Sydney Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Sydney Law Review |

|

Parliaments, Proportionality and Facts

Gabrielle Appleby[1]* and Anne Carter[1]†

Abstract

One of the key doctrinal developments of the High Court of Australia in relation to its constitutional limitations jurisprudence is the structured test of proportionality. In recent cases involving the implied freedom of political communication, the Court has indicated that its constitutional adjudicative function will be informed by the extent to which a parliament has, or has not, considered issues of proportionality. In this article, we examine these developments through the parliamentary institutional lens: we ask what the implications are for Australian parliaments if the Court adopts an approach to proportionality reasoning that is sensitive to parliamentary fact-finding and deliberations. We explore how the Court’s restraint in applying the proportionality test might have two, interrelated, consequences. The first is the type of factual material that the political branches should be seeking when they make determinations about whether a law is ‘reasonably necessary’ to achieve a stated objective, and whether the regime has struck the most appropriate ‘balance’ between competing claims on the public good; and how parliamentarians should deliberate about that material. The second is whether evidence could be led in court to satisfy the judiciary that a parliament has considered the relevant facts, and deliberated appropriately about them, and, if so, the process that should be adopted for leading such evidence.

Please cite this article as:

Gabrielle Appleby and Anne Carter, ‘Parliaments, Proportionality and Facts’ [2021] SydLawRw 11; (2021) 43(3) Sydney Law Review 259.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence (CC BY-ND 4.0).

As an open access journal, unmodified content is free to use with proper attribution.

Please email sydneylawreview@sydney.edu.au for permission and/or queries.

© 2021 Sydney Law Review and authors. ISSN: 1444–9528

There is an emerging uncertainty in the High Court of Australia’s jurisprudence on the implied freedom of political communication about the extent to which a parliament needs to produce evidence to support its decisions about the proportionality of particular legislative measures.[1] A number of recent cases illustrate the potential importance of evidentiary questions when applying proportionality analysis to determine whether laws that burden the implied freedom are justified.[2] Moreover, they demonstrate that there remain significant unanswered questions about the relationship between courts and parliaments with respect to these questions. Specifically, there is a lack of clarity about the degree to which the High Court, in performing its duty to determine constitutional facts, will be informed in its analysis by the factual material that was before a parliament, the extent of factual inquiries that parliament itself undertook during its deliberations, and extent and nature of those deliberations.

The High Court has not, so far, developed a consistent, or at least explicit, framework for when or how to evaluate the fact-finding and deliberations undertaken by a parliament. In this article, we examine this question through an iterative cross-institutional lens. That is, we investigate the potential implications for Australian parliaments if the High Court adopts an approach to proportionality reasoning informed by the fact-finding and deliberative processes of parliament, and how development of parliamentary practice might then affect the development of the Court’s approach.

This article draws together two areas of scholarly inquiry. First, it examines the nature of the proportionality inquiry undertaken by courts. Specifically, it looks at the extent to which this inquiry requires courts to make findings of fact, and whether parliamentary fact-finding and deliberation might inform that inquiry.

Our analysis of the High Court’s current position reveals that the issue of how courts are to make the necessary factual determinations, and how they should treat fact-finding and deliberations of a parliament, is unresolved. This question relates directly to the issue of whether there is, or ought to be, a level of judicial restraint or deference to the decision-making processes of the political branches. The Court itself continues to reject any role for ‘deference’ in the Australian constitutional context,[3] and we explore the extent to which this is maintainable in the light of more recent indications that a parliament’s fact-finding processes and deliberations may inform the Court’s decision-making in this area.

Second, the article draws from theories about the interrelationship between parliaments and the courts, particularly with respect to their institutional roles under, and obligations to, the Australian Constitution. We suggest that, even under a position accepting the supremacy of judicial review as we have in Australia, there is nonetheless a responsibility on parliaments to engage with the Constitution. This includes an obligation to consider whether proposed legislation breaches constitutional norms and to engage with the various fact-finding and deliberative elements of the proportionality inquiry.

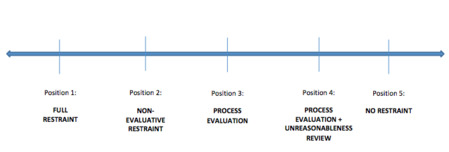

We then explore what this means for the relationship between the courts and parliaments by developing a ‘spectrum of inter-institutional relations’. This spectrum is firmly situated in the Australian constitutional context and the High Court’s understanding of its institutional role, including its ultimate responsibility for determining constitutional meaning and thus determining the facts on which that must be determined, and its scepticism towards the idea of deference in the Australian constitutional framework. The spectrum, which is both relational and iterative, consists of five different positions at which a court may engage with parliamentary fact-finding and deliberations. At one end of the spectrum there is what we term ‘full restraint’, where a court accepts or gives conclusive weight to the decisions of a parliament — that is, their fact-finding and the deliberations about those facts. At the opposite end of the spectrum is what we term ‘no restraint’, where a court places no weight on the views of the relevant parliament and proceeds instead to form its own view on all of the relevant factual matters (including conducting its own fact-finding), and conducts no review of the quality of parliamentary fact-finding or deliberation. Both of these extreme positions are problematic in terms of the High Court’s role in the Australian constitutional system. The first gives conclusive force to the parliament, which in effect dilutes constitutional judicial review of any strength and is inconsistent with the Court’s constitutional duties. The second, conversely, involves the Court substituting its own views for those of the parliament, which also misunderstands its role in a constitutional system in which political constitutionalism remains an informing foundational principle.

Between these two extremes are the positions we label ‘non-evaluative restraint’, and ‘process evaluation’, and ‘process evaluation + unreasonableness review’, where a court gives some consideration or weight to the views of the parliament and the fact-finding and deliberative processes it has followed. Under ‘non-evaluative restraint’, the mere fact that the legislature has engaged with the relevant question is sufficient, whereas under ‘process evaluation’, a court engages with the substance of the parliament’s fact-finding and deliberative processes. ‘Process evaluation + unreasonableness review’ differs from this position only insofar as it requires judicial review of the substantive outcome of the political decision-making process to check for ‘unreasonableness’. Following from ‘process evaluation + unreasonableness review’ there are a number of options a court may make take depending on the nature of the process undertaken by the relevant parliament and a court’s evaluation of this process and the substantive outcome.

In addition to contributing to an understanding of the possible approaches, we also develop a normative claim about the point on the spectrum that best reflects the appropriate relationship between the High Court and parliaments in the Australian context. Our normative position is informed by our understanding of the High Court’s role and the inter-institutional obligations of the political branches, as well as the normative desirability of greater and more responsible legislative engagement with these questions, and finally by the High Court’s current approach to these questions.

The article is organised into four main parts. Part II is focused on the judicial approach, and it examines the nature of the proportionality inquiry that has been adopted by a majority of the Australian High Court. It confirms that the High Court’s legal conclusion about proportionality is underpinned by various questions of fact. But the question of how these facts should be determined, and the relevance of parliamentary fact-finding and deliberation to judicial determination of these facts, has not been definitely settled. In Part III, the focus shifts to parliaments, and we review the relevant literature on departmentalism, how this intersects with different theories about the supremacy of judicial review, and how this informs the appropriate role of parliaments in terms of assessing the proportionality of legislation. In Part IV we turn to the substantive contribution of the article, as we set out a spectrum of inter-institutional relations. We delineate the role of the courts at each position on the spectrum, and also discuss the potential consequences that flow from the various positions. In Part V, we develop a normative claim about where the High Court ought to position itself on this spectrum. Ultimately, we contend that this spectrum can provide guidance on the weight that the Court should give to the parliamentary process. In this way, it will help to clarify the Court’s fact-finding role when applying tests of proportionality, and will both clarify and incentivise parliamentary engagement with constitutional questions of proportionality.

