Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

REBECCA NELSON[*]

The ecological condition of many urban waterways in Australia is poor and declining. A key driver for the decline is excess urban stormwater runoff caused by the cumulative effects of urban developments. Inspired by insights from scientific studies of cumulative environmental effects, this article undertakes a traditional legal analysis across five areas of law to explore their potential to address this problem, and pioneers an approach to spatio-legal analysis to understand key gaps in the application of legal mechanisms to Melbourne. Although many legal mechanisms might be used to address sick city streams, and despite significant recent reforms, many lack strong goals and quantitative standards, and the strength of legal controls varies greatly across Melbourne. The Yarra Strategic Plan under the groundbreaking Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 (Vic) presents an opportunity to pilot an improved approach to protecting and restoring city streams in the context of the stormwater impacts of intensifying development.

CONTENTS

Melbourne is the fastest-growing city in Australia, and one of the fastest-growing in the developed world.[1] Population growth occupies the front pages of newspapers and the work of government analysts.[2] Most focus on ensuring that growth is accompanied by adequate social infrastructure, particularly transport,[3] while relatively little popular attention has been devoted to the ways in which increasing development can degrade urban waterways. Yet vast new greenfield estates, large-scale urban renewal projects, and urban infill developments can, cumulatively, significantly affect city streams.[4]

Rivers and creeks form the arteries and veins of metropolitan areas — from large rivers like Melbourne’s Yarra River (Birrarung) to half-forgotten drains alongside urban cycle paths.[5] They are sometimes ‘the [most] significant natural areas remaining in urban landscapes’.[6] Urban waterways support important biodiversity,[7] provide physical and mental health benefits to city dwellers,[8] harbour important heritage and Indigenous and non-Indigenous culture,[9] and provide economic benefits through recreation, water supply, natural water treatment, and increased property values.[10] The cumulative impacts of development can threaten the capacity of city streams to provide these benefits.

Excess stormwater runoff, which is increased by development, is the ‘fundamental driver’ of most of the changes that degrade natural waterways in urbanising areas.[11] Future urban growth and more frequent extreme weather events triggered by climate change will likely increase stormwater and stream degradation.[12] City streams will become even sicker. Increased stormwater runoff is also expected to cause economic losses through increased flash flooding and significant new costs of upgrading drainage infrastructure.[13]

This phenomenon has attracted the recent attention of the Australian Senate[14] and state governments.[15] It lies within local governments’ core legislative obligations to consider the cumulative effects of their decisions on the environment.[16] Nonetheless, no sustained scholarly work has analysed the full range of relevant current regulation in this area. Such an investigation is made particularly timely by the passage of the groundbreaking Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 (Vic) (‘Yarra Act’), which provides scope to implement new and more effective regulatory responses to the cumulative environmental effects of urban stormwater flows.

Using the case study of metropolitan Melbourne, this article explores the complex, layered laws that could and likely should be used to address the cumulative effects of increased stormwater on city streams. It demonstrates that a wider range of legal mechanisms could be used to address excess stormwater runoff than is commonly appreciated, though a brief traditional legal and qualitative analysis suggests important weaknesses in the range of existing legal mechanisms and the ways in which they are presently used. A quantitative spatio-legal analysis that uses maps to display and analyse law — the first time the approach has been used in a major Australian law journal[17] — reveals important gaps in the use of these mechanisms. These gaps leave waterways ecologically vulnerable and invite future economic losses from flooding. Its findings point to opportunities for new approaches using mechanisms under the Yarra Act to better link the longstanding silos[18] of land use and water management and address key weaknesses in current legal approaches. Its findings also speak to current efforts to reform stormwater-related laws in Victoria,[19] across Australia,[20] and internationally.[21]

More broadly, the study addresses a critical problem in environmental and natural resources law — the ways in which law can better address cumulative environmental effects (‘CEEs’). CEEs are the significant aggregate effects of many actions, including spatially and temporally dispersed actions that may be individually minor.[22] CEEs range from climate change,[23] to biodiversity losses caused by clearing land,[24] to the biological accumulation of toxic pollutants.[25] Indeed, leading scientists have suggested ‘planetary boundaries’ that demonstrate a ‘safe operating space’ for aggregate human effects on the environment, beyond which there is a high risk of serious impacts on earth-system functions.[26] Around the world, legal responses to CEEs are considered grossly inadequate, requiring improvements in law, policy and associated guidance.[27] This case study brings a broad legal analysis into dialogue with the scientific literature on CEEs. Alongside the Melbourne case study, this dialogue produces generalised principles for examining legal mechanisms to address CEEs that share the particularly thorny characteristics of the environmental effects of urban development on waterways — namely, widespread and dispersed effects from numerous sources, a low threshold for significant environmental effects, and significant existing effects from historical activities.

Part II of this article sets out background information helpful for identifying, analysing and selecting legal mechanisms for protecting (preventing harm from runoff) and restoring (remediating existing harm from runoff) city streams, understood broadly as including major and minor waterways that appear ‘natural’, as well as highly modified watercourses such as open drainage channels.[28] First, it briefly outlines the scientific basis for development adversely affecting urban waterways. It then outlines how these effects can be characterised as CEEs, and summarises regulatory challenges related to addressing CEEs, leading to generalised principles for investigating relevant legal mechanisms. Finally, it outlines how spatial analysis can help, and briefly describes the spatio-legal methods pioneered in this article. Part III explores the broad concepts, values and goals that the law adopts for waterways, which take shape through legal definitions of waterways and processes for setting broad visions and detailed targets for them. These are the figurative legal destinations to which legal mechanisms to protect and restore the health of waterways advance. Part IV uses the lens of CEEs to examine these specific legal mechanisms relevant to the health of urban waterways in the context of stormwater flows. These mechanisms span a broad range of laws, here categorised for convenience into five areas: public (Crown) land law, including that related to protected areas; planning laws; building laws; environmental laws; and water laws. In relation to each area, the article first explores the current and potential future operation of relevant mechanisms doctrinally and qualitatively, by reference to specific instances of their use. Part V then examines, using a quantitative and spatial approach, the extent to which these mechanisms protect Melbourne’s city streams, and the locations of ‘hotspots’ that are comparatively legally vulnerable to producing increased stormwater flows, and therefore adverse CEEs. Part VI concludes by summarising key opportunities for enhancing and extending the legal mechanisms reviewed to protect and restore sick city streams, both across metropolitan Melbourne in general and also in the context of the Yarra Act. Finally, Part VII concludes, reflecting on larger lessons for considering legal mechanisms to address CEEs.

Compared to ‘natural’ streams, city streams have modified flow regimes, reduced water quality, physical changes, reduced or absent riparian vegetation, and reduced in-stream flora and fauna: they are sick, afflicted by ‘urban stream syndrome’.[29] Science and government policy recognise that a key driver for these changes is increased stormwater runoff from impervious urban surfaces, such as roofs, carparks and roads,[30] which is piped directly to streams, and which traditional stormwater management arrangements have addressed poorly.[31] Urban growth increases impervious surfaces, which are expected to rise to almost 90% in some urban Australian municipalities.[32] Modelling suggests that impervious surfaces in Melbourne in 2051 will be 43% greater than in 2011 due to population growth.[33] A useful metric describing this phenomenon is ‘directly connected imperviousness’ (‘DCI’).[34] Conventional drainage systems rapidly convey runoff from these surfaces through pipes directly to streams, rather than slowly through natural infiltration processes.[35] This increases pollution, changes flow rates, waterway structures and features, and ultimately changes stream habitat, biodiversity and associated ecological processes, such as nutrient cycling and connections between channels and floodplains.[36] Even low DCI levels of 1–5% of the catchment surface can alter the hydrology of receiving streams, resulting in the loss of many in-stream species.[37] As well as affecting streams directly, excess runoff can also discourage or inhibit waterway restoration.[38] Large peak flows can prevent effective revegetation[39] and have encouraged drainage managers to line waterways with concrete — at great cost and with drastic ecological consequences.[40] Fears about flooding and insufficient information about the ecological benefits of reducing high flows[41] can prevent efforts to restore existing channelised waterways.

