Melbourne University Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Melbourne University Law Review |

|

Gary Edmond,[1]* David White,[1]** Alice Towler,[1]† Mehera San Roque[1]‡ and Richard Kemp[1]‡‡

Drawing upon decades of scientific research on face perception, recognition and comparison, this article explains why conventional legal approaches to the interpretation of images (eg from CCTV) to assist with identification are misguided. The article reviews Australian rules and jurisprudence on expert and lay opinion evidence. It also summarises relevant scientific research, including emerging research on face matching by humans (including super-recognisers) and algorithms. We then explain how legal traditions, and the interpretation of rules and procedures, have developed with limited attention to what is known about the abilities and vulnerabilities of humans, algorithms and new types of hybrid systems. Drawing upon scientific research, the article explains the need for courts to develop rules and procedures that attend to evidence of validity, reliability and performance — ie proof of actual proficiency and levels of accuracy. It also explains why we should resist the temptation to admit investigators’ opinions about the identity of offenders, and why leaving images to the jury introduces unrecognised risks by virtue of the surprisingly error-prone performance of ordinary persons and the highly suggestive (or biasing) way in which comparisons are made in criminal proceedings. The article recommends using images in ways that incorporate scientific knowledge and advance fundamental criminal justice values.

Contents

I Improving Legal Practice with Scientific Research

This article is about the use of images in criminal proceedings.[1] It considers how courts should engage with the interpretation of images to assist with identification and, inexorably, the role of scientific research in the admission, presentation and evaluation of this evidence. The article provides an overview of scientific research on the use of images for the purpose of identifying persons of interest (‘POIs’). This follows a review of the piecemeal Australian jurisprudence pertaining to the admission and interpretation of image evidence.[2] Juxtaposed, these two reviews palpably demonstrate the limits of legal concepts and prevailing practice. It is our contention that recourse to scientific knowledge can help to ensure the admission of opinions that are reliable (and actually expert) and likely to enhance factual accuracy, efficiency and the fairness of criminal justice processes.

Confronted with the rapid expansion in the availability of images, from the turn of the millennium Australian courts imposed epistemologically arbitrary constraints on the use of images to assist with the identification of POIs.[3] These restrictions appear to have been based on judicial anxiety about the value of the opinions but are blind to the actual abilities or accuracy of purported identification experts. Drawing upon mainstream scientific knowledge, we explain what courts should be looking for in order to identify: those who possess actual expertise; the scope and limits of their abilities; and how their opinions ought to be expressed. We also draw upon this knowledge base to consider how we might respond to emerging forms of expertise and expert systems that do not necessarily sit comfortably within conventional legal categories and conceptualisations — such as the opinions of super-recognisers,[4] the outputs of face matching algorithms and even combinations of humans and/or algorithms (ie hybrid systems).[5] This article offers an evidence-based approach to the interpretation of images — that is, it is concerned with scientific knowledge. Therefore, the article is conspicuously sensitive to accuracy and presenting evidence (whether an opinion or the output of an algorithm) in a manner that embodies its value so that it is susceptible of rational evaluation.[6]

In this article we refer to those whose abilities at face comparison have not been formally established — ie demonstrated in controlled conditions where the correct answer is known — as purported experts. We call them ‘purported’ because we do not know if they are actually expert at the specific task, namely identifying a POI or describing their features.[7] For more than a decade (up to 2014), Australian courts allowed purported experts to identify POIs or features said to be shared between a POI and a defendant.[8] Purported experts were not required to provide information about their abilities, the degree to which facial features are correlated, or how patterns of correlations vary (ie diagnosticity).[9] Evaluation of the opinions of purported experts was left to the exigencies of the trial. Reception was moderated by trial safeguards (eg cross-examination and judicial instructions) that were not always informed by contemporary scientific knowledge.[10] Eventually, following Honeysett v The Queen (‘Honeysett’), (some) purported experts were prevented from proffering opinions, though the extent of that proscription remains uncertain.[11] Overall, Australian judges erected an admissibility regime that directs limited attention to the epistemic value of images or the serious risks posed by their interpretation.[12]

This article is intended to encourage courts to reconsider their position(s). Courts, we contend, should be more sceptical consumers of facial recognition and image comparison evidence. Guided by scientific research, courts can and should be more accommodating of some types of opinion evidence, but less accommodating of others. They should possess effective means of distinguishing between different types of direct and indirect witnesses, determining which indirect witnesses have genuine abilities, and gauging the probative value of both opinions and the outputs of face matching algorithms.[13] They should also be more attentive to scientific research on unconscious bias and its deleterious impacts on perception and interpretation.[14] Our analysis begins with a synoptic overview of the main developments in the Australian jurisprudence over the last two decades, including the expanding reliance on common law categories such as the ‘ad hoc’ expert.[15] In Part III we have assembled and synthesised scientific research on unfamiliar face comparison to provide the foundations for a more principled approach to the use of images. Drawing on these reviews, Part IV raises a series of considerations (and makes a few recommendations) that ought to inform legal reliance on images used as evidence of identity in

criminal proceedings.

Now ubiquitous, images can fulfil a range of evidentiary functions in investigations and prosecutions. They can be used to identify persons, to track movements and to determine what was done, when and by whom.[16] All of these uses involve interpretations that may vary from the easy and mundane to those which are extremely difficult, contested, and error-prone. The value of images as evidence depends on their use (eg the type of interpretation), the quantity and quality of the images, as well as the abilities of those (whether individuals or algorithms or hybrid systems) interpreting them — see Part III.

In this article we are concerned with the use of images to assist with the identification of POIs — frequently those involved in criminal activity. This can be based on recognition (from memory and some degree of familiarity) or the comparison of a POI in images with reference images (usually of a person whose identity is known).[17] We are primarily concerned with identification by strangers based on comparisons — sometimes described as unfamiliar

face matching or forensic image comparison.[18] That is, comparisons performed by those with little to no familiarity with the suspect/defendant (prior to

an investigation).[19]

Our review begins with Smith v The Queen (‘Smith’)[20] — the High Court’s first attempt to respond to some of the implications of the dramatic expansion in the availability of images.[21] During the trial, two police officers with some limited exposure to Mundarrah Smith purported to identify him in low-quality images of an armed robbery — see Figure 1.[22] On appeal, the High Court deemed this evidence inadmissible.[23] According to the majority, the police officers were not entitled to identify Smith as the POI in the bank robbery because each offered nothing beyond what a jury could bring to the comparison.[24] During the course of the trial, members of the jury would have more exposure to the defendant than either of the police officers obtained during their previous dealings.[25] For the majority, the opinions (ie interpretations) of the police officers would add nothing to the jury comparisons.[26] They could not ‘rationally affect (directly or indirectly) the assessment of the probability of the existence of a fact in issue in the proceeding’.[27] They were, by definition, irrelevant.[28]

Figure 1: The bank robber alleged to have been Mundarrah Smith

An exception — the Smith caveat — was available where witnesses held some non-trivial advantage over the trier of fact.[29] This might arise where the appearance of the defendant had changed, or movement (eg gait) was significant and they had been exposed to these in ways that gave them a distinct advantage over the trier of fact.[30] The majority explained:

In other cases, the evidence of identification will be relevant because it goes to an issue about the presence or absence of some identifying feature other than one apparent from observing the accused on trial and the photograph which is said to depict the accused. Thus, if it is suggested that the appearance of the accused, at trial, differs in some significant way from the accused’s appearance at the time of the offence, evidence from someone who knew how the accused looked at the time of the offence, that the picture depicted the accused as he or she appeared at that time, would not be irrelevant. Or if it is suggested that there is some distinctive feature revealed by the photographs (as, for example, a manner of walking) which would not be apparent to the jury in court, evidence both of that fact and the witness’s conclusion of identity would not be irrelevant.[31]

