Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

DOMINIQUE ALLEN[*] AND ALYSIA BLACKHAM[†]

Confidentiality has become an integral part of the individual enforcement model for equality law in Australia and the United Kingdom. Contrary to the focus on openness and transparency in the courts generally, confidentiality is embedded in the enforcement, process, and outcomes of equality law. In this article, we consider the role and utility of confidentiality in equality law in Australia and the UK. We scrutinise the ways confidentiality is embedded in the enforcement, process, and outcomes of equality law in each jurisdiction, including via an examination of statutory provisions, the processes adopted by statutory equality agencies, and the available information about claims. We argue that the enforcement of equality law requires a more nuanced balance between confidentiality and transparency to support the individual and systemic aims of equality law and the imperatives of the rule of law.

CONTENTS

Confidentiality has become an integral part of the individual enforcement model for equality law in Australia and the United Kingdom. This is largely due to the opportunities available to settle outside court processes and the desire by parties to avoid litigation. Alternative dispute resolution (‘ADR’) is used extensively to resolve claims in both jurisdictions and, in both, most discrimination claims settle with very few reaching an open court hearing.[1] The discussions between the parties during ADR, and often any procured settlement terms, are confidential. Contrary to the focus on openness and transparency in the courts generally, confidentiality is ingrained within equality law. The problem with this state of affairs is that the community at large in both countries is left unaware of the extent to which discrimination remains a problem and how it is (or is not) being addressed.

In this article, we consider the role and utility of confidentiality in equality law in Australia and the UK. We scrutinise the ways confidentiality is embedded in the enforcement, process, and outcomes of equality law, including via an examination of statutory provisions in each jurisdiction and whether they, in fact, restrict what information statutory equality agencies can release, the processes adopted by statutory equality agencies, and the available information about claims. In doing so, we analyse the potential impact of confidentiality on the effectiveness of equality law from both an individual and a societal perspective.

In Part II, we outline the process of resolving an employment discrimination claim in each country, and highlight the prevalence of settling and, consequently, confidentiality. Drawing on historical legislative materials and qualitative interviews with conciliators from the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (‘VEOHRC’) and solicitors who practice in anti-discrimination law in Victoria,[2] we consider the role and importance of confidential settlements to the enforcement of equality law from the perspective of those involved in the process.

The practical impact of confidential settlements and processes is compounded by the fact that equality agencies do not release much information about the outcomes negotiated in settlement agreements or the nature of claims, even in a de-identified form. In Part III, we consider what information the agencies actually make public. We then examine the restrictions imposed on the agencies by both privacy legislation and provisions in the founding legislation of the agency, and consider whether this helps to explain such practices. In Part IV, we draw on legal theory and literature on the rule of law to argue that there are inherent conflicts in the reliance on confidentiality in each jurisdiction. We argue that the enforcement of equality law requires a more nuanced balance between confidentiality — to support the individual — and transparency to support the systemic aims of equality law and the imperatives of the rule of law. In Part V, we offer suggestions for how this could be achieved.

ADR, usually in the form of conciliation, has been the preferred mode of resolving employment discrimination claims in the UK and Australia since equality laws were introduced. When establishing the legislative framework, governments in both jurisdictions (including state governments in Australia) intentionally redirected discrimination claims away from (public) court hearings towards (private) conciliation and ADR. Consequently, confidentiality has become embedded in the enforcement, process, and outcomes of the individual enforcement model adopted. In this part, we begin by outlining how an employment discrimination claim is resolved in the UK and then in each Australian jurisdiction, drawing attention to the centrality of confidentiality. Both jurisdictions largely rely on individuals enforcing statutory rights to address inequality and discrimination, and the majority of individual discrimination complaints are resolved via private agreement reached through confidential ADR processes.[3] This is set up in the legislative framework in both countries, as we outline below in Part II(A). However, not only is the complaint resolution process confidential, but settlement agreements often include a term that requires the parties to keep the settlement terms, and often the details of the complaint, confidential. Empirical data collected in Victoria shows that confidentiality clauses regularly feature in settlement agreements and are a key reason parties, particularly respondents, agree to settle. These findings are discussed in Part II(B).

There is a long history of reliance on conciliation in the enforcement of UK equality law.[4] Britain’s first equality agency, the Race Relations Board, was responsible for handling complaints and providing conciliation.[5] When the Race Relations Act 1965 (UK) was first raised in Parliament, the government noted that it did not regard conciliation as appropriate for dealing with discrimination in public places, instead favouring criminal penalties.[6] However, following pressure in Parliament, the Act ultimately made provision for the formation of the Race Relations Board and local conciliation committees to secure compliance with the Act, and for the ‘resolution of difficulties’ arising from its provisions.[7] Further, had the Act extended to the prohibition of discrimination in employment, then the government would have been strongly in favour of conciliation for resolving claims:

If the Bill had been intended to deal with the wider topics of employment and housing, sanctions of a different character would have been obviously more appropriate, possibly civil sanctions such as are made applicable in the United States and Canadian legislation which set up conciliation commissions and boards for dealing with discrimination in employment. Probably, however, completely informal conciliation processes would have been more acceptable to our way of thinking about such matters.[8]

Unsurprisingly, then, in the second reading speech for the Race Relations Act 1968 (UK) — which did extend to housing and employment — conciliation was put forward as a fundamental aspect of the Act’s machinery:

The Bill comprises three main elements. There is, first, a declaration of public policy that discrimination is unlawful on grounds of race, colour, ethnic group or nationality. The second main element is a process of conciliation. Under the Bill, machinery is provided for hearing all parties and all sides to the argument with a view to reconciling the differences. The third main element in the Bill is the enforcement provisions that will come into play if, and only if, the process of conciliation breaks down and the Race Relations Board decides to take further action. These three elements depend upon each other; they form a common pattern.[9]

The Act was passed in a context where machinery already existed for conciliation in industry, and ‘for practical reasons industry should make the maximum use of its own machinery for conciliation’.[10] Thus, the conciliation mechanisms in the Act were only intended to operate where industry did not already have a process of conciliation in place. Discrimination law in the UK was therefore passed in a context of existing processes of industrial negotiation, which framed the approach to be taken in this context.

Today, the statutory Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (‘Acas’) provides confidential individual conciliation and mediation free of charge to attempt to resolve employment disputes (including discrimination claims). As part of the system of early conciliation in place since May 2014, employees must contact Acas before making a claim to an employment tribunal.[11] In the Explanatory Notes to the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 (UK), this change was justified on the basis that:

At present there is no obligation on prospective claimants to contact ACAS and/or consider conciliation at any stage and an employment tribunal cannot refuse to accept a claim on the basis that a claimant has not contacted ACAS. In addition, there is no duty on ACAS to provide conciliation before a claim has been filed at an employment tribunal — there is only a discretionary power.

Of all the claims lodged at an employment tribunal, less than a fifth of claimants will have contacted ACAS for advice before submitting their claim. As a result, the opportunity for ACAS to offer pre-claim conciliation is limited. Section 7 therefore requires individuals to contact ACAS with details of their claim and obtain written confirmation that pre-claim conciliation has been declined or unsuccessful before they can present a claim to an employment tribunal.[12]

The change in process, therefore, appeared to be driven by a desire to give Acas the opportunity to offer conciliation in a wider range of claims. This change in the legislative framework has significantly increased the number of claims subject to conciliation: Acas reports that in 2016–17, 64.6% of employee-led early conciliation processes were taken up by employers, and 51.8% of claims subject to conciliation settled.[13]

Conciliation has been part of the framework for addressing discrimination claims in Australia since the legal framework was introduced. Guided by the UK’s experience, along with those of Canada and New Zealand,[14] all of Australia’s first anti-discrimination laws required the parties to attempt to resolve their claim informally before it could be heard by a court or tribunal.[15] However, when conciliation was introduced in Australia, comparatively little attention was paid to the confidential aspects of the process. That said, historical legislative debates make it clear that settlement was seen as the primary means by which complaints should be resolved, and that that was to be aided by private conciliation.

