|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Precedent (Australian Lawyers Alliance) |

RESIDENTIAL CARE FOR OLDER PEOPLE – ISSUES FOR THE LEGAL PROFESSION

By Dr Tuly Rosenfeld

Older people make up an increasing proportion of the Australian population, a development that is not unique to Australia but is the common experience of developed countries across the world. This demographic shift has had profound implications for Australian society, with health services and legal structures struggling to keep up with the often complex and diverse needs of the ageing population.

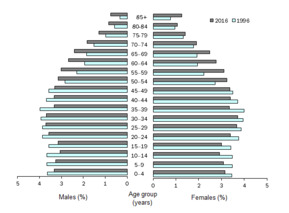

Over the 20 years between 1996 and 2016, the proportion of the population aged 65 years and over in Australia increased from 12.0 per cent to 15.3 per cent.[1] This group is projected to increase more rapidly over the next decade, as further cohorts of baby boomers (those born between the years 1946 and 1964) turn 65.

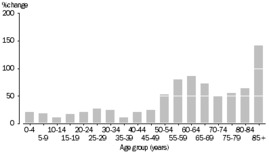

The consequences of this demographic shift are felt acutely by individuals over 85 years of age, the ‘old-old’. Over the past two decades, the number of persons aged 85 years and over has increased by 141.2 per cent, compared with a total population growth of 32.4 per cent over the same period.

Table 1 Australian Bureau of Statistics 3101.0

Australian Demographic Statistics, June 2016

Population Change, Age Group – 1996 to 2016

Table 2

Table 2 Australian Bureau of Statistics 3101.0

Australian Demographic Statistics, June 2016

Population Change, Age Group – 1996 to 2016

THE DISEASES OF AGEING

As the population ages, the prevalence of disease in older individuals rises dramatically. Cardiovascular illness, bone and joint diseases, brain and nervous system diseases all increase. The presence and increasing prevalence of neurodegenerative (nervous system) diseases comprise the most significant issue in terms of older individuals’ ability to function in day-to-day life.

Functions that we take for granted in our daily lives are, for many older people – especially in the ‘old’ and ‘old-old’ categories – eroded: independent mobility; activities of daily living (personal care – bathroom, hygiene, dressing); functional activities of daily living (using a phone, housework, shopping, driving). A key, but too often unrecognised, factor leading to this loss of function is the presence of underlying, progressive, brain disease and dementia.

The prevalence of dementing illness in community-living people over 85 years is at least one in three. For those in hospitals it is far greater. In residential care, between 50 to 90 per cent of residents suffer dementia, although studies vary widely.[2] Unfortunately, the rate at which dementia, and other neurodegenerative diseases is recognised or diagnosed is relatively low.[3] These figures are therefore likely to underestimate the actual prevalence of brain disease.

Our brains are involved not only in controlling a range of body functions (heart rate, blood pressure, hormone balance) but also mobility, movement and balance. Thinking and memory obviously comprise key elements of brain function. Indeed, memory function has been the focus of medical, academic and therapeutic pursuits as awareness of brain diseases, such as Alzheimer’s Disease, has increased.

Less well-recognised, however, is that higher level (also termed ‘executive’) functions, key to one’s ability to negotiate, navigate and resolve issues regarding one’s place in the world, are also eroded with the progression of brain disease. These functions include judgement, insight, initiative, social control, reflection, the ability to weigh conflicting ideas and memories, problem-solving, language, impulse control, sexual behaviour, spontaneity and mood.

The subtle and individual ways in which these functions are eroded lead to many of the issues that confront families, carers, doctors and other health professionals and lawyers. Older people who require assistance, support and care, in the community or in residential care, are invariably likely also to have a variable degree of problems with informed decision-making; problems with providing informed consent; resistance or reluctance to accept support or interventions required for their care and safety; susceptibility and sensitivity to the adverse effects of medical interventions, including medications; as well as vulnerability to influence by a range of factors.

These issues are particularly relevant to the care of elderly people and the role of carers and decision-makers in residential care settings. Legal practitioners are frequently involved in helping older people and their families or carers with these issues.

