Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

RON LEVY[∗]

[This work provides comparative insights into how deliberation on proposed constitutional amendments might be more effectively pursued. It reports on a new nationwide survey of public attitudes to constitutional reform, examining the potential in Australia of innovative Canadian models of reform led by Citizens’ Assemblies. Assembly members are selected at random and are demographically representative of the wider public. They deliberate over reforms for several months while receiving instruction from experts in relevant fields. Members thus become ‘public-experts’: citizens who stand in for the wider public but are versed in constitutional fundamentals. The author finds striking empirical evidence that, if applied in the Australian context, public trust would be substantially greater for Citizens’ Assemblies compared with traditional processes of change. The article sets these results in context, reading the Assemblies against theories of deliberative democracy and public trust. One reason for greater public trust in the Assemblies’ may be an ability to accommodate key values that are otherwise in conflict: majoritarian democratic legitimacy, on the one hand, and fair and well-informed (or ‘deliberatively rational’) decision-making, on the other. Previously, almost no other poll had asked exactly how much Australians trust in constitutional change. However, by resolving trust into a set of discrete public values, the polling and analysis in this work provide evidence that constitutional reform might only succeed when it expresses, at once, the values of both majoritarian and deliberative democracy.]

The Commonwealth’s track record of limited constitutional change has seen much debate over whether Australia is, constitutionally speaking, a ‘frozen continent’.[1] In over 40 attempted referenda to amend the Commonwealth Constitution since 1901, only eight have succeeded. It is now more than three decades since the last successful attempt, in 1977. In 1995, Professor Brian Galligan identified the oppositional tactics of the federal parliamentary political parties as the ‘first and foremost’ of three reasons for negative referendum results, and also concluded that it was ‘probably unrealistic’ to expect this to change.[2] However, following the failure of the four bicentennial referenda of 1988 and the republic referendum of 1999, other leading commentators in politics and law have described Australia’s track record in constitutional deliberation as moving from bad to worse.[3] According to Saunders, the ‘highly adversarial character of most debate on constitutional change’ has reflected a distinct problem: ‘the failure of successive Parliaments and governments adequately to adapt [political] practices developed in the context of representative government to the quite different demands of the referendum.’[4]

This article revisits the problem of constitutional reform but brings to bear a set of perspectives often absent from legal scholarship. Literature on public trust in governance is burgeoning across the disciplines of political theory, philosophy and sociology.[5] Yet academic lawyers and constitutional policymakers generally overlook, and therefore still poorly recognise, the important roles that trust plays in constitutional reform. In recent years, renewed pressure for constitutional reform has arisen on issues that include Australian federalism, constitutional recognition of local government, electoral reform, civil rights protection, Indigenous recognition and, again, the republic.[6] But such objectives are unlikely to see significant progress without renewal of the constitutional change process in a way that addresses how constitutional deadlock is rooted in broader trends concerning public trust in authority. This article begins the process of extending the interdisciplinary literature on trust into the field of constitutional reform.

Viewing constitutional change through the lens of trust reveals much about the scope and contours of stalled reform.[7] Like most lawmaking, amending the constitutional text is an elaborately complex undertaking. It requires particularist expertise that is generally beyond the capacities of voters unschooled in the Constitution. However, in tension with this requirement, constitutional change also uniquely demands that an outsized role be played by citizens. This robust requirement of democratic legitimacy is a mainstay of liberal constitutional theory and is formalised in Australia in s 128 of the Constitution, which provides for public referenda to ratify (or deny) any change. Yet, despite the holding of referenda, proposed changes have in the main been imposed from above. Constitutional reform processes have traditionally entrusted the preparations for referenda — that is, initiating, writing and advocating for and against reforms — primarily to elites in government. The empirical literature on trust suggests that, under the institutional status quo, Australians will only continue to resist constitutional change. Like citizens of other liberal democracies, the trust that Australians have been willing to invest in governments has markedly declined since the 1960s.[8] Trends suggest that there will be a continuing period of sharpening critical scrutiny of and distrust in government elites — predicting, in turn, a deepening crisis for constitutional reform.

While Australia was one of the first nations to institutionalise a referendum model for constitutional amendment,[9] others followed suit and experienced similar obstacles.[10] More than Australia, however, foreign jurisdictions have also employed intriguing variations on the referendum model, recognising that referenda alone are blunt and frequently ineffective tools for constitutional reform. Some recent foreign institutional experiments have the potential to address the problem of reforms that falter not on their merits, but due primarily to the general posture of voter distrust in authority. Among these are the innovations of deliberative democracy. Deliberative democratic bodies potentially accommodate key values that are otherwise in conflict: majoritarian democratic legitimacy, on the one hand, and fair and well-informed — or ‘deliberatively rational’ — decision-making, on the other.

This work aims to provide Australian legal and public policy debates with comparative insights into how deliberation on proposed constitutional reform might be more effectively pursued. International experiments in deliberative constitutional change present lessons that, if adapted to the Australian context, may help restart overdue reforms. Two recent Canadian experiments in deliberative democracy provide important variations on experience by creating the ‘Citizens’ Assemblies on Electoral Reform’ in the Provinces of British Columbia in 2004 and Ontario in 2007. The Assemblies created what I call ‘public-experts’: citizen decision-makers who bridge the distance between majoritarian democratic legitimacy and deliberatively rational constitutional reform. Citizens’ Assemblies (‘CAs’) serve in effect as constitutional juries. They are small, representative cross-sections of the voting public constituted by a random lottery. Once chosen, CA members are instructed by experts over an extended period, ideally on a discrete question of constitutional reform.[11] They subsequently vote for a proposed amendment amid extensive debate. But a CA goes no further than recommending a constitutional amendment and presenting the arguments in its favour. At the end of the amendment process the general voting public has the final say in a referendum and gives (or denies) assent to the change. The CA model was especially effective in British Columbia — a jurisdiction characterised by political populism and polarisation,[12] and a potential analogue to Australia.

Comparative analysis of the Canadian provincial experience and Australian conditions, then, points to new opportunities for trusted processes of deliberative, citizen-led constitutional reform.[13] Yet a number of questions remain open. Would Australians respond to deliberative options as favourably as did voters in British Columbia, who gave an enviable 57.7 per cent endorsement to their CA process? Are the CAs transferable to Australian political culture? Would the public-expert model bypass the problem of distrust in constitutional lawmaking imposed from on high? Or might Australians perceive the new body as an attempt at constitutional sleight of hand — as just another band of elite and unaccountable decision-makers, distant from and unaware of the daily concerns of voters? The public-expert may be a novel and potentially workable category of decision-maker, a paradox incapable of assisting with the search for a better process, or something in between.

Outlined in theory in Parts II and III of this article, the potential for CAs to address the crisis of trust in Australian constitutional reform will at first remain speculative. This initial focus on theory yields to empirical evaluation in Part IV, where I report results from a nationwide opinion poll. The critical test for deliberative innovations in Australia may be whether they can attract the subjective trust of voters. A series of questions put to Australian voters inquired for the first time into the constitutional values that processes of change must accommodate in order to be likely to gain voter trust. What is clear from a long record of previous polls is that trust is in decline, and the need to find innovative solutions that enhance democracy in the preparatory process of referenda is essential. But beyond this there is much still open to question, and almost no other poll has asked exactly how Australians trust in constitutional change.[14] Using a combination of questions about real experience and hypothetical scenarios, the poll determines not only whether Australians trust in decision-makers of constitution change, but whether they trust them in specific ways. The study therefore adds essential content to what has previously remained a limited data set about public trust in relation to referenda.