At the federal level, the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) established a Commissioner for Community Relations, tasked with examining complaints of racial discrimination and settling them through conciliation.[16] Introducing the Act, Attorney-General Kep Enderby said it ‘recognises that an emphasis on mediation and conciliation is a more satisfactory way of tackling individual instances of racial discrimination and the tensions that are associated with individual disputes’.[17]

The Commissioner was later replaced by the Human Rights Commission, which ultimately assumed a wider ambit than racial discrimination. Discussion in Parliament, on what became the Human Rights Commission Act 1981 (Cth), explicitly rejected including an enforcement mechanism for pursuing individual claims. As noted in the second reading speech:

It is only when the Parliament has laid down laws relating to human rights in a particular area — for example relating to racial discrimination — that the normal law enforcement machinery should be considered. Even there, the clear cut and authoritative decisions of the courts may not be the correct way to proceed, at any rate in the early stages of the operation of the law. The promotion of human rights in this country will be achieved more through education, through finding new balances of interests and through conciliation than through firm measures of enforcement.[18]

Thus, conciliation was seen as a softer means of pursuing a ‘balance of interests’, to be used in partnership with education. This was explicitly preferred to ‘firm measures of enforcement’.

This approach was replicated in the states and territories. In South Australia, the original Sex Discrimination Act 1975 (SA) made provision for confidential conciliation as the primary method for resolving complaints,[19] though there was no discussion in Parliament as to why this was the model adopted.[20] Reliance on confidential conciliation was also not addressed in the second reading speech for the later consolidation of equality law in South Australia.[21] It is likely, however, that this model of confidential conciliation was adopted from that in the UK, given the statute was developed with reference to (and was designed to ‘go beyond’) the evolving law in that jurisdiction.[22] As the first state in Australia to adopt equality legislation, it is possible that South Australia — along with the Commonwealth — set the trend for developments in other states.

In Victoria, a year later, the establishment of the Commissioner for Equal Opportunity was attended by an expectation that ‘the great majority of [sex discrimination] cases will in fact be settled by discussion and conciliation’.[23] The Commissioner was tasked with seeking to resolve allegations of discrimination via investigation and conciliation; ‘[w]hen, but only when’ that failed, the complaint could be referred to the Equal Opportunity Board.[24] Even at that early stage in the development of equality law, the Act included provision for the ‘confidentiality of information made available to the board, the commissioner or the staff during the operation of the Act’.[25] In the second reading speech, Premier Dick Hamer noted that

the creation of effective legal remedies against discrimination is an important objective of the Bill. Legislative declarations of principle are of little value unless they can be given practical expression.

However, the Bill also recognizes that an emphasis on mediation and conciliation is a more satisfactory way of tackling individual instances of discrimination and the tensions that are associated with individual disputes, and requires every effort to be made to settle complaints in this way.[26]

This arguably appears to acknowledge a potential tension between conciliation and the provision of effective legal remedies. Further, it also appears to frame claims of discrimination as being about ‘tensions’ between individuals, rather than breaches of societal norms. However, the Premier gave no justification for why conciliation was ‘more satisfactory’ for individual disputes than a court hearing.

Later that same month, in the second reading speech for the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW), Premier Neville Wran reinforced that conciliation was the primary method of resolving complaints, and attempting to settle complaints was the primary function of the Counsellor for Equal Opportunity:

The main feature of the counsellor’s functions is to attempt to settle, by conciliation or otherwise, the subject of the complaint. [They are] obliged, by clause 101(l), to endeavour to resolve a complaint in this way wherever that is possible. Clauses 102 and 103 relate to the conciliation proceedings. It is desired that as far as possible the counsellor be enabled to intervene in the dispute between the parties. It is desired to ensure that the proceedings be as informal as possible, so as to provide the most amenable atmosphere for compromise. For this reason, clause 102 provides that a complainant or respondent in conciliation proceedings shall not be represented by any other person except by leave of the counsellor. Clause 103(2) provides that evidence of anything said or done in the course of proceedings shall not be admissible in subsequent proceedings under this part relating to the complaint.[27]

This was reinforced even more emphatically in the Legislative Council: ‘It is emphasized that the most important means provided by this bill for the removal of individual discriminatory acts is by conciliating between the parties with a view to settling the complaints.’[28]

These speeches indicate that (private) conciliation was seen as fundamental for securing the political acceptability of the Act, and for securing its passage through Parliament.

In Western Australia, the delayed adoption of equality legislation (which was not introduced until 1984, eight years after Victoria and New South Wales, and nine years after South Australia) meant legislators had ‘the benefit of the experience of other places in the world as well as other States and the Commonwealth where similar legislation has been introduced’,[29] and consequently, the statutory bodies established under the Act were ‘adapted from models which have been functioning effectively and efficiently elsewhere for some time’.[30] More particularly, following the lead of the other states, the Western Australian legislation was ‘designed to facilitate negotiation, conciliation, and education rather than confrontation’,[31] and the Commissioner for Equal Opportunity was tasked with conciliating complaints. Conciliation would be in private, with the aim of ‘reach[ing] a mutually satisfactory settlement as quickly as possible and with as little fuss as possible’.[32]

When the remaining states and territories introduced equality law in the 1990s, conciliation was still seen as being at the heart of the model of dispute resolution. In the Australian Capital Territory, conciliation was seen as a key role of the newly formed Human Rights Commissioner.[33] The Commissioner was given a broad discretion and range of methods to deal with complaints, but

wherever possible, the Bill requires the commissioner to try to resolve a complaint by conciliation, that is, to reach a solution that is acceptable to all the parties. The experience in other jurisdictions is that by far the majority of complaints are settled in this way.[34]

The Commissioner was given the power to require parties to attend a compulsory and private conference.[35] However, they could also investigate matters via a public hearing: ‘The commissioner is free to choose which method is the most appropriate in a particular case or to adopt a combination of methods.’[36] While this still frames conciliation as the primary method of resolving complaints, it at least recognises that conciliation may be inappropriate for resolving some matters.

In Queensland, the Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Qld) (‘Qld Anti-Discrimination Act’) included recognition of ‘[a] two-tiered dispute-resolution system ... conciliation by an anti-discrimination commission followed, where conciliation is unsuccessful, by a hearing before an anti-discrimination tribunal’.[37] However, there was no discussion of the private nature of these conciliation proceedings.[38]

In the Northern Territory, the Anti-Discrimination Act 1992 (NT) (‘NT Anti-Discrimination Act’) was seen as being ‘based on a conciliatory, educational model, not an adversarial one’.[39] This was reiterated later in the second reading speech, perhaps to deflect any opposition to the proposed Act. The Minister for Public Employment, Shane Stone, said: ‘It has been the desire of the government to emphasise the conciliatory, non-adversarial theme of this proposed legislation.’[40] Thus, conciliation lay at the heart of the legislative framework.

