Legal Education Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal Education Review |

|

EVALUATING AND IMPROVING TEACHING IN HIGHER EDUCATION

PAUL RAMSDEN*

The sole question is, What sort of conditions will produce the type of faculty which will run a successful university? The danger is that it is quite easy to produce a faculty entirely unfit — a faculty of very efficient pedants and dullards.AN Whitehead, Universities and Their Function

There are three main issues to consider in any consideration of the evaluation or assessment of teaching in higher education: the nature of good teaching; its measurement; and its promotion.

It is a poignant commentary on the mood of higher education in Australia and the United Kingdom that few discussions of educational quality, accountability, and the appraisal of academic staff have engaged with these issues at other than the most superficial level. Policies have been formed and are being implemented in apparent ignorance of the accumulated educational knowledge that enables these key questions to be rationally addressed.

This article is an attempt to redress the balance by providing a perspective on evaluating and improving teaching performance which brings educational principles into the foreground. The first part deals with the characteristics of effective teaching in higher education and critically reviews the related issues of appraisal, the use of student ratings, and the measurement of teaching performance. The second part examines how we might use evaluation to improve the quality of teaching.

We must start with the idea of “good teaching” — which we can take to mean for the purposes of this paper those activities and attitudes which encourage the highest standards of student learning.

There is a cherished academic myth that good teaching in higher education is an elusive and ultimately indefinable quality. The reality is that a great deal is known about its characteristics (see Figure 1). The research findings on good teaching mirror with singular accuracy what students will say if they are asked to describe what a good teacher does. University students are extremely astute commentators on teaching. They have seen much of it, and they understand clearly what is and what is not useful for helping them to learn. Good teaching involves being at home with one’s subject and being enthusiastic about sharing one’s love of it with others. It requires clear explanations, naturally, but even more importantly it implies making the material of the subject genuinely interesting, so that students find it a pleasure to learn it. When our interest is aroused in something, whether it is an academic subject or a hobby, we enjoy working hard at it. We come to feel that we can in some way own it and use it to make sense of the world around us.

Good teaching involves showing concern for one’s students. This implies being available to students and giving high quality feedback on their work. It entails a demand for evidence of understanding, the use of a variety of techniques for discovering what students have learned, and an avoidance of any assessments that require students to rote learn or merely to reproduce detail. It means being quite clear what students have to learn and what they can leave aside.

Good teaching usually includes the application of methods that we know beyond reasonable doubt are more effective than a diet of straight lectures and tutorials, in particular methods that demand student activity, problem solving and cooperative learning. Yet it never allows particular methods to dominate. There are no simple means to simple ends in something as complicated as teaching; there are no infallible remedies to be found in behavioural objectives, experiential learning, computers, or warm feelings. Good teaching is not just a series of methods and recipes and attitudes, but a subtle combination of technique and way of thinking, with the skills and attitudes taking their proper place as vital but subordinate partners alongside an understanding of teaching as the facilitation of learning. 1

This kind of teaching refuses to take its effect on students for granted. It is open to change; it involves constantly trying to find out what the effects of instruction are on learning, and modifying that instruction in the light of the evidence collected. This is what “evaluation” is fundamentally about, though the term has become debased so that it applies to the task of collecting data rather than collecting, interpreting and using it.

Evaluation of teaching in its true sense is no more or less than an integral part of the task of teaching, a continuous process of learning from one’s students, of improvement and adaptation. Teaching like this involves developing a keen interest in what it takes to help other people learn; it implies pleasure in teaching and associating with students, and enjoyment in improvising.

FIGURE 1

What is Good Teaching in Higher Education?

|

And bad teaching? Bad teaching is usually rooted in unworldly conceptions of instruction (such as teaching being no more than telling or transmitting authoritative knowledge) or in a sheer lack of interest in and compassion for students and student learning. Bad teaching is seen in actions that demean the process of instruction by simplifying it to a series of inflexible techniques. There is a view of teaching which conceptualizes the relationship between what the teacher does and what the student learns as an intrinsically unproblematic one, a sort of input-output model with the works hidden away. If no student learning after exposure to teaching takes place, this model cannot explain why it does not. Occasionally one meets lecturers, on being presented with evidence of student ignorance on a topic that has been the subject of a previous series of lectures, saying tot he students (with astonishment) “But you did go to the lectures last term, didn’t you?”

Poor teaching in higher education often displays one classic symptom: making a subject seem tougher than it really is. This unworthy policy, which is often an excuse for not putting effort into preparing teaching, is rationalized through recourse to the argument that spoonfeeding is bad for students. Its practical effect is to make some students expect to fail, and the expectation is all too often a self-fulfilling one, particularly when feedback on learning is delayed or poor in quality. 2 Good teaching is generous; it always tries to help students feel that a subject can be mastered; it encourages them to try things out for themselves and succeed at something quickly. The teacher’s job is to make every subject seem equally enjoyable, right from the start. There are no subjects to which this rule does not apply.

Bad teaching carries on an intimate relation with mediocre learning. The connection reveals itself most nakedly in assessments which contain examples of questions that can be answered by memorising facts and procedures. Such questions invite students to conceptualize learning as it must often appear to them in a poor quality lecture — as a series of lifeless tokens. Forty-eight years ago WW Sawyer described the effects of bad teaching much more poetically than any research report about learning strategies:

When we find ourselves unable to reason (as one often does when presented with, say, a problem in algebra) it is because our imagination is not touched. One can begin to reason only when a clear picture has been formed in the imagination. Bad teaching is teaching which presents an endless procession of meaningless signs, words and rules, and fails to arouse the imagination. 3

This wisdom is reminiscent of a true story concerning a biochemistry student at an Australian university. She had passed first year chemistry easily, but proved to have (like many of her fellow student) only the weakest knowledge of important chemical concepts. In a special one-to-one tutorial the teacher endeavoured to discover the extent of her knowledge of cholesterol metabolism. “But surely you know something about cholesterol. It’s talked about so much on TV and in the newspapers. It’s an everyday thing”. A light dawned. “Oh. You mean that’s the same cholesterol we did in chemistry?” One wonders what procession of meaningless signs had been presented to this student and her colleagues in chemistry lectures.

