Legal Education Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal Education Review |

|

TEACHING NOTE

Interdisciplinary Teaching in Law and Environmental Science:

Jurisprudence

and Environment

LEE GODDEN &PAT DALE*

I INTRODUCTION

Griffith University introduced an integrated Law and Environmental Science degree in 1992. Students who successfully complete the five-year course receive both a Bachelor of Law and a Bachelor of Science degree. The first graduates entered the work force in 1997. With burgeoning regulation of the environment these graduates will help fill a growing demand for legally qualified environmental scientists or scientifically qualified lawyers. The first years of the degrees of the course are devoted to studying the two discipline areas, with integration across disciplines wherever possible. One example is that many of the core legal subjects set an integrated law and environmental science assignment that, for instance, might include the environmental and legal aspects of toxic torts. The theoretical and philosophical frameworks of law and environmental science are integrated in the fourth year subject, Jurisprudential Theories of Law and the Environment. This subject, together with a final year integrated research project, represents a culmination of the interdisciplinary study across the two degrees. The subject is a novel one, being the first of its kind in Australia, and is the focus of this article. We outline the aims of the subject, its approach, content, teaching and assessment methods, summarise innovative student achievements, and provide illustrative feedback from students.

AIMS

The general aims of the subject are to provide an interdisciplinary framework for the study of Law and Environmental Science. The approach combines both theoretical issues and substantive Law and Science. Currently, the subject dovetails with a first semester jurisprudence subject. In the first few years of offering the general jurisprudence section was not separated from the integrated law/science component. Instead, the subject commenced with a ten week jurisprudential section and then the integrated focus continued thereafter across two semesters. Under the new structure, the first-semester subject, (and the former 10-week component) applies a theoretical and analytical perspective from a range of jurisprudential schools of thought. Ultimately, it examines how law is relevant to human experience.1 This focus is common to all integration areas, not only the Law/Environmental Science integration.2 In addition, Environmental Science students are already familiar with the basics of the philosophy of science which is taught in earlier years in the context of hypothesis testing and experimental design in various Environmental Science subjects. The second semester subject is developed and implemented by academics from each of the disciplinary integration areas. What follows is an account of the way the Law-Environmental Science integration is developed.

APPROACH TO INTEGRATION OF LAW AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE

The principal aim of this subject is to develop a conceptual framework to

assist the evolution of an integrated approach to the study

of Law and

Environmental Science. As such the approach pursues a theoretical understanding

of central issues concerning the environment

that arise in Science, in Law and

also as a result of the interaction between the two areas. On completing the

subject, students

should have an understanding of how and why the legal process

regulates, or fails to regulate, the complex interaction between human

behaviour

and the biophysical/social milieu.

Objectives of the subject are to:

(a) examine the relevance of law to human experience in the context of the “environment”;

(b) explore the extent to which theories can provide an explanatory basis for understanding issues that arise in relation to law and the environment;

(c) discuss limitations of the theories and propose alternative bases of explanation;

(d) examine the appropriateness of substantive law and legal reasoning to environmental issues; and

(e) consider whether the legal framework is sufficiently flexible to provide

just outcomes in environmental disputes.

The specific themes of the subject

were developed in association with a “core” common part of the

jurisprudence subject.

Key concepts and issues from a jurisprudential

perspective, such as rights, ethics, justice, individual and community

interests,

sanctions and punishment, and their application to environmental

issues, are covered. In addition, various approaches to interpretation

and the

construction of meaning from a disciplinary standpoint are discussed. An example

here is the section which considers the

interaction of legal and scientific

procedures and methodologies for establishing “truth”. As a further

example, the

section on “interpreting the environment” resonates

with the discussion of postmodern interpretations of legal texts

from the core

jurisprudence section but adapts these approaches to an environmental planning

context.

The subject is not designed to be a comprehensive environmental law

subject, although various aspects of environmental law, both legislation

and

case law, are highlighted. Students are encouraged throughout to “bring

across” information from subjects taught

in both degrees and to examine it

from an interdisciplinary perspective.

The content for weekly topics was

designed to illustrate various jurisprudential issues, or to provide a point of

departure to consider

vexed ethical or moral dilemmas confronting persons who

practise in the fields of law and environmental science. For example, the

content dealing with biodiversity protection illustrates issues about the

“value” that law ascribes to the natural world.

The discussion

hinges around the relationship between law and morality in terms of legal norms

prescribing how people “should”

act when confronted with rapidly

diminishing natural species. A further theme considered in relation to this

substantive content

is whether the emergence of biodiversity protection laws,

incorporating concepts such as the precautionary principle, constitutes

a form

of natural law. A discussion of natural law as a point of comparison with

positivist law, reinforces the analysis conducted

in the common jurisprudential

section, while providing a uniquely environmental “twist” to the

theme.