In Tasmania, the view of the government was that ‘[t]he major impact of anti-discrimination legislation is educative’.[41] The main way of enforcing the statute was through private conciliation: ‘The focus in the grievance procedures is on conciliation. Conciliation conferences are conducted in private and any person investigating the complaint is also required to maintain a degree of confidentiality.’[42]

Consequently, conciliation is central to the enforcement model in each Australian jurisdiction, and they generally use the same model. For instance, at the federal level, the Australian Human Rights Commission (‘AHRC’) resolves complaints using conciliation, which it says is a process through which ‘people involved in a complaint talk through the issues with the help of someone impartial and settle the matter on their own terms’.[43] The process is required to be private, and things said in conciliation are not admissible if the case proceeds to court.[44] The AHRC does not publish much information about the nature of the complaints received or how they are resolved.[45] In the 2017–18 financial year, though, the AHRC conducted 1,262 compulsory conciliations. Of these, 931 (74%) were successfully resolved and less than 3% of complaints lodged at the AHRC proceeded to court.[46]

While the history of equality law differs in each Australian state and territory, the jurisdictions are consistent in treating discrimination as a personal wrong, which is best settled quickly and quietly behind closed doors. Rather than seeking ‘confrontation’, the various statutes were designed to be more conciliatory, while still intending to offer individual remedies.

This observation is certainly not new. In her groundbreaking work, Margaret Thornton argued that the individual, complaint-driven model of equality law, while embodying a view that discrimination is wrong, ‘chooses not to exert the punitive force of the law’.[47] The justification for this was ‘that discriminators should be treated gently, preferably in a confidential setting, by means of conciliation and persuasion, as their conduct invariably arises out of unconscious racism or sexism, rather than from a conscious animus’.[48]

Thus, this ‘vague notion of collective guilt’ infused the view of the ‘wrong’ prohibited by anti-discrimination laws,[49] and determined their (limited) means of enforcement. Conciliation relegates violations of anti-discrimination laws to be ‘private pecadilloes [sic]’.[50] As Thornton notes, the legislative model assumes that most discrimination claims will be resolved via conciliation, and that defendants will change their behaviour once they are ‘politely informed of the error of [their] ways’.[51] Thornton critiques this approach on the basis that it is ‘a somewhat naïve view of human nature’, and contrary to the presence of the ‘habitual respondent’ in discrimination claims.[52] Thus, reliance on confidential conciliation represents a long-established, though contentious, aspect of the enforcement of equality law in Australia.

In addition to the widespread use of confidential conciliation, confidentiality has become part of the complaint resolution process in Australia in another way: as a term of settlement. Leading discrimination barristers Chris Ronalds and Elizabeth Raper write that this term can be as narrow as the parties agreeing to keep the terms of settlement private — or much wider, to prevent the parties from disclosing that a complaint was made and the terms of the settlement.[53] Such clauses have prevented researchers from interviewing parties to claims that settled, or examining the outcomes negotiated at settlement.[54] For example, in their research on the experience of vulnerable clients in conciliation processes, researchers from Kingsford Legal Centre found that confidentiality clauses prevented them from examining the outcomes their clients received when they settled a discrimination claim.[55] While researchers have acknowledged how confidentiality clauses have restricted their research methods, they have not generally explored the frequency of such clauses in settlement agreements. That said, Charlesworth et al examined settlements in sexual harassment claims resolved at nine equal opportunity agencies over a six month period in 2009, finding that 16.9% included a confidentiality clause.[56] In this section, we attempt to shed some empirical light on the use and impact of confidentiality clauses, with a focus on Victoria.

This section reports on interviews conducted with five conciliators from the VEOHRC and 19 solicitors who practice in anti-discrimination law in Victoria. The interviews were conducted for a larger study of the State’s anti-discrimination law.[57] Semi-structured interviews were conducted by phone or in person between August 2017 and August 2018. The interview questions were designed to explore the participants’ opinions and experience with the dispute resolution process used in Victoria. The VEOHRC invited its conciliators to participate. A combination of directly approaching solicitors and ‘snowball sampling’ was used to recruit the solicitors who participated. The group of solicitors who were interviewed is narrow and by no means comprehensive, though multiple channels were utilised to recruit participants. The solicitors acted for parties in both state and federal claims. Of the solicitors, 14 primarily represented claimants and five primarily represented respondents, and they worked at a mix of mid and top tier law firms and community legal centres.

Participants were asked about whether confidentiality clauses were used in settlement agreements and their frequency. The solicitors said that they regularly encountered confidentiality clauses. Two respondent solicitors said that settlement agreements ‘almost always’[58] included a confidentiality clause. A claimant solicitor described confidentiality clauses as ‘not negotiable’ and said lawyers have to be ‘confident to push back’ and negotiate.[59]

A claimant solicitor said that their clients fell into two groups: one group that wanted confidentiality, and one that did not.[60] Similarly, a VEOHRC conciliator said that they encountered claimants who wanted to be able to talk about what happened, just as there were others who did not want people to know that they had made a complaint, particularly future employers.[61] At the time they were interviewed, a claimant solicitor had a matter that they thought would not settle because the claimant did not want to agree to confidentiality. The solicitor thought that the respondent would not be prepared to compensate the claimant without receiving something in return, namely confidentiality.[62] This is seen as a common practice. A claimant solicitor said that there is ‘a lot of pressure to maintain confidentiality from the respondent’.[63] Similarly, the conciliators reported that generally it is respondents who want confidentiality.[64] When asked about the inclusion of confidentiality clauses in settlement agreements, a conciliator said that they do not suggest that every agreement should contain one — rather, they raise it as one of the clauses the parties might want to include once the outcome itself has been agreed upon.[65] However, both conciliators and solicitors cited confidentiality as one of the primary reasons respondents decide to settle.[66] As a claimant solicitor said:

[R]espondents will often settle because there’s obviously the publicity factor. It’s not good to have your name associated with certain types of actions, particularly sexual harassment ... and because they know that win, lose or draw, their name will always be associated with those allegations.[67]

Confidentiality clauses do not just cover settlement terms: they often extend to the complaint itself, any internal investigation, and the settlement negotiation process.[68] There is, however, scope to tailor confidentiality clauses to suit the individual claimant. A claimant solicitor said that they had encountered respondents who have agreed to a clause that permitted the claimant to discuss the claim with their family, but not anyone other than them.[69]

Although some respondents might agree to a minimal level of transparency, the interview data recounted in this section reinforces the general dominance of confidentiality as a term of settlement (at least in Victoria) and explains the reasons for its prevalence. What is missing from this picture is the views of parties to claims and whether, for example, complainants actually do desire confidentiality, or whether they feel compelled to agree to it in return for, say, a larger sum of financial compensation than they may be offered otherwise. The problem for researchers is, of course, that once a party has agreed to a confidentiality clause, it is difficult to discuss their claim with them because they are in jeopardy of breaching the clause. As we note in Part V, the Australian Sex Discrimination Commissioner has attempted to navigate this problem in order to collect evidence for the inquiry into the prevalence of sexual harassment.

In the context of equality law, openness and transparency have increasingly yielded to the push for confidentiality, which lies at the heart of the enforcement model used in both countries. We return to the conflict between confidentiality and transparency in Part IV. Our starting point, though, is that because of the extensive use of confidentiality in both system design and the terms of settlement, it is very difficult to know much about the types of discrimination that exist, the prevalence of discrimination in society, or how it is being addressed.

