Legal Education Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal Education Review |

|

SOCIAL STRUCTURE, EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT AND ADMISSION

TO LAW SCHOOL

ALEX ZIEGERT*

INTRODUCTION1

“From the moment you are born, ...”, a

recent TV advertisement tells us, “... the odds are stacked against

you!”.

The advertisement then goes on to demonstrate how minimal the

chances are to incur certain favourable life-events. It suggests that,

rather

than trying hard, it is better to play the lottery as a way of overcoming the

adversities of everyday life. However doubtful

the actuarial calculations may be

which are used in the advertisement, it makes a forceful point: what we expect

to be, and what

— in a democratic society — is promised to be,

apparent equality of opportunities turns out as a maze of barriers, dead-ends

and capricious events. What the lottery advertisement implies, but what the

liberalist democratic formula fails to tell us generally,

is that the equal

chances provided by the social life of any society are not only as bad as, but

in fact worse, than chances provided

by a lottery. Different from the lottery,

the “odds” in real life are systematically “loaded when equal

access

is attempted to health, wealth, power and status, or to whatever seems

worth achieving in a given society. What appears to be chance,

or at best fate

and providence, is evidently the invisible hand of social structure, tipping

the scales consistently in the direction

of how that structure itself operates

at any given time in the life of an individual from the moment the individual is

born.

This observation is, of course, hardly original. However, it is

important to keep it in mind when one wants to assess the practices

of admitting

access to tertiary education — a resource in all modem societies —

and when one wants to design policies

which are aimed at reforming the access to

law schools — a formidable resource in all societies which follow the

common law

tradition. Viewed from the aspect of the complex and pervasive

historically entrenched social structure and social processes, to

change

admission practices effectively is an awesome task. Admission policies which are

advocated as “new” can be safely

assumed to be merely the

administration of more of the same unless enough leverage can be mobilised to

unsettle the systematic bias

of social structure and to neutralise some of the

thoroughly debilitating effects of its invisible hand. Obviously, to attain such

leverage is beyond the scope of individual universities and/or their law

faculties, and it is outside the work practices which are

employed in the

admission of students. We must assume that whatever universities can or will do

necessarily amounts to not much more

than tinkering with the systematic bias of

social structure.

There is now compelling evidence that this is in fact the

only result which universities have achieved in a fairly long history of

admission policy reforms in the tertiary education sector in Australia. There is

also increasing consensual knowledge2 that the even

more comprehensive and better coordinated actions and programmes on state or

national government level, which were

designed to affect the social mix of

undergraduates in Australia and overseas had no, or only a limited

effect.3 Often, the small effect achieved by incisive

single-measure government intervention4 or by broad

equal opportunity policies is counteracted by subsequent changes in admission

policies5 which in turn make access to higher education

even more highly competitive. Any gains made by these policies are whittled away

by

the social forces at work on a deeper and more complex level of a given

society.6

It is important to note, however, that

this bleak picture changes somewhat where specific target groups are concerned.

Here more narrowly

tailored government programmes can be shown to be reasonably

successful.7 Special programmes of this kind remain

promising but are, by definition, limited in their outcomes.

Finally, a

third and different case in the history of admission practices in educational

organisations in general and, especially,

in the tertiary education sector, is

the case of women. It provides us with the evidence that the dynamics of the

invisible hand

of social structure can be forced over time even if ever so

slightly. Women, coming from a position of practical exclusion from higher

education, have achieved, at least nominally, equal access to higher education

with men, even if, as yet, actual admission practices

are still quite

patchy.8 As the following discussion will show, this

more complex change in admission practices but, more importantly, in educational

attitudes

towards girls and women generally, has had and still has crucial

consequences for structural change in a given society. This potential

for change

is related to the pivotal role women have in societies as mothers who are,

rather than fathers, effectively in charge

of the socialisation of their

children. This is generally the case in all societies but plays a particularly

important role in the

educational programmes of societies which are on the way

to become modern, industrial societies and possibly post-modem

societies.9 It appears, then, that the educational

attainment of mothers is one of the most powerful single predictor variables for

structural

change and for intergenerational transmission in societies. A review

of admission policies has to address this observation.

In view of the

complex operation of social structure and social process, and their combined

effects on the work practices of educational

organisations on all levels

(family, primary education, secondary education, and tertiary education), a

review of admission practices

cannot be content to assess admission to law

school as a single, independent event but must attempt to link this event to the

socio-historical

context in which it occurs and in which a particular

educational organisation operates. This link provides the parameters for

educational

operations on all levels, from childhood to adulthood, on which

selection occurs. The following discussion is a report of an attempt

to draw

such a link. This attempt is limited by the specific objectives of the task set

for the researchers.10 However, neither the explorative

nature of such a study nor its necessary limitations should preclude that the

evaluation and discussion

of results are attempted with a substantial and

explicit connection between theory and research.11 The

study, as presented in this report, attempts to demonstrate such a connection.

It introduces a general model of the selective

dynamics of social structure and

social process as they can be seen to bear on educational operations, including

admission practices,

and as they can be shown to apply to New South Wales and to

the work practices of the Faculty of Law of the University of Sydney

in

particular. This model is based on the theory of operationally closed

systems12 described in section 2. Such a model informs

us what kind of data are needed and how they can be collected (described in

section

3) and it directs the way in which the collected empirical material can

be understood (interpreted) and presented in the following

discussion (section

4). Though such an approach uses the collected data to the best knowledge of the

researchers, it is obviously

still not the full story of admission to law

school.

THE PRACTICE OF LAW STUDENT SELECTION IN NEW SOUTH WALES — A THEORETICAL MODEL

The concept of law school intake (admission), as

envisaged here, starts from the assumption of a highly stratified concatenation

of

selection processes which affect every individual student on a number of

steps in the student’s life-career. The result of

these selection

processes is effectively, as far as our law students are concerned, that they

are eventually accepted as law students:

they have “made it”.

However, seen against the background of the population at large, the chances of

a new-born child

to be eventually admitted to law school are rather remote.

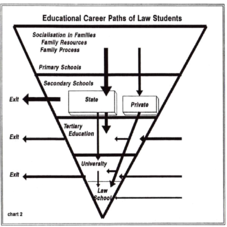

We find, then, a systematic funnelling process represented in the

life-careers of law-students as compared with the life-careers of

young adults

at large. This process is made up by a great number of multi-level selection

processes which, in the sociological sense,

are constituted by the interplay of

socialisation and education.13 This interplay is

orchestrated by social structure14 over time, both in

the Australian society at large and in the society of NSW in particular. The

picture which we gain from this sociological

view on law student selection as

practised by a particular law school (Sydney University Law School) appears to

be that of a funnel

which has numerous filter levels. Each of these filters

allows for only a minority of individuals to pass through to subsequent levels

and retains the rest. Evidently, those individuals who pass each level to the

next one possess particular (highly selected) personal

characteristics and they

share these characteristics with all those others who have also passed; and, the

more filters these individuals

pass, the more those who pass share personal

characteristics with each other.15 Seen from the

vantage point of the eventually successful admission to law school, and with

hindsight, all law students share the

experience of such a rather long, and in

fact — when compared with other university studies — one of the

longest possible,

educational career-paths. The high homogeneity of the personal

profiles of the students in this group should not come as a surprise.

