|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Law, Technology and Humans |

Introduction

Symposium: Drawing the Human: Law, Comics, Justice

Timothy D. Peters

University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

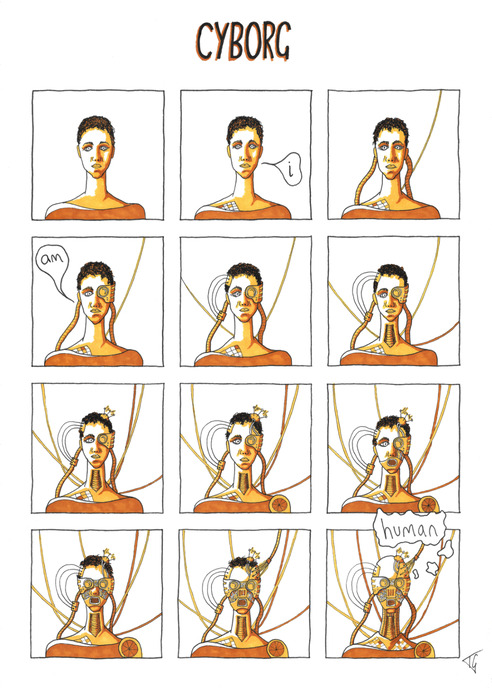

What does it mean to be human today in our globalised, technologised and hypermediated world? How do our modes of cultural representation relate to, affect and effect the role of being human? This special issue of Law, Technology and Humans seeks to explore the form of the comic as one means to address these questions. Comics are a means of cultural representation and discourse that not only reflect but refract — through their deployment of word and image, of grid and gutter, of both visual and textual mediation — the very means of human interaction and intersubjectivity. Arising out of the 2019 Graphic Justice Research Alliance conference, hosted by the School of Law and Criminology (now the School of Law and Society) at the University of the Sunshine Coast, the papers collected here examine not only the way in which comics and graphic art present narratives of law and justice, or representations of human rights and their abuses, but also the way in which comics in their form and multimodality call into question the law’s drawing of the boundaries of the human as it is challenged by its relation to the non-human, the environment and technology. Such concerns are important today, not just because of the techno-mediation of human interactions and intersubjectivity — which open potential for both the enhancement as well as the sidelining of the human by technology, as represented in both the header image above by Dr Ashley Pearson and “Cyborg” by Dr Thomas Giddens in Figure 1 — but also because of the situatedness, complicity and responsibility of the human within its broader environment.

Comics and law are intertwined, not only through the stories that appear in the comics medium, but in the comics form — multifaceted and layered, capturing the human in its imagery and imaginary, with the viewer becoming an active participant in the construction and reading of the image.[1] Law, like comics, is what Giddens refers to as a “multiframe,” dividing and regulating the world into certain frames to be read, understood and inhabited.[2] Law is both subjected to interpretation and creates the subjects who “read” it, and are in turn subjectivised by it. Just as the comics artist uses a combination of lines, colour, shading, perspective, framing, grading, and grids to articulate the human, and facilitate its interpretive ambiguity and complexity, law creates and constitutes the human through the harmonisation of the aesthetics, discourse, custom and image of sovereign authority. Both law and comics draw the human, determine its bounds, while representing and operating through an intersubjective relationality.

The significance of the human as a site of mediation of the law’s image can be observed in terms of the court sketch artist.[3] Here, we find law’s particular acceptance of the drawn image, over the photographic — with many jurisdictions still limiting the recording, broadcasting or photographing of trial proceedings. The intersubjective experience of the drawn image becomes, therefore, not simply a record of what occurs within this juridically determined space, but an aesthetic representation of the human confronted by legality and subjected to its judgment. As Anita Lam has noted, the artist’s reproduction of the law involves not simply a photo-realistic capturing, but rather “the reciprocal relation of touch” which “has the ability to reconfigure surfaces in order to make itself felt by others.”[4] As Lam notes, “[w]hen law works through the bodies of courtroom artists, it ceases to be a transcendental, abstract entity, and is instead re-made as a material place that shapes and is shaped by bodily sensations.” [5] This process leaves a trace of law on the body of the artist — the process of representing or drawing the law, reflexively takes on and bears witness to the law’s drawing of the human. In doing so, this form of graphic art opens up the possibility of a sense of law beyond the human, and one that is reflected in the particular intersubjective form of drawing.

