Legal Education Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal Education Review |

|

THE DAY IN COURT: LEGAL EDUCATION AS SOCIOLEGAL

RESEARCH PRACTICE IN THE FORM OF AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY

KLAUS A ZIEGERT*

SOCIOLOGY OF LAW AND LEGAL EDUCATION

According to Eugen Ehrlich, one of the acknowledged

predecessors of modern sociology of law at the turn of this century, the most

important virtue of the accomplished lawyer was to be a “sharp eye for the

essence of the societal processes in the present,

a high sensitivity for the

needs of today and a relationship to the historical fact in

law”.l He contrasted this with the proverbial

sharp wit of a lawyer which he considered to be “one of the most fruitless

of the gifts

of human intellect”.2 There cannot

be any doubt that Ehrlich had a lawyer in mind who was an expert on context

rather than on mindless detail. However,

the target of Ehrlich’s attack

was not lawyers as such, but the ossified institutions which produced them.

Sociology of law

as a new, and as Ehrlich postulated, scientific approach to

legal practice had to change those institutions and their kind of legal

education.3

Today, nearly at the end of the century

which saw the unfolding of sociology of law, we can confidently say that neither

the lawyers

nor the institutions which produce them have changed all that much.

As far as there was change in legal education, it owes very little

to sociology

of law and a lot to how legal education has always

operated.4 There have been the perennial curriculum

reviews and reforms; new courses and new legally relevant assessments of context

have been

introduced in law schools; new confrontations with different theory

and critical analysis have entered the old scene. But it is highly

doubtful

whether all of this has had the fundamental emancipative effect which Ehrlich

had in mind. And it remains doubtful, and

certainly institutionally irrelevant,

why lawyers would need a sharp eye for the essence of societal process, once one

goes beyond

the rhetoric of curriculum reform.

A sociological observation of

legal education leads to the rather trivial conclusion that legal education does

not change much as

long as legal systems do not change much and that legal

systems do not change much as long as they are designed to operate legal

decisions normatively.5 This conclusion is less trivial

for those who, like Ehrlich, want to overcome the extremely powerful definition

of legal education

by legal practice, a practice which cannot be explained by

legal theory other than by reference to further legal practice. For the

purpose

of legal theory, law is defined as what statutes, judges and administrators say.

Those academic lawyers who feel the limitations

of reproducing legal education

as a theory of legal practice are caught in a dilemma. They can observe and

teach law from a position

outside legal practice and legal education, and with

reference to social or any other scientific theory. However, these references

are of little consequence to legal practice and they tend to become marginalised

in legal education. Alternatively, they can observe

and teach law from a

position within the legal system and with reference to legal theory and legal

practice. However, these references

are of little use to law students. They do

not explain the operation of law better than students get to know by

internalising legal

work practices while passing through law school. A result of

the law teachers dilemma is that the use of any other than legal theory

—

from the critical application of social theory by the European

Freirechtsschule and the American or Scandinavian Realists in the past to

the application of anti-institutional theory by the Critical Legal Studies

movement in the present — is either carved up in legally relevant titbits

or is dogmatically purified for consumption in law

school

classes.6 In neither case do social sciences, and least

of all sociology of law, perform a particularly emancipative job. It is much

more likely,

in each case, that they are subsumed under the requirements of

legal practice to be practical, to give immediate answers and not

to ask too

many awkward questions.

One way out of the dilemma of law teachers and

faculties is to conduct legal education as legal studies rather than as a theory

of

legal practice. This approach posits that, in order to understand and learn

the operation of law, it is not enough to internalise

legal practice. Law must

be seen and studied as a social practice. As such, law is part of social

organisation at large, its historical

processes and its evolutionary

differentiation. For the legal studies approach to succeed, it is necessary to

leave sociological

theory intact even if used in the jurisprudential domain.

Further, the legal studies approach posits — and this takes us back

to

Eugen Ehrlich — that the application of sociological theory is a

“hands on” experience for the law student.

