Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

JASPER HEDGES,[*] HELEN BIRD,[**]

GEORGE GILLIGAN,[†] ANDREW GODWIN[‡] AND IAN RAMSAY[‡‡]

The enactment of the civil penalty regime in 1993 introduced a new approach to the enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies in Australia. The policy considerations that led to the regime, and which continue to inform current policies on corporate law enforcement, require that: civil enforcement be given primacy over criminal enforcement, with the latter reserved for more serious misconduct; a range of sanctions be calibrated to the severity of the misconduct in accordance with a pyramidal model of enforcement; and sanctions be set at a sufficient level to deter misconduct. This article analyses the extent to which these policies have been applied in practice by reference to a 10-year dataset of 27 civil, 72 criminal and 199 administrative directors’ duties matters (involving 360 defendants) brought by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions. The dataset, which includes data obtained from ASIC and the CDPP that has not previously been published, indicates that such policies have, to a large extent, not been applied in practice. These are significant findings given the central role that enforcement of directors’ duties performs in the regulation of corporate activity in Australia and the impact of such activity on society and the economy.

CONTENTS

The enactment of the civil penalty regime[1] in 1993 introduced a new approach to the enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies in Australia.[2] Prior to the 1993 reforms, enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies predominantly involved criminal enforcement by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (‘CDPP’).[3] The Australian Securities Commission (‘ASC’)[4] had limited civil and administrative powers in relation to the enforcement of directors’ duties prior to the 1993 reforms.[5] The civil penalty regime empowered the ASC to bring civil proceedings involving a broader range of duties and sanctions[6] and this was followed by the expansion of the ASC’s administrative powers.[7] Since the enactment of the civil penalty regime, enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies in Australia has thereby evolved from a predominantly criminal law approach into a multi-jurisdictional system of overlapping criminal, civil and administrative sanctions.[8]

The policy considerations that led to the enactment of the civil penalty regime continue to inform current policies on the enforcement of corporate law.[9] The regime was enacted in response to the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs’ Report on the Social and Fiduciary Duties and Obligations of Company Directors (‘Cooney Report’).[10] The Committee, chaired by Senator Bernard Cooney (‘Cooney Committee’), considered that existing criminal sanctions for the enforcement of directors’ duties were unsatisfactory for a number of reasons, including that: criminal sanctions were inappropriate for misconduct that was not ‘genuinely criminal’;[11] ‘draconian’ custodial sentences were a disincentive to prospective directors;[12] and ‘modest’ fines were bringing the law into disrepute.[13] Civil sanctions were recommended with a view to creating a ‘“pyramid of enforcement” ... with civil measures at the base of the pyramid for the general run of cases, and criminal liability at the apex for the more exceptional instances of law-breaking.’[14] The Committee emphasised that ‘[p]enalties must suit the offence’ and ‘[t]hey will have no deterrent value if their level is insufficient.’[15]

Three key policy considerations can be distilled from the Cooney Report and other extrinsic material surrounding the enactment of the civil penalty regime. First, civil enforcement should be given primacy as the mode of enforcement applicable to the bulk of directors’ duties matters, while criminal enforcement should be reserved for more serious misconduct.[16] Second, a range of different sanctions should be tailored to the circumstances of the misconduct, in accordance with a pyramidal model of enforcement. Third, sanctions should be set at a sufficient level to deter corporate misconduct, both by the defendant (‘specific deterrence’) and the public at large (‘general deterrence’).[17] Part III of this article discusses these original policy considerations in more detail and explains how they continue to inform current policies on the enforcement of corporate law.

This article analyses the extent to which these policy considerations have been applied in practice by reference to a 10-year dataset of civil, criminal and administrative directors’ duties matters brought by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (‘ASIC’) and the CDPP that were finalised between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014. The dataset, which includes data obtained directly from ASIC and the CDPP that has not previously been published, indicates that these policies have, to a large extent, not been applied in practice in relation to the enforcement of directors’ duties. Civil enforcement was significantly less prevalent than criminal enforcement, despite the ostensible primacy of civil enforcement.[18] Civil enforcement accounted for only 19.23 per cent of matters in which contraventions of directors’ duties that attracted both civil and criminal forms of liability were proven.[19] The majority of sanctions were incapacitative,[20] which is contrary to a pyramidal model of enforcement, as such a model requires that more lenient enforcement measures be considered prior to incapacitation.[21] Incapacitative sanctions — encompassing custodial sentences involving a minimum period of incarceration, civil disqualification orders and administrative disqualification outcomes[22] — collectively accounted for at least[23] 78.81 per cent of all sanctions.[24] Monetary sanctions and custodial sentences were set well below the statutory maxima, casting doubt on their deterrence value.[25] The median civil

pecuniary penalty imposed on defendants who engaged in a single

contravention of a directors’ duty was $25 000 (12.5 per cent of the statutory

maximum of $200 000 per contravention),[26] while 46.43 per cent of

custodial sentences imposed for contraventions of directors’ duties were

fully suspended.[27]

These research findings are significant given the central role that enforcement of directors’ duties performs in the regulation of corporate activity in Australia and the impact of such activity on society and the economy. Directors’ duties regulate the conduct of individuals who exert significant influence on the actions of corporations,[28] which collectively command substantial social and economic power. There are 2 429 200 companies registered in Australia[29] and the private sector’s share of gross value added has been estimated at 85 per cent.[30] The lawful and responsible management of companies is therefore vital for the wellbeing of the nation. As Middleton J commented in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Healey,[31] ‘[t]he role of a director is significant as their actions may have a profound effect on the community, and not just shareholders, employees and creditors.’[32] Senator Cooney similarly emphasised the link between responsible corporate governance and the nation’s wellbeing in 1993:

The modern corporate sector has a profound effect on our life. It is crucial to the creation of the nation’s wealth. Society looks to it to produce that wealth ethically and in accordance with community values. Directors are the mind and soul of the corporate sector. They are crucial to how its great power is exercised. They can weaken and even suppress markets. They can disturb and destroy an environment. Their actions can have a profound effect on the lives of the shareholders, employees, creditors and the public generally.[33]

The research findings presented in this article are also significant from the perspective of comparative law and policy. Unlike some other common law jurisdictions in which enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies (as opposed to private litigants) is limited, such as the United States[34] and the United Kingdom,[35] public enforcement of directors’ duties has occupied a central role in Australia for many years. Proceedings brought by ASIC and the CDPP account for approximately half of all judicial matters involving directors’ duties.[36] In addition, ASIC is responsible for a significant number of administrative actions involving directors’ duties, principally in the form of disqualification orders.[37] Australia pioneered a number of key developments in relation to the enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies. It was the first common law jurisdiction to enact statutory directors’ duties in 1896[38] and to introduce public enforcement of such duties in 1958.[39] Scholars have encouraged other jurisdictions, including the United States,[40] the United Kingdom,[41] Hong Kong,[42] Singapore[43] and New Zealand,[44] to look to Australia’s enforcement regime in regard to establishing, expanding or refining their own public enforcement regimes.

This article also provides a timely contribution to the current policy debate on the enforcement of corporate law in Australia. In 2014, the report of the Financial System Inquiry recommended that ‘[t]he maximum civil and criminal penalties for contravening ASIC legislation should be substantially increased to act as a credible deterrent for large firms.’[45] In response to this recommendation, the Australian government has committed to reviewing ASIC’s enforcement regime and penalties in 2017.[46] This review follows a number of other recent initiatives targeted at improving corporate law enforcement, including the 2013–14 Senate Inquiry into the Performance of ASIC[47] and the 2015 Capability Review of ASIC,[48] the latter being conducted to ‘ensure that ASIC has the appropriate governance, capabilities and systems to meet [its] objectives and future regulatory challenges.’[49] Most recently, the Senate Economics References Committee has conducted an inquiry into the ‘inconsistencies and inadequacies of current criminal, civil and administrative penalties for corporate and financial misconduct or white-collar crime’ in 2015–16.[50] The findings presented in this article build on these developments and contribute to evidence-based discourse on the appropriate policy settings in regard to corporate law enforcement in Australia.