The most

remarkable feature of this homogeneous group is the over-representation of

individuals who come from families with high

socio-economic status in a given

society, and who have had — on their long march through the education

system — sufficient

time and specific support in these family environments

to learn how to become educated. This feature becomes more prominent with

each

step on the career-path in the educational system. In short, our model suggests

that institutionalised education is not a simple

hand-out of knowledge to

particular individuals but rather a series of selective operations by families,

educational organisations

and the economic system to which individuals adjust

skilfully by socialisation. The overall outcome of education is that a specific

group of individuals acquire a particular set of social skills which affect the

way in which those individuals operate their cognitive

manoeuvres of

self-concept maintenance in order to achieve individually perceived goals which

are at the socio-cultural and socio-economic

disposition of society at large.

A comprehensive account of the complexity of the historical conditions for

educational outcomes in NSW is beyond the scope of our

study but such historical

conditioning must be kept in mind. It refers to a small, geographically

relatively isolated society which

is demographically concentrated in the State

capital, resulting in an extremely low, degree of mobility but a high degree of

interaction

between the local elites. This historical framework of a small

society in a large geographical space is basically a provincial one

and one

which is characterised by economic vulnerability.16

Here, the society needs to respond to wider international developments through

the adjustive operations of the economic and education

systems. Historically, it

appears that in Australia and NSW the education system has been the more open

and resilient one and that

the economic system has been the more, protectively,

closed and vulnerable one. Thus, while Australia has never developed a strong

secondary, industrial sector — and in this sense has never become an

industrial society in the full (socio-economic) sense

of the term — it has

become a modern developed society by the responsiveness of its highly

differentiated education system.

This education system provides the necessary

cultural capital to drive a relatively strong tertiary industry (services)

sector in

a vibrant multicultural environment. In Australia, as anywhere else in

modern Western societies, the crucial measure for development,

then, is the

capacity to relate the operations of the economic system and of the education

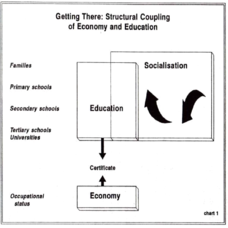

system meaningfully to each other. Such

a meaningful relationship between the

operations of different systems can be understood in the terms of structural

coupling.17 This means, in the case of a structural

coupling of the economic and education systems. that the operations in each

system condition

each other through the use of references to certification

(certificates, degrees and diplomas). The reference made to certification

by

both the education system and the economic system means that access to economic

resources (positions of occupational status and/or

wealth) in NSW, as anywhere

else in modem societies, depends increasingly, and often exclusively, on the

attainment of high levels

of formal education rather than on a traditional

recognition of practical skills through non-certified educational operations in

the economic system itself (for example by training “in house” or

“on the job”). By issuing certificates

and by a recognition of

issued certificates, the economic and the education systems condition each other

externally and they co-ordinate

their respective autonomous internal operations

by referring to, and occasionally quarrelling over18

certificates.

A good example for this important historical step of the mutual recognition

of the economic and educational systems in the structural

coupling through

references to certification is the change in the approach to recruitment for the

legal profession in Australia and

in NSW. Here, selection of recruits to the

legal profession has turned from a regime of

apprenticeship19 and in-house approbation in the

position of the articled clerk to a nearly exclusive regime of university

education or tertiary-education-styled

education in colleges of advanced

education, college of law, joint admission board courses and examinations,

modelled after university

courses and administered by university staff.

The

complex pattern of change by mutual connectedness of education and economics has

had a profound effect on the organisation of

formal education. Educational

careers have become longer, curricula more complex and more varied. Moreover,

formal education has

become more comprehensive for the entire population, and in

turn, access to educational organisations, especially their higher levels,

has

become more competitive.20 With every additional rung

in the ladder of formal education, that is, a further differentiation of the

education system, numbers

of intake increase but also selectivity overall

increases. Rather than to equip individuals for coping with modem society, this

process

of differentiation has the pervasive effect of sequestering

(classifying) — often irretrievably — the certified winners

and

losers in social life.

Conveniently simplified, we can distinguish five major levels of the

educational careers of law students in NSW The socialisation

in a family home

and in institutions (like kindergarten, primary schools) supporting

socialisation in primary groups (families).

On this basic level, education is

not highly formalised. This lack of formalisation, accounts for both the

strength and the failures

of education on this level. A major problem is that

there is no formal exit from the educational system on this level; educational

success is exclusively dependent on the socialisation processes which go on in

the privacy of family homes and/or in other primary

group

environments.21 Such family or primary group

performances are, in turn, crucially dependent on the organisational quality of

the unit, measured in

terms of their resources (e.g. socio-economic status and

educational attainment of members) and of the on-going processes in the

unit for

example supportiveness, communication, interaction, and liaison with external

environment. Resources and process together

provide for the human development

and for the socialisation of social competence of children and

adolescents,22 but also of the adults in such units.

Evidently, educational careers are formed on this level; omissions and

commissions perpetrated on individuals on this level are highly

formative for

the protection and maintenance of self-concept and so for the pathways which the

life-course of individuals will take.23 Because

socialisation does not allow for exits while education

does,24 the most distressing feature of education at

this level of low formalisation is that the mode of selection of the education

system,

and particularly, a number of specific “exits” from the

education system, are not easily visible and/or are not conceptualised

as such.

Rather, classifications of “success”, “failure”, and

“dropping out” are hiding here

in the private niches of family life

as so-called apathy, disinterest, retardation, unruliness, dyslexia, or as

diagnosed psychosomatic,

neurotic and psychotic disorders. Nevertheless, the

labels with which are assigned to individuals here, stick with the respective

individuals through informing their self concepts; they learn to see themselves

as failures in an early age, and this will be the

most distinct feature of the

life-careers of such individuals.

The socialisation and education in

secondary schools. In becoming more formalised, the selectiveness of the

education system becomes more conspicuous. With this higher degree of

organisational

formalisation, also exits from the educational system are

formalised (certified) on this level. Internally, the higher degree of

formalisation allows for more differentiation (specialisation) of the system; it

can fast-track some individuals for further advancement

and discourage others

from staying on. Students emerge from secondary schools as firmly classified

candidates for economic roles.

