|

[Home]

[Databases]

[WorldLII]

[Search]

[Feedback]

Federal Judicial Scholarship |

The Role of the Trial Court Judge in Pre-trial

Management

Manila July 2004

Justice RS French

Federal Court of Australia

Introduction – The Judicial Function

In both the Philippines and Australia the Courts are organised and classified by reference to their jurisdictions, that is the kinds of cases which they are authorised to decide. The judges who are appointed to the courts are generally accorded a status which corresponds to the range and importance of the cases which they are authorised to decide. That status may be reflected in their remuneration and the terms and conditions under which they work.

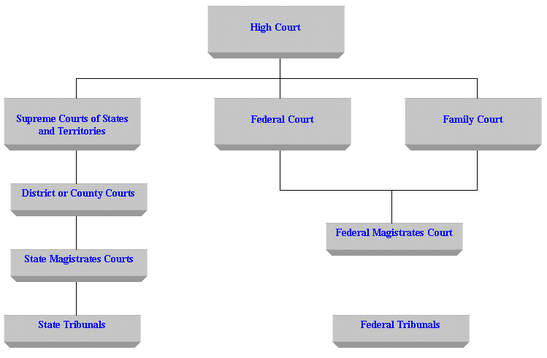

The hierarchy of courts in Australia ranges from Magistrates Courts which deal with the lowest range but, generally, the highest volume of civil and criminal cases. Then in each State there is a District Court or County Court. These courts bear the burden of the majority of serious criminal cases and civil actions within a limited pecuniary value, including personal injuries claims which are unlimited as to value. The Supreme Courts of the States and Territories comprise both trial courts, which deal with the most serious crime and the most important civil matters in the State judicatures and Appeal Courts. The Appeal Courts sit generally in benches of three to hear appeals from decisions of the lower courts or from single judge decisions in the Supreme Court.

There are also Federal Courts including a Federal Magistrates Court, the Federal Court of Australia and the Family Court of Australia. The Federal Court and the Family Court both exercise trial and appellate functions. A judge of the Federal Court who decides cases at first instance may be the subject of an appeal to a bench of three, and in particularly important cases, to a bench of five.

The High Court of Australia is the final Court of Appeal for all other courts in the country. An outline of the structure of the Australian Court system is Annexure 1 to this paper.

Whatever their place in the Federal or State Court systems and whatever their status, the function of judges is the same. It has been described in the High Court, by reference to the judicial power as follows:

‘The unique and essential function of the judicial power is the quelling of ... controversies by ascertainment of the facts, by application of the law and by exercise, where appropriate of judicial discretion.’ [1]

This judicial definition resembles the definition of judicial power, which appears in Article VIII s 1 of the 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines:

‘Judicial power includes the duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally decidable and enforceable and to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of government.’

Under the Philippines Constitution the judicial power so defined is vested in the Supreme Court and ‘in such lower courts as may be established by law’. In Australia and the Philippines the essential decision-making function of the judge at the trial and appellate levels is the same.

The Emergence of Managerial Judging

In the English tradition, as

inherited by the Australian courts, the function of the trial judge was simply

to hear and decide the

cases within jurisdiction. The progress of matters from

commencement to trial was left in the hands of the parties. So too was

the

presentation of the evidence and the definition of the issues. The

judge’s function at trial was primarily to ensure a

fair process and as

part of that function to regulate the reception of evidence according to the

rules of evidence.

The position of the judge as a person detached from the requirements of efficiency and the economies of litigation goes beyond the English tradition. In the 16th century satire ‘The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel’, Francois Rabelais told the story of Bridlegoose, a judge of advancing years and failing sight who decided his cases a long time after they began by a throw of dice. When undergoing impeachment proceedings for his poor judicial management he justified his delays by reference to a lot of old legal proverbs such as:

‘Time is the father of truth.’

He spoke of the need for a case to ‘come to maturity’ so that the decision might be borne more patiently by the losing party. One of the Latin proverbs he relied upon was:

‘Dulcior est fructus post multa pericula ductus’

which translates as:

‘A fruit is sweeter for having survived many dangers.’

