Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

BRUCE ARNOLD,[*] PATRICIA EASTEAL AM,[**] SIMON EASTEAL[†] AND SIMON RICE OAM[‡]

[Standard workplace conditions that are commonly perceived as neutral and reasonable can discriminate against people who find conforming to them difficult or impossible because of innate differences in neuronal and cognitive functioning. We use the example of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder to show that, for people with cognitive differences, it is necessary to seek legal protection from discrimination within a disability framework. This approach can be problematic because of the stigma that attaches to disability and because of the way that provisions of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) are interpreted. An alternative approach is to treat cognitive and behavioural attributes within a framework that recognises different abilities, rather than starting from a presumptive position of disability, in much the same way that gender or religious beliefs are treated.]

Biases in cultural values and legal systems are frequently unidentified and therefore invisible. The result can be discriminatory practices that cause great harm to many individuals but which, because they are unrecognised, remain unchecked. An additional consequence of the invisibility of these underlying biases is that those affected by the discrimination are often stigmatised and blamed for the disadvantages they experience.

Consciously and unconsciously, people compare others to socially constructed norms that are sexist, ableist, racist, ethno-religious and heteronormative.[1] Behind these overt constructions of what is normal lie layers of assumptions, which we cease to be aware of over time. As individuals and as a society we have come to think that these beliefs — which underpin much of how we think, feel, perceive and behave — are ‘natural’[2] and in the process we unconsciously deny the legitimacy of the way many people experience the world and ignore contributions of those who are different. The assumptions and behavioural patterns of those with power prevail, systemically disadvantaging members of minority groups.

Our workplaces are set in such a context, and are often insensitive to differences based on sex, race, disability, ethnicity, sexual affinity, demeanour and other ‘others’.[3] Workplace conditions ‘designed, whether deliberately or unreflectively, around the behaviour patterns and attributes of the historically dominant group in public life’[4] become the norm. They give rise to ‘conventional expectations’ that form a basis for decisions in recruitment, performance management and reward, including promotion, and are usually not recognised as potentially discriminatory because they are assumed to be neutral measurements of performance, applied to everyone.

Mayes, Bagwell and Erkulwater[5] discuss how the design of the physical infrastructure and cultural conventions — buildings, public transport systems, education programs, employment practices — of the modern world were established at a time when there was little acknowledgment of diversity and when people with disabilities were removed from public life. Once established, these structures became entrenched and difficult to replace with alternatives that are better designed to accommodate the diversity of human ability. Rather, people for whom these structures were never designed and to which they are not well suited need special treatment in order to fit in and, as a consequence, they appear disabled.

An example of such normalisation, and of the perception that certain conditions are necessary or unremarkable — but which are in fact disadvantageous to some — is the requirement to work long hours (outside ‘nine to five’) with early morning and/or evening and weekend meetings: such a requirement is seen by many as both normal and reasonable because it affects all staff ‘equally’; Australian anti-discrimination law, however, challenges the ready acceptance of such ‘normal’ and ‘equally applicable’ requirements. Women have significant parenting and caring roles,[6] and so a substantially lower proportion of women than men comply or are able to comply with a requirement to work full-time or overtime.[7] The ‘normal’ requirement therefore has a disparate effect on around half of the workforce, and when such a requirement is unreasonable it is in breach of Australian anti-discrimination law.[8]

This example of women’s relative inability to comply with ‘normal’ expectations at work demonstrates how employment conditions and decisions can invisibly disadvantage a group. It also shows how anti-discrimination law can treat a disadvantage as arising from a legitimate difference rather than from a disability. The disadvantage that women experience is conceptualised without treating women as less ‘abled’ than men.

We examine this kind of unconscious normalisation in the context of the emerging evidence that diverse ways of thinking (cognitive diversity) arising from a variety of types of brain (so-called ‘neurodiversity’) are a fundamental aspect of human nature. Using the example of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (‘ADHD’) — sometimes also referred to as attention deficit disorder (‘ADD’),[9] since hyperactivity is rarely a defining characteristic in adults[10]

— we consider how, as in the case of gender, anti-discrimination law might address disadvantages in the workplace arising from cognitive differences, without treating those differences as disabilities.

We begin by looking at some of the characteristics of ADHD, before considering how these create problems in the workplace and how standard workplace conditions — commonly perceived as neutral and reasonable — unwittingly disadvantage people with ADHD. We then examine the current legal remedies for those so disadvantaged.

ADHD is formalised as a psychiatric condition through its inclusion in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,[11] published by the American Psychiatric Association. It is commonly thought of as a condition that affects children, mainly boys, and it is the most prevalent childhood psychiatric condition.[12] However, it is now well-established, although less well understood, as a condition that can occur throughout adulthood.[13]

There are consistent estimates of around eight per cent for childhood prevalence from large national and birth cohorts in the United States and northern Europe, with boys more likely to be affected than girls.[14]

Prevalence in adults appears to be slightly lower, consistent with the common idea that some people ‘grow out of it’ or ‘learn to cope’. In a recent World Health Organization survey, prevalence in adults was estimated to be in the range of three to seven per cent in the United States and northern Europe,[15] which also makes it one of the most prevalent adult psychiatric conditions.

Characterised by deficits in attention regulation, hyperactivity and impulsivity, ADHD is a highly heritable clinical condition. Genetic factors account for approximately 80 per cent of the differences between people with and without ADHD.[16]

The nature of these genetic differences is beginning to be understood in detail, and variant forms (alleles) of a number of genes are known to be more common in people with ADHD than in other people.[17] Most of these genes encode components of monoamine (particularly dopamine) neurotransmitter signalling systems that are associated with the cognitive and behavioural traits (primarily attention and impulse control) that characterise ADHD. Differences in brain structure are also commonly found in regions associated with the cognitive differences that characterise ADHD.[18]

ADHD is defined in negative terms — inadequacy, inability, inappropriateness, failure, etc.[19]

Diagnostic criteria are couched in the same terms,[20]

as is most of the substantial medical and psychological literature.[21]

Yet, as we demonstrate below, there is good evidence that the condition is associated with positive, even exceptional, attributes.

Unrecognised and untreated, ADHD can have serious lifelong adverse consequences. One of the most notable aspects of ADHD is the range of conditions with which it co-occurs, so-called comorbidities. It occurs in combination with another diagnosis more often than any other psychiatric condition, and because ADHD is usually the first condition to appear,[22] it is likely that it is foundational to other conditions.[23]

Most evidence for the extensive range of conditions that co-occur with ADHD in adolescents and adults comes from a relatively small number of studies[24]

and is summarised in several excellent reviews,[25]

with some additional evidence available for specific conditions, including obesity, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and eating disorders.[26] These studies show that adults and adolescents with ADHD are more likely to smoke, to abuse and to be dependent on alcohol and other substances, and to be overweight or obese. They have a greater chance of having Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymia, Bipolar Disorder, Panic Disorder, Social Phobia, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Generalised Anxiety Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Intermittent Explosive Disorder, eating disorders, and Avoidant, Obsessive-Compulsive, Passive-Aggressive, Depressive, Paranoid, Borderline and Antisocial Personality Disorders. They tend to score higher on scales of psychological maladjustment, including somatization, obsessive-compulsive, phobic, anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, hostility, paranoid ideation and psychoticism scales. They also exhibit higher levels of problem behaviours including withdrawal, aggressiveness and delinquency.