There is no need to labour the points about good and bad teaching by quoting a succession of research findings about students’ views of what a good teacher is, or by repeating the findings of studies relating student learning to the quality of teaching. It is only necessary to state here that indisputable connections have been established between students’ perceptions of assessment, teaching and the effectiveness of their learning, at upper secondary and higher education levels, in a great variety of subject areas. We know that students who experience good teaching not only learn better, but that they enjoy learning more. That is surely how it should be; if we love our subjects, we must want other people to find them enjoyable rather than dull. Learning should be pleasurable; there is no rule against hard work being fun. As Sawyer so succinctly puts it:

To master anything — from football to relativity — requires effort. But it does not require unpleasant effort, drudgery. The main task of any teacher is to make a subject interesting. If a child left school at ten, knowing nothing of detailed information, but knowing the pleasure that comes from agreeable music, from reading, from making things, from finding things out, it would be better off than a man who left university at twenty-two, full of facts but without any desire to inquire further into such dry domains. Right at the beginning of any course there should be painted a vivid picture of the benefits that can be expected from mastering the subject, and at every step there should be some appeal to curiosity or to interest which will make that step worthwhile. 4

What then is the best way to measure teaching effectiveness? The myth that university teaching is so idiosyncratic a matter that its nature cannot be defined serves a vital function. If a function cannot be specified, it is easy to resist pressures to judge whether it is being adequately performed. But we have seen that the characteristics of good teaching can be described, at any rate in broad outline.

In its most general terms, evaluation of teaching in higher education concerns collecting evidence about the quality of instruction and its effects of teaching on student learning, and using that evidence to improve teaching and learning. Just as we have clear knowledge of what constitutes good teaching, so we also have a comprehensive armoury of methods for evaluating it. It is not appropriate to go into detail about methods in this type of article; there are several good texts on how to collect and interpret evaluative evidence; an extended discussion of different methods and their applicability was provided in Ramsden & Dodds. 5

The short answer to our question, however, is that there is no one best way. Several methods, preferably at several different levels of aggregation, should be used. Not too much reliance should be placed on evidence from any one source (eg, student questionnaires, peer comments or self-evaluation); and evidence that focuses on a single level of the educational process (eg, the individual teacher) is more difficult to interpret than evidence that touches on different levels (eg, the level of course and the level of a teacher’s particular contribution to it). The purpose of measuring teaching must be considered. An appropriate method for obtaining feedback of one’s own teaching may be absurdly invalid as a means for judging a person’s teaching performance. In spite of the need for a variety of sources, all methods of measuring teaching quality must include students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the instruction they receive. We shall return to the issue of student ratings of teaching in a moment.

It should be clear from what has been said in the previous section about good teaching that one of the most important sources of evidence about the effectiveness of teaching is, somewhat paradoxically, the extent to which lecturers, courses and institutions systematically search out weaknesses and apply the findings of their explorations — the degree to which, in other words, they realize a policy of continuous improvement. This measure of effectiveness has implications both for the demonstration of accountability and for promoting excellence in teaching.

It has been asserted that the assessment of teaching logically demands knowledge of the nature of good teaching and how to measure it. It is of more than passing interest that while we possess both these things, the academic staff appraisal movement in Australia and the United Kingdom has more or less ignored them.

Staff appraisal in British and Australian higher education has little to do with promoting teaching quality, despite its rhetoric. Staff development — the improvement of teaching — and appraisal are two quite dissimilar animals. No amount of assertion that they are one and the same creature can alter their origins and the ways they typically behave. The reason for performance appraisal is entirely political. There is a public perception that much money is being expended on systems of education — at all levels — and that no checking or review of how that money is being used exists. In this context, the letters to an MP from a disgruntled constituent or two complaining about the standard of their children’s university lectures take on immense and disproportionate importance. Here is an opportunity that few politicians will be able to resist to argue for more efficient use of resources by penalizing the indolent lecturer and rewarding the diligent one. This, it is asserted, will motivate all academic staff to try harder, to produce more excellence, so that our scarce resources are better spent.

So entrenched in popular thinking have these claims become that those who would discuss the principles of staff appraisal are advised to be brave men and women. The discussion is now entirely about method. Back in 1986, John Nisbet maintained that in the United Kingdom:

To question the principle of staff appraisal in the present climate of opinion is likely to be seen as unrealistic. The common attitude is that appraisal is coming whether we like it or not; it is only a question of how and how soon, not whether or why. Consequently, so the argument runs, let us introduce our own scheme before a worse one is forced upon us. 6

People who wear an astonished air to greet criticisms of appraisal are right, up to a point. There is no rational defence against the accountability argument. The position that public support will depend on demonstrating accountability is unassailable. But the argument that appraisal as it is currently being introduced will improve the effectiveness of teaching and enhance learning can be assessed rationally.

The proposition that appraisal will improve teaching is exactly analogous to the argument that a statutory curriculum and national testing of school students’ performance will lead to higher standards of student attainment. It is a hypothesis to be tested; it is one proposition among many. 7 The effectiveness of performance appraisal as a method of enhancing teaching quality in higher education has not been presented as a hypothesis to be tested. It has simply been asserted as a self-evident truth.

The validity of the proposition is far from obvious, either logically or empirically. There is no empirical evidence of a positive link between academic staff appraisal and better teaching in higher education. It is not that evidence of the connections is inconclusive; there is none. We do have empirical evidence of the effectiveness of other methods, eg academic staff development work; sometimes these have been erroneously presented as proof; but unless appraisal and staff development are regarded as synonymous, the argument is a non sequitur.