Costs and delay in the legal systems of the world have been the subject of complaint and satire for many years. The works of Shakespeare Dickens contain examples of attacks upon, and satire of, the courts. Ambrose Bierce, the American satirist, defined justice in his ‘Devil’s Dictionary’ as:

‘A commodity which in a more or less adulterated condition the State sells to the citizen as a reward for his allegiance, taxes and personal service.’

The party-controlled approach to litigation is a defining feature of the purely adversarial process. It rests upon the assumption that the fairest and most effective way of getting to the truth in a dispute is to allow the parties to put their own cases in their own way. It has defects including the feature that party choices may result in a case being run in such a way as to consume a disproportionate amount of litigant and judicial resources. The underlying premise also fails when there is significant inequality of resources between the parties.[2] The adversarial approach is frequently contrasted with the procedures of civil code countries which involves a considerable amount of investigative work being carried out by a neutral judicial officer. Although sometimes the term ‘inquisitorial’ is applied to the continental civil justice system this may not be an accurate generalisation. In France the court can only determine the case presented and the plaintiff must still prove its case.[3] On the other hand a German judge speaking at a conference in Australia in 1997 said of the German civil procedure:

‘It will be apparent that the judge virtually knows the result of the case before the hearing.’ [4]

The labels ‘adversarial’ and ‘inquisitorial’ may be thought of as reflecting extremes points in a spectrum of approaches to litigation. Between them are hybrids involving greater or lesser degrees of judicial management.

No system of judicial decision-making is proof against the problems of cost and delay. The resolution of legal disputes is inescapably labour intensive. It requires careful consideration, by whatever means, of evidence, findings of fact and the application of the law, be it written or unwritten, to the facts as found. In recent years, however, in Australia and other countries increasingly well-educated and assertive consumers of judicial services have made greater demands on government and its institutions, including the judiciary, to be responsive to their needs in terms of the costs and efficiency. In Australia there has been a wide range of reactions to such concerns which have been reflected in the movement to increased judicial supervision of litigation and also the development of non-judicial dispute resolution options. In a comparative analysis of the adversarial and civil code systems, A Zuckerman observed:

‘Both Commonwealth countries and civil law countries display a shift towards the imposition of a stronger control by judges over the progress of civil litigation. In virtually all the systems reviewed here there is a perception that, when the process of litigation is left to the parties and their lawyers, its progress is impeded by narrow self-interest. Such self-interest may be that of recalcitrant defendants bent on exhausting and tormenting their plaintiffs or that of self-interest of lawyers determined to enhance their own incomes.

The contemporary dominant view is that the disruptive self-interest of parties and their lawyers can only be kept at bay by an active judiciary that directs the litigation process and is able to prevent disruptive tactics. The USA has been leading the trend amongst common law countries. A culture of managerial judges is now well established there. In England and Australia the move towards judicial control is more recent but is equally dramatic.

A similar trend is reported from the great majority of civil law countries. In France, Spain, Portugal, Italy and even in Japan and in Germany, moves are afoot to strengthen the judicial supervision of the litigation process.’ [5]

The Australian Law Reform Commission’s major report on the Federal Civil Justice System published in January 2000 said (at 1.129):[6]

‘... in the Australian civil justice system processes such as case management, court or tribunal connected ADR processes, and discretionary rules of evidence and procedure, have modified the adversarial nature of the system.’

Rationing Justice – Beyond Parties to the Public

Interest

Australian judges recognise in principle that justice

should be achieved, as far as possible, expeditiously and economically. The

time and human resources of courts are not unlimited and sometimes decisions

about the progress of one case, be they decisions about

adjournments or

amendments which may force adjournments or delays, can affect the availability

of court resources for other cases.

The substantive goal of courts

remains always to do justice between parties according to law, an objective.

This objective is not

to be compromised by undue rigidity in the application of

procedural requirements which are ancillary to it. The purest statement

of that

proposition in the English legal tradition came from Lord Justice Bowen in

Cropper v Smith [1884] UKLawRpCh 91; [1884] 26 Ch D 700 at 710:

‘... it is a well established principle that the object of courts is to decide the rights of the parties, and not to punish them for mistakes they make in the conduct of their cases by deciding otherwise than in accordance with their rights.’

He went on to say in that vein:

... I know of no kind of error or mistake which, if not fraudulent or intended to overreach, the court ought not to correct, if it can be done without injustice to the other party.’

