University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

SCHOOLING THE BLUES?

AN INVESTIGATION OF FACTORS ASSOCIATED

WITH PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS

AMONG LAW STUDENTS

WENDY LARCOMBE* AND KATHERINE FETHERS**†

There is now a growing body of empirical evidence confirming that lawyers and law students in Australia, as in the United States (‘US’), experience levels of psychological distress significantly higher than members of the general population and other professions.[1] The landmark 2009 study by the Brain and Mind Research Institute (‘BMRI’), published as ‘Courting the Blues’,[2] was not the first Australian study to investigate this issue, but it was perhaps the first to be heard as an alarm bell by legal professional bodies and law schools.[3] The BMRI study reported that, on an internationally recognised measure, 31 per cent of solicitors, 17 per cent of barristers and 35 per cent of law students recorded elevated levels of psychological distress compared with 13 per cent of the general population.[4] Subsequent studies with law students at the Australian National University and the University of Melbourne have produced very similar findings: both studies report that approximately 30 per cent of participating law students recorded elevated anxiety symptoms and a similar proportion recorded elevated depressive symptoms, compared with 13 per cent of the general population.[5]

As Townes O’Brien and her co-authors have observed, the BMRI report ‘hit Australian legal educators hard’,[6] particularly as the decline in mental health appears to begin in law schools. Students are known to enter law schools with rates of wellbeing no different to, and even higher than, the general population.[7] By the end of the first year of study in law, however, self-reported rates of psychological distress have increased significantly.[8] The negative impact of legal education on first-year law students does not appear to abate across the degree, and distress levels are similar in legal practice, indicating that the nature and quality of the psychological distress experienced by law students and lawyers may be ‘fundamentally similar’.[9] Law school thus appears to be an ideal site to develop and embed prevention and early intervention measures to address mental health difficulties that similarly affect law students and legal practitioners.

The first step to designing effective and sustainable interventions is to better understand what happens to law students’ mental wellbeing in law school and the range of factors associated with high levels of distress. In particular, it is important for law schools to know whether it is legal education per se that triggers or exacerbates law student distress, or whether some interaction of ‘external’ sources of distress and personal characteristics mediates students’ responses to the law school environment. As explained below, Self-Determination Theory (‘SDT’) provides the most promising explanation of the environmental variables contributing to the documented increase in psychological distress experienced by first-year law students. However, more research is needed. Although law student mental wellbeing has been recognised as an issue for some decades in the US, and there is now ample evidence of the prevalence of distress among law students, there has been limited empirical research investigating course-related and institutional factors that may be contributing to high levels of psychological distress among law students.[10] Without an improved understanding of the factors that adversely affect law student mental health, law schools could invest considerable effort in interventions that have little prospect of improving students’ wellbeing.[11]

It was in this context that the present study was designed to empirically investigate factors associated with high levels of psychological distress among a sample of Australian law students. An anonymous online survey was developed to explore a range of course-related variables that have been suggested in the research literature as potentially associated with law student psychological distress.[12] The study also investigated some of the personal tendencies attributed to law students, as well as the stresses associated with the costs of higher education and an increasingly competitive job market. The study was undertaken in 2012 with a sample of law students from Melbourne Law School (‘MLS’), the University of Melbourne. This article reports the findings of that research, including the levels and forms of psychological distress recorded and the factors associated with elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. In doing so, it aims to provide a source of comparative data for subsequent empirical studies examining students’ elevated levels of mental distress in higher education, as well as contributing to an evidence-base for pedagogical development, curriculum reform and mental health intervention planning in law schools.

Three general findings are noteworthy. First, all of the participant-related and course-related variables included in the study showed significant associations with elevated distress symptoms. By contrast, the only demographic variables that showed significant associations with elevated distress related to time commitments (paid work and family care). This strongly indicates that law student distress is mediated by students’ experiences, perceptions and cognitive constructs (as they interact with the law school environment), rather than by demographic variables. Second, different participant-related and course-related variables were found to be associated with the different forms of distress symptoms measured in the study – depression, anxiety and stress. Interventions to support student wellbeing will thus need to address the different forms of distress and their associated factors. Third, different variables were associated with different levels of distress symptoms, indicating that severe and extremely severe levels of distress have distinct triggers or risk associations. This is important information, indicating that programs and interventions tailored for the different forms and levels of distress measured in this study are likely to be most effective.

The article is organised as follows. Part II outlines the available empirical research and explanations of law student distress that informed the present research and Part III details the methods used in the 2012 study conducted at MLS. Results on levels of psychological distress (Part IV) and the few associated demographic factors (Part V) are then reported. Parts VI–VIII report the results of tests investigating associations between the non-demographic variables in the study (participant- and course-related factors) and elevated depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms, respectively. Finally, we discuss the implications of these findings for the planning of mental health initiatives in law schools and offer suggestions for further research (Part IX).

Empirical research to date has identified that the observed increase of psychological distress amongst law students is associated with a decrease in experiential thinking;[13] an increase in extrinsic motivations and values;[14] and a reduction in students’ experiences of autonomy, competence and relatedness.[15] It does not appear to be directly associated with the type and level of law course – for example, undergraduate entry LLB degree, or postgraduate entry JD degree.[16] However, ‘controlling’ law schools may have greater negative impacts on students’ mental wellbeing than schools that are ‘autonomy supportive’.[17]

The concept of ‘autonomy supportive’ social environments is a key element of SDT[18] – the best available explanatory model of law student distress. SDT posits that all people thrive in environments that meet basic human needs for regular experiences of autonomy, competence and relatedness to others. Those three basic psychological needs are more likely to be met when people act in pursuance of internalised goals – that is, when they are ‘autonomously motivated’ or feel that their actions are not only self-chosen, but also self-concordant or self-actualising.[19] In turn, people are more likely to act on the basis of internalised goals when their social and interpersonal environment is ‘autonomy supportive’.[20] Competence support and relationship support are also key elements of healthy environments as the three basic needs are additive: ‘an individual is best off when all three are present [in the social environment], and worst off with none present.’[21] However, SDT research has often focused on autonomy support as its designation as a ‘basic need’ can be controversial[22] – in part because ‘autonomy’ has a particular meaning within SDT.