One way of assessing this is, of course, to examine court decisions. However, this would not provide a complete picture. Strong cases frequently settle, possibly even more often in equality law than other areas of law because respondents fear the reputational damage they might incur if they defend a claim.[70] Conversely, weak, spurious and vexatious claims often reach a hearing,[71] which paints a distorted picture of the prevalence of discrimination and how it is affecting people. The orders made by courts are often not in keeping with what the parties are able to negotiate at settlement, both in terms of quantum and the prevalence of systemic remedies.[72] Thus, it is difficult to state with any certainty that the claims before courts reflect what is happening in the community, or that the remedies awarded by courts are the most suitable ways of addressing discrimination or adequately measuring the harm caused.

Court decisions are thus not a suitable source of information if seeking to assess the prevalence of discrimination or how discrimination claims are resolved. Instead, it is better to assess these questions using conciliation and settlement data, as this more accurately depicts the actual claims that are made and resolved. In Australia, equal opportunity agencies are the gatekeepers of this information because complaints must be lodged with them before the claimant can proceed to court (except in Victoria, though most claimants have continued to approach the agency first anyway).[73] In the UK, this data is largely held by Acas, which conducts conciliation for discrimination claims in employment.[74]

In this part, then, we examine what information the agencies actually do release about claims and their outcomes, and the extent to which this resolves the issues posed by confidentiality in the enforcement of equality law. We then examine the legislative constraints that may prevent them from releasing such data. We argue that the adverse impact of confidentiality in the enforcement of equality law is amplified by the fact that the agencies release very little information about the outcomes obtained at settlement, the nature of discrimination claims, or the prevalence of discrimination in the community, other than statistical complaint data.

Table 1 presents the type of information made available by each equality agency in Australia and by Acas in the UK, and whether it is published in the agency’s most recent annual report, on its website, or both.

Table 1: Settlement Information Released by the Agencies

|

Jurisdiction

|

Claim statistics

|

Outcome of complaint handling process

|

Conciliation case studies

|

Selection of settlement outcomes

|

|

Australia — Cth

|

AR[75]

|

AR

|

AR, W

|

W

|

|

ACT

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR, W

|

W

|

|

Qld

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR, W

|

W

|

|

NSW

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR, W

|

W, Monthly newsletter

|

|

NT

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR

|

–

|

|

SA

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR, W

|

|

Tas

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR

|

–

|

|

Vic

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR

|

W

|

|

WA

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR

|

AR, W

|

|

Great Britain

|

AR

|

AR (for all employment claims)

|

–

|

–

|

|

Northern Ireland

|

AR

|

AR

|

–

|

W[76]

|

AR = the agency’s 2016–17 annual report (except for South Australia which refers to its 2015–16 annual report); W = the agency’s website

Very limited information is made publicly available by the statutory bodies about the nature of discrimination complaints and their outcomes.[77] As Table 1 shows, all of the agencies publish data about the number of complaints they received during the previous financial year. Complaints are usually reported against the attribute(s) upon which the claim was lodged and, in the case of Australia, the area of activity.[78] Similarly, all agencies report the outcome of the conciliation process, which is usually the number of claims that were referred to conciliation, terminated, withdrawn, referred to another agency or referred to court for a hearing. Some agencies also report on the time taken to resolve a claim, which is often measured against key performance indicators; the percentage of claims that were successfully conciliated is also often reported.[79] Across the agencies, though, how this information is reported, and the detail provided, is not consistent.

All of the Australian agencies usually include case studies or examples of successful conciliations in their annual report, which usually includes an overview of the facts and the negotiated outcome.[80] For example, the AHRC’s 2016–17 annual report includes the following case study:

The complainant, aged 71, experiences pain when walking long distances and uses a walking stick. She claimed the layout of a domestic airport she used required passengers to walk long distances. She claimed there were no travelators, there was limited seating, and she could not find staff to provide assistance or a wheelchair.

The airport agreed to take part in conciliation. The complaint was resolved with an agreement that the airport improve signage, provide maps indicating walking distances, review availability of seating and operate a transport service within the airport for passengers who need assistance with mobility. The airport also agreed to review customer service training provided to staff.[81]

All of the Australian agencies — except Tasmania’s — publish examples of conciliations on their website. These are much like the case studies in the annual reports — the examples describe the nature of the claim and how it was resolved. Some — such as the AHRC[82] and the Anti-Discrimination Board of NSW[83] — are more comprehensive than others, in that they contain more examples, provide more details, or include the year the claim was settled. Alternatively, others — such as Victoria[84] and Western Australia[85] — include fewer examples. What is common to all jurisdictions is that none claim to offer a complete database of all the claims settled at the agency: they all state that the list is only a ‘selection’ of successful conciliations.[86]

South Australia is the only jurisdiction that releases data about the outcomes negotiated at settlement during the previous financial year. This is displayed in the form of a graph, which shows the percentage of settlements that included each type of remedy.[87]

Table 1 also shows that, by comparison, the UK agencies release very little information about discrimination claims. Part of the reason for this is a difference in process. Neither the equality agency in Great Britain[88] nor the agency in Northern Ireland is required to receive claims; instead, for employment claims, conciliation is conducted by Acas and the Labour Relations Agency respectively. Conciliation is not available for complaints that are not about employment. Therefore, the equality agencies can only collect data about claims that they provide assistance for, and this data does not give a complete picture of discrimination claims. The equality agencies could, however, publish case studies or vignettes so that potential claimants and respondents have a greater understanding about how the law operates — a recommendation we return to in Part V. In addition, Acas and the Labour Relations Agency are less concerned with discrimination claims than with conciliating employment claims generally, so their mandate to report has a different focus. Furthermore, Acas has also only been responsible for handling all complaints since the introduction of early conciliation in 2014,[89] meaning there has been less time for it to refine its reporting strategy.

As government agencies, the statutory equality agencies in both countries are covered by strict privacy obligations. As we argue in this section, these privacy obligations, either directly or indirectly, are reducing the willingness of statutory agencies to release information about equality claims. Thus, they are compounding the risks of confidentiality in the enforcement of equality law.

In Australia, privacy obligations arise under: (1) the statutes creating the equality bodies themselves;[90] (2) discrete privacy legislation;[91] and (3) public service policies.[92] In relation to the federal AHRC, s 49(1) of the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (‘AHRC Act’) prohibits staff of the AHRC from disclosing ‘any information relating to the affairs of another person’ acquired through the Commission’s operations. If breached, the penalty is 50 penalty units (equivalent to $10,500 as at November 2019) or imprisonment for one year, or both.[93] However, information may be disclosed ‘in the performance of a duty under or in connection with [the Act]’, or ‘in the course of acting for or on behalf of the Commission’.[94]

In relation to privacy legislation, the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) regulates how personal information is to be handled, including by the AHRC. ‘Personal information’ is defined broadly as

information or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is reasonably identifiable:

(a) whether the information or opinion is true or not; and

(b) whether the information or opinion is recorded in a material form or not.[95]

This is broad enough to include a raft of information — whether it is sensitive or not — so long as an individual can be identified.

