Melbourne Journal of International Law

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne Journal of International Law |

|

REVIEW ESSAYS

Book Reviews

CONSTRUCTIVIST CONSTRUCTIONS OF INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE REGIMES — THE SOUTHEAST ASIAN CONTEXT

ENVIRONMENTAL COOPERATION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA: ASEAN’S REGIME FOR TRANSBOUNDARY HAZE POLLUTION BY PARUEDEE NGUITRAGOOL, (ROUTLEDGE, 2011) 191 PAGES. PRICE US$54.95 (PAPERBACK). ISBN 9781138785175.

Positive international legal theory is a highly contested intellectual territory, where competing scientific paradigms unrealistically seek to achieve a position of total dominance. This analytically rigorous and carefully researched study marshals valuable empirical evidence to lend direct support to one of them, constructivism, and indirectly to closely related schools of thought, such as transnational legal process theory. However, the factual foundation methodically built suggests that the explanatory power of this particular conceptual scheme is rather limited and that it cannot shed adequate light on formal and informal international cooperation, as witnessed in a specific Association of Southeast Asian Nations environmental context, without being effectively coupled with polar opposites in the rationalist space.

CONTENTS

International cooperation — potentially, albeit rarely, culminating in international integration — takes place at the bilateral, regional and global level. In terms of aggregate welfare, the greatest benefits derived from the ongoing yet inevitably uneven process occur when it is all-encompassing. However, achieving progress often proves to be a challenge as the number of participants grows, diversity of interests and preferences increases and negotiation costs rise. In the international trade domain, characterised by a relatively high degree of cooperation, this pattern can be said to have been observed in the post-Uruguay Round era.

The corollary is that momentum, in terms of the systematic pursuit of concrete goals and their implementation, has shifted towards establishing, furthering and solidifying bilateral and regional links. Again, from the perspective of aggregate welfare, the more broad-based, regional pattern holds greater promise than the bilateral variant. The proliferation of regional groupings in all parts of the

world — Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East and the Americas (Central, North and South) — should thus be viewed as a largely positive phenomenon, albeit unavoidably not one without costs (notably labour dislocation, reduced global trade and trade diversion).

However, as matters stand, few of these entities have evolved to a point where they display a meaningful degree of structural and functional coherence and cohesion — although this does not prevent them from claiming attributes akin to those of full-fledged free trade areas, customs unions and common markets. This is particularly true of regional groupings in the developing world, most of which have not been entirely successful in fulfilling their stated aspirations and erecting a viable joint institutional framework as observed in Europe (post ‘Great Recession’ strains notwithstanding) and North America.

The implication is that students of international law and international relations cannot readily venture beyond the European Union (‘EU’) and the North American Free Trade Area in exploring the organisational underpinnings and workings of regional forms of international cooperation. This constitutes a rather small sample for generating far-reaching explanatory insights regarding the experience accumulated in that domain and evaluating it in a multifaceted fashion. A substantial body of knowledge has been built on this crucial but ultimately narrow foundation. Any new addition to the literature that incorporates comprehensively and rigorously empirically-grounded observations pertaining to regional integration which extend beyond the Western Hemisphere is thus clearly welcome.

The book under review comfortably satisfies these criteria. It focuses on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (‘ASEAN’), a regional grouping second only to the EU in terms of its geographic scope and potential depth of integration, but one that does not attract adequate scholarly attention other than in Southeast Asia. It does so in the specific context of this body’s responses to transboundary haze pollution, a subject that allows a proper blending of legal and social science approaches, or the adoption of a genuinely interdisciplinary perspective, an element not featuring prominently in previous equally impressive studies on ASEAN and its evolution.[1] The book has descriptive and diagnostic dimensions, is factually and theoretically rich, and places the conceptual and empirical edifice in a sufficiently broad historical and policy setting.

Besides the obligatory introduction and conclusion, the book consists of five parts: a snapshot of ASEAN regionalism and politics of the environment in the area; an account of the emergence of the ASEAN transboundary haze pollution governance regime; a survey of the origins and consequences of forest burning, in response to which regional environmental cooperation has apparently crystallised; a dissection of the regime in its local and international context; and an elaborate assessment of the system’s effects, qualifying as moderately favourable, which includes a suitably modest prescriptive component.

Southeast Asia is appropriately portrayed as a ‘region on fire’ because of the large-scale forest burning and the acute haze pollution to which it gives rise. This widespread activity, and the damage it wreaks, is a decades-old source of ecological hazards, but there has been a marked deterioration in the past twenty years or so. The problem largely emanates from the tendency of two major, predominantly Indonesian agro industries, palm oil and timber, to clear land by fire rather than resort to more sound environmental practices. The reliance of indigenous farmers on old-style slash-and-burn methods in pursuing similar objectives, aggravated by massive land development projects and

weather-related disruptions such as El Niño, has significantly worsened the situation.

The physical and economic repercussions of such crude and careless exploitation of a scarce and valuable resource have been distinctly negative.

The repercussions have manifested themselves in extensive deforestation;

haze-engendered (principally respiratory, but also cardiovascular and dermatological) diseases, both temporary and chronic (potentially

life-threatening); severe famine, which has caused malnourishment and at times death; enormous harm to biodiversity; and notable acceleration in climate change and global warming. Rather paradoxically, given the nature of the precipitating factors, the economic burden has been immense, not merely due to the serious damage to the environment and human health/life, but also as the result of the adverse impact on industries such as air travel, construction, farming, food, forestry and tourism.

Indonesian society, the primary domain in which these malpractices and traumas have originated, has been adversely affected on all fronts, economic as well as physical. However, in light of its geographical dimensions and magnitude, the problem has had material regional and even international ramifications. Neighbouring countries, particularly Malaysia and Singapore, may have been most heavily exposed, but the fallout has been felt across Southeast Asia, nearby areas and as far as Europe.