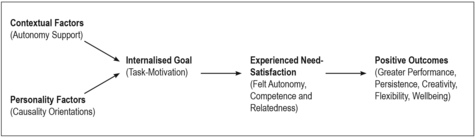

As Kennon Sheldon et al explain, SDT conceptualises autonomy as ‘the freedom to behave in accordance with one’s sense of self’;[23] it is not merely Western individualism or freedom of choice – and certainly not consumer choice where the options are fundamentally similar.[24] Lawrence Krieger describes it as authenticity, or the need to act authentically – that is, to act in accordance with one’s values and evolving interests.[25] Understandably, ‘felt autonomy’, meaning the perception that one’s actions are authentic, ‘is to some extent a dispositional variable’ – a result of the ‘individual’s characteristic way of relating to his/her own choices and outcomes.’[26] SDT research has established, however, that all individuals experience improved motivation and wellbeing in autonomy-supportive social and interpersonal environments – and vice versa.[27] SDT thus affords an integrated model of dispositional and situational/environmental influences on motivation and need satisfaction, with consequent impacts on learning, performance and subjective wellbeing.[28] SDT’s integrated causal-process model is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: SDT’s General Causal-Process Model

Source: Kennon M Sheldon et al, ‘Applying Self-Determination Theory to Organizational Research’ (2003) 22 Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management 357, 368 (Figure 2).

SDT research indicates that subjective wellbeing and other positive outcomes increase as the autonomy-supportive qualities of social contexts are improved. Sheldon et al explain that, in any social or interpersonal environment but particularly those in which one group is attempting to influence or direct the behaviour of others, such as educational contexts, ‘autonomy support’ has three key components: ‘taking the [directed] person’s perspective upon the situation, giving as much choice as possible, and providing a meaningful rationale when choice-provision is not possible’.[29] Autonomy-supportive social contexts can be contrasted with ‘controlling’ environments in which intrinsic motivations are undermined as those being directed come to feel that their actions are controlled by others rather than self-chosen or authentic.

Krieger has independently explored the ways in which law schools may unwittingly create and perpetuate controlling environments in which students feel that their autonomy is not recognised or valued.[30] He posits that law schools’ typically competitive culture and the win/lose nature of the legal adversarial paradigm undermine students’ internalised motivations and goals in favour of external rewards and measures of success. Personal values and emotions are similarly undermined by the emphasis accorded to objectivity and neutrality in legal analysis and reasoning.[31] Others consider the process of learning to ‘think like a lawyer’ to be inherently pessimistic and suggest it is this feature of legal education that distances students from their moral values and the social justice aspirations that often motivated their decision to study law.[32] Both explanations fit the SDT model, which predicts that people’s task motivation, need satisfaction and subjective wellbeing will be undermined in social environments that do not support people’s sense of autonomous/authentic action – that is, one that undermines intrinsic task motivation by distancing people from their deep values and evolving interests.

Many of the programs and interventions developed or suggested to improve law student wellbeing in Australia have been informed by SDT insights and its understanding of basic human needs. Hence, programs have sought to create enhanced opportunities for students to experience competence, relatedness and autonomy by: focusing on the teaching and acquisition of threshold skills and concepts; provision of timely academic skills support for underperforming students;[33] use of varied assessment forms and increased opportunities to obtain feedback;[34] promoting peer engagement and collaboration rather than competition between students;[35] fostering social justice goals and student participation in pro bono work to reinforce community service values and positive professional identities;[36] and providing programs that teach a range of life skills and self/stress-management within and alongside the formal curriculum.[37] The effectiveness of these approaches in reducing law student psychological distress has not yet been empirically tested. They may not, however, address all the factors contributing to law student distress.

While SDT and its conceptualisation of autonomy support provides a powerful account of the environmental factors that may contribute to observed declines in law student wellbeing, its theorisation of relevant dispositional factors is less developed. Research into the ‘lawyer’s personality’ or the specific dispositional and personality attributes found in people attracted to legal study and practice may provide insight into additional factors contributing to poor mental health in the legal profession and law schools.[38] Susan Daicoff’s work is particularly noteworthy in this context. Her comprehensive review published in 1997 of extant research on personality attributes of those attracted to law identified that law students often lack firm career plans – they more often enter law school as a way of continuing their academic interests and from a desire for intellectual stimulation rather than from a desire to enter a service profession, to help others or to address social issues.[39] Moreover, law students are commonly ‘Thinking’ rather than ‘Feeling’ types on the Myers–Briggs scale;[40] first-born or only children;[41] and they commonly present as socially confident, leadership-oriented, competitive and ebullient.[42]

Studies have consistently shown that law students and lawyers are also more likely to be motivated by achievement rather than altruism.[43] Subsequent to Daicoff’s review, a Canadian study found that law students differed significantly from medical students on measures of driven behaviour, achievement ethic and relaxation potential – that is, when compared with medical students, law students were found to have a significantly lower capacity for healthy diversion from work, a higher investment in ‘constant tangible accomplishment’,[44] and a strong drive for ‘new achievement rather than consolidating and enjoying previous accomplishments.’[45] This supports Daicoff’s supposition that law students’ strong achievement-orientation may underpin their workaholism and perfectionism – maladaptive strategies designed to meet unrealistic needs for continual accomplishment.[46] Increasing levels of paranoia and concern about comparisons with others (interpersonal sensitivity) in law students may also be associated with the problems that arise from an achievement-orientation in an environment in which most law students will in fact be ‘average’.[47] As Krieger notes, ‘law students often manifest extreme concern over how they may appear to or compare with others’[48] such that their actions and choices are often driven by maladaptive ‘performance-esteem’ (perfectionism) or ‘other-esteem’ (comparisons with others) rather than motivations that might found ‘genuine self-esteem’.[49]

Finally, in considering the factors that might be associated with law student mental wellbeing, it is important to take note of recent research identifying high and perhaps increasing levels of psychological distress among university student populations generally,[50] and the noted correlation between students’ psychological distress and perceived financial stress (rather than actual debt levels).[51] Uncertain employment prospects have also been identified as a likely contributor explaining elevated stress levels among university students in Hong Kong.[52] In the current economic environment in Australia, with increasing numbers of law graduates seeking to enter the legal services marketplace each year, further research is needed to ascertain whether worries about future employment prospects and current financial stresses are significantly contributing to law student distress.[53]

In summary, then, the research literature suggests that elevated levels of psychological distress amongst law students may be associated with: ‘environmental’ factors in law schools – course design, competitive culture, lack of autonomy support and so on; the distinct personality attributes of those attracted to study and practice law; and general stressors that particularly affect young people, including financial stress and uncertain job prospects.