Justice Kirby adopted a different course. He was unwilling to unilaterally invoke (ir)relevance in the High Court when it was not relied on by the parties or judges during the trial and appeals.[32] Rather than treat the police officers’ impressions as irrelevant, for Kirby J there was no exception to the exclusionary opinion rule[33] that would render them admissible.[34] The opinions were not ‘based on what [the officers] saw, heard or otherwise perceived about a matter or event’ and so were not admissible under the exception for lay opinion in

s 78(a) of the Uniform Evidence Law.[35] Nor were the opinions based on ‘specialised knowledge’ — the police officers had none — and so they were not admissible under the exception for expert opinion in s 79(1).[36] Thus, all of the judges agreed that the police officers’ opinions were inadmissible, but Kirby J’s reasoning offered a potential solution to the majority’s proscription by drawing attention to the possibility of admission if the conditions of s 79 could be satisfied.[37]

Indirectly, then, Smith encouraged investigators and prosecutors to call upon a variety of witnesses presented as experts, sometimes characterised as facial mappers or face and body mappers, to provide opinions about the identity of the POI in images based on ‘training, study or experience’ that was presented as apposite.[38] These individuals often possessed formal qualifications and/or experience in anatomy (and other domains) that were considered by courts to be capable of grounding an ability to interpret images to assist with identification.[39] As we shall see, when considering admissibility under s 79(1), lawyers and judges were not particularly attentive to the fact that the individuals proffering opinions were almost always experts in domains (or ‘fields’) not centrally concerned with image comparison or identification.[40] It does not follow, for example, that a person with formal qualifications and experience in anatomy, or even facial reconstruction from skeletal remains, will be better than lay persons (eg jurors) at comparing faces, or discerning facial or body features or movement, in images.[41] Expertise cannot be assumed to be transferable and knowledge of body parts (and Latin nomenclature) may have no correspondence with interpretive ability.[42] In the admissibility decisions and appeals following Smith there is little apparent interest in the performance (ie ability and accuracy) of the purported experts admitted as expert witnesses.[43] The issue of ‘specialised knowledge’ was considered in only a few instances.[44] The most

influential of these decisions was also the least satisfactory.

In R v Tang (‘Tang’), the value of ‘expert’ interpretations came into question when a challenge to the admissibility of an anatomist’s opinions about the

identity of a defendant in an armed robbery was raised on appeal.[45] The

anatomist testified that the POI in security images and Tang were ‘one and the same’ — see Figure 2 below.[46] This was based on her comparison of both faces and bodies:

Her evidence included a comparison between the two sets of material [ie the images of the robbery and reference images of Tang in Figure 2] in terms of identifying similarities such as the thickness of the lips, the existence of a dimple on the chin, the fact that each chin was ‘squarish’ and the jaw structure ‘angular’. She also identified, in accordance with her classification that was before the jury, that the two facial forms were ‘pentagonal’, that the facial height was ‘medium’, and there was a ‘lateral projection’ of the cheekbones, meaning a projection to the side. She referred to a wide chin and visible lips seam, a slight projection of the ears and what is described as a ‘mezzo-cranic head shape’, meaning a short, broad and high head with a flattened occipital region, being the back of the head. She also identified a number of the features in both sets of material as characteristics of an Asian person. She referred to similarities in terms of the ‘upright posture of the upper torso’. Dr Sutisno also identified three ‘unique identifiers’: the lips, the wide square chin with a dimple and the posture.[47]

The New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal (‘NSWCCA’) was persuaded about the existence of a ‘field’ of facial comparison, but not one concerned with comparison of the body:[48]

The detailed knowledge of anatomy which Dr Sutisno unquestionably had, together with her training, research and experience in the course of facial reconstruction supports her evidence of facial characteristics.

Nothing was presented to the Court which indicates, in any way, that Dr Sutisno’s extension from facial to body mapping, with respect to matters of posture, has anything like that level of background and support.[49]

The reasons for the distinction are not particularly clear. It is not a distinction supported by scientific research.[50]

Figure 2: Copy of an exhibit (photo board) produced by the anatomist in Tang. The POI in an armed robbery is juxtaposed with a reference image of Tang. Note the deliberate orientation of the face in the inset marked ‘5’.

Operating in the Uniform Evidence Law tradition, where the opinion rule (s 76) covers the field — excluding all opinions adduced ‘to prove the existence of a fact about the existence of which the opinion was expressed’ unless there is an express exception — the NSWCCA nonetheless unhelpfully drew upon the common law conception of the ‘ad hoc expert’.[51] This was presented as consistent with s 79(1) and able to support the admission of an opinion about

apparent similarities:

The identification of points of similarity by Dr Sutisno was based on her skill and training, particularly with respect to facial anatomy. It was also based on her experience with conducting such comparisons on a number of other occasions. Indeed, it could be supported by the experience gained with respect to the videotape itself through the course of multiple viewing [sic], detailed selection, identification and magnification of images. By this process she had become what is sometimes referred to as an ‘ad hoc expert’.[52]

‘Ad hoc expert’ is a legal category that privileges the interpretations of individuals — usually investigators or those working with them — who are said to have obtained an advantage over the trier of fact through repeated exposure to some stimuli (typically some kind of recording).[53] The concept was originally applied to opinions about the content of audio recordings — specifically the words allegedly spoken and transcribed[54] — on the basis of repeated listening.[55] Over time, permissive courts have allowed police and others engaged in the investigation to express their opinions about the identity of the speaker and, by

analogy, the identity of persons in images.[56]

Ad hoc expertise is purported expertise.[57] Ad hoc experts are not known to be expert — ie significantly better than juries — at the task of identifying POIs in images.[58] In many, perhaps most, cases they do not appear conversant with (and do not reference) relevant literatures and research on image (or voice) comparison and associated dangers, or the most effective means of making expert opinions comprehensible.[59] They often undertake their comparisons in biasing conditions, such as where detectives ask them to compare a POI with a nominated suspect or suspects (as in Tang).[60] The concept of the ad hoc expert has been developed and applied for reasons of legal expediency — convenience to the courts, prosecutors and investigators — without attending to performance and the serious risks posed by the manner in which opinions are obtained, presented and evaluated. Ad hoc experts are prone to making (or attempting to make) categorical claims, such as claiming that an offender and alleged suspect are ‘one and the same’.[61] Ignorant of — or inattentive to — research on face comparison and widespread criticism of the identification paradigm, ad hoc experts do not appear to appreciate the difficulty of the task, the level of error, or the magnitude of risks from cognitive bias.[62]

Not conspicuously engaged with relevant scientific research, Spigelman CJ concluded that the ‘specialised knowledge’ said to be underpinning the ad hoc expert’s opinion was not able to support an identification.[63]

Facial mapping, let alone body mapping, was not shown, on the evidence in the trial, to constitute ‘specialised knowledge’ of a character which can support an opinion of identity.[64]

Yet, that ‘knowledge’ was said to (somehow) enable the anatomist to identify and discriminate between anatomical features in the images.[65] This is a kind of admissibility compromise.[66] It allows a highly qualified witness, called by the prosecutor, and likely to be formally ‘qualified’ as an expert before the jury, to express speculative opinions insinuating identity.[67] Juries could hear testimony about purported similarities — such as the ‘thick’ lips and ‘square’ chin with ‘a dimple’ — and the absence of discernible differences, but the anatomist could not positively identify the POI as Tang.[68] The jury would receive no information, about the abilities of the witness or the frequency and independence of facial features, that might enable them to make sense of the opinions.[69]

