ per convicted offender. They did so by combining information about the crimes each offender was known to have committed with an estimate of the crimes they had committed but which had not been detected. The estimate was obtained by subtracting known crimes from the total volume of crime and assuming that convicted offenders were responsible for 20 per cent of the difference.[‡] Unfortunately, as WSIPP acknowledges, the 20 per cent figure is without empirical foundation (Wilson 2015). This does not mean that the WSIPP conclusions are flawed or that their investment in offender rehabilitation is of no use in reducing prison populations. It does mean that it would be imprudent to rely on justice reinvestment (in the sense just described) to reduce Australia’s prison population. So what other options are there in the short run for restraining the growth in Australia’s imprisonment rate without jeopardising public safety?

One option would be to abolish sentences of less than six months. Fourteen per cent of all sentenced Australian prisoners are expected to serve sentences of six months or less. Short sentences are not a specific deterrent (Trevena and Weatherburn 2015), offer only limited opportunities for offender rehabilitation (Hughes 2010) and are of inherently limited incapacitation value. It is doubtful their abolition would have any effect on crime (see Wan et al 2012). It has been said that the abolition of sentences of less than six months would only prompt courts to impose sentences of greater than six months. The only evidence bearing on the issue is an unpublished evaluation of the abolition of sentences of fewer than six months by the WA Government in 2003. The analysis, which purports to show that sentence lengths increased following the reform, makes no adjustment for any changes in the profile of offenders coming before the courts. Data published by the WA crime research centre (Fernandez et al 2004; Loh et al Walsh 2007), moreover, show no evidence that magistrates in WA began imposing sentences of more than six months after 2003.

A second option would be to reduce time spent in custody. In their study of the impact of arrest and imprisonment on crime, Wan et al (2012) found no significant effect of sentence length on property or violent crime. In other words, variations in sentence length among the sentences in their sample were not correlated with variations in property or violent crime rates, after adjusting for the effect of other factors. The effect of arrest and imprisonment on crime was channeled entirely through variations in the risk of arrest and (to a lesser extent) variations in the proportion of convicted offenders imprisoned.

At present, in NSW, WA and Tasmania, parole periods must be a fixed proportion of the aggregate sentence (NSW Law Reform Commission 2013). This arrangement prevents the courts from imposing short custodial sentences followed by an extended period of supervision. One way to reduce sentence lengths would be to restore the discretion previously enjoyed by the courts to set the relationship between the so-called head or aggregate sentence and the non-parole period, at least for non-violent offences where the sentence is three years or less. Another way of reducing time spent in custody would to remove the requirement that exists in some states (for example, NSW) for offenders whose parole is revoked to wait up to a year before being able to re-apply for parole.

Queensland has adopted both of these measures. In that state, except where the sentence is greater than three years (and for certain serious offences), there is no fixed relationship between the minimum term and the aggregate sentence (Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld), s 160). In addition, following an amendment in 2006 to the Corrective Services Act, the Commissioner can amend or suspend both court and board ordered parole for a period of up to 28 days (Corrective Services Act 2006 (Qld), ss 200 and 201). This means Queensland prison authorities can respond quickly and effectively to non-serious breaches of parole without sending those who breached their parole back to prison for inordinate periods of time. These changes reduced the average time spent in custody in Queensland by 20 per cent (Rallings 2016).

A third option would be to change the approach to community corrections. As Mark Kleiman (2009) pointed out, community corrections is a system in which the chance of being caught for non-compliance is very low, but the risk of severe punishment for a detected infraction is quite high. Theory and research suggest that it would be better to focus resources on increasing the risk of detection than on increasing the severity of the penalty if caught (Nagin 2013).

