Legal Education Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal Education Review |

|

Lawyers’ Perceptions of Their Values: An

Empirical Assessment of Monash University Graduates in Law, 1980–1998

ADRIAN EVANS*

INTRODUCTION

Public and professional discussion about the behaviour of lawyers is

perennial to the point of cliché. Commentary about perceived

inadequacies

is also commonplace, but it is ordinarily based on anecdotal, though powerful,

“war” stories. It seems,

however, that legal educators and

regulators must tackle the “ethics issue” with renewed vigour if

legal institutions

are to retain moral, and perhaps even spiritual,

relevance.1 Ethics awareness projects are, of course,

under way in many places (for example, the American Bar Association’s

“Ethics

2000” programme2); however, often

they proceed with little direct information from the mass of legal practitioners

as to their own perceived standards

of conduct. As legal educators we can only

design and teach ethics courses and help the legal profession describe the

desirable attributes

of the future lawyer using indirect information as to what

is needed. My concern here is that legal ethics programmes, both in and

after

law school, may be proceeding on a comfortable, but possibly unfounded,

assumption – that as legal educators or regulators

we can simply appeal to

the supposed better nature of our students and members in order to improve

attitudes3 and, hence, behaviour. While, in my opinion,

there is a link between lawyers’ attitudes/values and their behaviour, we

first

need to know about these attitudes and values.

The context for this

discussion – an urgent one – is the acknowledgment that justice and

human rights are under challenge

in many parts of the world. Those who stand up

for justice often need and receive advice and representation from courageous

lawyers.

Yet we do not know if courage or resilience or a willingness to take

unpopular decisions in defence of these causes is the norm or

is exceptional. We

may suspect that it is exceptional, but we do not know. The direct relationship

between the quality of justice

and the values/behaviour of legal practitioners

is, accordingly, of direct importance to the international concern for human

rights

and fair systems of justice.

In this paper I will discuss a survey of

graduates in law from Monash University4 and comment on

the implications of the results for Australian legal education. The aim of the

survey was to establish what values

are important to lawyers in their

professional lives. I did not on this occasion attempt to look at actual

behaviour because it was

too large an undertaking for the time and funds

available. This project is, nevertheless, important because it attempts to deal

with

what I consider to be implicit assumptions by legal educators that the

values of their students are sufficiently uniform and “good”

(enough) to enter professional practice. The understandable5

comfort of legal educators with the “values status quo” is

now, I think, a risky educational strategy. The results of

the survey that I

conducted suggest that there is a convincing case for introducing and

integrating a values awareness process6 within legal

education.

An initial task in this investigation is to establish whether

there is an empirical basis for the assumption that an appeal to lawyers’

aspirations is based on shared personal and professional values.

Tremblay’s reflection on the American Association of Law Schools

Clinical

Section Conference on values formation, held in Portland, Oregon in 1998,

suggests a commonality of values. He seems to

assume that lawyers have “in

place” their own sense of “moral judgment and responsibility,”

thus implying

that this is a shared sensitivity.7

Tremblay further suggests that the majority of lawyers share common values and

that the problems in professional behaviour stem from

differing views as to what

the facts of any ethical situation may be. In other words, the

circumstances of a matter can be variously interpreted, and this variety

produces

different decisions. Thus, we would agree, presumably, that human life

is sacred, as a value; however, we may argue for capital punishment,

depending

upon the circumstances of a particular offence. The difficulty here –

apart from the inevitable blurring between

“fact” and

“value” – is that there is a considerable assumption

underlying that logic. We do not really

have much rigorous

information8 to suggest that particular values –

however defined – are in fact shared by the mass of lawyers.

“Values”

are here intended to denote the beliefs that (it is hoped)

actually underlie and determine professional choices and not just those

which

are articulated.

In particular, we legal educators have no empirical basis on

which to conclude that clinical methodologies, which are internationally

growing

in acceptance within law school curricula, are effective in raising the

“moral tone” of the efforts that law

schools make to increase

student awareness of any justice imperative. I have a sense that law schools are

also slowly regaining (or,

for some, just establishing) the idea that their

primary mission is to inculcate in their students a desire to do justice, as

the goal of legal practice. If this is true, then the “moral

shape” of students – that is, the presence or absence

of moral

health in each individual – becomes a crucial concern in that mission.

Until now, only anecdotal evidence suggests

that law school graduates with

certain types of clinical experience – that is, those who have had

personal involvement with

indigent clients who have compelling legal

problems9 – enter legal practice with attitudes

that are different from those who do not choose to study this option within

their law

course.

A SURVEY OF MONASH UNIVERSITY LAW GRADUATES

A survey10 of a sub-population of Australian lawyers

to discover what values play a role in their professional decisions now provides

some information.

This article reviews the issues raised in this survey and

describes the survey process and the results obtained from a questionnaire

answered by 700 respondents, all former students of the Faculty of Law at Monash

University in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Questions

designed to place the

respondent in a personally challenging situation were composed around scenarios

of local socio-legal significance

and factual ambiguity. Respondents had to opt

for a “yes/no” response to a request for a specific action on their

part

and were then asked to rate the significance of various specific motivating

values to their choice. The questions were dispersed

purposefully in the

questionnaire to expose any inconsistencies in their responses. Demographic data

and a comparative standard personal

values survey (Rokeach) were also completed

by the respondents so that correlations could emerge and contradictions could be

highlighted.

The Rokeach instrument – a series of questions designed to

bring out respondents’ personal values – is a standard

statistical

device developed by Milton Rokeach.11 One of its

applications is to gauge, by comparison with the answers to the questions

concerning so-called “personal”

values, the accuracy of answers to

other occupationally specific questions asked of the same set of

respondents.

As discussed in detail below, this analysis strongly suggests

that there are considerable differences in the value-base – ie

the set of

values actually held by an individual – of this sub-population. Thus, for

example, in a question designed to require

a choice by an employee solicitor

between pro bono work and extra hours “in the firm” that were

demanded by a partner with influence in the firm but not necessarily the

immediate superior of the employee, a small majority (357) of those surveyed

preferred their firm’s interests, citing a mixture

of “employer

loyalty” and “employment security” as their motivating values.

This apparent lack of commitment

to the public interest might be justifiable in

a workforce that is known to be as difficult to enter as law is in Australia.

Even

though one’s first concern may well be to remain employed because of

job insecurity, this value does not necessarily exclude

other

“higher” values when employment is secure. However, nearly half

(324) of this large sample were just as comfortable

to choose the pro

bono priority, requiring a negative response to their employer and citing

“access to justice” as their motivator.

Other questions also

brought divergent answers. Taken as a whole, this study suggests, but does not

confirm, that clinical experiences

may make some difference to the attitudes

that lawyers hold. It is probable that a comprehensive longitudinal study of

lawyers’

values and correlating behaviour across many different

jurisdictions will expose compelling associations between values that lawyers

hold and their behaviour. Efforts to address the justice priority in legal

education and in the practice of law could then proceed

on a firmer foundation

– one that is based on actual knowledge of the values that underlie

notions of legal ethics.

VALUES BEFORE ETHICS?

In order to place this research in its international context, I refer to some

of the debate about legal ethics.12 The debate is not

confined to issues of interpretation surrounding, for example, conflicts of

interest or duties to the courts, though

these and many others are of central

importance. Increasingly, the accumulation of issues surrounding legal ethics is

producing a

systemic agenda. Commentators regularly decry the apparent general

lack of ethical practice in lawyers today.13 The

repetition of the assertion is likely to be demoralising and irritating to those

many lawyers who, credibly, see themselves as

ethical practitioners.

