Melbourne Journal of International Law

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne Journal of International Law |

|

A REQUIEM FOR THE TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP:

SOMETHING NEW, SOMETHING OLD AND SOMETHING BORROWED?

A Requiem for the TPP

RODRIGO POLANCO LAZO[*] AND SEBASTIáN GóMEZ FIEDLER[†]

On 4 February 2016, after almost seven years of negotiations, the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (‘TPP’) was signed by 12 negotiating countries. The TPP was then labelled by all signatory countries as a ‘new’, ‘high standard’, and ‘21st century agreement’. However, the ratification process of the agreement was stalled and most likely in a definitive way, after the United States decided to withdraw from the TPP in January 2017. Before regretting this development, looking back to the halt of the ratification process of the TPP one can ask how much innovation this treaty really had and the usefulness of mourning the failure of having a TPP agreement, either in terms of future usage of TPP text, or in terms of political relevancy. This article aims to describe the level of novelty of the TPP, specifically in comparison with existing trade and investment agreements between TPP signatory countries, notably the United States. For that purpose, we have focused on the core disciplines of the agreement that were highlighted as novelty parts of the TPP, or that generated debate during the negotiation of the treaty. As a benchmark, we have compared the texts of the previous treaties concluded between TPP signatory states, with the TPP chapters on investment, government procurement, regulatory coherence, sustainable development, intellectual property, cross-border trade in services, telecommunications, electronic commerce, competition, and state-owned enterprises, small and medium-sized enterprises (‘SMEs’), transparency and anti-corruption. The article concludes that the TPP was largely ‘Made in America’ — the same country that triggered its demise — as the structure and content of the treaty clearly follow the texts of previous agreements concluded by the United States. However, the influence of other TPP signatories is also perceived in the final text, notably Australia, Canada, Chile and Peru. We also conclude that some parts of the TPP were not particularly novel for signatory countries, as the treaty built on existing trade and investment agreements, offering a consolidation of commitments already present in treaties in force between TPP signatories. However, the TPP also delivered innovation, by including certain disciplines that have not been traditionally established in preferential trade agreements (like regulatory coherence and e-commerce) and others that have benefited from a larger development compared to existing agreements (like intellectual property and sustainable development). Both consolidation and innovation features can be useful for a TPP 11 or for future preferential trade agreements.

CONTENTS

On 5 October 2015, after almost seven years, the 12 countries taking part in the negotiations towards a Trans-Pacific Partnership (‘TPP’) — Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, and Viet Nam — announced an agreement whose final text was signed on 4 February 2016 in Auckland, New Zealand. For years, TPP negotiations were criticised for being kept secret, as, since the beginning of the negotiations, none of its documents were officially released for public review. However, some of them were leaked and made publicly available by organisations like Citizens Trade Campaign[1] and Wikileaks.[2] An official text of the agreement was officially available on 5 November 2015, and a ‘legally verified’ text of the TPP was released on 26 January 2016.[3] However, the ratification process of the agreement was stalled, and most likely in a definitive way, after the US decided to withdraw from the TPP on 23 January 2017.[4]

Of all the TPP signatories, only Japan[5] and New Zealand[6] have ratified the agreement. Since the withdrawal of the US, the rest of the TPP signatories have been analysing how to proceed after this significant drawback. In Viña del Mar, Chile, on 16 March 2017, at the sidelines of a High-Level Dialogue on Integration Initiatives for the Asia-Pacific, government representatives from all TPP partners (except the US) issued a joint statement communicating that they ‘exchanged views on their respective domestic processes regarding TPP and canvassed views on a way forward that would advance economic integration in the Asia Pacific’.[7] The so-called ‘TPP 11’ met again on 20 May 2017 in the margins of an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (‘APEC’) meeting of Ministers responsible for trade to discuss the future of TPP, also releasing a joint statement in which they ‘agreed to launch a process to assess options to bring the comprehensive, high quality agreement into force expeditiously, including how to facilitate membership for the original signatories’.[8] The trade ministers also ‘underlined their vision for the TPP to expand to include other economies that can accept the high standards of the TPP’.[9]

Due to these recent events, the future of TPP still appears uncertain, notwithstanding the withdrawal of the US. One can wonder, what is motivating the TPP 11 countries to try reviving TPP? We believe there are two possible explanations: first and foremost, although it is not a treaty in force, the TPP contains principles, standards and provisions beneficial for its signatories if properly implemented. It can open new markets and sectors that before TPP were unviable for some exporters. The TPP is also a refined agreement, whose negotiations and signing involved significant efforts for all its governments and carefully written by its signatories, after eight years of arduous work. Related to this last point, TPP has become a template for negotiations and in fact, an ambitious one, in topics such as anti-corruption, environment and labour. In the same line, the TPP is still an attempt for its signatories to have trade rules that have been discussed but not agreed at the World Trade Organization, a concept often referred to as ‘regional multilateralism’.[10]

Secondly, by reason of the current juncture that globalisation and global economy are facing, with a revival of protectionism and nationalism regarding trade and investment, it becomes politically relevant for TPP signatories to give a signal that free trade negotiations continue, as well as to show a commitment refraining from protectionist or chauvinist policies. In fact, the TPP 11 countries have been demonstrating that this agreement is more than just a way for the US to grow its influence in the Asia-Pacific region, contesting China’s, as was suggested by many during the first years of TPP negotiations.

The US publicly claimed that the TPP was ‘Made in America’, and that it was designed to ‘level the playing field for American workers & American businesses’.[11] The ambitions of the US were also to provide through the TPP a ‘first mover’ platform in regulatory issues. Then US President Barack Obama even declared:

the TPP means that America will write the rules of the road in the 21st century. When it comes to Asia, one of the world’s fastest growing regions, the rulebook is up for grabs. And if we don’t pass this agreement — if America doesn’t write those rules — then countries like China will.[12]

After the TPP’s demise at the beginning of the Trump administration, the case to move ahead on a TPP 11 has mainly been a political response to the ‘America First’ trade rhetoric, and the intent by the current US government to replace inclusive regional or multilateral agreements with one-on-one negotiations on terms essentially dictated — and not negotiated — by the US.[13]

After a meeting of TPP 11 was in Hakone, Japan, on 14 July 2017, according to the New York Times, Japan’s chief negotiator, Kazuyoshi Umemoto, stated that the group ‘achieved mutual understanding on a path forward’, adding that ‘we need a new international agreement’.[14] His words have to be taken in the context of the ongoing negotiations of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (‘RCEP’), led by China, an allegedly less ambitious deal that involves 16 countries, including some of the TPP 11.

On 11 November 2017, in the margins of an APEC meeting, the TPP 11 countries declared that they have agreed on the core elements of a ‘Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership’ (‘CPTPP’). Ministers agreed to an annex (Annex I) that provides an outline of agreement incorporating provisions of the TPP, and to an annex (Annex II) which lists a set of twenty provisions which will be suspended. A final text of the CPTPP is reportedly in the making.[15]

According to a recent study on the outcomes for the TPP signatories if the agreement goes ahead as negotiated without the US, although the TPP 11 in aggregate is much smaller than the TPP 12, some countries would be better off with the TPP 11, specifically Canada, Chile, Mexico and Peru. The authors state that the TPP 11 is better for these countries as they ‘avoid erosion of existing preferences in the U.S. market ... while they pick up market share in the Western Pacific from the U.S.’.[16] On the other hand, they conclude that countries like Viet Nam and Japan would be worse off because ‘they stood to gain the most in the U.S. market under the TPP 12’.[17] Therefore, we can anticipate a complex scenario for TPP 11 countries in terms of market access negotiations. This complexity adds to the legal issues surrounding the different frameworks to bring the TPP back on track without the US. Also, another challenge is to review those provisions that were pushed by the US and accepted as a trade-off by many TPP signatories because of enhanced market access to the US market. However, it also reveals that a TPP 11 agreement might be highly relevant for the Eastern Pacific countries, especially having in mind the North American Free Trade Agreement (‘NAFTA’) modernisation process officially began in August 2017.