Several approaches are used to prevent and treat ‘urban stream syndrome’. One approach is to build infrastructure (known as stormwater control measures (‘SCMs’)) to capture stormwater before it reaches urban waterways.[42] This ‘disconnects’ impervious surfaces from streams, reducing DCI.[43] The goal is to maintain or return the water balance to a pre-development or lesser-developed state.[44] SCMs, like rainwater tanks and raingardens,[45] can be used at the land parcel scale, near the source of the stormwater; larger SCMs, like constructed wetlands and other forms of detention basins, swales and infiltration trenches,[46] can be used at the neighbourhood scale. Another approach is to control the construction of impervious surfaces, either by constraining development or by constructing surfaces that allow infiltration, such as pervious driveways and carparks.[47] These measures focus on hydrologic processes and have implicit water quality benefits.[48] Another measure is to increase the direct use of stormwater (for example, to irrigate green spaces), though this is considered a desirable adjunct to SCMs, rather than sufficient in itself,[49] and is not discussed further here.

To date, investments in protecting city streams have been ad hoc and opportunistic, through a combination of large-scale ‘end-of-pipe’ stormwater retention systems and household-scale infrastructure incentives.[50] Significant public investment (over $120 million in Victoria[51] and at least twice this amount for federally funded projects[52]) has not yet notably improved waterway health.[53] This warrants investigating the potential for a more comprehensive response, based in law or policy, to prevent and treat sick city streams. Accordingly, this regulatory investigation focuses on both preventative and remedial legal mechanisms that may be used to control the development of DCI and build SCMs to protect and allow the restoration of urban streams.

This article applies a novel theoretical and methodological lens to analysing potential legal responses to sick city streams, inspired by the cumulative nature of the environmental problem, and spatial methods more common in scientific literature.

The adverse ecological effect of urban stormwater flows is a CEE.[54] Recognising this characteristic activates principles for regulating these effects that guide an investigation of laws used to respond to CEEs. These principles help address the questions: what can the law do to protect and treat sick city streams, as an example of cumulative environmental harm; which laws can do these things; and what should they consider? Because diverse, individually minor activities may collectively have significant impacts, a regulatory response to CEEs should consider (if not control) all sources of adverse impact, regardless of their type, frequency or individual magnitude (noting that regulating numerous and diverse activities involves challenges well known in the commentary relating to ‘diffuse’ sources of water pollution).[55] For example, a large tourist carpark on Crown land, a large private residential development’s carpark, and a small residential carpark all have potential to generate stormwater CEEs. A key point of analysis is therefore the degree to which an activity is included or excluded from regulatory controls because it has a different nature, occurs on different land tenure, or has a different magnitude of effect. Legal inquiries must traverse complex urban regulatory landscapes, since a huge array of legal mechanisms and regulatory institutions control diverse relevant activities.

Environmental science shows that numerous minor effects may combine in complex ways, with important regulatory implications. First, they may aggregate to create an ecological ‘tipping point’, beyond which harm increases non-linearly.[56] That is, rather than simply adding together (eg A+B), they may accumulate synergistically (eg A*B) beyond a certain point.[57] In the case of stormwater flows, important ecological thresholds arise even where DCI percentages (in terms of catchment coverage) are very low.[58] A regulatory response to CEEs should therefore consider (if not control) potential adverse effects even at relatively low aggregate levels of development, and recognise that highly developed urban catchments may have long ago exceeded thresholds of significant ecological harm. Legal interventions should, accordingly, be based on clearly specified desired levels of ecological health (ie goals) that can, in turn, influence how proposed developments are considered. High levels of existing ecological degradation also raise legal, equitable and political issues about whether existing developments should attract new regulatory controls — or perhaps non-mandatory measures, such as incentives — to address their ongoing effects.

Ecological effects can be adverse (as described above), accumulating in harmful ways, or beneficial.[59] A beneficial effect may counteract an adverse effect to some degree (eg A–B).[60] Accordingly, if an effect cannot be reduced sufficiently in absolute terms, beneficial action undertaken elsewhere may mitigate or ‘offset’ harms to reduce net adverse ecological effects.[61] In the stormwater context, a landholder with insufficient space to install an SCM to ‘disconnect’ unavoidable impervious surfaces could pay a different landholder with more space to install an SCM to reduce the rapid discharge of stormwater to an urban stream. Laws may encourage or require SCMs, or perhaps remove barriers to them, to facilitate mitigating the adverse stormwater effects of one or multiple past or present developments.

The CEE literature adopts a binary categorisation of tools for addressing CEEs as ‘regional’ or ‘project level’,[62] which is useful to adopt here. Much of the environmental literature and practitioner experience focuses on how CEEs are considered in project-level environmental impact assessment.[63] This type of assessment involves identifying the possible environmental risks of a proposed project — ideally including an analysis of its cumulative effects in the context of other past, present and reasonably foreseeable future projects[64] — to inform decisions about whether the proposal should proceed, and under what conditions.[65] Although individually minor developments (such as stormwater effects of a single development) fall below regulatory thresholds of a significant environmental effect that triggers a requirement to undertake an environmental impact assessment,[66] the concept of considering CEEs at the level of an individual development is relevant to other regulatory approval processes, such as those that apply to the grant of a planning permit. CEEs can also be assessed and controlled at the regional[67] or watershed[68] scale, with the focus of the literature being regional ‘strategic environmental assessments’ under environmental laws, which are ideally linked to project-level assessments.[69] Though these strategic assessments are sometimes applied to urban development, they have apparently overlooked the environmental effects of increased stormwater flows.[70] However, the concept of strategically influencing multiple developments across a region is also relevant outside environmental impact assessment laws as a way to control CEEs.

This article adopts the binary categorisation of project- and regional-level tools in the following way: regional mechanisms apply across more than one landholding to all or certain types of developments within a geographically defined area (for example, a catchment or a local government area (‘LGA’)). They may set environmental goals and management strategies, or determine the kinds of development that must be assessed and approved at the project level. Project-level mechanisms apply to single developments or landholdings. They may determine whether and how a project may go ahead (analogous to environmental impact assessment) or continue (in the case of an existing activity), or how a landholding is to be managed.

In summary, adopting scientific understanding and reasoning about CEEs in the legal domain reveals the following generalised principles for examining legal mechanisms to address CEEs that involve similar characteristics to those of excess urban stormwater flows. An examination should involve investigating a wide range of legal mechanisms that: (a) operate at the regional or project levels, and consider links between levels, to (b) comprehensively consider numerous diverse ecologically relevant effects, regardless of whether they are individually significant, and (c) consider effects at low levels of overall development, recognising the potential for significant ecological harms at these low levels or at particular thresholds; (d) provide for ecologically positive interventions, including removing barriers to beneficial action; and (e) use clear goals and baselines, recognising existing effects and providing for regulatory mandates or incentives, as appropriate. Part IV applies these principles to investigate legal mechanisms that operate in metropolitan Melbourne to protect urban waterways by controlling development that would create impervious surfaces and facilitating construction of SCMs. While this analysis is restricted to legal mechanisms as they appear on paper, by identifying specific mechanisms it opens the way for empirical research on their implementation.