This means that, learning

law is experienced as a sociological observation of the social practice of law

which can be conducted by

the students themselves just as much as dogmatic

expertise is trained successfully only where the law student learns to argue

successfully

by imitating legal practice.7

This is

an attempt to achieve more than simply placing the sociological or sociolegal

course alongside others ready for rote learning;

that is, a course which just

equips the law student with the dogmatic wisdom of the history of ideas of

sociology of law, a hotch-potch

of possible theoretical approaches, a collection

of sociological “buzzwords”, a knowledge of the literature of major

sociolegal studies and, at best, a hit-list of social science research

techniques. Instead, the integrity of constructing sociological

theory can also

be preserved in a legal education environment if the use of sociological theory

is practised. Practice demonstrates

to law students that sociological theory is

as much or as little the final word on the social reality of law as a statute or

a judicial

decision is the final conclusion on the legal reality of law. Law

students will learn to understand that the use of sociological

theory is only

meaningful if it ties in with (practical) social science research observations,

and that research can only be meaningful

if it is guided by theory. Also

lawyers, as much or as little as sociologists, do not develop sharp eye for

social process just by

looking into books. In sum, legal education — if it

wants to be committed to organising practical sociological knowledge for

lawyers

as the legal studies approach suggests it should be — should not be

allowed to have sociology of law taught as legal

doctrine in the disguise of

“interdisciplinary approaches” and with reference to some alleged

requirements of legal practice.

SOCIOLOGY FOR LAWYERS AND SOCIOLEGAL RESEARCH

The experiences derived from a specific sociological

course in the legal education environment may serve here as an illustration of

the legal studies approach suggested here. Sociology is taught to law students

in the framework of the course Sociological Jurisprudence

at the Faculty of Law

of the University of Sydney. This course is offered by the Department of

Jurisprudence as a specialised course.8 This means,

that the course may or may not be the only course in the curriculum of the law

faculty where sociological or sociolegal

knowledge is used and applied, but it

is the only course in which the sociological approach itself rather than the

substantial results

which it may or may not produce is made the subject of the

course. This course makes theory construction and research methodology

its

primary concern; it does not assume that methodological skills and theory

consciousness are the inevitable by-products of legal

education whenever

substantive rules and procedures of constitutional law, company law, criminal

law and so on, are taught. In “problematising”

how human knowledge

in general and scientific and legal knowledge in particular are produced and

socially reproduced, the course

specialises legal knowledge further.

Such a

methodological self-consciousness is, of course, at the core of scientific

knowledge production at large. The purpose of the

scientific organisation of

knowledge is to observe accountably how scientists and others make their

observations and to hold this

process of observation open for making further

observations. Legal education can generally avoid such a scrupulous, intentional

indeterminacy

in its reproduction of knowledge because the objective of legal

education is the communication about practical knowledge (“Tell

me, how

would you decide”) and to close the operation of such knowledge

normatively (“Tell me, on what (dogmatically

accepted) reasons do you base

your decision(s) and how do you justify (rationalise) it/them”). As a

result, the theory of legal

practice as communicated through legal education is

an eclectic arrangement of operatively closed (dogmatic) concepts. Here the

sociology

course can re-introduce indeterminacy of knowledge and problematise

both scientific and legal knowledge production. It can demonstrate

how the

production of knowledge is primarily a social process and exclusively socially

determined,9 and that we only know what we think is

worth knowing. It could even be said that lecturers who teach sociology in law

schools have

an obligation to make law students see the connections between the

social construction of knowledge and the reproduction of legal

knowledge, to

make the invisible factors behind both the operation of law and the learning of

the operation of law more visible.

In this sense, the function of a sociological

course in the legal education environment is not that of a course in sociology

of law

but that of a course in sociology for lawyers. It seems that only in this

framework sociological knowledge and sociolegal research

can assume a practical

meaning for law students.

The overall objective of this course is to

introduce the law student to social science research which is guided by theory.

This is

attempted by presenting, in the first part of the course, sociology and

sociological concepts with one consistent theory design10

and by relating the historical plurality of sociological theories and

concepts consistently to this theory design.11 The

rationale for this approach is:

In summary then, in a situation in which a certain compacting of the introduction to sociological research is necessary so that students quickly develop competence for undertaking their own research, with respect to both theory-construction and the conducting of methodologically controlled observations, it is not only a possible but a meaningful choice to include a practical ethnographic exercise in the programme of a course in sociology for lawyers.

The Organisation of an Ethnographic Study in the Legal Education Environment

The historically and culturally determined

limitations of legal education are well known.13 The

dogmatic emulation of legal practice gears students to rote learning and to

cramming for examinations rather than to prepare

them for participatory

self-learning. It produces the typical profile of the performance of the law

student population as the result

of their socialisation responses under

educational arrangements which are, in this specific form, hard to find in any

other field

of tertiary education. Students are primarily disinterested in the

content of and only instrumentally involved in their studies.