In addition, people with ADHD have poorer general health including higher body mass index, higher cholesterol and more sleep problems. They have more medical and dental problems, including cardiovascular disease, infections, injuries, accidents, physical disability, teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. As a consequence they make greater use of the healthcare system. They also have poorer quality of life and higher rates of early death. They are also more likely to have marital and other relationship and social problems[27]

and they have a far greater chance than people without ADHD of going to prison.[28]

The current way of viewing ADHD as a disorder is relevant to the workplace, as illustrated in Figure 1.[29] As the Figure illustrates, in the absence of therapy, ADHD results in poor educational performance and hence reduces standard employment options. The inherent characteristics of ADHD combined with poor educational outcomes[30]

result in poor work performance,[31]

often leading to unemployment.[32]

The experience of ADHD in the workplace can be inferred from the general characteristics of the condition. Thomas Brown, for example, identifies the following six areas of executive function affected by ADHD that can all be seen as ‘problems’ in the workplace:[33]

• Activation: adults may have great difficulty organising, prioritising and commencing tasks. Routine procedures (form filling, planning, etc) can be a barrier to initial engagement in a project or task, requiring support with these aspects of work.

• Focusing: workers with ADHD can be easily distracted, tuning in and out of conversations and activities around them. People with ADHD experience the world as a barrage to their senses — noises, sights and smells rush in without barriers or protection. Normal noise levels can interfere with their ability to hear conversations or maintain a train of thought. Long, highly-structured work meetings can be particularly problematic for people with ADHD who need interaction and communication to be fluid and unstructured in order to operate effectively.

• Regulating alertness, sustaining effort and processing speed: when required to work on tasks in which they have little interest, people with ADHD can quickly lose energy and alertness and become overwhelmingly tired. They are often more effective when engaged with components of many tasks at once than when working on only one task, unless that task has captured their interest and focus.

• Managing frustration and modulating emotions: people with ADHD are easily frustrated and prone to expressing their emotions in ways that violate workplace rules of courtesy and etiquette, although the same attributes can make them forceful and persuasive in their communication.

• Utilising working memory and accessing recall: although people with ADHD may have outstanding long-term memories, they often find it difficult to process information quickly, resulting in poor verbal and non-verbal working memory, with the latter affecting ability to estimate time (discussed further below).[34]

Writing long and complicated documents can be particularly difficult.

• Monitoring and self-regulating behaviour: social situations can be difficult for ADHD adults, who have trouble identifying important cues in a highly stimulating context and thus in determining appropriate behaviour. With poor impulse control, they can appear to be quite intense and perhaps behave inappropriately in verbal discourse.

In summary, people with ADHD are likely to: experience stress when performing tasks that involve detail; be unable to complete tasks without digressing to other projects; be unable to plan properly because of their inability to conceptualise time; have difficulty performing tasks ‘by the book’; become intensely, even obsessively, concentrated on particular tasks to the exclusion of others and of social relationships; be inclined to interrupt and to ‘talk over’ other people; fail to fulfil commitments; procrastinate, particularly with tedious tasks; have difficulty following instructions; fidget and pace; talk ‘excessively’; and be impatient and ‘emotional’.[35]

Studies of how people with ADHD function in the workplace report higher levels of job terminations,[36]

behaviour problems,[37]

disciplinary actions,[38]

job changes,[39]

absenteeism,[40]

lower income,[41]

poorer performance,[42]

more work-related accidents and injuries,[43]

greater levels of lost role performance,[44]

lower likelihood of full-time employment,[45]

poorer self-evaluation of functioning in teams and greater reliance upon teammates but not an associated acceptance of that reliance.[46]

Differences in ability associated with ADHD are not physical or visible and behaviours that characterise ADHD are experienced by most people from time to time so that they tend to be seen as ‘normal’. As a result, tolerance of the behavioural differences that characterise people with ADHD tends to be low and there is an expectation that they will conform to normal expectations.[47]

Since the great majority of adults with ADHD are undiagnosed, they and their colleagues have no basis on which to explain these and other similar behaviours except in moralistic terms, or as indications of laziness, a ‘willful lack of effort’,[48] an uncooperative attitude, or incompetence — problems that can be fixed through appropriate performance management measures and the application of ‘a bit of self-discipline’.

The problem is compounded by the inconsistent behaviour that is characteristic of people with ADHD. Although unable to focus or to persist with uninteresting tasks,[49] they have an unusual ability for prolonged and intense focus on topics of interest and, as a result, they are capable of outstanding performance in some areas. This pattern is often interpreted as ‘showing what they can do if they really want to’ or ‘if they put their mind to it’ or ‘when they can be bothered’.[50]

Most people can focus and perform tasks even when they do not find them particularly interesting. It is not surprising, therefore, that they often view inconsistent performance as resulting from a lack of sustained effort and believe that it can be remediated by an act of will. It may be difficult for them to accept that this is not the case for everyone — that the inability of people with ADHD to stay focused and perform routine tasks is not something over which they have any control.

ADHD is particularly likely to be overlooked in girls and women,[51]

and in many people’s minds the condition remains associated with fidgety and disruptive boys.[52]

Girls are more likely to present as inattentive (for example, daydreaming at the back of the class) than as hyperactive, and because they are not disruptive they are less likely to be diagnosed and treated.[53] Solden has discussed the serious long-term impact of this relative lack of detection combined with greater societal expectations that women perform the kind of tasks that people with ADHD find particularly difficult, such as remembering important dates and social obligations, managing complex schedules and conflicting priorities, and managing time-dependent routine events and schedules.[54]

To illustrate how people with ADHD can be invisibly disadvantaged by standardised work practices, we use the example of the academic workplace with which we are particularly familiar, and consider the two primary professional functions of a university faculty: education and research.

Although great changes have occurred in recent years, the majority of university teaching still consists of the formal presentation of material to students by lecturers, with assessment on the basis of formal examinations and written assignments. Students with ADHD are likely to find it particularly difficult to sit through lectures, read textbooks, sit through exams and hand in assignments on time.[55] They frequently have inconsistent academic records, sometimes doing brilliantly, ‘showing what they are really capable of’, and failing or doing poorly at other times.[56]

As adults with ADHD, their ADHD-affected lecturers are likely to have similar difficulties, for example in preparing lectures, staying focused, showing up on time, marking exams and being consistent in the assessment of students.[57]

Like their student counterparts, they may be brilliant at times, delivering inspiring lectures that affect individual students in a life-changing way, but at other times they may appear disorganised, unprepared and confusing. The result may be inconsistent evaluations of their performance. In a system in which lecturers are evaluated in terms of mean scores of standard metrics, they are unlikely to do well even when their educational contribution has been transformational.

There is no reason why ADHD-affected lecturers or students need to suffer and underperform in this way, to the detriment of both. The tasks students are required to carry out and the situations in which they are required to operate often bear little or no resemblance to those for which they are being educated to perform once they have graduated. There is little evidence that they are better educated in this conventional way than they would be using other approaches better suited to lecturers and students with ADHD.

With respect to research, the process of obtaining funding almost seems designed to disadvantage ADHD-affected researchers. In an attempt to achieve fairness and equity, granting agencies require the completion of lengthy and complex forms with extensive detailed information, much of which requires careful cross-referencing and detailed descriptions of research planned to take place over a period of several years. These tasks may be prohibitively difficult for those with ADHD,[58]

who, in other respects, may be exceptional researchers, and can prevent them from accessing the funds they need to build a successful research career. Far from ensuring equity, these procedures, which may be of little direct relevance to actual research outcomes, represent a form of indirect discrimination against those with ADHD. With an inclination towards divergent thought of the kind that often leads to great breakthroughs,[59]

and a corresponding inability to sustain long-term focus in one area, people with ADHD may be further disadvantaged because long-term success as an academic researcher can depend on the development of a track record of achievement focused in a narrow, specialised field of research.