Judicial attempts to rescue identifications based on s 79(1) — by suggesting that the opinions of ad hoc experts are based on ‘specialised knowledge’[70] — seem strained to say the least. At best, such attempts privilege training in an apparently related field and ‘experience’ with a particular person or set of images (or voice recordings).[71] This reliance is difficult to reconcile with s 76 of the Uniform Evidence Law and the limited exception s 79(1) provides for opinions based ‘wholly or substantially’ on ‘specialised knowledge’.[72]

Tang is curious because endorsement of the common law idea of ad hoc expertise occurs alongside recourse to the United States (‘US’) Supreme Court’s influential Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc (‘Daubert’) jurisprudence.[73] Daubert was imported to assist with the definition of ‘specialised knowledge’:

The word ‘knowledge’ connotes more than subjective belief or unsupported speculation. The term ‘applies to any body of known facts or to any body of ideas inferred from such facts or accepted as truths on good grounds’.[74]

In Daubert, and the cases that followed it, the US Supreme Court explained that the word ‘knowledge’ (in r 702 of the Federal Rules of Evidence, 28 USC (1975)) imposed the need for reliability and validation of scientific evidence.[75] Remarkably, given this provenance, along with trends in comparable common law jurisdictions, the NSWCCA insisted that reference to ‘specialised knowledge’ in s 79 of the Uniform Evidence Law did not require trial judges or prosecutors to consider the reliability of opinions.[76] Rather, ‘[t]he focus of attention must be on the words “specialised knowledge”, not on the introduction of an extraneous idea such as “reliability”’.[77]

The upshot is that Australian prosecutors, trial judges and appellate courts are not concerned with reliability as a condition for the admission of opinion evidence in criminal proceedings.[78] Precisely what kind of knowledge, let alone specialised knowledge, is not reliable (or indexed to the tradition of justified (true) belief) is yet to receive elaboration.[79] Lack of attention to the validity and reliability of forensic science procedures, and the empirical basis of the words used to express opinions, form part of the unfortunate legacy of Tang.[80] Rather than require the proponent of the opinion (ie the purported expert) to provide evidence of actual expertise — here, empirical evidence of an ability to accurately compare faces and/or bodies to assist with the identification of persons in images — the Court in Tang instead relied upon proxies.[81] These proxies included the witness’s training in anatomy, experience reconstructing faces from skulls,[82] the existence of general literature,[83] the fact that the witness had previously compared images for the police and other courts,[84] and her exposure to the images of the robbery for some unknown period of time.[85]

Tang was endorsed by common law courts in Murdoch v The Queen (in the Northern Territory) and R v Dastagir (in South Australia).[86] These decisions are not particularly attentive to common law admissibility rules that require a field of expertise and a qualified expert in that field who can assist the jury.[87] Judges in these jurisdictions also placed reliance on anatomical training and the admission of similar evidence in Uniform Evidence Law jurisdictions, notwithstanding differences in admissibility rules.[88] They were also willing to extend the scope of ad hoc expertise from the preparation of transcripts to the identification of POIs in video and sound recordings.[89] None focused on actual expertise in facial comparison for the purposes of identification. Of interest, in Murdoch, the Northern Territory Court of Criminal Appeal also endorsed the admissibility of opinions from persons who were very familiar with the defendant prior to the investigation (‘familiars’).[90] These familiars were allowed to identify the POI in poor-quality images at a truck stop as Murdoch.[91]

After Tang, the individuals (mostly anatomists) enlisted by investigators and called upon by prosecutors to testify did not always adhere to the judge-imposed restrictions limiting their opinions to descriptions of similar features.[92] It was common for anatomists (and others) to attribute significance to features said to be similar — at least in their reports.[93] As those engaged in criminal activities began to wear disguises in response to the prevalence of security cameras (and facial mappers), the purported experts called by prosecutors began to express opinions that stimulated further judicial intervention.[94]

The judgment in Morgan v The Queen (‘Morgan’) is probably the clearest expression of judicial concern and reasoned exclusion.[95] The issue confronting the NSWCCA involved a different anatomist drawing attention to multiple similarities between a robber covered from head to toe in clothing and the Indigenous defendant — see Figure 3 below.[96] Professor Maciej Henneberg — the Wood Jones Chair of Anthropological and Comparative Anatomy at the University of Adelaide — listed the following features as shared between Morgan and the POI in his report:

Person of interest is an adult male of heavy body build. His shoulders and hips are wide. He has a prominent abdomen but his upper and lower limbs, especially in their distal segments, are not thick. This suggests centripetal pattern of body fat distribution. This pattern consists of the deposition of most body fat on the trunk while limbs remain relatively thin. His head and face were covered by a garment well adhering to the surface of the skin. This enabled me to make observations of the head shape, nose and face profile. His head is dolichocephalic (elongated) in the horizontal plane (viewed from above). His nose is wide and rather prominent while his face has straight profile (orthognathic). He is right-handed in his actions and carries himself straight.[97]

In addition, Professor Henneberg’s testimony stated that ‘Australian Aboriginals’ have

long thin limbs and that, when they put on weight due to a Western diet, it tended to be concentrated in the trunk, the process he described as centripetal fat distribution. He observed these features in the offender in the CCTV footage and, later, in the images of the appellant. It is apparent from the [reference] photos of the appellant in evidence that he is Aboriginal.[98]

In his report and testimony, Professor Henneberg attributed significance, namely ‘a high degree of anatomical similarity’, to the features he described.[99]

Figure 3: Robber alleged to be Morgan (centre)

The Morgan Court was not especially interested in the validity and reliability of the procedure or evidence of Professor Henneberg’s abilities.[100] Rather than require analysis of the method (or ‘approach’), the Court drew attention to the need to assist the jury (as discussed in Smith)[101] and the lack of ‘satisfactory’ explanation,[102] remarking that

this is not the occasion to examine the science of body mapping or to undertake some general appraisal of Professor Henneberg’s approach. ... [T]he question is whether he had specialised knowledge, beyond the reach of lay people, which he brought to bear in arriving at his opinion. That question fell to be answered by reference to the task which he undertook.

That task was to make an anatomical comparison between relatively poor quality CCTV images of a person covered by clothing from head to foot with images of the appellant. Applying his specialised knowledge, Professor Henneberg claimed, he was able to detect not just a measure of similarity but ‘a high level of anatomical similarity’ between the two persons. How he was able to do that when no part of the body of the offender in the CCTV images was exposed was, in my view, never satisfactorily explained.[103]

Why an appeal considering the admissibility of opinions proffered by a face and body mapper was not ‘the occasion to examine the science of body mapping’,[104] or the general methods, might be thought to raise a question. How can a court determine if an opinion is based on ‘specialised knowledge’ without considering the ‘approach’ and its correspondence with knowledge?[105]

In Morgan, the NSWCCA was nevertheless attentive to the precise ‘task’ that the expert performed — in italics in the extract above — though the contention that the opinion was not based on ‘specialised knowledge’ appears declaratory:

Whatever might be made of the professor’s observations of the offender’s body shape through his clothing, his observations about the shape of his head and face were clearly vital to his conclusion that there was a high degree of anatomical similarity between that person and the appellant. It does not appear to me that those observations could be said to be based upon his specialised knowledge of anatomy.[106]

The fact that the head and body were covered compounded the issues. The professor’s experience with body shapes and sizing for the clothing industry did not redeem his interpretations:

Professor Henneberg’s evidence about his experience of the clothing industry ... appears to be confined to the size and hang of garments, and their relation to ‘body shape and posture’. ... [T]he evidence does not convey that his experience extends to the observation of anatomical features of the head and face of a person whose head is entirely covered by a garment such as a balaclava.[107]

