Melbourne Journal of International Law

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne Journal of International Law |

|

LEGAL ANALYSIS OF THE ARGENTINE AND AUSTRALIAN TITLES TO TERRITORY IN ANTARCTICA

Argentine and Australian Titles to Territory in Antarctica

Bruno Arpi,[1]* Jeffrey McGee,[1]⁑ Andrew Jackson[1]† and Indi Hodgson-Johnston[1]‡

Antarctic territorial claims are important for understanding the history and future possibilities of the Antarctic region. Although the 1959 Antarctic Treaty put on hold arguments about territorial claims over the continent, these claims still play a role in shaping the Antarctic Treaty System. To understand these disagreements, it is important to consider the legal basis of the respective claims. One of the key disagreements is between the United Kingdom and Argentina, which have overlapping claims to areas of West Antarctica. European states have generally assumed that the whole of the Antarctic continent was terra nullius when the UK first claimed a part of West Antarctica in 1908. However, Argentina claims that it inherited part of the ‘South American Antarctic’ from Spain in the early 19th century and has effectively exercised its rights derived from that title. On the other side of the continent, areas of East Antarctica were claimed for the British Commonwealth and later transferred to Australia. The UK and Australia recognise each other’s claims. The existing analysis of Antarctic law has not properly considered whether any future outcome of the territorial dispute between the UK and Argentina might legally impact the Australian claims in East Antarctica. This article, therefore, considers the legal basis of the Argentine and Australian claims. We conclude that regardless of any future outcome of the Argentinian-British territorial dispute, there is no overt legal conflict between the Argentinian and Australian claims to Antarctic territory; they may both legally co-exist.

Contents

The Antarctic Treaty has recently celebrated the sixtieth anniversary of its entry into force.[1] The Treaty is considered a remarkable international legal instrument that has directed human presence in the area below sixty degrees South latitude towards peaceful use and scientific research. While the acquisition of territory in Antarctica has been the ‘Antarctic Problem’, the Antarctic Treaty has also managed the differing attitudes to territorial claims, including the potential for international conflict over the overlapping claims of Argentina, Chile and the United Kingdom in the Antarctic Peninsula.[2] Article IV of the Treaty effectively suspends conflict over territorial claims, keeping the status quo on rights and claims as it was in 1961 when the Treaty entered into force.[3]

Territorial sovereignty over the Antarctic continent is a complex issue. Argentina and Australia, together with Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the UK, are the seven states that have asserted rights to, or claimed territorial sovereignty over, areas of the Antarctic continent (see Figure 1). The United States and the Russian Federation have not recognised these rights and claims, and each asserts the ‘basis of a claim’, that is, they have reserved the right to make their own claims to parts or all of Antarctica. While no territorial claims have universal recognition, the claims made by Argentina, Chile and the UK are the most politically contentious in that they contain significant geographical overlap.[4] The British claim completely overlaps the Argentine claim and partially overlaps the Chilean claim. Chile and the UK claim some areas of Antarctica that are not subject to any counterclaim. Despite the Argentine and Chilean claims partially overlapping, they recognise that each have sovereign rights, arguing that they only need to negotiate the boundary between their respective territories.[5] The other four Antarctic claims do not overlap. Australia, France, New Zealand, Norway and the UK recognise each other’s claims and boundaries.[6] Argentina does not recognise the Australian claim and neither does Australia recognise the Argentine claim.[7]

Figure 1: Antarctic Claims

Some might suggest that discussion of territorial claims in the Antarctic is ‘obsolete’,[8] as art IV of the Antarctic Treaty has put on hold disagreement over their legitimacy.[9] However, the main and original ‘problem’ of the region has not disappeared. The issue of territorial sovereignty, and maintenance and continued assertion of that sovereignty, is still as live an issue as it was in the 1950s.[10] Territorial sovereignty claims over different parts of the continent are important for understanding not only the Antarctic history but also future possibilities for the Antarctic region and the Antarctic Treaty System (‘ATS’). As Karen Scott explains, ‘the very existence of the disputed claims has influenced, shaped, and, arguably, limited the development of the [ATS] and, consequently, indirectly impacts on the rights and obligations of all states operating within the region’.[11] On the other hand, we might argue that the existence of such fundamental disagreements facilitated the development of the ATS, as it put in place the mechanisms for cooperative decision-making. Territorial claims in Antarctica have not been abandoned or extinguished by art IV, and they continue to exert influence on states’ actions within the ATS and in other related international institutions. An example of how the claimant states consider their Antarctic claims as part of their national territories can be seen in their submissions to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (‘CLCS’), as formed under the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea.[12] The seven states that assert rights of, or claims to, territorial sovereignty in Antarctica have either included in their submissions data for the seabed extending from the coast of their Antarctic claimed territories (Argentina, Australia, Chile and Norway) or reserved the right to make such submission at a later date (France, New Zealand and the UK). Thus, it is important that the legal basis of the territorial claims of the seven claimant states, and the possibility of other claims (such as from the US and Russia), are not overlooked or forgotten.

While the claimant states apply the ‘sector principle’ for determining the geographical limits of their Antarctic territories,[13] from the analysis of the different justifications for asserting their Antarctic territories (titles to territory) two broad but significantly differing views of the legal status of Antarctica at the beginning of the 20th century are evident.[14] First, European states (and in this context, we include Australia and New Zealand) have considered the international legal status of Antarctica as terra nullius (ie land that is not under the sovereignty or authority of any state) and therefore capable of being acquired by a state through discovery and subsequent occupation.[15] These claims constituted an annexation of parts of Antarctica to the national territory of the claimant state. From the 19th century, international law stipulated that the discovery of terra nullius did not by itself establish a full legal title to sovereignty.[16] Discovery of territory was considered to create only an ‘inchoate title’ (i.e. incomplete or partial title) that was able to be ‘perfected’ (i.e. made complete or full) by acts evidencing effective occupation of the claimed territory, as long as the area of the claim was not under the authority of another state.[17] The territorial claims of Australia, France, New Zealand, Norway and the UK were made on this basis. These states have assumed that the legal status of the whole of Antarctica was terra nullius at the time the UK first officially claimed part of West Antarctica in 1908.

Second, there is the South American approach to Antarctic territorial claims. Argentina and Chile argue that their Antarctic territorial claims ‘constitute a natural extension of what they regard as their national boundaries’.[18] For these states, the ‘South American Antarctic’ was an integral part of the Spanish colony which they legally inherited from Spain and have effectively possessed, such that it was not terra nullius in 1908 when Britain first claimed Antarctic territory.[19] Moreover, Argentina argues there was no need for it to make an express declaration of territorial annexation over Antarctic territory, as the ‘Argentine Antarctic Sector’, as inherited from Spain in 1810, has since that time been an integral part of the territory of the country. Unlike the claims by the European states, the Argentine claim has not been based on formal annexations and decrees.[20] Shirley Scott, who has extensively addressed the two distinct approaches pertaining to territory in Antarctica, explains that:

[w]hereas ‘new imperial’ writers regard Argentina and Chile as having announced their ‘claims’ in the 1940s, some understanding of the regional context within which Argentina and Chile were operating demonstrates that their actions can better be regarded in terms of proposals regarding the location of their mutual boundary in territory to which they considered themselves to have long since perfected their rights.[21]

The Argentinian and Chilean claims to Antarctic territory, therefore, proceeded on a very different legal basis to that of the European, Australian and New Zealand claims.[22]

International law does not allow for the occupation of territory which is already under the sovereignty of another state. The legal status of Antarctica at the moment of the European claims is therefore crucial.[23] This article aims to critically assess the legal validity of the Argentine titles of sovereignty to Antarctica to examine whether these territories might be considered terra nullius when the UK officially claimed the region in 1908, and to what extent this modified the legal status of the continent. If the Argentinian claim to Antarctic territory was found to be legally valid, this might have legal implications for other claims to Antarctic territories, such as the Australian claim. The legal basis of the British claim to Antarctic territory is well-known in Antarctic studies since the UK introduced them when they instituted proceedings before the International Court of Justice (‘ICJ’) against Argentina and Chile concerning disputes as to the sovereignty over their overlapping Antarctic claims in 1955.[24] Legal analysis of the Australian claim has also been considered by English-language scholars.[25] However, as Shirley Scott has argued, the Argentinean and Chilean titles to Antarctic territory have been ignored by the UK and other European powers. This argument is clearly supported by the British submission to the ICJ, which makes no reference to any other basis of claim. Contrarily, significant legal analysis of the Argentinian territorial claim has been done in Spanish by Latin American scholars.[26] However, this has not been replicated in Antarctic literature published in English. Therefore, little or no consideration has been given to the study of whether a legally valid Argentine claim would affect the validity of the claim made by Australia. These two claims are selected to limit the scope of the paper but offer a conceptual lens with broader application to consider the legal basis of other claims. For instance, Argentina’s legal basis could inform Chile’s, while Australia’s could inform others (i.e., France, New Zealand and Norway).