However, the selective effect of the official

classification of educational attainment is also related to the way in which it

is

valued by the respective individual on the base of personal and family

values. Such values allow, for instance, to view earning money

forming a family

or just dropping out of school as superior to the long term goal of reaching

high levels of educational attainment

with diffuse career perspectives and

distant earning capacities.

A special feature of the education system in NSW

on this level is the segmented operation of public (state) and private schools,

and

especially secondary schools.25 This segmentation

of the education system disperses scarce public resources further, and it

increases the selectiveness of the education

system on this level by introducing

further rungs. While state schools have to cope with a majority of mandatory

students in often

adverse educative environments, private schools can capitalise

for their educational operations on the formative effects of family

resources

and family process provided by those students who are set to have the longest

educational career-paths: students from private

schools spend the longest time

of all students in the state in the education system.

Our model suggests,

then, that while state secondary schools have large numbers of students, they

also have large numbers of “drop

outs” and of students who will

leave the education system as certified leavers on this level (year 10 school

certificate).

Comparatively few of these students will stay on in the education

system to go to university and even fewer will be admitted to law

school. In

contrast, private schools deal only with small but highly selected populations.

Only very few students here will exit

the education system before reaching

university, and many of them will be admitted to law school.

The

socialisation and education in tertiary education institutions. With the

increased differentiation of the economic system, the importance of the

education system grows and the pressure on the internal

differentiation of

universities intensifies. The result is a further spread of university

sub-systems (schools, faculties, departments,

amalgamations) and their

competition for resources by further differentiation of certification through

more specialised degrees or

diplomas.

With the increased internal

differentiation of universities and tertiary education institutions, the

tertiary level also becomes an

important re-entry level for many individuals who

have left the education system at earlier stages and who decide to upgrade their

chances for a better access to the economic system by higher levels of

educational attainment.

As far as the present practice of law school

admission is concerned, this group of re-entry students have to compete with the

systemicly

better positioned “educational stayers” from the

secondary schools, and especially those from the private secondary schools.

The socialisation and education in universities. The demand for

highest level education certification has expanded the scope and variety of

university activities. This has meant

a further differentiation of certificate

levels in grades of degrees, number of degree levels, and the specialisation of

degrees

and diplomas. Each of these differentiation levels, in turn, must be

seen to function predominantly as a selective rung in the ladder

of educational

careers. While the educational value of these differentiations of certification

remains doubtful,26 provide clearly the bonus of

additional or cumulative certification for individuals and organisations. With

that, they also provide

a further step to prevent or facilitate access to law

school in those cases where direct access from secondary school is not possible.

The socialisation and education in law schools. In spite of the, then

rather late, incorporation of legal education in universities, the law school in

the Anglo-American setting

has maintained a separateness from university

operations in general. This applies also to the modem version of Anglo- American

law

school teaching and research under, oddly enough, the auspices of

interdisciplinarity and contextuality. No other field of academic

endeavour

maintains so tenaciously institutional generality and is so poorly

organisationally specialised (differentiated) as legal education at law school.

This peculiar historical role of law schools refers to a more specific and

direct structural coupling with the economic system which

can be found in the

role that the legal profession plays in the history of common law. This direct

link between the legal profession

and law school overrides, in many respects,

the structural coupling of education and economics which applies generally to

universities

and it determines the higher selectivity of law schools as compared

with admission to university in general.

This higher selectivity of law

schools is expressed in features such as more restricted admission quota,

special provisions for combined

degrees and an implicit tendency toward graduate

schools which are not present in other university faculties.27

In this crucial aspect of highest educational selectivity, then, law

schools exhibit the same features as private secondary schools.

Both, private

secondary schools and law schools can present the unique structural position

which they hold in the education system

as “producing excellence”.

Their higher selectivity allows them to capitalise on refined selection

procedures and on elaborate educational classification schemes.

These

classification schemes mandate longer than average educational career paths and

strong family commitments to those students

who are set up to stay on those

longer career paths. It is, then, not surprising to find in law schools

predominantly those students

who also populate the private secondary schools.

Taken together, all rungs in the ladder to educational attainment have the

effect that the educational career which leads to a first

law degree is one of

the longest in the educational system. In turn, the student population so

selected is, in the end, one of the

most homogeneous student populations in

universities.28 However, this homogeneity does not

necessarily relate exclusively to socio-economic (class) criteria or academic

achievement criteria

(high HSC/TER) scores. Rather our model suggests that the

homogeneity of the law student population at Sydney University is the result

of

the perseverance on a rather long educational path as effected by a combination

of favourable family background variables, among

them also the socio-economic

status of families. In this respect, addressing only the warped social mix of

the law student population

means to overlook the more complex historical problem

why some families promote the acquisition of cultural capital in their children

while others do not and how the pathways of social mobility may look like which

lead from being born in the latter family- type to

constituting a family of the

former family-type as an adult who can intergenerationally transmit the value of

education to her children.

The research project, commissioned by the Faculty

of Law of the University of Sydney, had the objective of assessing the effects

of

current admission practices as reflected in the profile of admitted law

students. Based on the model of law student selection discussed

above, a

longitudinal study would have been the preferred approach. Such a longitudinal

assessment could have encompassed all stages

of the selection process, including

the formative family processes and also the exits from the selection process of

those students

who either do not seek or who fail to gain entry to law school.

However, due to time constraints this was not a feasible option.

Instead and by

convenience, our research concentrates on the later stages of the selection

process and relies exclusively on the

self-reports of law students. The

deficiencies which result from this approach will be discussed in the next

section.

METHODOLOGY

The collection of data for this study was conducted in two phases:29

The rationale for constituting the samples in this way was to survey two substantially large student populations who differ with respect to:

Table 1: Students Who Entered Law as a Graduate

|

SQ 7.2 WHAT WAS MAJOR AREA OF STUDY

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Arts

|

—

|

20.5

|

|

Science

|

—

|

5.2

|

|

Economics

|

—

|

4.3

|

|

Not Appl.

