|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Precedent (Australian Lawyers Alliance) |

CHARACTER APPLICATIONS BEFORE THE ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL

PRACTICAL GUIDANCE FOR THE CONSCIENTIOUS PRACTITIONER

By Amanda Do and Dr Jason Donnelly

Non-citizens who seek residence of any kind in Australia are subject to strict statutory regulation under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (the Act). One aspect of that statutory regulation is that non-citizens who have engaged in criminal or other adverse conduct can be the subject of visa cancellation and refusal decisions under pt 9 of the Act.[1] This article offers practical guidance for the conscientious practitioner acting in character-related matters before the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT).

AN INCREASINGLY HOSTILE REGIME

Australia's statutory regime concerning character matters has become increasingly hostile to non-citizens. The statutory and practical consequence has been the expansion of migration decisions made by delegates of the Minister for Home Affairs, the AAT, and the Minister, acting personally.

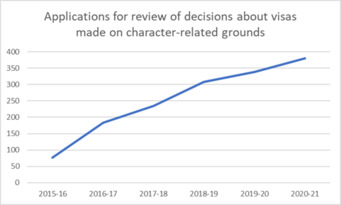

Figure 1 shows the increasing number of review applications lodged with the AAT by non-citizens in relation to appealing adverse character decisions made at first instance by the Minister. This has led to an increased demand for legal services in this area of the law.[2]

Figure 1: Increase in applications for review: a sign of waning tolerance for non-citizens’ presence in Australia.

Acting for non-citizens before the AAT in character-related matters can be a trap for the unwary – this area of the law has become increasingly complex. Given this context, this article seeks to do two things:

• firstly, to logically explain the procedure in acting in character-related matters before the AAT under pt 9 of the Act; and

• secondly, and inextricably linked to the first purpose, to provide practical guidance and direction to legal practitioners acting in such matters.

STATUTORY REGIME

The power for a decision-maker to refuse or cancel a non-citizen’s visa on character grounds is provided in ss500A–501CA of the Act.[3]

The character test

The character test is defined in ss501(6)–(7) of the Act. A non-citizen can be taken to fail the character test if:

• they have a substantial criminal record;[4]

• they have been convicted of an offence related to immigration detention;[5]

• they have an association with criminal organisations;[6]

• they have committed deemed criminal offences;[7]

• having regard to their past and present criminal and general conduct,[8] they would risk engaging in criminal conduct or engage in other undesirable conduct in Australia;[9]

• they have been charged with certain deemed offences;[10]

• they have been assessed as a risk to security by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation;[11] or

• it is reasonable to infer that they would present a risk to the Australian community on account of having been issued with an Interpol notice.[12]

A more recent addition to the character test is the mandatory cancellation regime under s501(3A). Here a non-citizen is objectively taken to fail the character test if they have been sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 12 months or more and are otherwise serving a sentence of imprisonment, on a full-time basis in a custodial institution, for an offence against the law of the Commonwealth, a state or a territory.

The initial steps of the review process

When a delegate within the Department of Home Affairs makes an adverse character decision concerning a non-citizen under pt 9 of the Act, the non-citizen can have the decision reviewed with the AAT.[13] Critically, the non-citizen has only 9 days to lodge an appeal with the AAT against the delegate’s decision.[14] Accordingly, practitioners should make sure that they are aware of this strict statutory time limit. There is no possibility of an extension of time to appeal.

Generally, the AAT will hold a telephone directions hearing within 7 seven business days after the appeal was lodged. There are several important factors that practitioners should keep in mind at this stage.

First, when providing a client with a costs disclosure[15] and costs agreement,[16] practitioners should keep in mind that the full scope of running a character matter before the AAT requires an extensive amount of work. For example, the true extent of work involved in the appeal will often not be readily appreciated until the summons material (frequently requested by the respondent) is produced to the AAT. Generally, the amount of summons material required to be produced to this tribunal ranges from a few hundred to a few thousand pages. As such, a considerable amount of material produced in answer to an AAT summons will not have been before the delegate. Accordingly, practitioners should consider the level of work involved when entering into legal relations with the relevant client.