The present study aimed to test empirically whether the variables suggested by the literature – environmental factors, personality or demographic characteristics and general stressors – were associated with elevated levels of psychological distress in a sample of Australian law students. The study employed a cross-sectional web-based survey of students currently enrolled in admission-to-practice law programs at MLS, an established and highly respected Australian law school. Ethics approval was granted by the relevant human research ethics committee, and the survey was administered in weeks two to four of second semester, 30 July – 17 August 2012.[54] This timing meant that even first-year law students at MLS would have generally completed at least four compulsory law subjects/units.[55] The timing also meant that the administration of the survey did not coincide with summative assessment tasks. Eligible students were invited to participate through advertising in student newsletters, and two emails from the MLS Dean invited participation and provided a hyperlink to the survey website. As an incentive, participants could elect to enter a prize draw to be eligible to win one of 10 $150 book vouchers. Information about counselling and support services available to students experiencing psychological distress was provided on the survey website and in all publicity materials. To ensure that participation in the survey did not itself contribute to distress, no survey items were compulsory, other than the consent question.[56]

Three hundred and twenty-one students commenced the survey and completed all questions for at least one of the DASS-21 scales (described below) and at least 75 per cent of the survey questions overall. This sample represented 46 per cent of eligible MLS students. As in similar surveys, the proportion of women among respondents (66 per cent) was significantly higher (p <0.001) than that of the study population (53 per cent).[57] In other respects, the MLS population was well proportionally represented by the survey participants, based on MLS enrolment data. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of survey participants

|

Demographic characteristic

|

Count

N = 321

|

% of valid responses

|

|

Gender

|

|

|

|

Female

|

203

|

65

|

|

Male

|

107

|

35

|

|

Missing data

|

11

|

|

|

Age

|

|

|

|

19-24

|

233

|

74

|

|

25 years and older

|

80

|

26

|

|

Missing data

|

8

|

|

|

Nationality

|

|

|

|

Australian

|

288

|

93

|

|

International

|

22

|

7

|

|

Missing data

|

11

|

|

|

Fee type

|

|

|

|

Commonwealth Supported Place

|

165

|

53

|

|

Full fee

|

146

|

47

|

|

Missing data

|

10

|

|

|

Year level

|

|

|

|

1st year

|

163

|

52

|

|

2nd year

|

91

|

29

|

|

3rd or more

|

59

|

19

|

|

Missing data

|

8

|

|

|

Living situation

|

|

|

|

University college

|

16

|

5

|

|

With domestic partner

|

34

|

11

|

|

With parent/s

|

122

|

39

|

|

Sharing with friends/flatmates

|

110

|

35

|

|

Living alone

|

31

|

10

|

|

Missing data

|

8

|

|

|

Average hours spent studying per week

|

|

|

|

<5

|

11

|

4

|

|

5–9

|

50

|

16

|

|

10–14

|

81

|

26

|

|

15–19

|

81

|

26

|

|

20+

|

91

|

29

|

|

Missing data

|

7

|

|

|

Average hours in paid employment per week

|

|

|

|

<5

|

104

|

33

|

|

5–9

|

89

|

28

|

|

10–14

|

73

|

23

|

|

15–19

|

34

|

11

|

|

20+

|

14

|

4

|

|

Missing data

|

7

|

|

|

Average hours caring for family per week

|

|

|

|

<5

|

241

|

77

|

|

5–9

|

41

|

13

|

|

10–14

|

14

|

5

|

|

15–19

|

5

|

2

|

|

20+

|

10

|

3

|

|

Missing data

|

10

|

|

An online survey was considered the best means of encouraging student participation in a wellbeing study as it would ensure anonymity and voluntary participation. Survey items were developed based on the literature review discussed above, consultations with stakeholders at MLS, and the results of the 2011 MLS Wellbeing Survey. The 2012 survey comprised demographic questions; two measures of psychological wellbeing; questions about common causes of law student stress, including motivations for study, financial stress and high self-expectations; and questions about protective course-related factors such as perceived teacher autonomy-support, perceived competence in threshold skills and peer engagement.

Demographic questions asked for participants’ gender, age, current living situation, fee-type (Commonwealth Supported Place or full-fee), nationality (Australian, international), program (JD, LLB), year level, and average hours per week spent studying, in paid work and caring for family members.

Psychological wellbeing measures comprised the DASS-21[58] and Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing Scales (‘PWBS’).[59] The DASS-21 consists of three sub-scales assessing depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms respectively. It was chosen over the K10 because of its capacity to discriminate effectively between these three states of psychological distress, as well as the availability of Australian normative data.[60] As the DASS-21 only assesses negative psychological symptoms, the Ryff’s PWBS were administered to gather a more comprehensive snapshot of student wellbeing. The Ryff’s PWBS measures six elements of positive mental wellbeing that are known to be negatively correlated with depression, anxiety and stress. It is a well-established scale that can provide insight into factors that might protect against psychological distress in particular environments.

Common causes of law student stress were investigated by questions assessing students’ reasons for studying law and their sense of career direction; worry about job prospects and current financial stress; and high self expectations. These variables were grouped as ‘participant-related factors’ as they explore students’ individual motivations, perceptions and expectations (cf demographic factors).

Six items investigated students’ reasons for studying law using a five-point response scale from ‘not at all true of me’ to ‘extremely true’. Five of these items reproduced those used by Sheldon and Krieger in their research with US law students to investigate intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, and a sixth item reflecting amotivation was developed in consultation with these researchers.[61] These items enabled an ‘intrinsic motivation score’ to be calculated, reflecting the extent to which students were studying law because of its intrinsic interest or perceived value. (Scores for the two ‘internal’ reasons were summed and scores on the four ‘external’ reasons were subtracted to obtain a total intrinsic motivation score).[62] Thus, a low intrinsic motivation score would mean that a student was studying law primarily in order to please others or avoid a sense of guilt, to obtain external rewards in due course, or because they could see no better options. Alongside this measure, the survey included a three-item career direction scale assessing whether students knew what type of career they wanted to undertake and with what type of employer. A single item was included asking students whether they expected to practice law after graduating (level of agreement on a five-point scale).

Worry about job prospects and current financial stress were measured by level of agreement on a five-point scale with the statements: ‘I worry about my future employment and job prospects’ and ‘My financial situation is a significant source of stress’.

High self-expectations were identified by law students in the 2011 MLS wellbeing survey as the most common source of stress. This factor was investigated in 2012 through the inclusion of 11 items that asked respondents about self-imposed standards (perfectionism) – always wanting to do one’s best – and worry about comparisons with others.[63] A typical item on the perfectionism scale was: ‘I try to do everything as well as possible’ and a typical item on the worry about comparisons scale was: ‘I spend too much time worrying about what people think of me’.

Course-related factors that may exacerbate or protect against psychological distress were investigated through questions assessing perceived teacher and faculty autonomy support; course satisfaction; peer engagement; whether students were comprehending and coping with the course material; whether they were present and prepared for classes; their perceived competence in threshold skills; and satisfaction with academic results in law to date. A minimum of three items assessed each course-related factor and the scales had good to strong reliability coefficients (reported in Appendix A). The teacher and faculty autonomy support scales were a modified version of Black and Deci’s Learning Climate Questionnaire as applied by Sheldon and Krieger in their research with US law students.[64]

This study aimed to investigate factors associated with elevated levels of psychological distress in a sample of Australian law students. The DASS-21 was used to measure respondents’ experience of the symptoms of three distinct forms of distress: depression, anxiety and stress. The Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, prepared by the scale developers through tests with non-clinical samples, stipulates cut-off scores for each of the scales to classify results on a continuum from ‘normal’ to ‘extremely severe’ symptom levels.[65] We used these cut-off scores to classify DASS-21 raw scores as ‘normal’, ‘mild’, ‘moderate’, ‘severe’ or ‘extremely severe’ for each of the depression, anxiety and stress scales.