Nevertheless, these lawyers will likely acknowledge that the problem is now

chronic. One view is that a distinctive

and regressive “lawyer

personality” has emerged which is responsible for much of the

disquiet,14 though it seems pertinent to focus equally

on the causes of the lawyer “personality,” if it can be determined.

A recent issue of the International Journal of the Legal Profession

entitled “Lawyering for a Fragmented

World”15 brackets the discussion of causes

succinctly. In that issue, Pue asserts that nothing less than the “death

of God”16 and the consequential weakening of

“lesser gods” – rationality, the rule of law, and cultural

identity –

have taken away from many Westerners the basis for any value

choices. Reciting Margaret Thatcher’s comment that “there’s

no

such thing as society,”17 Pue suggests that there

are no longer any agreed scripts upon which a single values base can proceed for

any sector of a “post-Society

society.”18

Indeed, so many variables affect value choice that the very notion that we share

the same values seems offensively patronising. This

is a bleak present with a

potentially bleak future.

How are lawyers to proceed? If this question

suggests a refusal to sink in social and spiritual quicksand, then there is

hope. Hope,

however, is quite difficult when we are faced with the

inconsistencies in our justice system, as they are reported almost daily on

each

page of the newspapers and case reports. To take a compelling example,

McGillivray19 illustrates the “horror” of

valueless existence with her acute retelling of the Bernado/Homolka murderers in

Ontario.

In this case, one of the world’s most advanced justice systems

was relatively content to see a husband and wife, mutually responsible

for

ghastly serial rapes and killings, receive very different sentences. The case

demonstrated how fraying threads of law, gender,

and psychiatry were badly

entangled. Each murderer was as culpable as the other. The male is never to be

released; the female –

Karla Homolka – received just 14 years

imprisonment. There was no adequate reason to discriminate between the two in

the expiation

of an identical guilt. Referring to the values conflicts behind

this depressing result, McGillivray asks, “What is guilt when

discourses

collide?”20 In all, the law and its lawyers were

central players.

If there is definition to the issue of guilt – and,

hence, responsibility – within law, it must be in the discourse, whether

colliding or not. Continuing the discourse on values is at the centre of this

struggle. But is this suggestion too glib? As Pue reminds

us,

[l]awyers, unfortunately, are daily called upon to “judge,” to

decide for others, and to decide for themselves how they

will empower or

frustrate others. Aware, perhaps . . . that the core of our

professionalism rests on “just another” contested

“set of

narratives,” that our history provides no definitive answers for our

present, we can take no joy in the “laid

back pluralism” literary

scholars detect in life after God.21

If, however, we regard our dilemma as

involving a journey rather than a destination, this melancholy can be

challenged, not with a

solution but with a process. This would not be a

new road, merely one less known. It would also be one of the oldest. As Solomon

states,

Part of the problem is the way we tend to separate – or pretend to

separate – our business from our personal lives, as

if these were

unrelated and independent, as if one “left one’s values at the

office door.” But of course, not only

do we spend an enormous amount of

our waking lives “in the office;” our values are not divided up into

two (or more)

categories. . . . The point is to view one’s life

as a whole and not separate the personal and the public or professional,

or duty

and pleasure.22

A focus on the ideal lawyer as one who integrates her or his

professional and personal lives could begin with lawyers’ individual

initiatives. Some consciously attempt this now. They seem likely, however, to

remain in the minority in the face of a jurisprudence

and a system of legal

education that remains reluctant to weigh up the impact of its players and their

competing values as formal

contributors to a distinctly impersonal concept, that

of the Rule of Law.

A CRUCIAL OBJECTIVE – IDENTIFYING VALUES

A central foundation of lawyers’ ethics (related no doubt to the

derivation of the word “ethos” from the notion

of

custom23) is this basic creed of the Rule of Law

– that is, the notion that fairness to all people can only be guaranteed

by “the

law” (and not by individuals,24 in

the strict sense). Although battered by the modern crisis of

meaning,25 this creed, nevertheless, remains essential

for our social well-being. Social progress and good lawyering are indispensable

to each

other. Under attack from social apathy and community distrust, the Rule

of Law is in fact acutely dependent upon lawyers who personally

value justice

before income. In my view, the Rule of Law will only be upheld by individual,

honourable practitioners.

The obvious fact that society needs credible and

honest lawyers – and that they are perceived to be in short

supply26 – makes it more important to be precise

about the values base that underlies their actions. It is not enough to dismiss

the

need for investigation27 and impatiently state that

there is an urgent need to get on with the task of redefining the model lawyer,

post haste. It will be

difficult to position remedial education or values

awareness programmes in the profession and in our law schools unless we have

real

information about values diversity.

Thus, an essential preliminary task

in many jurisdictions is to identify exactly what values govern the mass of

Western lawyers’

behaviour. While as yet there is only limited and

indirect28 empirical research material available to

provide an answer, a workable hypothesis is that “values” ought to

be the focus

here rather than “ethics” as such. The latter it would

appear, in my experience, are now confused in the minds of many

Western lawyers

with proscriptive rules of conduct, and this regrettable association tends to

kill off the most active exploration

of the rich and diverse roots of

ethics.29

It is also possible, as Simon suggests,

that the study of formal codes of ethics undermines “complex, creative

judgment and

. . . subverts the vital aspirations of

professionalism.”30 Hutchinson is quite definite

when he states that

[r]eliance on codes atrophies the moral intelligence and leaves

lawyers’ adrift without a moral compass when the professional

rules run

out or give conflicting advice.31

Although a code can tend to promote purely

instrumental actions, there remain many situations where lawyers can, in fact,

decide with

some freedom how they will behave. It is possible, therefore, that

values affect practitioner motivations and, hence, their behaviour

just as

keenly as, for example, the fear of sanction (or the faint promise of praise)

under a law society code.

A BUSINESS OR A PROFESSION?

A popular hypothesis32 is that the

“conversion” of many legal practices from a professional to a

business orientation for economic reasons has

cut across attempts by governments

(and, ironically, the organised profession) to improve practitioner behaviour

– and with

it access to justice. I suggest that this situation will not

change appreciably unless and until there is a reawakening of the discourse

about personal and so-called “professional” values among

lawyers.

There is, of course, a great deal of scholarship, principally in the

United States, concerning the perceived lack of values of practising

lawyers. In

particular, in his bleak but influential book The Lost

Lawyer,33 Kronman describes his understanding of

the legal malaise for an audience beyond lawyers. Kirby and Dawson, judges of

the High Court

of Australia, have weighed in with their views; they essentially

agree with Kronman that the influence of business has undermined

the ethical

practice of law.34

Journal articles since the

publication of Kronman’s book in 1993 have discussed various dimensions of

the problem: for example,

they have considered the effect of modern legal

practice on lawyers’ ethics and35 the importance

of “nourishing” the profession;36 some have

attempted to rebut Kronman’s thesis.37 A recent

article by Robert MacCrate, former American Bar Association (“ABA”)

President and highly influential authority

on American legal education, does not

dispel concern. MacCrate, who is clearly proud of the profession’s

achievements, suggests

that the problems with ethical conduct in

the American legal profession that are identified by Kronman are restricted

to the impact

of the culture of “elite law schools and . . .

large law firms over the last 25 years.”38 While

MacCrate argues that Kronman does not make the same specific criticism of the

mass of the 800,000 American lawyers and draws

some comfort from this

distinction, he is not sanguine about the situation. It is significant that in

his 1992 report to the ABA

on the relationship between legal education and

professional development39 he did, pointedly, identify

a number of skills and, significantly, four “professional

values”40 (as opposed to personal values) that

should be taught in law schools.

