Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

Fady JG Aoun[1]*

The colonial and Commonwealth Trade Mark Registers reveal an extensive and neglected history of stigmatising representations of marginalised groups. This article documents part of this history. It presents a selection of objectionable racist and sexist trade marks within their socio-historical contexts, and comments on their lingering effects in

the Australian public sphere. For marginalised groups, these stigmatising trade marks

and associated commercial imagery contributed to the promulgation of enduring

racist and sexist tropes in the Australian public sphere, notwithstanding historical and contemporary objections to such pernicious representations. Coming to terms with the communicative and other damage caused by stigmatising trade marks not only helps us to grapple with their destructive legacy, but also underscores the importance of ensuring proactive legislative or practical administrative prescriptions in safeguarding the interests of stigmatised groups in the trade mark registration system.

Readers are advised that this article contains highly offensive, demeaning and derog-atory representations of Indigenous Australians, Black and ethnic minorities. While these may cause offence, they have been included here so as to provide a more accurate historic account of the Register.

Contents

The often championed and widely held view is that the Register of Trade Marks (the ‘Register’) is an unmitigated public good: a source of valuable (albeit imperfect) information, as well as a historic record of proprietary rights. Government bureaucracies charged with managing intellectual prop-erty (‘IP’) rights frequently emphasise that trade marks are also benign: ‘[T]hrough their proliferation and diversity’ they play an ‘important part’ in the ‘growth of trade in Australia and the development of our economy’.[1] If IP Australia’s website contains a selection of famous Australian trade marks and reflects its hall of fame,[2] this article, by contrast, documents the Register’s hall of shame. The purpose of this article is to provide a more critical assessment of registrable marks than the celebratory narrative offered by IP Australia. The historical record suggests that dehumanising, derogatory and disparaging trade marks — what this article calls ‘stigmatising trade marks’ — are a longstanding and integral part of the history of the Register. The research on stigmatising marks presented here emerges from many years of archival research, involving the rigorous physical review of hundreds of individual trade mark applications and bound volumes of colonial and Commonwealth Trade Mark Registers stored in the National Archives of Australia (‘NAA’) in Canberra and Sydney.

Australian decision-makers appear to have taken no steps to prevent the registration of stigmatising marks and have failed to utilise the prohibition on registering scandalous marks.[3] This article, however, will not engage with this absolute ground for refusal and the limited Anglo-Australian case law relating to this statutory provision.[4] Rather, the scholarly aim here is to paint a

more complete and accurate picture of the Register’s role in reflecting

and perpetuating Australian attitudes towards marginalised Others. This research is needed in part because exposing and acknowledging the stigma-tising history of the Register is an important step towards reconciliation with marginalised groups. What is more, understanding this history may well assist decision-makers in not repeating past wrongs.

A stronger regulatory response is warranted against stigmatising trade marks because they contain negative stereotypes and harmful associations that militate against the referenced group fully participating in the public sphere. Without this response, the referenced group faces a hostile public sphere, where they are afforded less dignity and respect than non-referenced groups. This creates significant communicative obstacles for referenced marginalised groups, who must first overcome the deleterious effects of stigmatising trade marks before engaging fully with the dominant (non-referenced group) on an equal platform. This article suggests the need for this robust regulatory approach — but without fleshing out its legislative form — notwithstanding legitimate concerns about the potential impact on freedom of expression.[5]

The article is organised as follows. Part II describes the publicity and other functions of Australian Trade Mark Registers and outlines the various roles trade marks perform according to trade mark theory, with a particular focus on the role of cultural and communicative interests in a trade mark system that is more commonly viewed as being concerned with economic regulation. After setting out a brief history on the colonial and Commonwealth trade mark registration systems, Part III then documents examples of stigmatising

trade marks — first racist and then gendered marks — on colonial and Commonwealth Trade Mark Registers. In doing so, these marks are situated in their broader socio-economic, legal and historical contexts. This involves a brief discussion of gendered norms and prevailing prejudicial attitudes, particularly towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and paranoia towards the idea of an ‘Asian invasion’ that gripped early colonial and post-Federation Australia. Part IV offers an insight into the real harm caused by discriminatory practices and representations of marginalised groups. These representations, then, should not be dismissed as merely unopposed products of their time or not harmful in context. The historical record in fact demonstrates that minority/stigmatised groups did object

to stigmatising representations, but that these pleas were largely ignored

by dominant societal interests. Finally, Part V concludes and identifies lessons that may be learnt by decision-makers in the Australian trade mark registration system.

Modern trade marks perform different roles and serve a range of often-competing interests. This article adopts the ‘authoritative model of trade signs’[6] emerging from the unanimous High Court decision of Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (‘Campomar’).[7] The Campomar model, as advocated by Patricia Loughlan, establishes the strong link between a trade mark’s different roles and interests: specifically, the badge of origin, personal property and cultural resource roles are ‘strongly related’ to the interests of consumers, traders and the public, respectively.[8]

In their first and most traditional role — also referred to as the ‘badge of origin’ function — trade marks operate as indicia of the trade origin of the marked goods or services. The interests of consumers qua consumers are primarily at stake here. When trade marks serve as accurate guarantees of trade source, they are said to minimise consumer confusion, as well as reduce search costs in future purchasing decisions, thereby facilitating efficient trade in goods and services.[9] Through their previous exposure to marked goods or services, consumers are able to more easily differentiate between competing products and services, which provides them with confidence that they

can again benefit from similar, if not identical, consumptive experiences in

repeat purchases.[10] Trade marks in this context are effective conduits for communicative interaction between their owners and consumers.

In their second role, trade marks are ‘personal property’, capable of accumulating value and turning that value to account in a range of ways. The High Court in Campomar speaks of Australian trade marks legislation creating a ‘statutory species of property protected by the action against infringement’ and transforming ‘this property to valuable account by licensing or assignment’.[11] Although this personal property role is broadly representative of traders’ interests, it is inextricably connected to the badge of origin role. This is because, as explained above, rational consumers that have enjoyed consumptive experiences with marked goods or services will seek out those same goods or services in future purchasing decisions. This creates a virtuous cycle: traders are incentivised (but not legally obligated) to create and maintain consistently high standards (or at least those tolerated by the market) as well as ensure (some) quality control in the delivery of their goods or services. In this way, Crennan J more recently explained that the ‘core function of a trade mark [is] distinguishing the registered owner’s goods from those of another, thereby attracting and maintaining goodwill’.[12]

Thus, an effective and robust system of trade mark registration and enforc-ement consequently permits these traders to ‘preserve their goodwill’.[13] To put it differently, through the course of this trade, a pecuniary value may be assigned to this goodwill so that they become ‘assets’.[14] Whether this property interest is properly characterised as a proxy for the trader’s goodwill or, as the trade marks per se, it is clear that trade marks become significant assets in their own right. For example, in the latest Interbrand ranking of the ‘Top 100’ global brands, Apple is once more ranked as the most valuable global brand and is estimated to have a brand value of USD214,480 million.[15]

These trader and consumer interests occupy positions of central imp-ortance in modern Australian trade mark law,[16] although they are often in conflict.[17] The High Court in Campomar recognised the fundamental friction[18] between these interests:

Australian legislation has manifested from time to time a varying accommodation of commercial and the consuming public’s interests. There is the interest of consumers in recognising a trade mark as a badge of origin of goods or services and in avoiding deception or confusion as to that origin. There is the interest of traders, both in protecting their goodwill through the creation of a statutory species of property protected by the action against infringement, and in turning this property to valuable account by licensing or assignment.[19]

But these commercial interests are not the only relevant interests in trade mark law. As the High Court in Campomar was careful to point out, the ‘exploitation of a trade mark registration ... may involve questions of public interest’.[20] Interests other than purely commercial or consumer interests should be factored into trade mark regulation and decision-making, because it is now clear (and accepted by the High Court) that trade marks are much more than pieces of personal property or mere signifiers of trade origin:

[T]rade marks may [also] play a significant role in ordinary public and commercial discourse, supplying vivid metaphors and compelling imagery disconnected from the traditional function of marks to indicate source or origin of goods.[21]

Although badge of origin and property roles are undeniably of great import-ance in trade mark law, focusing on this couplet of roles arguably leads to an underappreciation of an important third role and connected interest: namely, the cultural or broader communicative role of trade marks and the correl-ative public interest. Likewise, the ‘essential function’[22] doctrine developed by

the Court of Justice of the European Union fails to give adequate norm-

ative attention to a trade mark’s cultural role and, in any event, because

this is mainly an Australian article, its importance can be discounted for

present purposes.

