University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

ANDREW D MITCHELL[*] & TANIA VOON[**]

It is in the public interest to have an efficient and effective military justice system. Just as importantly, it is in the interest of all servicemen and women to have an effective and fair military justice system. Currently they do not.[1]

In the last year, two bodies have come to highly significant but apparently contradictory conclusions about Australia’s military justice system. Both have the potential to shape military justice in this country for years to come. In September 2004, the High Court made its first major decision in ten years on the constitutionality of military service tribunals. The Court decided, by a 4:3 majority, that a General Court Martial not constituted as a Chapter III court had jurisdiction to hear a charge of rape by an Australian soldier in Thailand while on leave from service in Malaysia. If anything, the majority decision reflected greater confidence in the existing military justice system than the previous decisions by the High Court in the late 1980s and 1990s, when composed of judges all but one of whom have since retired from the Court. Yet a few months ago, the Senate’s Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee (‘Senate Committee’) released a report calling for wholesale reform of Australia’s military justice system. If implemented, the recommended changes would be as significant as the establishment of a wholly Australian law of military discipline by the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982 (Cth) (‘DFDA’). In this article, we examine from a legal perspective how the current approach to offences allegedly committed by defence force members could be modified to enhance fairness and legitimacy, without losing sight of the objectives and constraints of military operations. We begin by providing an overview of legal and practical features of the current system of military justice under the DFDA. We then assess the constitutional validity of military service tribunals under the DFDA, recalling not only the requirements set out in the Australian Constitution but also the rationale for these requirements as relevant to military service tribunals. We pay particular attention to the High Court’s most recent pronouncements on this issue, in Re Colonel Aird; Ex parte Alpert (‘Re Aird’).[2] Our analysis leads to a new framework for determining which offences a service tribunal that is not a Chapter III court should be entitled to try. We then review and evaluate the recommendations of the Senate Committee regarding military discipline in its report on The effectiveness of Australia’s military justice system (‘Senate Report’),[3] pointing out areas of correlation with our own proposed framework. Our analysis demonstrates how Re Aird may be reconciled with the Senate Report and how the Constitution ensures both justice and effectiveness in the Australian Defence Force (‘ADF’).

In this section, we briefly set out structure of the ADF before considering the disciplinary aspects of the system of military justice established under the DFDA. An understanding of the nature of service tribunals under this system, in particular, is necessary to evaluate their constitutional implications and the reforms recommended by the Senate Committee.

The ADF was established by the Defence Act 1903 (Cth). The general control and administration of the ADF resides with the Minister for Defence (‘Minister’).[4] The Chief of the Defence Force (‘CDF’), appointed by the Governor-General, exercises the command of the ADF ‘subject to and in accordance with any directions of the Minister’.[5] Under the CDF, the Service Chiefs[6] (who are also appointed by the Governor-General) command their respective arms of the ADF.[7] The CDF and Secretary of the Department of Defence jointly share powers regarding the administration of the ADF, in accordance with any directions of the Minister.[8]

The Australian military justice system is designed to support this command and organisational structure. All ADF members are subject to this system. The most recent annual Defence Report stated that ADF total strength was 72,522 at 30 June 2004, comprising 52,034 permanent and 20,488 reserve members.[9] The military justice system has two main elements: a discipline system (which provides for the investigation and prosecution of disciplinary and criminal offences under the DFDA) and an administrative system (which aims to improve ADF processes such as complaint-handling). Our discussion is limited to the discipline system.

Offences under the DFDA can be grouped into three categories. First are offences peculiar to the defence forces, such as endangering morale,[10] absence without leave,[11] and disobedience of a command.[12] Second are offences that are similar or identical to ordinary civil offences (except that they relate only to service equipment or personnel or have an extraterritorial application), such as destruction, damage to or unlawful possession of service property[13] and dealing in narcotic goods.[14] Third are offences imported directly from the general civilian criminal law, under s 61 of the DFDA. Importantly, none of these offences is subject to a territorial limitation; under s 9, they apply to ADF members who are outside Australia.[15] In this regard, General Cosgrove stated in a submission to the Senate Committee:

The importation of a range of civilian criminal offences as disciplinary offences is of particular utility and importance when forces are deployed overseas, where ADF members may otherwise either not be subject to any criminal law or to host country law — neither of which may be desirable.[16]

The DFDA provides for punishments ranging from ‘imprisonment for life’ to ‘reprimand’, including a number of punishments that are unique to the military, such as ‘stoppage of leave’ or ‘extra drill’.[17]

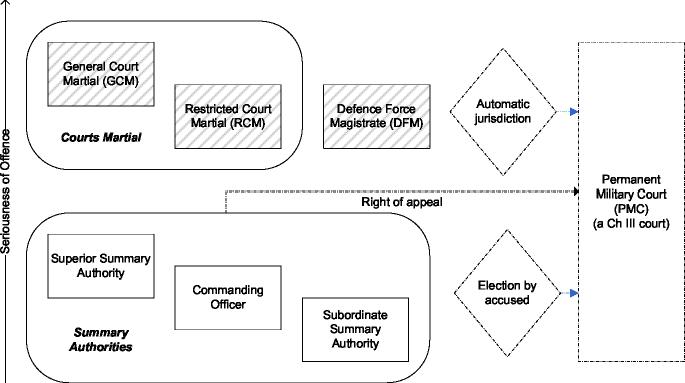

The DFDA creates tribunals to try ADF members charged with committing offences under the DFDA. Section 3 of the DFDA defines such a ‘service tribunal’ as ‘a court martial, a Defence Force magistrate or a summary authority’. Serious offences are generally dealt with by courts martial or Defence Force magistrates. We consider these three types of service tribunals in turn, before examining the use of ‘discipline officers’ in certain other situations. Figure 1 below indicates the frequency with which charges are heard by the different types of service tribunals and discipline officers.

A court martial has ‘jurisdiction to try any charge against any person’, subject to certain exceptions.[18] A convening authority appoints the members of a court martial[19] and a judge advocate (who has been enrolled as a legal practitioner for not less than 5 years) to assist the court martial with legal matters.[20] Members of a court martial must be officers and must hold a rank higher than the accused.[21] The DFDA provides for two levels of court martial: General Court Martial (‘GCM’) and Restricted Court Martial (‘RCM’). Procedurally, these courts martial operate in the same manner. Their distinguishing features are: the rank of the president of the court martial; the number of other members;[22] and the powers of punishment.[23]

Defence Force magistrates (‘DFMs’) handle the overwhelming majority of serious offences.[24] They are legal practitioners appointed by the Judge Advocate General of the ADF (‘JAG’), who sit alone when hearing cases.[25] They have the same jurisdiction and powers as RCMs,[26] but they may deal with matters less formally than courts martial. In addition, a DFM ‘gives reasons both on the determination of guilt or innocence and on sentence; courts martial do not give reasons on either’.[27]

A summary authority (being a superior summary authority, a commanding officer, or a subordinate summary authority) normally hears less serious offences. The key difference between superior summary authorities and commanding officers is the rank of the members they may try. Both have jurisdiction for all but the most serious service offences.[28] A superior summary authority is an officer (normally a senior officer) appointed by the CDF or a Service Chief.[29] Commanding officers may appoint subordinate summary authorities[30] ‘to assist them in the enforcement of discipline within their command’.[31] The jurisdiction and powers of punishment of subordinate summary authorities are substantially more limited than those of superior summary authorities and commanding officers.

