University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

SOVEREIGNTY AS GOVERNANCE:

AN ORGANISING THEME FOR AUSTRALIAN

PROPERTY LAW

PAUL BABIE[*]

Perhaps the best-known and most succinct, but most misrepresented statement of the meaning of property comes from Sir William Blackstone’s Second Book of the Commentaries on the Laws of England:

There is nothing which so generally strikes the imagination, and engages the affections of mankind, as the right of property; or that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the right of any other individual in the universe.[1]

Of course, what it gained in succinctness, Blackstone’s statement lost in accuracy, or, at least, in the way it has been used by others; for Blackstone never meant this statement to represent a full account of all that property was. The way in which most others ever-after have portrayed Blackstone’s words is, at best, inaccurate and, at worst, disingenuous; property is nothing like the absolutist picture painted by an uncritical acceptance of Blackstone’s pithy quotation.[2] And, what is more, Blackstone not only knew it, but spent the remainder of the Second Book of the Commentaries explaining why. In short, Blackstone’s work in Of the Rights of Things displays the wonderful complexity of property as being both individual rights and obligations to the wider community.

Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld would later capture this complexity, first revealed by Blackstone, in the case of legal relationships generally, in the notion of ‘jural opposites’;[3] Tony Honoré still later would refine Hohfeld, in the case of property specifically, in 11 ‘incidents’ of ownership, which included not only the rights typically associated with property – use, exclusivity and alienability – but also the limitations that any fully-fledged legal system imposes on the rights conferred by property.[4] Recent scholarship gives the lie to those who would use Blackstone’s words to present property as nothing more than the rights enjoyed by the individual, as, indeed, simply individualist and absolutist.[5] To do otherwise is to do a grave disservice to Blackstone, whom the very scholars who misuse his work claim to venerate.

Yet, there is something in the simple, absolutist view of Blackstone’s account of property that remains, in fact, very accurate: property is a grant of power, a state-conferral upon individuals of the ability to control the use of goods and resources according to personal tastes and preferences (typically referred to as ‘self-seekingness’), and to exclude others from any such use. In a seminal, but today largely overlooked, article written in 1927, Morris Cohen powerfully captured this truth by making the simple, but entirely accurate claim that the conferral of power engendered in property is, in fact, nothing less than a state grant of sovereignty to the individual said to hold property.[6]

By drawing upon this traditionally public law concept to describe property, Cohen at once makes clear what property is, whilst simultaneously ‘blurring’ the traditional boundary drawn between public and private law. Cohen argues that the public–private divide was, at the time he wrote – and it continues to remain so today – one of the fixed divisions of the jural field, dating as far back as the Roman division between dominium – the rule over things by the individual – and imperium – the rule over all individuals by the prince.[7] Still, Cohen continues, while Austin cast serious doubt on the classical distinction between public and private law, [8] some legal traditions extant at, or emerging very nearly after, the time of the Roman law, such as early Teutonic law, the law of the Anglo-Saxons, Franks, Visigoths, Lombards and other tribes, and even feudal tenurial law, made no such distinction.[9] The blurring of this divide, then, as far as property is concerned, has been with us for quite some time.

As a tool for use in the analysis of property, however, the Roman distinction between dominium and imperium retains its usefulness, notwithstanding the conceptual ‘blurring’ in the case of property. While both comprise a form of sovereignty, the real distinction lies in who holds the power encapsulated by each. In the case of property, dominium is the grant of power in the form of rights conferred by the state upon the individual, of which there are three main types: those which protect economic productivity, those which protect privacy, and those which protect social utility. In each case, the benefit of the right inures to the individual.[10] Cohen concludes that:

the law of property helps me directly only to exclude others from using the things which it assigns to me. If then somebody else wants to use the food, the house, the land, or the plow which the law calls mine, he has to get my consent. To the extent that these things are necessary to the life of my neighbor, the law thus confers on me a power, limited but real, to make him do what I want.[11]

And Cohen found, writing in 1927, that there were a number of areas where the state was expanding this power, this sovereignty, this dominium conferred upon individuals; the power of the owner over labour being the most significant.[12]

And in the course of the state expanding that power, Cohen argued, one must not lose sight of the fact that dominium over things also constitutes imperium over people; the greater the protection accorded to the individual, the greater the possibility that choices exercised pursuant to that power will have consequences, both positive and negative, for others.[13] Focusing on labour law, Cohen found that the ownership of machinery also determined future distribution of goods among people.[14] Today we can see more of what Cohen found, but in different aspects of modern life. Every choice we make also affects the course of the lives of others. Using what I own, for instance, can and does have environmental consequences for people all over the earth.[15] Cohen also recognised something that is significant still today:

those who have the power to standardize and advertise certain products do determine what we may buy and use. We cannot well wear clothes except within lines decreed by their manufacturers, and our food is becoming more and more restricted to the kinds that are branded and standardized.[16]

And think about this: I may choose green power, but if no corporation produces it, to say I have that choice is hollow. In short, concludes Cohen, in property ‘we have the essence of what historically has constituted political sovereignty.’[17]

Yet, the very point Cohen was making was that the Blackstonian view was not correct. The sovereignty conferred by the state upon the individual is not the end of the story of property, as those who misuse Blackstone might think, or at least want us to think. If the individual has political sovereignty, in the form of both dominium over things and imperium over people, it becomes necessary to consider the other side of the equation: what power has the state to stop individuals exercising the sovereignty granted to them in ways that may harm the greater social good, or the general welfare?[18] Cohen argues, in order to avoid chance and anarchy, that the state should do quite a lot: ‘[t]his profound human need of controlling and moderating our consumptive demands cannot be left to those whose dominant interest is to stimulate such demands.’[19] For ‘[n]o community can view with indifference the exploitation of the needy by commercial greed.’[20]

What we can take away from Cohen is simply this: that the use of a public law concept – sovereignty – captures what private law property means, and does so far more succinctly than a misuse of Blackstone’s words can. Property is the power, granted by the state to individuals so that they can protect their interests by controlling both things and others; in this sense, it mirrors the political understanding of sovereignty, the power of the state to protect the interests of the community and the general welfare.

This is not abstract theorising, for the conclusion that sovereignty as a concept is not merely a reference to the public law sphere when applied to property law produces two further questions. First, in conceiving of property law in Australia, to what extent do we consider the totality of what property is, based upon Cohen’s analysis of the individual’s and the state’s sovereignty? Do we consider property to be absolutist, giving the individual unfettered power over a thing, in the way that an inaccurate use of Blackstone’s ‘sole and despotic dominion’ might suggest, or do we see it as both rights and obligations, the former captured in the notion of the individual’s sovereignty conferred by the state, and the latter in the state’s sovereignty to protect the general welfare? Such questions are significant if we are to understand both the problems that property might create – climate change, the consequences of global finance, poverty and hunger, to name just a few[21] – and the way in which it might be used to prevent such problems and foster solutions to emerging public needs in terms of ecology, social cohesion and the economy (the ‘three domains’ of sustainability).

And, secondly, following from the first question, even if we do see the full picture of property presented by Cohen, do we structure our analysis of Australian property law in such a way as to make clear the role and implications of a nuanced understanding of sovereignty? Moreover, do we do so using a truly Australian approach? In both cases, based upon empirical observation, the answers to these questions are almost always no. This article, though, argues that we ought to be able to answer them in the affirmative. And to do that, what we need, both in the conceiving and in the organising of Australian property law, is a model which allows us to bring to the fore the blurring of the public–private law distinction in the concept of property as it operates in Australia, rather than some other jurisdiction (typically England) and to make obvious the implications of an understanding that sovereignty, in the case of property, is both a public and a private law concept.