Breaches of community-corrections orders account for 15 per cent of the growth in Australian prisoner numbers since 2001. In NSW, nearly two-thirds of all those given a bond or a suspended sentence are subjected to no supervision whatsoever (NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research 2015a). The chance of being detected for breaching a community-based order is very low. If an offender is caught breaching a bond or suspended sentence, however, there is a one in five chance he or she will go to prison. If the offender is caught breaching a suspended sentence, there is a 70 per cent chance he or she will go to prison (NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research 2015b). Parole Boards and courts should be given greater flexibility in responding to breaches of parole and community corrections orders that do not involve a new criminal offence.

A fourth option would be to change our approach to reducing assault. Thirty-seven per cent of the growth in Australian prisoner numbers since 2001 has come from ‘Acts Intended to Cause Injury’, most of which are assaults. There is no evidence in the national crime victim survey that assault rates or the percentage of assaults reported to police are increasing in any state or territory. Indeed, the percentage of Australians who have become a victim of assault is decreasing (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016a). In 2002, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that 4.7 per cent of Australians aged 15 years and over had been victims of assault in the preceding 12 months. The prevalence of assault has been lower than that in every year since 2008–09 (when annual Australian crime victim surveys began). In 2015, the estimated prevalence of assault was 2.1 per cent.

It is not clear whether courts are increasing the proportion of convicted assault offenders they send to prison because they mistakenly believe violence is increasing or because they feel they must reflect rising public and political concern about the problem of violence. Whatever the reason, the available evidence indicates that prison is neither a general nor a specific deterrent to assault offending (Nagin, Cullen and Jonson 2009; Menendez and Weatherburn 2015). The high desistance rate and low frequency of offending among assault offenders (Piquero, Jennings and Barnes 2012), on the other hand, suggests that imprisoning those who commit assault for lengthy periods of time exerts little in the way of incapacitation effect. From a crime control standpoint, we would be better off focusing on the factors (like alcohol) that underpin violent behaviour (see Day and Fernandez 2015).

There are, of course, non-utilitarian reasons for imposing prison terms on those who commit serious assaults. Failure to do so could undermine public confidence in the criminal justice system. It is a mistake to assume, however, that all of those entering prison for assault have committed serious assaults. In NSW, 300–400 people are sent to prison every year for common assault, the least serious form of assault. Nearly 90 per cent are given non-parole periods of six months or less.[§] These offenders could be dealt with through Intensive Correction Orders or equivalent community-based sanctions like the Community Correction Order in Victoria. At the moment in NSW, less than one per cent of offenders convicted of common assault are placed on an Intensive Correction Order (NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research 2015b).

A fifth option would be to introduce a more rational approach to bail — one based solely on a consideration of whether those charged with criminal offences are likely to abscond, interfere with witnesses or jurors, or commit further offences while on bail. New South Wales came close to introducing such a system, but retreated in response to pressure from certain sections of the media before the impact of the scheme on public safety and other outcomes could be evaluated (Brown and Quilter 2014). The result has been an increase in the prison population without any demonstrable return in terms of public safety. It is sometimes said that refusing bail has no effect on the prison population because when defendants on remand are convicted and given a prison sentence the sentence is always backdated to the point of entry into custody. This ignores the fact that a proportion of those remanded in custody are eventually acquitted. It also ignores the fact than defendants may spend longer on remand than they would have had they been dealt with more expeditiously.

The final option for state and territory governments to reduce their prison populations is by far the easiest. It requires no legal change and costs the taxpayer nothing. It involves simply toning down the political rhetoric on law and order. No magistrate or judge enjoys being singled out for public criticism by the government for a bail or sentence decision that upsets the shock jocks or tabloid media, especially when the outrage expressed is confected or ill-informed. Judges and magistrates may be independent, but they are not insensitive to public, political and media criticism. If politicians keep demanding tougher penalties, courts will eventually deliver them. This is what has been happening over the last 30 years. We can keep doing this for another 30 years or we can offer Australians a more rational, more considered approach to law and order and spend the savings on things they really want.