Leaving aside the empirical relation, or absence of it, no analysis of the logical mechanism by which we would expect the qualities of good teaching to be developed in members of staff through appraisal appears to exist. Only if appraisal is redefined to mean more sensitive and dynamic management can a logical path to improvement be traced. Yet many reasons can be adduced against the effectiveness of performance appraisal in an academic context. Among these are the fact that staff are likely to act as their students do when they perceive an assessment system to be inappropriate: they will learn to perform certain tricks in order to pass examinations in subjects they do not understand. They will not become qualified to teach better, but to hide their inefficiencies better. There is empirical evidence that performance appraisal in other organisations which is perceived to be punitive and associated with extrinsic rewards leads to lower outputs and dissatisfied staff. 8 That is bad news for any organisation. It is no use saying that “your” appraisal system, in your estimation, is not designed to discipline the employees. It is their perceptions that determine their actions.

We might also include among the logical reasons against appraisal the argument that academic staff motivation in particular is increased only to a limited extent by competition, and that beyond a certain point external rewards and punishments create strong adverse reactions among teachers in higher education, and diminish their desire to cooperate in increasing the effectiveness of teaching though collegial procedures. There are other arguments, including the research evidence that feedback on teaching performance does not necessarily improve teaching.

Perceptions of appraisal as a restrictive and time-wasting administrative procedure, essentially punitive in character, are probably the most common ones among staff in higher education institutions — at any rate in the ones I have had regular contact with. Many people feel threatened; they feel they are being required to compete against others in a zero-sum game. Some are actually being threatened, even before formal appraisal mechanisms are in place, with a relish that is disturbing. Several acrimonious disputes between staff associations and institutional management in Australia universities over the introduction of appraisal have done nothing to reduce the sense of anxiety.

An instructive example of the gulf between appraisal policy and the improvement of teaching is contained in the procedures for performance assessment laid down in this particular wage agreement. The agreement draws on statements in the Government’s White Paper about the need to introduce regular reviews of staff performance as a national priority for higher education. It deals among other things with methods for handling unsatisfactory performance and training supervisors, and it refers to mechanisms for assessing the performance of academic staff. However, its terms are entirely procedural. For example, there is no mention of what the different levels of teaching performance are, or how the levels, once established, are to be judged.

One does not have to be an advocate of standardized testing of ability to appreciate the ingenuous conception of assessment that underlies this position. There will be testing, but we are not sure what we will be testing or how we will know when the candidate has achieved what it is. Presumably, like CP Snow’s academics, “sensible men [sic] will always reach sensible conclusions”. Evidently the levels and judgements are to be established locally; this seems liable to produce bizarre effects, with minimum standards and fairness varying widely between institutions depending on the political and educational skills of the particular union and management. Some institutions’ local interpretations include among the sources of appraisal evidence “peer review” and “student response”, blissfully ignoring the facts that peer review of teacher performance is generally invalid for making personnel decisions and that student questionnaires (unless administered under rigid control) will provide data that cannot be used to judge performance fairly.

A sure sign of poor assessment methods in a higher education course is concentration on procedural technicalities (eg, number of words in an assignment, whether candidates may write on more than one side of the paper, what sort of referencing conventions they may and may not use) to the exclusion of clear statements of what skills and understandings are required to be demonstrated. The Australian agreement is just this kind of document; and so are many of the materials being used to train supervisors (generally heads of departments or divisions) in implementing it. These materials encourage a superficial approach to performance appraisal; they focus on matters such as how to carry out an appraisal interview rather than on what to appraise and how to measure it validly. They are redolent of a conception of educational development as training in technique.

But, you may say, is it not important to know how to interview an appraisee? It is, but let us get the matter in perspective. It will hardly be contested that a sine qua non for good teaching is a clear grasp of the subject being taught. This knowledge would seem to take logical and temporal precedence over matters such as writing clearly on the blackboard. People who put the second matter first would rightly be accused of putting the cart before the horse. The agreement and the training materials have the cart right up front. A supervisor’s first task must be to develop a clear grasp of the material for which he or she is responsible. This material is the nature of good teaching and how it can be practised within a particular subject area. By what other means can he or she set standards, judge whether they are being achieved, and help the supervisee to improve? Learning about good teaching and how it can be perfected in specific disciplines is no small task. Many academic staff in Australian universities may look forward to being appraised by supervisors who have had a few days of training in procedures but who lack the educational knowledge to form competent judgements about teaching.

The selling of appraisal in higher education, both in Australia and the United Kingdom, is an instantiation of what Karl Popper has described as Utopian social engineering. 9 The Utopian planner is concerned to stereotype interests to make them manageable, believes he or she has secure knowledge of the future and of what is right for others in the future, and is determined to exercise top-down power to this end. Utopian social engineers are not open-minded about the effects of the changes they implement. They know they are right. These are the devices of totalitarianism, utterly antithetical to the traditions of higher learning as we understand them. The appraisal packages have typically been sold not on the basis of reason and evidence, but on an appeal to faith, prejudice and credulity.

It is optimistic to maintain that we still live in a climate where new schemes for appraising teaching that focus on cordially improving quality can flourish. The logical arguments for appraisal tied to performance assessment are unconvincing; the empirical evidence for its effectiveness is non-existent; teachers’ attitudes to appraisal (but not towards help for improving their teaching) are unwelcoming. 10 While the political pressure for teacher appraisal in higher education is irresistible, we runs an enormous risk that the price to be paid for accountability will be a reduction in teaching quality. Only the most careful education of supervisors and diligent evaluation of the effects of appraisal offer hope for making it into a successful means of improving teaching.