The environmental challenges confronting ASEAN are not confined to transboundary haze pollution stemming from forest burning, even though this qualifies as the most prominent. Environmental challenges more generally have been tentatively acknowledged as a set of loosely interconnected policy concerns for as long as the past four decades or so, with signs of basic recognition surfacing soon after the establishment of ASEAN. The 1972 Stockholm United Nations Conference on the Environment may have provided the impetus for incorporating ecological hazards into ASEAN’s strategic agenda, although without decisively propelling them into its epicentre.

The pattern followed in subsequent years has been wave-like, in that policy responses have generally been precipitated by crisis-type eruptions and have otherwise been characterised by substantial pauses. This has reflected a priority structure skewed towards (initially) national security and (latterly) material wellbeing. The preoccupation with economic issues (growth, investment and trade) has deep institutional roots because it has been the product of the tendency of Southeast Asia’s key ‘Developmental States’ to forge enduring and strong alliances with powerful corporate interests.

This is not to suggest that the waves have not risen progressively, at least moderately, or that, worse still, they have simply kept on reverting to their (low) starting point. After all, ASEAN’s development as a broad-based regional organisation has taken place against the backdrop of increasing environmental activism, private and public, on home fronts and beyond (notably in affluent democracies, but modestly and selectively across Southeast Asia), the emergence of politically influential environmental protagonists (eg, the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank) and an ideological reorientation supporting a gradual readjustment of strategic priorities in favour of greater emphasis on ecological preservation. The combination of these complementary forces has steadily shifted ASEAN in a more environmentally-friendly direction, albeit in a hesitant and piecemeal fashion, with the pace accelerating somewhat from the 1990s onwards.

A number of pivotal steps have thus been taken individually/nationally and collectively/regionally to address ecological threats in Southeast Asia in general and those emanating from forest burning in particular. A notable example of a product of joint action is the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution (‘AATHP’),[2] signed by key member states in 2002 and effectuated in the following year. Unlike previous fundamentally similar initiatives, the AATHP is a formal international treaty. As such, it is marked by greater breadth (although it is a moot point to what extent), definitional precision, detail and overall coherence than the elastic and informal policy understandings preceding it. Importantly, owing to its legal status, the AATHP imposes specific obligations on the signatories and requires them to adhere to its provisions.

The author outlines these long-term trends against the background of ASEAN’s evolution from the Declaration constituting an Agreement establishing the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN)[3] in 1967 to the present. This multi-decade period is divided into four distinct phases: the challenging and measured laying of the institutional foundation during the first ten years up to 1976; the consolidation of regional institutions in the face of armed conflicts involving, directly and indirectly, major powers, extending over a decade and a half up to 1992; the strengthening of economic cooperation and security regionalism during the relatively short six-year stage up to 2008; and the current post-ASEAN Charter juncture, characterised by a construction of a regional community.

While this laborious process of institution-building has inevitably been centred on economic and security foundations, environmental issues have begun to loom increasingly large on the organisation’s agenda as it has gained traction and has grown in complexity — with special emphasis being placed on deforestation, forest fires, land degradation, maritime resources and urban pollution. Again, the author identifies four distinct developmental phases: 1977 to mid/late-1980s, featuring a proliferation of dispersed activities and meetings, predominantly informal in nature, and culminating in non-binding declarations and resolutions; up to 2000, when the strategy shifted from conservation to pollution and started to display a more pronounced transnational orientation; up to 2003–4, a brief stage marked by formalisation of processes of cooperation and enhancement of community-wide structures; and the present post-Bali Summit (2003) period, geared towards the formation of a fully integrated socio-cultural regional entity (ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (‘ASCC’)), with the Vientiane Action Programme (VAP) 2004–2010 (‘VAP’),[4] aimed at promoting environmental sustainability for a clean and green ASEAN under the banner of ASCC, as one of its first notable initiatives.

The VAP ushered in a crucial phase in Southeast Asia’s collective endeavour to ensure long-term ecological viability, particularly with respect to its forest resources. The combatting of transboundary haze pollution and the practices responsible for it has been designated as the top priority for the region’s environmental planners. To illustrate the far greater urgency exhibited on this front, the author highlights the organisational scope and potential for prevention and remediation of two bodies established shortly following the adoption of VAP: the ASEAN Wildlife Enforcement Network, a concrete manifestation of the regional effort to implement the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species[5] and the ASEAN-German Regional Forest Programme for Southeast Asia, designed to support the ASEAN Secretariat and ASEAN member countries (‘AMCs’) in their quest for a unified stance inspired by a desire to achieve the harmonisation of national forest policy through resource mobilisation, strategic monitoring and timber certification.[6]

The author illustrates how the broadening and deepening of the ASEAN environmental agenda was influenced, favourably and unfavourably, by AMCs’ inter-state interactions, domestic politics, state-society relations and, interestingly, what could be termed the ‘international politics of the forest’.[7] The latter factor, particularly in the Malaysian context, has been intriguingly reflected in the ever changing definition of the problem of transboundary haze pollution. Originally framed as a product of ‘consumption patterns of Northern consumers’, and involving pressures on Southern countries to embrace inappropriate norms, and thus amounting to ‘eco-imperialism’, it has eventually undergone fundamental readjustment by echoing in many respects Northern/Western concerns and, for the most part, incorporating established international standards pertaining to forest conservation. The book’s principal contribution lies in methodically dissecting this complex transition within a sophisticated analytical framework resting, albeit selectively, on a firm conceptual legal and social science foundation.

Two new–old scientific paradigms provide the inspiration for a rigorous interpretation of what transpired on the forest degradation–preservation front in ASEAN since its inception: the governance regime configuration and constructivism. The former is generally equated with ‘sets of implicit or explicit principles, norms, rules and decision-making procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a given area of international relations’.[8] In this context:

Principles are beliefs of fact, causation and rectitude. Norms are standards of behavior. Rules are specific prescriptions or proscriptions for action.