While MacCrate considers that the amount of

professional and academic debate since the release of his

report41 suggests that things are

improving,42 it is clear that there is as yet no

large-scale empirical evidence for this confidence. The US profession, for one,

is not sanguine

about the situation. In 1996 the ABA weighed in again with

another report recommending extensive strategies for teaching professionalism

in

law schools and in a post-admission context; however, it would not (and, in my

opinion, probably could not) mandate any of

them.43

There are signs that lawyers’

intentions to practice law honourably cannot be assumed any longer. In January

1999 the Conference

of United States Chief Justices adopted “A National

Lawyer Plan on Lawyer Conduct and

Professionalism”44 which brought together many

credible initiatives to improve the court-based supervision of American lawyers.

While the language of

this report remains firmly in the land of aspiration and

prescription rather than in the examination of causative issues, the plan

called

for the provision of

accurate information [to the Court] about the character and fitness of

law students who apply for bar admission.45 (emphasis added)

One might wonder

how can this be done with confidence by law schools without an in-depth

investigation that identifies students’

values. Even if commitment to this

sort of investigation existed, there is, I believe, the risk that the

investigation would result

only in a great deal of academic, judicial, and

professional discussion. This debate could, of course, be a good thing; it could

in some diffuse way indicate that improvement is occurring in practising

lawyers’ values – and demonstrate that their

behaviour is improving.

Alternatively, the debate may only be evidence of the thought processes of those

of us discussing the issues,

as I suspect it is.

American concern with the

professional values of lawyers is shared in the United Kingdom, where the

emphasis is upon the role of law

schools. Economides directly raises the values

issue in his introduction to a collection of essays on the ethics challenge for

law

schools.46 After acknowledging that a

“gap” exists in law school curricula in the United Kingdom, he

asserts that there “is

no consensus as to what should fill this moral

vacuum . . . .”47 In my opinion,

the vacuum is not just an irritation to practitioners but a positive

disadvantage to their craft: it is patent that

so much of modern professional

life – in and beyond the law – positively requires the ability to

reason ethically and

to make ethical judgments.48 And

this goes well beyond an automatic reliance upon the methodology of technical

dissection that pervades law school teaching. Traditional

casebook methods on

their own, while crucial for discerning substantive rules of law, can engender a

delusional confidence among

students that this (exciting) process of

legal delineation also represents the peak of professional aspiration. It is no

longer enough to argue that this necessary “forensic”

ability is

dispassionate (requiring no moral position) in either an adversarial or

non-adversarial setting.

Eschete, in particular, makes clear that in a

social, cultural, and professional sense, the very qualities of successful

adversarial

lawyering gradually produce “undesirable features

. . . [of the lawyer’s]

character.”49 Hutchinson describes it thus:

[O]n the basis that lawyers tend to identify more than most with their jobs,

the amorality of their professional role will begin to

infect their personal

lives – the amorality will become its own impoverished morality by

default.50

If this is true, it is not useful to argue that typical

adversarial lawyers can separate their personal and professional lives

indefinitely.

Eschete maintains that the justification of adversarial positions

– the resolution of individual conflict without violence

– does not

insulate lawyers from its moral consequences:

[T]he law is not, like a sport or . . . [philosopher’s]

. . . skirmish, sealed off from moral life. Accordingly, lawyers

cannot

use the permissible skills of their trade with ruthless efficiency for

the sake of the client’s triumph without working wrong.51

I would

assert that the lawyer knows, even if the client does not, that bigger issues

and principles are at stake in every small contest

and that even those

practitioners who profess to see no ethical issue in certain behaviour have

simply chosen not to look.

The combative, adversarial practitioner –

the archetype most commonly promoted by law school curricula – will

obviously

remain with us. However, I ask whether this breed of “character

impoverished” lawyer is too ill-suited to do anything

less than fight

– unless an awareness of values diversity is acquired early in law school

and nurtured throughout the lawyer’s

professional

life.52

In my observation of former clinical

students at Monash University, lawyers’ personal satisfaction with their

working lives

is already adversely affected by the conflict between law as a

business and law as a profession. I see apathy towards, or dislike

of,

commercial legal practice among lawyers with about three to five years

experience. This dissatisfaction is echoed by senior jurists

and

others.53 Professional commitment is put at real risk

when, in addition, the moral “abyss” is made public by the

circumstances

of malpractice.54 If this gap is to be

filled and legal professionalism protected, lawyers must come to grips with what

lies at the bottom of their

personal, moral crevasse: with their values –

good and bad.

DEFINING VALUES

There is considerable, though incomplete, discussion in the literature about

values and ethics. I will make an effort to tease out

these terms as I see them

before I discuss the survey so that the purposes of the latter are clear. Much

of the literature discussion

involves overlapping definitions that are sometimes

difficult to distinguish. Thus, the United Kingdom Lord Chancellor’s

“Advisory

Committee on Legal Education and Conduct”

(“ACLEC”) 1996 report calls explicitly for renewed emphasis in law

schools

on legal values and contextual knowledge.55

These are described generally by Halpin and Palmer56 as

addressing the “deeper significance that the discipline of law is regarded

as having for society.”57

There also is, of

course, no consistency in the use of the terms “values” and

“ethics.” Halpin and Palmer

for example, speak of

[l]egal [v]alues [conveying] two separate categories. One covers values that

are identified with the law – a commitment to the

rule of law, to justice,

and fairness. . . . The other covers lawyers’

professional ethics in the wide sense – encompassing high

ethical standards, professional skills, responsibility to the client,

equality of opportunity, and access to justice.58 (emphasis added)

This

passage describes “values” only in terms of professional life and

activity – as if there is some separation

between professional and

personal values. It is echoed strongly by MacCrate in his description of four

“professional values”59 which he links to

certain defined responsibilities: they, in turn, bear a close resemblance to

Halpin and Palmer’s second category

of “legal

values.”60 Nor are these hazy intersections

assisted much by those who look more closely at the “values” issues.

In regard to the ACLEC’s “First

Report,”61 Sheinman notes that

[w]hen it talks about ethics and values . . . [it] fails to

distinguish between the morality underlying particular laws, the morality

of

citizens, and the morality of lawyers . . . 62

His point, however,

does not take us very far because he is disinclined to explore these

distinctions insofar as they may be useful

in improving lawyers’

behaviour. Sheinman appears, however, to agree with the MacCrate emphasis upon

the “professional”

in ethics. Using the term “ethics”

rather than “values,” Sheinman takes a very different stance to

Eschete.

He cites, by way of comparison with Eschete, various scenarios where

lawyers could morally choose to behave differently in their

personal lives from

their professional lives. Leaving to one side the psychological and emotional

complications for the lawyer engaging

in this dual life, Sheinman recognises

that there is a debate about the morality of this

approach,63 but he holds to his view that

if we are to produce lawyers with robust ethical standards, then it is not

personal ethics, but professional ethics [that] we ought

to be teaching

them.64

It is not clear to me why he makes this

choice, but Sheinman does not appear to see any crucial behavioural link between

the “personal”

and the “professional.” He does briefly

suggest that a “survey” would be useful (except for the fact that

experience tells us that lawyers attitudes are

variable)65 and moves on to call for more discourse and

a “set of fully articulated underlying

principles.”66 While Sheinman’s important

purpose is to call for a profound reinvestigation of the basis of legal

ethics,67 his analysis does, I believe, suffer from a

reluctance to recognise the professional/personal interaction.