The implications of concluding that sovereignty, as applied to property, falls into both the public and the private spheres of law are twofold: it requires, of course, that at the pedagogical level we take account of this blurring of distinctions, and in the context of this article, that we do so in an Australian way. Probably more importantly, though, is the theoretical implication; the conclusion I draw requires us to re-think what we know about property, and in doing so, we will see much more clearly how the various strands of property law, both real and personal, in all its guises, can be drawn together by the concept of sovereignty as utilised by Cohen. Any pedagogical implications, then, become merely suggestions that follow from the theoretical importance of seeing property as sovereignty in an Australian context. Seeing property in that way requires us to make pedagogical changes, but the changes to teaching themselves are not the major thrust – the major thrust is the way we understand property, theoretically, and its ‘Australian-ness’. In short, what is required is a reconceptualisation of Australian property law, pedagogically, yes, but also, more importantly, theoretically.

In three parts, this article seeks to outline how we might achieve the dual objectives of demonstrating the blurring and overlapping of the public–private distinction through the use of the concept of sovereignty in property law, and to do that from an Australian perspective. Part II reappropriates an earlier exhortation of Thomas Penberthy Fry – who taught at the University of Queensland Law School from 1936 until 1948 – to organise Australian property law from a truly Australian perspective.

Part III, drawing upon Peter S Menell and John P Dwyer’s project to reunify the teaching of American property law, argues that the organising theme around which an Australian property law subject might be based is the simple juxtaposition of the power, control, or simply the choice, of the individual to protect oneself through the use and control of resources, balanced against the power, control, or choice, of the state in the pursuit of protecting the general welfare. In other words, the organising theme is the role played by sovereignty, as identified by Cohen, in understanding what property is.

Part IV outlines the practical usefulness of using sovereignty as an organising theme for both understanding and, perhaps more importantly, teaching Australian property law. To demonstrate this, the Part offers five Australian examples which demonstrate how the use of this organising theme might work. While not exhaustive – obviously the entirety of property law would need to be structured according to the organising theme suggested here – the five examples presented demonstrate that if it is Australian property law in which we are interested, then the exercise of identifying an organising theme for it ought to be undertaken from an Australian perspective.

Part V offers some brief concluding reflections on the ‘blurred’ distinction between public and private law in the concept of sovereignty as applied to property law.

Born in Brisbane in 1904, Thomas Penberthy Fry studied at the University of Queensland (BA (Hons), 1926; MA, 1927), the Academy of International Law in The Hague (Diploma, 1928), Magdalen College, Oxford, (BCL, 1929), and the Harvard Law School (SJD, 1931), was admitted to the Queensland Bar in 1931, and combined a varied practice with part-time teaching in social science at the University of Queensland (1932–35) and external examining for the University of Sydney Law School (1932–34). Glimpses of an early interest in the history of Australia, and the way in which that unique history shaped the institutions of government and law in unique and novel Antipodean ways, revealed itself in his becoming Chairman of the Queensland Historical Society’s editorial committee in 1935, and his founding of the Queensland branch of the Australian Institute of International Affairs, the latter of which he became President from 1932–40 and 1947–48. Fry would also serve as Honorary Secretary of the Australian and New Zealand Society of International Law.

Notwithstanding his glittering academic record, and his interest in Australian innovation in government and law, Fry’s advancement in the academy was slow. Appointed Lecturer in the University of Queensland’s new Law School in 1936, Fry taught constitutional law, criminal law, equity, torts, and property and conveyancing law, using ‘“a modified case method of teaching[,] ... prefer[ing] seminars to the traditional lecturing system”; students found him helpful and kind hearted’. Following military service during World War II, Fry returned to Queensland as a Senior Lecturer in 1946, only to resign in 1948 to take charge of the Sydney-based legal research section of the Department of External Territories, where he continued earlier work on, and revision of, the laws of Papua and New Guinea. Sadly, Fry’s contributions to historical and legal scholarship were cut short when he died of a cerebral haemorrhage in 1952.[22]

Many people with whom Fry worked considered him to have an unusual personal style that sometimes gave people the wrong impression. In his biography of Fry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Ian Carnell writes that Fry was felt by some to have ‘led “a rather uncoordinated existence”’; that ‘[b]ecause he “trod on many toes”, his talents did not receive full recognition by [Queensland’s] legal profession’; and that ‘[h]is minister from 1951 [in the Department of External Territories], (Sir) Paul Hasluck, considered him “a singular man with exceptional gifts”, but recognized the degree to which he lacked “worldly practicality”’. [23] We know also, though, that he was progressive in his teaching, looking for new ways to teach the law, using seminar teaching at a time when lectures were almost universally used, and relying on a more collaborative as opposed to a prescriptive style in the classroom. Yet, as progressive as he was, in noting these eccentricities of character, Carnell implies that Fry’s eclectic yet visionary approach may have impeded more rapid career advancement.

Given the singularity of the person, and the brevity of the career, one might be forgiven for thinking that Fry contributed little, both in output and in depth of thought, to the development of an Australian approach to the conceiving and structuring of Australian property law. Yet, Fry’s case represents one of those not-infrequent instances where rank certainly reveals little about the output and quality of the scholarship, if not the impact. We would be mistaken to overlook Fry’s work, for while it has not had the impact it might have had, there is a depth of vision in the great volume of scholarship produced in a short space of time. And it is our loss that he neither gained the rank, nor enjoyed the longevity, such as to allow that quality and breadth to penetrate deeper into the psyche of the emerging Australian legal academy, for his contribution to the way we ought to conceive of Australian law generally,[24] and property specifically, as truly Australian, was and remains revolutionary.[25] It is hoped that this article will serve to introduce Australian property law scholars to the profound potential for reconceiving the organising theme around which property might coalesce. It is here that Fry may make his most profound, albeit long-delayed, contribution to the place of property in the European history of Australia.

Fry simultaneously published Freehold and Leasehold Tenancies of Queensland Land,[26] and its elegant and succinct counterpart and summary, ‘Land Tenures in Australian Law’,[27] in 1946. At first blush, the titles of these two contributions suggest something unexceptional. Many other Australian property law books with similar titles exist, covering similar themes. Each proceeds from the same premise: that Australian property law is in fact English and so, to understand it, these books cover exhaustively the English law of property, both historical and contemporary, reducing Australian contributions and, indeed, innovations, to final paragraphs at best, and footnotes at worst. I well recall my own experience as a law student in Property Law; the first case we read was Attorney-General of Alberta v Huggard Assets Ltd,[28] a decision of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which our professor used solely to make the point that the English law of property was part of the received law of Canada. From there, the subject marched resolutely on through the history and operation of the English law of property, rarely pausing for breath to discuss any Canadian contributions. It was not until my second year of law school, in an elective subject known as Land Titles, that the Torrens title system of registration (an Australian innovation, true, but one adopted by Canadian jurisdictions,[29] thus distinguishing the Canadian law from the English) was even mentioned. Until then, and without that elective, one might have thought that the English law of property was, unadulterated, the law of property in Canada. In Fry’s day, Australian approaches to property law followed much the same pattern as my own experience in Canada. And the Australian approach still follows that pattern today.[30]

Fry took a different tack, pointing out that while its origins lay in English law, Australian law had developed quite extensively from the initial reception of English law; one could therefore say that by 1946 Australian property law was truly Australian. Fry argued that this fact ought to be emphasised. Thus, rather than starting with a case like Huggard, and without drawing on the English history, Fry began by recounting two historical events, well known to Australians of his day, to begin his account of Australian property. Few authors, then or now, would begin in that way, opting instead for a Huggard-like approach. The first event was the 1835 attempt of John Batman to negotiate with the Aboriginal inhabitants of present day Melbourne; while he successfully negotiated the treaty, its efficacy was later rejected as an attempt to obtain an allodial ownership of the subject land,[31] the second the failure of the early ‘squattocracy’[32] in New South Wales to gain, through squatting on land outside the ‘Limits of Location’,[33] an allodial title to land. In other words, for Fry, Australian land law began not with a case like Huggard to show that Australian law was really just the English law, but with a simple, but obvious proposition: that any Australian land tenure relies for its existence on a grant of the state, in this case the Australian Crown.