A second trap for the unwary is the statutory effect of s500(6L)(c) of the Act. Under this section, the AAT has 84 days from the date on which the non-citizen was notified of the original decision to make a decision on review. If a decision is not made within 84 days, the original decision of the delegate is taken to have been affirmed.[17] The statutory consequence of this regime is that this tribunal has a very limited period to decide on review. In practical terms, this means that when the AAT conducts the original telephone directions, a very strict timetable is put in place for the steady progression of the matter. There is limited scope for this tribunal to act with broad discretion in setting dates: it must mandatorily decide within 84 days of the relevant date or otherwise risk the appeal process becoming a futile exercise. Again, practitioners should keep this in mind when accepting instructions concerning a character matter before the AAT. Before the telephone directions hearing, given the strict time limits in this area, when acting for non-citizens in the AAT practitioners should consider filing summons documents with this tribunal. This will help speed up the process.

The two most helpful entities to request to issue a summons are International Health and Medical Services and the equivalent Department of Justice in the relevant Australian jurisdiction. The former entity will provide relevant health documents associated with the non-citizen in immigration detention, and the latter will often produce comprehensive material related to most aspects of the non-citizen’s time in custody. These documents can often prove helpful in building a case for the non-citizen before the AAT.

Further, in general terms, practitioners can expect the following orders and notifications to be made at the telephone directions hearing:

1. The applicant and respondent will be required to file and serve a copy of their respective statement of facts, issues and contentions by a certain date.

2. The parties will be required to file with the AAT by a certain date any requests for a summons.

3. Immediate access to documents produced under summonses issued will be required for both parties.

4. The applicant will be required to file and serve any reply evidence by a certain date.

5. The matter will be given a hearing date for X number of days on certain dates.

6. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, leave will be granted to the parties to appear by video link at the hearing and, if the non-citizen is in immigration detention at the time of the hearing, the respondent will be required to undertake to make these arrangements for the non-citizen.

At the telephone directions hearing, practitioners will generally also be required to confirm with the presiding member of the AAT which is the 84th day in terms of s500(6J) of the Act. This date will be added as a notation when the AAT publishes its directions. Practitioners should also inform this tribunal whether an interpreter will be required for the final hearing. Fortunately, where this is necessary the AAT will organise the interpreter for the full final hearing without cost to the parties.

PREPARING FOR TRIAL

Part of a continuum

Although the AAT will undertake a fresh merits review of the non-citizen’s application, practitioners should not lose sight of the fact that it forms part of an administrative decision-making continuum.[18] As Logan J made plain in Kelekci v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs:[19]

‘While the Tribunal stands in place of the decision-maker whose decision is under review, it does not do so in a vacuum. Rather, as Davies J’s observation pithily reveals, it does so as part of a continuum. That it does so has many ramifications, but one which is material for the present purposes is that the issues which the Tribunal must confront in terms of discharging its statutory function can be revealed by, indeed dictated by, the continuum of administrative decision-making’.[20]

In practical terms, this means that the practitioner should forensically seek to respond directly to the adverse findings made by the original decision-maker. Doing so generally requires getting further instructions from the non-citizen client, seeking out further information from potential witnesses, and undertaking further research.

Guidance for practitioners

When preparing witness statements to be relied upon in the AAT, there is no need to adduce evidence that is already reflected in the G Docs: these include all the documents in the Minister’s possession or under the Minister’s control that were relevant to the making of the original decision.[21] Often, in character-related matters before this tribunal, various written statements and character references were submitted by the non-citizen to the Department of Home Affairs at first instance. Accordingly, to the extent that it is necessary to produce witness statements before the AAT, the applicant (via their legal representative) should generally provide an update of evidence already given by relevant witnesses of the non-citizen, and accommodate new witnesses who did not give evidence for the non-citizen at first instance.