Whether Argentinian and Australian territorial claims in Antarctica conflict is of more than academic importance. Article IV of the Antarctic Treaty has preserved the status quo over the Antarctic territorial claims during the life of the Treaty:[27] these claims were never abandoned. If the Antarctic Treaty were ever to cease, the architects of the Treaty intended that the legal status of the territorial claims would revert to the pre-Treaty situation. Territorial disputes vis-a-vis parties to the Antarctic Treaty would most likely be considered under the situation prevailing at the time of entry into force of the Treaty in 1961. There also remains the longer-term possibility of a state withdrawing from the Antarctic Treaty (and the Madrid Protocol), perhaps due to unwillingness to be bound by the non-militarisation obligations or interest in commencing mineral resource exploitation.[28] There is also the ongoing possibility of a ‘third party state’ (ie, a state not within the Antarctic Treaty or Madrid Protocol) taking steps to occupy or extract resources from areas that are subject to territorial claims.[29] Such action would likely see the relevant claimant state asserting its territorial rights against the third-party state. Territorial claims in Antarctica, and the legal relationship between these territorial claims, remain an important consideration for the future of Antarctic governance. The rules of international law on territorial sovereignty would likely provide substantial guidance to the diplomatic negotiations between Antarctic states that would no doubt ensue.

Therefore, we analyse the implications of accepting the basis of the Argentine titles to Antarctic territory for the Australian claim to territories in East Antarctica. By examining the key legal features of the Argentine and Australian claims, we aim to critically assess whether accepting the legal basis of Argentine titles to Antarctic territory might affect the legal basis of the Australian claim. In other words, we analyse whether the Argentinian and Australian claims can legally co-exist or are in conflict.

This article, therefore, proceeds as follows. Part 2 provides an outline of the rules of international law relevant to the acquisition of territory by states in Antarctica. Part 3 examines the Argentine titles to territory as part of the ‘South American Antarctic’, including arguments on how Spain obtained the original titles to territory in Antarctica and whether it acted as the sovereign of this territory. This section then critically analyses Argentina’s claim to have inherited Spanish territories, including in Antarctica, and whether it has exercised effectivités in those areas. This part allows us to assess the extent to which Antarctica might be legally considered terra nullius in 1908. Part 4 examines the possible implications of the validity of the Argentine titles to territory for Australian territorial claims in East Antarctica. To do so, we analyse the Australian titles to territory in Antarctica. Part 5 analyses whether the Argentine and Australian claims over Antarctic territories are legally in conflict or whether they can co-exist. The Antarctic Treaty has successfully governed the continent, and it is likely to continue doing so into the future. Nevertheless, we understand that due to the influence of the Antarctic claims on shaping the ATS, it is important to properly consider their legal merits if the ATS were ever to unravel. In Part 6, we conclude by indicating that, although the Argentinian and Australian claims have a different legal basis, they are not in conflict. It follows that any future finding that the Argentine title to territory in Antarctica is legally valid would not, in our view, undermine or weaken the Australian sovereignty claim to the Australian Antarctic Territory (‘AAT’).

Argentina and Australia (like Chile, New Zealand and South Africa) have direct interests in Antarctica, which derive from their geographical proximity to the continent — for example, weather, ocean currents, fisheries and defence strategies.[30] Some states have used these national interests as additional evidence of their claims to Antarctic territory. For instance, Argentina’s main legal title to Antarctic territory is based on the effective occupation of part of the ‘South American Antarctic’, but it has always complemented this with geopolitical concepts such as the geographical proximity to Antarctica and geological contiguity of the Argentine mainland territory with Antarctica. Although these geographic, geological or climatological considerations do not constitute a valid legal title to territories, they may play a secondary role in the acquisition of territories. For instance, they may be useful to delimit the boundaries of territorial claims through the application of the sector principle.

To analyse the legal basis of Antarctic claims, it is important to remember that acquisition of territory by states is governed by the rules of international law as they applied at the time of acquisition.[31] The acts or facts that states rely on to constitute the legal foundation for the establishment of a right over territory are called ‘title[s] of territorial sovereignty’.[32] The term ‘title’ is preferred to the ‘traditional modes of acquisition’ of territorial sovereignty (cession, effective occupation of terra nullius, accretion, conquest or subjugation, and prescription)[33] because these are not able to embrace all the different ways by which territorial sovereignty is established.[34] When a dispute arises over a territory, these titles, which include some of the traditional modes of acquisition of territorial sovereignty, are complemented by other technical rules, such as the ‘intertemporal law’[35] and the ‘critical date’.[36] They are also complemented by fundamental principles of international law, such as respect for the territorial integrity of states, the right to self-determination of peoples and obligations to settle international disputes through peaceful means.[37]

The practice generally in international law with territorial disputes is that the states involved advance arguments that relate both to the existence of title and effectivités. Doctrine and case law use the French term ‘effectivités’ to refer to acts undertaken in the exercise of state authority through which a state manifests its intention to act as the sovereign over a territory.[38] According to Marcelo G Kohen, ‘[c]onditions for effectivités relate both to the entity performing them, and the specific nature of the acts performed’.[39] In other words, effectivités are the acts carried out by a state relevant to a claim of title to territory by ‘effective occupation’. In Antarctica, however, with its unique and inhospitable geography, the nature of the acts performed by the claimant states to assert sovereignty requires careful analysis. It has been argued that the standard of ‘effective occupation’ of territory applied to the acquisition of territory in more temperate lands is not appropriate for Antarctica.[40] Instead, the amount and type of human activity required to establish an effective occupation of territory may vary with the circumstances of the case, such as the geographical nature and circumstances of the region.[41] As Judge Huber stated in the 1928 Islands of Palmas Case:

Manifestations of territorial sovereignty assume, it is true, different forms, according to conditions of time and place. Although continuous in principle, sovereignty cannot be exercised in fact at every moment on every point of a territory. The intermittence and discontinuity compatible with the maintenance of the right necessarily differ according as inhabited or uninhabited regions are involved, or regions enclosed within territories in which sovereignty is incontestably displayed or again regions accessible from, for instance, the high seas.[42]

Rothwell suggests that the concept of ‘effective occupation’ has a particular interpretation in Antarctica due to the difficulty of fulfilling its requirements in the region.[43] In the 1933 Eastern Greenland Case, the Permanent Court of International Justice commented upon what activities might amount to effective occupation by a state of polar areas (in that case, areas of Eastern Greenland). The Court noted that:

It is impossible to read the records of the decisions in cases as to territorial sovereignty without observing that in many cases the tribunal has been satisfied with very little in the way of the actual exercise of sovereign rights, provided that the other State could not make out a superior claim. This is particularly true in the case of claims to sovereignty over areas in thinly populated or unsettled countries.[44]

Further, Ian Brownlie indicates that generally the standard of conduct required for a claimant to establish ‘effective occupation’ is one which emphasises ‘state activity, and especially acts of administration’, noting that occupation does not necessarily signify actual settlement.[45] Effective occupation does not necessarily signify actual settlement as states can ‘effectively occupy’ a territory by other means, such as carrying out administrative acts.[46] This would appear to be the established and accepted practice, for example, in remote and inhospitable sub-Antarctic islands. Thus, in relation to Antarctic areas, Juan C Puig argues that effective occupation should be understood as all those means through which a state shows its intention to acquire or maintain sovereignty (animus and corpus occupandi) over Antarctic regions.[47] Further, as Malcolm Shaw suggests, territorial sovereignty is not an absolute element; it may be divided, and property ‘is a bundle of rights capable of modification, division and adjustment’.[48]

Nevertheless, international law does not allow the acquisition of territory by occupation that is already under the effective occupation of another state. Therefore, the legal status of Antarctica at the time of the official European claims plays a paramount role. If the Argentine titles to Antarctic territory were legally valid at the time, and therefore the ‘South American Antarctic’ could not be considered terra nullius, it would automatically defeat the competing British Antarctic claims. The next part examines the Argentine titles in order to assess whether or to what extent Antarctica could be considered terra nullius when Great Britain first claimed territory in West Antarctica in 1908.

