University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE HIGH COURT ON CONSTITUTIONAL LAW:

THE 2012 STATISTICS

ANDREW LYNCH* AND GEORGE WILLIAMS**

This article presents statistical information about the High Court’s decision-making for 2012 at both an institutional and individual level, with an emphasis on constitutional cases as a subset of the total. The results have been compiled using the same methodology[1] employed in earlier years.[2]

In previous articles in this ongoing series, we have routinely commenced with an acknowledgement of the limitations that inevitably inhere in an empirical study of the decision-making of the High Court over just one year, advising that care must be taken not to invest too much significance in the percentage calculations given the modesty of the sample size. This is most evident in respect of the subset of constitutional cases. However, we have also maintained, despite that qualification, that an annual examination of the way in which the Court decides the cases it hears is nevertheless illuminating – both about the cases themselves and the degree of consensus or diversity of approach amongst its individual members in their resolution. On that last point, we have always been careful to emphasise that we do not presume to attribute greater ‘influence’ to particular individuals within the Court’s majority in any specific case or the cases as a collection. We reiterate all those sentiments for this article and essentially regard them as read for this and subsequent statistical studies.

The year of 2012 was the final on the Court for Gummow and Heydon JJ. As these studies have shown, particularly in recent years, these judges have made very different contributions to the Court. Justice Gummow served for 17 years and throughout his tenure was a consistent member of the majority under Brennan CJ, Gleeson CJ and French CJ. Justice Heydon joined the Court in 2003 and for a time was regularly to be found in the Court’s majority bloc. However, as we have seen, he gradually moved to the position of being the Court’s frequent outlier, something that was especially noticeable after the departure of Kirby J in early 2009.

The results presented in this article hold particular interest in respect of both of these departing members. Has their final year on the Court mirrored the familiar pattern of earlier years for each or did the 2012 cases present them with opportunities and challenges that upset these expectations? At the same time, what of the rest of the Court? As the era of the Gummow-Hayne joint judgment closes, is there a comparably striking partnership in the ascendant? Or are the present judges less likely to express their reasons with any particular colleague over others? Has the remarkable surge of unanimity in the first years of Chief Justice French’s leadership recovered from its slump in 2011 or is low unanimity the new norm? The answers to these and other questions lie in the information we present in the tables below.

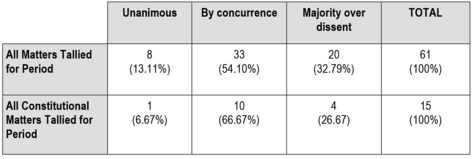

Table A: High Court of Australia Matters Tallied for 2012

A total of 61 matters were tallied for 2012 – considerably higher than the 48 tallied in both the two preceding years.[3] The greater number of matters decided did not see any corresponding increase in the proportion determined unanimously. In fact, the rate of cases decided unanimously fell further from one in six in 2011. This downward trend is in stark contrast to the first two years of the French Court, which featured an exceptionally high level of unanimity – 44 per cent of cases in 2009 and 50 per cent in 2010. To the extent that it is possible to make general observations divorced from the uniqueness of any set of cases in a given year, the reasons why unanimity has proven so elusive may become more apparent through consideration of later tables.

In any case, it would be a mistake to conclude that consensus was at a low ebb more generally on the Court in 2012. The fact that over half of all cases were decided by a number of concurring opinions and without dissent indicates otherwise. Indeed, the picture for last year is the reverse of that which preceded it. In 2011, exactly half the Court’s decisions were accompanied by at least one dissenting opinion, while in only a third did all sitting judges agree as to the outcome, albeit through two or more concurrences. In 2012, dissent was notably less frequent, in just under a third of cases decided. Although the level of consensus on the Court manifested itself less often through delivery of a single opinion, it was certainly higher than the year before.

2012 also saw, in striking fashion, the reversal of a trend towards a diminishing number of constitutional matters over the last few years.[4] In 2011 we tallied just eight matters as involving constitutional issues, but last year there was almost double that number with 15. While the classification of matters as belonging to this subset is obviously dependent upon our methodology, which as we have previously made clear[5] errs on the side of generous inclusion rather than selection according to some subjective criterion requiring discussion of constitutional issues that is ‘substantial’ or ‘decisive’, we have, of course, applied that methodology consistently over these studies. So, although it is undeniable that in some of the 15 matters so tallied for 2012 the constitutional issues were, at best, peripheral,[6] there were still significantly more of such matters than were picked up by the application of the same methodological approach in earlier years. In short, constitutional issues featured far more often in the judgments of the Court’s members last year.