ISSUES SPECIFIC TO THE ORGANISATION AND PROVISION OF CARE IN NURSING HOMES

The system whereby care and accommodation are provided in residential aged care facilities or nursing homes (RACFs) has developed from the need to provide alternatives to care and accommodation at home and in the community. Over recent years the nature and the intensity of care required in RACFs has evolved and become more intense given the changing demographics of ageing and increasing numbers of older, more complex, sicker people living in residential care. These individuals invariably bring with them complex family relationships, together with a range of complex financial and legal issues.

The quality and nature of hotel-type services in RACFs (cleaning, food, linen) have evolved and probably, in the author’s view, work considerably better than the manner in which the organisation and provision of healthcare is able to meet the needs of these older, frailer, cognitively impaired residents.

A range of issues have been recognised and variably addressed or resolved. Ongoing issues include the determination of suitable and effective staff (resident/nursing) ratios; the training and expertise of care staff; administrative/record-keeping systems; health information-sharing across different settings (RACFs, general practice, hospital); medication management; provision and continuity of medical services; after-hours medical cover; and family communication and engagement.

Case study: 1

78-year-old woman, Mrs B, was cared for at home by her husband. A previous stroke had left her immobile, although she was able to transfer to a wheelchair. She was dependent on her husband for all activities of daily living: he fed her and provided her with personal care with the help of home nurses three times per week. She suffered from behaviours that required regular medication.

Her husband had to go overseas for two weeks and organised respite in a RACF. Having previously used respite for his wife at the RACF he knew that the RACF needed information about her care. He obsessively provided them with a detailed written outline of all her needs including Mrs B’s medications. One of the medications was a mood stabiliser that helped to control her agitation and had been carefully adjusted over some years. All her treatment, medications and care needs were thoroughly documented by her husband.

Two days after she had been admitted, one of the nurses found that one of the medications (the mood stabiliser) had been omitted from the medication sheet that had been faxed from her GP doctor’s surgery at the time of her admission to the RACF. The nursing home contacted the surgery but a new prescription was only received by fax and the medication recharted three days after Mrs B was admitted for respite. A day after her admission, Mrs B was suffering from worsening agitation and an after-hours GP was called to settle her with a new prescribed sedative (not the specific mood stabiliser she had been taking).

By the time that the omitted medication had been prescribed and administered, Mrs B was drowsy, febrile, and had acquired a chest infection. She needed to be sent to hospital and, four days later, one week after her respite admission, she died with aspiration pneumonia. Action was taken against the RACF.

This case illustrates a common feature of the disconnect between community and residential care such as failures in admission preplanning; issues relating to GP communication and attendance at the RACF; and after-hours medical care in RACFs. The lack of effective case management in residential care and in the community underpins the most problematic factor in how services are organised and provided and is a common factor when things go wrong.

CHOOSING AND ENTERING A RESIDENTIAL AGED CARE FACILITY

One might expect that as one gets older and more frail the task of seeking and selecting the mode and setting of care, whether at home or in a residential care place, will be reasonably straightforward. The reality is starkly different.

Although Aged Care Assessment Teams (ACATs) have been operating in Australia since the early 1990s, their nature and operation around Australia varies greatly. Significant changes have occurred over time, particularly over the last 12 months. Assessment by an ACAT is necessary to qualify for an Australian government subsidy for aged care services at home or for entry to a RACF.

The decision to enter a RACF is probably one of, if not the biggest, life decisions that an older person, or their family, has to make. The author’s experience is that the systems for providing support, advice and guidance for older people or their families to make informed health, lifestyle and financial decisions are unsophisticated, inconsistent and variable. All too often, these major decisions are made in haste and as a result of escalating care needs during illness or crisis.

Financial advice relating to a range of issues particular to that individual, and consideration of all the options, including the option to remain at home, is often unavailable. Formal legal advice concerning consent, contracts, powers of attorney, estate planning and wills is too often ad hoc, ill-considered or not sought at all despite the considerable complexity of the financial and legal implications of a move to residential care.

PREMATURE AND PREVENTABLE DEATHS IN NURSING HOMES

The medical and health care of older people is challenging and requires specialist expertise and training (both of nurses and doctors), continuity of care and effective handover of healthcare information between care staff (doctors, allied health, nurses), information systems, and a range of quality and safety measures. Older people, particularly those likely to require care in a RACF, suffer from a range of complex medical and health needs.