I hope it will be clear that the reason why I have been hard on teacher appraisal in higher education is chiefly because it embodies an unsatisfactory conception of evaluation, teaching and learning. Improving teaching evidently involves a process of learning. Academic performance appraisal’s model of learning is precisely the one that informs so much bad teaching: that motivational sticks and carrots have to be employed to force people to learn things they don’t want to learn. Then, appraisal’s advocates seem to be saying, teachers who are motivated to improve will feel an obligation be trained to acquire teaching skills. The logical outcome of this process of teacher learning, entirely predictable from studies of student learning, will be to reinforce naive conceptions of teaching — in particular the view that teaching in higher education essentially involves no more than the acquisition and deployment of technical skills that will enable the lecturer’s knowledge to be transferred to students. 11

Appraisal’s model of teaching and learning is nowhere better represented than in the extraordinary belief it professes in the powers of student questionnaires. I say this from a position of commitment to the use of student ratings both for diagnostic and judgemental purposes, and from personal involvement in the development and national testing of a student rating instrument as a performance indicator in Australian higher education.

Students are in an excellent position to provide information about the quality of instruction. Valid methods of collecting such data exist; these methods should be used. It is wise to be circumspect about using student ratings to make judgements of teaching quality and to recognise their complications as well as their virtues.

These views seem unremarkable enough. They make no claim to originality, and they are consistent with research findings and with the best practice in North America.

Why, then, do they have to be restated here? Because, unfortunately, they cut right across common sense perceptions of evaluation and staff appraisal in Australia and the United Kingdom. To someone who is familiar with the advantages and disadvantages of this form of measurement, the use of questionnaires to assess staff performance is taking on an importance altogether surprising. The only explanation would seem to be that student rating questionnaires are seen to fulfil an irresistibly attractive combination of purposes. They are the heaven-sent gadget that will make a quick and easy repair. Importantly, they are perceived to be a talisman that will guard against accusations that universities are not accountable; they provide the outside world with evidence that we are doing something about teaching. 12 For some senior staff, it would appear that they are appraisal. Questionnaires are thought to be attractive for their objectivity; they are easy to distribute, collect and process (and therefore cheap); they offer an opportunity to sort out the academic wheat from the chaff.

That these perceptions are incorrect or at best misleading would soon be seen by anyone who took the trouble to study the student ratings literature. The uses and misuses of student rating questionnaires have been described in detail elsewhere. 13 As most of what was said in that book was based on easily-accessible published information anyway, there seems little hope of convincing the doubters by repeating it all over again. The present remarks refer to the excellent reviews by Centra 14 and McKeachie, 15 among other things. It should be clearly understood from the beginning that there is no fair way of using student ratings for appraisal without going in for a sizeable investment. There is no shortcut; once in, rigourous standards must be applied and maintained.

There is nothing intrinsically valid about something that has numbers attached to it. An apple with a price tag on it is not necessarily a better apple, nor does it provide a less subjective eating experience. It sometimes seems as if members of academic staff trained in (for example) the exact sciences or the precision of legal argument instantly forget their knowledge when it comes to applying measurement in educational settings. Maybe education is thought to be too soft a subject to require the structures of scientific method. Or perhaps they simply have a misplaced notion of what constitutes objectivity in education. Many of the student questionnaire advocates could do worse than to read and digest Peter Medawar’s eloquently expressed views on the contrast between the natural sciences and the “unnatural sciences”:

It will at one be recognized as a distinguishing mark of the latter that their practitioners try most painstakingly to imitate what they believe — quite wrongly, alas for them — to be the distinctive manners and observances of the natural sciences. Among these are: (a) the belief that measurement and numeration are intrinsically praiseworthy activities (the worship, indeed, of what Ernst Gombrich calls idola quantitatis); (b) the whole discredited farrago of inductivism — especially the belief that facts are prior to ideas and that a sufficiently voluminous compilation of facts can be processed by a calculus of discovery in such a way as to yield general principles and natural-seeming laws; (c) another distinguishing mark of unnatural scientists is their faith in the efficacy of statistical formulas, particularly when processed by a computer — the use of which is in itself interpreted as a mark of scientific manhood. There is no need to cause offense by specifying the unnatural sciences, for their practitioners will recognise themselves easily; the shoe belongs where it fits. 16

The best short description of the validity standards that must be met is by Scriven. 17 They WE: stringent. There can certainly be no question of using results collected by lecturers themselves, which form of collection is the best way of using questionnaires for diagnostic purposes. A sufficient and representative sample of students from each class must respond, the forms must be distributed and collected under specially-prescribed conditions at particular times (certainly not by the lecturer), ratings over several courses over a period of time are required, and ratings must be collected on every member of staff. Even then, the results cannot be guaranteed free from contamination. The standards for diagnostic purposes may be relaxed a little. While you are unlikely to learn anything very useful from an incorrectly administered rating form packed with invalid items, at least you will not be sacking anybody or denying tenure for it. In self-evaluation, the responsibility lies with teachers not to cheat themselves.

For the reasons given above, a special corps of evaluators will be needed to collect and process the data, to guard against cheating, to collect data from other sources, and to correlate these sets of data. Whatever else it may be, any appraisal system has got to be fair and to be seen to be fair. 18 Student ratings alone must never be used for appraisal: as Centra puts it, ‘The evidence clearly indicates that no one method of evaluating teaching is infallible for making personnel decisions. Each source is subject to contamination, whether it be possible bias, poor reliability or limited objectives”. 19 Careful thought should be given to the cost/benefit ratio before using student ratings for personnel purposes.

We know the answer to the question of who the worst teachers are. We may as well be realistic. No-one is going to be frightened into becoming a better teacher by the threat of student ratings. Typically, the numbers from student questionnaires are used by weak managers to clothe with mystique and ceremony decisions they have already made. The time spent collecting evidence to do someone down would be more profitably spent in counselling and in working out redeployment strategies, ie in managing positively. This time will still have to be spent anyhow.