‘Argentine Antarctica’ or the ‘Argentine Antarctic Sector’ (Antártida Argentina or Sector Antártico Argentino in Spanish) is an area of approximately 1.42 million km² in Antarctica claimed by Argentina as part of its national territory consisting of the Antarctic Peninsula and a triangular sector extending to the South Pole, delimited by the parallel 60° South and the meridians 25° and 74° West. These last two boundaries correspond to the extreme longitudinal limits of Argentina: 74º West marks the westernmost point of the limit with Chile (Cerro Bertrand, Santa Cruz Province) and the 25º West meridian corresponds to the South Sandwich Islands and represents the easternmost point.[49] The ‘Argentine Antarctic Sector’ is administratively governed by a department of the province of Tierra del Fuego, Antarctica, and South Atlantic Islands. Argentinian activities in Antarctica are coordinated by the Dirección Nacional del Antártico (‘DNA’), under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade and Worship. The DNA oversees the Argentine Antarctic Program which is supported by the Ministry of Defence. Currently, Argentina has 13 Antarctic stations — six permanent and seven summer stations.

Figure 2: Map of the ‘Argentine Antarctic Sector’ and the ‘Australian Antarctic Territory’ extended, for convenience, to 60° South latitude (the limit of the Antarctic Treaty area) so as to include the offshore islands

As explained, Argentina anchors its claim on this sector by virtue of both the ‘sector principle’ and effective exercise of sovereignty over part of the ‘South American Antarctic’. Argentina argues that it has effectively possessed and administered a sector of Antarctica since 1810 when it inherited this territory that had been an integral part of the Spanish Colony. In order to assess the validity of the Argentine titles, we need to assess, first whether the ‘South American Antarctic’ was part of the Spanish colonial territory; second, whether after Argentina succeeded this territory from Spain, it has continued and perfected its rights over this territory.

This part will first explain how Spain might have acquired the original title to territorial sovereignty and exercised effectivités in part of Antarctica, as was required by the international law of the time. It will then examine how Argentina argues that it continued and perfected these rights over the ‘South American Antarctic’ such that these territories should not be considered as terra nullius in 1908.

The Antarctic Sector claimed by Argentina was an integral part of the Spanish Empire during the colonial period from the 15th to the 19th century, mainly by virtue of the demarcation made by Papal Bulls, the Treaty of Tordesillas, and recognition by other European states. Significantly, the British Empire gave express recognition. Spain considered these territories as part of its colonies and effectively exercised its authority with an intention to act as the sovereign of this region, as was required by international law at the time.

The acquisition of territories by ‘pontifical letters, known as Papal Bulls, was a standard procedure in the European Late Middle Ages in accordance with the public law of the time’.[50] For instance, the Bull Laudabiliter of 1155, issued by Adrian IV, gave the English King Henry II lordship over Ireland, and the Bull Super rege et regina of 1297 granted Corsica and Sardinia to King James II of Aragon in 1297.[51] Bulls were a valid title at the time, and the Bull Inter Caetera allowed the Spanish Crown the acquisition of original titles of territorial sovereignty in the law and practice of European colonial expansion.[52]

The original Spanish title over the ‘South American Antarctic’ region derives from the Bull Inter Caetera issued by Pope Alexander VI on 4 May 1493. The Bull divided the ‘New World’ between Portugal and Spain.[53] The Bull expressly indicated that the Spanish dominion constituted all territories to the west of an imaginary line – the meridian 46 – extending ‘from the Arctic pole, namely the north, to the Antarctic pole, namely the south’.[54] The Bull Dudum siquidem of 1493 supplemented the Bull Inter Caetera and purported to grant to Catholic Monarchs:

all islands and mainlands whatsoever, found and to be found, discovered and to be discovered, that are or may be or may seem to be in the route of navigation or travel towards the west or south, whether they be in western parts, or in the regions of the south and east and of India.[55]

Afterward, the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494, which modified the line of demarcation between both Iberian Crowns (ie, Portugal and Spain), established a straight-line boundary at a distance of 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands ‘drawn north and south, from pole to pole, on the said ocean sea, from the Arctic to the Antarctic pole’ (see Figure 3).[56] This bilateral treaty between Portugal and Spain received no objection from England at the time of its entry into force and was confirmed by Pope Julius II by means of the Bull Ea quae pro bono pacis of 1506.[57]

It is important to note that the Bulls Inter Caetera were accepted by England and France when they were issued in 1493. At that time, both England and France were still part of the ecclesiastical legal order of the Catholic Church and considered the Pope as the highest legal authority over Christian princes. At that time, England’s responses to Spanish and Portuguese claims were ‘based on the geographical application of the Bull Inter Caetera’, and its legitimacy was not challenged.[58] It ‘took more than fifty years for Queen Elizabeth of England to contest the papal Bull Inter Caetera as a ‘donation’ to Spain, despite recognising Spain’s sovereignty over the regions in which it had established settlements or made discoveries’.[59]

The Bulls and the Treaty of Tordesillas were very clear on the scope of the Spanish dominions, with both documents stating that the Spanish territories in America reached the South Pole. Since ancient times, different peoples speculated about the existence of the Terra Australis Incognita, a continental land in the Southern Hemisphere as it was referred to in different ancient documents (for instance, Aristotle mentioned an Antarctic region in his book Meteorology in 350 BC). Although several maps suggested the existence of an enormous land in the south of America (for instance, Da Vinci’s world map of 1513), it was not until Magellan navigated through the strait that today bears his name, joining the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean in 1520, that we can observe several maps and documents describing the South American Antarctic region with more details (Barreda Laos calls this period ‘the Magellanic period’).[60] From documents and maps of the 16th century, it is possible to see that under the denomination of Tierra del Fuego, Magellanic Sea, and Terra Australis, the domain of the South American Antarctic region was considered as naturally incorporated into the Spanish continental dominance in America (for instance, Monachus’ world map of circa 1526, Rumold Mercator’s world map of 1569, Ortelius’ world map of 1970, Ortelius’ Maris Pacifici of 1589, or Cornelis van Wytfliet’s world map of 1598) (see Figure 4). Then, the ‘South American Antarctica’, albeit unexplored and little known at that time, was within the area under Spanish sovereignty.