Ascertaining the exact parameters and import of this cultural or societal resource role has proved challenging,[23] but trade marks here are conceived as ‘significant constructors of our social and visual realities, constitutive elements of consumer [and non-consumer] consciousness, icons of popular culture and blistering semiotic conductors’.[24] The cultural resource role is often described in a context which focuses on the need that individuals may have to reproduce or reference a trade mark in ways that interfere with the interests of trade mark owners. Thus, it has variously been described as involving ‘the interest of the public in free communication and competitive markets’[25] or, more broadly, as the ‘public interest in freedom of speech and expressive communication’.[26]

From the perspective of marginalised groups, however, concerns about equality, respect and freedom of speech[27] include not having the public sphere peppered with stigmatising trade marks. Such marks reinforce damaging stereotypical representations, thereby imposing communicative hurdles in democratic societies.[28] The general underappreciation of trade marks’ cultural role is one reason why the registrability of stigmatising trade marks is frequently uncontested. When we underestimate the cultural resource role of trade marks, we are more likely to fail to apply those parts of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) oriented towards protecting the public interest, such as the prohibition on registering ‘scandalous’ marks.[29]

Recognising, therefore, that all three distinct interests and roles often play antagonistic parts in delineating the scope of trade mark protection,[30] the normative question posed (although not settled) here is how trade mark law ought to regulate these competing interests in the context of stigmatising trade marks. As this article will show, stigmatising and other offensive trade marks can clearly act as trade source signifiers and as personal property,

but when thinking about these marks — such as the racist and demeaning trade marks introduced in the next section — their cultural resource role should be of greatest importance in the minds of those granting registered trade mark rights. In other words, of all the competing interests involved, from a public policy perspective, the public interest in the cultural role of trade marks (particularly the interests of the stigmatised group) is clearly most at stake in this space and should therefore be at its regulatory zenith.

To borrow the words of Wojciech Sadurski, the trade mark owner’s prop-

rietary interests ‘must yield to a higher value in the circumstances’.[31] This

higher value includes, for instance, a right to equal respect and basic human

dignity, including the speech rights of groups referenced in stigmatising trade

marks themselves not to be the subject of dehumanising and disparaging representations.

Most commentators focusing on the cultural role of trade marks empha-sise the need for third parties to have access to — that is, reuse — trade marks in the course of communication. Sadurski’s argument, for example, is that even though the law should recognise the (reputational) harms suffered by trade mark owners arising out of trade mark dilution (by ‘tarnishment’) caused by non-commercial actors, freedom of speech considerations should triumph over these considerations.[32] Similarly, many other commentators have argued that, notwithstanding the adverse effects on private property (trader interests), the promotion of ‘public cultural and communicative freedom’[33] requires permitting (especially non-commercial) actors free access to, or use of, trade marks. Emphasising the public interest considerations in favouring liberal access to trade signs in the public sphere, Patricia Loughlan argues that:

The very significance of trade signs in public communicative spheres and in the day-to-day consciousness of those who live and participate in the culture makes the capacity to access those signs and subject them to critical scrutiny so important to the maintenance and support of freedom of speech and to the marketplace of ideas in Australia and elsewhere.[34]

Similarly, Rosemary Coombe argues that the promotion of a more inclusive public sphere requires balancing the communicative ledger against stig-matising trade marks. Not only does this mean stronger legal interventions against such signs, but, as she suggests, this may also require generous access to registered stigmatising trade marks by contestatory counterpublic spheres seeking to challenge entrenched state-sanctioned stigmatising commercial signs and personal property.[35] Marginalised groups, Coombe maintains, should be permitted to

interpret, recode, or rework media signifiers to express their own identities and aspirations. ... [S]igns do not necessarily retain their original meanings when they circulate in social life. The very polysemy of signification — the surfeit of meaning that signifiers always potentially contain — provides the conditions of possibility for social agents to deploy texts, symbols, and images in unforeseen ways in the service of unanticipated agendas.[36]

However, the pursuit of this ‘communicative balancing’ should mean, at least in most cases (the exact contours of which would need to be worked out), that stigmatising trade marks do not secure registration in the first place and,

if registered, they should be struck from the Register in favour of the group(s) illegitimately implicated in the trade mark itself. This is because stigmat-

ising trade marks harm marginalised groups, and such harm includes impinging on a marginalised group’s democratic participation and capacity for effective speech. Decision-makers within the trade mark registration system, then, should adopt a prophylactic approach towards applied-for stigmatising trade marks.

Such an approach can be rationalised when squared against some of the general functions of the Register,[37] especially as they relate to regulating mar-ket behaviour.[38] These functions, which commentators warn should be treated as conceptually distinct from the rationales for trade mark protection per se,[39] generally focus on the Register’s communicative and related economic func-tions. Put another way, the key rationale for trade mark registration is the publicity that Registers offer to the world at large (but principally traders): they indicate to third parties the marks that have been registered and that are considered registrable. The main beneficiaries of this publicity are in pract-icality traders, who are then able to define the scope of their applied-for prop-erty rights against the information contained on the Register.[40]

If Registers seek to publicise trade marks,[41] this raises difficult questions: What justification is there for publicising stigmatising marks and what are the implications of a government entity offering such publicity for, and possibly granting registration to, such marks? It seems to me that there are good arguments for the state taking an active interest in the kinds of trade marks to which it grants such publicity and especially to which it grants registration. Moreover, there is a strong related argument here that the act of registration confers an actual or, at the very least, a perceived state imprimatur for stig-matising marks. More broadly, Christine Farley has pointed to the ‘symbolic effect of the government giving its stamp of approval’ to offensive marks and has argued that this ‘legal restriction [on trade mark registration] provides governments with an opportunity to refuse to lend the support of the administration to those marks that offend the public’.[42] In light of this broader context, do we really want a Register of Trade Marks strewn with registered stigmatising trade marks?

Registered stigmatising trade marks, generally reflective of denigratory attitudes towards non-Whites and women, helped to reaffirm — and perhaps even shape — destructive stereotypes in the Australian public sphere, especially as they related to Indigenous Australians. Their legal protection as property arguably further abetted their proliferation in transatlantic and transpacific public spheres. Before reproducing some of these stigmatising trade marks, it is worthwhile providing some contextual background regarding the colonial, state and Commonwealth Trade Mark Registers.

The proposal of a system of trade mark registration in the Australian colonies did not appear to generate the same degree of angst as it did in the United Kingdom (‘UK’) in the 1860s.[43] In fact, four Australian colonies — South Australia,[44] Queensland,[45] Tasmania[46] and New South Wales[47] — adopted a basic trade mark registration system some 10 years before the first trade mark registration legislation in the UK.[48] (New Zealand had similarly set up a trade mark registration system well before its colonial masters.[49]) Victoria, which

at first more or less implemented the Merchandise Marks Act 1862,

25 & 26 Vict, c 88,[50] later followed suit,[51] with Western Australia being the last Australian colony to establish a system of trade mark registration.[52]

While astute colonial and international traders quickly registered their marks to take advantage of the benefits of registration, smaller local traders either had little or no knowledge of the functioning Register or perhaps were less convinced of its advantages, preferring instead to rely on existing common law protections. The New South Wales Trade Marks Register documents 10,936 trade mark applications from its commencement up to

30 August 1906,[53] but the first volume reveals only 308 applications for the period 4 August 1865 – 14 June 1879.[54] In Victoria, after the passage of Trade Marks Registration Act 1876 (Vic) (40 Vict, No 539), the Victorian Trade Marks Register reveals 46 applications in 1876.[55] This number more

than doubled in the following year (116), with applications peaking in

1899 (497).[56] But some colonial traders may have considered other colonial markets less viable, and were thus slower to pursue registration there. Consequently, those colonies witnessed far fewer applications for registration. For instance, the Tasmanian Registrar in the first six years of operation accepted one application in 1869, then another in 1872, and one in 1874.[57] In Western Australia, there were only two trade mark applications in 1885, then 28 in 1886, before peaking at 300 applications in 1897.[58]

Even though the data is incomplete, almost all colonies demonstrate a pronounced upward trend in applications for trade mark registrations.[59] For the period 1897–1901, there were 9,470 trade mark applications across all of the Australian colonies,[60] broken down as follows: Victoria received the most applications for registration (2,323), followed by New South Wales (2,109), South Australia (1,290), Queensland (1,477), Western Australia (1,345) and, finally, Tasmania (926).[61] This evidence supports the proposition that early ‘colonial laws were quite extensively used by local traders’.[62] However, a check of the historical colonial Trade Mark Registers also confirms that inter-national traders, especially from the UK and the United States (‘US’), regularly sought the benefits of colonial trade mark protection. This often meant that stigmatised groups from other countries, such as Native Americans, Africans, Maoris, Indians and other marginalised groups, entered colonial Registers. Some international traders, such as William Lever of multinational Lever Bros, vigorously enforced their colonial and Comm-onwealth trade mark rights, and appeared regularly before the courts.[63]