This means that

studying law is rarely experienced as intrinsically rewarding other than by

leading to a useful degree; law students

rarely find lectures to be a

stimulating experience and they do not come to lectures when they can avoid

doing so; they take down

and trade lecture notes rather than to annotate and

selectively evaluate lectures themselves; they rely in their studies more on

textbooks than on research literature, especially from other, non-legal

disciplines,14 and they are more concerned with the

legal-professional status of the person who said something than with what was

said; they give

their limited attention preferably to subjects the utility value

of which is established by high examination pressure, and so on.

These

socialised routines, rather than educationally intended learning behaviours, may

be effective to pass successfully through

law school but they act clearly as

obstacles for the participation in a sociology course in a legal education

environment. In some

respects these obstacles can be reduced by organisation and

preparation, for instance by a more central and frequent use of teaching

aids

(projection of visuals for graphs, organisation charts, or simple lists, etc.)

and a meticulous timing of each step of the introduction

and discussion of new

material. This applies particularly to the research work undertaken by the

students themselves which needs

a longer lead time, depending on the objective

of the study and the class size. If, for instance — as in our example

below

— the fieldwork of 70 students has to be coordinated and conducted

within the narrow timeframe of two months and the peculiar

hydrocephalic

demographic structure of an Australian state and, above all, without

“burning the field” which —

apart from all ethical

considerations — may be the research environment for many sociolegal

researchers and law students to

come,15 early thought

must be given to the research area for and the nature of the fieldwork.

However, in some respects the participation of law students is enhanced in a

sociology course through its research orientation. While

the amount of work and

the investment of expertise which are necessary to conduct such a course are

considerable, they not only pay

off best but practically are only possible if

the teacher is involved in sociolegal research and can utilise the lectures for

the

development of ideas and concepts for theory-construction and research

design by discussing them with students but also by doing

fieldwork according to

such concepts together with the students or independently from their work. In

this sense, a course of this

type can be seen as the useful extension of

sociolegal research, especially as a pilot study or in its explorative stages.

The material

interest of the lecturer in the results of the didactical process

can lead to a more consistent design of the course, and above all

to a more

meaningful involvement of the students in it: here research is not seen as a

simulated exercise but as a meaningful piece

of collective work which connects

with “real life” and the processes of scientific knowledge

production.

Table 1: The Day in Court

|

COURT ENVIRONMENT |

|

|

THE LAW PUBLIC |

THE LAW OFFICERS |

|

Law at a Distance

|

Law as Work Practice

|

|

ê

|

ê

|

|

Defendants

Plaintiffs Witnesses Support

Audience

|

Magistrates/Judges

Clerks Orderlies Police Lawyers - Prosecution - Defence |

Design and Execution of Research versus Assessment of Student Performance

Under the given restrictions, where didactical

efforts may conflict with research efforts, projects can only be very narrowly

defined

and can attempt, in sample size and quality, only a limited

representativity. However, also here an ethnographic approach has advantages.

In

its explorative thrust, this approach does not aim at the representativity of a

given sample but at the validity of the observation

of given contexts, processes

and outcomes. This allows the student to focus on the case in hand rather than

on attempts to accumulate

a great number of cases, often in a rather superficial

and wasteful manner. In this respect, projects in two previous years which

had

been directed by more stringent sampling requirements for the collection of

quantitative data proved to be less satisfactory

under the didactic aspect. The

structured nature of the research tools (interview with partly structured

questionnaire) in order

to obtain quantitative data, and the lengthy statistical

analysis and evaluation of the data prevented wider participation by the

students in the project over its full duration. The evidence from this

experience supports the position that it is more desirable

for students to

design and conduct their own studies during the course and under supervision

rather than practice established research

routines, and that they also are given

the opportunity to evaluate their studies and report their major findings, as

far as this

can be pressed into the extremely short time span of a semester (14

weeks). Obviously, striking a balance between meaningful learning

and fruitful

research can only be approximated by continuous experimentation.

One factor

which may upset this balancing in the legal education environment is the

all-deciding requirement of student performance

assessment. This has the

distracting consequence that the research activities of individual students and

their results have to be

designed in such a way as to be examinable on an equal

footing. In other words, the performance of students needs to be assessed

uniformly where they, in fact, may possibly perform quite heterogeneous

tasks16 and performance requirements need to be

policed. On the other hand, closer scrutiny of student performance could be seen

enhancing

the quality of research in all stages, including a closer observation

of interviewer behaviour. Finally, assessment of research and

research

operations can assure students that, by conducting demonstrably their own

research, their own and independent contributions

count rather more than the

reproduction of the wisdom of others lifted from notes and casebooks.

