Melbourne Journal of International Law

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne Journal of International Law |

|

FRONT-OF-PACK LABELLING AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW:

REVISITING THE HEALTH STAR RATING SYSTEM

Front-of-Pack Labelling and International Trade Law

Jessica C Lai[1]* and Shmuel I Becher[1]†

The Western world is suffering from an ‘obesity epidemic’, partly attributable to international trade. International trade has contributed to changes in diet, increases in pre-packaged food rich in sugar and salt, and an upsurge in obesity rates and non-communicable diseases. To address this, lawmakers have sought to provide consumers with more or better information, with the aim of nudging consumers towards healthier choices. In this vein, many countries have introduced interpretative front-of-pack (‘FoP’) schemes for food and beverages.

In 2014, Australia and New Zealand implemented the Health Star Rating (‘HSR’) FoP system. One of the major flaws of this system is that it is voluntary. Yet, if made mandatory, the HSR system would have a direct impact on the product labelling of international companies selling in Australia and New Zealand. It would, therefore, be more likely to face international scrutiny.

In this article, we propose that the HSR system be made mandatory. Thereafter, we analyse the compliance of a mandatory HSR system with international trade law. We conclude that Australia and New Zealand would need to narrowly frame their objectives for making the HSR system mandatory, backed by evidence. In doing so, Australia and New Zealand would likely have to recognise the FoP systems of some other jurisdictions.

Contents

The Western world is suffering from an ‘obesity epidemic’.[1] Around 60 per cent of Australian and New Zealand adults are overweight or obese.[2] More than 65 per cent of American adults are either overweight or obese.[3] In England, 61 per cent of adult females and 67 per cent of adult males are overweight or obese.[4]

Poor diets contribute to obesity.[5] Together, poor diets and obesity lead to serious negative consequences, including health-related issues.[6] In June 2019, the Australian government released its 2015 report on the burden of fatal and non-fatal disease.[7] The report concluded that 8.4 per cent of the burden of disease was attributable to being overweight or obese, and 7.3 per cent was attributable to dietary risks.[8] The report found that being overweight or obese and dietary risks are connected to cancer and cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, kidney, musculoskeletal, neurological and respiratory disease.[9] A similar New Zealand report, published in 2013, found that diet accounted for 3.8 per cent of health loss,[10] and that high body mass index accounted for 7.9 per cent of health loss.[11]

While not directly comparable,[12] the reports from both countries notably considered high intake of sodium, high saturated fat intake, and low vegetable and fruit intake as risk factors.[13] Furthermore, poor diets and obesity can impose a significant burden on public healthcare systems.[14] This, in turn, imposes costs on the workplace and the economy.[15] Alarmingly, unhealthy diets contribute to almost one-fifth of deaths globally.[16]

Manufacturers often have an incentive to use unhealthy components such as salt, saturated fats and sugar. Foods that contain generous amounts of these ingredients can create rewards in the brain by producing dopamine.[17] Accordingly, such foods are more tempting and pleasurable to eat;[18] they are ‘craveable’.[19] High levels of salt, saturated fats and sugar can also make poor quality foods palatable, and humans have biologically evolved to seek energy-dense foods.[20] At the same time, the food industry realises that consumers care about the healthiness of their food.[21] Producers, therefore, also have a strong profit incentive to blur reality and portray their products as healthy and natural.

The concerns around diet and packaging cannot be confined to domestic borders. The globalisation of food chains, partly attributable to free trade agreements (‘FTAs’), has been linked to increasingly unhealthy diets.[22] For example, one study shows a correlation between the implementation of the 1989 Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement and the increase of available calories in Canada.[23] Other studies show that FTAs and increased trade can result in nutrition transitions. This transition is often towards more processed foods and foods high in fats, salt and sweeteners, with corresponding increases in non-communicable diseases.[24] As trade liberalisation continues, the importance of regulating food and beverage packaging increases for both domestically manufactured and imported products.

Aware of the relationship between poor diets and negative health outcomes, Australia and New Zealand introduced the Health Star Rating (‘HSR’) labelling system for food and beverages in 2014.[25] The HSR system is government-backed, but voluntary and self-regulated.[26] It is not ‘pure’ self-regulation, however, as there is some government oversight and the rules are developed by industry and government together.[27] As outlined in this article, the non-mandatory nature of the HSR system is one of its greatest flaws. While Australia and New Zealand may wish to improve the HSR system and make it mandatory, such a move would have international trade law implications.

World Trade Organization agreements constitute the primary source of international trade law. The WTO system focuses primarily on reducing barriers to trade as a means to achieve other objectives, such as increasing living standards. With some exceptions, WTO agreements proscribe government measures that restrict trade. These can include regulation of both voluntary and mandatory label systems. Introducing a mandatory food health labelling system would likely be questioned vis-à-vis its WTO compliance.

This article addresses the voluntary nature of the HSR system and analyses the international trade law implications of making this system mandatory. The article’s main contribution is twofold. First, we argue that the HSR system should be made mandatory. Secondly, we examine how and under what circumstances a mandatory HSR system could be WTO compliant. The proposed analysis highlights that Australia and New Zealand should be careful when framing their objectives.

The article is organised as follows: Part II contextualises the logic behind the HSR system. Part III suggests an interdisciplinary approach, applying economic, behavioural and marketing rationales. It concludes that the HSR system must be mandatory to be effective. Part IV then examines whether a mandatory system would be compliant with Australia and New Zealand’s WTO obligations.[28] A brief conclusion follows.

Australia and New Zealand are close trading partners. They have been working towards removing trade barriers between the two jurisdictions since their first FTA in 1965.[29] This includes cooperation with respect to food standards,[30] primarily through Food Standards Australia New Zealand (‘FSANZ’).[31] FSANZ develops and maintains food standards for both countries.[32] The Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (‘Food Standards Code’) includes requirements relating to the labelling and composition of food and food related products.[33]

There is also the Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition Arrangement (a non-treaty arrangement), which came into effect in 1998.[34] It covers situations where FSANZ has not agreed upon a food standard. The Arrangement requires that the countries mutually recognise each other’s individual standards (including those of the individual states and territories of Australia).[35] This means, for example, that if food is produced in New Zealand in accordance with New Zealand standards, it can be legally sold in Australia.[36] This is true even if the food does not satisfy the equivalent Australian standards.[37]

A conventional means to address the ‘obesity crisis’ is to disclose nutritional facts and ingredients. Such disclosures can inform consumers about their nutritional choices. The Food Standards Code requires the disclosure of information on food labels, such as the ingredients, a use by or best before date, and a nutrition information panel.[38] The nutrition panel must include, for example, the quantity of protein, carbohydrate, sugars, fat and saturated fatty acids per average serving.[39] It should also detail how many servings the package contains.[40]

Information disclosures are mandated under the premise that they empower consumers to make informed decisions.[41] However, mandated disclosures frequently impact suppliers and producers more than they impact consumers.[42] One possible explanation for this is the ‘spotlight effect’.[43] According to this effect, disclosures lead producers to focus on the information disclosed.[44] This, in turn, prompts producers to attribute high salience to the information at stake.[45] As a result, producers are likely to overestimate consumers’ attention to the disclosure.[46]

Moreover, many consumers do not make good use of mandated disclosures in general and nutritional labels in particular.[47] Purely providing nutrition information and leaving it to the consumer to draw their own conclusions is non-directive. It means that the consumer is left with the burden of interpreting the information to assess the healthiness of food products. Empirical data indicates that consumers with prior information, including those who actively care about their diet, are those who tend to use nutrition labels.[48] Other consumers, however, are unlikely to make good use of such labels.

