Legal Education Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal Education Review |

|

PACKING THEM IN THE AISLES: MAKING USE OF MOOTS AS

PART OF COURSE DELIVERY

ANDREW LYNCH *

INTRODUCTION

Post-Pearce Report,1 many Australian law schools

have moved to embrace the teaching of legal skills with an enthusiasm that few

could have foreseen prior

to 1987, or indeed, in the immediate aftermath of that

Report.2 In many instances, it has been the

fourth-wave3 law schools which have been at the

forefront of this development.4 The incorporation of

skills into the undergraduate curriculum has always been a source of great

concern and debate.5 The teaching of skills “on

the run” as it were, is often seen to necessitate a corresponding lack of

attention to the

teaching of substantive law or theoretical

perspectives6 and, as a result, true “integration

of skills development, skills theory and practice, into a holistic and effective

educative

process has proceeded slowly”.7 A

dismissive attitude to the old liberal education versus skills training debate

has been adopted by those who now argue that the

“existing challenge that

confronts legal education ... is the integration of doctrine, theory and

practice into a unified,

coherent curriculum”.8

Accepting this as the task presently facing legal educators, the underlying

purpose of this paper is to demonstrate, by reference

to an example of the use

of moots in a Constitutional Law subject, that skills exercises can be used to

good effect as part of course

delivery to all students — not just those

performing the skill at any particular time.

Usually the only audience which

mooters have, aside from the specially-constituted Bench, are those few friends

or family who come

along to lend their support. In some cases these people may

not be welcome and the moot occurs in camera, as it were. But even when

there is

an audience, there is little suggestion that they are intended to benefit in any

way by observing the moot. Their role is

normally confined to the curious one of

silent cheersquad. Certainly, the idea that those present should be able to (or

would even

be remotely interested in attempting to) follow the arguments made by

counsel seems to have been given little credence. The fact

that the spectators

are rarely, if ever, provided with any information concerning the moot problem

indicates the neglect of the benefits

of mooting to the audience.

This seems

to reflect a rather limited appreciation of mooting and its power as an

educational device. While it is widely acknowledged

that moots provide skills

training for those students involved, this paper argues that moot programs which

are run in the context

of a particular area of study may be structured so as to

enhance the acquisition of knowledge of the substantive law by both the

participants and the audience.

This idea has been tested by the author

in delivering the Constitutional Law course at the University of Western Sydney,

Macarthur9 over the last two years. The findings from

that experience support the view that a mooting program provides, not only an

educational

experience for the mooters, but also serves as a means of engaging

the interest of the spectating students in a substantive topic

by situating that

topic in a discipline specific context, and one which is very different from

lectures or tutorials.

THE COMMONLY PERCEIVED ADVANTAGES OF MOOTING

Before examining the educational possibilities that mooting presents when one

considers spectators, it is helpful to quickly revisit

the advantages of the

exercise for its active participants. It is widely acknowledged that students

gain a number of generic skills

from mooting.10 These

can be grouped under the umbrella name of “communication skills” and

include the ability to present an oral argument

(whilst being

interrupted),11 to be capable of conveying meaning

through written expression and also to work as a team with the various forms of

communication

that entails — notably negotiation and

explanation.12 Of course, the very legal nature of the

exercise ensures that mooters must be competent legal researchers and confident

in their

knowledge and use of legal language.

None of this is surprising and

all these benefits of mooting have been appreciated (at least implicitly) since

the practice of mooting

evolved at the Inns of Court several centuries

ago.13 However, in recent times, attention has been

given to the substantive content of moots and how the exercise encourages

interest in,

and retention of, that material.14 This

would seem to be the case whether the content of the moot has previously been

taught to students or is in fact being exposed

to them for the first time as

part of an exercise in problem-based learning and knowledge construction.

An

example of the former situation (which may be called “confirmatory”)

is the undergraduate tax mooting program described

by Bentley when he says:

The advantage of an integrated skills program is that the substantive and

skills components can feed off each other while achieving

their own objectives

and learning outcomes. For example, a moot topic could focus on the difference

between capital and income. Students

acquire the substantive tax knowledge

through lectures and through preparation for the moot. They acquire the mooting

skills using

the substantive subject matter. They then demonstrate the learning

outcomes for both the substantive subject matter and the mooting

component

through their performance in each element of the

moot.15

The alternative approach to setting moot

problems is to have them deal with material which is initially foreign to the

students but

which they must learn in order to complete the task successfully.