Law has a long history in constituting and drawing the human. From Roman law’s mask of legal personhood, to the medieval political theology of a corporate, sovereign person, through to our modern conception of the subject of human rights, law has been central to the drawing of the boundaries of a particular legal subject.[6] Yet, current political, economic, technological, biomedical, and environmental conditions cast doubt on the nature of this legal subject and raise questions about law’s continued ability to maintain a role in drawing the human.[7] Significant here is the very image of humanity that we find in law — whether as an autonomous and rational bearer of rights and responsibilities, a figure of agency, guilt and culpability or a contracting and property-owning subject. It is to a questioning of these images that the papers in this collection turn. For law functions through its images — both in terms of the physical representations of law and sovereignty that call it into being, as well as the legal imaginary (the way we think structure, authority, rights, regulation and legality) that constitutes its meaning.[8]

It is in this sense that a turn to the image — and here to particular types of images: comics and graphic art — can bring into question law’s vision and image of the human, drawing our attention to the ways of seeing that structure our ideas of law and the human, but also providing ways of envisioning it anew. At one level, the traditional focus on the abstraction of the comics image would seem to simplify and universalise our sense of the image of the human. And yet, at the same time, the drawn image’s own complexity involves a particular interpellation of the viewer-subject — an interpellation that always functions through a combination of presence and absence: “both the absence of the representing subject and of the represented object,” but a physical presence which is presented to the viewer — an image that we see.[9] It is by paying attention to the way in which images function and their oscillation between presence and absence that we can gain a greater sense of the depth of the question of what it means to be human, and the coalescing questions of responsibility that go along with it.[10] It is to such questions that the papers in this special issue turn, unpacking the way in which the comics form reproduces and critiques the image of law, undermines the human–nature divide and enables a way of alternative envisioning of the entanglement of law, the human and our world.

Figure 1. Giddens, Cyborg, 2019. Used with Permission

Sonja Schillings opens the issue with a critical analysis of the “institutional fantasies that line up around the notion of a human–nature divide.” Through analysis of a German satirical cartoon by Chlodwig Poth — and, in particular, its playful disjunction between word and image — Schillings outlines the way in which humans encompass metaphorical and non-metaphorical forms of absorption. The dichotomous split between human and nature that is fundamental to the Western tradition of property is here conceived as a form of bodily absorption, in which the human “metaphorically expand[s] his [sic!] body through property, so that he can no longer be separated from everything he owns and represents.” At the same time, humans are “part of a global nature that consistently absorbs pollution, and that is already collectively affected by the bodily transformations that the absorption of non-metaphorical pollution brings.” The metaphorical form of absorption that frames our social and legal institutions struggles to deal with the non-metaphorical absorption of pollution and radiation that occurs across both human and non-human bodies. Schillings, therefore, turns to superhero comics as a genre that focuses explicitly on the bodily absorption of radiation as providing a means for thinking beyond the dichotomous human–nature divide. With a critical reading of one of Osamo Tezuka’s acclaimed Astro Boy comics, she notes how the comic “connects human life with all other planetary life” but also renders the “classic human–nature divide’s central understanding of absorption as consumption as an inherently harmful and hostile practice.” The theme of absorption can, therefore, be revised in terms of its “foundation of the human condition within the world.” It is the comic’s tension between text and image that enables different thinking about philosophy, law and politics.

