James Cook University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

James Cook University Law Review |

|

An Aboriginal Perspective (from the Bench)

The Mayo Lecture for 2024

27 September 2024

Judge Nathan Jarro

I Acknowledgements

Budabai duru

ngya Bidjara/Ghungalou mardi

Nyila dana.

ngiya nhandhigu Wulgurukaba Bindal

ngudya ngiya gumba Wulgurukaba Bindal Country

maringa nhandhigu.

Translation:

Hello

I am a Bidjara/Ghungalou man.

Bidjara is on my Mother’s side. Ghungalou on my Father’s side.

Today I stand on the country of Wulgurukaba and Bindal and I pay my respects to (them and their Elders for their continuing connection to the lands, waterways and culture).

Stephen Urquhart, thank you very much for that kind introduction. Who would have thought that we meet again after so many years. For those of you don’t know, Stephen and I attended primary school together in the Brisbane suburb of Ashgrove. We lost contact with each other when we moved to high school.

I thank all of you (including those who have joined remotely) for your attendance this evening (even though it is a Friday night and I’m sure you have far more enjoyable things to do, especially tomorrow’s AFL grand final between the Lions and the Swans or tonight’s 7:50 NRL kick off for the Storm and Roosters preliminary final. I suspect had the Sharks not beaten the Cowboys last week, there would be less of you here tonight.

I am humbled by your attendance and having been bestowed the honour by James Cook University of delivering an annual lecture in tribute of Mrs Marylyn Mayo.

I have big shoes to fill, and I can tell you now that my imposter syndrome is well and truly kicking in, because these annual lectures, given their prominence in the JCU calendar, have been delivered by significant legal luminaries, including: Dr Bryan Keon-Cohen KC, a plethora of superior court justices, academics, former attorneys-general and other silks.

The organisers have extended a broad invitation to present on a topic of my choice, with the aim to inspire the next generation of law students.

Before doing so, it is important that we take a moment to reflect on the common thread which brings us here tonight and that is to recognise the person in whose honour this lecture is named.

Mrs Marylyn Mayo sadly passed away in 2002. Unfortunately, I did not have the privilege of meeting this wonderful lady, so I did a short internet search. Mrs Mayo has several lectures and scholarships named in her honour, one of which is this.

Established in 1991 by the JCU Law Students Society, the Mayo lecture pays homage to Mrs Mayo, JCU's foundational law staff member, and serves as a testament to her pioneering efforts in establishing the full law degree at JCU.

In 1960, the then Marylyn Mason graduated in Law and Arts from the University of Auckland. She was one of a small group of female law graduates. After being admitted as a solicitor and barrister in the Supreme Court of New Zealand, she worked in private practice until 1969 before moving to Townsville. It was not long after she began lecturing in law at the then Townsville University College (which later became James Cook University), that she met her husband Dr John Mayo, who was then a lecturer in economics. They married in 1970.

As a woman in a predominately male academic field, she was an inspirational mentor for many, especially women in North Queensland. In 1989, she realised her dream of establishing a full law degree at James Cook University and acted as Dean until 1990, after which she continued lecturing. She held the post of deputy Dean until 1993. In addition to lecturing, she published articles and presented at conferences. She retired from academic life in 1996.

Mrs Mayo was the Chair of the Townsville Hospital Ethics Committee and also served on various university committees, including the University Council itself, Academic Board and Promotions Committee.

Whilst a simple internet search can divulge a person’s achievements, I wanted to know more about this intriguing lady because, as I said, I never had the privilege, unfortunately, of meeting her. I wanted to know who Mrs Mayo was to the people who knew her. Therefore, if I may, can I just share with you some insights given by those people who knew her well:

(a) For instance, Justice Crowley met Mrs Mayo, when his Honour was then a first-year law student of this university. His Honour said that Mrs Mayo showed the students the methodology for case analysis using the acronym ‘FIRAC’ – Facts, Issues, Rules, Application and Conclusion – which his Honour said he still uses today. His Honour remembered fondly Mrs Mayo’s enthusiasm and the energetic instruction, saying that she was a formidable woman and a great teacher. Always clear and comprehensive in her tutelage. Always immaculately dressed and presented. And always projecting an energy and passion for the law that inspired her students.

(b) Mr Michael Drew of counsel (affectionately known as Swampy Drew), once leader of the Townsville Bar, who was a student of Mrs Mayo and tutored at JCU for a period of time, has said that Mrs Mayo could be described as vivacious, attractive in personality and presentation, ‘sharp as a tack’ and an artiste of the one word riposte to any brash male student (in the 1960s and 1970s) who vainly attempted to put her down in tutorials and lectures!! She was admired and loved by her students!

(c) She had an amazing poise, great confidence and a true understanding of the fundamental principles of the law, bringing alive to callow North Queensland youths the concept of the Rule of Law, the separate roles of common law rules and legislation, the legal philosophies of Montesque, Jeremy Bentham and JS Mill and the world-changing thought of Wilberforce. Mr Drew said that Mrs Mayo truly shone in explaining the development of the law of torts through its stages in developing the law of negligence, starting with the late 19th century English cases which culminated in the 1932 House of Lords decision in Donoghue v Stevenson.

(d) He said some have characterised Marylyn Mayo as being someone in the early vanguard of womens’ rights. She was so inclined, but only to the extent that she led by example. She felt that men and women should advance on their own merits and neither be held back, nor advanced on the sole basis of gender. She supported equality and never felt any discrimination toward herself.

As I said, this remarkable woman is the common thread which brings us here tonight and I am delighted to present this year’s annual lecture.

II Introduction

Before presenting my paper, can I share with you a little bit about my background into the law.

My family’s history is not that uncommon to many Aboriginal families in that my grandparents on both sides were removed from their traditional lands and relocated on someone else’s traditional lands.

My mother’s land is Bidjara which is the Carnarvon Gorge area in Central Queensland and Dad’s country essentially adjoins Bidjara – his people are Gangulu, which is in the Dawson Valley in Central Queensland (near Blackwater). My totems are the owl and the emu.

My father grew up in Woorabinda which is an Aboriginal community located a couple of hours south-west of Rockhampton. My mother is originally from Ayr but grew up in Inala (a suburb in Brisbane with a high Indigenous population) after my grandfather died shortly after his war service.

