University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

CITATION PRACTICES OF THE AUSTRALIAN LAW REFORM COMMISSION IN FINAL REPORTS 1992–2012

KIERAN TRANTER[*]

For 40 years, the Australian Law Reform Commission (‘ALRC’) has been a highly visible feature of the Australian legal landscape. It has endured through changing governments, and changing social and political contexts, and has forged a national and international reputation as a leading institutional law reform agency.[1] While the ALRC and other institutional law reform agencies do many things, their primary activity, and the one that they are most judged on, are their reports, particularly final reports.[2]

This article sets out a study into the citation practices within ALRC final reports from 1992 to 2012. The study found that submissions were the most frequently cited source. This finding supports an argument that the ALRC has believed the best way to influence the executive is to locate recommendations within what can loosely be called the ‘community’. Another finding was that the ALRC did not extensively reference academic sources. Within the literature on institutional law reform there has been suggested two different approaches for how law reform commissions should operate. One has been the ‘research institute’ approach where recommendations are generated by experts analysing relevant data and academic literature. The other has been the ‘community engagement’ approach where recommendations are located as having emerged from a process of community consultation. These are not either-or alternatives; rather they are poles of a continuum with agencies adopting a blend of both approaches. In finding that submissions were the most frequent cited source and academic research the least frequent, it can be argued that the ALRC has been committed more towards a community engagement rather than a research institute approach. Having found this, a question can be raised as to how this approach meets current expectations for ‘evidence-based’ reform. It is argued that the ‘success’ of a more research institute approach by the Productivity Commission indicates that the ALRC might adopt more of this approach in the future.

This article is in four Parts. Part II locates this study within two literatures: literature on institutional law reform and literature on citation patterns. By providing an empirical insight into the working of a specific law reform commission, it extends the literature on institutional law reform. It also extends the scope of citation analysis from the judiciary and academia to another significant legal institution. Part III introduces the ALRC and particularly the 21 years between 1992 and 2012 that is the focus of this study. Part IV details the key findings. Part V discusses these findings in the context of literature on institutional law reform. It is suggested that the findings reveal that the ALRC has had a strong commitment to the community engagement model. This exposes the ALRC to criticisms of the community engagement approach. This Part concludes with a comparison with the Productivity Commission to suggest that current expectations of law reform might involve a greater emphasis on the research institute approach.

This Part locates this study within two distinct literatures. The first is the literature on institutional law reform. The second is the much more substantial literature on citation analysis of legal texts. Concerning the first literature it is argued that much of the writing about law reform commissions has been either advocacy – that is advocating for institutional law reform – or technical, explaining how specific institutional law reform activities should take place. There has been only a limited critical discourse that has questioned institutional law reform. This study contributes to a more critical discourse concerning institutional law reform through a detailed examination of what a law reform commission has actually done, namely produced final reports recommending to the executive that laws should be changed. Concerning the second it is argued that the extensive literature that has analysed the citation practices within law reports and law journals provides the template and tools for similar analysis of other legal texts. This study does just this, taking up the concepts and methods developed in citation analysis and applying them to a sample of ALRC final reports.

Over the past 50 years there has emerged in British Commonwealth jurisdictions a dedicated literature concerned with institutional law reform. By institutional law reform what is meant is the locating of law reform activity within an identifiable entity that is neither the courts nor the formal element of the executive responsible for law and courts (for example, the Attorney-General’s Department or Department of Justice).[3] The paradigm examples of institutional law reform are law reform commissions. Three strands can be identified within this literature.

The first strand can be seen as the literature that advocates for institutional law reforms. This ‘advocacy’ literature encompasses several dimensions. The first are the articles that argue for the establishment (or re-establishment) of institutional law reform agencies within specific jurisdictions.[4] The second are reviews documenting the histories and successes of law reform commissions.[5] The third are accounts of specific inquiries and reports by a law reform commission.[6] There are two features that tie the advocacy literature together. The first is that they are often authored by persons connected to law reform commissions, particularly Commissioners or employed commission staff. The second is that they are generally positive about institutional law reform.

The second strand focuses on the technical aspects of managing commissions and conducting inquiries.[7] Again the authors of this literature tend to be internal to law reform commissions, and criticism, where present, is directed outwards, towards a wider context which is regarded as making it more difficult for commissions to do their job.

The third strand comprises the limited literature that is critical towards law reform commissions by expressing doubts and anxieties about institutional law reform. The doubts relate to concerns about what is meant by ‘law’ and ‘reform’ and how a lack of precision in defining these terms affects the approaches used by institutional law reform. Geoffrey Sawer’s writing in the 1970s identified that legal practice and established jurisprudence do not provide a theory of law reform. As such he suggested that law reform commissions did not have a robust set of values to guide the reform process. He determined that the guiding values were the strongest concerning procedure but on substance tended to be ‘subjective intuitions and hunches’ about what is fair or economical.[8] Sawer identified an essential pragmatism about law reform that has continued to bedevil thinking about institutional law reform. For some writers such as Patricia Hughes, this pragmatic core represents an opportunity for clearer articulation. For her, the activities of institutional law reform commissions can be both better explained and be placed on a more substantive footing if commissions adopt as their lodestar ‘access to justice’.[9]

For Roderick MacDonald, President of the Law Commission of Canada (‘LCC’) in 1997–2000, the changing fortunes of institutional law reform in Canada[10] should give pause to thinking about the methods and appropriateness of institutional law reform. Specifically, MacDonald locates institutional law reform within changing historical contexts. He makes a distinction between the research institute approach and the community engagement approach. The research institute approach regards law reform as an elite activity conducted by experts.[11] Evidence of a research institute approach would be the writing of detailed, technical final reports that make findings based on independent research and recourse to secondary academic literature. The community engagement approach regards law reform as a process that needs to engage with the public. Evidence of a community engagement approach would be the writing of less-technical, more broadly accessible final reports that locate and justify findings in terms of values and ideas derived from a process of consultation.[12] MacDonald regards the two approaches as historically connected. He argues that the community consultation approach grew out of criticisms of the research institute approach during the 1970s.[13] Having historicised each approach, he questions their contemporary appropriateness, warning that institutional law reform should not to be too concerned with the continuity of specific institutional forms; and that by becoming institutionalised, what he regards as an essential ‘creativity’ might become stifled.[14]

A more pointed criticism of law reform commissions has been articulated by Reg Graycar and Jenny Morgan, both of whom have been Commissioners of the ALRC. Echoing some of the criticisms of MacDonald, they suggest that institutionalisation has not inherently been a victory for women.[15] They identified a range of structural problems with law reform commissions that reduce their responsiveness to women, ranging from a tendency to operate within traditional doctrinal divisions of law, to the prioritising of legislative change as the only panacea to social problems.[16] In particular, they focused on the sources of data used by law reform commissions, and raised concerns with the process of consultation adopted by commissions under the community engagement model. They identified that consultation with ‘stakeholders’ tended to produce standard responses from vested, usually male-dominated interests.[17] Further, the time and resources that a participant needs to devote to a public submission would often exclude women.[18] This exposes law reform commission to the phenomenon that Reg Graycar has repeatedly identified as ‘law reform by frozen chook’.[19] She has written of situations in family law reform where vocal and media-savvy minorities have been able to influence the legislative process resulting in legal change.[20] The successful strategy has been to support claims for reform with anecdotal stories. For example, the claim that men suffer domestic violence from women was buttressed in the media by a statement that an ex-partner ‘once chucked a frozen chook at me’.[21] Graycar argues that law reform in this context was influenced by these anecdotal stories rather than by contemporary comprehensive reliable data concerning domestic violence patterns, child and women poverty, and the actual share of childcare within relationships gathered by researchers.[22] It is this generation and use of empirical data that Graycar and Morgan find mostly absent within institutional law reform; and when it is used by law reform commissions, they suggest it has been used inappropriately.[23]