Decision-making procedures are prevailing practices for making and implementing collective choice.[9]

This depiction is widely, although not uniformly, accepted by mainstream legal scholars and social scientists. It has not escaped criticism on analytical and ideological grounds but, subject to some qualifications, has proved to be a valuable research tool. There can be little doubt that the notion of a governance regime is a less mechanistic and more effective vehicle for capturing the essence of intricate international realities than that of an arrangement, treaty and so forth. However, in the environmental domain, where regulatory imperatives typically loom large, the initial definition has been fine-tuned with a view to imbuing it with a greater sense of concreteness.

It has thus been suggested that ‘operating procedures’ (‘prevailing practices for work within [a] regime, including methods for making and implementing collective choice’[10]) might dovetail better with the experience of governance regimes than ‘decision-making procedures’.[11] This has led to a subtle shift from the latter to the former. Perhaps more importantly, from a managerial perspective, as distinct from a purely theoretical one, it has been underscored that functioning governance regimes, successful or otherwise, include ‘institutions that actors create or accept to regulate and coordinate action in a particular issue area’.[12]

The thrust of the constructivist argument is that agents, both individually and collectively, act towards objects (including players in the socio-legal arena with whom their paths cross), directly or indirectly, on the basis of meanings that those objects possess for them.[13] The corollary is that, in addressing international issues, ‘[s]tates act differently toward enemies than they do toward friends because enemies are threatening and friends are not’.[14] To express it more specifically, ‘US military power has a different significance for Canada than for Cuba, despite their similar “structural” positions, just as British missiles have a different significance for the United States than do [Russian] missiles’.[15]

Such meanings are assumed to be the foundation underpinning socio-legal systems and the key element that determines their operational positioning. By participating in processes via which meanings are acquired, actors of all shapes gain identities, that is, clearly discernible and role-unique understandings and expectations about self. These defining attributes are relational (‘[i]dentity, with its appropriate attachments of psychological reality, is always identity within a specific, socially constructed world’[16]) and may assume a variety of forms (‘a state may have multiple identities as “sovereign,” “leader of the free world,” “imperial power,” and so on’[17]).

The book is not the first systematic attempt to apply regime theory and constructivist thought in the ASEAN context. It was preceded by an earlier effort, more heavily steeped in constructivism, to interpret developments in the pivotal regional defence realm from a similar viewpoint.[18] That previous work drew a distinction between a security community and less cohesive structural patterns such as an alliance, or a defence community, and even a security regime.[19] A security community is a manifestation of a broader and deeper commitment because it is ‘distinguished by a “real assurance that the

members ... will not fight each other physically, but will settle their disputes in some other way”’.[20] This constellation may ‘either be ‘“amalgamated” through the formal political merger of the participating units, or remain “pluralistic”, in which case the members retain their independence and sovereignty’.[21]

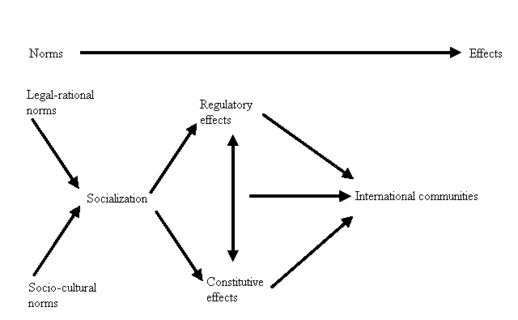

The dynamics of a security community, as seen from a constructivist angle, is shaped by legal-rational norms and their socio-cultural counterparts, imparted through a process of socialisation in a collective institutional setting, which generate regulatory and constitutive (cohesion-enhancing) effects. The end product is a distinct group identity and its behavioural consequences.[22] This differs from neoliberal conceptualisations which primarily regard international institutions as channels for mitigating anarchy, facilitating cooperation by providing information, reducing transaction costs, helping to settle distributional conflicts and, most importantly, reducing the likelihood of cheating — or, put another way, provide a rationalist, utility-maximising and sanction-based perspective on international cooperation.[23]

By contrast, constructivism is said to furnish a qualitatively more far-reaching model of how collective institutions, such as those fashioned by ASEAN, influence and modify state interests and conduct. Specifically, they are assumed to constitute state identities and preferences, rather than merely to regulate their behaviour. The corollary is that collective institutions may be portrayed as agents of socialisation, defined as ‘regular, formal or informal, interaction (dialogue, negotiations, institutionalisation) among a group of actors to manage mutual problems, realise a common purpose, achieve some collective good, and develop and project a shared identity’.[24]

Figure 1:[25] Model of International Community Formation

The book under review takes this analytical foundation as a logical

point of departure, drawing particular attention to two cohesion-enhancing

mechanisms: the ‘ASEAN Way’ and ASEAN norms. A salient feature of the former is the extensive reliance on consultation and the quest for consensus stemming from the Malay socio-cultural practices of musjawarah (consultation) and musfakat (consensus). Both behavioural modes are believed to have contributed to the emergence of collective trust in ASEAN and to have promoted regional stability.

The ASEAN (legal-rational) norms are thought to have served a similar function. Different classifications are offered, but the author chooses to focus on sovereign equality, non-use of force and pacific settlement of disputes, regional autonomy or regional solutions to regional problems, doctrine of

non-interference, and no military pacts and a preference for bilateral defence cooperation. The role of quiet diplomacy — including, initially at least, a

non-legalistic approach to cooperation involving recourse to non-binding private capacity — is also highlighted.

Fully equating a collective institutional mechanism designed to combat forest burning and its environmental repercussions with one geared towards eliminating armed conflict and fostering peaceful coexistence is not a practical proposition. The author nevertheless depicts the system that has crystallised over the past three decades or so as a regime with community-like characteristics. This may largely be due to the fact that, although the final destination cannot yet clearly be delineated, ASEAN is viewed as an entity which is being transformed into a

full-fledged community, including in the socio-cultural sense of the term. However, it may also reflect the inevitability of encountering difficulties in drawing too rigid a distinction between a regime and a community, not entirely productive even within the defence sphere, a point to be revisited at a later juncture.

