Legal Education Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Legal Education Review |

|

JURISPRUDENCE MEETS EPISTEMOLOGY: FACILITATING LEGAL UNDERSTANDING AND MEANINGFUL LEARNING IN LEGAL EDUCATION WITH CONCEPT MAPS

HEATHER ANN FORREST*

This article relates jurisprudential scholar Jack Balkin’s examination of the role of the individual in understanding law to the role of the individual in academic learning. It should be acknowledged from the outset that jurisprudence is ‘a particular method of study … of the general notions of law’.1 It concerns questions of what law is, not of how or why it is taught. Yet, as this article demonstrates, the two are not entirely unrelated, for how we define what law is affects how we understand law and, by corollary, how we teach it. The scope of this article is thus grounded firmly in the theoretical rather than the practical application of a particular epistemological framework to understanding law. The ultimate intention, however, is that this demonstration of the theoretical links between Balkin’s views on how law is understood and an epistemological theory on how legal knowledge might be acquired will offer sufficient justification for taking the next step of practical application in an undergraduate law curriculum.

Balkin proposes that in seeking to understand law we should begin not by asking questions about law or the coherence we as a society desire to attribute to law, but rather by asking questions about the individual who seeks to understand law.2 He suggests that without this focus, in jurisprudence, on the individual, we risk treating law and its coherence as something to be poured into the law learner as if he or she were an empty vessel. In this scenario, the legal academic’s role is reduced to that of a water carrier simply pouring the treasured liquid of legal knowledge and hoping that the vessel is able to retain it.

Implicit in Balkin’s rejection of such passive involvement is a suggestion that optimism is not, on its own, sufficient assistance or guidance to give to the law learner. This is particularly so if what is expected of the law learner is an ability not only to learn the words of statutes, judicial opinions and administrative decisions, but to apply those words gleaned from one set of circumstances to new and yet unknown circumstances. Law is dynamic and our understanding and learning of law must, of necessity, reflect that dynamism. Our understanding of law changes as law changes and, conversely, we change law.3 The dynamism of law is thus reflected in the individual’s continuously evolving legal understanding, with the result that understanding law is an ongoing, dynamic activity rather than a static, osmotic one.

If understanding law for the purpose of learning and being able to apply it is the active, dynamic and reciprocal activity Balkin suggests, then perhaps learning law is better facilitated by an active, rather than passive, approach. In other words, to teach law as if it were a static and passive body of materials and its coherence as something to simply be captured by the individual ignores the individual’s contributions to law and determinations of law’s coherence. Rather than pour the treasured liquid of law into what the legal academic hopes is a sufficiently receptive and sturdy vessel, perhaps he or she can better facilitate legal understanding by encouraging the activity, dynamism and reciprocity that Balkin proposes legal understanding demands. For some this imposes a shift in fundamental beliefs about legal education, while for others it may require little more than finding an appropriate tool.

It is prudent to acknowledge at the outset that the role(s) and goal(s) of legal education are universally, and in some cases vehemently, debated. The dichotomy in law school faculties worldwide pigeonholes (admittedly broadly and stereotypically speaking) those who aspire to produce graduates who ‘think like lawyers’4 and those who aspire to produce lawyers. The former is often linked to an analytical, critical mindset or unique way of thinking that goes beyond mere knowledge of legal rules, while the latter is often associated with a more focused approach intended to impart the practical skills associated with legal practice.5 In a critical evaluation of what it means to ‘think like a lawyer’, James Elkins debunks the idea of any such ‘distinctive way of thinking’ unique to law but maintains that ‘law teachers who believe they are doing something more than teaching legal rules’ could agree that ‘[l]earning the law is simple, understanding the law is difficult’.6

Recognising this potential for an ideological divide here is neither pessimistic nor cynical, but rather realistic, and it is with this reality in mind that this article has been prepared. Echoing Elkins’ comments just noted, this article relies on the belief that both camps may find common ground in the need to not just recite law but to understand it. A tool to facilitate legal understanding would serve both ends by producing competent lawyers who can apply the language of law to new factual circumstances in practice, as well as critical world citizens who question and contribute to the concept of law generally.

One possible tool is concept mapping, an epistemological method employed with success in other undergraduate fields of study. Concept maps are a visual, pictorial representation of what David Ausubel describes as the human cognitive structure, the network of knowledge stored in human long-term memory (LTM).7 The method relies heavily on Ausubel’s theory that assimilating knowledge into LTM requires active, conscious effort on the learner’s part.8 The process of making a concept map not only serves to record existing knowledge but also to facilitate assimilation of new knowledge. It also allows for the identification and modification of existing misconceptions in the existing knowledge foundation.9 The concept mapping method reflects the active, conscious, dynamic process that Ausubel calls ‘meaningful learning’.10

Balkin’s description of legal understanding as an active, conscious and dynamic activity shares distinct similarities with the epistemological principles underlying Novak’s concept mapping method. While their application to undergraduate and postgraduate legal study has not yet been documented, the common principles underlying Balkin’s jurisprudential theory and Joseph Novak’s application of Ausubel’s epistemological theory suggest the effectiveness of concept maps as a tool to facilitate what Balkin describes as legal understanding for the purpose of learning law and being able to apply it.

Part II of this article discusses Balkin’s views on the role of the individual in jurisprudence generally and law learning specifically. Part III explores Ausubel’s epistemological theory and its practical application in the concept mapping method as developed by Novak. Parts II and III together lay the groundwork for the comparative analysis in Part IV, of the conceptual links between Balkin’s and Ausubel’s respective theories, and, in Part V, of the potential that such links may have in terms of practical application in an undergraduate law curriculum. Finally, concluding remarks are presented in Part VI.

