University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

ISSUANCE OF RESIDENTIAL MORTGAGE-BACKED SECURITIES IN AUSTRALIA – LEGAL AND REGULATORY ASPECTS

I INTRODUCTION

In Australia, the term ‘residential mortgage-backed securities’ (‘RMBSs’) denotes debt securities, which are secured, in respect of the principal and interest, on a pool of residential mortgages. A public trustee company specially established solely for this purpose, known as a ‘special purpose vehicle’ (‘SPV’), issues the RMBSs. The issue of debt securities by trustee companies is unique to Australian RMBS programs.1

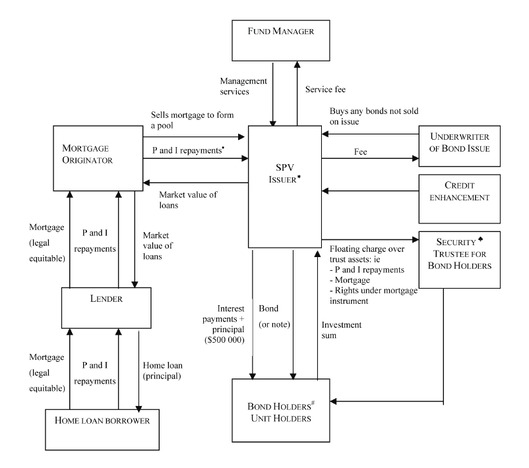

In a typical residential mortgage securitisation program, a housing loan provider, generally referred to as the originating bank or the mortgage originator, ‘pools’ selected housing loans2 and – for a price – transfers its rights under the loan agreements to the trustee. This public trustee company then issues the RMBSs. The RMBSs are typically issued in the form of bonds or notes to investors. These RMBSs are, in practice, invariably characterised as ‘debentures’ for the purpose of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Act’),3 the requirements of which mandate a trust structure for SPVs that issue RMBSs in Australia. The income received by the SPV, from the loan repayments made by the initial housing loan borrowers, acts as a cash inflow against which the trustee‑issuer’s obligations under the RMBS issue are offset. A structure of a typical RMBS program in Australia is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Structure of Typical RMBS Program

‘P and I’ refers to the principal and interest repayments.í Depending on the context, the issuer is also termed the special purpose entity (‘SPE’), SPV, or the trustee.

# Depending on the context, the bondholders are also termed capital unitholders or income unitholders. The bonds themselves are divided into their principal (capital) and income components. The value of each component is further divided into their capital and income units respectively. Usually, there are a number of classes of bondholders, whose rights vary with the class of bonds held. For example, Class A bondholders may have priority rights to interest or capital distributions over Class B bondholders.

♣ The Security Trustee holds a floating charge over trust assets on behalf of the bond/unit holders.

RMBSs first attracted widespread attention in Australia in December 1986, with a $50 million issue by the New South Wales (‘NSW’) government agency First Australian National Mortgage Acceptance Corporation (‘FANMAC’), which was used to purchase residential mortgages originated by cooperative housing societies.4 Since then, the value of the issues of RMBSs has grown considerably, with the amount outstanding in 1996 being $3 billion and reaching a peak of $126 billion in December 2005.5 RMBSs currently account for more than half the value of all asset-backed securities issued in Australia as at 30 June 2006.6 The share of the residential mortgage loans that have been securitised through the issue of RMBSs has increased from 2 per cent to 17 per cent between 1996 and 2005.7 New originators have entered the residential mortgage market with a number of financial institutions and capital market participants keen to establish mortgage securitisation programs.8 From both the investor and originator sides of the market, the advantages of securitisation have been recognised and an exponential growth in the RMBS market has followed.

In Australia, the most significant investors in RMBSs are authorised

deposit-taking institutions (‘ADIs’) and insurance

and

superannuation funds9 seeking short- to long-term debt investments.

These investors are plainly sophisticated in their knowledge of such

investments, relative

to the average small individual investor. Because of their

greater experience and expertise, issuers of securities to sophisticated

investors are not subject to the same onerous disclosure requirements under the

Corporations Act as are issuers of securities to ‘average’

individual investors.10

The issue of RMBSs involves a variety of

legal transactions, and the range of legal and regulatory issues encountered is

profound.

The more important legal and regulatory issues involved in Australian

mortgage securitisation programs include corporate law, trust

law, the

Consumer Credit Code, banking law, bankruptcy law, property law and

contract law.11

The purpose of this article is to examine the

impact of the Corporations Act, the Australian Securities and

Investment Act 2001 (Cth) (‘ASIC Act’), financial

services regulation, and the contractual issues surrounding the issue of RMBSs

in Australia.

Accordingly, the structure of the article is as follows: Part II provides a brief overview of the issuing process of RMBSs. Part III examines corporate law and securities regulation issues, which include the regulation of the RMBS structures, the trust deed, the disclosure requirements in RMBS issues, the misstatements in information memoranda and the licensing of participants in the mortgage securitisation industry. Part IV considers the contractual problems that arise in a RMBS issue, which include notice to mortgagors of the existence of the RMBSs transactions, hedging agreements and the related contractual risks involved in the issue. Finally, Part V provides a summary of the corporate law and other regulatory issues involved in the issue of RMBSs. The article concludes with some suggestions for the reform of corporate legislation in Australia.

II THE ISSUANCE OF RMBSs BY SPVs

A The Bonds Themselves

RMBSs are bonds or notes secured (or ‘collateralised’) by a portfolio of mortgages over residential property.12 The bonds are typically collateralised by a portfolio of security properties held in the mortgage pool, sometimes in addition to contractual ‘debt recourse’ obligations, mortgage insurance, guarantees, or a combination of these risk-reduction methods. Indeed, the bonds are usually over‑collateralised.13 There are a number of reasons for over-collateralising bonds. First, the cash flow from the residential loans accrues first to the originator, and only then to the pool and ultimately to bondholders. Therefore, there is a risk that the balance available from the mortgage pool may not keep pace with the issuer’s obligations in relation to principal and interest payments on the bonds. Second, additional collateral protects bondholders against defaults on individual loans and against any decline in the market value of the security properties between valuation dates. Third, originators typically prefer this arrangement over higher paying yields to investors as compensation for higher default risk and possible depreciation in the value of security properties.

In Australia, RMBSs are typically structured as corporate bonds or commercial paper, with interest paid quarterly or semi-annually at a fixed or variable rate and the principal paid at maturity of the bond facility,14 which is usually after a term of up to 35 years.15 This cash flow structure tends to suit the requirements of institutional investors better, many of whom prefer quarterly or semi-annual payments to the monthly principal and interest payments produced by residential mortgage loans.16

In RMBSs markets overseas, for example in the United States, RMBS programs are either ‘pass-through’ or ‘pay-through’ in character. Pass-through programs comprise issues of debt securities, such as bonds, in which the interest and principal repayments are ‘passed through’ a trust to the investors on a scheduled ‘periodic payment’ basis at about the same time as they are received from the pool of initial borrowers.17 Pay-through issues may be debt securities (for example, bonds) or equity securities (for example, ordinary shares). In the case of bonds, the interest and principal repayments are ‘paid through’ a corporate SPV, not a trust, to the investors on a sometimes scheduled (regular), and sometimes unscheduled (irregular) basis, from the pool of initial borrowers. In the case of shares, the principal and interest repayments made by the initial home loan borrowers are paid to a corporate SPV, which then pays them out again to investors in the form of dividends. These dividend payments may be regular, for example, if the securities issued were preference shares that guarantee investors a regular dividend, or irregular, as in the case of dividends paid to ordinary shareholders. In this latter case, it would be unusual for the investors (ordinary shareholders) to receive their dividend payments at or about the same time as they are received from the pool of borrowers.

Using this terminology, to date there have not been any equity pay-through issues in Australia. All RMBS issues in Australia, thus far, have been debt issues. Most of these have been pass-through programs in the sense described above, although some have had some pay-through characteristics.18 For example, different tranches of securities for different classes of investor are normally reserved for pay-through programs (at least in the United States). The significance of this distinction, in Australia, may be questioned since Macquarie Bank’s RMBS program, the PUMA Fund, is expressed as a pass-through program19 but also provides different tranches of securities.