In this Part we set out the structured test of proportionality that has now been endorsed by a majority of the High Court and identify the role of facts within this test. This leads to the question of how courts should go about determining such facts, and the extent to which courts can or should be informed and their decisions influenced by deliberations undertaken by parliaments as to these matters. The Australian High Court’s recent jurisprudence reveals a growing awareness of the fact-sensitive nature of the proportionality inquiry, but leaves significant unanswered questions about the way that a court should engage with parliamentary deliberations about such facts. To understand the dynamics of this interface between the courts and parliaments, we draw upon two conceptual frameworks: the role of democratic and empirical institutional competency and the distinction between ‘first-order reasons’ and ‘second-order reasons’ for institutional restraint. Here we explain these two key frameworks, and then return to them in Part IV of this article as a basis for explaining our spectrum of inter-institutional relations.

While the High Court had previously prevaricated about the proper place of ‘structured proportionality’ in constitutional review, in late 2015 a slim majority of four justices in McCloy v New South Wales endorsed a three-part test in the context of assessing limitations on the implied freedom of political communication.[4] This test developed the second limb of the Lange test. The first limb of the Lange test, as it was in 2015, provided that an initial question be asked: ‘First, does the law effectively burden freedom of communication about government or political matters either in its terms, operation or effect?’[5] If the answer was yes to this question, the second limb of the Lange test asked:

if the law effectively burdens that freedom, is the law reasonably appropriate and adapted to serve a legitimate end the fulfilment of which is compatible with the maintenance of the constitutionally prescribed system of representative and responsible government.[6]

In McCloy, French CJ, Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ, writing jointly, revised the second limb of that test to include what is now referred to as ‘proportionality testing’.[7] This new test involved, as part of asking whether the law is ‘appropriate and adapted’, analysing whether the impugned law is:

suitable — as having a rational connection to the purpose of the provision;

necessary — in the sense that there is no obvious and compelling alternative, reasonably practicable means of achieving the same purpose which has a less restrictive effect on the freedom;

adequate in its balance — a criterion requiring a value judgment, consistently with the limits of the judicial function, describing the balance between the importance of the purpose served by the restrictive measure and the extent of the restriction it imposes on the freedom.[8]

Since McCloy, this structured approach to proportionality has continued to be endorsed by a majority of the Court, with Nettle J and Edelman J recently confirming support for the test.[9] Given this majority support, it is this test of structured proportionality that forms the focus of our analysis in this article, although we suggest that similar issues will arise however the test of validity is framed.[10]

The High Court’s adoption of structured proportionality testing reflects a growing global spread of proportionality, although in Australia it has emerged in a context that is less explicitly rights-based.[11] While there are some Australian modifications, the three-part test adopted in McCloy contains the same analytical structure as the European test, first developed in Germany and now adopted across a variety of jurisdictions.[12] While the spread of proportionality has been accompanied by a wealth of academic scholarship, until recently there has been relatively little interest in the necessity of ‘fact-finding’ within this test.

Yet, on closer examination, it is apparent that at each of the three stages of suitability, necessity and adequate balancing, a court must proceed on the basis of certain empirical assumptions.[13] In other words, underpinning a court’s legal conclusion about whether a particular measure meets the proportionality test, there are various questions of fact. The relevant facts will include, for instance, facts about the purpose underpinning the law, how the law operates in practice, its likely consequences or effects, the availability of alternative measures, and their efficacy. These are the substantive constitutional facts that will affect how courts determine the constitutional questions required of it in the Lange/McCloy test.[14] How these facts should be ascertained by courts remains unclear, and the Australian High Court has not articulated, or followed, a consistent approach to this issue.

The problem of ascertaining facts invites consideration of a further question, which is the focus of this article: in determining whether the proportionality test has been met, how much weight should courts give to parliaments and their fact-finding and deliberations on these questions? If a court does give weight to parliamentary fact-finding and deliberations, further questions arise about how the court will be satisfied that the parliament itself has engaged with the relevant factual issues. These might be understood as questions of procedural fact.

Two recent cases from the High Court demonstrate the current lack of clarity in this area.[15] In Unions NSW v New South Wales [No 2], as foreshadowed above, the failure of the New South Wales (‘NSW’) Government to undertake further enquiries about whether third-party campaigners could reasonably present their campaigns within the revised limit of $500,000 ultimately proved critical.[16] While noting that a parliament generally does not need to provide evidence ‘to prove the basis for the legislation which it enacts’, the joint judgment in Unions NSW [No 2] observed that the position with the implied freedom was different, and a parliament was required to demonstrate that any effective burden on the freedom was justified.[17] The NSW Government’s failure to prosecute further enquiries, which had been recommended by the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters, meant that NSW had not justified the revised limit on expenditure.[18] As Nettle J remarked,

‘[i]t is as if Parliament simply went ahead and enacted the Electoral Funding Act without pausing to consider whether a cut of as much as 50 per cent was required’.[19] The case raises not only the more general question of how the High Court engages with the fact-finding processes and deliberations of the political branches, but also whether these branches have a burden of justification that they must meet procedurally to satisfy a future court on judicial review.

This lack of parliamentary deliberation, in circumstances where there had been a specific parliamentary recommendation for greater consideration, can be contrasted with the subsequent 2019 case of Clubb v Edwards; Preston v Avery.[20] In that case, the High Court had before it various evidentiary materials that demonstrated the factual basis upon which the Victorian Parliament and subsequently Tasmanian Parliament had each deliberated and ultimately legislated to provide safe access zones around abortion clinics. These included, for example, second reading speeches and debates, a Statement of Compatibility tabled by the Victorian Parliament, evidence from a psychologist regarding the effect of harassment on those seeking access to abortions, and other experiential evidence provided to the High Court by an amicus curiae.[21] This material indicated that the zone of 150 metres was chosen after consultation with the relevant stakeholders, and that the introduction of the safe access zones would have a positive effect on patient and staff wellbeing.

The High Court majority relied on these materials in deciding that the burdens imposed by the Victorian and Tasmanian legislation could be justified.[22] However, there was little express clarification of whether such evidence of parliamentary deliberation is always required. Unlike in Unions NSW [No 2], where a number of members of the Court emphasised that it was for the defendant to demonstrate that a law was appropriately justified (including by adducing relevant evidence),[23] in Clubb v Edwards these issues were largely unarticulated. For the joint judgment, the lack of evidence produced by the claimant Ms Clubb about the efficacy of on-site protests was used as a means to distinguish Brown v Tasmania.[24] Nettle J, who engaged most extensively with the factual material, took the view that notions of burden of proof and persuasion are ‘largely misplaced’ in this context.[25]

Clubb v Edwards and Unions NSW [No 2] demonstrate that the question of the extent to which the High Court, in assessing proportionality, will probe a parliament’s own deliberations of the relevant issue remains largely unarticulated under the Court’s current approach. For instance, these cases raised, but left largely unanswered, whether there is a burden of justification that a parliament must meet on passing such measures, and present these procedural facts to the High Court, and how the Court can and should treat parliamentary materials. In other jurisdictions where proportionality testing is used, largely in the context of rights protection, the relationship between the courts and parliaments is often approached through the framework of ‘deference’ or ‘restraint’. In broad terms, this refers to the process of the courts giving weight, or latitude, to the decisions of other branches of government.[26] Elsewhere, the question of whether and how courts ought to afford such weight have been the subject of lively and extensive academic debate.[27] From this literature it can be seen that there are a number of different grounds upon which courts may assign weight to the decisions of governments, including both normative and empirical grounds.[28]

Normative reasons reflect the legislature’s democratic authority, which suggests it is in a more appropriate institutional position than the courts to investigate and determine contested questions of policy and to make the necessary value judgments. Empirical deference, on the other hand, reflects the legislature’s particular institutional competence or expertise to determine the factual issues raised by proportionality.[29] This has a number of aspects. The first is that the legislature’s inquisitorial powers mean that it might be able better to inform itself of the facts relevant to assessments of proportionality. The second is that the legislature might be able to seek the views and assistance of relevant experts and expertise to inform that decision-making. The third is that the legislature might institutionally be better suited to the polycentric decision-making often required in policy judgments around necessity and balancing.