Central to jurisprudential thought is an attempt to define and understand law as a theoretical, functional and sociological concept. Just as it was prudent to acknowledge at the outset of this article the undercurrent of discord in questions of how and why law is taught, so too is it necessary to acknowledge the various ‘distinct communit[ies]’ of jurisprudential thought which are ‘in important ways inconsistent and incompatible with’ each other.11 These communities are said to be ‘distinguished by a distinctive set of underlying assumptions and beliefs, prime values and projects, centers of attention, intellectual affiliations, and styles of interpretation and argument’.12 While an identification and critical discussion of each lies beyond the scope of this article, a brief consideration of where Balkin fits helps to contextualise his views.

Balkin’s approach to legal reasoning can be called unique because it shifts the focus from law and the legal system as things to be apprehended to the individual and his or her ‘experience’ of understanding law, and purpose for doing so.13 In this view, theoretical questions of what law ‘is’ are seen to be answerable only with due consideration given to the individual attempting to understand law, and his or her purpose for doing so. Balkin is not the first or only legal scholar to scrutinise the individual. Hart notably considered the impact of an ‘internal point of view’ on acceptance of legal rules and social behaviour in the legal system.14 Balkin sees limitations in Hart’s approach, positing that the internal

perspective constitutes law rather than simply mirrors it … Instead of taking for granted the primacy of the internal viewpoint of participants in the legal system, a critical perspective asks how this internal experience comes about. It recognizes in the internal experience of legal norms an effect whose causes must be unearthed and reflected upon.15

The notion of the individual as it relates to questions of objectivity/subjectivity, human nature, order, reason and rule of law cuts across the various legal theory ‘communities’. Not surprisingly, then, there are those who challenge Balkin’s faith in individuals and their role and competence in legal understanding.16 Considered thus in context, Balkin’s reference to the individual is not itself unique and is a product of, and perhaps also a consequence of, his membership in the ‘community’ of contemporary critical legal theory.17

Balkin proposes that the individual’s purpose for understanding law affects his or her understanding.18 One such purpose is making ‘sense of the law in order to learn and apply it’.19 To achieve this end, Balkin advises:

We can memorize the elements of doctrines, but we do not truly understand them until we can apply them. We cannot apply them until we understand the purposes the doctrines serve. And we cannot understand the purposes the doctrines serve until we attempt to see why they make sense as a scheme of social regulation.20

When the law learner asks ‘What is law?’, Balkin suggests the answer lies well beyond simply knowing and reciting words of law. It involves making sense of a constantly evolving body of principles, policies and doctrines in an attempt to see individual parts as a coherent whole. This coherence is affected by law itself and the purposes and interests underpinning it.21 It is also affected by the individual, an effect that Balkin claims has been largely ignored in jurisprudential theory.

Balkin describes the activity of legal understanding as ‘subjective’,22 noting that when an individual seeks law’s coherence, they are influenced by personal perceptions of what law means to them and the cultural and sociological context in which law is meant to operate. By ‘subjective’ he is not implying that law is whatever the individual makes of it and therefore entirely dependent on the individual’s point of view.23 Rather, this ‘subjectivity’ encompasses the shared meanings and cultural understandings that influence the individual’s perception.24 This is the individual’s contribution to law as a whole. Ignorance of the individual and his or her contribution to what law is creates an obstacle to understanding law.25 Balkin chides his fellow jurisprudential scholars: acknowledgement of the individual’s contribution to determinations of legal coherence is an imperative rather than an ancillary consideration in the activity of understanding law.

Thus law’s coherence is not something that the individual simply ‘gets’. Indeed, Balkin characterises such assumptions as a mistake too often made in jurisprudential thinking, where the individual is portrayed as a ‘mere vessel into which the real content of a law independent of understanding is poured’.26 From this perspective, legal coherence is some sort of tangible thing — a quality or characteristic of law to be apprehended by the individual attempting to understand law. Such a view forces the notion of law as something that exists independently of, and without reference to or contribution from, the individual who seeks to understand it.

In Balkin’s view, law is not poured into a ‘mere empty vessel’ with the hopes that it might be retained. Rather, understanding law for the purpose of learning it and being able to apply it requires conscious engagement between the law and the individual attempting to understand law. It is a symbiotic process, ‘something that we do with and to the law, and through this activity, we ourselves are changed’.27 Legal understanding makes us ‘vulnerable’28 to this change, for the experience of seeking law’s coherence forces an individual to acknowledge existing incoherence and inconsistencies in the existing legal framework. Ironically, the more effort actually expended to understand law and to challenge its coherence, the less clear law potentially becomes.29

This is an experience with which all legal scholars, students and practitioners can surely relate: the sheer frustration that comes from the realisation that in law there are few ‘black letter rules’ and even these rules (should they exist) are subject to interpretation. The idea that doctrine applied coherently to one subject matter or area of law may not apply with equal coherence to another subject matter or area of law may even strike the law learner as unnecessarily complicating matters. This is, however, the manifestation of Balkin’s jurisprudential theory. There can be no static formula with which to respond to legal questions, because rarely are two legal questions ever indistinguishable and the perspective of the individual answering the question — his or her legal understanding — is also constantly changing.30

This act of understanding can certainly be viewed as an abstract activity confined to the theoretical sphere of jurisprudence, but it need not be so confined. If, in order to understand law, the law learner must do more than simply ‘memorize the elements of doctrines’, then law educators should be doing something to assist and facilitate that aim. If legal academics teach law as if it is something to be ‘grasped’ or captured rather than something to be understood, then the law school graduate sets out into the world lacking the skills necessary for a career-long scrutiny of legal coherence. He or she may be able to recite the facts and decisions of notable case law or statutory provisions, but unable to apply them to new and as yet unforeseen circumstances. Yet the ability to apply law to new circumstances is of utmost importance. Passive reception of the law without more, Balkin warns, is simply not sufficient to enable legal understanding.

