University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Faculty of Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 10 October 2013

Financial Innovation in East Asia

Ross P. Buckley, University of New South Wales

Douglas W. Arner, University of Hong Kong

Michael Panton, University of Hong Kong

Citation

This paper is to be published in Seattle University Law Review, forthcoming. This paper may also be referenced as [2013] UNSWLRS 69.

Abstract

Finance is important for development. However,

the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998 and the global financial crisis of 2008

highlighted

the serious risks associated with financial liberalisation and

excessive innovation. East Asia’s strong focus on economic growth

has

necessitated a careful balancing of the benefits of financial liberalisation and

innovation against the very real risks inherent

in financial sector development.

This paper examines this issue, focusing on the role of regulation and legal and

institutional infrastructure

in both supporting financial development and

limiting the risk of financial crises. The paper then addresses a series of

issues with

particular developmental significance in the region: trade finance,

mortgage markets, SME finance, non-bank finance, and mobile financial

services.

I. Introduction

Financial innovation has been defined as both the

“technological advances which facilitate access to information, trading

and

means of payment, and ... the emergence of new financial instruments and

services, new forms of organisation and more developed and

complete financial

markets.”[1] While financial

innovation has traditionally been associated with economic growth and

development, the financial crises of the past

decade have revealed the

significant risks posed by innovations in the absence of adequate regulation. It

is now clear that financial

regulation must balance risk with innovation in

order to maintain financial stability and support economic growth. This

pragmatic

approach to financial regulation was adopted in

East Asia following the Asian financial crisis, and is arguably one of the

greatest financial innovations

of the past decade. It is essential that such an

approach be maintained in East Asia and the West should be encouraged to look

to,

and learn from, the successes in East Asia as it attempts to recover from

the global and European financial crises.

In the two decades prior to

2007, financial innovation was viewed in most countries as a desirable objective

worthy of policy support.

Institutional development was particularly encouraged;

specifically law reform, deregulation, and financial liberalisation. During

this

period, finance in Asia was generally viewed as suffering from a lack of

financial innovation, with repressed markets and underdeveloped

institutional

infrastructure, particularly in the realm of law and regulation.

Since 2007

and the onset of the global and Eurozone financial crises, the general view of

financial innovation has become much more

nuanced. Financial innovation is no

longer seen as universally desirable, particularly as many innovations of the

preceding decades

played a central role in the global financial crisis.

Financial systems that had previously been characterised as suffering from

excessive regulation and insufficient innovation, such as those of Canada and

Australia, performed far better during the crisis than

the highly innovative

financial systems in the United Kingdom and United States. Likewise, while the

financial systems of East Asia

had been viewed as insufficiently innovative,

they suffered relatively minor financial crises by comparison to the United

States

and Western Europe. As a result, views of financial innovation have

changed significantly in a short period of time.

This paper considers the

role of financial innovation in the past, present and future development of East

Asia. It begins with the

question of whether, in fact, East Asia can be

characterised historically as suffering from a lack of financial innovation.

While

East Asia has certainly been the source of many significant financial

innovations historically, it is most commonly seen as having

generally lacked

innovation in the period since the Second World War. We argue that this

characterisation is not entirely accurate

and that, in fact, East Asia has

continued to innovate in finance during this period. At the same time, perhaps

one of its most important

innovations has been an approach to finance that is

both cautious and focused primarily on supporting real economic activity,

particularly

in the wake of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998. This

pragmatic approach to financial innovation is largely responsible for

the

region’s resilience during the global financial crises.

From this

background, we consider financial innovation in East Asia’s future

development. Given that finance in the individual

economies of the region tends

to be dominated by large domestic banks which often focus their lending on large

firms, there is a

clear need for alternative sources of funding. This is the

area where financial innovation matters most for East Asia going forward.

Specifically, we identify five areas where East Asia needs to focus on

supporting innovation in order to maintain financial stability

and also support

economic growth and development: mortgage markets, trade finance, SME finance,

non-bank finance, and mobile financial

services. In each of these areas,

innovation based on local circumstances and needs is vital to support financial

stability and growth

across the region.

II. Financial Innovation in East Asia’s Development

Financial market professionals, and various

scholars, have frequently characterized finance in East Asia as being

insufficiently

innovative.[2] Under

this characterisation, East Asia has been a “taker” of financial

innovations from the West, usually receiving new

financial strategies and

techniques third-hand after their development in the United States and

successful spread to Western Europe.

Only at that point have Western financial

institutions and professionals then exported successful techniques to East Asia

in search

of new opportunities for profit. That characterization, however, is

historically inaccurate.

A. Financial Innovation in Asia’s Early Development

The Asian economies, particularly prior to the

industrial revolution in Western Europe, were the source of some of the most

significant

historical financial innovations. Marine insurance and ship finance

came from the Phoenicians, as did, arguably, early forms of venture

capital and

corporations; agricultural futures and paper currency were derived from China;

group lending and insurance pools were

common across the region and likely

originated from China;[3] and bills of

exchange, hawala and covered bonds from the Islamic world and the Ottoman Empire

further exemplify financial innovation

originating from

Asia.[4] As such, it is clearly

incorrect to suggest that Asia, including East Asia, has always suffered from a

lack of financial innovation

and has always been a taker of financial

innovations from Western markets. In fact, many of these innovations, which

originated in

Asia, were central to the institutional framework that supported

and funded the industrial revolution in Western

Europe.[5]

Even in the second half

of the twentieth century, Asia has been the source of a number of significant

financial innovations. Three

examples warrant particular attention: the

developmental state, microfinance, and Islamic finance – all of which are

important

Asian financial innovations.

The model of the developmental state,

pioneered by Japan and exported across the region, comprises the repression of

finance to mobilise

financial resources to support export industries and thus

economic growth and development.[6]

There are very significant limitations to the model, particularly as economies

reach higher levels of development and fuller integration

with the global

economy and financial system. These limitations have been highlighted

dramatically by Japan’s two-decade financial

malaise and the Asian

financial crisis that commenced in 1997. Nevertheless, the model has been vital

to the region’s successful

development. Likewise, the centrality of

finance to the model is clearly an innovation and a very successful and

influential one,

albeit one with important limitations.

Microfinance emerged

from Bangladesh as an Asian innovation and has spread around the

world.[7] It is one of the most

influential developments in finance in the past thirty years. The focus

microfinance puts on lending small

amounts to the poor to support economic

activity and its use of a range of social techniques, such as group lending, to

ensure repayment

is an innovation clearly related to the actual conditions and

needs in the region. Likewise, the region, particularly Malaysia and

Pakistan,

has contributed greatly to innovations involving Islamic

finance[8], which have been exported

across Asia and also to Western

markets.[9]

In addition, other

areas of Asia-Pacific financial innovation include pensions, where Australia and

Singapore are world-leaders;[10]

stored value cards/e-money, where innovations in Hong Kong have spread around

the world;[11] and internet and

mobile banking and financial services, where developed East Asia leads the

world.[12]

While Asia has not

generated as much innovation in the past 70 years as North America and Western

Europe, the region has nonetheless

produced globally significant financial

innovations that have contributed to real economic growth and development. It

is thus clearly

incorrect to characterise finance in Asia as lacking in

innovation.