The results for the Holt-Winters forecast of Australian prisoners are shown below, along with a graph of the actual and predicted forecast.

|

Fit statistic

|

Mean

|

SE

|

Minimum

|

Maximum

|

Percentile

|

||||||

|

5

|

10

|

25

|

50

|

75

|

90

|

95

|

|||||

|

Stationary R-squared

|

.427

|

.

|

.427

|

.427

|

.427

|

.427

|

.427

|

.427

|

.427

|

.427

|

.427

|

|

R-squared

|

.998

|

.

|

.998

|

.998

|

.998

|

.998

|

.998

|

.998

|

.998

|

.998

|

.998

|

|

RMSE

|

129.535

|

.

|

129.535

|

129.535

|

129.535

|

129.535

|

129.535

|

129.535

|

129.535

|

129.535

|

129.535

|

|

MAPE

|

.310

|

.

|

.310

|

.310

|

.310

|

.310

|

.310

|

.310

|

.310

|

.310

|

.310

|

|

MaxAPE

|

1.019

|

.

|

1.019

|

1.019

|

1.019

|

1.019

|

1.019

|

1.019

|

1.019

|

1.019

|

1.019

|

|

MAE

|

99.026

|

.

|

99.026

|

99.026

|

99.026

|

99.026

|

99.026

|

99.026

|

99.026

|

99.026

|

99.026

|

|

MaxAE

|

296.364

|

.

|

296.364

|

296.364

|

296.364

|

296.364

|

296.364

|

296.364

|

296.364

|

296.364

|

296.364

|

|

Normalised BIC

|

9.941

|

.

|

9.941

|

9.941

|

9.941

|

9.941

|

9.941

|

9.941

|

9.941

|

9.941

|

9.941

|

|

Model

|

No of predictors

|

Model fit statistics

|

Ljung-Box Q (18)

|

No of outliers

|

||

|

Stationary R-squared

|

Statistics

|

DF

|

Sig

|

|||

|

Aust.-Model_1

|

0

|

427

|

9.299

|

15

|

.861

|

0

|

The cost of housing 43 000 people in prison was obtained by multiplying the recurrent cost per prisoner per year by real net operating expenditure per prisoner (A$224.00 per day) and then by 365 to bring it up to an annual expenditure rate. The recurrent cost per prisoner per day was obtained from the Productivity Commission Report on Government Services (SCRGSP 2015).

ABC (2008) ‘Prison Riot at Port Augusta Jail Now under Control’, The World Today, 10 October 2008 (Kevin Foley) <http://www.abc.net.au/worldtoday/content/2008/s2387748.htm>

Anderson J (2012) ‘The Label of Life Imprisonment in Australia: A Principled or Populist Approach to an Ultimate Sentence’, UNSW Law Journal 35(3), 747–78

Aos S, Miller M and Drake E (2006a) Evidence-Based Adult Corrections Programs: What Works and What Does Not, Washington State Institute for Public Policy

Aos S, Miller M and Drake E (2006b) Evidence-Based Public Policy: Options to Reduce Future Prison Construction, Criminal Justice Costs, and Crime Rates, Washington State Institute for Public Policy

Australian Bureau of Statistics (1986) Victims of Crime Australia 1983, Cat no 4506.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics (1991) Crime and Safety, New South Wales 1991, Cat no 4509.1

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2000) Crime and Safety, New South Wales 2000, Cat no 4501.1

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2001) Recorded Crime Australia 2000, Cat no 4510.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2005) Prisoners in Australia 2005, Cat no 4517.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009) Recorded Crime — Victims, 2008, Cat no 4510.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2010) Recorded Crime — Victims, 2009, Cat no 4510.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015a) Corrective Services, Australia, September Quarter 2015, Cat no 4512.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015b) Prisoners in Australia, 2015, Cat no 4517.0, <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4517.0>

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015c) Recorded Crime — Victims 2014, Cat no 4510.0