Professor Henneberg’s opinions were deemed inadmissible.[108]

Shortly thereafter, a differently configured NSWCCA found Professor Henneberg’s bare similarity evidence, in another conviction involving a well-disguised armed robber, to be admissible.[109] The NSWCCA’s Honeysett v The Queen decision is difficult to reconcile with Morgan. The High Court granted special leave.[110] A unanimous High Court deemed the opinions of Professor Henneberg inadmissible because they were said not to be ‘based wholly or substantially on his specialised knowledge within s 79(1) of the Uniform Evidence Law. It was an error of law to admit the evidence’.[111]

Figure 4: Robber alleged to be Honeysett (top left)

On comparing the crime scene images (see Figure 4) with reference images of Honeysett, the professor purported to identify several similar features, including: somatotype (ectomorphic), height, posture (lumbar lordosis), hair length, skull shape (dolichocephalic), handedness and skin colour (once again the defendant was an Indigenous Australian).[112] The Court’s not entirely helpful explanation of why the comparison and opinions about alleged similarities are not admissible is extracted in full below:

Professor Henneberg’s opinion was not based on his undoubted knowledge of anatomy. Professor Henneberg’s knowledge as an anatomist, that the human population includes individuals who have oval shaped heads and individuals who have round shaped heads (when viewed from above), did not form the basis of his conclusion that Offender One and the appellant each have oval shaped heads. That conclusion was based on Professor Henneberg’s subjective impression of what he saw when he looked at the images. This observation applies to the evidence of each of the characteristics of which Professor Henneberg gave evidence.[113]

This extract exposes a court struggling to provide meaningful explanation for exclusion. All human-based image comparisons will require ‘subjective impressions’ of what is seen.[114] While it is true that anatomical training, study, and experience and even anatomical knowledge may not be of value when engaging in comparisons, their actual value is uncertain — ie unknown. In the terminology from Smith, we do not know if Professor Henneberg’s opinions are relevant.[115] Can he actually do it (better than the jury)? In our terms, the expertise is purported. We are not told about ‘the basis’ of the opinion, the relevant ‘knowledge’, or Professor Henneberg’s actual ability at image comparison for the purpose of identification.[116] While we agree that his opinion(s) should be excluded — for us, because it is purported expertise — the implications of the Court’s reasoning are unclear. Moreover, we cannot be confident that the decision extends beyond anatomists (or this anatomist) or applies in cases where the defendant is not well disguised.[117]

The High Court’s response, like the decisions in Tang and Morgan, is declaratory. Without determining whether the anatomist possesses expertise in comparing persons in images, it simply declares that the opinion is not based on ‘specialised knowledge’.[118] The judgment provides no meaningful guidelines and tells us nothing about what kind of ‘specialised knowledge’ might ground an admissible opinion about identity.[119] The judgment does not engage with similarity constraints or the relationship between knowledge and reliability (which were left open in Tang). Legally, it is unclear what future prosecutors, defence counsel and judges should look for when trying to determine if an opinion is based on ‘specialised knowledge’ (and whether that ‘knowledge’ is based on ‘training, study or experience’).[120] Like the Court in Morgan, the High Court in Honeysett disavowed the need to deal in a principled manner with either the scope of ‘specialised knowledge’,[121] or to address whether there was a place for ad hoc expertise within the framework offered by s 79 of the Uniform Evidence Law.[122]

Compounding problems, courts in Uniform Evidence Law jurisdictions have begun to rationalise the admission of investigators’ opinions — most conspicuously in relation to the identification of persons captured speaking on telephone and other voice intercepts — via the exception for lay opinions: namely, s 78.[123] This approach overlaps with the idea of the ad hoc expert, and enables persons without any ‘specialised knowledge’ or ‘training, study or experience’ to present their opinions about identity (and even the words allegedly spoken and sometimes their meaning) on the basis of listening or repeated listening to a recording.[124] This development is problematic because it has enabled investigators, and interpreters working with them, to express their opinions about the identity of the speaker.[125] The individuals proffering their opinions via s 78 are not directly perceiving the matter or event. No evidence is presented or required to support expertise in voice comparison.[126] They are not required to satisfy the Code of Conduct for Expert Witnesses[127] and, like the ad hoc experts speaking about a POI in images (via s 79), tend to have little if any idea about the difficulty of the task, relevant scientific research, or notorious risks known to specialists.[128] Section 78 does not require knowledge.[129] Revealingly, s 78 witnesses have demonstrated a striking tendency to categorically identify speakers and to maintain high levels of confidence (bearing limited correspondence with studies of general abilities) when cross-examined,[130] for they are not restricted to describing similarities.[131]

The opinions deemed inadmissible by virtue of s 79(1) in Honeysett and Morgan would appear to be admissible by virtue of s 78. By analogy with the interpretation of a voice recording, the anatomist is merely describing what they see, hear or otherwise perceive about a recording of the ‘matter or event’ (though, here a photograph or video) and in the same way that it is said to be ‘necessary’ to receive the opinions of investigators about who is speaking, it would seem to be necessary to receive the opinion of the anatomist about the identity of the POI in the image(s).[132] Ironically, the constraints imposed in Tang, limiting the opinions to similarities and differences, do not apply to opinions admitted according to the exception for lay opinions provided by s 78 and its common law equivalents.[133] Interpreted in this way, s 78 threatens to undermine the requirements imposed by s 79(1). It enables investigators (and others) to testify without having to possess or attend to ‘specialised knowledge’.[134] This sidesteps Kirby J’s reasoning in Smith as well as subsequent authority from

Lithgow City Council v Jackson focused on ‘necessity’ and directness, and constitutes a striking inconsistency.[135] It allows those with little (if any) knowledge, but with purported abilities, to express their opinions in the strongest

possible terms.[136]

Ad hoc expertise tends to be represented as an obvious — even common sense — category.[137] It is, however, incompatible with the express terms of ss 76 and 78–9, as well as their context and purpose. Section 76 covers the field.[138] Section 78 requires the observation to be direct — or it should.[139] Section 79 requires ‘specialised knowledge’ as well as ‘training, study or experience’. Recourse to ad hoc expertise leads to the admission of opinions based on nothing more than repeated exposure represented as either ‘knowledge’ or ‘experience’ (when admitted via s 79) and ‘necessary’ (when admitted via s 78). Ad hoc experts, whether expressing opinions under s 78 or s 79(1) are typically unfamiliar with the accuracy of their opinions, relevant scientific research, or dangers of cognitive bias.[140] They are purported experts. They do not know the value of their opinions.[141]

Problems are compounded by the reluctance to exclude opinions about POIs in images following objections based on s 137 (and s 135). Section 137 requires a trial judge to exclude evidence (of any kind) where its probative value is outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice to the defendant.[142] Authority, specifically IMM v The Queen (‘IMM’), prevents trial judges from considering the reliability of the evidence or the credibility of the witness when undertaking the balancing exercise.[143] This controversial approach applies to forensic science and medicine evidence.[144] Without insight into the value of an opinion or the actual risk of error, trial judges are required to determine the capacity of such evidence — in order to take it ‘at its highest’.[145] Lack of familiarity with scientific research on the difficulty of identifying strangers has enabled judges to routinely find the probative value of opinions to outweigh (unknown)

dangers to the defendant.[146] Judges do not typically consider the opinions of purported experts as ‘weak’ or risky.[147] They have tended to admit opinions on the basis that any weaknesses or limitations will be exposed (and conveyed) by trial safeguards — such as cross-examination and judicial warnings — notwithstanding the fact that these are rarely informed by mainstream scientific knowledge and almost never expose, for consideration, real risks of error

and misunderstanding.[148]