Our legal system often divides resources among silos — water and land, public and private — drawing legal distinctions that are unrelated to environmental effects.[71] Where diverse activities that produce CEEs span multiple silos, they can, in the aggregate, trigger a very wide range of statutes and legal mechanisms (outlined in Part IV). While some laws may apply generally, others are ‘legal norms, rights and duties related to identifiable locations’.[72] Information about these can be understood as layers of ‘spatio-legal data’.[73] Gaps in these layers may mean the relevant environmental effects are not comprehensively addressed using legal mechanisms. Using traditional legal analysis alone, it is difficult to appreciate these gaps and their significance, amid such spatially complex and layered legal controls.[74] The novel spatio-legal approach used in this article maps and analyses these layers and exposes important gaps.

Spatial analysis is a common and well-recognised scientific approach to assessing CEEs,[75] and has recently been used to evaluate the physical infrastructure aspects of stormwater management in Melbourne.[76] Spatial analysis usually involves using geographic information systems software to map proposed and existing sources of environmental stress on valued environments,[77] sometimes together with relevant social and political characteristics.[78] While the legal implications of geospatial information have attracted significant legal interest,[79] legal scholars (particularly in the environmental field) have also been urged to use spatial analysis,[80] although few have done so. Spatial analyses of environmental policies undertaken in other disciplines are generally limited in their legal depth.[81] Existing spatio-legal work in the environmental sphere has tended to use data on land ownership and administrative boundaries,[82] the distribution of statutory conservation areas like national parks and other protected areas,[83] and the spatial distribution of US water policies compared to pollution hotspots.[84]

This is not to say that law (including environmental law) and geography do not meet. On the contrary, the quarter-century-old field[85] of legal geography examines ‘the presence and absence of spatialities in legal practice and of law’s traces and effects embedded within places’.[86] However, its methods are critical and qualitative, tending not to use geographic information systems. Indeed, legal geography emphasises alternatives to traditional positivist scientific ontology, epistemology and methodology.[87] In the wider legal field, legal scholars have used geographic information systems (albeit uncommonly) in diverse ways to examine electoral districting practices,[88] education law,[89] criminology,[90] human rights,[91] and law and history.[92]

Spatial analysis of legal instruments in the environmental field — at a detailed legal level and aggregating layers of legal mechanisms — illuminates the law in ways that would otherwise not be possible. This article uses geographic information systems to demonstrate how diverse legal mechanisms that are relevant to stormwater flows apply in the spatial context of jurisdictional boundaries and the spatially diverse conditions of city streams. This spatio-legal approach reveals gaps in current legal protections, the legal actors with jurisdiction to address those gaps, and — in light of varying ecological conditions — priority areas for further action. Considering overlaps between multiple layers of planning, building, environmental, and water laws, in combination with complicated systems of land tenure and policy-based initiatives, also reveals elements that would benefit from coordination. In particular, hydrological connections mean that improving the ecological condition of a downstream reach of an urban waterway requires stormwater controls to be applied by multiple upstream jurisdictions, potentially using legal mechanisms spanning multiple legal ‘layer[s]’ in order to comprehensively control multiple development types.[93]

Melbourne’s city streams are ecologically sick.[94] On recent data, 56% of the stream length in the six basins over which metropolitan Melbourne extends is in poor or very poor condition[95] (generally measured relative to its pre-European state[96]). Only 5% is in good condition, and only 0.07% is in excellent condition.[97] This sobering data (reflecting stormwater effects of existing DCI) invite an exploration of how law and policy conceive of urban waterways in space and in terms of their values, how law sets ecological goals for these waterways (to which stormwater-related controls should be directed), and how powerfully legal mechanisms are connected to these goals. Recent and emerging changes hold promise for clearer, more quantitative ecological goals with stronger legal weight to guide improved legal responses to these CEEs.

Historically, Australian laws conceived of rivers narrowly as permanent streams, flowing in defined banks, which had value for agriculture and transport.[98] They did not typically encompass intermittent and ephemeral streams[99] or recognise or protect ecological values.[100] By contrast, the conception of waterways in current Victorian law extends to heavily modified waterways[101] and seeks to protect their ecological values.[102] For around two decades, catchment and water laws have provided for statutory water strategies (regional catchment strategies and regional waterway strategies)[103] that encompass ecological values, natural and modified waterways, and connections between water, waterways and floodplain land in general.[104] The strategies have arguably struggled to protect the ecological health of urban waterways for reasons that include their status as mere ‘considerations’ for public land managers,[105] and the fact that their function of setting goals and values for catchments and water ecosystems[106] has sometimes been undertaken in ways that are inconsistent and non-transparent.[107] Allied statutory[108] and non-statutory water-related strategies usefully highlight connections between land use and water, but adopt relatively vague goals such as ‘[h]ealthy and valued waterways and waterbodies’.[109]

A new 50-year regional waterway strategy (‘Healthy Waterways Strategy’) for Melbourne, finalised in November 2018, decisively clarifies ecological goals, particularly in relation to stormwater. While it adopts broad ‘key values’,[110] it also sets supporting ‘waterway conditions’, including ‘[s]tormwater condition[s]’,[111] maps ‘[p]riority areas for enhanced stormwater management’,[112] and sets measurable long-term ‘[w]aterway condition targets’ and short-term ‘performance objectives’.[113] Stormwater conditions and objectives are quantified based on current and targeted DCI.[114] Meeting important CEE principles,[115] these provisions recognise existing degradation as well as low, scientifically supported thresholds of ecological harm (<0.5% DCI being required for ‘Very High’ conditions indicating ‘minimal or no threat from stormwater’, to >10% for ‘Very Low’ conditions indicating severe impacts on stream health).[116] Quantifying the desired degree of change in stormwater conditions is vital to allow decision-makers to assess an appropriate combination of legal mechanisms[117] for achieving them. Quantified goals also remove discretion that can make decision-makers vulnerable to the inappropriate influence of powerful interest groups.[118] The challenge remains ensuring that these goals have strong legal connections to the legal mechanisms that can achieve them, to avoid ineffective or ad hoc use of these mechanisms.

The Yarra Act presents significant promise for connecting stormwater goals with legal mechanisms. It also significantly expands Victoria’s statutory conceptualisation of the values of waterways — though its relatively narrow spatial conceptualisation of the river (relative to regional catchment strategies) may pose problems. Uniquely among Victorian legislation, the Act seeks to protect the river as ‘one living and integrated natural entity’,[119] informed by traditional Wurundjeri views. Its ‘Yarra protection principles’ broadly embrace ecological values (biodiversity, ecological integrity) and wide-ranging social and cultural values[120] (although they use very broad qualitative language[121] and lack a clear hierarchy,[122] unlike some broadly analogous water statutes).[123] A statutory ‘long-term community vision’[124] details these values for four river reaches,[125] using similarly broad language.[126] More specific environmental target-setting in relation to Yarra River land[127] is the job of ‘performance objectives’ in a ‘Yarra Strategic Plan’ (‘YSP’), discussed in Part VI, a draft of which was released in January 2020.[128] The new Healthy Waterways Strategy provides a clear set of quantitative stormwater-related goals that the YSP could usefully adopt. Conversely, the YSP provides a legally binding framework to translate these goals into regional- and project-level mechanisms for achieving them.[129]

The YSP’s impact on stormwater will be influenced by its spatial limits. Two key spatial delineations are associated with the Yarra River: first and foremost, ‘Yarra River land’,[130] and second, ‘[l]and to which [the] Yarra Strategic Plan [applies]’.[131] ‘Yarra River land’ refers to a declared area of public land adjacent to the Yarra River, or any part of which is within 500 metres of one of its banks.[132] The YSP will apply to this area and a larger, as yet undeclared area that includes public and private land within one kilometre of the riverbank and potentially land in the adjacent municipalities.[133] However, since the potential YSP area does not cover all of the Yarra catchment,[134] outer catchment developments excluded from its potential stormwater controls may compromise its ecological goals.