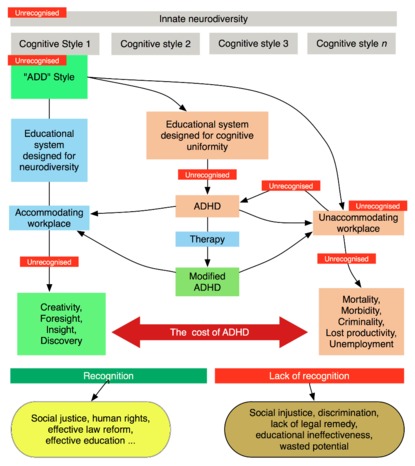

An alternative model of ADHD as part of a broader spectrum of human neurodiversity is illustrated in Figure 2.[60] Humans are seen as having innate psychological heterogeneity, with individual differences in cognitive abilities that are a legacy of our evolutionary past. In this model it is not meaningful to think of ‘normal’ cognitive ability or to measure cognitive ability by a single yardstick.

In this model, ADHD, as a disorder, is seen as resulting from an interaction between a particular component of this neurodiversity — an innate cognitive style — and the social and organisational environment.[61]

In appropriate social and organisational circumstances, this style may be associated with high levels of creative ability,[62]

insight,[63]

a strong desire for adventure, novelty-seeking and discovery,[64]

a high tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity,[65]

and an ability to think holistically.[66]

In this model, ADHD, as a disorder, results when individuals with this cognitive style are prevented from expressing their natural inclinations, are constrained to behave in ways that they find unnatural and painful, and are restrained, disadvantaged or even punished for acting in the ways that come naturally to them. This may occur in school systems that tend to be organised and designed in a one-size-fits-all manner or in workplaces designed along the same lines.

The model illustrated in Figure 2 provides a framework for the respectful treatment of diversity (a foundation of human rights) by removing the need to treat difference as disability (particularly where it is construed as inferior, dangerous or needy). When difference is treated as disability some people run ‘aground on the shoals of the two-track system of legal treatment’ because the ‘special treatment’ they are offered often embodies social and political exclusion.[67] Characterising cognitive differences as deficits addressable through the law concerned with disability can, thus, reinforce rather than alleviate the problems facing those who are different.

The idea that ADHD is part of the spectrum of human neurodiversity that is a legacy of our evolutionary past was proposed by Thom Hartmann,[68] and more formally by Jensen et al.[69] ADHD is not alone among psychiatric conditions and psychological traits in being viewed in this way. Depression,[70] Obsessive Compulsive Disorder,[71] Bipolar Disorder,[72] Schizophrenia,[73] Autism Spectrum Disorders,[74] anxiety disorders,[75] Psychopathy,[76] and personality disorders[77] have all been discussed as manifestations of normal, potentially advantageous variation, made pathological through the influence of social and cultural context.

Evidence for positive attributes of ADHD is hard to find in the medical and psychological literature because it has hardly been looked for.[78] There is, nevertheless, some evidence that ADHD is associated with right-hemisphere bias, creativity, solving problems with insight, self-transcendence and novelty seeking.[79]

In contrast, advantages of ADHD are widely discussed in more popular literature and the published memoirs of people with ADHD, including many in clinical practice.[80]

A good example is the recent book The Gift of Adult ADD,[81] which identifies the five gifts of ADHD as creativity, ecological consciousness, interpersonal intuition, exuberance, and emotional expressivity. Other authors cited earlier identify other, similar characteristics. People with ADHD are portrayed as adventurous,[82]

open to new ideas,[83]

creative,[84]

divergent in their thinking,[85]

tolerant of ambiguity,[86]

able to discern complex patterns and relationships,[87]

exploratory in their behaviour,[88]

able to think holistically,[89]

passionate,[90]

generous,[91]

intense,[92]

intuitive,[93]

imaginative,[94]

insightful,[95]

spontaneous[96]

and humorous.[97]

They may be highly intelligent and appear to have an unusual ability to see patterns and indirect connections,[98]

and to find, with relative ease, solutions to problems that are not obvious to other people.[99]

They are capable of sustaining rare levels of intensity and focus on activities and projects that catch their interest[100]

and they can be infectiously enthusiastic and passionate about those interests.[101]

They can be capable of highly original thought[102]

and they often have a wide range of interests and a great breadth of knowledge.[103]

However, these positive traits and the success they can bring are usually not seen as part of what it means to have ADHD. A person with ADHD is more usually seen as successful despite being affected by ADHD, rather than as a consequence of being affected by it.

The positive attributes associated with ADHD could provide an incentive for workplace change, and measures to reduce discrimination against people with ADHD are also likely to enable their strengths to be more fully developed and utilised, to the overall advantage of the organisation. Just as cognitive diversity was perhaps selectively advantageous to early human groups,[104]

tapping into such diversity in the workplace is likely to improve organisational performance. The other side of what is described in the medical literature as an ‘impairment’ of executive functioning or a biochemical brain disorder may be a creative genius with a ‘richness’ of ‘wandering thoughts’[105]

that can prove invaluable to organisations and to humanity.

This alternative view, that the negative characterisation of ADHD is merely a contextual perspective of otherwise positive attributes, implies a failure by contemporary schools, workplaces and other social settings to adequately accommodate and embrace the attributes of people with ADHD. It raises the question of how people with these attributes can be accommodated, which we discuss in the context of the one area of work-related law that allows for such accommodation: anti-discrimination law.

A significant amount of legal activity and related literature regarding people with ADHD is from the United States, and the greater part of it relates to the treatment by educational authorities of children with ADHD.[106] There has been much less activity in Australia, although the few Australian cases leave no doubt that people with ADHD can bring themselves within the definition of disability in Australian anti-discrimination law. The definition in the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (‘DDA (Cth)’) is broader than in some state and territory legislation,[107] but it is ‘indicative of the general approach’.[108]

The following discussion of disability discrimination in Australia refers principally to the DDA (Cth).

The definition of disability in the DDA (Cth) includes

total or partial loss of the person’s bodily or mental functions … a disorder or malfunction that results in the person learning differently from a person without the disorder or malfunction … [and] a disorder, illness or disease that affects a person’s thought processes, perception of reality, emotions or judgment or that results in disturbed behaviour.[109]

This definition provides protection to as wide a range of people who might be discriminated against for their (actual, past, future or perceived) departure from the norms of human function and behaviour as possible. By way of contrast, the definition in the Equality Act 2010 (UK) c 15 (‘EA (UK)’) is less generous; it is limited to a past or present ‘physical or mental impairment [which] has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on [a person’s] ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities’.[110] The United States Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (‘ADA (US)’) is similarly limited, defining a disabled person as one who has or is regarded as having a ‘physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more [of their] major life activities’.[111] ADHD has previously fallen within the definition of disability in both the United Kingdom[112] and United States legislation, but the scope of coverage in the United States (for all disabilities, not only ADHD) was narrowed by a series of United States Supreme Court decisions which imposed additional considerations such as the availability of corrective measures, and set high standards for the degree of impairment.[113] This trend was addressed by the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, which reinstated the intended breadth of the definition of disability.[114]

Despite its widespread acceptance as a ‘disability’ in Australian anti-discrimination law,[115] ADHD has rarely formed the basis for a discrimination complaint in reported cases.[116] As in the United States, the few reported cases tend to be in relation to the education of children and young people who have ADHD rather than about employment issues concerning adults with ADHD.[117] These may still be relevant to the approach of courts to issues of difference and disability in an employment context.

The small number of complaints of disability discrimination from people with ADHD may reflect both the low level of diagnosis and the need — for the few who are diagnosed — to identify as ‘disabled’. Because the law’s protection is available on the basis of attributes such as race, sex, age and disability, and not ‘at large’ on the basis of prejudice or irrelevant considerations generally,[118] a person with ADHD who is discriminated against because of their different behaviours must be prepared to characterise their having ADHD as a disability. From the perspective of the person with ADHD, attention focuses on their ‘not normal’ behaviour, rather than on the excessively rigid ‘normality’ of the workplace. The law’s attempts to ameliorate this rigidity, through provisions which recognise indirect discrimination and which require adjustments to be made, do not alter the threshold obstacle for a person with ADHD who has to characterise their cognitive function as a disability and take responsibility for challenging the appropriateness of workplace arrangements.