The rise of the regime is outlined in chronological fashion, beginning with the 1982–83 ‘Great Fire of Borneo’, which set in flames approximately 3.2 million hectares of land (predominantly in the logged-over forest in East Kalimantan), and unleashed haze pollution that materially affected several countries in the region, capturing international attention as a result. Landmark events, qualifying as turning points in the prolonged and stepwise process, are given prominence. They include the ASEAN Cooperation Plan on Transboundary Pollution,[26] Regional Haze Action Plan[27] and eventually and most significantly, AATHP.

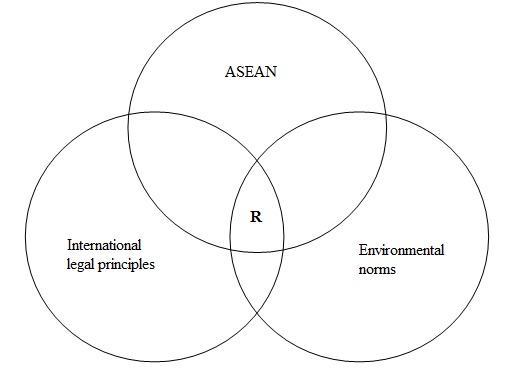

Figure 2:[28] Key Forces Shaping the ASEAN Fire Conservation and Haze Pollution Containment Governance Regime

Key elements of the regime are subsequently identified and detailed. They may be directly or indirectly traced to the international legal norm of state responsibility for transboundary haze pollution. Their concrete manifestations involve specific measures to ensure prevention, monitoring and mitigation. The non-ASEAN influences — in the form of environmental norms, primarily originating elsewhere, and international legal principles — are noteworthy because they underscore the increasingly open nature of the regime and its growing external linkages.

While the analytical path followed seldom deviates from the constructivist blueprint, pinpointing the origins of the regime unavoidably brings to the fore other forces shaping its evolution. It is the series of seemingly never-ending crises and their enormous cost — economic, environmental, political and

social — which serve as the principal action triggers and propellants, as well as, where appropriate, barriers to progress and reversal inducers. Indeed, the rationalist notion of gains and losses keeps on surfacing, whether explicitly or implicitly, both in its absolute and relative form — the latter too, because the numerous stakeholders across the region, including domestic constituencies, are not equally affected.

On balance, the impression conveyed — albeit perhaps inadvertently, given the theoretical orientation — is that normative drivers, identity formation and learning/socialisation in the course of ongoing collective problem solving have not been the dominant element in the intricate equation but have played a secondary role. Nor is compelling evidence presented to suggest that state and group interests and preferences impacting regional strategies in this crucial domain have been primarily, let alone exclusively, the product of identity and learning/socialisation. The light shed on the contribution of these two factors enhances understanding of the building of the ASEAN forest conservation and haze pollution containment governance regime, yet it falls short of providing, without additional insights of the traditional-style rationalist genre, a comprehensive explanatory framework. As the author acknowledges, without decisively relegating ideational influences to the empirical periphery, when attempting to construct a composite picture:

In sum, economic interest is a major driving force for regional cooperation on the haze. The ‘economic interest’ in many cases is interrelated with political interest. The notion of ‘interest’ itself is multi-dimensional, highly complex and differs from one actor to another. Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand would, in principle, benefit from cooperation in a regime. The level of reciprocity, however, varies.[29]

International governance regime-building is a multi-phase process entailing not merely joint problem definition, establishment of organisational architecture, articulation of strategy and adoption of concrete measures (such as hard law, soft law and more informal expressions of collective intent) to alleviate symptoms of economic, environmental, political and social dislocation. Further action is required to ensure system effectiveness where it matters, at the appropriate public decision-making levels within national territory. Specifically, the final stage of regime formation is assumed to occur

when the translation of the international legal agreement [like AATHP] takes place and begins to have observable legal effect — such as the ratification of an international agreement — an indication of the early effect of a regime on domestic institutions.[30]

The author furnishes a characteristically thorough account of initiatives embraced regionally and by individual countries in the post-AATHP period. This is arguably the least constructivist-inspired part of the book, although the paradigmatic element is not altogether absent. Importantly, Indonesia and the Philippines have refrained from ratifying the agreement. Elsewhere the process has been slow — although implementation and enforcement in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand may have eventually reached adequate standards, albeit by no means uniformly so. Where this has not been the case, uncontrollable variables (eg the severe drought in the second half of 2006, which seriously aggravated conditions in the northern section of the ASEAN region), have played a disruptive role.

However, violation of environmental norms, laws and regulations has persisted, a pattern the author attributes to unsatisfactory socialisation. The failure of learning/socialisation is not a trivial matter. This inevitably implies that there may have been more potent influences at work than regional identity and responsibility. The author focuses on a host of technical challenges affecting state capacity,[31] powerful corporate interests, political constraints and widespread corruption in key areas (although obviously not in Singapore). The non-technical influences, and even the technical ones, to the extent that they represent an unwillingness to invest, may comfortably be accommodated within a rationalist-style framework, provided it is not too narrowly delineated and leaves scope for incorporating, on a sufficient scale, other variables, including those of the constructivist genre.

This is an important and illuminating study, and its significance extends well beyond the confines of the geographic and policy domain it encompasses. It is conceptually and empirically rich, attributes that should combine to propel it to prominence in the scientific space where it is positioned. It adopts a distinct theoretical perspective but, in practice, not as rigidly as some other academic work, notably that on ASEAN’s security community, intimately associated with the same school of thought. Consequently, it provides greater scope for evaluating the merits and demerits of the paradigm it embraces in light of the extensive factual information it generates.

Constructivism is an integral and key component of today’s positive international legal theory edifice. Its analytical logic underpins closely related and equally influential conceptual schemes (most importantly transnational legal process theory, which places as much emphasis on normative stimuli and learning/socialisation), within network-like structures driven by multiple change agents, in the global arena.[32] Both perspectives lay substantial stress on value acquisition in cooperative international settings but for the most part without firmly coupling their elaborate propositions with solid empirical findings. There is no dearth of supporting examples, which are readily invoked, yet the question often arises whether they are sufficiently representative and not susceptible to selection bias. The book under review thus qualifies as a rare research undertaking, among those inspired by the constructivist paradigm in international law, by virtue of its factual robustness.