Leah Henderson continues the concern with human exceptionalism by focusing on the technological post-human in her interrogation of the epic literary comic Vision: Director’s Cut by Tom King and Gabriel Herandez Walta. Whereas Tezuka presents an underlying vision of the interconnectedness of all life, both organic and artificial, King and Hernandez Walta point to the institutional and ideological splits that fail to recognise such a vision. While at one level, as Henderson notes, Vision: Director’s Cut “seems to argue that any human-like A[rtificial] I[ntelligence] created ought to become subject to inalienable human rights, including the right to human dignity and equality,” it also critically unpacks the monstrosity of the human, with its fear of difference and the “other” and the attempt to re-embed and affirm dividing lines, both within humanity and between human and non-human. That is, the push toward a “universal” notion of human rights, in itself, encompasses a form of human exceptionalism and a distinguishing of the “human” from the “other” — the “protected” human subject, from the non-human. By tracing the literary connections of King and Hernandez Walta’s work to both Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, Henderson demonstrates a two-tiered argument: first, questioning the morality of creating artificial beings without granting them rights; and second, that it is not artificial life that is monstrous, but the all-too-human tendency toward abusive treatment of the other and outsider. Working through the questions of what makes a subject human and, therefore, a subject of human rights (sentience, vulnerability or perhaps a desire for vengeance), Henderson also points to the need for responsibility to the created non-human other.

Thomas Giddens takes up the question of the institutional aspect of the legal subject in a psychoanalytic legal reading of Joshua W. Cotter’s Nod Away. He elaborates the way in which the institutional nature of law is founded on, and responds to, a sense of chaos or the abyss — a point that is visualised by Cotter, who presents the institutional form of a corporatised and bureaucratic space station literally floating in the abyss of space. Drawing upon the legal psychoanalysis of Pierre Legendre, Giddens demonstrates law’s founding myth of the legal subject: “to be a legal subject is to be held in a nest of institutional forms amidst an unending sea of absence.” Whereas Schillings turns to the superhero comic as a mode of thinking that turns away from the metaphorical absorptive capacities of the law, and Henderson critiques the human exceptionalism of human rights, Giddens focuses on the very institutional capacities of law — the legal subject is that which is screened, separated and protected from the abyss. The very comics form that he analyses itself features in this institutional fashion, reflecting the way in which appearance “marks the limits of the normative order.” As Giddens notes, drawing upon Legendre, “[t]o be perceptible is to be within law’s jurisdiction.” Law, however, is contingent upon a normative division between presence and absence, what is permitted as allowable speech and authorised action, and the form in which the apparatus of personhood can take. Giddens turns to a mode of “horrific jurisprudence” as a means not so much to simply map the contours of the suppression of the monsters that lie beyond law’s form, but rather as “an acknowledgement of the contingency of law’s form and of form itself, of the structural emplacement of instituted materials within an infinite or abyssal context upon which they rely.” If law “imagines a horrifying beyond in order to keep the individual comfortably subjectivised, nodding away in its nest of forms,” a horrific jurisprudence recognises the transcendence of law’s structures and provides a “reflective access to law’s founding illusion, opening its institutional form to an immanent and radical potential to be otherwise.”

If Giddens focuses on the institutional aspects of law as a screen that keeps the individual subjectivated, then Neal Curtis turns to a critique of the authority of law as transcendence. He situates this in terms of Franz Kafka’s classic short story Before the Law, arguing that with the human desire for the illimitable, we find not only a vision of a transcendent Good, but also a dark shadow — the monsters to be defeated in the defence of the Good (which, as Giddens notes, are those presumed by law’s relation to chaos or the abyss). Such monstrous evil to be defeated is a common trope of superhero comics. Curtis focuses, here, on The Hulk as exemplary not simply of a monstrous other, but rather of the monstrous human desire for limitless power. The Hulk is, therefore, both Prometheus and Frankenstein’s monster, encompassing the paradoxical desire for humanity alongside the desire to exceed it and to claim what is divine. Curtis analyses Al Ewing’s recent The Immortal Hulk as providing a meditation both on what is dangerous about the desire for limitlessness, as well as a critical response to such a desire. For Curtis — extending his existing work on superheroes and sovereignty — The Hulk’s destructive and limitless power reflects the notion of sovereignty as pure self-relation. Ewing’s run, in particular, depicts The Hulk as encompassing a desire for sovereignty and autonomy — not only to transcend limits but to “exist without relation: the desire to be absolute.” The result is not, however, the divine, “the perfect One of self-creation but the chaotic Nought of destruction and oblivion.” The way out, according to Curtis’s reading of Ewing, is not through creation or a transcendent pursuit of the Law, but rather in terms of “the mundane realm of the social.” That is, Curtis emphasises not the desire for a transcendent Law backed by illimitable sovereignty, but rather the very social and mundane law and “the place it secures for us, and the responsibilities it demands from us.” Such can be observed not so much in “the Immortal Hulk,” the figure who survives to the end of the age as the strongest and who desires to be left alone, but rather in terms of the “collective of personalities within The Hulk” and the others with whom he relates who temper his tendency toward destructiveness. This is a vision of law rather than Law, the mundane workings of the social, rather than the transcendence of sovereignty: a politics where “the mundane workings of the law protects and facilitates the association of otherwise incomplete beings in what we call society.” Curtis argues, therefore, that “the law can only do good when it facilitates and protects this incompleteness” of the human subject and society.