Finally, the DFDA establishes special procedures relating to certain minor charges, termed the Discipline Officer Scheme.[32] Under this scheme, which commenced in 1995,[33] a discipline officer imposes punishment without trial. However, this is possible only if: the accused is an officer cadet or another ADF member who holds a rank below non-commissioned rank;[34] the charge is a minor disciplinary infringement;[35] and the accused admits the infringement and consents to the operation of the scheme.[36] The advantages of the scheme are its speed and simplicity and, for the accused, no permanent conduct record is generated. A commanding officer may appoint an officer or warrant officer as a discipline officer.[37]

|

|

Courts Martial

|

Defence Force Magistrate

|

Summary Authorities

|

Discipline

Officers

|

|||

|

General

|

Restricted

|

Superior

|

Commanding

Officer

|

Subordinate

|

|||

|

1998

|

0

|

6

|

40

|

9

|

1298

|

2122

|

1609

|

|

1999

|

0

|

5

|

49

|

8

|

1206

|

1707

|

1358

|

|

2000

|

2

|

14

|

47

|

10

|

1297

|

1793

|

1963

|

|

2001

|

2

|

5

|

38

|

5

|

1287

|

2114

|

2329

|

|

2002

|

0

|

3

|

46

|

7

|

1321

|

1991

|

3196

|

|

2003

|

0

|

1

|

44

|

7

|

1022

|

1735

|

2542

|

|

|

4

|

34

|

264

|

46

|

7431

|

11462

|

12997

|

FIGURE 1: ADF DISCIPLINE STATISTICS[38]

The DFDA also provides for certain reviews and appeals regarding initial decisions. A commanding officer reviews all convictions by subordinate summary authorities and transmits them to a legal officer, which considers them and may in turn transmit them to a reviewing authority.[39] A reviewing authority automatically considers convictions made by all other service tribunals.[40] A person convicted by a service tribunal may also lodge a petition for review by a reviewing authority.[41] The CDF or a Service Chief may also decide to conduct a further review.[42] Under the Defence Force Discipline Appeals Act 1955 (Cth), persons convicted (or acquitted on the ground of unsoundness of mind) by a court martial or a DFM may appeal to the Defence Force Discipline Appeals Tribunal on questions of law (or, with leave of the Tribunal, on a question of fact).[43] The Appeals Act also provides that the Tribunal may of its own motion or at the request of the appellant, the CDF or a Service Chief, refer a question of law arising in a proceeding to the Federal Court of Australia for decision.[44] An appellant, the CDF or a Service Chief may appeal the decision of the Tribunal to the Federal Court on a question of law.[45]

As we have noted previously, the overlap between offences under the DFDA and those under the general law creates some difficulty.[46] The High Court has held that there is no inconsistency between the DFDA and a State law that purports to govern conduct of an ADF member where that conduct also amounts to an offence under the DFDA, even if the penalties applicable under the two laws are different.[47] Accordingly, an ADF member could conceivably be tried twice for the same offence — once by a service tribunal and once by a civil court.[48] This difficulty is partially resolved by the following requirements:

(a) under s 63 of the DFDA, service tribunals cannot try certain serious offences such as murder and manslaughter without the prior consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions (‘DPP’);[49] and

(b) the current ADF policy is to refer all allegations of sexual assault to the DPP for investigation and prosecution, and to consult with the DPP in relation to matters where jurisdiction is in doubt.[50]

The Senate Report stated that: ‘[w]here a member is being prosecuted under the civilian criminal justice system, they cannot be subjected to the DFDA for the same or a similar offence’.[51] However, if an ADF member is tried in a civil court for an offence not covered by s 63 of the DFDA and found not guilty, the member’s protection from further prosecution by a service tribunal is uncertain.[52]

In this section, we first explain the constitutional problem of military service tribunals exercising judicial power and then proceed to examine the High Court’s early decisions regarding this problem in the context of the DFDA. This helps to understand the more recent decision in Re Aird. The section ends with a proposal for a new framework to determine the proper jurisdiction of service tribunals.

Section 5 1(vi) of the Australian Constitution grants to the Commonwealth Parliament the power to legislate in relation to defence in the following terms:

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: —…

(vi) The naval and military defence of the Commonwealth and of the several States, and the control of the forces to execute and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth.

Some disagreement exists as to whether the reference in the second clause of s 5 1(vi) to the ‘control of the forces’ alludes to the defence forces[53] or to ‘the work of law enforcement’.[54] We leave this issue to one side because, in any case, the first clause of s 51 (vi) is broad enough to encompass laws for the discipline of members of the ADF.

As highlighted above in section II of this article, the ‘offences’ for which ADF members may need to be disciplined range from those that are peculiar to the military to those that are substantially similar or identical to offences that may be committed by civilians. In addition, service tribunals have long been used in Australia to determine whether, and how, to discipline a defence force member who has allegedly committed an offence. This raises a constitutional problem. The first limb of the established doctrine of separation of powers in Australian constitutional law provides that only courts established in accordance with

Chapter III of the Constitution may exercise the judicial power of the Commonwealth.[55] This requirement derives from the structure of the Constitution and, in particular, s 71, which provides:

The judicial power of the Commonwealth shall be vested in a Federal Supreme Court, to be called the High Court of Australia, and in such other federal courts as the Parliament creates, and in such other courts as it invests with federal jurisdiction.

Section 71 is the first section of Chapter III of the Constitution, which is entitled ‘The Judicature’. The rest of Chapter III covers such matters as the jurisdiction of the High Court and the power of Parliament to define the jurisdiction of other federal courts. In addition, s 72 imposes on courts exercising the judicial power of the Commonwealth certain conditions that are intended to guarantee a degree of independence of decision-makers and thereby fairness in decision-making. In particular, a justice of such a court is to be appointed by the Governor-General in Council for a term expiring upon the attainment of the maximum age determined by Parliament for justices of that court (age 70 for the High Court). During the term of appointment, the remuneration provided to the justice is not to be diminished and the justice is not to be removed ‘except by the Governor-General in Council, on an address from both Houses of the Parliament in the same session, praying for such removal on the ground of proved misbehaviour or incapacity’. The separation of judicial power under the Constitution ‘provides a bulwark against both federal and state attempts ... to deploy any part of the judicial power of the Commonwealth otherwise than in accordance with Chapter III’.[56]

It is clear that service tribunals under the DFDA today are not constituted in accordance with Chapter III:

The provisions concerning judicial appointments, and the measures designed to impart independence and impartiality to civilian courts, do not apply to military tribunals. Whereas in Chapter III courts, judges are appointed by the Governor-General in council and have life tenure, in the military justice system, judicial officers are appointed from and responsible to the chain of command, and do not have the same security of tenure.[57]

Given that the defence power in s 51(vi) is expressed to be ‘subject to this Constitution’ (and hence s 71 and the separation of powers doctrine), how have service tribunals not constituted in accordance with Chapter III continued to operate? The general response of the High Court has been that such tribunals exercise ‘judicial power’, but not ‘the judicial power of the Commonwealth’ within the meaning of s 71.[58] We have previously expressed doubts about this distinction.[59] As Deane J has stated, ‘the legal rationalisation of any immunity of [the powers of service tribunals] from the net cast by Chapter III of the Constitution does not lie in a denial of their intrinsic identity either as judicial power or as part of the judicial power of the Commonwealth’.[60] The distinction between judicial power and judicial power of the Commonwealth is today even less persuasive given the ‘growing acceptance that territory courts exercise some federal jurisdiction’[61] even though they are created pursuant to s 122 of the Constitution, which is not expressed to be subject to the Constitution. We elaborate below[62] on our view that service tribunals do exercise the judicial power of the Commonwealth pursuant to a limited exception to the doctrine of separation of powers. In any event, although ‘[t]here has never been any real dispute’ about whether service tribunals under the DFDA exercise judicial power,[63] ‘[n]o one doubts’ that a military system of justice may operate outside Chapter III in at least some circumstances.[64] More problematic from a practical perspective is how to define the types of offences that relate to military discipline and the circumstances in which service tribunals may try them. We now address this issue in the context of three High Court decisions regarding the constitutionality of the DFDA prior to Re Aird.

Before its decision in Re Aird in 2004, the High Court had issued three major judgments relating to the constitutionality of service tribunals hearing specific alleged offences under s 61 of the DFDA :[65] Re Tracey; Ex parte Ryan[66] in 1989, Re Nolan; Ex parte Young[67] in 1991, and Re Tyler; Ex parte Foley[68] in 1994. Justice McHugh replaced Wilson J after Re Tracey, but otherwise the composition of the Court was the same in all three cases. Today, McHugh J is the only justice remaining from those earlier decisions. The complexity of, and variation between, the justices’ reasoning in Re Tracey, Re Nolan and Re Tyler reveal the intrinsic difficulties of law and principle in defining the proper limits for service tribunals — difficulties that are similar, but not identical, to those faced in other common law countries.[69] Understanding the reasoning in the earlier High Court cases also provides a basis for explaining the more recent decision in Re Aird.