It is worth restating the definitional criteria that determine our classification of matters as ‘constitutional’. They were provided by Stephen Gageler SC, now Gageler J of the High Court, when he gave the inaugural annual survey of the High Court’s constitutional decisions in 2002. Mr Gageler SC viewed ‘constitutional’ matters as:

that subset of cases decided by the High Court in the application of legal principle identified by the Court as being derived from the Australian Constitution. That definition is framed deliberately to take in a wider category of cases than those simply involving matters within the constitutional description of ‘a matter arising under this Constitution or involving its interpretation’.[7]

Our only amendment to this statement as a classificatory tool has been to additionally include any matters before the Court involving questions of purely state or territory constitutional law.[8] In 2012, there were, however, no such cases.

Although the number of constitutional matters the Court decided last year rose, it has not, as a percentile over the course of these annual surveys, had so few featuring dissenting opinions. The number of constitutional matters that splits the Court in any year has tended to be about 50 per cent. Across these studies, it certainly has not been as low as last year’s rate of approximately a quarter.

The set of constitutional cases comprises matters variously decided by seven, six, five and three judges sitting together. The only unanimous matter tallied is Saraceni v Jones, a refusal of special leave by French CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ for which reasons were briefly given.[9]

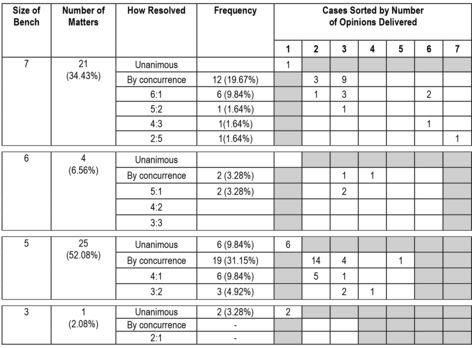

TABLE B (I) All Matters – Breakdown of Matters by Resolution and Number of Opinions Delivered[10]

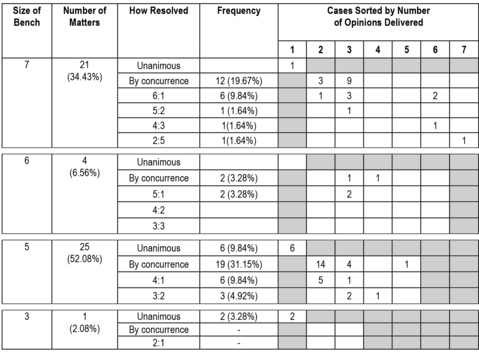

TABLE B (II) Constitutional Matters – Breakdown of Matters by Resolution and Number of Opinions Delivered[11]

Tables B(I) and (II) reveal several things about the High Court’s decision-making over 2012. First, they present a breakdown of, respectively, all matters and then just constitutional matters according to the size of the bench and how frequently the bench split in the various possible ways open to it. Second, the tables record the number of opinions which were produced by the Court in making these decisions. This is indicated by the column headed ‘Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered’. Immediately under that heading are the figures 1 to 7, which are the number of opinions which it is possible for the Court to deliver. Where that full range is not applicable, shading is used to block off the irrelevant categories. It is important to stress that the figures given in the fields of the ‘Number of Opinions Delivered’ column refer to the number of cases containing as many individual opinions as indicated in the heading bar.

These tables should be read from left to right. For example, Table B(I) tells us that of the 21 matters heard by a seven member bench, six produced a 6:1 split, and in one of those the Court delivered two separate opinions.[12] That table enables us to identify the most common features of the cases in the period under examination. In 2012 these were the delivery of a 5:0 decision resolved through two concurring opinions. Only in our surveys for 2009 and 2010 has this not been the case – with the high rate of unanimous decisions by a five-member bench in those years having been most common.

The arrival of Gageler J prompted the Court in Mills v Commissioner of Taxation[13] to perform its now familiar tradition of allowing the newest judge to author the lead opinion in a case, with which the other members of the Court state a bare concurrence. We have previously noted this practice in respect of each new judge since the arrival of Heydon J.[14] Such decisions are tallied as having been decided by concurrences despite the fact of total unanimity, since the agreement across the Court is nevertheless expressed separately.