From an economic perspective, providing as much relevant information to consumers as possible may seem a sensible approach. As noted, it theoretically allows consumers to make informed decisions. However, as illustrated in the following paragraphs, a large body of evidence demonstrates that individuals depart from rational decision-making models in systematic and predictable ways. Regulators, therefore, have gradually come to realise that more information is not always better.[49]

One popular paradigm that explains why and how consumers deviate from rational economic behaviour is the concept of two systems of (or dual) reasoning.[50] This paradigm differentiates between an automatic and intuitive process (‘System 1’) and a controlled and deliberative process (‘System 2’). Whereas System 1 represents mostly unconscious behaviour that is more focused on present needs and desires, System 2 reflects planning, thinking and self-control.[51]

Most people do not use System 2 as often as they believe they do to make informed and careful decisions.[52] Instead, people are typically prone to unconsciously using, or being influenced by, System 1.[53] In the context of food packaging, consumers look at packaging in an intuitive way, rather than reading and deliberating over all the information provided. In this vein, consumers are likely to be influenced by the shape, colour, images and overall design of the packaging, not necessarily its informational labels.

There is, thus, a growing consensus that nutrition fact labels and lists of ingredients are not sufficiently effective.[54] As a result, regulators have been experimenting with other novel means to influence consumers’ nutritional choices.[55] These means are designed to more effectively and efficiently communicate with consumers. Such communication schemes have the potential to nudge consumers towards making healthier choices.[56]

In this respect, one of the most interesting and important regulatory developments is the focus on ‘targeted transparency’.[57] Acknowledging people’s cognitive limitations, regulatory initiatives seek to provide decision-makers with timely and effective information. Specifically, some regulators have adopted or supported schemes that provide consumers with an explicit label to communicate the health-related value of foods.

As illustrated in the following, these explicit labels often take the form of interpretative front-of-pack (‘FoP’) labelling. These labels provide simplified, often visualised, interpretations of nutrition information.[58] Such labels are designed to help consumers quickly and easily determine the healthiness of products.[59] They do this by relieving consumers of the burden of navigating technical language and dense text.[60] Slightly restated, these labels present consumers with the relevant information, which would otherwise go unnoticed,[61] in a visual and user-friendly way.[62] In essence, the labels are designed to be quick and easy to notice, understand and incorporate into consumers’ decision-making processes.[63]

In 2009, the Australia and New Zealand Food Regulation Ministerial Council commissioned the Review of Food Labelling Law and Policy.[64] An independent expert panel undertook the Review and published its findings in 2011.[65] Following the United Kingdom’s experience, the report recommended introducing a Multiple Traffic Light (‘MTL’) FoP labelling system.[66] The panel further recommended that the MTL system should be generally voluntary, but mandatory where ‘general or high level health claims are made or equivalent endorsements/trade names/marks appear on the label’.[67]

The rationale behind the MTL system is related to the operation of System 1, ie the quick and intuitive decision-making system. As illustrated by Figure 1, the colours employed by the MTL are supposed to help consumers easily determine the overall healthiness of products. Note that this label also utilises ‘reference intakes’ (or Guideline Daily Amounts (‘GDA’)) — these are the percentages shown on the label, which are calculated relative to an average adult’s recommended daily intake of the particular variable.[68] For example, in Figure 1, the 11 per cent for energy means that by consuming that grilled burger, one would consume 11 per cent of the average daily intake of energy recommended for adults.

Figure 1: Example of the MTL Label

Ultimately, the Legislative and Governance Forum on Food Regulation — later the Australia and New Zealand Ministerial Forum on Food Regulation (‘Food Regulation Forum’), made up of the Australian and New Zealand Food and Health Ministers — rejected the MTL label.[69] The reason given for this was that there was insufficient evidence that such a system would be effective in helping consumers.[70] Furthermore, the two governments found that the MTL system is overly focused on specific nutrients (such as fat, salt and sugar), as opposed to the healthiness of foods as a whole.[71] The respective governments were also wary of the anticipated resistance from food producers and manufacturers.[72]

Rather than adopting the MTL system, the Australian and New Zealand governments developed a new labelling scheme: the HSR system.[73] The governments selected the HSR system in part because it was considered more balanced, being ‘based on nutrients that are positive and negative’.[74] The HSR system was implemented in 2014.[75]

Figure 2: The most frequently used HSR system label[76]

The HSR label ranges from 0.5 stars, denoting the least healthy score, to 5.0 stars, indicating the healthiest products.[77] The rating is essentially determined by evaluating the overall nutritional value of the product. The rating compares the content of ‘good’ food components (ie fruit, vegetables, nuts, legumes, fibre and protein) with ‘bad’ components (ie energy, saturated fat, sodium and total sugar).[78] The exact way that ‘bad’ food components are offset by ‘good’ food components depends on the category of food.[79] To ensure consistency and reduce the risk of oversights, manufacturers can plug their data into an online calculator or a pre-programmed Microsoft Excel worksheet to generate the ratings.[80]

The New Zealand government and the Australian, state and territory governments co-fund the HSR system, covering the cost of administrative and evaluation activities.[81] The various jurisdictions fund monitoring and marketing in their respective localities.[82] The HSR system is governed ‘by the Food Regulation Forum, the Food Regulation Standing Committee (FRSC) and a number of committees established for the specific purpose of managing, monitoring and implementing the HSR system’.[83] The FRSC is composed of ‘[s]enior Australian, State and Territory and New Zealand government officials responsible for coordinating policy advice to the [Food Regulation] Forum’.[84] Below the FRSC is the Health Star Rating Advisory Committee, made up of ‘governments, industry, public health and consumer representatives responsible for overseeing the implementation of the HSR System’.[85] There are subordinate committees specialising in marketing and technical aspects (including the calculation of the HSR using Australian and New Zealand Dietary Guidelines).[86]

While the system is government supported and created together with the food industry, it is still voluntary.[87] Firms can choose whether to participate and display the HSR label on their product packaging. We return to this important aspect below, detailing the main drawbacks of implementing the HSR as a voluntary scheme.

Like the MTL label, the adoption of the HSR label may be best explained by reference to the dual reasoning model. The HSR system is supposed to provide consumers with one overall, easy and intuitive signal as to a food’s healthiness.[88] Simply put, the HSR label targets System 1, the automatic and intuitive system.

The HSR system offers five different labelling options.[89] Among these, the ‘HSR graphic only’ label (Figure 2) is the most frequently displayed.[90] There is a Style Guide, which dictates how the HSR labels can be displayed.[91] Understanding the HSR and other similar labels does not require significant mental effort. This has the potential to economise on consumers’ scarce time and attention.[92]

Ideally, the HSR system should mitigate incentives to produce unhealthy foods. Primarily, it might incentivise manufacturers to reformulate some of their products to achieve a better star rating.[93] Firms that opt to manufacture healthy food would be able to signal this to consumers using the HSR label. These firms would be able to better distinguish their healthy products from unhealthy ones.

One could further argue that the HSR system also has the advantage of not limiting the choices that market participants, both firms and consumers, can enjoy.[94] Firms can keep producing unhealthy products. Consumers, at the same time, are free to purchase whatever food they wish. They can select healthy or unhealthy products, with the HSR symbol on their packages or without it.

The Food Regulation Forum commissioned a review of the HSR system after five years of implementation, which culminated in the Health Star Rating System Five Year Review Report (‘Five Year Review Report’).[95] The report is largely positive about the HSR system. It does not recommend making the system mandatory, but makes proposals for increasing manufacturer uptake.[96] In December 2019, the Food Regulation Forum responded to the report, deciding to keep the system voluntary.[97]

All in all, there are a few additional reasons to believe that the HSR system will not be replaced or removed in the foreseeable future. As noted in the Five Year Review Report, manufacturers have steadily increased implementation of the HSR system.[98] That is, there is more and more industry buy-in. Thus, switching to an alternative FoP labelling system would impose significant switching costs on manufacturers.[99] Such manufacturers are, in any case, likely to oppose the adoption of a more effective regime that might undermine their profitability.[100]

Moreover, moving to a different FoP labelling system may create confusion among shoppers, who will need to become familiar with the alternative system. Therefore, replacing the HSR system is likely to be costly for regulators. This is because the introduction of a novel FoP labelling system will require governments to significantly invest in re-educating the public about the alternative measure. The fact that Australia and New Zealand have decided to reject the MTL system in the past (before adopting the HSR system) makes a change more unlikely.