Graycar and Morgan reveal an obvious gap in the literature on institutional law reform: that there has been little external research that looks at what law reform commissions actually do. Their article, although advocating for more empirically driven law reform, is ironically based on general structural criticisms, data drawn from experiences and specific examples – the sort of analogical approach that is susceptible to the anecdotal stories that they criticise law reform commissions are using. Nevertheless, they do establish a research agenda. First, their article poses the question as to how law reform commissions present the authority of their recommendations (based on ‘research’ or ‘community’); and second, their article suggests that investigation of how commissions present authority should be based on empirical examination of law reform commission activity. It is this agenda that frames this study.

The only study that has come close to this study was a comparison by Angela Melville of the contrasting approaches to law reform evident from reports by the New Zealand Law Commission (‘NZLC’) and the LCC.[24] In examining the reports she found significant differences between the NZLC’s narrow approach with ‘top down consultation’ and little transparency as to its methods compared to the LCC’s more socially inclusive approach and provision of methodological detail.[25] Melville’s study is significant in that she examined the two reports to determine how each commission actually did the processes of law reform. This study extends in a more structured manner Melville’s reconstruction approach to law reform from the text of the reports. A criticism of Melville could be that her own process of reading, extraction and analysis from the reports is not disclosed. Like Graycar and Morgan, Melville’s affirmation for transparent empirically based law reform is not grounded in a transparent empirically based analysis of law reform commission activity. It is the lacuna that this study fills through application of citation analysis to a sample of ALRC reports.

In North America there has developed a sizable body of literature devoted to recording and analysing citation practices in law. The primary focus has been the examination of the citation practices of the judiciary through surveying the citations in law reports.[26] Within this, a strongly explored question has been: which law reviews and academics have been cited by the judiciary?[27] A parallel field has been the focus on law reviews to determine the most cited author, article and journal.[28] In Australia, the citation practices of the judiciary has been comprehensively explored by Russell Smyth who has examined the citation practices of the Federal[29] and the state Supreme Courts[30] and particularly the Australian judiciary’s recourse to secondary literature.[31] Also there has been a series of studies focusing on the citations and authors within Australian law reviews.[32]

This research tends to produce ranking tables with lists of most frequently cited judges, courts, decisions, academics or journals from the examined sample. However, in themselves rankings say very little. Citation analysis literature takes on wider meaning through two assumptions about citation patterns. The first is that when an author, judge or academic cites, it is a public declaration that the author has read and been influenced by the cited text.[33] The second is that citing is a strategy of communicating authority. The author uses citations to locate their text within a web of other texts making their writing more persuasive because of its cited connections and specifically through the citing of ‘prestigious’ authors or texts.[34] To cite tells a reader that the proposition that is accompanied by a citation has authority, not just because the author is saying it, but that others have said it.[35] There is a danger of misinterpretation when considering the results of a citation analysis. It provides metrics of citation rates. It does not necessarily provide any qualitative detail about how the author used any specific citation or category of citations. Material in citations can be referenced as authority for a point made in the text, or disagreed with by the text, or referenced as an aside to the text. Just because an author cites repeatedly from a source, it does not mean the author approves of the source. However, this does not restrict interpretation of citation analysis data. The fact that an author has felt compelled to reference a text – irrespective whether it is in the positive, negative or as an aside – is a claim by the author that the material in the citation is important. It is a representation by the author to the reader that the cited material is relevant and enriches what the author is trying to say. Furthermore, it can be suggested that citation analysis can be a form of archaeology whereby the processes of shaping a given text can be uncovered through examining the citations. What is cited and what is not cited gives an insight into the text’s formation. This is what Melville did with the NZLC and LCC reports. She identified that in its report the LCC directly cited submissions it had received and also referenced empirical research while the NZLC did not.[36] From this evidence she made conclusions about each commission’s different approach to law reform.[37]

This study extends Melville’s approach by drawing upon the tools developed by citation analysis to rigorously determine and record the sources cited by the ALRC within a sample of final reports. In doing this, it also extends the citation analysis literature by applying it to a new set of texts. As this is the first study to apply citation analysis to law reform commission reports, it adopts the methods used by the survey studies that examined the citation practices of the judiciary.[38] The precise methods used to code the sample are explained in Part IV below. However, before the details of the analysis and findings can be discussed, the sample of the study, the final reports by the ALRC from 1992 to 2012, requires introduction.

This Part introduces the sample of the study: the 42 final reports completed by the ALRC between 1992 and 2012. In doing so the wider context of the ALRC over this period requires discussion. It will be seen that over the 21 years, the ALRC has been consistently producing final reports based on references from the Attorney-General. It will also been seen that the ALRC has maintained its outputs in a context of decreasing budgets and staffing size.

The ALRC was established in 1975 as one of the last reforms introduced by the Whitlam Labor Government.[39] The model for the ALRC was the Law Commission of England and Wales established in 1965.[40] The ALRC was not the first law reform commission in Australia. New South Wales established a law reform commission along the English model in 1966.[41] The ALRC was established with a mandate to provide the Attorney-General with reports on law reform.[42] Unlike the NZLC or the Law Commission of England and Wales, the ALRC cannot self-initiate an inquiry.[43] It has been and remains dependent on references from the Attorney-General.[44]

The 1970s and early 1980s have been identified as the ‘golden age’ of law reform commissions and of the ALRC in particular.[45] Under the leadership of Michael Kirby it was an era of increasing budgets, cross-party support and successful implementation of recommendations.[46] However, notwithstanding confident statements in 1983 that institutional law reform was ‘in full flower’,[47] the blooms did not last. In Australia, law reform commissions in South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria were abolished during the late 1980s and early 1990s.[48] It is precisely this troubling time – the silver, or possibly bronze age of law reform – that is the period for this study.

The period 1992–2012 is more than half of the ALRC’s duration. Over this time the ALRC has undergone many changes. It experienced a name change in 1996, changing from the Law Reform Commission to the current title of the Australian Law Reform Commission.[49] It has endured through two changes of government, four prime ministers, six attorney-generals and been headed by five presidents.