The parlous state of Melbourne’s waterways raises the question: do we lack laws to address the ecological health of city streams?[135] If not, are existing laws fundamentally flawed? Or unused? This part begins to answer the first two of these questions in light of the general principles informed by CEE concepts set out in Part II(B)(1). It examines key state and local[136] legal mechanisms that operate at both the project and regional level to protect urban waterways by controlling development that would create impervious surfaces (regardless of whether this protection is sought intentionally or is an incidental effect of the mechanism), and restoring urban waterways through SCM construction (ie both preventing adverse effects in absolute terms and providing for positive interventions and mitigating adverse effects). It also examines legal mechanisms for indirectly controlling CEEs by managing Crown land and incentivising desirable land management practices.[137] This examination discusses the strengths and weaknesses of each mechanism based on a qualitative examination of the statutory framework for, and examples of, each mechanism, having regard to CEE concepts. It identifies ways to address weaknesses through improving either the overarching statutory frameworks, or the individual legal instruments within these frameworks that apply to particular areas. The analysis extends recent consultations relating to stormwater reforms undertaken by environmental advocates and government[138] and Victoria’s late-2018 stormwater planning reforms,[139] and builds on existing work focusing on several legal aspects of water quality and water quantity impacts of stormwater.[140] Part V then uses a spatial analysis to understand the extent to which key regional mechanisms apply in metropolitan Melbourne.

Crown ownership of land provides a regional-level approach[141] to restricting the development of impermeable surfaces, constraining additional stormwater flows. This effect is incidental rather than intentional: statute restricts development in public protected areas.[142] Even on other forms of Crown land, development seems less likely to occur at a large, profit-motivated scale than on private land. Management of Crown land by a relatively small group of public entities is more easily guided and influenced than that of numerous private landowners. Though developments on Crown land are often excluded from planning law-based stormwater controls (discussed below), Crown land provides unique scope for ecologically positive interventions — constructing SCMs to mitigate the effects of existing or future developments — through direct government action and incentive-based measures. This opportunity arises particularly because historically, riparian land was reserved so that it could not be privately owned.[143]

At one end of the Crown land spectrum lie urban[144] and remote public[145] protected areas, managed under conservation-oriented legislative schemes. These do not explicitly seek to prevent ‘urban stream syndrome’, but do so incidentally through development controls, to varying degrees. ‘[R]eference areas’ and certain zones of national parks and state parks are to be preserved in their ‘natural state as far as is possible’ or for water supply purposes.[146] Some development is permitted in other areas. Leased areas of national parks and state parks may host tourism-related buildings, but are obliged to protect water resources.[147] In heritage river areas, few activities are prohibited — typically waterway diversions and timber harvesting[148] — with no prohibition on the construction of hard surfaces.[149] However, protected areas with looser controls on development could potentially host SCMs where consistent with their statutory conservation objectives.

‘Reserved’ Crown land is dedicated to a specific public purpose.[150] It may not be sold, leased or licensed for other purposes.[151] Its purpose may be explicitly to protect waterways[152] or a conservation-related purpose that inherently controls development.[153] Some purposes explicitly contemplate roads, carparks, or buildings, from preschools to prisons.[154] Unfortunately, public roads and carparks can contribute as many impermeable surfaces as privately owned land,[155] and public development may even counteract private efforts to address adverse damaging stormwater flows.[156] However, regulations for reserved Crown land offer opportunities to protect and manage Crown reserves and regulate activities on them[157] (though no environment-focused regulations currently exist).[158] Crown reserve management agreements between the State and a land manager[159] also have this potential. In both cases, a requirement to implement best practice stormwater management would mirror requirements of lessees of unreserved Crown land (see below). Policy guidance to managers could encourage installing SCMs (with costs potentially offset by beneficiaries),[160] much as ‘Statement[s] of Obligations’ impose positive environmental obligations on water authorities.[161] The Yarra Act imposes new obligations on public land managers to not act inconsistently with (and have regard to) the YSP,[162] which may include stormwater components.[163]

Examining all types of ‘unreserved’ Crown land is beyond the scope of this article. However, three potential vehicles for protecting urban waterways are particularly notable. First, ‘[t]o manage leased Crown land in an ecologically sustainable manner’,[164] Crown leasing policy requires proponents to ‘implement best-practice stormwater management’.[165] Defining this currently undefined phrase using quantitative standards used in planning laws[166] may address concerns that governments manage public land with less environmental rigour than is required on private land.[167] Second, incentive-based ‘riparian management licen[sing]’ arrangements over unreserved Crown water frontages grant reduced rental fees to licensees in exchange for management practices such as fencing out stock,[168] which benefit water quality. This fee reduction incentive could be extended to leasing Crown land more generally, where SCMs are used or where land management practices provide a net stormwater benefit. Finally, the Crown could use its power to vary or cancel licences in the public interest[169] to construct SCMs such as large detention basins[170] to counter the effects of existing or future development. This would avoid problems of politics and equity that arise if requirements for parcel-scale SCMs were imposed retrospectively on private landowners.

Finally, Commonwealth land includes significant DCI in airports on near-stream land in western Melbourne, and may create future DCI through ‘urban renewal’ on its land.[171] This presents a risk to waterway health, since state environmental laws (which deal primarily with water quality) apply to it,[172] but planning laws (which currently provide the most significant protections for urban waterways from stormwater flows) do not.[173] Some management arrangements for significant Commonwealth land close to Melbourne rivers incorporate relatively well-established SCMs (notably the Essendon Airport redevelopment),[174] while in other cases, management arrangements are more recent and still evolving (notably Melbourne Airport).[175]

In sum, Crown land presents significant regional-scale protection from stormwater CEEs through development constraints on public protected land, and opportunities for addressing CEEs through regulations or policy guidance for Crown reserves, and leasing and licensing policy guidance for unreserved Crown land. Unreserved Crown land, and Crown reserves with environment-related purposes, offer promise for strategically constructing SCMs, whereas Commonwealth land presents an ongoing legal dilemma that is perhaps best addressed through negotiation between governments in respect of large developments.

Planning laws, which control how land may be used and developed, provide clear vehicles for controlling the impacts of new (but not existing)[176] public and private[177] urban developments on waterways. Recent Victorian stormwater policy reform, which aims to ecologically revive sick city streams,[178] has focused on planning laws,[179] most recently through statewide statutory stormwater policies introduced in October 2018 (‘Amendment VC154’).[180]

The central regional-level planning law mechanism is a ‘planning scheme’, usually made by a municipal council to guide land use and development in its municipality.[181] Planning schemes are structured around standard provisions for zones and overlays, which schedules can vary.[182] Zones prohibit certain land uses or developments or allow them with or without a planning permit.[183] Overlays apply to certain land with special characteristics, including special environmental characteristics, and may apply additional requirements to planning permit applications.[184]

Project-level planning permits regulate particular uses and developments of individual parcels of land. A decision-maker must consider regional mechanisms and generally applicable statutory objectives and considerations in determining a permit application.[185] A planning scheme may also require an application to be given to a referral authority for comment or conditions.[186] Stormwater concerns may manifest as permit conditions (analogous to ‘project-level’ assessment and management in the CEE literature), potentially after referral to a water authority, and separate agreements between local governments and landowners.

