Monash University Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Monash University Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 14 October 2011

Dispute Boards: Is there a role for lawyers?

by

Brennan Ong & Paula Gerber

This article was first published in Construction Law International, Vol 5 No 4, December 2010, and is reproduced by kind permission of the International Bar Association, London, UK.

© International Bar Association 2010.

Introduction

At university, law students are required to study Civil Procedure, where they learn how to conduct litigation. There is also a multitude of resources available to educate lawyers about the role they can play in alternative/appropriate dispute resolution (ADR), and numerous scholarly articles have been written about the role and responsibilities of lawyers involved in mediation. It is clear that ADR is now widely accepted and embraced by construction lawyers as a normal and natural part of dispute resolution. In contrast, although Dispute Boards (DBs) (e.g. Dispute Review Boards and Dispute Adjudication Boards) have received some scholarly analysis in relation to the role they play in preventing and managing construction disputes, there are no guidelines or courses on the role that lawyers can play in relation to DBs, and only very limited publications about whether the legal profession should be involved in DBs, and if so in what capacity. This article seeks to fill this gap.

Kurt Dettman, of Constructive Dispute Resolutions in Massachusetts, USA, asserts that there are two roles that lawyers can play when it came to DBs, namely as a member of a DB or in presenting arguments at any hearings that might be conducted by a DB. However, the authors of this article suggest that there is scope for even greater involvement of the legal profession in DBs, to the benefit of both construction lawyers and the construction industry. In particular, the authors explore four roles that construction lawyers can play when it comes to DBs, namely:

(1) advising clients regarding the suitability of a project for a DB;

(2) drafting contractual arrangements relating to DBs;

(3) assisting clients with drafting their written submissions and preparing

their oral

presentations to a DB; and

(4) being a member of a DB.

What is a Dispute Board?

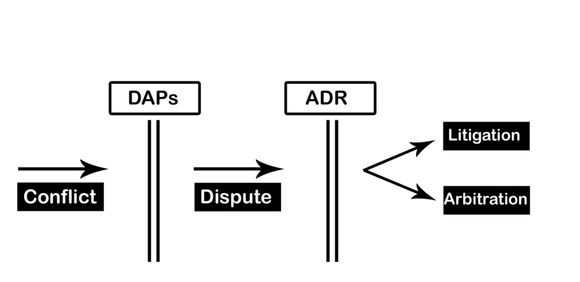

A DB is a panel of, generally, three independent and experienced persons who are jointly chosen and appointed by the contracting parties at the commencement of a project. The DB members become familiar with the construction project, and remain up-to-date with developments through regular site visits and meetings with the parties. The DB’s expertise and competence in the type of construction being performed enables them to understand potential complexities in the project, and their involvement with the parties and project enables them to help the parties prevent any conflicts that might arise, from escalating into disputes. Thus the DB plays a proactive role in the early identification and resolution of potential problems. As illustrated below, DBs fall within the arena of dispute avoidance processes (DAPs) that are designed to help parties proactively manage conflict and complete their project on-time, within budget and with no outstanding disputes. In contrast, ADR is reactive, being implemented only after parties are entrenched in a dispute, and generally not until after the project is complete.

Processes for interrupting the Conflict-Dispute-Litigation Continuum

In the event a conflict is not resolved, a DB can conduct a hearing which concludes with the DB providing either a recommendation or binding decision on how best to resolve the dispute. Whether a DB issues a recommendation or decision depends on the type of DB. Several models are in use around the world, including:

Thus, while the primary function of a DB is to assist parties to avoid disputes, it also acts as an efficient and effective contemporaneous dispute resolution system in the event that a dispute cannot be avoided.