The only other case in 2012 in which there were as many opinions as there were judges was very different, with each opinion being substantial and agreement being elusive across the Court. Plaintiff M47/2012 v Director General of Security (‘Plaintiff M47’) is tallied as a matter involving constitutional issues that was decided by all seven judges.[15] Just as with the decision of Momcilovic v The Queen (‘Momcilovic’) in the year before,[16] the level of disagreement in Plaintiff M47 presents particular challenges. In the 2011 study we extrapolated at some length the methodological justification for tallying Momcilovic as decided 2:5 since only the orders favoured by the joint judgment of Crennan and Kiefel JJ entirely accorded with those made by the Court as a whole. We refer readers to that discussion as needed.[17]

Plaintiff M47 is another case in which the use of the Court’s orders as the yardstick for measuring the concurrence and disagreement of its individual members results in finding that a majority of the sitting judges are to be regarded as in dissent. Once again, only the orders favoured by Crennan and Kiefel JJ, on this occasion writing separately, entirely accord with those made by the Court as a whole. Of the remainder, Heydon J is most obviously in dissent for he alone amongst his colleagues was not of the opinion that the requirement that an applicant for a protection visa satisfy a public interest criterion was beyond the power conferred by section 31(3) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) and therefore invalid. Justices Gummow and Bell dissented on the validity of the plaintiff’s detention under sections 189 and 196 of the Act, their Honours advocating acceptance of Chief Justice Gleeson’s dissent on the same provisions in Al-Kateb v Godwin.[18] Lastly, the Chief Justice and Hayne J differed from the final orders in their disinclination to answer whether, in making his decision regarding the plaintiff, the Director-General of Security had failed to comply with the requirements of procedural fairness – the rest of the Court finding that he had not. This last distinction may matter little so far as the outcome reached on the other substantive questions, as to which French CJ and Hayne J concur with Crennan and Kiefel JJ, but it is nevertheless a clear departure by the former from the orders reached by the Court as an institution. It is preferable to recognise that disagreement through tallying the case as 2:5 rather than ignore it in order to say it was simply decided 4:3.

Due to the presence of some discussion of constitutional issues, Plaintiff M47 is also amongst those recorded in Table B(II). It was, obviously, the constitutional matter that provoked the most disagreement. However, two other constitutional matters should be noted for featuring almost as many opinions as there were sitting judges – Williams v Commonwealth (‘School Chaplains case’)[19] and J T International SA v Commonwealth.[20]

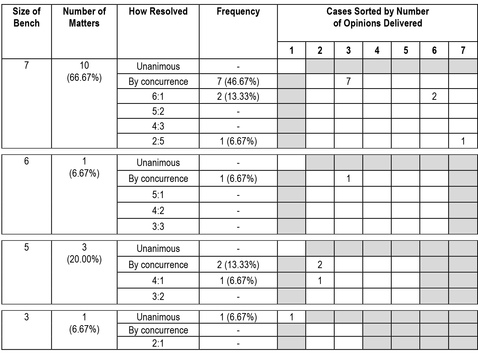

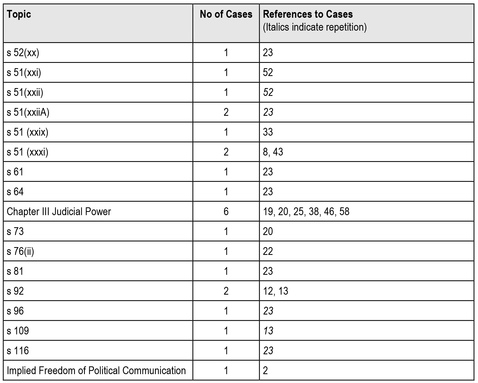

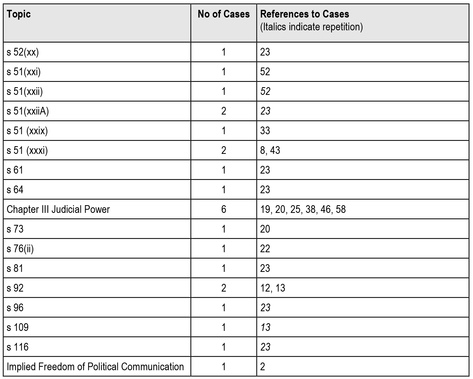

TABLE C – Subject Matter of Constitutional Cases

Table C lists the provisions and aspects of the Commonwealth Constitution that arose for consideration in the 15 constitutional law matters tallied.