In

balancing the advantages and disadvantages of the requirement of performance

assessment, thorough consideration must be given to

form and to the fact that

assessment is of crucial importance for a high actual participation

rate.17 In the framework of highly instrumental student

behaviour such as in a law school, the form of assessment interacts rather

directly

with actual student involvement (attending lectures, attention,

strategic advantages of given choices and so on. The resulting student

performance, however measured, is a consequence of how well the form of

assessment manages to reflect the teaching-learning objectives

in terms which

are relevant and meaningful for the student. With the on-going complex change of

how law students construct what is

relevant for them,18

only continuous experimentation can provide answers. Our three projects ranged

from a mix of a compulsory essay (for the theoretical

part of the course), an

optional research assignment (with 90% participation) and an open book

examination (designed for policing

participation)19 to

a compulsory essay and a compulsory assignment in lieu of the

examination.20 Over the same period, assessment of the

research assignment varied from an assessment of the quality of methodological

procedure

requirements (with respect to initially structured but subsequently

partly unstructured interviews)21 to an assessment of

the quality of methodological procedure and of the findings obtained with the

applied approach (see chart 1).

In the first exercises of this kind, control of

the identity of the presented research work was obtained at first through a

personal

interview of the lecturer with each student about their work. This was

later replaced by the current combination of, on the one hand,

the mandatory

requirement of providing transcripts obtained from audiotaped interviews and, on

the other hand, a social control component

in form of collective student

work,23 Experience with this variety of assessment

procedures showed, in sum, that the move towards dropping the compulsory

examination and

making the research assignment compulsory instead, reduced

attendance in class but increased the quality of both theoretical essays

and the

research work in terms of their originality and the expression of well-reasoned

opinions. This seems to support the proposition

that in the legal education

environment students respond well to the offer of having self-induced work

rewarded rather than conformity.

The experience also suggests that they

differentiate succinctly between the liberty to provide for the assessment of,

as one student

put it, “true expressions of opinion based on research and

the subtle pressure in other law subjects to reproduce faithfully

and somewhat

mechanically what has been presented to them in class.

THE DAY IN COURT — AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY

The above experiences and considerations suggest that

research work in a sociology course for lawyers should preferably be a pilot

study rather than constitute part of an already established study in which

students perform only some research functions. An ethnographic

study of local

courts qualifies as a didactical pilot study in many respects. Even though there

is a considerable amount of research

literature on the operation of courts,

comparatively little of that research is devoted to the study of local courts.

The bias towards

research predominantly of the appellate and higher courts

underlines the fact that research on courts is conducted generally under

the

guidance of a social control concept which is provided by legal doctrine and by

an internal view of legal system operation. This

doctrinal perspective posits

that courts are a rationally used instrument to effect social control and that

the higher the courts

are, the clearer (better “measurable”) the

effects of the operation of courts are seen to eventuate. This perspective

posits further that the normative decisions by courts have a direct, even if

unclear, effect on social life and that these effects

correlate positively with

the operation of higher selectivity in the legal system, as reflected by the

differentiation of courts

and in legal practice. In other words, legal decisions

are the more effective the higher the court is which issued the decision.

Law

students internalise this legal theory of the operation of courts by studying

almost exclusively cases and decisions from courts

of superior jurisdictions.

Local courts are almost non-existent on that normative map.

A sociological

perspective on how law operates, suggests almost the opposite. While there is no

question that legal systems become

more stable by a selectively controlled

purification of internally produced decisions at higher levels (stabilisation of

precedents

and doctrine, appeals, “hard cases” and so on), it is by

no means clear that the higher level law also means more effective

law. From a

sociological view, law appears to operate as one and same law on all levels;

legal systems operate, as a whole, the same

highly differentiated structure of

legal (internal) communication about what is law and what is not in order to

arrive at legal decisions

of any type. This communication includes the message

that the work of the superior jurisdiction is concerned with referring law

events

(cases) to law in a small number of cases, while the work of local courts

is concerned with referring “not-law” events

or “not-yet

law” events to law in a great number of cases. From this perspective, the

operation of local courts can be

seen as the crucial border patrol where legal

systems enact selectively their reproductive everyday interchanges with society

at

large and where this is experienced as law.