It is plain enough that the procedural requirements attending the preparation for, and conduct of, litigation must be sufficiently flexible to make reasonable allowance for human error. In Cropper v Smith, Lord Justice Bowen considered that there was one panacea which would heal every sore in litigation and that was costs. That assumes that the only rights to be adjusted are those between the litigating parties. It also assumes that a purely financial adjustment will correct the imbalance arising from the delay or unnecessary expense incurred by reason of one party’s error or omission. One hundred and twenty years later, those assumptions have been overtaken by the realities of modern litigation. A former Chief Justice of South Australia observed, in 1984, that judges now have a responsibility to ensure, so far as possible and subject to overriding considerations of justice, that the limited resources which the State commits to the administration of justice are not wasted by failure of parties to adhere to trial dates of which they have had proper notice.[7] In the House of Lords in 1987 consideration was given to whether an amendment to pleadings should have been permitted at the close of a trial. It was noted that among the factors to be weighed in the balance was:

‘... the pressure on the courts caused by the great increase in litigation and the consequent necessity that, in the interests of the whole community, legal business should be conducted efficiently. We can no longer afford to show the same indulgence towards the negligent conduct of litigation as was perhaps possible in a more leisured age. There will be cases in which justice will be better served by allowing the consequences of the negligence of the lawyers to fall upon their own heads rather than by allowing an amendment at a very late stage of the proceedings.’ [8]

Beyond the public interest there is the strain that delay imposes on litigants the anxieties occasioned by facing new issues, the raising of false hopes and the legitimate expectation that a trial will determine the issues one way or the other.[9] This very much reflects the approach in the Federal Court which, in 1991, was expressed thus:

‘The public cost of maintaining the system of courts which this country has is considerable. Those who are privileged to practise before the courts should understand that the days when careless work will usually be overlooked are over. The profession charges high fees for the work which it does. It has a responsibility to see that the work is done well. The day has come when failure to discharge professional obligations efficiently will not be to the account of the community or of the parties but to the account of the profession itself.’ [10]

These issues arise most frequently in the context of applications for adjournments of trial dates and late applications for amendment raising new issues of fact which may in turn affect the capacity to proceed with a trial on the dates fixed if they are allowed. The public interest is not just in seeing justice done between parties. It is also ensuring that all litigants have a reasonable prospect of timely access to the courts and that the hearing and determination of one litigant’s case is not unfairly prejudiced by reason of delays and the unnecessary use of court time in other litigation which is poorly managed by the advisors and by the judge.

Case Management Generally

There are many models of case management

by courts which may involve judges and/or other court officials such as masters

or registrars

controlling the progress of litigation from the time of

commencement. This is to ensure that a proceeding is ready for trial within

a

reasonable time, that the real issues in dispute have been identified and that

the presentation of evidence will be as economic

and expeditious as possible.

The Australian Law Reform Commission in its report on ‘Managing Justice’ identified general principles for effective practices in case management:

‘Generally courts and tribunals need to monitor cases from the start and maintain supervision throughout so that they know if a case is off track and not meeting time standards or complying with directions. This supervision can be undertaken electronically as well as by judges, members or registrars. Successful case management requires judicial and member commitment and leadership and consultation with the legal profession. Most courts and tribunals have time standards and goals to measure case progress and utilise ‘short-schedule’ event techniques and procedures to prompt lawyers into, for example, filing documents before the set case event so that the event accomplishes its objectives. Given the cooperative interchange required in effective case management, courts and tribunals have to ensure lawyers do not accommodate one another to the prejudice of the parties and the efficiency of the court or tribunal. Listing dates must be credible and adjournments controlled. Courts and tribunals need to create among lawyers and parties an expectation that events will occur when scheduled.’[11]

It has been the case from the outset in the Federal Court that the Court always remains in overall control of the proceedings before it. The judges have power until the hearing is concluded to make and continue to make such directions as seem to them best suited properly and adequately to manage and direct the cases in their lists. They will always pay attention to what the parties themselves suggest and will usually accept agreed timetables for procedural steps. But if it emerges that existing directions are not adequate for or are not suited to the needs of the case the Court will substitute appropriate directions for the existing ones and, if necessary, against the will of the parties. In complex cases the Court may hold quite extensive directions hearing to identify the real issues, the extent of the evidence and what can be done to confine or limit the evidence and the amount of time the case will take in the Court’s calendar.[12] As one of the Court’s most senior judges recently wrote:

‘In practice the court has accepted, from its establishment under Chief Justice Bowen in 1977, that there is no laissez-faire option: the size and complexity of litigation brought to the court for resolution is such that a fair, but firm, control of every stage of proceedings in each matter is essential if litigation is to be properly dealt with.’ [13]

Some Specifics of Case Management in the Federal Court

Under the Individual Docket System which now operates throughout the Court, when a case is filed in Court it is ordinarily allocated, on a rotational basis, to the docket of a particular judge. A first directions hearing will be fixed at the time of filing. The source of power for making directions and the framework within which judicial case management operates is Order 10 of the Federal Court Rules. The text of that Order is annexed to this paper as Annexure 2.

When the first directions hearing comes on the parties will appear before the docket judge and seek programming orders which may relate to:

When a Federal Court Judge gives directions for pre-trial programming there will be a date fixed for a resumed directions hearing specified unless the judge fixes a trial date on the spot or alternatively gives a direction that at the end of series of steps required to be taken the parties are to apply to the registrar for a trial date. It is my rule, and I think that of most judges, never to adjourn a directions hearing without a date at which the parties have to come back to court. To adjourn a directions hearing indefinitely is to invite litigious drift.

Parties may need to be reminded that even if made by consent, directions given by the Court are orders of the Court and are to be obeyed as such. Where it appears to a party that a time limit for taking a step set out in programming directions is not going to be met then it is incumbent on the party to apply to the Court before the expiry of that time limit in order to obtain an extension. Very often such extensions will be agreed by consent, a consent minute can be filed in Court and a direction made by the judge varying the previous orders. There is no requirement for the parties to appear in Court in such a case. The judge however retains ultimate control. If there are repeated extensions sought and it appears that the process is getting out of hand without any adequate explanation being offered, then the judge can call the parties back into Court to justify the extensions sought.

Sometimes parties will tell the Court that the reason they want an extension is because they are negotiating a settlement. Such negotiations can drag on with repeated requests for suspension of the pre-trial programming process. Generally they are likely to proceed more efficiently and expeditiously if there is a time limit to focus the minds of those participating. This can be created in one or more ways. One way is to fix a trial date well in advance and a set of programming directions to be adhered to from a date a little less in advance so that the parties know that after a certain time they will be locked into preparation for trial. Another is to make a springing order that the application will stand dismissed unless a particular step is taken by the applicant before a certain date. Again, the operation of the springing order can be timed sufficiently far in advance to allow for some scope for negotiation with the understanding that there is a cut off point after which if negotiation continues it must continue in tandem with pre-trial preparation.

Generally, programming directions given at a first directions are fairly routine. They will canvass the essential elements of pleadings, particulars, discovery, interrogatories and the like. There is, however, a number of other interlocutory steps which may have to be addressed at the first directions hearing or at a subsequent hearing. These include:

Further down the pre-trial process issues will arise including

the mode of trial and whether it should be by oral evidence-in-chief,

evidence-in-chief on affidavit subject to cross-examination, or

evidence-in-chief given by signed witness statements affirmed or

sworn to by the

witnesses who are then subject to cross examination. There may be a question

whether the issues at trial should

be separated. If there is a threshold issue

or preliminary question should it be heard separately. This procedure has to be

adopted

with care. It can result in undue fragmentation of the litigation with

interlocutory appeals.

At a certain point in the pre-trial program the question of alternative dispute resolution and referral to mediation will have to be considered. Under the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) the Court has power to refer proceedings in the Court or any part of them, or any matter arising out of them, to a mediator or an arbitrator for mediation or arbitration as the case may be in accordance with the Rules of Court.[14] There is also provision for referrals to a mediator to be made with or without the consent of the parties.[15] Sometimes mediation may involve early neutral evaluation and may also involve a judge of the Court as a mediator or evaluator although this tends to happen fairly rarely. Mediation is mostly conducted by registrars of the Court. Where a judge does participate in mediation or early neutral evaluation the process is confidential and the judge must not discuss the process or its outcomes with the trial judge or indeed with any one outside the mediation or evaluation participants.