Under Australian Privacy Principle 6,[96] if personal information is collected for a particular purpose, it must not be used or disclosed for a secondary purpose unless:

• the individual has consented to the use or disclosure;[97]

• the individual would reasonably expect the use or disclosure of the information for the secondary purpose, and the secondary purpose is:

• if it is sensitive information — directly related to the primary purpose;

• if it is not sensitive information — related to the primary purpose;[98]

• it is required or authorised by or under an Australian law or a court/tribunal order;[99]

• the entity (here, the AHRC) ‘reasonably believes that the use or disclosure of the information is reasonably necessary for one or more enforcement related activities conducted by, or on behalf of, an enforcement body’.[100]

‘Enforcement body’ relevantly includes an ‘agency, to the extent that it is responsible for administering, or performing a function under, a law that imposes a penalty or sanction or a prescribed law ... [and] a State or Territory authority, to the extent that it is responsible for administering, or performing a function under, a law that imposes a penalty or sanction or a prescribed law’.[101] While discrimination is unlawful in Australia, equality law does not generally impose penalties or sanctions. However, some sanctions do appear in equality statutes: for example, s 50 of the Age Discrimination Act 2004 (Cth) creates a strict liability offence, and imposes a penalty, for discriminatory advertising; s 51 creates an offence, and imposes a penalty, for victimisation; and s 52 creates an offence, and imposes a penalty, for a failure to disclose the source of actuarial or statistical data. Complaints can be made to the AHRC about conduct that is an offence under these sections. Thus, at least in this limited sense, the AHRC is responsible for performing a function under a law that imposes a penalty or sanction.

‘Enforcement related activity’ is relevantly defined as including ‘the prevention, detection, investigation, prosecution or punishment of ... breaches of a law imposing a penalty or sanction’ and ‘the preparation for, or conduct of, proceedings before any court or tribunal, or the implementation of court/tribunal orders’.[102]

In sum, then, there is some limited scope for the AHRC (and state and territory authorities) to reveal personal information in their enforcement activities. However, perhaps more relevantly, information can be revealed if it does not constitute ‘personal information’ — that is, if an individual is not identified, or is not reasonably identifiable.[103] Thus, de-identified data on claims and outcomes can be released in compliance with the Australian Privacy Principles. We return to this in Part V, where we consider what (additional) information could be released by statutory agencies and how.

The AHRC Privacy Policy makes limited provision for the release of personal information to third parties, including to third parties engaged by the AHRC to provide certain functions on the AHRC’s behalf (such as ‘compil[ing] raw data for research purposes’), and to third parties that individuals authorise the AHRC to give access to personal information.[104]

Similar provisions are enacted in some Australian states. In Victoria, though, the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic) (‘Vic Privacy Act’) includes an additional provision for the disclosure of personal information for research. Under Principle 2, personal information may be disclosed for a secondary purpose where it is

necessary for research, or the compilation or analysis of statistics, in the public interest, other than for publication in a form that identifies any particular individual [and]

(i) it is impracticable for the organisation to seek the individual’s consent before the use or disclosure; and

(ii) in the case of disclosure — the organisation reasonably believes that the recipient of the information will not disclose the information.[105]

This makes explicit provision, then, for the disclosure of personal information where it will be published in a de-identified form. This potentially allows for far greater release of information for research purposes, potentially facilitating greater transparency in Victoria.

Section 176 of the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Vic) (‘Vic Equal Opportunity Act’) prohibits VEOHRC staff from disclosing ‘information concerning the affairs of any person’ acquired through their functions or duties. If breached, the penalty is 60 penalty units for an individual (equivalent to $9,913.20 as at November 2019).[106] However, an exception is explicitly provided for in s 177 for the disclosure of information ‘relating to disputes, complaints or investigations’ if the disclosure is ‘made for the purpose of the Commission’s educative functions’ and is ‘consistent with the Commission’s obligations under [statute]’, including the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) and the Vic Privacy Act.[107] Without limiting this exception, express provision is made for the disclosure of information if it: does not identify any person; is already in the public domain; or all relevant parties have consented.[108] Again, then, this supports the release of de-identified information. Notably, the previous version of the Act contained a much vaguer provision, which was (ominously) headed ‘Secrecy’.[109] In Julian Gardner’s review of the Act (‘Gardner Review’), he noted that there was a perception that the VEOHRC was reluctant to use de-identified information because of the uncertainty of what that provision permitted.[110] He recommended that it be made clear that the Commission could use de-identified information about claims for educational purposes.[111] However, as we describe above, that reluctance persists — at least in the context of agency reporting.

Confidentiality provisions are replicated in most statutes regulating Australian equality agencies at state, territory, and federal level.[112] However, confidentiality requirements are not explicitly imposed on the equality agency in South Australia or Tasmania.[113] In Tasmania, the Commissioner is only required to ‘have regard to the desirability of maintaining the confidentiality of all persons involved in the investigation’.[114] In these jurisdictions, agencies will still be bound by the state’s general privacy law.

Where statutory confidentiality provisions are in place, it is difficult to generalise across the provisions in the different Australian states and territories. In relation to research, for example, there is no explicit mention of an exception for research at the federal level, nor in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, Victoria, or Queensland. In the Australian Capital Territory, disclosure for research still needs the consent of the parties.[115] In New South Wales, the Board can ‘liaise or collaborate with academics’, and facilitate disclosure accordingly.[116] That said, even where there is not an explicit exception, ‘research’ and ‘education’ may fall within the duties, functions or powers established under the equality acts,[117] or the administration of the relevant Act,[118] which are exempt, potentially facilitating the disclosure of information. Even in this case, though, some statutes require the relevant Commissioner to reasonably believe the disclosure to be ‘necessary or appropriate’,[119] or for the disclosure to be ‘necessary’[120] or ‘required’[121] in exercising those functions or powers. This is a high hurdle for equality agencies to surmount, particularly where there are criminal penalties in the offing. It is unsurprising, therefore, that some equality agencies would err on the side of non-disclosure; it is likely that these statutory provisions have had a substantial chilling effect on transparency in practice.

In most jurisdictions, there was limited attention paid to the possible consequences of confidentiality when these statutory restrictions were introduced. No reference was made to these provisions in the second reading speeches for the AHRC Act, Human Rights Commission Act 2005 (ACT), Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT), NT Anti-Discrimination Act, Qld Anti-Discrimination Act, or Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA). The provision was only mentioned in passing in the second reading speech for the Equal Opportunity Act 1977 (Vic), and the amendment of the provision was not mentioned in the second reading speech for the more recent Vic Equal Opportunity Act.[122]

The most detailed consideration of these provisions occurred in New South Wales, where the confidentiality provision was introduced by the Anti-Discrimination Amendment (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2004 (NSW). In the Legislative Assembly, the second reading speech justified the provision on two grounds. First, that it would prevent information held by the Board from being subpoenaed or being subject to a freedom of information request (which reportedly occurred regularly).[123] Second, that

[t]here is a risk, albeit a small one, that details of a complaint could be disclosed by officers of the board to the media, a relative or a prospective employer without sanction. Most other equal opportunity jurisdictions in Australia have provisions in place to govern the actions of public officers in relation to personal information contained in the complaint and acquired during its investigation. It is appropriate that New South Wales does also.[124]

The change was therefore seen as being designed ‘to protect the integrity of the complaint resolution process and to encourage persons to bring complaints’.[125] This risk — of agency staff revealing personal information without consequence — appears overblown and unlikely, particularly given the presence of privacy legislation in Australia. It is questionable, then, whether these confidentiality provisions and their possible practical consequences were adequately considered by the legislature, and whether they add any practical value over and above privacy legislation.