Also the Australian research

literature on courts, as far as it can be found, examines the operations of

courts predominantly under

the perspective of the social control paradigm. The

central question here is how measurably efficient courts are in their

administrative

operation, or in other words, how fast their case load is turned

over, with the assumption that this administrative efficiency is

somehow related

to and produce something like “order” or “justice” in

society.23 Instead, the objective of the pilot study

conducted by the students in 1989 was to examine whether such assumptions of the

connection

between organisational efficiency and effective social control

effective hold and how the administrative operation of local courts

is actually

experienced by officials and the public as the operation of law. In order to

proceed with this analysis, the social control

concept was contrasted with a

concept which sees the operation of local courts as a design for the operative

closure of legal decision

making which, first of all, is necessary for the

reproduction of the legal system. In order to test this concept, the research

design

of an ethnographic study was used to canvass the context, processes and

outcomes occurring at the day in court in their entirety

of social organisation

rather than as discrete occurrences at the will of individuals.

Theory Design

The approach of the theory of social systems suggests

that the social control concept can only describe the normatively desirable

or

perceived goal of social control but not the actual operation of courts. The

actual operation of (local) courts is the result

of a complex, on-going

aggregation of communicative events which constitute communicative processes.

Stabilised communication and

nothing else, in turn, constitutes social

systems.24 Conversely, social systems, and (local)

courts among them, need on-going communication for their continued existence.

Local courts

provide the legal system with an unceasing communication about law

through their exchange with the public expressing what is lawful

in everyday

life and with respect to everyday life situations. In this sense, local courts

constitute the “life-line”

for the operation of legal systems: they

feed, by handling a massive caseload in their daily selective operation, a

continuous stream

of such communications to the legal system as a whole.

On

the other hand, the operation of local courts shows also the problematic nature

of the selective handling of communication with

the legal system and about law.

The prime function of courts is to sequester and produce further legal

references. In a strict sense,

therefore, courts do not offer solutions for the

everyday situations about which courts communicate with the public but they

produce

only answers for the legal system which confers here with itself and

reproduces law as a result. Overall, the public have difficulties

to see the

concrete effects or successes of court action, but they can feel very well the

repressive power of law, its diffuse authority

and the shadow of coercion. The

public rejects, accepts or even seeks legal references for their own further use

in organising everyday

life mainly because of that diffuse authority of the law.

On the other hand, this diffuse authority distracts attention from the

fact that

courts deal with the law and not with people, and that they have no control over

whether or not legal communication is

in fact accepted by the public. This is

even so when courts use force, which may hurt people economically,

psychologically or physically.

Yet punishment is not related to how and why

people act in the way they do but is only relevant to the consistency of legal

operation.

In this context of the separation of the levels on which, on the one

hand, the legal system and the courts operate and, on the other

hand, other

social systems and people operate, the legal solution may become, but need not

become, a “real life” solution

for the case in hand and for the

parties concerned. However, it provides the legal system in every instance with

the essential communicative

events which it needs for its reproduction. And

while local courts bravely stem the tide of “sausage factory”

workloads

allegedly to the detriment of the individual case, it is,

paradoxically, precisely the intensity and high frequency of the turnover

of

caseload in the local courts which characterises the essential quality of a

legal system.

In our ethnographic approach, the unity of a local court

appears as a scene on which the on-going communication can be expected to

be

necessarily biased toward feeding the legal system with communicative events.

Accordingly, the public contribute their own stories

— more or less

reluctantly — only to some measured degree and not without heavy-handed

selection (see table 1). The law

officials are involved in producing legal

communication, and they benefit from producing such a privileged communication

in different

degrees.25 They experience the

reproduction of law as their work practices. The public, that is, those lay

persons who come to court are exposed

to or expose themselves to that privileged

communication and they accept the outcomes of this communication in varying

degrees. They

experience the reproduction of law as a distanced happening with

mythopoetical effects. The instances of concrete interaction and

the

cross-communication between these two different spheres of court action are

comparatively rare and are highly controlled through

legal procedure and

legal-professional work practices. However, for the legal system to succeed in

reproducing law, officials and

public must be seen to communicate with each

other. This is what having one’s day in court is all about. We can,

therefore,

assume that the main function of local courts is to facilitate that

kind of communication which the law officers and the public need

in order to

proceed with communicating about the law in the way they do.

The objective

of the study was to determine, through empirical research, the structure and the

operation of this communication in

local courts and in what way it is related

both to the operation of law in society at large and to the social need of

individuals,

agencies or organisations for what they see to be

“their” day in court.

Methodological Design and Execution

In the methodological design of the study, the

didactical requirements of the law degree course and the research requirements

of empirical

research intersect. Whenever the two conflicted, primary

consideration was given to the didactic objectives of the course. To begin

with,

the feasibility of the project was addressed by contacting the administration of

justice in Sydney on two levels. On the local

level, contacts were made with a

selected Clerk of the Court who was invited to address the students in a

lecture, in which the practical

work of local courts was described and

discussed. On a higher level, letters were written to the Attorney General, the

Chief Magistrate

and the Chief Justice of the Land and Environment Court

respectively which set out the objectives of the study and asked for permission

to conduct the exercise with students. Permission was granted in each case;

although, in the case of the Land and Environment Court

only after a

consultation with the Chief Justice.