Table 1: Presidents of the ALRC[50]

|

President

|

Tenure

|

|

Professor Rosalind Croucher

|

December 2009 – Present

|

|

Emeritus Professor David Weisbrot

|

June 1999 – November 2009

|

|

Alan Rose AO

|

May 1994 – May 1999

|

|

Sue Tongue (acting)

|

November 1993 – May 1994

|

|

Hon Elizabeth Evatt AO

|

January 1988 – November 1993

|

|

Justice Xavier Connor AO

|

May 1985 – December 1987

|

|

Hon Justice Murray Wilcox

|

September 1984 – April 1985

|

|

Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG

|

February 1975 – August 1984

|

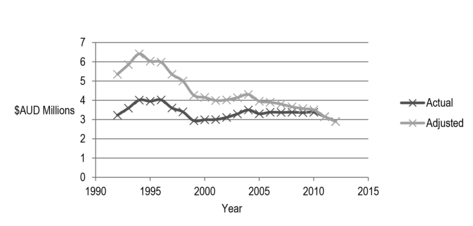

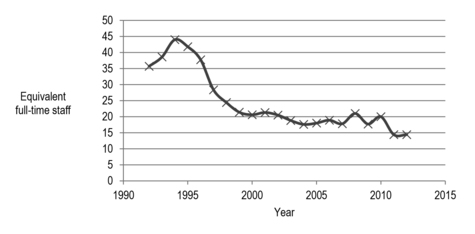

The budget and staffing profile of the ALRC has changed considerably between 1992 and 2012. Figure 1 provides the budget of the ALRC over the past 21 years in nominal amounts and amounts adjusted for inflation.[51] The nominal amount of the appropriation has remained consistent at around $3 million a year. However, when adjusted for inflation, the budget in real terms has shrunk from $5.35 million in 1992 to $2.9 million in 2012. The staffing profile of the ALRC has similarly diminished. Figure 2 provides the staffing of the ALRC from 1992 to 2012. In 1992, the ALRC had an equivalent full-time staff profile of 35.7. In 2012, this had fallen to 14.4. The decreases in budget and staffing show that the ALRC in 2012 was a considerably smaller organisation than it was in 1992.

Figure 1: ALRC Budget by Year

Figure 2: ALRC Staffing by Year

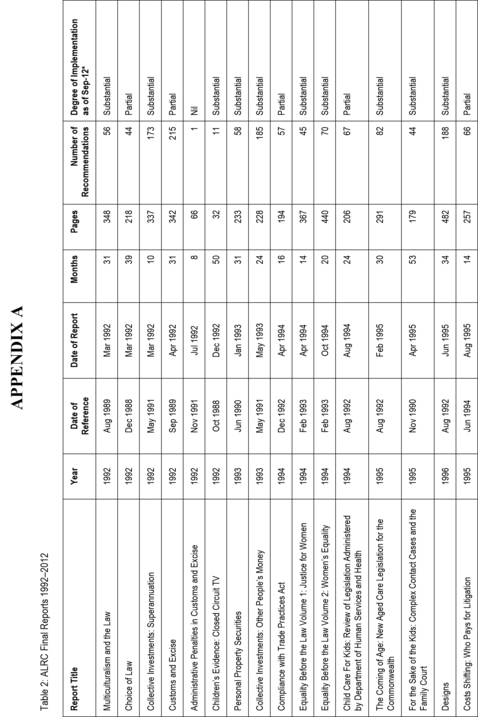

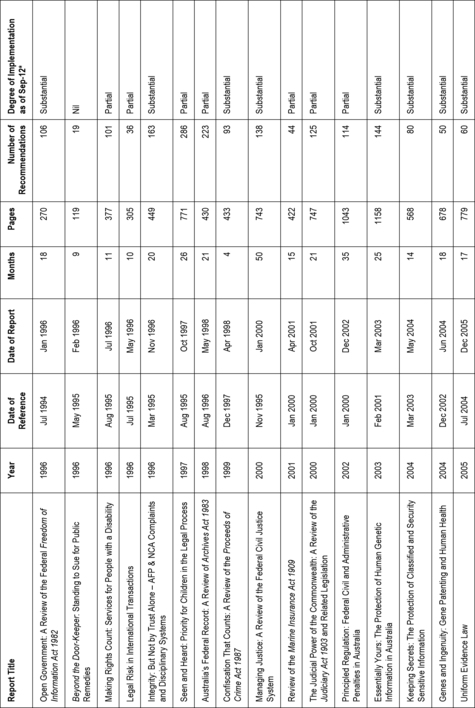

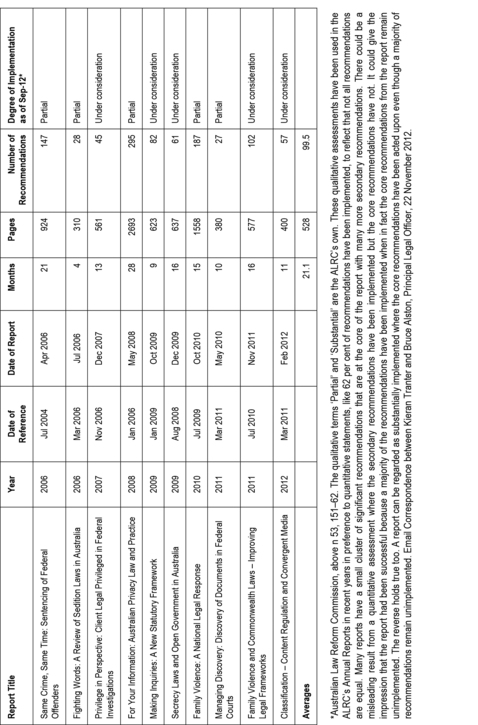

Throughout this institutional change the productive work of the ALRC has remained consistent. In response to references it has undertaken research, conducted consultations, released issues and discussion papers, received submissions and completed the process by providing the Attorney-General with final reports containing recommendations. Between 1992 and 2012 the ALRC produced 42 final reports.[52] The detail of each of these reports is in Table 2 in the Appendix.

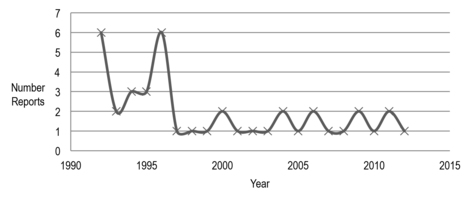

Between 1992 and 2012 the ALRC finalised on average two reports per year. This figure is distorted by outrider completion rates in 1992 and 1996 of six reports in those years. For the period 1997–2012, 21 reports were completed, representing an average of 1.31 reports a year. This is consistent with the first 10 years of the ALRC (1975–85) where there was an average of 1.5 reports per annum.[53] Report completion by year is provided in Figure 3. A feature of Figure 3 is that since 2003 the ALRC has settled into a pattern of alternating one report a year and then two reports the following year.

Figure 3: Reports by Year

Another measure is the timeliness of the ALRC in producing final reports. A criticism of law reform commissions has been that they can take too long to produce a final report, by which time the political will for reform has dissipated.[54] Between 1992 and 2012, the ALRC took on average 21.1 months to complete a reference.[55] The longest was For the Sake of the Kids: Complex Contact Cases and the Family Court (1995) which took 53 months from reference to report.[56] The shortest were Confiscation That Counts: A Review of the Proceeds of Crime Act 1987 (1999)[57] and Fighting Words: A Review of Sedition Laws in Australia (2006)[58] that both took four months. As a general pattern the ALRC is getting quicker at completing inquiries with average time decreasing from 24.8 months in 1992–95 to 12.8 months in 2009–12.[59]