Figure 3: Franciscus Monachus, Illustrations de Orbis situ ac descriptione ... (1524–1527) (exc. J. Vuithagius 1565).[61] These maps show the hemispheres of the globe as granted to the King of Portugal (left) and Spain (right) by the 1493 Bulls Inter Caetera and the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas

The Spanish Crown considered the Antarctic regions as part of its domains and intended to exercise control over these territories, as demonstrated by the letters patent given by the Spanish King Charles V to Pedro Sancho de Hoz in 1539, Pedro de Mendoza in 1543 or Juan Ortiz de Zárate in 1569.[62] Several examples show that Spain exercised real and effective jurisdiction over the known territories in the extreme south of its domains. At the end of the 16th century, the viceroy of Peru, Don Francisco Toledo, heard a rumour that English and Dutch expeditions were trying to establish colonies in the southern part of the Spanish colony. In order to expel these foreign settlements, Spain sent an expedition under Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa to inspect Tierra del Fuego in 1579. However, it was found that there were no such settlements in the area. Again, when Spain became aware that two Dutch sailors, Schouten and Le Maire, had discovered and sailed past Cape Horn in 1616, immediately and in order not to leave doubts about its dominions over these territories, it sent the expedition of the brothers Bartolomé García de Nodal and Gonzalo de Nodal to exercise control over Tierra del Fuego and the territories further south. Once more in 1672, the viceroy of Peru, Baltazar de la Cuerva, sent a warship and two auxiliary ships to eliminate any foreign settlement in the extreme southern regions. This expedition verified that there were no foreign settlements and left a document affirming Spanish dominion over the region.[63]

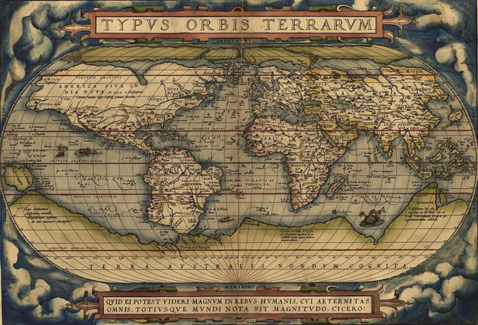

Figure 4: A Ortelius. Typvs Orbis Terrarvm (Gilles Coppens de Diest 1570).[64] Following the Strait of Magellan, Tierra del Fuego appears to the south, forming part of what is called Tierra Australis Nondvm Cognita, an immense snowy landmass that penetrates the Antarctic circle and reaches the south pole.

The Spanish animus possidendi over territories in the American southern zones and its adjacencies can be demonstrated inter alia with the formation of the government of the Malvinas on 4 October 1766 under the dependence of the Governor and Captain-General of Buenos Aires.[65] Spain maintained in the Malvinas a permanent establishment in charge of populating, exploring, and controlling the fishing and hunting of seals in the region. For better administration, Spain incorporated its South American Antarctic territory to the Governorate of the Río de la Plata and later confirmed this as part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata created by a Royal Decree in 1776.[66]

In summary, Spanish rights over Antarctic territories were essentially based on the delimitation made by the Bull Inter Caetera which was accepted as a valid title for the acquisition of terra nullius lands and consequently also applicable to the British Empire. Some authors have argued that with the evolution of international law in subsequent centuries acquisition of territory by Bulls has lost validity.[67] However, the Spanish rights in this part of America were recognised by other European powers including, in particular, the British Crown. British recognition of the Spanish rights was made under numerous legal instruments agreed by both states including the Second Treaty of Madrid of 1670, the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, and the Treaty of San Lorenzo del Escorial or Nootka Sound Convention of 1790. Under these treaties, the British Crown explicitly and implicitly recognised Spanish rights over the Southern territories and ‘ma[de] a variety of undertakings to abstain from sailing to and trading with the Spanish regions of America’.[68]

The preamble of the Treaty of Madrid of 18 July 1670 between Spain and Great Britain states that the agreement aims to ‘settle the differences, repress the piracy, and consolidate the peace between Spain and Great Britain in America’. Article II reads,

There shall be a universal peace, and true and sincere amity, as well in America as in other parts of the world, between the Most Serene kings of Spain and Great Britain, their heirs and successors, and likewise between the kingdoms, states, colonies, forts, cities, provinces, and islands, without any distinction of place, under the jurisdiction of either, and between the peoples and inhabitants of their dominions. This peace and amity shall endure from this day forth and forever, and shall be religiously observed as well on land as on sea and in all waters ...[69]

Moreover, art VIII establishes that ‘[s]ubjects of the King of Great Britain shall on no account direct their commerce or undertake navigation to the ports or places which the Catholic King holds in the said Indies, nor trade in them’.[70] These articles are complemented by art XV, which establishes that ‘[t]he present treaty shall detract nothing from any pre-eminence, right, or dominion of either ally in the American seas, straits, and other waters; but they shall have and retain them in as ample a manner as is their rightful due.’[71] These articles suggest that if Britain has no freedom to navigate in the South Atlantic ocean, it would be impossible for the Crown to possess territories in that part of the ‘New World’.

The relevance of art VII of the Treaty of Madrid of 1670 to understanding the scope of British possession is important. The article states that:

the Most Serene King of Great Britain, his heirs and successors, shall have, hold, and possess forever, with full right of sovereignty, ownership, and possession, all the lands, regions, islands, colonies, and dominions, situated in the West Indies or in any part of America, that the said King of Great Britain and his subjects at present hold and possess; so that neither on that account nor on any other pretext may or should anything ever be further urged, or any controversy begun in future.[72]

From the interpretation of the Treaty of Madrid of 1670, Pinochet de la Barra comments that:

1. Spain keeps in the ‘New World’ all her rights and gives to Great Britain the right to enter these territories, but only to those places in which the British ‘at present hold and possess’, ie, in 1670, at the moment of the signature of the Treaty.

2. Since Great Britain does only ‘hold and possess’ some territories in North and Central America, Spain continues to have rights over South America and Antarctica, in those territories west to the demarcation line.

3. Great Britain accepts in perpetuity the Spanish rights in South America and Antarctica, as it undertakes that neither by reason of this acknowledgment nor ‘any other pretext can or should be encouraged something else, or any controversy started in the future.[73]

The Spanish possession of these territories is even more clearly expressed under art VIII of the Peace Treaty of Utrecht of 13 July 1713:

On the contrary, that the Spanish dominions in the West Indies may be preserved whole and entire, the Queen of Great Britain engages that she will endeavour and give assistance to the Spaniards, that the ancient limits of their dominions in the West Indies be restored, and settled as they stood in the time of the abovesaid Catholic King Charles the Second, if it shall appear that they have in any manner, or under any pretext, been broken into, and lessened in any part.[74]

By ‘ancient limits’ it would be possible to interpret that the Treaty refers to the limits established by the Bulls and the Treaty of Tordesillas.[75] The last treaty that this part will examine is the Treaty of San Lorenzo del Escorial or ‘Nootka Sound Convention’ signed by Great Britain and Spain on 28 October 1790. Article III states

And in order to strengthen the bonds of friendship and to preserve in the future a perfect harmony and good understanding between the two contracting parties, it is agreed that their respective subjects shall not be disturbed or molested either in navigating or carrying on their fisheries in the Pacific Ocean or in the South Seas, or in landing on the coasts of those seas in places not already occupied, for the purpose of carrying on their commerce with the natives of the country or of making establishments there; the whole subject, nevertheless, to the restrictions and provisions which shall be specified in the three following articles.[76]

Of the following three articles, art VI is the most relevant. The article states:

It is further agreed, with respect to the Eastern and Western coasts of South America, and to the islands adjacent, that no settlement shall be formed hereafter, by the respective subjects, in such parts of those coasts as are situated to the South of those parts of the same coasts, and of the islands adjacent, which are already occupied by Spain: provided that the said respective subjects shall retain the liberty of landing on the coasts and islands so situated for the purposes of their fishery, and of erecting thereon huts, and other temporary buildings, serving only for those purposes.[77]

Great Britain was prevented from contesting Spanish sovereignty and from occupying any part of South America. This clearly not only reaffirms the prohibition of navigation and fishing, but also the prohibition of establishing settlements on the coasts and islands already occupied by Spain. Goebel states that the practical effect of the Nootka Sound Convention

was to open the seas to the British only for purposes of navigation. The islands surrounding Tierra del Fuego and further south, such as South Georgia[s], were the only places, however, where the British were allowed to land, and this temporarily.[78]

Great Britain could not claim any land south of Tierra del Fuego, such as South Georgias or South Orkney.[79]

Kohen and Rodriguez comment that:

[t]here are similarities to the [PCIJ]’s interpretation of the ‘Ihlen declaration’ with respect to Eastern Greenland, except that in 1790 there was no doubt as to the conventional nature of the obligation undertaken by Great Britain: ‘It follows that, as a result of the undertaking involved in the Ihlen declaration of 22nd July 1919, Norway is under an obligation to refrain from contesting Danish sovereignty over Greenland as a whole, and a fortiori to refrain from occupying a part of Greenland’.[80]

From the analysis of the above treaties, there is a strong argument that by 1810, the year of Argentina’s succession to Spain’s rights, the ‘South American Antarctic’ territory could not be considered as terra nullius. There is also a strong argument that the British Crown recognised that the Spanish Crown was in possession of the mentioned territories and was prohibited from occupying and claiming sovereignty over them. In addition, this section has introduced evidence of the Spanish effectivités in the ‘South American Antarctic’.