Behavioural factors may further make this switch unlikely. First, the sunk cost effect results ‘in a greater tendency to continue an endeavor once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made’.[101] Here, it is assumed that ‘the larger the past resource investment in a decision, the greater the inclination to continue the commitment in subsequent decisions’.[102] In our context, governments and manufacturers have invested considerably in the HSR system, and they are thus susceptible to the sunk cost effect. Relatedly, regulators are likely to stick to the HSR system due to another behavioural phenomenon, dubbed the ‘status-quo bias’.[103] According to this bias, people strongly prefer maintaining the status quo. This is so even if by sticking to the existing option and remaining passive they fail to take advantage of superior alternatives.[104]

In light of these factors, the likelihood that Australia and New Zealand would replace the HSR with an alternative FoP labelling system is low. This is despite empirical evidence indicating that other FoP labelling systems might work better, depending on the measure being assessed.[105] Thus, we continue on the presumption that the HSR will remain the government-backed FoP labelling system in Australia and New Zealand, at least until the next review.

Elsewhere, we undertook a full analysis of the HSR system and ways to improve it, based on studies relating to different FoP systems.[106] One of the micro-level issues we had highlighted relates to the different ways in which the calculation of the HSR could be manipulated.[107] A prime example would be using fibre to achieve a good HSR for a product high in sugar.[108] Importantly, many of these micro-level calculation concerns have been resolved by the Food Regulation Forum’s response to the Five Year Review Report in 2019.[109]

Other issues we identified in earlier work relate to design features that could be improved. One example is the recommendation to place the HSR label on the upper left corner of a package to increase consumer attention.[110] Another is to use colours — red (0.5–2.5 stars), orange (3.0–4.0 stars) and green (4.5–5.0 stars) — to make the HSR signals more intuitive and effective.[111] The following Part discusses the shortfalls of the HSR system attributable to the fact that it is voluntary. We choose this focus because we believe this voluntariness affects the system’s efficacy at a macro level. Furthermore, making an FoP labelling system mandatory has specific international trade law implications, which we discuss in detail below.

As explained in the previous Part, the HSR and similar systems have the potential to advance market efficiency and public health. As noted, such systems may provide consumers with a clear and easy signal that they can intuitively use. However, as currently implemented, the HSR system’s effectiveness is questionable.[112] Indeed, the New Zealand Food Safety authority stated in a 2018 report that the impact of the system ‘does not currently translate to overall improvements in the healthiness of food purchased by New Zealand households (when weighted by food purchase data)’.[113] The equivalent Australian study made the same finding.[114]

Being voluntary, firms have the discretion to decide whether, when and how to engage with the HSR system. Not all manufacturers participate. It has thus been estimated that, as of 2018, only 30.5 per cent of eligible goods in Australia and 21 per cent of such goods in New Zealand displayed an HSR label.[115] The low uptake likely contributes to the fact that only 20 per cent of Australians and 16 per cent of New Zealanders recognised the HSR label unprompted.[116]

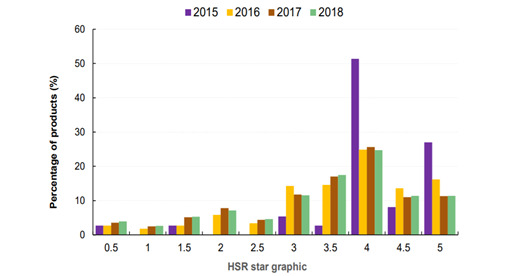

Those manufacturers who do opt to participate may use the HSR system strategically or manipulatively. Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate that the voluntary nature of the system allows companies to not label food with lower star ratings. It is true that the general rise in products displaying the HSR label led to an increased number of products bearing less than 3.0 stars. Nonetheless, a clear majority of the products with an HSR label, some 75 per cent of them, have at least 3.0 stars.[117]

As a result, consumers are less likely to form an accurate view of the overall healthiness of food. If almost all rated products are considered to be healthy or relatively healthy, the rating becomes less meaningful.[118] It also becomes less representative of the foods available for consumers.

Figure 3: Proportion of products displaying each Health Star Rating (Australia, 2015–18)[119]

Figure 4: Percentage of products displaying each Health Star Rating (New Zealand, 2015–18)[120]

On the positive side, a study published in 2019 found that the HSR label’s presence on products being compared helped participants select healthier products.[121] Notably, however, the researchers stated that when participants could not use the HSR label to make a comparison (because one product did not have the label), the participants used ‘less than optimal decision-making strategies’.[122] They thus concluded that a mandatory HSR system would enable consumers to better make informed decisions because it allows for comparison and provides reference points.[123]

The Five Year Review Report is positive about the uptake of the HSR system since its inception.[124] It sets a goal of reaching 70 per cent uptake by the end of 2023.[125] While the uptake has been steady,[126] there is no guarantee that this will continue. Even if the goal is reached, this does not mitigate manufacturers’ incentive to label only their healthier foods. While some manufacturers might reformulate some of their goods to achieve higher ratings, there will nevertheless be goods that cannot achieve a good rating and are thus likely to remain unlabelled. This results in consumers not having information presented in a standardised way for all goods.

Other behavioural patterns further undermine the HSR system’s effectiveness. For starters, consumers do not interpret missing information as a negative signal. One could argue that the absence of a label should lead a consumer to assume the worst. According to this line of reasoning, consumers should view a product without the HSR label to be equivalent to the lowest rating possible, 0.5 stars.[127] However, this is not the case. First, consumers are not always aware of what information could be disclosed.[128] Secondly, consumers do not always realise what information is missing.[129] Thirdly, consumers may not conclude that the missing information is disadvantageous.[130]

Generally speaking, consumers are unresponsive to missing information.[131] They either do not notice its absence or, if they do, they do not presume the worst.[132] This is reflected in data from New Zealand, showing that in 2018, 29 per cent of shoppers thought the HSR label was mandatory for packaged foods,[133] despite the fact that only 21 per cent of eligible products were labelled.[134]

As noted, if consumers do notice that information is missing, they do not perceive this negatively. Instead, consumers usually assume average quality.[135] Accordingly, consumers may ‘reduc[e] their purchases — but not to the extent they would if they were to learn actual bad news about the product’.[136] Thus, the Five Year Review Report’s statement that consumers could contribute to uptake by ‘demanding that manufacturers display the HSR across their entire product range’, in particular when they ‘are suspicious of products that do not display the HSR’,[137] is unrealistic. This is presumably different if it is mandatory information that is absent or if uptake is generally very high. In either case, the absence of the information would be more conspicuous. Under these circumstances, consumers are likely to notice that information dealing with salient attributes is missing.

Furthermore, the HSR system may bring about the ‘halo effect’. This effect causes people to rely on a global effect, rather than distinguishing between distinct and independent attributes of products.[138] Applied here, a high score on one product might create a positive perception vis-à-vis other products associated with the same brand or within the same category. Firms can take advantage of this effect by using the HSR label only with respect to their healthiest products, knowing that it might create a ‘halo’ over their unhealthier non-HSR-labelled products.

Related to the voluntary nature of the HSR, the system is also self-regulated.[139] Self-regulation has clear advantages. It reduces enforcement costs, preserves firms’ choice and minimises government intervention. However, it also gives rise to further scepticism towards the authenticity, reliability and effectiveness of the system.