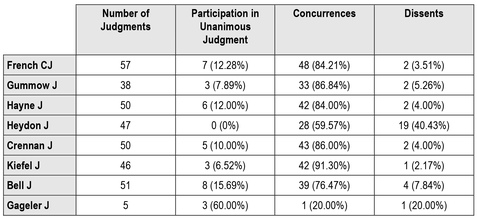

TABLE D(I) – Actions of Individual Judges: All Matters

Table D(I) presents, in respect of each judge, the delivery of unanimous, concurring and dissenting opinions in 2012. Justice Gageler is included in this and all subsequent tables in this Part for the sake of completeness. It is not suggested that any comparative analysis between him and the other members of the Court last year is possible. Justice Gageler replaced Gummow J, whose overall caseload is, as a result, rather lower than those of his colleagues. While a gulf of 19 decided cases lies between Gummow J and French CJ, there have been larger gaps between sitting judges than those which exist between Gummow J and the other members of the Court for the 2012 cases. But even so, it is worth being aware that direct comparison is not as possible in respect of Gummow J.

As it has across these annual studies, the Court continues to be an institution in which the majority of its members maintain very low rates of formal disagreement, while a single judge provides the exception through an extremely high level of dissent. In 2012, Heydon J did not quite match the 45 per cent of opinions he authored in dissent in 2011, but he did not concur notably more often. He dissented in just over 40 per cent of matters in which he delivered a judgment and he was the only member of the Court to not participate in a unanimous opinion. His Honour’s final two years on the Court saw him adopt the outlier position from his colleagues that was previously occupied by Kirby J. Justice Heydon’s individualism over this period has undoubtedly been a major factor in the French Court’s inability to maintain the record levels of unanimity achieved in its first two years – what we have suggested might be known as ‘the Heydon effect’.[21]

The rates of participation in unanimous judgments are highly varied across the table, reflecting the differently comprised courts that heard a range of matters. Interestingly, of those judges who sat throughout the year, Kiefel J had the lowest rate of joining a unanimous opinion after Heydon J, but she also had the lowest dissent rate on the Court. Her Honour’s only minority opinion was jointly authored with Crennan J in Newcrest Mining Ltd v Thornton.[22]

The two dissents tallied for French CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ are from the same cases for each – BBH v The Queen[23] and Plaintiff M47. Regarding the latter, it should be remembered that French CJ and Hayne J dissented only so far as to decline giving a definite answer to the procedural fairness point.

Lastly, unlike other new appointments in recent years, Gageler J has issued his first dissenting opinion very early in his High Court career – in the case of Baini v The Queen[24] in which he was in lone disagreement with the decision of the rest of the Court, writing as one to allow the appeal.

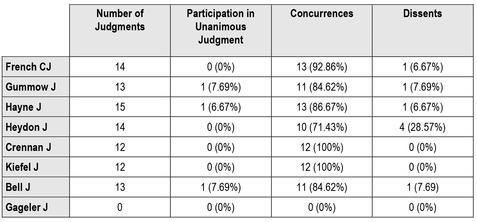

TABLE D(II) – Actions of Individual Judges: Constitutional Matters

Table D(II) records the actions of individual judges in the constitutional cases of 2012. The effect of Plaintiff M47 on these figures is immediately noticeable – it is in that decision that the Chief Justice, Gummow, Hayne and Bell JJ delivered their only dissent in a constitutional case for the year. As noted earlier, Crennan and Kiefel JJ were the only two members of the bench not to disagree with the Court’s final orders in that decision. 2012 was the second year in a row in which those two judges issued no dissent from the Court’s final orders in a constitutional matter.

In addition to Plaintiff M47, the other constitutional matters in which Heydon J dissented were Clodumar v Nauru Lands Committee,[25] the School Chaplains case[26] and J T International SA v Commonwealth.[27]

The single unanimous constitutional matter, a special leave application decided by a bench of three, was noted earlier.