It is difficult to separate legal values and professional values from

many definitions of professional ethics or legal ethics. As

a result, for the

purposes of this article I will define the latter two terms in the common

proscriptive manner as the

rules which govern lawyers’ behaviour by virtue of the fact that

they are lawyers.68 (emphasis in the

original)

It is somewhat disappointing (some would also say premature) to

give up the nobility of the word “ethics” to the reduced

significance of a set of rules. In my opinion, however, the change is entrenched

among many practitioners and, thus, may as well

be acknowledged. If this were

agreed, at least the confusion between ethics and values as concepts would be

reduced.

The survey that I conducted places a deliberate emphasis upon values

as distinct from ethics. Values are said to underlie our behaviour

and are

assumed, therefore, to have great influence over us; they are rarely discussed

with any precision, however.69 Values have been

variously defined,70 and it is important to distinguish

between different types of values. Personal values71

(for example, honesty) can be distinguished from economic, aesthetic, and even

recreational values. Personal values may overlap fundamental

moral values. Thus,

honesty intersects with the moral values of truth and justice but is not

identical with these concepts.

In this research, I have focused upon

personal values because, in my opinion, survey respondents would be able to

identify more closely

the questions asked about values. Ethics, in my opinion,

have been discussed to the point where they are now, regrettably, confused

with

specific rules of conduct. While ethical behaviour has been understood as a

“positive,”72 ethics is now more often

associated with a negative “do not.”73

Thus, exhortations to lawyers to behave ethically might therefore fail to

improve lawyers’ behaviour – in the same way,

I believe, that a

parent who routinely criticises a child has less impact on the child’s

behaviour than the parent who praises.

The parenting analogy may be trite and

perhaps patronising, but my hope is, nevertheless, that a discussion about

values (as a “positive”74) will in some way

lead to a deeper examination of motives.

Values, as distinct from ethics as I

have defined them, are, nevertheless, also likely to lose their educational

impact if they are

defined narrowly in the MacCrate sense as professional

values. To define the values which lawyers need in terms of the professional

role alone suggests that personal values can differ or be ignored. This is

dangerous because many personal values such as honesty

are fundamental to

lawyering.

MacCrate is not alone here at what I believe to be a dead end.

The progressive Clinical Legal Education Association in the United

States

continues to talk only of professional values.75 I

suggest that only by personalising values, appreciating that they compete

and operate at several levels, will they retain their potency. Thus, in this

survey, I considered

it desirable to, in effect, force upon respondents choices

between personal and professional obligations in order to minimise (merely)

“intellectual” responses and, at the same time, maximise the chances

that the answers given would be predictive of actual

behaviour. In my opinion,

it is no good for example, emphasising to a law student (or newly admitted

lawyer) that there is a professional

value to promote justice and fairness in

the legal system76 if, at the same time, there is no

attempt to explore what this really implies for honesty

and/or77 integrity at the personal level.

Instinctively, students who become personally involved in a well-run

(live client) experiential learning process know that this sort of discord is to

be explored rather than simply

swallowed.78 As

Hutchinson says,

The challenge is to integrate the demands of a professional role with the

dictates of a professional morality and be able to construct

important bridges

between the two so that they can each support and fructify each other: one feeds

off the other.79

Thus, for example, the value of striving to support the

Rule of Law80 through the right to adequate

representation (as a guarantee of impartiality in a democracy) is difficult to

attain without first

reinforcing the personal values of courage and

perseverance.

Personal values are not one-dimensional. Differing values

constantly compete for dominance; they tend to be ranked in their impact

upon us

and can be a mixture of both “bad” and “good.” One

useful categorisation81 divides personal values into

foundational values (addressing basic needs for survival), focus values (daily

concerns for identity,

work, and self worth), and future values (at the

aspirational or noble end of behaviour). Under pressure, we tend to regress

towards

personal values that help us survive. If survival is assured, the

potential emerges for growth towards the aspirational

values.82 It is these higher level personal values to

which law students and lawyers can often aspire, and not just because their

basic needs

have been met through, for example, the accidents of birth,

ethnicity, or class. Students with and without privileged backgrounds

are often

zealous in their efforts to “do justice.” Of course, it is not easy

to “allow” students (in the

facilitative sense) to recognise that

the practice of aspirational values combined with the provision of

competent service is linked to the achievement of their basic and everyday

needs

(since quality/best practice approaches often attract respect and the referral

of new clients83), but the potential is there for law

teachers to exploit.

Hutchinson sees the context for this opportunity:

Mindful that ethical training is primarily concerned with learning about

oneself, students need to confront ethical dilemmas in concrete

circumstances in

order to begin to discover (or construct), question, and articulate their own

moral views before they struggle with

the complex demands of a professional

ethic. . . . A pervasive difficulty in achieving this is that

legal ethics is more about responsibilities

than rights and, therefore, does not

sit easily or well with much of the legal education that lawyers

receive.84

Experiential teaching and learning

methodologies – particularly those where law students assume

responsibility for assisting

real clients – can ignite the moral

imagination of our future lawyers. They provide students with an opportunity to

behave

in legal practice in a morally aware manner.85

If the need for major improvement in lawyers’ values awareness can be

quantitatively demonstrated, a fundamental change in legal

education is more

than a possibility. That demonstration is the purpose of this article. There are

measurable differences in values

among lawyers and law students. These

differences may not all be statistical significant, or yet capable of

international application.

Nevertheless, the values exposed in the survey which

follows come out of a carefully designed methodology.

WHY MONASH LAW GRADUATES?

I decided that a useful pilot process for a large international comparative

survey could be undertaken with former Monash law students.

The Monash alumni

lists, which are maintained by the University, provided a convenient and

relatively low cost access route to the

addresses of students who graduated over

the past two decades. Unlike graduates from many other Australian law schools,

approximately

one-third of these respondents would likely have completed an

undergraduate clinical experience and, thus, could help determine whether

there

is any significant connection between clinical experience and values

awareness.

Monash University has for 21 years provided an extensive

live-client clinical experience. Since 1990, it has attempted to give some

of

its clinical students the opportunity to work systemically on socio-legal

issues86 that arise in that programme. Anecdotal

student reaction to the systemic exposure has often been very positive. Although

the emphasis

of the entire programme has favoured the functional clinical norm

– reflecting the traditional professional emphasis upon competence

in the

context of practical skills – in recent years this has expanded to include

an ethical sensitivity in keeping with growing

community pressure for greater

accountability among lawyers.87

It has,

accordingly, become important to ascertain whether there is as yet any

observable effect of the clinical process on the development

of law

students’ values. If, for instance, some connection of this sort could be

demonstrated, law school deans, admitting

authorities, and regulators would have

available, for the first time, a reliable way to inculcate, via the

clinical process, ethics in that part of legal education which seems to so

readily excite student interest.

Methodology

This survey obliquely measures lawyers’ values;

its conclusions are based upon the responses from former law students to survey

questions. Rather than directly ask lawyers about their values, which seems

naive and may be treated dismissively by some respondents,

I decided to use the

psychological and educational device of the hypothetical situation, adding a

personal dimension to each scenario

to further reduce the level of abstraction

and assist in actual values identification. Since the scenarios were also

reasonably commonplace,

I reasoned that a degree of personal identification with

the lawyer’s dilemma that is raised in each scenario would emerge.