Combined with the problems delineated above, consumers might be less likely to give much credit to self-interested firms that praise their own products. Indeed, in 2018, only 58.4 per cent of Australian consumers trusted the HSR, and credibility was at 61.5 per cent.[140] Trust among New Zealand shoppers was even lower. Only 40 per cent of New Zealand consumers trusted the HSR and 44 per cent believed it was something companies use as a marketing tool to sell more products.[141]

Moreover, if the system is voluntary, there is nothing to stop competing FoP labelling systems, or other health-related schemes, from being developed. This may include, for example, a private certification scheme. Unfortunately, competition between FoP labelling systems is likely to have negative consequences. One of the benefits of an FoP label is that it should be quick and intuitive to grasp. This benefit erodes if there are competing labels. Consumers will then have to first understand all competing labels,[142] then look more closely to determine exactly which label they are dealing with, and finally identify and take in the information.[143]

Furthermore, in developing competing labels, manufacturers can use empirical studies on FoP labels against consumer interests. This can lead to ‘industry capture’, whereby a system created in the interest of the public instead benefits industry.[144] For example, in 2017, six multinational food and beverage manufacturers created their own traffic light FoP system. These were Mars, Incorporated; Mondelēz International; Nestlé, Pepsico; The Coca-Cola Company; and Unilever.[145] However, instead of assigning colours based on a 100 g/100 ml reference, colours were designated based on portion size, which in turn was determined by firms at their own discretion.[146] This meant that manufacturers could avoid red labels by merely decreasing the portion size. These entities were therefore using consumers’ instinctive understanding of the traffic light colours in a misleading way.[147]

From yet another perspective, the existing HSR system may harm competition. Though it is government-backed, manufacturers that wish to capture those consumers who do notice and use the HSR label and do notice missing information must undertake the rating themselves. This imposes some costs on these businesses. Using the online calculator or pre-programmed Microsoft Excel worksheet may be too significant a burden for small businesses, which may have no resources to spare. Moreover, manufacturers also have to take on other costs, including costs of redesigning packaging, reprinting packaging and possibly writing off existing stock.[148] This may further disadvantage small businesses and make their products appear less attractive, even if these products are essentially healthy.[149] Thus, while some unhealthy products may receive a relatively high score under the HSR system, other healthy products — especially those manufactured by smaller businesses — may not be rated.

For these reasons, the HSR label should be generally mandatory for pre-packaged foods,[150] with the exception of fresh fruits and vegetables.[151] A mandatory HSR label would help consumers get a better overall impression of how healthy their food purchasing is. Making the system mandatory would also prevent firms from taking advantage of the halo effect, as they would not be able to place the rating only on their healthier products. This would also likely increase the use and awareness of the system and promote consumer trust. Indeed, empirical data supports making information disclosures around food healthiness mandatory, even with respect to more traditional labelling requirements.[152]

As noted in Part II, some disclosures are known to have more of an effect on firms than on consumers. This insight may also support the adoption of a mandatory regime. Even if a mandatory regime does not necessarily impact all consumers as anticipated, the spotlight effect may still encourage more firms to offer healthier products to consumers.[153]

It is important to acknowledge that making the system mandatory entails a variety of costs. These include legislation, education, enforcement and, potentially, litigation costs. These costs are important to keep in mind when designing the system. That said, disclosures are generally considered to be an inexpensive and minimally intrusive way to reduce information gaps.[154] In light of the stakes involved, and given the interest governments should have in improving citizens’ health, we suggest greater government regulation and subsidisation of the HSR system.[155]

We propose continued (perhaps even increased) funding for promotion of the HSR system.[156] Manufacturers should continue to bear the burden of calculating the HSR as they are in the best position to do so, given that they have all the relevant information. However, the costs related to redesigning or reprinting packaging may be relatively high for small businesses.[157] Thus, small businesses might need more time, in the form of extended deadlines, to implement the mandatory system.[158] Whether a business qualifies for the extended deadline could be based on objective measures such as its annual turnover, which reflects the fact that the costs of implementing the HSR system are significant for such a small business. Regarding existing stock, there could be a time-limited waiver exempting it from the mandatory labelling.

Finally, the Australian and New Zealand governments should randomly monitor compliance and penalise certain non-compliances. Greater enforcement is likely to reduce the chances that firms will fail to comply or incorrectly calculate the HSR.[159] Overall, these measures would better ensure a more systematic, objective and supervised application across the various producers and products.[160] It would also increase consumer trust in the HSR system.

In sum, it is imperative to allow all businesses to participate in the programme without unreasonably raising operational costs. This would prevent a situation where less profitable or smaller businesses find it hard to participate. It would also eliminate the concern of costs associated with the adoption of the system being rolled onto consumers. Moreover, it would enable a governmental agency to collate all HSRs and post all information under one single website or in one app. This may assist shoppers who wish to seek and verify health-related information before making shopping decisions.

Any government regulation of packaging might fall within the jurisdiction of the WTO. Of course, many countries have mandatory labelling requirements, such as the listing of ingredients. These requirements must also be compliant with WTO law. However, most requirements are never assessed by a WTO panel or its Appellate Body.[161]

Disputes tend to arise when there is no international consensus about the matter and where no international standard exists. As explained below, this may be the case even if the regulation remains voluntary. This Part examines the HSR system in light of WTO law — something the Australian and New Zealand governments did not cast significant attention to in their decision to implement the system.[162]

The examination below starts by contextualising the HSR system within the WTO regime.[163] A comprehensive analysis of the HSR system as per international trade law follows. While the analysis focuses on the HSR system, its implications are broadly applicable to any FoP labelling system.

One of the core aims of the WTO regime is to reduce barriers to trade, as embodied in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (‘GATT’).[164] A single mandatory nutrition labelling scheme in Australia and New Zealand could reduce barriers to trade between these two countries, as well as any country that adopts a similar scheme. As noted above, it is better for consumers to have a single functional system, rather than multiple competing labelling systems. However, if the HSR system were to become mandatory, this might increase barriers to trade vis-à-vis traders from outside Australia and New Zealand. This is because they would be forced to adopt the HSR system to trade in Australia and New Zealand.[165]

Article XX of the GATT has a general exception for measures necessary to protect human life or health.[166] This is under the proviso that the measure is ‘not applied in a manner which would constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail, or a disguised restriction on international trade’.[167] Measures to protect human life or health might fall under the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (‘SPS Agreement’).[168] If a measure is consistent with the SPS Agreement, it is presumed to be in accordance with art XX of the GATT.[169]

A mandatory HSR system could also fall under the WTO Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (‘TBT Agreement’).[170] Note, however, that the SPS Agreement applies exclusively.[171] In other words, if it applies, the TBT Agreement does not. The SPS Agreement and TBT Agreement delineate when technical barriers to trade (‘TBT’) are allowed.[172] Compliance with the TBT Agreement does not, in and of itself, mean that art XX of the GATT is satisfied.[173] Nevertheless, and as discussed in the following section, the nature of allowed technical barriers means that it would likely be satisfied.[174]

The following examines whether a mandatory HSR system would be permissible under these agreements.

A sanitary or phytosanitary (‘SPS’) measure includes a measure applied to ‘protect human or animal life or health within the territory of the Member from risks arising from additives, contaminants, toxins or disease-causing organisms in foods, beverages or feedstuffs’.[175] This includes ‘all relevant laws, decrees, regulations, requirements and procedures including, inter alia, ... packaging and labelling requirements directly related to food safety’.[176]

While created for the protection of human health, it is unlikely that a mandatory HSR system would be an SPS measure. There is no clear delineation between an SPS measure and a technical barrier to trade measure. However, there is a general understanding that the SPS Agreement applies to measures regarding the spread of pests and diseases, food safety and ‘additives, contaminants [and] toxins’ that are in some way unnatural or out of place (such as food colouring).[177] This is in contrast to measures relating to the provision of information about normal food nutrients that are not typically considered additives, contaminants or toxins, even if over-consumption may be detrimental for one’s health.