|

100.0

|

70.1

|

|

N

|

159.0

|

117.0

|

A further critical methodological point in the study is the use of student’s self-reports rather than, for instance, observational data. Self-reports create the methodological bias that findings reflect current perceptions of self of students, at the point of time of the report, rather than accurate (“objective”) records of past events in the educational careers of students.32 It appears, however, that this general problem in social science research is of little consequence in our study. On the one hand, faulty or falsified (“beautified”) recall by students must be considered to be minimal as far as concrete, biographical data and objective (officially recorded) events of their family backgrounds (occupational status of parents, educational attainment of parents) and educational careers (school type, degree type) are concerned. On the other hand, the reporting of students’ (perceived) self-concepts was intended because self-reports are the only access to the assessment of the experience of students. This approach is further accentuated by the complementary use of qualitative research methods. In this approach, interviews with largely open and unstructured questions were used which allowed students to elaborate on personal experiences and individual viewpoints.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The methodological dilemma that our study does not reflect adequately on processes which precede admission to law school, is particularly acute with regard to the early and most formative childhood experiences of law students. Selective processes are here set in the environment of face-to-face relations organised in primary groups, that is, mostly by family relations and, to a lesser extent and only complementary, by peer group relations. Significantly, even the law students themselves refer only rarely to these early years when talking more freely about their educational careers in the interviews. However, the effects of some fairly reliable standard variables of socialisation research33 can be discussed in the light of the results of our survey. These variables account for the distinction between family resources (educational attainment levels of parents, occupational status and work situation of parents, income levels but also network support, access to infrastructure, access to dominant culture through competence in language and culturally highly valued behavioural patterns) and family process (bonding between family members, communication, support, power/authority structures). These different sets of variables focus on interrelated but specifically differentiated outcomes of primary group socialisation. The relationship between the underlying family operations measured by the two sets of variables is, as a rule but not invariably accumulative throughout family histories, either in a positive form, that is, as benign “upward” loops, or in a negative form, that is, as vicious “downward loops. Furthermore, these family operations are also, through intergenerational transmission, accumulative through generations.34 This means that, depending on the quality of family resources and processes, individuals growing up in respective families are more or less resourceful themselves. Additionally, there is a significant probability that a person may engage in a stable interpersonal relationship, and finally form a new family with a person who commands similar levels of resourcefulness as that person. This results in the prevalent homogamic patterns where individuals with similar levels, for instance, of educational attainment or occupational status pool whatever resources they command, and where this leads to even more pronounced differences of family coping, including child rearing, between different families.

FAMILY RESOURCES

It is evident from our findings that the law students

in our samples come largely from families which have been highly successful

in

the accumulation of cultural and economic capital.35

Fathers and mothers of law students have overall, and by any count, a far higher

occupational status and a higher level of educational

attainment than fathers

and mothers in the population of Australia at large (compare Tables 2 and 3,

levels of parental educational

attainment, with Tables 4 and 5). So, the high

proportion of fathers of law students with professional occupational status

(about

25%) compares with only 14% of men with that status in the Australian

population at large.36 Conversely, only 9% of the

fathers of law students and 18% of the mothers are reported to have the status

of clerk or worker, compared

with 44% and 69% of men and women in Australia

overall who are reported to have that occupational status. Likewise, roughly 50%

of

the law students report that their fathers have attained a university degree,

and nearly the same proportion of mothers who hold

such a degree (49%) is

supported by the first year intake (19901, while only 11% of the men and 8% of

the women in work in Australia

are registered in the official statistics with

such a level of educational attainment.37 Conversely,

26% and 24% of the law students report that their fathers and mothers have

attained an educational level which is less

than a Higher School Certificate,

while 37% of the men and 43% of the women in work in Australia are reported to

have attained that

level.38

In the very few cases

where students have achieved admission to the law school in spite of the fact

that lower levels of both occupational

status and educational attainment of

parents are reported, the nominal disadvantage in these families is probably

balanced by favourable

family process, for instance, an effective network of

good relations between the members or the family which results in a highly

supportive and committed family environment. This is discussed further in

section 4.3.

Occupational Status and Level of educational attainment of

Parents. Two family-background variables are most clearly related to

structural advantage in modem Australian society. These are the father’s

occupational status and the mother’s level of educational attainment.

Findings related to these variables in our students’

self-reports support

the observation, made earlier, about resourceful family configurations in the

law student sample. Mothers in

these families are reported — when compared

to their male partners — to have achieved similarly high or even higher,

but rarely considerably lower level of educational attainment, and a lower

occupational status than that of their male partners.

Conversely, fathers in

these families are reported to have achieved a higher occupational status

— compared to their female

partners — and a similarly high but

frequently also a lower level of educational attainment than that of their

female partners.

The result of such configurations are highly favourable family

environments and it is this high level of the educational attainment

of their

mothers combined with the high occupational status of their fathers which

appears to be the crucial element in the life-careers

of those students who are

eventually admitted to law school.

Table 2: Father’s Occupation

|

SQ 10 FATHER’S OCCUPATION

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Upper Professional

|

26.1

|

24.8

|

|

Low Professional

|

3.2

|

4.3

|

|

Upper Services

|

19.1

|

19.7

|

|

Low Services

|

1.9

|

0.0

|

|

Managerial

|

21.0

|

17.1

|

|

Entrepreneurial

|

17.2

|

13.7

|

|

Worker

|

4.5

|

13.7

|

|

Other

|

7.0

|

6.8

|

|

N

|

157.0

|

117.0

|

Table 3: Mother’s Occupation

|

SQ 11 MOTHER’S OCCUPATION

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Upper Professional

|

5.1

|

3.4

|

|

Low Professional

|

10.8

|

13.4

|

|

Upper Services

|

27.4

|

23.5

|

|

Low Services

|

1.3

|

2.5

|

|

Managerial

|

5.7

|

3.4

|

|

Entrepreneurial

|

5.7

|

5.0

|

|

Worker

|

16.6

|

20.2

|

|

Other

|

27.4

|

28.6

|

|

N

|

157.0

|

119.0

|

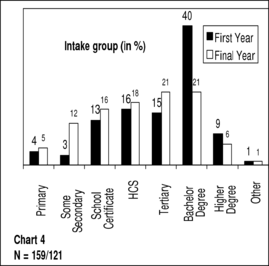

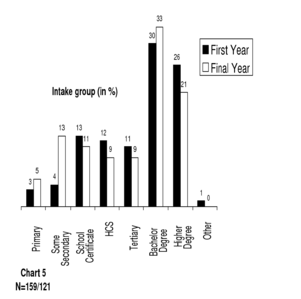

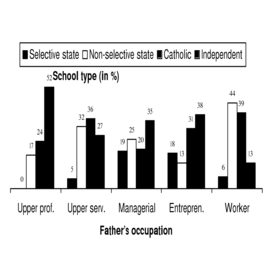

When the two different intake groups of law students (“first year” and “final year”) are compared (Table 2 and Chart 3), all higher occupational positions of the fathers of law students are more frequently reported in the later intake group (1990), with the exception of a slight reduction of reported upper public service positions of law students’ fathers, and all lower positions (lower public service, worker) are here less frequently reported. Similarly, the reported levels of educational attainment of both parents are higher (higher occurrence of higher levels/ lower occurrence of lower levels) in the mow recent intake of law students (Tables 4 and 5, Charts 4 and 5). University degrees are no longer the almost exclusive achievement of only the fathers of law students: 40% of the students of the intake in 1990 report that their mothers hold a bachelor degree and 9% report that their mothers hold a higher than bachelor degree (Chart 4). In this comparison of the different intake groups, it should be kept in mind, that the final year group of students is, as mentioned earlier, a much more varied sample as far as their admission is concerned, than the first year group where students come almost exclusively dimly from high school. However, the comparison also shows that the competition for entry has further homogenised the group of students who are eventually admitted at this stage, and that resourceful families are even more over-represented as compared with other student samples or the general population.