In Re Tracey, by a 6:1 majority, the Court allowed a DFM to assert jurisdiction over charges of making an entry in a service document with intent to deceive, and charges of being absent without leave. The majority decision was expressed in a joint judgment by Mason CJ and Wilson and Dawson JJ, and another by Brennan and Toohey JJ. The first three justices considered that ‘[i]t is open to Parliament to provide that any conduct which constitutes a civil offence shall constitute a service offence, if committed by a defence member’, because such a rule ‘is sufficiently connected with the regulation of the forces and the good order and discipline of defence members’.[70] This approach has since been equated with the ‘service status’ approach prevailing in the United States[71] because it allows service tribunals to hear offences purely on the basis of the alleged offender’s status as a member of the defence forces. In contrast, Brennan and Toohey JJ adopted something closer to the ‘service connection’ approach prevailing in that country,[72] which examines the degree of connection between the offence and the defence forces. They determined that ‘proceedings may be brought against a defence member … for a service offence if, but only if, those proceedings can reasonably be regarded as substantially serving the purpose of maintaining or enforcing service discipline’.[73]

The approaches of Deane and Gaudron JJ to the jurisdictional scope of service tribunals in Re Tracey were ‘in general conformity’,[74] although Deane J alone dissented in part. Justice Deane warned, in relation to the separation of powers doctrine, that ‘[t]o ignore the significance of the doctrine or to discount the importance of safeguarding the true independence of the judicature upon which the doctrine is predicated is to run the risk of undermining, or even subverting, the Constitution’s only general guarantee of due process’.[75] Accordingly, he declared that the powers of service tribunals that are not Chapter III courts should be limited to the extent necessary for the maintenance and enforcement of military discipline[76] and, in the case of offences committed in Australia during peace-time, ‘to dealing with exclusively disciplinary offences’.[77] Justice Deane decided that the charges of absence without leave were exclusively disciplinary and therefore fell within the jurisdiction of the DFM. However, he considered that the charge of falsifying a service document fell outside that jurisdiction, and he therefore dissented in this regard.[78] Justice Gaudron determined that the validity under the defence power of laws providing for military discipline depends on whether those laws are ‘reasonably capable of being viewed as appropriate and adapted to the control of the forces when regard is had to what is necessary from a practical and administrative point of view’.[79] She considered that this condition was fulfilled with respect to the charges of absence without leave because they ‘have no counterpart under the general law’.[80] However, in the absence of sufficient facts and arguments as to whether the charge of falsifying a service document was substantially the same as a civil court offence, Gaudron J left this question to the magistrate.[81]

In Re Nolan, a Staff Sergeant in the Australian Regular Army was alleged to have falsified a pay list in order to receive more pay. A 4:3 majority of the Court concluded that a DFM had jurisdiction to hear and determine charges of falsifying a service document and using a false instrument. The sergeant could have been charged under the general criminal law with equivalent offences.[82] In the majority, Mason CJ and Dawson J maintained the views they expressed in Re Tracey.[83] Justices Brennan and Toohey also reiterated their view that proceedings may be brought under s 51(vi) of the Constitution ‘only when they can reasonably be regarded as substantially serving the purpose of maintaining or enforcing service discipline’.[84] The three dissenting justices were Deane[85] and Gaudron JJ[86] (essentially adopting the tests they advocated in Re Tracey) and McHugh J, who followed Justice Deane’s reasons and conclusion.[87]

In Re Tyler, five of the seven High Court justices held that a GCM had jurisdiction to hear a charge of dishonestly claiming a service allowance. As in Re Nolan, substantially similar offences existed under the general criminal law.[88] Again in the majority, Mason CJ and Dawson J followed their earlier approach but added that, even if the correct test were as set out by Brennan and Toohey JJ, that test was met.[89] Justices Brennan and Toohey applied their earlier test and concluded that ‘the proceedings in question can reasonably be regarded as substantially serving the purpose of maintaining or enforcing service discipline’.[90] Justice McHugh felt constrained to follow the majority decisions in Re Tracey and Re Nolan,[91] despite his opinion that, ‘unless a service tribunal is established under Chapter III of the Constitution, it has jurisdiction to deal with an “offence” only if that “offence” is exclusively disciplinary in character or is concerned with the disciplinary aspects of conduct which constitutes an offence against the general law’.[92] Justices Deane and Gaudron maintained their dissenting positions, again highlighting the underlying reasons for the separation of powers. Justice Deane concluded:

that I should continue to reject what I see as an unjustifiable denial of the applicability of the Constitution’s fundamental and overriding guarantee of judicial independence and due process to laws of the parliament providing for the trial and punishment of members of the armed forces for ordinary (in the sense of not exclusively disciplinary) offences committed within the jurisdiction of the ordinary courts in times of peace and general civil order.[93]

Similarly, Gaudron J ‘remain[ed] firmly of the view that persons who are subject to military discipline cannot, on that account, … be deprived of the protection which flows from Chapter III of the Constitution’.[94]

Re Aird concerned a rape allegedly committed by a member of the Royal Australian Regiment while on recreation leave in Thailand. Private Alpert was granted this period of leave from Malaysia, where his unit was serving at the Butterworth base of the Royal Malaysian Air Force.[95] As in the three previous High Court cases, Private Alpert was charged under s 61 of the DFDA, and the Solicitor-General relied on the defence power to support the validity of that provision.[96] The charge rested squarely on the basis that rape is an offence under ordinary criminal law.[97] As noted earlier, when Re Aird was decided, only McHugh J remained of the justices that decided Re Tracey, Re Nolan, and Re Tyler. It was therefore difficult to predict the outcome. However, Richard Tracey drew attention to the fact that a ‘balance will need to be struck between the exigencies which attend service operations and the need to ensure that service personnel are not deprived unnecessarily of the protections provided by the criminal process’.[98] The Court held, by a 4:3 majority, that the GCM had jurisdiction to hear this charge in the circumstances of the alleged offence. Justice McHugh adopted the approach of Brennan and Toohey JJ in the earlier cases, focusing on whether the grant of jurisdiction in these circumstances would substantially serve the purpose of maintaining or enforcing discipline of the defence forces — the so-called ‘service connection’ test.[99] Justices Callinan and Heydon also adopted this approach but dissented as to its application to the facts.[100] Even Kirby J (also in dissent), after professing a preference for the test of Deane J (and McHugh J in Re Nolan),[101] decided to assume in his reasons that the service connection test was the applicable rule ‘in the absence of wider argument … on the validity of the provisions of the Act under Chapter III, and in order to refine the point upon which this court now divides’.[102] Chief Justice Gleeson and Gummow J appeared to support the ‘sufficient connection’ or ‘service status’ test established by Mason CJ and Wilson and Dawson JJ,[103] while Hayne J based his decision on the reasons of both McHugh J and Gummow J in Re Aird.[104] In the words of Kirby J:

In the pretended application of the middle road accepted by Brennan and Toohey JJ in Re Tracey, this court is … , effectively, accepting the approach of Mason CJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ in that case. But that was an approach that has never, until now, commanded the assent of a majority of this court.[105]

According to Gleeson CJ, Private Alpert’s argument ‘turned mainly upon the circumstances that he was on recreational leave in Thailand at the time of the alleged conduct’.[106] Gleeson CJ rejected the claim that this fact modified the scope of the defence power.[107] Justice McHugh took note of the military circumstances of the alleged offence (including that Private Alpert was required in his application for leave to specify his address and telephone number during the period of leave, that a military bus drove him to the Thai border, and that he was accompanied by other soldiers) as well as the recreational aspects (for example, that the visit to Thailand had no military content and that Private Alpert entered Thailand on his civilian passport, wore civilian clothes, and paid for the trip).[108] Despite these various circumstances, McHugh J stated that ‘I would have thought that it was beyond argument that … the defence power extended to making it an offence for a serving member of the armed forces to commit the offence of rape while on leave in a foreign country’.[109] This statement is surprising, given Justice McHugh’s own stated preference for a more stringent test than the one he applied in this case.