If understanding law for the purpose of learning and being able to apply it is a dynamic, subjective, conscious activity, rather than a passive, osmotic acquisition of legal doctrine, this is support for teaching law in such a way as to encourage that activity. If, as Balkin further suggests, the individual’s existing understanding, experience and perceptions of the world in which he/she lives serve as a platform for new legal understanding,31 learning law may be facilitated by an attempt to identify the law learner’s existing understanding, experience and perceptions in order to use them as a platform for creating new legal understanding. Such an approach not only proactively encourages student understanding, but facilitates the more general and ongoing inquiry into the nature of law.

The distinction made by Balkin between passive memorisation or recitation and active understanding is by no means novel or unique to law or jurisprudential thought. It is a distinction which lies at the heart of Ausubel’s prominent epistemological theory. In The Psychology of Meaningful Verbal Learning,32 Ausubel posits that assimilation of new information in long-term memory (‘LTM’) is achieved when that new information is related to existing knowledge stored in the cognitive structure. The existing knowledge serves as a reference point for the assimilation of new knowledge. New understanding derives its meaning from existing understanding (a process Ausubel calls ‘meaningful learning’) and becomes woven into the fabric of existing understanding, available as a reference point for subsequent learning.33

Rote memorisation differs because no link is made between new information and the individual’s existing understanding.34 Without this link, the new information is stored in short-term memory without becoming part of the individual’s cognitive framework. Studies suggest a mere six to eight week retention time of information learned in schools by rote memorisation.35 Without reference to the cognitive framework, information ‘learned’ by rote memorisation has no meaning relative to existing knowledge and cannot be called upon or applied in new situations. By contrast, the clear advantages of knowledge stored in LTM are its availability as a reference point for new learning and its transferability to new situations and circumstances.36

Ausubel’s Psychology of Meaningful Verbal Learning is concept-driven, basing the individual’s ability to learn on a conscious choice to build upon the platform of concepts37 already understood by the individual. Knowledge acquisition thus described envisages a hierarchical approach: new knowledge is assimilated with reference to existing knowledge. Ausubel rejects correlations between ability to learn and age or formulaic stage in physical or mental development. This is a direct challenge to John Piaget’s widely held and strongly supported age-based cognitive development theory,38 as well as the theories of Lev Vygotsky, John Anderson and Robert Sternberg.39 Despite this, acceptance of Ausubel’s ideas is growing, particularly facilitated by the work of Novak and D Bob Gowin, who have given practical application to the theoretical principles of meaningful learning through the concept mapping technique.40

The concept mapping technique was developed in the 1970s by Joseph Novak and has been further refined and tailored in the years since by Novak himself, Gowin and others.41 Grounded in Ausubel’s epistemological theories, Novak intended for concept maps to be the visual representation of the hierarchical human cognitive structure — that is, the organised network of concepts stored in LTM.42 Concept maps provide a means of articulating a person’s understanding of a particular topic or subject matter in a diagrammatic format. In the map, the map maker identifies the concepts he or she considers relevant to the topic or subject matter and draws links between concepts to create a sort of pictorial explanation.

Novak’s idea of the concept map (notably a term he once owned as a trademark in the United States for use in connection with educational services relating to ‘structured representations of a field of knowledge’)43 is undeniably one of many so-called ‘mapping’ techniques, but it can be distinguished by purpose and structure. For example, the ‘knowledge maps’ described by Ronald Howard44 are primarily intended to ‘capture’ existing knowledge rather than facilitate the acquisition of new knowledge. Jamie Nast’s ‘idea maps’45 and Tony and Barry Buzan’s ‘mind maps’46 depict a question or idea at the centre of a diagram from which related (but not necessarily interrelated) thoughts and concepts appear to flower or radiate. Candace Schau and Nancy Mattern47 avoid strict adherence to hierarchy in organising the information presented in their ‘graphic organiser maps’.

A concept, by Novak’s definition, is ‘a perceived regularity in events or objects, or records of events or objects, designated by a label’.48 An example is the concept of a chair, the regular features of which include legs and a seat upon which to sit. Because concepts are derived from an individual’s perception, they will undoubtedly differ from individual to individual.49 One person may envision a plush surface, while another something hard; one person may envision something with three legs, while another something with a single post anchored by radial supports and wheels. On hearing the word ‘chair’, the mental image of a Queen-Anne-style dining chair may come to one person’s mind, while the same word may call to another’s mind the iconic Eames chair.

Each person’s perception of a chair draws from personal experience and existing knowledge, and therefore his or her respective articulation of the concept of a chair will differ accordingly. This is not to suggest that concepts themselves cannot be shared, but rather that the articulation of concepts in a map may differ. Considering the relationship between perception, experience and understanding50 and the relative complexity of the concept, the differences in maps may be relatively few across members of social or cultural groups. The potential for differing articulations of more complex concepts can be deduced from Figure 2 in Part V below.