The structure of this article is as follows. Part II briefly discusses the enforcement of directors’ duties prior and subsequent to the civil penalty regime and provides an overview of the current directors’ duties provisions and sanctions in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Part III discusses in more detail the policy considerations that led to the enactment of the civil penalty regime in 1993 and explains how these considerations continue to inform current policies on the enforcement of corporate law. Part IV presents the findings of the empirical study of civil, criminal and administrative directors’ duties matters, which reveal that, to a large extent, the policy considerations that ostensibly inform the enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies have not been applied in practice.

The enactment of the civil penalty regime in 1993 introduced a new approach to the enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies in Australia. Prior to the 1993 reforms, enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies predominantly involved criminal enforcement by the CDPP. The sanctions that could be sought in criminal proceedings included custodial sentences,[51] fines[52] and compensation orders[53] under the Corporations Act 1989 (Cth)[54] in addition to the sanctions ordinarily available for federal offences pursuant to the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth).[55] Defendants who received criminal convictions for contraventions of directors’ duties were also subject to automatic disqualification from managing corporations for a period of five years from the date of conviction or, if the defendant was sentenced to imprisonment, release from prison.[56]

The ASC had limited civil and administrative powers in relation to the enforcement of directors’ duties prior to the 1993 reforms. These included the power to seek civil disqualification orders for repeated contraventions of the Corporations Act 1989 (Cth),[57] contraventions of the duties to exercise reasonable care and diligence and to act honestly,[58] and involvement in two or more failed corporations,[59] as well as the power to impose administrative disqualification orders on directors as a result of adverse reports from liquidators.[60] The civil penalty regime empowered the ASC to bring civil proceedings involving a broader range of duties[61] and sanctions, including pecuniary penalties[62] and compensation orders[63] in addition to disqualification orders.[64] The civil penalty regime was followed by the expansion of administrative enforcement powers, with the introduction of enforceable undertakings in 1998[65] and the application of disqualification orders imposed by the ASC to company officers as well as directors in 1999.[66]

Civil and administrative sanctions have, for the most part, supplemented rather than displaced existing criminal sanctions, with the exception of the decriminalisation of the duty to exercise reasonable care and diligence in 1999.[67] The power of criminal courts to order compensation under s 588K of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) has also been limited to contraventions of the duty to prevent insolvent trading pursuant to s 588G(3). However, this has had little practical impact as the CDPP is able to seek reparation orders under s 21B of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) for contraventions of directors’ duties. Since the enactment of the civil penalty regime in 1993, enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies in Australia has thereby evolved from a predominantly criminal law approach into a multi-jurisdictional system of overlapping criminal, civil and administrative sanctions.

The empirical study presented in this article encompasses the following directors’ duties provisions: ss 180–4, 191, 195, 209 and 588G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and their predecessors, ss 232(4), 232(2), 232(6), 232(5), 231, 232A, 243ZE and 588G of the Corporations Act 1989 (Cth). For ease of expression, this article herein refers to these duties by their current section numbers in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), rather than citing both the current sections and their predecessors in the Corporations Act 1989 (Cth).

Table 1 summarises the substantive content of the directors’ duties, the applicable civil and criminal section numbers, and the persons to whom the duties apply. The duty to exercise reasonable care and diligence pursuant to s 180 only attracts civil liability, while ss 191 and 195, which deal with conflicts of interest, only attract criminal liability. The remaining duties attract both civil and criminal liability. Criminal liability is subject to additional fault elements, with the exception of s 195, which is a strict liability offence.

Table 1: Directors’ Duties Provisions in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)

|

Criminal

application

|

Duty to exercise reasonable care and diligence

|

N/A

|

Duty to act in good faith in the best interests of the

corporation and duty to act for proper purposes

|

Directors or other officers

|

|

Fault

elements

|

N/A

|

Recklessness or intentional dishonesty

|

||

|

Criminal

section

|

N/A

|

184(1)

|

||

|

Civil

application

|

Directors or other officers

|

Directors, other officers

|

||

|

Civil section

|

180(1)

|

181(1)

|

||

|

Duty

|

Must exercise their powers and discharge their duties with

the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise

if

they: (a) were a director or officer of a corporation in the corporation’s

circumstances; and (b) occupied the office held

by, and had the same

responsibilities within the corporation as, the director or officer.

|

Must exercise their powers and discharge their duties: (a)

in good faith in the best interests of the corporation; and (b) for a proper

purpose.

|

|

Criminal

application

|

Duty not to improperly use position

|

Directors, other officers or employees

|

Duty not to improperly use information

|

Directors, other officers or employees

|

|

Fault

Elements

|

Dishonesty and intention, or dishonesty and

recklessness

|

Dishonesty and intention, or dishonesty and

recklessness

|

||

|

Criminal

section

|

184(2)

|

184(3)

|

||

|

Civil

application

|

Directors, secretaries, other officers, employees (s

182(1)), or persons involved in a contravention of s 182(1) (caught under s

182(2))

|

Directors, other officers, employees (s 183(1)), or persons

involved in a contravention of

|

||

|

Civil section

|

182(1)

|

183(1)

|

||

|

Duty

|

Must not improperly use their position to: (a) gain an

advantage for themselves or someone else; or (b) cause detriment to the

corporation.

|

Must not improperly use information that has been obtained

because the person is or has been a director or other officer or employee

of a

corporation to: (a) gain an advantage for themselves or someone else; or (b)

cause detriment to the corporation.

|

|

Criminal

application

|

Duty to disclose material personal interests

|

Directors other than sole directors of proprietary companies

(ss 191(1), (5))

|

Duty not to be present at meetings and vote on matters

involving a material personal interest

|

Directors of public companies

|

|

|

Fault

elements

|

Combination of strict liability (s 191(1A)) and intention

(Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) sch 1 items 4.1, 5.1, 5.6)

|

Strict liability

|

|||

|

Criminal

section

|

191(1)

|

195(1)

|

|||

|

Civil

application

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|||

|

Civil section

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

|||

|

Duty

|

Must give other directors of the company notice in

accordance with s 191(3) of any material personal interest the director has in

a

matter that relates to the affairs of the company unless an exception pursuant

to s 191(2) applies.

|

Must not, in relation to a material personal interest the

director has in a matter that is being considered at a directors’

meeting:

(a) be present while the matter is being considered at the meeting; or (b) vote

on the matter (unless an exception pursuant

to

s 195(1A) applies).

|

|||

|

Criminal

application

|

Duty not to give a financial benefit to a related party of a

public company without member approval

|

Persons involved in a contravention of s 208 (caught under

s 209(3))

|

Duty to prevent insolvent trading by company

|

Directors

|

|

|

Fault

elements

|

Dishonesty

|

Combination of absolute liability, strict liability, actual

suspicion rather than actual or constructive awareness of reasonable grounds

for

suspicion, and dishonesty

|

|||

|

Criminal

section

|

208 and 209(3)

|

588G(3)

|

|||

|

Civil

application

|

Persons involved in a contravention of

s 208 (caught under s 209(2))

|

Directors

|

|||

|

Civil section

|

208 and 209(2)

|

588G(2)

|

|||

|

Duty

|

A public company, or an entity that the public company

controls, must not give a financial benefit to a related party of the public

company without obtaining member approval pursuant to s 208(1)(a) unless an

exception pursuant to s 208(1)(b) applies.