While past public trust opinion polling leaves the notion of trust itself largely undefined, the poll reported in this article fills a wide and surprising lacuna in our current understanding of public trust in constitutional change. In scholarship on constitutional reform there remains a need for such accounts, which if sufficiently fine-grained, can help us recognise how — and how much — models of change can accommodate multiple democratic values. Indeed, by resolving trust into a set of discrete public values, the poll results provide tentative evidence that the process of constitutional reform might only succeed when it expresses, at once, the values of both majoritarian and deliberative democracy. Deliberative democracy, in some form, appears to be not just another piece in the toolkit of institutional design, but an emerging condition precedent, enforced by voters, of politically persuasive constitutional reform in Australia.

A longstanding insight holds that there is no best way to model institutions to guarantee democratic legitimacy.[15] Institutional designs choose from a buffet of democratic values. For example, in the House of Representatives, individual voter equality is supreme, while the Senate pays greater heed to the equality of regions: every state, big or small, receives the same allotment of senators. And of course some, but not all, democratic systems employ bills of rights to temper the voices of majorities. Yet against such wide normative variety, deliberative democracy does not merely offer more options. Instead, it partially sidesteps the compromises between values that usually characterise democratic design. This Part considers these and other benefits (and limits) of deliberative democratic constitutional change, both in the abstract and using the illustration of the CAs in Parts I(A) and B. Parts I(C) and D then identify two competing theories of what legitimate constitutional change means in terms of institutional design, contrasting deliberative approaches with relatively unmediated, laissez-faire citizen participation. Part III will then add further colour to these discussions by examining theories of deliberative constitutional reform through the lens of scholarship on trust.

Deliberative democracy emerged relatively recently as a discrete field, gaining momentum in the late 1990s and again after the Canadian CA experiments of 2004–07. Like many political ideas, however, the first suggestions arose much earlier and indeed have roots in antiquity. Deliberative democracy uses creative institutional design to attempt to transcend political polarisation and partisanship without sacrificing democratic legitimacy. A deliberative decision-making process re-routes democratic governance through generally longer and more complex paths. Deliberative democracy is more time-consuming than traditional democratic forms; but that is its point. Deliberative democratic governance embraces a more widely-varied set of inputs, drawing from public participants more robustly than is the traditional norm. Running democracy through a more elaborate deliberative course is a strategy to encourage participants to consider policy options not from pre-formed factional or ideological positions, but with greater attention to perspectives other than their own. While no institution can guarantee its members will assume an enlarged and flexible view of their own and others’ interests, deliberative democratic bodies at least leave open this possibility by putting decision-makers in the position to learn from and cooperate with each other. The bodies therefore typically include representation from broad social cross-sections.[16] Often as well, some form of participation or leadership by experts in a relevant field is essential. Much of the time spent therefore enhances participant exposure — both to other citizen-participants in a demographically diverse group and to specialist information.[17]

In 2004, British Columbia began a particularly creative and intriguing experiment with its world-first CA, which focused on choosing an electoral system. The CA was a constitutional convention comprising one academic chair and 160 lay citizens, chosen in part to reflect the Province’s demographic diversity.[18] Elections BC, an independent regulator, distributed more than 23 000 letters to citizens across the Province, based on a random draw from electoral rolls.[19] 1715 recipients sent back replies indicating a wish to take part.[20] From this group, a draw from a hat selected 158 citizens to participate — one man and one woman from each of the Province’s electoral divisions.[21] The selection was ‘stratified’ rather than wholly random, however, as CA membership was designed to reflect the Province’s diversity of regional, age and gender populations.[22] Later the legislature topped up the initial roster to include two indigenous members.[23]

The CA met on weekends over a period of eleven months, in three phases. First, in a ‘Learning Phase’, political scientists from the Province, as well as one from New Zealand and another from the United Kingdom, instructed members on the range of electoral models at work around the globe.[24] Delegates from across the Province assembled, at public expense, for six sessions at the Wosk Centre for Dialogue, a grand circular assembly hall in Vancouver.[25] At the sessions, experts put to work teaching strategies common in modern universities: interactive participation, a dedicated website, assigned readings and structured group work overseen by graduate students.[26] This phase also saw the establishment, by agreement among delegates, of ‘shared values’ for mutually cooperative engagement throughout the three phases.[27]

Second, in the ‘Public Hearings Phase’, the CA took submissions, either by writing or in person, at one of 50 public sessions across the Province.[28] Several CA delegates attended each session, interacting in total with some 3000 people.[29] Public perspectives were intended to help inform the next and final phase, the ‘Deliberation Phase’.[30] Deliberations were themselves phased and structured, initially around discussion of the broad values (eg, fairness) that should inform the provincial electoral system, and later around implementing these values in the particular options tabled (eg, ‘mixed member proportionality’ and ‘single transferable vote’).[31]

The winning proposal was a home-grown variant of the single transferable vote, which became known as ‘BC-STV’. Delegates voted, by near-consensus, first to establish government by proportional representation in the Province, and thereafter to recommend BC-STV in particular.[32] BC-STV also went to a Province-wide referendum for ratification. With 57.7 per cent of the broader public in favour of the recommendation, the level of support received was enviable by Australian standards — yet it fell short of the Province’s 60 per cent supermajority requirement (‘arguably set excessively high’[33]) to pass the recommendation into law.[34]

After the British Columbian experiment and a similar one in Ontario, the Netherlands followed suit with a large-scale CA,[35] marking the start of movements to bring the CA model to new matters and locations.[36] Legislators in California and the United Kingdom also later urged the adoption of CAs.[37] Elsewhere, new variations have been non-governmental, including ‘America Speaks’ in the United States, and a four-day ‘Citizen’s Parliament’ held at Old Parliament House in Canberra,[38] neither of which were directly empowered to write a referendum question like their Canadian forerunners. (The CA recommendations in Canada went straight to referenda, without further modification by elected elites.) Prime Minister Rudd offered appreciation (but little more) to participants, and the Citizens’ Parliament had at best a minimal impact on subsequent lawmaking.[39] Results are therefore mixed so far. Yet efforts to perfect the form should continue, and at a minimum must invest resources into lengthier deliberation and widespread publicity and public engagement, and authority to translate recommendations directly into further action.

If adequately resourced and empowered, governance by CAs represents an intriguing new addition to the canon of deliberative design.[40] A deliberative process ideally transforms its lay participants into public-experts well-versed in the concerns of other citizens and on the matters at issue, such as specific options for constitutional change. This in turn can create a cadre of citizens able to take the lead in shaping decisions of public significance. The role for elected representatives correspondingly diminishes. Deliberative democracy is a strategy to leave behind many of the approaches to governance offered by partisan parliamentary democracy. Most importantly, it offers a way around the widely-criticised but seemingly intractable party system, and an alternative to the dominant ‘distrust model’ of democratic design, which focuses on checking power and dividing it between mutually antagonistic factions.[41] The potential to transcend the usual narrow constructions of binary and oppositional political choices — in policy landscapes that are complex and pluralistic — is a key reason behind deliberative democracy’s expanding appeal.