While the information presented in a concept map may differ from individual to individual to reflect these differing perceptions, concept maps share the following general characteristics:

• They are hierarchical in structure; • They use linking words to describe relationships between concepts; and • They are dynamic.51

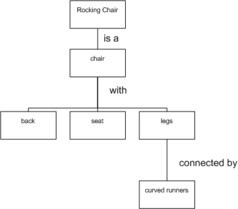

Concept maps have a hierarchical structure in order to mirror the hierarchy of human cognitive structure as described by Ausubel.52 Basic concepts are learned first and become the foundation for more complex learning.53 Complexity in this sense is a measure of how many other concepts need to be understood in order to give meaning to the concept in question.54 Raymond Nickerson describes this as ‘connectedness’: the more connections to other concepts a concept has, the more complex it is; conversely, the fewer connections to other concepts a concept has, the less complex it is.55 These distinctions are mirrored in Novak’s concept mapping method, where broad basic concepts are depicted at the top of the map and explained by increasingly interrelated or interconnected concepts below. Pursuing the chair example to illustrate this notion of complexity, the basic structure of a concept map is illustrated in Figure 1 below, in which the concept rocking chair is explained with reference to the concept of a chair and the key features of a chair.

Figure 1

Outlining the concept map creation process56 helps to further explain the three attributes of concept maps. The first step is to identify the subject matter to be mapped. Novak suggests describing the subject of the map as a question to be answered (for example, with reference to Figure 1 above: ‘What is a rocking chair?’). The next step is to generate a list of relevant concepts relating to the focus question. Novak specifically suggests that these be described in very few words in order to isolate specific ideas. The next step is to begin to structure the map by selecting the few broadest, most inclusive concepts to be placed at the top of the map. In Figure 1, the most inclusive relevant concept is that of a chair. If it is difficult to identify these, Novak suggests reflecting on, and perhaps redrafting, the focus question. Related sub-concepts, such as the back, legs and seat in Figure 1, should be placed under relevant broader concepts. The concepts should become increasingly specific working down the map. Lines are then drawn vertically to identify the relationships between higher- (broad) and lower- (specific) level concepts. The relationship between these concepts should be described or labelled with what Novak calls ‘linking words’. The linking words used in Figure 1 are ‘is a’, ‘with’ and ‘connected by’.

The map should be subjected to a continuous re-evaluation and reworking process. For example, new concepts may need to be added to sufficiently depict the relevance of other concepts. Existing linkages may also need to be broken and replaced with new linkages to more clearly or accurately reflect interrelationships between and amongst the various concepts in the map. The addition of horizontal links depicts relationships across different sections of the map and these can also be described or labelled with linking words. The result is a pictorial representation of the answer to the focus question. It is an explicit, visual articulation of the meaning the map maker attributes to the broad concept identified at the top of the map.

Continuous re-evaluation and reworking of the concept map is necessary because in the process of creating a concept map, gaps and ambiguities in existing understanding may be revealed.57 The incremental progress of an individual’s understanding on a particular topic or question can thus be represented in visual, pictorial form in a series of concept maps on that topic or question.

Jurisprudence is, it has already been acknowledged, the study of what law is rather than what is taught or how it is taught. Balkin’s approach grounds itself in a fundamentally different intellectual field of study than Novak’s. The path linking jurisprudence with epistemology generally is therefore by no means obvious and, likewise, the linking of legal understanding with meaningful learning/concept mapping is not without obvious challenges.

For a start, Balkin seeks to impress upon the legal community an appreciation of the ‘serious’58 nature of legal discourse and reasoning. Much debate has centred on this point,59 and the reduction of legal understanding to mere concepts depicted in hierarchical drawings may be fuel to this fire. Such challenges, and responses to them, would be buried deep in jurisprudential thinking, however, reflecting and perhaps reinforcing the different ‘communities’ of thought alluded to earlier.60

A related but broader concern is that although this article is specifically aimed at legal academics committed to conveying something more than mere legal rules and concepts, the suggestion of applying Novak’s concept-driven method in legal education could be seen as a step in the opposite direction. Returning to Elkins’ suggestion that ‘[l]earning the law is simple, understanding the law is difficult’,61 such a formulaic, hierarchical, rigid method could be seen as reinforcing ‘learning’ over ‘understanding’. This means of facilitating an understanding of core legal concepts could also potentially be used to the exclusion of other components of legal education, including social justice, legal practice skills, policy analysis, human nature and dynamics. Conceptually at least, Balkin and Novak seek something fundamentally more than rote memorisation. In the hands of those who share this aspiration, the hope is that this risk could be avoided and the approach used to broaden, rather than narrow, legal education.

The (certainly unintentionally) shared ultimate goal of legal understanding and meaningful learning facilitated by concept maps is individual empowerment. While the outcome of their focus on the individual may differ, Balkin’s and Novak’s respective motivations share a common bond. Just as Balkin challenges the image of the law learner as an empty vessel, Novak challenges such images of learners generally and with similar words:

The most important point to remember about sharing meanings in the context of educating is that students always bring something of their own to the negotiation; they are not a blank tablet to be written on or an empty container to be filled.62

Both legal understanding and meaningful learning require effort on the individual’s part in identifying existing knowledge and in the assimilation of new concepts with reference to that existing knowledge. In short, concept maps reflect the conscious, active, cognitive effort Balkin describes.