Dad’s dad, my grandfather, was removed from his birth lands of Springsure and relocated to Woorabinda. He, like my grandparents on my mother’s side, lived in a time when their lives were controlled by the State government, where the government used its legal power to remove them from their families and country.

My grandmother on my mother’s side was born in the Gorge at Carnarvon on a riverbank. She lived with her family in a humpy until the age of 3, when she and her four siblings (at the time) were transported on the back of a cattle truck some 8 hours away to Cherbourg which is near Murgon. Her schooling was in a tin shed on the Cherbourg mission. Her classes were segregated into light and darker skinned children because the lighter skinned kids were thought to be more able than the darker skinned ones.

The Superintendent ran the reserves, settlements and missions. The people lived on the missions, settlements and reserves as if they were in prison. Many were in a constant state of starvation. They were given only small quantities of rations and given their movement across the land was restricted, many people could not hunt or bring in the food on which their families traditionally lived.

The authorities did not educate my Nan after grade 4 but, according to her, she had a very happy childhood up until the age of 14, when a trooper knocked on the door at my great-grandparent’s place and said for her to get ready for the train in the morning because she’s going to work in Charleville. Of course, you can imagine the horror packing up and getting my grandmother ready, and she didn’t know what was happening. So, by the age of 14, she was directed to leave Cherbourg, still as a non-citizen of her country, and required to go out and work as a domestic. She worked in places such as Charleville in the 30s where she was required to work from dawn until night cleaning, cooking and caring for children. Her wages were controlled by the Chief Protector. She saw a pittance of what she earned. She never spoke of, and she wouldn’t speak about, the injustices that she received or the treatment that was meted out to her on those cattle stations.

Because she was under the control of the Chief Protector, neither she, nor my great-grandparents Grannie Holt and Grandfather Holt were given warning about where she would work. She had to get permission to return back to Cherbourg to see them. She even had to get permission to attend funerals or Christmases. Her permission to return was often declined (which at times caused her significant distress in missing family events).

My mum’s dad, whom I never met, was an only child. By contrast to my Nan, he had an idyllic childhood in Ayr, where his family somehow escaped the harsh Queensland government treatment of First Nations peoples.

He was Birri Gubba Juri, from North Queensland.

His father (my great-grandfather) was in the army in WW1 and my grandfather fought in WWII. They, like other Indigenous serviceman and women, fought for a country that discriminated against them.

He was a POW of the Japanese in Singapore and spent much of the war on the notorious Burma-Thailand Railway. He died from war-related illnesses shortly after his return from war and did not live to see the right to vote, which happened some 15 years after his return.

I know this information directly through my Nan on my mother’s side and my granddad on my father’s side. I was old enough (I’m talking when I was in my early 20s) to hear of their lived experiences. It was certainly a different, harsher and more punitive time, than the blissful life I have been lucky to receive.

My parents met in their late teens and married when they were 19. In fact, they celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary earlier this month. My father wanted to remain in Woorabinda; however, Mum didn’t want that. So, they settled in Brisbane together.

My parents produced three boys. We are Brisbane-born and bred. My parents gave us a private school education (without any government handouts) through a Catholic school in Brisbane. Whilst I am certainly what is known as an urbanised Murri, I can assure you that my brothers and I have strong family and cultural links to Rockhampton, Woorabinda, Cherbourg and Carnarvon. We know who we are and where we come from.

I have had a very good life (thanks to my parents); and that has stemmed from their decision to settle in Brisbane; not in Woorabinda. My life would have been so different if they had decided to remain in Woorabinda.

Now the fortunes that I have been blessed with have not passed to some of my cousins. Let me tell you about one. She is my age. She is already a grandmother. She is my dad’s niece and has lived in Woorabinda and Rockhampton. She lost her father to alcoholism when she was 14. She completed year 8 at Wadja Wadja State High School, which is the high school in Woorabinda. Her mother died a few years later. She has four children to four separate fathers, one of those children committed suicide; all were in the care of the Department of Child Safety from very young ages until they turned 18.

Our father’s brothers (with the exception of my father) and one of our aunties have all died of alcohol-related illnesses (all in their 40s).

My cousin has a small criminal history comprised of public nuisance offences and has spent time in prison. A number of my male cousins however have committed far more serious crimes than her, many of whom have done long stints in prison.

She and I are the same mob. We have had different opportunities which have led to clearly different lives. It just goes to show how a loving home with supportive parents who love, cloth, nurture and feed you, and give you an education can lead to different outcomes.

As I said, my cousin has been to prison. She is not the only one. Many of my mob have been and, indeed, some are currently in prison.

They are the ones who, even to this day, are discriminated against on a daily basis. People look down at them; people avoid them; society frowns at them.

Where many of my Indigenous brothers and sisters are today, is a product of their upbringing, and nobody in this audience needs to be told that historically relations between Indigenous Australians and various manifestations of the Law – whether it be Police, Governments, Courts, or indeed the legal profession altogether, have been far from ideal. Regrettably and all too frequently, Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders have not fared very well at all in these various interactions. It is something we all need to improve upon.

As I said, I have had a very good life (thanks to my parents); and that has stemmed from their decision to settle in Brisbane; not in Woorabinda. My life would have been so much different if they decided to remain in Woorabinda.

After completing high school, I went to QUT to study law. I graduated. My results were not stellar, but I was lucky enough to be an associate to the late Justice Moynihan AO. Among Justice Moynihan’s many achievements, the judge was involved in the Mabo findings of fact. My associateship with the judge was a fantastic experience because I saw a brilliant man in action, and met many lifelong friends, including one of my mentors, the late John Griffin KC. Like my judge, Griffo was a generous man.

I completed my articles at Gilshenan and Luton and practiced as a solicitor for 2 years in health litigation – acting for doctors and hospitals before going to the Bar at the age of 26. I squatted in Griffo’s chambers for close to 12 months. That gave me a good grounding to embark upon my career at the Bar. I had a civil practice at the Bar. I enjoyed being at the Bar – having the challenge of working for yourself and being in an environment where you had to rely on your skills and talent, otherwise you would not get work or make a living.

I spent 14 years at the Bar which I enjoyed until I expressed an interest to become a District Court judge.