|

Must prevent the company from incurring a debt if the

company is insolvent or becomes insolvent by incurring that debt, or debts

including

that debt, and there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that the

company is insolvent or would so become insolvent and the director

is aware that

there are such grounds or a reasonable person in a like position in a company in

the company’s circumstances

would be so aware.

|

|||

For convenience, the duties examined in this article are referred to collectively as ‘directors’ duties’. However, as can be seen from Table 1, some of the duties apply to ‘officers’,[68] employees and ‘person[s] ... involved in a contravention’[69] of the duty as well as directors. The directors’ duties provisions that attract criminal liability also apply to persons who are subject to the extensions of criminal responsibility in pt 2.4 of the schedule of the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth). Using the term ‘directors’ duties’ to identify the duties set out in Table 1 is a common convention in academic and professional literature.[70]

All of the duties outlined in Table 1 are civil penalty provisions except ss 191 and 195. If a court is satisfied that a person has contravened a civil penalty provision, the court must make a declaration of contravention.[71] ASIC can then seek a pecuniary penalty order,[72] a disqualification order[73] or a compensation order.[74] Civil rules of evidence and procedure apply to the proceedings.[75] This means that there must be proof on the balance of probabilities[76] that there has been a contravention rather than proof beyond

reasonable doubt, which is the higher standard of proof that applies to

criminal proceedings.[77]

Where a court has declared that a person has contravened a civil penalty provision, the court may order that person to pay a pecuniary penalty of up to $200 000 to the Commonwealth if the contravention: materially prejudices the interests of the corporation or its members; materially prejudices the corporation’s ability to pay its creditors; or is serious.[78] The court may also disqualify that person from managing corporations for a period that the court considers appropriate if the court is satisfied that the disqualification is justified.[79] In determining whether the disqualification is justified, the court may have regard to: the person’s conduct in relation to the management, business or property of any corporation; and any other matters that the court considers appropriate.[80] If the corporation has suffered damage resulting from the contravention, the court may order the person to compensate the corporation for the damage.[81] The damage suffered by the corporation for the purposes of making a compensation order includes profits made by any person resulting from the contravention.[82]

All of the duties outlined in Table 1 are subject to criminal sanctions except s 180. Contraventions of directors’ duties provisions that attract criminal liability are prosecuted by the CDPP in accordance with the Prosecution Policy of the Commonwealth, which requires that, inter alia, there be sufficient evidence to prosecute and that prosecution be in the public interest.[83] Sections 184(1)–(3), 209(3) and 588G(3) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) are subject to the same sanctions. A person who contravenes any of these provisions may be fined up to 2000 penalty units ($360 000),[84] or imprisoned for up to five years, or both.[85] A contravention of s 191 can entail a fine of up to 10 penalty units ($1800) or imprisonment for three months, or both, while a contravention of s 195 can entail a fine of up to five penalty units ($900).[86]

In addition to criminal sanctions that are imposed for contraventions of directors’ duties under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), defendants are usually subject to an automatic five-year period of disqualification from managing corporations pursuant to s 206B. Convictions for contraventions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) that are punishable by imprisonment for a period greater than 12 months, and convictions for any offences that involve dishonesty and are punishable by imprisonment for at least three months,[87] result in an automatic five-year period of disqualification from managing corporations commencing either on the day on which the person was convicted, if the person does not serve a term of imprisonment, or the day on which they are released from prison, if the person does serve a term of imprisonment.[88] Thus, convictions for contraventions of all of the duties outlined in Table 1, except ss 191 (provided the offence does not involve dishonesty) and 195 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), result in a prohibition from managing corporations for a five-year period.

Criminal sanctions for contraventions of directors’ duties can also be imposed pursuant to the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth). The sanctions that were imposed for contraventions of directors’ duties during the 10-year study period included: discharge without conviction subject to a bond (s 19B); release without passing sentence subject to a bond (s 20(1)(a)); custodial sentence with release forthwith or after serving a specified period of imprisonment subject to a bond (s 20(1)(b)); community service order (s 20AB(1AA)(v)); periodic detention (s 20 AB(1AA)(xi)); and reparation to the Commonwealth or persons who have suffered loss by reason of the offence (s 21B).[89] Orders pursuant to ss 19B, 20(1)(a) and 20(1)(b) were mostly subject to good behaviour bonds[90] but can also involve conditions that the defendant make reparation,[91] pay pecuniary penalties (in the case of ss 20(1)(a) and 20(1)(b)),[92] and other conditions as the court thinks fit to specify in the order.[93] For ease of expression, orders pursuant to s 19B are herein referred to as ‘bonds without conviction’, orders pursuant to s 20(1)(a) as ‘bonds with conviction’, and orders pursuant to s 20(1)(b) that involve immediate release subject to a bond as ‘fully suspended’ custodial sentences.[94]

Contraventions of all of the duties outlined in Table 1 may form the basis, or a part of the basis, for administrative enforcement actions by ASIC. The two main types of administrative actions relevant to enforcement of directors’ duties are disqualification orders pursuant to s 206F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and enforceable undertakings pursuant to s 93AA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth).

Section 206F provides that ASIC may disqualify a person from managing corporations for up to five years if certain conditions are met and ASIC considers that disqualification is justified. These conditions include that, within the previous seven years, the person has been an officer of two or more corporations that have been wound up and liquidator reports under s 533(1) have been lodged in relation to the corporations’ inability to pay their debts.[95] In determining whether disqualification is justified, ASIC must have regard to whether any of the corporations were related and may have regard to the person’s conduct in relation to the management, business or property of any corporation, whether disqualification would be in the public interest, and any other matters that ASIC considers appropriate.[96] Section 206F gives ASIC a broad power that does not depend on contraventions of any particular provision. Accordingly, the basis for a disqualification order pursuant to s 206F may or may not include contraventions of directors’ duties provisions.

Enforceable undertakings are technically an administrative enforcement action in that they are accepted by ASIC pursuant to a statutory power.[97] However, ASIC cannot impose enforceable undertakings unilaterally, meaning that they are effectively a negotiated enforcement mechanism. Section 93AA(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) provides that: ‘ASIC may accept a written undertaking given by a person in connection with a matter in relation to which ASIC has a function or power under [that] Act.’ If ASIC considers that the person has breached the undertaking, it may apply to the court for various orders, including specific performance, disgorgement, compensation or any other order the court considers appropriate.[98] Enforceable undertakings are broad in scope, applying to a range of persons and types of misconduct, and as such, may

or may not involve contraventions of directors’ duties. While

enforceable undertakings can result in a wide range of obligations, undertakings involving contraventions of directors’ duties predominantly entail

disqualification outcomes.[99]

The rules of evidence do not apply to administrative hearings by ASIC.[100] Thus, it is not necessary for ASIC to prove factual matters (eg, contraventions of directors’ duties) on the balance of probabilities or beyond a reasonable doubt in order to make disqualification orders pursuant to s 206F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) or accept undertakings pursuant to s 93AA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth). Instead, findings of fact must be based on material that is ‘relevant, credible

and probative’.[101]

The enactment of the civil penalty regime in 1993 introduced a new approach to the enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies in Australia.[102] This Part of the article discusses the policy considerations that led to the enactment of the civil penalty regime and explains how they continue to inform current policies on the enforcement of corporate law. Three key policy considerations can be distilled from the Cooney Report and other extrinsic material — giving civil enforcement primacy over criminal enforcement, imposing sanctions in accordance with a pyramidal model of enforcement, and setting sanctions at a sufficient level to deter corporate misconduct — each of which is addressed in turn.