The question of subpoenas may arise. The issue of subpoenas is controlled in the Federal Court by a requirement for leave. This can be dealt with by a registrar but is sometimes dealt with by the judge. In some cases of a complex nature I have invited the potential respondents to subpoenas to be present at the leave application in order that there may be sensible negotiation of the scope of documents being sought and the way in which they may be produced. Where time is short this may avoid the necessity of a second round of applications seeking to set aside a subpoena when it has been served. It is important to remember that subpoenas are coercive processes which may interfere with the private rights of third parties who are not involved in the litigation. There is expense and inconvenience involved when the subpoena requires the production of documents. It was complained at one time that subpoenas would issue like confetti, often a few days or hours before the beginning of a trial to which they related. The leave requirement now allows for some judicial control of that process.

Directions may have to be given in relation to expert witnesses. The

role of expert witnesses has come under increased scrutiny in

recent times

because of perceived partisanship. There is a practice guideline for expert

witnesses issued by the Chief Justice of

the Federal Court, a copy of which is

attached as Annexure 3. The directions for expert witnesses may include

directions relating

to compulsory conferences of experts to try and reduce the

areas in dispute between them. The Court also has a rule under which

it may

treat all or part of a testimony of an expert witness as submission rather than

as evidence. This is particularly applicable

in those cases where the expert

testimony is really just about the characterisation of primary facts. So the

evidence of economists

in competition law cases will often involve questions of

characterisation and argument such as what the limits of a market for the

purposes of the relevant competition law.

Not all of these procedures have to be dealt with in the formal courtroom setting of a directions hearing. The technique of a case management conference may be adopted. This involves the judge sitting around a conference table with the parties and their advisors to discuss the best way to approach pre-trial management and the conduct of the trial. Whilst in a formal sense it is still a directions hearing and formal orders will be made at the end of it, the ‘psychological landscape’ is less adversarial than that which exists in a courtroom. There is more scope for the parties and their advisors to take a reasonably practical approach to ensuring that the case gets on expeditiously and narrows down to the real issues. In a sense it is a kind of procedural mediation or discussion chaired by the trial judge. It is a technique which I have found particularly useful in cases in which there is a multiplicity of parties or where there is major litigation which has to be brought on within a short timeframe.

Conclusion

The statutory framework and the Rules of Court

within which trial judges operate can only provide the scaffolding upon which

they

must construct the plan that best suits the efficient and economical and

fair conduct of any particular proceeding.

The way in which a trial judge shapes the management of proceedings before him or her will depend upon the circumstances of those proceedings and also upon the knowledge and experience of the judge. Much of that knowledge can only be gained and internalised by actual practical experience. Other aspects can be learnt from peers and associates. Ultimately, however, pre-trial case management should be a flexible, rather than hide bound, process which is shaped to the circumstances of the particular case and so that at all times rules and procedures serve their proper functions as aids to the judge’s core function, that of deciding the case.

ANNEXURE 1

Federal Tribunals

High Court

Federal Magistrates Court

State

Tribunals

State Magistrates Courts

District or County Courts

Federal

Court

Family Court

Supreme Courts of States and Territories

![]()

ANNEXURE 2

FEDERAL COURT RULES

- ORDER 10 RULE 1

Directions

hearing — general

(1)

On a directions hearing the Court shall give such directions with respect to

the conduct of the proceeding as it thinks proper.

(1A)

In any proceeding which is to be heard by a Full Court, whether in the

original or appellate jurisdiction, such directions as is thought

proper with

respect to the conduct of the proceeding may be given by the Court constituted

by a single Judge.

