|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Precedent (Australian Lawyers Alliance) |

NOT SO SUPER, FOR WOMEN: SUPERANNUATION AND WOMEN’S RETIREMENT OUTCOMES

By Warwick Smith and David Hetherington

The women we spoke to were blunt about their outlook...

“I will be stuffed.”

“I expect to be poor.”

Sadly, the evidence suggests that many of them will be proven correct.

INTRODUCTION

Superannuation has become a lightning rod in Australian political debate in recent years. The universal superannuation guarantee system started 25 years ago as just one pillar of Australia’s new retirement income system. However, it has since become so large, so complex and so lucrative that it is difficult to marshal the various stakeholders towards substantial reform, allowing only tinkering around the edges. And while it remains ‘just’ one pillar of the system (alongside the age pension and private savings), its size and growth has meant that it remains a dominant theme in public debate.

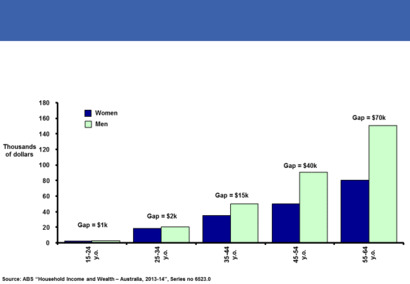

This debate often misses a fundamental problem: that the superannuation system is systematically biased against half the population. The superannuation system is not supporting most women towards a reasonable standard of living in retirement. Women’s superannuation balances at retirement are 47 per cent lower than men’s. As a result, women are far more likely to experience poverty in retirement. Superannuation is systematically failing women.

Figure 1. Median Australian superannuation account balances by age bracket and gender (2013-14).

At one level, the reasons are obvious. Superannuation was designed around a model of employment that is rapidly disappearing. In this model, household income was provided by one breadwinner, usually a man, via a job that was full-time, long term and dependable. Implicitly, the benefits of superannuation were anticipated to flow to women largely through their male partners. This presumption is based on an antiquated understanding of social and economic societal structures. Since the system was established, many more women have entered the workforce to earn and save independently, but the nature of work available to them has often been more intermittent and lower paid than that of their male counterparts. This, combined with the fact that women still do the overwhelming majority of unpaid housework, caring and parenting, means that the benefits of super, which move in direct proportion to pay, have not flowed to female recipients as hoped.

Sadly, and unnecessarily, women’s retirement income in Australia has taken on the features of a wicked problem. It arises thanks to a confluence of diverse circumstances: an inadequate age pension, over-representation of women in lower-paid occupations, the (increasing) gender pay gap, no super at low pay levels, high effective marginal tax rates, carer responsibilities, unpaid domestic work, the complexity of the super system and frequency of changes to it, age discrimination, unaffordable housing, longer lives, poor financial literacy, cost and availability of childcare, relationship breakdowns and casualised work.

We took a two-pronged approach to examining this problem. The first was to ask women for their experience and opinions about superannuation, and the second was to examine the available data on superannuation, looking at men and women with and without children.

WOMEN’S VIEWS ON SUPERANNUATION

Surveys conducted by the Australian Services Union as part of this research provide an insight into Australian women’s views on superannuation.

Prospects for retirement

There is a strong and widely held view among women that they are being severely let down by Australia’s retirement income system. Despondence about their future financial circumstances is a persistent theme, and many women see poverty as an unavoidable part of their future.

“...I expect to be poor. I may become functionally homeless...”

“...Poverty looms for previous middle-of-the-road people no matter how hard they work...”

Women believe this will have direct consequences both for their working future and their ability to afford items that give them quality of life.

“...I think I will need to work until I’m 120 to be a comfortable and self- funded retiree...”

“... I live alone with my dog. My dog is old and I probably won’t have her much longer. I would not be able to afford to keep another dog, so it will just be me, a very lonely life...”

Systemic bias against women

Women do not believe these outcomes are unintended consequences of the superannuation system. Instead, they believe the system is unfairly stacked against them.