When an older person is admitted to hospital for routine or emergency treatment, often as a transfer from a RACF, they receive a comprehensive range of nursing, allied health and medical care, usually several times a day. The medical team usually comprises multiple doctors and an admitting specialist, who review the patient on a regular or daily basis. The ‘stepdown’ process of admission or return to the lower intensity of care in a RACF (medical and nursing) is very significant, considering that the patient’s care and medical management needs do not usually reduce or change from one day to the next. Medical care in a RACF comprises much less frequent review, often monthly or even less frequently, and only more often or acutely at the instigation of nursing staff or family, without access to the range of services, consultations across specialities and specialist expertise available in the hospital setting. Most patients’ needs, especially for older people with complex needs, do not necessarily make the same ‘stepdown’ in need. While patients in RACFs are less acutely ill than those requiring hospital care, the nature and extent of their underlying illnesses continue and the likelihood of acute deterioration is ever present.

An ongoing issue in the care of older people in RACFs, and one factor in the recurrent presentations of older people to hospital, is the challenge of providing residents of RACFs with regular expert medical care. General practitioners (GPs) are too often reluctant to follow their longstanding patients after their entry to a RACF. This leads to the need to hand over often complex medical care to an entirely new doctor. The challenges to the continuity of care comprises a significant obstacle to optimal management.

This common lack of continuity in care leads to poorer outcomes and errors, as well as issues arising from the loss of the contact and personal relationship with a long-known and trusted doctor. Medical specialists do not generally attend RACFs, meaning that the resident requires transport to specialists’ rooms or review in hospital. That older people often require specialist review for multiple illnesses leads to the reduced likelihood that review and care will be regularly provided. Medical after-hours cover in RACFs is variable, often piecemeal, and disconnected to the resident’s long-term care by their allocated treating GP.

The care of older people with complex needs in RACFs is complex and challenging. Errors are more likely in this setting. Older people’s physical needs are also considerable and complex.

Mobility and balance, and therefore falls, comprise a significant background cause of adverse events and death.[4] Other problems include the adverse effects of medications (and their interactions when multiple medications are prescribed), problems arising from the use of sedatives and mind-altering medications to control dementia-related behaviours, medication errors and inadequate care or neglect.

The need to identify a decision maker, the legal guardian or responsible person involved in a resident’s care is often an issue that is overlooked or neglected until problems in care planning and treatment arise, often in crisis. In some settings this process is undertaken better than in others. An ongoing challenge for residential care providers and clinical carers (doctors and nurses) is the identification and diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia and, when this does occur, instituting appropriate measures that deal with the significant changes in the decision making and legal processes.

Legal practitioners will increasingly be called upon to advocate for patients and families of older people in residential care. Disputes about levels of care and the care of older people who require or are perceived to require higher levels of care than can be provided in a particular care setting are likely to become increasingly common.

Case study: 2

An 83-year-old woman, Mrs J, was living in an independent unit in a RACF. Suffering from worsening dementia, she had been seen on an ongoing basis by a geriatrician, whom she attended with her daughter. Owing to worsening behaviours and agitation, Mrs J was sent to hospital where an infection was diagnosed.

At the same time, Mrs J was prescribed regular sedative/anti-psychotic medication and discharged. Her daughter was not informed nor gave consent to this new treatment and remained unaware of its potential adverse effects.

Mrs J was no longer safe living in her independent unit and was re-referred to hospital when she became acutely ill. She was subsequently discharged to the hostel section of the RACF. A new GP who attended residents in the home was appointed to oversee her care.

Mrs J was seen by a geriatrician in his rooms. In response to the daughter’s concern about Mrs J’s sleeping difficulty, he recommended a change in the timing of administration of the anti-psychotic medication, but at the same dose. The GP misread the instruction and increased the dose.

After two weeks, the patient’s reducing mobility and drowsiness led to her being sent to hospital where a urinary tract infection was diagnosed as the problem, and she was discharged back to the RACF.