For those of you who don’t know, the District Court deals with serious criminal offences such as rape, armed robbery and fraud. The court deals with civil disputes involving amounts between $150,000 and $750,000 and also hears appeals from the Magistrates Court.

III To-night’s Lecture

Tonight’s lecture is called ‘An Aboriginal perspective from the Bench’. It goes without saying that I feel extremely privileged to be a judge, and an Indigenous one at that. Since joining the bench, I have been fortunate to have witnessed three Indigenous superior court appointments, starting with Justice Crowley in May 2022, followed closely by Justice Michael Lundberg in WA in November 2022 and Justice Louise Taylor in the ACT in July 2023.

We are part of a growing cohort who share at least two common traits – we are Indigenous, and we occupy positions of influence. There are now, on my count, 18 Indigenous people who sit in various judicial posts across this country.

When each of us took an oath or affirmation to judicial office, we promised to do our jobs without fear, favour or affection. As judges, we are required to be independent and impartial.

So, I am not going to be controversial tonight (because that is best left to the lawyers, advocates, politicians and the media who perhaps do not have the same constraints as judges). I hope not to offend or give the impression of bias or preference towards one group of Australians. I just simply want to share with you some of my observations over the last few years, as a circuit judge to places like Townsville, Mount Isa, and, to a lesser extent, Cairns, where the Indigenous population is more obvious than that of South-East Queensland.

One memory that stayed with me longer than usual was when I circuited to Mt Isa last year. I expected to see many Indigenous defendants appear in court, given the observably higher population rate of Indigenous people. Given the population numbers, I also assumed there would be some Indigenous faces in the jury pool for empanelment purposes. I was surprised.

Four trials were conducted during the two-week circuit. The trials involved defendants who were charged with alcohol-related offending (whether that was choking, rapes or serious assaults). The four trials involved four separate complainants, all of whom were Indigenous females and three out of the four defendants tried were Indigenous.

Out of a jury pool of around 60, I observed no more than two people who I thought to be Indigenous. In the random jury selection process, no Indigenous person was empanelled.

I am not saying that to be critical or to have a black arm-band view about things, but I just wanted to give you some factual context about what I would like to talk about this evening.

So, for the first time in my judicial career, in those sittings in Mt Isa, there was an Indigenous complainant, an Indigenous defendant (save for the one non-Indigenous person tried), an Indigenous judge and a non-Indigenous jury, together with the lawyers.

Relevantly that meant in those criminal trials, non-Indigenous juries determined the guilt of the Indigenous defendants.

I invite you to pause for a moment and think about the Indigenous defendant, sitting in the dock, being tried before an all-white jury. Is that really reflective of the notion of being tried by your peers? Do you think these Indigenous defendants are receiving a fair trial? We all know justice is presumed to be blind, and, we are all equal before the law, but using this scenario even on this one occasion (if you already haven’t considered it before), and put yourself in the shoes of any one of those Aboriginal defendants and ask yourself whether you would be comfortable in having 12 people, who are non-Indigenous, determine your guilt or innocence. Of course, being a defendant on trial would be uncomfortable for any person, but the uncomfortableness, in having 12 complete strangers determine your fate, is unnecessarily heightened because of your Aboriginality.

As trial judges and lawyers, it is easy for us to forget about cases and move onto the next, but there are some cases that stay longer in your memory, and you can’t unsee certain things. That was one that I was unable to unsee.

Of course, an Indigenous person being tried before an all-white jury is not a novel concept. Indeed, challenges have been made about this in the past. For instance, in R v Buzzacott [2004] ACTSC 89; (2004) 154 ACTR 37, an Aboriginal applicant, who was charged with stealing a bronze coat of arms outside Parliament House for the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra, asserted, amongst other things, that he could only have a fair trial if the jury panel were to comprise Aboriginal Elders. The application was dismissed by Connolly J who observed that the right to trial by a jury of one’s peers does not mean that an accused person may demand that the jury panel be comprised solely of persons of a particular racial, ethnic, social or gender group. His Honour stated that it would be entirely inappropriate, and indeed unlawful, to make directions so as to ensure a particular racial or ethnic composition of the jury panel.

I am sure HH was right and, as I said earlier, I do not plan to be controversial or offend. So let’s flip the facts in Buzzacott and my Mt Isa trials.

Our country’s first Indigenous silk, Queensland born, Sydney based, Dr Tony McAvoy SC, was in Alice Springs in late 2022 when a white police officer was on trial for the murder of Kumanjayi Walker. In his foreword to a report which I intend on speaking about shortly, Dr McAvoy observed as follows:

Senior Constable Zachary Rolfe had been charged with the murder of a 19-year-old Aboriginal man in his home in the very remote Northern Territory community of Yuendumu. ...

That trial was conducted before a jury that did not include a single Aboriginal person. That fact attracted some media attention when the jury was sworn in and a lot more attention when a not guilty verdict was returned. For my own part, there can be no justification that permits a First Nations person in the Northern Territory to be tried before an all-white jury. First Nations people make up approximately one third of the Northern Territory population.

The analysis that occurred during and after the verdict in Rolfe turned to the Juries Act 1962 (NT) and the Juries Regulation 1983 (NT) which provides that jurors may only be drawn from the relevant jury district, and limited jury districts to the suburbs of Darwin and the Alice Springs, both areas in which Aboriginal people are grossly outnumbered by non-Aboriginal people.

There are many knots in the Australian justice system which must be untangled, and ensuring representation of Aboriginal people on the juries, and benches, as the arbiters of fact, is a large knot.

Like the trial in Rolfe, let’s move closer to where we are meeting tonight, and that involved the Queensland trial of Senior Sergeant Hurley who was charged with manslaughter and assault following the death of 36-year-old Indigenous man, Mulrunji Doomadgee in a police cell on 19 November 2004 at Palm Island. A coroner and an independent inquiry found that Hurley caused the death when, 45 minutes after his arrest, Mulrunji died with a cleaved liver, broken ribs, a ruptured portal vein and a haemorrhaging pancreas. The Palm Island community said they had little faith in the system when an all-white jury was empanelled. Their prediction was true when Hurley was, of course, acquitted.