However, not all reports are equal in length. While the average length of a report was 528 pages, there was a range from 32 pages for Children’s Evidence: Closed Circuit TV (1992)[60] to the 2693-page three-volume behemoth, For Your Information: Australian Privacy Law and Practice (2008).[61] In the literature on institutional law reform, a distinction has been made between ‘lawyers’’ or ‘technical’ law reform and ‘social’ or ‘significant’ law reform.[62] The first relates to technical reforms to the mechanics of law. These are reforms that are of interest to legal practitioners in specific fields but might not excite the wider community. Between 1992 and 2012, the ALRC had few references that could be characterised as ‘technical law reform’.[63] An explanation for this can be seen in the federal jurisdiction of the ALRC.[64] In Australia, technical law reform tends to be a state responsibility and the state law reform commissions often produce short reports on narrow topics such as vicarious liability[65] or time limits on loans payable on demand.[66] As such, most of the references to the ALRC involve broader social, political and economic considerations.[67]

Indeed, between 1992 and 2012, the ALRC has been asked to grapple with complex law reform, including wholesale reviews of the federal courts,[68] rights-driven law reform for women,[69] children[70] and the disabled,[71] private international law,[72] law reform in response to technological-driven change,[73] and legal responses to family violence.[74] Common to all these references was a requirement that the ALRC understand law and the process of law reform ‘in context’, explaining, at one level, why the average report length is 528 pages. Another indication of the complexity of the references that the ALRC has reported on is the average number of recommendations, which is 99.5 recommendations per report.[75]

What preliminary stories emerge from this overview of the ALRC and the sample? The first is that it seems that the ALRC underwent a significant change in fortune with the election of the Howard Coalition government in 1996. Between 1994 and 1999 the ALRC’s budget fell by $2.15 million adjusted and staffing declined by 22.6 equivalent full-time positions.[76] This decline can also be seen in the number of reports the ALRC completed each year. After 1997, the ALRC’s workload changed from an average of four reports per year for 1992–96 to 1.3 reports per year for 1997–2012.[77] From this it can be seen that the ALRC was given less budget and fewer references by the Howard Coalition Government than by the previous Keating Labor Government. The second is that the election of the Rudd/Gillard Labor government in 2007 had no noticeable change to the general declining pattern to the ALRC’s budget and staffing. Since 2008, the budget has declined $0.66 million adjusted and 6.6 equivalent full-time positions have been lost.[78] In response to this continual decline, the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee conducted an inquiry which reported in April 2011. While the Committee recommended an immediate reversal of the ALRC budget decline,[79] the government senators in a dissenting report[80] and the government in response argued that in an environment of fiscal constraint the ALRC’s budget was adequate.[81] Notwithstanding these declines in resources, the ALRC has continued to receive and report on 1.4 references year since 2008.

What is shown is that the ALRC has become a much more productive organisation able to maintain outcomes with declining resources. For the years 1997 and 1998, the ALRC produced two reports of a combined size of 1201 pages[82] with an adjusted average budget of $5.17 million and an average 26.4 equivalent full-time staff. For the years 2011 and 2012, the ALRC produced three reports of a combined size of 1357 pages[83] with an adjusted average budget of $3.25 million and an average of 18.9 equivalent full-time staff. An indication of the productivity increase can be seen in the changes in the cost per page and staffing per page ratios between these two periods. In 1997–98, a page cost $4304 and involved 0.029 equivalent full-time staff. In 2011–12, a page in the report cost $2395 and involved 0.0139 equivalent full-time staff. This reveals a productivity increase of 55.6 per cent for cost per page and 63.4 per cent for staffing per page. These are highly artificial measures which fail to consider the specific workload demands of certain references[84] and also suggest that the sole and only proper use of the ALRC budget and staff time is the production of final reports.[85] Nevertheless, as broad longitudinal measures, these figures suggest that the ALRC over the period of the sample has been doing more with less.

It can also be seen that, for the period 1992–2012, the ALRC has settled into a pattern of 1.5 final reports per year. This suggests continuity and stability. The final reports from this period, although diverse in terms of subject matter, generally fell within the category of social law reform and were weighty documents running to hundreds of pages making on average about 100 recommendations. However, the period discloses significant change for the ALRC with a steady decline in budgets and staffing. However, this decline does not appear evident on the face of the reports. Although formatting and referencing guides used by the ALRC changed during the sample, a report like Designs in 1996 in its overall structure, chapter layout and page setting out is similar to recent reports such as Managing Discovery: Discovery of Documents in Federal Courts in 2011.[86] It is what is on each page that is most similar. The writing style conforms to the standards of academic writing; technical terms are explained and used, but the overall expected level of readership competency is high.[87] Sentences can run across multiple lines, large paragraphs take up much of each page; there are headings, along with introductory, summary and linking sentences and paragraphs.

An obvious feature reinforcing this assessment of the style of writing used by the ALRC is the significant numbers of citations. Indeed, a very clear feature of the reports in the sample is that there is rarely a page that does not have citations. While the formatting of citations used by the ALRC changed from footnotes to endnotes and then back to footnotes over the years, the practice of presenting reports with many superscript numerals on each page was a strong consistent. A further feature was that within those citations there were multiple references to different texts. In writing its reports this way, the ALRC can be seen presenting a theory of law reform that involves connecting, supporting and locating what the ALRC is saying with other texts. The next question is: what texts did the ALRC cite?

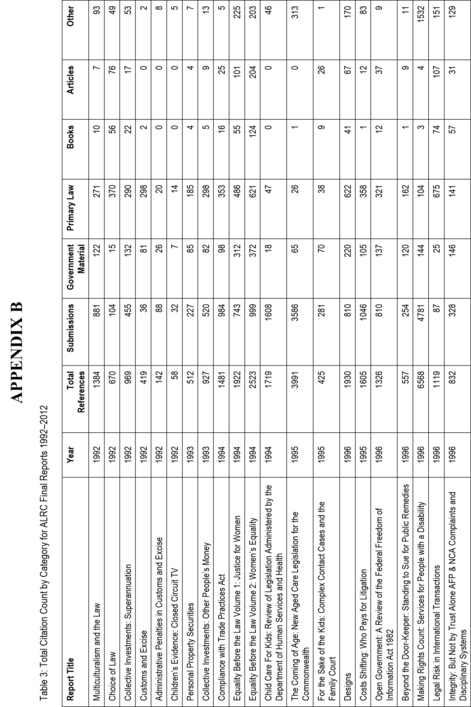

This Part sets out the findings of a citation analysis of the 42 final reports completed by the ALRC from 1992 to 2012. Following the methods used in the citation analysis of judicial decisions, a series of broad categories were identified; and within each category, more specific detail about an individual citation was recorded. Also following the practice within the citation analysis literature, every reference was recorded.[88] If a citation had multiple references, each was recorded individually. A note with three citations – to a case, a submission and a journal article – provided three counts.

The analysis adopted six general categories into which the citations were organised: ‘Submissions’, ‘Government Material’, ‘Primary Law’, ‘Books’, ‘Journals’ and ‘Other’. These categories differ from the general categories of case law or other distinction used in the citation analysis of judicial decisions. These categories were developed based on two considerations. First, a cursory glance at the ALRC final reports in the sample reveals that the ALRC cites a more diverse set of texts than the superior court judges that the usual citation analysis examines. Case law is nowhere near as prominent yet submissions and material authored by governments are much more evident. Second, in operationalising the identified distinction between ‘community’ and ‘research’ based law reform there was a particular focus on identifying submissions and consultations on the one hand and academic secondary material on the other.