Also, when drafting the applicant’s statement of facts, issues and contentions, it is critical that the practitioner closely follow the relevant mandatory considerations reflected in Direction no. 90 (Direction 90).[22] At the time of writing, Direction 90 is the current ministerial policy made under s499 of the Act, which the AAT is bound to apply.

Direction 90 provides what is known as ‘primary’ and ‘other’ considerations. It mandates that, generally, primary considerations should be given greater weight than the ‘other’ considerations. However, practitioners should note the very useful authority of Colvin J in Suleiman v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection:[23]

‘Direction [90] does not require that the other considerations be treated as secondary in all cases. Nor does it provide that primary considerations are “normally” given greater weight. Rather, Direction [90] concerns the appropriate weight to be given to both “primary” and “other considerations”. In effect, it requires an inquiry as to whether one or more of the other considerations should be treated as being a primary consideration or the consideration to be afforded greatest weight in the particular circumstances of the case because it is outside the circumstances that generally apply’.[24]

Practitioners should also note the important effect of para 9(1) of Direction 90. That aspect of the ministerial direction makes plain that the list of ‘other’ considerations is not exhaustive. As such, practitioners should duly consider whether a consideration not reflected in Direction 90 is relevant and supportive of an applicant’s case before the AAT. If it is, it should be included.[25]

Finally, witnesses proposed to be called at the trial should be conferenced and properly prepared. Witnesses should generally be made aware of the non-citizen’s criminal record, advised about the process of cross-examination, and given sufficient notice of the hearing date for the trial.

THE CONTESTED TRIAL

Generally, the practitioner representing the applicant non-citizen does not have the burden of cross-examination – largely since the respondent does not generally call witnesses. Accordingly, the practitioner should take concise and forensic notes of evidence adduced orally during the examination-in-chief and cross-examination process. Those notes will form the foundation for the oral closing addresses given by the parties at the end of the trial.

A further trap for the unwary is the statutory effect of ss500(6H) and 500(6J) of the Act.[26] These provisions make it plain that the AAT must not consider any information presented orally, or any document submitted, in support of a non-citizen’s case unless a copy of the document or record of the evidence presented orally is set out in a document given to the respondent Minister at least two business days before this tribunal holds a hearing concerning the decision under review. As such, when asking questions in examination-in-chief in support of the applicant’s case, the practitioner must keep this statutory limitation in mind.

Given the statutory discrimination and limitations placed upon an applicant’s case before the AAT, the judgment of Katzmann J in SZRTN v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection[27] provides a useful summary of what a practitioner can seek to achieve in examination-in-chief:

‘If the oral evidence does not change the nature of the case and merely puts flesh on the bones, so to speak, it may be doubted whether it can be excluded. There seems to me to be no reason why a witness could not be called to speak to his or her statement, to correct any inaccuracies, to explain any ambiguities, or to elaborate upon certain matters as long as in so doing the witness does not stray outside the subject matter of the material covered in the statement.’[28]

When the respondent’s legal representative is cross-examining an applicant’s witnesses, the practitioner should be on guard to take objection to questions that seek an answer that may self-incriminate the relevant witness. No adverse inference can be drawn from the witness exercising their privilege against self-incrimination.[29] Often the respondent’s legal representative will pose questions related to a document alleging criminality or wrongdoing where the witness has not been charged. In advance of the trial, the practitioner should explain the rule against self-incrimination to the applicant and their witnesses.

The practitioner should also give some thought to the order in which witnesses will give evidence in the applicant’s case. Generally, the AAT will wish to hear from the applicant first. What follows in terms of the order in which witnesses are called is at the practitioner’s discretion. One possibility is to start and finish with a strong witness. This may well be a balanced approach to adducing evidence in the applicant’s case.