B. The Limits of Financial Innovation

In an era of globalisation and highly interdependent

markets, finance matters. From the most advanced leading economies to emerging

and developing nations, finance is viewed as a vehicle for development and

economic stability. Supported by a growing body of literature,

a consensus

exists that a well-functioning financial sector is a primary driver of growth.

At the same time, finance – as emphatically demonstrated by the Asian,

global and Eurozone financial crises – is not without

its risks. These

crises have raised important questions about the limits of financial innovation

and development for economic growth

and development. Economic researchers,

Jeanneney and Kpodar, argue that “financial development helps reduce

poverty indirectly

by stimulating growth and directly by facilitating

transactions and allowing the poor to benefit from financial services (primarily

savings products) that increase their income ... and enhance their ability to

undertake profitable ...

activities.”[13] They

conclude, however, that during some stages financial development may

“demonstrably undermine poverty reduction because

the poor are generally

more vulnerable than the rich to unstable and malfunctioning financial

institutions.”[14] Thus,

increases in financial development and activity, and moves to more open markets

may, in some countries, increase the disparity

between the rich and the poor and

positively harm the poor.[15]

While finance is important in the process of industrialisation, an

unbridled financial sector does not necessarily lead to continuing

economic

growth and prosperity. In Paul Volcker’s words, “I wish that

somebody would give me some shred of neutral evidence

about the relationship

between financial innovation recently and the growth of the economy, just one

shred of information.”[16]

While in our view this position is too extreme, at the same time, post-crisis

research does indicate that, in finance, more is not

necessarily better. In an

important recent study, Cecchetti and Kharroubi examined the impact of finance

on growth and development

at the aggregate level and found that mature

sophisticated economies get to a point where greater volumes and sophistication

in banking,

credit and other financial tools become associated with lower

economic growth.[17] Cecchetti and

Kharroubi found that because the finance sector competes with other sectors for

scarce resources, rapid growth of finance

can have an adverse impact on

aggregate real growth.[18]

Essentially, rapid growth of a financial sector can serve as a drag on an

economy and shift resource allocation and distribution

in sub-optimal

ways.[19]

Finance in the most

advanced nations today utilises increasingly sophisticated and complex financial

products, which are not always

transparent and are often difficult to source and

assess. Meanwhile, developing states continue their integration into the global

markets while being challenged by capacity and governance issues. This is the

context for our examination of the benefits of increased

financial activity and

its likely impact on long term economic development. This also highlights East

Asia’s most important

financial innovation since the Asian financial

crisis: a pragmatic and cautious approach to financial innovation and

development,

focusing not on encouraging innovation for innovation’s sake,

but rather seeking to support the needs of the real economy through

financial

stability and economic growth.

III. Financial Innovation in East Asia’s Future

Today’s financial innovations are largely a

by-product of financial liberalisation, which itself was a response to the

financial

repression of the 1970s and 1980s in many developing countries.

Financial repression included state ownership of financial institutions,

government control and distortion of interest rate pricing, and capital controls

to restrict asset transfers.[20]

Such measures came to be seen as questionable given their poor financial and

economic results, inefficient allocation of resources,

and high costs,

especially associated with the proliferation of non-performing loans (NPLs).

Globalisation thus supported the move

to financial

liberalisation.[21]

Liberalisation involves the broad deregulation of financial

markets.[22] This process is

typically accompanied by easier and faster capital flows, decreased regulatory

scrutiny and an increase in the types

of financial instruments used or traded.

Liberalisation tends to lead to increasingly creative and innovative financial

products

that feed investors’ demands for higher

yields.[23] In the wake of the

increasing frequency of cross-border financial crises over the past four

decades, questions have emerged concerning

the relationships between

liberalisation, economic development, and risk. In moving away from financial

repression, liberalisation

– and the rise of privatisation that is

associated with it – is often thought to be a significant driver of

economic

expansion and higher long-run

growth.[24]

While many assert

a positive correlation between financial liberalisation and growth, the

empirical literature is decidedly divided.

Critics have found that external

liberalisation is more prone to producing instability in developing countries,

and generates financial

fragility that can often have severe recessionary

consequences. [25] Further, economic

researchers Glick and Hutchinson found a tendency towards banking and currency

crises following financial

liberalisation.[26] Thus, while

financial liberalisation promotes growth more than does a repressed economy, it

also increases market uncertainty and

the chances of severely damaging

crises.

When a country uses financial liberalisation to promote economic

development, it must take measures to limit instability in markets

and the risk

of financial crises. In developing nations, premature liberalisation before a

strong prudential regulatory structure

is in place can lead to destabilised

markets and crises.[27] Without

adequate regulation and supervision, as economic researchers Arestis and Caner

have shown, financial institutions tend to

take excessive

risks.[28]

These are lessons

that East Asia learned very directly in the Asian financial crisis a decade

prior to the global and Eurozone financial

crises. In East Asia, the Asian

financial crisis triggered a rethinking of both the developmental state model

and the then-prevailing

model of financial liberalisation. The result was a

synthesis focusing on maintaining financial stability and supporting economic

growth. Since the Asian financial crisis, finance in the region has been treated

pragmatically rather than relying excessively upon

market-focused theoretical

approaches.[29] Arguably, this

approach to finance largely explains why the major financial centres in the

region (Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo) suffered

so much less from the global

financial crisis than their major Western competitors (London, New York,

Frankfurt, Zurich).

East Asia’s approach was a major innovation in

financial regulation and is even more remarkable as it was dramatically contrary

to the prevailing wisdom. It is an innovation that regulators and policymakers

from around the world have increasingly looked towards

in the wake of the global

and Eurozone financial crises.[30]

This is arguably East Asia’s most important financial innovation in the

past 15 years and it should be accorded a high profile.

Given the significant

Asian membership of the G20 and Financial Stability Board and the region’s

relative success in the area

of financial regulation over the past 15 years,

there are important opportunities for the region to lead global approaches to

financial

regulation.

East Asia’s financial systems span a wide

range of development levels, from world-class international financial centres to

primitive

financial systems. It is thus difficult to address concerns

regionally. Nonetheless, looking forward, East Asia should continue to

adopt its

pragmatic approach to financial innovation, seeking to balance financial

stability and economic growth with market enhancing

policies and institutional

reforms.

Identifying financial limitations across the region will help to

identify areas in which innovation should be encouraged. We have

identified

five areas that should be of central concern for financial stability and

economic growth: trade finance, mortgage markets,

SME finance, non-bank finance,

and mobile financial services.

IV. Trade finance

International trade enhances efficiency and

competitiveness within economies and promotes their economic

development.[31] Trade finance is

essential to support trade, and the region that finances more trade than any

other is East Asia.[32] Some 80-90

percent of global trade transactions are supported by some form of credit

financing.[33] Finance for

international trade transactions is important for leading nations, and

particularly critical for developing and emerging

markets, where both exporters

and importers may be severely constrained by limited working capital.

A. The global financial crisis: Impact on trade finance

The global financial crisis sparked a substantial

worldwide shortfall in trade finance in a global market estimated at US$10-12

trillion

a year.[34] The effects of

this contraction were markedly different in different

regions.[35] South Asia, Korea and

China were particularly affected, with China experiencing a double-digit decline

in the availability of trade

finance during

2008.[36] The G20 responded with its

“trade finance package” in April 2009, which ensured the

availability of US$250 billion to

support trade finance over a two-year

period.[37] The package provided a

much-needed boost, and financiers worldwide responded to the package by making

substantially more finance

available for trade.