Table 4: Father’s Educational Attainment

|

SQ 12 FATHER’S EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Primary

|

2.5

|

5.0

|

|

Some Secondary

|

3.8

|

12.5

|

|

School Certificate

|

13.3

|

10.8

|

|

HCS

|

12.0

|

9.2

|

|

Tertiary

|

10.8

|

9.2

|

|

Bachelor Degree

|

30.4

|

32.5

|

|

Higher Degree

|

25.9

|

20.8

|

|

Other

|

1.3

|

0.0

|

|

N

|

158.0

|

120.0

|

Table 5: Mother’s Educational Attainment

|

Q 13 MOTHER’S EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Primary

|

3.8

|

5.0

|

|

Some Secondary

|

3.1

|

12.3

|

|

School Certificate

|

12.6

|

15.8

|

|

HCS

|

16.4

|

17.5

|

|

Tertiary

|

14.5

|

20.8

|

|

Bachelor Degree

|

40.3

|

20.8

|

|

Higher Degree

|

8.8

|

5.8

|

|

Other

|

0.6

|

0.8

|

|

N

|

159.0

|

120.0

|

CHART 3: Father’s Occupation

CHART4: Mother’s Educational Attainment

CHART 5: Father’s Educational Attainment

CHART 6: HSC Score by Mother’s Educational

Attainment

(in %)

5

8

4

4

28

17

2

4

13

17

24

11

8

25

26

16

18

25

20

39

5

0

10

8

Lowest

to 400

401 to 420

421 to 440

441 plus

Primary only

Some

secondary

School certif.

HS Certif.

Bachelor deg.

Higher

CHART 7: Mother’s Educational Attainment by

Father’s

Occupation

Mother’s educational

attainment

CHART 8: Mother’s Educational Attainment

by Father’s Education

As noted earlier, there is a strong and significant tendency for couples overall to increase their individual resourcefulness by homogamic marital match-making. This observation applies clearly to parents of students who are eventually admitted to law school. Here, there is not only a higher than normally distributed chance that the parents of the students hold university degrees but also a higher chance that both parents hold such a degree compared with the population at large. Our data show that:

Socio-cultural background and access to the

dominant culture. Variables which refer to a specific socio-cultural

background of an individual, such as the country of birth of the parents and

native

language are generally referred to as “ethnic issues” and are

as such not generally seen in the context of family and

individual resources.

Our theoretical framework discussed in section 2 suggests otherwise. It points

to the intimate link between

family resources, access to societal infrastructure

and access to the dominant culture. The socio-cultural background, then,

explains,

to a high degree, the resourcefulness of families of law students as a

result of a positive relation with Anglo-Saxon and/or Anglo-

Celtic Australian

language and culture (Tables 6, 7 and 8).

Our data show that an accumulation

of cultural capital has been achieved here through effective intergenerational

transmission of

cultural capital in families where the parents, and possibly

already the grandparents, were born in Australia and that the group

of these

students constitutes the overwhelming majority of law students. The next largest

group of law students come from families

who have not been born in Australia but

in other sociocultural environments which are linked to the English culture

(United Kingdom,

New Zealand).39 Compared with this

predominance of English socio-cultural patterns, other ethnic backgrounds are

insignificant among law students,

even if one takes into account the quite

substantial number of students in the first year who report an Asian family

background (compare

Tables 6 and 7). A closer assessment of the language which

is primarily spoken in these families reveals here also a dominance of

English

(Table 21). This finding suggests that many of these Asian students come from

those countries which were former English colonies

(Hong Kong, Singapore,

Malaysia) and that their families must be assumed to command a high degree of

resourcefulness (high occupational

status of fathers, high level of educational

attainment of mothers) precisely because they have access to English

culture.40

Table 6: Mother’s Country of Birth

|

SQ 14.2 MOTHER’S COUNTRY OF BIRTH

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Australia

|

62.9

|

69.2

|

|

Other Anglo

|

15.1

|

10.8

|

|

North Europe

|

3.8

|

3.3

|

|

South Europe

|

3.8

|

8.3

|

|

East Europe

|

2.5

|

0.8

|

|

Asia

|

11.3

|

6.7

|

|

Other

|

0.6

|

0.8

|

|

159.0

|

120.0

|

|

Table 7: Father’s Country of Birth

|

SQ 14.3 FATHER’S COUNTRY OF BIRTH

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Australia

|

57.9

|

63.3

|

|

Other Anglo

|

16.4

|

17.5

|

|

North Europe

|

3.8

|

2.5

|

|

South Europe

|

5.0

|

7.5

|

|

East Europe

|

3.1

|

1.7

|

|

Asia

|

11.9

|

6.7

|

|

Other

|

1.9

|

0.8

|

|

N

|

159.0

|

120.0

|

Table 8: Primary Language Growing Up

|

SQ 14.4 ENGLISH PRIMARY LANGUAGE GROWING UP

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

YES

|

83.0

|

90.1

|

|

NO

|

13.0

|

9.9

|

|

Arabic

|

0.6

|

0.8

|

|

Cantonese

|

8.8

|

0.8

|

|

Other Chinese

|

1.3

|

0.0

|

|

Croation

|

0.6

|

2.5

|

|

Estonian

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

French

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

German

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

Greek

|

1.3

|

2.5

|

|

Italian

|

0.6

|

0.8

|

|

Vietnamese

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

Serbian

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

N

|

159.0

|

120.0

|

FAMILY PROCESS

A survey by questionnaire, using student’s self-reports, is ill-suited to capture reliably family processes and dynamics which go back a long way in their lives. Here the interviews with the students reveal more adequately how stable and supportive family environments contribute to take children and adolescents through their comparatively long educational careers and sustain students on robust levels of self-esteem and appreciation of self-worth. Students also report here the high degree of intensive consultation and discussion with their parents at incisive stages of their life-careers, especially with the decision where to study and what to study at university :

... After talking to my parents, they just sort of said we leave it up to yourself and they sort of said you know maybe you should leave it open a little bit more, because you’re still pretty young. As it was, I was only seventeen (1 — B2).

