Monash University Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Monash University Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 7 December 2011

The Koori Court Revisited: A Review of Cultural and Language Awareness in the Administration of Justice[1]

Natalie Stroud, PhD Candidate, Faculty of Law, Monash University.

There is currently an over-representation of Indigenous offenders in the Australian prison system. An understanding of the relationship between language and the law is an essential component of the administration of justice, even more so when dealing with disadvantaged offenders. This review is part of a preliminary sociolinguistic study of one of the specialist court programs in Australia which aims to demonstrate that understanding - the Koori Court of Victoria. A key question guiding the review, is to identify whether an awareness of cultural and language difference in the administration of justice has continued to be the focus of this court since its inception in 2002.

Miscommunication can occur between Indigenous offenders and legal professionals in the mainstream legal system, when an assumption is made that because a person speaks English, they understand what is being said. This does not take into consideration cultural and language difference, and disadvantage may occur for an offender who is unable to understand the legal process or communicate his story in his own words.

Cultural and Language Disadvantage

Linguist Diana Eades refers to

the ‘linguistic impact’ that colonization has had on the

Aboriginal people, with most Indigenous languages no longer spoken on a daily

basis.[2] A loss of

their language, culture and lands has resulted in issues of homelessness,

discrimination, unemployment, drug and alcohol

dependence, poor health, lack of

education, and this has contributed to the disproportionately high percentage of

Indigenous Australians

currently in the Corrections System.

Indigenous Offenders in the Australian Prison System

According to

the 2006 Australian Census, the number of people who identified themselves as

Indigenous was around half a million, or

2.5% of the total population of 21

million.[3] When this

is compared with the high number of 6,091 Indigenous people in the Corrections

Systems, or 24% of a total prisoner population

of

25,790,[4] it is clear

that mainstream methods of punishment have not been particularly effective in

rehabilitating a cultural group which has

been seriously disadvantaged for over

200 years.

In spite of Victoria having the lowest imprisonment rate of Indigenous defendants in Australia, Koories[5] are 12 times more likely to be placed in an adult prison, compared with non-Indigenous prisoners. Victoria’s Koori population is young. More than half are aged under 25, and more than a third are under 15 years! Nearly 40% of Indigenous families are sole parent families, compared to 15% of non-Indigenous.[6] Young Koori males and females are over-represented in the Criminal Justice system often with dependent children, and their stories are ones of heartbreak. To incarcerate them, breaks up families and leaves children parentless. It is far preferable to break the cycle of crime and disadvantage by treating the issues that may have contributed to the offence in the first place.

Communication difficulties

Difficulties for Aboriginal speakers in

legal settings have been recorded and analysed in depth by linguists such as

Eades,[7]

Gibbons,[8]

Walsh,[9]

Cooke,[10]

Koch,[11] and Pauwels

et al.[12] Factors

which may contribute to miscommunication in the courtroom include cultural

differences between participants such as an

imbalance of power; formality of the

court process; ideological differences such as assumptions; pragmatic, semantic,

or lexical

differences of discourse; differences in perceptions of politeness,

for example the use of silence; cultural taboos which prevent

the naming of a

deceased person; a question/answer format, which may be difficult for people

used to an oral culture; language accommodation

may be one way, towards the

dominant speaker; ‘gratuitous

concurrence’[13]

may occur, with the defendant answering ‘yes’ to questions, but

meaning only ‘yes, I hear you’.

Indigenous speakers come from a rich cultural heritage of oral languages which involve a different way of thinking. Cultural and language heritage remains embedded in their discourse, with variation in politeness, taboos, terminology used for specific occasions and different words to speak to people in a different relationship. Time and place are described in different ways. To an Indigenous Australian ‘language defines who he is, defines his country’. [14]

The Koori Court of Victoria

The Koori Court Pilot Program was

initiated by the Victorian Government following recommendations made by the

Royal Commission into

Aboriginal Deaths in

Custody[15] that the

legal system be adapted to the cultural needs of Aboriginal offenders and their

communities.[16]

While similar in many respects to other specialist courts in operation

throughout Australia, this model is unique to Victoria, incorporating

the best

features of existing models.

The Koori Court is a sentencing court, under the jurisdiction of the Magistrates’ Court, and one of its aims is to allow greater participation by the Aboriginal (Koori) community in the court process. Deputy Chief Magistrate, Jelena Popovic suggests that ‘the dynamics of the courtroom are changed from the traditional, adversarial process of assertion and denial to the sharing of information and plans to address the defendant’s behaviour’...‘the offender is part of the interaction rather than an observer speaking through their lawyer’.[17]

Eligibility

To be eligible for a case to be heard in adult Koori

courts, a person must be Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander; be charged with

an offence that can be heard in a Magistrates’ Court that does not involve

family violence or sexual assault; live within or

have been charged within, the

boundary area of a Koori Court; plead guilty to the offence; and be willing to

take responsibility

for their actions. Eligibility is widened in the Koori

Children’s court, and may include a ‘not guilty’ plea to

a

criminal charge.