Export credit agencies

(ECAs) increased credit insurance and risk mitigation capacity by creating

programs for short-term lending

of working capital and credit guarantees aimed

primarily at small and medium sized enterprises

(SMEs).[38] Within the region, the

leaders of 11 Asian ECAs formed the Asian Regional Cooperation Group (RCG) of

the Berne Union and supported

more than US$268 billion worth of international

trade and investment in 2008.[39]

Regional development banks (RDBs) and the International Finance Corporation

(IFC) responded by significantly increasing the capacity

of trade facilitation

programs.[40] For example, the Asian

Development Bank (ADB) increased the capacity of their program to US$1 billion,

from US$400 million.[41] Central

banks in nations with substantial foreign exchange reserves responded by making

portions of those reserves available to finance

trade.[42] Within East Asia, Korea

pledged US$10 billion of its foreign exchange reserve to supply foreign currency

to local banks and importers

through repurchase

agreements.[43] Indonesia acted

similarly.[44]

The G20 package

ended in 2011. Trade finance market conditions improved continuously over the

two-year period up to this time, with

falling prices and increasing volumes of

transactions, albeit with some volatility around an upward

trend.[45] However, recovery has not

been even across all countries and gaps in trade finance persist.

B. Europe’s withdrawal of trade finance to Asia

Efforts to address the Asian trade finance gap have

been hampered by the ongoing economic crisis in Europe. European banks that

traditionally

provided trade finance facilities in East Asia have severely

limited their extensions of credit so as to improve their capital

ratios.[46] Since 2008, the

proportion of international credit provided by Eurozone and Swiss banks to

emerging Asia-Pacific economies has fallen

from 38 per cent to 19 per cent of

the region’s trade credit.[47]

This retreat has led to a dramatic increase in trade finance prices in Asian

markets.[48] According to Barclays,

“when European banks started to deleverage due to the Euro crisis [in

2011], trade finance pricing in

Asian countries including India and China moved

from 100 basis points to 200 basis points in three

weeks.”[49]

The reduction

in trade finance by European banks has left a funding gap at a time of

increasing demand for trade finance in

Asia.[50] In 2011, a US$1 billion

trade contract between the US and China could not proceed due to the lack of

trade finance.[51] In 2012, Chinese

exports grew by 25 per cent, imports climbed by 28.8 per

cent,[52] and the demand for

trade finance products increased

correspondingly.[53]

Fortunately, Japanese banks and some international banks such as HSBC and

Standard Chartered have stepped in to cover much of the

trade finance gap left

by the European banks. In the past two years, Japanese banks have dramatically

increased their share of large-ticket,

regional trade finance volumes, growing

from 6 per cent in 2010 to an extraordinary 54 per cent in the first quarter of

2012.[54] As a result, Japan became

the largest provider of trade finance globally in 2012, with reported trade

finance volumes of US$16.8

billion.[55]

Despite Japanese

and other nations’ banks stepping in, there is still a trade finance

shortfall in East Asia today, which is

serious given the critical role finance

plays in facilitating trade. The shortfall particularly affects the region

because a higher

proportion of trade is financed in East Asia than other

regions: more than 80 per cent of trade letters of credit are issued in

Asia.[56]

As well as a simple

shortfall of finance, Asian companies have complained that the cost of trade

finance is rising, probably due

to the growing pricing power exerted by the few

banks in the region willing to extend trade

credit.[57] While the top 40

institutions represented 95 per cent of the Asian trade finance market in 2011,

only 20 remained in the market for

Asian trade finance in

2012.[58]

C. Basel III and its Impact on Trade Finance

Apart from the retreat of European banks, the

largest challenge on the horizon lies in the implementation of Basel III –

the

third Accord agreed upon by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

(BCBS) -- which aims to improve risk management and governance

within the global

banking sector. While Basel III aims to establish a level playing field across

borders, the regulation is based

on Western experiences and its implementation

will not have the same impact

worldwide.[59] Basel III’s

requirement of larger capital holdings against trade transactions could slow

trade financing in emerging and developing

economies in the Asian region by

substantially raising transaction costs and discouraging trade financing,

thereby exacerbating the

trade finance shortage in the

region.[60]

Most experts

expected that Basel III would considerably increase trade finance pricing

worldwide if implemented in its original

form.[61] After two years of intense

pressure from the banking industry, the BCBS modified the liquidity coverage

ratio (LCR) for trade finance

products in January 2013 and delayed its full

implementation until 2019.[62] The

decision to relax the LCR has been regarded by the industry as positive, however

the longer-term impact of Basel III is still

likely to increase the cost of

financing trade.[63]

D. Potential responses

While the governments and regional institutions in

East Asia have largely succeeded in coming together to ensure availability of

trade

finance, there are still significant steps that can be taken to enhance

the provision of this critical type of finance for the region.

These include

further adjustments to the Basel III rules, deepening cross-border cooperation,

creating a ring-fenced liquidity pool

for trade finance, encouraging

public-private partnerships and co-financing, as well as the establishment of a

regional trade finance

database.

Further adjustments to the Basel III rules

Trade finance rates of default and loss have

historically been very low, even during

crises.[64] In 2009, the

International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and ADB initiated a trade finance

default register to collect performance data

on trade finance

products.[65] The project’s

data supports the claim that trade finance is much less risky than other types

of credit.[66] Between 2008 and 2010

the ICC Trade Finance Register observed fewer than 3000 defaults in a full

dataset of 11.4 million

transactions.[67] The data collected

determined the probability of loss as just 0.02 per cent in a period of global

economic turmoil.[68]

The

proposed Basel III rules do not come close to reflecting this very low level of

risk involved in trade finance. At present, there

is no differentiation between

trade finance and other forms of financing in credit conversion factors (CCFs)

for calculating the

leverage

ratio.[69] The current rules require

banks to apply a CCF of 100 per cent for all off-balance sheet items when

calculating a leverage ratio.[70]

Under the first two Basel Accords, trade credit attracted a low risk weighting

of 20 per cent because of its low default rates and

because trade finance

facilities are typically secured against the goods or commodities being

financed.[71] The Basel

Committee’s introduction of a flat 100 per cent CCF to certain off-balance

sheet items in 2010 was an attempt to

reduce incentives for

“leveraging”.[72] This

included letters of credit and similar trade finance

facilities.[73] Subjecting trade

finance to a CCF of 100 per cent is excessive given that the objective of the

leverage ratio is to prevent the build-up

of excessive leverage in the banking

sector and yet, as trade finance is underpinned by the movement of goods and

services, it does

not lead to the sort of leveraging that may endanger real

economic activity[74] but actually

supports the real economy.