Based on the published decisions, no Australian court has ever required or been presented with information on whether those interpreting images can accurately describe features or identify specific persons.[149] No court has discussed scientific research, (lack of) error rates and related risks associated with unfamiliar face comparison. We do not know whether those allowed to, or those prevented from, proffering opinions have relevant abilities. Instead of focusing on reliability, Australian judges have been distracted by other factors — eg qualifications, experience (including legal experience), and repeated exposure in suggestive conditions — that are secondary to the question of whether the witness has a heightened ability.[150] Thus, Australian courts are curiously inattentive to the only criteria that actually matter: are these individuals really experts at image comparison, how good are they, and where is the evidence (ie ‘knowledge’) that supports the claimed ability?[151]

Courts can draw on three main sources of scientific research to inform decisions relating to face comparison evidence. First, a large body of scientific research conducted since the early 1990s has examined the accuracy of ordinary (or lay) persons at facial comparison (or ‘face matching’ as it is often described by research scientists) and the factors that affect their accuracy.[152] Secondly, in more recent years studies have examined the accuracy of various groups involved professionally in unfamiliar face matching.[153] These groups range from staff performing image comparison incidentally in their daily work (eg nightclub bouncers) to highly trained and experienced specialist facial examiners whose work focuses primarily (and sometimes exclusively) on interpreting images, writing formal reports and (outside Australia) testifying in criminal proceedings.[154] Thirdly, since the 1990s, the accuracy of automated facial recognition systems (ie algorithms) has been rigorously evaluated.[155]

The technicalities of this research sometimes make it difficult to extract the data and findings most pertinent to legal practice. So, in this section, we have provided an overview focusing on the relative accuracy of the different types of individuals and systems that might be called upon to assist with the identification of POIs in images in investigations and criminal prosecutions. Some of the findings we describe are well established — that is, replicated across many studies — but some areas of research are in their infancy. We have endeavoured to address the relative scientific certainty of the various research findings.

Initially it is important to recognise that the accuracy of all sources of face comparison evidence is affected by a variety of factors. Any assessment of identification evidence requires careful consideration of the following sources of variation: (i) how familiar the decision-maker is with the person to be identified; (ii) the quality and quantity of the images relied upon; and (iii) interactions between the demographics of persons in the images and the decision-maker.[156] In the following pages we consider the levels of accuracy that can be expected from different types of image comparison before reviewing the relative accuracy of the different groups and systems.

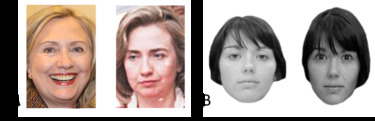

A very important moderator of accuracy in face identification tasks is how familiar a viewer is with the particular face.[157] Humans are generally very good at identifying the faces of individuals who are known or familiar to them.[158] Deciding whether the two images on the left of Figure 5 (‘pair A’) portray the same person will not be particularly challenging for most people reading this article, notwithstanding substantial differences in age, pose, expression, image quality, make-up and distance from the camera.[159] On the other hand, most people find a similar question, about the faces on the right (‘pair B’) to be very difficult.[160] Yet, the two images on the right were taken just minutes apart, under the same lighting conditions, with the same subject-to-camera distance and in similar pose.[161] Around half of those asked (incorrectly) report that these are images of different people.[162]

This example highlights difficulties with the kinds of unfamiliar face matching decisions that are routinely made in courts. It also demonstrates the transformative effect that being familiar with a face has on face identification accuracy. Research shows that the level of familiarity is correlated with accuracy.[163] In studies that have directly compared the identification of familiar and unfamiliar faces by asking subjects to compare still images with CCTV images, performance with personally familiar faces is substantially better (with accuracy around 90%) than with unfamiliar faces (around 70% correct).[164]

Figure 5: Two face matching decisions — do these pairs of images show

the same person or different people? The images in pair A illustrate how

familiarity can simplify the task. Deciding whether the images in pair B

depict the same person (ie ‘match’) is the kind of task presented in

standard face comparison studies.

The level of familiarity with the suspect/defendant is therefore an important predictor of accuracy in face identification by those endeavouring to determine the identity of the POI in images.[165] Significantly, familiars and most purported experts have different types and levels of exposure to the faces they might be asked to identify. Their ‘familiarity’ is usually obtained in quite different circumstances. Familiars are exposed to a face (and a body) across a wide variety of interactions and settings, often over months or years. Think of a school friend, sibling or partner. Purported experts, on the other hand, usually have more limited exposure obtained in less varied conditions. Their exposure might be based on watching videos over radically foreshortened time periods — eg a police interview, the execution of a search warrant or a bank robbery. They may even be limited to studying just a single photo (or frame).[166] A number of studies have shown that identification accuracy is poorer for people who are moderately familiar compared with those who are very familiar.[167] Performance improves from near chance in poor-quality CCTV to high levels of accuracy when the questioned face is familiar.[168] Importantly, familiarity obtained by studying images of unfamiliar faces — akin to the experience of ad hoc experts and others involved in the investigation (ie investigative familiars) — provides relatively meagre benefits.[169] Ad hoc experts are not genuine familiars.[170]

In addition to the amount and kind of exposure it is also important to consider the length of time that has passed since a familiar last encountered the person in question.[171] Familiarity with faces fades with lack of exposure.[172]

Another key factor influencing face matching accuracy is image quality. One would hope that this is already taken into account by courts, as common sense suggests that identification decisions from poor-quality images are unlikely to be reliable. The cases we reviewed in Part II suggest that this limitation has not received appropriate consideration. Australian courts admit low-quality images (eg in Tang) and images of well-disguised individuals (eg in Morgan and

Honeysett), leaving the central issue of identity to the jury.[173]

Decades of research on the accuracy of unfamiliar face matching confirms that performance is dramatically reduced by low-quality images.[174] When identifying people from images and videos, accuracy is moderated by environmental and image capture conditions such as image resolution, camera position, occlusion of the face (eg from a disguise, hat, glasses, injury, or hair), lighting, and subject-to-camera distance.[175] Accuracy is also affected by changes in appearance caused by factors relating to the face: for example, expression, ageing, weight change or surgery, and head angle.[176]

The potentially detrimental effect of image quality factors on performance is not limited to lay persons. The accuracy of facial examiners and algorithms (more below) is also impaired by degradation in image quality.[177] Interestingly, Kristin Norell et al showed that specialist facial examiners were better able to moderate the confidence of their judgments based on the quality of the image evidence than lay persons.[178] When image quality was poor, facial examiners were more likely than students (ie those without training and socialisation) to use the ‘unsure’ response option in their assessment of whether faces ‘matched’.[179] Courts (and decision-makers) should expect expert witness reports to be accompanied by a careful assessment of image quality factors that constrain the type and strength of conclusions available. We should note that while the accuracy of facial recognition algorithms is markedly impaired by reduction in image quality, the current generation of ‘deep learning’ algorithms appears capable of accommodating some degree of variation in head angle and image quality.[180]

Face matching accuracy is also influenced by the number of images available for comparison.[181] Research shows that the provision of two reference images rather than one results in a slight improvement in accuracy, up to 7%, particularly when the images being compared depict the same person.[182]

Another important consideration is the interaction between the demographic profiles of the person pictured in the image(s) and the person (or algorithm) making the face identification decision. An example of such an interaction is the phenomenon known as the ‘other-race effect’.[183] We are typically better at identifying faces that share our ethnicity than faces of different and less familiar ethnicities.[184] This effect has been replicated in many studies, most of which test the ability of people to remember faces.[185] In a review of this literature,

Christian Meissner and John Brigham found that across 39 studies and nearly 5,000 subjects, people were 1.4 times more likely to recognise own-ethnicity

compared to other-ethnicity faces.[186]