Layout of the Courts

The Koori Courts have been established in

existing court complexes, but all are culturally designed and similar in layout.

A typical

example is the Koori Court in regional Shepparton (Yorta Yorta

country), a well-designed modern court, with Indigenous art on the

walls, and

the medium size room dominated by an oval shaped table in the centre. Three

flags, the Australian, Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander flags, stand

together on poles at the front of the court.

Figure 1: Interior of the Koori Court, Shepparton

Photograph by Simon Greig. Reproduced with the permission of the Law Institute Journal

Vol 79 No 5 Page 41.

The Magistrate is seated at the table, facing front, with the Respected Person or Community Elder on either side (called ‘Aunty’ or ‘Uncle’). To the left of the Elder is the Corrections Officer, then the Police Prosecutor, the defending lawyer, the defendant, then on his/her left, family members and/or support person, and on their left the Koori Court Officer, completing the full circle. The defendant sits directly across the table from both the Magistrate and the Elders. Support agency representatives and extra family members or public are seated around the courtroom but close to participants at the table. The hearing is conducted in an informal manner.

A Koori Court Magistrate would hear around eight or nine cases in a day. Compare this with a mainstream Magistrates’ court, where despite magistrates who are sympathetic to cultural issues, the high number of cases heard per day prohibit time being taken to observe any language and cultural difficulties that may arise. One magistrate could hear around 80-90 cases in one day in this court.

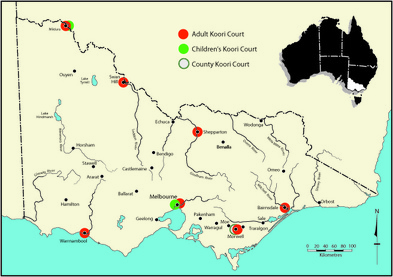

Expansion of the Koori Court Program

Since the commencement of the

first Koori Court in

2002,[18] the program

has expanded to a total of seven Adult Koori Magistrates’ Courts and two

Children’s Koori Courts for 10-17

year

olds,[19] now in

operation throughout the state. The locations of the courts were chosen after

consultation with Elders and Respected persons

of Indigenous communities where

there was a high incidence of Indigenous re-offenders, and also where adequate

support and rehabilitation

programs were already established.

Figure 2: Location of Koori Courts throughout Victoria

Based on the success of the pilot program, the County Koori Court opened in Morwell in country Victoria in November 2008.[20] More serious cases are heard in this court, which is Australia’s first sentencing court for Aboriginal offenders in a higher jurisdiction.

County Koori Court

The layout and seating in the County Koori Court

is similar to the Koori Magistrates’ Court, but with a Judge presiding. A

feature of this court is the beautiful elliptical table where all participants

are seated for the ‘Sentencing

Conversation’.[21]

This is not only a work of art, but an example of Koori communities working

together, as the 10,000 year old ancient red gum timber

was brought from Yorta

Yorta country in the Shepparton area and crafted with care in the Ganai-Kurnai

country for use in the County

Koori Court.

Where this Court differs from the Magistrates’ Koori Court is that matters before the court are heard in three stages. The first stage is the formal arraignment, where the defendant enters a formal guilty plea. The Koori Elders and Respected Persons are not present. The second stage is the ‘Sentencing Conversation’, similar to the informal hearings conducted in the Magistrates’ Koori Court. The third stage of the hearing is the sentence, usually conducted on a separate day after deliberation of all the facts by the Judge. Proceedings are formal, with the Judge and legal representatives returning to the courtroom in wig and gown, and the defendant hearing the verdict from the dock. The Elders and Respected Persons are seated at the back of the court, in order to show that the sentence is the decision of the Judge alone.

Observations and Discussion

The Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Report

2007-2008 was released by the State Government in February 2009, and highlights

both the difficulties

faced, and progress made so far, to address the imbalance

in life opportunities for Koories in Victoria.

At all hearings the researcher attended there appeared to be an awareness by legal professionals of any cultural and language difficulties, and the process enabled the Judicial Officer to address these difficulties, while dealing with the offence in the court system. Many underlying issues such as drug and alcohol dependence, the need for anger management, adequate housing, lack of education or employment, are now voiced in the Koori Courts which would not be the case in a mainstream court when the defendant is silent and only speaking through his or her lawyer. Some defendants find it too confronting to have to face their Elders and take responsibility for their actions, so choose to remain in the mainstream court system.