After becoming independent from Spain in 1810,[81] Argentina inherited the territory belonging to the Spanish Crown on the basis of the administrative divisions existing at the time. The Argentine succession to Spain’s territories was consistent with the widely recognised rule of international law uti possidetis juris. In the Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso/Republic of Mali), the ICJ states that the term uti possidetis (juris) refers to the presumption that the boundaries of a new state follow those that existed under the previous (usually colonial) regime and states that ‘although this principle was invoked for the first time in Spanish America, it is not a rule pertaining solely to one specific system of international law ... It is a principle of general scope’.[82] Moreover, the Legal Opinion of the Arbitration Commission of the Conference on Yugoslavia concluded that uti possidetis juris applies as a rule and by default when there is no agreement between the parties under dispute.[83] From the evolution and legal practice, it is difficult to escape from the conclusion that uti possidetis juris most probably applies as a rule in future cases of succession of states and there is no argument contradicting the potential application of this principle in the context of Antarctica.

Regarding the application of the uti possidetis juris in newly independent states in Central America, in Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Dispute (El Salvador v Honduras), the Chamber of the ICJ states that:

The Chamber has no doubt that the starting-point for the determination of sovereignty over the islands must be the uti possidetis juris of 1821. The islands of the Gulf of Fonseca were discovered in 1522 by Spain and remained under the sovereignty of the Spanish Crown for three centuries. When the Central American States became independent in 1821, none of the islands were terra nullius; sovereignty over the islands could not therefore be acquired by occupation of territory.[84]

As Kohen and Rodriguez explain, the uti possidetis principle also reinforced the notion that no terra nullius ‘existed in Latin America as a consequence of the process of independence from European colonisation’.[85]

By general principles of the succession of states, the Antarctic territory that was part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata became part of the territory of the ‘Provincias Unidas del Rio de la Plata’ (today Argentina), which throughout its independent life as a state has continued to exercise and perfect the right received from his predecessor.[86] With the evolution of navigation, these territories were able to be reached by the newly formed states. As soon as Argentina became an independent State, it dedicated itself to maintaining and perfecting its effective occupation in Antarctica through constant activities such as administrative measures, scientific activities, official expeditions and permanent establishments. Mentioning every act would exceed the limits of this paper, but Argentina has in multiple ways underlined its claims in Antarctica by periodically performing acts intended to validate administration of its polar territory. For instance, in 1815, Guillermo Brown, an Irish-Argentine admiral serving in the Provincias Unidas del Rio de la Plata, launched a campaign to harass the Spanish fleet in the Pacific Ocean. When rounding Cape Horn aboard the Hercules and Trinidad, strong winds pushed them beyond the parallel 65°S.[87] At the end of the 18th century, the port of Buenos Aires became a centre for Antarctic sealing vessels. The Argentine government granted the first concessions to the Argentine businessman Juan Pedro Aguirre for hunting seals in Antarctica in 1818.[88] In 1829, the Government of Buenos Aires enacted a decree establishing the creation of a Political and Military Commandment of the Malvinas. Under this decree, the newly established Commandment had the obligation of ‘protection and conservation of the fauna in the islands adjacent to the Cape Horn’, in other words, the Antarctic islands.[89] The first official Argentinean Antarctic expedition (the so-called ‘Italo-Argentina’ expedition) was organised in 1881–2,[90] and in 1902, José María Sobral (an Argentine military scientist) spent two seasons with the Nordenskiöld’s Swedish Antarctic Expedition. This expedition was supported and later rescued by the Argentine vessel Uruguay, after their ship, the Antarctic, was crushed in the ice and sank in 1903.[91]

Argentine effectivités are also supported by the fact that Argentina has maintained its physical presence in Antarctica for more than 115 years. In 1904, Argentina established the first permanently inhabited research base in Antarctica for more than 40 years in the South Orkneys (Orcadas del Sur). The base included the first meteorological observation post on the Antarctic continent, with postal facilities, which Argentina has kept operating until the present day. This observatory became known as ‘Base Orcadas’, the oldest existing base located south of 60°S.[92]

Also, in 1904, Argentina authorised the establishment of the Compañía Argentina de Pesca, a company for the purpose of the industrialisation of whaling from South Georgias. This was considered the beginning of the modern exploitation of whaling in the Southern Ocean. From that time, the Argentine navy not only assessed the scientific data coming from the Orcadas base but also supported the whaling factory in South Georgias.[93] In 1906, the President of Argentina by decree designated a commissioner for the South Orkney Islands and one for Wandel Island (or Booth Island) and adjacent territories.[94]

These acts show that the ‘Argentine Antarctica’ was already considered an integral part of Argentinian territory by 1906. That is why, after the Argentine protest against the adoption of several presidential decrees regarding Antarctic activities by Chile,[95] from 1906 to 1908, Argentina and Chile initiated a negotiation process to settle the delimitation of their Antarctic claims.[96] Although an agreement was not reached between both South American countries, these negotiations prove that by 1906, Argentina and Chile were already discussing the delimitation of territories that they already considered to be under their sovereignty.

On 14 February 1927, Argentina communicated to the International Bureau of the Universal Postal Union that the ‘Argentine Antarctica’ is considered an integral part of Argentinian territory. The note states that:

Argentine territorial jurisdiction extends de jure and de facto over the continental surface[,] territorial sea and islands situated off the maritime coast, to a portion of the Islands of Tierra del Fuego, the Archipelago of Staten, New Year, South Georgia, South Orkneys and polar territories not delimited.

De jure but not de facto, owing to the occupation maintained by Great Britain, the Falklands Archipelago also belongs to it.[97]

In accordance with this note, the Argentine territorial jurisdiction extends de jure and de facto to part of the ‘South American Antarctic’ (which had not been delimited yet at that time).

The Argentine National Antarctic Commission was created in 1939 and from 1941 has sent annual expeditions which allowed the development of activities in Antarctica, in particular scientific research. On 17 January 1951, the Argentine Antarctic Institute was created, which was among the first bodies in the world exclusively dedicated to Antarctic research. Argentina’s engagement in Antarctic scientific research has been always substantial. This is proved by its work within the framework of the 1957–58 International Geophysical Year (‘IGY’).

Argentine activities in Antarctica were not free of controversy, particularly in relation to the UK.[98] The escalated tensions between these two states were one of the key drivers that led to the call for the international conference that concluded with the adoption of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959. However, the entry into force of the Treaty did not stop Argentine policies designed to strengthen its sovereignty claim in Antarctica. Since 1961, Argentina has not only increased its Antarctic scientific research activities but also the amount of administrative, jurisdictional and government acts for its Antarctic sector. For instance, the expedition ‘Operación 90’ was an over-snow expedition to the South Pole in 1965. The expedition not only allowed Argentina to carry out scientific and technical observations, including geological, gravimetric and meteorological work, but also showed Argentina’s capacity to reach all corners of its Antarctic sector. Moreover, Argentine acts include a substantial number of laws governing its Antarctic sector and, in Antarctica, the establishment of a school (the ‘Escuela Provincial Nº 38 Presidente Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín’ in the vicinity of Esperanza Base). Even pregnant Argentinian women have given birth to children in ‘Argentine Antarctica’ — the first documented person born on the continent of Antarctica was Emilio Marcos Palma, born on 7 January 1978 in Esperanza Base.[99]

In summary, there is a strong argument that the ‘South American Antarctic’ was originally an integral part of the Spanish colony and, later, a part of Argentina due to succession rights and effective occupation of those territories. When the UK made its first formal claim to Antarctic territories in the 1908 and 1917 Letters Patent announcing British sovereignty over the so-called Falkland Islands Dependencies,[100] there is significant doubt that those territories were terra nullius and therefore able to be acquired by occupation. These findings cast significant doubt over the validity of the U K’s territorial claim, in so far as the part that overlaps with Argentine Antarctica.