The category ‘Submissions’ covered all the material that the ALRC had received that specifically responded to the reference. This included written statements received in response to a formal invitation for submissions, consultations conducted by the ALRC where the ALRC had engaged with stakeholders, and correspondence received by the ALRC. The category ‘Government Material’ related to sources cited by the ALRC that was authored by governments. This included annual reports of departments and agencies, past ALRC reports or other reports from law reform commissions, parliamentary committees and ad hoc inquiries. It also included administrative policies, guidelines, websites and community education material prepared by government entities. The ‘Primary Law’ category included cases, Acts of Parliament, Bills and delegated legislative instruments. It also caught citations to international law sources and the Hansard. The ‘Book’ category caught law textbooks, chapters in edited volumes and monographs from known presses. Self-published resources, especially from non-government organisations (‘NGOs’) were coded in the ‘Other’ category. The ‘Journal’ category included, but was not limited to, scholarly journals. Also included in this category were citations to papers from conferences or occasional papers from research entities. The last category ‘Other’ was a catch-all category for any citation that did not fall within the substantive categories. Citations in this category were generally to self-published materials from NGOs and newspapers.

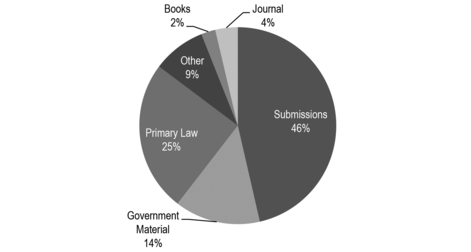

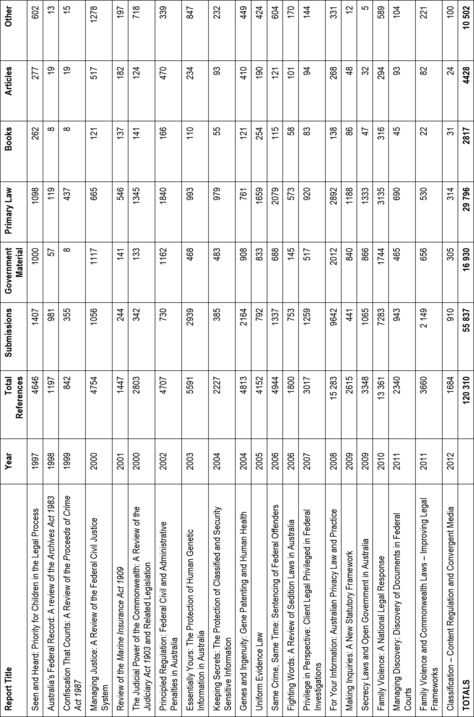

The complete data is provided in Table 3 in the Appendix. It is summarised in Figure 4. Figure 4 shows the totals for each category as a percentage of the total count of citations. It shows that 46 per cent of citations (55 837 out of 120 310) were to submissions made to the ALRC as part of the reference, or information provided to the ALRC as part of a consultation or correspondence within the reference. Figure 4 also shows that 25 per cent of all citations (29 796 out of 120 310) were to ‘Primary Law’ sources and 14 per cent (16 930 out of 120 310) to material produced by government. Also Figure 4 shows the limited recourse that the ALRC had to the academic literature. ‘Books’ and ‘Journals’ combined were 6 per cent (7245 out of 120 310). This percentage further diminishes when just focusing on refereed material. Within the citations categorised as ‘Journals’, 661 were non-refereed conference papers or occasional papers. This left 3764 or 3.1 per cent of the total citations to a recognised academic journal.

Figure 4: Categories by Percentage of Total Citations

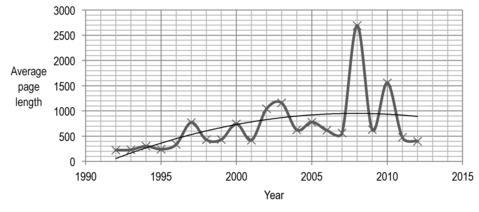

Before some broad conclusions can be drawn from Figure 4, some observations about the changes in formatting and style across the 42 reports are required. For the reports tabled in 1992, the average length was 224 pages. In 2011, the average length was 478.5 pages. However, in 2006, the average was 617. Figure 5 sets out the average report length by year. It tracks an increase in page numbers per report with a possible high-watermark with the 2008 For Your Information: Australian Privacy Law and Practice report and the beginning of a decline.

Figure 5: Average Page Length by Year

This pattern is not entirely explained by suggesting that the smaller page counts from 1992–96 were due to a higher concentration of technical law reform type reports. Instead, the change can be explained by looking at what the ALRC included in its reports. The content of the reports ballooned during the late 1990s and 2000s. In the 1992 Customs and Excise report, the ALRC received 368 written submissions but only 36 were referenced in the body of the report.[89] In the 2000 Managing Justice: A Review of the Federal Civil Justice System report, 272 submissions were received[90] and these were referenced 1056 times in the report. The raw number of citations per report increased over the sample period. In 1992–96, the average number of citations was 1571 per report. Recently, in 2009–12, the average number of citations was 4501 per report. However, in 1997–2008, the average number of citations per report was 9964.[91] Seemingly the reports got bigger because the ALRC began to put more and more content, which it cited, into the reports.

One explanation for the increase in content could be that the period 1997–2008 corresponds with the period where extensive changes in information and communications technology (‘ICT’) decreased the cost of information gathering and increased the volume of information available. The internet, the movement of legal, governmental and academic resources online, and the ability for consultations to be conducted digitally gave the ALRC significantly greater capacity to share, store and organise material.[92] There also were the efficiencies associated with word processing and digital publishing. In part these efficiencies underpinned the observed productivity increases over this period. Furthermore, it also potentially explains the ballooning of report sizes in 1997–2008 as evidence of the ALRC coping with ICT change. These reports can be seen as an institution grappling with the increase in information, the capacity to organise that information, and the decreases in the cost of research and writing that have come with the digital revolution. From this perspective, the comparatively slimmer recent reports could be understood as a maturing of the ALRC’s approach: from an attempt to capture and reproduce all the information gathered during a reference to greater confidence in deciding and prioritising significance.

Nevertheless, as a whole, there are several conclusions that can be drawn from Figure 4. The first, reflecting the data on page length, numbers of recommendation and the changes in the content of reports, is that there is some diversity between the reports concerning what the ALRC cited and in what frequency. In some reports over 80 per cent of the citations were to material coded as ‘Submissions’,[93] while in other reports this category comprised less than 20 per cent of the total citations.[94] At the other end of the scale there are four reports in which citations to the ‘Journal’ category represents more than 10 per cent of the total citations;[95] while there are five reports that do not cite any academic journal articles or conference papers.[96] In some reports more than 50 per cent of the citations were to primary legal material,[97] while 32.1 per cent of the citations in the 2009 Making Inquiries report and 25.9 per cent of the citations in the 2009 Secrecy Laws and Open Government report were to ‘Government Material’.[98] Many of the reports that had over 50 per cent of the citations as ‘Submissions’ can be categorised as concerning human rights,[99] while the reports where ‘Submissions’ comprised less than 20 per cent of the citations can be seen as more towards the technical law reform end of the reference spectrum with reports on evidence law, marine insurance, international transactions and choice of law having less than average citation to submissions.[100]

The second finding is that, notwithstanding this diversity, the reports reveal that the ALRC has significantly cited from legal and government sources. While submissions and consultations are particularly significant, the ALRC can be seen as drawing from other sources, especially primary law materials and material produced by government. Together these three sources account for 85 per cent of all the citations. This finding is not surprising. It would be expected that the ALRC would author reports that draw heavily on material provided to it as part of the inquiry process (‘Submissions’), reference legislation, bills, regulations, cases, international instruments and Hansard (‘Primary Law’), and policies, guidelines, memos and materials produced by government departments and agencies (‘Governmental Material’).