The Dispute Resolution Board Foundation (DRBF) (www.drb.org) is a non-profit organisation based in Washington that aims to promote and assist owners and contractors with the DB process. The DRBF maintain a database cataloguing over 1,000 global DB projects, which includes comprehensive information for each project, such as the number of disputes heard, the number of disputes referred for a formal DB hearing, and the number of disputes that proceeded to further binding dispute resolution procedures. Notably, this database reveals that these projects have achieved a 98% success rate in achieving completion with no outstanding disputes. This is compelling evidence that DBs have a significant role to play in changing the litigious nature of the construction industry, and there is a strong argument for greater use of DBs, especially in countries like Australia, which has been slow to embrace the concept. On this note, the authors contend that greater support for and involvement with DBs by construction lawyers could lead to greater awareness and acceptance of DBs as an effective system for dispute avoidance and resolution. The following sections analyse four ways in which construction lawyers can become more actively involved with DBs.

1. Advising on the suitability of a DB

DBs have been around for more than three decades, and are enjoying increased usage on a variety of projects around the world. However, they are nevertheless a relatively new innovation, especially in jurisdictions outside of Asia and Africa (where a modified FIDIC contract (containing a DAB) is used on World Bank funded projects), and the United States. The idea of forming a DB at the commencement of a project to proactively manage conflicts and disputes is, unfortunately, an unknown concept to many principals and contractors. The aim of those promoting DBs should be to make the construction industry as familiar and comfortable with DAPs as they are with ADR.

Construction lawyers are often involved in the early stages of project planning, and regularly advise clients about appropriate project delivery methods. This presents them with an opportunity to provide early advice to their clients about the appropriateness of a DB. Thus, the first role that construction lawyers can play in relation to DBs is to advise clients whether there is a DAP model that is appropriate for their proposed project. This leads to the question, what type of projects are suitable for a DB?

Given the relative ‘newness’ of DBs, uncertainty still surrounds this question, but debate about when a DB should be used tends to centre around the question of costs. For example, the Australian experience suggests that DBs are only suitable for large-scale projects, with 17 of the 21 Australian projects that have used a DB being valued over $50 million. This indicates that within Australia, there may be a perception that the cost of a DB is disproportionate to the overall project costs, on projects worth less than $50 million. However, global experience suggests otherwise, and there is evidence of DBs being increasingly used on small/medium-scale projects, valued at less than $50 million. This is possible because DB procedures are designed to be flexible, and construction lawyers can assist parties to reduce the cost of a DB on small/medium scale projects, by adjusting the way the DB operates.

For example, although site visits are recommended by model provisions to be conducted quarterly, it is not uncommon for site visits to be reduced on smaller-scale projects. The costs of site visits can become significant especially if board members are sourced internationally, which not only requires paid travel time and accommodation expenses, but also often involve a week’s worth of daily fees for each board member. Another cost saving could be achieved by reducing the number of board members on a DB. This is consistent with the practice of many U.S state highway departments, such as the California Department of Transport and the Florida Department of Transport, who actively promote and implement varying types of DBs, ranging from a 1-person DB to a 5-person DB, to suit a wider variety of projects.

Construction lawyers who possess a thorough understanding of DBs have a valuable role to play in assessing the suitability of a particular project for a DB, taking into account not only the value of the project, but also other relevant considerations, such as the complexity and nature of the works, the parties track record regarding disputes, and the value the parties place on maintaining positive working relationships. Widespread use of DBs will only become a reality when parties to construction contracts are aware of the role they can play on a project, and are convinced of the commercial benefits of using a DAP. Lawyers are well placed to play a role in educating and informing their clients of the documented success of DBs on a wide variety of projects, and educating them about the benefits that can be derived from adopting a DB.

2. Drafting contract provisions for a DB

To establish a DB on a construction project, two documents are required, namely:

There is no need for lawyers to ‘re-invent the wheel’ when it comes to drafting these two contracts, as there are a number of model DB provisions available. For example, the DRBF publishes a Practices and Procedures Manual that includes draft specifications and tripartite agreements. Similarly, there are standard form contracts in the international arena that include DB clauses, including FIDIC which incorporates DABs, and ConsensusDocs in the United States which incorporates DRBs. In addition, the ICC, through its Dispute Board Rules, provides standard specifications for using DRBs, DABs and CDBs.