Deliberative democracy improves in several respects on the distrust model of institutional design. The distrust and deliberative models have distinctive mechanics. The distrust model functions by promoting competition and antagonism among actors in government. This is the dominant approach of Australian and most other parliamentary democracies. Laws directly prohibit excessive concentrations of power, or detail elaborate sanctions against extra-constitutional, corrupt and other illegal, unethical or incompetent governance. Institutions also proliferate to prevent or prosecute abuses. The distrust model therefore features an in-built wariness and elevates a truism about the corruptibility of power to a comprehensive political philosophy. The American constitutional founders, for example, sharpened the rather vague divisions of power inherited from the British parliamentary model, and repositioned the separate branches to interpenetrate and block each other at every turn. Beyond these basic methods, a host of more particular distrust model constraints later flourished. Auditors-general and Ombudsmen are key modern examples that are now mostly understood as salutary. There are many other, more controversial modern examples. Independent prosecutors investigate the corruption of incumbent governments, coming under fire themselves for exceeding their briefs.[42] Financial bonuses provide incentives for government whistle-blowers.[43] And ‘bipartisan’ electoral commissions attempt to secure electoral fairness through partisan negotiation.[44]

At root, the distinction between deliberative and distrust model institutions is their degree of reliance on competition among decision-makers on the one hand, and cooperation on the other. In theory and at least sometimes in practice, deliberative decision-making design is not primarily competitive but rather cooperative.[45] This distinction turns in part on how the deliberative and distrust models orchestrate the stages of decision-making. Any decision-making process has stages of deliberation, during which the actors involved sift and evaluate information and ideas, and stages of determination, when a decision solidifies and formalises. Distrust model decision-makers are more likely to draw upon their own knowledge and analysis from start to finish — throughout both deliberation and determination. For example, in a decision-making committee, an individual parliamentarian, or members of a faction, might consider the benefits of substantially reshaping electoral rules without input from other people or factions.[46] Others must eventually enter into the process, but only at the determination stage, at which point factions often must negotiate, unless a majority can force its preferred result.[47]

One way of looking at the design of deliberative democratic institutions is as a series of attempts to delay the point where deliberation solidifies into determination.[48] Deliberative decision-making encourages decision-makers to interact throughout by cooperating, building on ideas in concert with others. Participants should therefore remain open to each other’s influence as near as possible to the point of final determination.[49] The principal benefit of delaying the point of determination is the so-called corporate resource of many heads: the breadth of relevant information and cogent reasoning that more people bring to a decision-making problem.[50] Under deliberative models, many people contribute prior to a decision’s final determination, each bringing a distinct point of view and perhaps constructing a more useful result.[51] This contrasts with the distrust model, whose foremost reason for adopting multi-member bodies is the potential to stifle corruption and abuse, as individual members feel the gaze of others upon them.[52]

What, however, is a useful decision? How is the corporate intelligence of individuals who are open to influence and persuasion by others better than the distrust model’s more atomised deliberations? Deliberative democratic institutions are distinguished by their encouragement of a particular form of rationality in public decision-making. On the one hand, like all bona fide democratic institutions, which manifest a range of public preferences and interests, deliberative democratic bodies insist on democratic legitimacy. On the other hand, within the bounds of this constraint, a system can pursue democracy in more or less deliberatively rational ways. The precise contours of deliberative rationality are open to debate and refinement; however, with some simplification, there are two main deliberative democratic conditions: information and fairness.

Decision-making can be hobbled by ‘incomplete understanding’ in the face of complexity,[53] or ‘too little information’.[54] Adequate information helps make decision-making more responsive to the problems it means to solve. In particular, deliberative democratic institutions accommodate multi-step reasoning. They recognise that problems addressed by government are exceedingly complex.[55] Solutions may not fit within the artificially few poles of debate constructed by simpler competitive discourses. While still a senator, Barack Obama described one of the frustrations of writing policy into law:

What every senator understands is that while it’s easy to make a vote on a complicated piece of legislation look evil and depraved in a thirty-second television commercial, it’s very hard to explain the wisdom of that same vote in less than twenty minutes.[56]

This point is key in decision-making. How we model a process — either simplifying issues or attending to them in their full complexity — determines whether government can ever deal satisfactorily with questions up for determination.[57]

There will always, of course, be differences of opinion. Competition among ideas is inexorable and useful. But when decision-makers deliberate, cooperation also becomes essential. Cooperative reasoning helps construct the complex ideas that public governance requires. Pith and brevity elude us in describing important legal reforms, which tend to emerge from weighing diverse details and abstractions. For example, we might describe the reasons behind a tax cut, in one or two steps, as giving people more money to spend and potentially stimulating economic activity. But the rationales for a new carbon tax and green technology fund, for example, rely on long chains of probabilistic causation. Warnings of climate change and its catastrophic economic costs must cover several scientific and economic steps. A green fund might ultimately retool the economy and offer its own economic stimulus over the long term, but selling the sacrifices involved to a voting public takes a great deal of effort. Complexity is similarly a feature of constitutional change, only more so. Any change that tweaks the constitutional order sends effects up and down the legal system. For instance, new proposed rules of selection for an independent Australian head of state would occupy the visible tip of an iceberg. The consequences of the new rules for Westminster-model government and Australian national identity would occupy the iceberg’s far greater fraction.[58]

Competitive procedures are usually more about winning arguments than about reaching outcomes that respond to policy realities.[59] Competition focuses foremost on allegiance — on securing a political win for factions to which various decision-makers belong. Factions may have narrowly defined aims. They may aim to win battles in Parliament in order to record a victory over opponents. They may hope to build political capital and momentum by appearing as the more competent and successful alliance in politics. Or they may intend to score victories for an ideology that defines the faction, but that, from within the straitjacket of competitive decision-making, members of the faction may lack the freedom to reconsider or refine. Outright competition is reactive and narrow in its scope.[60] It is generally not open to opposing views, and even less to re-conceiving decision-making as other than a binary opposition. But the issues facing government seldom arrange naturally around factional polarities. References to ‘ideological balance’ are pervasive in academic and popular thinking,[61] but ideological balance is an intellectual red herring of institutional design. There is little reason to assume that arguments for or against a policy will commonly, or ever, balance out evenly. Nevertheless, many new institutional models premised on distrust and competition continue to accommodate (and construct) a double-sided or ‘bipartisan’ notion of decision-making.[62]

The trouble with competitive decision-making models, then, is their bias in favour of simple over complex solutions. The simplification imposed by competition can place a drag on effective public decision-making. Economics, the environment, the Constitution, and much else, require governments to act based on thorough pictures of the policy landscape. In the practical terms of institutional design, this means, for a start, that decision-makers must not work in solitude. Complex action realistically requires the cooperation of many hands. If issues up for determination are in actuality complex, then so too should be the deliberations that address them. Cooperative decision-making on the deliberative model may help to construct decisions based on more complex, and thus more realistic, arrays of policy factors.

The second criterion of deliberative democracy concerns fairness as between people or groups subject to public authority. This is a more clearly normative dimension to deliberative decision-making. A recurring suggestion is that relatively cooperative decision-making can be sensitive to interests beyond those of merely an elite or limited selection of people. Thompson reasons that important public decisions ‘affect all citizens’ and therefore each citizen should ‘have a voice in the decision … [and] each should consider the views of other citizens when making the decision.’[63] Most modern strands of deliberative democracy scholarship build on the very old idea that just judgments in law or politics require leaders to exercise the moral creativity to place themselves in the shoes of others. Thus, for example, Rawls relied on the construct of decision-makers alive to the interests of the disparate groups of a society but blind to their own.[64] A host of antecedent writers relied on their own related metaphors.[65] For deliberative democracy these insights become problems of institutional design. The question is how to build on such ethical intuitions by operationalising them in governance.