While the vast majority of studies demonstrating the ‘other-race effect’ have used tests of memory,[187] a small number have examined other-race effects in simultaneous matching tasks — like those in Figure 5B above. It is important to know whether race influences simultaneous matching because the decisions made by people admitted as some kind of expert (as opposed to eyewitnesses and familiars) do not typically rely on memory. The individuals undertaking comparisons have simultaneous access to two or more images. The limited evidence available suggests that performance is poorer where the ethnicity of the POI is different to the ethnicity (or experience) of the decision-maker.[188]

Ethnicity is not the only demographic factor warranting consideration. Other studies have shown participants to be better at identifying faces from their own age group.[189] Indeed, prominent theoretical accounts of both the ‘other race’ and ‘own age’ effects propose that they have a common perceptual basis.[190] Proponents argue that our relative ability is driven by our perceptual expertise with specific groups.[191] Because perceptual expertise is derived from our experience, we are more adept at recognising and distinguishing the types of faces that we encounter often in our daily lives — and these tend to be people who share our demographic profile.[192]

Interestingly, research suggests that the accuracy of face recognition algorithms is influenced by the demographics of the datasets used to ‘train’ them.[193] For example, P Jonathon Phillips et al tested the accuracy of algorithms

submitted to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (‘NIST’) Face Recognition Grand Challenge benchmarking exercise.[194] Algorithms developed in East Asian countries performed better on East Asian faces and

algorithms developed in Western countries performed better on Caucasian faces — thereby mimicking the other-race effect observed in human participants.[195] This differential accuracy is thought to be because the East Asian

algorithms are trained on predominantly East Asian faces, and the Western algorithms are trained on predominantly Caucasian faces.[196] Current state-of-the-art deep learning algorithms also show differential accuracy for different ethnic groups.[197]

Importantly, it is currently unknown whether these effects occur in genuinely expert groups, such as facial examiners and super-recognisers[198] (on these groups, more below).[199]

Now we turn to describe scientific research on the accuracy of face comparison and identification. We want to indicate at the outset that the divisions (or ‘groups’) we have employed are not always neat; nevertheless, they provide an indication of relative abilities as well as the need to attend to the formal testing of individuals rather than relying on proxies such as job title (or other nomenclature), reputation, experience, training or formal qualifications. The review begins with lay persons. We include those we have described as purported experts (eg ad hoc experts, investigators and reviewers) in this discussion for, as we shall see, the available evidence suggests that they do not typically outperform lay persons.[200] We then consider individuals who have consistently demonstrated superior performance in some tasks and conclude our overview with the latest algorithms (employing artificial intelligence) and new types of hybrid systems.

The accuracy of lay persons (or novices) in unfamiliar face matching tasks is surprisingly poor.[201] When lay persons are given unlimited time to complete face matching tasks that require them to determine whether two photographs depict the same person (as in Figure 5B), error rates range from around 20% with high-quality standardised images to 30–40% in more challenging tests where images are captured in unconstrained environmental conditions — eg from CCTV cameras or photographs taken from social media such as Facebook.[202] For a variety of reasons, including the general lack of feedback in everyday life (in relation to unfamiliar persons), most of us are oblivious to the error-prone nature of unfamiliar face comparison.[203]

In recent years, attention has turned from testing the accuracy of lay persons towards testing professional staff who perform face comparison tasks as part of their daily work.[204] These staff range from ‘reviewers’ — those who compare images (or images with persons) as a component of their work — to specialist ‘facial examiners’ — whose primary work involves image interpretation.[205] Reviewers are responsible for confirming the identity of persons, such as those checking documents at national borders, issuing passports, as well as some police officers and security personnel (eg nightclub bouncers). At the other end of the spectrum are specialists engaged primarily, sometimes exclusively, in the interpretation of images for the purpose of identification. These facial examiners have usually spent many years acquiring their skills, often in boutique law enforcement environments.[206] There is now a relatively large scientific literature comparing the performance of these professional groups — ie reviewers and facial examiners — to lay persons.[207] A key insight from this research is that merely performing the task of face comparison in daily work does not improve accuracy — see Figures 6 and 7 below.[208] That is, experience — merely doing the same thing over and over, such as routinely comparing photographs in passport applications or comparing photographs with applicants at national borders — does not improve accuracy.[209]

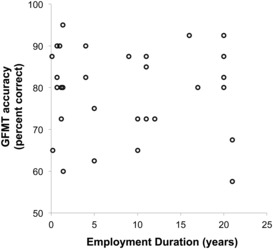

In a recent meta-analysis of published tests of unfamiliar face matching performance, on 12 out of 18 tests, reviewers — those who perform face comparison as part of their daily work — performed no better than lay persons.[210] The reviewer groups included staff with titles and roles that might reasonably lead people to expect them to possess genuine abilities in face matching.[211] A test of Australian passport officers, for example, found no correspondence between length of employment and accuracy at face matching.[212] Staff who had been employed as reviewers for decades were no more accurate than those employed for just months (see Figure 6) and passport officers were no more accurate than university students.[213] This finding also extends to memory-based face identification tasks.[214] A review of experimental evidence comparing the accuracy of police officers and lay persons at identifying suspects from line-ups revealed no difference between these groups in five of seven studies.[215] Together, this evidence shows that professional role and experience in face identification tasks are no guarantee of enhanced ability — ie expertise.

Figure 6: Passport officers’ accuracy on a standard test of face matching ability (Glasgow Face Matching Test (‘GFMT’)), plotted against years of experience. Each dot represents a passport officer. Accuracy does not improve

with experience.[216]

The fact that experienced reviewers perform no better than persons without experience also raises questions about the value of training.[217] Alice Towler et al tested reviewers before and after they received professional training in face comparison.[218] The courses reviewed promoted detailed analysis of facial features, instruction on facial features, and components of features (eg the tragus, helix, antihelix, and lobe of the ear). The content tended to be consistent with international recommendations — eg the best-practice guidelines set out by the Facial Identification Scientific Working Group (‘FISWG’).[219] Nevertheless, Towler et al found little evidence that formal training improves performance.[220] This suggests that training (like experience) does not simply manifest in a heightened level of ability — ie expertise.[221]

By now the reader should be increasingly sensitive to the value of formally evaluating performance — in order to generate knowledge of abilities and accuracy — rather than assuming the existence of expertise on the basis of ‘training, study or experience’ or imputing ‘knowledge’. In investigations and criminal proceedings we should expect (and be presented with) empirical evidence of the actual performance of persons said to be expert and algorithms said to be accurate.[222]

Fortunately, individuals and algorithms with genuine abilities are (now) known to exist.