The primary motivation for the enactment of the civil penalty regime was the perception that existing criminal sanctions for the enforcement of directors’ duties were unsatisfactory. The Cooney Committee had three main concerns with criminal sanctions.

First, the Committee considered that it was ‘draconian’ to impose criminal sanctions in the absence of criminality,[103] and ‘only appropriate’ to impose such sanctions where the misconduct was ‘genuinely criminal in nature’.[104] In response to the tabling of the government response to the Cooney Report, Senator Cooney remarked that ‘[i]t is quite unfair that any sort of criminal penalty be attached to an act which really is not criminal in the sense that we understand it.’[105] By ‘genuinely criminal’ the Cooney Committee was referring to conduct that is fraudulent or dishonest, as opposed to negligent.[106] The inappropriateness of criminal sanctions for conduct that was not fraudulent or dishonest was raised on several occasions in submissions and evidence to the Cooney Committee.[107]

Second, the Committee was concerned that the ‘draconian’ nature of criminal sanctions, particularly custodial sentences, may deter people from pursuing directorships.[108] The Cooney Report stated that ‘the increased risk of going to gaol that comes with being a director is a disincentive to take on that role. People who would otherwise make good directors may decline a directorship because of this risk.’[109] The Committee cited the evidence of Robert Baxt, then Chairman of the Trade Practices Commission, on

this point.[110]

Third, the Committee took the view that criminal enforcement of directors’ duties had caused the law to ‘fall into disrepute’ as a result of judicial reluctance to impose ‘draconian’ custodial sentences and the use of ‘modest fines’ instead.[111] Prior to the 1993 reforms, fines for contraventions of directors’ duties were subject to statutory maxima ranging from $1000 to

$20 000.[112] The rarity of custodial sentences and insufficient levels of

fines were noted a number of times in submissions and evidence to

the Committee.[113]

The Cooney Committee viewed the civil penalty regime as the solution to the above concerns regarding existing criminal sanctions. Civil sanctions were seen as more appropriate for misconduct that was not genuinely criminal,[114] and as less of a disincentive to prospective directors.[115] In addition, civil sanctions were expected to overcome judicial reluctance regarding criminal sanctions — civil sanctions would be imposed more often than ‘draconian’ custodial sentences[116] and pecuniary penalties would be set higher than ‘modest fines’, as a result of the new $200 000 statutory maximum for civil pecuniary penalties.[117] Civil enforcement was to replace criminal enforcement as the predominant mode of enforcement for the ‘general run of cases’[118] and criminal liability would be reserved for more serious instances of misconduct.[119] The policy of using criminal enforcement for more serious misconduct was also reflected in the terms of the 1992 Memorandum of Understanding between the ASC and the CDPP, which stated that ‘civil proceedings will not be used in substitution for criminal proceedings in matters of serious corporate crime.’[120]

Current policy statements on the balance between civil and criminal enforcement continue to reflect the policy considerations that led to the enactment of the civil penalty regime. The 2006 Memorandum of Understanding between ASIC and the CDPP, like its 1992 predecessor, states that ‘[c]ivil proceedings will not be used in substitution for criminal proceedings in matters of serious corporate or financial services crime.’[121] Similarly, ASIC’s 2013 enforcement policy states that it ‘pursue[s] substantial criminal remedies for the most serious misconduct’.[122] Consistent with the rationale underpinning the Cooney Report, the Explanatory Memorandum to the Corporations Legislation Amendment (Financial Services Modernisation) Bill 2009 (Cth) states that ‘[t]he intention of the dual regime [of civil and criminal sanctions] is to give primacy to the civil penalty regime and retain criminal penalties for serious breaches of the Act.’[123] This policy consideration is also implicit in the text of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which, as detailed in Table 1, requires proof of additional fault elements (ie, more serious misconduct) in order to establish criminal liability.[124]

Responsive regulation theory underpinned the enactment of the civil penalty regime in 1993. The Cooney Report emphasised the need to have a range of civil[125] and criminal[126] sanctions of varying degrees of severity which can be tailored to the circumstances of the misconduct.[127] In particular, it was envisaged that sanctions would be imposed in accordance with a pyramidal model of enforcement.[128] This Part of the article briefly explains responsive regulation and pyramidal enforcement and discusses how they continue to inform current policies on the enforcement of corporate law.[129]

The basic concept of responsive regulation is that regulation is most likely to be effective when it is responsive to the regulatory environment and the actions of the regulated entity.[130] Responsive regulation theory has been applied in a range of different areas of regulation in Australia and overseas, including public health and safety, social services and welfare, environmental protection, transport, communications and media, and corporations and finance.[131] Pyramidal enforcement models, which form part of the broader theory of responsive regulation,[132] are comprised of two core concepts, one prescriptive and the other predictive.

The prescriptive concept (which is the vertical aspect of the pyramid) is that a regulator should possess a range of sanctions and regulatory strategies that are hierarchically ordered according to their degree of interventionism (ie, severity or intensity) and, as a general presumption,[133] should attempt sanctions and strategies of a lesser degree of interventionism before escalating to more interventionist sanctions and strategies, which are only used if the less interventionist sanctions and strategies fail.[134] The regulator escalates up the hierarchy of sanctions and strategies only as necessary to achieve compliance on the part of the regulated entity.[135]

The predictive concept is the horizontal aspect of the enforcement pyramid. If a regulator follows the prescriptive aspect of pyramidal enforcement, the theory predicts that there will be an inverse correlation between the severity of the sanction or strategy and the frequency with which the sanction or strategy is applied (ie, the more severe the sanction or strategy, the less frequently it is applied).[136] This prediction is, broadly speaking, based on rational choice theory, which assumes that most actors are rational and that rational actors will weigh the gains of breaking the law against the costs of being subjected to law enforcement. As the sanctions become more severe, the rationality of breaking the law decreases and the frequency of misconduct that attracts such sanctions decreases accordingly.[137]

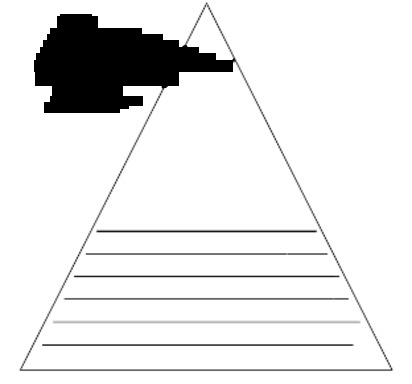

The following is a basic example of a pyramid of sanctions, depicting the prescriptive vertical aspect and predictive horizontal aspect.

Figure 1: Example of a Pyramid of Sanctions.

This image comes from Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite, Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate (Oxford University Press, 1992) 35

Pyramidal enforcement theory is concerned only with the severity and frequency of sanctions, as depicted in Figure 1, and regulatory strategies.[138] ‘Sanction’ refers to the particular enforcement outcome, while ‘regulatory strategy’ refers to the regulatory method via which the outcome was achieved, such as: ‘command regulation with non-discretionary punishment’ (eg, mandatory sanctions imposed pursuant to legislation); ‘command regulation with discretionary punishment’ (eg, sanctions imposed pursuant to legislation but subject to judicial discretion); ‘enforced self-regulation’ (eg, enforceable undertakings); and ‘self-regulation’ (eg, organisational codes of conduct).[139] Pyramidal enforcement theory is not concerned with legal jurisdictions, such as criminal, civil and administrative law. Jurisdictions are only relevant to the extent that they reflect upon the severity of the sanctions and regulatory strategies utilised within jurisdictions. In Figure 1 ‘criminal penalty’ is situated above ‘civil penalty’ based on the assumption that criminal penalties will typically be more severe than civil ones, not based on the nature of the jurisdictions. Indeed, as Figure 1 shows, sanctions that can be imposed via administrative means, such as licence suspensions and revocations,[140] may be regarded as more severe than criminal and civil sanctions. In designing a model pyramid of sanctions, the relevant criterion is the severity of each type of sanction, not the jurisdictions to which they belong.[141]