FINAL REFLECTIONS

Working in character-related reviews before the AAT is a great privilege for legal practitioners. The human consequences of appeals such as these are far-reaching.[30] A non-citizen removed from Australia due to failing the character test is generally prohibited from ever returning to the country.[31] There is a lot on the line.

The work a practitioner undertakes in this area of the law can change the course of a non-citizen’s life, and the lives of their family and friends. Adverse decisions before the AAT can also possibly lead to further work for legal practitioners in the context of judicial review applications before the Federal Court of Australia. Of course, legal practitioners would need to be satisfied that there are reasonable prospects in demonstrating that the adverse tribunal decision is affected by jurisdictional error.

In summary, character-related reviews before the AAT have increasingly become an important area of work, not just for the tribunal itself but also for the legal professional more broadly.[32]

Amanda Do is a solicitor with Maurice Blackburn Lawyers. EMAIL ADo@mauriceblackburn.com.au.

Dr Jason Donnelly is a barrister, and the course convenor of the Graduate Diploma in Australian Migration Law and a senior lecturer at Western Sydney University. Dr Donnelly is also a co-author and editor of the Federal Administrative Law publication (Thomson Reuters, 2021). EMAIL donnelly@lathamchambers.com.au. WEBSITE https://www.jdbarrister.com.au/.

[1] Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act), ss496–505.

[2] Administrative Appeals Tribunal, 2015–16 Annual Report, 2016–17 Annual Report, 2017–18 Annual Report, 2018–19 Annual Report, 2019–20 Annual Report, 2020–21 Annual Report <https://www.aat.gov.au/about-the-aat/corporate-information/annual-reports>.

[3] A Moss, ‘Risk of Harm, Relevant Considerations and Section 501: Wrangling the Minister’s Discretion’, Australian Law Journal, Vol. 91, no. 4, 2017, 268–75.

[4] A person has a substantial criminal record if, inter alia, that person has been sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 12 months or more. See further Migration Act, s501(7).

[5] Ibid, s501(6)(aa)–(ab).

[6] Ibid, s501(6)(b). See further J Donnelly, ‘Failure to Give Proper, Genuine and Realistic Consideration to the Merits of a Case: A Critique of Carrascalao’, University of New South Wales Journal Forum, Vol. 2, 2018, 1–10.

[7] Migration Act, ss501(6)(ba), 501(6)(e) and 501(6)(f).

[8] Ibid, s501(6)(c).

[9] Ibid, s501(6)(d).

[10] Ibid, s501(6)(e)–(f).

[11] Ibid, s501(6)(g).

[12] Ibid, s501(6)(h).

[15] See for example the Legal Profession Uniform Law (NSW), pt 4.3.

[16] Ibid.

[18] See Jebb v Repatriation Commission [1988] FC8 105; Kelekci v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2020] FCA 1000 (Kelekci), [24].

[19] Kelekci, above note 18.

[20] Ibid, [24].

[24] Ibid, [23].

[25] See for example Joshua Steven Clegg and Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs (Migration) [2020] AATA 3383, [98].

[26] The purpose of the scheme in s500 is to prevent an applicant from changing the nature of the case, catching the Minister by surprise and forcing the AAT into adjourning the proceedings: see Goldie v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2001] FCA 1318, [25]; Uelese v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2013] FCAFC 86, [31].

[28] Ibid, [70].

[29] See Dolan v the Australian and Overseas Telecommunications Corporations [1993] FCA 206; Katherine Anne Victoria Pearson and Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs (Migration) [2020] AATA 3527, [42].

[30] See Hands v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] FCAFC 225, [3].

[31] C Bostock, ‘The Administrative Appeals Tribunal and Character Assessments for Non-Citizens’, PhD thesis, University of New South Wales, 2015, 49.

[32] M Grewcock, ‘Punishment, deportation and parole: The detention and removal of former prisoners under section 501 Migration Act 1958’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011, 56–73.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/PrecedentAULA/2022/18.html