Justice McHugh supported his conclusion that the GCM had jurisdiction to hear this charge with considerations such as the likely criticism by local citizenry of ADF members engaging in undesirable conduct overseas, the possible denial of entry to ADF members by foreign governments in response to such conduct, and the likely reluctance of ADF members to serve with personnel who are guilty of rape.[110] Factors such as these do not justify limiting the guarantees provided by the separation of powers doctrine in Australian constitutional law. As Callinan and Heydon JJ argued in their dissent:

Equally it might be asserted that misbehaviour by other Australian groups of visitors to foreign countries, … such as sporting teams and their followers, would be likely to provoke protest and resistance to the reception of Australians generally, including members of its defence forces. Strictly these are factual matters and no fact material to them appears in the case stated or otherwise.[111]

Justice Kirby also addressed the significance of the location of the alleged offence. He suggested that Thailand is ‘not lawless’;[112] it is ‘a place with a functioning legal system, applicable to visitors and with a law of rape … applicable to the … alleged offence’.[113] Therefore, the ‘proper response of the Australian service authorities to the complainant’s accusation … was to inform the complaint to the Thai authorities’.[114] As detailed further below, we agree with Kirby J that the appropriate test for identifying the requisite relationship between the discipline of the ADF and an offence to be tried by a service tribunal not constituted in accordance with Chapter III of the Constitution is that set forth by Deane J in Re Tracey. However, we are not persuaded that the application of that test means that the prosecution of the alleged offence in Re Aird should have been left to the Thai courts.

The complainant did not in fact complain to the Thai authorities and, as Kirby J acknowledged, ‘[i]t is possible that a belated complaint … would now produce no redress’.[115] Justice Kirby regarded this result as according with the rights of Private Alpert, who denied the accusation and contested the validity of the court martial to hear it.[116] However, ‘there may well be other situations in which Australian personnel would wish to be treated as being subject to Australian law in preference to the law of a country in which they are serving’.[117] Furthermore, the constitutional doctrine of the separation of powers is designed to protect ADF members, not so that they have the best chance of escaping prosecution or punishment for alleged offences, but so that they benefit from the safeguards of Chapter III courts in proceedings against them. Neither the courts of Thailand nor those of any other country are constituted pursuant to Chapter III of the Australian Constitution. The justices of the High Court would tread a dangerous path were they to base their decisions regarding the jurisdictional scope of Australian service tribunals on their own assessment of the degree of fairness or lawfulness existing in the legal systems of other countries.

In appendix 1 to this article, we summarise our understanding of the rulings and reasoning of the High Court in these four cases regarding the relationship required between defence force discipline and an offence to be tried by a service tribunal that is not a Chapter III court, in connection with the DFDA. One commentator concludes that ‘[t]he decision in Aird, while understandable and supportable, ultimately does little to settle the disquiet in this field’.[118] In the next section, we propose a way of clarifying the constitutionality of service tribunals in light of the judgments in Re Aird. At the time of writing, the seven justices who decided Re Aird remain on the Court.

Several years ago, we put forward our opinion that s 61 of the DFDA is constitutionally invalid in that it converts ordinary civil offences, in times of peace within Australia, into military offences that may be tried in a service tribunal that is not constituted as a Chapter III court.[119] It is therefore necessary to ‘read down’ the provision to its constitutional limits.[120] We encouraged a reassessment of the constitutional validity of such tribunals to acknowledge that:

for reasons of practicality and national security, an exception to the separation of powers doctrine allows service tribunals to exercise the judicial power of the Commonwealth. However, this power extends only to the minimum degree necessary to enforce military discipline, and no further. Thus, in ordinary circumstances service tribunals should only be entitled to hear exclusively disciplinary offences … In circumstances of wartime and service outside Australia, service tribunals should be able to hear offences that are substantially similar or identical to civil offences.[121]

At the time, we were focusing on the offences addressed by the High Court in Re Tracey, Re Nolan, and Re Tyler, all of which were allegedly committed by ADF members during service in Australia. Nevertheless, we acknowledged that different considerations would apply to offences allegedly committed during periods of war or overseas service. Re Aird arguably presented the High Court with such an offence. Today, to use the words once written by McHugh J, we ‘remain convinced that the reasoning of the majority justices in Re Nolan and Re Tracey is erroneous’.[122] Moreover, after reflecting on the reasoning in Re Aird, we largely maintain our views regarding the greater constitutional leeway accorded to military justice in times of war or service outside Australia.

As we stated previously, ‘[r]ecognising that the exercise of judicial power by service tribunals involves an exception to s 71 and the separation of powers doctrine’ would bring into focus the competing values of ADF members’ individual rights, on the one hand, and the effectiveness of the ADF as a whole, on the other.[123] Fiona Wheeler suggests that the High Court has recognized service tribunals as an exception to this doctrine.[124] Justice Deane in dissent in Re Tracey did make clear that the powers of service tribunals to enforce military discipline constitute ‘a qualification to the provisions of Chapter III’.[125] Justice Kirby also referred to the ‘exceptional jurisdiction of service tribunals in Australia’ in Re Aird.[126] However, the majority justices have not justified their approaches in these terms, as discussed above.[127] In Re Nolan, Brennan and Toohey JJ referred to this ‘apparent exception’,[128] only to insist that ‘there can be no real exception’[129] to:

the imperative of Chapter III of the Constitution that jurisdiction to hear and determine charges of offences against a law of the Commonwealth be vested only in Chapter III courts. … If service offences were characterised as a class of offences against a law of the Commonwealth, the vesting of jurisdiction in military tribunals would be precluded, not only in respect of service offences which have a civil law equivalent and which are committed in Australia in peacetime but in respect of all service offences wherever and whenever committed and whether having a civil law equivalent or not.[130]

Justices Brennan and Toohey thus suggested that, if Chapter III admits of an exception for service tribunals in times of war or outside Australia, it must admit of such an exception also in times of peace and within Australia. Conversely, in Re Aird, Kirby, Callinan and Heydon JJ took the view that, if a service tribunal were entitled to try the offence of rape allegedly committed by Private Alpert in Thailand, logically it would also be entitled to try such an offence allegedly committed by an ADF member in Australia.[131] But neither result necessarily follows. The interests of military effectiveness and true military justice are best served by conceding that service tribunals may operate outside Chapter III only in exceptional circumstances associated with war or combat, or in the absence of a civilian equivalent in Australian law to an offence that is necessary for the enforcement of military discipline.

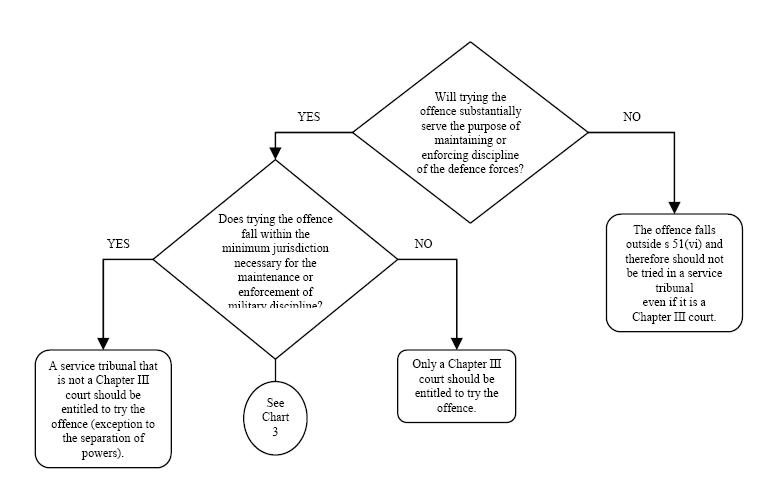

Therefore, we suggest a two-step test for delineating the scope of the defence power in connection with service tribunals hearing alleged offences. First, using the approach of Brennan and Toohey JJ, we ask whether trying the offence would substantially serve the purpose of maintaining or enforcing discipline of the defence forces. If the answer is no, the offence falls outside s 5 1(vi) of the Constitution and should not be tried in a service tribunal, regardless of whether that tribunal is constituted as a Chapter III court. This is because the requirement of substantially serving the purpose of ADF discipline derives not from Chapter III but from the defence power itself.[132] This fact seems to have become lost in much of the High Court reasoning over the years. Second, adopting the approach of Deane J, we ask whether trying the offence would fall within the minimum jurisdiction necessary for service tribunals to maintain or enforce military discipline. If not, only a Chapter III court may validly try the offence. It is this requirement that stems from Chapter III and the doctrine of separation of powers. The exception to the separation of powers doctrine applies to cases that fall within the minimum jurisdiction necessary for military discipline. We use the words ‘minimum jurisdiction necessary’ rather than ‘exclusively disciplinary’, although both could describe Justice Deane’s approach, because the former formulation is better suited to accommodating the different circumstances in which an offence may occur, as discussed further below.[133] Appendix 2 to this article demonstrates in schematic form our suggested approach to defining the scope of the defence power in connection with military justice.