Consistent with earlier studies,[66] ‘elevated’ psychological distress was defined in this study as a score in the moderate to extremely severe range (‘moderate+’) on any of the three DASS-21 scales. In studies with general adult populations, this range included fewer than 13 per cent of respondents.[67] Moreover, moderate and higher levels of psychological distress are likely to impact on a person’s daily activities and functioning so that interventions to address symptoms at this level are indicated.[68] Supplementary analyses were conducted on the responses of participants with severe to extremely severe (‘severe+’) DASS-21 symptom levels as law schools are particularly concerned with understanding and addressing the factors associated with such high levels of psychological distress among their students. In studies with general adult populations, this range included fewer than six per cent of respondents.[69]

As outlined above, three groups of explanatory variables were investigated: ‘demographic’ variables (including age, gender, living situation, and time commitments); ‘participant-related variables’ (potential risk factors such as high perfectionism or financial stress); and ‘course-related variables’ (potentially protective factors such as high perceived teacher/faculty autonomy support or peer engagement). Statistical analyses investigated whether each of these variables had a statistically significant association[70] with elevated levels of psychological distress (univariate analyses). The strength of associations was measured by ascertaining the Odds Ratio (‘OR’) – in this study the OR calculates ‘the odds’ of a respondent who is experiencing an elevated level of psychological distress returning a positive response for a particular explanatory variable. Variables that were found to have a significant association with elevated distress levels were then included in a multivariate analysis to identify which variables maintained a strong, independent association with elevated depressive, anxiety or stress symptoms when the other explanatory variables were taken into account. More detailed information on the statistical analyses undertaken is provided in Appendix A.

One hundred and fifty participants in the survey reported experiencing moderate+ symptoms on at least one of the scales: depression, anxiety or stress. Anxiety symptoms were most common with 33 per cent of respondents recording scores in the moderate+ range on this scale. Moderate+ stress symptoms were reported by 30 per cent of respondents and moderate+ depressive symptoms by 26 per cent of respondents. Table 2 compares the respondents’ mean DASS-21 scores with those of a non-clinical sample from the general adult Australian population. It confirms that the law students in our survey were significantly more likely than members of the general population to report elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress.

Table 2: MLS participants’ mean scores on DASS-21 depression, anxiety and stress scales compared with those of a general Australian adult sample

|

|

Australian adult sample* N=497

|

Law student sample

N=316

|

Anova statistic

p value

|

|

Depression

|

|

|

|

|

Mean

|

2.6

|

4.6

|

p <0.001

|

|

SD

|

3.9

|

4.0

|

|

|

Anxiety

|

|

|

|

|

Mean

|

1.7

|

3.7

|

p <0.001

|

|

SD

|

2.9

|

3.8

|

|

|

Stress

|

|

|

|

|

Mean

|

4.0

|

7.2

|

p <0.001

|

|

SD

|

4.2

|

4.6

|

|

|

*John Crawford et al, ‘Percentile Norms and Accompanying

Interval Estimates from an Australian General Adult Population Sample

for

Self-Report Mood Scales (BAI, BDI, CRSD, CES-D, DASS, DASS-21, STAI-X, STAI-Y,

SRDS, and SRAS)’ (2011) 46 Australian Psychologist 3.

|

|||

The co-presentation of elevated distress symptoms was investigated for the 305 respondents who answered all questions for all three DASS-21 scales. Fifty-five per cent (169/305) of these students were in the normal-mild range on all three scales. For students in the moderate+ range on any scale, 34 per cent (46/136) recorded elevated distress on only one scale, while 66 per cent (90/136) experienced at least two of the three types of distress. Of participants recording elevated levels for two forms of distress, anxiety and stress were the most common co-presentation of symptoms, accounting for more cases than the combined number of depression and anxiety and depression and stress cases. Twenty-nine per cent (39/136) of the respondents reported moderate+ symptoms of distress on all three scales.

Of concern, 22 per cent (68/305) of the sample were classified as experiencing severe+ symptoms of psychological distress on one or more of the DASS-21 scales. It is noteworthy that these respondents appeared more likely to experience a distinct state or form of distress compared with the students reporting moderate levels of distress. Fifty-six per cent of respondents with DASS-21 levels in the severe+ range reported symptoms specific to only one form of distress (38/68), indicating that it is important to address the different forms or states of distress when planning interventions. Fifteen per cent of severe+ respondents (10/68) reported severe+ symptoms on all three scales.

As discussed earlier, the Ryff’s PWBS measures positive wellbeing in relation to six dimensions: personal growth; environmental mastery; positive relationships with others; self-acceptance; purpose in life; and sense of autonomy.[71] High scores on these scales are associated with a state of wellbeing or wellness that is considered protective against psychological distress.

Respondents’ scores on the Ryff’s PWBS were correlated with scores on the DASS-21 scales (Appendix B). We found statistically significant negative correlations between depression, anxiety and stress symptoms on the DASS-21 scales and environmental mastery, positive relations with others and self-acceptance on the Ryff’s PWBS. In other words, as depression or anxiety or stress increased, environmental mastery, positive relations with others and self-acceptance decreased and vice versa. DASS-21 depression ratings were strongly significantly related to all Ryff’s PWBS categories, although personal growth and purpose were less related to DASS-21 levels than the other Ryff’s PWBS categories. Environmental mastery and self-acceptance were most strongly negatively associated with DASS-21 depression levels. There was also a strong negative relation between DASS-21 anxiety and stress ratings and positive relations with others. Personal growth and purpose scale scores were not significantly associated with anxiety and stress levels.

This analysis suggests that the three areas of positive psychological functioning where law student wellbeing is likely undermined currently are:

Ryff’s PWBS results indicate that efforts to improve law student mental health would be well advised to target these areas. More information is needed, however, to understand what environmental mastery and self-acceptance might mean, and how they might be improved, in a law school context. The participant and course-related variables reported in Parts VI–VIII below are of assistance in this respect.

The survey asked about participants’ age, gender, living situation, fee type, nationality, year level, program and weekly time commitments. Of interest, neither age nor gender was independently associated with symptoms of psychological distress. As found in previous surveys, there were also no statistically significant differences in the levels of psychological distress experienced by Australian and international students;[72] and no significant differences in psychological distress based on program type (JD, LLB) and year level within program, confirming results of an earlier study at MLS.[73] Frequency tables on the proportion of participants with elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress stratified by the main demographic characteristics are provided in Appendices C1, D1 and E1, respectively.