“...The pollies want pensioners to fall into a pine box at 70 but they’re on great pensions. We’re expected to become invisible. How should people be expected to work hard when they’re 70? It’s stupid!...”

They feel that the system disproportionately favours men and the rich, and that it is deliberately ‘geared’ to do so.

“... OMG, I could go on forever! Women continue to be financially penalised across our lifetime because of our reproductive capacity, our lower wages and because of deadbeat dads who refuse to pay their share of the financial burden of raising their children (not all dads are like this but, by God, there’s a lot of them). We are expected to provide millions of $ worth of cleaning, caring and emotional labour duties without expecting anything in return, simply for ‘love’. Well, bollocks to that. I would like to see what would happen if we followed Iceland’s lead and went on strike en mass [sic]...”

“...utterly ridiculous system is geared to assisting those who are already very well taken care of...”

Superannuation and relationships

One of the main sources of retirement poverty for women is the breakdown of relationships. As the title of a recent Senate Economics References Committee report suggests, ‘a husband is not a retirement plan’.[1] Women believe that in cases of separation, male partners inevitably end up better off.

“...I can’t afford to contribute to my own superannuation, can’t afford to take holidays, nor can I take extra paid leave as I live pay to pay. There are many like me who, after a mid-life divorce, accepted extra in the equity of their home so that the children were not disturbed rather than a share of his super. My husband had a for-life government pension which, after 20 years of support, I could not make a claim on. I maintained the home and full-time care of our child while he went off-shore and earned big tax free dollars. He now lives on a luxury yacht and travels regularly while I live from pay to pay. Thanks for listening!...”

As a result, some women report feeling uncomfortably dependent on their relationships.

“... I am stuffed if my partner decides to leave me ...”

One under-explored consequence of such situations which was not directly identified by our survey respondents, but is worthy of consideration, is whether women feel compelled to remain in abusive relationships for reasons of financial dependence. As our understanding of the prevalence and causes of domestic violence increases, it is clear that financial dependence is a factor in increasing the risk of violence, and of women remaining in abusive relationships.

Taken together, the qualitative responses from women express great dissatisfaction with a system that is not serving their retirement income needs. Specifically, they feel that:

• poverty is a realistic expectation in retirement for many women;

• the structure of superannuation puts them at a systematic disadvantage relative to men and the wealthy;

• women experience excessive dependence on male partners in matters of retirement income, and that relationship breakdowns are a leading cause of retirement poverty; and

• many women lack a basic understanding of the retirement income system and that more should be done to improve their financial literacy.

We now turn to a quantitative analysis to assess how well these sentiments are borne out by the survey data.

THE CAUSES OF THE GENDER SUPER GAP: A ‘WICKED PROBLEM’

As outlined in the introduction, women’s retirement income in Australia has taken on the features of a wicked problem. The diverse factors which combine to create this intractability are shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. A wicked problem.

*Effective marginal tax rates

The structure of superannuation is an important underlying cause of this problem. Because superannuation contributions are a direct function of income levels, the gender pay gap ensures that women’s balance will systematically be lower for as long as the gender pay gap exists. The most recent data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) indicates that women’s pay rates for equivalent work are 10 per cent lower than men’s, and women’s total pay across the workforce (adjusted for fewer hours worked) is 31 per cent lower (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Ratio of non-managerial female to male pay in Australia: pay rate and total earnings (2014).

What’s more, superannuation is predicated on the fact that every worker is an employee. But the rise of non-standard work means that almost a quarter of female workers (23 per cent) are not in a traditional permanent employment arrangement. Instead, they are casuals, contractors, subcontractors, labour-hire workers, self-employed or on zero-hours contracts. In all of these arrangements, superannuation is less likely to be paid. Women are over-represented in the industries where these forms of precarious work are most common, with the result that the growth of these forms of work hits women’s retirement incomes hardest.