However, despite the increasing number of ‘off-the-shelf’ DB provisions that are now available, each project is unique and requires the tailoring of standard DB provisions to suit the particular parties and projects. Construction lawyers can assist clients to adapt the standard DB specifications and tripartite agreement to suit their particular project. Below are a couple of examples of changes to the standard provisions that parties might like to consider for their project:

DB selection criteria: None of the standard DB provisions require that any member of the DB has legal expertise. However, many construction disputes revolve around questions of contractual interpretation and application. In light of this, lawyers might want to consider discussing with their clients whether their project might benefit from a requirement in the DB specifications that one member of the DB must be a lawyer. For example, the Sydney Desalination Plant Project used a DRB and the contract required that the DRB chairman be a Senior Counsel from the NSW or Victorian Bar who had construction law and dispute resolution experience.

Powers of the DB: None of the standard form DB provisions include any limitations on the powers of a DB. However, there may be circumstances where it is appropriate that a DB not become involved in a dispute. Construction lawyers with in-depth knowledge and understanding of DBs can advise clients about whether any limitations or changes should be made to the DB’s jurisdiction, and draft provisions to give effect to this. For example, it may be appropriate to have some constraints on the monetary value of disputes that can be referred to the DB, e.g. only disputes involving more than $5,000 can be referred to a DB. Such a limitation can be a useful way of containing DB costs, by ensuring that the time of DB members is not wasted on trivial matters, which the parties are encouraged to resolve themselves. It would also be inappropriate for the DB to hear disputes involving allegations of fraud, and the DB specifications could also be amended to incorporate such a limitation on the DB’s powers.

Thus, a construction lawyer with expertise in DBs can assist in tailoring DB contract provisions to suit the parties and their project. Further, the fact that some jurisdictions, like Australia, do not offer embedded DAPs provisions in any standard form contracts, make it particularly important for lawyers to understand precisely how such standard forms should be modified so as to incorporate a DB, and which clauses will need to be deleted or amended as a result.

3. Assisting clients with preparing submissions and making presentations to a DB

The involvement of lawyers in DB hearings has been the subject of much debate, with some commentators arguing that lawyers are more of a hindrance than a help. This view stems from a fear that the construction lawyers will ‘hijack’ the DB process in much the same way that construction arbitration has been hijacked by lawyers, with the result that arbitration all too often fails to provide a genuine alternative to litigation. Nobody wants the same fate for DBs, and it is vital that any involvement of lawyers in DB hearings does not lead to the process becoming as adversarial as the litigation system it was designed to keep parties out of.

A DB hearing is not a judicial process, nor even a quasi-judicial process. Because of this, the rules of evidence are not observed, and cross-examination is expressly prohibited by the DRBF’s standard specifications. Similarly, FIDIC refers to the DAB as adopting an inquisitorial procedure, and that the examination and cross-examination of witnesses should be strictly controlled. However, like litigation and arbitration, the purpose of a DB hearing is to persuade a panel about how a dispute should be resolved. Carefully drafted written submissions and well-presented arguments will assist parties in convincing the DB of the merit of their position. Although there are published guides aimed at helping parties to prepare for a DB hearing, e.g. the DRBF’s Practices and Procedures Manual, construction lawyers well versed in DB processes will be able to maximise a party’s chances of achieving a favourable outcome from the DB. The authors’ are not advocating that lawyers ‘take over’ DB hearings, but rather, that they assist their clients, behind the scenes, with the necessary preparatory work, particularly if the dispute involves legal issues. Indeed, it is the view of the authors that it is inappropriate for lawyers to appear for parties at DB hearings, as this is likely to lead to greater formality and over legalisation of the process. An informal, practical approach to conflicts and disputes is at the heart of DBs and a key element of their success. Thus, lawyers should not be advocates at a DB hearing, but do have a role to play in assisting clients to prepare and present their arguments in a clear and logical manner.