(2)

Without prejudice to the generality of subrule (1) or (1A) the Court may:

(a)

make orders with respect to:

(i)

discovery and inspection of documents;

(ii)

interrogatories;

(iii)

inspections of real or personal property;

(iv)

admissions of fact or of documents;

(v)

the defining of the issues by pleadings or otherwise;

(vi)

the standing of affidavits as pleadings;

(vii)

the joinder of parties;

(viii)

the mode and sufficiency of service;

(ix)

amendments;

(x)

cross-claims;

(xi)

the filing of affidavits;

(xii)

the giving of particulars;

(xiii)

the place, time and mode of hearing;

(xiv)

the giving of evidence at the hearing, including whether evidence of

witnesses in chief shall be given orally or by affidavit, or

both;

(xv)

the disclosure of reports of experts;

(xvi)

costs;

(xvii)

the filing and exchange of signed statements of evidence of intended

witnesses and their use in evidence at the hearing;

(xviii)

the taking of evidence and receipt of submissions by video link, or audio

link, or electronic communication, or such other means as

the Court considers

appropriate;

(xix)

the proportion in which the parties are to bear the costs (if any) of taking

evidence or making submissions in accordance with a direction

under

subparagraph (xviii); and

(xx)

the use of assisted dispute resolution (including mediation) to assist in the

conduct and resolution of all or part of the proceeding.

(aa)

where, in any proceeding commenced in respect of any alleged or threatened

breach of a provision of Part IV of the Trade Practices Act 1974, an

order pursuant to section 80 of that Act is sought, direct that notice be

given of the order sought by public advertisement or in such other form as the

Court

directs;

(b)

notwithstanding that the application is supported by a statement of claim,

order that the proceeding continue on affidavits;

(c)

order that evidence of a particular fact or facts be given at the hearing:

(i)

by statement on oath upon information and belief;

(ii)

by production of documents or entries in books;

(iii)

by copies of documents or entries; or

(iv)

otherwise as the Court directs;

(ca)

order that an agreed bundle of documents be prepared by the parties;

(cab)

direct that the parties give consideration to jointly instructing an expert

to provide to the parties a report of the expert's opinion

in relation to a

particular issue or issues in the proceeding, on the basis that the parties

concerned will be jointly responsible

to pay the expert's fees and expenses;

(d)

order that no more than a specified number of expert witnesses may be called;

(da)

order that the reports of experts be exchanged;

(e)

appoint a court expert in accordance with Order 34, rule 2;

(f)

direct that the proceeding be transferred to a place at which there is a

Registry other than the then proper place. Where the proceeding

is so

transferred, the Registrar at the proper place from which the proceeding is

transferred shall transmit all documents in his

charge relating to the

proceeding to the Registrar at the proper place to which the proceeding is

transferred;

(g)

order, under Order 72, that proceedings, part of proceedings or a matter

arising out of proceedings be referred to a mediator or arbitrator;

(h)

order that the parties attend before a Registrar for a conference with a view

to satisfying the Registrar that all reasonable steps

to achieve a negotiated

outcome of the proceedings have been taken, or otherwise clarifying the real

issues in dispute so that appropriate

directions may be made for the disposition

of the matter, or otherwise to shorten the time taken in preparation for and at

the trial;

(i)

in a case in which the Court considers it appropriate, direct the parties to

attend a case management conference with a Judge or Registrar

to consider the

most economic and efficient means of bringing the proceedings to trial and of

conducting the trial, at which conference

the Judge or Registrar may give

further directions;

(j)

in proceedings in which a party seeks to rely on the opinion of a person

involving a subject in which the person has specialist qualifications,

direct

that all or part of such opinion be received by way of submission in such manner

and form as the Court may think fit, whether

or not the opinion would be

admissible as evidence.

(3)

The Court may revoke or vary any order made under (1), (1A) or (2).

(4)

Paragraph (aa) of subrule (2) does not limit the power of the Court to direct

at any stage of the proceeding that such notice be given.

![]()

ANNEXURE 3

Practice Direction : Guidelines for Expert Witnesses in Proceedings in the

Federal Court of Australia

This Practice Direction replaces the Practice

Direction on Guidelines for Expert Witnesses in Proceedings in the Federal Court

of

Australia issued on 4 September 2003.

Practitioners should give a copy

of the following guidelines to any witness they propose to retain for the

purpose of preparing a

report or giving evidence in a proceeding as to an

opinion held by the witness that is wholly or substantially based on the

specialised

knowledge of the witness (see - Part 3.3 - Opinion of the Evidence Act

1995 (Cth)).