The only significant associations between psychological distress and demographic characteristics were related to participants’ commitments to paid work or family care. Students undertaking paid work for 15 or more hours per week were significantly more likely to experience moderate+ anxiety (OR = 2.1, CI.95 = [1.1-4.0], p = .03). However, there was not a significant association between hours in paid work and severe+ anxiety, nor between hours in paid work and depression or stress. By contrast, commitments to family care were significantly associated with elevated levels of all forms of distress: depression, anxiety and stress (Table 3).

Twenty-three per cent of the sample (70/311) indicated that they spent five or more hours per week caring for family members. ORs shown in Table 3 indicate that respondents experiencing severe+ depression were 3.5 times more likely to report commitments to family care than students who were not in this depression category. This indicates a very strong association between family care and very high levels of depression – in other words, family care increases the risk of being in the severe+ depression group. A strong association is also seen between family care and both moderate+ and severe+ anxiety. There is also an increased risk of moderate+ stress in those students spending five or more hours per week caring for family members.

Table 3: Odds ratios for elevated DASS-21 distress levels by family care of five or more hours per week

|

|

Moderate+ symptoms: Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence

Intervals

|

p value

|

Severe+ symptoms: Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence

Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Depression

|

|

|

|

|

|

Caring for family five or more hours per week

|

|

|

|

|

|

No

|

1

|

0.09

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Yes

|

1.7 [1.0–3.1]

|

|

3.5 [1.6–7.8]

|

|

|

Anxiety

|

|

|

|

|

|

Caring for family five or more hours per week

|

|

|

|

|

|

No

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

|

|

Yes

|

2.8 [1.6–4.8]

|

|

2.4 [1.2–4.8]

|

0.02

|

|

Stress

|

|

|

|

|

|

Caring for family five or more hours per week

|

|

|

|

|

|

No

|

1

|

0.02

|

1

|

0.08

|

|

Yes

|

2.0 [1.1–3.5]

|

|

1.9 [0.9–3.9]

|

|

|

Note: Statistically significant results, p <0.05, are

presented in bold type.

|

||||

The survey did not ask participants to specify whether the family members they were caring for were children or older relatives, but when we stratified this group by living situation, respondents who undertook five or more hours a week of family care who were living with a domestic partner scored significantly lower on both the DASS-21 depression and anxiety scales than respondents who were living with parents and caring for family members five or more hours per week (depression mean scores 6.4 versus 9.7, p = 0.04 and anxiety mean scores 7.3 versus 10.2, p < 0.01). Therefore we could extrapolate that caring for older family members may account for the higher risk ratio for depression and anxiety in the group with family care commitments.

The associations between elevated symptoms of depression and participant-related factors were examined. As explained above, these survey items asked whether participants perceived that they were affected by common causes of stress including lack of motivation for study, financial and career worries, or high self-expectations. The frequency data are provided in Appendix C2 and crude ORs are displayed in Table 4. As Table 4 shows, of the seven factors investigated, a high perfectionism score was the only factor not significantly associated with elevated levels of depressive symptoms.

Table 4: Associations of participant-related variables and depression symptoms – univariate analysis

|

|

Moderate+ Depression symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Severe+ Depression symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Intrinsic motivation score

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

4.9 [2.8–8.7]

|

|

7.5 [3.3–17.1]

|

|

|

Career direction rating

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

0.30

|

|

Low**

|

3.0 [1.7–5.3]

|

|

1.5 [0.6–3.6]

|

|

|

Expect to practice law

|

|

|

|

|

|

Agree

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

0.07

|

|

Not agree

|

3.4 [2.0–6.0]

|

|

2.2 [1.0–4.9]

|

|

|

Worry about job prospects

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all true or Slightly true

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

0.02

|

|

Moderately true or Very true

|

2.5 [1.4–4.3]

|

|

3.1 [1.2–7.9]

|

|

|

Financial stress

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all true–Moderately true

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

0.10

|

|

Very true

|

3.1 [1.9–5.1]

|

|

2.0 [0.9–4.3]

|

|

|

Perfectionism rating

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–low

|

1

|

0.66

|

1

|

0.82

|

|

High*

|

0.8 [0.5–1.5]

|

|

0.8 [0.3–2.1]

|

|

|

Worry about comparisons

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–low

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

High*

|

3.6 [2.1–6.2]

|

|

6.0 [2.6–13.8]

|

|

|

**represents bottom quartile of participants from related survey

score

* represents top quartile of participants from related survey score

Note: Statistically significant results are presented in bold

type.

|

||||

Intrinsic motivation, an aggregate score derived from the students’ reasons for studying law, is seen to be strongly associated with elevated depression symptoms, with more than half of those students in the bottom quartile for intrinsic motivation experiencing moderate+ depressive symptoms. ORs show that respondents experiencing severe+ depression were 7.5 times more likely, and those experiencing moderate+ depression 4.9 times more likely, to record a low intrinsic motivation score. Given this finding, we further analysed the components that contributed to this variable (Appendix F). A very strong risk factor for depression, particularly severe+ depression, was any level of agreement that a participant was studying law because ‘I would feel guilty, ashamed or anxious if I weren’t. That is, one reason I’m in law school now is that I feel I “should” do this course, even though I’m not sure I want to’. Respondents who selected any of the four response options from ‘slightly true’ to ‘extremely true’ (that is, anything other than ‘not at all true’) were at particularly high risk of experiencing severe+ depression (OR = 9.0, CI.95 = [3.7-22.2], p <0.001, Appendix F).

With respect to the other participant-related variables analysed, there was an extremely strong univariate association between moderate+ depression and a high score on the ‘worry about comparisons’ scale, and this association was even greater for severe+ depression. Worry about job prospects was also significantly associated with both moderate+ and severe+ depression. Financial stress, lack of career direction, and non-agreement with ‘expect to practice law’ were all strongly associated with moderate+ depression.

The associations between elevated symptoms of depression and course-related variables were examined. As explained above, the research literature suggests that these variables, or aspects of law school experience, are likely to support, or undermine, student mental wellbeing. The frequency data are provided in Appendix C3 and ORs are displayed in Table 5. As the data show, all seven variables were significantly associated with moderate+ depression symptoms, and six of the seven were significantly associated with severe+ depression symptoms.