Fry’s simple proposition seems so obvious to us today that we forget how radical it was in 1946; but the evidence for the shockwaves it would have sent through the Australian legal landscape is found in the fact that while the thesis – especially the Australian Crown origin of all land grants – has been adopted in contemporary scholarship, the origins of that thesis, Fry’s work, seems hardly referred to. Rather, Fry’s argument has disappeared, almost never mentioned in the leading texts and casebooks on Australian property, as if by wilfully forgetting it, one can wipe his contribution away.

Building on Batman and the squattocracy, and while the precise mechanics of the legal consequences attached to the attaining of sovereignty over Australia have since been altered by the High Court in Mabo v Queensland [No 2],[34] Fry identified, almost half a century before the High Court would affirm it as the law of Australia, that the Crown at the time of acquiring sovereignty gained a radical title to all Australian land. As a consequence, ‘[n]o proprietary right in respect of any Australian land is now, or ever was, held by any private individual except as the result of a Crown grant, lease, or licence and upon such conditions and for such periods as the Crown (either of its own motion or at the discretion of Parliament) is or was prepared to concede’.[35] Fry concludes that Australian land law is truly Australian because:

A century of subsequent legislation [following the settling of the date of reception of English law in force in England as 25 July 1828] [36] by the various legislatures of Australia has developed a new system of land tenures in the various Australian states and Territories, so that it is now possible to say, with a very high degree of accuracy, that the constitutional supremacy of Australian Parliaments and the Crown over all Australian lands, as much as the feudal doctrines of the Common Law, is the origin of most of the incidents attached to Australian land tenures. This does not mean, however, that the law as to tenures has suffered an eclipse in Australia. The reverse is the case. Legislation has revitalised and developed it, and has given it an importance in modern Australian land law which it has not had in England at any time since the sixteenth century.[37]

Given that almost a second century has passed since the enactment of the Australian Courts Act 1828 (Imp), with myriad Australian Commonwealth, state, and territory legislation dealing with all aspects of Australian land and property law, Fry’s comment is all the more relevant today than when he wrote in 1946. In other words, Australian land law is more Australian today than it was in 1946, and it was already thoroughly Australian at the time it was written.

Thus, as early as 1946, Fry reminds us that the Australian Crown is the holder of sovereignty as defined by Cohen in the context of property – in other words, the power to control the rights conferred on individuals in property – allowing not only for the creation, on truly Australian, as opposed to English grounds, of sovereignty in individuals, but also for the regulation of the exercise of the power so conferred. Other authors may tell us the same, but only through a lengthy excursus on the nature of the English Crown and feudal law. What, then, of the private law dimension of sovereignty outlined by Cohen – that part that comprises the individual exercises of power, or the sovereignty conferred by the state on individuals? This is the story of those tenures invented in Australia and which represent a truly unique contribution to Australian land law.

The novel Australian land tenures will be considered in greater detail below. For present purposes, it is enough briefly to consider Fry’s work in this area, which represents the logical corollary of the conclusion that the Crown held sovereignty as defined by Cohen. This, in turn, made it possible for the Crown to confer on individuals that same sovereignty, the power of dominium and imperium over any given good or resource. Fry argues that Australian conditions and exigencies required Australian innovations unseen in any other system of property law including, and especially, the English. Taken in conjunction with the fixing of the date of the reception of English law in Australia – 25 July 1828 – Fry concludes that of the possible incidents of tenure that the common law might have attached to freehold grants from the Crown ‘no type of tenure other than free and common socage was ever introduced into Australia as a result of the reception in Australia of the Common Law of England.’[38] Rather, the state, the Crown in Australia, created a range of tenures never known to the law of England, each establishing the power conferred on individuals when they received such a tenure.

Fry canvasses the multitude of novel Australian tenures, beginning with their origin in the power to make Orders in Council in 1846, and the first such Orders issued in New South Wales in 1847 and in Western Australia in 1850.[39] Fry divides these into three broad categories – perpetual tenures, non-perpetual ‘non-convertible’ tenures, and non-perpetual tenures convertible to freehold at the option of the Crown tenant – under each of which are many more sub-classes.[40]

In order to understand precisely what the individual obtains pursuant to one of these novel tenures, Fry

emphasise[s] that it is to the precise terms of each Crown grant, and to the provisions of relevant statutes, and not primarily to generalized rules of the Common Law concerning the incidents of socage tenure, that it is necessary to look in order to ascertain the restrictions in favour of the Crown imposed in the Crown grant upon the Crown tenant’s rights to the land.[41]

In this, Fry captures Cohen’s simple truth that property is a conferral of sovereignty upon an individual:

The undoubted constitutional right of the [Australian Commonwealth, state and Territory] Parliaments to create whatever tenures each think fit has been exercised actively. The result [is that] each state, as Millard has said of New South Wales, is ‘a bewildering multiplicity of tenures’. Gone is the simplicity of the modern English law as to tenures. Gone is the senile impotence of the emasculated tenurial incidents of modern English law. New South Wales and Queensland are in the middle of an historical period in which the complexity and multifarious nature of the laws relating to Crown tenures beggars comparison unless we go back to the medieval period of English land law. The relevant laws in the other states of Australia are perhaps less complex and multifarious, in comparison with those of New South Wales and Queensland; but in no Australian state or dependent Territory are these laws nearly as simple as is the modern English law as to tenures.[42]

And, as we know from Cohen, the state retains sovereignty as well, so as to protect the general welfare and this, too, is evident in the Australian model:

In the feudal era in England, as also in Australia to-day, Parliament and the Crown (as advised by the magnates of the realm in past times and by Cabinet Members in modern times) imposed upon Crown tenants such tenurial incidents as were best calculated to advance the policies thought at any particular time to be appropriate for the purpose of ensuring the safety and prosperity of the realm.[43]

Australia’s property law, then, exhibited a dual sovereignty, as Cohen argued all property law had, and Fry demonstrated how this duality had a truly Australian character. And none of that which Fry wrote almost 70 years ago is any less true of Australian property law today,[44] which makes it all the more strange that our standard accounts of Australian property law today fail to capture this reality identified by Fry. How, then, can we find an organising theme which will draw together the two aspects of sovereignty as concerns property identified by Cohen, and demonstrated by Fry to be operative in Australia? Adapting and modifying the novel approach of two American scholars, Peter S Menell and John P Dwyer, the next section suggests an organising theme for use in Australia.