The descriptive presentation and

discussion in the lecture given by the Clerk of Court provided the basic

information for the actual

operation of the courts.26

From this base, items for the interview-guide were selected which consisted of

17 unstructured (open-ended) questions which to both

the public and the officers

were to be addressed.27 The function of the interview

was to solicit from the respondents their references to the concepts of law, the

operation of law,

the justice or fairness of the law, their observations of the

actual operation of the court, of the court as a work environment,

the

atmosphere of the court, and so on. This interview-guide was designed in class

and it was decided that both the public and officers

should be asked the same

questions, as far as was practical and meaningful.28 It

was further decided, that, with respect to the pressure from the court

environment on the respondents and the requirement of a

full length

transcription of the recorded interviews, the length of the interview should not

exceed approximately 30 minutes.29

Further, the

expert interview with the Clerk provided also a list of a mix of 13

suitable30 criminal, central city and suburban courts

and some special courts on the first instance level (children’s/family

court, Commonwealth

court, Land and Environment Court) in Sydney. We contacted

the Clerks of all courts and asked for their permission to conduct the

interviews on their premises. At this stage three Clerks felt that the workload

and/or size of their courts would not allow participation

by their staff in the

exercise and declined co-operation. With 10 courts remaining, 10 teams with 7

students were formed. Students

were allowed to select freely a court with the

result that final teams were not made up equally of 7 students in all teams.

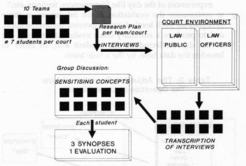

With the research teams formed, the task of the student was (see table 2):

Table 2: The Day in Court

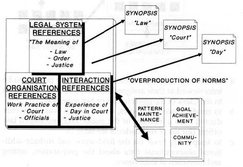

Table 3: The Adjustive

Function of Law

The Operation of Local Courts

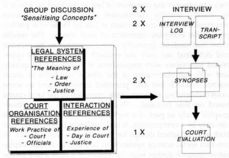

The assessment of student performance was based on the quality of the

execution of these tasks and the transcripts, logs, synopses

and general court

evaluation provided the documentation for such an assessment (see table 4).

Students were particularly instructed

to observe the ethical demands on social

science researchers not to exert any pressure on the potential respondents to

give or to

proceed with an interview and to begin every interview with the

assurance given to the respondent that the interview was voluntary,

that the

respondent was free to abandon it at his/her will, that no names or

identifications would be recorded and that all information

gathered would be

treated confidentially.

The alternation of collective and individual work

sequences in the design of the exercise was expected to lead to a better basis

for

the research experience of the student. It was supposed to offer a further

level for the discussion and reflection on research results

which, due to the

restraints of the type of research conducted here, would appear to the

individual student highly contingent and

unrelated to the larger context of the

court operation. It was also expected that the collective work should provide

for a better

participation and exercise a degree of social control over the work

of the students among themselves, such as preventing faked

interviews.31

Table 4: Assignment Requirements

CONCLUSION

The objective of qualitative research is to avoid the

early operative closure of the research approach. This means, that, rather than

using a prefabricated grid of concepts which is the result of scientific

operations following the rationale of scientific discovery

(formulating and

testing of hypotheses through analytica1 statistical measuring designs) and

which extracts from the units under

research only those references which make

scientific sense to the researchers themselves,32 the

interpretive researcher attempts to tap with his or her observations the use of

the concepts (references) which are used by the

participants

themselves33 and which help them to communicate in

everyday life. In evaluating the use of these references, the researcher can

attempt to reconstruct

social processes as a concatenation of the use of such

references (communication) which constitutes the social reality of the

respondents

and which directs their actions.

The practical use of such a

research approach can constitute a substantial learning experience for law

students where they are put

into the position of the researcher and where they

can observe the operation of law at the level on which it is actually socially

constructed. In this case students observed the social construction of law by

those who participate in the everyday operation of

local courts. The results

show that students generally were committed to the exercise and delivered not

only the research material

of 140 open-ended interviews with respondents in

courts of high quality and with full observance of the ethical standards of

social

science research but also provided excellent, and in some cases

outstanding analyses of the operation of the local courts based on

that

material. Though the design of an ethnographic study as part of a sociology

course for law students can only be a compromise,

it is doubtlessly highly

successful both as a didactical design for teaching law students how to conduct

social science research

on law and as a basic explorative research design with

the quality of a pilot study on the operation of local courts.