Our proposed test resolves several problems that various justices identified in Re Aird, and it could be consistent with the reasoning of a majority of them. All but Kirby J decided the matter as if Chapter III was not at issue, because Private Alpert’s arguments did not focus on Chapter III.[134] They may thereby have hoped to sidestep the constitutional dilemma that has plagued the Court for decades. Yet, as Kirby J rightly replied, ‘Chapter III is not, and cannot be, disjoined from the Constitution. Donning judicial blinkers, for whatever reason, will not make Chapter III go away’.[135] The fact that the jurisdiction of a service tribunal falls within the terms of s 5 1(vi) does not necessarily mean that it falls within the exception to Chapter III. To answer only the first step is to leave unanswered the ultimate question of constitutionality. Nevertheless, that six justices purported to exclude consideration of Chapter III indicates that Re Aird may not fully reveal their opinions on this issue. Those who adopted the ‘substantially serving the purpose’ or ‘sufficient connection’ tests for the purpose of resolving that dispute might well prefer the ‘exclusively disciplinary’ test in resolving another.[136] In addition, their detachment of Chapter III from s 51 (vi) could reflect a recognition that these provisions impose different requirements on service tribunals.

The relatively low threshold of the first step of our suggested test, combined with the stringency of the second step, addresses one of the concerns identified by Kirby, Callinan, and Heydon JJ, as foreshadowed earlier:

if the test of service connection is to be applied on the basis that it will be satisfied if the acts alleged constitute an undisciplined application of force, or conduct that would be regarded as abhorrent by other soldiers, then it is difficult to see how any serious crime committed anywhere, including in Australia, under any circumstances would not be susceptible to the military jurisdiction exclusively.[137]

It is unrealistic to argue that an offence of rape by an ADF member has no impact on military discipline, or that the fact that the member is on leave eliminates any such impact. In fact, on one view, ‘all behaviour of the members of a disciplined force is germane to the control and effectiveness of that force’.[138] In any case, it goes without saying that ‘[i]t is central to a disciplined defence force that its members are not persons who engage in uncontrolled violence’.[139] Evidently, rape ‘involves serious violence and disregard for the dignity of the victim, and clearly has the capacity to affect discipline, morale, and the capability of the defence force to carry out its assignments’.[140] However, confessing the connection between rape and discipline does not mean that a charge of rape by an ADF member, wherever and whenever allegedly committed, must necessarily be brought before a service tribunal. It simply means that the offence falls within s 51(vi). Whether it is also consistent with Chapter III will depend on the application of the second step of our test.

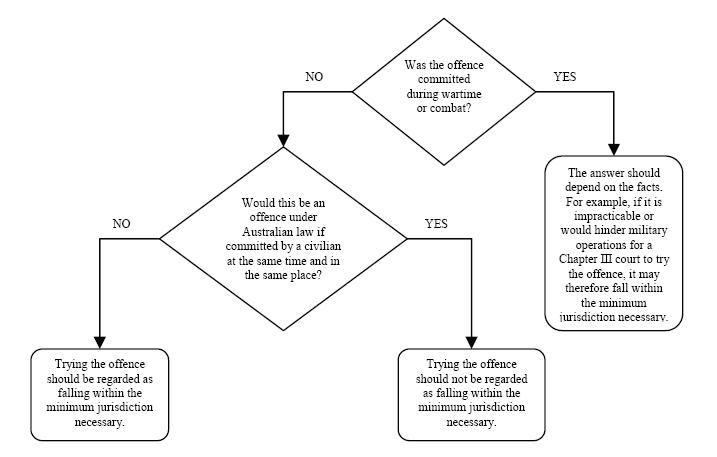

With this in mind, we turn to the question of how to identify, in specific cases, the minimum jurisdiction necessary for service tribunals to maintain or enforce military discipline.

Whether a particular offence falls within the minimum jurisdiction necessary for service tribunals to enforce or maintain military discipline will depend on the specific facts surrounding its alleged commission. Indeed, the scope of the defence power varies not only in relation to military justice but also more generally. As George Williams explains:

The central High Court doctrine concerning the defence power is that the power waxes and wanes. It is a fixed concept with a changing content because its scope depends on Australia’s defence needs at any given time. … The conditions that determine the scope of the power … are factual conditions, such as … whether Australia is currently at war or facing a real or perceived threat of invasion.[141]

Most would agree that service tribunals require a greater scope for operations in circumstances of war, combat, or a threat to national security.[142] In such circumstances, trying an offence may fall within the minimum jurisdiction necessary for the maintenance or enforcement of military discipline if the facts show, for example, that it is impracticable or would unduly hinder military effectiveness for a Chapter III court to try the offence. In times of relative peace, the issue is trickier, especially as regards ADF members serving outside Australia. In Re Tracey, Gaudron J recognised the need for service tribunals to try offences allegedly committed outside Australia, due to ‘practical and administrative considerations’.[143] Justice Deane also stated in relation to such tribunals:

what lies within their legitimate ambit in relation to members of an armed force on active duty in a place beyond the reach of the ordinary criminal law and courts has long been seen as being more extensive than what lies within their legitimate ambit in relation to a member of a standing army within the jurisdiction of the ordinary domestic courts in time of peace.[144]

In contrast, as highlighted earlier,[145] Kirby J denied the significance of the location of the alleged offence in Thailand in Re Aird, given the availability of Thailand’s courts to prosecute the offence. For reasons stated above, we prefer to interpret the passage of Deane J as referring to the ‘ordinary criminal law and courts’ of Australia rather than those of another country.

The question then arises how to determine whether an offence is ‘exclusively disciplinary’ in times of peace, whether within or outside Australia, in which case it will fall within the ‘minimum jurisdiction necessary’ for service tribunals. One possibility would be to allow the relevant justices simply to assess whether the offence is of a purely military nature or whether it also should be of concern to the civilian authorities in Australia. Thus, even if rape were not an offence in Australia, the High Court might decide that it was of such gravity or involved such violence that it had to be handled by a civilian (Chapter III) court. This would be a curious result if Parliament had decided not to provide for civilian courts to prosecute any such offence, whether committed by a civilian or an ADF member.

The point is made clearer by a suggestion of Callinan and Heydon JJ in Re Aird. They suggested, with reference to the external affairs power, that ‘[i]f the Commonwealth desires to try and punish soldiers in the position of [Private Alpert], then it would probably be possible for it to make all crimes of any character committed abroad by Australian nationals, whether soldiers or not, triable and punishable in Australia’.[146] Is it really for the High Court to advise the Parliament to create an offence applicable to all Australian civilians in order to permit the prosecution of military service offences overseas? We think not. Therefore, where the prosecution of an offence would substantially serve the purpose of military discipline within the defence power, but Parliament has chosen not to make it an offence for a civilian to commit the relevant act at the same time and in the same place, the offence properly falls within the exception to Chapter III as part of the minimum jurisdiction necessary for service tribunals to maintain or enforce military discipline. This leaves the identification of ‘civilian’ offences with the Parliament, which is where it should be.

We therefore agree with the majority conclusion in Re Aird that a GCM had jurisdiction to hear the charge against Private Alpert. It was common ground that the alleged conduct ‘would not be an offence under Australian law because it occurred in Thailand’.[147] Accordingly, the offence must fall within the minimum jurisdiction necessary for service tribunals to maintain or enforce military discipline because, if not prosecuted in such a tribunal, it would not be prosecuted in Australia at all. The result would be that the alleged offence would go unheard and unpunished in Australia, despite the fact that its prosecution would substantially serve the purpose of maintaining or enforcing military discipline, as established in the first step of our test. Allowing prosecutions of this kind should not be disturbing, given the experience of the DFDA to date:

Since the DFDA was introduced the ADF has seen outstanding service on peacekeeping and warlike operations in many parts of the world. … It appears that almost no criminal offences have been tried in any theatre of operations during this time.[148]

If, on the other hand, it were an offence under Australian law for a civilian to commit rape in Thailand, the outcome would be different. A parallel example arises from Chief Justice Gleeson’s reference to the Crimes (Child Sex Tourism) Amendment Act 1994 (Cth), which ‘makes certain kinds of sexual misconduct committed outside Australia an offence against Australian law’.[149] Had Private Alpert been accused of committing an offence under that legislation while on leave in Thailand, we would say that trying this offence is not within the minimum jurisdiction necessary of service tribunals outside Chapter III, because it could be properly tried in a civilian court in Australia.