To categorise oneself as having a disability can be a significant step for an adult to take, and it will be a barrier to using disability discrimination legislation for people with ADHD who do not see themselves as disordered, disturbed, malfunctioning, ill or diseased.[119]

Furthermore, the stigmatisation that occurs in childhood persists into adulthood, providing a disincentive for an adult to disclose the fact that they have ADHD. They may be apprehensive that their ADHD diagnosis will be treated as insignificant, or viewed as an attempt to gain undue access to special treatment or conditions, and so not rely on it to claim the protection of anti-discrimination law. However, as the law currently stands, it is necessary to use a disability framework to address how well anti-discrimination law operates to protect people with ADHD. We will first consider the current operation of anti-discrimination law, before we consider alternatives based on difference rather than disability.

The approach to direct discrimination in the DDA (Cth) (addressing formal inequality or disparate treatment) is typical of anti-discrimination laws in Australia. It relies on a ‘comparator’ test, proscribing treatment of a person with a disability when it is less favourable than treatment of a person without that disability in the same or similar circumstances.[120] As a result of the High Court of Australia’s decision in Purvis v New South Wales (‘Purvis’),[121] direct discrimination has been narrowed to be, effectively, protection against outright prejudice:[122] ‘blanket exclusions and the most blatant forms of discrimination.’[123] As a result, the DDA (Cth) proscribes less favourable treatment only when it occurs because of the fact that the person has ADHD. If, as is far more likely, a person is subjected to less favourable treatment because of a behavioural manifestation of ADHD, then the behaviour, not ADHD itself, is said to be the cause of the conduct and so is not covered by the DDA (Cth).

The effect of Purvis is to separate the fact of a disability from its behavioural manifestation, a quite artificial exercise in the case of people with ADHD. This artificiality was apparent in the facts of Purvis, where the person in question had an acquired brain injury. McHugh and Kirby JJ in dissent observed that this was a ‘hidden impairment’ which ‘is not externally apparent unless and until it results in a disability’.[124] Of the person with a disability in Purvis,[125] they said:

It is his inability to control his behaviour, rather than the underlying disorder, that inhibits his ability to function in the same way as a non-disabled person in areas covered by the Act, and gives rise to the potential for adverse treatment. To interpret the definition of ‘disability’ as referring only to the underlying disorder undermines the utility of the discrimination prohibition in the case of hidden impairment.[126]

This was, however, a minority view, and, as a result of the majority reasoning in Purvis,[127] the ‘comparator’ test fails people with ADHD; they are treated in the same way as people without it.[128] In Ware v OAMPS,[129] for example, Mr Ware was an adult in employment who had ADHD. He was dismissed, and complained of discrimination on the ground of his having ADHD. The Court, following Purvis, found that for these purposes, the appropriate comparator was:

(a) an employee of OAMPS having a position and responsibilities equivalent of those of Mr Ware;

(b) who did not have attention deficit disorder or depression; and

(c) who exhibited the same behaviours as Mr Ware, namely poor interpersonal relations, periodic alcohol abuse and periodic absences from the workplace, some serious neglect of duties and declining work performance, but with a formerly high work ethic and a formerly good work history.[130]

This highlights the very limiting effect of Purvis: it is quite unrealistic to read both (b) and (c) together and to suggest that all the behavioural manifestations of ADHD would be found in someone without ADHD. Unsurprisingly, the Court found that Mr Ware was not discriminated against because ‘[t]he hypothetical comparator in the same circumstances would [also] have been dismissed’.[131] The Court’s further analysis led it to conclude that another incident did amount to direct discrimination,[132] but the reasoning is unsatisfactory in not identifying a comparator and confused in identifying an unlawful basis for the conduct.

The effect of Purvis has been to limit the direct discrimination provisions of the DDA (Cth) to circumstances where an employer discriminates against a person for the fact that they have ADHD. Such circumstances rarely occur. Rather, an employer acts on the basis of the way a person with ADHD behaves, and acts in the same way when the same behaviours are exhibited by employees without ADHD. An employer may, for example, expect people with ADHD to process information in an open plan environment just like their ‘normal’ peers and, like their ‘normal’ peers, they are disciplined if production targets are not met. On this approach, the reason for the disciplinary action is non-performance, and a person with ADHD is being treated in the same way as anyone else who fails to perform, without recognising the underlying reason for that non-performance. However, in these circumstances, provisions which protect against indirect discrimination may apply.

More often than being subject to direct prejudice, however, a person with ADHD has difficulty conforming to workplace requirements because of associated behaviours. They then have access to a remedy for indirect discrimination.

The limitations of remedying only formal inequality are well-recognised,[133]

but anti-discrimination laws also address indirect discrimination (substantive inequality, or disparate impact), which occurs where a requirement that is unreasonable in the circumstances is imposed on everyone but has a disproportionately adverse effect on some. The precise formulation of the test for indirect discrimination varies, but it is essentially the same among Australia’s anti-discrimination laws,[134] except under the DDA (Cth) since the amendments to s 6 in 2009.[135]

In Australian anti-discrimination legislation apart from the DDA (Cth), the usual formulation identifies an unreasonable requirement or condition with which people with ADHD cannot comply, and asks whether or not a substantially higher proportion of people without ADHD would be able to comply with it. Similarly, in the United States, the ADA (US) test addresses circumstances where ‘standards, criteria, or methods of administration … have the effect of discrimination on the basis of disability’,[136] and the EA (UK) addresses circumstances where an employer’s conduct, the physical features of the premises, or the absence of an auxiliary aid, ‘puts a disabled person at a substantial disadvantage … in comparison with persons who are not disabled’.[137]

People with ADHD can often point to a workplace requirement or condition with which they cannot comply (where non-compliance is construed liberally, and in a practical sense[138]

) which is unreasonable in the circumstances. Assuming that they are willing to identify as having a disability, people with ADHD are substantially dependent on indirect discrimination provisions to remedy discriminatory treatment in the workplace.

Under the amended DDA (Cth), the notoriously difficult[139]

‘substantially higher proportion’ (disparate impact) test for indirect discrimination has been removed. Whether people without the particular disability can comply and, if any, what proportion can comply, is no longer a consideration. Instead, the DDA (Cth) is concerned with a requirement or condition, unreasonable in the circumstances, with which a person with ADHD cannot comply and which ‘has, or is likely to have, the effect of disadvantaging persons with the disability’.[140] The virtue of this approach, recommended by the Productivity Commission in its report on the DDA (Cth),[141] is that a person with ADHD has to prove only that they themselves cannot comply with the requirement and are disadvantaged by it.

The DDA (Cth) retains, however, the ‘reasonableness of the requirement’ test that features in all Australian anti-discrimination legislation, and it remains an obstacle for people with ADHD. The type of requirement that will disadvantage a person with ADHD is likely to be one that is a ‘normal’ requirement in the circumstances, such as timely performance of ordinary workplace tasks. In B v Queensland Nursing Council, for example, the requirement complained of was a condition which was imposed in the course of registration under the Nursing Act 1992 (Qld).[142] The nurse had ADHD, and the imposed condition — that she not be employed where she would have patient contact — was imposed to ensure ‘sound, efficient and safe nursing’. In very brief reasons, the Tribunal set out the negative aspects of the nurse’s ADHD-related behaviour and dismissed her claim for two reasons: first, the provisions in the later Nursing Act 1992 (Qld) were said to be inconsistent with — and to that extent to impliedly repeal — the Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Qld); and secondly, as a matter of discretion.[143] It could be inferred from the Tribunal’s listing of the nurse’s negative behaviours that it considered the imposed requirement was reasonable in the circumstances.[144] Similarly, in Ware v OAMPS,[145] the Court’s decision to dismiss the indirect discrimination claim, although cursory and unclear, suggests that a requirement that Mr Ware work to specified standards was considered a ‘reasonable’ one in the circumstances.