There is no way to process data to yield decisions about teaching, or anything else 20 (see Medawar, point (b) above). The evidence on improvement 21 clearly indicates that teachers who change as a result of student ratings are those who already place a fairly high value on student opinion. This is hardly surprising; but its implications are important. It cuts away one of the main supports of the argument for institution- wide systems of student rating questionnaires. Voluntary, quasi-voluntary, or compulsory use of diagnostic questionnaires is unlikely to encourage change in teachers who do not take student views seriously. Lecturers who feel anxious about their teaching — perhaps because they feel under pressure to do it better, perhaps because they know they do it badly — are the least likely to change. Evaluation of teaching is often seen as an end in itself by administrators; this is consistent with the accountability rationale for appraisal. But if the aim of evaluation is improvement in teaching, then in some cases less evaluation would lead to better student learning. 22

This is a delicate issue of professional standards. There are many invalid questionnaires and questionnaire items devised by or issued with the knowledge of Australian and British educational development staff in regular use for making personnel decisions. It would be invidious to quote instances here; Medawar’s final sentence in the extract above is apposite. The most common errors are to ask face-invalid questions (eg those that students do not have the information to answer, or which are irrelevant to teaching performance), to conflate stylistic and quality measures, to confuse the collection of student ratings for personnel purposes with their use for diagnostic feedback, to become seduced by the illusory power that data-banks and numbers offer, and simply to forget that the primary purpose of using questionnaires is to improve teaching. They are a means, not an end.

In 1989, the Dean of Melbourne University’s Science Faculty described the proper focus of science education as teaching students the joy of understanding the world around them. 23 In his lecture he criticised what he described as the “economic rationalist” view of science education — the production of a highly skilled utilitarian product at the lowest cost. Whether basic or strategic, science to this scientist — who is no stranger to applied work — was fundamentally about unmeasurables such as the sharing of knowledge and the love of synthesizing problems. Its intrinsic ends dominated. He asserted that young people instinctively recognised this focus; the teachers’ task was to maintain their interest, not jeopardise it.

In the first part of this article I argued that good teaching in higher education shared very similar qualities to these. They include a desire to share the excitement and delight of practising one’s discipline with others, a desire to help; a desire to get better at teaching through, among other things, listening to students; and an ability to see these activities as being their own rewards. However unfashionable these beliefs may be today, no-one may fairly call them “unrealistic”. Like science, teaching in higher education is fundamentally concerned with unmeasurables: no student rating form can capture the joy of helping someone to understand. How can we encourage lecturers in higher education to enjoy teaching and the sense of achievement that doing it well brings?

Any strategy for changing teaching depends on an explicit or implicit theory of learning. As we have seen, the current staff appraisal strategy is based on a crude motivational model; its central proposition is that rewards and punishments suitably distributed lead to changes in teachers’ behaviour. Fear and anxiety undoubtedly motivate people, and so does the perception of extrinsic reward. But it hardly needs saying that to base a system of improving teaching on a hollow theory like this will not do. It ignores so much of the what we know about effective teaching and learning.

From a somewhat more sophisticated theory of learning as a process of changing the way we understand aspects of the world around us may be derived a different proposition. It is that changing teachers’ strategies depends on changing the environment in which they work in order to encourage them to undertake a process of learning. The problem then resolves to which process of learning and which environment.

I believe there are three related kinds of learning involved. The first kind is constant development of one’s own understanding of the subject being taught: it implies professional development, scholarship and research in the subject. If a member of academic staff in higher education is to be motivated to teach well, he or she must believe in what is being taught and want to teach it for its own sake. As this is often what brings a person into a higher education career in the first place — a love of learning — a key task of good institutional management is to maintain that interest.

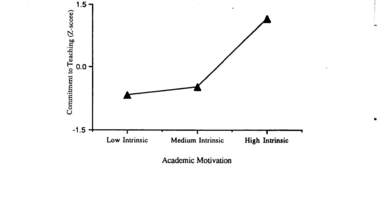

A recent study of Australian academics’ attitudes to teaching and research 24 provides a fascinating confirmation of this connection between good teaching and a commitment to the subject being taught. We asked lecturers about their attitudes to teaching; among the items on the questionnaire were ones which are known to be empirically associated with students’ perceptions of good teaching such as “I go out of my way to help students with their study problems”. Teachers who agree with items such as this one are more likely to be perceived as good teachers by their students and more likely to encourage students to use deep approaches to learning. 25 In the present study, these good teachers were highly intrinsically motivated; they agreed with statements such as “I find that academic study gives me a feeling of deep personal commitment” and “I become increasingly absorbed in my academic work the more I do” (see Figure 2). A corollary of this result, important in the context of performance appraisal debate, is that increasing the pressure on academics to perform and decreasing their intrinsic rewards will probably make the quality of their teaching worse.

FIGURE 2

Effect of Intrinsic Academic Motivation on Commitment to Teaching

The second and third sorts of teacher learning are described in more detail elsewhere. 26 They are:

• Understanding the ways in which students understand and misunderstand the subject matter that you are teaching them (which implies inquiry into how specific subject matter is comprehended, together with a desire and an ability to use the results of tests and assignments to change one’s teaching so that it more accurately addresses the errors and misconceptions of students); • Understanding the ways students interpret your requirements. This implies a persistent sensitivity to differences between how students actually perceive your teaching and how you would like them to perceive it. Excellence in teaching demands unremitting attention to activities which increase the probability that students will adopt deep approaches to learning; and it implies being prepared to alter one’s behaviour in response to new problems and new challenges.

These represent the evaluation of teaching as it has previously been defined: the development of an awareness of the effects of one’s educational practices on student learning. I have no doubt that lecturers who think about teaching in this way not only work harder at teaching but also gain more satisfaction from it.