At a recent hearing, two Elders spoke about the shame a defendant had brought to her community, but another Elder sitting in the body of the court interrupted proceedings and spoke at length about how she knew the defendant’s family very well and how they were a respected family over several generations. She gave an insight into the defendant’s character and background that would only be available with personal knowledge, and the Judge thanked her for her contribution.

At another hearing, the Elders emphasized their horror at the offence, (assault with violence), and commented on the ‘mob behavior’, fuelled by alcohol. The Elder, Uncle ‘B’, shared his life story, saying that ‘it wasn’t easy growing up as a black fella coming from a settlement, but you’ve got to get out there and fight for respect’. He put his hand on his heart and talked to the defendant about having ‘pride’ and ‘heart’, but added ‘you’ve got to move on now. We’re proud of you caring for your son – make it worthwhile’. But there was a word of warning from Aunty ‘M’, ‘we are from the community - the grapevine is very strong – we’re watching, especially your Grandma who has battled so hard’.

The Court is adaptable to cultural needs. At one hearing at the County Koori Court, the hearing was about to proceed when it was found that Aboriginality had not yet been proven. The case could therefore not go ahead in the Koori Court, so a normal court had to be convened in the same courtroom, but with all the formalities including Judge and legal professionals in wigs and gowns and defendant in the dock.

Miscommunication in the Court is kept to a minimum by the use of plain English. Elders provide cultural knowledge, and each participant around the table is given the time to speak. On one occasion the grandmother and the mother of the defendant were sitting beside him, and although the mother was very shy, Grandma exercised her right to be heard at great length. The Magistrate heard her story patiently, clarified parts of the story with her, with the result that several underlying issues were revealed and attended to.

At most hearings attended, language accommodation appeared two-way, with the Judicial Officer directing proceedings but simplifying conversation to the defendant, thus decreasing the social distance. Repeated checking by the Judicial Officer that the defendant understood proceedings also meant that ‘gratuitous concurrence’ was not evident at the hearings attended by this researcher, however detailed analysis would be required to support this.

At one court sitting, the Elder fixed the defendant with a steely eye and said ‘look at me and show me respect’. This contradicts the claim that Aboriginal speakers cast their eyes down as a measure of respect. Mainstream magistrates and lawyers in the past have considered this a mark of uncooperative behaviour or guilt, however this appears more an arbitrary occurrence depending on the elder and/or the offender at that particular hearing.

Formality is dispensed with in all Magistrates’ Koori Courts, but only in Stage 2 of the County Koori Court. Stages 1 and 3 in this court are conducted in a formal manner. As this court is in a higher jurisdiction, there may be a need for the separation of the judiciary from the offender to emphasis the seriousness of the offence. An evaluation of the pilot program will reveal the success of this approach, and whether the exclusion of the Elders from two stages of the hearing affects the success of the program.

Koories are becoming more aware about the workings of the Koori Court. At first many were suspicious that it was ‘white fella law’, but now that they realize they have a voice, they see that ‘white justice’ and ‘black justice’ are one. A continuing theme running through the hearings is that attitudinal change is occurring, both within and outside the Criminal Justice System. Some Koories who come to the Court walk in to the hearing with a brash and cocky attitude, but after sitting opposite the Magistrate and being told by the Elders of their community that they bring shame to their culture and family, they often burst into tears or hang their heads (a jug of water in the middle of the table and a box of tissues exemplifies the emotion which often occurs in this court). This is where the Elders play a very important role in the administration of justice. They command authority and respect, and the offender responds to this. Often for the first time, the defendant can tell their story in their own way and in their own time.

Increased programs and workshops on Aboriginal Cultural and Language Awareness run by the Judicial College of Victoria have included discussion with members of Aboriginal communities. Activities such as ‘Building Bridges with Koori Elders’ build relationships and enhance dialogue between the judiciary and Indigenous Victorians.

Many young disadvantaged Koories do not have functional literacy or numeracy, and the government is working in partnership with Indigenous communities to correct this. Teachers, students, apprentices, are all encouraged to have a new culture of high expectation. In Victoria, a number of language reclamation projects are currently being carried out in partnership with linguists and Indigenous communities, with the aim of re-connecting Koories with their language and culture.