The content may be dealt with in lectures or tutorials subsequently

or it may be

covered solely through the moot. Definitely more challenging for the mooters,

the educational theory behind such an

approach is best identified as a form of

constructivism — the active attainment of knowledge through the

student’s exercise

of their own initiative and work (hence the label

“constructivist” seems appropriate). In particular, such moot

programs

are problem-based learning in its purest

form.16

The acknowledgment that mooting assists

student understanding of substantive law as well as developing a multitude of

practical skills,

may seem obvious, however, as noted above, these have been

identified as outcomes for those students actually involved — the

mooters.

This paper seeks to look at moots from the neglected angle of the spectator. In

essence it does this by asking two questions:

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW MOOTS

AT

UWS MACARTHUR — 1997

All core subjects of the Bachelor of Laws curriculum at UWS Macarthur must

feature a 25% skills component. This means that in each

of these subjects, a

quarter of the teaching time and the assessment must relate to a specified legal

skill. For example, in Introduction

to Law, students receive instruction in

legal research techniques for (on average) one hour a week and must complete a

substantial

legal research exercise known as a “pathfinder” which is

weighted at 25% of the total marks available for the subject.

The skill which is

concentrated upon in Constitutional Law is mooting which is worth 30% in total.

The slightly higher weighting

was a recognition of the very high demands which

mooting makes upon students in contrast to some other legal

skills.17 Additionally, there comes a point where

immutable delineation between substantive content and skills is both unrealistic

and negative.18 The students were marked just as much

on their understanding of the legal issues involved in answering the moot

problem as on their

advocacy and court etiquette.

In 1997 a number of changes

were made to the delivery of the subject with the aim of pacing mooting

throughout the semester19 rather than the previous

system of the moots being clumped at the end of the course where they occurred

not only in the designated

skills hour but also the two hour blocks set aside

for tutorials. Once that decision had been made, it was only logical that some

sort of relationship should be established between the lectures, tutorials and

skills sessions. As most of the skills sessions would

be given over to the

hearing of moots, it made sense for the moots to concern material already

covered in lectures and tutorials

so that there would be some definite

connection between all three arms of the course. Thus a model was adopted under

which a topic

would be lectured upon in, say, week five of semester. The

students then prepared for a tutorial on this topic in week six and, finally,

witnessed four of their classmates perform a moot concerned with this area of

the law in week seven.

There were two attractive features of this approach.

Firstly, it enabled the benefits that Bentley found in his undergraduate tax

program20 — the reinforcement of student

understanding of lectured topics through preparation for the moot, and the

assessment of students

in the professional context provided by the moot court.

This, of course, comes at the price of foregoing the benefits of asking students

to actively construct their own knowledge in addressing a moot problem dealing

with issues they are unfamiliar with, as described

above. This is the difficult

choice which faces anyone who is devising a moot program. Essentially, it is a

question answered by

the context surrounding the program. In this instance,

where the moots are but a part of a larger subject, the limitations of the

subject must also apply to the moot program. Ultimately, the factor which

determined that the Constitutional Law moots would be confirmatory,

rather than

constructivist, was the limited time available to teach the course, with the

corresponding demand which that imposes

upon students to assimilate a lot of

information quite quickly.

Secondly, looking beyond the issue of the

mooters’ learning, it presented an opportunity for what may be best

described as informed

spectating. Essentially, all this does is seek to extend

some of the benefits of mooting to the audience. Surely their understanding

of a

legal topic can be improved by watching others debate the correct application of

the law to a problem? We often request our

students to make tutorial

presentations to each other. The fact that a moot is situated in an extremely

legal environment —

unlike lectures or tutorials — should only

strengthen the learning experience for all concerned.21

To that end, over the course of semester, all students watched the moots

of their colleagues in the same skills/tutorial group.22

They were provided with the moot problem about 15-20 minutes before the

moot actually commenced and given that time to read

it.23 The moot problem was based around the topic

covered in tutorials in the preceding week and lectured upon the week prior to

that.

Any significant educational benefit to the audience is absent if the

moots are constructivist in nature. If the students have not

studied a topic in

the subject but some of their number answer a moot problem on it, the two groups

— mooters and audience

— are not operating from a remotely similar

knowledge base. In these instances, the audience is too far removed from the

issues

under discussion and will gain little from hearing a series of complex

arguments on a topic with which they are unfamiliar. It was

only by adopting a

confirmatory role for the moots that there was any possibility of them assuming

the role of a third form of delivery

of the subject matter.

DO INFORMED SPECTATORS LEARN FROM OBSERVING MOOTS?

Having described how the moot program was integrated into the Constitutional

Law course so as to assist student understanding of the

substantive content

through the participation in and watching of moots, the next question

must obviously be: did it work? There is no justification for packing the

gallery of a moot court with students

if they are not going to learn anything

but merely cause distraction and add to the anxiety of the mooters.