Table 5: Associations of course-related variables and depressive symptoms – univariate analysis

|

|

Moderate+ Depression symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Severe+ Depression symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Teacher and faculty Support

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

3.7 [2.1–6.4]

|

|

8.3 [3.5–19.2]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Course satisfaction

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

5.2 [3.0–9.2]

|

|

5.1 [2.3–11.6]

|

|

|

Peer engagement

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

3.4 [2.0–5.8]

|

|

4.4 [2.0–9.9]

|

|

|

Comprehending and coping

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

3.3 [1.9–5.9]

|

|

4.2 [1.9–9.2]

|

|

|

Prepared and present

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.01

|

1

|

0.83

|

|

Low**

|

2.1 [1.2–3.5]

|

|

1.1 [0.5–2.6]

|

|

|

Perceived competence

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

3.6 [2.1–6.1]

|

|

5.5 [2.4–12.4]

|

|

|

Results satisfaction

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.03

|

1

|

0.01

|

|

Low**

|

1.9 [1.1–3.4]

|

|

2.8 [1.3–6.2]

|

|

|

**represents bottom quartile of participants from related survey

score

Note: Statistically significant results are presented in bold

type.

|

||||

The strongest association for severe+ depressive symptoms was with perceived teacher/faculty autonomy support: students experiencing severe+ depressive symptoms were more than eight times as likely to feel unsupported by their law teachers and the faculty as a whole. These students are also more than five times as likely to report low levels of satisfaction with their law course, and low perceived competence in their threshold skills. Low levels of peer engagement, perceived low ability to comprehend and cope with the course materials, and low results satisfaction were also significantly associated with severe+ depression symptoms.

The strongest association for moderate+ depressive symptoms was with low course satisfaction, followed by low perceived teacher/faculty support, low perceived competence, low peer engagement and low perceived ability to comprehend and cope with the course materials. A low self-rating of preparedness for class and low results satisfaction were also significantly associated with moderate+ depressive symptoms.

A multivariate analysis of the factors associated with elevated depressive symptoms was performed as described in Appendix A. As expectation to practice law and career direction were found to be extremely highly correlated, career direction was removed to improve the health of the model. For moderate+ depression, 12 variables were entered: intrinsic motivation score, expectation to practice law, worry about job prospects, financial stress, worry about comparisons, teacher/faculty support, course satisfaction, peer engagement, comprehending and coping, prepared and present, perceived competence, and satisfaction with results. As shown in Table 6, adjusted odds ratios (‘AOR’) were calculated and, after controlling for other variables, the factors found to be independently related to moderate+ depression were low course satisfaction (AOR = 2.4), low intrinsic motivation score (AOR = 2.3), and high worry about comparisons (AOR = 2.0).

The multivariate analysis for severe+ depression included 10 variables: caring for family five or more hours per week; intrinsic motivation score; worry about job prospects; worry about comparisons; teacher/faculty support; course satisfaction; peer engagement; comprehending and coping; perceived competence; and satisfaction with results. As shown in Table 6, after adjustment for other variables, low perceived teacher/faculty autonomy support (AOR = 3.2) remained significantly associated with severe+ depression, while low intrinsic motivation approached borderline significance (AOR = 3.0).

Table 6: Variables independently associated with depression symptoms after multivariate analysis

|

|

Moderate+ Depression Symptoms

|

Severe+ Depression Symptoms

|

||

|

|

Adjusted Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Adjusted Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Intrinsic motivation score low

|

2.3 [1.1-4.9]

|

0.04

|

3.0 [1.0-9.3]

|

0.06

|

|

Worry about comparisons high

|

2.0 [1.0-4.2]

|

0.05

|

-

|

-

|

|

Teacher/faculty support low

|

-

|

-

|

3.2 [1.1-9.3]

|

0.03

|

|

Course satisfaction low

|

2.4 [1.0-5.6]

|

0.05

|

-

|

-

|

The associations between elevated symptoms of anxiety and participant-related factors are shown in Table 7 (frequency data are provided in Appendix D2). Five variables showed a significant association with either moderate+ anxiety or severe+ anxiety symptoms. As with depressive symptoms, a high perfectionism rating was not statistically associated with elevated levels of anxiety. Non-agreement with ‘expect to practice law’ was associated with severe+ anxiety symptoms, but did not reach significance for moderate+ anxiety symptoms. By contrast, a low intrinsic motivation score was significantly associated with moderate+ anxiety, but, unlike depression, not severe+ symptoms of anxiety.

The strongest univariate association for anxiety was with high levels of worry about comparisons with others. Students with elevated anxiety symptoms were more than three times as likely to record a high score on the ‘worry about comparisons’ scale. Concerns about job prospects and financial stress were also strongly associated with both moderate+ and severe+ anxiety levels.

Table 7: Associations of participant-related variables and elevated anxiety symptoms – univariate analysis

|

|

Moderate+ Anxiety Symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Severe+ Anxiety Symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Intrinsic motivation score

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.04

|

1

|

0.18

|

|

Low**

|

1.8 [1.1–3.1]

|

|

1.7 [0.8–3.4]

|

|

|

Career direction rating

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.04

|

1

|

0.05

|

|

Low**

|

1.8 [1.0–3.1]

|

|

2.1 [1.1–4.3]

|

|

|

Expect to practise law

|

|

|

|

|

|

Agree

|

1

|

0.26

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Not agree

|

1.4 [0.8–2.4]

|

|

2.8 [1.5–5.5]

|

|

|

Worry about job prospects

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all true or Slightly true

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Moderately true or Very true

|

2.5 [1.5–4.2]

|

|

2.9 [1.4–6.1]

|

|

|

Financial stress

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all true–Moderately true

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

0.04

|

|

Very true

|

2.8 [1.7–4.5]

|

|

2.0 [1.1–3.8]

|

|

|

Perfectionism rating

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–low

|

1

|

0.59

|

1

|

0.46

|

|

High*

|

1.2 [0.7–2.0]

|

|

1.3 [0.6–2.7]

|

|

|

Worry about comparisons

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–low

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

High*

|

3.1 [1.8–5.1]

|

|

3.5 [1.8–6.7]

|

|

|

**represents bottom quartile of participants from related survey

score

* represents top quartile of participants from related survey score

Note: Statistically significant results are presented in bold

type.

|

||||

The associations between symptoms of anxiety and course-related factors are shown in Table 8 (frequency data are provided in Appendix D3). All course related variables except ‘prepared and present for classes’ and ‘satisfaction with results’ were significantly associated with both moderate+ and severe+ anxiety symptoms.

The strongest associations for anxiety were with ‘low peer engagement’ and ‘low perceived teacher/faculty autonomy support’, which were strongly associated with both moderate+ and severe+ anxiety symptoms. Low peer engagement was particularly strongly associated with moderate+ anxiety while low ratings of teacher/faculty autonomy support were particularly strongly associated with severe+ anxiety. Respondents with elevated anxiety symptoms were also more than twice as likely to report low course satisfaction. A low level of comprehending and coping with the course material was strongly associated with severe+ anxiety symptoms. Perceived competence was related to severe+ anxiety but no significant association was seen with moderate+ symptoms of anxiety.