But to ponder how useful it is to mourn the TPP and its political economy, it is maybe necessary to assess how useful this agreement is, either in terms of future usage of TPP text, or in terms of novelty.

The TPP was labelled as a ‘new’,[18] ‘high standard’,[19] ‘21st century’[20] agreement. But just how accurate are these descriptions? This article aims to examine the level of novelty of the TPP, specifically in comparison with existing trade and investment agreements between the 12 countries that were part of its negotiation, notably the US.

For that we need first to provide some historical context. In its origin, the TPP negotiations formally started as an update and enlargement of an agreement the US was not party to: the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement (‘P4’) concluded between Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore in 2005. However, one can say the TPP also existed in the context of several preferential trade agreements (‘PTAs’) and international investment agreements (‘IIAs’) previously concluded between the countries that negotiated the TPP.

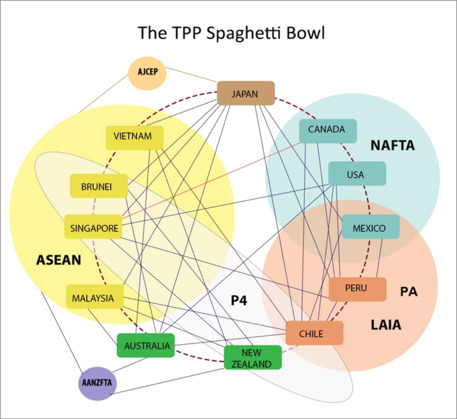

Figure 1: The TPP Spaghetti Bowl[21]

Before establishing the TPP, around 30 bilateral and multilateral PTAs had already been entered into between TPP members, including inter alia the NAFTA, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (‘ASEAN’), the South Pacific Regional Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement (‘SPARTECA’), the Latin American Integration Association (‘LAIA’), the Additional Protocol to the Pacific Alliance Framework Agreement (‘PAAP’) and bilateral free trade agreements (‘FTAs’), such as United States–Australia and Japan–Mexico.[22] A treaty between Canada and Singapore was in negotiation, but it has been on hold by mutual agreement since November 2009.[23]

Chile leads the conclusion of pre-existing trade and investment agreements with other TPP signatories, as it already has PTAs with the other 11 countries that have negotiated the TPP. At the same time, Chile has signed four bilateral investment treaties (‘BITs’) with Australia, Malaysia, Peru and Viet Nam (terminated in 2009 after being replaced with an FTA with the same country).

Therefore, one can rightfully ask how much of the TPP was really ‘new’ and how much was a consolidation of existing rules? Was the US really the driving force behind this agreement? What is the level of contribution of the other signatories to the TPP taking into account their previous agreements?

In quantitative terms, Todd Allee and Andrew Lugg compared the TPP text to the previous 74 PTAs that the TPP members have signed since 1995. In their text analysis, they identified the concordance between the wording in every preferential trade agreement of each TPP signatory since 1995 and the language of the TPP text. The data extracted allowed the authors to assess the level of influence of each TPP signatory in writing the TPP, as well as the preponderance of certain countries’ previous PTAs on each chapter of the agreement. The results showed that the US had the strongest hand in writing the TPP, with nearly 45 per cent of the text of US PTAs signed between 1995–2015 found almost verbatim in the agreement, followed by Australia, Canada and Peru who had averages close to 30 per cent.[24] Regarding specific chapters, the authors concluded that the US had the greatest average of percentage copied from previous PTA chapters in investment (79.9), financial services (67.6), general services (61.6), telecommunications (57.6), safeguards (47.2), intellectual property (44.7), dispute settlement (38.6), technical barriers to trade (35.5), labour (32.2), sanitary and phytosanitary (32) and antidumping (18.7).[25]

But in order to determine the usefulness of TPP for future negotiations of PTAs, such quantitative analysis needs to be complemented by a more in-depth contextual and qualitative account on how some TPP issue areas have benefited from consolidation or have brought novelty, with respect to existing agreements.

To qualitatively assess the novelty of the TPP in the background of agreements previously concluded by its signatories, we have focused on certain issues that have been flagged as innovative or controversial during TPP negotiations, such as investment, government procurement, regulatory coherence, sustainable development, intellectual property, trade in services, telecommunications, electronic commerce, competition, state owned enterprises, SMEs, transparency and anti-corruption. It is important to note that all these issues have not developed the same way in previous PTAs; therefore, the length and breadth of the discussion that take place in the following sections vary considerably.

The negotiations of an investment chapter in TPP took place in a background where several IIAs had already been concluded between TPP signatories, including BITs and treaties with investment provisions (‘TIPs’). All of these countries have concluded more than one IIA with other TPP signatories. According to the information provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (‘UNCTAD’), there are 53 IIAs concluded between TPP signatories, considering 16 BITs and 37 TIPs that also include investment chapters of PTAs.[26]

|

BITs

|

Date of Signature

|

|

|

1

|

12 November 2009

|

|

|

2

|

22 November 2008

|

|

|

3

|

14 November 2006

|

|

|

4

|

23 August 2005

|

|

|

5

|

14 November 2003

|

|

|

6

|

27 February 2003

|

|

|

7

|

2 February 2000

|

|

|

8

|

16 September 1999

|

|

|

9

|

22 July 1999

|

|

|

10

|

09 July 1996

|

|

|

11

|

07 December 1995

|

|

|

12

|

13 October 1995

|

|

|

13

|

11 November 1992

|

|

|

14

|

29 October 1992

|

|

|

15

|

21 January 1992

|

|

|

16

|

5 March 1991

|

|

|

Treaties with Investment Provisions

|

Date of Signature

|

|

|

1

|

8 July 2014

|

|

|

2

|

Additional Protocol to the Framework Agreement of the

Pacific Alliance (Chile, Colombia, Peru, Mexico)

|

10 February 2014

|

|

3

|

22 May 2012

|

|

|

4

|

12 November 2011

|

|

|

5

|

31 May 2011

|

|

|

6

|

06 April 2011

|

|

|

7

|

16 February 2011

|

|

|

8

|

13 November 2010

|

|

|

9

|

26 October 2009

|

|

|

10

|

ASEAN

Investment Agreement (Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Singapore and Viet

Nam)

|

26 February 2009

|

|

11

|

ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade

Agreement (‘AANZFTA’)

(ASEAN, Australia and New Zealand)

|

27 February 2009

|

|

12

|

25 December 2008

|

|

|

13

|

30 July 2008

|

|

|

14

|

29 May 2008

|

|

|

15

|

29 May 2008

|

|

|

16

|

14 April 2008

|

|

|

17

|

18 June 2007

|

|

|

18

|

27 March 2007

|

|

|

19

|

22 August 2006

|

|

|

20

|

12 April 2006

|

|

|

21

|

13 December 2005

|

|

|

22

|

P4

Agreement (Brunei Darussalam, Chile, New Zealand, Singapore)

|

3 June 2005

|

|

23

|

17 September 2004

|

|

|

24

|

18 May 2004

|

|

|

25

|

6 June 2003

|

|

|

26

|

6 May 2003

|

|

|

27

|

17 February 2003

|

|

|

28

|

13 January 2002

|

|

|

29

|

14 November 2000

|

|

|

30

|

13 July 2000

|

|

|

31

|

17 April 1998

|

|

|

32

|

5 December1996

|

|

|

33

|

15 December 1995

|

|

|

34

|

NAFTA

(Canada, Mexico, United States of America)

|

17 December 1992

|

|

35

|

Organisation of the Islamic Conference Investment

Agreement

(Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia)

|

5 June 1981

|

|

36

|

LAIA

Treaty (Chile, Mexico, Peru)

|

12 August 1980

|

|

37

|

SPARTECA

(Australia, New Zealand)

|

14 July 1980

|

As said by its negotiators, the TPP investment chapter aimed to improve the current standards of protection for foreign investors, ‘striking an interesting balance between the protection of foreign investments and the sovereign right of states to regulate their interests in pursuit of legitimate public policy objectives’.[27]