At the

end of the moot program in 1997, the students were surveyed and asked three

questions as well as invited to make any general

comments. The statistical

results and a representative sample of student responses help to indicate their

attitude towards the program

and explain the reasons behind the changes

implemented in 1998. Of the three questions, it is the second which is of

primary interest

to this paper (Watching other moots assisted you in

understanding the subject matter of Constitutional Law?) but the responses to

question 1 complement the earlier discussion about moots

generally.24

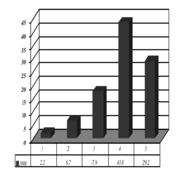

Question 1: Performing in moots in Constitutional Law was a valuable experience.

[Total Responses: 56 (1997)]

[Total Responses: 56 (1997)]

These figures are

hardly surprising given what we already know about the (normally retrospective)

fondness which students have for

mooting.25 Some of the

comments on the survey forms explain these figures and lend further support to

the numerous advantages of mooting identified

earlier:

And from a student who wanted to cover all bases:

– It allowed me to practically apply my knowledge

– It was an enjoyable challenge

– A good practical experience

– Allowed me to gain more experience in legal research.

From establishing that most students found value in their mooting experience, the next question focussed upon their role as spectators across the semester.

Question 2: Watching other moots assisted you in understanding the subject

matter of Constitutional Law.

[Total Responses: 57

(1997)]

An immediate glance at these

results indicates that they are much more evenly spread out and hence require a

more thorough analysis.

Further complexity arises because the comments which

students wrote do not bear a great relationship to the numerical ranking they

gave in response to the question. It is almost as if there are two scales in

operation. Student A may give a score of 1 but when

asked “why” may

have given a very similar response to Student B who gave a score of 3. This

works the other way also

— Student A may give a score of 5, but still

express reservations echoing the response of someone who gave a score of 3. The

3 mark is clearly the focal point and all sorts of comments — highly

critical and highly favourable congregate there. To clarify

matters, each quote

below will indicate what score the particular student gave in answer to the

question.

Firstly, it is probably best to start with the negative reactions.

In a lot of these, the students were very honest and volunteered

that the reason

the spectating was unsuccessful was due to their own lack of interest. This does

not invalidate their feedback on

this aspect of the program but is a very real

factor to be considered in evaluating the educational benefits of watching the

mooting

of others:

Responses which highlighted a more intrinsic problem with the concept of moot spectating were of the following kind:

The audience’s feeling of alienation from the moot due to

a less detailed understanding of the issues involved is something

that needs to

be solved if spectating is to be beneficial. Whilst it is obvious that students

will have a much deeper knowledge of

the topic covered in their own moot, it was

anticipated that the broad issues raised in the questions would not be beyond

the basic

understanding students should have of an area through lectures,

tutorials and their own reading. Clearly, for some students, this

was not the

case.

A number of the survey responses were critical of the way in which the

audience was provided with information regarding the moots.

As stated above, the

fact problem was distributed to non-mooting students at the conclusion of their

tutorial and about 15 minutes

prior to the hearing of the moot. As only two of

the six questions were over a page in length, it was thought that there would be

plenty of time for students to read them and have a fairly good idea of what was

to unfold in the Moot Court. It seems this was an

error of judgment:

The last comment was echoed in several responses, however, it is just not feasible in terms of administrative time and expenditure, though it would have the potential to enhance the experience for those students who chose to prepare properly. Not all the students advocated an early distribution of the moot problems, as the following response demonstrates:

However, the overall impression gained was that the

moot question should be made available much earlier and this was done in 1998.

This can only serve to maximise the potential benefits of

spectating26 for those students who wish to read it and

will make no difference for those others who do not read the question until the

hearing

of the moot itself.

The suggestion that some discussion of the

question occur prior to or after the moot was supported by several of the

responses:

These comments highlight two things: the student perception

that some guidance, additional to the mere distribution of the moot problems,

was required for the spectators, and the necessity of providing adequate

opportunity for reflection on the moot for the whole group.

Whilst timetable

constraints prevented a review of the moot immediately after the judgments were

handed down, time should have been

allocated in the tutorial in the following

week to review the moot. This realisation led to significant redesign of the

course which

is described below.

Before looking at the more positive

feedback, it should be mentioned that there was only one response which

indicated a dislike of

the spectating aspect on the ground of inappropriateness

— “private moots would have given more confidence (considering

this

is our first year of law)”. This is an issue that has to be considered and

the adoption of spectators in a first-time

moot program should be approached

with a degree of caution. In the case of this subject, almost all of its cohort

have already completed

a bail application exercise in Criminal Law (which does

occur in private) and so it was felt that as they were at least familiar

with

the moot court and its formalities they would not be as uncomfortable as

students completely fresh to public speaking of this

sort. Certainly there was

little comment or complaint from any of the mooters about the presence of the

audience. Rather it was the

spectators who tended to find reasons why they

should not be there!