B The Issuance Process

The process of issuing the RMBSs typically commences with the trustee-issuer authorising a lead manager and/or a co-manager to sell some or all of the bonds in the primary market. The co-manager is usually required to underwrite the entire issue, although both it and the lead manager are involved in the marketing and distribution of the bonds to investors.

Conditions on secondary market sales by initial investors are generally contained in the documentation governing primary market sales. For example, under Macquarie Bank’s PUMA Program, the bondholders are entitled to transfer their bonds in the secondary market subject to the following conditions contained in the Information Memorandum:

After issue, the bonds are uploaded to, or electronically lodged in, the Austraclear system,21 and Austraclear Ltd becomes the registered holder of the bonds.22 In Australia, virtually all RMBSs are issued as registered securities under the Corporations Act.

III REQUIREMENTS UNDER THE CORPORATIONS ACT

All RMBS transactions, whether pass-through or pay-through, are subject to the Corporations Act. The Corporations Act potentially affects RMBS programs in three principal ways:

it regulates participants in the Australian RMBS industry.23 A Regulation of the Structure of RMBSs

RMBS issues can, in theory, be based on equity and debt instruments. An investor in an equity security issued through a residential mortgage-backed securitisation structure holds a beneficial interest in the underlying mortgage pool. Although the instrument may be described as a bond or note, strictly speaking, an investor receives a unit in a unit trust entitling them to a share of the income and capital of the trust assets. The unit is structured to replicate the qualities of a debt instrument. Measures are put in place to ensure that investors receive, on nominated dates, an amount equivalent to interest; that is, a distribution of income, and a repayment of the principal. Under a debt security, the SPV issues instruments known as bonds, notes or commercial paper. Unlike equity securities, investors do not have an ownership interest in the underlying mortgage pool. Instead, they hold a promise by the SPV to pay interest and the principal. This is typically combined with a security interest over the securitised mortgages through a charge given by the SPV to a security trustee for the benefit of investors. Such debt securities can be structured on a pass-through basis and as floating rate or fixed rate securities.

The only equity issue in Australia, to date, has been the FANMAC Trusts issue24 in the early 1990s, which the NSW Government used to fund a highly publicised social housing scheme with fixed rate mortgages for low income borrowers, known as the ‘HomeFund’ scheme.25 One of the principal problems with the early FANMAC Trusts issues was the nature of the underlying asset pool and the residential mortgages to low income earners, in particular the way the loans were marketed to borrowers. The loans provided for low interest rates in the early years of the loans, gradually lifting to higher fixed rates. When borrowers experienced the ‘payment shock’26 as the full rates of interest came into effect, combined with a recession and higher unemployment, there were multiple defaults. Additionally, because the fixed rates were higher than the prevailing interest rates at the end of the concession period, mortgagors began redeeming their loans and switching to normal variable-rate mortgages. The FANMAC pass-through mortgage-backed securities basically passed the prepayment and default risks onto investors. The issue ultimately failed, in part because of lack of servicing capacity on the part of the borrowers under the scheme, and in part because the FANMAC issues limited investors’ rights of recourse to the underlying asset pool. The NSW Government was eventually forced to intervene and compensate both borrowers and investors.27

Perhaps because of the failure of the FANMAC-HomeFund issue, as well as the fact that many institutional investors, such as the Insurance and Superannuation Commission (‘ISC’), favour debt securities over equity securities, whose market yields can be readily compared with those of semi-government note stock for portfolio management purposes,28 all RMBS issues since the late 1980s in Australia have been confined to debt instruments.29

1 RMBSs as Debentures

The debt securities underlying RMBS issues are characterised as ‘debentures’, pursuant to sections 9 and 92 of the Corporations Act. Section 9 of the Corporations Act simply ascribes to the term ‘securities’ the meaning given to it by section 92. Section 92(1) of the Act defines ‘securities’ to include:30

(a) debentures, stocks or bonds issued or proposed to be issued by a government; or shares in, or debentures of, a body; or(b) interests in a managed investment scheme; or

(c) units of such shares; or

(d) an option contract within the meaning of Chapter 7 of the Act.31

In defining ‘debenture’, section 9 aims to focus on the legal right to repayment of the debt, rather than on the piece of paper evidencing the debt. ‘Debenture’ in relation to a body means ‘a chose in action that includes an undertaking by the body to repay as debt money deposited with or lent to the body. The chose in action may (but need not) include a charge over property of the body to secure repayment of the money’.32

The first consequence of this definition is that it specifically excludes a number of fundraising activities. Principal among them, and often used in residential securitisation programs, is an undertaking to pay money under a promissory note that has a face value of at least $50 000. A second exception is an undertaking by a body to repay a loan if made in the ordinary course of a business of the lender, and if the borrower receives the money in the ordinary course of carrying on a business that neither comprises nor forms part of the business of borrowing money and providing finance. These exclusions have had an impact on RMBS issues in practice. Since these issues are not categorised as ‘debentures’, they are not regulated under the Corporations Act, unless they fall within the definition of ‘managed investment scheme’.

The second consequence is that this definition of debenture does not accord with the public’s understanding of the word by providing that a debenture need not be secured by a charge over the body’s property. To rule out the risk that promoters may market their debt instruments legalistically as ‘debentures’ to unsophisticated investors who assume that the instruments are secured when they are not,33 Chapter 2L of the Corporations Act provides a statutory ‘gloss’ or qualification to the broad definition of ‘debenture’ in section 9 of the Act. In particular, section 283BH regulates whether a given debt security is legally allowed to be promoted as a ‘debenture’. Section 283BH(3) prevents a borrower from describing a document evidencing a debt as a ‘debenture’, unless repayment of the money deposited or lent is secured by a charge in favour of the trustee for debenture holders over the tangible property of the borrower. Where the security is a first mortgage over land, the debentures may be described as ‘mortgage debentures’.34 If the loan is unsecured, the document must be described as an ‘unsecured note’ or an ‘unsecured deposit note’.35

Regardless, the bonds issued under RMBS programs could well, and in practice are generally designed to, fall within the ambit of the definition of ‘debenture’ in Chapter 2L of the Corporations Act.36

2 RMBSs and the Managed Investment Scheme Provisions

Prima facie, those debt instruments that cannot be characterised as ‘debentures’ under the Corporations Act fall within the ambit of the Managed Investment Scheme (‘MIS’) provisions in Chapter 5C of the Act.37 These provisions regulate the creation and operation of MISs having at least 20 members, or which are promoted by a person who is in the business of promoting MISs.38 For example, mortgage securitisations based on bills of exchange or promissory notes are prima facie regulated as MISs. All MISs to which Chapter 5C applies must be registered with the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (‘ASIC’).39

Under section 601ED(2), an MIS need not be registered with ASIC if none of the security issues made under the scheme require Product Disclosure Statements to investors.40 This means, for example, that securities in MISs offered to up to 20 persons every 12 months, and which did not raise $2 million or more, need not be registered. Similarly, issues of securities in MISs to investors who do not need disclosure under section 708 of the Act, for example, so-called ‘sophisticated investors’, need not be registered with ASIC.

3 The Trust Deed41

Under section 283AA of the Corporations Act, a company – including, in this context, the corporate trustee of an SPV – offering ‘debentures’ (in practice, this includes RMBSs) to the public for subscription must execute a trust deed, which contains covenants relating to:42

Even if these covenants are not expressly set out in the trust deed, they are implied by statute.45 They relate primarily to undertakings by the borrowing company to use its best endeavours in the conduct of its business, and to provide proper accounting of its activities.