CONTENT

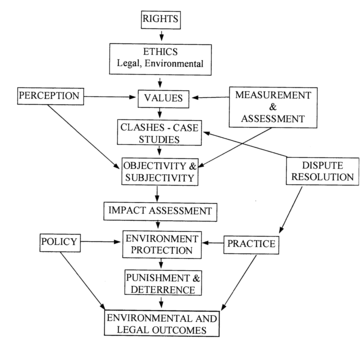

To provide a succinct summary of the content, the subject overview is shown in Figure 1 and the content is summarised in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the integration of legal “theory”3 into environmental issues such as policy development. In effect, the development of theoretical constructs about law, environmental science and their inter-action presides, and permeates the other topics and environmental issues. All of this affects the practical issues and ultimately the “grass roots” where policy decisions are put into effect and environmental and legal outcomes occur.

FIGURE 1

A qualitative model of the relationships between

subject components.

TABLE 1

Topics and Content of Jurisprudential Theories

of

Law and Environment: integration in the

second part of the subject

|

Topic

|

Content

|

|---|---|

|

Property Rights and the

Environment |

|

|

The Individual, the Community and “Environmental Rights”

|

Examines the balance between the rights of the individual, the public

interest and the needs of the environment by examining:

|

|

Environmental

Ethics/Professional Ethics |

|

|

Valuing the

Environment |

The theme of “values” discusses:

|

|

Case Studies – The Clash of

Instrumental vs Intrinsic Environmental Value |

Examines and discusses, in the context of specific examples:

|

|

Environment, Sustainability and Justice

|

Considers the problem of achieving a just balance between the often

conflicting demands of environmental conservation and development,

given the

“rights” of the interested parties. Cases studies are used to focus

discussion (eg, World Heritage issues)

|

|

Scientific Methodology for Interpreting and Assessing the Environment

|

|

|

Environmental

Perception |

Explores and examines:

|

|

Integration:

Objectivity/ Subjectivity |

How Law and Science conceive of objectivity by considering concepts such as

the reasonable person test and the scientific method.

Questions addressed

include:

|

|

Environmental Impact Assessment: Approaches and Theoretical basis

|

Focus on Government and environmental regulation.

Environmental impact statements are central to the Government’s

decision making process.

Examines the problems and limitations associated with the Environmental

Impact Statement process as an exemplar of conceptions of

“risk”,

reviewing relevant legislation.

|

|

New Approaches to Environmental Protection: From Policy to Practice

|

Examines recent Queensland policy and statutory initiatives which seek to

reform procedures, such as the Integrated Planning Act 1997

(Qld).

Critique focuses on whether the proposed reforms ensure greater

environmental protection and at the same time allow for an expedition

of

decision making processes?

Practical exercises include drafting and inputs to recent draft legislation

or policy documents as available.

|

|

Courts Versus Other Means of Dispute Resolution.

|

The growing trend is to reconcile environmental differences through

processes other than the adversarial court system. Dispute resolution

is a less

adversarial approach to environmental problems. Discussion focuses on case

studies which utilise alternatives to the courts.

|

|

Punishment and Deterrence

|

What happens to the environmental offender?

We introduce a theoretical framework for punishment, deterrence and

rehabilitation and discuss pragmatic solutions and ethics.

We refer to basic concepts of culture (values, beliefs and norms, of which

norms are the behavioural outcome).

We consider how such concepts apply to environmental offenders, and how

penalties may reflect the values held by a society and also

how these have

changed, and are changing.

|

|

Review and

Synthesis: a Conceptual Framework |

A conceptual model is developed to synthesise and analyse the theoretical

framework.

A general qualitative “model” is developed (Figure 1) to

provide an interdisciplinary framework for the study of law and

environment. The

“model” is presented as one of a possible range of conceptual

frameworks and students are encouraged

to develop their own “model”

to aid in understanding the application of jurisprudential theories to the

environment.

|

TEACHING METHODS

The subject is taught by two hours allocated to lectures and a student-lead

seminar each week. In the first two years, the student

numbers were around

8–10 but this number has increased in succeeding years to a steady state

of approximately 15–20 students.

The lecture format is informal. The

normal process is for one teacher from the two faculties involved to give an

overview “lecture”

while the other “interferes”,

stimulating discussion amongst all participants. With a small and motivated

class this

format is an effective way to achieve the subject objectives and

provides students with opportunities to develop their advocacy skills.