Another way of putting the distinction between the distrust and deliberative models, then, is that the latter is meant to be more fair. Deliberative decisions are defined in part by what they are not: they are not driven by partisan or other selfish interests, such as the political party affiliation or personal social position of decision-makers. Neither, more controversially, do decision-makers bow to a pre-committed ideological position. But if impartial decision-making is not selfish, it must be something else. Fairness, defined positively, means that a decision-maker gives, in Uhr’s words, ‘due consideration [to] the issues, which means appropriately weighing all relevant matters before arriving at a decision.’[66]

Some reasonable doubt surrounds this notion. Can decision-makers adequately deliver on promises of fairness cast not only in simple negative terms, but also in the markedly more pluralistic positive sense? Such concerns are illusory in at least some cases. Fairness as ‘due consideration’ refers not to a deterministic guarantee of a decision that is substantively correct, but only to a process by which decision-makers maintain fidelity to the key issues bearing on the decision. This is a more manageable expectation. The Canadian CAs themselves provide good examples. Tasked with recommending new public voting systems, these bodies first canvassed practical and theoretical arguments for and against electoral systems now in use globally. The British Columbian CA ultimately recommended a ‘single-transferable vote’, while the Ontario CA recommended ‘mixed-member proportional’ representation.[67] The bodies came to different conclusions and recommended two quite different electoral systems, and yet by most accounts both were substantially fair throughout.[68] Fairness can be a matter not of reaching a correct final answer, but rather, more modestly, of openness to a relevant set of concerns and reasons.[69]

Finally, taking a wide view of the impacts of a decision includes taking the long view over a number of years.[70] This is one important reason why deliberative decision-making can be preferable to competitive decision-making, which tends to focus on the immediate self-interest of political factions. The wisdom of taking the long view is uncontroversial in the abstract, yet too infrequently informs institutional design. Processes with little scope for addressing long-term consequences are the rule. A recent example is the difficulty the Commonwealth Parliament had in trying to pass a climate change mitigation bill in 2009–10.[71] Environmental issues often illustrate both the difficulty of collective action under traditional democratic models and the tendency to neglect concerns of intergenerational equity, elevating the interests of people alive today over those who will come later. Constitutional change is also a paradigmatic case, given that such change is definitionally long-lasting. A constitutional rule established deliberatively, however, is ideally in part a product of decision-makers placing themselves in the position of those who will inherit their decisions in the future.

A basic critique asserts that deliberative democracy improperly intervenes in the democratic process.[72] A more democratically legitimate system would then be a laissez-faire approach of minimal external and legal control over democracy. Deliberative democrats, on the other hand, may reply to this critique by deploying the argument of ‘baselines’ familiar from economic and legal contexts.[73] There is always some level of state intervention already shaping social decision-making, rather than the legal vacuum assumed by proponents of laissez-faire governance. All institutions, deliberative or otherwise, leave their mark on the outcomes of decision-making and skew the results achieved. For example, as we saw, polarising institutions bias simple over complex policy. Indeed, all public governance channels decision-making through an assortment of assemblies, jurisdictional divisions or discrete phases. And, because each and every system of governance therefore features its own elaborate gauntlets of institutions and laws, the notion of unfettered politics is nearly always a fiction. Therefore, all other things being equal from the perspective of democratic legitimacy, we should choose to intervene in the democratic process in ways that also fulfil informational and fairness values.

Deliberative democracy attracts its share of critics who, for example, question the premise that deliberative democratic institutions confer as much democratic legitimacy as traditional models. Indeed from Aristotle, who was perhaps the first to theorise deliberation, to Burke, J S Mill and the American authors of the Federalist Papers, deliberation was long pictured as an elite imposition on, and necessary departure from, its opposite number, democracy.[74] Modern critiques continue to challenge deliberative democracy as under-inclusive.[75] This Part highlights other theories responding that deliberative democracy potentially manifests three democratic values — democratic legitimacy and the two deliberative conditions of information and fairness — not only as well as, but indeed more completely than, rival models. Deliberative democracy can sometimes resolve tensions between the values, rather than merely striking balances. We may therefore call deliberative democracy an ‘accommodative’ solution. The pursuit of accommodation is an explicit or implied focus of energies in recent literature on democratic legitimacy and fairness.[76]

This Part develops three facets of the argument that, by bypassing the value trade-offs that beset traditional democratic design, deliberative democratic institutions offer uniquely appealing models of constitutional change. These notes on the benefits in theory of deliberative democracy will provide context for opinion polling data on the subjective public appeal of deliberative innovations considered later in this article.

For normal lawmaking — that is, lawmaking not directly related to constitutional amendment — deliberative democracy can be preferable to traditional models because it does not wait for the conclusion of lawmaking before bringing fairness and informational concerns to bear. Every liberal democracy, including Australia, imposes what we might call ‘deliberative corrections’ on the excesses of popular rule. In normal lawmaking, it is usually judges who discipline democratic excesses. They issue corrections for fairness, for example, to safeguard the rights of inclusion of minorities in political life.[77] And they impose a comparatively well-informed, rationalist perspective, prohibiting some forms of arbitrary lawmaking and poorly-tailored laws.[78] On traditional models of democracy, then, judges often impose their own versions of deliberative rationality — of informed inquiry based on notions of fairness. But judges generally bring deliberative correction to laws that have already been enacted. This is a key difference in form. Deliberative democracy potentially safeguards fairness in the course of decision-making, which is often a more democratically legitimate option than the post hoc fix of judicial review.

Applying deliberative corrections in course first means that corrections are persuasive rather than coercive. Judicial review of normal lawmaking uses norms of constitutional fairness to strike down otherwise validly enacted legislation. Deliberative democracy can lead to similar substantive outcomes, but sees diverse segments of the voting public, along with expert participants (eg, the political scientists of the CAs), help shape the development of positions in dialogue throughout decision-making. Because fairness informs rather than overrules democratic choices, fairness and democratic legitimacy may be in less conflict than under traditional models. Indeed, many of the so-called dialogic theories that have colonised constitutional rights theory are appreciated for their similar accommodative benefits. Courts and legislatures are pictured as locked in long-term conversations over rights. According to Hogg and Bushell’s influential restatement, legislatures do not yield but rather respond to judges, and ‘[w]here a judicial decision striking down a law on [rights] grounds can be reversed, modified, or avoided by a new law, any concern about the legitimacy of judicial review is greatly diminished’.[79] However, unlike judicial review, in deliberative democratic decision-making the dialogue may be real — a face-to-face conversation sustained over time — rather than merely metaphoric, or at best impersonal, episodic and coerced.[80]

A corollary benefit is that improving deliberative rationality in a democratic process early on can bypass conflicts of rights. In traditional models, a top-down judicial fiat issues only after positions have solidified during lawmaking. Fully-formed rights clash when a judge invalidates a law (to which supporters may be deeply committed) only after the law’s final enactment. Thus, on the traditional approach, majoritarian democracy and legal provisions for fairness (eg, minority rights safeguarded in a constitution) are at odds.[81] Usually one must yield to the other. In contrast, deliberative approaches encourage majoritarian democracy itself to take account of fairness concerns and potentially therefore to head off clashes between rights. Encouraging deliberative rationality in course rather than post hoc might bring citizens’ democratic preferences closer to norms of fairness throughout the process of decision-making. Deliberative democracy is partly therefore a trick of timing; it ensures that diverse public interests interact at earlier cooperative stages rather than conflicting at later competitive ones. It may therefore alter preferences when they are still plastic rather than putting rights in conflict (or indeed infringing rights) by negating finalised preferences later on.