I

considered it unlikely that respondents would reply with sufficient thought to a

telephone survey. I believed that a lengthy explanation

of the survey, which

advised potential respondents about how their information would be used, had to

precede the questionnaire if

it was to be conducted ethically. I believed that

respondents would not easily comprehend the approach of the questionnaire or

feel

like cooperating with the necessary time that a verbal explanation would

require – even if survey funds permitted such contact

and the inevitable

telephone reminder calls. Nor did I think that focus group interview

methods88 were appropriate for a pilot process that

would seek maximum quantitative information, in order to pave the way for

subsequent, more

extensive research.

While technically I could have selected

a random sample from the entire Monash graduate population over the relevant

period, this

would have involved extensive and costly tracing of

“missing” graduates.89 For a pilot survey,

the costs/benefits favoured a large sample size generated by simple reliance on

the alumni lists. In this survey,

I hoped that, in addition to preliminary

findings on general values and the possible “clinical link,” I would

obtain

useful design information for future large-scale random sampling, if

adequate funding were to become available. Within the survey

as a whole, several

indicators referred to below suggest that the sampling decision was

reasonable.

Question Design and Delivery

At the heart of the survey instrument is the

structure of the eleven individual questions. These were based on scenarios that

I designed

with deliberately personal implications arising from common

experience of practice. By this I mean that I believed that respondents

would

find it difficult to respond to the hypothetical from just a

“professional” perspective. I included varied fields

of practice

– commercial, family, and criminal – to cater for different

professional experiences. The initial drafts

were trialed with a group of 30

hand-picked practitioners and academic lawyers in order to minimise obvious

ambiguity. I chose this

trial group because I knew them to be insightful and by

nature inclined to approach the task of refining the scenarios thoughtfully.

After their initial comments were used to modify and refine the questions, a

consultant survey designer90 assessed each question,

the practitioners’ comments, and the overall survey approach to validate,

vary, or reject the text

of each question. While no scenarios were specifically

rejected, the number of questions were reduced to minimise repetition as a

result of the consultant’s input. In some cases, the consultant’s

report recommended that the scenarios be simplified

in order to make choices

more straightforward; however, I decided in some instances to retain multiple

issues within individual questions

in order to reflect the reality encountered

by practitioners, even at the cost of possible confusion of the respondents.

This decision

was taken in the knowledge that the target population is

sophisticated and could be regarded as skilled in balancing competing loyalties

and pressures. Questions were worded to ensure that the principal actor in each

scenario could be male or female in order to minimise

variability in response

due to gender.

Approximately 38% of all respondents had completed a course in

Clinical Legal Education during their degree. This percentage is similar

to the

participation rate of all students in the clinical programme at Monash. Since

one objective of this study was the identification

of values in graduates with

clinical experience compared to those with none, adequate representation of

clinically experienced graduates

in the sample was crucial, and it was achieved.

The similarity of these percentages supports the view that the sample is likely

to

be representative of the population for the specified period.

At the

completion of spreadsheet coding, which converted text responses to pre-defined

numerical codes, I determined basic frequency

distributions (ie bar graphs

showing the raw numbers of responses in each category of answer) using the pivot

table and graph functions

of MS Excel. Statistical analysis using

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Software was also

performed. Although the sample, as discussed above, was not random, I believed

that the characteristics of the sample were

sufficiently robust for this

analysis to be of use.

Statistical Methods and Tests

In this section I describe the techniques and methods

that I used to generate and analyse the information that I received from the

respondents. As noted above, 30 participants helped to refine the draft

questionnaire. Four thousand (4000) questionnaires were dispatched

to law

students who graduated in the period 1980 to 1998. This number was selected on

pragmatic grounds; it represented a balance

between the cost of the distribution

and reliability of alumni contact details. Seven-hundred-and-three (703)

responses were received

in the period of three months, and of these, 644 were

considered valid in all respects: therefore, for this group, all questions

were

sufficiently completed to warrant coding in an initial spreadsheet. Fifty nine

(59) respondents omitted some answers or submitted

answers that could not be

coded with certainty – not apparently in any pattern – to various

questions. Where respondents

among this second group had completed clear answers

to questions, those answers were coded into the spreadsheet. These differences

account for the slight variability in the number of valid responses to different

questions, as is apparent below. The ratio of 59

incomplete responses to 703

total responses meant that there was a consequential 8.4% overall error in total

responses. I stress,

however, that the responses coded and reported in this

article were assessed for completeness before coding in relation to each

question

analysed.

It might be speculated that those who chose to respond

were sufficiently interested in the issues and that the very large group which

did not respond could contain a higher proportion of individuals with

“bad” or apathetic approaches to moral issues and,

perhaps, ethical

decision making. If this were true, the reliability of this survey would be

questionable. However, I do not think

this conclusion is valid as will be seen

below. There is, on nearly every question, a profound variation in responses

between what

might be described as “good” and “bad”

approaches to values choices.

In order to check for accuracy and internal

consistency in responses, that is to limit the opportunity of respondents to

give answers

that the respondents themselves might assume were

“desirable” in some way, I asked all respondents to complete a

standard

Rokeach Values Survey (“RVS”).91

This instrument is well known in sociological

research.92 It asks respondents to answer a standard

set of apparently unrelated questions about personal values. I inserted it in

the survey

document as a “Part B” questionnaire after the

“Part A” legal scenarios.93 Answers to

“Part B” values questions could be coded in such a way as to

indicate the underlying preferences of respondents

for particular contrasting

values. The nominated RVS values categories are either

“Instrumental” (that is, of “day-to-day”

relevance) or

“Terminal” (that is, of “ultimate” or long-term

significance). The distinction between the

two categories is made to cover both

the immediate and long-term preferences of respondents.

As can be seen in the

footnote below, the layout of the list of RVS values is not apparently

subdivided in any way and gives no immediate

clue to respondents as to any

so-called “desirable” set of choices, in order that the recorded

choices actually reflect

the views of respondents. In fact, in the footnote,

“Instrumental” values appear in column one and

“Terminal”

values appear in column two. Unless respondents are

familiar with an RVS, they would not likely be able to predict which values

might

be “required.”

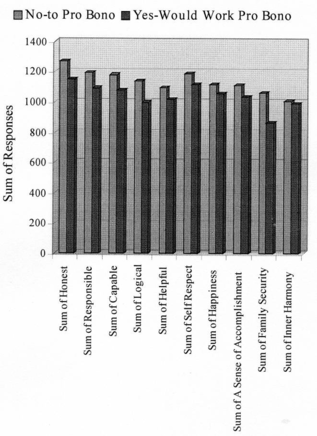

It is common in RVS analysis to encounter

all respondents giving priority to the same values for the first three or

four choices so that, for example, “ambitious”

might receive 1047 as

a sum of responses, followed by “logical” at 967,

“independent” at 832, and so on in

descending levels of magnitude.

Often, it is only at, say, the fourth or lower level of magnitude, where

differences in values become

evident. Thus, in the analysis below of whether

lawyers would choose a pro bono opportunity or work towards their

promotion by putting in longer billable hours, the first three values chosen for

both groups of

respondents in the “Instrumental” category were the

same. However, the fourth most important value for the group choosing

pro

bono was “helpful,” while “logical” was chosen by

the group which preferred extra work for the employer.

The “Part

B” instructions ask for RVS choices to be made in the context of

respondents “approach to the practice

of law. . . .”