The issue of Indigenous jury representation has been discussed by law reform bodies in the past. For example, in a 1986 Australian Law Reform Commission Report called ‘Recognition of Aboriginal Customary Laws’, it was noted:

The Commission has received no evidence to justify the conclusion that jury trials involving Aborigines are, in any way regular or recurring way, biased or otherwise unsatisfactory.

In the same report the Commission commented that to deny an Aboriginal person the right to trial by jury would be discriminatory. Where there was a risk of prejudice, an application could be made for a judge-alone trial or for a change in venue for the trial (which may itself affect the make-up of the jury).

Such was the case in Wotton v DPP (Qld) [2006] QDC 202 where Aboriginal man Mr Wotton had been charged with riotous damage and arson on Palm Island. He applied to have the trial venue changed from Townsville to Brisbane. One principal ground was that a survey conducted in Townsville showed that a large proportion of those surveyed had personally experienced anti-social behaviour involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons, almost all persons remembered the incident well, over a third remembered the identity of Mr Wotton and over a fifth regarded him as one of the persons criminally responsible for the damage and arson caused on the Island. The survey revealed some people would not put aside their prejudices against Mr Wotton, even if directed to do so by a judge. Approximately half indicated they were unsure or did not believe that they would be able to follow such a direction.

It was held by Skoien ACJ that the highly adverse publicity in Townsville had created a risk of prejudice to Mr Wotton, notwithstanding that a trial judge would give proper directions to the jury such that the trial be held in Brisbane.

The issue of Indigenous jury representation has gathered publicity in more recent times.

Last month, former Supreme Court judge, the Hon Roslyn Atkinson AO, when delivering a lecture to the Seldon Society on ‘Juries – Their Place in Democracy’, observed that ‘if juries are meant to be members of the community who are peers of the defendant, then it is critical that First Nations people are also fairly represented on juries.’ She said, ‘the legitimacy of our criminal justice system may be said to depend on it’.

She drew on her experiences presiding over criminal trials of Indigenous defendants at which none of their cultural peers was present on the jury. Unfortunately, Ms Atkinson’s observations, however, have been the subject of some critical commentary by certain sections of the community and media, but I consider she is well positioned to make comment as a retired judge with demonstrated credentials, and perhaps those who have criticised have misinterpreted or misunderstood what she really said.

As I said I do not intend to be controversial. I am merely observing that in my travels, particularly whilst doing circuit work, it got me thinking about Indigenous defendants being tried by all-white juries and why it is the case that there are not a lot of (if any) Indigenous jurors engaged in the jury process.

The principal source of what I am about to share with you is derived from the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration (’AIJA’) report titled ‘The Australian Jury in Black & White – Barriers to Indigenous Jury Representation’. The report was published in June 2023. It is my intention to discuss the report and to avoid proffering a personal view.

Drawn from multiple sources (including existing literature, law reform reports, statistics, case law and legislation), the report is comprehensive, and examines the role and experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within Australia’s jury system.

Relevantly for Queensland purposes, it considered, among other things, the 2011 Queensland Law Reform Commission report ‘A Review of Jury Selection’ where the Law Reform Commission interviewed serving jurors in Brisbane and found that no juror self-identified as Indigenous. Those findings were supported by ‘anecdotal feedback’ from the Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service (ATSILS) that there is ‘[n]ext to no Indigenous Australian representation on juries involving Indigenous defendants’.

Across Australia, all states and territories have their own individual jury legislation. In Queensland, juries are governed by the Jury Act 1995 (Qld), previously the Jury Act 1929.

Women became eligible for jury service 100 years ago. Queensland was the most progressive state in the country in permitting the inclusion of women, but the inclusion of women was initially met with significant resistance and was strongly opposed. For instance, male MPs questioned whether those women who were willing to serve were only ‘sticky-beaks’ and whether women jurors should be referred to as ‘juresses’. It is safe to say though that our jury system did not come crashing down simply by permitting females to participate in the jury process. Whilst women became eligible for jury service 100 years ago, it was not until the 1960s when Indigenous people were given the same right.

The lack of Indigenous Australians representation on juries is closely linked to Australia’s colonial roots. As acknowledged by Dr McAvoy SC, ‘First Nations disenfranchisement from the jury system is not new, nor is it disconnected from Australia’s colonial DNA’. The AIJA report observes:

There are undoubtedly pervasive social, economic, cultural and attitudinal reasons why Indigenous Australians are under-represented in civic and political institutions. Typically, these reasons are borne out of the impact of colonisation and marginalisation.[1]

Our colonial history has deeply impacted our Indigenous communities, forging long-standing policies of discrimination and exclusion which has, not surprisingly, informed Indigenous communities’ interactions with the legal system. Early laws explicitly barred Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from the colonial identity. It needs to be borne in mind that Indigenous Australians were specifically denied the right to vote in 1902 when the Commonwealth granted the right to vote to people ages 21 and over. It would not be for another 60 years until the right to vote was extended to Indigenous Australians in 1962, and mandatory enrolment was only introduced in 1983. That means that only 41 years ago did Indigenous Australians, once voting was made compulsory, become able to serve as jurors.

It is in the context of the disadvantages faced by Indigenous Australians within our colonial narrative that I would like to identify the principal reasons why Indigenous Australians are excluded from juries, despite past legal reforms which have slowly opened the doors to limited Indigenous participation.

There are many reasons why a significant number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples will not end up serving on a jury – there could be socio-economic factors, geographic and logistical challenges, legal and procedural obstacles, or indeed cultural or institutional barriers.

The AIJA Report has observed that their research ‘suggests that the system has (at worst) actively operated against the inclusion of Indigenous Australians on juries and (at best) failed to adapt to facilitate their inclusion’. It identified what it described as ‘pressure points’ that appear to most disadvantage Indigenous people, namely:

(a) non-inclusion on electoral and jury rolls;

(b) exclusion from jury rolls due to disqualification;

(c) peremptory challenges; and

(d) excusal and other forms of self-elimination.

I will speak briefly about each of these matters before highlighting potential models to improve participation amongst the Indigenous population.

IV Non-inclusion on the Electoral Roll and Jury Roll

To be included on the jury roll, potential jurors need to be on the electoral roll. It therefore follows that if you are not on the electoral roll, you will not be a potential juror. As such, non-enrolment on the electoral roll is a factor affecting Indigenous Australian participation in the eligible jury pool.