Over a decade ago, reacting to the lack of cohesion of the teaching of American property law, and to the extent to which ‘property course[s] ha[d] become a bundle of topics that professors can liberally mix and match’ and how it ‘ha[d] devolved into a disparate set of doctrinal areas loosely tied together by their relationship to land’,[45] Peter S Menell and John P Dwyer suggested a common organising theme around which property law could be reunified. Rejecting the Hohfeldian jural opposites as being principally definitional, and ‘[t]he justificatory theories [as] largely dissociated from the richness of real world property institutions’,[46] and reflecting upon the common organising themes found in other doctrinal categories of law, such as private ordering through assent in contracts, default rules for assigning responsibility for accidents in tort, rules for litigating disputes in civil procedure, and justifications and rules for punishing crimes in criminal law,[47] Menell and Dwyer argued that:

there is every reason to believe that the production and allocation of resources continue to represent central problems in modern societies. Ironically, the growing importance of a wider range of resources – beyond simply land – has contributed to the erosion of the intellectual coherence of the property course, and at the same time has illustrated the need for a unifying intellectual framework.[48]

Menell and Dwyer therefore suggest a simple, yet profound approach to a cohesive organising theme: property as governance regimes. For them,

one of the central problems of every society throughout history has been the governance of resources. Land is obviously an important category, and historically, often has been the most important resource, but it is by no means the only important resource, and its relative importance varies over time and across societies.[49]

Obviously, then, there are many different ways in which a society might govern resources, making it necessary to develop a framework that describes how these regimes occur and evolve over time.[50] Thus, for Menell and Dwyer, the organising theme for property can be summarised in a simple phrase, allowing it to stand alongside the organising themes found in the core law school curricula: ‘exploring and comparing the principal institutions for governing resources’ which focuses not only on those governance institutions, but also on the processes underlying their operation.[51]

We might conceive of the organising theme proposed by Menell and Dwyer in a number of ways: some, as we have seen, such as Cohen and the legal realists, critical legal theorists,[52] and property as social relations scholars[53] refer to it as power over resources and people; others more recently have found resonance in the notion of ‘agenda-setting’ concerning the use and control of resources;[54] in earlier work I have called this power simply a choice concerning goods and resources and the lives of others, capturing one of the core themes venerated by liberalism and neoliberalism.[55] In sum, though, each of these – governance, power, agenda-setting, or choice – captures the same organising theme identified by Cohen in the sovereignty which is conferred upon an individual by the state, allowing that individual to control the use of a thing, while ensuring that such use does not bear detrimental outcomes for the common welfare of a society. A governance regime, then, is any system whereby the use of things are allocated to individuals, and which confers upon such individuals the ability to make use of a thing as that individual sees fit, and to exclude others from making use of that thing save for that which is permitted by the individual. Added to this is the ability of the state which so conferred that power to regulate its exercise. In short, a governance regime is the sovereignty which Cohen identified, or the ability to set the agenda for the use of a resource more recently identified, or the ability to choose how a thing is to be used which I have previously identified. Menell and Dwyer’s approach assists in conceptualising any given society’s system of property by allowing seemingly unrelated and disparate methods of treating the allocation and use of goods and resources, tangible and intangible – land, personal property, commercial property interests, security interests, intellectual property, and so on – under the umbrella of those systems which, at their core, allow an individual to make use of a thing, whatever it is, to exclude others from making use of it, and which allows the state to control the way in which that use occurs.

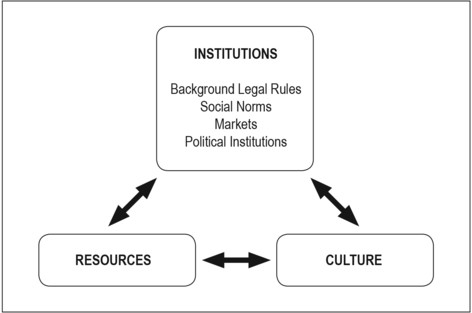

While a governance regime may emerge in any given society in myriad ways (consider the difference in the way Indigenous land use regimes and the English tenurial common law developed), Menell and Dwyer identify three common elements in every case: the resources in question, the culture in which those resources are used and how they are used, and the resultant institutions that emerge (which themselves include four elements: background legal rules, social norms, markets, and political institutions). Together these three common elements in the emergence of a governance regime Menell and Dwyer call the ‘triadic relationship’ which, rather than flowing in a linear direction from either resources or culture to the institutions of the regime, operates through dynamic interactions and feedback loops operating between the three elements of the relationship, so that ‘[o]ver time, resources and culture not only determine governance structures, but governance structures also affect the resources base and culture’.[56] (Menell and Dwyer diagrammatically demonstrate this process: see Figure 1)

Figure 1: The Triadic Relation[57]

Property therefore coalesces around an organising theme of governance regimes, at its core comprising the juxtaposition of Cohen’s individual and state sovereignty. Seen this way, any system which involves the distribution and control of resources can be united under the banner of property law, both doctrinally and pedagogically. The next section applies the organising theme of sovereignty, both individual and state, to the Australian context.

At its simplest, property is the system used by liberal democratic systems to parcel out, or allocate, control over scarce resources among the members of a society and, importantly, to justify that parceling out. Without justification, any political theory founders as the inevitable inequality in the parceling out, or allocating, of control over resources leads just as inevitably to a constant state of friction and unrest; life for most people coming to approximate Hobbes’ summary of the state of nature – ‘solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short’.[58] Yet, a focus on justification alone has led to an organisation and teaching of property law, in most societies, and especially those in common law jurisdictions,[59] in such a way that merely catalogues all the ways that a society might parcel out a given resource and its control, without ever searching for what unites the different ways in which this has been done, and the different resources, tangible and intangible, to which this has been done.

Menell and Dwyer, though, as we have seen, criticise this haphazard approach, arguing instead for a unifying organising theme coalescing around the idea of the parceling out of control over goods and resources, which they refer to as governance or sovereignty, drawing of course upon the earlier, and sharper, focus of Cohen on sovereignty. For Menell and Dwyer, such an approach allows property law to join its private law counterparts, each having their own organising themes: private ordering through assent in contracts; default rules for assigning responsibility for accidents in tort; rules for litigating disputes in civil procedure; and justifications and rules for punishing crimes in criminal law.[60] We can see these organising themes at work in every other Australian private law area[61] – and this lends not only credibility to the area, but also a sense of certainty and solidity to the argument that these are, in fact, doctrinal categories of law. While property clings to its place as a legitimate private law category, this position is tenuous, given its disorganised structure.[62] Australia cannot claim to be any better in this respect.

Yet, as we have seen in Fry’s seminal work, while Australian property law may suffer from the lack of an organising theme, it certainly does not lack a historical development in an Australian way, unique to the circumstances and conditions that have pertained here since first European settlement.[63] For whatever reason, though, since Fry wrote in the mid-20th century, with few exceptions,[64] what we tend to find is a reversion to an earlier, pre-Fry approach, narrowly emphasising the Englishness of Australian property law which, in almost all texts, means land law, to the exclusion of Australian content – with the possible exception of the Torrens system – adding any mention of Australian innovation almost as an afterthought.[65] Disappointingly, just as Menell and Dwyer show in the American context, we find Australian property law taught as a loose collection of largely English subtopics without any unifying theme. Such an approach is helpful neither to practitioners or judges, nor to students. Rather than an Australian property law, as it pertains to the gamut of Australian resources which property law governs, one practising or studying ‘Australian property law’ might be forgiven for thinking that what that meant was the land law of a part of England.