The HSR system is a general labelling requirement.[178] Based on the prevailing perspective, this measure is not meant to ensure that food and beverages meet a certain health and safety standard to be deemed acceptable for human consumption.[179] Rather, the HSR system provides consumers with information for them to make informed choices.

Furthermore, while one can certainly argue that saturated fat, energy, total sugar and sodium can pose risks to human health, it is questionable whether they constitute ‘additives, contaminants, toxins or disease-causing organisms’.[180] Taking the ordinary meaning of these nutrient terms, they are not ‘contaminants, toxins or disease-causing organisms’.[181] Read in its context, ‘additives’ must relate to safety or the spread of pests or diseases. Hence, it does not include saturated fat, energy, total sugar and sodium, which are currently common nutrients in foods and beverages. This is in contrast, for instance, to added hormones and pests on agricultural products, dealt with in prior decisions.[182] This understanding of the SPS Agreement is consistent with the way that the Food Standards Code has been set up, with one part dealing with nutrition information[183] and separate parts dealing with contaminants and toxins, and microbiological elements.[184]

Therefore, it is unlikely that the SPS Agreement applies. We thus turn to the TBT Agreement.

The TBT Agreement regulates ‘technical regulations’ and ‘standards’.[185] While the former pertains to mandatory requirements,[186] the latter relates to any ‘[d]ocument approved by a recognized body, that provides, for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines or characteristics for products or related processes and production methods, with which compliance is not mandatory’.[187] As we are proposing that the system be made mandatory by law, we shall continue our analysis based on technical regulations.

A ‘technical regulation’ is defined as a

[d]ocument which lays down product characteristics or their related processes and production methods, including the applicable administrative provisions, with which compliance is mandatory. It may also include or deal exclusively with terminology, symbols, packaging, marking or labelling requirements as they apply to a product, process or production method.[188]

The Appellate Body has clarified that technical regulations must be applicable to identifiable products or a group of products.[189] They must also ‘[lay] down’ (set forth, stipulate or provide) ‘product characteristics’, ‘prescribed or imposed with respect to products in either a positive or a negative form’.[190] Technical regulations can relate to the product or its related characteristics, such as ‘the means of identification, the presentation and the appearance of a product’.[191] Finally, compliance must be mandatory.[192]

A non-voluntary HSR system clearly falls within this definition. Such a regime would stipulate mandatory packaging, marking or labelling requirements for a group of products (foods and beverages).[193] It is worth noting that a technical regulation is mandatory if the measure is de jure (as a matter of law) or de facto (as a matter of fact) mandatory.

For instance, the Appellate Body ruled in United States — Measures concerning the Importation, Marketing and Sale of Tuna and Tuna Products that a de jure voluntary ‘dolphin-safe’ label was a technical regulation.[194] The United States had different evidentiary rules for the use of its ‘dolphin-safe’ label, depending on where the tuna was caught.[195] This made it more difficult for fisheries from some countries than those from others to use the label. Although tuna sold in the US did not need to have the label,[196] any claim about dolphin safety had to be compliant with the US regulations.[197] This made the use of the US label mandatory in practice.[198]

The following analysis is, thus, potentially relevant even if the HSR system is not made mandatory by law. However, as discussed above, uptake of the HSR system has been relatively low, as is trust in the system. Furthermore, only 23 per cent of all consumers in Australia and 28 per cent of shoppers in New Zealand reported using the HSR system.[199] In addition, it is possible to set up and use an alternative label. Thus, it is unlikely that one could say that consumer behaviour or market reality dictates that the HSR system is de facto mandatory.

The fact that the TBT Committee, rather than the SPS Committee, has discussed FoP labelling systems multiple times further supports the argument that the TBT Agreement is indeed the applicable framework.[200] For example, in 2007, the US queried the TBT Agreement compliance of Thailand’s proposal to introduce colour-grade and GDA FoP labelling requirements for snack foods (covering energy, total sugar, total fat and sodium content in gross amounts and relative to GDA: see Figure 5).[201] The US also queried how exactly said proposal determined the definition of a snack food.[202]

Figure 5: An Example of Thailand’s Voluntary GDA Label[203]

As a further illustration, 11 WTO members raised concerns in the TBT Committee about Chile’s mandatory FoP labelling system, implemented in 2016.[204] Chile’s label consists of black octagons that indicate when ‘critical nutrients’ (sodium, sugar, saturated fat and energy content) are over threshold limits (Figure 6).[205] Interestingly, Australia was one of these 11 members.[206]

Figure 6: Chile’s Mandatory FoP Label[207]

It is thus unquestionable that the TBT Agreement is applicable for a government-backed HSR system. The following discusses whether the HSR system complies with the TBT Agreement.

Article 2.1 of the TBT Agreement allows technical regulations under the condition that imported products are ‘accorded treatment no less favourable than that accorded to like products of national origin’ (national treatment (‘NT’) principle).[208] Furthermore, imported products must be accorded treatment no less favourable than ‘like products originating in any other country’ (most-favoured-nation (‘MFN’) principle).[209] That is, a country must not discriminate against imported products vis-à-vis ‘like’ local products and ‘like’ products from other countries.[210] There cannot be a ‘detrimental impact on competitive opportunities in the relevant market for the group of imported products vis-à-vis the group of domestic like products’ or ‘like’ products imported from elsewhere.[211] This includes de jure and de facto discrimination.[212] However, it does not apply where the ‘detrimental impact on imports stems exclusively from a legitimate regulatory distinction’.[213]

Whether products are ‘like’ depends on the nature and extent of competition between the products.[214] One determines whether products are ‘like’ by looking at a variety of factors. These include consumers’ tastes and habits; end uses in a given market; the products’ properties, nature and quality; and tariff classification.[215]

Our proposed mandatory HSR system would differentiate between pre-packaged food and beverages on the one hand and fresh fruits and vegetables on the other. It should be clear that pre-packaged food and beverages are not ‘like’ products with fresh fruits and vegetables.[216] This becomes evident when looking at consumers’ tastes and habits; end uses of the products; and products’ properties, nature and quality. At the same time, as the system would apply to all pre-packaged foods, domestic and imported, it is difficult to find a point of discrimination.[217] Our proposed mandatory system is, thus, de jure non-discriminatory.

There may nevertheless be de facto discrimination. This might be if the measure disproportionately affects imported products and thereby appears to be a disguised restriction on international trade. However, it is hard to imagine how this could be the case with respect to a mandatory HSR system, as it would apply to all pre-packaged foods and beverages.

Furthermore, the Australian and New Zealand governments would have a strong argument that any ‘detrimental impact on imports stems exclusively from a legitimate regulatory distinction rather than reflecting discrimination against the group of imported products’.[218] There is nothing about the design, architecture, operation or application of the HSR system that is not ‘even-handed’ so as to discriminate against imports.[219]

To illustrate, it is possible that the measure could disproportionately affect imported pre-packaged fruits and vegetables, compared to local fresh fruits and vegetables. However, there is a legitimate regulatory distinction, as packaged fruits and vegetables often have sugar, salt or fat added. It is worth noting that the Five Year Review Report recommended that fruits and vegetables, whether fresh, frozen or canned (with no added sugar, salt or fat), should automatically get 5.0 stars.[220]

A more difficult distinction exists with baked goods: local, freshly baked goods do not need to be packaged, but imported baked goods must be packaged. This may mean that locally baked goods must also have an HSR label to avoid discrimination; for example, on the cabinet window in the bakery or café where they are sold. This is aligned with the objective to provide consumers with valuable information that may improve their decision-making.