We now reach a pivotal point in the argument for how to use evaluation to support learning. It has been suggested that the ideology of staff appraisal draws overwhelmingly on unsophisticated conceptions of teaching and learning. In particular, it adopts an additive model of improvement, it assumes a trivially simple association between motivation and change, and it implies an approach to staff development which is focused purely on enhancing individual teaching skills.

Here accountability through appraisal and the educational theory of improvement meet head on. They propose contradictory solutions to the problem of enhancing teaching standards. Just as more advanced conceptions of teaching immediately recognise the inappropriateness of blaming students for adopting superficial approaches to learning tasks, so more considered views of evaluation apprehend that the answer to the problem of improving teaching is unlikely to be found simply in reproaching individual teachers and offering them courses in teaching skills. Teachers must feel a need to find out about the effects of their teaching; this need must come from themselves; the skills and techniques they use should be driven by a well-developed conception of teaching.

To improve the quality of teaching, according to what we know about learning, we must operate at several different levels of the system, including the level of the institutional setting in which teachers work. 27 It is not easy to change the environment for the better; it is monumentally difficult to change individual students and teachers unless we also change their environment. It is, however, quite simple to change individuals’ reactions for the worse by ill-considered amendments to their educational environment, as the research into the correlates of surface approaches to learning so plainly shows. 28 Cynical messages about what will and will not be rewarded in assessments, creating excessive anxiety, and a perceived emphasis on recall of detail and trivial procedures: all these conduce to superficial approaches. Unless our aim is to produce the corps of efficient pedants and dullards that Whitehead dreaded, these aspects of evaluation must at all costs be avoided in any assessment either of learning or of teaching performance.

Our path then becomes quite clear: we should adapt exactly those lessons we have learned from research into effective teaching to the job of making teaching better. This means we have to do something which is essentially different from the current appraisal methodology. We should:

I shall now consider each of these propositions in more detail.

One of the more enfeebling aspects our educational system is its tendency to overemphasize rivalry between individuals at the expense of cooperation between them. The effects of this aspect of the context of learning would be amusing if they were not so serious in their consequences: teachers acting as security guards in examinations, student selection decisions based on differences smaller than the error of the test, proposals to rate academics on a scale of 1–10 in their appraisal interviews, examination howlers, and many others.

The ideology of staff appraisal presents a stubbornly individualistic and competitive view of excellence in teaching. This is not unexpected, considering that appraisal is concerned with individual employees’ performance and compliance to organisational goals, and usually with inter-employee competition. Good teaching is seen in this model to be a quality which inheres solely in individual teachers; accordingly, they should be encouraged to contend with each other in order to get better.

This is a bleakly unworkable view of education and its improvement. It smacks of the bullying aggression that tries to mask insecurity — the very last quality our teachers need in their supervisors. A more practical approach would be to focus on good teaching rather than good teachers. There are many examples in the literature, in anecdote, and in my personal experience of how course groups, departments and faculties have worked together as teams to produce better teaching and learning. Changing how we think about teaching is more than changing individual teachers. Conceptions of teaching are “relational”: they describe ways of conceptualizing phenomena, not things inside thinkers’ heads. It is quite meaningful to speak of changes in conceptions of teaching in the context of a course or department. A problem-based curriculum represents a different way of thinking about teaching and learning from a traditional one, for instance.

In my own educational development work in universities and polytechnics, I have found it very hard indeed to improve individual teachers’ skills in a lasting way. I have handed out many quick fixes, but my success stories are not only few and far between — they owe much more to the initiative of the individuals involved than to me. I often just happened to be around when they were doing rather exciting things.

For every case of a single teacher who has become a genuinely better teacher as a result of participating as an individual in educational development activities, I can cite a dozen cases of courses and departments who have changed their practices for the better. Working at department level, especially in large first year courses, is by any standards an efficient use of educational development resources. The reasons seem almost too obvious to mention. The rampant methodological individualism of the appraisal agreement ignores the crucial fact that very few teachers can be good at everything. Yet together, they may cooperate to produce something which is greater than the sum of the parts, and they will probably learn something for themselves in the process. This will not be even mildly surprising to those who have studied the literature on what makes peer teaching, problem-based learning and other activity-based methods so fruitful for producing changes in student understanding. 29

Now none of this should be taken to imply that we should discourage individual activity or that working at aggregate level is a necessary condition for supporting learning. The documented cases of individual teachers who have amended courses in quite radical ways within traditional departments, or who teach well despite unfavourable climates 30 are proof enough. (These cases incidentally show that appraisal is not a necessary condition for the development of individual excellence.) The argument is rather that we should encourage the improvement of teaching at multiple levels, in a variety of ways.

Using academic management strategies that will help teachers teach better implies showing concern for staff as teachers; creating a climate of openness, cooperation and activity rather than one of defensiveness, competition, and passivity; developing an environment in which teachers are likely to learn from each other. It is clear that managers of successful schools provide an environment in which teachers feel they can teach well because they are aware that cooperation and democratic decision-making are the norm. In these schools, teachers are not afraid to experiment with new ideas and to share their experiences with their colleagues. This is a common finding in school effectiveness studies and I have found it to apply in my own research into successful Grade 12 environments. 31 There is every reason to suppose it applies in higher education as well.

Staff appraisal is a poor substitute for more effective academic management. A short training course in appraisal techniques is a simple-minded response to the problem of better administration. Better management will require extensive education of supervisors in the characteristics of good teaching, how to recognise and reward it, and how to create the trusting environment where teachers believe in what they are doing — so that they find it both challenging and possible to improve their teaching and their students’ learning.