The Australian Electoral Commission has published Indigenous enrolment rates from June 2017. I am pleased to say the figures from Queensland are not bad. As at that date (being 30 June 2017), the estimated enrolment rate for Indigenous Queenslanders was sitting around 70%. By 30 June 2023, that figure has encouragingly increased to 95.3%. The data also reveals in broad terms that of the 3.6 million Queenslanders enrolled to vote, 150,000 are Murris (ie, Indigenous people from Queensland). So therefore 4% of the total pool.

There is a tad over 7,000 Murris (ie Indigenous people from Queensland) who are unenrolled; the numbers are small, but they are so crucial.

As I said, Queensland is in a better position than the other states and territories but remember the figures I have just mentioned are the people who are enrolled to vote. Being enrolled to vote does not necessarily equate to inclusion on the jury roll. Nonetheless it is trite to observe the importance of ensuring that potential jurors are correctly enrolled on electoral rolls as that will contribute towards improving eligibility status, irrespective of cultural background.

A Jury Districts

All states and territories are divided into what is referred to as jury districts.

It is the imposition of what is known as jury districts which impact predominantly on Indigenous Australians, including in Queensland, because jury districts form the basis of jury rolls. Remember what Dr McAvoy observed earlier when referencing the Rolfe trial:

The analysis that occurred during and after the verdict in Rolfe turned to the Juries Act 1962 (NT) and the Juries Regulation 1983 (NT) which provides that jurors may only be drawn from the relevant jury district, and limited jury districts to the suburbs of Darwin and the Alice Springs, both areas in which Aboriginal people are grossly outnumbered by non-Aboriginal people.

Let me give you a case illustration regarding jury districts. In an unreported 1973 decision of R v Gibson, a South Australian Supreme Court judge ruled that the sheriff had made no attempt to exclude Aboriginal persons who were qualified to serve as jurors when calling the jury. That was a case where the defendant, who was a member of the Pitjantjatjara community in South Australia, made a challenge that the jury had no Aboriginal members at all. The defendant called several Aboriginal persons who asserted that they never had been called for jury service, nor did they know of any Aboriginal person who had been called for jury service. Yet contrary evidence was given by the sheriff that Aboriginal persons had in fact been summonsed, which the judge preferred to accept and dismissed the application.

In Queensland, section 5 of the Jury Regulation 2017 provides for jury districts. Generally, jury districts fall within a 15-25 km radius of courthouses, where the court is constituted to sit. Here in Townsville, for example, the jury district falls within a 25km radius of the courthouse.

The point is that if you are not within, say, a 20km radius ‘at which the District Court is constituted and held’, your name (assuming you have passed the first hurdle and you are on the electoral roll) will not be included onto the jury roll. Therefore, as you can see, citizens who live beyond the jury district boundaries are not summonsed for jury service, and consequently are excluded from the jury roll.

You therefore might accept the proposition that for First Nation Australians, many of whom do not live in the CBD or live in remote regions outside of jury district boundaries, are excluded from jury service, causing under-representations on juries within their relevant district.

In Binge v Bennett (1989) 42 A Crim R 93, Justice Smart commented:

The lack of Aboriginals on both jury panels and juries is to be greatly regretted. The present system of making up jury panels does not of itself discriminate against Aboriginals. However, it is a system which, because of their education, lifestyle and attitudes, does not readily encompass them.

That was a case which concerned an application by Mr Binge and 15 other Indigenous people from Toomelah/Boggabilla to quash an extradition order imposed by a magistrate in the Local Court at Moree to return them to Goondiwindi to face a charge of riot said to have caused extensive damage, which followed from serious ill-treatment of an Aboriginal boy in Goondiwindi the previous day. The application came before a single judge in the Supreme Court in Sydney in late November 1987. The primary judge gave his decision, ordering that the applicants be returned to Queensland for trial. The decision was appealed. The NSW Court of Appeal upheld the appeal and ordered a rehearing before a different judge.

In the rehearing, the applicants claimed that it would be ‘unjust or oppressive’ for them to be returned to Queensland, on the ground, among other things, that the events giving rise to the charges had sparked extensive adverse press coverage in local, State and national newspapers. That publicity included strong adverse statements attributed to the Premier of Queensland and certain government ministers and much of it related to Aboriginal people. The statements attacked Aboriginals from New South Wales and views were expressed that the offenders should be made an example of and gaoled. Further, a local teacher detailed the racial prejudice within the community and said that white children would sometimes speak of their preferred weekend sport as ‘nigger hunting’ or a local Uniting Church Minister often heard young Goondiwindi men call out to Aboriginal girls who were shopping words to the effect, ‘There are the black shits’. The young girls moved on quickly and did not reply.

Justice Smart considered that the adverse publicity had been ‘so extensive and so virulent as to make a fair trial in Goondiwindi virtually impossible’ and that, in all of the circumstances, it would be ‘unjust and oppressive’ to return the Indigenous applicants to Queensland.[2] That matter took close to two years to conclude.

Another reason related to jury districts that affects numbers of Indigenous Australians on juries is that of non-response to jury summons. A non-response to a jury summons can occur for many reasons, including a change of address, non-delivery of the summons and from receipt but no response to the summons. While the report notes that it ‘do[es] not have figures on the rates of, or reasons for, non-responses to the jury summons’[3], it concluded that that non-response to summons is ‘an issue that has been identified as one that may specifically impact Indigenous Australians’. It recommended appropriate investigations be launched to consider this issue in more detail.

V Removal from Jury Rolls – Disqualification and Exclusions/Exemptions

Turning now to removal from jury rolls.

In Queensland under the Jury Act, jury composition is achieved by selecting jurors at random from those members of the community who are eligible to serve on juries.

Like other states and territories, and also federally, part of our system in Queensland involves the exclusion of various groups from the jury pool. The legislation provides for the removal of certain summonsed people from the selection jury process. For example, Governors, judicial officers, lawyers, people employed by the ODPP, Police Service etc).

A Exclusion Also Applies to Citizens with a Criminal History.

Whilst it is accepted that the exclusion of people with criminal histories reflects the view that juries should be impartial, it is this exclusionary category that affects Indigenous Australians most disproportionately.