The Cooney Committee was strongly influenced by responsive regulation theory, in particular by the concept of a pyramidal model of sanctions. Civil sanctions were recommended with a view to creating a ‘pyramid of enforcement ... with civil measures at the base of the pyramid for the general run of cases, and criminal liability at the apex for the more exceptional instances of law-breaking.’[142] It was envisaged that civil sanctions, which were assumed to be less severe than criminal sanctions,[143] would occupy a lower rung on the enforcement pyramid and therefore be imposed more frequently than criminal sanctions, as discussed in Part III(A). The Cooney Report and other extrinsic material also indicated an intention that, within the criminal and civil jurisdictions, the particular sanctions would be hierarchically ordered according to the severity of the misconduct. Standalone declarations of contravention would be imposed for ‘non-serious’ breaches, while civil pecuniary penalties or disqualification orders would be imposed for ‘serious’ breaches.[144] Criminal sanctions would range from fines, to community service orders, to custodial sentences, depending on the severity of

the offence.[145]

Responsive regulation and pyramidal enforcement theory continue to inform current policies on the enforcement of corporate law. ASIC’s enforcement policy states that it ‘can pursue a variety of enforcement remedies, depending on the seriousness and consequences of the misconduct’ and ‘will pursue the enforcement remedies best suited to the circumstances of the case’.[146] Recent reports and submissions by ASIC have emphasised that it is ‘[c]entral to effective enforcement’ to have a ‘range of penalties’ that allow ‘ASIC to calibrate [its] response with sanctions of greater or lesser severity commensurate with the misconduct’.[147] ASIC has recently commented that:

the introduction of civil penalties provided another step in the ‘pyramid of enforcement’ whereby serious misconduct (such as director negligence) could be met with substantial penalties, but without the moral opprobrium of a criminal conviction or a custodial sentence.[148]

The role that responsive regulation and pyramidal enforcement play in ASIC’s current enforcement policy is recognised in the final report of the Senate Economics References Committee’s 2014 Inquiry into the Performance

of ASIC:

The sanctions made available to ASIC in legislation, and the enforcement policy developed and published by ASIC, reflect many aspects of responsive regulation. ASIC’s enforcement pyramid includes: punitive action (prison sentences, criminal or civil monetary penalties), protective action (such as disqualifying orders), preservative action (such as court injunctions), corrective action (such as corrective advertising), compensation action and negotiated resolution (such as an enforceable undertaking).[149]

The report further notes that ‘[t]he enforcement pyramid model of sanctions of escalating severity is a sound foundation for enabling a regulator to address corporate misconduct. The application of this model to Australia’s corporate laws has generally proven effective.’[150] The role of responsive regulation in relation to ASIC’s enforcement policies and practices has also been widely acknowledged by academic commentators, in particular the idea that

sanctions should be imposed in accordance with a pyramidal model

of enforcement.[151]

A key expectation underlying the Cooney Committee’s reasoning in recommending the civil penalty regime was that civil monetary sanctions would be set at a higher level than the ‘modest fines’ that had previously been imposed by the judiciary.[152] The Cooney Report emphasised that penalties ‘will have no deterrent value if their level is insufficient.’[153] The government’s response to the Cooney Report similarly emphasised the importance of setting civil monetary sanctions at an appropriate level:

the Government is concerned to demonstrate clearly the seriousness with which it regards directors’ duties. The Government accordingly proposes that the maximum monetary penalty for breach of section 232 [the predecessor of ss 180–3] should be set at $200 000 ...[154]

Concerns were also raised in evidence to the Cooney Committee regarding the level of custodial sentences and the prospect of recidivism, with a number of witnesses and committee members suggesting that civil penalties may prove to be a more effective deterrent than custodial sentences.[155] Senator Robert Hill noted that it had been put to the Committee that ‘these matters [directors’ duties matters] should really be seen more as a civil type of action than a criminal action and that large monetary penalties would probably prove the most effective deterrent for breach.’[156]

It remains a central focus of current enforcement policies that sanctions be set at a sufficient level to deter corporate misconduct, with a particular emphasis on general deterrence.[157] ASIC’s enforcement policy states that it ‘use[s] enforcement to deter misconduct’,[158] and stresses the ‘high [civil] penalties that apply if the case is proved’[159] and ‘high monetary penalties’[160] imposed in response to serious misconduct. The policy states that civil pecuniary penalties can be up to $200 000[161] and dishonest breaches of the duty of good faith may incur fines of up to $340 000.[162] In its submission to the Financial System Inquiry, ASIC asserted that ‘[c]entral to effective enforcement are penalties set at an appropriate level’,[163] and recommended, among other things, a review of the $200 000 statutory maximum for civil penalties, which was set in 1993 and has not been adjusted for inflation.[164]

Current policy statements also emphasise the magnitude and deterrence value of custodial sentences. ASIC’s enforcement policy highlights the ‘substantial criminal remedies’ that are imposed for ‘the most serious misconduct’, giving the example of imprisonment for up to five years as a result of insolvent trading or a breach of the duty of good faith.[165] In its submission to the 2015–16 Senate Inquiry into Penalties for White-Collar Crime, the CDPP commented that ‘“general deterrence” is the primary sentencing objective’ and that, as a result of sentencing principles associated with this objective, ‘individuals who are convicted of serious white-collar crimes are routinely sentenced to significant terms of imprisonment with time to serve.’[166] The CDPP went on to state that ‘[a]rguably, nothing deters would-be white-collar criminals more than a realistic prospect of imprisonment.’[167]

The following Part of this article examines the above policy statements with reference to the empirical evidence, along with those relating to the primacy of civil enforcement and the application of a pyramidal model of sanctions, as discussed in Parts III(A) and III(B) respectively. The evidence indicates that the enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory authorities diverged significantly from these policy considerations during the 10-year study period.

This Part of the article empirically analyses the extent to which the policy considerations relating to the enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies, as discussed in Part III, have been applied in practice. This analysis is conducted by reference to a 10-year dataset of civil, criminal and administrative matters brought by ASIC and the CDPP that were finalised between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014. It begins with an explanation of the method used to collect and classify the data and then presents the research findings as they relate to each of the three key policy considerations discussed in Part III.

The authors’ research located 27 civil matters (involving 78 defendants) and 72 criminal matters (involving 83 defendants)[168] brought by ASIC and the CDPP in which a final judicial determination was made between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014 as to whether or not there was a contravention of the following provisions: ss 180–4, 191, 195, 209 and 588G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The dataset of civil and criminal matters only includes those matters in which a final judicial determination was made; it does not

include interlocutory proceedings or matters that were discontinued

or settled.

The relevant date for the purposes of inclusion in the dataset was the date of the final judicial determination, not the date of commencement of proceedings. In a number of instances, the proceedings commenced prior to the study period (ie, prior to 1 January 2005), as the enforcement processes in directors’ duties matters can be protracted. In respect of superior court matters, the average duration of the civil and criminal enforcement processes from the date of the earliest contravention documented in the judgment to the final determination was 6.9 and 7.9 years respectively.[169]

In order to achieve comprehensive coverage of civil and criminal directors’ duties matters, it was necessary to collect the data using case law databases and freedom of information legislation. An alternative method would have been to rely on ASIC’s media releases. However, the authors’ research shows that, while 100 per cent of civil matters were covered in ASIC’s media releases, only 88.88 per cent of criminal matters were covered. Furthermore, the information contained in ASIC’s media releases is general in nature and a number of discrepancies between media releases and court judgments were identified. As such, ASIC’s media releases cannot be regarded as a

comprehensive source of data on the civil and criminal enforcement of

directors’ duties.