Finally, looking beyond normal politics to the politics of s 128, what forms of deliberative correction should feature in processes of constitutional amendment? Judicial review usually provides corrections for normal politics. However, unlike some other jurisdictions,[82] in Australia substantive judicial review of constitutional referendum results is unavailable. Formal constitutional change is therefore an area of lawmaking largely free of deliberative correction — arguably a regrettable circumstance given the outsized importance of constitutional lawmaking. Yet while post hoc judicial correction might be better than no correction at all, deliberative democracy applied in the course of decision-making is in any case preferable. The CA reform model, for example, could bring deliberative correction to bear on constitutional change in Australia, not merely in the flawed manner of judicial review, but more robustly through deliberative democracy.

In the tradition of Rousseau,[83] some authors understand the people as properly unrestrained in their constitutive power to write the constitution.[84] These perspectives are wary of corrections to democracy. In a number of respects, however, deliberative democracy expands rather than limits democracy by righting the democratic failures of governments left relatively unregulated. Similar arguments on this alternative line are familiar in the field of electoral law. John Hart Ely’s influential notion of ‘representation reinforcement’ views minority political rights as necessary fixes helping healthy democracies to prevent exclusions of discrete voter blocs.[85] This view conceives of minority political rights not only as rights of fairness benefiting their bearers, but also as rights making democracy itself effective.[86] Thus, to the extent that deliberative democracy secures greater fairness in democratic processes, it may be more democratically legitimate than traditional models.

Deliberative democracy theories also challenge the presumed tension between rational expertise and public influence in decision-making. The coherence of this tension is indeed too often overestimated. Rational and well-informed decision-making are not valuable in and of themselves; they are rather prerequisites to seeing public preferences through to fruition in policy-making. This position reflects the Humean notion that ‘[r]eason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.’[87] Indeed, deliberative rationality is a tool for the effective implementation of subjective, non-rational voter preferences. For example, if voters favoured it, the creation of an independent head of state to express Australian nationhood would be neither a rational nor irrational preference. However, the complex task of constitutional drafting and implementation would require a well-informed, deliberative process to help give practical effect to the choice.

Harder cases nevertheless arise where public preferences conflict. How can deliberative democracy express inconsistent public intentions? Sometimes even the same sets of voters hold contradictory views. For instance, polls in Australia consistently show strong public support for both the propositions that taxes should be lower and that government should invest in and do more.[88] One answer offered by deliberative democrats is that deliberative democratic process better informs public participants about the complexities of both the short- and long-term consequences of policy. As a result, it can encourage participants to understand how preferences relate to each other as coherent wholes, and to avoid unrealistic preferences.[89]

Finally, cooperative rather than competitive and polarised decision-making more readily allows public preferences to gain expression in the first place. When elaborate policy details must fit within a competitive model’s artificially few poles of debate, this focus on competition does not reflect the complex array of existing public preferences. Instead, it channels and recasts public preferences in its own limited terms. The irony of apparently unfettered, but highly polarised, democracy is that it is often severely hobbled by its own narrow scope of democratic representation.

While any preparatory system for referenda will tend to feature widespread public consultation, improved deliberation can increase the relative strength of public voices. Deliberatively rational discourse should give less preference to the preformed and polarised expressions of powerful speakers, such as elected representatives.[90] Cogent information or argument ideally then become the main currencies of decision-making, with the result that varied contributions to the process, whether lay, expert or party-political, rest approximately on equal footing regardless of origin. Interviews and observations of CA members for this work and others suggest that the bodies gave prominence to contributions of CA members and of participants in wider public consultations.[91]

To explain the causes of improved deliberation, Warren and Pearse place some emphasis on the British Columbian CA’s explicit early establishment of shared values such as ‘listening, open-mindedness, respect [and] clear communication’.[92] But self-conscious efforts such as these may be less important than indirect ways in which CAs improve deliberation. Deliberative procedures channel and orchestrate the interactions of decision-makers.[93] It is a relatively simple matter to determine where the emphasis of debate and discussion should lie by arranging who should be involved, with whom they should interact, at what time and for how long. This may bring different, or in Dryzek’s term ‘more democratic’,[94] arrays of decision-makers into contact. There are at least three variations on these themes. First, elevating randomly selected citizens to pre-eminent positions in the decision-making process establishes, both symbolically and in real terms, that reasoning through the issues from first principles is the primary function of deliberations. Citizen-members are political neophytes. They rarely have strong party affiliations and, in deliberating, tend to avoid falling into the preset discourses that often encumber debates among political professionals. Indeed, members of the British Columbian CA were ‘insulated’ from outside (including party-political) influence; most sessions were held in camera.[95] Second, decision-making processes can bring the contributions of academic and other experts to the fore, again highlighting and giving a concrete role to cogent reasoning as the central concern of decision-making.[96] Third, however, the array of contributions and interactions in a deliberative process is ideally widely diversified — yielding deliberations that are reasoned and informative, but ambiguous as a whole as a result of their extensive complexity. Maintaining ideological or party-political polarisation becomes more difficult against the background of multiple ideological and factional polarities.[97]

It was once a largely uncontested article of faith among political and social scholars that a distinctively egalitarian democracy prevails in relatively classless Australia. This faith is now more often rendered with greater nuance and attention to exceptions. Yet what is still clear is that a formidable egalitarian streak runs through Australian democratic practice.[98] One reason why referenda have failed so often is that voters do not trust their political ‘betters’ to initiate change;[99] many assume there can be no better or higher authority than one’s own native instinct and rational capacity. De Tocqueville’s observations in 1840 about American democratic participants could apply as well to modern day Australians:

[With] citizens, placed on equal footing … no signs of incontestable greatness or superiority are perceived in any one of them [and] they are constantly brought back to their own reason as the most obvious and proximate source of truth. It is not only the confidence in this or that man which is destroyed, but the disposition to trust the authority of any man whatsoever. Everyone shuts himself up tightly within himself and insists upon judging the world from there.[100]

Australian voter trust in constitutional amendment is indeed limited because, more generally, trust in political elites is limited. Why trust another to make decisions for me when I can trust myself?

The key question that such populist anti-elitism poses for deliberative democracy is whether a process of constitutional change, led not by political professionals but by voters themselves, may have a better chance at success. Trust in citizen-led change may then be higher than trust in the status quo approach to preparing changes. More trust in a process in turn may translate into greater receptivity to change. The key may be avoiding legislation imposed from on high; top-down approaches have previously attracted distrust and frustrated attempts at change. If voters trusted the lead up to referenda more than they currently do, would they be more inclined to give their support to changes even if — as is inevitably the case — many do not understand the question or its implications?