The first federal trade mark legislation was the Trade Marks Act 1905 (Cth).[64] This Act was largely modelled on existing UK legislation,[65] but included some important transitional provisions concerning state trade mark registrations,[66] designed to encourage the migration of trade marks onto the Commonwealth Register.[67]

Traders flocked to the Commonwealth Register, with the first month of operation witnessing almost 1,500 applications.[68] Many of these registrations were stigmatising trade marks, notwithstanding the prohibition on registering trade marks that were ‘contrary to law or morality’ or comprising ‘scandalous designs’.[69] Like their colonial counterparts, federal trade mark examiners, oblivious to the damaging effects of these commercial symbols, facilitated their registration. In an environment where parliamentarians had not prov-ided meaningful guidance on the prohibition on registering scandalous and other improper marks, these issues are unsurprising. Not that this would have necessarily mattered, because, as we shall see, many parliamentarians shared racist and sexist views: strong public spheres were not yet sensitised to race and gender concerns. These factors, then, meant that amorphous standards tilted towards protecting dominant societal interests at the expense of marginalised Others, despite the protests of such groups.

The following sections set out several racist and sexist stigmatising trade marks from the colonial and Commonwealth Trade Mark Registers. These trade marks demonstrate how, often in connection with government policy, stigmatising trade marks contributed to, inter alia, institutionalised racism and sexism in Australia. As foreshadowed in the introduction and in the interests of convenience, this article deals seriatim with three stigmati-

sed groups: Indigenous Australians, Chinese and other non-White peoples,

and women. In setting out the historical contexts concerning these stig-

matised groups, a thematic approach is generally preferred to a chrono-

logical approach.

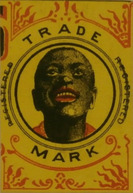

In colonial Victoria or under Commonwealth legislation, racist trade marks such as the NEGRO’S NECK & HEAD device mark for leather goods

(Figure 1) sailed through to registration.[70] This registration, and the GOLD DUST device mark of so-called ‘twin niggerboys’ spruiking soap products[71] (Figure 2) demonstrates that racist representations faced no obstacles in registration. Likewise, the New South Wales Register reveals objectionable word marks such as NIGGERGAL[72] for tobacco and NIGGERSHINE[73] for stove polishes also secured registration.

Figure 1: NEGRO’S NECK & HEAD Trade Mark (1896)[74]

Figure 2: NK Fairbank’s (In)Famous GOLD DUST Trade Mark (1897)[75]

In his famous book Symbols of America, Hal Morgan describes NK Fairbank’s GOLD DUST trade mark as ‘among the best known commercial symbols in America’.[76] According to Morgan, a Fairbank company executive was so be-mused by a Punch cartoon depicting two Black children washing each other in a tub under the caption ‘warranted to wash clean and not fade’ that he commissioned an artist to draw this as a device mark for the company’s washing powder.[77] Through colonial agents, this US registered device mark later secured registration in New South Wales[78] and Victoria.[79] The trade mark bureaucrat charged with registering this mark appears to have ticked off each of the following indexing words: ‘children’, ‘negro’, and ‘niggers’.[80] Such was the popularity of this transpacific stigmatising trade mark that it then migrated onto the Commonwealth Register as Trade Mark No 11609 where

it remained for many years.[81] The device mark had earlier secured trade

mark registration in the transatlantic public sphere as British Trade Mark

No 206705.[82]

In addition to the misappropriation of African and Asian imagery, Australian traders and manufacturers, unlike their British counterparts, also had local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations to exploit in their commercial insignia. Australian traders and manufacturers (particularly soap, paint, tobacco and alcohol proprietors) repeatedly seized on Indigenous and Black imagery to promote their wares, and strongly defended such marks when their pecuniary interests were threatened.[83] The prohibition against scandalous and immoral marks was never invoked to prevent registration of stigmatising marks which, amongst other things, suggests that decision-makers and/or traders did not see such representations as racist/sexist, or that they did not see racism/sexism as a problem. In this connection, the (often international) stigmatising trade mark registrations lend support to Rosemary Coombe’s broad claim that intellectual property laws ‘play an important role in the way histories of imperialism and colonialism, territorial annexation, and political disenfranchisement are socially inscribed across national land-scapes’.[84] The political disenfranchisement for Indigenous Australians and women, reinforced through trade mark law, was particularly stark. Effectively discharging their main badge of origin function, and thereby serving comm-ercial interests, damaging representations of women, Indigenous Australians, Blacks and ethnic minorities in colonial and Commonwealth Trade Mark Registers were both prolific and seemingly commonplace.

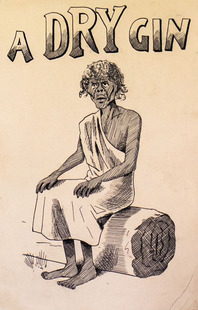

Figure 3: A DRY GIN Trade Mark (1897)[85]

Consider, for example, the racist stereotypes embodied in the applied-for trade mark, shown above in Figure 3, which is extracted from the colonial New South Wales Trade Marks Register.[86] In the column headed ‘Description of Trade Mark’ of the pasted Gazettal Notice, dated 10 November 1897, the trade mark is described as ‘[t]he figure of a wisened dried up aboriginal [sic] woman, sitting on a log, with a blanket draped over her body, and having her hands placed on her knees, with the words “A Dry Gin” over her head’.[87] The mark references the miserable yearly blanket distributed to Aboriginal Australians.[88] Furthermore, the word ‘gin’ here has a double entendre well understood by colonial consumers: it obviously refers to the trader’s alcoholic products, but it also encapsulates the racist and derogatory reference to an Aboriginal woman.[89] The trader’s branding strategy exploits this double meaning by emphasising the ‘dryness’ of its alcoholic product and trade symbol. The enlargement of the word ‘dry’ together with the dehumanising representation of an Aboriginal woman achieves this purpose, as well as rein-forcing the trade mark’s badge of origin in the colonial public sphere.

Demonstrating similar callous indifference to that of American traders towards Native Americans through the application of the CRAZY HORSE trade mark in respect of malt liquor,[90] we see that Australian traders clearly considered Aboriginal imagery (insofar as it applied to alcohol products) valuable;[91] so much so that they often battled over the right to its control.[92] The A DRY GIN mark appears to make light of the devastation that alcohol wrought on Aboriginal peoples, considered by many Aboriginal activists as one of the ‘enemies’ of the Aboriginal people.[93]

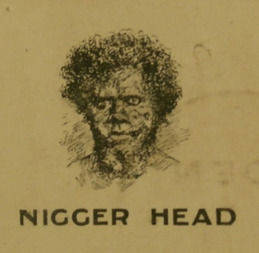

Figure 4: NIGGER HEAD Trade Mark (1920)[94]

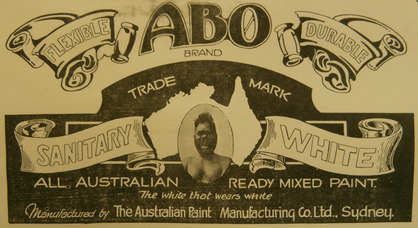

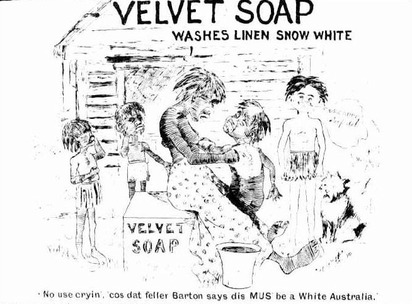

Other stigmatising trade marks adorned consumer goods, such as NIGGER HEAD inks[95] (Figure 4) and ABO BRAND paints[96] (Figure 5 and Figure 6) and featured in advertisements (such as the Velvet Soap advertisement[97] in Figure 7). These representations had lasting consequences.