The leverage ratio in its current form does not

reflect market realities and will significantly limit banks’ ability to

provide

affordable financing to businesses in developing countries and SMEs in

developed countries.[75] In its

report Global Risks – Trade Finance 2011, the ICC identified

numerous ways the leverage ratio proposed by Basel III could adversely affect

global trade and growth.[76]

Examples include encouraging the use of high-risk financial products, increasing

the cost of trade and limiting banks’ ability

to provide affordable

financing to businesses in developing

countries.[77]

At present, Basel

III also uses a standard asset value correlation (AVC) for corporate banking,

imposing a treatment for trade finance

that does not reflect its short-term, low

risk nature.[78] The current rule

requires the AVC to be multiplied by 1.25 in respect of exposures to financial

institutions whose assets exceed

100 billion US dollars and to exposures to all

unregulated financial institutions, regardless of

size.[79] The increase in AVC

applies to all sources of credit risk

exposure.[80] The rule is based on

the assumption that such exposures present greater systemic risks or default

correlations than others.[81] This

assumption ignores the fact that trade finance rates of default are dramatically

lower than the rates of default in other banking

sectors.

While Basel III

subjects corporate banking to a blanket AVC, consumer banking is granted several

product specific default curves.[82]

Under Basel III, separate AVCs are applied to retail mortgages, credit cards and

other retail exposures.[83]

Corporate banking products should likewise be distinguished from one another to

accurately reflect their level of risk. Applying

a standard AVC is likely to

increase the cost of providing trade finance, and may prompt smaller banks to

pursue other, more profitable

areas of

banking.[84] This could particularly

affect emerging markets.

Recent changes to the LCR under Basel III came

about after sustained pressure from the trade finance

industry.[85] At present, making

further changes to the rules may be difficult for the Basel Committee given

public sentiment towards banks.[86]

Furthermore, the Basel Committee is faced with the challenge that concessions

for one type of financing may encourage others to make

such

claims.[87] Nevertheless,

statistical information demonstrates that trade finance is far less risky than

other forms of finance and provides

a strong case for the industry to continue

lobbying the Basel Committee to modify the Basel III

rules.[88] Without changes to the

leverage ratio and AVC, it is highly likely that the price of trade finance will

increase, with damaging consequences

for trade and growth globally, and

particularly in East Asia.

Deepening cross-border cooperation

Deepening regional cooperation on trade finance

would be beneficial to all

parties.[89] By pooling resources

and expertise, East Asia would be better equipped to tackle bottlenecks in trade

financing.[90] The cost of providing

trade finance would also likely

decrease.[91] Cooperation within the

region would reduce reliance on foreign finance, which tends to be heavily

procyclical and often

destabilising,[92] as is seen in the

current trade finance gap caused by the retreat of European banks from Asia.

In March 2012 the Export-Import banks of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India,

China and South Africa) agreed to extend credit facilities

to each other in

local currencies.[93] It is expected

this move will reduce the demand for fully convertible currencies for

transactions among the BRICS, which should help

to reduce transaction

costs.[94] The initiative will also

assist to shield the BRICS from the Eurozone crisis and boost trade despite the

slow growth of developed

country

markets.[95]

As the Eurozone

crisis continues, it is likely that European banks will continue to withdraw

credit from the region. Strengthening

the regional network of export-import

banks and development finance institutions within Asia, and entering into

agreements similar

to those of the BRICS to extend credit to each other in local

currencies, would greatly assist the region. Deepening cross-border

cooperation

within Asia will reduce the cost of trade finance within the region, tackle

current trade finance bottlenecks and help

to insulate Asian economies from the

crisis in Europe.

Despite the benefits that could be derived from regional

cooperation, previous initiatives to improve financial cooperation within

Asia

have not always succeeded. In 2010, Australia’s idea of establishing a

trade finance network within Asia was not supported

by other members of the East

Asia Summit.[96] Nonetheless, the

creation of a trade finance network within Asia is something that regional

countries should continue to pursue.

Its potential benefits to the region, given

the ongoing demand for trade credit in the region, would be substantial indeed.

Creating a ring-fenced liquidity pool for trade finance

Since the global financial crisis, banks have become

more risk averse and prefer to work with large, sound multinational

firms.[97] SMEs and new exporters

have been especially vulnerable to the tightening trade finance conditions as

they typically have a weaker

capital base and bargaining power in relation to

global buyers and banks.[98] Firms

in developing countries with underdeveloped financial systems and weak

contractual enforcement systems are particularly affected

by a lack of

affordable trade finance as they need it the

most.[99]

Establishing a small,

targeted liquidity pool run by international financial institutions would be

useful to assist smaller segments

of the market that are more vulnerable to the

contraction of trade credit.[100]

After the global financial crisis, much of the increased liquidity support

provided by central banks was used to ease money market

conditions and improve

liquidity ratios.[101] As a

result, trade transactions did not benefit greatly from the liquidity

support.[102] Creating a

ring-fenced liquidity pool for trade finance would ensure that adequate funds

remain available to assist trade by SMEs

and new exporters, even during times of

crises when banks may prefer to direct funds elsewhere.

For banks, the

downside to ring fencing is that liquidity is prevented from being used for

other purposes at times when the other

purposes might be more

pressing.[103] Large cross-border

banking groups benefit from the efficiency of holding liquidity centrally and

directing it to locations where

it is most

needed.[104] This process is more

cost-effective than ring fencing

liquidity.[105] Nonetheless, any

disadvantages of a ring-fenced liquidity pool for trade finance would be far

outweighed by the benefit of ensuring

that trade finance is still available for

SMEs and new exporters when economic crises occur and trade finance conditions

tighten.

The global financial architecture needs to reflect that the finance of

trade is probably the most important form of finance for the

real economy.

Encouraging co-finance between the various providers of trade finance, including public sector-backed institutions

The private sector provides the majority of trade

finance. In 2009, private banks accounted for about 80 per cent of all trade

finance.[106] Such reliance on

banks leaves trading firms vulnerable in times of crisis, as we have seen with

the recent drop in trade credit provided

to Asia by European

banks.[107] To reduce the impact

of crises on trade finance flows, public sector actors, such as ECAs and RDBs,

should share some of the private

sector

risk.[108] An example of a

successful private/public partnership was the introduction in 2009 of the Global

Trade Liquidity Program by the IFC,

which allowed for a 40-60 per cent

co-lending agreement between the IFC and commercial

banks.[109] The program allowed

banks to continue to support clients with trade finance, and gave the IFC the

ability to channel liquidity and

credit into markets to help revitalise trade

flows by leveraging the banks’ networks across emerging markets

globally.[110]

Mobilising

private and public-sector institutions to form a partnership during times of

crisis would ensure that institutions with

excess capacities had an opportunity

to meet the needs of those with insufficient

funds.[111] However, co-financing

between the two sectors need not only be limited in times of crisis. Longer-term

cooperation would help to

close the structural market gaps in our region and

reduce the impact of any future financial crises on the availability of trade

finance.[112]

Establishing a regional trade finance database to facilitate the collection and exchange of information

Filling information gaps between public and private

institutions is of great importance, particularly during times of economic

crisis.

While responding to the financial crisis that commenced in 2008, members

of the Bankers’ Association for Finance and Trade

complained that a series

of measures announced by ECAs and RDBs were hard to

track.[113] They also lacked

access to critical information, such as who was providing what finance, and

under what criteria.[114] Such

information gaps affect the ability of both the public and private sectors to

respond to trade finance challenges, particularly

in developing

countries.[115] It is thus crucial

that information is collected and shared among trade finance stakeholders within

the region.