Not just any citizen-led process will work: constitutional amendment presents the puzzle of designing a process to avoid imposing change from above while remaining appropriately deliberative. Internationally, and particularly in the American state systems, a common alternative is the citizen-initiated referendum triggered by voter petitions. Twenty-four American states employ this populist technique.[101] The option was mooted and dropped during the Australian referendum round of 1988.[102] The democratic pathologies of citizen-initiated referenda are well-described elsewhere.[103] Most concerning are the tendencies of citizen-initiated referenda to target minorities invidiously, and to impose unworkable requirements on governance, such as Proposition 13, the infamous 1978 Californian interdiction against raising property taxes, which may have helped drive the state close to collapse during the recent financial crisis.[104] Even in normal economic times, from inside its citizen-initiated economic straightjacket, California has been all but ungovernable.[105] This case illustrates the flipside of the various rationales noted above in favour of deliberatively rational decision-making. Citizen-initiated referenda make little provision for fairness or for the holistic, well-informed approaches to policy-making that are the concern of deliberative democracy.

The CAs in Canada were indeed more deliberative. Citizens selected to sit on the CAs became experts in the constitutional issues they addressed. Nevertheless, like any institution, the CAs were far from perfect. At least three conceptual and practical problems arose then, and would arise again in the future should Australia adopt this approach.

First, is the notion of the public-expert paradoxical, or perhaps merely an empty symbol or sleight of hand? In Australia, conventions now prepare changes, with some public consultation. However, the parliamentary role has remained paramount, as the Prime Minister and a handful of others have tended to finalise referendum questions.[106] The public-expert of the CA is perhaps different because he or she is not a professional. What makes the public-expert ‘public’ is his or her political neophyte status at the outset of deliberations.[107] Yet members of the public brought into a process of deliberation over several months arguably are still insiders, like the professional politicians they replaced. As Thompson points out, CA members ‘began as ordinary citizens but ended as nascent experts’, opening up a ‘moral gap’ between members and other citizens.[108] However, CAs may yet answer some of the more pressing concerns of populist critics of the status quo. Among the more entrenched expectations of the populist tradition is that, as a solution to the corrupting influence of power, government should perpetually turn over, bringing in outsiders still in touch with the concerns of regular people.[109] CA members are indeed fresh, and at first unprofessionalised, entrants into the system. There is arguably still cause to trust their motives for promoting particular constitutional changes, at least for a time, before they themselves become accustomed to power. Indeed, the CAs’ uninitiated, politically untarnished and demographically representative citizen members tend to encourage average voters to identify with CAs, reasoning that members are ‘just like me’.[110] Choosing participants by citizen lottery means that every voter knows that he or she might have sat on the CA, or could sit on the next. CAs thus have the potential to narrow the gap that voters perceive between themselves and the process of constitutional amendment.[111]

A second potential critique stems from the CAs’ stratified method of random selection, which makes the bodies approximately representative of demographic groups such as female, aboriginal and regional voters. Such identity-based representation departs from traditional democratic approaches, which principally represent geographic regions.[112] The traditional model’s weakness is often its majoritarianism, which can ignore or actively work against the interests of minority identity groups in a district.[113] Yet just as inevitably, parliamentary systems premised on identitarian representation descend into insoluble questions about which groups should be represented, and how indeed to represent various groups, whether large or small, discrete or overlapping, on an assembly of perhaps 160 people.[114] In democratic terms alone, there may therefore be no clear resolution to this tension between forms of representation, making it a classic dilemma of conflicting values of democratic design.[115] The choice among models should perhaps turn instead on their other costs and benefits — including potential effects on public trust.

A third problem is getting the size of a deliberative assembly right. The larger the body, the more representative it may appear to be, yet genuine deliberation becomes more difficult with increasing size.[116] The American caucus system illustrates this tension. During election years, some states convene caucuses to choose candidates who will run for state or national office under a particular party banner. In some cases the participants involved number over four per cent of all state voters[117] — in comparison with, for example, the British Columbian CA’s 160 members out of a provincial voter base of 2.6 million.[118] A drawback of caucuses, however, is that their deliberative content is limited by their large size. Supporters of various candidates typically stand together at discrete points in assembly halls, trading positions only as candidates drop out of the race during successive ballots.[119] Debate is limited. Candidate supporters generally come bearing pre-formed partisan positions. The system may then be attractive for its relative inclusiveness, but not for meaningful cooperative deliberation. The importance of having a large body is therefore questionable. Indeed, as its relatively impressive referendum outcome suggests, the British Columbian CA attracted wide public trust despite its small size.

In sum, applying the CA model is not a straightforward matter. The model raises complexities, and indeed the exact form it should take is subject to some variation. Even in the two Canadian Provinces in which CAs have run thus far, the bodies differed in size, methods of public education and involvement, and political–cultural contexts. The unvarying characteristic of the CAs, however, was their use of voters themselves as middlemen charged with investigating, preparing and presenting the case for change. Deliberative democratic innovations may not be the only means of addressing the tensions of democratic institutional design. But, as accommodative systems able to resolve and diminish these tensions, they may be the most suitable for Australia, particularly in light of the serious impediments to constitutional change posed by an (otherwise salutary) egalitarian national democratic culture.

A question that remains open, however, is whether the theoretical points canvassed in this Part are also reflected in subjective public perceptions of the legitimacy of constitutional change. In the following Parts, I therefore offer empirical complements to the preceding theory. The discussion also turns from foreign cases to the Australian case. I first introduce the polling study conducted for this article with a discussion of its main variable: trust. I then detail the poll’s intriguing findings, which offer evidence that deliberative democracy is an emerging social expectation, and even perhaps a prerequisite for successful constitutional change in Australia.

The theories above suggest that deliberative democratic constitutional change is as democratically legitimate as traditional options: as an accommodative form of democratic design, it is appealing for its capacity to avoid trade-offs between democratic values. Yet the idea of legitimacy entails, at least in part, a public’s subjective confidence in authority. Any theory of democratic legitimacy should account for public intuitions about the nature of legitimacy.

In this Part, I introduce the distinctive public trust angle on questions of legitimacy and constitutional change posed in the polling study. The poll inquires about legitimacy by an indirect route, using public trust as the main unit of measurement. As yet, few authors have read constitutions and constitutional change in depth using the complex and burgeoning interdisciplinary literature on public trust in governance. Yet trust is a powerful analytic lens in this context. Trust is defined in much the same way in both lay and academic understandings: by trusting, one person invests power over herself in another person, expecting the power to be exercised in salutary ways. Trust therefore has an objective facet (the act of investing power) and a subjective facet (belief that the investment is justified). From basic definitions such as these, sociologists, philosophers and political scientists have explored the concept’s many additional aspects and implications.[120] But because trust remains a term whose basic usage is the same in the public and scholarly domains, it is not the exclusive preserve of political theory or any other singular context. Trust is therefore a helpful frame of reference for theorising democratic legitimacy. In contrast to legitimacy, less linguistic baggage attaches to trust and so it does not presuppose a particular model of legitimacy. Reasoning in terms of trust permits us to reconsider legitimacy through a wider lens, relatively unclouded by presupposition (for example, about the greater legitimacy of either laissez-faire or deliberative democratic constitutional change).

Moreover, trust can serve as a bridging language between theory and empirical inquiry; by examining trust, we can check hypotheses about legitimacy using a simple and broadly cognisable unit of empirical measurement. Because definitions of trust are tightly anchored to human intuition, the language of trust is valuable for gauging public perceptions of an otherwise arcane and multivalent concept such as legitimacy.