The dataset contains judgments from superior courts, encompassing supreme courts, courts of appeal and federal courts, and judgments from inferior courts, encompassing district or county courts and local or magistrates’ courts. Superior court judgments were identified using the LexisNexis AU, Westlaw AU, Australasian Legal Information Institute (‘AustLII’) and JADE Professional case law databases. A freedom of information request to the CDPP pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Cth) was used to obtain data in relation to inferior court judgments, as such judgments are not usually available on case law databases.[170] In some instances, ASIC’s media releases were consulted to confirm or supplement the data obtained via the case law research and freedom of information application.

In total, the dataset contains 51 superior court matters (involving 107 defendants) and 48 inferior court matters (involving 54 defendants).[171] ‘Matters’ and ‘defendants’ have been classified as follows. Directors’ duties proceedings are typically divided into separate judgments for liability and penalties. Consequently, the judgments fall into three broad categories: ‘unproven liability judgments’ (ie, judgments in which ASIC or the CDPP fails to establish the liability of any of the defendants); ‘proven liability judgments’ (ie, judgments in which ASIC or the CDPP succeeds in establishing the liability of all or some of the defendants); and ‘penalty judgments’ (ie, judgments in which sanctions are imposed on defendants who were found liable in proven liability judgments). The 99 ‘matters’ in the dataset are comprised of ‘penalty judgments’[172] — which are referred to throughout the article as ‘proven matters’ — and ‘unproven liability judgments’ — which are referred to as ‘unproven matters’. ‘Proven liability judgments’ have not been included in the number of matters, as this would artificially inflate the number of matters by counting each proven matter twice, once for the ‘proven liability judgment’ and once for the ‘penalty judgment’. However, where a ‘proven liability judgment’ involved some defendants who were not found liable, these defendants have been counted in the number of defendants. Defendants have been classified as follows: ‘liable defendants in proven matters’ (indicating defendants in ‘penalty judgments’); ‘non-liable defendants in proven matters’ (indicating defendants who were not found liable in ‘proven liability judgments’); and ‘defendants in unproven matters’ (indicating defendants in ‘unproven liability judgments’).[173]

Only ‘penalty judgments’ and ‘unproven liability judgments’ that involved a final judicial determination as to the penalty to be imposed on the defendant (in the case of ‘penalty judgments’) or the defendant’s liability (in the case of ‘unproven liability judgments’) have been counted as ‘matters’. Thus, ‘penalty judgments’ and ‘unproven liability judgments’ that were overridden by subsequent appeals have not been counted as separate ‘matters’. For example, in the proceedings involving Fortescue Metals Group Ltd, CEO Andrew Forrest was found not liable at first instance,[174] liable on appeal to the Full Federal Court,[175] and not liable on appeal to the High Court.[176] These proceedings have been counted as one ‘unproven matter’ for the final ‘unproven liability judgment’ of the High Court.

In relation to proceedings in which some defendants appealed but others did not, each judgment that was the final judgment for one or more of the defendants was counted as a separate ‘matter’. For example, in the proceedings relating to James Hardie Industries Ltd, the CEO Peter MacDonald did not appeal the first instance decision[177] and the CFO Phillip Morley only appealed to the New South Wales Court of Appeal,[178] while the remaining eight defendants (the seven non-executive directors and the defendant who was both the company secretary and general counsel) appealed to the High Court.[179] These proceedings have been counted as three ‘proven matters’, one for the MacDonald ‘penalty judgment’, one for the Morley ‘penalty judgment’, and one for the ‘penalty judgment’ relating to the eight remaining defendants.

As discussed in Part II(B)(3), the two main types of administrative enforcement actions relevant to enforcement of directors’ duties are disqualification orders pursuant to s 206F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and enforceable undertakings pursuant to s 93AA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth). The authors’ research identified 199 administrative matters (involving 199 defendants) that expressly involved contraventions of directors’ duties,[180] including 191 final disqualification orders made pursuant to s 206F and eight enforceable undertakings accepted pursuant

to s 93AA.

Data on the overall number of s 206F orders was requested from ASIC and provided in the form of a ‘Corporations Register’ setting out company directors and other officers that have been disqualified under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).[181] Based on this ‘Corporations Register’ and the case law data described in Part IV(A)(1), it is estimated that there were 610 final disqualification orders made pursuant to s 206F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) during the 10-year study period.[182] Of these 610 final orders, 15 were identified[183] as appeals to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal and one as an appeal to the Full Federal Court.[184] However, the ‘Corporations Register’ provided by ASIC did not identify the basis for the s 206F orders, which,

as discussed in Part II(B)(3), may or may not involve contraventions of

directors’ duties.

ASIC’s media releases are the only currently available source of data on the basis for orders made pursuant to s 206F, with the exception of appeals, some of which are reported on case law databases.[185] During the study period, there were 263 orders made pursuant to s 206F that were reported in ASIC’s media releases and a further six orders reported on case law databases that were not reported in media releases. Of these 269 reported orders, contraventions of directors’ duties were expressly identified[186] as the basis, or a part of the basis, for the order in relation to 191 of the orders. Thus, there were at least 191 final orders made pursuant to s 206F involving contraventions or suspected[187] contraventions of directors’ duties. However, given the significant proportion of the 269 reported orders that expressly involved contraventions of directors’ duties (191 of 269, or about 71 per cent), it is likely that the true number of s 206F orders involving contraventions of directors’ duties was considerably higher than 191, keeping in mind that the 269 reported orders represent only about 44 per cent of the estimated total of 610 orders. Since the main precondition for an order pursuant to s 206F is that the person in question has been an officer of two or more failed corporations within the previous seven years,[188] it is not surprising that a significant proportion of such matters involve contraventions of directors’ duties.

The data on enforceable undertakings presented in this article was collected from ASIC’s Enforceable Undertakings Register.[189] From 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2014, ASIC accepted 26 enforceable undertakings from directors and 16 enforceable undertakings from directors in conjunction with companies. Of the 26 enforceable undertakings given by directors, eight of the undertakings (each involving one director) expressly identified contraventions of directors’ duties as the misconduct, or a part of the misconduct, that gave rise to the undertaking.[190] None of the 16 enforceable undertakings given by directors in conjunction with companies expressly identified contraventions of directors’ duties as a basis for the undertaking.

The eight enforceable undertakings involving contraventions of directors’ duties resulted in various disqualification outcomes, including undertakings not to: manage corporations; give financial advice; deal in financial services; operate a registered managed investment scheme; carry on a financial services business; be involved in the management of a financial services business; apply for an Australian Financial Services Licence; and be an authorised representative of an Australian Financial Services Licensee. The duration of the disqualification outcomes ranged from 18 months to permanent disqualification. Only two of the undertakings involved outcomes other than disqualification (one training requirement and one peer review requirement). Thus, enforceable undertakings primarily served as another administrative avenue, in addition to s 206F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), via which ASIC sought to achieve disqualification outcomes.

The data indicates that the three key policy considerations discussed in Part III have, to a large extent, not been applied in practice: civil enforcement was significantly less prevalent than criminal enforcement, despite the ostensible primacy of civil enforcement; the majority of sanctions were incapacitative, which is contrary to a pyramidal model of enforcement; and monetary sanctions and custodial sentences were set well below the statutory maxima, casting doubt on their deterrence value. This Part of the article analyses each policy consideration in turn by reference to the empirical data.