However, a detailed analysis of the TPP investment chapter shows that the agreement was not so innovative in ‘improving’ standards of investment protection. Tomer Broude et al have concluded that the TPP investment chapter builds significantly on existing agreements, being very close to NAFTA.[28] Wolfgang Alschner and Dmitriy Skougarevskiy have found that this part of the agreement offers ‘more of the same’ with few truly novel features and 81 per cent of its main text coming from the 2006 US–Colombia FTA.[29] Already Mélida Hodgson had drawn a similar conclusion, after comparing a leaked version of the chapter with the 2012 US Model BIT, finding almost complete similarity on issues such as expropriation, customary international law, regulatory space, as well as in limitations related to balance of payments and public debt.[30] In the same line, José Álvarez has concluded that the TPP investment chapter’s structure and essential content follows the general outline of the US–Argentina BIT (1991)[31] and Bernasconi Osterwalder, who determined that the text mirrors most of the 2004 US Model BIT, falling short of its supposedly progressive goals.[32] Luke Nottage also concludes that TPP’s investment chapter largely follows US past treaty practice.[33]

But to know how similar the TPP is to other previous investment agreements only tells you part of the story. Probably what matters the most are differences.[34] So, even though the TPP investment chapter in practice works more as a consolidation of the level of protection of foreign investment already existing in IIAs concluded by TPP signatories, certain features can be considered innovative on both substantive protection and procedural issues. This requires a more qualitative analysis that we try to undertake in the following sections.

The elucidation of the concepts of ‘investment’ and ‘investor’ is found in footnotes of the TPP investment chapter, which limits its scope of application. With respect to the definition of investment, certain exclusions are considered in the definitions of ‘branch’,[35] ‘loan’,[36] and ‘investment authorization’.[37] Regarding the definition of investor, of particular significance is a footnote that could limit pre-establishment protection,[38] through the clarification of what the parties understand when an investor ‘attempts to make’ an investment, meaning that when that investor ‘has taken concrete action or actions to make an investment, such as channelling resources or capital in order to set up a business, or applying for permits or licenses’.[39] But this is not novel for the Latin American countries that are signatories of the TPP (Chile, Mexico and Peru) as these limitations on pre-establishment were already considered with almost the same wording (although in Spanish) on the investment chapters of FTAs concluded between them, like in Chile–Peru FTA (2006), Mexico–Peru FTA (2012), and the Additional Protocol to the Framework Agreement of the Pacific Alliance (2014).[40]

Another novel addition is the clarification of the notion of ‘like circumstances’ in national treatment and most favoured nation (‘MFN’), according to which the analysis of these relative standards depends ‘on the totality of the circumstances, including whether the relevant treatment distinguishes between investors or investments on the basis of legitimate public welfare objectives’.[41] This is further clarified in more detail on a Drafters’ Note, with the intention of ensuring that tribunals will follow the approach set out by the parties that comparisons are made only with respect to investors or investments on the basis of relevant characteristics.[42]

As mentioned, another important substantive novelty is the inclusion of a corporate social responsibility (‘CSR’) clause,[43] a provision that is not part of the US ‘template’ for investment treaties. This type of clause has been typically found in Canadian FTAs, like those concluded with Colombia, Panama and Peru.[44]

On procedural issues, the architecture of the section on investor–state arbitration is similar to the NAFTA ch 11 structure, detailing the procedure from the arbitration’s commencement to its end.[45] Yet, some innovations can be detected from that model.

First, the TPP foresees the adoption by the parties of a code of conduct for arbitrators and of guidelines on conflicts of interest, based on the Code of Conduct for Dispute Settlement Proceedings under ch 28 (Dispute Settlement) and other relevant rules or guidelines on conflicts of interest in international arbitration.[46]

Secondly, it is explicitly stated that investors bear the burden of proving all elements of their claims, keeping consistency with the general principles of international law that are applicable to international arbitration (art 9.23.7).

Thirdly, the TPP seems to expand the scope of dispute settlement that is traditionally found in United States agreements. The general practice was to limit ISDS to the core substantive standards, but now other provisions also appear to be subject to dispute settlement, like Non-Conforming Measures (art 9.12), Subrogation (art 9.13), Special Formalities and Information Requirements (art 9.14), Denial of Benefits (art 9.15), Investment and Environmental Health and other Regulatory Objectives (art 9.16) and even the above-mentioned CSR provision (art 9.17).[47]

Some procedural innovations come from the change of recent practice of some TPP signatories. This is the case of Australia, which before the TPP did not consider investor–state arbitration in its Economic Partnership with Japan (2014), in the FTA with United States (2004), and in the Investment Protocol with New Zealand (2011) established under the Australia–New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (‘ANCERTA’). By virtue of a side letter, the exclusion of investor–state arbitration will only remain with respect to New Zealand, in order to keep consistency with the ANCERTA.[48] However, no proposal for a similar side letter between Australia and the US (or any other treaty partners) was formally tabled in relation to the TPP.[49]

A certain influence of Australian policy has also left its mark in the text of the TPP, as tobacco control measures are carved out from ISDS in its exception chapter (art 29.5),[50] probably in the effort to address the challenges raised by Philip Morris Asia Ltd v Australia with respect to plain packaging policies.[51]

In sum, although the TPP investment chapter is a consolidation of the level of protection of investment already considered in IIAs concluded by TPP countries, there are few important substantive and procedural innovations that could inform future negotiations of investment agreements. On substantive protection, the TPP includes important clarifications on the notions of ‘investor’ and ‘investment’, national treatment and MFN, and the inclusion of novel provisions on CSR. On procedural issues, although the chapter follows the NAFTA structure, certain innovative features are found in ISDS, such as the inclusion of a code of conduct for arbitrators, and provisions on the burden of proof and the overall scope of ISDS.

With the exception of Malaysia, all TPP signatories had concluded a prior PTA with another TPP country, including a special chapter on public procurement. Nowadays, there are 21 PTAs between TPP countries with a special chapter on government procurement.

|

Agreements with a Government Procurement

Chapter

|

Entry into Force

|

|

Australia–Japan FTA

|

15 January 2015

|

|

Pacific

Alliance Additional Protocol (Chile, Colombia, Peru, Mexico)

|

10 February 2014

|

|

Peru–Japan FTA

|

1 March 2012

|

|

ASEAN–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade

Agreement (‘AANZFTA’) (including Viet Nam)

|

1 January 2010

|

|

Canada–Peru FTA

|

1 August 2009

|

|

Peru–Singapore FTA

|

29 May 2009

|

|

Australia–Chile FTA

|

6 March 2009

|

|

US–Peru TPA

|

1 February 2009

|

|

Chile–Japan SEP

|

3 September 2007

|

|

TransPacific Free Trade Agreement (P4: Chile, New

Zealand, Singapore and Brunei Darussalam)

|

8 November 2006

|

|

Mexico–Japan EPA

|

1 April 2005

|

|

US–Australia FTA

|

1 January 2005

|

|

US–Chile FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

US–Singapore FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

Australia–Singapore FTA

|

28 July 2003

|

|

Singapore–Japan EPA

|

30 November 2002

|

|

New Zealand–Singapore CEP

|

1 January 2001

|

|

Mexico–Chile FTA

|

31 July 1999

|

|

Canada–Chile FTA

|

5 July 1997

|

|

NAFTA (Canada, Mexico and the United States of

America)

|

1 January 1994

|

|

Agreements with a Government Procurement Side

Agreement

|

Entry into Force

|

|

Australia–New Zealand Closer Economic Relations

Trade Agreement

|

1 September 2007

|

As we can see, the majority of TPP signatories have already opened public procurement under earlier PTAs, and these commitments are complemented with those undertaken by the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement (‘GPA’) — to which Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore and the US are parties. It is in this context that the level of novelty of TPP on government procurement should be assessed for its contracting parties, both procedurally and in its coverage.