In particular, managers should learn to appreciate the unsophisticated view of learning and teaching which says that competitiveness is more important for learning than cooperation, and discipline more important than freedom, is an inadequate foundation for improving the quality of teaching. A curriculum for a course designed to help heads of departments manage for excellence in teaching might well include among its set texts AN Whitehead’s splendid Aims of Education and Other Essays. 32 There the stories of the essential tension between discipline and freedom in education, and the excitement of imaginative university teaching unfettered by trivial regulation, are wonderfully told.

Heads of departments will need to become familiar with the extensive literature on this and similar topics, and to build on this knowledge base, recognising always that in higher education most of the motivation to teach well comes from students, colleagues and within, rather than from external sources. Academic managers, in one phrase, must learn to manage like a good teacher teachers. 33

Staff development units are the obvious base for this kind of education; whether all of them are equipped to carry out the task is capable of being questioned.

Demands for greater accountability in education will not disappear: the educational problem that policy-makers and institutional managers have yet to face is how to demonstrate that higher education is accountable while (1) not reducing quality and (2), ideally, using accountability processes to enhance quality. We may take it as obvious that being accountable means focusing on different levels of aggregation, and particularly on the level of institutions and academic units, which is the level addressed by performance indicators (PIs). 34 PIs derive from the same pressures for accountability as staff appraisal, but their origin in theories of resource allocation and their focus on aggregates fit them better for the task of linking judgements and development. In particular, they are less threatening to the majority of academic staff and they have the potential to encourage change at institution and department level. PIs of teaching and the composition of the student body certainly provide plenty of evidence of accountability: they can show, for example, an institution’s progress towards access and equity goals, and provide information about completion rates. The technology is now available to measure teaching quality directly using student (or graduate) responses. 35 Improving the process of individual staff assessment entails different and more elaborate strategies, including the use of more valid data collection methods, the education of managers, and techniques for maintaining distance between developmental work and judgements about quality.

The single most serious negative consequence of the use of any method for assessing teaching quality is that the measure may become the definition of success: this leads to a distortion of the education system as members of staff and institutions strive to achieve favourable appraisals or high scores on the indicator, and neglect educationally valuable aims in the process.

This problem is common to performance indicators and the assessment of individual staff. It is not evident that those members of British and Australian higher education institutions whose responsibilities embrace academic staff development carry enough weight to encourage institutional management to respond to accountability demands in educationally valid ways. Many of these personnel have effectively been emasculated as educators by being appointed to administrative positions rather than academic ones. It seems that some other mechanism for improving educational accountability is needed. The results of teaching PIs might be applied most effectively, with the fewest negative consequences, and that the arrangements both for staff performance assessment and the process of diagnostic evaluation would be made more genuinely educational, if a central organisation were charged with the responsibility for monitoring institutions’ evaluative procedures.

What would an academic quality assurance organisation ideally do? Let us first be clear about what it should not do. A quality assurance unit should not directly review the quality of teaching and curriculum in the various institutions. It should not consist of the intrusive corps of quality inspectors “armed with doubtful instruments” criticised by Paul Bourke. 36 Recognising that any real changes in teaching standards must come from within institutions themselves, it would:

• act as an enlightened but stem critic of how evaluation, review and appraisal is carried out within each university, polytechnic and college; • help institutions to make their own quality judgements based on available evidence: • examine the educational impact on institutions’ evaluative practices and advise how to improve them so that they were more likely to achieve educationally desirable goals; • look carefully at institutional mechanisms for using PI data to improve the standard of teaching, and monitor the changes to curricula and teaching they make in response; • encourage best practice in teaching and evaluation by comparing the effectiveness of existing procedures in the context of other institutions’ methods; • offer constructive suggestions in the areas of, for example, education managers to promote effective teaching, and maintaining academic standards in the face of diminishing resources; • identify needs for continuing educational development unit staff and help implement programmes designed to maximise their impact on quality.

It is too early to say whether the universities’ Academic Audit Unit in the United Kingdom will fulfil these functions satisfactorily. The first signs are not overly encouraging. The Unit’s origins in the CVCP’s review of external examining suggest that its role in monitoring evaluation and appraisal of staff may take second place to the maintenance of “standards” in the student body. The perils of assessing teaching performance by, proxy — using the outcomes of student learning rather than the quality of the teaching — are too well known to need rehearsal here. The morality as well as the validity of such practices in questionable. 37 The pronouncements of the Unit’s foundation director (who happens to be an administrator, not an educator) about teaching quality suggest a narrow conception of teaching as skilled communication of expert knowledge within conventional classes. 38

The establishment of a quality assurance unit for Australian higher education, based in a tertiary institution and staffed by a small permanent directorate plus seconded staff would require a considerable investment. The UK unit has a budget over $1,000,000 a year. Higher education can learn a valuable lesson from industry in this respect. As the managers of industrial processes will tell you, quality assurance does not cost, it pays. If we are serious both about educational standards and the improvement of teaching and learning in Australian higher education, can we afford not to make the investment?

Earlier in this article I quoted some short passages from a minor education classic, Sawyer’s Mathematician’s Delight. What Sawyer says about bad teaching applies just as surely to bad evaluation and bad staff development. It neither touches the imagination nor enhances the ability to reason. It focuses on a procession of signs and meaningless rules rather than on the things those rules and signs are supposed to signify. And not the least of its shortcomings is that it is deadly dull.

I have tried to argue that in order to use evaluation to improve teaching, it is necessary to bear in mind one elementary principle: that encouraging students to learn and motivating teachers to change involve identical strategies. Although it is unintelligent to employ methods for improving teaching which we know are detrimental to student learning, their use is understandable in the context of timid or educationally naive responses to pressures for accountability. It seems that many people, including the makers of high institutional policy, have much to learn about education and the measurement of teaching standards. We should be more active in helping them to learn.