On the other hand, in terms of fulfilling the author’s theoretical agenda, the picture is rather mixed. The contribution made in this respect is considerable but more indirectly than directly so, by allowing readers to draw inferences that are not entirely consistent with the analytical framework within which the dissection of the empirical evidence is conducted. The problem here lies in what social statisticians portray as ‘over-interpretation’, which may manifest itself in a number of ways yet in qualitative inquiries of this nature typically assumes the form of extrapolation beyond the range of the data available.[33]

The point is that the facts simply do not firmly support the image of the ASEAN governance regime as being focused on environmental and forest conservation and the containment of transboundary haze pollution. Nor do they provide a strong reinforcement for the constructivist enterprise — broadly defined — in international law. The governance regime issue is not conceptually challenging because the difficulties encountered are not with the notion and its scope per se but with the degree of its applicability in this specific geographic context, as well as the extent to which it can be stretched to account for developments in the ecological domain. The question of constructivism and complementary intellectual systems gives rise to greater uncertainty due to the fundamental limitations exposed in juxtaposing them with complex institutional realities over a long period of time.

International governance regimes vary significantly in their effectiveness. Some qualify as strong while others may be designated as weak. The balance between sturdiness and fragility hinges on a number of factors, with the

issue-area (eg, defence versus the environment) being particularly relevant, but given the impediments to genuine inter-state cooperation, weakness commonly tends to overshadow strength. The ecological realm is no exception to the

rule — indeed it readily validates the rule, as exemplified by the travails of the global climate warming regime, if it at all merits the status of ‘regime’.[34]

Broadly speaking, ASEAN’s governance regime has grown quantitatively and qualitatively since the turbulent late 1960s. It has also displayed a measure of adaptability and resilience, in the face of periodically substantial challenges and pressures, expanding its strategic agenda and seeking progressively deeper integration. It is currently contemplating an ambitious transition to a full-fledged regional community. However, this has been a distinctly uneven journey, with performance more often than not falling short of aspirations.[35]

While some informed commentators see the proverbial glass as nearly full, others view it as at best half full, or even half empty. They question the evidence that the multi-decade collective quest for harmony has socialised AMCs into obtaining a meaningful sense of regional identity and that this identity has materially influenced their conduct vis-a-vis members and outsiders.[36] Rather, they postulate that ASEAN has been designed as an organisational vehicle to enable members to pursue their individual interests — in a compatible fashion where possible — and has served this purpose reasonably well.

The display of disarray witnessed — when external strains greatly intensified during the 1997–98 Asian financial crisis — is among the experiences invoked to illustrate the organisation’s lack of a genuinely overarching goal and the shallowness of its attitudinal bonds.[37] This highly disruptive event is said to have laid bare ASEAN’s limited capabilities and susceptibility to shocks as a player in the regional and global arenas.[38] It is also believed to have highlighted its pervasive institutional frailties, which may have been concealed behind a shallow façade of organisational unity.[39]

Such episodes have prompted some observers to depict ASEAN as an institution adept at ‘big talk’ but in practice merely ‘modest actions’.[40] In this context and particularly in light of ASEAN’s problematic origins, it is interesting to note that a recent survey has shown that, although not

negligible, the level of trust between AMCs and societies at the grassroots level continues to be too low to suggest that it is ready for a strategic leap towards the formation of a truly multifaceted and viable regional community, in accordance with its avowed aims.[41]

The book under review endeavours to offer a more reassuring diagnosis, underpinned by a constructivist vision of an increasingly cohesive and fruitfully engaged collective entity. However, the ample facts considered, including by other researchers,[42] are more consistent with a ‘glass half-full’ perspective and cannot productively be placed within a one-dimensional theoretical

framework — whether constructivist, rationalist or other (although especially the former). A comprehensive evaluation of the ASEAN forest conservation and haze pollution containment governance regime requires the adoption of a

multi-level input/output perspective that is wider than that commonly relied upon by international legal scholars.

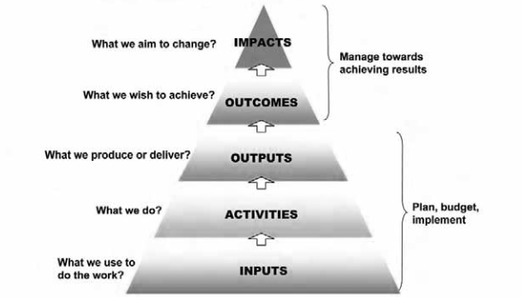

Such a complex institutional structure typically consumes resources (inputs), undertakes activities and delivers outputs (eg laws, regulations, directives, guidelines and so forth) which have consequences in the form of outcomes (eg ratification, implementation, enforcement, compliance and so forth) and impacts (eg problem alleviation, stability enhancement, welfare gains and so forth).[43] International legal scholars tend to focus on outputs and outcomes, while according less attention to impacts, which are deemed to be the preserve of natural and social scientists who are technically better equipped to undertake tasks such as environmental impact assessments and social impact assessments. Moreover, the examination of outputs and outcomes typically contains some analytical gaps.

There are sound grounds for arguing that the outputs and outcomes of the ASEAN forest conservation and haze pollution containment regime leave something to be desired. This is partly reflected in the book under review and the work of other socio-legal researchers.[44] Regarding impacts, the picture broadly painted is even more discouraging, although a degree of caution should be exercised in interpreting it because no hard data are systematically presented and prevailing realities are not compared to a baseline scenario that would portray environmental conditions and their consequences in the absence of any policy initiatives, however modest, to enhance regional governance.[45]

Figure 3:[46] Model of International Community Formation

Space constraints prevent a detailed discussion of the inadequacies observed at the output and outcome levels. Pinpointing the salient deficiencies of AATHP, hailed as a manifestation of ASEAN’s resolve to confront in earnest the twin challenges of forest burning and transboundary haze pollution, and a marked improvement on its predecessors such as the Regional Haze Action Plan formulated in the wake of the widespread forest fires and land destruction in 1997, should prove sufficient to highlight the flaws characterising the regional instruments designed to this end and their implementation.