In his independent evaluation of two courts in the pilot program over the period 2002-2004, Harris found a ‘high level of support for the Koori Court model’, and that it was a ‘resounding success’.[22] The Australian Government echoed this, releasing a Productivity Commission Report on 2nd July 2009 on ‘Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage’, which listed the Koori Court and other alternative sentencing courts as ‘things that work’ in overcoming Indigenous disadvantage.[23]

Harris reported a reduction in the level of recidivism of Indigenous offenders over the period evaluated, of 12.5% at Shepparton and 15.5% at Broadmeadows, compared with 29.4% over the same period for all Victorian defendants. According to Fitzgerald, however, this claim was ill-founded, as it involved an inappropriate comparison group of more serious offenders.[24] Marchetti and Daly also queried Harris’ findings, noting inadequate follow-up periods and the counting of court files rather than defendants. [25] In spite of this lack of consensus, this report remains a comprehensive evaluation of the first years of the Koori Court Program, and many of Harris’ 19 recommendations have since been implemented.

In a recent day of hearings in the Koori Court, there were nine matters listed, including failure to comply with a Community Based Order, aggravated burglary, alcohol and drug related charges, and driving offences. For one defendant it was a first offence, another was on remand, and another already in a program dealing with drug and alcohol dependence and anger management. The range of offences and degree of seriousness differed to such an extent that it would be very difficult to quantify to gain a true picture.

Current statistics from Corrections Victoria identify that there is still a high percentage of Indigenous offenders in the Criminal Justice System. However this does not reflect the steady improvement in the lives of many defendants who have passed through the Koori Court in the past few years. There has been not only a decrease in the severity of the offences, but a change in the types of offences, and many offenders are now in rehabilitation programs or have returned to study or employment. This supports the view that any statistical analysis of recidivism rates should be measured in decades rather than years, in order to provide a more accurate picture of the outcome of alternative sentencing courts.

The aim of the Koori Court is to replace custodial sentences with Community Based Orders, with backup from support services which assist the offender to re-connect with family and community and get the offender back to work or study. Of course there are also some very serious offences heard in the Koori Court. Some offenders end up incarcerated after being given a number of opportunities to change.

Collaborative Approach to Justice

Innovative partnership and

support programs put in place by the Victorian Government together with the

Courts and Indigenous organizations

have increased markedly since the

introduction of the Koori Courts. These concentrate on helping Koories who

come in contact with

the Criminal Justice system, instead of merely punishing

the offence. The government has encouraged the development of Local

Indigenous

networks (LIN’s), and there are more than 170 community-run

organizations which provide support and services to Indigenous

communities.

Some programs emphasise education and training, while others are diversionary in nature, for example the Wulgunggo Ngalu Learning Place, a residential program at Yarram built on the site of the old Won Wron Prison, for young male adults placed on Community Based Orders (CBO’s). This is a long term solution to recidivism where they can learn a trade or land management, with cultural input, such as the making of boomerangs and digeridoos.

Other programs are a Credit/Bail Support (CBS) program for early intervention; a Court Integrated Services Program (CISP); youth mentoring programs; programs in partnership with the AFL to ‘close the gap’ in the area of employment for Koories; and a ‘Build Ya Life’ program for young Koories at risk of contact with the Criminal Justice System.

The National Apology to members of the Stolen Generations by the Prime Minister of Australia in February 2008 was well received, and an opportunity for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians to strengthen their relationship, recognize past injustices and move forward towards a better future. Major cultural or sporting events around Victoria now commence with an acknowledgement and respect paid to the Aboriginal culture and heritage, and Elders past and present.

Summary

This review has found that the level of awareness of

cultural and language differences in the Criminal Justice system has increased

in several areas and continues to be the focus in the Koori Court of Victoria.

Partnership and support programs have expanded and

encourage rehabilitation.

Judicial officers are increasingly taking part in ongoing education and training

workshops. Defendants

are now more aware of the need to take responsibility for

their actions and deal with the issues that caused the offence in the first

place, thus reducing re-offending; and the physical presence of the Elders,

sitting directly across from the defendant, brings an

awareness of Aboriginal

culture and language to the court process.

The Koori Court program is much more than a quick fix. All the disadvantages and underlying issues for Indigenous people such as health, housing, jobs, education, drug and alcohol dependence and anger management, must continue to be dealt with urgently. As Deputy Chief Magistrate, Jelena Popovic comments “we have made a promising start – it’s a beginning.”[26]

[1] This paper was presented to the 9th Biennial Conference of the International Association of Forensic Linguists on Language and Law, 6-9 July, 2009, Amsterdam.

[2] Eades, D,

Courtroom Talk and Neocolonial Control (2008), Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin

5.