In their recent review of tests that compared the accuracy of professional groups to lay persons, David White, Alice Towler and Richard Kemp found that facial examiners — specialists who are primarily engaged in image interpretation — consistently outperformed lay persons and reviewers (such as passport examiners).[223] Facial examiners are typically employed by government departments (eg the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade) or policing agencies (eg the Federal Bureau of Investigation) and spend most, sometimes all, of their time interpreting images.[224] They are routinely involved in making decisions about the identity of POIs and may spend hours, days or even weeks on particular comparisons. Examiners often provide written reports that explain the bases for their identification decisions and in some jurisdictions (though not currently Australia) submit these reports to courts and, if required, provide expert testimony. In the seven tests conducted so far, facial examiners consistently outperformed lay persons.[225] These differences were typically large, ranging from 10% to 20% higher accuracy.[226]

Facial examiners as a group have demonstrated the kind of enhanced ability conventionally associated with expertise.[227] However, the number of studies is modest.[228] The small number of tests conducted so far use images of ‘compliant’ subjects looking directly at a camera, in relatively good lighting and with good resolution (as in Figure 5B).[229] Scientists are yet to conduct systematic tests of the effects of image quality factors on the performance of facial examiners. However, preliminary evidence suggests that image quality will be as detrimental to their performance as it has been to the accuracy of lay persons.[230]

Importantly, the tests conducted so far reveal large inter-examiner variation.[231] That is, there are substantial differences between the performances of different facial examiners. While facial examiners perform very well as a group (in comparison to other groups such as reviewers and lay persons), some individual facial examiners perform poorly.[232] The results from the initial studies should not be extrapolated to all of those who are, or claim to be, facial examiners. In the largest test conducted so far, Phillips et al found that the performance of individual facial examiners spanned the entire range of the measurement scale — from near chance level (ie 50% — expected from guessing) to perfect accuracy (ie 100%).[233] Revealingly, seven of 57 facial examiners made errors in more than 30% of their comparisons.[234] All of the examiners tested were members of internationally respected scientific working groups and they were allotted three months to complete 20 same–different face matching decisions — the type of task depicted in Figure 5B.[235]

Figure 7: Face identification/matching accuracy of forensic examiners, reviewers, super-recognisers and algorithms. Small black dots denote one person’s/algorithm’s performance, and large dots denote group medians. The white ‘violins’ denote the distribution and density of scores. The black dotted line indicates the performance of 95% of students, such that scoring above this line indicates a person performs better than 95% of students. The most recent algorithms — the years of development are included in their titles — performed as well as the very best humans.[236]

The studies reviewed by White, Towler and Kemp provide evidence that some professional groups attain levels of accuracy that would seem to satisfy admissibility criteria concerned with genuine expertise or knowledge. However, the preliminary nature of these studies means that caution should be exercised when applying the group findings to any specific individual who might be presented as an expert witness.[237] It seems important to have a clear idea of individual performance — based on standardised testing in controlled conditions — rather than to extrapolate from the average performance of groups, job title, training or years of experience. Demonstrable personal ability would seem to be an essential prerequisite for admission, reliance and comprehension.[238]

Relatively recently, while studying prosopagnosia (ie face blindness), scientists identified a group of individuals whose abilities might provide an alternative (or supplement) to facial examiners.[239] These are individuals who seem to have a natural aptitude for face matching. In the scientific literature and the media they have been labelled ‘super-recognisers’.[240] They represent the very top end of a naturally varying continuum of face identification ability across the general population. A large body of evidence confirms there is substantial variation

between people’s abilities in face comparison tasks.[241] This variation is ‘relatively stable across repeated testing’.[242] Recruiting and selecting forensic

practitioners on the basis of their innate face matching ability is therefore a promising way to improve the accuracy of face identification decisions made in

professional settings.[243]

With the discovery of variable performance across the general population, in conjunction with the outstanding performance of a handful of police officers reviewing CCTV images following the London riots in 2011, London’s Metropolitan Police Service (‘Met’) established a ‘super-recogniser’ team in 2013.[244] This team seems to have been an amalgam of those who identified persons with whom they were familiar from localities in which they worked (eg custody officers and local police who identified recidivists) and/or those who performed well on standardised face matching and face memory tests (eg the GFMT and the Cambridge Face Memory Test).[245] Notwithstanding the large number of studies showing variation in face matching tasks across the general population, few studies have tested professional groups of super-recognisers.[246] The only evidence comes from two studies comparing the accuracy of super-recognisers employed by the Met with untrained novices.[247]

Josh Davis et al tested 36 Met super-recognisers on a standard face matching test.[248] Super-recognisers outperformed university students on this test by six percentage points.[249] In a similar study, David Robertson et al tested four super-recognisers from the Met on the same test and found they outperformed police trainees by 17.8%, and outperformed a control group of university

undergraduates by 22.7% and 27% on two other challenging face identification tasks.[250] It is not entirely clear why this group of four performed so much better than the group of 36, but we suspect these four super-recognisers were a subset of the staff tested by Davis et al, and were selected to form an elite team on

the basis of on-the-job performance in conjunction with high scores on

standardised tests.[251]

Exactly how super-recognisers achieve such high levels of accuracy is not yet clear — super-recognisers were only ‘discovered’ in 2009.[252] Since that time, researchers have tended to focus on verifying their superior ability rather than studying how they achieve it.[253] Consequently, we do not yet understand how such accurate identification decisions are produced.

Of interest, preliminary evidence suggests that super-recognisers lack

the conservatism of facial examiners.[254] That is, they are more likely to make errors with high levels of confidence.[255] This aspect of performance may follow from being asked questions about whether faces match in ways that are

quite abstract. Facial examiners, in contrast, are more likely to be sensitive to forensic uses and institutional values — including the risks of overstatement

and error.[256]

The use of deep learning has improved face recognition algorithms dramatically in recent years.[257] The accuracy of these algorithms has reached the stage where they are superior to the average lay person in making unfamiliar face matching decisions.[258] In a recent comparison between algorithms, facial examiners, reviewers, super-recognisers and lay people, Phillips et al found that algorithms perform just as accurately as the best performing humans (ie facial examiners and super-recognisers).[259] In this particular study, ‘participants’ were required to determine whether sets of two photographs depicted the same or different persons.[260] The most reliable algorithm (A2017b) was 96% accurate.[261] On average, facial examiners were 93% accurate and super-recognisers were 83% accurate.[262] All three groups — algorithms, facial examiners and super-recognisers — outperformed lay people, comprising fingerprint examiners (76%) and students (68%).[263] However, algorithms and super-recognisers were much faster than facial examiners.[264]

Figure 7 illustrates fundamental information about the performance of different groups in a way that helps us understand the value of their interpretations. Small black dots denote the accuracy of a single person/algorithm, and the large dots denote average performance of each group. Such studies provide the kind of knowledge that should inform decisions about the admission and use of images as well as the probative value of opinions about images for purposes of identification. It provides a clear indication of the types of face matching opinions that tend to be (most) probative, while also providing an estimate of the degree of variance in accuracy that can be expected within each of these types.[265] Courts, as we explain below in Part IV, should be primarily focused on those whose superior abilities with face comparisons have been empirically demonstrated. These are largely found among facial examiners and super-recognisers, along with the increasingly sophisticated algorithms.

Up until this point we have discussed the performance of various humans and face recognition algorithms in isolation. However, in most ‘real-world’ settings face identification decisions are made by hybrid systems, in which humans and algorithms (usually software) work in combination.[266] For example, face recognition software is most often used to search large national image databases (eg of criminal mugshots or drivers’ licences) to find faces that look most similar to a photograph of a POI.[267] A human analyst must then interrogate the search results to decide if the POI is present.[268] Studies confirm that combining humans and algorithms in this way drastically increases errors.[269] White et al found that passport reviewers — those who perform this very task as a component of their daily work — made errors more than 50% of the time when adjudicating the output of face recognition software.[270] This high error rate is an unintended consequence of face recognition software finding the most similar faces in a database containing millions of images.[271] The faces presented to the human analyst are often extremely similar.

Empirical research reinforces the need to carefully design hybrid systems based on known abilities and procedures that reduce the risk of error. One particularly effective method of improving accuracy is to employ the ‘wisdom of crowds’ or fusion.[272] In these systems humans and algorithms work in parallel rather than serially, as described above. Humans and/or algorithms each make independent decisions which are then aggregated, usually by averaging the scores, to produce a single ‘group’ decision.[273] The group decision is often more accurate than any of the individual scores that produced it.[274] Phillips et al recently demonstrated that combining the decision of a single facial examiner and the best available algorithm often resulted in perfect performance.[275] Together, these findings illustrate the critical importance of designing evidence-based face identification systems — get it wrong and the results are catastrophic, but get it right and the results are highly accurate and hugely beneficial to fact-finding.