Well, my father was a lawyer, and I have a bit of an idea what lawyers did. He didn’t really want to push me into the career, he even sort of recommended against it a couple of times when he came home after a hard day (4 — B2).

Because, when I finished my arts degree I felt law was a substantial career. Arts was interesting. I thoroughly enjoyed it but I thought, career-wise, law would be better. And I think parental desires as well played a role (26 — Bl).

Of course, there is not always agreement in family process:

The reason why I wanted to study law was because when I came into the Bachelor of Education, I was accepted into the law degree. My parents thought it was a bad career for a woman and they persuaded me to become a school teacher. They thought that would be easier for me and I was persuaded at that age to do that (28 — B1).

It is consistent with such reports

on the influence of family process on career decisions of students that law

students, especially

the younger ones, rank the importance of the information

about their studies and career which they obtain through their parents,

before

they applied for admission to a law degree, fairly high and above the

information which they obtained from career advice and

information officials. As

students grow older, this importance of parental consultation fades,

retrospectively,41 behind the relevance of information

obtained through their friends, and hew especially the friends who happen to be

lawyers themselves

(Tables 15 and 16).

Generally, it happened only rarely

that students reported spontaneously on their family relations in the context of

talking about

their educational careers but neither did they mention any

particular problems in their families in this respect. This could mean

that the

students take a favourable secure base for granted, especially since the group

with which they mix at law school is so highly homogeneous and does not

provide for many strikingly contrasting experiences. On the other hand, students

are also aware of

divisions among the student population which run exactly along

the line of parental support:

And if you have to work [in order to support yourself] then it is just tough, but I just do not know how they expect you to be able to get through the course. And graduates are more likely not going to have the support of their parents. And so there is a marked sort of division between the undergraduates who most likely are going to have the support of their home (2 — B8).

One thing I find difficult is, this being a full-time course, I think it caters very much for people who are being supported by their parents. The demographics on that are obvious. I think it is incredibly difficult to support yourself and do reasonably well (15 — B11).

There is not enough variety of people here ... And that reflects on the work that they [students at law school] do and what they expect from us and what they expect from the teachers and what they expect from the courses ... In that I mean they tend to come from a very sort of wealthy background, their parents are very well educated ... It is a very elitist selection (16 — B7).

Socialisation and Education in Secondary Schools

The Type of Secondary Schools

The lively

public debate on secondary schools in NSW highlights the importance which the

general public here attributes to formal

education. This debate draws a more or

less sharp distinction between state (public) schools and non-state schools and

attributes

the different outcomes of their selective operations to a perceived

difference in the quality of the education which the different

school types

provide. Given the ambiguous operations of education organisations as discussed

in this study, any account on what high

schools actually achieve differently

from each other must be viewed with suspicion. We can only safely assume that

any significant

difference in educational practices of the different types of

secondary schools rests solely on the (different) outcomes of different

selective admission practices. In other words, the quality of the performance of

secondary schools is the quality of the selected

student populations, or, the

more selective the admission practices of particular types of high schools are,

the easier it is for

these schools to allege superior institutional performance.

The data reported by the law students support such assumptions. When we

correlate the HSC score of law students with the type of high

school they

graduated from, we find no statistically significant relation between the

different HSC scores and any particular type

of high school. On this count,

then, no particular type of high school delivers a particular type of

“better student”

as far as admission to law school is concerned.

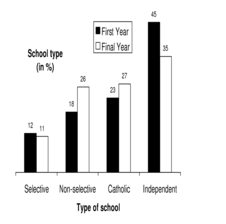

Table 9: Type of School of Graduation

|

SQ16 SCHOOL TYPE

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Selective

|

11.9

|

10.8

|

|

Non-selective

|

18.2

|

25.8

|

|

Catholic

|

22.6

|

26.7

|

|

Independent

|

45.3

|

35.0

|

|

TAFE

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

Other

|

1.3

|

2.7

|

|

N

|

159.0

|

120.0

|

In contrast, significant positive correlations are found when we relate the

type of school to the level of family resources available

in the families of law

students. Here it is evident that it is the observed strength of family

resources and family process of the

families of students who are eventually

admitted to law school which enables these families to have their children

admitted to selective

rather than to non-selective secondary schools in

disproportionately high numbers (Table 9). The selective accumulation of these

student populations, in turn, achieves the higher performance levels of

selective schools. This applies to selective schools both

in the state and in

the private sector of secondary education.42 When we

compare the different intake samples of law students, we find that in the group

of students who have been admitted in 1990

(first year law) and directly from

secondary school, the proportion of graduates from private schools, that is,

Catholic and independent

schools, is considerably higher than in the group of

students who have been admitted 1986 or earlier, and who are more varied in

their ways of finding entry to law school. Given the different composition of

our samples, these findings are partly an indication

for the tendency that, in

the light of higher competition from increasing numbers of academically highly

qualified children for the

admission to restricted courses of study like

medicine and law, there is a stronger move to selective schools generally, and

partly

that admission practices of the law school at present favour the direct

admission from high school. Students from selective schools

dominate this group

which is favoured by present admission practices. In other words, also the

admission practice of the law school

prefers, as do selective schools, what the

educational system already prefers.43 This tendency

accentuates the fairly established pattern, pointed out in the framework of our

underlying model above that the relative

small sector of selective schools

provides, relatively and in absolute numbers, more entrants to law school than

the large sector

of non-selective public schools. Stuck with greater numbers of

students with a greater variety of personal characteristics, non-selective

high

schools classify comparatively less students with academic credentials which

qualify for university studies, and they classify

even less students with

academic credentials which qualify for admission to law school.

We must

assume, then, that rather than different approaches to education, different

family styles determine the operational outcomes

of the educational practices of

selective and non-selective secondary schools respectively. These are, in turn,

reflected in their

classification schemes. Parents who are particularly

committed to the formal education of their children perceive admission to a

selective school to express such a parental commitment and they choose selective

schools for their children for this reason. This,

in effect, self-selection of

families who are committed to formal education, provides selective schools with

a highly homogeneous

population of largely motivated students while at the same

time preventing a more favourable mix of students in the non-selective

public

schools.

Also at this level, we can observe specific operations of the

structural coupling of economics and education. Parents who are committed

to

education and who are in a position to pay but have not attained high levels of

educational attainment themselves can participate,

to a degree, in the selective

operation of secondary schooling by “buying” their children a

“better education”

in selective (private) schools. Our data show

that it is predominantly families where fathers are reported to hold managerial

and

entrepreneurial occupational positions who send their children to private

(independent) schools, while students from families with

fathers who are

reported to hold upper professional or upper public service occupational

positions are less frequently reported to

have their children exclusively

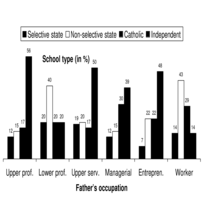

admitted to private schools (Charts 10 and 11).