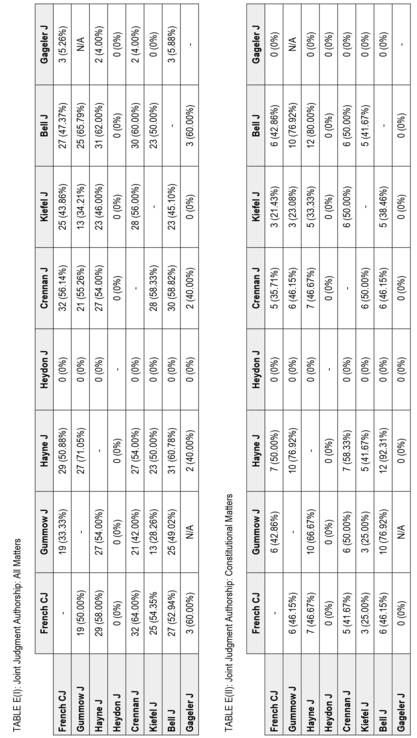

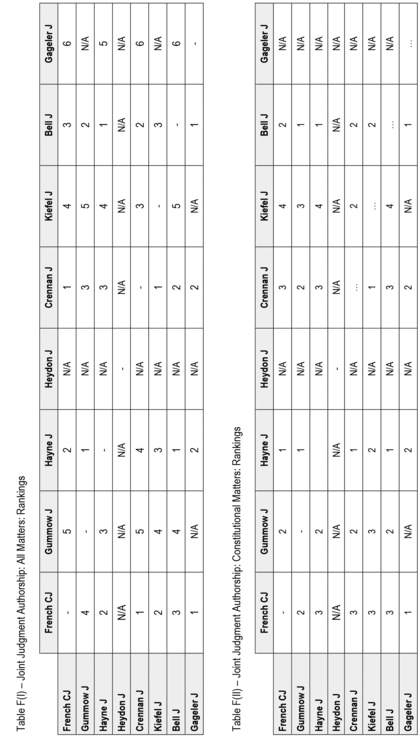

Tables E(I) and E(II) indicate the number of times a judge jointly authored an opinion with his or her colleagues. It should be borne in mind that the judges do not hear the same number of cases in a year. For this reason, the tables should be read horizontally as the percentage results vary depending on the number of cases on which each member of the Court actually sat. That judges do not necessarily sit with each other on an equal number of occasions should also be considered as a factor that limits opportunities for some pairings to collaborate more often. This particularly applied to Gummow J in the 2012 results given his departure before the year’s end.

In respect of the 2011 statistics, we observed that those regular co-authoring relationships that were identifiable ‘may not point to anything particularly important or long-lasting, as, say, the rate of joining by Gummow and Hayne JJ in earlier studies in this series’.[28] That comment holds for 2012. It is notable that the most frequent rate of co-authorship was, for the last time, between those two particular judges. Over 70 per cent of the opinions issued by Gummow J involved Hayne J as a co-author – by far the highest percentage of joining for any judge. However, due to the fewer cases that Gummow J decided, Hayne J himself had higher rates of joining over the whole year with Bell J and then the Chief Justice than he did with Gummow J. Justices Hayne and Bell were each other’s most frequent partner in joint judgments last year. The only other pair that both wrote most frequently with each other over the other members of the Court was French CJ and Crennan J.

The most striking feature of Table E(I) is that Heydon J did not join any other member of the Court in giving reasons for judgment in 2012. His Honour’s high dissent rate is only one indication of the position in which he found himself relative to his colleagues over the last 12 months. The fact that he never wrote with any of them in the almost 60 per cent of cases he decided in which he concurred with the Court’s final orders is even more telling. In 2011 Justice Heydon’s level of joining was significantly lower than that of the other judges but a complete lack of co-authorship is something never observed before in these surveys. Justice Kirby had a reputation for being at odds with his colleagues throughout the Gleeson era, but he always managed to write with some, if not all, of them, on several occasions each year. By contrast, in 2012, Heydon J shared his opinions with no one. That pronounced degree of individualism is unfamiliar to observers of the contemporary court, but it is certainly not without antecedent – Smyth’s empirical study of the Court under Latham CJ (1935–50) found that ‘in the majority of cases ... all of the Justices delivered separate judgments’ and that Starke J, in particular, almost always wrote separately.[29]

Table E(II) reveals joint judgments in constitutional matters. Very few judges partnered with any of their colleagues in more than half of such cases that they decided. The clearest exceptions to this were Gummow, Hayne and Bell JJ, who wrote together much more often – in at least two-thirds of cases decided. The most frequent joining in this context was between Hayne and Bell JJ, the latter writing with the former in all but one of the constitutional matters on which she sat. Every member of the Court delivered at least one sole authored opinion in a constitutional law case last year.

For the sake of clarity, the rankings of co-authorship indicated by Tables E(I) and (II) are the subject of the tables below:

The last term marks the end of an important era on the High Court. The retirement of Gummow J sees the exit from the Court of one of its most consistent majority voices in constitutional law matters over the past decade and a half. He maintained his almost invariable position as a member of the Court’s majority while serving under three Chief Justices until his retirement in late 2012.

Assertions as to the importance or centrality of any individual member of the Court can be difficult to substantiate, but in this case there is ample evidence. Along with other members of the court over his tenure, in particular Gleeson CJ and Hayne J, Gummow J has had an extraordinarily low rate of dissent. With very few exceptions, his judgment has consistently been that of the Court’s, including in the most significant constitutional cases. 2012 was typical in this regard, notwithstanding a rare dissent in Plaintiff M47, which evoked memories of an earlier, equally rare dissent on the same point in Al-Kateb v Godwin.