Proposing an organising theme, then, for Australian property law, one which draws together the disparate approaches to the parceling out of the governance or sovereignty over all goods and resources in Australia, whatever they might be, tangible and intangible, would add a coherency currently lacking. It would do this by demonstrating that however it is accomplished, property is the allocation of control, governance, or sovereignty, over scarce Australian goods and resources. This, in turn, would allow property law to join other private law categories where an organising theme helps not only those in the academy, but also practitioners, judges and students make sense of the law in that area, such as we find in contracts, tort, or criminal law. The use of sovereignty as a means of organising Australian property law would, in other words, go some way toward overcoming the notion that Australian property law was really English law with some additions, that it applied only to land, and that it was organised only in the sense of justifying allocations of control over land to a select few. It would begin with the uniqueness of Australian property law, and demonstrate how that uniqueness can be seen in the various ways that governance or sovereignty have been conferred on individuals to meet Australian circumstances and conditions, both physical and social.

What would this achieve in the classroom? Something quite important. Australian law students would see, through explicitly Australian examples, that property is about governance, or sovereignty, conferred by the state upon individuals or groups, to choose how to make use of the gamut of Australian goods and resources, tangible and intangible. This point is often lost in a classroom focusing solely on the legal history of English land law, which often confuses students in its mix of the doctrines of tenure and estates, the role of land as value, and the development of equity, with some Torrens thrown in for good measure. How sovereignty might be derived, and how it might be lost, by the state and by the individual, would not only make sense of these confusing aspects of English legal history, but also explain the many innovations that have come about in 200 years of Australian legal development. This would also allow students to see more clearly, and starkly, the practical role played by, and the impact of, this parceling out of governance as an agent of social change, rather than simply a set of arcane, historical, black letter rules. What is more, seen from the perspective of conferring or removing sovereignty, the English historical examples that currently tend simply to confuse students, might rather take on added relevance and value when taught in an Australian context.

The remainder of this Part, in an attempt to demonstrate the importance of using sovereignty and governance as an organising theme in the Australian context, presents five Australian examples, one drawn from the governance of information – knowledge and ideas – and the other four based upon land and its constituent resources. This selection of examples responds to Menell and Dwyer’s concern that an organising theme ‘must provide a conceptual framework that applies to the full panoply of resources’.[66]

This part presents five examples, drawn from contemporary Australian law, that serve to illustrate that Australian property law can be organised around the theme of governance institutions (comprising Cohen’s underlying sovereignty of the individual and the overarching sovereignty of the state). These examples also demonstrate the historical and cultural influences in relation to resources that produced the relevant property institution, and which continue to develop as a result of the dynamic feedback loops identified by Menell and Dwyer. The examples include one that involves intellectual property, and four that involve land and its constituents: the human genome in the case of the former, and Indigenous and post-European land use regimes, minerals, and water, in the case of the latter.

From the time of Plato, political theory posited the notion of self-ownership; this has run through Hegel and up to our own time in the pluralist account of property posited by Steven Munzer.[67] Recent cases on both sides of the pacific, however, make some inroads into the way in which we view the ownership of isolated human genetic materials.

The patentability of genes has been a controversial issue in Australia and abroad for some time, particularly over the last two decades. In the last 10 years, the Australian Law Reform Commission,[68] the Advisory Council on Intellectual Property,[69] the Senate Community Affairs References Committee,[70] and the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee,[71] have all inquired into the issue of the patentability of genes in Australia and issued comprehensive reports. The Australian Government, in November 2011,[72] issued a report responding to a number of these inquiries, and subsequently implemented many of the recommendations in the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth).

Against this background, the Federal Court recently decided Cancer Voices Australia v Myriad Genetics Inc,[73] and, in doing so, for the first time in Australia considered the validity of a human gene patent. This, in turn, provides an Australian example of how isolated human genetic material, and knowledge and methods developed in relation to it, may become the subject matter of a regime of governance created by the state, and over which the state continues to exert control over the manner in which individuals may exercise the power so conferred by the state. Such examples of sovereignty are rarely considered as part of the broader fabric of Australian property law, yet they are nonetheless important to understanding the law of property as it works in Australia,[74] and using Menell and Dwyer’s organising theme, and Fry’s admonition to see the ‘Australian-ness’ of property law, these alternative regimes ought to be included.

The patent held by Myriad Genetics in Australia related to, among other things

methods and materials used to isolate and detect human breast and ovarian cancer predisposing gene (BRCA1), some mutant alleles of which cause susceptibility to cancer, in particular, breast and ovarian cancer.[75]

Mutations in the BRCA1 gene, first isolated in 1994,[76] are believed to account for around 45 per cent of hereditary breast cancer, and 80 per cent of hereditary cancers involving both breast and ovarian cancers.[77] The patent thus creates a monopoly on the screening of, and genetic testing for, the predisposing breast-and-ovarian-cancer gene BRCA1.

Since the BRCA1 gene is a naturally occurring part of human DNA, the question considered in Myriad Genetics was whether

a valid patent may be granted for a claim that covers naturally occurring nucleic acid – either deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or ribonucleic acid (RNA) – that has been ‘isolated’.[78]

The disputed patent claims concerned ‘isolated’ nucleic acid – that is, nucleic acid removed from its normal cellular environment – and the challenge was that these did not claim a manner of manufacture as required by the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) s 18(1)(a). Cancer Voices Australia argued that the patent claims concerned isolated nucleic acid that was ‘not materially different to nucleic acid that occurs in nature’, and that naturally occurring DNA and RNA were ‘products of nature’, even when isolated, and so were not patentable. [79] Myriad Genetics contended that it had claimed a ‘product that consists of an artificial state of affairs, providing a new and useful effect that is of economic significance’, and so the patents were valid.[80]

In his judgment, Nicholas J made a number of important points. The disputed claims related to a chemical composition.[81] The claims were to tangible materials, rather than to genetic information per se, and so the patents could not be infringed by mere reproduction of the relevant DNA sequence.[82] Additionally, the claims were limited in scope to the isolated chemical compositions, and so did not concern naturally occurring DNA or RNA in situ; that is, not to the sequences as they are found naturally in the human body.[83]

Based on a detailed survey of the leading High Court decision in the NRDC Case and related cases,[84] Nicholas J found that a composition of matter may be a claim as to a ‘manner of manufacture’ if it ‘consists of an artificial state of affairs, that has some discernible effect, and that is of utility in a field of economic endeavour’.[85] In this case, the necessary legal inquiry did not entail a consideration of whether the particular composition was a ‘product of nature’, or whether it was ‘markedly different’ to something that already exists in nature.[86] The patentability, according to Nicholas J, did not even depend on any chemical change having been made to the composition as a result of its isolation. The isolated nucleic acid could have exactly the same structure and composition as it does when found in situ in human cells.[87]

Three principal considerations led Nicholas J to hold that an isolated nucleic acid constituted an artificial state of affairs, even when it had an identical chemical composition and structure to the same nucleic acid found in human cells. First, the High Court in the NRDC Case had defined the concept of a manner of manufacture very broadly. Secondly, the isolation of a nucleic acid involves the extraction and purification of the nucleic acid, and so it is a product of human intervention. Thirdly, the process of isolation required immense research and intellectual effort. It would be ‘inconsistent with the purposes of the Act’, Nicholas J wrote, and the broad language of the High Court in the NRDC Case, for the result of the considerable labour, skill and effort employed in the isolation of a nucleic acid not to be rewarded by the grant of a patent.[88]

The decision is consistent with the longstanding practice of the Australian Patent Office to grant patents for isolated nucleic acids.[89] Yet, the decision for the first time provides judicial confirmation of this practice.