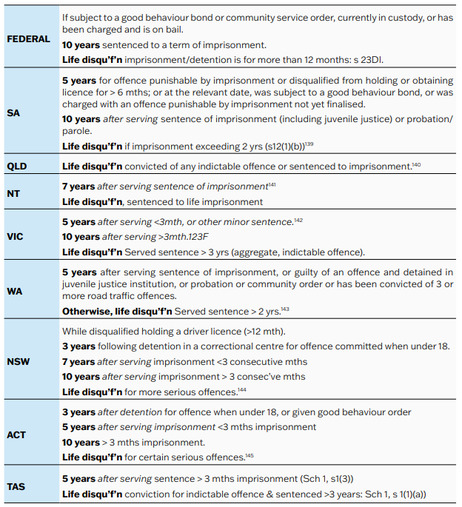

In Australia, typically disqualification from the jury rolls applies to a person ‘with a certain criminal history, either serving their sentence, or within a certain number of years of obtaining a criminal conviction.’[4] Jury disqualification based on criminal history applies in all Australian jurisdictions, but the legislation has little consistency across the states and territories. All jurisdictions, except Queensland, scale according to the seriousness of the criminal offence as measured by its sanction. For example, New South Wales provides for increments of 3 years, 7 years, 10 years and life disqualification.[5]

Source: Hunter J; Crittenden S, 2023, The Australian jury in black and white: Barriers to Indigenous Representation on juries, Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration Inc, Sydney, Australia, http://dx.doi.org/10.26190/unsworks/28690, page 24

Whilst all jurisdictions provide for life bans, Queensland stands out in that any person who has been convicted of an indictable offence or who has been sentenced to imprisonment is permanently disqualified from jury service. There is no provision for such a person to become eligible again after a certain period has elapsed after being convicted or completing the term of imprisonment; nor is a minimum sentence length required to trigger ineligibility.

The practical effect of this is that relatively minor breaches of the law can trigger the provision and thus result in a lifetime ban from jury participation. For example, ‘public order offences such as assaulting, resisting, or wilfully obstructing ‘a police officer while acting in the execution of the officer’s duty, or any person acting in aid of a police officer while so acting’’[6] are all indictable offences under the Criminal Code (Qld) and consequently all result in a life disqualification from the jury roll.

As a result of the higher rates of incarceration, First Nations Australians are statistically more likely than non-Indigenous Australians to be disqualified from jury participation for a major period of their adult life, or their entire adult life. In Queensland, it is for the entire adult life. A quick search of Indigenous Queensland prisoners for the financial year ended 30 June 2023, showed 10,226 persons.[7]

The 2011 QLRC Report criticised the current exclusionary jury provisions in Queensland. As noted in the AIJA Report, the QLRC has recommended ‘in recognition of the principles of offender rehabilitation and non-discrimination, and the desirability of maintaining representative juries, that the disqualification be limited to convictions made on indictment, excluding those determined summarily.’[8] In other words, minor offences should not be part of the exclusionary practice and that the Criminal Law (Rehabilitation of Offenders) Act 1986 (Qld) apply to criminal convictions, otherwise disqualifying a potential juror. These recommendations have not been adopted to date.

By way of case illustration in relation to criminal records, in R v Woods & Williams [2010] NTSC 69, two Indigenous defendants were charged with murder. Evidence was adduced that of the 350 people selected for jury service, 25% of the total were disqualified due to their criminal records. So, you can imagine how many Indigenous ones (if any) were left standing.

VI Elimination from the Jury: Challenges, Excusal and Self-Eliminations

Another key reason why Indigenous Australians do not end up serving on a jury is due to challenges, excusals and self-eliminations.

Part of the empanelment process involves the use of peremptory challenges both by defence and the Crown. The right to peremptory challenges is a right personal to the accused. Depending on the jurisdiction, the number of peremptory challenges per defendant varies. Peremptory challenges are different from a prosecution’s right to ‘stand by’.

Source: Hunter J; Crittenden S, 2023, The Australian jury in black and white: Barriers to Indigenous Representation on juries, Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration Inc, Sydney, Australia, http://dx.doi.org/10.26190/unsworks/28690, page 33

In Australia, Victoria, Western Australia, New South Wales and South Australia have the lowest number of peremptory challenges (limiting their availability to 3 per defendant), with other jurisdictions having 6 or 8 peremptory challenges per defendant, or more, subject to the number of defendants. In Queensland, prosecution and defence are each entitled to 8.

The AIJA Report discusses several cases that highlight the misuse of peremptory challenges against Indigenous Australians in the 21st century.

In the 2004 case of R v Badenoch, a defendant unsuccessfully ‘objected to the composition of the panel [from] which [the jury] was to be chosen as he, an Aboriginal Australian, had not observed anyone that he identified as an Indigenous person in it’ despite the trial being conducted in a location where it is ‘well known that many persons of Indigenous origin resided.’[9] It was in Mildura, Victoria. In dismissing the challenge to the array of a white jury, the court held that lack of Indigenous representation did not inhibit a fair trial for the applicant, and that selection based on ‘some ethnic or other discriminatory criteria’ would have ‘terrible consequences’ for fair trials.[10] The decision was upheld on appeal by the Victorian Court of Appeal.[11]

A similar challenge was raised in the 2010 Northern Territory case of R v Woods & William.[12] Like in Badenoch, the court held that ‘an accused person is not entitled to be tried by a jury that is racially balanced or comprised of the same proportion of people of a particular race, as occurs in the broader community from which the jury is selected’[13] and that ‘to impose some overriding requirement to the effect that a jury, once randomly selected in this way, has to be racially balanced or proportionate would be the antithesis of an impartially selected jury’.[14]

The case of Binge v Bennett, referred to earlier, is useful as it discussed the practice of prosecutors using their right to ‘stand by’ to ensure Aboriginal people were excluded from the jury.

In that case, a barrister called Colin Bennett of some 40 years standing, swore on affidavit in the 1988 interstate extradition proceeding that ‘in criminal trials that Crown Prosecutors regularly ‘stand by’ any Aboriginal person empanelled for jury service. This practice is so familiar to me that for years I have never exercised my right of objection against a prospective Aboriginal person as I can rely on the Crown practice of standing by any Aboriginal.’ He said: ‘during all the years of [his] practice in Queensland, I have seen only a small number of Aboriginal people empanelled for jury service and that with the one exception ... I have never seen an Aboriginal person selected to actually sit on a jury for a trial’. This was a Queensland barrister who conducted several hundred criminal trials in his time (and he only saw one Aboriginal juror).