M.E.J. BLACK

Chief Justice

19 March

2004

Explanatory Memorandum

The guidelines are not intended to

address all aspects of an expert witness’s duties, but are intended to

facilitate the admission

of opinion evidence (footnote #1), and to assist experts

to understand in general terms what the Court expects of an expert witness

giving opinion evidence. Additionally,

it is hoped that the guidelines will

assist individual expert witnesses to avoid the criticism that is sometimes made

(whether rightly

or wrongly) that expert witnesses lack objectivity, or have

coloured their evidence in favour of the party calling them.

Ways by which an

expert witness giving opinion evidence may avoid criticism of partiality include

ensuring that the report, or other

statement of evidence:

(a) is clearly

expressed and not argumentative in tone;

(b) is centrally concerned to

express an opinion, upon a clearly defined question or questions, based on the

expert’s specialised

knowledge;

(c) identifies with precision the

factual premises upon which the opinion is based;

(d) explains the process of

reasoning by which the expert reached the opinion expressed in the

report;

(e) is confined to the area or areas of the expert’s

specialised knowledge; and

(f) identifies any pre-existing relationship

between the author of the report, or his or her firm, company etc, and a party

to the

litigation (eg a treating medical practitioner, or a firm’s

accountant).

An expert is not disqualified from giving evidence by reason

only of the fact of a pre-existing relationship with the party that proffers

the

expert as a witness, but the nature of the pre-existing relationship should be

disclosed. Where an expert has such a relationship

with the party the expert may

need to pay particular attention to the identification of the factual premises

upon which the expert’s

opinion is based. The expert should make it clear

whether, and to what extent, the opinion is based on the personal knowledge of

the expert (the factual basis for which might be required to be established by

admissible evidence of the expert or another witness)

derived from the ongoing

relationship rather than on factual premises or assumptions provided to the

expert by way of instructions.

All experts need to be aware that if they

participate to a significant degree in the process of formulating and preparing

the case

of a party, they may find it difficult to maintain objectivity.

An

expert witness does not compromise objectivity by defending, forcefully if

necessary, an opinion based on the expert’s specialised

knowledge which is

genuinely held but may do so if the expert is, for example, unwilling to give

consideration to alternative factual

premises or is unwilling, where

appropriate, to acknowledge recognised differences of opinion or approach

between experts in the

relevant discipline.

The guidelines are, as their

title indicates, no more than guidelines. Attempts to apply them literally in

every case may prove unhelpful.

In some areas of specialised knowledge and in

some circumstances (eg some aspects of economic “evidence” in

competition

law cases) their literal interpretation may prove unworkable. The

Court expects legal practitioners and experts to work together

to ensure that

the guidelines are implemented in a practically sensible way which ensures that

they achieve their intended purpose.

Guidelines

1. General Duty

to the Court (footnote

#2)

1.1 An expert witness has an overriding duty to assist the Court on

matters relevant to the expert’s area of expertise.

1.2 An expert

witness is not an advocate for a party.

1.3 An expert witness’s

paramount duty is to the Court and not to the person retaining the

expert.

2. The Form of the Expert Evidence (footnote #3)

2.1 An

expert’s written report must give details of the expert’s

qualifications, and of the literature or other material

used in making the

report.

2.2 All assumptions of fact made by the expert should be clearly and

fully stated.

2.3 The report should identify who carried out any tests or

experiments upon which the expert relied in compiling the report, and

state the

qualifications of the person who carried out any such test or experiment.

2.4

Where several opinions are provided in the report, the expert should summarise

them.

2.5 The expert should give reasons for each opinion.

2.6 At the end

of the report the expert should declare that “[the expert] has made all

the inquiries which [the expert] believes

are desirable and appropriate and that

no matters of significance which [the expert] regards as relevant have, to [the

expert’s]

knowledge, been withheld from the Court.”

2.7 There

should be included in or attached to the report (i) a statement of the questions

or issues that the expert was asked to

address; (ii) the factual premises upon

which the report proceeds; and (iii) the documents and other materials which the

expert has

been instructed to consider.

2.8 If, after exchange of reports or

at any other stage, an expert witness changes a material opinion, having read

another expert’s

report or for any other reason, the change should be

communicated in a timely manner (through legal representatives) to each party

to

whom the expert witness’s report has been provided and, when appropriate,

to the Court (footnote

#4).