The ICC Trade Register established by the ICC and ADB in 2009

was a significant step towards increasing trade finance information.

So far the

database has recorded over 15 million transactions worldwide, reflecting 70 per

cent of global transactions.[116]

It is currently the most comprehensive data available on trade and export

finance.[117] Nevertheless, the

register only records data provided from participating

banks.[118] While this includes

twenty-one of the most active banks in worldwide trade

finance,[119] gaps in data remain.

Within the region, much more information is needed as to how SMEs, in

particular, finance their trade and the

challenges they face.

While the

information provided by the ICC Trade Register is crucial for the development of

trade finance policy, the Register does

not provide stakeholders with up-to-date

information about the type and amount of trade finance being provided at the

present time.

In times of crisis, such information is needed to allow trade

finance institutions to respond rapidly.

In order to address gaps in trade

finance information, a regional database should be created that disseminates

relevant information

to both public and private institutions, such as the

development of programs by ECAs. Such a database should include all trade

finance

stakeholders within the Asian region, not just commercial banks. It is

important that the information gap between the public and

private sectors is

filled so that both sectors can respond quickly when shortfalls in trade finance

arise.

V. Mortgage Markets

Strong housing markets are often equated with strong

economic growth and development. Given the growing population and trend toward

urbanization in East Asia, a strong mortgage market is a critical underpinning

for local housing markets. Mortgage market development

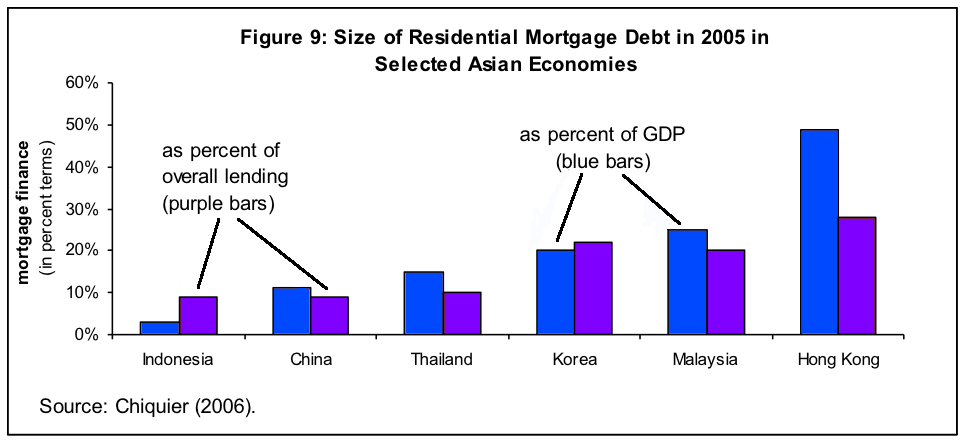

varies greatly across the

Asian region. Figure 9 shows the extent of mortgage market development in

selected Asian economies in 2006

(before the

crisis).[120] At this point in

time, Hong Kong’s mortgage markets (unsurprisingly in light of recent

events) had already developed the most

– standing at about 50 per cent of

GDP and 25 per cent of overall lending. At the other end of the spectrum,

mortgage markets

in Indonesia represented only about three per cent of GDP.

In virtually every developed economy, mortgage financing

supports housing markets. However, its effect varies in different domestic

financial sectors. China’s mortgage finance market, for example, eclipses

mortgage markets in the rest of

Asia.[121] Yet the Chinese

mortgage market remains but a fraction of the size of the US

market.[122] China’s housing

loans to GDP ratio stands at about 16 per cent, while US ratios peaked at about

80 per cent.[123] Government

supply of housing, and purchasing using pooled family resources, explains

China’s housing loans to GDP

ratio.[124]

In most developed

economies, strong housing markets underpin and correlate with robust economic

growth.[125] A strong housing

market also creates jobs.[126] In

Hong Kong, rapid housing sector development has not correlated with vigorous

growth in gross metropolitan

product.[127] In Singapore, on the

other hand, highly developed banking and equity markets, along with associated

legal and regulatory infrastructures,

have helped support sustained growth in

housing finance markets.[128]

Nevertheless, Singapore’s active mortgage market makes the city-state more

vulnerable to an overheated and overpriced market.

Japan possesses Asia’s

second largest mortgage market, and the most sophisticated mortgage financing

market.[129] With mortgage-to-GDP

ratios of approximately 40 per cent, the reliance of Japan’s financial

markets on mortgage-generated returns

cannot be

underestimated.[130] Such

dependence on mortgage-backed finance has led the Japanese economy to heights

and depths that are all too familiar.

In developing economies, the

relationship between mortgage finance and economic growth is murkier. Housing

prices in China continue

to rise at an alarming rate, in spite of the relatively

small size of the residential finance

market.[131] The Chinese

government and many investment analysts fear that the Chinese housing market may

resemble that in Japan in the

1970s.[132] However, Koyo Ozeki

points out that while Japan’s economy had matured by the 1980s,

China’s economy still possesses enormous

upside growth

potential.[133] China’s

young demographic profile will continue to drive the demand for new housing for

the foreseeable future.[134]

In Southeast Asia, the link between mortgage markets and economic growth

also remains relatively unclear. In India, the mortgage

finance market

represents about 8 per cent of GDP at US$104

billion.[135] India’s

mortgage industry remains at a nascent stage, and mortgage markets should grow

by 15 per cent annually, to achieve

a mortgage to GDP level of 13 per cent

within the next five years.[136]

The migration of professionals to major cities such as Mumbai and Bangalore

continues to support such growth. In a population averse

to debt, the average

mortgage loan repayment duration stands at about 13

years.[137] In Thailand, the

housing market is supported by a strong land registry system in place for more

than a century. The registration

system has evolved to being able to facilitate

land title transfers extremely quickly and efficiently (often in less than a

day),

and can easily be navigated without the need of a lawyer or a real estate

agent.[138] The home financing

market is very competitive, and there has been a recent lowering of interest

rates to help stimulate home ownership

for first time

buyers.[139]

Mortgage markets

in developing parts of Southeast Asia remain very small. In Indonesia, few

homebuyers take out mortgages, as purchasers

traditionally pay cash for their

residences.[140] Housing markets

appear to have flourished nevertheless, although lack of credit finance has

tended to keep home prices low. In Vietnam

and Cambodia, mortgage markets do not

yet play a significant role in supporting the housing

markets.[141] That is expected to

change, particularly in Vietnam as its economy continues to

evolve.[142]

Urban

migration has supported the need for, and development of, housing markets across

Asia. By 2030, 50-55 per cent of Asian people

are expected to reside in urban

regions.[143] Urbanisation will

continue to underpin the importance of the housing market and housing finance

for low and middle-income families.

As such, stable housing markets and mortgage

markets that finance home purchases remain vitally important.

A. The mixed reform of housing-related lending in Asia

The FSB Guidelines on mortgage underwriting serve

as a useful starting point in deciding whether various Asian countries have the

regulatory institutions in place to provide for pro-development outcomes and

manage the risks to the financial sector concomitant

with mortgage

finance.[144] These principles

include effective verification of income and other financial information,

reasonable debt service coverage, appropriate

loan-to-value ratios, effective

collateral management, prudent use of mortgage insurance, and effective

supervisory powers and tools.