The ‘urban growth boundary’ limits development outside a rough ring around Melbourne in order to permanently protect ‘the values of non-urban land’.[187] The boundary is implemented through planning schemes that apply to the metropolitan fringe, but can only be changed through ratification by Parliament of an amendment.[188] Although it does not directly prohibit the construction of impermeable surfaces,[189] it protects urban waterways incidentally by generally prohibiting further subdivision of land and the associated increased DCI.[190]

Another relatively coarse planning control tool that incidentally protects urban waterways is land zoning for public purposes (‘public use zones’),[191] which covers certain types of public land.[192] Two of the three public use zones specifically foresee primarily open space-based (ie permeable) land uses,[193] while contemplating minor developments,[194] while the third contemplates significant development — for example, for education or local government buildings.[195] Although Amendment VC154 (discussed below) extends stormwater requirements to important public use zones,[196] its impact may be limited because, consistent with State policy, public managers need rarely obtain a development planning permit (which is required to trigger a zone’s stormwater requirements).[197] This mirrors the unevenness in stormwater requirements that exists between Crown land managers and private lessees of Crown land (discussed above).[198] Public land zoning could better protect city streams by continuing to exempt only developments that meet stormwater standards (for example, on-site runoff retention or an equivalent offset) from a permit requirement. The same approach could apply to public land in other zones, such as roads, which are often in ‘regular’ zones, yet constitute 30–70% of a catchment’s impervious surfaces.[199] Empirical evidence questioning the environmental performance of Victoria’s local governments[200] warrants increased scrutiny of public land use.

Within the urban growth boundary, greenfield (typically outer metropolitan) and urban renewal (typically inner metropolitan) areas are sites of intense development.[201] Specific planning mechanisms for these areas offer scope to improve stormwater management. Precinct structure plans manage the transition of non-urban greenfields into urban land,[202] and planning permits granted within their areas ‘must be generally in accordance with the [applicable] precinct structure plan’.[203] Urban renewal frameworks guide the redevelopment of urban renewal areas.[204] Stormwater requirements in precinct structure plans commonly require runoff to meet or exceed the performance objectives of the best practice environmental management standards for stormwater (‘BPEM’),[205] or directly set requirements that vary widely — from requiring individual dwellings to retain stormwater on-site,[206] to requiring development as a whole to ‘aim to maintain existing flow regimes ... at the pre-development level’,[207] or ‘as close as possible’ or practical thereto, either overall[208] or in conservation areas.[209] Some precinct structure plans are silent on stormwater quantity or quantity targets,[210] or describe qualitative goals of ‘ensuring waterway health’.[211] Precinct structure plans also plan the location of SCMs[212] in accordance with applicable development services schemes.[213]

By contrast, the few currently available urban renewal frameworks show relatively little detailed attention to, or aspirations for, stormwater flows. One merely notes the presence of ‘significant waterways’,[214] and notes a ‘key principle’ of ‘[e]nvironmental sustainability and integrated water management’.[215] Another adopts integrated water management as the driver for a ‘distinctive [urban] identity’, lists a variety of possible SCMs, and includes a general goal of reducing runoff, but no quantitative goals.[216]

A more recent, higher-level approach is a declaration by the Governor in Council of an area to be a distinctive area or landscape, which allows environmentally and culturally significant areas that are under threat from some form of land use change to be protected by a state-level planning policy.[217] At the time of writing, no distinctive areas had been declared in the Melbourne metropolitan region, but one declared in an adjacent rural LGA specifically sought to address the cumulative impacts of development on natural resources.[218]

Planning schemes have traditionally dealt with environment- and water-related matters in special overlays related to flood risks and land with special environmental characteristics.[219] Though their purposes often relate to waterway health[220] (and therefore for present purposes they are deemed to have a protective effect), in practice, flood overlays focus on controlling flood risks to development rather than risks to waterways posed by development.[221] They do not directly seek to address DCI as a risk to city streams.[222]

Environmental overlays, which deal with specific environmental values such as significant vegetation or risks such as erosion,[223] may incidentally protect urban waterways where they require a permit applicant to prepare reports relating to waterway health.[224] Although the standard overlay provisions at best contain only broad policy statements about protecting rivers,[225] they require a decision-maker to consider more specific stormwater policies, for example, the State Environment Protection Policy (Waters of Victoria)[226] (discussed below) and the State Planning Policy Framework.[227]

In the Yarra Ranges, an environmental overlay supported a reputedly world-first stormwater mechanism[228] aiming to ‘return the ecological function and health of the Little Stringybark Creek to a level consistent with a natural stream’.[229] An initial $3 million ‘reverse uniform price auction’ paid landowners an average of 90% of the cost of installing a ‘“stormwater disconnection” [system]’ (such as rainwater tanks and raingarden infiltration systems),[230] achieving benefits more cheaply than on public land.[231] To maintain these benefits,[232] a new Environmental Significance Overlay[233] requires any building or work that creates an impervious surface of 10 m2 or more to include an appropriately sized stormwater treatment system (eg rainwater tank, raingarden, or permeable pavement).[234] Preliminary effects of the mechanism on the waterway are positive,[235] with general acceptance by the community and planners.[236] This experience suggests similar mechanisms may be worth investigating, at least in catchments with similar hydraulic,[237] physical[238] and socio-economic[239] characteristics to Little Stringybark Creek, or otherwise considering modifications to reduce costs for householders.[240]

Some local governments have introduced specific stormwater clauses into their planning schemes’ ‘Local Planning Policy Frameworks’. The City of Melbourne has adopted a Stormwater Management (Water Sensitive Urban Design) Policy, which applies to all new buildings (including single dwellings), significant extensions to existing buildings, and commercial subdivisions.[241] It recognises the importance of reducing stormwater runoff and minimising peak flows using SCMs, including ‘infrastructure upgrades, streetscape layout changes, piping reconfigurations, storage tanks, and the use of different paving’.[242] However, its quantitative standards and technical modelling requirements apply only to water quality.[243] A qualitative goal to ‘reduce the flow of water discharged to waterways’[244] accompanies a decision guideline as to ‘[w]hether the proposal will significantly add to the stormwater discharge ... entering the drainage system’,[245] as determined using software for the purposes of a ‘Water Sensitive Urban Design Response’ that must accompany a permit application.[246]

Several other local planning policies adopt similar approaches: for example, by generally applying qualitative requirements to reduce stormwater flows, but requiring a site management plan only for steep land[247] or large sites,[248] though some require stormwater treatment measures and a written stormwater design response to all new buildings, extensions of greater than 50 m2 in floor area, and commercial subdivisions.[249] Some impose levies on new impervious areas above a threshold to offset the cost of upgrading drainage works to accommodate new stormwater flows.[250] While these local policies are positive, they create inconsistencies that are perceived by developers as confusing and inequitable[251] — a key driver for the recent stormwater planning changes discussed below.[252]

The Planning and Environment Act 1987 (Vic) (‘Planning and Environment Act’) and the State-standard Victoria Planning Provisions contain general decision guidelines that apply to planning permit applications.[253] Under Amendment VC154, a decision-maker considering a planning permit application must consider new statewide stormwater provisions ‘as appropriate’.[254] To help protect and restore catchments and water bodies, strategies include to ‘[u]ndertake measures to minimise the quantity and retard the flow of stormwater from developed areas’ and ‘preserv[e] ... floodplain or other land for wetlands and retention basins’,[255] and ‘[m]inimis[e] stormwater ... impacts’ through ‘a mix of on-site measures and developer contributions at a scale that will provide greatest net community benefit’.[256] While these broad new statements sound promising, the 20-year-old technical guidelines that support them (the BPEM)[257] have proven ineffective. The current BPEM design and implementation guidelines for SCMs are considered to ‘set far narrower and lower stormwater capture, treatment and reuse targets than is likely required to protect urban streams’.[258] More generally, the BPEM adopts a quantified flow objective of maintaining stormwater discharges at pre-urbanisation levels for a defined flood size,[259] which recent advice to the State government claims is ‘rarely applied in practice’.[260] This poor implementation is unsurprising given that the objective is drafted as a generic objective, or one that is applicable to ‘[s]trategic catchment planning’ or the design of retarding basins,[261] and therefore not clearly applicable to individual developments. Without a clear, mandatory quantitative outcome requirement, environmental stormwater objectives can be traded off against other planning objectives, and this appears to occur in the context of urban waterways.[262]