Another distinction that can assist in understanding the inter-relationship between courts and parliaments in the context of deference is the idea of ‘first-order reasons’ and ‘second-order reasons’ for institutional restraint. Chan, writing in the context of the Human Rights Act 1998 (UK), has explained these in terms of a distinction between the substance or merits of a decision (first-order reasons) and concerns of institutional competence or democratic legitimacy (second-order reasons).[30] Second-order reasons indicate that, even if a parliament did not get the merits or substantive issues correct (in the court’s view), nonetheless the court should still defer to parliament because of its democratic and empirical institutional competence.[31] Chan argues that with both types of reasons, if the court is to exercise institutional restraint, it should only do so if the reasons are supported by evidence. In other words, institutional competence and legitimacy should not simply be assumed, but before exercising restraint the court should review the degree to which the legislature actually has the specific competence or expertise to decide a particular issue.[32]

In Australia, despite the similarities in inquiry and institutional settings, the concept of ‘deference’ has been rejected by the High Court on the basis of the responsibilities of the judicial role. In McCloy, the plurality explained its understanding of the judicial role in the following terms:

The courts acknowledge and respect that it is the role of the legislature to determine which policies and social benefits ought to be pursued. This is not a matter of deference. It is a matter of the boundaries between the legislative and judicial functions.[33]

In Unions NSW [No 2] this approach was confirmed, and the High Court expressly rejected the submission by NSW that the capping of electoral expenditure is ‘reserved to the Parliament and not subject to scrutiny by the Court’.[34] As Wesson explains, although the Court correctly rejected this form of ‘submissive deference’, by rejecting any role for deference, it may have ‘overstepped’ the mark.[35] As the deference literature from other jurisdictions illustrates, when allocating weight to decisions made by governments, there are a range of different approaches that courts may take.[36] One concern arising from the High Court’s outright rejection of deference is that there has been little space — academically and judicially — to consider how the Court can or should be informed by and evaluate parliamentary fact-finding and decision-making processes. It is this inquiry that we turn to next.

Unlike in the US, Australian constitutional scholars have not engaged in heated debates over the legitimacy of judicial supremacy. Since before Fullagar J’s observation in the Communist Party Case that the principle in Marbury v Madison was ‘axiomatic’,[37] it had long been accepted that the ultimate arbiter of constitutional meaning is the High Court of Australia.[38] The reasons for this must be multi-factorial, including that our colonial heritage, which was never discarded through revolutionary schism, already accepted a settled role for courts in determining validity of legislative enactments. This was able to continue into independence under a constitutional document that gave little power to the judiciary to determine highly contested rights-based issues, where contentious policy questions require balancing of rights against each other, and against other government objectives. Indeed, in more contemporary Australian debates over a bill of rights, concerns about the appropriateness of judicial engagement in such exercises have given rise to claims of ‘undemocratic’ or ‘unelected’ judges and counter-majoritarianism, an issue that had previously not garnered much attention.[39]

Perhaps because judicial supremacy has never really been under any threat in Australia, there has been little, if any, serious commentary agitating for a separate, and possibly duelling interpretative authority located in the political branches of government. In the US, by contrast, under what is known as ‘departmentalism’, or ‘coordinate construction’,[40] scholars and practitioners have advanced a theory in which each branch of government — judicial, executive and legislative — engages in its own autonomous interpretative struggle with the Constitution. At their core, departmentalists believe that each branch has a separate and independent obligation to the Constitution, and that each branch has its own institutional authority to interpret it unshackled by the interpretations of other branches. Of course, departmentalists exist in different guises, or, as some might say, at different levels of extremity: some would argue that the interpretations of the political branches should receive equal institutional respect to those of the judicial branch, setting the branches up for an ongoing constitutional power struggle.[41]

Even if one rejects this extreme positioning, there are two key insights that emerge from theories of departmentalism that are instructive in the Australian context. On the one hand, it must be true — and we see it manifest, for instance, in the oath of Ministers and parliamentarians — that each branch has independent obligations to act in accordance with the Australian Constitution. As a factual matter, we know that as executive officers and parliamentarians go about their day-to-day business of developing, legislating and implementing policies, they engage regularly in statutory interpretation and, somewhat less regularly, but still often enough to be significant, in constitutional interpretation. Often these engagements will be ungoverned by judicial precedential authority, and often they will never be challenged in the courts. In these areas, at least, the political branches not just do, but must, engage in constitutional interpretation outside the immediate precedential guidance of the courts, and often it is their interpretation that will be, de facto, the final word on the issue. Where there is judicial authority, the legislature must navigate that precedent, which might provide greater or lesser certainty to guide their actions, and they should consider constitutional risk as part of their broader deliberations.[42]

On the other hand, a second insight from departmentalism, which has been developed for instance by Tushnet,[43] and Waldron,[44] is that the non-judicial branches bring a unique institutional perspective to the task of constitutional interpretation. This pulls us in a slightly different direction, revealing that there should be a more complicated relation between the branches than simply accepting the supremacy of judicial review or asserting autonomous, unrelated departmentalism. This is not just about the spaces in constitutional law where the political branches are de facto the ultimate arbiter of the Constitution because the court has not entered that space, or where there is constitutional uncertainty so that there is no clear guide for their actions. Rather, it involves spaces in which judicial and political branches are both operating, but where questions of interpretation arise that might be better suited to the institutional competencies of one branch than another. Lazarus and Simonsen explain that it is in these spaces that the possibility arises that the branches might engage in such a way as to complement and enhance the institutional strengths of each other.[45]

It is those points of inter-institutional intersection that, we think, require greater study. In this article, we look at one example of that intersection: where the Australian High Court has developed constitutional doctrines, such as proportionality, that require consideration of facts and evidence in order to reach a conclusion.[46] In other jurisdictions, proportionality has tended to arise predominantly in a rights setting, whereas in Australia, it has arisen in relation to structural limitations such as the implied freedom of political communication, s 92 of the Australian Constitution, and characterisation of federal purposive powers.[47] In this article, we consider the Court’s implied freedom jurisprudence, where the proportionality doctrine is at its most developed. As we have explained in Part II, in this area the High Court’s jurisprudence recognises the tension involved: that it remains the Court’s role to be the final arbiter of constitutional validity, but that its role is not to supplant the legislature’s judgment relating to what are ultimately policy judgments, which are better suited to the legislature’s institutional competencies.