Observations by the Western Australian Industrial Relations Commission in CEPU v Western Power clearly indicate how an employee with ADHD can fail in a discrimination complaint because the requirement that he or she perform to a normal or usual standard is considered reasonable in the circumstances.[146] The Tribunal observed that:

The question of Mr Murphy’s inadequate attention and retention of instruction and information are recurring themes in the assessments. One might expect some difficulty on the part of Mr Murphy given his condition of attention deficit disorder. Albeit this cannot be used as an excuse for not working properly. … The evidence when taken as a whole is that Mr Murphy … [was] an underperforming employee.[147]

The Commission was of the view that ‘suffer[ing] from ADD … cannot be seen as an excuse for inadequate performance or adherence to work procedures’.[148]

Under Australian anti-discrimination laws generally, and the DDA (Cth) as it stood before the 2009 amendments,[149] an employer is obliged to provide such facilities as would enable an employee to carry out the inherent requirements of the job, unless to do so would be onerous or cause unjustifiable hardship.[150] To the extent that such a provision operates as an obligation on an employer to accommodate (or ‘make adjustment for’) the employment needs of a person with ADHD, it is substantially ineffective, and none of the few ADHD employment discrimination cases has had occasion to consider this obligation.

The obligation to accommodate is implicit in anti-discrimination legislation.[151] It is ‘embedded within the indirect discrimination provisions’[152]

and arises when an employer relies on the defence of hardship or ‘onerousness’ in making adjustments to enable the person to carry out the inherent requirements of a job.[153] The principal reason for its marginal relevance to a person with ADHD is that it arises only when a person is unable to carry out a job’s inherent requirements. That is often not the case for a person with ADHD. While it might have been so in B v Queensland Nursing Council it was clearly not the case in CEPU v Western Power and Ware v OAMPS where, as is more commonly the case, the issue was one of adequate performance of a job, not inability to carry out its inherent requirements. Thus, before the 2009 amendments to the DDA (Cth),[154]

a person with ADHD had no statutory basis for expecting an employer to make adjustments to the workplace that would enable them to perform better in meeting the ‘normal’ requirements of their job than their ADHD would allow. That continues to be the case under Australia’s state and territory anti-discrimination laws,[155]

but the DDA (Cth) has taken a new approach.

The DDA (Cth) amendments reflect a recommendation from the Productivity Commission[156]

in explicitly imposing on an employer an obligation to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ that would enable a person with a disability — such as ADHD — to comply with a requirement.[157] A ‘reasonable adjustment’ is defined simply as one that would not impose ‘an unjustifiable hardship’ on, in the case of a workplace requirement, the employer.[158] For people with ADHD, the significance of the amendment is that an employer’s obligation to make reasonable adjustments is no longer dependent on a person’s inability otherwise to carry out the inherent requirements of a job. In the state and territory discrimination laws[159]

there is a necessary nexus between the implied obligation to make adjustments and ability to perform inherent requirements,[160] and under the DDA (Cth) there remains a connection when in fact a person is not able to perform the inherent requirement.[161] But when the issue is how well and in what way they do their job (as it often is for people with ADHD), the DDA (Cth) now obliges an employer to accommodate a person’s needs, unless that accommodation imposes unjustifiable hardship.[162]

In legislating for ‘reasonable adjustments’ in employment, the federal government is giving effect to its obligation under art 27(1)(i) of the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (‘CRPD’)[163] to ‘[e]nsure that reasonable accommodation is provided to persons with disabilities in the workplace’.[164]

It is also moving the DDA (Cth) closer to international practice. The provisions in the EA (UK) impose a positive obligation on an employer to ‘take such steps as it is reasonable to have to take’ to avoid causing a disabled person substantial disadvantage,[165] and in the ADA (US) there is a positive obligation to make ‘reasonable accommodation’ for a person’s disabilities short of causing ‘undue hardship’.[166] There is now an obligation on all member states of the European Union to require employers to ‘take appropriate measures … unless such measures would impose a disproportionate burden on the employer.’[167]

The Explanatory Memorandum accompanying the 2009 amendments claims that the DDA (Cth), in defining ‘reasonable adjustments’ as adjustments that would not impose an unjustifiable hardship, ‘is consistent with the definition of “reasonable accommodation” in Article 2 of the Disabilities Convention.’[168] This is not strictly true. The CRPD definition is different, referring not to ‘unjustifiable hardship’ but to ‘disproportionate or undue burden’, and specifying that reasonable accommodation

means necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.[169]

Allowance for reasonable accommodation does, however, have a problematic dimension. The DDA (Cth), and the statutes in the United Kingdom and the United States (and their judicial interpretation), have been founded on notions of cost in construing what is reasonable and unreasonable. Colker, for example, in discussing provisions now in the EA (UK) which were previously in the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (UK) c 50, comments that:

By being attentive to costs and offering a narrow scope of reasonable accommodation, it would appear that the British model is deferential to the needs of employers in a capitalistic society, reflecting a conservative political regime.[170]

Where Australian courts will turn to better understand the scope and content of ‘reasonable adjustments’ is not clear. On the one hand, the drafting of the DDA (Cth) has a closer connection with the very open approach of the CRPD, the United Kingdom Equality and Human Rights Commission publishes ‘guidance documents’ to explain and illustrate factors in assessing what constitutes reasonable adjustments[171] and regulations under the recently enacted EA (UK) can prescribe matters to be taken into account in deciding whether a step is reasonable to take.[172] On the other hand, the ADA (US) takes a pragmatic approach, defining reasonable accommodation to include

job restructuring, part-time or modified work schedules, reassignment to a vacant position, acquisition or modification of equipment or devices, appropriate adjustment or modifications of examinations, training materials or policies, the provision of qualified readers or interpreters, and other similar accommodations for individuals with disabilities.[173]

But the duty to make accommodation has been interpreted narrowly in the United States,[174]

in much the same way that the very definition of disability has been interpreted more narrowly over the years.[175]

The conservative approach to disability discrimination legislation in the United States flags an unexplored issue in Australia that could limit the protection available to people with ADHD: how is the ‘reasonableness’ of an adjustment measured?

While the obligation to make adjustment under the DDA (Cth) is imposed on the employer, it may be that its ‘reasonableness’ turns in part on steps that the employee takes to mitigate the extent to which an adjustment is required. The very open definition in the DDA (Cth) shifts the ‘reasonableness’ inquiry to the extent of unjustifiable hardship caused to an employer, the inclusive definition of which does not explicitly refer to any expected mitigating conduct on the part of an employee.[176] Clearly, the intention of an accommodation provision is that ‘workplaces must … be adjusted so that they reasonably accommodate workers with disabilities in order to ensure equal effective access to the right to work’,[177] but United States jurisprudence raises the prospect that mitigating conduct on the part of an employee may be a factor when taking into account ‘all relevant circumstances of the particular case’.[178] In Sutton v United Air Lines, the Court took into account the ability of a person to correct myopia in deciding that they were not ‘disabled’;[179] similar reasoning could suggest that the reasonableness of a measure an employer must take to accommodate a person with ADHD is circumscribed by the person’s own willingness to take medication.