Figure 5: ABO BRAND Paints (1921)[98]

Figure 6: ABO BRAND Paints (1926)[99]

One firm in particular, J Kitchen & Sons, the proprietors of several well-known trade marks such as VELVET soap,[100] cultivated and promoted many negative stereotypes of Indigenous Australians for many decades. As shown in Figure 7 and Figure 25, their soap products, trade marks and advertisements speak to the efficacy in ‘cleansing’ Aboriginal skin colour. In various advertisements some 20 years earlier from the trade mark depicting a half ‘cleansed’ Indigenous man (Figure 25), J Kitchen & Sons coupled that

theme — the juxtaposition of dirt–cleanliness and Blackness–Whiteness — with Australia’s first Prime Minister Edmund Barton’s ‘White Australia’ policy. The image (Figure 7) depicts a ‘half-cleansed’ Aboriginal boy, who is being forcibly washed by an Aboriginal woman, whilst being told that his cry-

ing is pointless because all must conform to Barton’s ‘White Australia’.[101]

While other children anxiously await their turn to be assimilated, a decol-ourised/bleached Aboriginal child, seen smiling having benefited from his new found ‘whiteness’, exclaims ‘budgaree [sic] [ie fine] soap dat’.[102]

Figure 7: ‘Velvet Soap’ Advertisement (1901)[103]

The presumed civilising mission that soap performs here has been taken up elsewhere,[104] but is well-demonstrated also in Australia via the ‘Velvet Soap’ advertisement (Figure 7), with many other trade marks considered in this article demonstrating this point. Writing in relation to ‘African cleansing’ and imperialism, Anne McClintock argues that ‘[p]urification rituals ... can also be regimes of violence and constraint’:

People who have the power to invalidate the boundary rituals of another people thereby demonstrate their capacity to violently impose their culture on others. Colonial travel writers, traders, missionaries and bureaucrats carped constantly at the supposed absence in African culture of ‘proper domestic life’, in particular Africans’ purported lack of hygiene. But the inscription of Africans as dirty and undomesticated, far from being an accurate depiction of African cultures, served to legitimize the imperialists’ violent enforcement of their cultural and economic values, with the intent of purifying and thereby subjugating the unclean African body and imposing market and cultural values more useful to the mercantile and imperial economy.[105]

Transposing the word ‘African(s)’[106] above with ‘Aborigines’,[107] Maoris,[108] Native Americans,[109] or ‘coloured’ Others, we see that local and international registered trade marks on the colonial and Commonwealth Registers provide some support for Anne McClintock’s ideas. These trade marks and accompanying advertisements — supported by an insensitive Trade Marks Office promoting pecuniary interests and a narrow construction of the public interest — helped to denigrate Others and encourage the imposition of ‘cultural and economic values’ more useful to developing Imperial economies.[110] For instance, the ‘cleansed’ Aboriginal boy in Figure 7, though retaining some of his Aboriginality through his spoken words and dress, has accepted his subjugated fate: he is now assimilated.

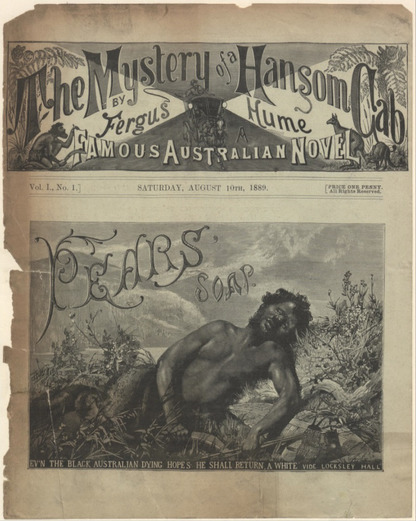

Figure 8: Pears’ Soap Locksley Hall Advertisment (1899)[111]

Sometimes, stigmatising commercial imagery referred to popular culture circulating in the public sphere, where Indigenous peoples aspire to ‘whiteness’. For example, in Figure 8, a line from one of Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poems is quoted to promote soap products: ‘Ev’n the black Australian dying hopes he shall return, a white.’[112]

Stigmatising trade marks and their accompanying advertisements did not end there. Like many colonial cartoons,[113] some registered trade marks oper-ating in the colonial public sphere appeared to have genocidal references. For instance, in the New South Wales Trade Marks Register, the STREET’S WHITE ANT CURE registered device mark, Trade Mark No 7185, speaks of applying ‘chemical preparations for destroying noxious animals and insects’ (Figure 9).[114] The inescapable inference from this device mark is that Indig-enous Australians are considered noxious pests requiring extermination.[115]

Figure 9: STREET’S WHITE ANT CURE Trade Mark (1899)[116]

Furthermore, the supposed link between Indigenous Australians and other animals, such as primates, was arguably well entrenched in some parts of Australian culture. The view that Aborigines were ‘sub-human primates’ also ‘deserving’ of extermination certainly existed in the minds of many colonial Australians. According to media reports, one of the jurors in the infamous first Myall Creek massacre trial and subsequent acquittal said:

I look on the blacks ... as a set of monkies, and the earlier they are extermin-ated from the face of the earth the better. ... I knew well they were guilty of the murder, but I ... would never see a white man suffer for shooting a black.[117]

Following the second Myall Creek massacre trial, which resulted in seven convictions and hangings, colonial newspapers preserved these repulsive views. The Sydney Herald editorial lamented the time and expense associated with the trials, rather than the beheadings and immolation of innocent Aboriginal women and children: ‘The whole gang of black animals are not worth the money which the Colonists will have to pay for printing the silly documents on which we have already wasted too much time.’[118]

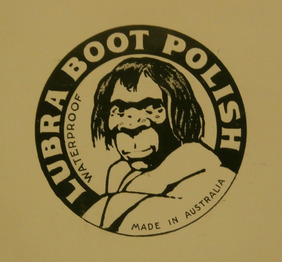

Figure 10: LUBRA BOOT POLISH Trade Mark (1906)[119]

As Figure 10 attests, stigmatising trade marks incorporating the theme of the ‘Aboriginal as monkey’ were evident in early 20th century Australia. The colonial Victorian Trade Marks Register reveals that, on 23 March 1906, Henry Borrodell Fisher and Frederick William Inch Menhemmett of Fitzroy applied to register this trade mark, Trade Mark No 9573, LUBRA BOOT POLISH in respect of Class 50 (pastes and polishes of all description).[120] The essential particulars were described as the ‘word “Lubra” and device of a lubra’.[121] A handwritten note by the Commissioner of Trade Marks,

GH Neighbour, suggests that the trade mark application was gazetted on

26 March 1906 and, being unopposed, secured registration.[122]

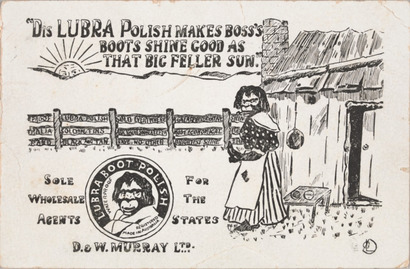

Figure 11: ‘Lubra Boot Polish’ Advertising Post Card (1906)[123]

In the spruiking of LUBRA BOOT POLISH, the traders, in the commercial post card in Figure 11,[124] are plainly representing the ‘Lubra’ housemaid as subhuman and most likely operating in slave-like conditions.[125] The subordinated role of this supposed primate, replete with her contrived stupidity and ‘racialised subject position’,[126] is clear for everyone to see; the caption in Figure 11 reads: ‘Dis LUBRA Polish makes boss’s boots shine good as that big feller sun.’

Figure 12: LEWIS & WHITTY’S BLACKING Trade Mark (1883)[127]

These affronts did not only target Indigenous Australians. Traders also

used Maoris and Africans alongside various animals such as monkeys

(Figure 12)[128] and lizards[129] to differentiate their blacking products and boot polishes from those of their competitors.