In concluding, Nicholas J reserved the possibility of the invalidity of the patent on some other ground, as the challenge in this case was limited only to whether the claims were in relation to a manner of manufacture.[90] Moreover, Nicholas J stressed that there is ‘no doubt that naturally occurring DNA and RNA as they exist inside the cells of the human body cannot be the subject of a valid patent’. The disputed claims in the patent concerned only ‘naturally occurring DNA and RNA which [had] been extracted from cells obtained from the human body and purged of other biological material with which they were associated’.[91]

The case has attracted considerable media coverage, and there has been considerable criticism of the patentability of genes as a matter of public policy.[92] The second applicant in the case, Ms Yvonne D’Arcy, a two-time breast cancer and one-time ovarian cancer survivor, has decided to appeal the decision to the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia. [93 ]The United States Supreme Court has already decided the issue, finding that isolated DNA is not patentable.[94] As such, the expected judgment of the Full Federal Court, and of developing jurisprudence in this area generally, will continue to excite debate as to the patentability of human genes across the globe. For our purposes, though, the interest in the issue raised by these cases only serves to highlight that governance regimes over isolated human genetic material and knowledge and methods developed thereon are theoretically possible and that both the state, through its regulation not only of the very existence of a patent, but also over the exercise of the rights conferred under it, and the individual, through the exercise of those rights, are involved in the relationship that comprises that regime.

As is now well-known, upon the European settlement of Australia in 1788, the continent was regarded as terra nullius, and as such, the absolute title to all land in Australia was acquired by the Crown.[95] This was the legal position for more than 200 years in Australia. The result of this notion was that the system of land tenures in operation in Australia was inconsistent with the recognition of any Indigenous or native title rights to Australian land. As noted earlier, though, in Mabo,[96] decided in 1992, Brennan J acknowledged that:

The common law of this country would perpetuate injustice if it were to continue to embrace the enlarged notion of terra nullius and to persist in characterizing the Indigenous inhabitants of the Australian colonies as people too low in the scale of social organization to be acknowledged as possessing rights and interests in land.[97]

The decision went on to recognise the existence of native title in Australia, a type of beneficial title to land which depends on the traditional occupation of, or connection with, the land by Indigenous people.[98] And this allows us to see another seldom considered, but just as significant example of a governance regime for the use and control of resources: those regimes that pre-date European settlement. A traditional approach to property, one focusing on land alone, and the way in which English law dealt with land, obscures our ability to see these examples.

But such examples exist, and we increasingly find new and expanded evidence of them. The idea of pre-settlement Australia as being ‘unsettled’ or ‘untamed’ by Indigenous peoples has been progressively eroded over time. Bill Gammage, in a landmark 10-year study, describes in great detail the remarkable way in which Indigenous Australians managed the Australian landscape prior to 1788; exploring in depth the Indigenous practice of carefully and systematically using fire to control and manage the pre-1788 Australian landscape – what the great archaeologist Rhys Johns called ‘fire-stick farming’.[99]

This understanding of Indigenous Australians as active users, managers, and owners of land prior to Anglo-Australian settlement, coupled with the recognition by the High Court in 1992 of native title to land, recognises that it is not only the post-European history of Australia that provides examples of governance regimes over the use and control of resources. What we find in Gammage’s work is that long before Europeans ever arrived on this continent, an extensive and sophisticated governance regime existed for the use and control of land and other naturally occurring resources. This is often overlooked in property law subjects, but Menell and Dwyer’s organising theme, and Fry’s insistence that we look at Australian property law, allows us to see these alternative, but no less Australian, examples in our own history.

And more than simply seeing such examples, considering them to be part of the broad spectrum of governance regimes which comprises Australian property law, allows us to advance some radical arguments. Of course, it is difficult to fit this example into the schema suggested by Cohen, in the sense of property constituting sovereignty conferred by the state on the individual (or a group of them). And no attempt is made here to suggest that the pre-contact position of Australia’s Indigenous peoples involved the existence of, or indeed, the need for, any conferral of sovereignty by any state whatsoever. Clearly, that position involved the conferral of an internal form of sovereignty, not dependent on any external source or power. More importantly for present purposes, though, is the reality that whatever system existed prior to English settlement, it did constitute a governance regime in the sense that it involved the control of a resource, in this case land. Still, following English settlement, as problematic as it has been for Australia’s Indigenous peoples, the holding in Mabo has resulted in the existence of native title, as part of Australian law, as the recognition of the conferral of sovereignty by the state upon Indigenous peoples for the use and control of those lands which might previously have been held pursuant to a solely Indigenous governance regime.[100]

Importantly for Australia’s Indigenous peoples, this conclusion reveals that a form of property did in fact exist prior to English settlement. The Indigenous system of property is certainly as legitimate as the system of property that was derived from the English law, and was adapted to and developed in the conditions found in Australia. While recognising the delicate nature of balancing the two regimes, the future development of native title law as part of the Australian land law ought to recognise, to the greatest extent possible, the legitimacy of the pre-European Indigenous governance regime, and be modeled with this regime in mind.

At the time of English settlement, Australia appeared to have an abundance of land, although, not all of it would prove to be of productive value (largely due to the scarcity of water, which will be dealt with below). Thus, as we have already seen, the system of land tenure that developed to deal with what seemed to be an abundance of land, but in fact is considerably less when viewed from the perspective of agricultural use, has a long, complicated, and unique history. While the initial seed of the legal structure now recognised in Australia, planted in 1788, was the English common law,[102] the subsequent growth of the land law became uniquely Australian over time, as summarised by Fry: rights to land are ‘derived either directly or indirectly from the [Australian] Crown, or not at all.’[103] It was not possible to gain rights to land in any other way, for example, by ‘squatting’ on it[104] (the one subsequent exception, being, of course, native title rights). [105] Thus, as we have already seen, the Crown’s sovereignty, in the sense defined by Cohen, was settled rather early on in Australia – it was the power to control the exercises of rights granted pursuant to the system of land tenure that had developed over time from the initial settlement.

For the holder of property, or the private form of sovereignty identified by Cohen, the situation was somewhat more complicated. Rather than a small number of tenures – which one might have thought likely given the declining importance of tenure in England, the Australian state breathed new life into the doctrine in order to make it possible to allow private use of land while at the same time strictly controlling that use, whatever it might be. In other words, the Crown’s sovereignty has been exercised extensively, not only to create an array of tenures unknown to the English law, but also to control the exercise of the private form of sovereignty thus conferred on individuals under those tenures. The interplay of historical, social, and political factors thus produced a unique and complicated system of tenures in Australia.

This point is demonstrated in the fascinating history of the ‘squattocracy’. Early in Australia’s colonial history, it was thought desirable to implement a policy of concentration of settlement. This was achieved by the Crown’s refusal to alienate land outside of the 19 counties surrounding Sydney, or around similarly small areas surrounding Brisbane, Melbourne and Hobart.[106] The colonists rebelled against this policy. From 1835 to 1847, thousands of settlers migrated from the settled districts out into the lands beyond, the so-called Crown wastelands. The Crown refused to alienate these wastelands, but they had, since settlement, remained unoccupied (except by some Indigenous groups). These settlers took to ‘squatting’ on these lands despite not having any rights or title to them, and thus occupied them illegally.[107] As these squatters began to develop the lands on which they squatted with fields, farms, and homes, the tensions between the state – the holder of the public version of sovereignty in Cohen’s schema – and the squatters – with no formal sovereignty –began to grow.