Likewise, both Balkin and Novak aspire to empower the individual based on a belief that the individual’s role in the process of understanding is paramount. Balkin’s approach to jurisprudence focuses on the individual and his or her purpose for understanding law. One of the key benefits he attributes to this approach is that it acknowledges the power that the individual attempting to understand law has over law.63 A clear correlation can be made to Novak’s belief that the ‘central purpose of education is to empower learners to take charge of their own meaning making’.64 Legal understanding is a conscious activity; it is not something one acquires. Similarly, new knowledge must be assimilated into existing knowledge and concept maps should be made, both requiring active cognitive effort.

From both the jurisprudential and epistemological perspectives, the key to empowerment lies in the individual’s conscious effort to understand. Concept maps may illustrate an individual’s existing understanding but their efficacy in terms of making use of that understanding to facilitate meaningful learning depends on the learner’s making a cognisant choice to do so.65 Novak acknowledges studies that suggest, however, that university students resist making this conscious choice, much in the manner of old dogs being reluctant to learn new tricks.66 This is because throughout their education, students are offered opportunities to (and in some cases even encouraged to) ‘learn’ through rote memorisation. Over time, the student accepts this as ‘how to learn’; new approaches to knowledge assimilation are thus viewed with scepticism as superfluous and unnecessarily labour intensive.

Despite these potential setbacks, studies demonstrate the successful implementation of concept maps in undergraduate and postgraduate education as subject-matter mastery aids to facilitate students’ learning of statistics,67 physics and mathematics.68 As a subject-matter mastery aid, concept maps depict the relationship between fundamental concepts in a given subject area and encourage the learner to assimilate and position new information into the framework of what they already know.

Schau and Mattern have used concept maps to mirror and facilitate the way in which they believe statistics is learned.69 They maintain that recognising and understanding the interrelationships between statistical concepts (what they call ‘connected understanding’) is necessary for students’ mastery of ‘effective and efficient statistical reasoning and problem solving.’70 Just as Schau and Mattern have described the subject matter of statistics as one based on interrelated concepts, so too can law be described as a network of concepts in accordance with Novak’s definition of that term. The idea that law is an immutable set of rules has been rejected in the Anglo-Saxon common law legal system, where law is ‘made’ not only by legislators, but by judges and juries and by society through its customary norms. The fundamental concepts of law and the legal system therefore evolve with the law and the legal system.

Certain legal concepts are familiar to the entry-level law student. Even non-lawyers have perceptions of what behaviour is legal and what behaviour is not. One American law professor calls these untrained perceptions, experiences and legal understandings ‘bar stool law.’71 Although this is perhaps poor word choice given the admonishment to acknowledge the ‘seriousness of legal discourse’, the professor’s point, as explored by Elkins, is that the ‘uneasy feeling that something should be illegal’ is a sort of foundation knowledge or understanding upon which legal education should build.72

When a legal academic lectures on a topic of law without any attempt to acknowledge or utilise the law learner’s existing perceptions, this notion of the learner of law as a ‘mere empty vessel’ is perpetuated because it relies on passive learning. If the predominant learning environment in legal education is passive, there should be little cause for wonder at law students and graduates who lack the necessary abilities to enable them to think like lawyers or to practise or otherwise engage with law in a competent manner. Yet rote memorisation of the law is a natural outcome if no attempt is made in the course of legal education to encourage meaningful learning. To use Balkin’s terminology, law memorised is not necessarily law understood.

Collective surprise, dismay and disappointment at law students’ inability to apply law are likewise ill-founded. Developing epistemological theory suggests that not only is Balkin correct to reject memorisation, but that there is a cognitive, physiological reason why law students who memorise law are unable to apply it to new factual circumstances. A possible link between jurisprudence and epistemology, apparently incongruent, becomes suddenly more clear.

Meaningful learning offers significant advantages over rote learning, including longer retention of knowledge, an increased ability to differentiate and thus integrate new knowledge and an increased ability to apply existing knowledge to new problems and contexts. Despite these advantages, meaningful learning as a means of knowledge acquisition requires more mental effort than rote memorisation.73 Existing knowledge must be actively called up in order that new knowledge can be assimilated. Students who have reached university- or postgraduate-level law studies without undertaking this level of effort are perhaps understandably suspicious of the need to make such an effort so late in their education. Yet, clearly, if law students are to enter the legal profession (in whatever capacity they may do so), they must be able not only to recite law, but to understand its purpose and apply it to continuously evolving circumstances.

To achieve this empowerment to facilitate and further legal understanding, concept maps should be made by — not for — the law learner. The legal academic must resist the temptation to simply provide the law learner with a pre-prepared concept map, because the pre-prepared map will reflect the academic’s existing legal understanding, perpetuating ignorance of the learner’s existing legal understanding. Novak and Gowin

[n]ote that we do not speak about sharing learning. Learning is an activity that cannot be shared; it is rather a matter of individual responsibility. Meanings, on the other hand, can be shared, discussed, negotiated, and agreed upon.74

The role of the educator in the context of concept maps is therefore as a facilitator. The learning environment is one in which learners are assisted in the acknowledgement of their understanding of a topic or subject matter, and that understanding is used as a platform for new understanding. This accords with Balkin’s emphasis on the ‘subjectivity’ of legal understanding as incorporating individual perception but also shared meanings and cultural frameworks.