Despite all of the above feedback, it is just as

apparent that some students found spectating extremely worthwhile. The

statistics

display a general balance in the responses and on the high side of

the score of 3 the favourable comments reflect the advantages

of spectating

which the course was designed to achieve:

Interestingly, the concerns examined earlier where some students felt that the moot had the potential to cause confusion due to the presentation of the law from two opposing sides, were seen by some of the higher scoring students to be a strength:

In all, the responses to this question can

be construed in a number of ways. Statistically, the percentage of students who

indicated

that watching moots assisted their understanding of Constitutional Law

in some way is encouraging — 80.7% of the responses

gave a score of 3-5 on

this question. However, one should be mindful that over 70% of those responses

are clumped at the midway point

of 3 and, as noted above, a numerical response

of 3 was not always accompanied by a positive response to the benefits of

observing

the moot.

That a proportion of the student body viewed the exercise

as without benefit is interesting — but it is hardly surprising. In

the

eyes of staff involved, it did not seem to justify the abandonment of moot

spectating in future offerings of the course —

especially in light of the

favourable reception it received with many other students. Instead it stimulated

us to adopt strategies

which would hopefully overcome some of the perceived

weaknesses in the program. The challenges for the 1998 teaching team were

twofold.

Firstly, to address the organisational gripes which students expressed

about distribution of moot information. Secondly, and far

more intimidating, to

combat student disinterest and boredom and provide encouragement for

spectators.

A CONSIDERED REVISION — 1998

The heavy emphasis on skills at UWS Macarthur can often mean that when one

attempts to revise that component of a subject the rest

of the course must

inevitably be redesigned also. This was very much the case with Constitutional

Law. The key to increasing student

interest in the moots they watched was

obviously to make them more relevant to the remainder of the course. To this end

the coverage

of a topic changed from the weekly progression of

lecture/tutorial/moot which was described above. A re-ordering occurred so that

a topic would be covered, again across the span of three weeks, but using a

lecture/moot/tutorial sequence. The placement of the

moot between the two

traditional means of delivery was designed to enable a full debriefing of the

moot problem in the subsequent

tutorial. The aim of this was twofold —

firstly, students were made aware that they would be expected to discuss the

problem

in the tutorial and would be asked about what the mooters had said in

relation to it. They were given the problem a full week in

advance of the actual

moot and told to prepare an answer to it for discussion in the tutorial, two

weeks later. Obviously, there

was now a reasonable incentive for closely

following the proceedings in the moot court. Secondly, by discussing the problem

after

the moot, staff were able to clarify particular issues that may have

become confusing in the course of the legal

submissions.27

In order to best evaluate the success

of these changes, the moot program survey was slightly expanded in order to be

more precise.

To overcome any possible confusion over the results of the

question which asked whether spectating assisted an understanding of the

subject

matter of Constitutional Law, a new question addressing just the skills aspect

of spectating was included. A question on

the tutorial debriefing of the moot

problem was also added. Before examining the responses to these, it is

worthwhile to “set

the scene” as it were by seeing how students

answered the initial question:

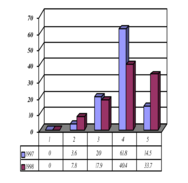

Question 1: Performing in moots in Constitutional Law was a valuable experience.

[Total Responses: 56 (1997) 89 (1998)]

The 1998 results are

not dramatically at variance with those of 1997 — there are still no

students who will rate the

value of the experience as a 1 or 2. The drop of 5

responses and the corresponding increases in 3 responses is hardly pleasing,

however.

The comments which students made do not provide any clear explanation

for this and it may well be just a consequence of the larger

student numbers.

There may also be an element of lack of novelty value — by the time

students moot in Constitutional Law at

UWS Macarthur they have already performed

in the moot court twice — a viva exam and a bail application having

already been

assessed. It will be interesting to see whether the 1998 spread of

statistics remains roughly fixed or whether it is just an anomaly

of that

particular cohort.

Do the 1998 Survey Results Provide (greater) Support for Moot Spectating?

Turning to the central issue of this paper, the teaching team were obviously very curious to see whether students reacted favourably to the spectating component of the moot program — especially in light of the changes we had made in order to improve it. There were three questions asked of students in order to determine this — the first addressing the benefits of watching others do the moot rather than following what they said:

Question 2: Watching other moots assisted you in familiarising yourself with techniques.