This turn to the social, relationality and incompleteness as a counterpoint to sovereign ipseity and the autonomous subject is taken a step further in Theresa Ashford’s contribution with Curtis, which applies the fundamental relational ontology of Actor-network theory (ANT) to comics. Ashford and Curtis take this innovative and ground-breaking methodological step for comics studies by deploying ANT and Aristotelian virtue ethics to “think with/of Wonder Woman as an assemblage of human and nonhuman actors clustered on a page.” The deployment of ANT’s relationality goes beyond simply a sense of the sociality of the human, to its entanglement and interaction with, and production by, both other human and non-human actants. Thinking comics from this perspective takes into account both the hybrid representational and multimodal aspects of the comics form (the interactions of frame, text, line, colour, ink and other marks) and the co-creation that goes into its production as a result of “complex networks of writers, artists, trees, comic fans, ink, publishing machines, long nights, comic histories, copyright laws, distribution lines, moral codes, and evolving cultural contexts.” Applying this approach to Wonder Woman and, in particular, George Pérez’s Destiny Calling, Ashford and Curtis challenge the normative readings of Wonder Woman as a form of female objectification, arguing that she instead — as an assemblage of strength, femininity, vice, pleasure, good and evil — performs a form of Aristotelian “complete virtue” as justice. Working through examples of Wonder Woman’s strength and persistence but also diplomatic humility, they argue that she presents a form of justice that is not achieved despite her adornments — swimsuit, tiara, bracelets, boots and lasso — but because of them. This form of reading comics as an assemblage provides new ways of envisioning the nature of justice and its relation to the human and non-human.

Where Ashford and Curtis analyse Wonder Woman as an assemblage, Timothy D. Peters turns to the superhero as image and situates superhero comics within the genealogy of the law of images. Taking up a reading of the blind superhero Daredevil as a legal emblem — reflecting, in particular, the emblematic figure of “blind justice,” Justitia — he focuses on both the superhero’s relation to the political theology of sovereignty and to the modern biopolitics of personhood. Through a critical reading of Charles Soule’s run on Daredevil, in particular the narrative arc “Supreme,” Peters analyses the superhero’s dual identity and its significance for law. The superhero’s deployment of a “brand” or “image” — functioning through visual paraphernalia, such as the mask, cape, costume and insignia — reflects a form of the political theology of sovereignty. This is because the superhero, like the sovereign, only ever is their image — the transcendent authority that Curtis critiques is, here, a projection that can only ever be seen in its image. At the same time, as particularly modern bearers of justice, the superhero’s dual identity also reflects the biopolitical split of personhood between a sense of legal and social recognition (the mask or costume that is seen) and the biological human body. In Soule’s take on Daredevil, the law’s relation to, and ability to “see” and acknowledge, the superhero’s projected identity (their mask as an image of institutional office) is put under legal scrutiny — Daredevil’s alter ego, Matt Murdock, takes a case to the US Supreme Court arguing that superheroes are their image and, therefore, do not need to reveal their secret identity. What we find, therefore, is a depiction of the legal apparatus of personhood as a legal emblem — a making of the human visible to law. Yet, the significance of Soule’s run, for Peters, is the way in which such legal emblems can be re-signified, with their meaning crossing, as Schillings points to, the metaphorical and non-metaphorical institutions of law and the human.