In the UK, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (‘GDPR’)[126] has been implemented by the Data Protection Act 2018 (UK) (‘UK Data Protection Act’).[127] The GDPR requires that personal information be ‘collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes’.[128] However, further processing for research purposes is not considered incompatible, so long as it is subject to appropriate safeguards in accordance with art 89(1).[129] This opens up significant scope for research using personal data, even when research was not the original purpose of the data collection. That said, the safeguards required by art 89(1) might require measures such as pseudonymisation or ‘processing which does not permit or no longer permits the identification of data subjects’.[130]

As in Australia, provision is also made in the founding statute of the Equality and Human Rights Commission (‘EHRC’) for the (non-)disclosure of personal information. Section 6 of the Equality Act 2006 (UK) creates an offence for Commission staff who make a disclosure of information that is not authorised. The section applies to information acquired by the Commission through inquiries, investigations, assessments, notices and agreements.[131] However, disclosures are authorised if made: for the purpose of exercising the Commission’s functions in relation to inquiries, investigations, unlawful act notices, applications, and public sector equality duty assessments;[132] or in a report of an inquiry, investigation or assessment published by the Commission.[133] Further, explicit authorisation is given for disclosures made ‘in a manner that ensures that no person to whom the disclosed information relates can be identified’.[134] Again, this facilitates the release of de-identified information, including for research purposes.

Confidentiality provisions are also in place for Acas. Under s 251B(1) of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 (UK), information held by Acas cannot be disclosed if it ‘relates to a worker, an employer of a worker or a trade union’ and is held by Acas in connection with the provision of its services (by Acas or its officers).[135] Disclosure can result in a fine not exceeding £5,000.[136] However, under subsection (2), information may be disclosed if it is ‘for the purpose of enabling or assisting ACAS to carry out any of its functions under this Act’, or if the disclosure is ‘made in a manner that ensures that no relevant person to whom the information relates can be identified’,[137] so long as the disclosure is consistent with the UK Data Protection Act (previously with its 1998 iteration).[138] Thus, it is again clear that de-identified data can be released.

The previous sections have mapped the ways in which confidentiality is embedded in the enforcement of equality law in both jurisdictions. It is integral to the conciliation process, and generally relied on in the drafting of settlement agreements. This is compounded by the wide-ranging, technical and punitive statutory provisions that require equality agencies to keep confidential the information they collect. In this part, we consider the reasons for, and implications of, this reliance on confidentiality, and how it relates to theories of the rule of law and open justice.

There are good reasons to embed confidentiality in the enforcement process for equality law. It allows parties to negotiate in conciliation without fear that what was said could be used in future litigation. It therefore creates a ‘[safe] haven’ for both parties, who can ‘express emotions’ and communicate their ‘true interests’ without fear of public judgment.[139] Confidentiality may encourage people to lodge claims and encourage respondents to participate in resolving them. It also protects both parties from potential reputational damage from being involved in a discrimination claim, particularly the risk that the media might show an interest in the claim if it proceeds to court. In earlier empirical research, Allen documented that avoiding publicity is a significant reason respondents decide to settle.[140] Thus, confidentiality has significant benefits in facilitating the efficient resolution of discrimination complaints, and can benefit both claimants and respondents.[141]

Equally, though, embedding confidentiality in the equality law enforcement process has significant drawbacks. Keeping both processes and outcomes confidential means that there is very limited guidance regarding what claimants and respondents can expect from the law, including in relation to remedies (both monetary and systemic). It is difficult to evaluate whether the law is achieving its purpose, both in remedying the individual claimant’s situation and in achieving broader, systemic outcomes. This is made more problematic by the limited data released by equality agencies. Similarly, there is limited guidance for equality agencies, lawyers and courts on how to resolve discrimination claims, or what remedies are appropriate. This makes it more difficult to frame subsequent claims, as there is little guidance or precedent to indicate how the law is evolving, or what the likely outcomes would be. This might particularly disadvantage unrepresented claimants,[142] and, as discussed below, potentially undermine the rule of law.

Confidentiality, therefore, masks the extent to which discrimination remains a problem in society. There is limited public scrutiny of instances of discrimination, or the outcomes achieved when discrimination claims are settled. This may lead to substandard outcomes being tolerated, and may undermine the ability of equality law to achieve systemic outcomes as part of a ‘project of cultural transformation’.[143] Instead of being treated as ‘public transgressions in the way that crimes are treated’, discrimination complaints are consigned to the private sphere.[144]

By relegating claims and their resolution to the private sphere, confidentiality also reinforces the individualisation of equality law in Australia and the UK. For Thornton, ‘[t]he atomism inherent within the confidential conciliation process underscores the notion that acts of discrimination are of an isolated and individualistic nature and that individualistic solutions alone are appropriate’.[145]

For Thornton, then, conciliation also reinforces the public–private divide in liberal societies, with discrimination being seen as something that is private and which should be addressed behind closed doors.[146] Similarly, in the UK employment context, a renewed focus on ADR has been seen as a means of privatising the enforcement of employment rights.[147] In this model of confidential conciliation, ‘neither deliberations nor the outcome are made public, diminishing the diffusion of best practice usually derived from public hearings’.[148] This undermines a key objective of equality law: to promote the participation of all groups in public life. Equality law is then unlikely to be able to achieve systemic outcomes because discrimination is seen as an individual problem which individualised negotiations can resolve.

Finally, statutory confidentiality clauses and privacy legislation mean there is limited scope to research discrimination complaints and their outcomes, and to evaluate the law and its effectiveness. Thornton and Luker write:

Research in the field of anti-discrimination law is fraught with difficulties. ... [I]t has been our experience that most anti-discrimination agencies fiercely guard the confidentiality requirement, making it difficult to conduct research which would reveal important information about the process.[149]

This limits the potential for critical review of the operation of equality law in both jurisdictions. The question that must then be addressed is whether the current system appropriately balances the need for confidentiality with the need for transparency.

Relying on confidentiality to this extent appears to run counter to the general ambitions and goals of legal processes in liberal democratic countries, and highlights the inherent tensions between confidential enforcement of discrimination law and ideas of open justice. Confidentiality is rarely associated with the court process or with liberal democratic systems of justice. Rather, the rule of law (which courts have a key role in upholding)[150] requires openness and transparency of legal decision-making. More specifically, the rule of law requires the law to be sufficiently clear to guide an individual’s conduct.[151] For individuals to be able to plan their lives, they must be ‘guided by open, general and clear rules’.[152] Therefore, upholding the rule of law requires court decisions to be communicated effectively to those whose behaviour they are guiding: that is, the community at large. Thus, openness of court outcomes is essential to the rule of law.

The rule of law also requires that courts operate in a way that is open and accountable to the general public. This is fundamental to securing ‘an open, public administration of justice, with reasoned decisions by an independent judiciary, based on publicly promulgated, prospective, principled legislation’.[153] As Raz argues:

Principled decisions are reasoned and public. As such they become known, feed expectations, and breed a common understanding of the legal culture of the country, to which in turn they are responsive and responsible. The courts are not formally accountable to anyone, but they are the most public of governmental institutions. They are constantly in the public gaze, and subject to public criticism. Thus their decisions both mould the public culture by which they are judged and are responsive to it.[154]

Therefore, open justice is essential for upholding the rule of law and maintaining public confidence in the legal process. Open justice requires that court processes be open to all, operate fairly, and function efficiently and effectively. Open judicial proceedings encourage public confidence in the judicial process. As noted by French CJ in South Australia v Totani,[155] ‘[t]he open-court principle, which provides ... a visible assurance of independence and impartiality, is also an “essential aspect” of the characteristics of all courts’.[156] In more colloquial terms, ‘justice must not only be done, but be seen to be done’.[157] As noted by Lord Phillips in Secretary of State for the Home Department v AF [No 3],[158] ‘if the wider public are to have confidence in the justice system, they need to be able to see that justice is done rather than being asked to take it on trust’.[159] Closed court processes are ‘corrosive of justice and public confidence in justice’[160] and a ‘lack of visibility is likely to diminish respect for the system, whatever the quality of justice actually delivered’.[161]