The regularity with which Gummow J was a member of the Court’s majority and the scarcity of occasions on which he differed from its final orders do not, in themselves, evidence impact and influence, as these might just as equally indicate a follower rather than a leader. However, and to move to a more substantive assessment, a reading of the decisions of the Court over Justice Gummow’s 17 years on the bench demonstrates, without doubt, his intellectual leadership. This is most obvious in the decisions handed down by the Court on the separation of judicial power achieved by chapter III of the Constitution.[30] Justice Gummow has displayed a particular capacity to view this aspect of the Constitution as a rich source of implications and understandings.[31] His decisions are one reason why the interpretation and extension to new situations of chapter III across a long succession of cases has been a dominant feature of constitutional law jurisprudence over recent times.

In earlier eras, the Court’s cases have seen a focus on other aspects of the Constitution, in particular its federal design and the division of power between the Commonwealth and the states. By contrast, with the exception of New South Wales v Commonwealth (‘Work Choices case’)[32] and other decisions, federal questions have less frequently come before the Court this century and even then have often only raised second order constitutional issues. This is changing, with the current Court once again increasingly engaged in federal questions, particularly through its exploration of federal executive power in decisions such as Pape v Federal Commissioner of Taxation,[33] and the School Chaplains case. Despite this, chapter III cases remain in 2012 the most litigated aspect of the Constitution in the High Court.

Justice Gummow’s significant role in the Court’s resolution of constitutional law questions across the spectrum was evident. His views were expressed most often in partnership with Hayne J. Their ability to forge a majority coalition with other judges to decide a matter has been a consistently noted feature in our earlier statistical studies on the work of the Court. Justice Gummow’s capacity to attract the support of colleagues, and so exert influence upon the Court’s decisions is readily apparent from the public record, but was also confirmed by former High Court judge Hon Michael McHugh’s candour in stating that Gummow J was ‘a great judicial politician ... he always had three votes.’[34] It is difficult not to accept that Gummow J has been the Court’s most significant member for much of his time on that bench. With any judicial retirement and new arrival the Court inevitably alters, but some changes matter more than others. The Court without Gummow J undeniably enters a new phase as an institution.

Justice Gummow’s almost unwavering place at the centre of the Court stands in stark contrast to Justice Heydon’s position. Not only was Justice Heydon’s rate of disagreement last year once again comparable with the higher results achieved by Kirby J, the Court’s ‘great dissenter’ during the early years of his tenure, but in 2012 he did not co-author an opinion with any of his colleagues even once. This speaks of a level of judicial isolation not before seen in these statistical surveys.

Justice Heydon’s role as an outlier was not evident in his early years on the Court. It became a marked feature of the Court around the time that French CJ joined the bench. This change in leadership saw other shifts in the dynamics of the Court, including fewer instances of Gummow and Hayne JJ writing together in joint judgment. Nonetheless, unlike Heydon J, those judges adapted to the Court’s changed composition in a way that saw them retain their frequent position among its majority.

By contrast, as he approached his retirement in February 2013, Heydon J deliberately adopted the practice of sole authoring his opinions, virtually ensuring a diminished level of agreement with his colleagues. The publication, coinciding with his departure from the Court, of a lecture that Justice Dyson Heydon delivered to various United Kingdom audiences at the outset of 2012, makes it perfectly clear that his isolation was no accident. Nor, necessarily, was it borne of a disinclination of the rest of the Court to join with him. It was instead the manifestation of a principled stance that Heydon J developed over the course of his judicial career about deliberation and decision-making.[35]

In his speech, and subsequent paper titled ‘Threats to Judicial Independence: the Enemy Within’,[36] Justice Heydon described how the internal dynamic of an appellate court, particularly an emphasis upon achieving institutional consensus, may compromise the intellectual independence of its members, the transparency of its decision-making, and the quality of its judgments. Unlike the practices of the political arms of government, Justice Heydon insisted that ‘compromise is alien to the process of doing justice according to law’.[37]

Revealingly, Justice Heydon commented on the way in which the judges on a multi-member court may attempt to exert influence over each other and the various institutional processes that facilitate this. With the goal of having the Court give unanimous guidance or speak with one institutional voice, he reported that:

Guileful blandishments could be employed – charm, flattery, humour and elaborate but insincere displays of courtesy. The message might be transmitted that those who disagree should say they agree. That is, polite or jovial invitations might be made to tell lies.[38]

At the same time, Justice Heydon opines that ‘excessively dominant judicial personalities’ may be working to shape the Court’s decision in idiosyncratic ways.[39] Justice Heydon asserted that the presence of such personalities ‘in conjunction with judicial herd behaviour can cause grave dangers to arise from the now fashionable judicial conferences’.[40] The obvious danger is that some judges allow themselves to be co-opted to the views of others. But additionally, ‘seduced by suave glittering phrases’ of the one or various forceful ‘personalities’, the Court may be led ‘further and further from the parameters of the public debate between bench and bar’ towards questions of greater interest to particular judges.[41] The Court ends up delivering poor justice to the parties and general pronouncements of law unrefined by the processes of the common law adversary tradition.