Appendix 3 to this article summarises our proposed approach to determining, in relation to a particular offence, the minimum jurisdiction necessary for the enforcement of military discipline by service tribunals. We now consider the Senate Report on the effectiveness of Australia’s military justice system, taking into account our new framework.

On 30 October 2003, the Australian Senate referred to the Senate Committee an inquiry into the effectiveness of the military justice system. Its terms of reference included: ‘the effectiveness of the Australian military justice system in providing impartial, rigorous and fair outcomes’ and ‘the impact of Government initiatives to improve the military justice system’.[150] The Senate Committee received 71 public submissions, 63 confidential submissions and a number of supplementary submissions. It held eleven public hearings and seven in–camera hearings. After some delay,[151] the Senate Report was tabled on 16 June 2005.

The unanimous recommendations of the Senate Committee call for major reforms to the Australian military justice system. The recommendations that are most relevant to our discussion are those concerning the withdrawal of civilian and civilian-type offences from the ADF discipline system and the establishment of a Permanent Military Court. Below, we review and evaluate these key recommendations and compare them with our own proposed framework on the constitutional scope of service tribunals. We nevertheless agree with the Senate Committee’s view that the goal of improving military justice in Australia ‘should be to structure a tribunal system that can protect the rights of Service personnel to the fullest extent possible, whilst simultaneously accommodating the functional requirements of the ADF’, and not merely to ensure constitutionality or High Court approval.[152]

One of the major recommendations of the Senate Committee is that the ADF refer to civilian authorities, for investigation and prosecution, all suspected criminal activity by ADF members that are crimes in the general community or that have a close civilian counterpart and are committed during peacetime.[153] The relevant civilian authorities would be the State or Territory police (for suspected criminal activity in Australia) and the Australian Federal Police (for activity overseas).[154] Civilian authorities could refer back to the military cases they decided not to investigate and the ADF could still prosecute these cases as well as ‘offences that have no civilian equivalents’.[155] For either type of offence,[156] it seems that the ADF would pursue proceedings only if this would be ‘regarded as substantially serving the purpose of maintaining or enforcing Service discipline’.[157] This recommendation mirrors some of the suggestions made by Mr Michael Griffin,[158] a solicitor and DFM appointed by the Senate Committee to provide assistance as a legal expert in analysing the available evidence.[159] In Mr Griffin’s words:

Few would argue with the idea that the ADF needs to maintain its own disciplinary system. However, that may not extend to operating an entire criminal system in duplication of the civilian environment. Practical considerations and harsh reality call into question the continued maintenance out of the public purse of a small and under-skilled criminal investigation service.[160]

Accordingly, ‘outsourcing’ to the civilian criminal justice system would allow the ADF to focus on its ‘core business’.[161] In precluding military prosecutions that would not substantially serve the purpose of maintaining service discipline, the Senate Committee’s proposal can be seen as adopting the approach of Brennan and Toohey JJ in the trio of High Court cases before Re Aird, much as we do in the first step of our suggested framework. In our view, this would be a positive step towards preventing prosecutions that fall outside the defence power in s 51(vi) of the Constitution. Further, in proposing that the ADF refer to the civilian police offences that are not purely disciplinary,[162] the Senate Committee also incorporates Justice Deane’s test, as in our second step. This would help minimise the risk of violating the separation of powers doctrine and Chapter III of the Constitution. However, the Senate Committee leaves open the possibility of civilian police declining to investigate a matter and therefore returning it to the military. This means that a service tribunal could prosecute, in peace time, a charge that is not exclusively disciplinary. To determine whether this would be constitutional under the new system envisaged by the Senate Committee, we turn to its recommendation regarding a Permanent Military Court.

The Senate Report recommends the establishment of an independent Permanent Military Court (‘PMC’) in accordance with Chapter III of the Constitution.[163] This court would be ‘staffed by independently appointed judges possessing extensive civilian and military experience’.[164] Although the Senate Report does not say so explicitly, it appears that the court would replace the existing courts martial and DFMs,[165] as shown in Figure 2 below. The PMC would try offences under the DFDA that are currently tried at the court martial or DFM level.[166] In particular, the PMC would try serious offences. In addition, the Senate Committee noted that summary proceedings affect the highest proportion of military personnel. It considered ‘that Service personnel should have the right to access impartial and independent tribunals at all levels within the military justice system – the right should not be confined to ‘serious’ offences’.[167] Accordingly, the Senate Report recommends allowing ADF members to elect trial before the PMC for summary offences, and allowing them to appeal summary decisions to the PMC.[168]

FIGURE 2: THE SENATE COMMITTEE’S PROPOSED CHANGES TO SERVICE TRIBUNALS

In making this recommendation, the Senate Committee considered developments in other jurisdictions. It noted that both Canada and the UK possessed a similar military justice system to Australia and have introduced wide-ranging reforms to remove adjudicatory functions from the chain of command.[169] Referring to criticisms of the American system of military justice, it noted that US military judges, like Australian judge advocates, ‘lack tenure, are appointed from within the chain of command, and preside over tribunals that “appear without warning and vanish without a trace”’.[170]

The Senate Committee suggested that its proposed changes:

would extend and protect Service personnel’s inherent rights and freedoms, leading to more impartial, rigorous and fair outcomes[171]

and

provide for ADF control over discipline, yet still allow for the protection of individual rights. The evidence to this inquiry shows that an independent judiciary could simultaneously support the maintenance of Service discipline, maintain operational effectiveness, and protect the rights of Service personnel.[172]

The Senate Committee’s recommendation regarding a PMC is similar to that advocated by the JAG.[173] The JAG noted that ‘the traditional British and Canadian court martial structures (which largely reflect the current Australian arrangements) have been found not to be independent and impartial’.[174] The constitutional challenges that the DFDA has survived did not focus on whether service tribunals afford a ‘fair and impartial’ trial, so the system could still be legally vulnerable.[175] The Senate Committee also appears to have taken up the JAG’s suggestion that ‘consideration be given to providing the accused in each case with a right to elect trial before a DFM or court martial’.[176]

Mr David Richards, a law firm partner, also recommended in his submission to the Senate Committee the creation of a PMC with independent judges with fixed appointments until retirement.[177] He considered that this would address the lack of fairness and independence in service tribunals due to such factors as the CDF’s control over the appointment of convening authorities and the CDF’s role in appointing judge advocates, court martial presidents and members, and DFMs.[178]

Finally, Mr Griffin also noted the limitations of the current system in the absence of a Chapter III court. He accepted the value and importance of having military officers hearing military offences such as desertion, but questioned the importance of having officers decide strictly criminal offences, especially given the small number of criminal matters tried outside Australia.[179] The Senate Committee noted in this regard that, of the ‘29 Service personnel tried between 2000 and 2004, only four trials were conducted overseas, and all were Service, as opposed to criminal, charges’.[180]

In reaching its recommendation regarding a PMC, the Senate Committee took note of Re Aird and the earlier High Court decisions.[181] It pointed out that the creation of a PMC in accordance with Chapter III of the Constitution could circumvent a potential challenge to the validity of service tribunals.[182] Indeed, the existence of a PMC would directly address concerns about the independence of service tribunals and the fairness of their proceedings, to the benefit of ADF members that come before them. At the same time, it would enable the ADF to ensure that the decision-makers in such matters are familiar not only with civilian law but also with the particular needs of military operations.

We have only one doubt, as foreshadowed earlier, which relates to civilian offences that are referred back to the military. By definition, these offences are not exclusively disciplinary and, in peace time, they do not form part of the minimum jurisdiction necessary for the enforcement or maintenance of military discipline. Accordingly, they should be tried by a Chapter III court. Although it is not entirely clear, the Senate Committee’s proposal does not appear to guarantee this. Rather, for summary offences, whether or not they are exclusively disciplinary, it seems to ensure only a right of appeal to the PMC and a right to elect trial by the PMC.[183] In practice, the right to elect trial in a particular manner might not be as valuable to an ADF member as it might be to a civilian. Given the involvement of commanding officers in summary offences, and the fact that the accused would have an opportunity to elect trial by the PMC only after the commanding officer or their delegate has decided to initiate prosecution or lay charges, the accused ADF member might feel some pressure to waive their right to a fuller trial. At the very least, safeguards would need to be put in place to avoid this.