A troubling consequence of such an approach could be an expectation that, as part of an assessment of the reasonableness of measures required to accommodate their needs, a person with ADHD will medicate. It has been observed already in Australian law that an employer had less reason for concern about the performance of a person with ADHD when the person was on medication.[180]

As the previous section illustrates, anti-discrimination law places ADHD firmly in a disability framework, premised on the idea of deficit relative to a norm. Direct discrimination is defined in comparative terms, and indirect discrimination turns on the objective reasonableness of a requirement. Whether directly or indirectly, the conceptual approach is to compare a person who has a disability with a person who does not, or against a standard that is ‘objectively’ reasonable. The overall approach is concerned with compensating for departure from the way people are usually treated. The attributes of the people whose treatment is usual in employment in Australia become the standard against which discrimination is measured. The comparison is a negative one, and the law anticipates that people with an attribute that differs from the norm will suffer for it. In this way, disability discrimination laws operate to protect, not to promote — they endorse a positive view of difference only indirectly, by reprimanding those who take a negative view of it.

Legislation that prohibits discrimination on the ground of, say, race or sex is designed to negate the relevance of a particular race or particular sex, and to promote equal, non-differential treatment. The terms used — ‘race’ and ‘sex’ — are themselves all-embracing, identifying a conceptual area within which discrimination is proscribed. When a person complains of sex discrimination they identify as having a particular sex, and they say that they have been treated differently because of it. Disability discrimination provisions start from a fundamentally different position, where the term used — disability — immediately establishes a deficit or failing as compared to ‘ability’. Disability is not a conceptual area within which discrimination is proscribed; it is, rather, the status of being less than ‘able’. The very terms of the protection are presumptively negative; at the outset they are concerned with protecting the different status of disability, rather than gaining acceptance for a different ability.

There is a limit to how far legislative protection of a person’s different ability can be compared to legislative protection of a person’s different race:[181] quite simply, there will be employment requirements a person cannot meet because of their different ability while the same can rarely if ever be said of a person because of their different race. This understanding is already reflected in provisions for sex discrimination: while anti-discrimination law can promote racial equality without qualification, it cannot and does not do so for sexual equality, where some concession is made for, say, a woman’s strength, stamina or physique being less than a man’s in sporting competitions.[182] Nevertheless, sex discrimination legislation starts from a point of equality, where a person’s sex is not a relevant consideration unless circumstances require it to be taken into account. In contrast, disability discrimination legislation starts from a point of presumed inequality, where a person’s disability — their departure from a norm — is the relevant consideration.

A consequence of this approach is that in the area of a person’s abilities, anti-discrimination laws confirm broad majority/non-majority distinctions in a way that they do not for attributes such as race and sex. Instead of celebrating this aspect of social heterogeneity and promoting the different opportunities offered by people of different abilities, anti-discrimination laws implicitly confirm a person’s status as ‘in’ or ‘out’ of a limited conception of ability, and offer Minow’s ‘two-track’ legal system of special treatment[183]

to protect people with disability from the disadvantage they will inevitably suffer. In this way, being differently abled is seen as a disadvantage to be remedied rather than a diversity to be celebrated.

When differences are so characterised and explicitly recognised, there is an implication that whatever stigma attaches to them has a valid basis. As a result, reception of ADHD in Australian law and the workplace involves a conundrum: a person with ADHD has little choice but to seek protection as a person who is inherently defective, rather than as a person who is presumed to be equal in the same way that people are presumptively equal regardless of their sex, ethnicity or sexual affinity.

This characterisation of anti-discrimination measures as a means of redressing disability, rather than as a way of accommodating different abilities, is underpinned by international human right covenants. The CRPD defines ‘discrimination on the basis of disability’ as:

any distinction, exclusion or restriction on the basis of disability which has the purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal basis with others, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.[184]

This is in terms similar to the definition in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[185] International human rights instruments are consistent, therefore, in formalising principles of non-discrimination and equality as a protective approach to disadvantage. Perhaps it is the authoritative nature of human right covenants that sees the vast literature in the field pervaded by the same language, which accepts, as its starting point, the need to protect disability as a departure from a norm of ability.[186]

An alternative approach is possible. The proposition we explored above, that neurodiversity is an essential aspect of human nature, implies that neurodiversity ought to be recognised in a pluralist liberal democratic state, alongside recognised diversity of other attributes such as political affiliation, sexual affinity, gender, religious faith, and ethnicity.[187] Thus, we argue that there is a need for legal remedies that treat attributes such as those associated with ADHD as features of cognitive diversity rather than as a disability. If there is unfair treatment in the workplace, it should be addressed within a framework of neurodiversity that recognises people as differently ‘abled’, rather than as disabled, just as it currently recognises people as differently gendered or as having different cultural backgrounds.

On this approach, the same provision for reasonable adjustments could be made from a different starting point, one that recognises people’s different cognitive styles without characterising the difference as disability. In the spirit of Australia’s approach to creating parallel anti-discrimination legislation for different attributes (eg ‘race’,[188] ‘sex’,[189] and ‘age’[190]), legislation can identify the relevant attribute as ‘ability’. Provisions concerned with ‘ability discrimination’ would start from a point of equality, where a person’s ability is presumed to not be a relevant consideration unless circumstances require it to be taken into account. A person with ADHD would not present as an employee with a ‘problem’, but as an employee with abilities. If and when the person’s abilities made work performance difficult, then, and not until then, would questions of reasonably accommodating different abilities arise. For some people that point would be reached quite quickly, even before employment commences, because of the immediate and significant degree to which their abilities make work performance difficult, if not impossible. For others, such as people with ADHD, that point would arise much later if at all.

When that point is reached, it is time for an employer to make such adjustments as are reasonable to enable a person to carry out the job. The obligation in the DDA (Cth) to make reasonable adjustments in the workplace[191]

is a significant step towards recognising a person’s ability. But even this advance comes from a starting point of dealing with a disability, where the adjustments will represent some mediated departure from the ‘normal’ way of doing things. If the starting point were, instead, to engage diverse abilities, then the ‘reasonable adjustments’ would be to accommodate diversity, rather than to compensate for disability. Conceptually and practically, people with ADHD would not be forced to identify as disabled but would be able to claim their own identity as differently abled. A legislative change such as this, if accompanied by improved understanding of cognitive- and neurodiversity, and of the differential effects of standard workplace practices, might go some way to ameliorating the silent but pervasive discrimination experienced in the workplace by many people with cognitive differences such as those associated with ADHD.

In this article we have used the example of ADHD to argue for a legal framework to address workplace discrimination against neuro-cognitive difference that is based on diversity rather than disability. However, legislative change alone is unlikely to be effective in changing the way people with cognitive differences are treated in the workplace. The limitations of legislation in effecting social change, well-documented in other areas,[192] will apply equally here. Prejudice is reinforced by attitudes about ‘normality’, and attitudes cannot always be reformed by legislation.

A change in language is also unlikely, on its own, to be effective. Bailey believes that the term ‘capacity’, as an alternative to ‘disability’, for example, would ‘almost inevitably be coupled with “limited” or another qualifier.’[193] However, the legislative changes we advocate need to be seen in the context of broader trends of organisational change. Other factors are operating to cause workplaces to evolve in a direction that is more accommodating of diversity. This trend provides impetus to the proposed legislative change and makes its effectiveness more likely.

The workplace is now more diverse than it was in the past[194] and a one-size-fits-all approach to management is no longer seen as appropriate.[195] Organisations increasingly recognise the need to create workplace practices and organisational cultures that embrace diversity.[196] This trend is in part a response to legal obligations, but it is also driven by a practical need to accommodate people from a wider range of backgrounds who make up the modern workforce, and, in some instances, it has been developed as a strategic approach to increasing performance.[197] At the same time, increasing knowledge of the nature of human neuro-cognitive diversity[198]

and theoretical work demonstrating that diversity can be more beneficial to group performance than high levels of individual ability[199]

provide further impetus for the continuation of this trend. There is also good evidence that it works — appropriate implementation of diversity policies in relation to sex and race can result in improved organisational performance.[200]

We have used the academic workplace to illustrate how individuals with a particular cognitive ability (ADHD) can experience indirect discrimination. Universities have undergone profound change in recent decades[201] and, as in other kinds of work, a one-size-fits-all approach to higher education and research management no longer seems appropriate. With the right incentives, including the need for legislative compliance, the goal of more inclusive approaches that recognise, celebrate, reward and enhance the contributions of people with different kinds of neuro-cognitive ability is not unrealistic.