[3] The 2006

Australian

Census.

[4]

Corrections Victoria 2001-2 –

2007-8.

[5] By way of

background, ‘Koori’ is a term in popular use for Indigenous

Australians in the south eastern states of

Australia.

[6]

Victorian Government Indigenous Affairs Report 2007/08, Department of Planning

and Community Development,

Melbourne.

[7] See

Eades, D, “A case of communicative clash: Aboriginal English and the legal

system” (1994), In J Gibbons (ed) Language and the Law, Longman

Group, Harlow 234-264; “Aboriginal English on trial: the case for Stuart

and Condren” (1995), In D Eades (ed)

Language in Evidence: Issues

Confronting Aboriginal and Multicultural Australia, University of New South

Wales Press, Sydney 147-174; “Legal recognition of cultural differences in

communication: The case

of Robyn Kina” (1996), 16 Language and

Communication 215-227; “I don’t think it’s an answer to

the question: Silencing Aboriginal witnesses in court” (2000), 29

Language in Society 161-195; “Telling and retelling your story in

court: Questions, assumptions and intercultural implications” (2007), 20

Criminal Justice 209; (2008) above at n1.

[8] Gibbons, J,

“Introduction: language and disadvantage before the law” (1994), In

J Gibbons (ed) Language and the Law, Longman Group, Harlow 195-198;

Forensic Linguistics: An Introduction to Language in the Justice System

(2003), Blackwell Publishing,

Melbourne.

[9] Walsh,

M, “Interactional styles in the courtroom: an example from northern

Australia” (1994), In J Gibbons (ed) Language and the Law, Longman

Group, Harlow 217-233; “Tainted evidence: literacy and traditional

knowledge in an Aboriginal land claim” (1995),

In D Eades (ed),

Language in Evidence: Issues Confronting Aboriginal and Multicultural

Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney 97-124.

[10] Cooke, M,

“Aboriginal evidence in the cross-cultural courtroom” (1995), In D

Eades (ed) Language in Evidence: Issues Confronting Aboriginal and

Multicultural Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney 55-96.

[11] Koch, H,

“Language and communication in Aboriginal land claim hearings”

(1991), In S. Romaine (ed), Language in Australia, Cambridge University

Press,

Melbourne.

[12]

Pauwels, et. al (eds), Cross-cultural communication in legal settings

(1992), Language and Society Centre, National Languages and Literacy Institute

of Australia, Monash

University.

[13]

This conversation strategy described by Liberman, and used by some Aboriginal

people in court, may cause problems in a legal context.

See Liberman, K,

“Ambiguity and gratuitous concurrence in intercultural

communication”, 3 Human Studies Vol 1

65-85.

[14] Message

Stick, ABC1, Sunday 3rd May 2009.

[15] Royal

Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody National Report, (1991), Australian

Government Publishing Service, Canberra.

[16] Briggs, D and

Auty, K, “Koori Court Victoria – Magistrates’ Court (Koori

Court) Act 2002”, Paper presented

at the Australian and New Zealand

Society of Criminology Conference, Sydney, October

2003.

[17] Popovic,

J, Problem Solving Courts – response by the Magistrates’ Court of

Victoria (2004), Magistrates’ Court, Melbourne.

[18] Established

under the Magistrates’ Court (Koori Court) Act

2002.

[19]

Established under the Children and Young Persons (Koori Court) Act

2004.

[20]

Established under the County Court Act Amendment (Koori Court)

2008.

[21] A term

coined by the inaugural Magistrate Dr. Kate Auty at the Shepparton Koori Court,

which describes very well the philosophy behind

the success of these courts, and

how they differ from a mainstream

court.

[22]

Harris, M, “A Sentencing Conversation: Evaluation of the Koori Courts

Pilot Program October 2002-October 2004”, (2004),

Department of Justice,

Melbourne.

[23] The

Australian Government Productivity Commission Report, “Overcoming

Indigenous Disadvantage”, 2nd July

2009.

[24]

Fitzgerald, J, “Does Circle Sentencing Reduce Aboriginal Offending?”

(2008) 115 Crime and Justice Bulletin: Contemporary Issues in Crime and

Justice 1.

[25]

Marchetti, E, and Daly, K “Indigenous Sentencing Courts: Towards a

Theoretical and Jurisprudential Model” [2007] SydLawRw 17; (2007), 29 Sydney Law Review

415.

[26] ‘Koori Court – a sentencing conversation’ - DVD, viewed 14/5/09 at Broadmeadows Koori Court. Produced by Department of Justice Indigenous Issues Unit, 2007.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UMonashLRS/2010/12.html