Article 2.2 of the TBT Agreement states that technical regulations must not be ‘prepared, adopted or applied with a view to or with the effect of creating unnecessary obstacles to international trade’.[221] This means that ‘technical regulations shall not be more trade-restrictive than necessary to fulfil a legitimate objective, taking account of the risks non-fulfilment would create’.[222] Legitimate objectives include the prevention of deceptive practices and the protection of human health.[223] To assess such risks, WTO members can consider, amongst other things, ‘available scientific and technical information, related processing technology or intended end-uses of products’.[224]

It would be quite cynical to argue that FoP labelling systems, like the HSR system, were intentionally implemented to create unnecessary obstacles to international trade. There is nothing in the HSR system discourse and history to substantiate such a claim. In any case, in the absence of statements regarding subjective intention, the test is objective. Thus, whether a mandatory HSR system would be compliant with art 2.2 of the TBT Agreement depends on whether the regulation is

(a) for a legitimate objective, including:

(i) the prevention of deceptive practices, or

(ii) the protection of human health;

(b) not more trade-restrictive than necessary to fulfil that legitimate objective;

considering, amongst other things, ‘available scientific and technical information’ or ‘intended end-uses of products’.[225] We address these now in turn.

A WTO panel does not merely accept a country’s statement as to its objective. Instead, it must establish for itself what a country’s legitimate objective is. Regarding FoP labelling systems, there are objectives that are undoubtedly legitimate: better informing consumers and protecting human health.

There is a consensus amongst WTO members that reducing obesity and related diseases is a legitimate objective.[226] As discussed above, poor diets are related to negative health outcomes, including those related to obesity. If done correctly, FoP nutrition labelling can provide consumers with easy-to-absorb information, which may assist them in making healthier food choices.[227]

Furthermore, a mandatory HSR system would give consumers a more accurate overview of the healthiness of food available, reduce the halo effect and increase consumer trust in the HSR system. This would allow consumers to more effectively use the HSR label, while nudging them towards healthier choices than they would otherwise make. Consumers making healthier choices, in turn, reduces obesity rates and related diseases, thereby protecting human health. A further objective of a mandatory FoP labelling system could be to incentivise manufacturers to reformulate their foods to be healthier in order to be able to display more stars on their HSR label. This would further protect human health.

Mandatory FoP labelling systems could also prevent deceptive practices. Again, HSR labels provide consumers with accurate and noticeable health information.[228] Such labels, therefore, can prevent manufacturers from hiding or failing to disclose nutritional information. The prevention of deceptive practices promotes transparency more generally.[229]

The list of ‘legitimate objectives’ is non-exhaustive.[230] WTO panels and the Appellate Body give members a reasonable degree of deference around what might be a ‘legitimate objective’.[231] Indeed, the preamble of the TBT Agreement states that ‘no country should be prevented from taking measures necessary ... for the protection of human ... life or health, ... or for the prevention of deceptive practices, at the levels it considers appropriate’, subject to the provisions of the Agreement.[232] Thus, ‘it is up to the Members to decide which policy objectives they wish to pursue and the levels at which they wish to pursue them’.[233] In our context, it could include economic objectives such as lowering the diet-related costs to public healthcare or to the labour market.

The TBT Agreement does not expressly require that a measure be based on scientific justification. Rather, it requires an assessment of whether there is a legitimate objective.[234] If there is, it mandates that the measure fulfil this objective in the least trade-restrictive manner possible.[235]

There is no minimum threshold of fulfilment.[236] Instead, the measure must be capable of making (and indeed make) some contribution towards its objective.[237] The HSR system satisfies this requirement of a de minimis contribution towards the objective of providing easy-to-absorb information for consumers to make informed choices. It limits manufacturers’ ability to hide or manipulate information and may assist with combating obesity and related diseases.

The TBT Agreement does not prohibit all measures that in some way have a ‘limiting effect on trade’.[238] Instead, it proscribes ‘unnecessary obstacles’ to trade.[239] This must be the case, since all technical regulations are, to some degree, trade-restrictive. Thus, the ‘trade-restrictiveness of the measure at issue’ is assessed for necessity.[240] According to the Appellate Body, the TBT Agreement is ‘concerned with restrictions on international trade that exceed what is necessary to achieve the degree of contribution that a technical regulation makes to the achievement of a legitimate objective’.[241]

The Appellate Body has outlined the following considerations for determining whether a measure is ‘more trade-restrictive than necessary’:[242]

(i) the degree of contribution made by the measure to the legitimate objective at issue; (ii) the trade-restrictiveness of the measure; and (iii) the nature of the risks at issue and the gravity of consequences that would arise from non-fulfilment of the objective(s) pursued by the Member through the measure.[243]

The degree of contribution relative to a legitimate objective is determined quantitatively or qualitatively, depending on a measure’s characteristics vis-à-vis its design, structure, expected operation and ‘the nature, quantity, and quality of evidence available’.[244] The Appellate Body has been clear that this analysis might be more or less precise, depending on the exact facts at hand.[245]

Ascertaining whether a measure is more trade-restrictive than necessary involves a comparative analysis.[246] It requires considering ‘the trade-restrictiveness and the degree of achievement of the objective by the measure at issue’,[247] compared to an alternative measure that is ‘reasonably available and less trade restrictive than the challenged measure’.[248] One also factors in the risk of non-fulfilment of the legitimate objective,[249] assessed in qualitative and/or quantitative terms, depending on the type of risk being analysed.[250]

The Appellate Body has stated that the ‘weighing and balancing’ of all these factors involves a ‘holistic analysis’.[251] This may include looking at imprecise and qualitative variables with respect to the degree of contribution to a legitimate objective, as well as the risks of non-fulfilment.[252] These risks must nevertheless be given ‘active and meaningful consideration’ when weighing and balancing all the relevant factors.[253]

It is for the complainant to identify comparable and available alternative measures and argue that these are less trade-restrictive.[254] The respondent can then rebut this by providing arguments and evidence that the challenged measure is not more trade-restrictive than is necessary to achieve its contribution toward the legitimate objective.[255] The respondent can achieve this by showing that the identified alternative measure is not less trade-restrictive.[256]

Applied to the HSR system, studies show that interpretative FoP labels can be an effective way to convey information to consumers. As noted, such labels may help consumers make better-informed decisions. These labels can also operate to prevent manufacturers from misleading consumers by manipulating information.

Manufacturers tend to be concerned with the trade-restrictiveness of mandatory FoP labelling systems. One of the main concerns is the potential need to comply with several different labelling systems in order to trade in multiple jurisdictions.[257] That being said, labelling requirements are relatively minimalistic in their trade-restrictiveness. They do not, per se, affect how a product is manufactured or what its contents are.

The absence of an effective FoP label increases the risk that consumers might not attempt to work out the nutrition value of a product based on its ingredients list. They might not have the knowledge, time, patience or skills to do so. Employing the behavioural jargon discussed above, consumers are more likely to use System 1 (the intuitive decision-making system) in making food choices. This can distort their perspective and lead them astray.