This returns us to the question of law’s drawing of the human, which functions not simply in terms of the production of the legal subject, the human caught within law, but the way in which modern law is itself an image produced in its perception and envisioning by humanity. What the papers in this special issue point to is that the questioning of the law’s ability to draw the human today is not simply a response to the challenges of what it means for us to be human, but how to re-envision law as something that is more than human — a law that is something more than simply a human construct, a will of a sovereign “People,” or an institutional form as limit. Rather, it is to see law as something that extends beyond the human but which we participate in — a connectedness or entanglement of the human with the non-human, technology with nature. The comics form — which, in itself, is always incomplete, requiring a form of intersubjective participation, a production of multiple and countervailing meanings, as the papers herein show — provides one way of progressing such a conception of law.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all the contributors for their willingness to participate first in the Graphic Justice Conference, “Drawing the Human” in 2019 and second in this special issue. They have produced exceptional work with good humour throughout a difficult period. Thanks also to Kieran Tranter for his willingness to publish the special issue, and his excellent editorial advice and support. I would like to acknowledge both the School of Law and Criminology (now the School of Law and Society), along with the School of Creative Industries (now the School of Business and Creative Industries) at the University of the Sunshine Coast for their support in hosting the Graphic Justice Conference — and, in particular, Professor Jay Sanderson, for his encouragement of the project. Finally, deep appreciation to Ashley Pearson and especially Dale Mitchell for their tremendous work in organising and co-hosting the event with me, their conversations and contributions that led to the development of the themes described in this introduction, and for their permission to use the conference’s header image (art by Ashley Pearson, design by Dale Mitchell) as part of the special issue.

Bibliography

Crawley, Karen and Timothy D. Peters. “Introduction: ‘Representational Legality’.” In Envisioning Legality: Law, Culture and Representation, edited by Timothy D. Peters and Karen Crawley, 1–17. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018.

Esposito, Roberto. “The Dispositif of the Person.” Law, Culture and the Humanities 8 (2012): 17–30.

Giddens, Thomas. On Comics and Legal Aesthetics: Multimodality and the Haunted Mask of Knowing. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018.

Grennan, Simon. A Theory of Narrative Drawing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Lam, Anita. “Artistic Flash: Sketching the Courtroom Trial.” In Synesthetic Legalities: Sensory Dimensions of Law and Jurisprudence, edited by Sarah Marusek, 130–146. London: Routledge, 2017.

Leeuw, Marc de and Sonja van Wichelen, eds. Personhood in the Age of Biolegality: Brave New Law. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Manderson, Desmond. Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Mussawir, Edward and Connal Parsley. “The Law of Persons Today: At the Margins of Jurisprudence.” Law and Humanities 11, no. 1 (2017): 44–63.

Manderson, Desmond. Danse Macabre: Temporalities of Law in the Visual Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Mussawir, Edward, and Connal Parsley. "The Law of Persons Today: At the Margins of Jurisprudence." Law and Humanities 11, no. 1 (2017): 44-63.

[1] On the nature of comics form and law, see Giddens On Comics. On the embodied, intersubjective nature of the comics form, see Grennan, Theory of Narrative Drawing.

[2] Giddens, On Comics, 23.

[3] I owe this example to Dale Mitchell.

[4] Lam, “Artistic Flash,” 140 and 144.

[5] Lam, “Artistic Flash,” 144.

[6] See, for example, Esposito, “Dispositif of the Person,”; Mussawir, “Law of Persons Today.”

[7] See, for example, de Leeuw, Personhood in the Age of Biolegality. Connal Parsley and Maria Drakopolou’s recently launched AHRC Law and the Human Network seeks to explore these ideas in particular, and the contemporary role of law in defining the human: https://research.kent.ac.uk/law-and-the-human-network/

[8] Crawley, “Representational Legality.”

[9] Manderson, Danse Macabre, 17.

[10] On this notion of responsibility and images, see, in general, Manderson, Danse Macabre, and in particular Chapter 4 on J. M. W. Turner’s 1840 painting The Slaver Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming on).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LawTechHum/2020/20.html