A third finding is the relatively low, compared to the other sources (6 per cent), citation rate to secondary academic material in the form of books, journal articles or conference proceedings. These traditional forums for the dissemination of research represented less than 10 per cent of all citations. This did not mean that academics were marginal players. In a number of reports, a submission made by an academic was frequently cited. For example, in Family Violence: A National Legal Response (2010), 81 citations were made to the submissions by Patricia Easteal,[101] while in the less referenced Classification – Content Regulation and Convergent Media (2012), Lyria Bennett Moses’ submission was cited six times.[102] In some reports secondary academic material was cited frequently. In Genes and Ingenuity: Gene Patenting and Human Health (2004),[103] the published work of Dianne Nicol was referenced 164 times, representing 40 per cent (164 out of 410) of the ‘Journal’ citations and 3.4 per cent (164 out of 4813) of the total citations in that report.[104] A feature in the referencing of Nicol was that 85 per cent (139 out of 164) of the citations were to a non-peer reviewed publication, an occasional paper from her affiliated research centre.[105] This shows the ALRC cites academic material that has entered the public domain outside of the traditional journal and book formats. In Review of the Marine Insurance Act 1909 (2001), 13.2 per cent (24 out of 182) of the entries in the ‘Journal’ category (and 1.6 per cent (24 out of 1447) of all references) were to a PhD thesis.[106] This is not to suggest that the ALRC did not in specific reports cite orthodox peer reviewed material but the actual numbers of citations to peer reviewed material was less than the 6 per cent.

In some reports, a specific article or book was cited relatively frequently. In the Review of Marine Insurance Act 1909 (2000), Howard Bennett’s The Law of Marine Insurance (1996)[107] was cited 27 times. This accounted for 19.7 per cent (27 out of 137) of the Books cited and 1.9 per cent (27 out of 1 447) of the total citations in that report. In the Secrecy Laws and Open Government in Australia (2009),[108] an article by John McGinness[109] was cited 12 times and an article by Leo Tsaknis[110] was cited seven times. Combined, these represented 59.3 per cent (19 out of 32) of the entries in the ‘Journal’ category, although only 0.5 per cent (19 out of 3348) of the total citations. This detail reinforces the overarching suggestion that material from academic sources has been used infrequently by the ALRC and when it has been used it has been highly selective.

Continuing with the citation to articles from law reviews, Table 4 lists the top 30 ranked entries in the ‘Journal’ category. With the growing emphasis on metrics and impact measurements in assessing legal scholarship, who reads and cites from which journals has become an important consideration for legal scholars and university administrators.[111] While secondary academic sources appear to have a low impact, in terms of frequency of citation, in ALRC final reports and members of the Australian legal academy appear to be able to contribute to ALRC inquiries more directly by making submissions, it is of interest to see which journals the ALRC has frequently cited.

Table 4: Frequency of Sources within Journal Category

|

Rank

|

Title

|

Frequency

|

ERA 2010

Rank[112]

|

Peer Reviewed

|

Origin

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1

|

Australian Law Journal

|

153

|

B

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

2

|

Criminal Law Journal

|

143

|

A

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

3

|

Centre for Law and Genetics Occasional Paper, University of Tasmania

|

139

|

N/A

|

No

|

Australia

|

|

4

|

Melbourne University Law Review

|

114

|

A*

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

5

|

Federal Law Review

|

92

|

A*

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

Sydney Law Review

|

92

|

A*

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

|

7

|

University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

83

|

A*

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

8

|

Alternative Law Journal/Legal Services Bulletin

|

66

|

B

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

9

|

Penalties: Policy, Principles & Practice in Government Regulation

Conference Sydney Australian Law Reform Commission 9 June 2001

|

62

|

N/A

|

No

|

Australia

|

|

10

|

Insurance Law Journal

|

57

|

C

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

11

|

Law Institute Journal

|

51

|

C

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

12

|

Law Society Journal

|

46

|

Not Ranked

|

No

|

Australia

|

|

13

|

Journal of Judicial Administration

|

44

|

B

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

14

|

Law Quarterly Review

|

43

|

A*

|

Yes

|

UK

|

|

15

|

Australian Journal of Family Law

|

42

|

A

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

16

|

Adelaide Law Review

|

41

|

B

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

17

|

PhD Thesis[113]

|

37

|

Not Ranked

|

Yes

|

Australia[114]

|

|

18

|

Journal of Law and Medicine

|

36

|

A

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

Privacy Law and Policy Reporter

|

36

|

Not Ranked

|

No

|

Australia

|

|

|

20

|

Monash University Law Review

|

35

|

A

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

21

|

Current Issues in Criminal Justice

|

34

|

B

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

Yale Law Journal

|

34

|

A*

|

Yes

|

USA

|

|

|

23

|

Australian Bar Review

|

33

|

C

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

European Intellectual Property Review

|

33

|

B

|

Yes

|

UK

|

|

|

25

|

Australian Journal of Administrative Law

|

31

|

B

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

26

|

Company and Securities Law Journal

|

29

|

B

|

Yes

|

Australia

|

|

Modern Law Review

|

29

|

A*

|

Yes

|

UK

|

|

|

28

|

Australian Institute of Administrative Law Forum

|

24

|

Not Ranked

|

No

|

Australia

|

|

Medical Law Review

|

24

|

A

|

Yes

|

UK

|

|

|

30

|

Canadian Bar Review

|

23

|

B

|

No

|

Canada

|

|

TOTAL

|

1706

|

|

|

|

|

There are four conclusions that seem to be suggested by Table 4. The first is that when the ALRC does cite an academic journal it most frequently does so from an Australian journal. The Australian Law Journal is at rank 1 with 153 citations. Indeed the top 14 ranked sources were Australian, with the highest ranked non-Australian journal the Law Quarterly Review at rank 14. Second, it is articles from law journals that the ALRC is citing. According to the codes used by the ARC, most of the journals in Table 4 were coded as belonging to the law ‘field of research’ (‘FoR1801’). The highest ranked non-1801 journal was Science at rank 40 with 18 citations.