[Total Responses = 89]

The results for this question are hardly surprising as it was anticipated that the number of favourable responses would be high. As one student succinctly put it, “Always helpful to see how others stuff up and what they do well”. Other comments showed a more thoughtful response but really were variations on this theme:

Clearly,

there is an enormous benefit if students can learn from each other in this way.

These statistics support this but it must

be acknowledged that they are an

incidental result of this study and it was not our original intention to

demonstrate anything so

extremely obvious in the first place. Even so, it is

worth considering whether we enable our students to learn from each other enough

in the skills area. Even ignoring the possible academic benefits of following a

moot, the absorption of advocacy skills would seem

enough of a reason in its own

right for leaving the doors to the moot court open and encouraging the existence

of an audience.

A small percentage of people tended to disagree with the

proposition, seemingly for reasons of alienation from the process and a lack

of

constructive guidance:

These are fair comments but it seems

rather undesirable to give feedback to a (first time) mooting student in full

view of their peers.

It also seems a little unnecessary given the preparation

provided to students at the start of the program which should enable them

to be

pretty good judges of a mooter’s performance. Do they really need to have

it pointed out to them that John seemed poorly

prepared and could not answer

simple questions and that Sarah made irritating clicking noises with her pen?

Surely their exposure

to various videos and instruction books should enable them

to spot this behaviour as undesirable without having to publicly embarrass

the

student at such an early stage of their career. The responses of a majority of

students made it clear that they were able to

discern the good performances from

the bad through watching enough of the moots and also by identifying the

attitude of the bench.

However, giving students more detailed instruction on how

to critically peer evaluate moot performances might ensure less confusion

for

some.

Having ensured that survey respondents would not confuse the

observation of advocacy with their understanding of the academic content

of the

moot, the students were then asked the same question as their 1997

counterparts:

Question 3: Watching other moots assisted you in understanding the subject matter of Constitutional Law.

[Total Responses: 57 (1997) 89 (1998)]

[Total Responses: 57 (1997) 89 (1998)]

A number of observations may be drawn from these results. Firstly, they are

more evenly spread across the five possible responses

than those of 1997, with

over 30% of students expressing disagreement with the proposition. Not only is

this a fairly high percentage

in its own right, but it is a substantial increase

on last year’s figure of 20%. This may be explained due to the difference

between the 1997 and 1998 surveys. The suspicion that some 1997 students

answered this question thinking of the advocacy aspects

and not the subject

matter seems to have been well founded. Hence, the appearance of the new

question 2 above leads to a more accurate

portrayal of student feeling on this

question in 1998.

That said, there are still 70% of students who either agree

strongly with the proposition or are neutral about it. And so while it

must be

acknowledged that there are a greater number of negative responses, there are

also slightly more students prepared to circle

4 or 5 indicating agreement with

the proposition. The 1998 results are more polarised than those of 1997 yet

overall they do not

signify a particularly strong case for abandonment of moot

spectating in Constitutional Law — especially when they are taken

in

conjunction with the figures from question 2 which indicate that most students

benefited from exposure to the practice of mooting.

The fact that a fair

proportion also learnt something about the law as well, seems to support

continuation of this feature of the

course.

Many of the written responses

confirmed what had been said by the 1997 cohort. This was especially the case

with respect to the interest

factor of students and the difficulties in

following what was going on — for a number of reasons:

There was a slight trend amongst the 1998 students to throw blame for the failure of the spectating on to the inadequacy of the participants!

All these criticisms are valid — it is difficult to learn from any presentation if you have trouble hearing the speaker and the material is poorly presented. However, even in making this point, these respondents acknowledge that there were other mooters who were clear, well-read and illuminating speakers. Other students added praise whilst also recognising the limitations of what was being attempted:

While the statistics and written responses indicate little real difference between the views of the 1997 and 1998 cohorts about the value of spectating, the 1998 students had an altogether different course structure — namely the holding of the relevant tutorial in the week following the moot to enable discussion of the problem. They may not all have been wildly enthusiastic about the spectating, but this new aspect seemed to be more warmly received:

Question 4: The analysis of the question in tutorials in the following week was a valuable part of the moot program.