The decision in Re Aird may have disappointed and surprised constitutional and defence lawyers alike, as it provides little clear guidance on the constitutional scope of service tribunals operating outside Chapter III of the Constitution. Disagreements about this issue have stubbornly persisted, despite the fact that, 10 years since the decision in Re Tyler, the composition of the High Court is almost entirely different. But perhaps we are getting closer to an answer, in the form of the long-standing ‘substantially serving the purpose’ test of Brennan and Toohey JJ combined with the equally well-established (if dissenting) ‘minimum jurisdiction necessary’ test of Deane J. Given the right case, a majority of the Court might agree that the first of these ensures that service tribunals operate within the defence power, while the second confirms that they fall within the exception to Chapter III. And the key questions in applying this second test are directed not simply to the location of the alleged offence, but to the surrounding circumstances and the application of Australian civilian laws to it.

The Australia Defence Association has cautioned that ‘[w]e tinker with the ADF’s disciplinary code at some peril unless this is done with some understanding of what we require the defence to do in war’.[184] Nevertheless, in our view, the recommendations of the Senate Committee have merit. The creation of a Permanent Military Court, together with a greater focus on the connection between particular offences, military discipline and civilian laws, would bolster the individual rights of accused ADF members without sacrificing military effectiveness. The precise details for the proposed system need to be carefully considered, taking into account the different circumstances and locations in which the ADF operates, and the primary role of the civilian justice system in handling civilian offences. In the words of the Senate Committee’s Chairman, upon tabling the Senate Report in the Senate, ‘service men and women who fight for our ideals should not be denied them by virtue of their service’.

The Senate Report on the military justice system and our analysis of the constitutional validity of service tribunals under the DFDA in light of Re Aird both point to the need for fundamental reform of military justice in Australia to increase independence and fairness in dealing with alleged offences. Our framework for determining which offences a service tribunal that is not a Chapter III court should be entitled to try is concerned with constitutionality. Constitutionality alone is not necessarily enough, as the Senate Committee pointed out, but it is certainly a good start. Despite 10 years of various inquiries with little or no impact, there are grounds for optimism that the Senate Committee’s bi-partisan and unanimous recommendations will drive the changes required to meet this threshold.

APPENDIX 1

HIGH COURT RULINGS ON THE RELATIONSHIP REQUIRED BETWEEN

DEFENCE FORCE DISCIPLINE AND AN OFFENCE TO BE TRIED BY A SERVICE

TRIBUNAL THAT IS NOT A CHAPTER III COURT

|

|

Re Tracey (1989)

|

Re Nolan (1991)

|

Re Tyler (1994)

|

Re Aird (2004)

|

|

|

Outcome (by majority ruling)

|

Defence force

magistrate had

jurisdiction to hear

charges of making an

entry in a service

document with intent

to deceive, and of

being absent without

leave.

|

Defence force

magistrate had

jurisdiction to

hear charges of

falsifying a service document.

|

General court

martial had

jurisdiction to

hear a charge of

dishonestly

claiming a

service allowance.

|

General court

martial had

jurisdiction to hear

charge of rape

committed in

Thailand while on

leave from service in Malaysia.

|

|

|

Preferred

test

|

Sufficient

connection with

regulation of the

forces, good order

and discipline of

defence members

(‘service status’)

|

Mason CJ

Wilson J

Dawson J

|

Mason CJ

Dawson J

|

Mason CJ

Dawson J185

|

Gleeson CJ

Gummow J

|

|

Substantially

serving the purpose

of maintaining or

enforcing

discipline of the

defence forces

(‘service

connection’)

|

Brennan J

Toohey J

|

Brennan J

Toohey J

|

Brennan J

Toohey J

|

McHugh J

Hayne J

Callinan J (diss.)

Heydon J (diss.)

|

|

|

Appropriate and

adapted to control

of the defence

forces

|

Gaudron J186

|

Gaudron J (diss.)

|

Gaudron J (diss.)

|

—

|

|

|

Minimum

jurisdiction

necessary for the

enforcement of

military discipline

— exclusively

disciplinary

|

Deane J (dissenting in

part)[187]

|

Deane J (diss.)

McHugh J (diss.)

|

Deane J (diss.)

McHugh J188

|

Kirby J189 (diss.)

|

|

APPENDIX 2

THE SCOPE OF MILITARY JUSTICE UNDER THE DEFENCE POWER

APPENDIX 3

THE MINIMUM JURISDICTION NECESSARY FOR THE MAINTENANCE

OR ENFORCEMENT OF MILITARY DISCIPLINE

[#] The views expressed in this article are personal to the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government.

[*] LLM (Harv), LLB (Hons) (Melb), BCom (Hons) (Melb). Senior Fellow, Asia Pacific Centre for Military Law, University of Melbourne Law School; Lieutenant, Australian Army Reserve. Email <a.mitchell@unimelb.edu.au>.

[**] LLM (Harv), LLB (Hons) (Melb), BSc (Melb). Senior Fellow, Asia Pacific Centre for Military Law, University of Melbourne Law School. Email <tania.voon@unimelb.edu.au>.

[1] Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, Parliament of Australia, The effectiveness of Australia ’s military justice system (2005) [110].

[3] Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee, Parliament of Australia, The efectiveness of Australia’s military justice system (2005). The Senate Report addresses both administration and discipline in the military justice system. This article focuses on the disciplinary aspects of the system.

[4] Defence Act 1903 (Cth) s 8.

[6] Chief of Navy, Chief of Army and Chief of Air Force.

[7] Defence Act 1903 (Cth) s 9.

[8] DFDA s 9A.

[9] Department of Defence, Annual Report 2003–04 (2004) 260.

[16] General Peter Cosgrove, Chief of the Defence Force, Department of Defence, Submission P16 to the Senate Committee (19 February 2004) [2.19]. See also Senate Report, above n 1, [2.14].

[18] DFDA s 115. For example, courts martial cannot hear custodial offences (certain offences committed by detainees) and require the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions to proceed with certain offences.

[19] Legislation has been proposed under which the Register of Military Justice would convene courts martial and appoint panel members, although this would still occur through the command chain. See General Peter Cosgrove, CDF, Department of Defence, Submission P16 to the Senate Committee (19 February 2004) [2.45].

[20] DFDA s 134(1): ‘In proceedings before a court martial, the judge advocate shall give any ruling, and exercise any discretion, that, in accordance with the law in force in the Jervis Bay Territory, would be given or exercised by a judge in a trial by jury’.

[21] DFDA s 116(1).

[22] A GCM comprises a President, who is not below the naval rank of Captain or the rank of Colonel or Group Captain, and not less than four other members. An RCM comprises a President who is not below the rank of Commander, Lieutenant Colonel or Wing Commander, and not less than two other members: DFDA ss 114, 116(2).

[23] A GCM has wider powers of punishment than an RCM. A GCM may impose the maximum punishment of imprisonment or detention provided for in the legislation creating the offence (including life imprisonment). A RCM may impose a punishment of imprisonment or detention not exceeding six months: DFDA sch 2.

[24] The Judge Advocate General notes that ‘DFM trials have been conducted in connection with most of our recent overseas developments, including Rwanda, Somalia, Cambodia, East Timor and the Middle East’: Major General Justice Roberts-Smith, Judge Advocate General, ADF, Submission P27 to the Senate Committee (16 February 2004) [3].

[25] DFMs are similar to Military Judges under the United States Code of Military Justice.

[26] DFDA s 129.

[27] JAG Report under DFDA s 196A(1) for 2003, Annex F, [6].

[28] DFDA ss 106–107.

[29] DFDA s 105(1).

[30] DFDA s 105(1).

[31] JAG Report under DFDA s 196A(1) for 2003, Annex A, [4].

[32] See generally DFDA pt IXA: ‘Special procedures relating to certain minor disciplinary infringements’.

[33] DFDA Part IXA was created by the Defence Legislation Amendment Act 1995 (Cth).