The most

problematic part of the design overall was the assumption that students would

appreciate collective research work and that

they would be able to use group

discussions and group work to their benefit. These results show that students

partly did not fully

understand the objectives of the group work or did not see

the necessity for devoting time to group discussions, often cooperated

only

reluctantly in a team and a few not at all. Clearly, this collective element

should either — time permitting — be

strengthened organisationally,

for instance, by explaining in more detail the objectives of the group work and

by including time-tabled

group sessions in the programme of the course in order

to monitor the progress of group work. Alternatively, it should be dropped

altogether notwithstanding the social control function of group discussions.

However, even given the poor cooperation of a few students, the reliability

and the quality of the data and the observational and

evaluative skills of law

students are extremely high. The collected material is a rich and fertile ground

for further and more controlled

ethnographic studies on local courts and on

court operation in general. Above all, however, the exercise has a stimulating

and eye-opening

effect for many law students, some of whom — though in the

last years of their law studies — not only set foot for the

first time

into a local court but also felt, for the first time, that they were beginning

to understand what law is all about.

* Department of Jursiprudence, University of Sydney.

© 1990. [1991] LegEdRev 3; (1990) 2

Legal Educ Rev 59.

1 E Ehrlich, Freie Rechtsfindung und freie Rechtswissenschaft (Free legal decision-making and free legal science) (Leipzig: reprint Aalen, 1973) 196; partly translated as, Judicial Freedom of Decision: Its Principles and Objects, in (1917) 9 Science of Legal Method, The Modern Legal Philosophy Series 47.

2 Id.

3 KA Ziegert, The Sociology behind Eugen Ehrlich’s Sociology of Law (1979) 7 Int’l J Soc L 225.

4 KA Ziegert, Legal Education at Work: the Impossible Task of Teaching Law (1988) 3/4 Tidskrift für Rättssocwlogi (No 5) 183–211; KA Ziegert, Lifeworld and Legal Impact in Australia and Sweden: the Diffuse Law Concept, paper presented at the Australian Law and Society Conference, Melbourne, 12–14 December 1989.

5 Ziegert, Legal Education at Work, supra note 4.

6 KA Zeigert, Dogma im Zeichen des dicken Hunds. Die Rechtssoziologielehre in der Juristenausbildung (The hypertrophied dogma. Teaching sociology of law in the framework of legal education), in R Voigt & A Gorlitz eds, Iahresschrift fiir Rechtspolitik, Vol. 3 (Paffenhofen: Centaurus, 1989) 220–254.

7 This goes to such lengths as constructing moot competitions as the pinnacle of law school performance although perhaps this is typical only in societies with a cultural background for the rhetorical quality of law, that is, in common law or Anglo-American legal culture.

8 This label for the course has mainly historical reasons, because the course is one strand out of five which constitute the (compulsory) subject “Jurisprudence”. Each law student must at least complete one jurisprudence course for the law degree, but students can do more than one strand an elective subjects.

9 I appreciate that this statement can be seen and understood as an imperialist argument and 1 do not dispute that there are many more aspects involved in the construction of knowledge than only the sociological one, ranging from biological sensory equipments to political discourse. However, these other aspects cannot detract from the fact that all individual consciousness and learning determined by social interaction and communication and that the issue of intersubjective (social) exchange is the pivotal one in the reproduction, that is, ultimately social construction of human nature.

10 While this is not unusual for sociologist training, it is in sharp contrast to the highly eclectic approaches to teaching and learning in legal education, particularly in its jurisprudential fringes.

11 This leads to a working knowledge of the theory of social systems and includes a brief outline of the history of sociological ideas, especially with respect to law. The design of the theory of social systems (“operatively closed systems”) is — as far as I can see — the most advanced development of sociological theory and at present without viable alternative but it does not claim exclusivity. The educational advantage of the theory design is that it enables the student to observe social process on the micro-social (intra- and interpersonal) levels and on the macro-social (intra- and intersocietal) levels with one and the same theoretical approach. It also links the social science aspects of human existence with psychological and natural science aspects.

12 This is so even when all students, in fact, combine their studies toward the law degree with studies toward another degree (in arts, economics or science). Though students individually may have had the advantage of exposure to research methodology in these other studies, especially in economics, history, government, anthropology and sciences, it remains a difficult task for these students to relate the relevance of this experience to sociolegal research. This situation is compounded by the fact that, as far as the University of Sydney is concerned, no degree in sociology is offered. As with so much else in legal education, it is unclear what the studies toward a combined law degree actually achieve other than the improved marketability of the degree or accumulation of cultural capital. Ziegert, Legal Education at Work, supra note 4.