The role of the legal academic as a facilitator of meaningful learning is therefore a critical one if students are to be encouraged to understand law and appreciate why they ought to be doing so. Legal academics arguably encourage passive, rote learning of law if they simply lecture on an area of law without linking that area of law to their students’ existing understanding. To offer new legal knowledge without helping the individual to put it in context creates an expectation on the part of the law learner that law and its coherence can be ‘grasped’ if one listens with sufficient diligence to lectures and reads enough case law. The law student waits passively for the meaning of law to ‘sink in’ and hopes desperately that this will happen before assessment. At the same time, the legal academic hopes blindly that the empty vessel into which he or she pours specialised legal knowledge will retain that knowledge, and then despairs if the vessel leaks.

Recognising the conceptual nature of law has two consequences relevant to both Balkin’s and Novak’s ideas. With respect to the former, it acknowledges the role of the individual and his or her perceptions in jurisprudential thought. In other words, the individual meaning-making process associated with understanding concepts supports Balkin’s view that the individual’s perspective contributes to his or her understanding of what law is. With respect to the latter, it gives rise to a suggestion that law can be learned conceptually and that the acquisition of legal knowledge can be facilitated by making concept maps.

Law school is not ‘the place where we find out what law is’75 but rather where we examine our own perceptions of law relative to others’ perceptions and arrive at shared meanings of what law conceptually is. In the early days of law school, the law learner’s so-called ‘bar stool’ perceptions, experiences and understandings should be identified and acknowledged, not ignored, in order that they can be challenged and modified to reflect new legal understanding. As the individual’s study of law and later practice of law progresses, this legal understanding is yet further challenged and developed and modified. The activity of legal understanding continues throughout the individual’s legal career, at the same time enriching the general body of understanding of the nature of law.

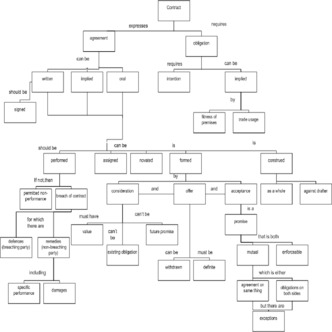

In a concept map of a question or area of law, basic legal concepts form the foundation for more complex legal concepts. The process of creating a legal concept map mirrors the meaningful learning process described by Ausubel and the activity of legal understanding described by Balkin. Figure 2 provides an example of a concept map of the question ‘What is a contract?’.

Figure 2

Interrelationships between related (and perhaps even seemingly unrelated) areas of law can likewise be depicted in a legal concept map. For example, a concept map of employment law concepts might depict cross-links to the legal concepts related to contract law because employment relationships are a form of contract in which one party agrees to perform a specified service for another. While there will certainly be disagreement over the categorisation of some legal concepts as more or less ‘complex’ than others, the notion of the ‘connectedness’ of legal concepts and subject matter, as in the example of employment law and contract, should not be controversial.

The interrelationships of concepts within a particular area of law form a micro-level map, while the interrelationships between different legal subject matters form a macro-level map depicting the more general topics of law and the law curriculum. In his writing on cognitive structure, Hausman uses a cartographic analogy, relating the macro-level to a state- or country-scale map and a micro-level to a city- or street-scale map.76 Recognising the links at both micro- and macro-levels facilitates the process of relating new information to existing understanding that constitutes Ausubel’s ‘meaningful learning’. New information is assimilated into LTM, from which it is accessible as a platform for future learning. Relating new legal concepts to existing understanding in a legal concept map helps to create a constantly evolving visual representation of the law learner’s understanding of specific areas of law, as well as of his or her ‘big picture’ of law and the nature of the legal system.

To identify and visibly express legal understanding, the means of expression used must have the ability to represent law’s dynamism. The dynamic nature of concept maps enables the depiction of the dynamic nature of law. As understanding changes, concept maps get rearranged. New knowledge is assimilated, while existing knowledge might be modified and previously unconsidered concepts or questions are revealed. When the individual creates a concept map of his or her existing understanding of an area or question of law, the differences between that initial map and subsequently created concept maps on that same area or question of law serve as tangible evidence of the law learner’s evolving legal understanding, and simultaneously of the dynamic nature of law.

Balkin seeks to explore what law is, not comment on how it is taught. However, his emphasis on the individual in jurisprudence rejects the image of the law learner as a ‘mere empty vessel’ into which the law, as an immutable set of rules and doctrines, is poured. From this perspective, the legal academic’s optimism as to the vessel’s ability to hold water cannot alone carry the expectations of society generally, or the legal profession specifically, that law’s participants offer more than mere recitation of statutory provisions and notable judicial opinions. If Balkin’s views on the role of the individual in legal understanding are accepted, the image of the legal academic as a mere water carrier must likewise be rejected.

It is simply not enough that society in general, and the legal profession in particular, desire that law and the legal system be coherent. Coherence is not an esteemed award bestowed upon those who complete a law degree or read enough statutes or reach some sort of longevity milestone in legal practice. Nor is it something that the individual attempting to understand law simply ‘gets’. It ‘is more than a property of law; it is the result of a particular way of thinking about the law. The experience of coherence is an activity of understanding…’77

Law students are ill-equipped for a career of participating in law’s coherence if they are taught the law in such a way as to suggest that they themselves have no impact upon that coherence. According to Balkin, legal understanding for the purpose of learning and being able to apply law is an active, conscious and reciprocal experience. Passive learning simply cannot achieve that end.