As noted earlier, Indonesia, the key protagonist in the drama, has opted not to join the enhanced regime (Cambodia, like the Philippines, has also engaged in foot-dragging), seriously undermining its effectiveness. The institutional delays, inertia and reticence witnessed have largely been attributed to structural impediments and capacity constraints faced by resource-poor and overstretched countries, but they have in fact masked a reluctance to make the needed strategic adjustment and bear the necessary sovereignty and domestic political costs. The AATHP itself scarcely qualifies as an ideal international agreement to meaningfully address a collective problem of this magnitude. Quite the contrary, it is marked by substantial concessions to state sovereignty, insufficient terminological precision, non-binding elements and weakness of provisions pertaining to deterrence and enforcement (including dispute resolution).[47]

In seeking explanations for this unsatisfactory pattern, there is no compelling reason to force the empirical evidence into a constructivist — or, for that matter, transnational legal process theory — straightjacket, although removing this component altogether from the analytical equation might be a questionable

step as well. A number of alternative accounts are possible, mostly of the

realist/neo-realist variety (eg, Indonesia’s displeasure at losing two islands, Ligitan and Sipidan, to Malaysia in 2004 and the absence of a hegemonic power, such as the US, to drive the region-wide regulatory system towards a higher-level equilibrium),[48] but greater weight should arguably be accorded to two different types of rationalist insights.

First, on the home front, the inescapable reality of the cartelisation of the policy process in favour of private interests, coupled with the capture of the regulatory machinery by such interests in several AMCs, has to be taken into consideration. Notably, as amply documented, in Indonesia, the patrimonial or patron-client governance model has traditionally been the primary cause of deficient forestry practices. According to this conceptual structure, timber concessionaries have been holders of benefices from the ruler, a kind of transaction that has amounted to a complementary power, unavoidably to the detriment of the general population. Initially, this constellation denied ‘the indigenes of the use and enjoyment of the forest, and ordinary citizenry of any revenues or income from the timber trade, while creating an extralegal sphere beyond the reach of normal state regulation’.[49] Subsequently, ‘[t]he forestry practices that arose in these circumstances then generated additional expenses, in the form of haze and environmental degradation’.[50] The ruler-focused patrimonial configuration has given way in recent years to a more open and transparent system, but neither policy cartelisation nor regulatory capture can be said to be a thing of the past.

Second, Southeast Asia’s ‘Developmental State’ (originally a Northeast Asian governance blueprint) has long placed a higher value on economic development than environmental preservation. It has thus been more willing to cross borders to promote trade, investment and finance than to alleviate ecological externalities, at least during the initial and intermediate phases of industrialisation. The Asian ‘Developmental State’ is of course underpinned by a solid alliance between the politico-bureaucratic apparatus and corporate interests, so its preferences are not entirely autonomous and may partly reflect those of private power centres (cartelisation, regulatory capture and so forth). This does not prompt the author to abandon her constructivist leanings, yet she eventually unambiguously succumbs to the lure of rationalist logic: ‘The construction of an ASEAN haze regime is a result of a complex rationality of the member states influenced by both material and ideational factors at the domestic, regional and international levels’.[51]

Models of international governance regimes need to be commensurate with such complexity. The ASEAN experience in combating forest burning and transboundary haze pollution illustrates that rationalist theories must constitute the foundation of any explanatory framework employed to shed light on structural and functional attributes of regional and higher-level regulatory constellations, but it also shows the potential inadequacy of formulations that omit ideational/constructivist/transnational legal process theory-like influences. Indeed, additional contextual-type variables may have to be taken into consideration. For instance, in this particular case it is inappropriate to overlook the role played by hysteresis, or history, in the development of ASEAN governance regimes. Specifically, whereas the trauma of the Second World War has undermined nationalism in Europe, the strains engendered by decolonisation have reinforced it in Southeast Asia.[52] The merits of synthesising divergent analytical perspectives are beginning to be selectively highlighted but not decisively.[53]

Three further observations — two methodological-style and one

policy-oriented — are in order. First, constructivism and transnational legal process theory place a heavy emphasis on the role of change agents, such as the epistemic community in the book under review, in fostering identities and promoting international values conducive to liberal world order. The agents are located, classified and assumed to be collectively engaged in the pursuit of the common good. However, their relationships, motivations and activities are depicted rather loosely. Recourse to formal exploratory tools such as social network analysis and stakeholder mapping might enhance the quality of the exercise and reveal more illuminating inter-organisational patterns.[54]

Secondly, change agents abroad and at home are assumed to be key facilitators of normative learning/socialisation in collective settings. Yet, the mechanisms via which the transmission takes place are not precisely specified, in this study and in the theoretical space where it belongs in general. For all intents and purposes, the learning process is posited to be linear and orderly, without serious setbacks and reversals. Issues such as the interplay between normative and instrumental (interest-based) learning,[55] exact path followed (incremental movement versus quantum leaps, diversions and feedback loops) and tension between conflicting identities (entrenched, economically-inspired anthropocentric and hopefully emerging ecocentric) remain mostly below the surface.