Moreover, deleterious racist attitudes in Australia were not limited to Indigenous Australians. Such attitudes and policies also extended to other non-White Australians, particularly Chinese immigrants. Violence against Chinese immigrants was common in early Australian colonial history, particularly on the goldfields.[130] Colonial laws sought to restrict Chinese immigration[131] and unfairly targeted Chinese gold diggers.[132] ‘Australian egalitarianism’, writes Kercher, ‘was based on an equality of white men alone’, which meant that Asians (like Indigenous Australians) ‘were left out of the embrace of mateship’.[133] As is well known, one of the first accomplishments of the new Commonwealth Parliament was the passage of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (Cth). This was the first federal Act in a series of immigration laws that collectively came to be known as the White Australia policy, which sought to ensure Australia’s population was ‘white’. Kercher observes that these laws were more of an Australian innovation, with Britain merely suggesting a ‘feeble disguise for discriminatory legislation’.[134]

During parliamentary debates over the Immigration Restriction Bill

1901 (Cth), James Ronald warned of the inevitable ‘degeneration’ to humanity when ‘inferior races ... blend with a superior race’[135] and thus pleaded: ‘Let us keep before us the noble idea of a white Australia — a snow-white Australia if you will. Let it be pure and spotless.’[136] The then Attorney-General, Alfred Deakin, argued that the ‘policy of securing a “white Australia”’ meant prohibiting ‘all alien coloured immigration’ and deporting or reducing the ‘number of aliens now in our midst’.[137] In his earlier life as a parliamentarian before his appointment to the High Court of Australia, Sir Isaac Isaacs expressed his commitment to this policy by declaring that:

Those around us — our constituents of to-day, and our fellow countrymen — and those who come after us, will doubtless scrutinize our acts and our words to see if we have faithfully carried out with unswerving fidelity the principles upon which we have been sent here. Consequently, I am prepared to do all that is necessary to insure that Australia shall be white, and that we shall be free for all time from the contamination and the degrading influence of inferior races.[138]

Commonly held xenophobic views were also evident in debates concerning the Customs Bill 1901 (Cth), where the then Minister for Trade and Customs, Charles Kingston, observed that ‘[w]e know that for “ways that are dark and tricks that are vain the heathen Chinee [sic] is peculiar”; but we propose

to keep him out of a white Australia’.[139] In advocating the incorporation

of Union (White) Labour marks into the Trade Marks Bill 1904 (Cth),

Isaac Isaacs again expressed his strong ‘desire to have a White Australia’,

and warned of the American cigar manufacturing experience where ‘Chinese operatives’ were employed together with ‘coolies’ operating in ‘small rat tenements’.[140]

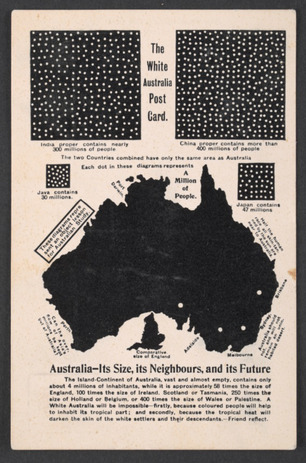

These racist views and notably anti-Chinese policies, though present in colonial times, arguably hardened when anxieties over the Other increased. Cartoonists produced racist caricatures of the ‘filth’ associated with the ‘yellow peril’ and the supposed threat to White Australia.[141] These paranoid trepidations circulated widely in the Australian public sphere, sometimes as post cards such as that depicted in Figure 13.

Figure 13: ‘The White Australia Post Card’ (1910)[142]

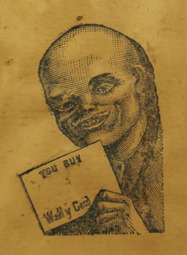

Many traders, whether deliberately or subconsciously, exploited marginalised Others as a way to differentiate their goods, and thus readily reflected racist sentiments in marked goods, such as Trade Mark No 2188, the WELLY GOOD CHINAMAN device mark (Figure 14).[143] This trade mark was created to ensure its versatility: the blank space on the placard in between ‘You Buy’ and ‘Welly Good’ allowed ‘for the reception of the name of the article in respect of which the trade-mark is used’.[144] Racist caricatures of Chinese Australians suggest that ‘welly good’ was commonly used to mock Chinese people.[145] However, the WELLY GOOD CHINAMAN mark did not appear to enjoy commercial success; it soon became ‘defunct’ and was then removed from the Register.[146]

|

Figure 14: WELLY GOOD CHINAMAN Trade Mark

(1889)[147]

|

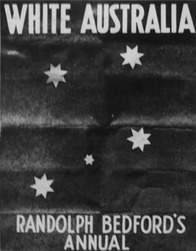

Figure 15: Bedford’s WHITE AUSTRALIA Trade Mark

(1925)[148]

|

Some trade mark applicants, like journalist, politician and novelist Randolph Bedford, sought to profit off the White Australia policy by securing registration of a WHITE AUSTRALIA device mark for their goods

(Figure 15). Other traders simply conflated the perceived stigmatised charact-eristics of non-Whites, such as in the NATTAMATTA BLACK BOY device mark shown in Figure 16. For these traders, maltreatment of Others as an amorphous blob of (sub)humanity was presumably uncontroversial.

Figure 16: NATTAMATTA BLACK BOY Trade Mark (1892)[149]

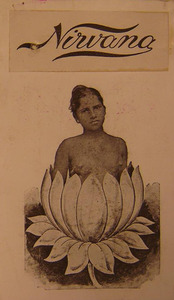

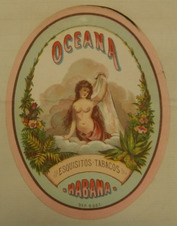

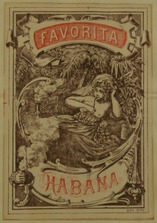

Women and girls, it appears, did not fare much better. It seems that decision-makers did not consider their continuous objectification particularly problematic. Consistent with the historical record in the UK, the colonial and Commonwealth Trade Mark Registers reveal that Black women, as well as representations of other ‘exotic’ women, in particular, were hypersexualised. Stigmatising trade marks of Black women and girls went beyond cartoonist caricatures of buxom mythical female beings (Figure 17 and Figure 18) and in fact often included sexually suggestive photographs of actual bare breasted Black women, as shown in the NIRVANA trade mark (Figure 19).[150]

Figure 19: NIRVANA Trade Mark (1896)[153]

The NIRVANA trade mark (Figure 19) is troubling both because of its sexism and irreverence to those of the Hindu faith. Yet, this stigmatising mark proved to be a particularly effective trade symbol. Described as a ‘Hindoo [sic] goddess emerging from a lotus flower together with the word “Nirvana”’, Holmes Samuel Chipman, of Margaret Street, Sydney, applied to register this trade mark on 28 December 1896 in Class 42 (long list of foodstuffs).[154] Chipman sought, and was granted, British trade mark registration for the mark in 1898.[155] The value of the NIRVANA trade mark as a species of property recognised and protected by law was self-evident. It was transferred to Kandena Tea Estates (Transfer No 9343) and then again to John Connell & Co Pty Ltd (Transfer No 10061).[156] The mark later migrated onto the Commonwealth Trade Marks Register as Trade Mark No 26212, where it was again renewed on 10 October 1933 for another 14 years.[157] Although the mark, as it appeared there, was slightly more stylised and set within a more elaborate frame, the essential particular of the bare-breasted Hindu woman remained. Due to non-renewal, it was finally removed from the Common-wealth Register on 27 October 1947.[158]

For over 50 years, this trade mark adorned various foodstuffs[159] and arguably occupied a continuous visual presence in Australian households and grocers. All the while, as with other examples,[160] the unrelenting stereotype of Aboriginal[161] or other minority women available for the sexual gratification of male consumers was repeated and propagated in the Australian public sphere. Perhaps these trade marks contribute to what Jan Pettman, writing more broadly, conceptualises as structured power relations that put colonised women in colonial and/or racist societies in a ‘terribly vulnerable’ position.[162]

In recognising the historical and continued vulnerability of Aboriginal women and girls to sexual exploitation and abuse, she argues that:

Racist and sexist representations of Aboriginal women have tended to label them as immoral and highly sexed, as prostitutes. These representations are compounded by the devaluing of women and the tendency to blame the victim, which is part of rape politics in Australia generally. Here again racism and sexism reinforce each other, and are experienced by Aboriginal women in a brutal interaction.[163]

Those representations are reflected in some of the trade marks considered in this article. Sexism, however, was not confined to Aboriginal or Black women and girls. Stigmatising representations of Latino women (Figure 20), object-ified White women (Figure 21 and Figure 22) or the subordination of sub-servient women in the domestic sphere (Figure 23) were all too common.