[Total responses = 89]

[Total responses = 89]

Students tended to agreed with the

proposition for fairly obvious reasons, indicating that the change in the order

of modes of delivery

was successful:

This feedback aspect of the subsequent examination of moot problems in tutorials was highlighted by a number of students. This was an agreeable outcome and one not really appreciated at the time of the course’s design. The teaching team was primarily motivated by the need to clarify the legal issues, but, of course, in doing so we necessarily gave plenty of informal feedback to the students upon their understanding of the moot topic:

However, while all of this was very positive, we had become aware of a significant flaw in the course design during semester and the students also commented on this quite heavily in completing the surveys. The teaching of a particular topic over three weeks through the various mediums of lecture, moot and, finally, tutorial was needlessly drawn out. Given that moot and tutorial were taught in a three hour block, there seemed no good reason not to have a topic covered in both those formats in the one week. So rather than having the moot on topic y and then following that immediately with a tutorial on topic x (the subject of the moot from the week before), it would have made far more sense to have had the moot on topic y occurring just before the tutorial on that same area. This would have had two results. Firstly, students would come to the moots better prepared as they had to discuss the question in the tutorial immediately after. That students tended to read up on a topic before the tutorial and not the moot was confirmed by one survey response which said, “The Follow Up tutorial is the more valuable part since by this time you have read the relevant materials”. Presumably this greater understanding of the area would improve the students’ chances of following what was going on in the moot and also their interest level. Secondly, it would make the discussion of the moot problem far easier as it would not be relying on memories of an event occurring a week earlier:

Student criticism of this aspect of the program is justified. It may now seem incredibly obvious that the moot and tutorial should have been on the same topic in the one week, but at the time that we were redesigning the course, the legacy of 1997’s week-by-week approach did not seem so undesirable. It had not been the source of negative feedback and the realisation that the other changes would not be happily accommodated by that earlier style did not come until too late. There was also a lingering fondness for development of a topic across three weeks as it was perceived that it would allow time for deep understanding to develop — but, of course, when it necessarily means there is more than one topic “on the go” at any particular time, it was in fact more likely to overwhelm students. The fact that we didn’t get it right in 1998 is unfortunate but is a natural consequence of trial and error. Certainly the reordering and availability of an examination of the question was a vast improvement on what had been done in 1997 and raised the moots from the position of an occasionally baffling postscript to an integral part of a student’s experience of a particular topic. Putting the moots before the tutorials was clearly the right approach — in future there needs to be less time between these two so as to compress the coverage of the topic to a two week span.

CONCLUSION

The introduction to this article made it clear that its purpose was really to

describe just one attempt to achieve a closer integration

between the teaching

of substantive law and skills. There are undoubtedly many other stories that

could be told. Also as certain,

is the room for continual improvement and

development. The changes that have occurred in the delivery of this one subject

at UWS

Macarthur have been fairly significant, yet it is clear that there is so

much more that can be done. In particular, stronger efforts

should be made to

ensure that theory is not lost in a sea of doctrine and skills. At present there

is a substantial portion of the

course devoted to an examination of the tenets

of Western legal theory which underpin the Westminster system of government, but

perhaps

this material could be enhanced by a greater connection to the material

covered in the moots, or at least the reflection upon them.

Overall, I would

suggest that the experience of spectating moots at UWSM has been a valuable one.

It is educationally sound and, despite

student protestations at the time and the

occasional sleeper in the audience, the survey results indicate that there are

benefits

to be gained by those students who are prepared to devote a little

preparation and energy to making the most of their spectating

role. A tighter

course structure can assist students to do this. The role of feedback can also

receive more emphasis. The potential

then exists for students to approach their

studies in Constitutional Law in a manner which prepares for, and facilitates,

learning

through a variety of contexts thus enabling a deeper understanding of

all facets of the course.

APPENDIX 1

Question 5: The Mooting Program was well organised and the instructions and expectations were made clear.

[Total Responses: 55 (1997) 89 (1998)]

[Total Responses: 55 (1997) 89 (1998)]

* Faculty of Law, University of Western Sydney,

Macarthur. The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the contributions made to

the

mooting program in Constitutional Law by Susan Fitzpatrick (the course

co-ordinator at UWS Hawkesbury), Rita Shackel and Cameron

Stewart. This article

reports on the ongoing development of the mooting program at UWS Macarthur and

builds upon a conference paper

presented by Susan Fitzpatrick and myself at

ALTA’98. Susan’s input on that paper, and thus her influence on this

one,

is acknowledged with thanks. The author alone is responsible for the

contents of this paper.

© 2000. [1999] LegEdRev 4; (1999) 10 Legal Educ Rev 83.

1 D Pearce et al, Australian Law Schools — A Discipline Assessment for the Commonwealth Tertiary Education Committee, AGPS, Canberra, 1987. I am somewhat wary about referring to the Pearce Report within the very first words of this paper as its age is starting to show. But as my reference demonstrates, its significance as a landmark remains despite the growing irrelevance of much of its content. To peruse its pages now is truly to read an historical document. The landscape of legal academia has altered dramatically since 1987. The conversion of the CAEs to universities, the survival of the law school at Macquarie and the creation of several new Faculties elsewhere (in contradiction of the Report) have combined to create a great temporal distance in the last twelve years. The most touching evidence of the Report assuming the status of archival resource is found in paragraph 16.53 with the statement that “for all law schools a minimum target staff:student ratio of 18:1 is essential” (at 641).