This instruction allows the sum of responses to “Part B” RVS values

choices to be connected to the

sum of responses to the “Part A”

legal scenarios. After RVS values choices are coded and preferences divided

among the

available options, it is possible to gauge if the responses to

“Part A” legal scenarios are likely to be valid, that

is, accurate

and internally consistent with one another.

As a general result, from

“Part B” respondents in fact gave most weight to

“honesty” (Instrumental) and “self

respect” (Terminal)

ranging down to those considered least important – in comparative terms

– “self control”

and “equality” respectively. As

will be seen below when answers to individual Part A legal scenarios are

considered,

analysis and comparison between responses to Parts A and B of the

whole survey indicated a high level of accuracy and internal consistency

among

respondents.

Three specific tests of statistical relationship were used in

the analyses. Pearson’s Chi Squared Test of Association

(λ) is a standard descriptive statistic.

It was used extensively in the analyses to determine if a hypothesised

relationship between

two factors, for example, between gender and an interest in

doing “good (legal) works,” existed or not.

λ shows the strength of association

between two variables. The lower the λ

value, the smaller the association and vice versa. A high level of association

does not necessarily confirm a causative relationship between the two

variables (in either direction), but it is indicative of some causative

effect.

A UnivarateF analysis was performed in some questions to measure the

connection between variables. The UnivariateF test has a similar

purpose to

λ and was used to provide additional

support for any likely correlations. It is a variety of the Multivariate

Analysis of Variance

(“MANOVA”) mathematical procedure and measures

mean (average) differences between test results to determine the strength

of

their relationship to one another.

A correlation matrix was also used in

some analyses. This technique allows correlations between more than two

variables to be compared

in a table, indicating which relationships are

significantly related.

RESULTS

Basic Statistics

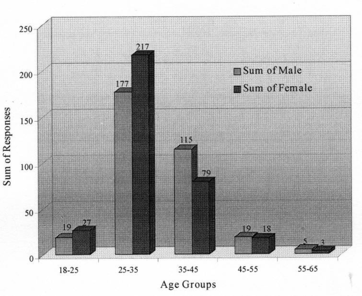

Three-hundred-and-forty-four (50.66%) females and 335 males (49.34%) completed the survey sufficiently to allow coding of responses. This balance in gender responses is important because, although the sample was not random and was, in effect, self-selecting, it mirrors the general population. The reasonable inference from the size and make-up of the sample is that it is a reasonable predictor of population responses, subject to the issue of the age of respondents. The age distribution, segmented by gender, was instructive: [see Figure 1].

Figure 1: All respondents –Segmented by Age and Gender – Males Dominant with Age

As may be observed, most respondents fell within a 25-45 year old age range.

Most of these were in the younger range of 25-35 years.

Males tend to dominate

in the sample in the older groups, perhaps as a function of the reputed

“glass ceiling” which

appears to operate in

law94 or perhaps because women in these age groups are

likely to be concentrating on families. It is also possible that the sample is

skewed

against older respondents because Alumni records are more likely to be

accurate for more recent graduates. As a result, the frequency

distributions for

the older age groups do not, in this pilot,95 contain

enough responses to assess whether their patterns of response differ markedly

from younger graduates. It is, however, fairly

clear that responses from

respondents in the younger age groups are adequate to measure their impact for

the population in those

groups.

Graphic representations of

respondents’ gender, segmented by occupation, ethnicity, year of

graduation, and parents’ occupations,

indicate that respondents as a group

were dominated by solicitors who considered themselves “Australian.”

The term “Australian,”

while imprecise because of the tendency for

respondents from families where parents were born overseas to identify with more

than

one background in varying circumstances, was a categorisation that could

not be excluded. Female solicitors (197) overall slightly

outnumbered their male

counterparts (183) – especially among recent graduates – however,

male barristers (49) easily

outnumbered females (14). Most respondents (399) had

parents with professional, teaching, or business – what might be

considered

as “middle class” – backgrounds, compared to the

total of 679. All in all, the profiles of respondents –

relatively

“comfortable,” – practicing lawyers – are unsurprising

and are consistent with anecdotal information

and demographic snapshots of

Victorian lawyers.96

In the subsequent analyses of

“yes/no” choices in relation to individual questions, it is most

interesting that the values

of self-control and equality are consistently

more or less important for particular choices. This is to be expected if

respondents are answering the survey questions in an internally

consistent

manner. Thus, for example, in the question designed to discover how many

graduates thought lawyers’ pro bono activities important, those who

answered “yes” often gave a higher weighting to the RVS value of

“equality”

in preference to “self-control.” Repetition

of similar patterns across different questions provides a key validator

indicating

that respondents in the sample were answering questions carefully.

Frequency Distributions and Tests of Significance of Answers to Each Question

In the following description of results, answers to

separate questions are analysed and the main findings stated for ease of

understanding

in relation to that question alone. Further, questions which could

be expected to produce answers which may bear upon one another

are dealt with

immediately afterwards in this article rather than in the order that the

questions were asked. Not all questions are

reproduced here for reasons of space

and because some tend only to confirm broadly similar information. Frequency

distributions performed

for responses to specific questions are available from

the author. A summary of findings and of conclusions drawn from those findings

appears at the end of this paper.

Demographic information of the sort

represented in the graph above was available for cross-tabulation against

answers to all questions;

however, as will be seen in relation to the answers to

Question 1 (“Q1”) below, such information is of minimal use because

the number of responses in sub-categories are, in most cases, too small to

permit extrapolation to the population (that is, to all Monash law

graduates). Accordingly, while answers to Q1 are canvassed extensively to

illustrate this point, in succeeding questions

only a selection of all

distributions calculated are discussed in order to save space and avoid

restatement of similar information.

I consider those chosen for reproduction

here to provide useful insights.

The text of the chosen questions, which were

preceded by a set of instructions,97 are set out as

they appeared in the survey document and are followed by individual analysis.

“Corporate” or “Justice” priorities

Question 1 – “Corporate” or “Justice” priorities

You are a solicitor working in a large commercial law firm. The Public Interest Law Clearing House (PILCH) approaches you to work on a prominent test case about women who kill in self- defence. Your interest in this area is well known. The work would be pro bono and very high profile for you personally but of little interest to your firm. The matter requires a lot of time and work. Your senior partner however wants you to increase your billable hours for the firm. The firm does not usually do any pro bono work but there is no actual policy against it. Your time is currently so limited you could only realistically do one or the other.

Would you agree to work on the PILCH case? Y or N

Motivating Value Weight

0 1 2 3 4 Business Efficacy (Firm’s Profit)

0 1 2 3 4 Employer Loyalty

0 1 2 3 4 Access to Justice

0 1 2 3 4 Professional Ambition

0 1 2 3 4 Employment Security

Response to Q1

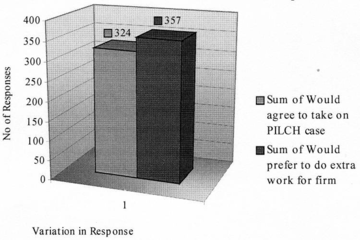

There was a slight preference among respondents for “extra work for the firm” (52.2%), thus respondents declined the pro bono request [see Fig. 2]. As the sample size is reasonable in the younger age groups, it is safe to conclude that, in respect of this scenario, younger Monash graduates in law are fairly equally distributed between those who care to some extent about the public good and those who may not care as much. While it could be thought that they might also care equally about both had they a job with some security, it can be argued that the sample size is large enough to contain respondents from both categories and to balance out the differences that might be caused by this factor.