Further, open court processes provide an essential check on judicial power, and encourage the just determination of judicial proceedings. Indeed, Bentham posited open justice as a key constraint on judicial power, and fundamental for the judiciary’s legitimacy as a democratic institution:

Environed as ... [the judge] sees [themselves] by a thousand eyes, contradiction, should [they] hazard a false tale, will seem ready to rise up in opposition to it from a thousand mouths. ... Without publicity, all other checks are fruitless: in comparison of publicity, all other checks are of small account.[162]

Openness requires the public transparency of court proceedings — and, arguably, a degree of transparency in ADR. According to Lord Dyson JSC in Al Rawi v Security Service,[163] ‘[t]he open justice principle is not a mere procedural rule. It is a fundamental common law principle.’[164] Indeed, it ‘ought to be regarded as sacrosanct, as long as [it does] not lead to a denial of justice’.[165]

The importance of public openness is further embodied in art 6(1) of the European Convention on Human Rights (‘ECHR’),[166] which provides:

In the determination of ... civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge ... everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing ... Judgment shall be pronounced publicly but the press and public may be excluded from all or part of the trial in the interests of morals, public order or national security in a democratic society, where the interests of juveniles or the protection of the private life of the parties so require, or to the extent strictly necessary in the opinion of the court in special circumstances where publicity would prejudice the interests of justice.

As the ECHR foreshadows, while openness is essential for the proper administration of justice, it is not absolute. While ‘open justice is, as we all acknowledge, of the highest constitutional importance’, it must occasionally yield to other imperatives.[167] While confidentiality can play an important role in facilitating settlement and open discussion, confidentiality plays too large a role in the current enforcement models of equality law in Australia and the UK. However, with some changes, each country could alleviate the major tensions between transparency and confidentiality, as we explain in Part V.

Recognising the need to balance confidentiality with appropriate transparency, there are three key reforms that could facilitate a more open and accountable enforcement of equality law in Australia and the UK.

First, it appears that privacy legislation and statutory confidentiality provisions in both jurisdictions generally allow de-identified information relating to discrimination complaints to be released. Further, most statutes allow information to be disclosed where this is consistent with the powers, functions or duties of the equality agencies. The issue, though, is that imposing criminal penalties — including potential jail time — for an accidental or well-intentioned breach of an ambiguous provision is inevitably going to have a chilling effect on the release of information. At a minimum, then, the statutory confidentiality provisions should be reformed, to make it clear that de-identified information can be released, or to facilitate the release of information to researchers if they undertake to maintain confidentiality and only release information in a de-identified form.[168] More generally, though, there is a need for a serious review of whether these provisions are actually required, given agencies are already bound by privacy laws.

Second, and even recognising the problems raised by these statutory provisions, there is far more scope for the release of data about the claims that are made and resolved through conciliation than is currently taking place. Releasing more information would facilitate a better understanding of the prevalence of discrimination in society, the areas in which it is most common, and the sorts of claims and outcomes that can be expected by parties. This would significantly enhance the administration of justice in accordance with the rule of law.

The Gardner Review in Victoria recommended that both the agency and the tribunal should publish de-identified settlement outcomes, and that secrecy provisions should be amended to permit this.[169] Unfortunately, these recommendations were not implemented, although the secrecy provisions were amended. More particularly, though, we suggest that it would be useful for the statutory agencies to release the following de-identified data about claims and conciliation: demographic data about the claimant (eg age, sex, birthplace, occupational classification) and the respondent (eg individual or business, business size, industry classification); whether or not the parties were represented and by whom; and the settlement terms (including the amount of compensation and whether it was for economic or non-economic loss, and any systemic outcomes).

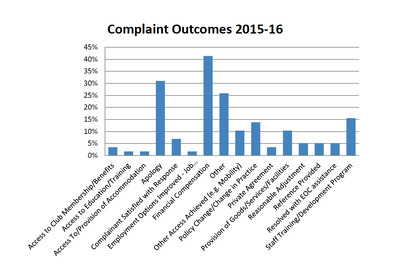

The South Australian Equal Opportunity Commission offers a good example of how information about the terms negotiated in settlement agreements could be released. Its 2015–16 annual report contained the graph depicted below in Figure 1.[170]

Figure 1: Information Released by the South Australian Equal Opportunity Commission about Settlement Agreements, 2015–16

Of course, it will generally be time-consuming for statutory agencies to prepare de-identified data for public release, particularly where information is not being kept and maintained at present. It is in these scenarios that academic researchers could well assist with the development of datasets, which would also help with their own research and scholarship.[171]

Third, and finally, it is timely to review the reliance on non-disclosure provisions in settlement agreements. This is currently under scrutiny in the UK, where the EHRC has identified the problems associated with non-disclosure agreements in the context of workplace sexual harassment.[172] In its 2018 report, the EHRC noted:

Confidentiality clauses used in settlement agreements after the allegation of harassment has been made may ... prevent people from speaking about their experiences and reduce the likelihood of systemic problems being tackled. These clauses should be more closely regulated.[173]

Thus, the EHRC called on legislative reform to make void contractual clauses that prevent disclosure of future acts of discrimination, harassment or victimisation.[174] Further, it recommended the introduction of a code of practice for organisations, which should set out when confidentiality clauses preventing disclosure of past acts of harassment will be void, and setting out best practice in the use of confidentiality clauses in settlement agreements.[175] This could include practices such as: paying for the employee to receive independent legal advice on the terms of the agreement; providing a reasonable amount of time to consider the terms of the agreement; allowing the employee to be accompanied by a trade union representative or colleague when discussing the agreement; only using confidentiality clauses at the employee’s request (except in exceptional circumstances); and attaching a statement to the settlement agreement explaining why confidentiality clauses have been included and what they mean. The EHRC released guidance on the law relating to confidentiality agreements in employment in October 2019; this was not a statutory code.[176] These reforms could significantly assist individual claimants in negotiating the terms of settlement agreements; however, they will offer only limited additional transparency in the context of settlement outcomes. Indeed, as the EHRC noted, privately negotiated settlement agreements often have ‘more extensive confidentiality provisions’ than those negotiated through statutory bodies such as Acas.[177]

The UK government conducted a consultation process in 2019 to consider limitations that might be put on workplace confidentiality clauses.[178] It concluded that legislation should be introduced to: ensure that confidentiality clauses have clear limitations and do not prevent reporting to the police, regulated health and care professionals or legal professionals; and improve independent legal advice on settlement agreements.[179] The government also flagged the need to introduce new enforcement measures for confidentiality clauses that do not comply with legal requirements.[180] These changes were not implemented by the end of 2019.

We argue that this review of confidentiality clauses should go further to scrutinise the use of non-disclosure agreements in all discrimination settlements. There are strong reasons for publicising the outcomes of discrimination complaints, particularly where employers are repeat offenders. It may be desirable to negotiate that employers make a public statement relating to any claims that are settled, acknowledging the discriminatory conduct in a public way. This has the potential to act as a significant deterrent, and a prompt for systemic change.