A detailed procedural analysis of this part of the agreement finds that the TPP procurement chapter virtually copied the provisions of the GPA with minor modifications. This explains that the coverage considered in the chapter generally emulated the solutions presented in the GPA model, with lists of covered procurement, goods and services, as well as value thresholds and country specific commitments.[52]

On coverage, TPP countries basically restated or modestly improved the procurement that had opened under the earlier agreements.

In the case of the GPA parties, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore and the US basically granted its GPA coverage, with certain variations.

For Canada, TPP would have opened markets for bidders coming from Australia, Brunei, Malaysia and Viet Nam,[53] expanding commitments granted under the GPA and NAFTA, augmenting the list of covered federal entities from 78 to 95 entities, and adding 12 entities to the list of ‘Other Entities’ under coverage.[54]

Japan effectively would have opened a new procurement market for Malaysia. In the case of the Economic Partnership Agreement (‘EPA’) between Japan and Viet Nam (2009) and the EPA Japan–Brunei (2008), although there is not a separate chapter devoted to this discipline, one provision states that both parties shall endeavour to accord MFN treatment and ensure fairness, efficiency and transparency in government procurement,[55] allowing these countries to import the treatment given to third countries with respect to public procurement. In TPP, Japan largely followed its GPA coverage but adds one city (Kumamoto-shi) and 12 ‘Other Entities’, primarily railway companies, and others that are not found in the GPA (JKA, Management Organization for Postal Savings and Postal Life Insurance, and the Open University of Japan Foundation).[56]

New Zealand would have opened new markets for Malaysia, Mexico and Peru, granting the GPA coverage, with the exception of sub-central entities. However, its TPP coverage included less ‘Other Entities’ than in the GPA (10 instead 19 entities in the GPA)[57] and withholding all those entities from Mexico.[58]

Singapore would have opened new markets for Mexico, Malaysia and Viet Nam. Regarding coverage, it followed its GPA commitments, adding 10 new authorities, boards, councils and the Civil Service University (‘CSU’), but excluding two universities (Nanyang Technological University and National University of Singapore) that are listed in the GPA. The coverage of services was basically the same as in the GPA, with the addition of one: the placement services of office support personnel and other workers.[59]

For the US, the TPP included all entities of the central level of government listed in the GPA Schedule, including a new one (the Denali Commission),[60] with no sub-central government entities. This made the TPP the broadest entity coverage by the US to date.[61] The TPP effectively would have opened new markets for Brunei, Malaysia and Viet Nam. However, the US also imposed limitations on Malaysia (procurement for the generation or distribution of electricity, including the commitment with respect to financing provided by the Rural Utilities Service of power generation projects) and Viet Nam (access to Department of Defence procurement to two entities: Education Activity and the Defence Commissary Agency).

In the case of Australia, the TPP would have opened new markets for Brunei, Malaysia, Mexico and Peru. However, coverage to sub-central government entities was only granted with respect to bidders from Canada, Chile, Japan, Mexico and Peru.[62] The major impact of the TPP on Australian central procurement entities would have been the requirement that complaints regarding the procurement process are not handled internally (as established in existing Commonwealth Procurement Rules), but by an impartial administrative or judicial authority that is independent of the procurement entity.[63]

Brunei Darussalam would have opened new markets for all TPP signatories, with the exception of Chile, New Zealand and Singapore, already parties with that country in the P4 Agreement. It is noteworthy to highlight that in the TPP Brunei only included central government entities as it does not have any sub-central government entities.[64]

Chile would have opened new procurement markets for Malaysia and Viet Nam, largely following its commitments included in its FTA with the US, although it lists three new ministries in the TPP, which are not in that agreement (Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Sports and the National Council for Culture and the Arts), because they did not exist at the time of signature of that PTA. Chile also added two exclusions: preferences to benefit micro and small and medium-sized enterprises.[65]

Malaysia is the only TPP signatory that did not have previous procurement commitments with any of the other negotiating countries. Probably for that reason, it was able to secure an extended transition period for decreasing contract value thresholds up to 21 years.[66]

Mexico would have basically incorporated its NAFTA coverage into the TPP,[67] including only Central Government Entities, and opening its procurement market for Australia, Brunei, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Viet Nam.

Peru would have opened its procurement market for the first time to the majority of the TPP signatories, with the exception of Canada, Chile, Mexico, Singapore and the US, with whom it had previous agreements. In fact, the TPP would not have meant a major improvement for Peru, as, for example, it covered less central government entities in the TPP than in its FTA with the US (a total of 32 in the TPP instead of 67 in the Peru–US FTA), notably 31 universities listed in that PTA. Regarding its coverage, Peru would have expanded it to three services that were excluded under the FTA with the US (architectural services; engineering and design services; and engineering services during construction and installation phase).[68]

The TPP could have been the second time that Viet Nam opened the procurement market in a PTA, becoming a novelty for almost all its signatories (except for Australia and New Zealand that benefit from the prior FTA with ASEAN). Like Malaysia, Viet Nam was able to secure a long transition period of decreasing contract value thresholds up to 26 years.[69]

In conclusion, the TPP chapter on government procurement largely replicated the GPA on this discipline — even for non-GPA parties, with a modest improvement in existing coverage under prior agreements. For Jędrzej Górski, major deficiencies of the TPP procurement chapter’s coverage are the refusal to cover sub-central procurement in Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, the US and Viet Nam, the exclusion of utilities services in the case of Canada, Mexico, and Viet Nam as well as a long transition period for thresholds in the case of Malaysia and Viet Nam.[70]

One part of the TPP that differed from what can be found in previous PTAs is the inclusion of a new discipline in the chapter on regulatory coherence (ch 25). In fact, the TPP was the first PTA with a dedicated chapter on this discipline that was negotiated, although in the end both the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (‘CETA’) and the Pacific Alliance Additional Protocol (‘PAAP’), were concluded before the TPP, also including a chapter on this discipline but with a different nomenclature (‘regulatory cooperation’ in the case of CETA, and ‘regulatory improvement’ for the PAAP).

The stated regulatory convergence goals of the TPP were crucial in its signatories deciding to take a bolder step to eliminate unnecessary regulatory barriers, creating a novel regulatory coherence chapter with the aim to make the regulatory systems of member countries more compatible and transparent.[71] The TPP included mechanisms to achieve greater domestic coordination of regulations, increase transparency and stakeholder engagement, and improve competitiveness and the ability of SMEs to engage in international trade.[72]

The main objective of regulatory coherence is the harmonisation or, alternatively, the mutual recognition of regulatory measures that exert a major influence on international trade.[73] The TPP took a broader scope in this regard, including rules on transparency (public notice and prior consultation for new regulations); the elimination of duplicative and overlapping regulations; rules against anticompetitive practices, particularly for government monopolies and state owned enterprises; greater use of mutual recognition agreements for services and health and safety regulation; and clear lines of administrative and judicial appeal.[74] However, there appears to be a predominant emphasis on convergence in procedural requirements rather than on convergence on the substantive content of the regulations.

TPP ch 25 started with general provisions recalling the importance of regulation and regulatory processes. Articles 25.1 and 25.3 of the chapter confirmed that the obligation of regulatory coherence is limited to certain regulatory measures (‘covered regulatory measures’) as defined by each country. For those purposes, each party should have promptly, and no later than one year after the date of entry into force of the TPP, determined and made publicly available the scope of its covered regulatory measures, aiming to achieve a ‘significant coverage’.