Policy statements on the enforcement of corporate law indicate that civil enforcement is to be given primacy over criminal enforcement and that the latter is to be used for more serious misconduct. As noted in Part III(A), this policy is also implicit in the text of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which requires proof of additional fault elements (ie, more serious misconduct) in order to establish criminal liability. Such policy statements suggest that civil enforcement ought to be more prevalent than criminal enforcement;[191] however, the data indicates that criminal enforcement is the more prevalent mode of enforcement.

The most basic indicator of the prevalence of civil and criminal enforcement of directors’ duties is how frequently contraventions of civil and criminal provisions are proven. Table 2 displays the number of times that a contravention of each of the directors’ duties provisions was proven. The ‘number of times’ refers to the number of matters in which a contravention of each provision was proven. This should not be confused with the number of proven matters, as set out in Table 3.[192]

Table 2: Number of Times a Contravention of Each Directors’

Duties Provision Was Proven

|

Section(s)

|

No of times civil

duty contravened

|

No of times criminal

duty contravened

|

|

180

|

18

|

N/A

|

|

181/184(1)

|

11

|

13

|

|

182/184(2)

|

10

|

50

|

|

183/184(3)

|

2

|

0

|

|

191

|

N/A

|

0

|

|

195

|

N/A

|

0

|

|

209(2)/209(3)

|

3

|

0

|

|

588G(2)/588G(3)

|

1

|

2

|

|

Total

|

45

|

65

|

Table 2 shows that a contravention of a criminal provision was proven 65 times, while a contravention of a civil provision was only proven 45 times. This disparity is even greater based on a direct comparison between provisions that attract both civil and criminal liability. Excluding ss 180, 191 and 195, which do not attract both types of liability, criminal enforcement accounted for 65 of 92 times that a contravention of a directors’ duties provision was proven (70.65 per cent). Figure 2 presents the data from Table 2 in chart form.

Figure 2: Number of Times a Contravention of Each Directors’ Duties

Provision Was Proven

Table 3 presents a more detailed comparison of civil and criminal enforcement in the form of an analysis of the number and percentage of matters and defendants within each jurisdiction.

Table 3: Number and Percentage of Directors’ Duties Matters and Defendants within Civil and Criminal Jurisdictions

|

Matters and defendants

|

Civil

|

Criminal

|

Total

|

|

Proven matters

|

24 (27.59%)

|

63 (72.41%)

|

87

|

|

Unproven matters

|

3 (25%)

|

9 (75%)

|

12

|

|

All matters

|

27 (27.27%)

|

72 (72.73%)

|

99

|

|

Liable defendants in

proven matters

|

72 (50.7%)

|

70 (49.3%)

|

142

|

|

Non-liable defendants in

proven matters

|

2 (100%)

|

0 (0%)

|

2

|

|

Defendants in unproven matters

|

4 (23.53%)

|

13 (76.47%)

|

17

|

|

All defendants

|

78 (48.45%)

|

83 (51.55%)

|

161

|

Table 3 indicates that criminal enforcement was more prevalent than civil enforcement when the data is analysed according to the number of matters. Almost three quarters of proven matters were criminal (63 of 87, or 72.41 per cent). There is less of a disparity between civil and criminal enforcement when the data is analysed according to the number of defendants. A little over half of the liable defendants were civil (72 of 142, or 50.7 per cent). The reason for this difference is that civil matters often involved multiple defendants, whereas criminal matters usually only involved one defendant. Figure 3 sets out the data on the total number of matters and defendants in chart form.

Figure 3: Number of Directors’ Duties Matters and Defendants within

Civil and Criminal Jurisdictions

While Table 3 shows that the overall number of civil defendants found liable was slightly higher than the number of criminal defendants found liable, this is only due to the significant number of matters involving s 180, which does not attract criminal liability. Based on a direct comparison of directors’ duties provisions which attract both civil and criminal liability, criminal enforcement was significantly more prevalent in all of the data categories. Table 4 is a variation on Table 3 which excludes matters in which ss 180, 191 and 195 were the only directors’ duties provisions contravened or allegedly contravened, as these provisions do not attract both types of liability.

Table 4: Number and Percentage of Directors’ Duties Matters and Defendants within

Civil and Criminal Jurisdictions (Excluding Sections 180, 191 and 195)

|

Matters and defendants

(excluding sections 180, 191

and 195)

|

Civil

|

Criminal

|

Total

|

|

Proven matters

|

15 (19.23%)

|

63 (80.77%)

|

78

|

|

Unproven matters

|

1 (10%)

|

9 (90%)

|

10

|

|

All matters

|

16 (18.18%)

|

72 (81.82%)

|

88

|

|

Liable defendants in proven matters

|

45 (39.13%)

|

70 (60.87%)

|

115

|

|

Non-liable defendants in proven matters

|

1 (100%)

|

0 (0%)

|

1

|

|

Defendants in unproven matters

|

1 (7.14%)

|

13 (92.86%)

|

14

|

|

All defendants

|

47 (36.15%)

|

83 (63.85%)

|

130

|

Table 4 indicates that criminal enforcement was significantly more prevalent than civil enforcement based on a direct comparison of provisions that attract both types of liability. Sixty-three of 78 proven matters were criminal (80.77 per cent), while 70 of 115 liable defendants were criminal (60.87 per cent). Figure 4 sets out these results in chart form.

Figure 4: Number of Directors’ Duties Matters and Defendants within Civil and Criminal Jurisdictions (Excluding Sections 180, 191 and 195)

Based both on the number of proven contraventions[193] and the number of matters and defendants within each jurisdiction,[194] it is clear that civil enforcement does not occupy a position of primacy over criminal enforcement.[195] The practice of enforcement is therefore inconsistent with the stated policies, as discussed in Part III(A), in respect of the balance between civil and criminal enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies.

As discussed in Part III(B), a key policy consideration that led to the enactment of the civil penalty regime, which continues to inform current policies on the enforcement of corporate law, is that there should be a range of sanctions of varying levels of severity and that the severity of the sanctions should be calibrated to the severity of the misconduct. Pyramidal enforcement theory predicts that, if a range of sanctions is calibrated in this manner, enforcement activity will be distributed in a ‘pyramid of enforcement’ in which the severity of sanctions is inversely correlated with the frequency with which they are applied (ie, the more severe the sanctions, the less frequently they are applied). This Part of the article analyses whether, as one would expect based on the stated policies, enforcement activity is distributed in accordance with a pyramidal model of enforcement.

The starting point for this analysis is to determine the model pyramid of sanctions with which the imposition of sanctions ought to comply, as set out in Figure 5. The vertical aspect of the pyramid arranges the civil, criminal and administrative sanctions that were imposed for contraventions of directors’ duties during the 10-year study period in order of their severity. As discussed in Part III(B), pyramidal enforcement theory is concerned with the severity of the sanctions, not the legal jurisdictions to which the sanctions belong, which explains why the sanctions are not arranged along strictly jurisdictional lines in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Model Pyramid of Sanctions for Contraventions of Directors’ Duties

Provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)

The severity of the sanctions set out in Figure 5 has been determined according to the severity of the primary sanctions, without taking into account the potential secondary sanctions that could be imposed for failure to comply with the primary sanctions. For example, failure to comply with a bond without conviction could potentially result in imprisonment,[196] as could failure to comply with a disqualification order made by ASIC pursuant to s 206F of the Corporations Act.[197] It is not possible to design a model pyramid of primary sanctions that factors in the potential ‘additional severity’ of secondary sanctions, as the additional severity will be present in some cases but not others, contingent on whether the defendant complies with the primary sanctions. It would in theory be possible to design a separate model pyramid of secondary sanctions applying only to the subset of defendants who do not comply with primary sanctions. However, this would be a fruitless exercise from the perspective of pyramidal enforcement theory, which is premised on the assumption that most actors are rational and will weigh up the benefits and costs of non-compliance.[198] If the subset of defendants is wholly comprised of those who have breached primary sanctions, the assumption of rationality no longer holds true and so a pyramid of secondary sanctions is unlikely to be the best method of preventing further reoffending.