Differences in regulations designed to

maintain appropriate loan-to-value ratios represent an important illustration of

the way that

financial regulation can balance development needs and financial

risks. Korea represents a positive example. The Financial Supervisory

Service

(FSS) targeted loan-to-value requirements for certain zoning areas in

particular, and applied different maximum levels to

various

zones.[145] Korean regulators then

changed these requirements counter-cyclically in response to changes in the

economy.[146] Korea’s

financial regulators co-ordinated with other government departments to ensure

that loan-to-value requirements served

the broader interests of regional

development and other policy objectives. As a result of such targeted policies,

housing price-to-income

ratios rose by only 7 per cent in Korea between 2000 and

2007.[147] In contrast, these

ratios rose more than 30 per cent in a range of OECD

countries.[148] Such an example

shows how dynamic mortgage regulations can strike a balance between development

and risk-management needs better

than a fixed policy-rule.

The Hong

Kong case shows how regulators may need to constantly adjust their mortgage

underwriting rules. In Hong Kong, housing prices

have risen 73 per cent over the

last three years,[149] yet the

city’s GDP grew only 1.8 per cent in

2012.[150] This has caused the

authorities to question the sustainability of current high property prices. In

response, the Hong Kong Monetary

Authority (HKMA) instituted its fifth round of

property market measures – including tightening the maximum debt servicing

limit

and capping home loan amounts in an effort to cool the overpriced

residential property market.[151]

Economists expect these measures to cut Hong Kong mortgage lending by 25 per

cent to HK$171.3 billion ($22.1 billion), which would

return the market to

levels approaching those in

2007.[152] Nonetheless, the market

remains

overpriced.[153]

Indian

policymaking shows the opposite extreme – how slow-moving and

contradictory regulation can limit development and increase

systemic

risk.[154] Urban housing has

failed to keep up with rapidly expanding demand for residential housing due to

failures in land and housing laws

and mortgage finance

laws.[155] Inappropriate formal

institutions governing the supply of land and real estate have resulted in high

transactions costs, fragmented

markets, tenuous approval processes for building,

and low mortgage

rates.[156]

Prudential

regulation in India has adjusted slowly to the rapidly evolving demand for

housing. First, changes to formal institutions

have allowed for broader changes

in the risks and returns to mortgage

finance.[157] Easier recovery

reduced risks for financial institutions and transferred some of those risks to

borrowers. Instead of the previous

quantitative restrictions placed on lending,

Indian mortgage finance institutions allowed lenders and borrowers to take

greater risks

– but price those risks

themselves.[158] Second, changes

in formal institutions have led to changes in informal institutions. The

“rules of the game” of mortgage

lending have clearly changed –

as informal norms have encouraged a large increase in mortgage lending. Mortgage

lending as

a percentage of GDP has increased four-fold from 2008 to

2012.[159] Third, Indian

institutions – despite their adaptation – have remained

“sticky.” In contrast to India’s

waves of mortgage-related

reform, regulators in jurisdictions like Hong Kong and Singapore reform their

regulations often, responding

to housing market needs and macroeconomic

developments.[160] Such Indian

stickiness (in academic terms, institutional rigidity) has kept mortgage finance

at too low a level to supply enough

housing to meet existing needs.

B. Financial crises and mortgage financing

Given the role of asset securitisation in the US

subprime crisis, a key area for housing finance reforms has been to ensure the

retention

of a degree of originator interest in securitised loans.

Securitisation enabled loan originators to quickly move loans from their

balance

sheets.[161] This created the

moral hazard of originators having no stake in the quality of the loans being

written.[162] Mandating the

retention of a permanent stake in a portion of the credit risk is likely to

improve the quality of loans

originated.[163]

An

important way forward for East Asia is the enhancement of institutional and

legal frameworks that will support the development

of a robust mortgage finance

market.[164] These institutional

frameworks include property rights, effective enforcement mechanisms, and

regulatory regimes.[165]

C. Moving forward

Policymakers in many Asian countries have adopted

policies that encourage mortgage finance of residential housing and other real

estate. Such credit creation deepens domestic financial markets, encourages

access to residential housing, and has multiplier effects

in the construction,

consumer goods and other industries. The potential of such reforms to underpin

further economic growth is large

in many of Asia’s middle-income

economies. However, as the US and EU experiences show, linkages between mortgage

finance and

derivative assets, like mortgage-based securities, can create

substantial systemic risk.

Most countries are pursuing mortgage finance

reform as part of a larger effort to strengthen their financial

markets.[166] In developing Asia,

market reforms have mostly been orientated toward strengthening core areas,

meeting international standards,

and increasing prudential regulatory capacity,

with less focus on reforming domestic mortgage finance markets. With housing

clearly

being a primary factor in domestic economic development, greater efforts

must be undertaken regionally to initiate reforms that protect

lenders and

borrowers and facilitate flows to finance transactions. Regulatory reform

efforts in the housing finance sector must

strike a balance between advancing

homeownership, which supports the domestic economy, and preventing an inflated

real estate bubble,

which harms consumers and remains a real risk in a number of

Asian countries.

Asian countries would do well to concentrate on following

the advice in the FSB Guidelines. At one extreme, the overzealous establishment

of income ceilings and checks on that income can restrict the flow of funds into

residential housing. At the other extreme, lax regulations

can encourage banks

to over-lend to classes of borrowers who cannot repay. East Asian nations are

generally seeking to strengthen

their legal, institutional and policy

foundations and this may well be the most useful contribution that can be made

to mortgage

finance reform. Perhaps the primary focus to promote mortgage

markets in our region should be upon the strength of their foundations,

much as

it is when one is building a home.

VI. SME Finance

Small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) are

key drivers of economic growth. Access to capital, however, poses challenges for

SMEs.

SMEs often need capital to get off the ground, and to achieve scale, and

thereby support the economy. Thus, it is important that

governments and

financial institutions find ways to increase access to financial capital for

SMEs.

Most of the region’s financial systems are characterised by a

small number of large domestic

banks.[167] These banks are often

quite effective at funding governments and large

corporations.[168] However, they

tend to be less effective in funding other forms of economic activity. At the

same time, while equity markets across

the region are likewise at varying levels

of development, as a general matter, equity markets are effective across the

more developed

economies in the region in supporting large

enterprises.[169] Finally, while

bond markets were underdeveloped at the time of the Asian financial crisis, now

bond markets are generally functional

across the more developed economies in the

region.[170] Bond markets

likewise, though, tend to be most effective in funding government and large

enterprises.[171] Thus, there is a

particular need in the region to focus on innovation in supporting provision of

finance other than to governments

and large firms, and particularly to

SMEs.