In order to achieve regulatory coherence, TPP signatories committed to centralised or coordinated process in the elaboration of regulations. The treaty did not impose one specific formula in this regard, allowing countries to choose between establishing mechanisms, processes or a central body for coordination at the national or central level, including effective inter-agency consultation coordination among regulators, opportunities for stakeholder input, and fact-based regulatory decisions. However, certain minimum elements were established for such coordination procedures, like to strengthen coordination and consultation between government agencies, promote regulatory improvement and public information on measures reviewed.

The TPP also envisaged other internal and external mechanisms of regulatory coherence. Internal mechanisms included the encouragement of core good regulatory practices, like regulatory impact assessments (‘RIAs’)[75] and provisions on transparency and public information.[76] External mechanisms included points of contact to provide information at the request of another party, and a Committee on Regulatory Coherence, consisting of representatives from parties’ governments to assess the implementation of the chapter and regulatory cooperation activities, including exchange of information with TPP signatories, dialogues with ‘interested persons’ — including SMEs and civil society — and training and cooperation between regulatory authorities of other parties.[77]

The TPP chapter on regulatory coherence should be read together with numerous transparency articles existing in other chapters of the agreement (briefly examined in the different sections of this article), and most importantly in ch 26 s B on transparency, which included provisions on public transparency, communications around regulations and public notice of government measures (including opportunities for stakeholder comment on measures before they are adopted and finalised), review and appeal, which are also present in PTAs previously concluded by TPP signatories, notably by the US.

The PAAP’s new chapter on regulatory improvement (included as an amendment to the PAAP signed on 3 July 2015)[78] seemed to have influenced the final contours of the TPP text on regulatory coherence. Almost six months before the closing of the TPP text, the PAAP considered very similar provisions to the ones found in the TPP; probably due to the fact that three of its members were at the same time negotiating the TPP (Chile, Mexico and Peru). For example, the definition of regulatory improvement in the PAAP (art 15bis 2.1) and regulatory coherence in the TPP (art 25.2.1) is basically the same, with one telling difference: while the TPP refers to the use of ‘good regulatory practices’, for the Additional Protocol, regulatory improvement refers to the use of ‘good international regulatory practices’, almost unconsciously acknowledging that practices should come from elsewhere and not arise from the Alliance’s member countries. The PAAP also includes a chapter on transparency which, as with TPP ch 26, includes commitments on points of contacts to facilitate communication between the parties, publication of laws and regulations and advanced publication of proposed laws and regulations, with detailed commitments on provision of information, administrative proceedings, review and appeal.[79]

Although the TPP delivered a new take in the novel discipline of regulatory coherence, it also did it with shortcomings. Limitations on the scope of the regulatory coherence could have undermined the basic goals of the chapter, as cross-country differences in the agreed scope of ‘covered measures’ could lead to great divergence, as several measures were excluded from the Regulatory Coherence Chapter. Similarly, if commitments were not implemented in the same way across TPP member states, this could foster further regulatory divergence within the regional compact.

Besides, in the case of conflict with other chapters of the TPP, those chapters would have taken precedence over the chapter on regulatory coherence, de facto excluding them from the obligations under the Regulatory Coherence Chapter. In the same line, divergences arising on the implementation of the regulatory coherence commitments were excluded from the TPP interstate dispute settlement system.

As a ‘21st century’ agreement,[80] the TPP claimed to adequately deal with the relationship between trade, investment and the environment. Chapter 20 ‘Environment’, composed of 23 articles, addressed issues like trade and biodiversity, environmental protection, multilateral environmental agreements (‘MEAs’), CSR, climate change and sustainable development, among others. As stated by Errol Meidinger, the TPP Environment Chapter offered some ‘environmental benefits by: (1) directly linking trade to numerous environmental concerns, thereby injecting environmental considerations into trade policy; (2) committing member countries to enact, upgrade, and enforce environmental laws; (3) providing dispute settlement mechanisms for situations where countries may not do so; and (4) creating linkages to environmental governance initiatives of non-state actors’.[81]

Including environmental commitments in PTAs is not something new for TPP signatories. Currently, there are 19 PTAs between TPP countries covering environmental issues. Four of them contain a special chapter on environment, all of them with the US as one of the parties. The most recent agreement with a special chapter on environment is the 2009 US–Peru Trade Promotion Agreement (‘TPA’). Regarding PTAs with a side agreement on environment, there are four as well, as seen in the table below. The most recent PTA with a side agreement is the New Zealand–Malaysia FTA (2010). The rest of the PTAs between TPP signatories only include cooperation provisions, best endeavour provisions, side letters and joint statements. Only Brunei, Japan and Viet Nam did not have PTA environmental provisions with TPP signatories.

|

PTAs with environment as chapter or side

agreement

|

Entry into Force

|

Mode of inclusion

|

|

US–Peru TPA

|

1 February 2009

|

Special chapter

|

|

US–Australia FTA

|

1 January 2005

|

Special chapter

|

|

US–Singapore FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

Special chapter

|

|

US–Chile FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

Special chapter

|

|

New Zealand–Malaysia FTA

|

1 August 2010

|

Side agreement

|

|

Canada–Peru FTA

|

1 August 2009

|

Side agreement

|

|

Canada–Chile FTA

|

5 July 1997

|

Side agreement

|

|

NAFTA (Canada, Mexico and the United States of

America)

|

1 January 1994

|

Side agreement

|

The TPP’s Environment Chapter had a mixed reception among the environmental community. While the Sierra Club considered that the agreement fails to protect our environment and threatens our air, water, and climate,[82] the World Wildlife Fund welcomed the environment chapter pointing out that no major trade agreement before the TPP has gone so far to address growing pressures on natural resources.[83]

TPP ch 20 began defining environmental law as a statute or regulation of a party, or provision thereof, including any that implements the party’s obligations under a multilateral environmental agreement, the primary purpose of which is the protection of the environment, or the prevention of a danger to human life or health, through (a) the prevention, abatement or control of: the release, discharge or emission of pollutants or environmental contaminants; (b) the control of environmentally hazardous or toxic chemicals, substances, materials or wastes, and the dissemination of information related thereto; or (c) the protection or conservation of wild flora or fauna, including endangered species, their habitat, and specially protected natural areas.[84]

Although it seems to be a broad and encompassing definition, some scholars pointed out the absence of important topics, like the ‘sensible management of existing natural resources and aboriginal management of resources, including traditional knowledge, culture and genetic resources’.[85]

Notwithstanding the conspicuous fact that the agreement does not mention ‘climate change’, the TPP did acknowledge that a ‘transition to a low emissions economy should reflect domestic circumstances and capabilities’ and that parties shall cooperate to address matters of joint or common interest.[86] Article 20.15 mentioned areas of cooperation like energy efficiency; development of cost effective, low emissions technologies and alternative, clean and renewable energy sources; sustainable transport and sustainable urban infrastructure development; addressing deforestation and forest degradation; emissions monitoring; market and non-market mechanisms; low emissions, resilient development and sharing of information and experiences in addressing this issue.

Compared to other PTAs between TPP signatories, the agreement was more ambitious in terms of goals of its environment chapter. The TPP highlighted as objectives the ‘effective enforcement of environmental laws’ to ‘enhance the capacities of the Parties to address trade-related environmental issues’,[87] and added in art 20.2.3 that ‘it is inappropriate to establish or use their environmental laws or other measures in a manner which would constitute a disguised restriction on trade or investment between the Parties’. Although this could be interpreted as economic growth cannot be hampered by environmental protection,[88] because the wording resembles the chapeau of art XX of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (‘GATT’), it could be said that the main aim of art 20.3 was to achieve a balance between trade, investment and environmental protection.