Where the judicial and political branches are operating in the same constitutional space such as this, if exercising appropriate inter-institutional respect, they can also work to reinforce the strengths of each other’s position. For instance, in relation to proportionality, it has been said that judicial review of legislative rights-choices can enhance the legislature’s ‘culture of justification’.[48] This promotes the openness of the legislature’s decision-making to the public, thus producing a more transparent and accountable relationship between the legislature and the people.[49]

In the remainder of this article, then, we consider two key questions that arise in relation to the inter-institutional relationships between the High Court and parliaments around facts and proportionality. The first is: what does the High Court’s claim to exercise restraint mean? What level of scrutiny will, or should, the High Court engage in to maintain its proper role while providing inter-institutional respect for the legislature’s role? The second is: within that proper role, how can the High Court best promote a culture of justification in the legislature and in this way improve the foundations of representative and responsible government? To answer these questions, we develop a spectrum of inter-institutional relations, which provides a model for analysing the various ways in which courts and the parliaments might intersect.

In this Part, we set out in detail a spectrum of approaches, arguing that there is, or should be, an intersection between the roles of the courts and parliaments in proportionality analysis.[50] This intersection may be both relational and iterative, depending on the position on the spectrum. What we mean by relational and iterative is that how a parliament engages in its own institutional space with proportionality analysis can impact on how courts themselves perform the relevant proportionality analysis. How a court approaches proportionality testing and its response to a parliament’s engagement might then, iteratively, affect future parliamentary engagement. In developing this spectrum, we draw upon some comparisons with other jurisdictions where, in the context of proportionality testing, this interrelationship has been more explicitly analysed.

Any inter-institutional relationship between the courts and parliaments will raise complex questions of the extent to which the judicial branch can inquire into the proceedings and deliberations of the legislative branch, and the extent to which it can take evidence of, and probe, what has occurred in a parliament. These are the procedural questions of fact that we refer to above. Of course, procedural questions such as this raise questions of parliamentary privilege. It is not possible in this article to provide a full analysis of this issue, but we rely on that performed by Kavanagh in the United Kingdom (‘UK’) context.[51] She draws the helpful distinction between the ‘quality of the substantive reasons’ offered by MPs during parliamentary debate, and the ‘quality of the decision-making process in Parliament’.[52] We agree with Kavanagh that a focus on the quality of decision-making process of a parliament, and not the substantive decision of a parliament itself, allows courts to avoid parliamentary free speech issues under art 9 of the Bill of Rights 1689 and to avoid intruding into matters covered by parliamentary privilege.[53] Below, we will further explain how this is achieved across the different positions on our spectrum of approaches.

Our spectrum seeks to articulate different positions that courts may adopt in relation to scrutinising a parliament’s decisions on a particular legislative measure. Our approach at this stage is analytical. We are attempting to explain what the positions on the spectrum would require of the judiciary and the implications for parliaments. In that respect, we explain in each position, for instance, how the judges might approach the different stages of proportionality testing based on that level of restraint. Some of the positions, we acknowledge, are hypothetical in the sense that it would be hard to imagine a court explicitly following such an approach. We are not, in this Part, suggesting they are all plausible or defendable positions for a court to take. We return to this in Part V of the article where we develop a normative claim about where the High Court ought to position itself on this spectrum.

The key points along our spectrum can be described as illustrated below in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Proportionality on a spectrum of inter-institutional relations

The position of full restraint reflects an acceptance by the judiciary of the democratic and empirical institutional superiority of parliaments without subjecting it to any further review. It accepts the superior institutional competencies of legislatures as a normative claim that is unable to be scrutinised. In other words, a court adopting this position would accept the legislature’s assessment (as to a particular measure being justified) as correct, without undertaking any independent review. Kavanagh has explained this as judicial respect for the views of the legislature as meaning ‘the decision embodied in the statute itself’.[54]

Because of its absolute and blanket nature, this will result in judicial restraint across all three stages of proportionality testing. This is sometimes described as ‘submissive deference’[55] or even ‘abdication’,[56] as the court has no substantive or effective review function. Under this position, the legislature has no burden of justification to meet to convince the court that it has engaged in the necessary fact-finding processes and undertaken the relevant deliberations. The legislature’s superior competence is assumed, and the court relies on no evidence to substantiate the normative superiority of the legislature. The court makes no inquiry into the procedural or the substantive decisions of parliament, thus raising no questions of parliamentary privilege.

Under this position, the judiciary is concerned with whether there is some evidence that the legislature itself has engaged in relevant fact-finding and deliberations, but the court continues to exercise considerable restraint. The extent of evidence relates only to the fact of some fact-finding and deliberation and the court is not concerned with reviewing the legislature’s first order reasons (relating to the merits of the particular case). The court exhibits a continued acceptance of the democratic institutional superiority of the legislature, but subjects the empirical and institutional superiority of the parliament to some, albeit very limited, review. This might even be described as ‘tick-a-box’ review.[57]

Under this position, the court must have some evidence before it to satisfy itself that there has been some legislative fact-finding and deliberation with respect to the relevant proportionality inquiries. This will need to be made available to the court by way of evidence of the public deliberations of the parliament, for instance in:

• explanatory memorandum, second reading speeches and debate in the parliament;

• the work of parliamentary committees that support the Houses and parliamentarians (including submissions and evidence received by these committees and their reports);[58] and

• other material considered by the parliament (such as, rights-related statements of compatibility, reports of other bodies such as anti-corruption commissions, law reform bodies or royal commissions).

The court does not, however, evaluate the actual evidence that was before the legislature or the substance of the legislative deliberations. It does not, therefore, inquire into the substance of the parliamentary decision-making, thus avoiding inquiring into parliamentary deliberations in a way that would pose difficulties for parliamentary privilege. The court is not even, at this position on the spectrum, concerned with whether all relevant facts and expertise were considered by the legislature, or with whether the legislature’s final decision suffers from unreasonableness or irrationality. Under this position, therefore, the courts are looking for a very low level of justification from parliaments: that it has engaged in the processes at all.

Under this type of review, the actual restraint afforded may differ across the three stages of proportionality testing. As explained in Part II above, the nature of the inquiries (and the types of factual determinations required) are different at the various stages of the proportionality inquiry. This means that the level of restraint may differ in relation to the different stages of the inquiry. For instance, if there is some evidence of parliamentary deliberation about the suitability of a law, but no evidence that questions of reasonable necessity and balancing of means and ends were considered at all, the court might exercise restraint in terms of the first stage, but not the second and third stages of proportionality.

Under this position, the court undertakes a robust procedural review of the legislative process (namely, the extent to which a parliament itself has considered the relevant inquiries in the proportionality analysis). That is, the court scrutinises the empirical and institutional claims to competence of the legislature, the second-order reasoning. In Hunt’s words, the respect of the court must be ‘earned’ by the parliament.[59] The court will consider whether the legislature has gone through a robust and thorough process in which all relevant facts and expertise were before the legislature to inform its decision-making.

The distinction articulated by Kavanagh, that we referred to above, between the ‘quality of the substantive reasons’ offered by MPs during parliamentary debate, and the ‘quality of the decision-making process in Parliament’ is particularly helpful to understanding Position 3.[60] This position requires an evaluation only of the quality of parliament’s decision-making process; that is, its fact-finding processes and the processes it has deployed in its deliberations. It does not require an evaluation of the merits of the analysis contained in the deliberations or whether the outcome of those deliberations reasonably follows from these processes.[61] Because the decision-making process is the concern of the court, Kavanagh argues that it will avoid judicial intrusion into areas protected by parliamentary privilege.[62]

This position requires the court to have the extensive evidence before it of two matters:

(a) Evidence of the public deliberations of the parliament to understand the full scope of the legislative inquiry and deliberation (including the materials noted above on page 273 in relation to Position 2). In a case before the court, this material is likely to be led by government parties, as they will have better knowledge of and access to it.[63]

(b) Other evidence that enables the court to evaluate the robustness of the parliamentary inquiries, remembering that the court is evaluating the processes and form, but not the substance, of any deliberations. The types of questions the court might ask, for example, could include: how thorough were the parliamentary investigations and deliberations? Were there other relevant facts that were overlooked by the parliament? Or is the parliament’s interpretation of the evidence disputed by other experts whose views were not considered by the parliament? The type of evidence that would help the court answer these inquiries might be led, for instance, by non-government parties to the litigation or amicus, to demonstrate that the parliament did (or did not) have all the relevant facts and expertise before it.[64]

This represents a much more robust scrutiny of second-order reasoning than evident in Position 2, particularly with respect to the asserted empirical superiority of parliament. The court remains, however, restrained as to its review of the democratic superiority of parliament, as well as undertaking no review of the merits of the decision (the first order reasoning of parliament). As with Position 2, the actual judicial restraint that is afforded to parliament may differ across the three stages of proportionality testing. Again, this will depend on evidence of the robustness of the legislative deliberative process relevant to each stage of the inquiry.