The squatters were developing and improving these lands, and making their livings from them, but their position was tenuous. At any moment, the Crown could remove them from these lands, given that they held no formal right or colour of right to them. Yet the sheer number of squatters saved them, for it would have been difficult on a number of levels to simply remove them; moreover not only had they occupied the lands, but the squatters had also developed them. What was the Crown to do? The solution was not only ingenious, but also unknown in the history of English land law. In 1839 the New South Wales Parliament enacted the Squatting Act 1839 (NSW), creating a system of pastoral licences allowing the squatters, henceforth to be known as licencees, to occupy lands outside of the settled districts, provided they did so for pastoral purposes. In return, these squatters-turned-pastoralists were required to pay an annual fee to the Crown to hold their licence.[108] The Crown had not only exercised its sovereignty over these lands, but had also created in the squatters the private form of sovereignty over the land which they had previously been denied through lack of a formal right.

Yet, this licensing system, innovative though it was, failed to appease the squatters. By 1847, an Order in Council provided for these ‘pastoralists’ to hold the land on 8 or 14-year leases for an annual rent. In exchange, the Crown continued to hold a right of resumption, whereas, if the Crown had granted fee simple title to the land, no such right would have remained in the Crown save that of escheat, or its modern successors based on the principle of bona vacantia. And thus, a new form of Australian tenure had been created – the pastoral lease – one which had not existed in England, and was the creature of the 1847 Order in Council rather than the common law.[109]

This innovation in new forms of tenure continued apace in the colonies. In 1868, a new form of statutory tenure, Selection tenure, was created in New South Wales. This new form of agricultural tenure was designed to allow a small-scale farmer to obtain the freehold to land occupied through a system of installment payments and the satisfaction of various conditions. Generally, the conditions imposed were that the farmer establish a personal residence on the Selection for a specified period, and that they make permanent improvements to the Selection to the value of a specified sum. Fry wrote that one of the essential features of Selection tenure is that

after a ... period of years, it changes its nature, as in a kaleidoscope, from a Crown leasehold tenure to a freehold tenure; and may therefore be said to be a ‘convertible’ tenure.[110]

He observed that prior to this ‘conversion’ to freehold tenure, it is very similar to the Crown leasehold tenancy.

These two early forms of tenure showcased the two characteristics that permeated the proliferation of statutory tenures that ensued; what Millard called ‘a bewildering multiplicity of tenures’.[111] The first such condition was the payment of an annual rent. The second was the imposition of occupation or development conditions, which sought to ensure that tenants were to fully utilise and develop the lands granted to them.[112] And, as we have seen, this serves as an example of the exercise of state sovereignty so as to control the exercise of the individual’s sovereignty held under one of the forms of tenure created by the state, and so protect the common good.

It was not until the turn of the 19th century, though, that the great innovation of Australian real property law was developed, what Fry called ‘the zenith of the Australian system of Crown leasehold tenures’.[113] This was the introduction of the Crown perpetual leasehold tenure. Historically, the largest estate known to the common law was that of the fee simple, which conferred perpetual title to land. As Fry wrote:

[i]t is a rule of the Common Law which cannot be disproved by any mathematical or other arguments, that a fee simple is a ‘larger’ estate than any leasehold estate, however long the term of years conferred by the latter, even if it be 10 000 or 100 000 years.[114]

There was no other form of perpetual title to land recognised by the common law, nor had English law ever countenanced any form of perpetual leasehold. A lease could be granted for an indefinitely long term of years, or a lease could be granted with an option to renew indefinitely, but it could not of itself and by its nature be perpetual. The unique Crown perpetual leasehold was thus entirely the creature of statute, and distinct from freehold tenure.

The policy behind the creation of the perpetual leasehold was simple: the Crown wanted to retain control of the land, and to limit the choices that individuals had regarding the way in which they used their land. Unlike a freehold grant, which generally conveys the land without any future obligations, the leasehold tenure is almost always conveyed with ongoing obligations – incidents of tenure. The incidents imposed upon Crown lessees varied by the form of tenure, but were categorised by Fry as incidents involving:

(i) monetary exactions in the form of land taxation and Crown land rentals; (ii) developmental conditions (such as the erection and maintenance of fences or other ‘improvements’, or the eradication of noxious plants) necessitating the expenditure of money, or its equivalent in labour and materials; (iii) certain non-mining conditions, such as the condition of ‘personal residence’ and the less exacting condition of ‘occupation’; and (iv) mining conditions, such as the condition of labour-employment and that of continuous utilization; ... (v) various rules as to the maximum areas which any one person can hold on each particular kind of Crown leasehold tenure; and (vi) restrictions placed upon the Crown tenants’ rights of alienating or encumbrancing their respective holdings.[115]

Fry explained that these tenurial incidents were designed and imposed in order to:

(a) provide revenue for use by ... Governments and the Local Authorities, (b) develop the productive capacity and economic value, and the civilized amenities, of lands ... and (c) prevent the rise of a class of absentee owners possessing undeveloped lands, which would hinder the policy of populating the country districts.[116]

The multiplicity of uniquely Australian tenures, developed by statute, was thus ‘evidence of a cogent and administratively enforced policy of making land serve as an instrument of national and social purposes.’[117] This social engineering was greatly advanced by the corresponding policies of Australian governments to grant leasehold tenures in preference to freehold tenures in many areas – thus ensuring that they could enforce their development policies through tenurial incidents that would be otherwise unavailable with a freehold grant. In short, what Fry is recounting, and summarising, is the history of the Australian Crown’s exercise of that form of sovereignty identified by Cohen that the state enjoys and may exercise in order both to allow the individual to hold power to make use of goods and resources, in this case land, while at the same time controlling that use so as to protect the common good. As Fry sagely observed:

In the feudal era in England, as also in Australia to-day, Parliament and the Crown (as advised by the magnates of the realm in past times and by Cabinet Ministers in modern times) imposed upon Crown tenants such tenurial incidents as were best calculated to advance the policies thought at any particular time to be appropriate for the purpose of ensuring the safety and prosperity of the realm.[118]

Times change; policies change; but the way in which land is used as a means of control remains. The concern, from medieval to modern times, about the conditions upon which we choose to alienate land (the type of tenure) is perhaps the best evidence available that to grant land is both an exercise and a grant of sovereignty. And this, in turn, may provide lessons for the exercise of such sovereignty in the future.[119]

Historically, ownership of land entailed ownership of all that lay beneath the soil. This was reflected in the Latin brocard, attributed to the 13th century glossator Accursius, cujus est solum ejus est usque ad coelum et ad inferos (whoever owns the soil owns it all the way up to the Heavens and down to Hell).[121] This principle was recognised in the common law of England as early as 1586 in the case of Bury v Pope,[122] and the doctrine was inherited in the common law of Australia upon settlement.

Subject to two important exceptions, this meant that pursuant to the cujus est solum doctrine, a landowner owned the minerals lying beneath the surface of that land.[123] The first was the case of the royal metals, gold and silver, which as early as 1568 had been held to be the property of the Crown in the famous Case of Mines.[124] The second was that the ownership of minerals in land was subject to any express reservation contained in the Crown grant concerning minerals.[125]

In the early days of Australia’s settlement, minerals were not often reserved in Crown grants.[126] This meant that from 1788 until the mid-to-late 19th century, minerals (other than the royal metals) were largely privately owned in Australia. With ownership of the land came the ownership and control of its mineral wealth.