The third finding reinforces the discrete nature of each report. The top 30 entries represent 38.5 per cent (1706 out of 4428) of all the entries in the ‘Journal’ category. The remaining 61.5 per cent of entries were to sources cited fewer than 23 times. This means that there were high numbers of unique sources; that is, citation to an article from a journal or conference paper only once. There were 373 unique sources, 151 with two citations and 77 with three citations. This suggests that the ALRC uses topic-specific sources for individual reports that were not used for other reports. Another example of this can be seen with the third ranking with 139 citations to the University of Tasmania Centre for Law and Genetics Occasional Paper. This ranking was achieved solely by Dianne Nicol’s and Jane Nielsen’s ‘Patents and Medical Biotechnology: An Empirical Analysis of Issues Facing the Australian Industry’[115] and only referenced in one report, Genes and Ingenuity: Gene Patenting and Human Health (2004).[116] The Insurance Law Journal (rank 9, with 57 citations) was only cited by the ALRC in Review of Marine Insurance Act 1909 (2001),[117] while the Privacy Law and Policy Reporter (rank 17, with 36 citations) was only cited in two volumes of For Your Information: Australian Privacy Law and Practice (2008).[118]

A final observation is the perceived ‘quality’ of the journals that the ALRC cited. A controversial part of the ARC’s Excellence for Research in Australia exercise in 2010 (‘ERA2010’) was the generation of a ranked list of academic journals.[119] Through a process of discipline consultation, the ARC ranked journals into a four-tier list. The highest quality journals were ranked A*, the next tier A and the final tiers B and C. An A* journal was recognised as ‘one of the best in its field ... [with] very high quality [papers]’ while a C journal was considered of low quality and held in low esteem by the research community and more likely to be a regional, professional or ‘trade’ journal.[120] While not too much emphasis should be given to the ERA2010 rank – given that the ARC moved away from it for subsequent ERA exercises – it does provide a public standard for considering the ‘quality’ of law journals. The ALRC’s citation to journals reveals an interesting mix. Four Australian A* journals from ERA2010 come in at rank 4–7. However, also within the top 15 are journals that the ARC in ERA2010 regarded as possessing less scholarly quality. The Australian Law Journal (rank 1), Alternative Law Journal (rank 8) and the Journal of Judicial Administration (rank 13) were Tier B journals, while the Insurance Law Journal (rank 10) and the Law Institute Journal (rank 11) were Tier C journals. A feature of all these last mentioned journals is that they publish smaller length articles of a topical or technical nature. This is further reflected in the use of non-peered reviewed sources. Within the top 30 ranked sources, 6 are non-peered reviewed. This suggests that the ALRC’s use of journals has been pragmatically informed; the ALRC has accessed and cited from what it has seen as relevant material without too much regard to the ‘academic quality’ of the source as indicated by peer reviewing or rankings on tables of journals.

The findings of the citation analysis suggest that the ALRC final reports are made up of many strands. That is not to say that the reports are uniform. What is cited depends on the reference, its breadth and whether the ALRC received a high number of submissions. Some general patterns can be identified. Submissions at 46 per cent of the total citations seem to be very significant to the ALRC. Further, this significance of submissions runs across the reports. Only in 31 per cent (13 out of 42) of reports were submissions not the most cited category.[121] At the other end of the scale citations to secondary academic material in the form of books, journal articles and conference papers were quite low at only 6 per cent of the total citations. It is these findings, particularly relating to the high submission count and the low academic material count that inform the analysis in Part V.

This Part discusses the findings from Part IV and articulates them in the context of the literature concerning institutional law reform. The findings suggest that the ALRC has had a strong commitment to the community engagement approach. However, within the literature on institutional law reform, there has been criticism of over-reliance on the community engagement approach. An alternative strategy can be seen in the Productivity Commission which appears to strike a different balance from the findings suggest that the ALRC does between the community engagement and the research institute approaches. This Part concludes by suggesting that the contemporary expectations for ‘evidence based’ reform might push the ALRC more towards the research institution approach.

The two key findings from the citation analysis – that 46 per cent of references within final reports are to submissions and that at most 6 per cent are to academic material – strongly suggest that the ALRC does law reform through a community engagement model. This should not come as a surprise. The ALRC, with Justice Kirby chairing community meetings in the 1970s,[122] was one of the pioneers of this approach to institutional law reform;[123] and over its history, there have been regular statements by ALRC commissioners advocating for a community engagement approach.[124] This past emphasis is continued in contemporary public statements by the ALRC. In its graphic of the law reform process reproduced on its website and in recent annual reports, community engagement in the form of consultations and call for public submissions are presented as the core deliberative stage for the law reform process.[125] The finding that 46 per cent of references within final reports are to sources that were coded as ‘Submissions’ suggests that these public statements are not puffery. Within the final reports, nearly half of the references are to material derived from the ALRC’s direct engagement with the community. As noted in Part II when introducing citation analysis, this data does not prove that the ALRC cited submissions in a wholly positive and approving way. What it does suggest is that the ALRC has gone to great lengths to represent to its readers that behind the reports there was a process of community engagement and that the recommendations should be implemented because of this engagement.

This finding immediately suggests a further question concerned with the identity of the entities in the community that the ALRC engaged with. Table 5 summarises from the sample the entities that have provided a submission to the ALRC or which the ALRC has listed as an entity that they consulted in a reference.[126]

Table 5: Submitters and Consultants Listed in ALRC Reports 1992–2012[127]

|

Sector

|

Type of Entity

|

Totals

|

Percentage

|

Sector Percentage

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Government

|

Federal/State and Local Departments, Agencies and Entities

|

1257

|

12

|

12

|

|

Law

|

Law Societies

|

161

|

1.6

|

|

|

Community Legal Centres

|

166

|

1.6

|

|

|

|

Legal Aid Commissions

|

77

|

0.70

|

|

|

|

Law Firms

|

113

|

1.1

|

|

|

|

Judges

|

204

|

2

|

|

|

|

Courts

|

84

|

0.8

|

7.8

|

|

|

Corporate/

Non-Law Professional

|

Peak/Representative Industry Bodies

|

508

|

4.9

|

|

|

Professional Organisation

|

200

|

2

|

|

|

|

Corporations

|

553

|

5.3

|

12.2

|

|

|

Community

|

Non-Government Organisations

|

1185

|

11.3

|

|

|

Religious Organisations

|

62

|

0.6

|

11.9

|

|

|

Research

|

Research and Teaching Institutions

|

118

|

1.1

|

|

|

Academics

|

166

|

1.6

|

2.7

|

|

|

Public

|

Confidential

|

1447

|

13.8

|

|

|

Individuals

|

4137

|

39.6

|

53.4

|

|

|

Total

|

|

10 438

|

100

|

100

|

From Table 5 it can be seen that the ALRC has received submissions from a range of stakeholders. Like the citation analysis, care needs to be taken when interpreting this data. The unique nature of each report, whether the report excited the wider public and the time and resources that the ALRC had for consultations, influenced who made submissions and in what quantity.[128] For example, the Making Inquiries: A New Statutory Framework (2009) report had a combined consultation and submission count of 84. This comprised 13 per cent government (11 out of 84), 6 per cent peak bodies (5 out of 84), 17 per cent NGOs (14 out of 84), 3.5 per cent law societies and legal aid commissions (3 out of 84), 20 per cent judges (17 out of 84), 6 per cent academics (5 out of 84) and 34.5 per cent members of the public (29 out of 84).[129] In contrast, Classification: Content Regulation and Convergent Media (2012) had a combined consultation and submission count of 2445. This comprised 1.64 per cent government (40 out of 2445), 1.43 per cent peak bodies (35 out of 2445), 1.47 per cent NGOs (36 out of 2445) 0.08 per cent community legal centres and law firms (2 out of 2445), 1.5 per cent corporations (37 out of 2445), 0.33 per cent religious organisations (8 out of 2445), 0.65 per cent research institutions and academics (16 out of 2445), 33.5 per cent confidential (819 out of 2445) and 59.4 per cent individuals (1452 out of 2445).[130]

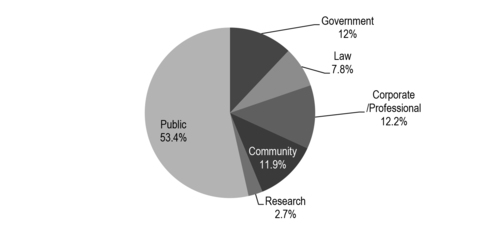

Figure 6 sets out the submission by sector. From Figure 6 it can be seen that the highest source of submissions and consultations were from the ‘public’ at 53.4 per cent; comprising 13.8 per cent (1447 out of 10 438) confidential and 39.6 per cent named individuals. By ‘public’ the contributor was an individual in their private capacity. The next rank was occupied by a three-way tie of government with 12 per cent, corporate and non-law professional bodies with 12.2 per cent and ‘community organisations’ with 11.9 per cent. The legal sector at 7.8 per cent and the research sector at 2.7 per cent filled the bottom ranks. These rankings remain unchanged even if the outlying data provided by the Classification: Content Regulation and Convergent Media (2012) is excluded. Without that report, the public remains the highest source of submissions and consultations at 33.6 per cent (2685 out of 7993).