Position 3 on the spectrum therefore involves a higher level of scrutiny than Positions 1 and 2, but it is still process-driven. In this way, it brings to the fore the possibility of a productive iterative inter-institutional relationship between the courts and parliaments. It gives the courts a role in what Curtin has referred to in the European Union context as ‘prodding’ parliaments:

Courts ... have some role to play in prodding parliaments (and executive actors) to be more open and responsive. Both sets of actors—courts and parliaments—have distinctive but complementary roles to play in ensuring that systems of representative democracy are not further hollowed out or blacked out ...[65]

Lazarus and Simonsen have referred to a similar idea in the UK context under the rubric of ‘deference’, noting its ability to create an iterative relationship that enhances democratic processes:

[R]igorous and respectful judicial examination of democratic processes enhances constitutional dialogue, increases the opportunities for judicial deference, heightens the transparency with which deference is exercised and therefore makes it more likely that deference will be accorded where it has shown to be justified.[66]

In the Australian context, Appleby and Howe have explored the idea of ‘prodding’ in relation to the High Court’s decision in Williams v Commonwealth (No 1).[67] They have suggested, in particular, that there might be a shift in the Australian judiciary’s embrace of a function of ‘prodding’ the Parliament to achieve stronger scrutiny and accountability, and that this might assist the functioning of a system of representative and responsible government.[68]

The form of process review that is proposed under this position has many similarities with the review that is evident in decisions of the European Court of Human Rights (and other European trans-national and domestic courts) and has been referred to as a ‘procedural approach’, particularly evident in proportionality analysis.[69] In that context, while not abandoning substantive review, the courts appear to also be incorporating procedural review into their reasoning (and we explore the possibility of a combined approach in Position 4, discussed below).

Evans v United Kingdom was a challenge under the European Convention on Human Rights (including the right to life and right to private and family life) to a UK law that allowed a man to withdraw his consent to his former partner’s use of embryos that had been created jointly by them.[70] The Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights held that there had been no violation of the Convention, observing that it was ‘relevant’ to their inquiry that the legislation

was the culmination of an exceptionally detailed examination of the social, ethical and legal implications of developments in the field of human fertilisation and embryology, and the fruit of much reflection, consultation and debate.[71]

This became a vital part of the Court’s acceptance that the UK Parliament had fallen within the appropriate margin of appreciation afforded to domestic legislatures.

The European Court of Human Rights has also used a failure of deliberation as a basis for finding a violation of Convention rights. In Hirst v United Kingdom (No 2), the Court was asked to assess the compatibility of a blanket ban on prisoners voting against the right to free elections.[72] The Court observed that there was no evidence that the UK Parliament ‘ever sought to weigh the competing interests or to assess the proportionality’ of the blanket ban on the right of convicted prisoners to vote.[73] The Grand Chamber noted that the issue had been considered by a multi-party Speaker’s Conference on Electoral Law in 1968 and a Working Group, and that Parliament had, by its vote, ‘implicitly affirmed the need for continued restrictions on the voting rights of convicted prisoners’.[74] Notwithstanding this, however, the Court was not satisfied that there had been any substantive deliberation by the Parliament about the ‘continued justification in light of modern-day penal policy and of current human rights standards for maintaining such a general restriction’.[75] Accordingly, the Court held that there had been a violation of the applicant’s Convention rights.

More recently, in 2013, the European Court of Human Rights in Animal Defenders International v United Kingdom upheld a UK blanket ban on political advertising in the broadcast media as a proportionate restriction of the freedom of expression.[76] This was so even when it affected the ability of NGOs (non-government organisations), such as Animal Defenders International, to communicate with the public. In coming to this decision, the Court gave significant weight to the legislative deliberation about the issue. In its most explicit explanation of what type of legislative deliberation would inform its inquiries, the Court said:

The prohibition was ... the culmination of an exceptional examination by parliamentary bodies of the cultural, political and legal aspects of the prohibition as part of the broader regulatory system governing broadcasted public-interest expression in the United Kingdom and all bodies found the prohibition to have been a necessary interference with Article 10 rights.[77]

In particular, the Court in Animal Defenders International emphasised the ‘particular competence of Parliament and the extensive pre-legislative consultation on the Convention compatibility’ that the UK Parliament had undertaken, which helped to explain the degree of deference that the domestic courts had afforded to the legislative prohibition.[78] The Court also noted that the proportionality of the prohibition had been extensively debated before the domestic courts, both of which had carefully addressed the relevant Convention case law and principles.[79] Ultimately, the Grand Chamber attached ‘considerable weight to these exacting and pertinent reviews, by both parliamentary and judicial bodies’.[80]

The European Court of Human Rights thus appears increasingly comfortable with affording a level of restraint where there is evidence of robust parliamentary review (coupled with other factors in its decision-making process). It also appears comfortable with the onus on the legislature to demonstrate that it has undertaken this review before it passes legislation. It is not reticent in explaining that this occurs, and in elaborating on what it considers appropriate deliberation. It is important to note that even within the Court this is still not a universally accepted approach. The two dissenting judgments in Animal Defenders International made it clear that while procedural review might inform substantive review by the Court, it should not replace it.[81]

Two main questions have arisen in relation to this procedural trend in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. The first is what is the appropriate standard against which legislative process should be measured? What criteria should a court adopt when it engages in procedural-based review? Lazarus and Simonsen point out that this is a fundamental question that must be answered if the judicial review is to enhance democratic deliberation by the legislature. They explain that ‘[t]he clearer the criteria and the better the reasoning used by the courts when taking a view on the democratic deliberative process, the greater the potential for focused democratic dialogue between the arms of state.’[82] In a similar vein, Kende has also warned that too minimalistic a model, or standard, of process review may lead to a form of ‘tick-a-box’ review.[83] For instance, if legislatures start to adopt a ‘boilerplate’ model of deliberation that has been approved by the Court,[84] this would again undermine the objectives of procedural review.

The second question is the extent to which a procedural-based review model can adequately protect rights without being coupled with robust substantive review.[85] Many scholars have accepted this concern, and proposed models of review that, therefore, require the relevant court to engage in both procedural and substantive review of the proportionality analysis.[86] We turn to consider this combined model of review below when we explain Position 4 on our spectrum.

Potential Consequences of Position 3

When a court engages in process evaluation, a number of different consequences might arise. These potential consequences depend on the court’s findings in relation to the legislature’s process, but also the court’s appetite to undertake a full evaluation of the inquiries if it has found that the parliamentary deliberations on the substantive issues are lacking.