With respect to the levels of environmental protection, the TPP recognised the right of its parties to set their own levels of protection and to enact or amend their environmental legislation.[89] This wording is similar to the one found in the latest PTA signed by the US with another TPP party, the US–Peru TPA (2009),[90] but the TPP simplifies the language, and merely considers the issue as part of the ‘General Commitments’.

The TPP, as with the US–Peru TPA, seemed to follow the European Union sectoral approach to environmental commitments.[91] This is evidenced in the reiteration of several international commitments found in MEAs from which TPP countries are signatories: the Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (‘CITES’) and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (‘MARPOL’). However, the chapter did not have an explicit list of ‘covered agreements’ as the US–Peru TPA did,[92] presumably ‘because several MEAs are not common to the TPP signatories’.[93]

Yet, quite remarkably, the TPP had binding obligations regarding CITES, as it mandated each party to ‘adopt, maintain and implement laws, regulations and any other measures to fulfil its obligations’[94] under the cited MEA. As stated by Jeffrey Schott and Julia Muir, the illegal trade in wildlife generates roughly US$10 to US$20 billion in revenue annually, thus requiring TPP members to bring their regulations and laws into compliance with CITES ‘is a feasible and desirable objective’.[95] According to the CITES website, all TPP signatories are considered to be in category 1 (requirements fully met),[96] although it must be noted that the TPP was not conceived as a self-executing international agreement.

The TPP also had ‘broad commitments to combat wildlife trafficking beyond CITES’,[97] by limiting subsidies on marine fishing, and also recognised the importance of an unsustainable exploitation of fish stocks,[98] while addressing illegal and unregulated fishing.[99] For some, the TPP took a significant step towards implementing binding subsidies disciplines in relation to overfished stocks, whereas WTO members had previously been unable to agree on them, drawing on the expertise of relevant international bodies and regimes, such as the Food and Agriculture Organisation and United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS’), promoting information sharing and learning and a role for a wider group of interested parties.[100] Yet, for others, these advancements were not enough, as it only prohibited or restrained those that affect ‘overfished’ stocks (art 20.16.5), diminishing the potential of the TPP on disciplining marine fisheries subsidies, as it did not cover those targeting stocks which were not overfished.[101]

According to the TPP, signatories had to promote public awareness of its environmental laws and policies,[102] including also procedures for compliance and enforcement, empowering civil society and other stakeholders to denounce violations of environmental law. The TPP also innovated by limiting the investigation of alleged violations of environmental law to established or residing persons in the territory of the TPP party suspected of a violation, as opposed to the US–Peru TPA which allows any interested person to request an investigation.[103]

Chapter 20 refined what was done in previous PTAs between TPP countries relating to public participation. In addition to establishing a procedure for public submissions denouncing a violation of environmental law, the TPP mandated parties to ‘make its procedures for the receipt and consideration of written submissions readily accessible and publicly available’, suggesting those procedures to be posted on ‘an appropriate public website’.[104] Also, the TPP innovated by mandating its parties to elaborate a written report on the implementation ‘no later than three years after the ... entry into force of the Agreement’.[105]

Cooperation, promotion and encouragement of environmental laws and regulations were extensively found in ch 20, specifically on topics such as CSR, biological biodiversity and invasive alien species. The TPP dealt with CSR,[106] requiring its parties to encourage enterprises to voluntarily adopt principles of CSR. It also mandated parties to ‘promote and encourage the conservation and sustainable use of biological biodiversity’.[107] Additionally, the TPP directed its Environment Committee ‘to identify cooperative opportunities to share information and management experiences’[108] on invasive alien species.

Furthermore, the TPP contained a best endeavour provision to address any ‘potential non-tariff barriers’[109] on environmental goods and services and to consider any issues that can be raised on this aspect by any TPP party.[110] However, the agreement missed the opportunity to do more in liberalising trade in environmental goods and services, by lowering existing tariff and non-tariff barriers affecting them. As stated by Gary Hufbauer, Jeffrey Schott and Woan Wong (2010), eliminating tariffs in environmental goods would cause global trade gains of around US$5.9 billion in exports.[111] Additionally, lowering trade barriers to environmental goods allows developing countries to improve their access to environmentally protective technologies. In this regard, TPP art 20.19.3 only mandated the Committee on Environment to address this issue, leaving for future negotiations among TPP signatories any relevant progress on environmental goods and services liberalisation.[112]

Dispute settlement procedures and enforcing mechanisms were applicable to the TPP Environment Chapter. Following consultations (environment, senior representative and ministerial consultations)[113] it allowed for interstate dispute resolution through the request of a panel.[114] The panel should consider requests from non-governmental entities located in the territory of a disputing party, to provide written statements that may assist the panel in evaluating the submissions and arguments of the disputing parties.[115]

The framework of environmental disputes closely followed the model of the US–Peru TPA. The TPP refined such dispute settlement procedure, including the role of experts in a dispute and by allowing parties to seek advice or assistance from an entity authorised by CITES when the disagreement is about conservation and trade (art 20.23.2). Yet, some commentators raised concerns about the possible impact of the TPP on the evolution of international environmental law, as some panellists may not be experts in interpreting MEAs.[116]

Although it was undoubtedly an achievement to have an environmental chapter subject to dispute settlement in an agreement signed between 12 countries, the TPP did not innovate substantially with respect to enforcement provisions. For some, the TPP failed to provide an effective enforcement mechanism, as the panel report would be ‘merely recommendatory in value’.[117] Others found disturbing that the agreement provides for no independent oversight or enforcement mechanisms.[118] The TPP only covered the enforcement of environmental laws affecting ‘trade or investment’ between the parties,[119] following the trend of the other PTAs between TPP countries with a limited scope of the enforcing mechanism for environmental issues. Certain NGOs recalled that past US PTAs ‘have contained similar enforcement provisions for the environmental chapter, no party has ever brought a formal case based on the environmental provisions’.[120] Generally, the Environment Chapter of the TPP innovated in some aspects with respect to prior agreements concluded by TPP signatories, but fell short on others. The TPP innovated on CSR, by encouraging enterprises to adopt values linked to the environment voluntarily.[121] Also, the TPP included provisions on trade and biodiversity, encouraging and promoting a sustainable use of biological diversity.[122] Although violations of the environment chapter could trigger dispute settlement procedures, the TPP could have gone further on enforcement mechanisms, as well as binding obligations regarding MEAs, expanding restrictions on fisheries subsidies to all stocks of fish, and providing a broader scope to the notion of ‘environmental’. A possible explanation for this mixed approach would be the different environmental commitments contained in laws, treaties and regulations of TPP signatories.

The TPP Labour Chapter (ch 19) must be examined as part of a larger trend, having in mind that agreements with provisions on labour issues have been gradually included in PTAs, especially during the last decade, not only in North–South agreements but also in South–South treaties.[123] But such generalisations need to be approached with care, as there is no uniformity of approach in terms of whether to include labour clauses into PTAs, or the content of these clauses.[124] Yet, the TPP labour chapter is among the most innovative ones of the agreement for the breadth of its commitments and its enforcement mechanism.