2 As McInnis and Marginson remind us, “the only explicit formal suggestion given by the Pearce Committee to law schools on aims and objectives was a clear message that they should ‘examine the adequacy of their attention to theoretical and critical perspectives’”. C McInnis & S Marginson, Australian Law Schools After the 1987 Pearce Report, AGPS, Canberra, 1994 at 157.

3 “Fourth wave” is a reference to the post-1987 law schools, though admittedly the terminology, which is derived from C McInnis & S Marginson, id. at 99 has the potential to create confusion. The pre-Martin Report 1964 law schools are “first wave” while those that came after are “second wave”. But as McInnis & Marginson point out, Macquarie and La Trobe are so ideologically distinct from the remainder of the second wave that they can be said to form “a distinctive third wave in legal education”. The confusion arises because it seems that the second and third waves were occurring roughly simultaneously. Curiously, McGinnis & Marginson themselves, ignore the distinction of a third wave in the presentation of tabled information at the end of their work.

4 See the review of skills development in the law schools after 1987 found at C McGinnis & S Marginson, id. at 168-170. The authors do not make any direct conclusions about their comparisons between the pre and post-Pearce law schools’ attitudes towards skills training. However, phrases such as “the new schools responded strongly to this item” (skills of oral expression and legal advocacy); “overall, the skill of drafting was integral to the new school courses”; and “all but one of the new schools responding to the survey identified subjects specifically designated to develop negotiation and interpersonal skills” indicate that the fourth wave schools were at least keeping up with their pre-1987 counterparts if not seriously surpassing them in commitment to skills teaching.

Wade acknowledges the role of new law schools in the development of the “third wave of skills” (these are waves distinct from those used to categorise the schools themselves) but places this as occurring in the 1980s. JH Wade, “Legal Skills Training: Some Thoughts on Terminology and Ongoing Challenges” (1994) 5 Legal Educ Rev 173 at 180. I would suggest that the findings of both the Pearce Committee and McInnis & Marginson, aside from the fact that the “new law schools” only started to emerge at the beginning of this decade, indicate that the increased presence of skills in law undergraduate programs has certainly occurred well into the 1990s and in a much more enthusiastic way than prior to 1987.

5 S Kift, “Lawyering Skills: Finding their Place in Legal Education” [1997] LegEdRev 2; (1997) 8 Legal Educ Rev 43 at 43-45; K Mack, “Bringing Clinical Learning into a Conventional Classroom” [1993] LegEdRev 4; (1993) 4 Legal Educ Rev 89 at 89-90; and M Le Brun & R Johnstone, The Quiet Revolution: Improving Student Learning in Law, Law Book Company, Sydney, 1994 at 169.

6 As Spiegelman says, “much of the call for reform in legal education can be seen as a conflict between theorists, who want to move toward more sophisticated abstraction, and practice-oriented teachers, who want to move toward more concrete learning”. P Spiegelman, “Integrating Doctrine, Theory and Practice in Law School Curriculum: The Logic of Jake’s Ladder in the Context of Amy’s Web” (1988) 38 J Legal Educ 243 at 245. Some key literature in this area includes W Twining, “Pericles and the Plumber” (1967) 83 LQ Rev 396; N Jackling, “Academic and Practical Legal Education: Where Next?” 4 Journal of Professional Legal Education 1; J Goldring, “Academic and Practical Legal Education: Where Next? — An Academic Lawyer’s Response to Noel Jackling” 5 Journal of Professional Legal Education 105.

7 S Kift, above n 5 at 44.

8 P Spiegelman, above n 6 at 245 where he also says, “If it were necessary to choose among teaching doctrine, teaching practice, and teaching theory, then a continuing debate might make sense”. See also K Mack, above n 5; K Mack, “Integrating Procedure, ADR and Skills: New Teaching and Learning for New Dispute Resolution Processes” [1998] LegEdRev 4; (1998) 9 Legal Educ Rev 83.

9 The same course structure was employed for the delivery of Constitutional Law at UWS Hawkesbury. Students undertaking Bachelor of Commerce/Law degrees at UWS Hawkesbury complete a number of subjects from the law program at UWS Macarthur as part of their undergraduate course, before transferring to UWSM to complete their combined law degree. Constitutional Law is one of the UWSM subjects taught by the staff at UWSH.