Figure 20: OCEANA and FAVORITA Trade Marks (1881)[164]

|

|

Figure 23: BALM OF EASE Trade Mark (1920)[167]

Although it is not the present intention to provide a deep account of gender discrimination in historical and modern day Australia,[168] a few points warrant discussion. Feminist activism is often divided into ‘three waves’. The first wave is concerned with enfranchising women; the second wave generally relates

to equality of opportunity, reproductive and other rights; and, depending on the audience, the amorphous third wave either speaks to women securing an equal share in decision-making power[169] or refers to a critique of the pre-sumptive success of the second wave and deconstructing the concept of universal womanhood through post-colonial lenses, as well emphasising individual autonomy.[170]

Focusing here only on the first wave, Australian women — with the notable exception of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women — were the first in the world to secure the right to vote in federal elections and be elected to federal parliament.[171] Australian feminist counterpublic spheres emerged across Australia, with at least one active suffragette movement in every colony from the 1880s.[172] Classic feminist publications, such as The Dawn: A Journal for Australian Women, described as the ‘pioneer paper of its kind in

Australia ... edited, printed, and published by women, in the interest of women’,[173] played a significant role in promoting women’s rights. Operating within the dominant hegemony, replete with the reality of ‘prescribed sex roles’, many first wave feminists maintained that supposedly ‘female “traits”’ of ‘morality’ and ‘purity’ would enter the public sphere if women were granted the vote, because the ‘righteousness and unselfishness that inspired domestic life’ would inform the political sphere.[174]

Yet, as was the case in other jurisdictions,[175] when Australian women agit-ated for fundamental civil rights, entrenched interests ridiculed the suffra-gette movement in the Australian press. Anti-feminist caricatures were a part-icularly effective method of stigmatising suffragettes. A popular theme was that enfranchising women would result in a neglect of familial duties.[176] In another theme, the domesticated young and curvaceous mother was supp-osedly more appealing than the short and aging, beak-nosed, shabbily dressed suffragette clutching a scroll titled ‘Womans [sic] Suffrage’.[177]

Despite important developments like the enfranchisement of White women, notions of White women as ‘maternal citizens’ and the ‘civic duty’ of motherhood remained strong.[178] In other words, whether franchised or dis-enfranchised, White women in Australia were expected to operate mainly in the domestic sphere and produce White children for the nation. Although conservative principles ‘protecting’ the domestic roles of wives and mothers predominated here,[179] many first wave feminists across the political continuum also openly employed eugenicist ambitions — especially bettering the ‘quality’ of the White Australian race — as a springboard for furthering women’s rights.[180]

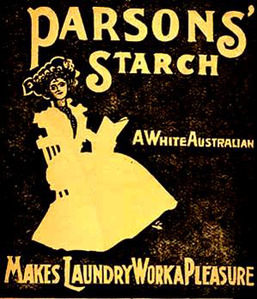

Figure 24: PARSON’S STARCH Advertisment (1903)[181]

Anxieties surrounding this ‘national duty of [White] motherhood’,[182] evident from the 1880s, intensified after World War I with fears of an ‘Asian invasion’, and remained up to the 1970s.[183] Not only were these anxieties reflected in cartoons of that era,[184] but registered trade marks and accompanying advert-isements employed by Australian traders, such as Parsons Brothers & Co[185] (Figure 24) had long underpinned the importance of White women to that end, while at the same time reinforcing gendered stereotypes. Those kinds of representations support Joan Eveline’s broader contention that the ‘Australian politics of motherhood’ has, for most of the 20th century, ‘limited women’s participation in the public sphere’.[186] It also supports her argument that the ‘notion of the maternal citizen ... produced racial difference amongst Australian women: White women, construed as “mothers of the race”, were admonished to “breed up” the supply of White Australian[s]’,[187] whereas the opposite was true for Indigenous women.

Thus, further complicating our historical context is the intersectionality of race, gender and class, as these factors inevitably give rise to multiple sites of oppression. Many third wave feminist writers have emphasised that the historical and continued subordination of non-Western women was not simply due to their gender. For instance, Jackie Huggins observes that Aboriginal women were discriminated against and continue to experience discrimination more on account of their race than their gender, and that this problem remains unresolved within the Australian feminist movement.[188] Caricatures mocking aspirational Aboriginal women seeking education and transitioning from domestic servility were commonplace.[189] Moreover, the historical relationship between Black and White women suggests that ‘sisterhood’ could not ‘transcend such racial boundaries’, and that ‘white women’s activities ... [were in fact] part of the colonisation and oppression of Black women’.[190] White women, in particular, oppressed their Indigenous counterparts through domestic servility.[191]

Other scholars adopting a post-colonial framework have argued that the juxtaposition of ‘white “civilised” and black “primitive” womanhood were integral to the formulation’ of the Australian feminist project in the first half of the 20th century, a period when ‘nation-builders were self-consciously constructing a White Australia’.[192] There was even a degree of complicity by White Australian women who adopted ‘whiteness’ as a ‘crucial marker of boundaries and status’ to advance their cause, thereby differentiating ‘themselves from other (coloured) colonised peoples’.[193] Aboriginal scholar Joan Eveline maintains that Australian female suffrage was a ‘triumph of

racism over sexism and a signal for the further demolition of Aboriginal

women’s rights’.[194]

While gender discrimination remains a problem in Australia,[195] immigrant women and Indigenous women suffer the ‘double structural load’ of sexism and racism.[196] As Marie de Lepervanche puts it:

Women, and particularly immigrant women, remain socially and occup-ationally disadvantaged; sexual harassment of women is not uncommon, and married women who work are still considered unnatural in certain quarters ... in conservative thought their place is clearly with the family at home.[197]

These unfortunate attitudes predominate today, even in professional fields.[198] Sexist and misogynistic representations and attitudes abound in commercial advertising[199] and accompanying trade mark registrations,[200] warranting further sensitivity by trade mark examiners towards such marks.

For some, it would be tempting to dismiss these stigmatising representations as historical artefacts and not much more. To take that approach, however, would be problematic for several reasons. First, it ignores the harms caused by racism (including racist trade marks and advertising) — harms that are both real and enduring. Second, contending with and acknowledging this

history — especially the collective dismissal of those voices that rallied against such (mis)representation — is a condition precedent to true reconciliation, especially when one concedes, for example, that the deeply engrained bigoted tropes animating these unwelcomed ghosts can, and often do, come

back to haunt us in contemporary Australia. This latter point is illustrated

by considering two recent manifestations of racist abuse where deep-

rooted racist tropes were deployed against Indigenous Australian athletes

Adam Goodes and Eddie Betts. Finally, disregarding the true history of

the Register would be to disregard the cautionary tale it presents to con-temporary decision-makers, especially insofar as this might affect minority groups generally.

Racist representations — such as the long-standing trade mark, depicted in Figure 25, employing the metaphor of Black skin in need of cleansing through soap products — are hurtful to referenced groups. Racism, however so suffered, has detrimental consequences for the targeted group, especially in relation to their mental health. We know, for example, that ‘racist experiences have an ongoing deleterious effect on people’s lives and wellbeing even after direct exposure has ended’.[201] Numerous studies[202] and official government statistics[203] have documented these harmful connections in relation to Indigenous Australians. Another study has established, for example, that over half of Indigenous Australians who experience racial discrimination report feelings of psychological distress, which is a recognised risk factor for anxiety and depression, and that greater exposure to racism significantly increases levels of psychological distress.[204]

Figure 25: Kitchen & Sons’ Trade Mark (1920)[205]

In this connection, what, then, are the implications of racist trade marks that are spread throughout the public sphere? In addition to the psychological distress suffered by referenced individuals and communities, stigmatising trade marks can create and reinforce pernicious stereotypes, which not only harm referenced individuals and communities, but affect broader society by deeply engraining prejudice against targeted groups. Moreover, as very successful trade marks are often ubiquitous, their destructive effects may linger long after their circulation. The trade mark registration system may well have played a role in engraining these prejudices. It must not be forgotten that registered trade marks are not meant to be confined to a sedentary existence on the Register: the registered trade mark system is mainly about fostering investment in and the use of registered trade marks.[206] Registered stigmatising trade marks are no different. In fact, the historical records demonstrate that stigmatising trade marks and commercial imagery were used widely on consumer goods and, what is more, such registered trade marks and associated commercial imagery were considered valuable. Indeed, there are many examples of trader disputes over rights to use contested stigmatising trade marks.[207]

In stark contrast to the historical public sphere, a broader spectrum of interest groups in the contemporary Australian public sphere have made concerted efforts in tackling the scourge of racial discrimination and its destructive effects on its victims. The Australian Human Rights Commission’s ‘Racism. It Stops With Me’ campaign has sought to do this, as well as empowering Australians to prevent and respond effectively to racism.[208] Moreover, ‘The Invisible Discriminator’ advertising campaign by Beyond Blue,[209] with its tagline ‘Stop. Think. Respect.’, drew attention to the damaging impact on the mental health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples caused by racial discrimination.[210] We learn that racial discrimination (including pernicious stereotypes), for instance, restricts the targeted group’s participation in public life, as these groups withdraw from various aspects of ‘community life’ as a coping mechanism.[211] In other words, exposure to racism leads to social exclusion and shrinks the public sphere for the targeted group. This evidence speaks to a broader argument; specifically, that registered stigmatising trade marks contribute to the inequality faced by marginalised groups in the broader public sphere and provide support

for the argument that greater use should be made of the embargo against

their registration.