Custodial sentences involving a minimum period of incarceration[199] are the most severe sanctions that can be imposed for contraventions of directors’ duties, as deprivation of liberty is the strongest possible enforcement outcome available in Australia. The next most severe group of sanctions is criminal sanctions that involve convictions but not incarceration. These sanctions entail the following: the sanction itself, such as a fine,[200] reparation order,[201] community service order,[202] fully suspended sentence,[203] or standalone bond;[204] an automatic five-year period of disqualification pursuant to s 206B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (with the exception of offences against ss 191 and 195);[205] and potential disadvantages associated with a criminal conviction, such as stigmatisation, discrimination and restrictions in relation to employment.[206] Fines are situated above reparation as they constitute an additional punitive monetary penalty, rather than simply compensation for losses caused by the offence. Community service orders are placed above fully suspended sentences and standalone bonds, as they involve positive duties, whereas fully suspended sentences and standalone bonds typically involve only a negative duty to refrain from unlawful behaviour.[207] The secondary sanctions applying to breach of a fully suspended sentence may be more severe than those applying to breach of non-custodial criminal orders;[208] however, as discussed above, the pyramid of enforcement assumes compliance with primary sanctions, so the potentially greater severity of secondary sanctions applying to fully suspended sentences is not a relevant consideration for present purposes.

Non-criminal incapacitative sanctions (ie, disqualification outcomes) are the next most severe group of sanctions, as incapacitation is typically regarded as a stronger enforcement outcome than outcomes that are solely monetary.[209] Civil disqualification orders are the most severe of the disqualification outcomes, as they involve significant legal costs and there is no maximum period of disqualification pursuant to s 206C(1). Administrative disqualification orders pursuant to s 206F(1) involve fewer legal costs and have a maximum duration of five years. Negotiated disqualification outcomes resulting from enforceable undertakings are less severe than disqualification orders pursuant to s 206F of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) in the sense that, although they are not limited in duration, they cannot be unilaterally imposed by ASIC.[210]

The least severe group of sanctions are those that are solely monetary (ie, civil pecuniary penalties[211] or compensation orders)[212] or those that entail minimal substantive detriment to the defendant (ie, criminal bonds without conviction[213] and standalone civil declarations of contravention).[214] Civil pecuniary penalties are situated above civil compensation orders for the same reason that criminal fines are situated above reparation. Bonds without conviction are placed above standalone declarations of contravention, as they at least require a negative duty on the part of the defendant to refrain from unlawful behaviour, whereas declarations of contravention do not impose

any duties.[215]

Having set out the model enforcement pyramid, the next step in the analysis is to determine whether the sanctions that were imposed during the study period conform to that pyramid. Table 5 presents the number of defendants upon whom each type of sanction was imposed. The order of the rows in Table 5 corresponds to the rungs of the pyramid set out at Figure 5.

Table 5: Number of Sanctions Imposed for Contraventions of Directors’ Duties

|

Sanction

|

Defendants

|

|

Custodial sentence with a minimum period of

incarceration (criminal)

|

43[216]

|

|

Fine (criminal)

|

4

|

|

Reparation order (criminal)

|

7

|

|

Community service order (criminal)

|

1

|

|

Fully suspended custodial sentence (criminal)

|

20

|

|

Standalone bond with conviction (criminal)

|

1

|

|

Disqualification order (civil)

|

63

|

|

Disqualification order pursuant to s 206F

(administrative)

|

At least

191[217]

|

|

Disqualification outcome via enforceable undertaking

(administrative)

|

8

|

|

Pecuniary penalty (civil)

|

34

|

|

Compensation order (civil)

|

5

|

|

Bond without conviction (criminal)

|

3

|

|

Standalone declaration of contravention (civil)

|

7

|

|

Total

|

387[218]

|

Table 5 shows that the sanctions imposed during the study period do not conform to the model pyramid of sanctions set out at Figure 5. There was a predominance of imprisonment and disqualification (ie, incapacitative sanctions) and relatively infrequent use of other forms of sanctions. The total number of civil and criminal sanctions imposed was 188. Of these sanctions, 106 were custodial sentences involving a minimum period of incarceration and civil disqualification orders collectively, meaning that over half of all civil and criminal sanctions were incapacitative (56.38 per cent). If administrative sanctions are included in the sample, disqualification alone accounted for at least 67.7 per cent of all sanctions (262 of 387) and disqualification and custodial sentences involving a minimum period of incarceration collectively accounted for at least 78.81 per cent of all sanctions (305 of 387). This data runs contrary to a pyramidal model of enforcement, as incapacitative sanctions are typically situated at the peak of enforcement pyramids and therefore ought to be imposed the least frequently.[219]

Figure 6 sets out the data in Table 5 in chart form, facilitating comparison with the model pyramid of sanctions depicted at Figure 5. If the sanctions had been imposed in accordance with a pyramidal model of enforcement, the rows of Figure 6 would increase in length from the top to the bottom of

the chart.

Figure 6: Number of Sanctions Imposed for Contraventions of Directors’ Duties

Figure 6 clearly shows that the application of sanctions for contraventions of directors’ duties during the 10-year study period did not conform to a pyramidal model of enforcement. For the reasons discussed in Part III(B), that the bulk of incapacitative sanctions were administrative sanctions has little bearing on whether the application of sanctions is consistent with pyramidal enforcement, which is concerned with the severity of sanctions, not legal jurisdictions. The data therefore reveals a rift between the stated policies on responsive regulation and pyramidal enforcement theory, as discussed in Part III(B), and the reality of enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies in Australia.

One of the Cooney Committee’s key expectations in recommending the civil penalty regime was that civil pecuniary penalties would be set at a higher level than previously ‘modest’ criminal fines. Concerns were also raised in evidence to the Committee as to the adequacy of the duration of custodial sentences.[220] The Cooney Report emphasised that penalties ‘will have no deterrent value if their level is insufficient.’[221] Deterrence remains a central focus of current policies on corporate law enforcement, as discussed in Part III(C), with ASIC’s enforcement policy stressing the ‘high monetary penalties’[222] that are imposed and the CDPP stating that ‘individuals who are convicted of serious white-collar crimes are routinely sentenced to significant terms of imprisonment with time to serve.’[223] This Part of the article empirically analyses the magnitude of monetary sanctions and custodial sentences against the statutory maxima to determine the extent to which enforcement of directors’ duties by statutory agencies is consistent with this policy of deterrence.

Table 6 presents the average, median and highest civil pecuniary penalties and criminal fines that were imposed on defendants who contravened directors’ duties provisions (but did not contravene any other provisions that attract pecuniary penalties or fines).

Table 6: Magnitude of Monetary Sanctions Imposed for

Contraventions of Directors’ Duties

|

Magnitude of monetary sanctions

|

Civil pecuniary penalties

|

Criminal fines

|

|

Defendants with a single contravention or count

|

||

|

Average

|

$25 000 (n=11)

|

Insufficient data

|

|

Median

|

$25 000 (n=11)

|

Insufficient data

|

|

Highest

|

$40 000

|

$10 000

|

|

Defendants with multiple contraventions or counts

|

||

|

Average

|

$177 875 (n=16)

|

Insufficient data

|

|

Median

|

$145 000 (n=16)

|

Insufficient data

|

|

Highest

|

$500 000

|

$75 000

|

|

All defendants

|

||

|

Average

|

$115 593 (n=27)

|

$42 500 (n=2)

|

|

Median

|

$50 000 (n=27)

|

$42 500 (n=2)

|

|

Highest

|

$500 000

|

$75 000

|