13 Ziegert, Legal Education at Work, supra note 4.

14 This tendency is reinforced by the highly specific meaning of ‘’research” to which law students are introduced in their first semester studying law. Legal research here means locating law texts (textbooks, cases, statutes, references to cases and statutes, etc.) and is internalised as this locating of texts rather than as the logic of scientific discovery.

15 Though, in a strict sense, no researcher leaves the field in the same state as he or she found it, thoughtful planning of how to enter, work and leave the fields of ethnographic study can contain the worst damage and can make research a fruitful experience not only for the researcher but also for those professionals, officials and respondents in the general public who sacrifice their time for the research.

16 For instance, circumstances of interaction with respondents in the field can vary greatly and are beyond the control of most, but especially the inexperienced researchers. Also even if, for instance, respondents cooperated only reluctantly or not at all, the interview produced valid data (and would not have to be substituted by another interview). However, such a meagre output appeared to many students to be less “good” than if the respondent had talked a lot which would have yielded a longer transcript with a fuller scope of references for interpretation and evaluation.

17 This means actual, self-referential involvement of the student by interest and not just nominally performing the task in one or other form. On the other hand, an over-emphasis on linking student performance with the research assignment, for instance by weighting it as the most important of all components for assessment in the course, would inevitably also increase other “deviant” forms of participation, i.e., faking, cheating, paying others for doing the work etc. which would be equally difficult to police.

18 The mapping of these relevant and meaningful environments by law students can be seen as the actual socialisation effect of legal education. Compare KA Ziegert, The Social Construction of the Legal Mind: A Study of Law Students and the Accumulation of Cultural Capital (Sydney: Oxford University Press, forthcoming 1990).

19 In this mix the essay and the (optional) research assignment counted for 25% each while the examination counted for 50% of the total mark for performance in the course.

20 In this mix the essay and the research assignment counted for 50% each of the total mark.

21 With respect to the care and meticulousness with which interviews had been prepared, executed and documented.

22 The requirement of the collective groupwork component appeared to present the greatest difficulty in this project and a large number of students resented the idea of having their own achievements made contingent on the achievements of other students. In spite of the fact that great care was taken to explain the structure and function of the group work to the students, a considerable number did not understand or plainly circumvented the group work requirement. It appears that the reference of students to traditional assessment procedures with their highly individualising and competitive implications interfered here most massively as far as the quality of research is concerned.

23 C Briese, Future Directions on Local Courts in NSW [1987] UNSWLawJl 9; (1987) 10 UNSWLJ 127; J Newton, The Magistrates Court 1975 and Beyond (Canberra: Institute for Criminology, 1975).

24 For a more detailed exposition of this approach see Ziegert, Lifeworld and Legal Impact, supra note 4.

25 This does not ignore that there is clearly a further differentiation of both the public and officers (compare table 1) which often is experienced but also constructed as more important (for example, between adversary parties, between clerks and magistrates/judges, between court officers and lawyers, etc.) than the fundamental division between legal and nonlegal communication and the study can, in fact, trace all those further differentiations for further interpretation of their functions.

26 As opposed to the information which students already had about the operation of local courts from legal research, basically only in the introductory course on legal institutions.

27 The interview guide contained also 10 demographic questions which were to be asked, at the end of the interview at the discretion of the interviewer/researcher.

28 Practically and in order to avoid embarrassment, the wording of some questions had to be modified depending whether a layperson or a law officer was addressed, and these modified questions for the one or other group were clustered through filters in the interview guide-line.

29 As a result, interviews with the law public lasted on average shorter than 30 minutes and interviews with the law officers on average a little longer than 30 minutes.

30 Suitability was assessed by the size of the court and whether or not it was big enough to allow a group of about 5–10 students to conduct a sufficient number of interviews with a sufficient variety of respondents without disturbing the field, for instance, by conducting two or more interviews with the same member of the court staff.

31 Though it is difficult to speak with full confidence with respect to the actions of 80 researchers, the only “deviance” which came to notice was a substitution of respondents In variance with the research plan for a specific court in a few cases.

32 For instance, by submitting a question of the type: “Here is a list of the functions of the law a) to d). Please tick the function(s) of law which you consider to be the most important!”

33 For instance, by submitting the question “How would you describe what law is?”

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LegEdRev/1991/3.html