Table 8: Associations of course-related variables and anxiety symptoms – univariate analysis

|

|

Moderate+ Anxiety

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Severe+ Anxiety

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Teacher and faculty support

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

2.9 [1.7–4.9]

|

|

4.2 [2.1–8.3]

|

|

|

Course satisfaction

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

2.4 [1.4–4.1]

|

|

2.9 [1.5–5.8]

|

|

|

Peer engagement

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

4.4 [2.6–7.3]

|

|

2.8 [1.4–5.3]

|

|

|

Comprehending and coping

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.02

|

1

|

0.01

|

|

Low**

|

1.9 [1.1–3.3]

|

|

2.6 [1.3–5.2]

|

|

|

Prepared and present

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.79

|

1

|

0.46

|

|

Low**

|

0.9 [0.5–1.6]

|

|

1.3 [0.7–2.7]

|

|

|

Perceived competence

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.10

|

1

|

0.05

|

|

Low**

|

1.5 [0.9–2.6]

|

|

2.0 [1.0–3.8]

|

|

|

Results satisfaction

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.09

|

1

|

0.18

|

|

Low**

|

1.6 [1.0–2.8]

|

|

1.6 [0.6–3.3]

|

|

|

**represents bottom quartile of participants from related survey

score

Note: Statistically significant results are presented in bold

type.

|

||||

A multivariate analysis of the variables significantly associated with elevated anxiety symptoms was performed as described in Appendix A. For moderate+ anxiety, 11 variables were entered: in paid work 15 hours or more per week; caring for family member/s five or more hours per week; intrinsic motivation score; career direction;[74] worry about job prospects; financial stress; worry about comparisons; teacher/faculty support; course satisfaction; peer engagement; and comprehending and coping. After controlling for other variables, the factors found to be independently related to moderate+ anxiety symptoms were low peer engagement, family care, and financial stress (Table 9).

The multivariate analysis for severe+ anxiety had 10 variables: caring for family member/s five or more hours per week; expectation to practice law;[75] worry about job prospects; financial stress; worry about comparisons; teacher/faculty support; course satisfaction; peer engagement; comprehending and coping; and perceived competence. After adjustment for other variables, non-agreement with ‘expect to practice law’ and low perceived teacher/faculty autonomy support remained strongly independently associated with severe+ anxiety (Table 9).

Table 9: Variables independently associated with anxiety symptoms after multivariate analysis (non-significant results not shown)

|

|

Moderate+ Anxiety Symptoms

|

Severe+ Anxiety Symptoms

|

||

|

|

Adjusted Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Adjusted Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Family care five or more hours per week

|

2.1 [1.1–4.1]

|

0.02

|

-

|

-

|

|

Expect to practise law – not agree

|

-

|

-

|

3.1 [1.3–7.1]

|

<0.01

|

|

Financial stress

|

2.0 [1.1–3.6]

|

0.02

|

-

|

-

|

|

Teacher/faculty support low

|

-

|

-

|

2.7 [1.1–6.4]

|

0.02

|

|

Peer engagement low

|

2.3 [1.2–4.5]

|

0.02

|

-

|

-

|

The associations between elevated symptoms of stress and participant-related variables are shown in Table 10 (frequency data are provided in Appendix E2). Interestingly, lack of career direction and non-agreement with ‘expect to practice law’ were not significantly associated with elevated levels of stress. All other variables were significantly associated with stress. Worry about comparisons, worry about job prospects, and financial stress were all strongly associated with both moderate+ and severe+ stress symptoms. In contrast with depression and anxiety, perfectionism was significantly associated with symptoms of stress on univariate analysis, particularly severe+ stress (OR = 2.7, CI.95 = [1.4-5.4], p = <.01).

Table 10: Associations of participant-related variables and stress symptoms – univariate analysis

|

|

Moderate+ Stress Symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Severe+ Stress Symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Intrinsic motivation score

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.01

|

1

|

0.05

|

|

Low**

|

2.1 [1.2–3.6]

|

|

2.0 [1.0–4.1]

|

|

|

Career direction rating

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.10

|

1

|

1.00

|

|

Low**

|

1.6 [0.9–2.9]

|

|

1.0 [0.4–2.2]

|

|

|

Expect to practise law

|

|

|

|

|

|

Agree

|

1

|

0.06

|

1

|

0.34

|

|

Not agree

|

1.7 [0.9–2.9]

|

|

1.4 [0.7–2.9]

|

|

|

Worry about job prospects

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all true or Slightly true

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Moderately true or Very true

|

3.3 [1.9–5.6]

|

|

3.8 [1.7–8.5]

|

|

|

Financial stress

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not at all true–Moderately true

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Very true

|

3.1 [1.9–5.1]

|

|

2.9 [1.5–5.7]

|

|

|

Perfectionism rating

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–low

|

1

|

0.04

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

High*

|

1.8 [1.0–3.0]

|

|

2.7 [1.4–5.4]

|

|

|

Worry about comparisons

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–low

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

High*

|

3.2 [1.9–5.4]

|

|

4.1 [2.1–7.9]

|

|

|

**represents bottom quartile of participants from related survey

score

* represents top quartile of participants from related survey score

Note: Statistically significant results are presented in bold

type.

|

||||

The associations between elevated symptoms of stress and course-related variables are shown in Table 11 (frequency data are provided in Appendix E3). Results satisfaction and being prepared and present for classes were not significantly associated with elevated stress levels, and low course satisfaction was only significantly associated with moderate+ stress. The strongest association for elevated stress was with teacher/faculty support, with highly stressed students more than 3.5 times as likely to record a low rating of perceived autonomy support. Low scores on peer engagement and comprehending and coping were also strongly associated with both moderate+ and severe+ stress. Perceived competence was also significantly associated with elevated stress symptoms.

Table 11: Associations of course-related variables and stress symptoms – univariate analysis

|

|

Moderate+ Stress symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Severe+ Stress symptoms:

Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Teacher and faculty support

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

3.7 [2.2–6.4]

|

|

3.6 [1.8–7.0]

|

|

|

Course satisfaction

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

0.13

|

|

Low**

|

2.5 [1.5–4.3]

|

|

1.8 [0.9–3.5]

|

|

|

Peer engagement

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

3.4 [2.0–5.7]

|

|

2.8 [1.5–5.5]

|

|

|

Comprehending and coping

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

<0.01

|

|

Low**

|

3.9 [2.2–6.9]

|

|

2.9 [1.5–5.8]

|

|

|

Prepared and present

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

1.00

|

1

|

0.71

|

|

Low**

|

1.0

|

|

0.8 [0.4–1.8]

|

|

|

Perceived competence

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

<0.01

|

1

|

0.02

|

|

Low**

|

2.3 [1.4–3.9]

|

|

2.3 [1.2–4.4]

|

|

|

Results satisfaction

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average–high

|

1

|

0.20

|

1

|

0.34

|

|

Low**

|

1.4 [0.8–2.5]

|

|

1.4 [0.7–2.9]

|

|

|

**represents bottom quartile of participants from related survey

score

Notes: Statistically significant results are presented in bold

type.

|

||||

Eleven variables were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model for moderate+ stress: caring for family member/s for five or more hours per week, intrinsic motivation score, worry about job prospects, financial stress, perfectionism, worry about comparisons, teacher/faculty support, course satisfaction, peer engagement, comprehending and coping, and perceived competence. After controlling for other variables, the factors found to be independently associated with moderate+ stress were worry about job prospects (AOR = 2.3), financial stress (AOR = 2.0), and low peer engagement (AOR = 2.1) (Table 12).