In relation to Position 3, there would appear to be three options available to a court if it is not satisfied with parliament’s legislative fact-finding and deliberations. The first is that the court could engage in its own substantive merits deliberation of the proportionality of the measure, informing itself as necessary (and where available) of relevant constitutional facts, in order to determine whether — despite failings in the legislative process — the legislature has nonetheless come to a constitutionally satisfactory conclusion as to proportionality. If the legislature’s decision accords with the court’s position, it would be left to stand. If it does not, the court would strike the relevant legislative provisions down as invalid. Under this position, the court conducts a review of the legislature’s process, and if it finds that insufficient, conducts its own independent assessment of the merits of the structured proportionality test. The difficulty with this option (which is returned to below), is that the court may not be able to access the necessary constitutional facts to perform its own independent assessment of the merits.

This then gives rise to a possible second option: what happens if the court is unable to be satisfied of proportionality because of a lack of sufficient evidence available to it? In practice, this is more likely to be the case where the parliament has not engaged in a robust investigative and deliberative exercise. In such a scenario, we suggest, the court may invalidate the provision. It would appear to be for this reason that the High Court found invalid the provision in Unions NSW [No 2]. The Court’s decision appears based not simply on the fact that the Parliament had not engaged in a further inquiry — that is, that the Parliament has met the burden of proving fact finding and deliberation has occurred — but because it was not able to access the necessary evidential material that such a further inquiry would have produced.[87]

The third option is that if the court is not satisfied that the legislature has engaged in a robust fact-finding and deliberative process, the court may invalidate the provision without itself undertaking a substantive deliberation of the merits involved. If the court were to take this option it would create not just an incentive for parliament to engage in fact-finding and deliberation, but a burden to do so. Because there is no judicial conclusion on the substantive merits, it would appear that a judicial finding of invalidity on this basis does not prevent a future parliament from re-enacting the same provision, with a more robust and informed deliberation as to its justification.

Position 4 is closely related to Position 3, but it contains an extra evaluative step by the court. It is also, as we argue in Part V below, the most normatively defensible position, at least in the Australian constitutional context. Under this position, as with Position 3, the court undertakes a robust scrutiny of the legislature’s processes and fact-finding, ensuring that claims as to institutional and empirical legitimacy of the legislature are made out in a particular case. In other words, these claims to legitimacy must be supported by evidence, meaning that as with Position 3, the court will require extensive evidence to be satisfied that the parliament has undertaken a sufficiently comprehensive process.

In contrast to Position 3, there is also what might be described as a ‘backstop’ of judicial review of the outcome of the legislature’s fact-finding and deliberation against a standard of unreasonableness. The court does not end its inquiry after the review and evaluation of the parliament’s processes (as it does in Position 3). It also asks whether, based on all of the relevant facts and information, the parliament’s decision was nonetheless reasonable. This is not a review, in Kavanagh’s words, of the ‘quality of the substantive reasons’ that informed the parliament’s decisions, but, rather, a fresh review of the reasonableness of the final decision.[88] As for the standard of the review to be applied, the court might helpfully draw upon the standards developed in relation to unreasonableness in administrative law.[89]

As with Positions 2 and 3, we may see judicial restraint differing across the three stages of proportionality testing, depending on the quality of the deliberative process relevant to each stage of the inquiry.

Potential Consequences of Position 4

As explained above, under Position 4 the court undertakes an extra evaluative step, whereby it examines the substantive outcome of the legislature’s decision-making against a standard of unreasonableness. There are a number of different consequences that might flow from Position 4, which arise depending on the court’s findings in relation to whether both stage one (process evaluation) and stage two (reasonableness) have been met.

The first option (robust parliamentary process not affected by unreasonableness) is where the court is satisfied that the parliament undertook a robust process (that is, conducted relevant inquiries and considered all relevant facts) and, based on that process, did not make an unreasonable decision. In this scenario, satisfied of both the first and second order reasons for restraint, the court will not interfere with the resulting parliamentary decision.

The second option (robust parliamentary process but affected by unreasonableness) is where the court is satisfied that the parliament undertook a robust process, but nonetheless made an unreasonable decision. In this scenario, satisfied of the second order reasons, but not the first order reasons, the court will find the legislative provisions invalid. The legislature has an opportunity to reconsider the issue, but will not be able to come to the same policy choice, as it has been found to be affected by unreasonableness.

The third option (insufficient parliamentary process) is where the court is not satisfied that the parliament undertook a robust process. In this scenario, the court is left in the same position as it was under Position 3. That is, it might nonetheless go onto consider the merits of the proportionality questions, and determine whether the final parliamentary decision was nonetheless constitutionally permissible. It might find the provision invalid simply on the basis of insufficient process. Or, as is more likely, it might take the second option outlined above, that is, where it will attempt to undertake its own evaluation of the proportionality test, but where there is insufficient evidence available to it, it may find the provision invalid. This would not necessarily preclude parliament from re-enacting that provision following a more robust process that is informed by the necessary evidence to justify the provision.

The final position, of no restraint, reflects no acceptance by the court of the democratic and empirical institutional superiority of parliaments. As such, the court affords legislative deliberation no inter-institutional respect at any stage of the inquiry. Instead, the questions to be answered under structured proportionality testing are to be determined by the court alone. It might be that the court is informed in answering those questions by evidence that has been led before parliament (particularly if the court is able to gain only limited access to relevant facts to inform itself about these matters), but the court will exercise no restraint with respect to the consideration of that evidence by the parliament itself.

In this Part of the article we develop our main normative claim, outlining where we think the Australian High Court ought to position itself on our spectrum of inter-institutional relations. In the previous Part we outlined the major features of each of these positions, and here we explain why Position 4 (‘Process Evaluation + Unreasonableness Review’) is the most desirable and defensible position for the High Court. This position is the approach most consistent with the Court’s constitutional obligations, as well as the Court’s understanding of judicial power and its limits.

The High Court, as is well-known, is the final arbiter of the Australian Constitution. As well as being a final court of appeal, its task is to settle constitutional disputes and to provide authoritative guidance on the interpretation of the Constitution. In addition, however, as we have explained in Part III, when viewed from a broader inter-institutional context, the Court’s obligations also include a role in ‘prodding’ the political branches to meet their own constitutional commitments.[90]

In Australia, of course, any discussion of the High Court’s institutional role must also be informed by the Court’s jurisprudence on the protections that must be afforded to courts under ch III of the Australian Constitution. Although some separation between the branches was envisaged by the framers of the Constitution, the High Court has interpreted the separation between the judicial and political branches of government particularly strictly. This interpretation prohibits, subject to certain exceptions, any ‘mingling’ of judicial and non-judicial functions.[91] In the context of proportionality review in Australia, there has also been the concern that such an inquiry will invite judicial incursion into the ‘merits’ of legislative design, which is considered to be outside the accepted limits of the judicial role.[92]

In assessing whether burdens on the implied freedom can be justified, the Court has an obligation to make a finding about whether a challenged measure meets the second Lange question.[93] As the Court has recently confirmed, the answer to this question is determined by applying the three stages of a structured ‘proportionality testing’.[94] As we have explained in Part II, this requires the Court to make certain findings of ‘constitutional fact’. It has long been accepted that the High Court alone has the duty to find these facts, and that a government cannot ‘“recite itself” into power’ by conclusively declaring the existence of such facts.[95] For instance, High Court Justice Kenneth Hayne, writing extra-curially, has emphasised the need for the Court to identify and find the relevant constitutional facts.[96] Deference, he suggested, can be used to ‘paper over the fact that the courts are unable or unwilling to identify the relevant facts’.[97] This need to make findings of constitutional fact raises, as we have explained in Part II of this article, the question of what weight, if any, the Court should put on parliament’s own investigations and deliberations on these questions.