To her credit, the author presents a picture of a ‘messy’ reality and confronts it head-on. However, the encounter with intricate Southeast Asian behavioural trends in the environmental domain is not used to enrich the conceptual scheme that underpins the study. This does not serve to dispel the impression that, despite assertions to the contrary, constructivist models in international law often tend to be static and one-dimensional,[56] as exemplified by the too readily embraced controversial proposition that peripheral Sweden waged the Thirty Years’ War against the far more formidable Habsburg Empire merely to reaffirm its identity as an emerging power in 17th century Europe.[57]

Thirdly, also to her credit, the author offers a number of policy recommendations as to how to improve the functioning of the ASEAN forest conservation and haze pollution containment governance regime. Yet, those ideas too bear little relationship to the constructivist vision underlying the project. This may partly be due to the fact that ‘pessimistic’ scientific paradigms provide a more fertile ground for designing effective regulatory systems than those imbued with a sense of ‘optimism’ regarding humankind’s built-in propensity to seek the common good and for positive forces to overwhelm negative ones through normative learning. It may also be owing to circumstances whereby constructivism and transnational legal process theory have still not progressed to a stage whereby the transition from ‘passive’ diagnosis to ‘active’ prognosis could productively be made.[58]

As matters stand, not many concrete suggestions can be furnished on this basis beyond enhancing the quality of normative education/training, empowering civil society organisations,[59] increasing exposure to international bodies, intensifying lobbying and opening up communication channels. These are not meaningless measures but other, more decisive steps, typically (rather than exclusively) entailing rationalist[60] reengineering, ought arguably to take precedence. This excellent book, despite suffering from a ‘misplaced (theoretical) identity’, constitutes a poignant reminder that multifaceted inquiry[61] is the optimal path to configuring and reconfiguring international governance regimes.

RODA MUSHKAT[*]

[1] See especially Amitav Acharya, Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order (Routledge, 2nd ed, 2009).

[2] ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution, opened for signature 10 June 2002 (entered into force 25 November 2003).

[3] Declaration constituting an Agreement establishing the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), opened for signature 8 August 1967, 1331 UNTS 235 (entered into force 8 August 1967) (‘ASEAN Declaration’).

[4] Vientiane Action Programme (VAP) 2004–2010, opened for signature 29 November 2004, [2004] ASEAN Documents Series 20 (entered into force 29 November 2004).

[5] Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, signed 3 March 1973, 993 UNTS 243 (entered into force 1 July 1975) (‘CITES’).

[6] Paruedee Nguitragool, Environmental Cooperation in Southeast Asia: ASEAN’s Regime for Transboundary Haze Pollution (Routledge, 2011) 45.

[7] For a discussion of this phenomenon, see ibid 99–122, 150–2.

[8] Stephen D Krasner, ‘Structural Causes and Regime Consequences: Regimes as Intervening Variables’ in Stephen D Krasner (ed), International Regimes (Cornell University Press, 1983) 1, 2.

[9] Ibid 2.

[10] Pamela S Chasek, David L Downie and Janet Welsh Brown, Global Environmental Politics (Westview Press, 5th ed, 2010) 19.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Alexander Wendt, ‘Anarchy is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics’ (1992) 46 International Organization 391, 396–7.

[14] Ibid 397.

[15] Ibid. For additional insights, see Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

[16] Peter Berger, ‘Identity as a Problem in the Sociology of Knowledge’ (1966) 7 European Journal of Sociology 105, 111 (emphasis altered).

[17] Wendt, ‘Anarchy is What States Make of It’, above n 13, 398. For additional insights, see Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, above n 15.

[18] See generally Acharya, above n 1.

[19] See ibid 18–23.

[20] Ibid 18, quoting Karl W Deutsch et al, Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience (Princeton University Press, 1957) 5.

[22] See Figure 1.

[23] Acharya, above n 1, 24, citing Robert Keohane and Lisa Martin, ‘The Promise of Institutionalist Theory’ (1995) 19(1) International Security 39, 47.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Adapted from: Acharya, above n 1, 31.

[26] ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Cooperation Plan on Transboundary Pollution (ASEAN Secretariat, 1995).

[27] ASEAN, Regional Haze Action Plan (December 1997) ASEAN Haze Action Online <http://haze.asean.org/?page_id=213> .

[28] Adapted from: Nguitragool, above n 6, 75.

[29] Nguitragool, above n 6, 97.

[30] Ibid 123.

[31] This is an argument that looms large in writings of scholars who belong to the managerial, rather than constructivist, strand of the literature on international legal compliance: see generally Abram Chayes and Antonia Handler Chayes, The New Sovereignty: Compliance with International Regulatory Agreements (Harvard University Press, 1995).

[32] See generally Harold Hongju Koh, ‘Transnational Legal Process’ (1996) 75 Nebraska Law Review 181; Harold Hongju Koh, ‘Why Do Nations Obey International Law?’ (1997) 106 Yale Law Journal 2599; Harold Hongju Koh, ‘How is International Law Enforced?’ (1999) 74 Indiana Law Journal 1397.

[33] See generally Christopher Winship and Robert D Mare, ‘Models for Sample Selection Bias’ (1992) 18 Annual Review of Sociology 327.

[34] See generally Daniel Bodansky and Elliot Diringer, ‘The Evolution of Multilateral Regimes: Implications for Climate Change’ (Paper, Pew Center on Global Climate Change, December 2010).

[35] See generally Michael Leifer, ASEAN and the Security of South-East Asia (Routledge, 1989); Sajid Anwar and Choon-Yin Sam, ‘Is Economic Nationalism Good for the Environment? A Case Study of Singapore’ (2012) 36 Asian Studies Review 39; Ayyappan Palanissamy, ‘Haze Free Air in Singapore and Malaysia — The Spirit of the Law in South East Asia’ (2013) 1(8) International Journal of Education and Research 1 <http://www.ijern.com/journal/August-2013/09.pdf> .

[36] See generally Leifer, above n 35.

[37] See generally Jürgen Rütland, ‘ASEAN and the Asian Crisis: Theoretical Implications and Practical Consequences for Southeast Asian Regionalism’ (2000) 13 Pacific Review 421.

[38] See generally ibid.

[39] See generally ibid.

[40] Hiro Katsumata, ‘The ASEAN Charter Controversy: Between Big Talk and Modest Actions’ in Yang Razali Kassim (ed), Strategic Currents: Emerging Trends in Southeast Asia (S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, 2009) 11.

[41] See Christopher B Roberts, ‘The ASEAN Community: Trusting Thy Neighbour’ in Yang Razali Kassim (ed), Strategic Currents: Emerging Trends in Southeast Asia (S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, 2009) 15. See also Helena Varkkey, ‘Regional Cooperation, Patronage and the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution’ (2014) 14 International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 65.