10 Only in very recent times has mooting been subject to serious criticism about its ability to teach useful legal skills which adequately prepare students for legal practice. This is found in A Kozinski, “In Praise of Moot Court — NOT!” (1997) 97 Colum L Rev 178. Although Kozinski is addressing the use of mooting in most American law schools, there seems no reason why his views should not extend to most moot programs in Australia. Kozinski’s article is a timely attack on our complacent assumptions that moots provide students with “real world” experience. However, the article fails to appreciate the significance of contextual variables upon skills training in the undergraduate curriculum. Speaking as one who is obliged to conduct moots with first year students, I can foresee disastrous consequences of an application of Kozinski’s school of hard knocks style of mooting in such an environment. So, whilst Kozinski has provided a fresh perspective in the sparse literature on moots, I submit that many of the suggestions he makes may only have value in moot programs at an advanced level — perhaps even beyond the undergraduate curriculum altogether and at the stage of professional training only. That said, I do not deny that most undergraduate skills training is noticeably artificial when contrasted with the reality of practice. See J Costinis, “The MacCrate Report: Of Loaves, Fishes, and the Future of American Legal Education” (1993) 43 J Legal Educ 157 at 171-5.

11 See T Gygar & A Cassimatis, Mooting Manual, Butterworths, Sydney, 1997 at 3-4; J Snape & G Watt, The Cavendish Guide to Mooting, Cavendish Publishing Limited, London, 1997 at 11-12. The latter publication tends to present the art of moot presentation as a uniquely legal skill and the authors talk of “the presence of a certain nebulousness — an indefinable quality” which enables lawyers to “explain simply and clearly what may be very complex legal material” (at 11-12). However, the view of Bentley seems preferable when he states that “the skills identified as essential to good lawyering are not exclusive to the legal profession. The skills are often defined in different terms in other disciplines, but the content is essentially similar”. D Bentley, “Mooting in an Undergraduate Tax Program” [1996] LegEdRev 4; (1996) 7(1) Legal Education Review 97 at 99.

12 T Gygar & A Cassimatis, above n 11 at 4; J Snape & G Watt, above n 11 at 12-13; A Lynch, “Why do we Moot? Exploring the Role of Mooting in Legal Education” [1996] LegEdRev 3; (1996) 7(1) Legal Education Review 67 at 86-88.

13 See generally W R Prest, The Inns of Court under Elizabeth I and the Early Stuarts 1590-1640, Longman, London, 1972; and WJV Windeyer, Lectures on Legal History, 2nd ed., Law Book Co., Sydney, 1957 at 137-139.

14 A Lynch, above n 12; D Bentley, above n 11 at 117; JT Gaubatz, “Moot Court in the Modern Law School” (1981) 21 J Legal Educ 87 at 89.

15 D Bentley, above n 11 at 104. This approach is similar to that adopted in the Constitutional Law course at UWS Macarthur which will be described in detail below, however, the focus of this paper is upon the learning experience for spectators of the moot.

16 For an overview of the educational theory relevant to moots, see A Lynch, above n 12 at 74-81. See also S Kift, above n 5 at 59-71; M Le Brun & R Johnstone, above n 5 at 71-80 for discussion of constructivism. It goes almost without saying that either kind of moot — confirmatory or constructivist — is an example of experiential learning for the mooters. See DA Kolb, Experiential Learning: Experience as The Source of Learning and Development, Prentice-Hall Inc, New Jersey, 1984. This concept is also explained in all three of the above sources.

17 In 1997 the 30% was split evenly — 15% for oral argument and 15% for written submission. In 1998 the teaching team decided it was desirable to tip the balance in favour of the oral work required of students. Hence this component was weighted at 20% and the written submission was worth 10%.

18 Above n 8.

19 All subjects at UWS Macarthur are one semester in length.

20 See quote accompanying n 15.

21 The importance of presenting knowledge in some context related to its use is discussed by JS Brown, A Collins & P Dugid, “Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning” (1989) (Jan-Feb) Educ Researcher 32.

22 Fortunately in 1997 the numbers in the groups facilitated this in almost all cases. Most groups were of 24 students each and with four students appearing weekly in one of six moots, the moot program was completed with only a few extra moots needed to accommodate extra students. In 1998 however, student numbers rose to about 32 in each skills group with the result that many more extra moots had to be held outside of contact hours. These moots had no audiences.

23 Student feedback on this aspect of the program was fairly critical and shall be examined below.

24 The third question asked of students was their views about the general organisation of the program and the results for this are contained in Appendix 1. This information is included solely to give some indication about the program which has been the source of the data analysed below.

25 See the section above titled “The Commonly Perceived Advantages of Mooting”.

26 Survey responses considered below, indicate that there may actually be some, despite the comments considered so far!

27 Obviously, this process calls for tact on the part of the tutor. In providing a legal answer, great care should be taken not to be too harsh on some of the more outlandish submissions which counsel have made.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LegEdRev/1999/4.html