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016) Criminal Courts Australia, 2014–15, <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4513.02014-15?OpenDocument>

Australian Crime Commission (2014) 2013–14 Illicit Drug Data Report, Australian Crime Commission <apo.org.au/files/Resource/iddr-201314-complete_0.pdf>

Australian Institute of Criminology (1983) Australian Prisoners 1982

Australian Institute of Criminology (1986) Australian Prisoners 1985

Australian Institute of Criminology (1990) The Size of the Crime Problem in Australia

Australian Institute of Criminology (1995) Australian Prisoners 1993

Australian Institute of Criminology (1997) A Statistical Profile of Crime in Australia

Australian Institute of Criminology (1999) Australian Prisoners 1998

Australian Institute of Criminology (2000) Prisoners in Australia 1999

Australian Law Reform Commission (1980) Sentencing of Federal Offenders: Interim Report, Report no 31, Australian Government Publishing Service

Becsi Z (1999) ‘Economics and Crime in the States’, Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, First Quarter, 38–49

Brown D (2005) ‘Commissions of Enquiry and Penal Reform’ in S O’Toole and S Eyland (eds) Corrections Criminology, Hawkins Press, pp 42–52

Brown D and Quilter J (2014) ‘Speaking Too Soon: The Sabotage of Bail Reform in New South Wales’ The International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 3(3), 73–6

Brown D, Schwartz M and Boseley L (2012) ‘The Promise of Justice Reinvestment’, Alternative Law Journal 37(2), 96–102

Bushway S and Reuter P (2002) ‘Labor Markets and Crime Risk Factors’ in LW Sherman, D Gottfredson, D MacKenzie, J Eck, P Reuter and S Bushway (eds) Evidence-Based Crime Prevention, Routledge, 198–240

Chan J (1992) Doing Less Time: Penal Reform in Crisis, Institute of Criminology, University of Sydney

Chan J and Zdenkowski G (1986a) ‘Just Alternatives — Part 1’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 19, 67–90

Chan J and Zdenkowski G (1986b) ‘Just Alternatives — Part 11’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 19, 131–54

Cunneen C, Baldry E, Brown D, Brown M, Schwartz M and Steel A (2013) Penal Culture and Hyperincarceration: The Revival of the Prison, Ashgate

Day A and Fernandez E (2015) Preventing Violence in Australia, Federation Press

Donahue J (2009) ‘Assessing the Relative Benefits of Incarceration: Overall Changes and the Benefits on the Margin’ in S Raphael and M Stoll (eds), Do Prisons Make Us Safer: The Benefits and Costs of the Prison Boom, Russell Sage Foundation, 269–341

Donnelly N, Trimboli L and Poynton S (2013) Does CREDIT Reduce the Risk of Re-offending?, Crime and Justice Bulletin 169, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Fernandez J, Ferrante A, Loh N, Maller M and Valuri G (2004) Crime and Justice Statistics for Western Australia 2003, Crime Research Centre, University of Western Australia

Fitzgerald J (2008) Does Circle Sentencing Reduce Aboriginal Offending?, Crime and Justice Bulletin 115, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Freeman K (2015) Have the Courts Become More Lenient Over the Past 20 Years?, Bureau Brief 101, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Freiberg A (2005) ‘Sentencing’ in D Chappell and P Wilson (eds), Issues in Australian Crime and Criminal Justice, LexisNexis, 139–68

Freiberg A and Biles D (1975) The Meaning of ‘Life’: A Study of Life Sentences in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology

Freiberg A and Ross S (1999) Sentencing Reform and Penal Change, The Federation Press

Future Unlimited (2016) Education Costs in Australia, Australian Government <http://www.studyinaustralia.gov.au/global/australian-education/education-cost

Garland D (2001) The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society, Oxford University Press, 153–6