Until recently, new DCI has been managed through controlling a key contributor: residential subdivisions and apartment developments.[263] A new cl 53.18 introduced by Amendment VC154 significantly extends these requirements, aiming to protect the ecological values of urban waterways from stormwater effects.[264] Clause 53.18 applies to many types of subdivisions, most notably subdivisions in commercial, industrial and many public use zones, and applications to construct a building or carry out works over more than 50 m2.[265] Important exclusions include buildings or works associated with one dwelling on a lot, works in a road zone, house extensions in a residential zone, and applications in the Urban Growth Zone.[266] A permit applicant must submit details of an urban stormwater management system to the satisfaction of the relevant drainage authority.[267] In addition to requiring that the subdivision meet the BPEM’s performance objectives,[268] which are ambiguous as to stormwater flows (as discussed above), a system must also ‘ensure that flows downstream of the subdivision site are restricted to pre-development levels unless increased flows are approved by the relevant drainage authority and there are no detrimental downstream impacts’.[269] The analogous provisions for apartment developments refer to the BPEM objectives, though more tentatively as design elements that ‘should’ be met.[270] Both refer to developers entering agreements to offset their stormwater impacts off-site,[271] presumably where on-site capacity to manage stormwater is limited.

Although cl 53.18 laudably addresses serious and long-noted gaps in controls on industrial and commercial developments,[272] it has clear weaknesses and carries some uncertainty. It is unclear how ‘no detrimental downstream impacts’[273] will be measured and how the BPEM standard will evolve. Continued exclusions (eg single dwellings, roads, residential house extensions)[274] mirror the classic CEE problem of focusing only on individually significant activities.[275] One way to capture these uncontrolled risks would be to introduce a planning permit trigger related to the risk that developments pose to urban waterways. Such an approach would arguably comply with current policy aims to ensure permit triggers do not proliferate[276] through ‘deemed-to-satisfy’ solutions that avoid subjecting homeowners to, for example, onerous design and approval processes.[277] Introducing a new permit requirement at smaller scales and in a way that is more targeted to catchment circumstances — for example, by using a planning overlay (as in the Little Stringybark Creek example) — may be more achievable in the short term.

Section 173 of the Planning and Environment Act allows a council (either individually or jointly with another person or body) to enter into an agreement with a landowner in its municipal area.[278] The agreement may prohibit, restrict or regulate the use or development of the land, or the conditions under which it may be used or developed, including to advance objectives[279] that include protecting city streams as natural resources that maintain ‘ecological processes and genetic diversity’, and securing a pleasant recreational environment.[280]

Section 173 agreements are very common and increasing in use,[281] and may contemplate multi-million-dollar developer contributions to counter the effects of development both on- and off-site.[282] Their potential breadth provides scope for innovative approaches to protecting and restoring city streams, including controlling stormwater CEEs.[283] Section 173 agreements may relate to both the development site and also other land: for example, adjacent or proximate riparian land.[284] Common practices requiring developers to provide off-site carparking or revegetation[285] could similarly apply to requiring a developer to construct stormwater-related works along an adjacent stream.[286] The agreements benefit from strong compliance and enforcement provisions: a landowner may be required to pay a bond or give a guarantee in relation to obligations under the agreement,[287] non-compliance with which is an offence[288] that may be scrutinised by authorised persons entering the property.[289] A template agreement[290] containing ‘default’ provisions in relation to urban waterways could reduce drafting and negotiating costs and time.

In a general sense, building laws apply even more broadly than planning laws, since standards apply to all building work at the project level (regardless of whether a planning permit is required),[291] including building work by public authorities.[292] However, permeability standards for buildings are neither ambitious nor broadly applicable: they require only a minimum 20% site permeability for an allotment, and apply only to single residential and associated dwellings.[293] This permits developments that are not caught by planning requirements to increase stormwater flows very significantly, considering the low thresholds of 1–5% of catchment coverage that result in waterway degradation.[294] Further, although new single dwellings must include either a rainwater tank or solar hot water system,[295] the take-up of the former is relatively low and difficult to forecast.[296] Without more, building requirements in relation to permeability and water tanks are insufficient to maintain or improve waterway health.[297] Recent advice to government recommends future (and implicitly, longer term) changes to the Building Regulations 2018 (Vic) and plumbing controls to ensure ‘consistent stormwater requirements are applied to all development types’.[298]

Special arrangements apply to buildings owned by the Crown, and to roads. The former receive special attention via a provision for ministerial guidelines to ‘promote better building standards’.[299] On the other hand, road authorities — for example, VicRoads, a municipal council, or a statutory corporation[300] — determine the standards to which they design and construct roads.[301] National guidelines adopted by VicRoads deal with stormwater issues in a predominantly qualitative way, and with an overriding emphasis on water quality rather than robust quantitative standards for reducing conventionally drained stormwater.[302] Though VicRoads has not elected to apply more rigorous design standards to itself in relation to stormwater flows,[303] it commits to ‘consider[ing]’ SCMs like constructed wetlands for new major roads and upgrades to roads, and permeable surfaces in lower-traffic situations.[304] VicRoads also reportedly pays offset contributions to Melbourne Water under a voluntary agreement to counter its stormwater impacts.[305] These arrangements could be formalised and made more rigorous using a direction of the Minister responsible for roads, requiring a road authority to comply with an updated BPEM or other improved stormwater management standards.[306]

Victorian environmental law plays a relatively peripheral role in addressing stormwater flows, and is primarily aimed at addressing pollution and waste issues. A new ‘general environmental duty’ under the Environment Protection Act 2017 (Vic) (‘Environment Protection Act’) requires that a ‘person who is engaging in an activity that may give rise to risks of harm to human health or the environment from pollution or waste must minimise those risks, so far as reasonably practicable’.[307] The duty does not contemplate environmental harm that arises in other ways (for example, caused by peak stormwater flows, as distinct from contaminants), unlike general environmental duties in some other jurisdictions, which encompass ‘environmental harm’ more generally.[308] Accordingly, although some have anticipated using this provision to support regulatory standards for stormwater management,[309] Victoria’s narrower, pollution-focused provision may constrain the scope and content of these standards. Nonetheless, a variety of other environmental laws — primarily related to catchments and agreements with private landholders — provide other opportunities to address stormwater CEEs.

The key regulatory policy dealing with urban stormwater under the Environment Protection Act 1970 (Vic) (a state environment protection policy) focuses on stormwater quality impacts more than flows.[310] It sets out water quality standards that apply to various ‘beneficial uses’ of water, including ecological uses, requirements for managing pollution discharges,[311] and actions that arise where standards are not met.[312] The state environment protection policy continues a long-established requirement for councils to develop stormwater management plans that identify options and implementation plans for preventing the generation of stormwater and minimising the velocity and volume of stormwater flows.[313] The effectiveness of these plans is, however, uncertain. Publicly available plans vary widely in their currency, many focus almost exclusively on stormwater quality rather than flow issues (even where they recognise the ecological problems caused by excessive stormwater flows),[314] and some appear superseded by broader water management planning processes.[315] More recent ‘integrated water management plans’ are intended to focus on relatively narrow, location-specific improvements to the amenity of urban waterways,[316] rather than adopting the broad-based approach to stormwater management that could achieve the ambitious objectives of the Healthy Waterways Strategy. Regardless of their vintage and title, municipal stormwater-related strategies commonly refer to the BPEM’s stormwater flow goal, but do not clearly intend this to be considered in individual developments.[317]

The Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 (Vic) (‘Catchment and Land Protection Act’) also sets out somewhat rusty regulatory tools that might be used to address sick city streams — the usefulness of which may increase under amendments recently passed by Parliament.[318] Each of the 10 Victorian Catchment Management Authorities (‘CMAs’) for which this Act provides[319] can recommend that the Minister declare any land[320] as a ‘special area’, either as a ‘water supply catchment area’ or for any other purpose.[321] In considering the matter, the Minister ‘must ... hav[e] regard to how the existing or potential use of the area may adversely affect ... water quality or aquatic habitats’ or aquifer recharge or discharge areas.[322] Developments that increase DCI clearly have these adverse effects.[323]

Declaring a special area triggers the potential for a catchment authority to prepare a plan for the area.[324] A plan identifies land management issues to be dealt with, corresponding actions and targets, and responsible parties.[325] Though there is no legal mandate to undertake actions,[326] a catchment authority may recommend that a planning scheme be amended to give effect to a plan,[327] and ‘a Minister or public authority must have regard to’ a plan when carrying out a function involving land management.[328] This could provide the basis for public authorities considering stormwater flow effects when managing land, addressing the gap outlined in Part IV(A) above.