B Disclosure Requirements in RMBS Issues

1 Fundraising

The fundraising provisions affecting the issues of securities were substantially overhauled with the introduction of the Corporate Law Economic Reform Program Act 1999 (Cth) (‘CLERP Act 1999’), which inserted a new Chapter 6D (sections 700 to 741) into the Corporations Act, replacing the previous prospectus provisions.46 These provisions were subsequently revised as a result of amendments made by the Financial Services Reform Act 2001 (Cth) (‘FSRA’).47 The fundraising provisions also regulate investments in ‘securities’. Since debentures are included within the definition of ‘securities’ in sections 700(1) and 71 6A of the Act, RMBSs are clearly regulated by Chapter 6D.48

The Corporations Act requires that any attempt to raise funds by the issue of securities49 be accompanied by a ‘disclosure document’, a copy of which must be lodged with ASIC.50 While ‘disclosure’ itself is not defined, a ‘disclosure document’ for an offer of securities51 is defined in section 9 as:

(a) a prospectus for the offer;(b) a profile statement for the offer; or

(c) an offer information statement for the offer.52

As the section 92 definition of ‘securities’ includes both debentures and MISs, the disclosure provisions of Chapter 6D and Part 7.9 apply to securitisation issues unless a suitable exemption is available. In most cases, the information memoranda used by the mortgage securitisation industry satisfy the criteria for ‘prospectuses’, notwithstanding that many of the industry’s information memoranda are marketed to investors who fall within the ambit of the statutory exemptions from the disclosure requirements under the Act.

2 Content of Disclosure Documents

The form and content of various types of disclosure documents necessary for offers of securities are statutorily prescribed under the Corporations Act. More information must be set out in a prospectus, which is regarded as a full disclosure document, than in the other types of disclosure documents. The Corporations Act imposes a general disclosure test for the contents of a prospectus as well as specific disclosure obligations. Under section 710(1), a prospectus must contain all the information that investors and their professional advisers would reasonably require to make an informed assessment of the matters set out in that section. A prospectus must contain this information only to the extent that it is reasonable for investors and their professional advisers to expect to find such information in the prospectus, and only if the information is actually known, or in the circumstances should reasonably have been known, for example, by making inquiries.

While the general disclosure test in section 710(1) is substantially similar to its predecessor, it was slightly reworded by the CLERP Act 1999 to ensure that information is not included in a prospectus merely because it had been included historically, or was contained in other prospectuses.53 In deciding what information should be included under the general disclosure test, section 710(2) specifies that regard must be had to:

3 Exceptions to Disclosure Requirements

The need for compliance with these disclosure requirements in Chapter 6D means that a RMBS issue involves an expensive, lengthy and fairly inflexible process. Some relief from these comprehensive disclosure requirements is offered by section 708, which sets out a number of situations in which disclosure to prospective investors is not required in respect of security offerings.55 The principal exemptions of relevance to RMBS issues are as follows.

(a) Sophisticated Investors

Sophisticated investors, as defined by section 708(8), are deemed not to need the protection of the disclosure requirements because they are experienced,56 financially sophisticated57 or wealthy investors. Judging from the wording of these provisions of the Corporations Act, Parliament has taken the view that such investors have sufficient means to obtain the relevant information themselves, and that mandating disclosure would be unnecessary.58

(b) Professional Investors

Section 708(11) lists ‘professional’ investment persons and bodies to whom disclosure is not required when making an offer of securities. These include:

(c) Debentures of Certain Bodies

Disclosure is not required in the case of an offer of a company’s debentures where the company is an Australian ADI or registered under the LIA.60 Most residential mortgage securitisation programs in Australia employ structures that come within the ambit of one or more of these exemptions from the Corporations Act’s disclosure requirements. For example, Macquarie Securitisation Limited’s PUMA Master Fund P-1261 provides for ‘Distribution to Professional Investors Only’62 and states that:

This Master Information Memorandum and each Series Supplement has been prepared ... for institutions whose ordinary business includes the buying and selling of securities ... and are not intended for [and] should not be distributed to, ... as an offer or invitation to, any other person.63

The same Information Memorandum provides that

each offer for the issue of ... any offer for the sale of ... the Notes ... under this Master Information Memorandum ... (a) will be for a minimum amount payable on acceptance of the offer ... of at least A$500 000; or (b) does not otherwise require disclosure to a person under Part 6D.2 of the Corporations Act 2001 and is not made to a person who is a Retail Client. Accordingly, neither this Master Information Memorandum nor any Series Supplement is required to be lodged with the Australian Securities and Investment Commission ...64

In a similar vein, Securities Pacific Australia Ltd’s Information Memorandum states that ‘the securities are issued pursuant to a private placement and may only be sold to a person whose ordinary business is to buy or sell securities in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Corporations Act’.65 Likewise, the Information Memorandum of MGICA Securities Ltd states that the securities will be offered only to selected institutions whose ordinary business includes the buying and selling of securities, and that they will not be offered to the public or any section of the public.66

It is not beyond the realms of possibility that, if the market for RMBSs in Australia expands substantially in the foreseeable future, RMBS issues of securities of less than $500 000 could be sold to retail ‘mum and dad’ investors, as distinct from the higher face value securities currently marketed to ‘sophisticated’ institutional investors. If this were to become the case, new provisions in the Corporations Act, or possibly an entirely separate new regulatory regime embodied in ‘stand-alone’ legislation, may become necessary.

4 Misstatements and Omissions in Information Memoranda

Liability for misstatements and omissions in

information memoranda arises both under statute and under the common law, even

if the

securities are marketed by way of information memorandum to investors who

fall within the exemptions from the Corporations Act’s

disclosure requirements.67 In terms of statutory liability, the

CLERP Act 1999 introduced new provisions dealing with liability for

misstatement and omissions in disclosure documents into Part 6D.3 of the

Corporations Act, replacing the previous fundraising liability provisions

in section 996 of the former Corporations Law.

Broadly speaking, Part

6D.3 and Chapter 7 endeavour to ensure that all information pertinent to the

investment decision is disclosed to an investor.68 The two principal

provisions that give effect to that objective are sections 728 and 104 1H of the

Corporations Act, which apply to all disclosure documents.

Section 728 prohibits a securitiser from offering RMBSs under a disclosure

document if it contains a misleading or deceptive statement or omits

information

required by the fundraising provisions.69 The purpose behind the

prohibition in section 728 is to place the responsibility for compliance with

the content-setting rules for disclosure documents directly on the issuer of

securities,

and to make noncompliance actionable at the suit of investors who

suffer loss or damage because of that noncompliance. Contravention

of section

728(1) is a criminal offence if there is a misleading or deceptive statement in

the disclosure document (for example, the information memorandum),

or if the

misstatement or omission in a disclosure document is ‘materially

adverse’,70 from an investor’s point of

view.71 Such an offence carries a maximum penalty of 200 penalty

units, imprisonment for five years, or both.72

The liability

‘net’ is not limited to securitisers. Section 729(1) lists other

people who are potentially liable for misstatements in, or omissions from, the

disclosure documents, including directors

of the issuing body, underwriters and

any person named in the disclosure document.73 Under section 730, a

person referred to in section 729 must notify the person making the offer

‘as soon as practicable’ if they become aware of certain

deficiencies in the

disclosure document or a ‘material new

circumstance’ has arisen.74

The other principal section of the Corporations Act by which

Parliament seeks to ensure that all relevant information is disclosed to

investors is section 1041H, which operates as a ‘catch all’

provision. Other statutory provisions which give rise to civil liability in

relation

to defective information memoranda are section 12DA of the ASIC Act

and, if neither sections 1041H or 12DA apply, section 52 of the Trade

Practice Act 1974 (‘TPA’). Both sections 1041H and 12DA

are based on section 52 of the TPA.75

Section 1041H

provides that ‘a person must not ... engage in conduct, in relation to a

financial product or a financial service,

that is misleading or deceptive or is

likely to mislead or deceive’. Section 1041H(2) relates to the publication

of notices

(for example, advertisements) and to negotiations and arrangements

preparatory to or related to an issue of RMBSs.76 The section imposes

strict liability, so that it applies even where no disclosure document has been

lodged with ASIC, for example,

when one of the section 708 exemptions applies.