[42] See generally Simon S C Tay, ‘South East Asian Forest Fires: Haze over ASEAN and International Environmental Law’ (1998) 7 Review of European Community and International Environmental Law 202; James Cotton, ‘The “Haze” over Southeast Asia: Challenging the ASEAN Mode of Regional Engagement’ (1999) 72 Pacific Affairs 331; Alan Khee-Jin Tan, ‘Forest Fires of Indonesia: State Responsibility and International Liability’ (1999) 48 International and Comparative Law Quarterly 826; Simon S C Tay, ‘Southeast Asian Fires: The Challenge for International Environmental Law and Sustainable Development’ (1999) 11 Georgetown International Environmental Law Review 241; Euston Quah, ‘Transboundary Pollution in Southeast Asia: The Indonesian Fires’ (2002) 30 World Development 429; Lorraine Elliott, ‘ASEAN and Environmental Cooperation: Norms, Interests and Identity’ (2003) 16 Pacific Review 29; Ebinezer R Florano, ‘Assessment of the “Strengths” of the New ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution’ (2003) 4 International Review for Environmental Strategies 127; David Seth Jones, ‘ASEAN Initiatives to Combat Haze Pollution: An Assessment of Regional Cooperation in Public Policy-Making’ (2004) 12(2) Asian Journal of Political Science 59; Alan Khee-Jin Tan, ‘Environmental Laws and Institutions in Southeast Asia: A Review of Recent Developments’ [2004] SGYrBkIntLaw 11; (2004) 8 Singapore Year Book of International Law 177;

Alan Khee-Jin Tan, ‘The ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution: Prospects for Compliance and Effectiveness in Post-Suharto Indonesia’ (2005) 13 New York University Environmental Law Journal 647; David Seth Jones, ‘ASEAN and Transboundary Haze Pollution in Southeast Asia’ (2006) 4 Asia Europe Journal 431;

Md Saiful Karim, ‘Future of the Haze Agreement — Is the Glass Half Empty or Half Full?’ (2008) 38 Environmental Policy and Law 328; Koh Kheng-Lian, ‘A Breakthrough in Solving the Indonesian Haze?’ in Sharelle Hart (ed), Shared Resources: Issues of Governance (Environmental Policy and Law Paper No 72, International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2008) 225.

[43] See Figure 3.

[44] ‘Partly’, because a more comprehensive evaluation would require the incorporation of additional pertinent criteria into the analytical vehicle employed for this purpose. See generally Miron Mushkat and Roda Mushkat, ‘Assessing the Effectiveness of Environmental Governance Regimes: Remaining Gaps’ (2011) 12 Interdisciplinary Environmental Review 166.

[45] In addition to the book under review, considerable information relating to the outputs, outcomes and impacts of the ASEAN forest conservation and haze pollution containment regime is found in the studies cited in above n 42.

[46] Adapted from: National Treasury of the Republic of South Africa, ‘Framework for Managing Programme Performance Information’ (Framework, May 2007) [3.1] <http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/learning/reference/framework/part3.pdf> .

[47] See Jones, ‘ASEAN Initiatives to Combat Haze Pollution’, above n 42, 67–8; Tan, ‘The ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution’, above n 42, 663–70.

[48] See Nguitragool, above n 6, 6–7, 95–6.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Nguitragool, above n 6, 152.

[52] See Asian Development Bank, Emerging Asian Regionalism: A Partnership for Shared Prosperity (Final Report, Asian Development Bank, 2008) 240–2.

[53] See generally J Samuel Barkin, ‘Realist Constructivism’ (2003) 5 International Studies Review 325; Gerry Nagtzaam, The Making of International Environmental Treaties: Neoliberal and Constructivist Analyses of Normative Evolution (Edward Elgar, 2009); J Samuel Barkin, Realist Constructivism: Rethinking International Relations Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[54] See generally Christina Prell, Klaus Hubacek and Mark Reed, ‘Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in Natural Resource Management’ (2009) 22 Society and Natural Resources 501.

[55] See generally Jeffrey T Checkel, ‘The Constructivist Turn in International Relations Theory’ (1998) 50 World Politics 324; Michael Zürn and Jeffrey T Checkel, ‘Getting Socialized to Build Bridges: Constructivism and Rationalism, Europe and the Nation-State’ (2005) 59 International Organization 1045.

[56] For an elaborate and illuminating (near) exception to the rule, see Afshin Akhtarkhavari, Global Governance of the Environment: Environmental Principles and Change in International Law and Politics (Edward Elgar, 2010).

[57] See David Armstrong, Theo Farrell and Hélène Lambert, International Law and International Relations (Cambridge University Press, 2007) 96, citing Erik Ringmar, Identity, Interest and Action: A Cultural Explanation of Sweden’s Intervention in the Thirty Years War (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[58] That is not to say that some headway is not being made: see, eg, Ryan Goodman and Derek Jinks, Socializing States: Promoting Human Rights through International Law (Oxford University Press, 2013).

[59] Far-reaching ideas in this respect are found in Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite, Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate (Oxford University Press, 1992).

[60] For example, augmenting disclosure; bonding, insulating, pre-committing and properly compensating regulators; curtailing concentration of economic resources; demarcating land/property rights; fine-tuning incentives; harnessing markets; strengthening tort remedies and so forth.

[61] Partial illustration of a relevant synthesis of normatively-inspired and strategically-oriented perspectives is provided in Aseem Prakash and Mary Kay Gugerty (eds), Advocacy Organizations and Collective Action (Cambridge University Press, 2010). Prakash and Gugerty build in a more prescriptive fashion on work by Keck and Sikkink: Margaret E Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics (Cornell University Press, 1998).

[*] Professor Of International Law, Hopkins-Nanjing Centre, Paul H Nietze School of International Studies (SAIS), Johns Hopkins University and Honorary Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/MelbJlIntLaw/2014/8.html