But academic workplaces are far from typical, and the question arises as to whether other kinds of workplaces could be similarly adjusted to accommodate neuro-cognitive diversity. It could be argued, for example, that some forms of work are inherently repetitive and dull, making them unsuitable for people with ADHD. However, routine work is being increasingly mechanised and automated, and forms of work that once appeared routine, such as car assembly, have been made more interesting, providing outlets for creative activity and resulting in higher workforce participation and improved production outcomes.[202] In the same way that many employers have had to redefine normal working hours and reconsider what had long been believed to be the need for full-time workers, workplaces ought now to re-evaluate other employment conditions and inherent requirements which are currently seen as normal and necessary.

Thus, while legislative change is unlikely to be effective on its own, in the context of current trends in workplace change, it may be a crucial element in a shift towards workplaces that embrace the advantages of diverse cognitive abilities resulting in both better treatment of employees and improved performance of organisations.

Figure 1 depicts the conventional view of ADHD as a neuro-cognitive developmental disorder with deficits (impulsivity, poor attention, etc) that distinguish it from typical cognitive performance. If untreated, these give rise to educational disabilities, poor functioning in the workplace, increased risk of other social and psychiatric disorders, criminal behaviour, chronic illness and early death. ADHD is viewed as a defect and its cause is located in genes and developmental processes.

Figure 2 depicts an alternative model of ADHD that assumes that neurodiversity is an essential aspect of human nature. Impairment associated with ADHD arises from a failure of educational systems and workplaces to recognise and accommodate a form of cognitive ability which, under the right circumstances, results in high levels of creative thought, adventurous behaviour, etc. In addition to the currently recognised costs of ADHD, this failure represents a waste of potential. It constitutes an unrecognised form of discrimination and social injustice. Paradoxically, in this model, recognition of difference, which is often the basis of stigma and discrimination, is necessary for the achievement of social justice.

[*] JD (Canberra); Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Canberra.

[**] BA (SUNY Binghampton), MA, PhD (Pittsburgh); Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Canberra.

[†] BSc (St Andrews), PhD (Griffith), MBA (ANU); Deputy Director, John Curtin School of Medical Research, The Australian National University.

[‡] BA, LLB, MEd (UNSW); Associate Professor, ANU College of Law, The Australian National University; Director, Law Reform & Social Justice, ANU College of Law, The Australian National University. Authors are listed alphabetically as this article represents a cross-disciplinary collaboration to which they made distinctly different kinds of contributions.

[1] See, eg, Mark Rapley, The Social Construction of Intellectual Disability (Cambridge University Press, 2004) 62–5; Judith Lorber, ‘“Night to His Day”: The Social Construction of Gender’ in Judith Lorber (ed), Paradoxes of Gender (Yale University Press, 1994) 13.

[2] See generally, Patricia Easteal, Less Than Equal: Women and the Australian Legal System (Butterworths, 2001) 7.

[3] Patricia Easteal, ‘Setting the Stage: The “Iceberg” Jigsaw Puzzle’ in Patricia Easteal (ed), Women and the Law in Australia (LexisNexis Butterworths, 2010) 1, 16–18.

[4] Neil Rees, Katherine Lindsay and Simon Rice, Australian Anti-Discrimination Law: Text, Cases and Materials (Federation Press, 2008) 122, quoting Rosemary Hunter, Indirect Discrimination in the Workplace (Federation Press, 1992) 5–6.

[5] Rick Mayes, Catherine Bagwell and Jennifer Erkulwater, Medicating Children: ADHD and Pediatric Mental Health (Harvard University Press, 2009) 101, quoting Frank Bowe, Handicapping America: Barriers to Disabled People (Harper & Row, 1978) 224.

[6] See generally Patricia Easteal, ‘A Kaleidoscope View of Law and Culture: The Australian Sex Discrimination Act 1984’ (2001) 29 International Journal of the Sociology of Law 51.

[7] See Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Social Trends, ABS Catalogue No 4102.0 (2008) <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Chapter8002008> Rebecca Cassells et al, The Impact of a Sustained Gender Wage Gap on the Australian Economy: Report to the Office for Women, Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2009) <http://www.fahcsia.gov.au/sa/women/pubs/general/gender_wage_gap/Pages/p2.

aspx#2>.

[8] See, eg, Escobar v Rainbow Printing Pty Ltd [No 2] [2002] FMCA 122; (2002) 120 IR 84; Mayer v Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation [2003] FMCA 209; [2003] EOC 93-285; Edwards v Hillier [2006] QADT 34 (11 August 2006).

[9] Edward M Hallowell and John J Ratey, Delivered from Distraction: Getting the Most out of Life with Attention Deficit Disorder (Ballantine Books, 2005) suggests the term ‘Attention Difference Disorder’, pointing out that people with ADHD can sustain high levels of attention (hyper-focus) for prolonged periods of time under some circumstances, as we discuss below.

[10] Here we use the term ‘ADHD’ for consistency with the clinical literature, recognising that this may be misleading when referring to adults and that, contrary to the aims of this article, it reinforces the view of ADHD as a disability characterised by deficit. As points of entry into the large medical and psychological literature on ADHD/ADD, see eg, Russell A Barkley, ADHD and the Nature of Self-Control (Guilford Press, 1997); Thomas E Brown, Attention Deficit Disorder: The Unfocused Mind in Children and Adults (Yale University Press, 2005); Russell A Barkley, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment (Guilford Press, 3rd ed, 2006); Michael Fitzgerald, Mark Bellgrove and Michael Gill (eds), Handbook of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (John Wiley & Sons, 2007); Mayes, Bagwell and Erkulwater, above n 5; Russell A Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults: The Latest Assessment and Treatment Strategies (Jones and Bartlett, 2010). For general discussion of neurodiversity and diverse cognitive styles, see, eg, Kenneth M Goldstein and Sheldon Blackman, Cognitive Style: Five Approaches and Relevant Research (John Wiley & Sons, 1978); Raymond G Hunt et al, ‘Cognitive Style and Decision Making’ (1989) 44 Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 436; Robert J Sternberg and Li-Fang Zhang (eds), Perspectives on Thinking, Learning, and Cognitive Styles (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001); Andreas Kapardis, Psychology and Law: A Critical Introduction (Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed, 2003); Developmental Adult Neuro-Diversity Association, The Make-Up of Neurodiversity (2010) <http://www.danda.org.uk/pages/neuro-diversity.php> Edward Griffin and David Pollak, ‘Student Experiences of Neurodiversity in Higher Education: Insights from the BRAINHE Project’ (2009) 15 Dyslexia 23; David Pollak, ‘Introduction’ in David Pollak (ed), Neurodiversity in Higher Education: Positive Responses to Specific Learning Differences (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009) 1; Scott E Page, The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies (Princeton University Press, 2007).

[11] American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR (4th ed, 2000) (‘DSM-IV’).

[12] Joseph Biederman and Stephen V Faraone, ‘Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder’ (2005) 366 Lancet 237, 237.

[13] Ibid. See also Brown, Attention Deficit Disorder: The Unfocused Mind, above n 10; Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10.