Figure 2: Slight Preference of Respondents to Do Extra

Work for Firm and to Decline Pro Bono Request

This result also appears to indicate that there is

significant hesitation, possibly even a lack of sufficient interest, in working

for the public good. Given that the scenario balances the cost/benefit of the

pro bono opportunity in such a way as to identify employer reluctance

without confirming it, this decision points towards a substantial values

“gap” or difference. The implicit, though largely

anecdotal,98 assumption that Australian lawyers hold

homogeneous values is, therefore, not supported by this evidence.

However,

it may be thought that if about half of all respondents are interested in the

public good, Monash alumni (at least) have

“good”

values.99 This is, it seems, the view taken by the Law

Institute of Victoria (“LIV”), which considers that there is a

substantial

pro bono commitment by the Victorian profession as a whole.

In the only other recent survey published of Victorian legal practitioners in

relation to this issue, a study by a research division of LIV indicated that

53.2% of the 32% who responded to the survey (2684 responses

to 8500

questionnaires) handled one or more pro bono matters in the previous 12

months.100 To the extent that this result of the LIV

survey is consistent with a central prediction of this survey – that there

is a link

between values and “justice” behaviour – it seems

likely that, in future, parallel investigations of lawyers’

behaviour

– ideally by collaborating law societies – will be useful to test

for the existence of a causal relationship

between values and actions.

Interestingly, however, the LIV finding was qualified by the statement that

30% of the respondents declined to answer the question.

The discrepancy in

results between this investigation and that of the LIV is perhaps, in part,

explained by the response failure:

most other questions put by the LIV –

concerned with areas of legal practice, remuneration, hours of work, and other

matters

associated with awareness of professional services to members –

were answered fully.101 It is difficult to see why a

respondent to the LIV survey would not be willing, even confidentially, to

record his/her participation

in pro bono activity. It is fruitless to

speculate too much, but, since a 30% nil response may well be composed of

persons who had no pro bono activity, the LIV survey may be significantly

over-recording actual pro bono participation. Accordingly, the responses

in this study may be closer to the reality of actual pro bono

participation.

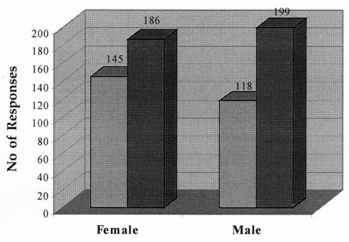

Another note of discordance between the two surveys concerned

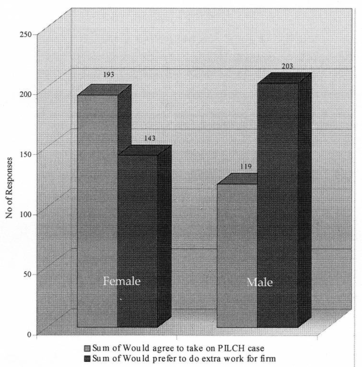

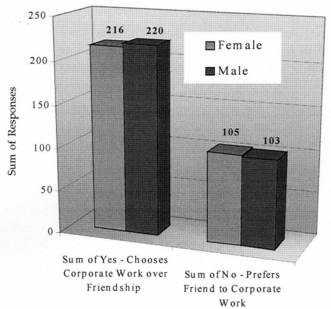

the gender split in relation to pro bono activity. While the LIV

cautiously observed102 that more males than females

were engaged in pro bono work, the study that surveyed only Monash

graduates reached the opposite conclusion [see Figure 3].

Figure 3: More Females than Males Would Participate

in Pro

Bono Activity

In this question, Pearson’s Chi Squared Test of Association

(χ2) expressed in standard statistical notation

for this association as: χ2(1) = 28.10, p =

.0000001 – showed a highly significant association between gender and

whether an individual would choose to

do PILCH work. The correlation here is

sufficiently strong to assert that females indicate that they are far more

likely assume pro bono work. The relationship between gender and the

decision taken is evident throughout this study and, in the light of the LIV

findings,

is clearly an issue that would benefit from further study.

It is

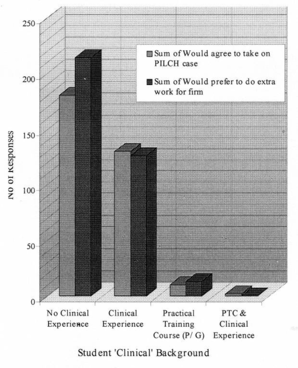

interesting that in the Monash survey of those who did have a background with

clinical experience, a slight majority indicated

that they would have chosen to

do pro bono work. In itself, this is unlikely to be significant. However,

the difference in decisions indicated by the respondents emerges when

the

numbers who had no such background are examined [see Figure 4]. In the group of

graduates without any clinical exposure, a larger

number chose “extra work

for the firm.” Taken together, the differing responses recorded for the

two groups point to

some relationship; however, the result is not statistically

significant (χ2(1) = 1.67, p = .20) to demonstrate

a relationship between a clinical education experience and a decision to

undertake public interest

work. This relationship also requires further detailed

exploration.

Figure 4: Minor Positive Relationship between Clinical Experience and “Yes” Decision re PILCH Work

In assigning relative importance to particular “legal” values as

decision motivators, all respondents behaved consistently

regardless of gender.

“Access to Justice” was important for those who selected pro

bono activity as their priority, and “Employment Security” was

most important for those who chose extra work for the firm.

The only obvious

variable was the decision itself to opt for public interest work or not. When

the responses for “marital status”

and the existence of children are

added to the analysis, it is notable that, while married respondents are

slightly more inclined

to choose extra work for the firm rather than pro

bono activity, the existence of children appears to have no effect on the

decision indicated.

A higher number of respondents among those who opted for

“extra work for the firm” had parents whose occupations fell

into

business categories. Otherwise, the primary decision had little statistical

association with parents’ occupations (χ

2(1) = 10.88, p = 0.14). Professional, academic, and business backgrounds

were dominant in both cases.

A comparison of ethnicity and parents’

occupations was not conclusive, presumably because the number of responses from

non-dominant

cultures is again too small (χ2(1) =

.21, p = 0.65). Correspondingly, it is clear that respondents have very

pronounced Anglo-Saxon or Anglo-Celt heritages. Occupational

grouping did not

appear to make any difference to the size of the “yes” and

“no” camps, with solicitors accounting

for over half of all

occupations in each category.

Reference has already been made to the Rokeach

Values Survey and to its crucial role in validating respondents’ answers

in the

section on methodology above. In this question, as in the survey as a

whole, a comparison of responses between the scenarios and

the RVS values

reveals a pattern which is consistent with the

“Yes”/“No” choices made by respondents [see

Figure 5].

Thus, the three most important RVS values to all respondents, whether they were

in favour of Public Interest Law Clearing

House (PILCH) work or not, were

identical. Importantly, this observation is true for both Instrumental as well

as Terminal values

in the RVS. Among the “Instrumental” values

group, the first three most important values to both “yes” and

“no” respondents were “honest,”

“responsible,” and “capable,” and in the

“Terminal”

values group, the first three most important values were

“self respect,” “happiness,” and a “sense

of

accomplishment.” Thereafter, the relative importance of different values

to both groups began to diverge, indicating where

the real values difference may

be.

As illustrated in the figure below, in the “Instrumental”

category the fourth most important value for the pro bono group was

“helpful,” while “logical” was chosen by the group that

preferred to do extra work for the employer.