A. The challenge of SME finance

In many ways, SME finance is one of the more

significant aspects of financial development for supporting the real economy and

growth.[172] It has also been

among the more difficult to achieve. The important role SMEs play at the

domestic and international levels is well

documented.[173] At the same time,

SMEs face a variety of financial challenges in Asian

economies.[174] While factors such

as inflation and exchange rate fluctuations affect SMEs to a far greater extent

than their larger corporate counterparts,

the largest single challenge for an

SME in a developing economy is securing a bank as a funding source. In 2008 the

World Bank released

a report that showed few SMEs had a formal bank loan (only

about 20 per cent in China, 30 per cent in Russia and 55 per cent in

India).[175] The number of SMEs

within those countries that had not applied for loans at all was very high. For

instance, of SMEs without a bank

loan in China, 85 per cent had never applied

for one.[176] Likewise in India,

96 per cent of SMEs without a loan had never sought

one.[177] Accessing finance is

disproportionately more difficult for SMEs in developing countries. The IFC

found in 2011 that some 41 per cent

of SMEs in LDCs cited a lack of finance as a

major constraint on their growth and development, compared with 30 per cent in

middle-income

countries, and 15 per cent in the most advanced high-income

countries.[178]

The early

stages of SME growth and evolution are particularly critical. Businesses are the

most vulnerable financially during their

launch and early growth stages. During

the early stages of development, SMEs do not typically have formal funding

options and instead

rely heavily on self-funded, internal

sources.[179] This most often

includes savings of principals or less commonly, funding through the sale or

pledging of privately owned assets –

a concept that is rare in developing

economies. When self-funding has been exhausted, the availability of external

sources of funding

often becomes the factor limiting the firms’ growth and

productivity.[180]

The lack

of SME financing may stem from a number of factors, such as a lack of

legislation supporting credit and allowing security

interests to be created in

the types of collateral that SMEs typically have. Underdeveloped or

unenforceable property rights, or

weak banking and institutional structures, may

also further inhibit funding options.

SMEs in developing and emerging

economies face biases within the formal banking sector, where banks prefer to

limit their exposure

to risk by lending to large corporations and governments

rather than to small business entities, effectively squeezing SMEs out of

the

loan market.[181] When SMEs are

able to secure formal funding through a bank, they are often subjected to

inordinately high interest rates or overly

burdensome

terms.[182] Nevertheless, a recent

report by the IFC and McKinsey found that traditional banks are still the most

important source of formal

external financing for

SMEs.[183] This, in large part, is

because capital market access is very difficult for SMEs. This is the case even

in developed nations and

is even more so in developing ones where capital

markets are usually unsophisticated and

underdeveloped.[184]

The

financial climate became considerably more challenging for SMEs during the

recent global financial crisis, when SMEs had fewer

options than their larger,

more internationally integrated

counterparts.[185] Higher interest

rates and increased collateral requirements were but some of the tightened

credit conditions SMEs faced. The subsequent

recovery has been globally uneven

and sector sensitive in much of the world. For example, the requirements of

Basel III are likely

to impact SMEs more than some other

borrowers.[186] The extent of the

impact will depend on how a country and its institutions implement the Basel

reforms and international standards

pertaining to banking supervision and

capital requirements.[187] Various

Basel requirements could discourage formal banks from lending to the SME sector,

exacerbating the already precarious position

of SMEs in accessing formal bank

finance.[188] This will

significantly impact how SMEs perform and evolve.

B. Recommendations for increasing SME finance

The primary need of SMEs is for improved access to

finance from the bank and non-bank sectors. Commentators often focus on the need

to develop local capital markets, but the highly developed institutional

infrastructure needed for capital markets to function makes

their development a

major challenge. Furthermore, the high transaction costs associated with equity

and bond issuances means that

capital markets are not well adapted to meet the

financing needs of SMEs. Governments should thus focus on expanding access to

bank

and non-bank credit.

C. Developing Policies to Encourage SME Lending

Access to finance can be facilitated by expanding

bank services in rural areas, where a large number of SMEs are located. For

instance,

India initiated a program between 1977 and 1990 that mandated that

when a commercial bank wanted to open a branch in a primary location

where it

already had branches, it was required to open four branches in locations where

it had no branches.[189] This

program was based on the premise that commercial financial service providers

needed incentives to move into underserved areas.

A later evaluation found that

the “1:4 rule” was largely beneficial in providing increased banking

presence in rural

areas, and led to an increase in rural

credit.[190] While there were

problems related to subsidised interest rates and larger than normal loan

losses, the program was perceived as successful

in expanding access to finance

for SMEs and lowering the rate of poverty in the areas under

study.[191] Expanding the physical

presence of formal banks has generally been found to increase the use of banking

services by the formerly

unbanked.[192]

Improving

the secured transaction regime can significantly enhance SME finance options by

reducing the risk for

lenders.[193] SMEs typically do

not have the types of assets that most readily serve as adequate collateral

– immovable assets. To help facilitate

SME growth, a secured transaction

regime that can accommodate a broader range of assets is

required.[194] Expanding the range

of acceptable collateral has been correlated with enhanced economic growth and

stability.[195]

SMEs’

access to finance can also be greatly increased through the expansion and

utilisation of leasing and factoring (the discount

purchasing of account

receivables).[196] Factoring

depends on the financial condition of the obligor, not the SME. It generates

credit from the SME’s normal business

operations rather than from the

credit worthiness of the SME. Reverse factoring is particularly well suited

where contract law is

weak and credit information is unavailable or

inaccurate.[197] Leasing is also

highly advantageous to SMEs in that it secures credit by giving the financier

ownership of the leased equipment.

While various types of leasing and factoring

strategies are employed in advanced nations, they are still greatly

underutilised in

developing

economies.[198] This is due

primarily to weaker legal and regulatory regimes in developing

countries.[199] SMEs in the

developing world will thus benefit greatly from programs that strengthen their

nation’s legal and regulatory regimes,

and introduce effective secured

transaction regimes.

Finally, there is a bias within the traditional

banking sector that makes it more difficult for SMEs to secure

loans.[200] The banking industry

often perceives SMEs to be unstable, particularly in developing

economies.[201] This perception

can be exacerbated by a lack of sound financial information about the loan

applicant and by the fact that small transactions

are generally more expensive

to service for banking

institutions.[202] For SMEs to

flourish, a change in how they are perceived by the banking industry is

required. The state may need to incentivise lenders

(as the Indian government

did in the above example) to encourage them to offer their financial services to

a wider market. SMEs can,

with assistance, become valuable bank customers.

D. Allowing SMEs Access to Public Trading Markets

Another way to increase SME access to finance is by

giving them access to capital markets. An important first step towards improving

SMEs’ access to capital markets would be decreasing the fees associated

with going public. Simplified listing and disclosure

requirements for SMEs would

also allow for increased participation.

To expand access to finance for

SMEs, some jurisdictions have created SME stock exchanges or separate trading

platforms that cater

to the specific needs of

SMEs.[203] These dedicated stock

exchanges, or “junior markets,” have significantly less stringent

eligibility requirements and

considerably lower costs during the IPO

underwriting process.[204] The

success of these initiatives overall has been mixed. The performance of these

markets in developing economies, for example, has

not been strong, with many

offerings in lower-income countries being unable to attract financial

support.[205] In many of these

economies the general population does not have the capital to support IPOs.

Institutional buyers within these same

environments are unlikely to be

participants, as very few SMEs will meet their investment grade criteria. Thus,

few SMEs succeed

in capital market

raisings.[206]

The results of

such initiatives in middle-income and high-income countries have been better.