Justice Heydon prefaced his remarks with a caveat that he ‘must not be taken to be speaking about the actual behaviour of any particular court of which the author has been a member’.[42] But it is hard to disconnect his comments from the observable pattern of decision-making on the High Court during his tenure, in which, first Kirby J, and then he himself regularly wrote alone beside the joint opinions of their colleagues. Indeed, corroborating Justice Heydon’s account, the Hon Michael Kirby once complained that most of those opinions were ‘written by the same two individuals, joined in by the rest, without change’.[43] And it is impossible not to place these views alongside those quoted above from the Hon Michael McHugh regarding the regularity with which Gummow J was able to attract support for his views from his colleagues on the bench.

Just as the retirements from the High Court in the last half of 2012 and first half of 2013 mark important endings for the Court, so too do they open up new avenues. Despite the warnings sounded by Justice Heydon about the attendant risks, it may be anticipated that the space left by Gummow J on the Court will provide fresh opportunities for its judges to convince their peers as to the different directions it might take and new interpretations of the Constitution. The Court’s newest members, Gageler and Keane JJ, will no doubt play an important part in this.

The notes identify when and how discretion has been exercised in compiling the statistical tables in this article. As the Harvard Law Review editors once stated in explaining their own methodology, ‘the nature of the errors likely to be committed in constructing the tables should be indicated so that the reader might assess for himself the accuracy and value of the information conveyed.’[44]

The following cases involved a number of matters but were tallied singly due to the presence of a common factual basis or questions:

No case was tallied as a multiple number of matters in this study.[45]

* Professor and Director, Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales.

** Anthony Mason Professor, Scientia Professor and Foundation Director, Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales; Australian Research Council Laureate Fellow; Barrister, New South Wales Bar. We thank Harkiran Narulla for his assistance in the preparation of this article.

[1] See Andrew Lynch, ‘Dissent: Towards a Methodology for Measuring Judicial Disagreement in the High Court of Australia’ (2002) 24 Sydney Law Review 470, with further discussion in Andrew Lynch, ‘Does the High Court Disagree More Often in Constitutional Cases? A Statistical Study of Judgment Delivery 1981–2003’ (2005) 33 Federal Law Review 485, 488–96.

[2] Andrew Lynch, ‘The Gleeson Court on Constitutional Law: An Empirical Analysis of Its First Five Years’ [2003] UNSWLawJl 2; (2003) 26 University of New South Wales Law Journal 32; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2003 Statistics’ [2004] UNSWLawJl 4; (2004) 27 University of New South Wales Law Journal 88; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2004 Statistics’ [2005] UNSWLawJl 3; (2005) 28 University of New South Wales Law Journal 14; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2005 Statistics’ [2006] UNSWLawJl 21; (2006) 29(2) University of New South Wales Law Journal 182; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2006 Statistics’ [2007] UNSWLawJl 9; (2007) 30 University of New South Wales Law Journal 188; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2007 Statistics’ [2008] UNSWLawJl 9; (2008) 31 University of New South Wales Law Journal 238; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2008 Statistics’ [2009] UNSWLawJl 8; (2009) 32 University of New South Wales Law Journal 181; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2009 Statistics’ [2010] UNSWLawJl 12; (2010) 33 University of New South Wales Law Journal 267; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2010 Statistics’ [2011] UNSWLawJl 42; (2011) 34 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1030; Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2011 Statistics’ [2012] UNSWLawJl 33; (2012) 35 University of New South Wales Law Journal 846.

[3] The data was collected using the 62 matters listed on AustLII <http://www.austlii.edu.au> in its High Court database for 2012. One matter, Lee v Commonwealth [2012] HCA 62; (2012) 293 ALR 534, was eliminated from the study, having been determined by French CJ sitting alone. For further information about that and other decisions affecting the tallying of 2012 matters, see the Appendix – Explanatory Notes at the conclusion of this article.