Halstead I (2015) Public Confidence in the New South Wales Criminal Justice System: 2014 Update, Crime and Justice Bulletin 182, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Health Stats NSW (2016) Methamphetamine-related Emergency Department Presentations, 19 July 2016 <http://www.healthstats.nsw.gov.au/Indicator/beh_illimethed/beh_illimethed_adm_trend?&topic

=Drug%20misuse&topic1=topic_illi&code=beh_illi>

Holzer H (2009) ‘Collateral Costs: Effects of Incarceration on Employment and Earnings among Young Workers’ in S Raphael and M Stoll (eds), Do Prisons Make Us Safer: The Benefits and Costs of the Prison Boom, Russell Sage Foundation, 239–65

Hughes M (2010) ‘Prison Governors: Short Sentences Do Not Work’, Independent (online), 21 June 2010 <http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/prison-governors-short-sentences-do-not-work-2006097.html>

Institute for Criminal Policy Research (2016) Highest to Lowest — Prison Population Total, World Prison Brief <http://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison-population-total>

Johnson RC (2009) ‘Ever-Increasing Levels of Parental Incarceration and Consequences for Children’, in S Raphael and M Stoll (eds), Do Prisons Make Us Safer: The Benefits and Costs of the Prison Boom, Russell Sage Foundation, 177–206

Jones C (2009) Does Forum Sentencing Reduce Re-offending?, Crime and Justice Bulletin 129, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

Kain JF and Persky JJ (1969) ‘Alternatives to the Gilded Ghetto’, The Public Interest, 74–87

Kleiman M (2009) When Brute Force Fails: How to Have Less Crime and Less Punishment, Princeton University Press

Kleiman M (2011) ‘Justice Reinvestment in Community Supervision’, Criminology and Public Policy 10(3), 651–9

Levitt S (1996) ‘The Effect of Prison Population Growth on Crime Rates: Evidence from Prison Overcrowding Litigation’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 111(2), 319–51

Liedka R, Piehl A and Useem B (2006) ‘The Crime-Control Effect of Incarceration: Does Scale Matter?’ Criminology and Public Policy 5(2), 245–76

Lind B, Weatherburn D, Chen S, Shanahan M, Lancsar E, Haas M and De Abreu Lourenco R (2002) NSW Drug Court Evaluation: Cost-effectiveness, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Loh N, Maller M, Fernandez J, Ferrante A and Walsh M (2007) Crime and Justice Statistics for Western Australia 2005, Crime Research Centre, University of Western Australia

Lulham R (2009) The Magistrates Early Referral Into Treatment Program: Impact of Program Participation on Re-offending by Defendants with a Drug Use Problem, Crime and Justice Bulletin 131, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

McInnes L and Jones C (2010) Trends in the Use of Suspended Sentences, Bureau Brief 47, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Marchetti E and Daly K (2004) Indigenous Courts and Justice Practices in Australia, Trends and Issues in Crime and Justice No 277

Marvell T and Moody C (1994) ‘Prison Population Growth and Crime Reduction’, Journal of Quantitative Criminology 10(2), 109–40

Menendez P and Weatherburn D (2014) The Effect of Suspended Sentences on Imprisonment, Bureau Brief 97, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Menendez P and Weatherburn D (2015) ‘Does the Threat of Longer Prison Terms Reduce the Incidence of Assault?’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, doi: 10.1177/0004865815575397

Mukherjee S, Carcach C and Higgens K (1997) A Statistical Profile of Crime in Australia, Australian Institute of Criminology

Mukherjee S, Scandia A, Dagger D and Matthews W (1989) Sourcebook on Criminal and Social Statistics 1804–1988, Australian Institute of Criminology

Nagin DS (1998) ‘Criminal Deterrence Research at the Outset of the Twenty-first Century’ in M Tonry (ed), Crime and Justice: A Review of Research vol 23, University of Chicago Press, 1–42

Nagin D, Cullen F and Jonson C (2009) ‘Imprisonment and Re-offending’ in M Tonry (ed), Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research vol. 38, University of Chicago Press, 115–200