[14] See, eg, William J Barbaresi et al, ‘How Common Is Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder? Incidence in a Population-Based Birth Cohort in Rochester, Minnesota’ (2002) 156 Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine 217; Tanya E Froehlich et al, ‘Prevalence, Recognition, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in a National Sample of US Children’ (2007) 161 Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine 857; Susan L Smalley et al, ‘Prevalence and Psychiatric Comorbidity of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in an Adolescent Finnish Population’ (2007) 46 Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1575.

[15] See J Fayyad et al, ‘Cross-National Prevalence and Correlates of Adult Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder’ (2007) 190 British Journal of Psychiatry 402, 405.

[16] Biederman and Faraone, above n 12, 239.

[17] Ibid 239–40.

[18] Ibid 239, 241.

[20] See, eg, Thomas Brown, Brown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scales for Adolescents and Adults (Psychological Corporation, 2001); C Keith Conners, Drew Erhardt and Elizabeth Sparrow, Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales (Multi-Health Systems, 1998); Barkley, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook, above n 10.

[21] See, eg, Barkley, ADHD and the Nature of Self-Control, above n 10; Barkley, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook, above n 10; Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10; Brown, Attention Deficit Disorder: The Unfocused Mind, above n 10; Fitzgerald, Bellgrove and Gill, above n 10; Mayes, Bagwell and Erkulwater, above n 5.

[22] See Daniel F Connor et al, ‘Correlates of Comorbid Psychopathology in Children with ADHD’ (2003) 42 Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 193; Ronald C Kessler et al, ‘Patterns and Predictors of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Persistence into Adulthood: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication’ (2005) 57 Biological Psychiatry 1442.

[23] Thomas E Brown, ‘Developmental Complexities of Attentional Disorders’ in Thomas E Brown (ed), ADHD Comorbidities: Handbook for ADHD Complications in Children and Adults (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009) 3, 4.

[24] See Connor et al, above n 22; Kessler et al, ‘Patterns and Predictors’, above n 22; Russell A Barkley, Kevin R Murphy and Mariellen Fischer, ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says (Guilford Press, 2008); Fayyad et al, above n 15, 405; Ronald C Kessler et al, ‘The Prevalence and Correlates of Adult ADHD in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication’ (2006) 163 American Journal of Psychiatry 716; Stephen L Able et al, ‘Functional and Psychosocial Impairment in Adults with Undiagnosed ADHD’ (2007) 37 Psychological Medicine 97; Joseph Biederman et al, ‘Functional Impairments in Adults with Self-Reports of Diagnosed ADHD: A Controlled Study of 1001 Adults in the Community’ (2006) 67 Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 524; Smalley et al, above n 14.

[25] See Thomas E Brown (ed), ADHD Comorbidities: Handbook for ADHD Complications in Children and Adults (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009); Barkley, Murphy and Fischer, above n 24; Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10; Megan A Davidson, ‘ADHD in Adults: A Review of the Literature’ (2008) 11 Journal of Attention Disorders 628; Biederman and Faraone, above n 12, 237.

[26] Molly E Waring and Kate L Lapane, ‘Overweight in Children and Adolescents in Relation to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Results from a National Sample’ (2008) 122 Pediatrics e1; Sherry L Pagoto et al, ‘Association between Adult Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Obesity in the US Population’ (2008) 17 Obesity 539; L A Adler et al, ‘Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Adult Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Is ADHD a Vulnerability Factor?’ (2004) 8 Journal of Attention Disorders 11; Sharon K Farber, ‘The Last Word: The Comorbidity of Eating Disorders and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder’ (2010) 18 Eating Disorders 81.

[27] See Able et al, above n 24.

[28] Michael Rösler et al, ‘Prevalence of Attention Deficit-/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Comorbid Disorders in Young Male Prison Inmates’ (2004) 254 European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience 365.

[29] Figure 1 appears in the Appendix to this article.

[30] There is extensive evidence of educational underperformance by students with ADHD, including lower grades, more failures, more repeated school years, greater need for tutoring and special educational services, lower graduation rates and more suspensions from school. See Barkley, Murphy and Fischer, above n 24; Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10.

[31] Compared to adults without ADHD, those with ADHD are more likely to lose their jobs, change jobs more frequently, relate less well to supervisors, are less likely to be employed, are more likely to be subjected to disciplinary action, are more likely to be absent or underperform, have lower job status and earn less money. See R de Graaf et al, ‘The Prevalence and Effects of Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) on the Performance of Workers: Results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative’ (2008) 65 Occupational and Environmental Medicine 835; Joseph Biederman et al, ‘Educational and Occupational Underattainment in Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Controlled Study’ (2008) 69 Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1217; Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10.

[32] See Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10.

[33] Thomas E Brown, ‘DSM-IV: ADHD and Executive Function Impairments’ (2002) 2 Advanced Studies in Medicine 910; Kathleen G Nadeau, ADD in the Workplace: Choices, Changes and Challenges (Routledge, 1997).

[34] Brown, ‘Developmental Complexities’, above n 23, 5; Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10.

[35] Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10, 1–9; Nadeau, above n 33.

[36] See Michele Toner, Thomas O’Donoghue and Stephen Houghton, ‘Living in Chaos and Striving for Control: How Adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Deal with Their Disorder’ (2006) 53 International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 247; Barkley, Murphy and Fischer, above n 24; Russell A Barkley et al, ‘Young Adult Outcome of Hyperactive Children: Adaptive Functioning in Major Life Activities’ (2006) 45 Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 192; Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10.

[37] See Toner, O’Donoghue and Houghton, above n 36; Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10; Barkley, Murphy and Fischer, above n 24.

[38] See Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10; Barkley et al, ‘Young Adult Outcome of Hyperactive Children’, above n 36.

[39] Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10; Barkley et al, ‘Young Adult Outcome of Hyperactive Children’, above n 36.

[40] See Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10; Barkley et al, ‘Young Adult Outcome of Hyperactive Children’, above n 36; de Graaf et al, above n 31; R C Kessler et al, ‘The Prevalence and Workplace Costs of Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in a Large Manufacturing Firm’ (2009) 39 Psychological Medicine 137.

[41] See Barkley, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults, above n 10; Barkley et al, ‘Young Adult Outcome of Hyperactive Children’, above n 36; Kessler et al, ‘The Prevalence and Correlates of Adult ADHD in the United States’, above n 24; Able et al, above n 24; Biederman et al, ‘Functional Impairments in Adults’, above n 24.

[42] See de Graaf et al, above n 31; Kessler et al, ‘The Prevalence and Workplace Costs of Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder’, above n 40; Barkley et al, ‘Young Adult Outcome of Hyperactive Children’, above n 36; Barkley, Murphy and Fischer, above n 24; Biederman et al, ‘Educational and Occupational Underattainment’, above n 31.

[43] See Kessler et al, ‘The Prevalence and Workplace Costs of Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder’, above n 40.

[44] See Biederman et al, ‘Educational and Occupational Underattainment’, above n 31.

[45] See Biederman et al, ‘Functional Impairments in Adults’, above n 24.

[46] See Graeme H Coetzer and Lynn Richmond, ‘An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between Adult Attention Deficit and Efficacy for Working in Teams’ (2007) 13 Team Performance Management 5; Graeme H Coetzer and Richard Trimble, ‘An Empirical Examination of the Relationships between Adult Attention Deficit, Reliance on Team Mates and Team Member Performance’ (2009) 15 Team Performance Management 78.

[47] See, eg, the discussion of expectations of ‘normal’ behaviour from a person who ‘does not look different’ in Martha C Nussbaum, Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership (Belknap Press, 2006) 206.

[48] Axelrod v Phillips Academy, 46 F Supp 2d 72, 74 (Harrington J) (Mass, 1999), cited in Kristen L Aggeler, ‘Is ADHD a “Handy Excuse”?: Remedying Judicial Bias against ADHD’ (2000) 68 University of Missouri-Kansas City Law Review 459, 459.