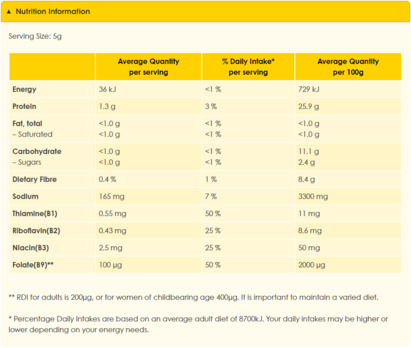

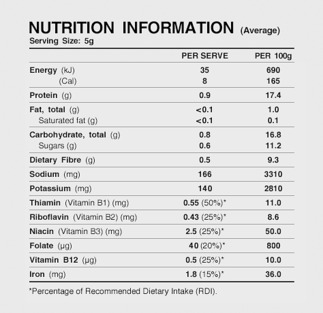

It is difficult to imagine an alternative measure that is reasonably available, less trade-restrictive and would be as effective in (1) conveying information to consumers and (2) reducing the impact and prevalence of misleading representations.[258] It is true that merely providing nutrition information (see Figures 7 and 8) is less trade-restrictive. However, when presented in that form, nutritional information is much less likely to be noticed, understood, correctly interpreted and employed by consumers.[259]

Figure 7: Nutrition Information for Marmite[260]

Figure 8: Nutrition Information for Vegemite[261]

Similarly, non-interpretative FoP labels, such as a GDA label (as used in Thailand: see Figure 5), would likely be less trade-restrictive than the HSR label. However, GDA labels are not as effective in increasing consumer literacy or helping and nudging consumers to make better decisions.[262] In contrast, the HSR is an interpretative label. It embodies multiple factors to provide consumers with a single indication as to overall healthiness, which consumers can look at and use intuitively.

Thus, requiring the provision of nutrition information or GDAs might be less trade-restrictive and reasonably available. But these requirements would not make an equivalent contribution towards the legitimate objectives of providing consumers with important yet easy-to-interpret information. They are also not as effective in preventing manufacturers from deceptively hiding, or failing to disclose, nutritional information. The risks related to this are high.

Voluntary labelling schemes are often portrayed as viable options.[263] However, our discussion in Part III outlines the ineffectiveness of voluntary schemes such as the HSR system in its current form. As implemented, it does not achieve the legitimate objective of ensuring that consumers can make informed decisions when purchasing food.

Finally, educational campaigns have also been suggested as a less trade-restrictive measure.[264] Yet, it is questionable whether educational campaigns alone could suffice to meet the legitimate objectives of ensuring that consumers have the relevant information and effectively disciplining producers.[265] After all, consumers most often use System 1 automatic and intuitive decision-making when making daily purchases, and producers and marketers are well aware of this. It is, therefore, dubious whether education alone could effectively ameliorate deceptive practices, or whether consumers would act on their recall of an educational programme when making real-time purchasing decisions. Therefore, educational efforts should only supplement a mandatory interpretative FoP labelling system, making it more effective. It should not replace labelling altogether.

Moreover, there is no reason why a state would only have to use one measure. Australia and New Zealand already require ingredients lists and nutrition information panels,[266] while also running educational campaigns around healthy eating and physical exercise.[267] Indeed, the implementation of alternative measures in concert with the measure at stake can make that measure more likely to be TBT Agreement compliant.[268] If a country uses a suite of measures to meet a legitimate objective, an opponent cannot argue that one of those is an alternative to the other. This is because ‘[s]ubstituting one element of this comprehensive policy for another would weaken the policy by reducing the synergies between its components, as well as its total effect’.[269]

We next discuss two specific, related issues involved in defending a measure. The first is the use of evidence. The second is how to frame the legitimate objective.

The foregoing highlights the importance of getting the design and structure of the labelling system correct. This should be done based on scientific and empirical evidence drawn from a variety of fields, including biology, behavioural sciences, economics and marketing. Otherwise, the chosen measure might not contribute towards the legitimate objective, or its contribution might not be commensurate with its level of trade-restrictiveness. Furthermore, basing the system on sound evidence reduces the likelihood of there being an alternative that addresses the legitimate objective in a less trade-restrictive manner. If there were such an alternative, the respondent would not be able to show that the absence of the measure would entail a significant risk of the legitimate objective not being fulfilled.

It can be challenging to provide the necessary evidence to show the exact degree of contribution of a measure towards its legitimate objective. The problem that the measure is trying to address might be a new or developing threat.[270] Similarly, the design and structure of the measure might be novel, meaning that the evidence possibly does not yet exist.[271] Or perhaps there might only be very little evidence, which may be of poor quality or based on a different jurisdiction with a different culture and/or biological environment.

In addition, the regulation of public health is complex, affected by multiple variables and complementary measures. It might be difficult, or at times impossible, to provide evidence on the effects of one particular measure when a variety of measures have been implemented and are intended to work in a synergistic fashion.[272] Moreover, a measure might be implemented as part of a long-term strategy. Evidence relating to the short-term effects might be misrepresentative. It is also possible that evidence relating to a newly implemented measure might be marred by industry response to the measure (eg by changing marketing or prices).[273] In a similar vein, it can be difficult to provide evidence relating to predictions about the future.[274]

Nevertheless, to maximise compliance with the TBT Agreement, there needs to be a clear link between existing research, the design of the measure and the legitimate objective that the measure seeks to achieve.[275] This link will have to show that the effect of the HSR label on consumer literacy is stronger compared to that of ingredients lists and nutrition panels; that there is a positive impact of mandatory labels on consumers in terms of trust, a reduction of the halo effect and a greater understanding of the food available; that such systems incentivise manufacturers to reformulate their goods to be healthier; that the HSR system contributes to consumers making informed decisions; and that the HSR system contributes to consumers making healthier choices.

States are given a significant amount of leeway in defining their legitimate objectives.[276] At the same time, the evidence required regarding a measure’s necessity and trade-restrictiveness in comparison to an alternative measure hinges on the identified legitimate objective. To fend off any TBT Agreement challenges, states should frame their legitimate objectives vis-à-vis existing scientific evidence.

To illustrate, it might be difficult to adduce evidence that the HSR system reduces consumption of unhealthy foods and beverages and thereby lowers obesity rates. For instance, the positive impact of the HSR system might be counterbalanced by other societal and technological developments, and many factors can impact obesity rates. Thus, when making the system mandatory, Australia and New Zealand could instead state in their policy documents that the objective of a mandatory HSR system is to better inform consumers so that they can make decisions more effectively. It is not easy to prove causation between labelling, purchasing choices and health outcomes. In contrast, it is somewhat easier to show the relationship between design choices and packaging literacy.[277]

This means that Australia and New Zealand should frame their legitimate objective as narrowly as possible. A broadly framed legitimate objective exposes them to arguments that a multitude of alternative measures could fulfil the objective in question in a less trade-restrictive way. In contrast, the narrower the legitimate objective, the less likely that an opponent will be able to show that there is a less trade-restrictive measure that could achieve the legitimate objective without risking the objective not being fulfilled.[278]

While it is beyond the scope of this paper to analyse the trade-restrictiveness of the different FoP labelling systems, one can presume that there may be an FoP labelling system that is less onerous to calculate and implement. Suffice it to say that various FoP labelling systems have different advantages and disadvantages for packaging literacy and purchasing choice modulation.[279] Australia and New Zealand would have to frame their legitimate objective based on the empirical advantages of the HSR system.

An unavoidable potential challenge to the HSR system would be the scientific basis behind the selection of factors taken into account (the balancing of good ingredients and bad ingredients) and the thresholds used in the algorithm to determine the star rating.[280] That said, the algorithms are based on Australian and New Zealand dietary guidelines,[281] which are in turn based on relevant scientific studies. There is established research around what food intake (and in what quantities) is healthy and unhealthy. This data, though evolving and sometimes challenged, is generally accepted by entities such as the World Health Organization.[282] Moreover, as we have analysed elsewhere, there is an abundance of literature on the most effective interpretative FoP labels, including their colour, shape, placement on packaging and amount of contained information.[283]

All of this underscores that it is vital to undertake continual research about the impact of a measure and to take an evidence-based approach to lawmaking and policymaking. This is particularly true given that the TBT Agreement states that if circumstances or objectives change, technical regulations shall not be maintained or should be amended if the new circumstances or objectives could be addressed in a ‘less trade-restrictive manner’.[284]

Article 2.4 of the TBT Agreement states that where relevant international standards exist, members must use them to form the basis of their technical regulations.[285] This is unless ‘such international standards or relevant parts would be an ineffective or inappropriate means for the fulfilment of the legitimate objectives pursued’.[286]