From the

teaching perspective we are fortunate in having two different academic

perspectives (one lecturer from Law and the other

from Environmental Science)

yet both lecturers’ first degrees were in Geography and each also has a

Bachelor of Laws. The interaction

between faculty is important in facilitating

active student involvement in the lectures and recognising the need to

communicate effectively

across disciplines.

The second hour may include

further informal lecturing or a guest lecture, but commonly uses more innovative

and entertaining methods

to convey understanding. Typically students are given a

scenario and asked to develop a case from various perspectives, using both

legal

and environmental arguments. In other instances they are asked to critically

examine environmental policy, draft legislation

to give effect to policy, or

comment on draft legislation culminating in providing a written response to the

relevant government

department. As well, practical “experiments” are

conducted to investigate the group attitude to issues such as punishment

or

perception of environment. These are then compared in class to the results of

published research on the same issues and discussed

in the light of current

theory.4

The seminar is student driven. At the start

of semester a list of seminar topics is distributed. Each week’s topic

relates to

the lecture theme for the week and is organised by students. Each

student selects topics from a designated list and a small number

of students

present their work each week. How the students organise the topic for a

particular seminar is for them to choose. Some

split the topic, others may focus

on contrasting examples. Occasionally innovative activities such as role-plays

are arranged by

the students involving the whole class, including the

lecturers.

ASSESSMENT

The Law/Environmental Science integration part of the subject has three

assessment items. These are based on class participation,

seminar presentations,

and a major assignment. The items test a range of skills and are designed to

enhance the students’ ability

to analyse and present material in an

interdisciplinary manner.

The seminar presentations are initially given on

the basis of pre-set topics related to the lecture component each week and which

covers both law and environment. The major assignment may be based on a seminar

topic or students may select a topic, subject to

it being approved by one of the

lecturers. One criterion for approval is that the topic involves both legal and

environmental issues.

It may, for example, focus on an area of law and discuss

environmental implications or it may take an environmental issue and discuss

the

relevance of law and legal process to its resolution.

INNOVATIVE STUDENT ACHIEVEMENTS

Students surprise us with the degree of insight they show on difficult

theoretical issues, both from the legal and environmental perspective.

Topics

covered in the major assignment have included: comparing indigenous peoples

rights with respect to environmental management

in Australia and overseas, a

detailed examination of evidentiary processes in environmental disputes, a

feminist critique of pollution

legislation, an examination of changing attitudes

to rural land use practices, and an examination of social contract theory and

environmental

justice. Some of the work is of publishable quality. Importantly,

the assignments provide an introduction to independent research

for the students

who all have to conduct a major interdisciplinary research project in their

final year of study.

In seminars, the work has ranged from an intensive

analysis of case law on the application of the precautionary principle in

environmental

disputes as an example of the permeation of “risk”

concepts in modern society, video presentations of world heritage

management

issues on the Barrier Reef, to a role play on negotiation for a toxic waste

dump, to a philosophical discussion between

two “trees” providing an

analysis of Stone’s classic argument – Should Trees Have

Standing?

STUDENT FEEDBACK

It is essential to have student feedback to guide the future development of the subject, given its innovative concept, the breadth of topics covered and the interdisciplinary context. The subject is evaluated each time it is completed. Overall there has been a positive response to the subject and generally student evaluations indicate that students perceive that the subject achieves most of its stated aims. Evaluations reveal that the most positive aspects of the subject are in making theory less intimidating and more interesting. A small selection of student comments follows:

I have always baulked at the theoretical content of the course since first year – due to my own mental block! I found jurisprudence finally gave me the confidence to feel I was capable of forming my own ideas and reflecting on others. I think that this was mainly due to the use of examples and relating jurisprudence to substantive issues.

Materials and subject were interesting and well structured.

In particular

students found the student seminars useful, commenting that they are:

A good way to look at issues in depth and see new ideas – of other

students.

There have been no serious negative criticisms although one comment

suggests possible improvement:

I’d make it more relevant to practical issues – probably more

theory but relate it back to stuff we’ve done in Law/

ENS(Environmental

Science).

Making sure the examples are relevant to the “real

world” issues which students will face when they graduate can accommodate

this objective. But perhaps the most rewarding aspect is the ad hoc

comments that arise in class discussion which reveal that students have been

able to draw together the sometimes disparate strands

to offer a new insight

based upon their “environmental grounding” in two disciplines.

CRITICAL EVALUATION AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

Given the positive response from students and the generally high standard of

the students’ assigned work there is no apparent

need for major changes.

However there is still some fine-tuning which is driven by experiences in the

subject itself.