MESDAQ in Malaysia, London’s Alternative

Investment Market (AIM), and the

MOTHERS market in Japan, have been consistently successful in bringing small cap

SMEs to market.[207] Such SME

exchanges tend to succeed if (1) there is a sufficiently sophisticated primary

market from which the SME market may draw

expertise, and (2) the general market

has a track record of supporting IPOs, thus suggesting investors who are

qualified and economically

able to support SME

fundraising.[208] These factors

remain a major challenge in developing economies.

Access to finance is

perhaps the largest single barrier to SME

growth.[209] While there are many

other hurdles SMEs face, most challenges revolve around, and come back to,

resolving the dilemma of financing.

Government intervention, regulatory policy,

and improvements in the legal and financial infrastructure are all needed to

foster an

environment that promotes financing options for SMEs.

VII. Non-bank finance

As noted in the previous section, non-bank

finance provides a very important alternative to bank financing in supporting

East Asia’s

future development, particularly in the context of the

limitations of existing banking systems. At the same time, the supply of credit

by non-bank financial institutions is an area where Asian financial regulators

will need to exercise vigilance. They will need to

ensure that the positive

impacts of their regulation exceed the risks of weakening the domestic financial

sector.

A. Growth and Development of Non-Bank Finance in East Asia

Global non-bank finance, often referred to as shadow

banking, grew rapidly before the latest financial

crisis.[210] Rising from US$26

trillion in 2002 to US$62 trillion in 2007, the value of transactions conducted

in the shadow banking sector represented

about 90 per cent of global GDP by

2007.[211] The global value of

transactions conducted by non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) declined

slightly with the onset of the global

financial crisis in 2008 but increased

subsequently to reach US$67 trillion in 2011 (or about 110 per cent of GDP in

the countries

monitored by the

FSB).[212] Shadow banking

transactions represent about half of the value of assets in the banking sectors

of the countries providing information

to the FSB

exercise.[213]

The amount of

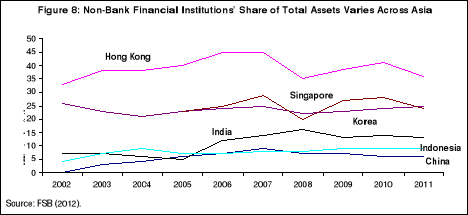

finance NBFIs provide differs markedly across Asian countries. Figure 8 shows

NBFI assets as a share of total financial

assets in six Asian

countries.[214] In Hong Kong,

Singapore and Korea, NBFIs play an important role in intermediating the flow of

investment and savings. NBFIs in Indonesia

and China play a small role, with

their share of total assets remaining below 10 per cent. Indian NBFIs have

increased the proportion

of assets they manage from about 7 per cent in 2002 to

a high of about 15 per cent in

2008.[215]

Non-bank finance appears to have played an important role in promoting

growth in high growth jurisdictions such as Hong Kong, Singapore

and

Korea.[216] Other Asian

countries’ NBFI assets represent a relatively negligible share of GDP.

B. Opportunities and Risks Posed by Shadow Banking

The growth of NBFI transactions provides

opportunities for Asian countries’ economic development. Shadow

banking has often provided finance that traditional banking institutions are

unable or unwilling to provide.

Many new business ventures have high levels of

risk which banks in many Asian countries have often not felt comfortable

servicing.[217] Shadow banking may

fill this need,[218] and may free

up resources – by providing credit extended on a wider range of

collateral.

On the other hand, the risks posed by shadow banking

arrangements are plentiful.[219]

There are many risks related to the supply of funds to NBFIs. First,

depositors may suddenly withdraw their funds. Second, margins may be lower

because NBFIs will need to pay higher

interest to compensate savers for the

risks of placing funds with these under-regulated financial intermediaries.

Third, they may

face certain types of counterparty and other risks on assets

placed with regulated financial institutions, as they may not have the

resources

to recover funds on demand. As such, NBFIs may be the first to liquidate assets

at a discount during periods of economic

shocks – further depressing asset

prices. Fourth, regulatory changes may affect the supply of funds from

traditional banks

to NBFIs. Regulators across Asia will apply their own

interpretation of the rules promulgated by institutions like the FSB about

shadow banking in upcoming years. Many of their responses may tend to restrict

bank lending to NBFIs (and lending by NBFIs themselves).

Such regulatory risk

can cause a sudden decrease in liquidity in the shadow banking sector.

Lending by NBFIs may also increase systemic risk in several ways. First, it

may push up asset prices throughout the economy –

such as in real estate,

where prices often depend on the supply of available funds. Second, NBFI lending

may lead to widespread maturity

duration and other mismatches, as NBFI managers

may not have the expertise to match the duration of funds received and funds

lent.

This is especially likely in developing parts of Southeast Asia. Third,

macroeconomic changes may cause large classes of NBFI borrowers

to disappear.

Tightening credit causes interest rates to rise across all types of lending.

NBFIs charge higher interest rates, partly

to cover their own cost of capital

and partly to price in the extra risks of their borrowers. Higher interest rates

often correspond

to highly elastic demand for funds.

C. Developing Innovative Policy and Regulation Around Shadow Banking

Regulators need to develop regulations that

anticipate the aforementioned risks and help mitigate their economic effects.

However,

regulators in many under-developed Asian financial markets have not

done so appropriately. India, Indonesia and Japan provide examples

of

regulations that have sought to respond (with greater or lesser success) to

these benefits and risks.

In India, regulators have started to amend

highly restrictive regulations with a view toward developing a range of credit

markets,

both formal and

shadow.[220] However, many of the

recent amendments do not demonstrate a clear consideration of the risks seeking

to be mitigated. In Indonesia,

piecemeal law-making has scattered laws

regulating NBFIs across a range of legislative and regulatory instruments. Lack

of a clear

focus on the potential risks and benefits has resulted in an abstract

Action Plan aimed at consolidating policy across the NBFI

sector.[221] As a counter-example,

Japanese regulation of NBFIs focuses on explicit outcomes rather than specific

measures. This focus has led

to the development of a vibrant NBFI sector. Such

an approach also reflects the principles the FSB has recently promulgated in

relation

to regulating shadow banking

markets.[222]

Japan’s

regulatory treatment of the capitalisation of these NBFIs shows how Indian

regulators could focus more sharply on the

gains and losses they seek to manage.

Indian regulators have sought to increase capitalisation requirements of NBFIs

for several

years. Currently Indian legislation requires NBFIs to have a

capitalisation of at least 2.5 million

rupees.[223] Recent

recommendations aim (under Section 45NC) to exempt all non-deposit taking NBFIs

from registration requirements if their individual

asset sizes fall below 500

million rupees.[224] Such a focus

on line-in-the-sand capitalisation floors ignores the risk Indian regulators

should target: the risk of default. As

such risk depends on the type of lending,

a more flexible approach should be adopted.

Recent proposals in India aim

at taking a regulatory approach focused on balancing risks and returns. Previous

regulation focused

on minimum capitalisation in order to obtain a registration

certificate. Section 45-IA(4)(d) of the Reserve Bank of India Act (1934)

requires the Indian central bank (the RBI) to review an applicant’s

capital structure before granting

registration.[225] The RBI may

impose certain discretionary requirements with regard to capitalisation and

assets under management before registering

an applicant (or providing an

exemption to registration under section 45NC of the Act). Demonstrating a firm

grip on the underlying