77

Section 1 2DA of the ASIC Act prohibits a person from engaging in

misleading or deceptive conduct in trade or commerce in relation to financial

services. It is

likely that almost every information memorandum used in RMBS

programs could be regarded as being ‘in relation to financial

services’ for the purpose of attracting the application of section 1 2DA.

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Financial Services

Reform Bill 1998 (Cth)

provides that the purpose of section 1 2DA is to replicate the TPA

’s consumer protection provisions in the ASIC

Act.78 Although this section appears in a division headed

‘Consumer Protection’, it is not limited to consumer protection, and

it also applies to both the wholesale and retail security

markets.79

The result is that two prohibitions – those in

sections 1041H of the Corporations Act and 12DA of the ASIC Act

– apply to an information memorandum in RMBS programs. Why this

duplication was considered necessary remains unclear, particularly as

both

sections were drafted in almost identical terms.

The terms ‘misleading

conduct’ and ‘deceptive conduct’ are not defined in the

Corporations Act or the ASIC Act. However, these concepts have, in

effect, created their own jurisprudence, particularly in the area of trade

practices. Since sections

1041H and 12DA are modelled on section 52 of the

TPA, it seems likely that the courts’ interpretation of these

concepts in the context of section 52 is applicable to them.80 For

instance, the term ‘likely to mislead or deceive’ has been

judicially defined in relation to section 52 of the TPA to mean ‘a

real and not remote chance of misleading or deceiving’.81 In

ASC v Nomura International Plc,82 the same meaning was

held to apply to that term in section 995 (the predecessor of section

1041H).83 It is also clear from the policy behind the introduction of

section 1 2DA that it is intended to cover, in relation to financial

services,

the same conduct as section 52.84 This means that, like section 52,

whether conduct is misleading or deceptive in a disclosure document or

information memorandum will

be determined objectively in the circumstances of

the case.85 An intention to mislead or deceive is irrelevant. An

issuer of RMBSs can, therefore, breach sections 12DA and 1041H

inadvertently.86

Silence on an issue of securities will be considered misleading or deceptive if the facts give rise to a reasonable expectation that the matter would have been disclosed.87 For example, in Fraser v NRMA Holdings Ltd,88 the Full Court examined whether an omission from a disclosure document constitutes a breach of section 52:

Where the contravention of s[ection] 52 alleged involves a failure to make a full and fair disclosure of information, the applicant carries the onus of establishing how or in what manner that which was said involved error or how that which was left unsaid had the potential to mislead or deceive. Errors and omissions to have that potential must be relevant to the topic about which it is said that the respondents’ conduct is likely to mislead or deceive.89

It is arguable, therefore, that because issuers of RMBSs are under an obligation, under section 728(1), to disclose all information, a failure to do so could constitute misleading or deceptive conduct for the purpose of sections 1041H and 12DA. Thus, whether an omission from an information memorandum constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct will depend on whether an investor in the target ‘audience’ had a ‘reasonable expectation’ that the omitted material would be disclosed. Accordingly, the information that an investor would expect to be disclosed in an information memorandum is similar to that set out in sections 710(1) and 710(2) of the Corporations Act for a prospectus – that is, all information that an investor would reasonably require and reasonably expect for the purpose of making an informed assessment of the issuer and the relevant securities. Where it is alleged that an issuer or fund manager did not disclose a vital piece of information in an information memoranda, investors have an incentive to plead sections 1041H, 12DA and 728(1) in the alternative.

Sections 1041I of the Corporations Act and 1 2GF of the ASIC Act impose civil liability on the person whose ‘conduct’ constituted the contravention and on any other person ‘involved in the contravention’.90 A contravention of section 12DA does not constitute an offence.91 However, persons aggrieved can claim for their loss by way of civil action pursuant to section 12GF of the ASIC Act. These remedies are similar to those in TPA for a breach of section 52.92 Similarly, section 1311 of the Corporations Act specifically provides that a breach of section 1041H is not an offence. Instead, the consequence of a breach is potential civil liability, under section 1041I of the Corporations Act, which is also based on section 82 of TPA. Section 52 of the Corporations Act also provides that ‘a reference to doing an act ... includes a reference to causing, permitting or authorising the act or thing to be done’. In other words, a party who authorises the issue of an information memorandum will probably be deemed to have engaged in the relevant conduct to the extent that the information memorandum comprises any misleading or deceptive conduct. Usually, this will be the fund manager or sponsor of the securitisation program.93

5 Defences

There are two main defences available to persons against whom civil or criminal liability under sections 729 or 728(3) of the Corporations Act is alleged. These are the so-called ‘due diligence’ and ‘reasonable reliance’ defences.

(a) The ‘Due Diligence’ Defence

In the case of materially adverse misstatements and omissions appearing in a prospectus, a person does not commit an offence against section 728(3) and is not liable under section 729 for loss or damage due to contravention, if the person proves, under section 731, that he or she:

The ‘due diligence’ defence in section 731 applies only in relation to prospectuses, not to all disclosure documents. However, there is little doubt, based on the foregoing argument, that, in appropriate circumstances, the defence could be available in respect of information memoranda in RMBS issues, provided the due diligence has taken place in a bona fide fashion.97

(b) The ‘Reasonable Reliance’ Defence

Section 733(1) of the Corporations Act provides the persons responsible for misleading or deceptive statements or omissions in disclosure documents with a defence if they reasonably relied on information given to them by others,98 or if the document becomes misleading or deceptive because of new circumstances of which they were unaware.

Section 733(2) recognises that, when disclosure documents are prepared, much of the information they contain is likely to come from outside experts and professional advisers.99 Such information includes the program parameters; the terms and conditions of each bond issue; and the procedures, guidelines and lending criteria for the residential housing loans that form part of the mortgage pool. As a matter of policy, it seems reasonable that the issuer should be able to rely on the expertise of external experts and professional advisers, since this is why professional advisers are engaged in the first place.

The ‘reliance’, which the SPV and fund managers place on others for the purposes of section 733, must be reasonable. This is an objective test, and is gauged against what other people would do when placed in similar circumstances. In the United States context, the Court, in Rovell v American National Bank,100 held that ‘reasonable reliance’ was driven by the facts of each case. The Australian courts have been more specific. For example, in interpreting the ‘reasonable reliance’ defence in section 85(1)(b) of the Australian TPA, the Court in, Gilmore v Poole-Blunden,101 pointed out that the defence was available where an issuer relied on legal opinion given by counsel, which can be ‘information’ for the purposes of the defence. Certainly, from a legal risk management perspective, the usual strategy adopted by Australian securitisers is to seek legal and other professional advice concerning compliance with the fundraising regime, and to sue those advisers if the advice turns out in hindsight to have been negligent.102

The ‘due diligence’ and ‘reasonable reliance’ defences make it clear that if an issuer and its officers in a RMBS program are to avoid criminal or civil liability for potential breaches of Chapter 6D, they must show that they have been sufficiently, or duly, diligent in ensuring that all information disclosed in an information memorandum is up-to-date and accurate, and that it contains all information relevant to an investor for making an informed decision about whether or not to invest in those particular mortgage-backed securities.

6 Liability at Common Law

As noted earlier, the common law also provides investors with rights where they have been misled or deceived by a prospectus. Common law liability in this context is primarily fault-based, allowing damages for deceit or negligent misrepresentation.103 Financial advisers and independent experts have been held to owe a duty of care to those who retain them, and, consequently, to be liable for reasonably foreseeable losses resulting from negligent preparation of their reports.104 Nevertheless, any misrepresentation that becomes a term of a contract gives rise, in a sense, to strict liability.105 The remedy of rescission is also generally available where an SPV which, even without fault on its own part, issues a misleading prospectus.

7 Suitability of Sections 12DA and 1041H for Mortgage Securitisations

From a law reform perspective, an interesting question arises as to whether the Corporations Act itself advantages investors in RMBSs, relative to investors in other corporate securities, who wish to sue the SPV or its agents (for example, the fund manager) on the basis that they were induced to invest because of false or misleading information memoranda.