Similar concerns have been raised in the context of the AHRC’s National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces,[181] where non-disclosure agreements imposed as part of a settlement generally prevented individuals from making a submission to the Inquiry. The Australian Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Kate Jenkins, sought to navigate this problem by asking Australian employers ‘to issue a limited waiver of confidentiality obligations in non-disclosure agreements ... for the purpose of allowing people to make a confidential submission’ to the Inquiry.[182] This appeal to employers’ altruism was surprisingly effective, with around 25 ‘key’ employers agreeing to a partial waiver.[183] This ad hoc, partial solution (especially given there were 3,855 businesses in Australia with 200 or more employees in 2017–18)[184] arguably emphasises the dramatic need to reduce the use of non-disclosure provisions in settlement agreements more generally, particularly when seeking to reveal the prevalence of discrimination as a systemic problem.

Confidentiality is a fundamental aspect of the individual enforcement model used in Australian and UK equality law. This has the significant risk of undermining the radical potential of equality law as an ‘overt instrument of cultural transformation’[185] that can be used to transform beliefs and preferences.[186] Confidential conciliation and reliance on non-disclosure clauses in settlement agreements risks relegating equality law to the private sphere, and limits public scrutiny of employers’ behaviour. As Thornton has argued:

While anti-discrimination legislation purports to express public disapprobation of discriminatory acts committed in the public arena, it is nevertheless nervous about public scrutiny of those acts, the wrongfulness of which is contentious. Therefore, violations are treated not as public transgressions in the way that crimes are treated, but as private pecadilloes [sic]. Hence, it has been determined that such matters should be dealt with primarily in a confidential and non-threatening privatised environment; a public hearing is generally available only as a last resort following the failure of conciliation.[187]

The enforcement of equality law demands a more nuanced balance between confidentiality and transparency to better support the individual and systemic aims of equality law and the imperatives of the rule of law. In particular, there is a need to find a better balance between the parties’ (presumed) desire for confidentiality, and providing transparency in legal decision-making. One means of achieving this is to release de-identified data about claims and settlements, with a view to informing parties about their rights and potential outcomes. A more radical push for transparency could involve publicly revealing discriminatory conduct as part of settlement terms, reflecting and building on the growing scrutiny of non-disclosure agreements in the UK context. Regardless, the time has come to shine a brighter light on the enforcement of equality law.

[*] Senior Lecturer, Department of Business Law and Taxation, Monash Business School, Monash University.

[†] Associate Professor, Melbourne Law School, University of Melbourne. Alysia’s contribution to this research was funded by the Australian government through the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (Project No DE170100228). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Government or Australian Research Council.

[1] See, eg, Australian Human Rights Commission, 2017–18 Complaint Statistics (Report, 2018) 2 (‘AHRC Complaint Statistics 2017–18’); Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service, Annual Report and Accounts 2016–17 (Report, 19 July 2017) 14–15 (‘Acas Annual Report 2016–17’).

[2] The research was approved by the Department of Justice (Vic) Human Research Ethics Committee (Project No CF/16/23372) and the Monash University Human Ethics Committee (Project No 8648).

[3] See, eg, AHRC Complaint Statistics 2017–18 (n 1) 2; Acas Annual Report 2016–17 (n 1) 13.

[4] See, eg, Alysia Blackham and Dominique Allen, ‘Resolving Discrimination Claims outside the Courts: Alternative Dispute Resolution in Australia and the United Kingdom’ (2019) 31(3) Australian Journal of Labour Law 253.

[5] Race Relations Act 1968 (UK) ss 14–15. These functions were taken away from its successor and later equality agencies so that they could focus on enforcement.

[6] United Kingdom, Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 3 May 1965, vol 711, col 927 (Sir Frank Soskice) (‘UK Parliamentary Debates (3 May 1965)’).

[7] Race Relations Act 1965 (UK) s 2.

[8] UK Parliamentary Debates (3 May 1965) (n 6) vol 711, col 928 (Sir Frank Soskice).

[9] United Kingdom, Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 23 April 1968, vol 763, col 56 (James Callaghan).

[10] Ibid col 57.

[11] Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 (UK) s 7, inserting Employment Tribunals Act 1996 (UK) s 18A; Employment Tribunals (Early Conciliation: Exemptions and Rules of Procedure) Regulations 2014 (UK) SI 2014/254 (‘UK Early Conciliation Regulations’). Individuals do not need to notify Acas of their intention to make a claim where: another person has complied with the requirement in relation to the same dispute; Acas does not have a duty to conciliate on some or all of the claim; the employer has already contacted Acas; the claim is for unfair dismissal, and the claimant intends to apply for interim relief; or the claim is against the Security Service, Secret Intelligence Service or the Government Communications Headquarters: at reg 3.

[12] Explanatory Notes, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 (UK) 11 [57]–[58].

[13] Acas Annual Report 2016–17 (n 1) 30, 32. The complaint resolution process in Northern Ireland is substantially the same, except that confidential conciliation is provided by the statutory Labour Relations Agency: ‘Conciliation Services’, Labour Relations Agency (Web Page, 15 November 2019) <https://www.lra.org.uk/resolving-problems/escalating-unresolved-issues/conciliation-services>, archived at <https://perma.cc/85RP-A5JN>.

[14] Annemarie Devereux, ‘Human Rights by Agreement? A Case Study of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission’s Use of Conciliation’ (1996) 7(4) Australian Dispute Resolution Journal 280, 282.

[15] Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) ss 22–4, as enacted (‘Cth Racial Discrimination Act’); Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW) s 92, as enacted (‘NSW Anti-Discrimination Act’); Sex Discrimination Act 1975 (SA) s 40(2), as enacted (‘SA Sex Discrimination Act’); Equal Opportunity Act 1977 (Vic) s 39(2), as enacted.

[16] Cth Racial Discrimination Act (n 15) ss 19–20, as enacted.

[17] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 13 February 1975, 286 (Keppel Enderby, Attorney-General).

[18] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 24 March 1981, 856 (Robert Viner).

[19] SA Sex Discrimination Act (n 15) pt VIII div II.

[20] See South Australia, Parliamentary Debates, House of Assembly, 11 June 1975, 3298 (Donald Dunstan) (‘SA Parliamentary Debates (11 June 1975)’).

[21] See South Australia, Parliamentary Debates, House of Assembly, 13 November 1984, 1821–5 (Gregory Crafter).

[22] SA Parliamentary Debates (11 June 1975) (n 20) 3296 (Donald Dunstan).

[23] Victoria, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 11 November 1976, 4078 (Rupert Hamer, Premier) (‘Vic Parliamentary Debates (11 November 1976)’).

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid 4079.

[26] Ibid 4080.

[27] New South Wales, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 23 November 1976, 3343 (Neville Wran).

[28] New South Wales, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Council, 24 November 1976, 3396 (David Landa).

[29] Western Australia, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 20 September 1984, 1550 (Yvonne Henderson).

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Australian Capital Territory, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 17 October 1991, 3894 (Rosemary Follett) (‘ACT Parliamentary Debates (17 October 1991)’).

[34] Ibid.

[35] Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Bill 1991 (ACT) s 77. See also ibid.

[36] ACT Parliamentary Debates (17 October 1991) (n 33) 3894 (Rosemary Follett).

[37] Queensland, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 26 November 1991, 3194 (Dean Wells).

[38] Ibid 3193–7.

[39] Northern Territory, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 1 October 1992, 6529 (Shane Stone).

[40] Ibid 6530.

[41] Tasmania, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Assembly, 3 December 1998, 50 (Judy Jackson).

[42] Ibid 51. However, even this was seen as significantly strengthening the enforcement mechanisms under Commonwealth statutes.

[43] ‘Complaints Made to the Australian Human Rights Commission’, Australian Human Rights Commission (Web Page) <https://www.humanrights.gov.au/quick-guide/12000>, archived at <https://perma.cc/DEV9-VCAW>.