The Chilean titles to the Chilean Antarctic Territory (Territorio Antártico Chileno) share several similarities with the Argentine claim. Chile also inherited part of the ‘South American Antarctic’ by the succession of Spanish rights. In Chile’s view, the Antarctic territories that were part of the Spanish colony were under the administration of the Captaincy General of Chile. By virtue of the uti possidetis juris, these territories became part of the newly independent Chile in 1810. Chile also argues that has effectively occupied this territory by acts of exploration, scientific endeavour, occupation and administration.

By Supreme Decree No 1747 of 6 November 1940, Chile established that ‘the meridians 53°W and 90°W of Greenwich constituted the boundaries of its Antarctic territory’.[101] The Argentine and Chilean Antarctic sectors overlap between the meridians 53° W and 74° W. These two states have recognised each other’s claims, but have not yet settled delimitation of the boundary. As it was mentioned, the first attempt to settle this issue by Argentina and Chile occurred between 1906–8; however, this was not successful. In 1940, after the Argentinean protests against the Chilean Supreme Decree No 1747, the negotiation was resumed. The discussion continued for several years, again without success. In 1947, Argentina and Chile agreed on a ‘Joint Declaration’ stating that the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of Argentina and Chile:

have agreed, in view of their desire to carry out a friendly policy regarding the determination of the frontiers of both countries in the Antarctic region, to declare that, being convinced of the unquestionable rights of Argentina and Chile over the South American Antarctic, both Governments favour the execution of a harmonious plan of action for the better scientific knowledge of the Antarctic zone by means of explorations and technical investigations; that, at the same time, they consider desirable a joint study of matters relating to the exploitation of the wealth of this region; and that it is their desire to arrive as soon as possible at the conclusion of a Treaty between Argentina and Chile, regarding the demarcation of boundaries in the South American Antarctic.[102]

The following year, Argentina and Chile signed another ‘Joint declaration’ (known as the ‘La Rosa-Vergara Donoso Declaration on the Antarctic’) stating that until a settlement is reached by amicable agreement regarding the boundary limits in the adjacent Antarctic territories of the Argentine Republic and Chile, both Governments ‘will act in mutual agreement in the protection and legal defence of their rights in the South-American Antarctic, lying between the meridians of 25° and 90° West of Greenwich, within the territories of which the Argentine Republic and Chile are recognised as having unquestionable sovereign rights’.[103] Despite several negotiations between the two South American States, an agreement regarding their boundary limits in Antarctica has never been reached. The entry into force of the Antarctic Treaty made the agreement less urgent.

The above analysis suggests that Argentina has strong arguments for valid titles to part of West Antarctica, based on inheritance from Spain and its subsequent effective occupation. It follows that the British claim made to these areas of Antarctica in 1908 could be disputed as these areas were likely not terra nullius at that time. But the further question is what these findings mean for the other claimant states, in particular for Australia, since its two sectors of Antarctic territory in East Antarctica were transferred from the UK in 1933, with effect from 1936. To answer this question, it is necessary to analyse firstly the legal basis of Australian territorial titles to the AAT.

British expeditions (with the active participation of Australia) to discover and annex territories in East Antarctica for the Crown under the command of Captain Ross can be traced to the middle of the 19th century.[104] Robert Falcon Scott led two exploring expeditions to the Antarctic region, the Discovery Expedition of 1901–4 and the Terra Nova Expedition of 1911–13, which were often characterised as part of a romantic, heroic (and ultimately tragic) race against the rival Norwegian expedition to discover the South Pole.[105]

From the 1880s, the Australian scientific community made attempts to organise an Australian expedition to Antarctica.[106] The first Australian Antarctic expedition (the ‘Australasian Antarctic Expedition’), under the leadership of Sir Douglas Mawson, took place between 1911–14. Despite King George V Land and Queen Mary Land being claimed for the British Crown, Mawson was well aware of the significance of this expedition with respect to other potential claims in the area to the immediate south of Australia.[107] After the 1926 Imperial Conference, Australia began to take a more active interest in asserting an Antarctic claim.[108] The 1926 Imperial Conference decided that Australia should make a claim for the British Commonwealth and Mawson was authorised to organise the expedition to do it. It required Crown authorisation as Australia, at the time, did not have its own foreign affairs powers or powers to independently acquire territory. The British, Australian, and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition of 1929–31, also under the leadership of Mawson, allowed the British Commonwealth to claim further territory in East Antarctica, which along with the earlier claims of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, amounting to 42 per cent of the Antarctic continent.[109]

The Australian Government was keen for these Commonwealth claimed areas to be formally placed under Australian control. In 1933, a British Imperial Order was issued which provided the constitutional means to transfer to Australia ‘all the islands and territories, other than Adelie Land, situated south of the 60th degree south latitude and lying between the 160th degree east longitude and the 45th degree east longitude’.[110] This came into force by Proclamation of 24 August 1936. The claim excluded Adélie Land, the boundaries of which had not been negotiated, which was subject to prior discovery in 1840 by Jules-Sebastien-Cesar Dumont d’Urville. The AAT was finally delimited when the borders with the French-claimed’ Adelie Land’ were fixed definitively after negotiations with France in 1938. However, the outbreak of WWII in 1939 prevented further Australian activities in Antarctica.

The AAT is administered by the Australian Antarctic Division on behalf of the Government of Australia, the relevant legislation having been assigned to the Environment Minister through the Administrative Arrangements Order. Since 1936, Australia’s legislative and Treaty practices constitute manifestations of sovereignty in Antarctica. Australia’s interest and will to act as sovereign are demonstrated by a variety of acts such as enacting laws applying to the AAT, sending expeditions, establishing research bases and mapping its territorial claim,[111] Australia has arguably demonstrated effective occupation of its claimed areas of East Antarctica.

In 1947, Great Britain transferred the Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands to Australia. The same year, the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (‘ANARE’) established the first Australian sub-Antarctic research station at Heard Island. Australia established the second research station in 1948 on Macquarie Island, which is administratively part of the Australian state of Tasmania. In 1954, Australia inaugurated the first permanent base on the Antarctic continent at Mawson, the oldest continually operating station south of the Antarctic Circle and thus sharing with Argentina the fact of being pioneering occupants of Antarctic territory. Davis Station was established in 1957, and in 1959 Australia took over administrative control of the US’ Wilkes Station, which was previously built by the US for the International Geophysical Year (1957–8). Wilkes was later replaced in 1969 by the nearby Australian Casey Station.

Since the AAT was annexed to Australian territory with effect from 1936, Australia has arguably perfected its sovereignty rights over these parts of East Antarctica. Like Argentina, Australia enacted various domestic laws that applied to Antarctica, such as the Whaling Act 1935 (Cth). With the adoption of the Australian Antarctic Territory Act 1954 (Cth), Australia provided a more complete legal regime for its Antarctic sector. In accordance with the Australian Antarctic Territory Act 1954 (Cth), the civil law of the Australian Capital Territory and the criminal laws of the Jervis Bay Territory were applied to the AAT.[112] The courts of the Australian Capital Territory exercise jurisdiction over the AAT.[113]

ANARE allowed the development of Australian scientific research and consolidated Australia as an important participant of the 1957–8 IGY. Since the 1959 Antarctic Treaty entered into force in 1961, Australia has increased its presence in Antarctica, not only by scientific and exploratory activities within the AAT but also with strong Antarctic policies and active participation within the Antarctic institutions. Australia has exercised legal jurisdiction over the AAT through domestic legislation, for instance, by the implementation of the Antarctic Treaty (Environment Protection) Act 1980,[114] application of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 in the AAT, and the making of multiple ordinances.[115]

In accordance with the provisions of art IV of the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, the territorial rights of Australia over the AAT have not been diminished, and it has probably taken as proactive a position as it could to demonstrate its claim, including in 2004 submitting Antarctic data to the CLCS in accordance with its rights under the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea as an Antarctic coastal state.[116] In the hypothetical case of termination of the Treaty, and territorial disagreements vis a vis parties to the Antarctic Treaty would most likely be considered under the situation prevailing at the time of entry into force of the Treaty in 1961. Based on their long-standing scientific presence within the AAT, the only parties to the Treaty that could only feasibly make any counter-claims to Australian sovereignty are the US and Russia which, like Australia, had established stations in East Antarctica during the IGY.[117] Nevertheless, for any other State that is not a party to the Antarctic Treaty, any counter-claim of sovereignty to the area of the AAT would be very difficult to sustain, since the factors to be considered in weighing respective sovereignty claims could probably only include the substantial activities carried out by Australia in the AAT from entry into force of the Treaty in 1961 to date.