Perhaps most importantly, using the language of trust to bridge theory and empirical inquiry also allows debates about institutional design to draw on impressive existing literatures on trust, including troves of historical data. A key trend in more than four decades of polling has been the hardening of public views about the trustworthiness of governments in liberal democracies.[121] The implications for constitutional change are considerable, though little effort has been made to understand or address them as problems of trust. Declining trust since the 1960s is chiefly a consequence of changing social attitudes.[122] For example, there is little evidence of greater corruption in public office; what appear to have changed are social expectations — about government, the role of the citizen and the citizen’s proper quantum of respect for authority.[123] Such broad changes in subjective trust could not have been foreseen at the advent of the constitutional referendum mechanism in 1901. Section 128 of the Constitution on its face expresses the expectation that Australians would, at least from time to time, be sufficiently credulous in their attitudes toward political elites to vote for reforms.[124] But subjective decline also drags down objective trust: in most liberal democracies, citizens are now more miserly when bestowing powers on elites. Viewed in light of data indicating trust’s long descent, Australians’ unwillingness to give their assent in constitutional referenda appears both unsurprising and unlikely to reverse under the institutional status quo.

Declining trustworthiness, then, is in the eye of the voter: government has not significantly changed, but subjective public attitudes about government have. Yet the consequences of the decline for successful constitutional reform are real. As Saunders notes, a ‘[c]onstitution alteration procedure does not operate in a vacuum’;[125] among other factors, it ‘is affected by political culture. … Normative limits are imposed by considerations of democracy, Australian-style.’[126] Though no formal judge writes such norms and remedies their breach, some norms present powerful implicit constraints on governments. A government hoping to change the Constitution must abide by basic rules enforced exclusively by social sanction. The place of such norms is clearest under s 128 of the Constitution, where the final judges are electors themselves. But how can we gauge the socially normative conditions for successful constitutional change if it so seldom occurs? Detailed speculation as to changes that might succeed must rest on what is known empirically about evolving public expectations of government, including perceptions of public trust. In this light, at least two key expectations appear to be emerging.

The first and clearest norm is a requirement of public consent. As Uhr notes, governments ‘may not be capable of restraining [the] … popular tide of interest in greater participation in government decision-making.’[127] This includes participation in constitutional change. The overarching lesson from post-1960s data on trust is that voters will resist investing power in any authority above themselves.[128] Too little consultation and too little trust in the preparation for referenda may predetermine unsuccessful votes. In the recent past, proposed changes emerged from a preparatory process whose main democratic content was the party-political conflict of elected representatives, and relatively brief, non-binding public consultations that had vaguely and unsatisfactorily defined influence on the shape of proposed changes.[129]

A norm of public consent to constitutional reform is now established in many liberal democratic societies. In Canada, for example, three successive attempts to change the federal Constitution while including the hold-out Province of Quebec saw increasing public consultation: from the minimalist parliamentary committee hearings of the late 1970s to a nationwide referendum in 1992. Major constitutional changes in Canada now informally require public consent by referendum.[130] On the other hand, the two most recent Canadian constitutional reform attempts faltered outright, despite the political investments of a wide spectrum of elected leaders. As in Australia, consultation by referendum has not guaranteed public assent.[131] Greater attention must be given to whether the preparations for referenda enjoy trust and perceptions of legitimacy, which make positive referendum results more likely.[132] The dominant institutional approaches still common in Australia sometimes evince little awareness that liberal democratic publics have lost the willingness to go along with the prescriptions of their presumptive political betters.

The deliberative democratic theories detailed above indicate that democratic legitimacy is a more complex matter than simply securing public consent. A rule of public consent is significant but under-informative on its own. Concretely, institutions can take at least two more particular directions, each of which may gain cultural acceptance to greater or lesser degrees in Australia as compared with other jurisdictions.[133] The first is again laissez-faire, leaving power relatively unmediated as a formal matter.[134] Here minimal institutional and legal interference comes between voters and their expressions of will regarding constitutional change. Citizen-initiated referenda are paradigmatic laissez-faire solutions, which steer clear of objective acts of trust investing power in institutions. The laissez-faire model appears at least superficially suited to Australian democracy and its egalitarian flavour. However, a second option is deliberative citizen-led constitutional change. This institutional path differs from that of many states of the United States. The decision-making of CAs is elaborately structured to mediate change and improve deliberation. Yet like laissez-faire models, CAs avoid elite control from above, leaving the task of mediation to citizens themselves.

Democracy structured to accommodate deliberative values may be a public expectation approximately as important as public consent. This hypothesis assumes that Australian political culture is multifaceted and not merely egalitarian. For example, the Australian public’s embrace of exacting legal regulation in many aspects of private and public life is also a prominent cultural feature. The potential for dysfunction associated with unmediated democracy may not be lost on Australians, who are presumably wary of unchecked change or of leaving decision-making to the vagaries of other citizens’ whims and preferences. More particularly, voters may recognise that, because constitutional change is complex, a full understanding of its implications is beyond their own competence. Investing trust in experts is then necessary. Nevertheless, democratic norms still suggest that the expert role must be handled by voters themselves.

Deliberative democratic institutions may succeed in juggling these diverse and otherwise contradictory conditions. The hypothesis tested in the following Part is that electors themselves impose conditions of fairness, information and majoritarian democracy on constitutional change and that, in contrast with traditional models, deliberative democratic constitutional change can attract significant trust by accommodating each of these conditions.

The survey of attitudes toward federal constitutional change presented detailed questions to 1100 voting-age respondents throughout Australia.[135] In order to decouple questions about the process of constitutional change from any particular reform movement, a key aim was to present options in general and hypothetical terms, rather than as means to a particular substantive end. However, in a complex poll such as this, some initial context-building touching on substance was necessary. Potential areas of change were introduced in an opening series of questions about the reforms that respondents would consider to be important enough to submit to referendum ‘in the next few years’. The possibilities were diverse: whether ‘Australia should become a Republic’; whether ‘to recognise the history and culture of Indigenous Australians in the Constitution’; ‘what levels of government Australia should have’; and ‘which level of government is responsible for doing what’.[136]

After these preliminaries the poll turned to the main questions. The first of these were about the values that should inform constitutional change. Questions about values were designed to yield detailed insights into what kind of reform process electors would trust. As noted previously, in an area such as constitutional change, where the people have the last word under s 128 and trust is generally in short supply, questions about how reforms gain public trust cannot be avoided. To the extent they are neglected, these norms pose barriers to constitutional change.

The value options presented in the poll were those examined above: majoritarian democracy, fairness and well-informed process. The lacuna in empirical scholarship on what is necessary, by popular expectation, for constitutional change to take place has been noted.[137] Policymakers and some commentators have often assumed the answer is more majoritarian democracy: that the ability of a process to discern and give voice to dominant public sentiment is the acid test of democratic legitimacy for constitutional change.[138] But as set out above, there are reasons why fairness and adequate information must also play roles. Before the present work was conducted, an open question remained whether processes making no provision for these deliberative values would attract significant trust.

The poll asked respondents to rank which values are ‘most important’, ‘next most important’ and ‘least important’ to the ‘process of writing the proposed change, and the arguments for and against it’. (Since electors as a whole must give their final assent by referendum to proposed reforms, for accuracy, stress was placed on what values should inform processes for preparing referenda.) These questions are key to understanding what voters themselves take to be democratically legitimate constitutional change.