The multivariate analysis for severe+ stress had nine variables entered: intrinsic motivation score, worry about job prospects, financial stress, perfectionism, worry about comparisons, teacher/faculty support, peer engagement, comprehending and coping, and perceived competence. Perfectionism (AOR = 2.7) remained statistically associated with severe+ stress after adjustment for other variables and worry about comparisons (AOR = 2.3) achieved borderline significance (Table 12). The association between severe+ stress and worry about job prospects approached borderline significance (AOR = 2.6).

Table 12: Variables independently associated with stress symptoms after multivariate analysis

|

|

Moderate+ Stress Symptoms

|

Severe+ Stress Symptoms

|

||

|

|

Adjusted Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

Adjusted Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals

|

p value

|

|

Worry about job prospects

|

2.3 [1.2–4.6]

|

0.01

|

2.6 [1.0–7.1]

|

0.06

|

|

Financial stress

|

2.0 [1.1–3.6]

|

0.03

|

-

|

-

|

|

Perfectionism

|

-

|

-

|

2.7 [1.2–5.8]

|

0.02

|

|

Worry about comparisons

|

-

|

-

|

2.3 [1.0–5.4]

|

0.05

|

|

Peer engagement low

|

2.1 [1.0–4.1]

|

0.04

|

-

|

-

|

The present study investigated factors associated with elevated levels of psychological distress among a sample of Australian law students. While there is now a growing body of evidence documenting the prevalence of distress among law students, there has been relatively little empirical investigation of the participant and course-related factors that may be contributing to students’ distress. Moreover, to date, empirical studies have rarely tested the strength of associations between explanatory variables and elevated levels of distress when a range of variables is taken into account (multivariate analysis). Without such analyses, our understanding of the factors contributing to law students’ levels of psychological distress is limited.

Our focus in this article was on reporting variables statistically associated with moderate+ and severe+ levels of distress. While moderate+ symptom levels were described as ‘elevated’, the subset of respondents experiencing severe+ symptom levels was independently analysed as it is particularly urgent that factors associated with such high levels of distress are identified and redressed.

Demographic, participant-related and course-related variables were investigated. It is noteworthy that few demographic differences distinguished those with elevated distress levels from those without.[76] On univariate analysis, for example, gender, age, nationality, law program and year level in the program were not significantly associated with either moderate+ or severe+ forms of distress. Indeed, the only ‘demographic’ variables that showed a significant association with elevated distress levels were commitments to paid work of 15 or more hours per week or to family care for five or more hours per week. By contrast, all of the participant-related and course-related variables included in the study showed statistically significant associations on univariate analysis with one or more forms of distress at either moderate+ or severe+ levels. Given that most studies of university student wellbeing to date have focussed on demographic variables rather than course-related factors,[77] this finding provides important direction for further research designed to identify student groups who may be at higher risk of experiencing psychological distress.

Another important finding from the present study was that different variables were associated with different forms of psychological distress, indicating that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to student mental wellbeing is unlikely to be effective. For example, high perfectionism was strongly independently associated with severe+ stress, yet it was not significantly associated with elevated depression or anxiety symptoms even on univariate analysis. Similarly, low perceived teacher/faculty autonomy support was strongly associated with severe+ depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms but not stress symptoms. In this respect, the DASS-21 proved to be a useful instrument not only for measuring respondents’ levels of psychological distress but also for distinguishing between elevated depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms. Our findings suggest that the different forms of distress and their associated variables need to be kept in mind when designing responses and services to improve law student wellbeing.

The differences between factors associated with moderate+ distress and those associated with severe+ distress are also informative. Interestingly, the variables that were found to be significantly associated on multivariate analysis with each form of severe+ distress were not significantly associated on multivariate analysis with moderate+ levels of that particular form of distress.[78] This may be due to the fact that co-presentation of two or three forms of distress was more common in the moderate+ range; when moderate distress was excluded from analysis, respondents were more likely to report severe+ distress on one scale only – that is, for a particular form of distress. The finding suggests, however, that severe+ levels of distress have distinct triggers or risk associations. For this reason, the factors associated with severe+ levels of distress and those associated with moderate+ levels of distress are discussed separately in the next sections.

As shown in Table 13, only four variables were independently associated with severe+ symptoms of the different forms of distress after other variables had been taken into account. Notably, low teacher/faculty autonomy support was strongly independently associated with both severe+ depression and anxiety. Not agreeing that you expected to practice law was also associated with severe+ anxiety, while perfectionism and worry about comparisons (both forms of high self-imposed standards) were associated with severe+ stress.

Table 13: Variables independently associated with severe+ distress by form of distress

|

Variable

|

Severe+ Distress Symptoms:

Form/s of Distress

|

|

Teacher/faculty support low

|

Depression + Anxiety

|

|

Expect to practice law – not agree

|

Anxiety

|

|

Perfectionism high

|

Stress

|

|

Worry about comparisons high

|

Stress

|

Our results indicate that severe+ psychological distress in the form of depression or anxiety would be best addressed by initiatives designed to improve student perceptions of teacher/faculty autonomy support as described within SDT. That is, as outlined above, by: teachers and faculty members demonstrating understanding of students’ perspectives and experiences; providing meaningful choices that enable students to pursue emerging interests and express core values; and justifying when lack of choice is necessary so that students may internalise the reasoning, thereby reducing the perception of external ‘controls’ and unnecessary restrictions. Low perceived teacher/faculty support scores mean that these students feel controlled, misunderstood and/or undersupported by both their teachers and the faculty generally.[79] The SDT research literature provides additional guidance on teacher training methods and teaching practices that promote student autonomy, with positive results for learning as well as wellbeing.[80] However, more research that trials and evaluates autonomy-supportive methods developed specifically for law teaching would be extremely useful. In addition to curriculum innovations and teaching methods that support students’ autonomy, access to individual course advising, academic advising and career counselling may assist students experiencing severe+ depressive or anxiety symptoms to identify the meaningful choices available to them and also to help them feel that their teachers and the faculty understand their perspective.