The state environment protection policy for water is also relevant to planning decisions about specific projects.[329] It requires councils to ‘ensure all new development[s] meet the objectives for environmental management of stormwater as set out in the [BPEM]’,[330] recognising that ‘[u]rban stormwater runoff volume, flow and frequency’ can significantly ‘degrad[e] the ecological integrity of streams’.[331] However, the state environment protection policy applies only a limited qualitative requirement of ‘minimis[ing] ... the quantity of stormwater leaving the property boundary and to hold or use it as close to where it is generated as possible’.[332] It appears that the State government favours updating the BPEM (currently under review)[333] to allow for flexibility, rather than including flow standards in a new State environment protection policy.[334]

Special area plans under the Catchment and Land Protection Act have stronger legal ‘teeth’ if they apply binding and potentially wide-ranging project-level ‘land use conditions’ to particular properties,[335] which it is an offence to disobey.[336] The Act clearly contemplates that these conditions might require action that benefits ‘other persons or bodies’, and requires that compliance costs be transparently apportioned between landowners and other beneficiaries.[337] Practitioners have suggested using special area plans to subsidise landholders who undertake management practices that improve stormwater quality, as this provides community benefits.[338] This could be applied to landholders who maintain permeable surfaces or install SCMs.

Activating this potential of special area plans would require reinvigorating and expanding their use. Only one of the existing 134 special water supply catchment areas was declared after 1991,[339] and no special area has been declared for any other purpose.[340] However, existing land use conditions provide a precedent for restrictions that would help sick city streams, such as restricting a change from vegetated land uses without a catchment authority’s approval,[341] and prohibiting buildings within a riparian buffer.[342] There is also some evidence of land use conditions being formulated considering the adverse impacts of increased stormwater flows and in relation to urban areas.[343] However, special areas are not prominent in current policy. Recent departmental, ministerial and Auditor-General documents relating to catchment authorities essentially ignore special area plans.[344] A recent Act transferred to Melbourne Water the power to formulate plans for water supply catchment areas (but not other types of special areas) in its district.[345] Melbourne Water, which has a clear regulatory role, might be more inclined to undertake such action to protect sick city streams than catchment authorities, which carefully protect their reputations as facilitators of good landholder management, and tend to eschew their regulatory powers.[346]

Binding agreements between statutory or government entities and individual landowners could achieve many of the same protections as special area plans, but at the project level. The Victorian Conservation Trust Act 1972 (Vic) and the Conservation, Forests and Lands Act 1987 (Vic) provide for a landowner to enter a covenant with the statutory body, Trust for Nature, and a ‘land management co-operative agreement’ (‘CFL agreement’) with the Secretary of Parks Victoria, respectively.[347] A covenant may cover only ‘land which the Trust considers to be ecologically significant, of natural interest or beauty’ or important ‘to the conservation of wildlife or native plants’,[348] while a CFL agreement has no equivalent restriction.[349] Covenants tend to be conceived as instruments for preserving land, including riparian environments.[350] CFL agreements are better known for restoration, including through a program of substantial artificial wetlands to address stormwater and protect endangered species on Melbourne’s urban fringe.[351] In fact, both mechanisms may provide for the use, development and management of the land, including restricting activities on the land.[352]

Landowners may receive financial incentives for agreeing to either mechanism, both directly, as grants or loans for land management,[353] or indirectly, where a planning permit condition requires an agreement.[354] Landholders may receive ongoing financial support through ‘rate concessions, tax concessions or volunteer labour support’,[355] technical advice about land management,[356] and assistance with environmental monitoring and formulating management plans that are registered on title in the case of covenants.[357] Although both types of agreements may run with the land[358] and are enforceable,[359] by default, covenants govern land management for conservation in perpetuity,[360] whereas a CFL agreement may terminate on agreed terms,[361] and may be varied or removed from title in a less burdensome way.[362]

Interest in using both mechanisms to benefit city streams is growing. Trust for Nature supports increasing the use of covenants to improve waterway health, including in the Yarra River corridor[363] and other metropolitan ‘focal landscapes’.[364] This enthusiasm seems well placed. Strategically selected project-level covenants and CFL agreements facilitate ongoing active management by landowners (eg constructing and maintaining SCMs), potentially secured in perpetuity. Regional- and project-level planning mechanisms[365] are shorter-term and lack structures for ongoing support (though they may provide for off-site restoration activities). However, funding environmental agreement mechanisms presents a challenge at scale. The CFL agreements used for biodiversity and stormwater benefits in outer Melbourne are funded by once-off biodiversity offset payments made by developers who clear environmentally important land, with no ongoing funding.[366] CFL agreements and covenants are also voluntary.[367] Nonetheless, recognising their usefulness beyond pristine land — for constructing SCMs with attendant biodiversity benefits on modified urban riparian land, with appropriate funding — would produce a strong legal approach to restoring, and not just preserving, urban waterways.

Regulatory mechanisms in water statutes have traditionally controlled intentionally taking water out of rivers,[368] rather than land use changes that affect how water enters rivers. Indeed, over the past decade, water laws have increasingly sought to ensure that rivers and aquifers have sufficient water for ecological purposes,[369] rather than dealing with overabundance. The Water Act 1989 (Vic) (‘Water Act’) primarily addresses excessive stormwater flows by three regional mechanisms that provide for protecting water supply areas,[370] designating flood hazard areas,[371] and areas in which developers must contribute to the cost of drainage, including retarding basins and wetlands.[372]

Water supply protection areas are declared to enable the preparation of management plans to protect the relevant water resources.[373] While the focus of the management plans is on ensuring sustainability through restrictions on the taking of water, they may also prescribe ‘conditions relating to the protection of the environment, including the riverine and riparian environment’.[374] This could theoretically take the form of restricting new DCI over aquifer recharge areas, most likely through knock-on amendments to a planning scheme, or a water authority objecting to a referred planning permit application.[375] This would both protect the sustainability of the groundwater resource and prevent increased stormwater flows.

The Minister may declare land liable to flooding to be a floodway.[376] In these areas, councils must prevent land uses that are inconsistent with flood hazards[377] and there are restrictions on building works or structures without specific consents, and even provision to remove existing structures (potentially with compensation).[378] Though they are not intended to address stormwater CEEs, floodways incidentally control development, thereby restraining future stormwater CEEs.

More widely applicable, intentional controls on stormwater CEEs arise through drainage schemes in intensive development areas.[379] These ‘stormwater offset’ schemes use SCMs to protect waterways and floodplains in urban growth areas for flooding, water quality, and environmental purposes.[380] However, they have significant gaps: they may not apply to commercial or industrial land, but only to developable residential land of significant size,[381] and only seek to prevent escalating — rather than decreasing — existing levels of runoff.[382] Extending standards to non-residential developments may be necessary to protect waterways.[383] Interestingly, developer contributions fund measures to address the adverse drainage effects of both developable and non-developable land, such as existing roads.[384] This means future development pays to mitigate the effect of past development — a rare example of addressing the CEEs of existing DCI despite the law’s typical distaste for retroactivity.