For instance, we propose to augment the essay with a

document showing the “chain of research” pursued in developing one

of the seminars (eg literature search, use of legal digests, Case Annotator,

on-line data bases etc).5 This would show the process

by which information was sought – a factor of extreme importance when

undertaking interdisciplinary

study where there is a need to be very wide

ranging in obtaining information from diverse sources beyond the standard

case and statute

laws. Moreover, the “chain of research” illustrates

a student’s ability to effectively find research information

and assists

in preparing for a major interdisciplinary research project that is undertaken

in the fifth year of the degree. It also

gives recognition to the work that goes

into researching for the essay and would help avoid the temptation for students

to include

what is not particularly relevant just to demonstrate that they have

been diligent in their studies. In some complex areas competent

research may

yield a lot of material (much of which is not very relevant) or a very little.

Indeed the impetus for this development

was from one of the students who

attached such a “chain” to her seminar report, mainly because she

wished to show the

paucity of material available on her subject, despite having

carried out an extensive and “appropriate” search.

Further, as

changes occur in current issues it will be necessary to modify the content to

ensure that it remains relevant and incorporates

topical issues. One such issue

is the relationship between the rights of indigenous people and policies for

environmental protection.

Timeliness is particularly important when students

make submissions on draft policy documents or evaluate environmental policies

in

areas of current concern such as coastal management.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, in considering the subject as a whole, there is perhaps a need

for more collaborative work between the teachers in the

subject to increase the

consistency of emphasis between the core jurisprudence section and the later

integrated section. It remains

challenging to bring together the very complex

and fundamental questions about how law operates in society, and how it can be

made

meaningful to human experience in the late twentieth century using an

interdisciplinary perspective. It is a perspective that considers

law in the

light of particular experiences – the interaction of humans and the

environment and, moreover of law as itself part

of that environment.

It is

acknowledged that tensions exist between examining issues from a predominantly

jurisprudential or law perspective when some

critical environmental science

issues have no direct equivalent expression in jurisprudential traditions.

Further, and perhaps surprisingly,

any difficulties in providing a holistic

integrated framework for understanding arise not so much from a substantive

content basis

but from the need to coalesce the two very different

methodological approaches from the disciplines of law and science. To the extent

that disciplinary methodology imposes a way of ordering knowledge and

“seeing” the world, then it has been very instructive

to have to

work together to accommodate these approaches in a single subject. The

“accommodation” of the two disciplinary

bases more often than not

comes from the students themselves, who having been trained in both disciplines

are able to make the necessary

links.

By its very nature, any consideration

of the environment ranges over a diversity of issues, interests and concerns. It

would seem

then, that this requires a broad understanding as a prerequisite to

working as a professional in this field. Further, it is often

noted that the

resolution of environmental problems needs to be approached from various

standpoints, not least, the disciplines of

law and science. Such issues need not

just an understanding of relevant substantive content but an appreciation of the

values, ethics

and methodologies that can be brought to bear upon such

problems.6 While many forms of “modern”

knowledge tend toward specialisation, the scope of the environment seems to

compel an interdisciplinary,

comprehensive focus.7 The

subject, Jurisprudential Theories of Law and the Environment, in its aims,

content and teaching methods represents a still formative

attempt to equip

students with this interdisciplinary and broad approach to environmental

questions.

* Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Griffith

University; Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Griffith

University, respectively.

©2001. (2000) 11 Legal Educ Rev

239.

1 The authors acknowledge the substantial work that was undertaken by Shaun McVeigh in developing the core jurisprudence element that comprises an introductory jurisprudential section prior to the students undertaking the specific interdisciplinary section.

2 Other disciplines involved in the integrated degree courses include: Public Policy, International Business, Media, Accountancy, and Modern Asian Languages.

3 We prefer to use the term “theory” rather than jurisprudence as many matters discussed in an interdisciplinary subject of this type range more broadly than traditional jurisprudential topics. It is acknowledged that “theory” also is open to a wide range of interpretations.

4 For example, students are asked to “map” their perception of the campus. These “cognitive” maps are compared with research on the cognition of space and its incorporation in environmental planning concepts.

5 Since writing the first draft of this paper the “chain of research” has been included in the assessment, with great success.

6 G Morgan, The Dominion of Nature: Can Law Embody a New Attitude? (1993) 18 Bulletin of the Australian Society of Legal Philosophy 60.

7 For a discussion of the need for a broad approach to environmental problems see S Molesworth, The Integration of Environmental Imperatives into Decision Making, paper delivered at Courting the Environment: National Environmental Law Association Conference, Coolum Qld, 1996, Collected papers, 1.1 at 1.1.2.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LegEdRev/2000/9.html