Meaningful learning, on the other hand, like legal understanding, is an active and dynamic experience. It requires that the individual make a cognisant choice to integrate new information into long-term memory, from which it is accessible as a reference point for new learning and transferable to new facts and circumstances. Meaningful learning of the concepts relevant to a question or area of law may help to facilitate the transferability of those concepts to application in other questions or areas of law. This transferability is absolutely critical in law because seldom are two questions or problems ever identical. The law learner questions the purpose and coherence of law in context and thus learns not only the words of law but gains insight as to how these could be applied to new circumstances. Concept maps are a visual, pictorial representation of an individual’s understanding on a particular topic or question, and evidence of the dynamic, hierarchical nature of that understanding

The relationship between legal understanding, meaningful learning and concept maps is supported by the similarity of their principles. They share a common focus on the individual and the power he/she has in understanding and learning, as well as a common precondition of conscious, active effort on the individual’s part. Where law learners are encouraged to engage in the activity of legal understanding, they are likewise encouraged to make the conscious choice to learn meaningfully. Conversely, where law learners are encouraged to make the conscious choice to learn meaningfully, they are encouraged to engage in the activity of legal understanding for the purpose of learning and being able to apply law.

The use of concept maps in undergraduate or postgraduate legal education has not yet been documented, but the commonalities underlying Balkin’s and Novak’s ideas suggest the effectiveness of concept maps as a tool to facilitate what Balkin describes as legal understanding for the purpose of learning law and being able to apply it. On this theoretical foundation, the author will progress to the next step, with practical application of the concept-mapping method in the undergraduate law curriculum. Should these conceptual, contextual arguments prove sufficiently compelling, it is hoped that other legal educators might also test whether concept maps’ rejection of rote memorisation furthers the sort of legal understanding that Balkin proposes.

The law learner is not a ‘mere empty vessel’ nor the legal academic Aquarius.78 Seen from this perspective, the role of the legal academic is that of a facilitator who helps the law learner articulate his or her existing legal understanding and embed new information within the human cognitive framework of that existing understanding. In the process, the law learner challenges and perhaps modifies the existing framework of understanding, and applies the modified form as a foundation for yet further new understanding. The individual is thus encouraged to see law not as a set of unrelated rules to be memorised, but as a network of interrelated concepts, the understanding of which is influenced by his or her perception of them. The information presented in the individual’s concept map pictorially depicts what happens, in Balkin’s view, in the conscious, active and dynamic experience of legal understanding: ‘To understand is to employ existing tools of understanding to create new ones or adapt old ones and, in the process, to be changed.’79

[*] Lecturer, University of New England School of Law, Armidale, New South Wales. This article has been prepared in connection with participation in the University of New England Graduate Certificate in Higher Education program, and the author wishes to acknowledge the guidance of Dr Belinda Tynan.

[1] George Whitecross Paton and David Derham (eds), Jurisprudence (first published 1946, 4th ed, 1972) 2.

[2] Jack M Balkin, ‘Understanding Legal Understanding: The Legal Subject and the Problem of Legal Coherence’ (1993) 103 Yale Law Journal 105, 105.

[3] Ibid 113 (suggesting that ‘[l]egal understanding is something that happens to us and changes us. It is a type of receptivity, of vulnerability, which affects us as much as it affects the law we attempt to understand’).

[4] James R Elkins, ‘Thinking Like a Lawyer: Second Thoughts’ (1996) 47 Mercer Law Review 511, 512.

[5] See, eg, Douglas D McFarland, ‘Self-Images of Law Professors: Rethinking the Schism in Legal Education’ (1985) 35 Journal of Legal Education 232 (further noting at 233 that ‘[a]rguments over theoretical, academic training versus practical, practice-oriented training have been advanced for at least three score years, with little ground gained or lost’).

[6] Elkins, above n 4, 514 (also suggesting that ‘most law teachers will not admit that their teaching is limited to conveying information about substantive legal rules’).

[7] See Joseph D Novak, Learning, Creating and Using Knowledge: Concept Maps™ as Facilitative Tools in Schools and Corporations (1998) 49–57. See also Charles Letteri, ‘Teaching Students How to Learn’ (1985) 24 Theory into Practice 112, 115 (describing the link between cognitive structure and LTM).

[8] Ibid. Novak, above n 7, 49–57.

[9] See Joseph D Novak & D Bob Gowin, Learning How to Learn (2004) 19; ibid 40.

[10] David Ausubel, The Psychology of Meaningful Verbal Learning (1963) 15.

[11] Gerald B Wetlaufer, ‘Systems of Belief in Modern American Law: A View From Century’s End’ (1999) 49 American University Law Review 1, 3.

[12] Ibid 5.

[13] Balkin, above n 2, 106.

[14] H L A Hart, The Concept of Law (2nd ed, 1994).

[15] Balkin, above n 2, 110–12.

[16] See, eg, Pierre Schlag, ‘The Problem of the Subject’ (1991) 69 Texas Law Review 1627; Pierre Schlag, ‘“Le Hors de Texte, C’est Moi”: The politics of form and the domestication of deconstruction’ (1990) 11 Cardozo Law Review 1631, 1639 (criticising Balkin’s reliance on the notion of the isolation, self-direction and coherence of the legal thinker ‘as if it were the autonomous author of its very own thoughts’).

[17] Wetlaufer, above n 11, 51 at n 209 of that work.

[18] Balkin, above n 2, 112.

[19] Ibid 129, 135.

[20] Ibid 156.

[21] Ibid 154–6.

[22] Ibid 107–8.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid 137.

[27] Ibid 106.

[28] Ibid 159.