But towards the end of the 19th century, there was a rejection of private ownership of Australia’s mineral wealth. Beginning with New South Wales, all states and territories passed legislation which reserved all minerals in land for future Crown grants.[127] The legislation operated only prospectively, and represented a progressive policy to vest all ownership in minerals in the Crown. Bradbrook describes this process as ‘a complete rejection of the operation of the cujus est solum doctrine’ in respect of minerals.[128]

As time went on, the desire that all of Australia’s mineral wealth should be shared by the community at large has led some jurisdictions to retrospectively vest ownership of minerals in the Crown. South Australia, Victoria, and the Northern Territory, have all passed legislation to this effect.[129] In the other Australian jurisdictions, some minerals are still privately owned arising from 19th century grants,[130] but there is no future capacity to extend private ownership of minerals.[131] Cox described the rationale behind the public ownership of minerals as reflecting a belief that mineral deposits are a fortuitous gift of nature and that any net benefits flowing from their exploitation should accrue to the community as a whole, rather than to whoever happens to own the surface rights.[132]

The idea that minerals are indeed a ‘fortuitous gift of nature’ that should ‘accrue to the community as a whole’ completes a wholesale shift in the ownership of minerals in Australia over time. And, we see in this shift the exercise of the state’s sovereignty restricting exercises of an individual’s power over land, thus protecting the interests of the community – the common good. While early in Australia’s history, individuals, fortuitous landholders, enjoyed the benefit of minerals lying below the surface, thus giving full scope to that form of individual sovereignty identified by Cohen, the state chipped away at the full panoply of such power over time.

With the demise of the cujus est solum doctrine, then, we have seen the birth of a regalian system of mineral development in Australia. The state progressively took over the development of mineral resources in Australia by taking ownership of them, and by leasing rights to explore and extract mineral resources to private companies and individuals in exchange for royalties, resource rent taxes, and other payments. In each case, proffering evidence of a truly Australian approach not only to the creation of such tenures as would allow the use of these resources, but on terms that ensured the benefit of the common good. To ensure that minerals are exploited in an efficient way, Australian governments also frequently impose specific conditions on licensees regarding the development and working of the tenements that they hold.[133] In so doing, the various state and territory governments seek to exploit Australia’s mineral wealth for the benefit of the public at large. This is a dramatic shift from the early colonial days, where private individuals exploited the privately owned minerals on their land for their own benefit, and Cohen’s individual sovereignty reigned supreme.

Australia’s European settlers early recognised that water was in very short supply (the realisation, which, as we have seen, meant that what might have seemed an abundance of land, was not). The unique development of water law in Australia, then, provides a poignant example of the way in which property confers sovereignty as concerns a scarce resource, straddling the divide between both a public right and a private right.

On settlement, Australia inherited the ancient common law from England which governed the access to and use of water.[134] This was the common law of surface ownership and riparian rights, which coupled real property with water resources, and made access to water an incident of the ownership or occupation of the land on which the water was located, or of land adjacent to which a watercourse flowed.[135] Historically, there was no ‘property’ in flowing water – the water was owned by the public at large[136] – and any rights to water were incidental rights of access, which people gained by owning or occupying the land next to a watercourse. In this way, ‘rights of access to water were separate from rights in relation to land but nevertheless conditional upon or incidental to rights in relation to land’.[137] This, in effect, placed the control of all water resources in the hands of private landholders, who exercised their rights of access privately and for their own benefit (much as was the case with minerals). Individual sovereignty appeared therefore to operate without restraint.

True, this form of private regulation of water resources served well the water-rich, luscious green pastures of England for hundreds of years. But Australia, the driest continent on Earth, with its semi-arid climate coupled with its great rainfall variability, rendered the English system totally unworkable.[138]

A range of issues including the desire to promote irrigation, the need to meet the water demand for mining, and the need to supply water to the growing urban population – in other words, clear considerations that affected the common good – prompted legislative change in the late 19th century across Australia.[139] Victoria took the lead, establishing a Royal Commission on Water Supply in 1884, led by Alfred Deakin. The result of the Commission, which was greatly influenced by the regulatory system devised for irrigation in the western United States,[140] was The Irrigation Act 1886 (Vic). This landmark Act vested the right to the use, flow and control of water in the Crown, and prevented the further establishment of riparian rights.[141] Similar Acts were passed in the other states and territories,[142] which made all existing riparian rights (that is, private rights) subordinate to the rights of the Crown to access and use water (that is, public rights). Thus began a system of public management of Australia’s limited water resources. The state’s sovereignty to protect the general welfare prevailed over the common law’s prioritising of the individual.

The Crown managed water by licensing its extraction by users (that is, granting usufructuary rights), and by the ‘construction of dams and reservoirs, the provision of infrastructure, the treatment of water, and the distribution and reticulation of water’, which were all public functions.[143] This system of public management of water remained largely intact for the next 100 years.[144] An important feature of this system was that grants or allocations of water were still tied to land titles.[145]

The 1980s saw considerable efforts to reform water management in Australia owing to environmental and ecological concerns about the degradation of water sources across the country, coupled with issues relating to water security and water quality.[146] The 1990s saw continued agitation for a change in water policy, and a desire to increase water allocation efficiency alongside other competition reforms.[147] The Council of Australian Governments (‘COAG’) developed the Water Resource Strategy in an attempt to both harmonise and reform water policy developments across Australia. This was followed by the National Water Initiative in the mid-2000s, which provided a programme of implementation for water law reform across Australia.[148] Alongside crucial environmental reforms, perhaps the most controversial of the suggested reforms was the decoupling of land ownership or occupation from water entitlements.[149] Clause 4(a) of the Water Resources Policy required all governments to

implement comprehensive systems of water allocations or entitlements backed by separation of water property rights from land title and clear specification of entitlements in terms of ownership, volume, reliability, transferability and, if appropriate, quality.[150]

The establishment of private property rights in water was ‘considered a necessary precondition to water trading’ and a water market, which COAG envisioned would improve sustainability and efficiency for water resources.[151]

The implementation of this particular aspect of the reforms has varied among the jurisdictions. New South Wales, for example, has not gone so far as to declare a water licence to be personal property under its Water Management Act 2007 (NSW).[152] Meanwhile, South Australia expressly declared that a water licence is a form of personal property.[153] Of course, the recent High Court decision in ICM Agriculture Pty Ltd v Commonwealth[154] suggests that the character of these statutory rights to access water is a matter of construction, and that the right must have the relevant indicia of a property right before it will be considered one.[155] Nevertheless, what we find in these recent developments is that the notion of private property in water is a legal concept that is beginning to emerge, and that will develop over time.

Thus, we see that the nature of property in water is beginning to come full circle. We begin with water being owned by the public at large, but being accessed and used through a series of private rights connected with the ownership of land. The harsh Australian climate conditions, and the desire to promote development in the fledgling colonies, stimulates a series of reforms that claim public control over water resources, and private rights are subordinated to a governmental system of water allocations or licences. We are now in the middle of a process which has seen a return to private rights in water. Whilst there is still active debate about the true nature of the new series of statutory rights being created, they have many of the hallmarks of private property – some are even declared to be so. But these new rights to access water, or these new forms of personal property, are very different from colonial days. No longer is access to water tied to land; nor do owners of land necessarily have rights to access the water on their land. The government is creating a new form of property in water. As one of the scarcest resources in this driest continent on Earth, it must be recognised that this represents a new means of that state’s exercise of sovereignty as concerns property, at once conferring sovereignty on the individual and limiting the power so conferred so as to protect the common good.