One should note that there is a tension between WTO law, international standards developed in other fora and regulation at the domestic and supranational level.[287] Different interest groups will invoke either international trade law or international standards, depending on their perspective.[288] This aside, according to the TBT Agreement, if a technical regulation is adopted for one of the explicitly mentioned legitimate objectives and complies with relevant international standards, it is ‘rebuttably presumed not to create an unnecessary obstacle to international trade’.[289]

There must be a relevant international standard, and the measure at issue must be ‘in accordance with’ this.[290] A standard is ‘relevant’ if it has ‘bearing upon’ or relates to the matter at hand, or is ‘pertinent’ to the domestic regulation.[291] There is a standard when there is:

• a document;

• approved by a recognised body;

• that provides rules, guidelines or characteristics;

• for products or related processes and production methods;

• for common and repeated use; and

• compliance with these rules, guidelines or characteristics is not mandatory.[292]

A standard is international when it is created by a body ‘that has recognized activities in standardization and whose membership is open to the relevant bodies of at least all [WTO] Members’[293] ‘at every stage of standards development’[294] on ‘a non-discriminatory basis’.[295]

Australia and New Zealand work together with the Codex Alimentarius Commission (‘CAC’) to develop technical regulations.[296] The CAC is a joint initiative of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization.[297] This initiative creates voluntary international food standards, guidelines and codes of practice concerning the safety, quality and fairness of international food trade.[298]

The CAC is an internationally recognised standard-setting body.[299] The CAC has a general standard and guidelines that relate to information disclosures for pre-packaged foods.[300] These only pertain to basic information that must be placed on food packaging. At the time of writing,[301] the CAC did not have a standard on FoP nutrition labelling.

The Codex General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods (‘Labelling Standard’) requires that certain information be displayed on a product’s packaging.[302] This includes the name of the food, a list of ingredients, net contents and drained weight, name and address of manufacturer, country of origin, and important dates and storage instructions.[303]

There are also the Codex Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling,[304] which mandate nutrient declarations when nutrition claims are made.[305] For example, let us assume that a producer would like to employ a statement that suggests a food has particular nutritional properties. This statement may relate to the energy value or the content of protein, fat, carbohydrates, vitamins or minerals of the food (‘nutrition claim’).[306] Such a statement should be accompanied by a ‘standardized statement or listing of the nutrient content of a food’ (‘nutrient declaration’).[307] Therefore, a nutrition claim such as ‘low in fat’ would have to be accompanied by a nutrient declaration of the actual fat content.

There are also the Codex Guidelines for Use of Nutrition and Health Claims, which deals with the use of nutrition and health claims in food labelling and advertising.[308] It refers to the Codex Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling.[309] It additionally gives ranges for when ‘free’ and ‘low’ can be used with respect to energy, fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sugars and sodium.[310] Furthermore, it stipulates when the terms ‘source’ and ‘high’ can be used with respect to protein, vitamins and minerals, and dietary fibre.[311] Moreover, it regulates when health and dietary claims, as well as ‘non-addition’ and comparative claims, can be made.[312]

One might conclude that the CAC standard and guidelines outlined in the foregoing are relevant because they have bearing upon the HSR system. They are, after all, about labelling food products. However, as set out in Table 1, this is not the case.

Table 1: Relevant CAC Standard and Guidelines and their Applicability to FoP Labelling

|

Standard/Guidelines

|

Applicability to FoP Labelling

|

|---|---|

|

Codex General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged

Food

|

Requires that packaging have: the food name, an ingredients list, net

contents and drained weight, name and address of manufacturer

etc, country of

origin, important dates and storage instructions, and similar information.

Applicability: Not relevant for interpretative FoP labelling.

|

|

Codex Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling

|

Requires that nutrition claims be accompanied by nutrient declarations

(‘standardized statement or listing of the nutrient content

of a

food’).

Applicability: Not relevant for a visual and qualitative FoP label

such as the HSR. However, may be relevant for a GDA FoP label, as these labels

are quantitative (see Figure 1 and Figure 5).

|

|

Codex Guidelines for Use of Nutrition and Health

Claims

|

Gives ranges for when ‘free’ and ‘low’ can be used

with respect to energy, fat, saturated fat, cholesterol,

sugars and

sodium.

Stipulates when the terms ‘source’ and ‘high’ can

be used with respect to protein, vitamins and minerals,

and dietary fibre.

Regulates use of comparative, ‘non-addition’, health and

‘healthy diet’ claims.

Applicability: Ineffective or inappropriate to fulfil the legitimate

objectives pursued.

|

The Labelling Standard has some beyond-standard recommendations.[313] These state that ‘[a]ny information or pictorial device written, printed, or graphic matter may be displayed in labelling’.[314] This is under the condition that the information or device is consistent with the mandatory requirements of the Labelling Standard[315] and does not make claims that are ‘false, misleading or deceptive or [are] likely to create an erroneous impression regarding its character in any respect’.[316]

The Codex Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling also make statements about ‘supplementary nutrition information’, which ‘is intended to increase the consumer’s understanding of the nutritional value of their food and to assist in interpreting the nutrient declaration’.[317] It states that such information ‘should be optional’, given only in addition to the nutrient declaration.[318] There is an exception ‘for target populations who have a high illiteracy rate and/or comparatively little knowledge of nutrition’.[319] For these populations, ‘food group symbols or other pictorial or colour presentations may be used without the nutrient declaration’.[320] As discussed above, evidence suggests that the average consumer has low packaging literacy. They use System 1 intuitive reasoning and do not understand ingredients lists and nutrition tables. They also often do not have the necessary attention span or time to read nutrition tables and panels. Thus, the nature of such supplementary information should be reconsidered.

The Codex Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling further states that consumer educational programmes should complement supplementary nutrition information ‘to increase consumer understanding and use of the information’.[321] There is a body of evidence illustrating that non-mandatory labels, constructed incorrectly and without complementary educational programmes, are less helpful for consumers of low socio-economic status (generally those with lower literacy and lesser nutritional knowledge).[322] Hence, one could argue that mandatory labelling, developed based on evidence about FoP labelling literacy and implemented in conjunction with educational programmes, would satisfy the Codex Guidelines on Nutrition Labelling.

Overall, the Labelling Standard and the two guidelines are ‘ineffective or inappropriate means for the fulfilment of the legitimate objectives pursued’.[323] They are ineffective as they cannot accomplish the pursued legitimate objective of providing consumers with easily absorbable nutrition information.[324] The Labelling Standard and the guidelines are also inappropriate as they are not ‘specially suitable’ for ensuring that consumers can more readily make informed decisions.[325] They are not designed to help the consumer judge the overall nutritional quality of the food.

Where there is no relevant international standard or if a WTO member opts not to follow a relevant international standard, and if the proposed regulation may have a significant effect on trade, the WTO member must notify other members of the proposed regulation.[326] The notification should give enough time for comments to be made and for the regulation to be considered before implementation.[327] The notification should include the products to be covered by the proposed regulation and an indication of its objective and rationale.[328] Once implemented, there must be a reasonable period before the measure enters into force, to ‘allow time for producers in exporting Members, and particularly in developing country Members, to adapt their products or methods of production to the requirements of the importing Member’.[329]

In light of the conclusion that an FoP labelling system goes beyond any international standard, Australia and New Zealand would have to notify other members prior to making the HSR system mandatory. Before doing so, they should be clear about their legitimate objectives and how these relate to existing research, and tailor the HSR system around these objectives and research.

The past 30 years are characterised by rising trade liberalisation, consequential changes in diet, increases in pre-packaged food and an upsurge in obesity rates and non-communicable diseases. To counter this, many countries have introduced interpretative FoP labelling schemes, designed to nudge consumers towards healthier choices. As part of this movement, Australia and New Zealand introduced the HSR system in 2014.