Some authors considered the TPP to be a ‘game changer’ (especially for Asian TPP countries) and part of a ‘“new generation” of social dimension labour provisions of FTAs’.[125] Chapter 19 recognised International Labour Organization (‘ILO’) fundamental rights, notably with regard to child labour, the right to collective bargaining, forced labour, freedom of association and employment discrimination. Moreover, it had commitments on laws governing minimum wages, hours of work, and occupational safety and health,[126] and included measures to prevent the degradation of labour protections in export processing zones.[127] The TPP also established specific institutional mechanisms to assist in its implementation (a labour council of senior governmental representatives).[128]

Including a labour chapter in a PTA was a novelty for many TPP countries, as their preferred approach had been to cover labour in a side agreement (five agreements), or less binding documents, like side letters or memoranda of understanding. Only four previous PTAs between TPP signatories dealt with labour in a special chapter (all of them with the United States as a party). Thus, it is not strange that Allee and Lugg, have concluded that the US is the prominent country in terms of the source of texts for the TPP in this topic, with 32.2 per cent of the TPP Labour Chapter text taken from previous PTAs with that country.[129]

|

Special chapter on labour

|

Entry into force

|

|

US–Peru TPA

|

1 February 2009

|

|

US–Australia FTA

|

1 January 2005

|

|

US–Chile FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

US–Singapore FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

Side agreement

|

|

|

Canada–Chile FTA

|

5 July 1997

|

|

Peru–Canada FTA

|

1 August 2009

|

|

Chile–Peru FTA

|

1 March 2009

|

|

Malaysia–New Zealand FTA

|

1 August 2010

|

|

NAFTA (Canada, Mexico and the United States of

America)

|

1 January 1994

|

|

Side letter

|

|

|

Australia–Malaysia FTA

|

1 January 2013

|

|

Memorandum of understanding

|

|

|

P4 (Chile, New Zealand, Singapore and Brunei

Darussalam)

|

8 November 2006

|

The TPP Labour Chapter was complemented with side agreements that the US signed with Brunei, Malaysia and Viet Nam (countries with poor levels of ratification of the ILO’s fundamental conventions).[130] These agreements stipulated that labour laws ‘must be newly established, changed and improved to allow independent labour unions, strikes, proper treatment of immigrants, anti-discrimination provisions, labour inspections and other basic labour standards’.[131] Moreover, Brunei, Malaysia and Viet Nam had to implement their respective side agreements ‘before they are allowed to export duty free goods to the US and otherwise use the provisions of the TPP’.[132]

Although cooperation and consultation were strongly encouraged, the commitments in the TPP Labour Chapter were enforceable through dispute settlement procedures, stipulating the public availability of the final report. The provisions on dispute settlement also contemplated labour dialogues, cooperation mechanisms and allowing stakeholders and civil society to participate.[133] As opposed to the Environment Chapter, labour provisions had an effective enforcement mechanism because trade sanctions are permitted. More specifically, ch 19 allowed trade sanctions if a TPP member failed to comply with its obligations,[134] as it contemplates full recourse to all the provisions of the Dispute Settlement Chapter after the establishment of a panel.[135]

Nonetheless, the requirement to adopt regulations and practices governing acceptable conditions of work with respect to minimum wages, hours of work and occupational safety and health were ‘softer’ obligations, as they are determined by each party.[136] Violation of this obligation and of that imposed by art 19.3.1 in relation to the 1998 ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work only occurred when a party ‘has failed to adopt or maintain a statute, regulation or practice in a manner affecting trade or investment between the Parties’.[137]

In sum, the TPP Labour Chapter included enforceable obligations on issues like child and forced labour, the right to collective bargaining and freedom of association. The TPP’s three labour side agreements with Brunei, Malaysia and Viet Nam, aimed to improve workers’ conditions in developing countries with a large labour-intensive industry, showing efforts which are certainly welcomed. The dispute settlement provisions were overall clear and went further than any US-negotiated trade agreement including labour provisions.

TPP treatment of intellectual property is informed by existing multilateral agreements on the issue (particularly the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights — ‘TRIPS’), and the large number of PTAs concluded between TPP signatories.

Currently, there are 25 agreements between TPP countries dealing with intellectual property in a special chapter, notably concluded by the US and Australia:

|

Agreements with an Intellectual Property

Chapter

|

Entry into Force

|

|

Australia–Japan EPA

|

15 January 2015

|

|

Australia–Malaysia FTA

|

1 January 2013

|

|

Australia–New Zealand CERTA

|

1 January 1983

|

|

Australia–US FTA

|

1 January 2005

|

|

ASEAN (Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Singapore, Viet

Nam)–Australia–New Zealand Free Trade Agreement

(‘AANZFTA’)

|

1 January 2010

|

|

Australia–Chile FTA

|

6 March 2009

|

|

Australia–Singapore FTA

|

28 July 2003

|

|

ASEAN (including Viet

Nam)–Australia–New Zealand

(‘AANZFTA’)

|

1 January 2010

|

|

P4 (Chile, New Zealand, Singapore and Brunei

Darussalam)

|

8 November 2006

|

|

NAFTA (Canada, Mexico and the United States of

America)

|

1 January 1994

|

|

US–Chile FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

Japan–Chile SEP

|

3 September 2007

|

|

Australia–Chile FTA

|

6 March 2009

|

|

Mexico–Chile FTA

|

31 July 1999

|

|

Chile–Peru ECA

|

1 March 2009

|

|

Malaysia–Japan EPA

|

13 July 2006

|

|

ASEAN (including Malaysia)–Japan

CEP

|

31 October 2008

|

|

Japan–Viet Nam EPÁ

|

1 October 2009

|

|

Japan–Singapore EPA

|

30 November 2002

|

|

Peru–Japan EPA

|

1 March 2012

|

|

Malaysia–New Zealand FTA

|

1 August 2010

|

|

Peru–US TPA

|

1 February 2009

|

|

Peru–Mexico TIA

|

1 February 2012

|

|

US–Singapore FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

Viet Nam–US Agreement on Trade Relations

|

13 July 2000

|

The TPP Intellectual Property Chapter (ch 18), like the vast majority of PTAs concluded by TPP members, largely followed the legal rights and obligations included in TRIPS. However, the TPP included commitments that expanded TRIPS commitments in issues such as geographical indications (‘GIs’), wines and distilled spirits, copyright and related rights and biological products.

Under the TPP, GIs[138] were eligible for protection as trademarks. This was an important departure from TRIPS, which deals with GIs separately from trademarks, becoming closer to the treatment that the US gives to geographical indications. Chapter 18 also required more stringent requirements with respect to the protection of new GIs, including provisions on transparency, due process, as well as safeguards regarding the use of terms that are customary in the common language. However, existing GIs pursuant to an international agreement were effectively grandfathered.[139] Special provisions on wine certification and analysis were included, basically eliminating these procedures as a general rule, which could be ordered only in cases of suspicion.

The TPP also marked the first time that a trade agreement signed by the US included annexes on specific products. TPP ch 18 included an Annex 8A on wines and distilled spirits that create common definitions of ‘wine’ and ‘distilled spirits’ to facilitate trade in these products. At the same time, the Annex established parameters for labelling and certification of wine products, while preserving the ability of regulators to ensure consumer protection.

The TPP also increased the terms of protection of copyright to be protected during the lifetime of authors and even 70 years after their death (art 18.63). Although some TPP signatories already have such protection (after amendments to its Federal Copyright Law in 2003, Mexico had set the standard to 100 years), some critics pointed out that if in the future these countries were to seek to reduce the time of protection, the TPP would have made this impossible.[140] But then again, these commitments were already locked out in other PTAs concluded by the same countries, like the US–Peru TPA (art 16.5.5) and the US–Chile FTA (art 17.5) that provide the same 70 years of protection, although some older treaties like NAFTA (art 1705) still include a shorter period of 50 years. Aiming to strike a balance between private protection and public interest, TPP arts 18.65 and 18.66 stipulated that each country shall give due consideration to legitimate purposes such as, ‘criticism; comment; news reporting; teaching, scholarship, research, and other similar purposes’.

Another ‘new’ and contested issue in the TPP was the protection of test data or other undisclosed data from the sanitary registration of pharmaceutical products, both for products of chemical synthesis and for biological products, for a number of years.[141] However, the issue was also not so new, as the US had negotiated this protection before. For example, in the US–Chile FTA, both countries recognised and guaranteed a period of protection of test data or other undisclosed data of five years from the sanitary registration of pharmaceutical product (both for products of chemical synthesis and for biological products). In principle, the TPP would have extended this protection to eight years, yet arts 18.50 and 18.51 of the agreement allowed an ‘alternative’ performance that does not involve the extension of three years but to ‘other measures, to provide a comparable result in the market’ — whatever that meant.