Parents who are committed to

the value of formal education are also committed to the long-term goal of

university studies for their

children. Students who come from such families

internalise such expectations and are pulled along toward this goal. They find

it

hard not to accept such middle- class and upper- middle-class values towards

university studies. In contrast, students in non-selective

schools are, on the

whole, subjected to a more diffuse set of pulls. Among them, and depending on

local mixes of student populations,

the variance of local sub-cultures and the

macro-economic climate, to exit the education system altogether, to leave the

parental

home and to earn money or to set up own families must be seen as very

strong motivations which may override the value of formal education

(discussed

in section 4.4).

Chart 9: Type of School of Graduation of Student

Chart 10: Father’s Occupation by School Type (first year)

Chart 11: Father’s Occupation by School Type (final year)

When we correlate the type of high school from which law

students have graduated with the form of entry to law school, it is evident

that, while a majority of these students have come directly from Catholic and

independent private schools into the combined degree

courses (77% and 84%

respectively), greater numbers of students from non-selective schools come to

the law school via the detour

of another degree, that is, as graduate students

(61% vs. 19%).44 This observation can serve as an

indicator of the different strength of the pull of the value of formal education

as experienced

by the students in the different types of high school: it is

strongest in independent schools and weakest in non-selective schools,

with the

selective state schools and Catholic schools taking up intermediary positions.

Our data show, then, that the direct route from a selective secondary school

to law school is the best predictor for eventual admission

to law school. Not

surprisingly, the students from selective schools dominate the upper levels of

educational attainment because

their families dominate the market of favourable

family resources and family process. The pool from which law students are drawn

is formed almost exclusively here and not on any later stage in the selection

process.

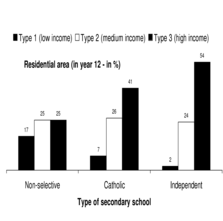

SOCIO-ECONOMIC SEGREGATION AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS

Although non-selective schools have no direct

control on the student population drawn from respective public school precincts,

also

here there is a selective effect due to the socioeconomic characteristics

of those urban areas in which high schools are situated.

The Sydney metropolitan

area, in which 78% of the law students in our sample lived when they went to

high school, is characterised

by a significant socioeconomic segregation of the

residential areas. We must assume that, in addition to the significant

prevalence

of selective schools in the educational careers of law students, also

the students who come from non-selective schools have been

selected through

schools which are predominantly situated in the more affluent residential areas

of Sydney. We can expect that this

minimises the differences between their

personal profiles and those of the students who come from selective schools.

In order to test this proposition, we grouped the residential areas of

Sydney according to a low, medium or high socio-economic

level45 and we assessed the distribution of the

reported law students’ place of residence in year 12

accordingly.46 It was found that 45% of all law

students in the sample lived in a suburb with a high socio-economic level, while

24% and 7% lived

in a suburb with medium and low socio-economic levels

respectively. The link of such a privileged living with selective high school

attendance is clearly positively related (Chart 12). The great majority of those

students who went to a selective high school lived

in a suburb with high or

medium socio-economic level in their last year at school (year 12). However,

also those students who have

come to the law school via non-selective schools

have predominantly lived in the more affluent suburbs of Sydney, even if a

substantial

number here, in contrast to students who go to selective high

schools, have lived in a suburb with a lower socio-economic level,

and probably

also went to school there. All in all, it is evident that not only selective

schools but also selective socio-economic

segregation of private living and

public schooling add to the homogeneous profile of the law student population.

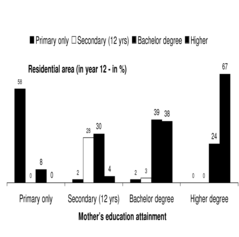

The socio-economic segregation between residential areas and their more or

less supportive infrastructure is positively related to

the level of family

resources. Surprisingly, however, the occupational status of the father appears

not to be the crucial factor

for such a link. Our data show that it is above all

the educational attainment of the mother which provides the statistically

significant

relation (Chart 13). The higher the educational attainment of the

mother the more frequently the student resided in an affluent suburb

of Sydney

while attending high school. This finding points, again, to the pivotal role of

women who do not only organise predominantly

the internal working of families

but also liaise the family system with the social environment in general and

with the resource infrastructure

and the availability of services in that

environment in particular. We, therefore, can expect a greater influence of

mothers on the

choice of living arrangements than that of fathers. In view of

such reasoned residential choices by mothers, living arrangements

must be seen

as a further measure of resource maximisation by families who are already

resourceful.

Chart 12: Type of School by Type of Residential

Area

(year 12)

The evidence for a mediating role of the family living

arrangements is further supported by the finding that also the use of the

primary

language in the family home is distributed along the lines of

socio-economic segregation of residential arrangements, with the highest

use of

English as that primary language by the families who live in the most affluent

suburbs (91%), and the lowest use by families

who live in the least affluent

suburbs (70%). However, this difference is small and statistically not

significant since the number

of law students who did not speak English as a

primary language at home is very small overall (Table 8).

SECONDARY SCHOOL CURRICULA AND THE ADMISSION TO LAW SCHOOL

Students who come to law school have studied a wide

variety of subjects at high school and there is no prerequisite requirement on

part of the law school for any particular subject (Tables 10 and 11).

However, in line with the findings above which relate to the importance of

access to dominant language and culture, we find that certain

subjects are more

intimately related to high academic achievement and so, to admission to law

school, than others. Only in this limited

sense these subjects, namely English

and Modern History appear to have a certain predictor value with regard to

eventual admission

to law school.

However, a case could be made that English

and Modern History are most clearly related to the development of social and

intellectual

competence in adolescents and young adults in Australia, because

issues dealt with by these subjects allow for a considerable degree

of cultural

communication with children and adolescents in their socialisation processes and

in the educational environment of home

and school.

Our data support such an

argument. The study of English in year 12 by students who are eventually

admitted to law school is positively47 related both to

the levels of educational attainment of their mothers and to the occupational

position of their fathers. This means,

that the higher the levels of

mothers’ educational attainment and fathers’ occupational status

are, the greater is the

frequency with which their children have studied English

in year 12. Law students who had taken English in year 12 reported only

10% and

12% of mothers with only primary school or some secondary school levels

respectively but 83% of those who had finished a

bachelor degree. Similarly, law

students who had taken English in year 12, reported 66%, 45% and 41% of the

fathers with an upper

professional, managerial or upper civil service

occupational status but only 18% with the status of a worker or similar.