In summary, the Australian titles to the AAT are based on the effective occupation of a terra nullius Antarctic territory discovered during several British and Australian expeditions. This Antarctic territory was claimed under the authority of the British Empire and transferred to Australian control in the mid-1930s. Two Antarctic sectors were thus incorporated into Australia’s territory, giving Australia a strong argument that its sovereignty over the AAT was perfected.

It is arguable that both Argentina and Australia, after possessing their territories, one by the administrative transfer of Commonwealth territory, the other by inheriting Spanish domains, have effectively occupied their Antarctic sectors as required by international law on a continent with unique characteristics. Manifestations of territorial sovereignty may assume different forms according to conditions of time and place. As a rule, the international legal significance of acts and facts must be ascertained in accordance with the system of international law existing at the moment of their occurrence. Both Argentina and Australia appear proud of their Antarctic heritage and justifiably confident of their territorial claims.[118] While confidence alone does not afford Argentina or Australia titles to territory, it would underpin a willingness to defend their interests on more conventional grounds.

If we accept that the Bull Inter Caetera of 1493 and subsequent treaties legally gave Spain titles over Antarctica, which Great Britain later recognised, and that Argentina then inherited and effectively occupied those territories, the ‘Argentine Antarctic Sector’ could not be considered as terra nullius at the time the UK made its first formal claim to Antarctica in 1908. Further, from the interpretation of the Bulls and subsequent treaties, there is no evidence that other parts of the Antarctic continent have been awarded and later recognised as the territory of any State other than Spain.[119] Thus, the eastern limit of the Argentine inherited sector cannot exceed the meridian 25° W to the East and the meridian 74° W to the West. Even if we understand that under similar facts, the Chilean claim (analysis of which exceeds the scope of this article) is also valid, the ‘South American Antarctic’ would only comprise the sector between the meridian 25° W to 90° W. It follows that the remainder of the Antarctic continent, including East Antarctica, could be considered as terra nullius when Great Britain made its 1908 claim. There is a strong argument that the AAT was capable of being acquired by the British Crown as a terra nullius area by discovery and occupation. It also follows that although the Argentinian and Australian claims have different legal basis, there is no overt legal conflict between them. Any future outcome that determined that the Argentine title to Antarctic territory is legally valid would not, in our view, undermine or weaken the Australian sovereignty claim to the AAT.

The Antarctic Treaty 1959 recently celebrated its sixtieth anniversary of coming into force and has shown significant adaptability in addressing issues relevant to the region. The Treaty has successfully managed politically disruptive arguments regarding sovereignty over the continent and spawned new treaties governing conservation of marine resources and protection of the Antarctic environment. Some elements of the ATS are showing signs of pressure, particularly over issues such as marine protected areas,[120] but there are no current indications that any state is planning to withdraw from the Antarctic Treaty, or any broader moves for termination the treaty. However, Antarctic law commentators have raised the possibility of a state (or states) withdrawing from the Antarctic Treaty, and/or even termination of the Antarctic Treaty, particularly in the period leading up to a possible review conference of the Environmental Protocol in 2048.[121] In the event of any future termination of the Antarctic Treaty, or withdrawal by a State that subsequently seeks to make a claim to sovereignty, or even a claim to sovereignty by a non-party State, the rules of international law governing the acquisition of territory would apply to the Antarctic continent. The findings of this article are of particular importance in this context, as they indicate that international law would likely allow for the co-existence of both the Argentine and Australian titles to territory in Antarctica.

The Antarctic Treaty has provided a successful governance framework for the area below 60° S for the last six decades as an area for peaceful use and scientific investigation. We believe that there are no significant signs of weakening of support for the Antarctic Treaty and that it is likely to continue to govern the region into the future. The discussion of the Argentine and Australian sovereignty claims in this article is not intended to suggest that there is likely to be any immediate or short-term escalation of the assertion of sovereignty rights in Antarctica. Having said this, we are of the view that the seven sovereignty claims made over Antarctic territory have played a significant role in the shaping of the ATS and will likely continue to do so. If in the future a state chose to withdraw from the Antarctic Treaty to explore resource extraction in the region, or if a third-party state entered the region with similar plans, the legal basis of the territorial claims in Antarctica, and their legal relationship, will again become a highly salient issue. We therefore believe it is important to properly understand the legal basis of the respective sovereignty claims, given their influence on shaping the ATS, and its likely importance if it were to ever unravel.

The above analysis shows that the legal basis of the Argentine territorial claim in West Antarctica relies upon pre-existing Papal Bulls, international treaties recognising Spanish sovereignty over part of Antarctica and activities by both the Spanish Crown and the Argentine government that significantly predate the UK’s claim to Antarctic Territory in the area in 1908. Spain understood it was the recipient of rights to sovereignty from these Papal Bulls over part of West Antarctica, and such rights were implicitly and explicitly recognised by the British Empire. Argentina subsequently inherited these rights to sovereignty and has subsequently strengthened its territorial claims through the effective occupation of these areas. The UK’s claim in 1908 relies on this area of West Antarctica as having been terra nullius at the time. However, it appears there is strong evidence that this area was not terra nullius at that time but, rather, it was Argentinian territory. It is not necessary for us to offer a determinative view on the merits of the overlapping Argentine and UK claims in West Antarctica to draw conclusions on whether the Australian claim in East Antarctica is affected by this issue. Although the Australian territorial claims in East Antarctica rely upon a transfer of control over two sectors of territory from the UK to Australia in 1933 (which became effective in 1936), these areas were not under effective occupation or subject to sovereignty claims by any another state, so there can be little doubt they were terra nullius areas when claimed by the British Crown. We therefore find that regardless of the outcome of the territorial dispute between Argentina and the UK, the legal basis of the Australian territorial claim in East Antarctica is unlikely to be affected. We conclude that the Argentine and Australian territorial claims in Antarctica therefore have no overt legal conflict and can legally co-exist.

* Bruno Arpi is a PhD candidate at the Faculty of Law and the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania.

⁑ Jeffrey McGee is an Associate Professor at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) and the Faculty of Law at the University of Tasmania.

† Andrew Jackson has recently completed a placement as a post-doctoral research fellow at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania. This followed previous employment with the Australian Government as a senior policy adviser during a period of major developments in Antarctic law and policy.

‡ Indi Hodgson-Johnston is an Adjunct Senior Researcher at the Centre for Oceans and Cryosphere, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania. Funding for this research was provided under Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP[1]90101214 titled ‘Geopolitical Change and the Antarctic Treaty System’. The authors thank the insightful comments from Prof Shirley Scott and Prof Marcus Haward. Bruno Arpi would also like to acknowledge the generous comments and suggestions from Hernán Botta and Alberto Monsanto to this paper. Thanks are also due to the Editors of this issue and two anonymous reviewers of this paper for their useful suggestions. Any errors or omissions of course remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

[1] The Antarctic Treaty, opened for signature 1 December 1959, 402 UNTS 71 (entered into force 23 June 1961) (‘Antarctic Treaty’).

[2] The characterisation of this as the ‘Antarctic Problem’ pre-dates the Antarctic Treaty. See EW Hunter Christie, The Antarctic Problem: An Historical and Political Study (George Allen & Unwin, 1951) 286–300.

[3] Antarctic Treaty (n 1) art IV.

[4] FM Auburn, Antarctic Law and Politics (C Hurst, 1982) 52, 55.

[5] ‘Joint Declaration of Argentina and Chile Concerning the South American Antarctic on 12 July 1947’ (12 July 1947) <https://sparc.utas.edu.au/index.php/joint-declaration-of-argentina-and-chile-concerning-the-south-american-antarctic>, archived at <https://perma.cc/4WXS-7LBX> (‘Joint Declaration of Argentina and Chile of 1947’).