Within another week, her condition had deteriorated further; she was immobile and ultimately unconscious. Although her level of consciousness improved, she remained immobile and fully dependent, requiring nursing home care.

This case illustrates issues relating to informed consent; identification of changing status; identification and notification of medication errors; the disconnect between the previous GP, new GP, specialist and hospital; and blame-shifting.

ADVANCE CARE PLANNING AND ADVANCE CARE DIRECTIVES

The likelihood that problems associated with the progression of illness will worsen has led to the recognition that decision-making and advance care-planning is a much better option than determining and providing care in crisis.

Legal capacity, decision-making and informed consent

With increasing numbers of older people suffering from brain disease and dementia, the need to establish the presence or otherwise of capacity for decision-making has emerged as a major concern in many areas of their lives.

Legislative frameworks have been established: in NSW, the Guardianship Tribunal is increasingly involved in financial and health-related decision-making, and legal practitioners are increasingly called upon to assist older people and their families/carers with legal matters, wills and estates, contracts, appointing powers of attorney and enduring guardians.

Legal capacity is a term that is determined not only by an individual’s cognitive abilities but also, to a very significant extent, the specific nature of the legal matters in question. RACFs are much more aware of these issues than in the past. However, the need for varying kinds of assistance and intervention arising as a consequence of the increasing number of older people with cognitive problems will certainly increase. Legal practitioners will increasingly be involved in assisting their clients and families with these matters.[5]

SUMMARY

The care of older people is complex and requires expertise, teamwork, multi-disciplinary involvement, communication, careful handover of care issues and plans, effective engagement with families and carers, and responsiveness to the older person’s often quickly changing needs and health status.

The health system generally strives but struggles to address these complex multi-system needs. Older people who enter residential care settings often do so as a result of their increasing need and the complexity of their care, their medical problems, and their family situation. Mobility problems, falls, cognitive impairment and dementia are prominent issues that characterise the needs of older people in residential care, and frequently lead to adverse events.

Legal issues, powers of attorney, care decision-making (guardianship), consent, estate planning, general decision-making, longer-term care planning and care directives, and the determination of capacity to undertake some or all of these issues, are currently addressed in an untimely and sub-optimal manner.

Dr Tuly Rosenfeld MBBS FAAG FRACP is a geriatrician who has worked in hospitals, community and residential aged care settings for 35 years. Now in private practice, he was formerly director of a large public hospital geriatric medicine department and has been involved in developing aged care services in the public and private hospital sectors, NSW health department, and community welfare organisations. Dr Rosenfeld has extensive experience in medico-legal matters, capacity in wills and estates, coroners cases and other matters before the courts. Dr Rosenfeld is Adjunct Professor at UTS and Conjoint Assoc. Professor at UNSW and Notre Dame University. EMAIL admin@rosenfeldconsulting.com.au.

[1] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 3101.0 - Australian Demographic Statistics, June 2016.

[2] F Hoffmann, H Kaduszkiewizc, G Glaeske, H van den Bussche and D Koller, ‘Prevalence of dementia in nursing home and community-dwelling older adults in Germany’,

Aging Clin Exp Res., Vol. 26, No. 5, March 2014, 555-9; R Stewart et al, ‘Current prevalence of dementia, depression and behavioural problems in the older adult care home sector: South East London care home survey’, Age and Ageing, Vol. 43, No. 4, July 2014, 562-7.

[3] H Brodaty, G C Howarth, A Mant and S E Kurrle, ‘General practice and dementia. A national survey of Australian GPs’, The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol. 160, No. 1, January 1994, 10-14.

[4] J Ibrahim et al, ‘Premature deaths of nursing home residents: An epidemiological analysis’, The Medical Journal of Australia, Vol. 206, No. 10, June 2017.

[5] K Purser and T Rosenfeld, ‘Assessing testamentary and decision-making capacity: Approaches and models’, Journal of Law and Medicine, Vol. 23, No. 1, 121; K Purser and T Rosenfeld, ‘Evaluation of legal capacity by doctors and lawyers: The need for collaborative assessment’, Medical Journal Australia, Vol. 201, October 2014, 483-5.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/PrecedentAULA/2018/59.html