When we consider the various points on the spectrum in the light of the High Court’s constitutional obligations, it is fairly easy to dismiss the positions at both extremes. For example, under Position 1 (‘full restraint’), the Court simply accepts at face value the parliamentary choice. In other words, it does not scrutinise, at all, whether a parliament itself undertook any deliberations or was informed by evidence in reaching its conclusion. It simply accepts the legislative choice without question. This position would, effectively, deprive the Court of any meaningful review function as it would be acting as a mere ‘rubber stamp’ for parliamentary decisions. This is, patently, not what is contemplated by the division of powers between the three arms of government in the Australian Constitution.

For similar reasons, we suggest that Position 2 (‘non-evaluative restraint’) is also untenable. Although the Court under this position has some review function, its scrutiny of parliament’s choices is minimal. The High Court under this position would inquire into whether Parliament has conducted any deliberations, but the mere fact of deliberation would be the end of the matter. Although this position appears to require some review, in reality it is likely to be a very weak check on parliaments, and would therefore also appear inconsistent with the Court’s constitutional obligations. This would, effectively, amount to a parliament ‘reciting itself into power’ and would deprive the Court of any meaningful review function.

At the other end of the spectrum, it is also easy to dismiss Position 5 as inappropriate. Under this position, it will be recalled, the Court exhibits no restraint and places no weight on the legislature’s own assessment of proportionality. In other words, under this position, the High Court itself assesses the merits of the legislative choice without regard for the parliament’s own assessment or deliberation on the matter. This position, we suggest, not only appears to overstep the limits of the Court’s constitutional role, it is inconsistent with the Court’s previous application of the test, in which the legislature’s processes have had varying implications for the Court’s decisions.

Between these two extremes, however, the position is more nuanced. Positions 3 and 4 both involve the Court undertaking a substantive review of parliament’s fact finding and deliberative processes. Therefore, the High Court will require evidence to scrutinise parliamentary assessment of the proportionality of the legislative measure, and whether this deliberation was informed by appropriate facts. For the Court to undertake this type of review function, it must itself be informed by appropriate evidence. In other words, the High Court cannot properly evaluate a parliament’s processes without some information concerning the facts and circumstances underpinning the legislation. Under both of these positions, then, the Court is not simply accepting that parliaments have superior competence and capacity to answer the relevant questions, but it must be satisfied that this is the case. This resonates with the position taken by Chan that where a court chooses to defer for either first order or second order reasons, it may only do so when there is evidence to justify that deference.[98]

We do not seek to prescribe, here, the types of criteria the High Court might apply to reviewing the processes of parliaments, and what procedural evidence must be led to satisfy the Court of the parliamentary processes. We would, however, say that the criteria adopted by the Court and how these are applied will be important in terms of how parliaments respond. This should be done keeping in mind the objective we set out above: of encouraging parliaments to better engage with their constitutional responsibilities, and to better justify to the public as well as the court the reasons for their decision-making. The Court must not adopt an approach that enables parliaments to respond in a highly formalised manner, as this would risk emasculating rather than deepening parliamentary deliberation. The Court must instead develop criteria that encourage parliaments to engage in holistic and rigorous fact-finding and deliberative processes. In terms of evidence of these processes, we know that the High Court will look at the extent to which governments and parliaments have documented their processes,[99] and that relevant evidence might consist of explanatory memoranda, statements of compatibility, second reading speeches and committee reports. It is also apparent that the Court will be assisted by external sources, such as expert reports and other data.

Both Positions 3 and 4, we suggest, are preferable to the positions at either extreme of the spectrum because they involve robust review of parliamentary deliberations. For instance, under each position the High Court must be satisfied on the evidence that a parliament has undertaken a thorough fact-finding and deliberative process. The difference between these two positions is not always clear, and there is likely to be some overlap. Under Position 3, the Court must review parliamentary process as an initial step. If this process is robust, this will be the end of the Court’s inquiry. If the process is found to be lacking, however, the Court may undertake a further substantive inquiry. Under Position 4, in contrast, the High Court is required to exercise what might be described as the ‘judicial backstop’. This is an extra evaluative step whereby the Court considers whether a parliament’s decision, based on all of the facts and evidence, was reasonable. If the decision was reasonable (even if the Court itself would have determined the matter differently), the Court will not interfere with a parliament’s findings. In other words, it will be satisfied that the legislative measure meets the proportionality test. It is Position 4, we suggest, that is most consistent with the High Court’s obligations to interpret the Australian Constitution — including to make the relevant findings of constitutional fact — and is also within the accepted understandings of the limits of the judicial role.

The proposal in this article has been prompted by various indications in the High Court’s recent implied freedom of political communication cases that the legislature’s fact-finding inquiries and deliberations about the proportionality of legislative measures might bear on how the Court itself determines these issues. While the Court has eschewed a doctrine of deference, the reality of its exercise of restraint in the face of parliamentary decisions begs a number of questions as to the precise relationship between the two constitutional branches in relation to proportionality testing.

In this article, we have formulated a spectrum of positions that might reflect the inter-institutional relationship between the courts and parliaments. We have argued that the most appropriate position for the High Court on this spectrum is one that involves the Court reviewing the robustness of a parliament’s inquiries into and consideration of the proportionality tests, while also having a responsibility to test the reasonableness of the final parliamentary decision. Drawing on the position developed in the UK by Kavanagh, we have argued that limiting its review to the processes undertaken by the legislature allows the Court to take into account a parliament’s actions without reviewing the substantive deliberations themselves, thus leaving intact the sanctity of parliamentary privilege.

What we have not done in this article, and will require further development, is to articulate the standards or criteria against which the High Court will assess parliamentary processes of fact-finding and deliberation. There has been some work done on this in the UK, for instance, with Lazarus and Simonsen proposing criteria that include:

• whether a parliament can demonstrate engagement with the otherwise unrepresented voices of the minority;

• the quality of the consideration given to the views of rights-bearers in the course of the parliamentary debate;

• whether there was evidence presented to the legislature of the necessity of the measure that restricts or violates rights; and

• a consideration of the nature of the right that the measure impugns.[100]

Kavanagh is less prescriptive, advocating for standards that reflect the concepts of focus, deliberation and participation.[101] As we flag above, any criteria must be carefully developed so as to deepen and not formalise, judicialise, or emasculate legislative deliberation. The criteria must be substantive, and go to the breadth and depth of the legislature’s fact-finding and deliberative processes, not simply to whether they have spoken to the various stages of proportionality in the language adopted by the courts.

[1] Professor, UNSW Faculty of Law and Justice; Director, The Judiciary Project, Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, Sydney, Australia.

Email: g.appleby@unsw.edu.au; ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9755-6803.

† Senior Lecturer, Deakin Law School, Victoria, Australia.

Email: anne.carter@deakin.edu.au; ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2862-4777.

We would like to thank the participants at the 2019 ‘Facts in Public Law Adjudication’ workshop, sponsored by the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, where a version of this article was first presented. We are particularly grateful to Lynsey Blayden, Janina Boughey, Rosalind Dixon, Paul Kildea, Elisabeth Perham, Sangeetha Pillai, Kristen Rundle, James Stellios, Adrienne Stone, Rayner Thwaites, Jason Varuhas and Kristen Walker QC for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this article, and to the referees and editors at the Sydney Law Review for further helpful feedback.

[1] In this article, we refer to ‘parliament’ in the sense of any parliament of the Commonwealth, a State or Territory whose legislation is subject to a constitutional challenge.