[6] There is possibly a small anomaly with Norway which, on the basis of Amundsen’s discovery of the South Pole, included the ‘south polar plateau’ and hence has the potential to encroach on other claims which terminate at the pole. Other claimants appear to remain silent on the issue. Norway does not seem to press the point and in 2015 appeared to accept that its claim complied with the ‘sector principle’: Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norwegian Interests and Policy in the Antarctic (White Paper No 32, 12 June 2015) 17 <https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/cef2a67e958849689aa7e89341159f29/en-gb/pdfs/stm201420150032000engpdfs.pdf>, archived at <https://perma.cc/2X7U-TSVV>.

[7] The relevance of the recognition of the Antarctic claims in international law has been recently addressed by Shirley Scott: see generally Shirley V Scott, ‘The Irrelevance of Non-Recognition to Australia’s Antarctic Territory Title’ (2021) 70(2) International and Comparative Law Quarterly 491.

[8] See generally Alan D Hemmings, Klaus Dodds and Peder Roberts, ‘Introduction: The Politics of Antarctica’ in Klaus Dodds, Alan D Hemmings and Peder Roberts (eds), Handbook on the Politics of Antarctica (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017) 1; Alejandra Mancilla, ‘Decolonising Antarctica’ in Dawid Bunikowski and Alan D Hemmings (eds), Philosophies of Polar Law (Routledge, 2021) 49.

[9] Antarctic Treaty (n 1) art IV.

[10] Donald R Rothwell, The Polar Regions and the Development of International law (Cambridge University Press, 1996) 77–8.

[11] Karen N Scott, ‘Managing Sovereignty and Jurisdictional Disputes in the Antarctic: The Next Fifty Years’ (2010) 20(1) Yearbook of International Environmental Law 3, 5.

[12] See generally Alan D Hemmings and Tim Stephens, ‘The Extended Continental Shelves of Sub-Antarctic Islands: Implications for Antarctic Governance’ (2010) 46(4) Polar Record 312.

[13] The ‘sector principle’ had its origins in the Arctic and its application in the Antarctic region presupposes that the claimant states delimit their claims by using lateral boundaries converging along degrees of longitude to the geographic South Pole and terminate their northern boundaries at the coast: Beau Riffenburgh (ed), Encyclopaedia of the Antarctic (Taylor and Francis, 2007) 445. See also Patrick T Bergin, ‘Antarctica, the Antarctic Treaty Regime, and Legal and Geopolitical Implications of Natural Resource Exploration and Exploitation’ (1988) 4(1) Florida International Law Journal 1, 12.

[14] Shirley V Scott, ‘Universalism and Title to Territory in Antarctica’ (1997) 66(1) Nordic Journal of International Law 33, 40.

[15] Shirley Scott, ‘The Geopolitical Organization of Antarctica, 1900–1961: The Case for a Revisionist Analysis’ (1995) 11 Australian Journal of Law and Society 113, 11636. (‘The Geopolitical Organization of Antarctica’).

[16] The discovery of Antarctica is disputed. The British claim that in 1819 Smith was the first explorer to observe Antarctica; Russians attribute it to Bellingshausen in the same year; Argentineans give it to Brown in 1815, or hunters in 1817; and there are even stories that Gabriel de Castilla (Spanish explorer and navigator), penetrated to a latitude of 64° S south of Drake Passage in 1603: Christopher C Joyner, Antarctica and the Law of the Sea (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1992) 4; Alfonso Luis Quaranta, El Sexto Continente: Apuntes para el estudio de La Antártida Argentina (Editorial Crespillo, 1950) 186; Jorge Berguño, ‘Un Enigma de la Historia Antártica: El Descubrimiento de las Islas Shetland del Sur’ (1991) 1(1) Revista Española del Pacífico 129.

[17] Island of Palmas (Netherlands v United States of America) (Award) (1928) 2 RIAA 829, 846 (‘Island of Palmas Case’).

[18] Roberto E Guyer, ‘The Antarctic System’ (1973) 139 Collected Courses of the Hague Academy of International Law 151, 160.

[19] There is no generally accepted definition of the ‘South American Antarctic’, or ‘American Antarctic’. Division of the Antarctic into segments is frequent. While some authors divide Antarctica into two major areas (West Antarctica, and East Antarctica), others have applied the ‘theory of the quadrants’. In accordance with this theory, Antarctica can be divided into four equal quadrants (West 0°- 90°, 90°-180°; East 0°- 90° and 90°- 180°) that are named ‘South American’, ‘Pacific’, ‘African’ and ‘Australian’ respectively: Quaranta (n 16) 39–42. American states have agreed to the scope of the ‘South American Antarctic’ under the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance of 1947 (also known as the ‘Rio Treaty’): Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance and Final Act of the Inter-American Conference for the Maintenance of Continental Peace and Security, opened for signature 2 September 1947, 21 UNTS 77 (entered into force 3 December 1948) art 4. This defence agreement between most of the American states includes the Antarctic region between the meridians 24° and 90° W. For the purpose of the present Article, the term ‘South American Antarctica’ will be used as the sector comprised by meridians 25° W and 90° W as it was established by the Argentinian and Chilean Joint Declaration: ‘Joint Declaration of Argentina and Chile of 1948’ (n 5).

[20] Robert D Hayton, ‘The “American” Antarctic’ (1956) 50(3) American Journal of International Law 583, 590.

[21] Scott, ‘The Geopolitical Organization of Antarctica’ (n 15) 117.

[22] Guyer argues that the distinction between these two approaches (the European and the South American) is not only theoretical but also philosophical: Guyer (n 18) 160.

[23] The first official British claim to an Antarctic territory was made by the Letter Patent of 1908 (later modified by the Letter Patent of 1917). Claims by New Zealand and Australia were made in 1923 and 1933 respectively. France made its claims to part of Antarctica in 1924 and Norway subsequently in 1928: see FM Auburn, ‘The White Desert’ (1970) 19(2) International and Comparative Law Quarterly 229, 229 n 8, 231, 244.

[24] Antarctica Case (United Kingdom v Argentina) (Order on 16 March 1956) [1956] ICJ Rep 12; Antarctica Case (United Kingdom v Chile) (Order on 16 March 1956) [1956] ICJ Rep 15.

[25] See, eg, Gillian D Triggs, International Law and Australian Sovereignty in Antarctica (Legal Books, 1986); James Crawford and Donald R Rothwell, ‘Legal Issues Confronting Australia’s Antarctica’ [1990] AUYrBkIntLaw 2; (1990) 13 Australian Year Book of International Law 53; Donald R Rothwell and Andrew Jackson, ‘Sovereignty’ in Marcus Haward and Tom Griffiths (eds), Australia and the Antarctic Treaty System: 50 Years of Influence (UNSW Press, 2011) 48.

[26] See, eg, Juan Carlos Rodríguez, La República Argentina y las adquisiciones territoriales en el continente Antártico (Imprenta Caporaletti, 1941); Juan C Puig, La Antártida Argentina ante el Derecho (Roque Depalma, 1960); Jorge Alberto Fraga, El Mar y la Antártida en la Geopolitica Argentina (Instituto de Publicaciones Navales, 1980).

[27] Antarctic Treaty (n 1) art IV.

[28] For a review of the potential of mining taking place in antarctica in a contemporary context, see Karen N Scott, ‘Ice and Mineral Resources: Regulatory Challenges of Commercial Exploitation’ in Daniela Liggett et al (eds), Exploring the Last Continent: An Introduction to Antarctica (Springer, 2015) 487.

[29] An example of ‘third party state’ activity in Antarctica is Pakistan, which carried out a national scientific expedition in the Norwegian-claimed area of Antarctica between 1991–93. The expedition included the construction of small huts, even though it was not a party to the Antarctic Treaty: see Riifenburgh (n 13) 661. Pakistan eventually joined the Antarctic Treaty in 2012.

[30] See generally Klaus Dodds, Geopolitics in Antarctica: Views from the Southern Oceanic Rim (John Wiley & Sons, 1997).

[31] As we understand it, the Antarctic could be considered a territory under international law and therefore capable of being subject to territorial sovereignty.

[32] RY Jennings, The Acquisition of Territory in International Law (Manchester University Press, 1963) 4.