As has been well covered elsewhere,[212] Australia’s treatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples has been, and continues to be, abhorrent. At various points in Australia’s history, Indigenous peoples have been colonised, subject to frontier violence and massacres, forcibly removed from country and family, subject to ‘protectionist’ policies, poisoned, raped, abducted, murdered, vanquished, exploited as unpaid and underpaid labourers, and generally treated as subhuman. Mythologised as a ‘dying race’, Indigenous Australians suffered ongoing oppression and discriminatory policies, such as the widespread forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families into reservations, missions or state care, which, in 2008, drew a parliamentary National Apology from the then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.[213] Indigenous Australians were only counted in ‘reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth’[214] following the 1967 Referendum.

However, and contrary to the widely held misperception of ‘historical Aboriginal silence’, these outrages did not go unchallenged by Indigenous Australians,[215] British parliamentary committees,[216] and various humanitarian and feminist organisations.[217] In the 1920s and 1930s, Aboriginal counter-public spheres, such as the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association, Australian Aborigines’ League, Australian Aboriginal Association, Native Union and the Aborigines Progressive Association (‘APA’), were formed to promote Indigenous causes and pursue civil rights that, until then, had been denied.[218] The APA, for example, campaigned for equal citizen rights and drew attention to the conditions of Aboriginal slavery and the poor treatment by the much-despised New South Wales Aboriginal Protection Board, as well as equivalent legislation in other state and territory jurisdictions.[219] John Thomas (Jack) Patten, President of the APA, was also the General Editor of The Australian Abo Call: The Voice of the Aborigines,[220] possibly the first ‘advancement movement’[221] newspaper with an Aboriginal target audience. Claiming to represent 80,000 Australian Aborigines, its masthead read: ‘We ask for Education, Opportunity, and Full Citizen Rights’.[222]

In its first edition, Patten’s address at the National Day of Mourning on

26 January 1938, being the sesquicentenary of White settlement, was reported,[223] together with a ‘Ten Point Plan’ outlining the APA’s objectives. This was personally delivered to the then Prime Minister Joseph Lyons.[224] In direct response to letters published by The Sydney Morning Herald[225] denying ‘Aboriginal were massacred in the early days’, later publications sought to document the ‘massacres [that] occurred in almost every district of Australia’ and to show that ‘blacks were shot down and poisoned like dingoes’.[226] Similarly, William Ferguson, one of the founders of the APA,[227] expressed indignation at the Parliamentary Select Committee’s ‘slanders against our people, especially our women’, and called for ‘ordinary citizen rights, not any special rights’ as well as a ‘right to own land that our fathers and mothers owned from time immemorial’.[228]

Many of the themes discussed in this publication expanded on an earlier pamphlet, entitled ‘Aborigines Claim Citizen Rights!’,[229] which was distributed in the lead up to the National Day of Mourning. This ‘first political manifesto of Aborigines’,[230] co-authored by Patten and Ferguson, pressed the case for ‘Old Australians’, rallied against racial prejudice and insisted on a ‘New Deal’ for Indigenous Australians:

Your present official attitude is one of prejudice and misunderstanding. ... We ask you to be proud of the Australian Aborigines, and not to be misled any longer by the superstition that we are a naturally backward and low race. This is a scientific lie, which has helped to push our people down and down into

the mire.

At worst, we are no more dirty, lazy stupid, criminal, or immoral than yourselves. Also, your slanders against our race are a moral lie, told to throw all the blame for our troubles on to us. You, who originally conquered us by guns against our spears, now rely on superiority of numbers to support your false claims of moral and intellectual superiority.[231]

In light of contextual oppression and marginalisation, the fact that Aboriginal leaders like Jack Patten and William Ferguson also demanded an end to the damaging racist stereotypes in print media (and by extension advertising and stigmatising trade marks) is telling. Recognising the importance of the struggle against pernicious Aboriginal stereotypes in his pursuit of Aboriginal democratic rights, Patten declared:

Our huge task is to organise and educate ourselves for full Citizen Rights. We must win the respect and support of the white community by showing how unfairly we have been treated in the past. ...

...

‘Jackey-Jackey’ has been a joke for too long — a cruel joke. We have been for too long the victims of missionaries, anthropologists, and comic cartoonists. The white community must be made to realise that we are human beings, the same as themselves. Persecution of Aborigines here is worse than the persecution of Jews in other countries.

We have been called a ‘dying race’, but we do not intend to die. We intend

to live, and to take our place in the Australian community as citizens with

full equality.[232]

The kinds of dehumanising imagery decried by Patten were perpetuated through stigmatising trade marks, like those set out in this article. Circulating freely in colonial Australia and then the Commonwealth of Australia, these stigmatising trade marks helped to stifle Aboriginal communicative equality and equal participation in the broader Australian public sphere. To paraphrase Ferguson and Patten’s own words, these injurious representations undermined respect for Aboriginal Australians and prevented the White community from realising that Aborigines are human.[233]

In light of these historical records, is it surprising therefore to find those who respond so strongly today to racist taunts of Indigenous Australians that reference primates? Australian journalist and author Peter FitzSimons reminds us that, in Australia, ‘all those with black hair had been dispossessed of all their land ... vilified ... discriminated against, and treated almost like vermin’ (and, as shown above, often depicted as such in trade marks and commercial imagery[234]) and that a ‘frequent insult hurled at those with black hair, for generations, was that the black hair made you look like a monkey, the cruellest kind of taunt of all, claiming that those with black hair aren’t

even human’.[235]

These bigoted connections are not remnants of an unenlightened past. For example, on 24 May 2013, in the opening game of the Australian Football League’s (‘AFL’) Indigenous Round — intended to be a celebration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and the contribution by Indigenous Australian athletes to the game — Aboriginal athlete Adam Goodes, dual Brownlow Medalist, and the best on ground that day in Australia’s largest sporting arena, was subject to a racist taunt by a 13-year-old girl.[236] The girl had called him an ‘ape’. Goodes’ immediate post-game comments provide us with further insights regarding the damaging socio-psychological impact of racial epithets:

[T]his week is a celebration of our people, our culture, and I had the absolute privilege of meeting the great man, Nicky Winmar,[237] two days ago now, and what he was able to do for us 20 years ago, and to be able to make a stand myself and say, you know, racism has a face last night, and you know it was a 13-year-old girl, but it’s not her fault.

[The offender, a Collingwood supporter] is 13, she’s still so innocent, I don’t put any blame on her. Unfortunately, it’s what she hears, the environment she’s grown up in that has made her think that it’s okay to call people names. I can guarantee you right now she would have no idea... how it makes anyone feel by calling them an ape. ... It cut me deep and affected me so much that I couldn’t even be on the ground last night to celebrate a victory, to celebrate Indigenous round, and I am still shattered — personally, it’s tough.[238]

The abuse was compounded the following week when media personality and President of Collingwood Football Club, Eddie McGuire, ‘joked’ on his radio program that Adam Goodes should be recruited to promote the King Kong stage production.[239] Although devastated by these two racist attacks which ‘cut [him to his] core’,[240] Goodes, who draws his strength from his mother — a member of the Stolen Generation — continues to speak out against the wickedness of racism.[241]

Goodes’ brave stance and educative mission here speaks to the ways in which counterpublic spheres can potentially reorient and rehabilitate the broader public sphere or, at the very least, ensure that the injurious effects of stereotypes and stigmatising imagery do not remain unchallenged. The process of facing up to our past, writes Goodes, requires ‘understanding our very dark past, a brutal history of dispossession, theft and slaughter’.[242]

Due to Goodes’ indefatigable anti-racism campaign, subsequent epithets by another opposition fan directed at him — ‘Fuck off, Magilla the gorilla’ — have been challenged by crowd members, and also resulted in the offender being punished.[243] The Sydney Morning Herald clarified to ignorant readers[244] who deny that calling Goodes an ‘ape’ is racist: ‘Any empathetic, respectful adult would know the potential of the term to deeply offend a proud indigenous man.’[245] The troubling episode also prompted a recirculation of anti-racism material in New South Wales schools.[246] Yet, in the ensuing years, Goodes faced ‘unexplained’ relentless booing and jeering whenever he played.[247] While apologists attribute this as a reaction to Goodes’ style of play,[248] others have been more forthright:

Goodes is booed because he is Indigenous. Because in 2013 he called to account a 13-year old girl in the crowd who called him an ape. Because he was made Australian of the Year in 2014. And because he used his honour to challenge Australians about past treatment of indigenous people and the damage of racism.[249]