Current reform recommendations include ensuring that the availability of drainage offsets does not remove obligations to undertake on-site works, where appropriate.[385] Emerging state and national government initiatives in the area of environmental economic accounting[386] could also ensure that payments robustly capture the full lost socio-environmental value of affected city streams. More ambitiously, environmental economic accounting might also be used to prioritise and fairly recover contributions for SCMs that reverse, rather than just reduce, harm from stormwater CEEs.

In a conceptually similar way to the general environmental duty under the Environment Protection Act,[387] the Water Act imposes liability on individual landowners for injury, property damage or economic loss caused by a ‘not reasonable’ flow of water from the person’s land.[388] This amounts to a project-level control over an existing activity. It may also indirectly influence how developers structure their future developments. However, in its present form, the provision is unlikely to encourage developers to reduce or retain stormwater runoff, particularly if the foreseeable damage is ecological (noting that the above-mentioned government initiatives to account for environmental assets in economic terms might theoretically bridge this gap). Moreover, planning laws and stormwater guidelines may be seen to authorise stormwater flows,[389] which may support arguments that a flow of stormwater is reasonable.[390] The provision would better protect city streams from stormwater CEEs if it were amended to encompass ecological damage, and if ministerial guidelines[391] defined ‘reasonable flows’ with reference to pre-development runoff (particularly given existing precedent for this standard in precinct structure plans).[392]

Statutory water-related easements over individual landholdings are an entirely different kind of project-level control. Water authorities (to which subdivision proposals under planning laws are referred) may require the creation of an easement on subdivision for various water-related purposes, including pipelines, channels, carriageways, waterway management and drainage.[393] A person must not build a structure over the easement without the authority’s consent.[394] This discourages development, although it does not necessarily prevent the authority from constructing an impermeable surface consistent with the easement powers (for example, a road or concrete channel).

The broad range of mechanisms set out in this part not only have the varying strengths, weaknesses and opportunities for improvement detailed above and summarised in Figure 1 below (and synthesised in Part VI from a CEE perspective), but varying application on the ground. Some apply uniformly in space, for example, the Water Act’s liability provision[395] and the statewide standard Victoria Planning Provisions. They constitute what this article terms ‘basic legal mechanisms’. However, many of the legal mechanisms relevant to controlling stormwater flows apply only in certain regions. This opens the way to the spatio-legal approach introduced in Part II(B) to assess gaps in the spatial application of these mechanisms, building a more complete view of not only how, but where, the law treats the stormwater flows that threaten city streams.

Figure 1: Summary of Statutes and Mechanisms Affecting the Cumulative Environmental Effects of Stormwater in Urban Melbourne

* Included for completeness, but discussed separately from statutory mechanisms, as establishing goals for city streams.

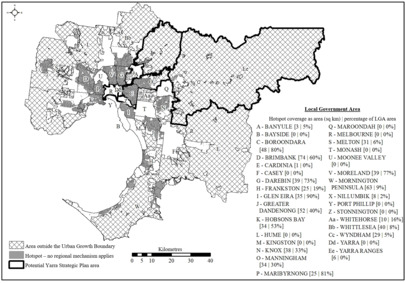

The first part of the exploratory spatio-legal approach presented here examines how law may allow additional stormwater flows to burden already sick city streams. It uses publicly available spatial data to aggregate ‘layers’ of key existing spatially defined (ie regional) legal mechanisms discussed in Part IV to identify gaps or ‘hotspot’ areas in which development-induced stormwater flows are more likely to arise (relative to other areas).[396] These ‘hotspots’ rely solely on ‘basic legal mechanisms’ — project-level controls that apply statewide (eg State-standard planning permit considerations, building regulations, the general environmental duty, and the liability rule for unreasonable flows). Areas that are covered by one or more of the regional mechanisms discussed above are not deemed ‘hotspots’. Potential future hotspots are contextualised by presenting standardised information on urban waterway health. Note that these hotspots relate to stormwater flows caused by DCI, and do not relate to stormwater quality, consistent with the recognition in Part II(A) that excess stormwater flows themselves adversely impact river ecology. Since planning laws deliver the most prominent legal mechanisms for addressing stormwater flows, spatial information is aggregated by LGA, as municipal councils are the key decision-makers under planning laws.[397] This produces an aggregate spatial view of the complex suite of legal controls relevant to stormwater generation, as they appear on paper, and a standardised view of Melbourne waterway health data by LGA. These data also highlight the municipalities potentially covered by the YSP, which facilitates coordinating stormwater-related actions in these areas.[398]

This approach is intended to raise further questions for exploration, rather than definitively evaluate stormwater-related legal mechanisms. Its exploratory and preliminary nature necessarily involves limitations. In categorising land as either a ‘hotspot’, or alternatively as an area covered by at least one regional legal mechanism,[399] the analysis adopts a conservative approach: it errs on the side of overestimating controls on future stormwater generation (that is, underestimating hotspots). This accommodates the potential for each mechanism to be used to its fullest extent, and highlights areas that are most likely to benefit from increased attention to regulatory change (as opposed to increased attention to implementing existing mechanisms). Future empirical research may well point to significant differences between this best-case scenario of law on paper, on the one hand, and the extent to which these controls are implemented, on the other. Crown land is treated as having an overall protective effect, since the available data do not permit analysis of individual Crown reserve management agreements, and licences and leases over Crown land.

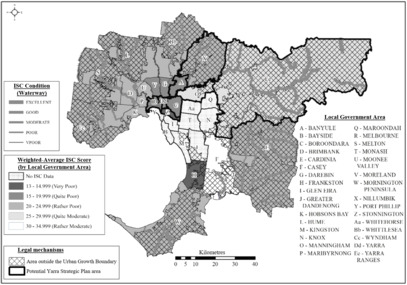

Figure 2 shows the average stream condition of the waterways in or bordering each LGA,[400] weighted by the length of relevant stream reaches, and the waterway reaches that fall into each stream condition category (Poor, Moderate, Good, Very Good, or Excellent) used in the most recent Index of Stream Condition report,[401] with lighter shading indicating better health. The width of waterways shows the stream condition for that waterway reach, with a wider line indicating better health. Stippled areas have no relevant stream condition data available. Municipalities potentially covered by the YSP have thick black borders; the cross-hatched areas are outside the urban growth boundary.

Figure 2 shows that stream conditions vary widely across Melbourne LGAs, but are generally quite poor. Better stream health is generally found further from the CBD, with Frankston a notable exception. There is no clear pattern of differences in stream health between eastern and western Melbourne, despite industry concentration in the west.[402] Stream health in the potential YSP area also varies substantially, increasing in health in the upper catchment LGAs, but decreasing in health in the inner city LGAs, with the exception of Manningham. This is notable for the purposes of determining the YSP area: the YSP will address municipalities that suffer most from sick city streams if it includes the full area of the lower catchment LGAs, notably Stonnington (very poor health), and Melbourne, Yarra, Boroondara and Banyule (all quite poor health).

Figure 2: Ecological Health of Major Urban Streams by Local Government Area (ISC refers to index of stream condition)

Figure 3 displays the area and percentage of land in each LGA classified as a hotspot (hotspots shown in grey, representing the gaps remaining after aggregating layers of each regional mechanism). These hotspots have comparatively high legal potential for development-induced increases in stormwater flows because no regional legal mechanism controls stormwater flows, and they rely solely on ‘basic’ mechanisms that apply statewide.