[4] The issue of the number of constitutional matters decided by the Court in recent years was discussed in Lynch and Williams (2009), above n 2, 183–4.

[5] The arguments against using a further refinement, such as use of a qualification that the constitutional issue be ‘substantial’, were made in Lynch and Williams (2005), above n 2, 16.

[6] A good example is the case of Stanford v Stanford [2012] HCA 52; (2012) 293 ALR 70 in which the challenge by the plaintiff to the scope of ss 51(xxi) and (xxii), as settled in Fisher v Fisher [1986] HCA 61; (1986) 161 CLR 438 was rejected, and that earlier decision affirmed, without much elaboration.

[7] Stephen Gageler, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2001 Term’ [2002] UNSWLawJl 8; (2002) 25 University of New South Wales Law Journal 194, 195.

[8] Lynch and Williams (2008), above n 2, 240.

[9] [2012] HCA 38; (2012) 246 CLR 251.

[10] All percentages given in this table are of the total number of matters (61).

[11] All percentages given in this table are of the total number of constitutional matters (15).

[12] The case is Pilbara Infrastructure Pty Ltd v Australian Competition Tribunal [2012] HCA 36; (2012) 246 CLR 379.

[13] [2012] HCA 51; (2012) 293 ALR 43.

[14] Lynch and Williams (2008), above n 2, 243; Lynch and Williams (2010), above n 2, 274.

[15] [2012] HCA 46; (2012) 292 ALR 243. The justification for tallying this case as a constitutional matter arises by reason of the comments made by Gummow J and, most particularly, Heydon J concerning the legality of the plaintiff’s detention under ss 189 and 196 of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth).

[17] Lynch and Williams (2012), above n 2, 852–4.

[18] [2004] HCA 37; (2004) 219 CLR 562.

[19] [2012] HCA 23; (2012) 288 ALR 410.

[20] [2012] HCA 43; (2012) 291 ALR 669.

[21] Lynch and Williams (2012), above n 2, 856.

[22] [2012] HCA 60; (2012) 293 ALR 493.

[23] [2012] HCA 9; (2012) 245 CLR 499.

[24] [2012] HCA 59; (2012) 246 CLR 469.

[26] [2012] HCA 23; (2012) 288 ALR 410.

[27] [2012] HCA 43; (2012) 291 ALR 669.

[28] Lynch and Williams (2012), above n 2, 859.

[29] Russell Smyth, ‘Explaining Voting Patterns on the Latham High Court 1935–50’ [2002] MelbULawRw 5; (2002) 26 Melbourne University Law Review 88, 106, 108.

[30] See, eg, the judgments and joint judgments of Gummow J in Kruger v Commonwealth (‘Stolen Generations case’) [1997] HCA 27; (1997) 190 CLR 1; Fardon v A-G (Qld) [2004] HCA 46; (2004) 223 CLR 575; Forge v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2006] HCA 44; (2006) 228 CLR 45; Gypsy Jokers Motorcycle Club Inc v Commissioner of Police (2008) 234 CLR 532; Thomas v Mowbray [2007] HCA 33; (2007) 233 CLR 307. Compare his rare dissent in Al-Kateb v Godwin [2004] HCA 37; (2004) 219 CLR 562.

[31] See, eg, his judgment in Kable v DPP (NSW) [1996] HCA 24; (1996) 189 CLR 51 and his judgments in the cases that followed, such as International Finance Trust Co v New South Wales Crime Commission (2009) 240 CLR 319.

[32] [2006] HCA 52; (2006) 229 CLR 1.

[33] [2009] HCA 23; (2009) 238 CLR 1.

[34] Lynch and Williams (2009), above n 2, 191.

[35] In this regard, see also J D Heydon ‘Varieties of Judicial Method in the Late 20th Century’ [2012] SydLawRw 11; (2012) 34 Sydney Law Review 219 (especially 224).

[36] J D Heydon, ‘Threats to Judicial Independence: The Enemy Within’ (2013) 129 Law Quarterly Review 205.

[37] Ibid 221.

[38] Ibid 209.

[39] Ibid 215.

[40] Ibid 217.

[41] Ibid 219.

[42] Ibid 205.

[43] A J Brown, Michael Kirby – Paradoxes and Principles (The Federation Press, 2011) 400.

[44] Louis Henkin, ‘The Supreme Court, 1967 Term’ (1968) 82 Harvard Law Review 63, 301–2.

[45] The purpose behind multiple tallying in some cases – and the competing arguments – are considered in Lynch (2002), above n 1, 500–2.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2013/19.html