Chart 13: Mother’s Educational Attainment by Type of Residential Area (in year 12)

Table 10: Year 12 Subjects

|

SQ 8.1 YEAR 12 SUBJECTS

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

Accountancy

|

0.0

|

28.6

|

|

Agriculture

|

25

|

1.7

|

|

Art

|

5.7

|

3.4

|

|

Biology

|

8.3

|

11.8

|

|

Chemistry

|

459

|

36.1

|

|

Croatian

|

0.6

|

0.8

|

|

Economics

|

40.8

|

37.0

|

|

Engineering SC

|

1.3

|

0.0

|

|

English

|

100.0

|

70.6

|

|

Estonian

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

French

|

19.7

|

74.3

|

|

General Studies

|

19.7

|

31.9

|

|

Geography

|

6.4

|

3.4

|

|

Geology

|

1.3

|

0.8

|

|

German

|

7.6

|

92

|

|

Greek Clas

|

1.3

|

0.0

|

|

Greek Mod

|

1.3

|

0.8

|

|

History Ancient

|

17.2

|

185

|

|

History Modern

|

34.4

|

31 9

|

|

Home Science

|

1.3

|

0.8

|

|

Italian

|

1.9

|

0.8

|

|

Japanese

|

2.5

|

0.0

|

|

Latin

|

17.2

|

4.2

|

|

Legal Studies

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

Maths

|

93.0

|

66.4

|

|

Music

|

5.1

|

3.4

|

|

Physics

|

35.7

|

27.7

|

|

Religious Studies

|

1.3

|

0.8

|

|

Russian

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

Science

|

10.2

|

1.7

|

|

Social Psychology

|

0.6

|

0.0

|

|

Society & Culture

|

1.3

|

0.0

|

|

Speech & Drama

|

1.3

|

0.0

|

|

Visual Arts

|

1.3

|

0.0

|

|

N

|

157.0

|

119.0

|

Table 11: Year 12 Subject — 4 Units Maths

|

SQ 8.2 4 UNIT MATHS IN HSC

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

YES

|

47.4

|

15.3

|

|

NO

|

51.3

|

56.8

|

|

N

|

156.0

|

118.0

|

As far as Modern History in year 12 is concerned, which is generally much

less popular among law students than English, Maths, Economics

or some of the

natural science options (Table 10), the proposition is only statistically sup

ported for the variable of the educational

attainment of mothers, however, here

on a high level of significance.48 While law students

who have done Modern History in year 12 only report 4% and 7% of mothers with

primary or some secondary schooling

levels, they report 34% of mothers with a

completed bachelor or similarly high university degree.49

These contrasts are less pronounced but persist in the natural

science subjects like chemistry, physics, maths or the highly specialised

subject Mathematics — 4 units. Therefore, it is important to note that the

subjects chosen for year 12 in themselves do not

“produce” more or

less social and intellectual competence in the students but allow for a

different degree of expression

of competence which the students already have.

Here the choice of English and Modern History in year 12 appear to be better

predictors

for the eventual admission to law school than maths, chemistry or

physics.

A more important role may also be played by the educational

practices in the high schools to suggest and provide preferences for particular

subjects. Our data show that there is indeed a systematic bias towards the major

subjects (English, Maths, 4 unit Maths, Physics,

Modern History) being most

consistently taken by the students from independent schools. However, this

positive link of choice of

subject to selective school is only statistically

significant for Modern History. The correlation with the subject Maths and 4

unit

Maths reaching only moderate levels of significance (p=0.0527 and

p=0.0385). This means that the choice of subjects, at best, co-varies

with the

particular practices of the high school and is not a predictor for admission to

law school by itself. These classification

practices of respective high schools

constitute the “academic credentials” of any given student, and are

the most important

factor in determining his or her entry to tertiary education,

or — as in our case — admission to a combined law degree

(Table 12).

Table 12: Entry Score

|

SQ 8.2 4 UNIT MATHS IN HSC

|

||

|

|

First Year

|

Final Year

|

|

YES

|

47.4

|

15.3

|

|

NO

|

51.3

|

56.8

|

|

N

|

159.0

|

121.0

|

THE CHOICE OF STUDYING LAW

The last years at high school set the scene for important career decisions to be made by the students. Their reports after admission to law school reflect, retrospectively, that such decisions were not reached overnight. More surprisingly, it emerges from these reports that, for most of the students, the entry to law school was not a clear-cut choice or the preferred option but the more contingent result of vexing processes of narrowing down the field of options by exclusion of other options or by sheer serendipity. Typically, students report frequently a competing preference for both law and medicine50 — once it was clear that a sufficiently high level of the HSC score was achieved. This dilemma was ultimately resolved by reference to some further circumstantial factors:

To some extent it was partial because I had done very well at school. But the idea of becoming a doctor has never really interested me ... I turn green at the sight of blood and all sort of terrible things... and I’ve been very interested in debating at school. I’ve done quite well and the law seemed to fit in very nicely with that (3 — Bl).

[Law was] the course with a high aggregate that I could get into because it was next to medicine at that time. And that’s mainly the reason because it was the thing to be ... (4 — Bl).

However, for many students the choice was even more indeterminate:

It’s just something I arrived at. I often think how glad I am now that I have got from where I am and [that] I h’ve chosen what I h’ve done. But the more I think about it it’s just really a matter of luck. There was never any time when I sort of thought “Ah! That’s what I want to do”, because I saw Dad or anything like that (4 — B2).

Two aspects of law appear to make it difficult for

high school students to arrive at the decision to study law as the preferred

choice

in a more determined manner. The first is the relative social distance

and cultural artificiality of the operation of law in the

perspective of high

school students. Students cannot ground their references to law on any of the

traditional academic subjects in

high school. While they collect references to

law in a number of different subjects, none of them covers the question what law

“is”

in its entirety. The newly introduced subject “Legal

Studies” may address some of these problems of identification but

it may

also add to the confusion of high school students, given the complexity of the

operation of legal systems.

The second is the work practice definition of

law rather than the academically (scientifically) developed definition of the

discipline.

This traditional definition of law as “what lawyers

do” may make the career choice easier but it still leaves in doubt

whether

this is what academically highly achieving students want to study at university,

especially since students are aware that

law is obviously more than what lawyers

do. Here the combined degree has greatly enhanced the attractiveness of studying

law at university

because it allows for a sharper focus on the particular

academic interests of high school students as forged in the institutional

setting of high schools while at the same time retaining the prospect of an

established vocational career.

The answers of the students to the question

why they wanted to study law appear to reflect this unique historical and

cultural feature

of law as an academic discipline when they, on the one hand,

rank interest as a reason highly and, on the other hand, rank the technicality

of having had a sufficiently high entry score almost as highly (Table

13).51 Here, the responses to the questionnaire