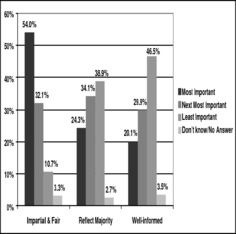

The poll showed substantial primary support for ‘impartiality and fairness’[139] — which received, at 54.0 per cent, more first-choice preferences than the other two options combined. This result casts doubt on assumptions about the pre-eminence or sufficiency of majoritarianism. Fairness — an element of deliberatively rational decision-making — is also clearly a relevant factor, and on the evidence a more important one. Unsurprisingly, the results do not discount the importance of giving voice to democratic majorities. That value attracts reasonably strong support over the first and second choices of respondents. Slightly shallower importance was ascribed to well-informed process, the other aspect of deliberatively rational change. Even so, 20.1 per cent of respondents ranked well-informed process first (just below the 24.3 per cent who favoured majoritarian democracy first), and its second choices were approximately equal in frequency to second choices recorded for other values.

At the broadest level these results illustrate that not one but three values are viewed as substantially important. Majoritarian democracy should not be assumed to be the primary factor lending legitimacy to constitutional change. A corollary may be that this value is insufficient for generating trusted constitutional change on its own. Indeed, by a wide margin, fairness in a process of constitutional change is the value most clearly required.

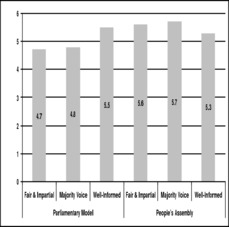

Following this groundwork on values of constitutional change, further questions examined support for a new CA-inspired body for Australia, styled a ‘People’s Assembly’.[140] The questions indicated that the body would be empowered to deliberate over and propose constitutional changes, and to lead the campaign for their implementation, but would leave final judgment to the full electorate.[141] The questions compared whether this deliberative democratic innovation would command more or less trust than the mainly parliamentary approach of the status quo. However, as noted previously, questions about how exactly people do or do not trust particular procedures to secure constitutional change can be more useful than questions premised on less defined notions of trust. In these questions, then, in order to determine why the two models attracted particular levels of trust overall, questions tying trust to the three specific constitutional change values were asked first. On a 10-point scale, respondents indicated ‘how much trust and confidence’ they would have, in terms of the three values, in either a People’s Assembly or the parliamentary model to lead change.

Trust in Model (0–10)

The average scores given by respondents to the People’s Assembly were notably higher overall than those for the parliamentary model. But these results more importantly disclose intriguing comparisons among scores for trust in relation to particular values. The parliamentary model attracted relatively low trust for fairness and majority voice, but higher trust as a well-informed process. The People’s Assembly yielded mirror-image results: lower trust as a well-informed process, and higher scores for fairness and majority voice. The suggestion that emerges is that deliberative democratic forms of government are not only viewed as more deliberatively rational than traditional representative democracy, but also more sensitive to majority interests — apparently trumping traditional democracy in what might be assumed its area of strength. Australians as a whole would appear to agree with researchers who defend deliberative democracy as both more deliberative and more democratically legitimate. On the other hand, in terms of the other main deliberative value, the parliamentary model is understood as better-informed.[142]

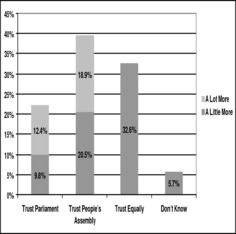

The results additionally provide insight into why people trust the different models. A final group of outcomes, shown below, indicate substantially higher overall trust in the new deliberative democratic People’s Assembly model as compared with the status quo. However, that stark overall result tells us little, on its own, about why Australians would prefer a People’s Assembly. Overall perceptions of trust mask the roles of more specific values. We saw above that the parliamentary model attracts more trust for its sensitivity to constitutional information, while for a People’s Assembly trust would be stronger in respect of fairness and majority voice. Neither model therefore enjoys greater trust across the board. However, from the groundwork questions on values we also know that respondents consider fairness and majority voice to be highest in importance. In a People’s Assembly, then, there is a confluence of high-importance and high-trust values. Because the values with which a People’s Assembly is associated are those generally thought to be the most important, overall trust should be higher as against the traditional model. The final set of responses, showing a People’s Assembly favoured by nearly 2:1 among respondents who stated a preference, confirms this prediction.

Australians appear to be willing to experiment with deliberative democracy — a result belying assumptions that the national posture toward constitutional change is a naturally conservative one. Australians may previously have opposed changes in significant part because the changes were proposed in democratically deficient ways. In the poll, the People’s Assembly attracted more trust by a notable 17.2 percentage points. It may be significant that, in just over half of all Australian federal referenda held to date, the difference in percentages between votes cast for and against referendum proposals has been less than 10.0 points.[143] Of course, we cannot directly translate relative trust in a process of reform into a presumed outcome for either the ‘yes’ or the ‘no’ side of a referendum. Such a connection cannot be assessed in hypothetical terms; despite a well-trusted referendum process, voters might disapprove a change for its substance. However, if increased trust on this scale held in a referendum, the effect on voting could be substantial, particularly among electors under-informed about the case for constitutional change and otherwise distrustful of political elites asking for their support.

This article aimed to bring scholarship on trust into legal discourses of constitutional amendment. Trust is one of the chief intangibles that determine the effectiveness of governance. Yet among Australian voters there is a hardening resistance toward trusting any authority other than one’s own. For the Commonwealth to restart stalled processes of constitutional change, it will be necessary to master the difficult terrain of generating public trust in the lead up to referenda in spite of generally worsening conditions. The poll conducted for this article provided information about points where public values converge on questions of trust in governance. In this way, the article began a project of characterising the public expectations that constrain constitutional practice, determining whether and when trust develops to enable governments to achieve ends such as constitutional reform. In addition to the unsurprising public focus on majoritarian democratic legitimacy, constitutional change notably must substantially fulfil deliberative democratic values. The poll showed that Australians do not wish to see their democracy, in the lead up to referenda, focused on the relatively coarse majoritarianism of the parliamentary model.

To be sure, these innovations call for more Australian research and elaboration, for example on their potential scope of application in Australia, on the challenges of introducing CAs into substantially polarised settings,[144] and on optimal ways of designing the CAs’ engagement with the wider public.[145] However, in broad terms initially, the poll results indicated strong value preferences for deliberative democracy in Australia, which, though less majoritarian, is the majority’s preference. This clarified why a second and more concrete result showed Australians more likely to embrace the alternative of a People’s Assembly, designed on the CA model of deliberative democracy. There is an apparent willingness to invest power in and to trust an assembly of citizen peers if doing so helps to moderate the excesses of majoritarianism without involving distrusted elites. By accommodating deliberatively rational and majoritarian democratic values, a well-funded, well-publicised and carefully designed People’s Assembly in Australia might bring substantially greater public trust to the process of constitutional reform.

[∗] BSc (McGill), JD (Toronto), LLM (Columbia), PhD (Osgoode); Lecturer, Griffith Law School. I am greatly indebted to Griffith University for a grant enabling polling for this work; to A J Brown for project guidance; to Afshin Akhtarkhavari, John Dryzek, Jeanette Hartz-Karp, Ian McAllister and Haig Patapan for feedback or discussion in Australia; to Jack Blaney, Gordon Gibson, Matthew Mendelsohn and Mark Warren in Canada; to the Review’s three anonymous reviewers; and to Will Barker and Jess Howley for research assistance.

[1] Geoffrey Sawer, Australian Federalism in the Courts (Melbourne University Press, 1967) 206.