[2] In this article, we focus on cases concerning the implied freedom of political communication.

We note that similar questions of fact arise in relation to the freedom of trade, commerce and intercourse in s 92 of the Australian Constitution, where three justices of the High Court have recently endorsed the use of structured proportionality testing: see Palmer v Western Australia (2021) 95 ALJR 299. In the s 92 context it has been more common for the High Court to remit questions of fact to the Federal Court of Australia pursuant to s 44 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). See, eg, Palmer v Western Australia (No 4), where Rangiah J heard evidence regarding the reasonable need for and efficacy of community isolation measures contained in Directions made pursuant to the Emergency Management Act 2005 (WA): Palmer v Western Australia (No 4) [2020] FCA 1221.

[3] See, eg, Unions NSW v New South Wales [No 2] [2019] HCA 1; (2019) 264 CLR 595, 617–18 [48]–[52] (‘Unions NSW [No 2]’). See also Murray Wesson, ‘Unions NSW v New South Wales [No 2]: Unresolved Issues for the Implied Freedom of Political Communication’ (2019) 23(1) Media and Arts Law Review 93; Caroline Henckels, ‘Proportionality and the Separation of Powers in Constitutional Review: Examining the Role of Judicial Deference’ (2017) 45(2) Federal Law Review 181. In a similar fashion, the High Court has eschewed the concept of ‘deference’ in administrative law, although commentators have argued that evidence of deference exist in the case law: Stephen Gageler, ‘Deference’ (2015) 22(3) Australian Journal of Administrative Law 151; Janina Boughey, ‘Re-Evaluating the Doctrine of Deference in Administrative Law’ (2017) 45(4) Federal Law Review 597. Cf the vast literature from other jurisdictions, such as the UK, which is discussed further below in the text accompanying n 27.

[4] McCloy v New South Wales [2015] HCA 34; (2015) 257 CLR 178 (‘McCloy’).

[5] Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [1997] HCA 25; (1997) 189 CLR 520, 567 (citation omitted) (‘Lange’).

[6] Ibid 567. In Coleman v Power, the second question in Lange was modified by replacing the phrase ‘the fulfilment of’ with ‘in a manner’: see Coleman v Power [2004] HCA 39; (2004) 220 CLR 1, 50–51 [93]–[96] (McHugh J), 78 [196] (Gummow and Hayne JJ).

[7] McCloy (n 4) 195 [2] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ).

[8] Ibid (emphasis in original).

[9] See Clubb v Edwards; Preston v Avery [2019] HCA 11; (2019) 267 CLR 171, 264–9 [266]–[275] (Nettle J), 329–45 [461]–[500] (Edelman J). Note that in Comcare v Banerji, proportionality reasoning was applied by the joint judgment of Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane and Nettle JJ, with Edelman J agreeing with this approach: Comcare v Banerji [2019] HCA 23; (2019) 267 CLR 373, [32] (Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane and Nettle JJ);

[188] (Edelman J).

[10] See, eg, Anne Carter, Proportionality and Facts in Constitutional Adjudication (Hart Publishing, forthcoming) ch 6.

[11] For some introduction to this literature, see Aharon Barak, Proportionality: Constitutional Rights and their Limitations (Cambridge University Press, 2012); Moshe Cohen-Eliya and Iddo Porat, Proportionality and Constitutional Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2013); Grant Huscroft, Bradley W Miller and Grégoire Webber (eds), Proportionality and the Rule of Law: Rights, Justification, Reasoning (Cambridge University Press, 2014); Vicki C Jackson, ‘Constitutional Law in an Age of Proportionality’ (2015) 124(8) Yale Law Journal 3094.

[12] Anne Carter, ‘Proportionality in Australian Constitutional Law: Towards Transnationalism’ (2016) 76 Heidelberg Journal of International Law 951.

[13] See, eg, Carter, Proportionality and Facts in Constitutional Adjudication (n 10); Anne Carter, ‘Constitutional Convergence? Some Lessons from Proportionality’ in Mark Elliott, Jason NE Varuhas and Shona Wilson Stark (eds), The Unity of Public Law? Doctrinal, Theoretical and Comparative Perspectives (Hart Publishing, 2018) 373, 380–2.

[14] See above n 8 and accompanying text.

[15] While we focus on these two recent cases, we note the relevance of facts to the Court’s inquiry, and the level of deference that ought to be accorded to the political branches’ processes and deliberations have been considered in earlier cases, eg, ACTV v Commonwealth [1992] HCA 45; (1992) 177 CLR 106, and in the context of s 92, Castlemaine Tooheys v South Australia (1990) 169 CLR 436.

[16] Unions NSW [No 2] (n 3).

[17] Ibid 616 [45] (Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ). See also at 631–2 [94] (Gageler J), 650 [151] (Gordon J).

[18] Ibid 618 [53] (Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ). See also at 633 [100] (Gageler J), 648–51 [145]–[153] (Gordon J).

[19] Ibid 641 [117].

[20] Clubb v Edwards; Preston v Avery (n 9).

[21] See, eg, ibid 472–3 [83], 473 [86], 509 [276], 510 [279], 511 [281], [283].

[22] In Preston v Avery, all judges were satisfied that the burden imposed by the Tasmanian Act was justified: Clubb v Edwards; Preston v Avery (n 9) [102] (Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ); [213] (Gageler J); [325] (Nettle J); [387] (Gordon J); [501] (Edelman J). In Clubb v Edwards, a majority of the Court was satisfied that the burden imposed by the Victorian Act was justified: Clubb v Edwards; Preston v Avery (n 9) [128] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ; [294] (Nettle J). Note that the other judges in Clubb v Edwards decided there was no burden on the facts, and so avoided the need to determine validity: Clubb v Edwards; Preston v Avery (n 9) [153] (Gageler J); [349] (Gordon J); [443] (Edelman J).

[23] See above n 17–18 and accompanying text.

[24] Clubb v Edwards; Preston v Avery (n 9) 203–4 [81] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ) citing Brown v Tasmania [2017] HCA 43; (2017) 261 CLR 328.

[25] Ibid 270 [277]. See also 292 [347] (Gordon J).

[26] See, eg, Cora Chan, ‘A Preliminary Framework for Measuring Deference in Rights Reasoning’ (2016) 14(4) International Journal of Constitutional Law 851, 854; Jeff A King, ‘Institutional Approaches to Judicial Restraint’ (2008) 28(3) Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 409.

[27] See, eg, Murray Hunt, ‘Sovereignty’s Blight: Why Contemporary Public Law Needs the Concept of “Due Deference”’ in Nicholas Bamforth and Peter Leyland (eds), Public Law in a Multi-Layered Constitution (Hart Publishing, 2003) 337, 340; TRS Allan, ‘Human Rights and Judicial Review:

A Critique of “Due Deference”’ (2006) 65(3) Cambridge Law Journal 671; King (n 26), Aileen Kavanagh, Constitutional Review under the UK Human Rights Act (Cambridge University Press, 2009) ch 7.

[28] For an explanation of this distinction, drawing upon the work of Robert Alexy: see Caroline Henckels, Proportionality and Deference in Investor-State Arbitration: Balancing Investment Protection and Regulatory Autonomy (Cambridge University Press, 2015) 35–7; Henckels (n 3) 192–5.

[29] Henckels (n 28) 35–7; Henckels (n 3) 192–5.

[30] Cora Chan, ‘Proportionality and Invariable Baseline Intensity of Review’ (2013) 33(1) Legal Studies 1, 12.

[31] For further discussion, see Cora Chan, ‘Deference, Expertise and Information-Gathering Powers’ (2013) 33(4) Legal Studies 598.