Under the current legislation, if investors in other corporate securities sue under sections 728 and 729 for loss because of a misleading or deceptive statement in a disclosure document, their claim can be defeated if the defendant can prove the defences in sections 731 to 733.106 However, liability under sections 12DA and 1041H is strict, so that an investor’s claims in relation to a misleading information memorandum would not be able to be met by any defences.107 This is despite the fact that most investors in RMBS issues are so-called ‘sophisticated investors’, for the purposes of the disclosure provisions. This implies that sophisticated investors in the RMBS markets have greater likelihood of recovery than investors in other corporate securities in the financial markets.

C The Regulation of Participants

The 1997 Wallis Committee Report of the Financial

System Inquiry (‘FSI’)108

observed a number of key

factors impacting on the financial system in Australia.109 Following

the release of CLERP 6, relating to financial services reform, the FSRA

was implemented in 2001. The FSRA replaced Chapters 7 and 8 of the

Corporations Act with a new Chapter 7, as well as implementing some

related amendments.

It might be thought that trustee-issuers of RMBSs are required, under the legislation, to obtain an Australian Financial Services Licence (‘AFSL’)110 in order to market their bonds. Certainly, the prerequisites to a licence requirement, under Chapter 7, are satisfied. First, RMBSs are plainly ‘financial products’111 because they are debentures and debentures are financial products.112 Second, the issuers of RMBSs are clearly providing ‘financial services’113 because they provide financial product advice,114 deal in financial products115 and the transaction involves the provision of a custodial or depository service.116 However, Chapter 7 of the Corporations Act does not trespass on other prudential regulation of financial products and services. Section 91 1A(2)(g) specifically exempts providers and services marketed only to wholesale clients,117 regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (‘APRA’), from the need to hold an AFSL. As noted earlier, the issuers and other providers of RMBSs meet these requirements;118 therefore, there is no need for them to hold an AFSL.

A related issue is whether banks or other financial institutions that engage in hedging activities, for example, providing interest rate swaps to assist the fund manager with the risk management aspects of RMBSs, are also required to hold an AFSL. Again, by a similar process of reasoning, because these providers and their wholesale activities are regulated by APRA and, in practice, market RMBSs only to professional investors, they would appear to be exempted by sections 761G and 91 1A(2)(g) from the need to hold an AFSL.

IV CONTRACTUAL CONSIDERATIONS

A housing loan is, at its most fundamental level, a contract between lender and borrower. From a perspective not only of (social) economic efficiency in neoclassical microeconomic theory, but also of ethical theory, transparency and informed choice in contracting are generally regarded as desirable, at least to the point where the benefits of additional information equal the costs at the relevant margin.119

In general, the law also reflects this stance. For example, Kirby P, in Canham v Australian Guarantee Corporation Ltd,120 highlighted the importance of borrowers making informed decisions when assessing loan contracts:

The ultimate theory behind the philosophy of truth in lending ... is that disclosure ... will help to ensure honesty and integrity in the relationship (where one party is normally disadvantaged or even vulnerable); promote informed choices by consumers; and allow the market for financial services to operate effectively.121

A Notice to Borrowers

Almost 50 years ago, admittedly in the context of exclusion clauses, the courts propounded the fundamental principle that the more unreasonable a clause, the greater the notice which must be given of it. Lord Justice Denning, in the English Court of Appeal, expressed the principle eloquently in a well-known dictum, observing that ‘some clauses, which I have seen, would need to be printed in red ink on the face of the document, with a red hand pointing to it before the notice could be held to be sufficient’.122 It seems difficult to argue convincingly that this principle should not apply equally to bringing the risks of securitisation to the attention of home loan borrowers today. Securitisation via RMBS programs involves the risk that borrowers might find their homes sold by downstream financial intermediaries who have ‘purchased’ their bank’s or independent mortgage provider’s (‘IMP’s’)123 mortgagee rights. This is not because of a failure to pay on the part of the borrowers, but as a result of some act or omission by one of the financial intermediaries in the supply chain or the insolvency of the intermediary.124 This begs the question of whether most home loan borrowers are aware of this risk at the time of taking out their loans. Experience would indicate that most are not, nor is it specifically brought to their attention.

From a bank’s or IMP’s point of view, the loan contract invariably states, albeit in fine print amongst many thousands of words, that the housing loan may be assigned. Typically, the clause in most contemporary mortgage documents is to the effect that the bank or IMP ‘may assign or otherwise deal with [its] rights under this mortgage or any secured agreement in any way [it] considers appropriate’. 125 If the banks are to take mortgage security over residential properties, they can and should be expected to explain, at least, the major clauses in their mortgage documents to borrowers. The deceptively simple assignment clause is certainly one with potentially major consequences for borrowers as the law now stands. So that they can make an informed decision about their choice of financier, most borrowers would wish to be made aware – and, indeed would expect to their banks to tell them – of any risk that they could lose their homes, whether through mortgage assignment or any other cause. On the other hand, the banks and IMPs would rely on such clauses to avoid liability in the event of proceedings instituted by borrowers for loss of their homes, in the same way as other commercial firms seek to rely on exclusion clauses in their contracts. Such clauses are generally construed against the interests of the persons who drafted the clause (contra proferentum), with the proferens (in this context, the originating bank or assignor) being required to take reasonable steps to give notice of the existence and contents of the clause to those against whom it is intended to be used. In practice, this generally means that the clause must be presented clearly and unambiguously, in such a way that a reasonable person would become aware of it126 and realise that it could have an impact on his or her rights and liabilities under the contract.127 The steps that are reasonably required to bring the clause to the attention of the other party (in this context, the mortgagor) must be taken before or at the time the contract is entered into. A clause brought to the attention of a party after the contract has been entered into will not be effective.128

Banks can and should advise their customers to obtain independent legal advice about the effects of clauses in their mortgage documents. The problem with banks relying completely on advising customers to obtain independent legal advice is that currently, in practice, solicitors are not commenting on assignment programs in mortgages because they do not fully understand them, and sometimes have continuing conflicts of interest from acting on behalf of banks or other parties in past transactions.

Even if these communication mechanisms are pursued, the mere fact that a loan agreement contains a clause to the effect that the loan may be assigned is surely not a basis for an informed choice on the part of the borrower about the consequences of assignment, if the risks are not communicated to the borrower.

The risk that the banks and IMPs run, if they do not bring the risks of their participation in RMBS programs to the attention of home loan borrowers, is that they could ultimately face a wave of litigation similar to that precipitated by the foreign currency loan scandals of the mid-to-late 1980s.129 In essence, all of that litigation arose, not from the complicated nature of the (then) ‘novel’ financing arrangements, but from the banks’ failures to notify borrowers of the risks involved. In those cases, the risk was that borrowers could ultimately have their mortgaged properties sold not through any conscious default on their part, but because of adverse exchange rate fluctuations over which they had no control.130

The banks’ exposure in the late 1980s was increased by the fact that many (and perhaps most) of their own managers and loan officers were unaware of the consequences of currency fluctuations, and so could not, even if they had wished to, have informed borrowers of the risks. In a similar vein today, experience suggests that many (and, again, perhaps most) bank managers and loans officers are just as unaware of the risks inherent in RMBS transactions now and the consequences for borrowers, as their counterparts were in regard to the risks to foreign currency loan borrowers in the mid-to-late 1980s.

The precedents provided by the foreign currency loan cases of the early 1990s131 may provide some protection for housing loan borrowers facing the risk of losing their homes because of the risks inherent in today’s RMBS transactions. These cases reaffirm that the banks and IMPs plainly owe their customers a duty to exercise reasonable skill in fulfilling their obligations under the loan contract.132

Furthermore, if they adopt novel financing arrangements that may impact on the borrower, the banks and IMPs may have a duty to explain the technical aspects of the arrangements to their borrowers;133 however, this is by no means certain, and probably depends on the circumstances,134 for example, whether the customer is even likely to understand the explanation given. If they were to give an explanation or advice, the banks and IMPs would of course need to exercise reasonable care and skill in giving that explanation or advice.135

Having said this, it is likely that the past cases could be easily distinguished in the event of litigation over RMBS programs, precisely because they involved foreign currency risk, rather than other risks to borrowers in RMBS transactions.