2.9 If an expert’s opinion is not fully researched because the

expert considers that insufficient data are available, or for

any other reason,

this must be stated with an indication that the opinion is no more than a

provisional one. Where an expert witness

who has prepared a report believes that

it may be incomplete or inaccurate without some qualification, that

qualification must be

stated in the report (footnote #4).

2.10 The expert

should make it clear when a particular question or issue falls outside the

relevant field of expertise.

2.11 Where an expert’s report refers to

photographs, plans, calculations, analyses, measurements, survey reports or

other extrinsic

matter, these must be provided to the opposite party at the same

time as the exchange of reports (footnote #5).

3. Experts’

Conference

3.1 If experts retained by the parties meet at the direction of

the Court, it would be improper conduct for an expert to be given

or to accept

instructions not to reach agreement. If, at a meeting directed by the Court, the

experts cannot reach agreement about

matters of expert opinion, they should

specify their reasons for being unable to do

so.

footnote#1

As to the distinction between expert

opinion evidence and expert assistance see Evans Deakin Pty Ltd v Sebel

Furniture Ltd [2003] FCA 171 per Allsop J at

[676].

footnote #2

See rule 35.3 Civil Procedure Rules

(UK); see also Lord Woolf “Medics, Lawyers and the Courts” [1997] 16

CJQ 302 at 313.

footnote #3

See rule 35.10 Civil

Procedure Rules (UK) and Practice Direction 35 – Experts and Assessors

(UK); HG v the Queen [1999] HCA 2; (1999) 197 CLR 414 per Gleeson CJ at [39]-[43]; Ocean

Marine Mutual Insurance Association (Europe) OV v Jetopay Pty Ltd [2000] FCA

1463 (FC) at [17]- [23]

footnote #4

The “Ikarian

Reefer” [1993] 20 FSR 563 at 565

footnote #5

The

“Ikarian Reefer” [1993] 20 FSR 563 at 565-566. See also Ormrod

“Scientific Evidence in Court” [1968] Crim LR 240.

[1] Fencott v

Muller (1983) 152 CLR 570 at

608

[2] Dietrich

v R [1992] HCA 57; (1992) 177 CLR 292 at 335 (Deane J);

[3] Lariviere DS

(1996) New code of civil procedure articles 5 and 9 IN Overview of the Problems

of French civil procedure, Unpublished

manuscript Joint Law Courts Library,

Sydney and see Beaumont B, (2000) Managing Litigation in the Federal Court IN

Opeskin, Brian

and Wheeler, Fiona (eds). The Australian Federal Judicial System.

Carlton South, Vic, Melbourne University Press at p

165.

[4] Glomb, K

(1997) Roles and Skills of a German Judge IN Beyond the Adversarial System

Conference 10-11 July 1997.

[5] Zuckerman,

Adrian AS (1999) Justice in crisis: comparative dimensions of civil procedure

IN Zuckerman , Adrian AS (ed), Chiarloni, Sergio and Gottwald, Peter

(consultant eds). Civil justice in crisis: Comparative perspectives

of civil

procedure. Oxford, Oxford University Press at pp

47-48

[6]

Australian Law Reform Commission (2000) Managing justice: a review of the

federal civil justice system

[7] Dawson v

Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1984) 71 FLR 364 at 366 per King

CJ

[8] Kettleman

v Hansel Properties Ltd [1987] 1 AC 189 at

220

[9] Ketteman

v Hansel Properties Ltd supra at

220

[10]

Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Brambles Holdings Ltd (1991) 28 FCR 451

at 456 (Sheppard

J)

[11] Managing

justice: a review of the federal civil justice system, supra at 393

[6.11]

[12] See

EI DuPont de Nemours & Co v Commissioner of Patents (1987) 16 FCR 423

at 424 (Sheppard

J)

[13] Beaumont

B, (2000) Managing litigation in the Federal Court IN Opeskin, Brian and

Wheeler, Fiona (eds). The Australian Federal

Judicial Sydney. Carlton South,

Vic, Melbourne University Press at

163

[14]

Federal Court of Australia Act s

53A(1)

[15]

Federal Court of Australia Act s 53A(1A)

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/FedJSchol/2004/10.html