The greatest tragedy of the present climate of appraisal is that it prevents the application of our understanding of the educational process to improving learning. We have enough knowledge of the nature of good teaching in higher education to alter the quality of learning out of all recognition. What is needed is the institutional spirit and the political commitment to apply these principles. Several practical alternatives have been suggested, based on educational theory and common sense — which fortunately concur in this case — to some current practices of appraisal and evaluation. Underlying all the criticisms and suggestions is, I hope, a conception of teaching and learning as a reflective, active and pleasurable process. There can be no excellent teaching or learning unless teachers and learners delight in what they are doing.

[*] Centre for the Study of Higher Education, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia. This article is based on a keynote paper prepared for the Annual Conference of the Higher Education Research & Development Society of Australasia, held at Griffith University, 6–9 July 1990. The text of the keynote paper appeared in the Society’s conference proceedings, Research & Development in Higher Education Volume 13. 1 am most grateful to Elaine Martin for her valuable comments on earlier drafts.

© 1991. (1990–91) 2 Legal Educ Review 149.

[1] KE Eble, The Craft of Teaching (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1988); JB Biggs, Approaches to the Enhancement of Tertiary Teaching (1989) 8 Higher Educ Research & Development 7.

[2] JB Biggs, ‘Teaching for Better Learning’ (1990–91) 2 Legal Educ Review 133

[3] WW Sawyer, Mathematician’s Delight (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1943).

[4] Id at 9.

[5] P Ramsden and A Dodds, Improving Teaching and Courses: A Guide to Education (University of Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Higher Education, 1989).

[6] J Nisbet, Staff and Standards in GC Moodie (ed) Standards and Criteria in Higher Education, (Guildford: SRHE and NFER-Nelson, 1986).

[7] A Hartnett and M Naish, The Sleep of Reason Breeds Monsters: The Birth of a Statutory Curriculum in England and Wales (1990) 22 Journal of Curriculum Studies 1.

[8] C Pollitt, The Politics of Performance Assessment: Lessons for Higher Education? (1987) 12 Stud in Higher Educ 87.

[9] Hartnett and Naish, supra note 8 at 12.

[10] See for example, A Thomas, Further Education Staff Appraisal: What Teachers Think, (1989) 14 Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 149.

[11] See Biggs, supra note 2 for a description of different conceptions of teaching in higher education.

[12] The single more egregious example is the institution of prizes for good teachers.

[13] Ramsden & Dodds, supra note 5.

[14] JA Centra, The How and Why of Evaluating Teaching (1980) 71 Engineering Educ 205.

[15] WJ McKeachie, The Role of Faculty Evaluation in Enhancing College Teaching (1983) 63 National Forum 37.

[16] PB Medwar, Unnatural Science New York Review of Books Feb 3,1977 at 13–18.

[17] M Scriven, The Validity of Student Ratings, Annual Conference, Higher Education Research & Development Society of Australia, Sept 1987, Curtin University of Technology, Perth.

[18] There are numerous ways to cheat at tests that are as uncontrolled as the rating questionnaires used in Australian and British higher education. Techniques of cheating, well-developed in North America (which also has the worst as well as the best student rating practices), are easily obtainable from several sources.

[19] Centra, supra note 14 at 209.

[20] See Medawar, supra note 16.

[21] Centra, supra note 14 at 176.

[22] McKeachie, supra note 15.

[23] T Healy, “Labor’s higher education reforms: What will science look like by 1995?” Centre for the Study of Higher Education (University of Melbourne) Spring Lectures on Higher Education, 1989.

[24] These findings are from a continuing project funded by the Australian Research Council (Principal investigators Ingrid Moses and Paul Ramsden).

[25] See P Ramsden, Study Processes in Grade 12 Environment in BJ Fraser & HJ Walberg (eds), Educational Environments (Oxford: Pergamon, 1991) for evidence of this connection.

[26] P Ramsden, Studying Learning: Improving Teaching in P Ramsden (ed) Improving Learning: New Perspectives (London: Kogan Page, 1988); P Ramsden, What Does It Take To Improve Medical Students’ Learning? in J Balla, M Gibson and H Chang (eds), Learning in Medical School: A Model For The Clinical Professions (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press, 1989).

[27] See also Biggs, supra note 2.

[28] Biggs, supra note 1; T J Crooks, The Impact of Classroom Evaluation Practices on Students (1988) Rev of Educ Research 438; F Marton, D Hounsell and NJ Entwistle (eds), The Experience of Learning (Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1984).

[29] See Biggs, supra note 2.

[30] See for example, A Leftwich, Room for Manoeuvre: A Report on Experiments in Alternative Teaching and Learning Methods in Politics (1987) 12 Stud in Higher Educ 311; N Eizenberg, Approaches to learning Anatomy in P Ramsden (ed) Improving Learning: New Perspectives (London: Kogan Page, 1988); K Robin and BJ Fraser, Investigations of exemplary Practice in High School Science and Mathematics (1988) 32 Austl J of Educ 75.

[31] Ramsden, supra note 25.

[32] A N Whitehead, Aims of Education and Other Essays (New York: Free Press, 1967).

[33] See Eble, supra note 1, at 192.

[34] It is helpful to distinguish between performance indicators, which are measures at aggregate level typically associated with decisions about resource allocation; and staff performance appraisal, which is focused on individual academics and concerned with matching organisational and personnel goals.

[35] P Ramsden, Report to the Higher Education Performance Indicators Project on the Course Experience Questionnaire Trial (Wollongong: Centre for Technology and Social Change, 1990).

[36] P Bourke, Quality Measures in Universities Commonwealth Tertiary Education Commission 1986).

[37] M Warnock, A Common Policy for Education (Oxford: OUP, 1989).

[38] See R Yarde, Someone To Watch Over You, Times Higher Education Supplement July 6,1990.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LegEdRev/1991/9.html