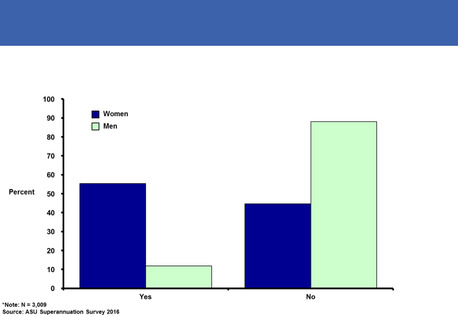

Another contributing factor to women’s lower balances is that they tend to spend less time in the workforce than men, and therefore have less opportunity to contribute to superannuation accounts. In part, this is because of their caring responsibilities, either for children or other relatives. Among our survey respondents, over 55 per cent of women had experienced periods out of the workforce to care for family members. By contrast, less than 12 per cent of men had taken time off for similar reasons (see Figure 4). Not only do far more women take periods out of work to care, but they are away from the workforce for far longer when they do. Two-thirds of men who take time out are away from work for less than one year, but only one-fifth of women take so little time away.

Figure 4. "Have you had periods out of work to care for children or other relatives?"

Clearly, superannuation is determined by salary over a lifetime. Women’s salaries are, on average, lower than men’s,[2] therefore they will accumulate less superannuation. In fact, superannuation amplifies the problem of gender pay inequality by compounding the gap over the course of a working life.

THE MOTHERHOOD GAP AND THE FATHERHOOD PREMIUM

In almost every aspect of the gender pay gap and the superannuation gap we find that being a parent is negatively associated with women’s pay and super while it is positively associated with men’s pay and super. When couples have children, the woman usually takes more time off work than the man and she is also more likely to return to part-time work than full-time. The point in a woman’s life that she takes out of the workforce for maternity leave (usually in her 20s or 30s) can cause a gap in super balances that increases exponentially as super balances increase. By contrast, fathers are more likely to be full-time workers than men who are not parents. That said, even when women do return to full-time work, they earn less than men and less than women who do not have children. Traditional gender roles within the family are still very much in place in modern Australia.

There has been a substantial focus on the motherhood gap in other OECD countries but it has been given relatively little attention in Australia. One of the explanations for the motherhood gap in Australia is the very steep effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs) faced by second earners with children as a result of the withdrawal of family tax benefits.[3] Unlike personal income tax, family tax benefits are assessed on household income. This means that a parent returning to work who has a partner already working full-time is likely to see family tax benefits decline with every dollar they earn. If childcare is required for the mother to work, and we consider that part of the EMTR, then the rate can be over 70 per cent. In other words, circumstances exist where mothers who return to work can end up with less than 30 cents for every dollar they earn in their pocket.

All of these factors add up to create a substantial motherhood superannuation gap (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Median superannuation balances - parents and non-parents by age bracket.

Part-time work

A far greater proportion of women work part-time than men (see Table 1). This is clearly a very substantial factor in determining the superannuation gender gap as fewer hours means less pay and less superannuation.

|

|

Median hours worked

|

Percent part-time

|

|

Male parent

|

40

|

12

|

|

Female parent

|

32

|

52

|

|

Male without children

|

40

|

21

|

|

Female without children

|

38

|

28

|

Table 1. Median hours worked and per cent part-time: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey.

Disentangling causes from effects in these situations is very difficult. Are women less likely to be in management positions because many mothers choose part-time work to balance family responsibilities and management positions are primarily full-time, or are management positions primarily full-time because they are male-dominated?

The gender pay gap

Because most people’s superannuation balances are almost entirely determined by their compulsory contributions based on a percentage of their salary, the superannuation gap is, largely, the result of the gender pay gap.

The gender pay gap takes multiple forms: women are paid less than men for doing the same work; women are less likely to be in high level (and therefore highly paid) positions than men in many industries and occupations; and women are more likely to work part-time than men.

These three different factors are often rolled into one when figures are reported on the gender pay gap.