One of the benefits of these hybrid systems is that risks from many biases can be managed and/or dispersed.[276] Additionally, humans and algorithms can be tested on image pairs where the correct answer (ie ground truth) is known.[277] This testing can be imposed so that the persons involved in comparisons do not know that any particular task is a test.[278] It can appear to be part of their routine flow of work. Such testing provides very useful information about the performance of the system. With both algorithms and hybrid systems we can obtain and provide useful information about their accuracy in conditions similar to those in the investigation or prosecution.[279] This information can be provided to those considering admission and evaluating the outputs.

Algorithms and hybrid systems will introduce new questions: whether the output should be treated as opinion evidence and/or who should be called to explain or account for the output.[280] These are not necessarily novel questions, but in responding, courts should be aware that even if humans are involved in decision-making — whether as a facial examiner using an algorithm as a preliminary search tool or a hybrid system that combines the performances of multiple algorithms and/or humans — it may be desirable to receive a report from, and have questions about the system and limitations addressed by, those who understand how it works. These individuals may not possess special abilities in face comparison and are unlikely to be involved in decisions about whether faces are believed to match (or not). Rather, they are a kind of meta-expert. They are capable of explaining the system, the results and the way the results are expressed (based on statistics), in a way that the individual decision-makers — whether facial examiners, super-recognisers, or algorithms — typically cannot.[281]

Following this review of scientific research, Tang, Honeysett and IMM seem, to put it mildly, inadequate. There appear to be deep, and perhaps structural, impediments to common law legal institutions productively engaging with mainstream scientific knowledge.[282] These impediments seem pronounced in criminal proceedings.[283] Our courts have placed reliance on legal tradition, judicial experience, and case-based reasoning. They focus attention on legal metaphysics (around fact and opinion) and vest confidence in rules of evidence and procedures, trial safeguards and jury decision-making.[284] Yet, jurisprudence and practice seem insensitive to pertinent scientific research on the actual performance of those allowed to proffer opinions, as well as the abilities of jurors.[285] None of the research discussed in Part III has been cited in a published legal decision.[286] Scientific knowledge does not appear to have informed the interpretation of rules or the operation of criminal procedures and trial safeguards said to be part of our rational tradition of proof.[287]

At this juncture it is our intention to draw attention to 10 issues that arise from the foregoing reviews. Some of these points are straightforward, others require wholesale reconsideration of not only our admissibility jurisprudence, but some of the assumptions and procedures associated with our courts’

rather cavalier approach to admitting and using images to identify POIs in criminal proceedings.

First, we need to accept that image interpretation is difficult and surprisingly error-prone.[288] When it comes to strangers, we humans regularly make mistakes even in favourable conditions with high-quality images.[289] Furthermore, unfamiliar face matching is not something that we often engage in, and we rarely receive feedback on the accuracy of our unfamiliar face matching abilities.[290] As a result, we dramatically underestimate the difficulty of the task and the number of mistakes we make.[291] We should not assume, therefore, that comparison and identification are tasks that the jury can somehow manage or that trial safeguards or the other evidence will operate as correctives. Decades of scientific research on human cognition confirm that contextual information (whether the opinion of a purported expert or other evidence, such as a motive), and even legal procedures themselves (eg production by the prosecutor and the fact of admission which both imply evidentiary value), are likely to bias the perceptions of those earnestly trying to compare and identify POIs in images.[292] There is, in addition, no evidence that non-independent groups (eg

jurors deliberating in common) avoid these vulnerabilities.[293]

Secondly, we should treat the evidence of anyone who is identifying a person on the basis of images as opinion evidence.[294] (This includes eyewitnesses, although this article is not substantially engaged with this type of evidence.)[295] It does not matter if this evidence is from a spouse of 50 years or a complete stranger.[296] We should abandon classifying some interpretations as ‘fact’ or ‘direct’ or ‘recognition’ evidence to avoid the implications of all identifications being opinion (and subject to s 76 of the Uniform Evidence Law). Identifying persons in images, however quick or intuitive, is always interpretive.[297] It is always opinion, though we now know that some of these opinions are markedly more reliable than others.[298]

Based on available scientific research and our shared experience, there should be an exception to s 76 for the opinions of non-investigative familiars (where that familiarity is derived from pre-investigative contexts and quotidian interactions over time and across a variety of settings). Such familiars are more accurate than investigators and more accurate than jurors, juries and judges.[299] If the opinions of non-investigative familiars are not clearly accommodated within the existing exceptions to s 76, then a new section should be created for them. As drafted, ss 78–9 are poorly suited to this class of indirect witness.[300] Notwithstanding recent attempts to expand its application to displaced viewers and listeners, this is not an answer to the gap in relation to non-investigative familiars. Section 78 should only confer an exception on those who directly perceived a ‘matter or event’ — such as ear- or eyewitnesses.

There are compelling reasons for receiving the opinions of those who directly perceive a matter or event (eg eyewitnesses) as well as non-investigative familiars. The opinions of eyewitnesses will often be ‘necessary’. The opinions of genuine familiars are probative because of their enhanced ability, as a class of witness, relative to jurors.[301] This is not an ability that jurors are likely to acquire during the course of proceedings.[302] Persons who do not satisfy these conditions are not direct witnesses and should only be able to proffer opinions if they possess demonstrable abilities — they can testify via s 79(1).

This brings us to the third point. It concerns the reliability of opinions said to be based on ‘specialised knowledge’ admitted in the context of a trial. Any individual who testifies about the identity of a POI as an expert should — regardless of whether they describe similar features, speak probabilistically, or categorically identify — be demonstrably better than ordinary persons (eg jurors). Procedures and proficiency should have been formally evaluated so that the individual’s abilities are known, disclosed and able to be considered.[303] For feature comparison forensics, we should not rely on legal tradition, past practice, job titles, self-serving claims, popular beliefs, plausibility, or weak admissibility traditions as proxies for expertise.[304] We should not (have to) assume that persons presented as experts possess genuine abilities.[305] Relevance (and probative value) should not be left to what individual juries might ‘accept’, nor should it be taken at some speculative ‘highest’ value.[306]

Where the images are of reasonable quality, facial examiners, super-recognisers and algorithms consistently transcend the performances of ordinary persons.[307] Their opinions and outputs should be obtained and admitted.[308] Where images are of low quality, as in Tang, or POIs are well disguised, as in Honeysett, we do not currently possess reliable means of identification.[309] That is, there are no relevant experts. Any opinions and outputs are speculative — they are not based on knowledge. This is a lacuna that jurors cannot be expected to fill. As noted above in our first point, they are ill-suited to undertaking such demanding face comparisons, especially in suggestive conditions.[310] We should not expect jurors to do what genuine experts cannot.[311]

Fourthly, the opinions of an individual admitted as an expert should always be accompanied by the best estimate of accuracy based on the results of formal empirical evaluation — whether validation studies or rigorous proficiency testing.[312] That is, we should know about the particular individual’s performance.[313] Expert opinions should be presented with an indication of the risk of error based on the individual’s performance in (roughly) similar conditions.[314] There is limited value in allowing the bare description of features or categorical identification if decision-makers are not presented with some idea of the witness’s ability at the specific task.[315]

Fifthly, any algorithm relied upon in criminal proceedings should have been rigorously evaluated in (roughly) similar conditions. Issues of race, age, the quality and quantity of the images, the role of individuals in the operation of the system, indicative error rates, and so on and so forth, should all be considered and, where appropriate, addressed. Accuracy, limitations and other risks should be proactively disclosed in reports (and in testimony).[316]