[34] ‘[M]ember below non commissioned rank means a member of the Defence Force who is not an officer, a warrant officer or a non commissioned officer’: DFDA s 3.

[35] Specifically: absence from duty (s 23); disobeying a lawful command (s 27); failing to comply with a general order (s 29); being absent, asleep or intoxicated when on guard or on watch (s 32(1)); negligence in performance of duty (s 35); prejudicial conduct (s 60); or absence without leave (s 24) (for less than 3 hours).

[36] A discipline officer may impose punishments ranging from a fine of not more than one day’s pay to a remand: DFDA s 169F(1).

[37] DFDA s 169B.

[38] Source: JAG Reports under DFDA s 196A(1) for 1998-2003.

[39] DFDA s 151.

[40] DFDAs 152.

[41] DFDA s 153.

[42] DFDA s 155.

[43] Defence Force Discipline Appeals Act 1955 (Cth) s 20.

[44] Defence Force Discipline Appeals Act 1955 (Cth) s 51.

[45] Defence Force Discipline Appeals Act 1955 (Cth) s 52.

[46] Andrew Mitchell and Tania Voon, ‘Defence of the Indefensible? Reassessing the Constitutional Validity of Military Service Tribunals in Australia’ (1999) 27 Federal Law Review 499, 503-4.

[47] McWaters v Day [1989] HCA 59; (1989) 168 CLR 289.

[48] Re Nolan; Ex parte Young [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 172 CLR 460 (‘Re Nolan’), 493-4, 499 (Gaudron J).

[49] ‘Major crimes like rape, murder, theft and things of that nature are always referred to the civilian courts and, wherever possible, if there is a way of referring a matter to the civilian courts the defence department does so’: Commonwealth, Senate Debates, 21 June 1999, No 8, 5734 (Senator MacGibbon).

[50] Defence Instruction (General) PERS 45-1, Jurisdiction Under the DFDA – Guidance for Military Commanders.

[51] Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, Parliament of Australia, Military Justice Procedures in the Australian Defence Force (1999) [2.15].

[52] Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (Defence Subcommittee), Reference: Military Justice Procedures, Official Hansard Report, 19 June 1998, 290.

[53] See, eg, Re Tracey; Ex parte Ryan [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 166 CLR 518 (‘Re Tracey’), 564 (Brennan and Toohey JJ).

[54] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 166 CLR 518, 540 (Mason CJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ) (quoted with approval in Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [60-1] (Gummow J)).

[55] See, eg, Huddart, Parker & Co Pty Ltd v Moorehead [1909] HCA 36; (1909) 8 CLR 330, 355 (Griffith CJ); Brandy v Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission [1995] HCA 10; (1995) 183 CLR 245, [22, 26, 44] (Mason CJ, Brennan and Toohey JJ), [20] (Deane, Dawson, Gaudron and McHugh JJ). See also Cheryl Saunders, ‘The Separation of Powers’ in Brian Opeskin and Fiona Wheeler (eds), The Australian Federal Judicial System (2000) 3.

[56] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [108] (Kirby J).

[57] Senate Report [5.37].

[58] See, eg, Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [31]; Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 166 CLR 518, 537, 574, 582, 598; R v Bevan; Ex parte Elias and Gordon [1942] HCA 12; (1942) 66 CLR 452 (‘R v Bevan’), 467-8; R v Cox; Ex parte Smith [1945] HCA 18; (1945) 71 CLR 1 (‘R v Cox’), 23-4.

[59] Andrew Mitchell and Tania Voon, above n 46, 511-12.

[60] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 41.

[61] Fiona Wheeler, ‘Due Process, Judicial Power and Chapter III in the New High Court’ (2004) 32 Federal Law Review 205, 218. See Putland v R [2004] HCA 8; (2004) 204 ALR 455, [1] (Gleeson CJ), [33] (Gummow and Heydon JJ), [66, 73] (Kirby J).

[62] See section IIID3 of this article.

[63] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 166 CLR 518, 540 (Mason CJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ).

[64] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [95] (Kirby J) (referring to the operation of ‘a non-judicial system of military discipline in time of war or civic danger’).

[65] As regards the constitutional validity of military service tribunals under previous defence legislation, see: R v Bevan [1942] HCA 12; (1942) 66 CLR 452; R v Cox [1945] HCA 18; (1945) 71 CLR 1.

[66] [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 166 CLR 518.

[67] [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 172 CLR 460.

[68] [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 181 CLR 18 (‘Re Tyler’).

[69] See, eg, R v Stow [2005] EWCA Crim 1157; Loving v US, [1996] USSC 48; 517 US 748 (1996); R v Généreux [1992] INSC 17; [1992] 1 SCR 259. See also Eugene Fidell and Dwight Sullivan (eds), Evolving Military Justice (2002); George Prugh, ‘Observations on the Uniform Code of Military Justice: 1954 and 2000’ (2000) 165 Military Law Review 21, 41.

[70] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 13.

[71] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [36, 78].

[72] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [36, 78].

[73] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 166 CLR 518, 570.

[74] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 661 (Deane J).

[75] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 39.

[76] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 42.

[77] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 47.

[78] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 47.

[79] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 54.

[80] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 57.

[81] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 58.

[82] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 663.

[83] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 650.

[84] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 659.

[85] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 661, 663.

[86] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 667.

[87] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 668.

[88] Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 155.

[89] Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 156-7.

[90] Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 160.

[91] Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 167.

[92] Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 166.

[93] Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 162.

[94] Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 163.

[95] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [1].

[96] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [27].

[97] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [3].

[98] Richard Tracey, ‘The Constitution and Military Justice’, (Paper presented at the Annual Public Law Weekend: The Australian Constitution in Troubled Times, Canberra, 8 November 2003) <http://law.anu.edu.au/Cipl/Conferences & SawerLecture/PLW03Tracey.pdf> at 14 August 2005, 16.

[99] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [43].

[100] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [158].

[101] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [89].

[102] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [90].

[103] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [8] (Gleeson CJ), [69] (Gummow J).

[104] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [156].

[105] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [100].

[106] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [8].

[107] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [8].

[108] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [14-16, 44-5].

[109] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [30].

[110] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [40-2].

[111] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [166]. See also [167] (Callinan and Heydon JJ) and [136] (Kirby J}.

[112] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [95].

[113] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [80].

[114] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [140]. See also [150, 153].

[115] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [150].

[116] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [150].

[117] Tracey, above, n 98.

[118] John Devereux, ‘Discipline Abroad: Re Colonel Aird; Ex parte Alpert [2004] UQLawJl 34; (2004) 23 The University of Queensland Law Journal 485, 492. See also Senate Report, above n 1, [5.39].

[119] Andrew Mitchell and Tania Voon, above n 46, 525. See also Andrew Mitchell and Tania Voon, ‘Military justice’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (2001) 481, 482.

[120] See Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [37] (McHugh J); Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 659 (Brennan and Toohey JJ); Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 47 (Deane J), 57 (Gaudron J).

[121] Andrew Mitchell and Tania Voon, above n 46, 525.

[122] Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 166.

[123] Andrew Mitchell and Tania Voon, above, n 46, 515.

[124] Fiona Wheeler, ‘Separation of powers’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (2001) 618, 619.

[125] Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 40.

[126] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [134]. See also [153].

[127] See section IIIA of this article.

[128] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 653.

[129] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 654. This language appears to derive from R v Cox [1945] HCA 18; (1945) 71 CLR 1, 23 (Dixon J).

[130] Re Nolan [1991] HCA 29; (1991) 100 ALR 645, 654.

[131] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [37, 110, 112] (Kirby J), [163] (Callinan and Heydon JJ).

[132] Thus, in applying their test of ‘substantially serving the purpose’, Brennan and Toohey JJ stated that ‘Chapter III has no application to a law creating or conferring the jurisdiction of a court martial’: Re Tyler [1994] HCA 25; (1994) 121 ALR 153, 161. Cf Re Tracey [1989] HCA 12; (1989) 84 ALR 1, 32 (Brennan and Toohey JJ).

[133] See section IIID3 of this article.

[134] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [4] (Gleeson CJ), [39] (McHugh J), [56-7] (Gummow J), [158] (Callinan and Heydon JJ). See also Senate Report, above n 1, [5.39].

[135] Re Aird (2004) 209 ALR 311, [83]. See also [81].