The Report noted that in 1988 the then DPP, Des Sturgess, wrote into the Director’s Guidelines for prosecutors that: ‘The power to stand a prospective juror by is to be used only for the purpose of attempting to secure a fair trial. When deciding whether or not to stand a prospective juror by, racial or ethnic background is to be disregarded unless it is reasonably likely to cause the prospective juror to be prejudiced unfairly in favour of or against the defendant.’ The point was made in the report that these guidelines were only published to prosecutors.

Despite Binge v Bennett being heard some 35 years ago, a submission by ATSILS to the 2011 QLRC suggests that in recent times the prosecution’s practice of standing by Indigenous jurors has continued in Brisbane. Specifically, ATSILS provided the following anecdotal feedback from its regional offices, that there was:

[n]ext to no Indigenous Australian representation on juries involving Indigenous defendants. Our Townsville office indicated that since November 2008 — they have only had Indigenous Australian representation on juries three times (twice involving the same juror). Mount Isa — despite a relatively high local Indigenous Australian population — still very rare to have an Indigenous juror (at least for our clients). In Brisbane the few that are on the panel are invariably stood down by the Crown.[15]

Nevertheless, the QLRC supported the retention of peremptory challenges.

The New South Wales case of R v Smith[16] is a standout case in that it provides authority that the courts have the power to discharge the entire jury to ensure that a fair trial is achieved. The case involved the Crown Prosecutor exercising his peremptory right of challenge to exclude three Aboriginal Australians from the panel. In discharging the all-white jury, Judge Martin found that the lack of Aboriginal people on the jury could ‘suggest that justice is not being done’. In discharging the jury, the trial judge avoided criticising the actions of the Crown Prosecutor, stating that ‘the Crown Prosecutor, like the counsel for the accused, has an absolute right of challenge with a certain number of jurors and does not have to give any reason ... The fact remains that the Crown Prosecutor is a person well known to you as an honourable citizen, an honourable Crown Prosecutor and I am not in the slightest criticising his action nor impugning it in any way whatsoever.’

The case of Smith is notable as it has set a high bar for the type of overt racism against Indigenous defendants that is needed in order for the courts to uphold a successful challenge. When compared to case law involving the use of challenges by Indigenous defendants, Smith would appear to be on its own in that it differs from the accepted position of the courts that fairness in jury selection comes hand in hand with compliance with the legislated jury selection process, that is, in situations where an all-white jury has been empanelled in compliance with the legislated jury process and therefore the jury has been randomly selected, Australian courts are reluctant to discharge the jury panel as courts view the latter approach as a fair and just process.

VII Other Factors

There are also additional factors, the report has highlighted, that disproportionately affect Indigenous jury numbers, specifically that Indigenous people are, to a greater degree than the general population, impacted by structural disadvantage.[17] There are a range of social impediments that First Nation Australians face that conflict with their capacity to participate on juries (for example, disproportionate chronic health problems, greater caring responsibilities, sorry business and cultural constraints).

Regarding chronic health conditions, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2018-2019 revealed that 46% of Indigenous people ‘had at least one chronic health condition’.[18] This means that more than 4 in 10’ Indigenous Australians will suffer from poor health conditions.[19] A significant health condition which disproportionately affects Indigenous people is hearing loss.

The report contends that there is a likely nexus between the major health gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians and disproportionate jury participation.

The report also highlights that unpaid caring responsibilities disproportionately affect Indigenous Australians compared to non-Indigenous Australians. Indigenous Australians are twice as likely to provide unpaid care compared to non-Indigenous Australians.[20] The disproportionate caring responsibilities have been linked ‘to the greater prevalence of disability and chronic health conditions in these communities’.[21] Also associated with poorer health outcomes is the fact that Indigenous Australians are more likely to experience ‘sorry business’ and need to be excused from jury service.

Thirdly, the AIJA report quoted the then Victorian Attorney-General, Mr Robert Hulls, at his Opening Address in 2011 on Aboriginal Justice to support its contention that circumstances may operate to impact Indigenous representation to serve as jurors due to cultural constraints, community ties and/or cultural safety as follows:

On one occasion I was acting for an Aboriginal client in a civil matter about a car accident. We had an eye-witness to the accident ... Our witness was an Aboriginal man from the Camooweal area. I spoke to him briefly before he went into court to give evidence explaining that he just had to tell the court what he saw when the accident happened. When he was called to give evidence he walked up to the witness box, saw all white faces looking at him, turned to the magistrate and said ‘I plead guilty, Sir’.

The reality is that there is still a perception amongst Indigenous people that the current jury system is not a culturally safe place for them and according to the report, ‘broad anecdotal evidence’ outlines a sense of fear, alienation and distrust of the criminal justice system amongst Indigenous Australians.[22] It seems to me that to address the sense of fear, alienation and distrust, then community engagement is vital and effort needs to be given to target recruitment drives within communities, with the leaders and organisations of those communities having a pivotal role in advocating for greater representation and supporting potential jurors. After all, Indigenous leaders and organisations can help bridge the gap between Indigenous communities and the legal system.

VII What Have Overseas Jurisdictions Done or Proposed?

Australia’s Indigenous peoples’ participation is not unique given the experiences and concerns expressed in Canada, New Zealand and Argentina. The report observed that:

The sense of alienation reported in the press from Kumanjayi’s family is similarly described in New Zealand. For example, the 2001 NZLC observed that ‘many Maori feel strongly that juries are not representative of Maori society, [which] ... contributes to a general feeling of alienation from the criminal justice system.

In Canada, in 2013, the Canadian Ontario government commissioned the Iacobucci Report, First Nations Representation on Ontario Juries. Iacobucci was a former Canadian Supreme Court judge. The report included 17 recommendations ‘relating to the creation of the jury roll, increasing opportunities for Indigenous input into government decision-making and increasing services for Indigenous people involved in the justice system’.[23] One of these recommendations included the abolishment of peremptory challenges.

Five years later in the 2018 Canadian case of R v Stanley[24] was heard. The case of Stanley involved a white defendant being acquitted of the homicide of an Indigenous man by an all-white jury. The case also involved defence challenging all five jurors of Indigenous appearance during the empanelment process which resulted in public outcry from the use of the peremptory challenges calling for reform.