The risk to housing loan borrowers that they might lose their homes through no fault of their own; the uncertainty of whether, at common law, the banks and IMPs even owe a duty to explain that risk and other technical aspects of RMBSs to their home loan borrowers; and the risk that many, or even most, bank managers, loans officers and independent lawyers are themselves unaware of that risk, are compounded by the fact that, at present, there is no specific legislation requiring the banks or IMPs to bring those risks to the attention of home loan borrowers. While it is true that borrowers may be protected by section 52 of the Trade Practices Act, and equivalent provisions in the Corporations Act, this is by no means clear and unequivocal.136 In the longer term, there remains the risk of moral hazard, and appropriate regulation may be needed to correct this.

B Hedging Agreements137

In a RMBS program, the interest component of the mortgage loan repayments received by the trustee-issuer may be based on a fixed or a variable interest rate. A mismatch will arise if either:

(a) variable rate home loan interest is received, but the interest payable on the bonds is at a fixed rate; or(b) fixed rate home loan interest is received, but the interest payable on the bonds is at a variable rate; or

(c) there is a timing mismatch between the cash flows received and the cash flows payable (for example, if the home loan repayments are received on a monthly basis, but the bond interest is payable semi-annually).

In order to manage the financial risks inherent in such mismatches, the trustee (or more usually, its fund manager) will enter into hedging agreements, such as interest rate futures and options, and interest rate swap contracts.138 In effect, interest rate futures fix a variable rate, so that the fund manager knows precisely what rate it earns or must pay; interest rate options give the fund manager the option to fix the interest rate if it chooses; and interest rate swap contracts enable variable rate interest to be converted to fixed rate interest, or fixed rate interest to be converted to variable rate interest.139

It might be thought that notice should be given to home loan borrowers, not only that their loans may be assigned to SPVs as part of a RMBS transaction, but that those SPVs will almost certainly use financial derivatives, such as futures, options and swaps, to manage some of the risks involved. However, there is a fundamental point of difference between the two types of notice. The argument in favour of notifying home loan borrowers that the assignees of their housing loans will almost certainly use financial derivatives to help manage the risks involved is a moot one: if hedging agreements are properly managed, there is no risk to home loan borrowers of losing their homes, through no fault of their own. That risk will generally arise for other reasons. On the other hand, if the fund managers do not properly manage their hedging arrangements,140 there are already well-established causes of action, such as negligence, of which aggrieved bondholders can avail themselves.

V CONCLUSION – TOWARDS A NEW REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

Since the 1980s, RMBS issues have increased in usage, but have been mostly confined to debt instruments. This is a result of the FANMAC-HomeFind failure in the late 1980s141 and the higher market yields received by these types of issues. These debt instruments may be characterised as debentures under the Corporations Act.142 This means that the parts of the Act that regulate debentures also regulate the issue of RMBSs. One form of regulation in the Act is through the requirement that companies (including banks) that offer ‘debentures’ such as RMBSs to the public for subscription must do so within the framework of a trust, and SPVs in Australia invariably operate as trusts in practice. Debt instruments that cannot be characterised as ‘debentures’ under the Corporations Act automatically fall within the ambit of the MIS provisions of the Act.

Issuing debt instruments that are structured as ‘debentures’

saves transaction costs. It is true that the SPV incurs the

costs of complying

with the reporting, record keeping and other requirements pursuant to Chapter 2L

of the Corporations Act,143 subject to a right of indemnity

from the trust assets, and that these costs will be reflected in the pricing of

the overall transaction.

However, those costs are significantly less, across all

stakeholders in the issue than the regulatory compliance costs that would

result

if the underlying securities were subject to the MIS provisions. Furthermore,

the underlying debt securities in virtually

all RMBS issues in practice are

generally exempt from the disclosure requirements in Part 6D.2 of the

Corporations Act because they are sold only to institutional and other

‘sophisticated’ investors under section 708(8) of the Act. This

also

saves transactions costs across all stakeholders in the issue. Therefore, from a

private or self-interest perspective, the incentives

to structure the issue as

‘debentures’ under the Corporations Act are understandable

because they ultimately result in lower transactions costs across all

participants in the issue.

However, this begs the question of whether,

because of the current wording of the Corporations Act, some RMBS issues

that are currently structured as ‘debentures’ to minimise regulatory

compliance costs should, from a

public interest perspective, be subject to more

or different regulation in order to protect investors and creditors. This is

particularly

so as the market develops and financiers find it profitable to

market RMBS issues, comprising securities of less than $500 000, to

retail

investors, as distinct from the higher value securities presently marketed to

‘sophisticated’ institutional investors.144 If the RMBSs

are offered to retail markets, the issuers are likely to encounter difficulties

particularly in relation to Chapter

5C (interest in MIS schemes), which involves

significant regulatory compliance costs.

If or when the market develops to this extent, it is likely that, at some

point in the foreseeable future, the timing of which will

depend on economic and

political considerations, regulation of the market may need to be

amended.

Currently, the Corporations Act and the ASIC Act

impose substantial civil consequences on fund managers and others

responsible for the preparation of a defective information memorandum.

However,

there may sometimes be a ‘fine line’ in practice between mere

puffery145 and running foul of the ‘misleading or deceptive

conduct’ provisions in sections 728 and 1041H the Act, and sections

12DA

and 52 of the ASIC Act and TPA respectively.

Moreover, liability under sections 12DA and 1041H is strict. Defences, such as due diligence under section 733, are not applicable to issuers who prepare information memoranda in RMBS programs. This means that lack of a due diligence defence under sections 12DA and 1041H provides sophisticated investors with greater rights of recovery than retail clients. This raises questions about the fairness and effectiveness of current legislative mechanisms.

A question also arises about the strength of these legislative mechanisms, first because the protection that the legislation affords is not clear nor unequivocal, and second because the legislation does not prevent the risk that a borrower’s home may be sold by downstream financial intermediaries, without notice to the borrower. This begs the question of whether most home loan borrowers are aware of this risk at the time of taking out their loans. Experience would indicate that most are not, nor is it specifically brought to their attention. This is compounded by the fact that borrowers could then face excessive litigation, similar to the wave of cases concerning the foreign currency scandals in the 1980s.

In light of this regulatory landscape, the Corporations Act could be amended to include new provisions, or possibly a separate regime, dealing with RMBS issues of securities of less than $500 000 sold to retail investors, as distinct from the regimes for debentures and MISs. Such a regime, based on the US model, found in the Investment Company Act of 1940,146 would be an appropriate method for the Australian RMBS programs.147

Endnotes

* BCom (Honours); Attorney-at-Law; MA (Econ) (Waterloo); LLM (Monash); PhD (Law) (Griffith); Lecturer in Commercial Law, Griffith Business School, Griffith University, Brisbane, Queensland. This article is based on my PhD Thesis, Residential Mortgage Securitisation in Australia: Suggestions for Reform of Commercial Law and Practice (PhD Thesis, Griffith University, 2005). I wish to acknowledge the valuable comments provided by Dr Richard Copp, Barrister-at-Law, Inns of Court, Brisbane; Associate Professor Justin Malbon, Faculty of Law, Griffith University; Professor Tamar Frankel, Boston University School of Law; Professor Berna Collier, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission; and Dr Eduardo Roca, Deputy Head, Department of Accounting, Finance and Economics, Griffith Business School.

3 See Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 9, 92. Debt instruments that cannot be characterised as ‘debentures’ under the Act automatically fall within the ambit of the managed investment scheme (‘MIS’) provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Act’).