Most recently, Goodes’ proud expression of Aboriginality, through a cele-bratory post-goal Aboriginal war cry in the 2015 AFL Indigenous Round, directed towards opposition supporters while wearing an indigenous-themed guernsey designed by his mother, attracted faux outrage and sensationalist media coverage in some quarters.[250] Worse still, Goodes’ Wikipedia entry was subsequently defaced with monkey images.[251] The matter flared up again in July and August 2015, but public opinion was by then mostly in Goodes’ favour. Content with his remarkable achievements on the sporting field, and though wounded by his experience, Goodes has since retired from AFL football. Nevertheless, he has communicated his contentment in the educative function he played in drawing to attention the enduring harm caused by racist epithets in the public sphere.[252]

In yet another reverberation of the racist trope of ‘Indigenous person as ape’, another AFL Indigenous player, Eddie Betts, has had to contend with two separate instances of racial vilification: the first, a female Port Adelaide supporter who threw banana at him during his 250th match in 2016;[253] and then, in 2017, another supporter of the same team, on social media, referred to Betts as an ‘ape’ and called for him and his family to ‘go back to the zoo’ where they ‘belong’.[254] Like Goodes, Betts has responded magnanimously to these slurs by championing an educative mission tackling the scourge of deep-seated racism: ‘This is all about education, it’s never too late to learn’; ‘No one is born racist ... it’s ingrained in them somewhere down the track.’[255]

This article offers a provocative exploration of Australian Trade Mark Registers with a view to challenging a widely-held view that such registers contain bland trade marks of interest only to traders and trade mark practitioners. In this regard, this article has argued that trade marks are not limited to ‘badge of origin’ or ‘private property’ roles: there is also a ‘public discourse’ or ‘cultural’ role recognised by commentators, and present since the inception of trade mark registration systems in public interest oriented provisions restricting the registration of scandalous marks. If we accept this point, then trade mark registration systems ought to regulate the interests of traders and the general public inter se.

From the vantage point of minority and marginalised groups, however, those systems failed in colonial and Commonwealth Australia. An examin-ation of colonial and Commonwealth Trade Mark Registers demonstrates clearly that Indigenous Australians, Africans, Maoris, Native Americans, Chinese, and women (Black or White) were the subject of stigmatising registered trade marks. The historical record demonstrates that the protests and concerns of Aboriginal and other minority counterpublic spheres were largely ignored. Dominant commercial and other interests in the broader Australian public sphere appear to have drowned out these concerns.

While it might be contended that there is little benefit in commenting on the historical record through contemporary sensibilities, that approach, as convenient as it might be, is simply dangerous. Reviewing the history of trade mark registrations in Australia, at the very least, offers some important lessons. First, stigmatising registrations reveal the dangers of bureaucratic insensitivity to minority concerns and the potential for professional embarrassment. Second, shunning this history would be to once more ignore historical grass-roots protests against such representations and discount significantly the important role that historical Trade Mark Registers had in propagating and disseminating damaging stereotypes. As the Adam Goodes and Eddie Betts case studies above illustrate, racist tropes that manifest in the Register are not confined to their historical milieu, but rather remain an indelible part of the present-day lived experience for many marginalised communities, replete with their attendant injurious consequences. Finally, shining a light on the colonial and Commonwealth Registers’ dark history underscores that the state should avoid setting its imprimatur on stigmatising trade marks, by at the very least, denying trade mark registration to

such marks.

The contemporary Register of Trade Marks is no doubt vastly improved, insofar as it relates to racist registrations[256] and official practice,[257] but problems, which cannot be explored here, nonetheless remain. For instance, the Register reveals that misogynistic stigmatising marks often secure registration.[258] In a trade mark registration system unsensitised to these concerns, one which prioritises the property interests in trade mark law and not the dignity of people by failing to appreciate fully a trade mark’s cultural role, these outcomes are predictable, though not inevitable.

* BEco (Hons), LLB (Hons) (Syd), PhD (Syd); Senior Lecturer, The University of Sydney Law School. My sincere gratitude must go to Patricia Loughlan, Amanda Porter, Kym Sheehan and especially Kimberlee Weatherall, as well as the two anonymous referees for their excellent comments and suggestions on earlier drafts. I would also like to acknowledge the provocative insights and helpful comments offered by Graeme Austin, Mark Davison and Michael Handler in their examination of my doctoral dissertation, a portion of which appears in this article. All errors remain mine.

[1] ‘110 Years of Trade Marks’, IP Australia (Web Page, 28 June 2016) <https://www.ipaustralia. gov.au/about-us/news-and-community/news/110-years-trade-marks>, archived at <https://

perma.cc/4JWL-CW43>: IP Australia concedes here that trade marks reflect ‘changes in social, cultural and nationalistic attitudes of past generations’. See also Productivity Commission, Intellectual Property Arrangements (Inquiry Report No 78, 23 September 2016) 374–5.

[2] See, eg, ‘Trade Marks During WWI: The Anzac Brand’, IP Australia (Web Page, 7 February 2018) <https://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/understanding-ip/getting-started-ip/educational-mate rials-and-resources/ip-rights-wwi/trade-marks-WWI>, archived at <https://perma.cc/

7MUW-4KDS>; ‘110 Years of Trade Marks’ (n 1).

[3] The relevant current provision is s 42 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), which provides that ‘[a]n application for the registration of a trade mark must be rejected if: (a) the trade mark contains or consists of scandalous matter; or (b) its use would be contrary to law’. Its legislative ancestors in federal trade mark legislation were Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth) s 28 and, before that, Trade Marks Act 1905 (Cth) s 114. There were also colonial equivalents: see, eg, Trade Marks Registration Act 1876 (Vic) (40 Vict, No 539) s 8.

[4] Suffice it to say for present purposes that s 42 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) requires significant law reform so that it is better equipped to address the concerns raised in this article, especially as they affect marginalised groups. For a concise treatment of the relevant law and practice relating to this provision, see generally Robert Burrell and Michael Handler, Australian Trade Mark Law (Oxford University Press, 2nd ed, 2016) 164–9; Mark Davison and Ian Horak, Shanahan’s Australian Law of Trade Marks & Passing Off (Lawbook, 6th ed, 2016) 249–50 [25.730]; David Price, Colin Bodkin and Fady Aoun, Intellectual Property: Commentary and Materials (Lawbook, 6th ed, 2017) 671–5 [13.500].

[5] It is beyond the scope of this paper to offer this legislative solution, but any reform is likely to encounter some challenges, such as identifying the relevant legal test and audience in determining registrability, arguably unwarranted concerns by free speech activists, and the dilemma of so-called ‘reclamation’ of stigmatising trade marks by referenced groups — points that were considered in the recent US Supreme Court decision of Matal v Tam,

137 S Ct 1744 (2017) which held, by majority, that the disparagement provision in 15 USC

§ 1052(a) was unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment: United States Constitution amend 1.

[6] Patricia Loughlan, ‘The Campomar Model of Competing Interests in Australian Trade Mark Law’ (2005) 27(8) European Intellectual Property Review 289, 289 (‘The Campomar Model’).

[7] [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 (‘Campomar’).

[8] Loughlan, ‘The Campomar Model’ (n 6) 289.

[9] See, eg, William M Landes and Richard A Posner, ‘The Economics of Trademark Law’ (1988) 78(3) Trademark Reporter 267. Although this analysis ‘rests on a very particular approach to economics, one arguably not shared by the majority of economists’ (ie ‘Chicago economics’): Jonathan Aldred, ‘The Economic Rationale of Trade Marks: An Economist’s Critique’ in Lionel Bently, Jennifer Davis and Jane C Ginsburg (eds), Trade Marks and Brands: An Interdisciplinary Critque (Cambridge University Press, 2008) 267, 267.

[10] See Mark P McKenna, ‘The Normative Foundations of Trademark Law’ (2007) 82(5) Notre Dame Law Review 1839, 1844: ‘It would be difficult to overstate the level of consensus among commentators that the goal of trademark law is — and always has been — to improve the quality of information in the marketplace and thereby reduce consumer search costs.’ Although more recent scholarship has affirmed this basic principle as still providing the best explanatory value for trade mark protection, the problems of ‘genericness’ and abandonment of trade marks by traders have been identified as adding to, rather than decreasing, consumer search costs: see, eg, Stacey L Dogan and Mark A Lemley, ‘A Search-Costs Theory of Limiting Doctrines in Trademark Law’ (2007) 97(6) Trademark Reporter 1223.