Analysis of the 2015 HILDA Survey data highlights the importance of motherhood in explaining the gender pay gap. Mothers have lower salaries than women without children, and lower than men without children. By contrast, fathers, on average, have the highest salaries of the four groups. This is true even when we only consider full-time salaries (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Full-time salaries (2015) – parents and non-parents by age bracket.

Many more women are part-time workers, including both casual and permanent part-time, than men and, as discussed above, more women take time out from working and take longer breaks from employment than men. These factors combine with lower rates of pay and the over-representation of women in lower paying jobs to explain a large proportion of the superannuation gender gap.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

Australia remains a profoundly gendered society, both professionally and domestically. If we are to reform superannuation so that it serves both genders equally, then we must either fundamentally change society to remove gender discrimination, equalise unpaid domestic and care work and the raising of children, or we have to create targeted interventions that assist those impacted by those factors. While society-wide transformation for gender equity is a worthwhile long-term pursuit, it’s beyond the scope of this paper.

We do not believe that targeting interventions to all women is a good idea, as it will also direct public resources to some women who do not need them. Given that many of the causes of the gender superannuation gap are a result of parenting commitments, targeting women specifically would also create a disincentive for fathers to take on the role of primary carer.

Therefore, we recommend monitoring superannuation balances to identify those who are tracking below a pathway that will result in a reasonable standard of living in retirement. This ‘accumulation pathway’ can be used as a guide for the implementation of progressive superannuation measures and interventions throughout the life course, including top-up payments, fee concessions, and tax concessions. In addition, superannuation guarantee payments should be extended to all paid parental leave schemes provided by employers and governments and caring payments, including Family Tax Benefit Part B.

Superannuation tax concessions should be reformed so that they benefit low-income earners. Current concessions are heavily biased towards high-wealth, high-income individuals and, as a result, benefits are skewed towards men.

We also believe that reform is needed in the broader tax and transfer system to reduce the excessive effective marginal tax rates faced by earners returning to work after having children. The effective marginal tax rate of 70 per cent is unacceptable and ultimately unsustainable if superannuation equality is to become a reality.

Workplaces need to be made more family friendly and flexible and workplace culture needs to shift so that it is more acceptable for men to take time off work or to work part time to care for children or disabled or older relatives. This work currently falls overwhelmingly on women and results in an exaggerated gender pay and superannuation gap.

Even if all of the above proposals were adopted, they would be unlikely to completely level the playing field for women in the foreseeable future. But, taken together, we believe that these interventions would go a considerable way towards closing the stark retirement income gap faced by women in Australia today.

Warwick Smith is Research Economist at Per Capita. He works in Per Capita’s Centre for Applied Policy for Positive Ageing (CAPPA) and in the Progressive Economics program. His recent projects include the adequacy of the Age Pension, employment policy and the future of Australia’s ageing workforce.

David Hetherington is Senior Fellow at Per Capita, where he was the founding Executive Director. He has written over 100 major reports, book chapters and opinion pieces on a wide range of economic and social policy issues, including fiscal policy, market design, social innovation, employment, education and training, disability, housing, and climate change.

The authors wish to thank the Australian Services Union for its collaboration on this research and its commitment to the idea of equal outcomes for women in retirement.

We also wish to express our gratitude to the thousands of workers who participated in the survey component of this research.

This is an edited excerpt of the Per Capita report, Not so super, for women: Superannuation and women’s retirement outcomes. The full report, including a complete list of the recommendations, can be accessed at: <https://percapita.org.au/research/not-so-super/>.

[1] Senate Economics References Committee, Parliament of Australia, ‘A husband is not a retirement plan’: Achieving economic security for women in retirement (29 April 2016).

[2] Workplace Gender Equality Agency, Gender pay gap statistics (March 2016).

[3] P Apps, ‘Gender equity in the tax-transfer system for fiscal sustainability’ (Working Paper 5/2016, Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, Australian National University, August 2016).

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/PrecedentAULA/2018/4.html