Nagin DS (2013) ‘Deterrence: A Review of the Evidence by a Criminologist for Economists’, Annual Review of Economics 5, 83–105

Noonan G (2005), ‘Record Number in Jail Carr Boasts’, The Sydney Morning Herald (online),

14 January 2005 <http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/record-number-in-jail-carr-boasts/2005/01/

13/1105582657317.html>

NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2015a) New South Wales Criminal Courts Statistics 2014, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2015b) Unpublished data available on file with author

NSW Law Reform Commission (2013) Sentencing, NSW Law Reform Commission

O’Toole S (2006) The History of Australian Corrections, UNSW Press

Piquero AR, Jennings WG and Barnes JC (2012) ‘Violence in Criminal Careers: A Review of the Literature from a Developmental Life-course Perspective’, Aggression and Violent Behaviour 17, 171–9

Productivity Commission (1995) Report on Government Services 1995, Commonwealth of Australia

Queensland Police Service (2016) Reported Crime Trend Data, 12 July 2016 <https://www.police.qld.gov.au/online/data/default.htm>

Quilty S (2005) ‘The Magnitude of Experience of Parental Incarceration in Australia’, Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 12(1), 256–7

Rallings M (2016) Unpublished data provided to the author by Commissioner Mark Rallings

Rozenbaum DP and Schuck AM (2012) ‘Comprehensive Community Partnerships for Preventing Crime’ in BC Walsh and DP Farrington (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Crime Prevention, Oxford University Press, 226–68

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) (2015) Report on Government Services 2015, Productivity Commission

Snowball L and Weatherburn D (2007) ‘Does Racial Bias in Sentencing Contribute to Indigenous

Over-representation in Prison?’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 40(3), 272–90

Spelman W (2000) ‘What Recent Studies Do (and Don’t) Tell Us About Imprisonment and Crime’ in M Tonry (ed.), Crime and Justice: A Review of Research vol 27, University of Chicago Press, 419–94

Trevena J and Weatherburn D (2015) Does the First Prison Sentence Reduce the Risk of Further Offending? Crime and Justice Bulletin 187, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Tucker SB and Cadora E (2003) Justice Reinvestment, IDEAS for an Open Society 3, 2–5

van Dijk J, Mayhew P and Killias M (1990) Experiences of Crime across the World: Key findings from the 1989 International Crime Survey, Kluwer

Victorian Sentencing Council (2006) Suspended Sentences: Final Report — Part 1, Victorian Sentencing Council

Wan W, Moffatt S, Jones C and Weatherburn D (2012) The Effect of Arrest and Imprisonment on Crime, Crime and Justice Bulletin 158, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research

Warner K (2002) Sentencing in Tasmania, Federation Press

Welsh BC and Hoshi A (2002) ‘Communities and Crime Prevention’ in L Sherman, D Gottfredson, D MacKenzie, J Eck, P Reuter and S Bushway (eds), Evidence-Based Crime Prevention, Routledge, 198–240

Wilson M (2015) MW Consulting, Personal Communication, 11 December 2015

Wilson P (1971) ‘Crime and the Public’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 4(4), 223–32

[*] Director, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Level 1, Henry Deane Building, 20 Lee Street Sydney NSW 2000 Australia. Email: don.weatherburn@justice.nsw.gov.au. An earlier version of this article was presented as a Sydney Institute of Criminology 50th Anniversary Lecture on 11 May 2016. I would like to express my gratitude to Lorana Bartels, Luke Grant, Jackie Fitzgerald, Imogen Halstead and Jason Hainsworth for comments on earlier drafts of this article.

[†] Based on the assumption that a university degree costs A$24 000 (the median value from figures provided by the Australian Government (Future Unlimited 2016).

[‡] For full details contact the author.

[§] Unpublished data, available from the author.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/CICrimJust/2016/21.html