4 Bankers Trust, ‘Securitisation in Australia’ (May 1999) Asiamoney 17; Stephen Lumpkin, ‘Trends and Developments in Securitisation’ (1999) 74 Financial Market Trends 1; Edna Carew, Fast Money 4: The Bestselling Guide to Australia’s Financial Markets (1998) 201.

9 Standard and Poor’s, RMBS, CDO Activity Lead Australian Securitisation Issuance Growth in 2003 – Credit Ratings and Commentary (2003) 5 <http://www2.standardandpoors.com/servlet/Satellite?pagename=sp/Page/FixedIncomeBrowse> (copy on file with author).

10 For example, Macquarie Bank Limited’s residential mortgage-backed fund, the PUMA Fund, offers bonds to professional investors. This means the trustee of the Fund does not need to comply with the disclosure provisions relating to investors under Pt 6D.2 of the Corporations Act: Macquarie Securitisation Limited et al, The PUMA Program – Principal and Interest Notes: PUMA Master Fund P-12 – Master Information Memorandum (2006) ASX 3 <http://www.asx.com.au/asxpdf/20060619/pdf/3x6jj37v3v9hh.pdf> at 22 October 2006 (‘PUMA Fund’).

12 By way of example, Macquarie Bank Limited’s PUMA Fund operates one of the largest residential mortgage-backed programs in Australia: see Mark B Johnson, ‘Oz Securitisation Gathers Pace’ (March 2001) Asiamoney 47, 48.

14 See Frank J Fabozzi (ed), The Handbook of Mortgage-Backed Securities (4th ed, 1995) ch 16.

15 See, eg, PUMA Fund, above n 10, 73.

16 The payment of principal and interest on the bonds themselves is not dependent upon the cash flow of the underlying loan assets. Housing loan repayments typically comprise of principal and interest (to reduce the risk of borrowers’ default), but such payments are said to be inconvenient for institutional investors, since the capital and income components of the repayments must be separated for different tax treatments, and the frequency of repayments does not generally match the frequency of payments under the trustee‑issuer’s own obligations to investors: see Frank J Fabozzi, ‘Mortgages’, in Fabozzi (ed), above n 14, 3, 9– 10.

If this definition were accepted in Australia, most RMBSs would be classified as ‘securities’ for the purpose of the fundraising provisions of Ch 6D of the Corporations Act. However, the manner and extent to which the Corporations Act applies depends on the characteristics of the debt instruments and the underlying assets.

32 For readers without a legal background, a ‘chose in action’ is a right that is enforceable by legal action.

33 Debentures are generally understood to mean documents that acknowledge or create a debt owed by the company that issues them: Levy v Abercorris Slate and Slab Co [1887] UKLawRpCh 200; (1887) 37 Ch D 260, 264 (Chitty J). See also Roman Tomasic, James Jackson and Robin Woellner, Corporations Law: Principles, Policy and Process (4th, ed 2002) 612S. At common law, it is clear that there is no unanimity on the definition of a debenture. The traditional view was that to be a debenture a document would have to acknowledge or evidence an existing specific debt as distinct from providing security for a debt or an acknowledgment of general indebtedness: Burns Philp Trustee Co Ltd v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (NSW) (1983) 83 ATC 4477; Handevel Pty Ltd v Comptroller of Stamps (Vic) [1985] HCA 73; (1985) 157 CLR 177, 195–6. Historically, the expression ‘debenture’ has applied not to the indebtedness but to the paper, which is the evidence of the debt: this was certainly the meaning in the previous Corporations Law (Cth) (‘Corporations Law’). In Broad v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (NSW) [1980] 2 NSWLR 40, Lee J held that debenture for the purpose of NSW loan security duty provisions only applies to debentures issued by bodies corporate and, hence, does not apply to securities given by an individual, as was the situation in that case. In Handevel Pty Ltd v Comptroller of Stamps (Vic) [1985] HCA 73; (1985) 157 CLR 177, 199–200, the High Court accepted that one essential characteristic of a debenture is that ‘it is issued by a company’. It has been held, in a stamp duty context, that a debenture differs from a mortgage in that there is no need for any charge on any property to be contained in it: British India Steam Navigation Co v IRC [1881] UKLawRpKQB 40; (1881) 7 QBD 165, 172; Lemon v Austin Friars Trust Ltd [1926] Ch 1; Edmonds v Blaina Furnaces Co [1887] UKLawRpCh 133; (1887) 36 Ch D 215, 219; Re Shipman Boxboards Ltd [1942] 2 DLR 781; Handevel Pty Ltd v Comptroller of Stamps (Vic) [1985] HCA 73; (1985) 157 CLR 177.

36 See, eg, the notes issued as RMBSs by Macquarie Securitisation Limited in the PUMA Fund, above n 10, 67–73.

37 The MIS is a statutory creation originally derived from the recommendations of the English Anderson Committee on Fixed Trusts and the current legislation is based on those recommendations: see Board of Trade Committee on Fixed Trusts, Parliament of Great Britain, Fixed Trusts: Report of the Departmental Committee Appointed by the Board of Trade (1936); Prevention of Fraud (Investments) Act 1939, 2 & 3 Geo 6, c 16. The concept has been refined and developed over time by successive legislative amendments so that s 9 of the Corporations Act now provides that a MIS includes the following features:

benefits produced by the scheme.

The definition of a MIS is extremely wide, to a degree which is ‘barbarous’ according to Jones J, in WA Pines Pty Ltd v Hamiltion [1981] WAR 225, commenting on the definition of ‘prescribed interest’. See also Australian Softwood Forests Pty Ltd v A-G (NSW) ex rel Corporate Afairs Commission [1981] HCA 49; (1981) 148 CLR 121 (Mason J). Many forms of securitisation are likely to consitute MISs for the purposes of the Corporations Act. For example, a unit in a unit trust constitutes a ‘managed investment’ for the purposes of the Corporations Act: see A-G (NSW) v Australian Fixed Trusts [1974] 1 NSWLR 110.

42 See Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) Ch 2L, ss 283DA–283DC.

59 In relation to the professional investor exemption, a caution needs to be sounded. An issuer of securitised debt instruments could inadvertently breach the disclosure provisions of Ch 6D if it offers securities to an investor who appears, or purports, to satisfy the requirements contained in s 708(11), but who in fact does not. In these circumstances, the issuer will not be entitled to the exclusion in this section because the benefit of it is not based on the investor satisfying the requirement. The investor and its associates must, in fact, control not less than $10 million in investments. If the investor does not, then the issuer of the RMBSs could be liable for failing to lodge its disclosure documents with ASIC in accordance with s 727(1) of the Corporations Act. Contravention of s 727 is a criminal offence punishable by a fine of $20 000 or five years imprisonment or both: Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 1311, sch 3.

61 See PUMA Fund, above n 10.

The term material, when used to qualify a requirement for the furnishing of information as to any subject, limits the information required to those matters to which there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would attach importance in determining whether to purchase the security registered: General Rules and Regulations, Securities Act of 1933 17 CFR § 230.405(1) (1968). See CCH, Australian Corporations Commentary (Fundraising: Prohibitions Restrictions and Liabilities – Misleading or Deceptive Statements and Omissions: Obligations to Notify in Relation to Deficiencies Disclosure Document) 202-500.

These provisions have a similar operation to the provisions in Ch 6D of the Corporations Act. For example, s 728 of the Corporations Act is based on s 11(a) of the Securities Act of 1933, which provides as follows:

in case any part of the registration statement ... omitted to state a material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading, the person acquiring such security (unless it is proved that at the time of such acquisition he knew of such untruth or omission) may, either at law or in equity, in any court of competent jurisdiction, sue: CCH, Australian Corporations Commentary, 202-500.

Section 728 provides that an omission, which should have been included in the disclosure document, under ss 710 to 715, is not to be misleading. Section 728(1) provides direct guidance as to the nature of the matters that need to be disclosed in order for issuers to satisfy the disclosure requirements. The current Australian provision is, therefore, potentially less limited in its application than its counterpart in the US.