[29] Ibid. He posits that ‘[o]ur judgments of legal coherence and incoherence are affected not only by our knowledge of legal doctrines, but also by the amount of cognitive effort we have put into considering the normative consistency among the doctrines we do know. After all, justifications that make sense to us at first glance often become problematic on further reflection, and vice versa’: at 138.

[30] Ibid 167.

[31] Ibid. He notes that ‘[o]ur experience of legal coherence is dynamic rather than static; it changes as we engage in cognitive work to understand legal doctrines and as we encounter new information and new experiences’: at 112.

[32] Ausubel, above n 10.

[33] See Novak, above n 7, 19–26 (describing Ausubel’s theory of meaningful learning).

[34] Ibid 19.

[35] Ibid 62, citing Howard Hagerman, An Analysis of Learning and Retention in College Students and the Common Goldfish (Carassius auratus, Lin) (Unpublished PhD thesis, Purdue University, 1966).

[36] Ibid 61.

[37] See notes 46–7 below and accompanying text.

[38]Jean Piaget, The Language and Thought of the Child (1926).

[39] See Novak, above n 7, 44–8 citing Lev Vygotsky, Thought and Language (1962); Lev Vygotsky, Thought and Language (1986); John Anderson, The Adaptive Character of Thought (1990); John Anderson, The Architecture of Cognition (1983); and Robert Sternberg, The Triarchic Mind (1986).

[40]Novak and Gowin, above n 9.

[41] See, eg, Novak, above n 7; Novak and Gowin, above n 9; Mary Kane Trochim and William Trochim, Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation (2007); John Nesbit and Olusola Adesope, ‘Learning with Concept and Knowledge Maps: A Meta-Analysis’ (2006) 76 Review of Educational Research 413; Marvin Willerman and Richard Mac Harg, ‘The Concept Map as an Advance Organizer’ (2006) 28 Journal of Research in Science Teaching 705.

[42] Novak, above n 7, 27–34.

[43] See United States Trade Mark Number 75230079, abandoned 10 March 1998 (accessible at <http://www.uspto.gov> ).

[44] Ronald A Howard, ‘Knowledge Maps’ 35 Management Science 903.

[45] Jamie Nast, Idea Mapping — How to Access Your Hidden Brain Power, Learn Faster, Remember More, and Achieve Success in Business (2006).

[46] Tony Buzan with Barry Buzan, The Mind Map Book: How to Use Radiant Thinking to Maximize Your Brain’s Untapped Potential (1994).

[47] Candace Schau and Nancy Mattern, ‘Use of Map Techniques in Teaching Applied Statistics Courses’ (1997) 51 American Statistician 171.

[48] Novak, above n 7, 22.

[49] See Raymond S Nickerson, ‘Understanding Understanding’ (1985) 93 American Journal of Education 201, 216. See also, Novak and Gowin, above n 9. They explain that ‘[t]he aspect of learning that is distinctly human is our remarkable capacity for using written or spoken symbols to represent perceived regularities in events or objects around us’: at 17.

[50] See Nickerson, above n 49, 222.

[51] See Kym Fraser, Student Centred Teaching: The Development and Use of Conceptual Frameworks (1996) 18 HERDSA Green Guides, 11–12.

[52] See Ausubel, above n 10, 79 (articulating the assumption that ‘an individual’s organization of the context of a particular subject-matter discipline in his own mind, consists of a hierarchical structure in which the most inclusive concepts occupy a position at the apex of the structure and subsume progressively less inclusive and more highly differentiated subconcepts and factual data’).

[53] See Novak, above n 7, 63–4.

[54] See Nickerson, above n 49, 231.

[55] Ibid 231–234.

[56] See, eg, Novak, above n 7, 227–8; Novak and Gowin, above n 9, 25–34; Fraser, above n 51, 22–4.

[57] See Novak, above n 7, 40.

[58] Jack M Balkin & Sanford Levinson, ‘Getting Serious About “Taking Legal Reasoning Seriously”’ (1999) 74 Chicago-Kent Law Review 543.

[59] See, eg, Richard S Markovits, ‘“You Cannot Be Serious!”: A Reply to Professors Balkin and Levinson’ (1999) 74 Chicago-Kent Law Review 559.

[60] Wetlaufer, above n 11.

[61] Elkins, above n 4, 514.

[62] Novak and Gowin, above n 9, 21.

[63] Balkin, above n 2, 166–9.

[64] Novak, above n 7, 9.

[65] Ibid. He states that ‘[t]o Ausubel, meaningful learning is a process in which new information is related to an existing relevant aspect of an individual’s knowledge structure. However, the learner must choose to do this’: at 51.

[66] Ibid 69–71.

[67] Schau and Mattern, above n 47.

[68] Nickerson, above n 49.

[69] See Schau & Mattern, above n 47, 171.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Ibid. See also above n 58 (discussing Balkin’s involvement in a critical debate about the need to take legal thinking seriously).

[72] Ibid. See also above n 35 and accompanying text (discussing Balkin’s involvement in a critical debate about the need to take legal thinking seriously).

[73] See Novak, above n 7, 19–20 and 61.

[74] Novak and Gowin, above n 9, 20.

[75] Elkins, above n 4, 517.

[76] See Jerome Hausman, ‘Mapping as an Approach to Curriculum Planning’ (1974) 4 Curriculum Theory Network 192, 196.

[77] Balkin, above n 2, 106.

[78] The Zodiac symbol depicted by a water carrier, from the Latin word for ‘water bearer’. See Macquarie Dictionary (4th ed, 2005) 65.

[79] Ibid 167.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LegEdRev/2008/5.html