4. Appointment as a Member of a DB

In his 1984 The State of Justice address to the American Bar Association, former Chief Justice Warren Burger observed:

The entire legal profession – lawyers, judges, law teachers – has become so mesmerized with the stimulation of courtroom contest that we tend to forget that we ought to be healers of conflict. Doctors, in spite of astronomical medical costs, still retain a high degree of public confidence because they are perceived as healers. Should lawyers not be healers? Healers not warriors? Healers, not procurers? Healers, not hired guns?

It is this perceived addiction to adversarial battles that has motivated some commentators to discourage the appointment of lawyers as members of a DB. These concerns are based on fears that lawyers may legalise the procedures to the detriment of the DB philosophy and process, which revolves around the contemporaneous resolution of construction disputes in a harmonious way that preserves a positive working relationship between the parties. As noted above, legalisation of the DB process is inconsistent with the goal of DBs, and risks increasing hostilities between disputing parties. However, the success of any DB is highly dependent on obtaining the right mix of DB members, who not only have knowledge and experience with the type of construction being undertaken, but also with the interpretation and application of construction contracts. With this in mind, appointing the right lawyer as a DB member – one who displays an avid interest in the resolution of disputes without recourse to the customary judicial processes, and who is supportive of the DB concept – could strengthen and enhance the capabilities of the DB, to the benefit of both the parties and the project.

Having a DB that includes a lawyer who is well equipped to resolve issues of contractual interpretation, and armoured with skills in negotiation and non-adversarial dispute resolution, will enable the board to assist the parties to avoid the escalation of conflict into disputes. Indeed, teaming a lawyer with other specialists capable of resolving the engineering and technical issues can ensure that the DB has a combined skill set that enables it to address the widest array of disputes. It is for this very reason that George Govlan QC, the chairman of the Sydney Desalination Plant project, observed in his 2010 article in the Australian Construction Law Newsletter, that:

The experience required of DRB members was experience in similar construction projects, interpretation of large scale project documentation and involvement in resolution of large construction disputes. The parties recognised the importance of DRB members having dispute resolution expertise in addition to technical and legal skills.

An additional benefit of having a lawyer as a DB member stems from the fact that the end product of a DB hearing is a written decision that contains either a non-binding recommendation (in the case of a DRB), or an interim binding decision (in the case of a DAB). In either scenario, it is preferable that the report be carefully drafted in a way that convinces the parties to accept the DB’s findings, and so avoid the dispute progressing to arbitration or litigation. A lawyer can also ensure that the recommendation or decision is soundly based on the contract and the law so that parties can be assured that the DB’s conclusions are a foretaste of the likely outcome of an arbitration or litigation, thereby increasing the likelihood that the DB’s report will be accepted.

Thus, in many ways, a DB report is a tool for settlement, and a lawyer’s perspective on how to achieve this could be invaluable. Lawyers are renowned for their persuasive abilities, and can play a useful role in ensuring that the DB expresses its opinions in ways that not only increase the likelihood of both parties accepting the DB’s findings, but also facilitates ongoing harmonious relations between the parties.

Conclusion

Although the reported success rates of DBs are encouraging, the process is not a panacea, and the benefits that can be derived from DBs are highly contingent on careful planning and implementation. Construction lawyers are well equipped to ensure that the necessary processes are in place, draft appropriate contractual arrangements for a DB, and assist with any presentations or submissions that may be made to a DB. While there are still some lawyers who are wedded to the courtroom battle, and who should not be allowed anywhere near a DB, they are, fortunately, a dying breed. Construction lawyers who wholeheartedly support the philosophy of DAPs are well placed to assist their clients to proactively avoid and manage conflicts, rather than reactively resolve disputes through the expensive and timely processes of litigation, arbitration or even ADR. Lawyers who embrace DBs have the chance to become genuine healers of conflict rather than instruments of war; a role that is all too often performed by litigators.

Paula Gerber is a Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Monash University, Australia where she teaches Construction Law.

Brennan Ong is a Research Assistant at the Monash University Law School, Australia.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UMonashLRS/2010/7.html