75 Cleary v Australian Cooperative Foods Ltd [1999] NSWSC 973; (1999) 32 ACSR 582; Explanatory Memorandum, Financial Sector Reform Bill 1998 (Cth) [4.12]. For a detailed discussion, see Brian Salter, ‘Civil Liability for Errors and Omissions in Information Memoranda in Wholesale Debt Capital Markets’ (2003) 14 Journal of Banking and Finance Law and Practice 61.

engaging in conduct in relation to a financial product includes (but is not limited to) any of the following:(a) dealing in a financial product;

(b) without limiting paragraph (a) –

(i) issuing a financial product;(ii) publishing a notice in relation to a financial product.

78 Section 51AF of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (‘TPA’) provides an exemption to the operation of s 52. Under s 51AF, s 52 does not apply to a supply or services that are ‘financial services’ and to conduct in relation to ‘financial services’.

80 The relevance of s 52 case law to the former s 995 of the Corporations Act was recognised in Fame Decorator Agencies Pty Ltd v Jefries Industries Ltd [1998] FCA 775; (1998) 16 ACLC 1, 235; Fraser v NRMA Holdings Ltd (1995) 55 FCR 452; Colin Lockhart, The Law of Misleading and Deceptive Conduct (1998); Donna Croker, Prospectus Liability under the Corporations Act (1998) ch 8.

81 Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82, 87–8.

83 See also Winpar Holdings Ltd v Goldfields Kalgoorlie Ltd [2000] NSWSC 728; (2000) 176 ALR 86, 8 8–9.

85 In Nat West Australia Bank Ltd v Tricontinental Corporation Ltd (1993) 46 ATPR (Digest) 109, the Court identified several factors that may be taken into account in determining whether an omission from an information memorandum constitutes a breach of ss 12DA and 1 041H:

A similar approach was also adopted by the Full Court in a later case of Fraser v NRMA Holdings Ltd (1995) 55 FCR 452.

86 See generally Annand and Thompson Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission [1979] FCA 36; (1979) 25 ALR 91, 101–2; Sterling v Trade Practices Commission [1928] ArgusLawRp 119; (1981) 35 ALR 59, 64–6; Handley v Snoid (1981) ATPR 40-219.

87 Warner v Elders Rural Finance Ltd [1993] FCA 117; (1993) 41 FCR 399; Demagogue Pty Ltd v Ramensky [1992] FCA 557; (1992) 39 FCR 31, 32.

89 Ibid 467–8. See also NRMA Ltd v Morgan [1999] NSWSC 407; (1999) 17 ACLC 1029, 1045; Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Mehta (1991) 23 NSWLR 84; Warner v Elders Rural Finance Ltd [1993] FCA 117; (1993) 41 FCR 399; Demagogue Pty Ltd v Ramensky [1992] FCA 557; (1992) 39 FCR 31.

90 Sections 79 of the Corporations Act and 12GF of the ASIC Act comprehensively explain what is meant by being ‘involved in the contravention’. These sections are based on s 75B of TPA and provide substantially the same terms.

93 See, eg, PUMA Fund, above n 10, 1–2.

The text of s 731 is quite different from the former ‘due diligence’ defence under s 1011 of the former Corporations Law. The former s 1011 provided that

a person who authorised ... the issue of prospectus is not liable ... if it is proved that the false or misleading statement or omission (a) was due to a reasonable mistake; (b) was due to a reasonable reliance on information supplied by another person; or (c) was due to the act or default of another person, to an accident or to some other cause beyond the defendant’s control.

Section 731 is also different to the current ‘due diligence’ defence under s 85(1)(c)(ii) of the TPA, which the courts have interpreted to mean a ‘proper system to provide against contravention of the Act ... that it had provided adequate supervision to ensure that the system was properly carried out’: Universal Telecasters (Qld) Ltd v Guthrie (1978) 18 ALR 531, 534.

97 In Adams v ETA Foods Ltd [1987] FCA 402; (1987) 19 FCR 93, the Court held that the ‘due diligence’ defence was not available in the case of the former ss 995 and 996 (to which ss 1041H and 728(1) respectively are now functionally almost equivalent), where the ‘diligence’ activities had been approached in an ad hoc fashion, or where the defence was effectively an ex post facto rationalisation of the true facts.

99 For example, in the context of the PUMA Fund’s Master Information Memorandum, the Fund Manager prepares the Information Memorandum and the Series Supplement for each Series of Notes issued with the advice and assistance of the legal counsel: see PUMA Fund, above n 10, 1–2.

100 [1999] USCA7 578; 194 F 3d 867 (7th Cir, 1999).

101 [1999] SASC 186; (1999) 74 SASR 1.

102 See, eg, NRMA Ltd v Morgan [1999] NSWSC 407; (1999) 17 ACLC 1029. It is also likely, as a matter of the proper construction of s 733, that the ‘reasonable reliance’ defence implies some element of causation in a somewhat similar fashion to the law’s approach to liability for negligence: Duke Group Ltd (in liq) v Pilmer [1999] SASC 97; (1999) 73 SASR 64.

107 This liability is subject to s 1041I of the Corporations Act.

108 In June 1996, the Financial System Inquiry (‘FSI’), also known as the Wallis Inquiry after its Chairman Mr Stan Wallis, was commissioned to provide a stocktake of the results of the financial deregulation of the Australian financial system since the early 1980s. The FSI’s main aim was to recommend further improvements to the regulatory arrangements governing Australia’s financial system.

109 Following the FSI, many of the recommendations were implemented including the establishment of two different regulators – one focusing on market conduct and disclosure and the other on prudential issues. That is, ASIC and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (‘APRA’) were created. Many of the recommendations of the FSI were engulfed in a set of reforms of the Corporations Law known as the Corporate Law Economic Reform Program (‘CLERP’). The financial services reform aspect became known as ‘CLERP 6’. In March 1999, the CLERP 6 Consultative Paper, Financial Products, Service Providers, and Markets – An Integrated Framework, was issued, providing a regulatory framework for the licensing of financial product markets and service providers, disclosure requirements for such service providers and their representatives, and financial product disclosure: Treasury, Commonwealth, Financial Products, Service Providers and Markets – An Integrated Framework: Implementing CLERP 6 – Consultation Paper (1999) <http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/268/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=contents.asp> at 22 October 2006.

114 See Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 766B. Advice is usually provided in a RMBS program through investment banks, which structure the RMBS transactions for a fee and provide advice to any intermediary selling the bonds. The SPV or the licensed dealers and originators provide advice to potential investors in RMBSs. The information memorandum, prepared by the issuer or fund manager for distribution to potential investors in RMBSs, may also contain advice.

115 See Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 766C. Most of the participants in a RMBS transaction will be involved in ‘dealing’ in financial products, including

Trustees are not able to rely on the ‘self-dealing’ exception in the same way as the issuer can. The Australian Securitisation Forum has suggested that securitisation trusts, such as RMBS trusts, should be able to rely on this exception: Australian Securitisation Forum, above n 113, 1–2.

116 See Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 766E. A person provides a custodial or depository service to a client if they have an arrangement with the client to hold a financial product or a beneficial interest in a financial product in trust for, or on behalf of, the client: Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 766E. A RMBS transaction normally involves custodial or depository services in the context of the trustee providing such a service to the sponsoring bank or independent mortgage provider (‘IMP’). Such services might also be provided by the security trustee to the bondholders, in the event that a default occurs and their security is enforced.

117 More generally, the importance of the distinction between wholesale and retail clients in relation to various types of financial products is explained in Ch 7, Pt 7.1, Div 2 of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Regulations’). The extent of the legislative-style detail in these regulations is somewhat surprising. The Regulations contain the types of provisions that would normally be found in legislation that has been passed through Parliament, rather than subordinated legislation promulgated by the bureaucracy. The question arises as to whether the legislation, replete with significant logical gaps and lacking in detail, was hurriedly passed through Parliament for political purposes, with the bureaucracy left to fill in the detail after it was passed.