In sum, with respect to intellectual property, the TPP largely restated previous commitments undertaken by its signatories under TRIPS and prior PTAs, with more detailed provisions on controversial issues, especially on biological products, copyright and related rights.

The TPP followed the latest US model for services negotiations, diverting from the GATS. It considered services through six different chapters, namely: Investment, Cross-Border Trade in Services, Financial Services, Temporary Entry of Business Persons, Telecommunications and Electronic Commerce.[142] As a result, commercial presence or ‘Mode 3’ was treated in the Investment Chapter and movement of natural persons or ‘Mode 4’, in the Temporary Entry of Business Persons Chapter.

TPP signatories have included trade in services in almost all their existing FTAs, with the exception of Chilean PTAs with Malaysia and Viet Nam, the AANZFTA (including Brunei Darussalam, Singapore, Malaysia and Viet Nam),[143] and the Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Partnership among Japan and Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.[144]

There are 28 PTAs between TPP signatories which cover cross-border trade in services. Of them, 19 are PTAs with a ‘negative list’ approach for market access services liberalisation, mainly following the NAFTA model. The remaining nine PTAs follow the ‘positive list’ approach of GATS, as seen in the table below:

|

PTAs with ‘negative list’ approach for market

access

|

Entry into Force

|

|

Australia–New Zealand Closer Economic Relations

Services Protocol

|

1 January 1989

|

|

30 July 2008

|

|

|

P4

Agreement (Brunei Darussalam, Chile, New Zealand, Singapore)

|

3 June 2005

|

|

Peru–Singapore EPA

|

29 May 2009

|

|

22 August 2006

|

|

|

Singapore–Australia FTA

|

28 July 2003

|

|

US–Australia FTA

|

1 January 2005

|

|

US–Chile FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

US–Peru TPA

|

1 January 2009

|

|

US–Singapore FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

Australia–Japan FTA

|

15 January 2015

|

|

CanadaChile FTA

|

5 July 1997

|

|

Canada–Peru FTA

|

1 August 2009

|

|

17 April 1998

|

|

|

Chile–Japan FTA

|

3 September 2007

|

|

Peru–Japan FTA

|

1 March 2012

|

|

6 April 2011

|

|

|

NAFTA (Canada, Mexico and the United States of

America)

|

1 January 1994

|

|

29 May 2008

|

|

|

PTAs with ‘positive list’ approach for market

access

|

Entry into Force

|

|

AANZFTA

(ASEAN, Australia and New Zealand)

|

1 January 2010

|

|

Australia–Malaysia FTA

|

1 January 2013

|

|

Brunei–Japan EPA

|

31 July 2008

|

|

Malaysia–Japan FTA

|

13 July 2006

|

|

Mexico–Japan EPA

|

1 April 2005

|

|

Singapore–Japan EPA

|

30 November 2002

|

|

Viet Nam–Japan EPA

|

1 October 2009

|

|

26 October 2009

|

|

|

14 November 2000

|

Chapter 10 of the TPP consolidated the FTAs between its parties on cross-border trade in services by including standard provisions in national treatment, MFN treatment, market access and particularly prohibiting local presence requirements. The TPP prohibited any local presence requirements in art 10.6, stipulating that parties cannot require a service supplier of another party to have an office or ‘be resident in its territory as a condition for the cross-border supply of a service’.[145] This provision is commonly found in FTAs regulating services, and in the case of TPP countries, is present in FTAs such as Canada–Chile[146] or Australia–US.[147]

The chosen approach for trade in services liberalisation in the TPP was the negative list approach, by which parties fully liberalise all sectors and subsectors except for those excluded by each party in their respective schedule or list of non-conforming measures. These exemptions are set out in Annexes I and II of the Chapter. Annex I contains the standard list of exemptions with static commitments. Annex II comprises a list of reservations which are dynamic, as it gives TPP signatories full autonomy in regulating the inscribed services in the future. As may be seen in the table above, only three countries had never concluded a PTA by the negative list approach for services liberalisation with another TPP signatory: Brunei, Malaysia and Viet Nam.

In terms of market access, the TPP expanded the coverage to new markets for Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand and Viet Nam. These countries lack an FTA with the US. While a negative list approach has proven to expand further liberalisation in services compared to a positive list approach, what really makes the difference are the key sectors opened.[148] In general, compared to the Doha offers made by TPP members, the agreement improved on an average of around 40 per cent. This was particularly significant for TPP signatories like Brunei, Chile, Mexico, Peru and Singapore, while Australia, New Zealand and Viet Nam made small improvements.[149] According to Batshur Gootiiz and Aaditya Mattoo, for sectors like express delivery, portfolio management, energy and mining related services, the TPP would have made an impact,[150] while services commitments in basic telecommunications, financial services, professional services, retail distribution and transport suggested a limited level of liberalisation and only for a few countries (Malaysia in financial, legal and telecommunications services; Mexico in road freight transport services; and Viet Nam in retail and telecommunication services).[151]

In some cases, market liberalisation is not immediate. For example, Viet Nam’s commitments in retail distribution, were postponed by five years after the entry into force of the TPP. In a similar case, Malaysia’s commitments in financial services were deferred five years on certain cross-border direct insurance of risks linked to directors’ and officers’ liability.

However, the TPP also delivered some innovation in trade in services, expanding the scope of air transportation services (by adding specialty services,[152] airport operation services and ground handling services),[153] including a framework to negotiate mutual recognition agreements (‘MRAs’), commitments to liberalise professional services[154] and provisions on domestic regulation, ensuring ‘that all measures of general application affecting trade in services are administered in a reasonable, objective and impartial manner’.[155] Another novel aspect is the inclusion of an annex on express delivery services, aimed to balance the situation between private and state postal monopoly companies.[156] It is highly likely that TPP did not innovate in other issues, because of the then ongoing Trade in Services Agreement (‘TiSA’) negotiations, which involved several TPP parties (Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru and the US).

As with cross-border trade in services, the TPP’s regulation of financial services cannot be examined in isolation. Currently, there are 19 PTAs between TPP signatories with a chapter on financial services:

|

PTAs covering financial services in a special

chapter

|

Entry into Force

|

|

Australia–Japan FTA

|

15 January 2015

|

|

Australia–Malaysia FTA

|

1 January 2013

|

|

Peru–Japan FTA

|

1 March 2012

|

|

ASEAN (including Viet

Nam)–Australia–New Zealand

|

1 January 2010

|

|

Viet Nam–Japan EPA

|

1 October 2009

|

|

Canada–Peru FTA

|

1 August 2009

|

|

Peru–Singapore FTA

|

29 May 2009

|

|

Australia–Chile FTA

|

6 March 2009

|

|

US–Peru TPA

|

1 February 2009

|

|

Brunei–Japan EPA

|

31 July 2008

|

|

Chile–Japan FTA

|

3 September 2007

|

|

Malaysia–Japan FTA

|

13 July 2006

|

|

Mexico–Japan EPA

|

1 April 2005

|

|

US–Australia FTA

|

1 January 2005

|

|

US–Chile FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

US–Singapore FTA

|

1 January 2004

|

|

Australia–Singapore FTA

|

28 July 2003

|

|

Singapore–Japan EPA

|

30 November 2002

|

|

NAFTA (Canada, Mexico and the United States of

America)

|

1 January 1994

|

The TPP closely followed the treatment of this issue as considered in prior PTAs. Yet, the Financial Services Chapter (ch 11) innovated in three important topics,[157] as it contained specific commitments on the cross-border delivery of electronic payment card services, postal entities selling insurance to the general public[158] and on prudential regulations[159] of financial services.