Very soon after this case was handed down, the Debwewin Jury Review Implementation Committee, made up of ‘Indigenous leaders and government and judicial representatives,’ was charged with advising the Ontario government on the earlier 2013 Iacobucci report. The Committee published the ‘Barriers to Accessing Justice: Legal Representation of Indigenous People within Ontario’ (‘Debwewin’s Report’) in April 2018 which ‘reviewed and responded to barriers described in reports, academic articles, and in presentations and community engagement, and Elders’ Forums.’[25]

The Debwewin’s Report suggested a list of initiatives aimed at increasing Indigenous people’s jury representation which are outlined in the AIJA report. In the interest of time, I will not read out all of the recommendations, but some of them include:

• Various recommendations regarding the use of peremptory challenges. These recommendations have been overtaken by Canada’s abolition of peremptory challenges.

• Reviewing criminal history exclusions to reduce ineligibility timelines and to develop an automatic pardon program for First Nations people to have convictions removed 5 years after the completion of a sentence, possibly limited to non-indictable offences, and possibly recognising the authority of an Indigenous community to offer its members amnesty, the equivalent of a pardon.

• Establishing First Nations liaison officers, ideally from local communities, who are tasked with consulting First Nations reserves on juries and on justice issues to reduce hesitancy to respond to juror summonses and improve Indigenous representation on juries by better informing Indigenous people of justice system processes.

• Creating a focus on including and educating Indigenous youth.

• Supporting the training of more Indigenous lawyers.

The Debwewin’s report also went further and suggested reforms aimed at addressing the broader underlying issue shared by countries such as Canada and Australia, that being ‘Indigenous people’s alienation from the justice system.’[26]

The AIJA detailed three overseas jury models for what it described as ‘affirmative action’, that is whether it is:

(a) A proportionate model requiring that the jury reflect the respective proportion of both majority and minority groups in the general population.

A social science model effectively of three minorities (which is said to reduce the impact of racially homogenous juries).

(c) A jury de medietate linguae concerned with the inclusion of aliens (the concepts of aliens was based on the Medieval system permitting the inclusion of Jews, or others to be part of the jury, in other words mixed juries) (ie, half/ half). It has more recently been adopted in Argentina, New Zealand, Barbados, North Borneo as a mechanism to ensure Indigenous jury representation.

All these models advocate for minority participation on juries and the report supports a consideration of these models.

I should say it is merely a consideration of these models; it is not a hard proposal or recommendation to adopt all or any of them. Perhaps that is why recent media commentary (and associated comments) have been critical of the report. There is no harm in making further inquiries, research and investigations about this important issue. The impetus for the recommendation is, on my understanding, due to the limited data on the actual, ‘on ground’ results of Indigenous participation derived from these models. There is no harm in exploring these issues.

The report merely encourages further discussion around ways to improve Indigenous engagement, because it does emphasise the need for reform in the jury system to enhance Indigenous representation.

The concluding remarks contained within the report argue that the disenfranchisement and the inertia that it permits, despite previous recommendations by Australian law reform bodies directed at improving First Nations’ Australians representation on jury lists, panels and juries, is not acceptable. In relation to inclusiveness and responsiveness, the report concluded that the jury system fails to make a genuine attempt to provide for all Indigenous Australians. In relation to shifting the inertia and embarking on reform through a process that is Indigenous led and collaborative, it has suggested that an appropriately resourced and national focus was highly desirable because it is an issue of national importance.

That explains why a roundtable discussion was recently convened by the AIJA in June 2024 to consider opportunities to address the issues identified in the report. The roundtable included Indigenous and non-Indigenous stakeholders from the judiciary, court administration, policy, practice, advocacy and academia.

It was well-attended and provided a forum for meaningful exchange on the complex and interwoven issues underpinning barriers to Indigenous representation on juries across different Australian states and territories. Two broad topic areas were identified at the roundtable as requiring further consultation and research, namely:

(a) Legal Issues, including differences in approach, rationale and criteria by various Australian states and territories to jury disqualification, peremptory challenges and the availability of judge-alone trials;

(b) Social-cultural issues, such as cultural safety issues regarding the criminal justice system, and jury summons (e.g. language/service difficulties, juror travel, and/or not being on the electoral roll).

The AIJA is currently pursuing a number of activities, including:

• Extracting and gathering data on matters such as peremptory challenges and disqualifications.

• Setting up a community consultation pilot study which will consult with Indigenous communities about their priorities to direct further work in this area.

• Expressions of interest from law, humanities and social sciences academics to conduct further research on legal issues identified at the roundtable.

As I indicated at the outset, I thought the report was extensive, extremely thorough, well researched and comprehensive. I commend those who are drawn to this topic of significance.

VIII Conclusion

I conclude by saying my main goal in delivering tonight’s lecture was to highlight the findings of the AIJA report. Remaining impartial as I have tried to be throughout tonight’s lecture and putting aside any feelings of fear, favour or affection, what is clear is there is more work (whether with investigations, conversations and research) to address what has been described as a chronic under-representation of Indigenous jurors.

Thank you all very much for your attendance this evening, especially in honour of Mrs Marylyn Mayo.

[1] Report, Page 11.

[2] See Aboriginal Bench Book for Western Australian Courts, 2nd ed, Stephanie Fryer-Smith 2008.

[3] Report, page 20.

[4] Report, 21.

[5] Report, 28.

[6] Report, 27.

[7] https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/prisoners-australia/2023#aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-prisoners.

[8] Report, 30.

[9] R v Badenoch [2004] VSCA 95 at [66].

[10] Ibid at [66] and [68].

[11] Ibid.

[13] [58].

[14] [59].

[15] https://www.qlrc.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/372544/r68.pdf, page 357.

[16] R v Smith (Unreported, District Court of New South Wales, Martin J, 19 October 1981).

[17] Report, page 45.

[18] ABS, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018-19, n 280, Report page 46.

[19] Report, page 45.

[20] Report, page 47.

[21] Report, page 47.

[22] Report, page 48.

[23] Report, page 51.

[25] Report, page 51.

[26] Report, page 52.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JCULawRw/2024/2.html