Among those who said

“yes” to pro bono work in the “Terminal” group,

the fourth most important value was “inner harmony” to be contrasted

with “family

security” for those who chose “extra work for the

firm.” These results tend to confirm that the “Yes/“No”

choices made by respondents to this question are valid and reflect personal

values underlying professional choices.

Q1: Key Instrumental and Terminal Values

[Rokeach Values

Survey]

Finally, a correlation matrix was developed to display statistically

significant associations between motivating “professional”

values

and RVS values. The use of the correlation matrix supported the primary

correlations, indicating that individuals who weight

“employment

security” as a motivating value in a decision about whether to take on

PILCH work will also be likely to

value “business efficacy” and

“employment loyalty” as important. “Family security” and

“a

comfortable life” correlate with their approach to the practice

of law. Similarly, “professional ambition” correlates

with

“pleasure,” “social recognition,” and “a

comfortable life” for these individuals.

The next scenario focuses on

an issue that has a very high level of professional recognition, irrespective of

clinical experience.

It highlights the importance of the use of the hypothetical

situation as an exploratory tool.

Denial of Legal Aid

Question 8 – Denial of Legal Aid

You are a Victoria Legal Aid solicitor handling criminal matters. You have just received a file to defend charges of child sexual abuse where the victim is the only witness. Your client denies the allegations. The alleged victim is 14 years old. Your application for aid is rejected and you are told informally the managing director of Victoria Legal Aid wants to change the grant guidelines to exclude any grant of aid for a matter that would involve the cross examination of an alleged child victim in a sex abuse case. You suspect the change is due to bad press attacking such cross- examinations.

Would you argue in writing within VLA against

this change in policy? Y or N

Motivating Value Weight

0 1 2 3 4 Employer Loyalty

0 1 2 3 4 Professional Ambition

0 1 2 3 4 Client’s Interests

0 1 2 3 4 Access to Justice

0 1 2 3 4 Employment Security

Response to Q8

In this question respondents were presented with a

relatively simple choice that centered around the availability of legal aid in

the community. It was to be expected that most would choose to retain aid

because, in the Victorian context, its availability has

been steadily reduced in

recent years, and this has produced much criticism in the legal profession.

Thus, among the “retain

aid” majority,

UnivariateF103 tests place “access to

justice” and the “client’s interests” as the principal

motivating values.

It was considered possible, however, that the subsidiary

issue of sensitivity to victims of sexual assault might counter the legal

aid

emphasis, particularly if women were strongly represented in the sample. Of

considerable interest is that, although female respondent

numbers were well

represented, females were in the majority among the, admittedly, small

number of those who would deny legal aid. As may be observed below, these

respondents placed reliance

upon “access to justice” as their

motivating value. UnivariateF analysis confirms “access to justice”

as

the value that motivates women to deny aid, while men were principally

motivated by “professional ambition.” Pearson’s

Chi Squared

Test of Association analysis confirms a significant association between gender

and choice, with males being more likely

to indicate that they would retain aid

(χ2(1) = 11.26, p = .0008).

This result may

indicate a definitional and, in fact, a political issue with the terminology in

this question. Nevertheless, the corresponding

chart for those who would allow

aid indicates that women in that group were also clear that “access to

justice” was quite

important to their decision. In fact, among both males

and females who would retain aid, “access to justice” was their

prime motivator. In this question there appears to be little impact attributable

to clinical experience; this could be due to the

considerable profile which

legal aid has as an issue generally.

Comparison with the RVS values

responses shows a high level of agreement among those who would retain aid and

those who would deny

it. “Instrumental” values were identified as

the first five most important categories, while the first seven were identical

in the “Terminal” values sub-category. In the

“Instrumental” group, the divergence emerged at the sixth most

important value. Those who would retain legal aid chose

“broadminded” while those who would deny it settled upon

“self-control.”

In the “Terminal” group,

“equality” was preferred (at the eighth level of magnitude) by those

who choose

to retain aid while “true friendship” was chosen by those

respondents who would deny aid. Again, it would seem that uniform

personal

values among the “Yes”/“No” groups are the norm in

relation to this question, and divergence is

along expected lines.

The level

of consistency in the responses supports the contention that respondents are

identifying sufficiently with the scenarios

to give some confidence in the

results. Question construction (and, therefore, the precise situation in which

respondents find themselves)

is likely to be a crucial ingredient in exposing

differences in values.

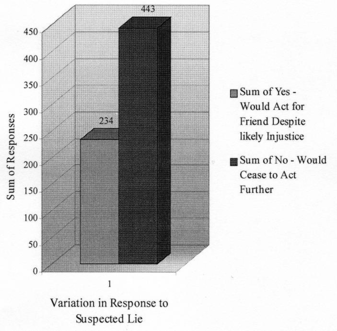

While the values of those who chose to deny aid may

be considered atypical, responses to the next question indicated that there can

be no easy conclusion that the clear majority of respondents who chose to retain

legal aid might therefore be considered to have

“higher” values.

Concealment of Defalcation

Question 3 – Concealment of Defalcation

You are the Senior Partner in the firm of AMBD. Your son is the junior partner in the firm. You discover your son has a minor gambling problem and has taken money from the firm’s trust account to cover his debts. Fortunately you discover the problem in its very early stages. Your son is now undergoing counselling for his gambling addiction and appears to be recovering. The amount missing from the trust account is relatively small and you are certain could be reimbursed without attracting any attention.

Would you report the matter to the Legal Practice

Board or Victorian Lawyers RPA? Y or N

Motivating Value Weight

0 1 2 3 4 Personal Obedience to the Law

0 1 2 3 4 Parental Loyalty

Response to Q3

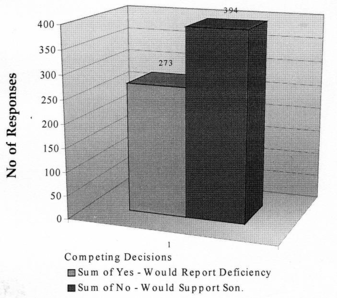

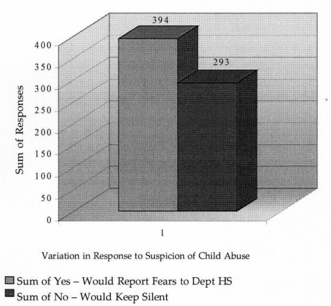

Despite an explicit obligation on all practitioners under the section 189 of the Legal Practice Act 1996 (Vic) to report a suspected defalcation, a clear majority of respondents (mostly males – see Figure 6) would remain silent. Although this is speculation, their response may be because of what appear to be good prospects for secrecy and their desire to protect their child rather than report the deficiency to the Legal Practice Board [see Figure 7].

Figure 6: Males More Likely than Females to Remain Silent than Report Deficiency in Son’s Trust Account

Figure 7: 3:2 Preference to Suppress Information on Trust Account Deficiency when Child would be Prosecuted

UnivariateF tests confirm what I had expected: that

“personal obedience to the law” is more important than

“parental

loyalty” among the minority who would report, and,

vice versa, among the majority who would remain silent. Interestingly,

Pearson’s Chi Squared Test of

Association analysis shows that gender is

not significant in the decision to report (χ2(1) =

2.91, p = .09). Among those who would keep silent, “spouse/parental

loyalty” and “personal happiness”

rated highly. Where

“silence” was preferred, it did not matter whether the respondents

were parents themselves. Among

those who have clinical experience, there appear

to be more respondents who would report a deficiency than remain silent.

However,

based on the insignificant results for any clinical effect in the other

questions, the small differences for this question in the