Figure 6: Submission by Sector

The data provided in Table 5 and Figure 6 concerns the bare listing of entities that the ALRC acknowledged to have contributed to an inquiry. It is not an analysis of which submissions the ALRC cited in its reports. So while the question of influence is not answerable by this data, what it does provide is that the ALRC reports from 1992 to 2012 record engagement with entities from the government, corporate, law, community and research sectors. It also has records that 53.4 per cent of the submissions that it has received has been from individuals in their private capacity. This is not to suggest that the final reports are simple conduits for stakeholder perspectives. The reports are arranged by chapters that reflect an issue or a cluster of issues and 54 per cent of all the references are to texts other than submissions. Nevertheless, the weight of text given by the ALRC to submissions in its reports – on average there has been 2.5 citations (55 837 out of 22 176) to submissions on every page – is significant evidence substantiating the ALRC’s longstanding claim that its approach to law reform is through community consultation.

As has been identified within the secondary literature on institutional law reform, there are some concerns with the community engagement approach. An immediate criticism concerns the ‘community-ness’ of the entities that the ALRC has engaged with. Within the advocacy literature on institutional law reform, community engagement has been framed in terms ranging from the instrumental ensuring ‘law remains relevant and useful to people’[131] to ‘a form of civic conversation’[132] inspired by ‘[d]eliberative [d]emocracy’.[133] The focus of these justifications concern law reform connecting with law’s human subjects and the discussion within the literature often moves onto strategies for engaging marginal and under-represented individuals.[134] Table 5 reveals that the ALRC engages significantly with organisations. Governments, corporations, the non-profit sector, representative and peak bodies make up 46.4 per cent of the consulted ‘community’. On the whole, for the sample period, the ALRC engagement strategies can be seen as relatively passive; targeted consultations with identified stakeholders followed by the public releasing of issues and discussion papers and then receiving submissions.[135] While during the sample period the ALRC did start to adopt social media technologies and organised some public forums,[136] there was little evidence of proactive processes in gathering opinions and perspectives directly from marginal and under-represented individuals.[137] Graycar’s concern that the established passive methods of community engagement used by law reform commissions tends to select mainstream and established interests, who are recognised as ‘stakeholders’ and who have the resources and expertise to draft submissions, does seem to be valid looking at the sample.

This finding supports Graycar’s concern of law reform by frozen chook. In so heavily relying on submissions within its final reports and in having nearly 46.6 per cent of the submissions that it receives drawn from organisations, it could be suggested that the ALRC’s law reform activities involve the channelling of vested and mainstream opinions. In looking at these figures, the ALRC does run the risk of giving the appearance of a particular version of agency capture. The Hon Michael Kirby wrote that law reform commissions needed to be mindful of ‘one-sided lobbying’.[138] The spectre of frozen chooks is that the community engagement approach can be compromised, or give the impression of being compromised, by vocal stakeholders. Over the nearly 40 years of the ALRC, business, community and other groups have become much more sophisticated in their marketing, media profiles and abilities to mobilise resources and make submissions. Indeed, there have emerged organisations, which have as a purpose to interface with the sort of community engagement opportunities that the ALRC offers.[139] The entities listed in Table 5 suggest that many of these organisations are engaging with the ALRC.

This study neither dispels the criticism that the ALRC does law reform by frozen chook nor confirms it. In no report within the sample could it be seen that the ALRC was particularly relying on a single submission or cluster of related submissions. Further, there is evidence from the sample that suggests that the ALRC does not simply adopt the perspective of vocal and well-organised interests. The majority of the submissions to Classification: Content Regulation and Convergent Media (2012) were from individual gamers demanding restriction-free computer games, however that was not the ALRC’s recommendation.[140] This possibly tells a deeper story. The overall findings of this study substantiate the ALRC’s claim to undertake law reform through community engagement. Yet in an inquiry that did generated significant interest from a usually under-represented group from the community – computer gamers[141] – their perspective, while acknowledged, was not adopted. While this is evidence of the ALRC’s independence from some of its submitters, it also suggests that the ‘community’ to which it listens seriously are mainstream organisations.

For Graycar, the corrective of law reform by frozen chook is not more or better consultation but independent scholarly research.[142] In the terminology of the literature on institutional law reform she can be seen as arguing more for a research institute approach that draws its findings from independent research and rigorous scholarship into the issues. An expected hallmark of this approach would be detailed engagement with scholarly literature, which would be clearly identified in a citation analysis. The findings of this study that only 6 per cent of the total citations were to academic sources reveals that the ALRC has not overtly balanced its community consultation approach with recourse to published research and scholarship.

There might be a simple explanation for the imbalance between submissions and secondary academic citation rates. In the ALRC’s defence it could be argued that for many of the references there was not a wide or deep relevant body of secondary academic literature. This could be an explanation for the reports in the sample from the early 1990s such as Administrative Penalties in Customs and Excise (1992)[143] and Child Care for Kids (1994)[144] where no secondary academic sources were cited.[145] However, this does not explain the differences between citation of submissions and secondary academic material in more contemporary reports. The recent family violence reports, Family Violence: A National Legal Response (2010)[146] and Family Violence and Commonwealth Laws: Improving Legal Frameworks (2011),[147] were set against a backdrop of a sizable and dynamic secondary academic literature on the legal, social and economic contexts of domestic violence in Australia. However, in these reports the citations were still dominated by references to submissions. For Family Violence: A National Legal Response (2010), 54.5 per cent (7283 out of 13 361) of the citations were submissions with only 4.5 per cent (610 out of 13 361) to secondary academic sources; and for Family Violence and Commonwealth Laws: Improving Legal Frameworks (2011), 59 per cent (2149 out of 3660) of the citations were to submission and only 2.8 per cent (104 out of 3660) to secondary academic sources. While academics have been active within the ALRC, as presidents, commissioners, consultants and submitters, when it comes to final reports, the ALRC gives priority to the texts generated by the ‘community’ in the inquiry process.

The ALRC is not the only entity engaged in law reform at the Commonwealth level. There exists, in the words of past President of the ALRC David Weisbrot, a ‘crowded field’.[148] Since 1975, there have emerged many permanent, semi-permanent and ad hoc commissions, committees and inquiries into Commonwealth laws. There also has been much greater ALRC-like law reform activity from parliamentary standing committees,[149] and royal and non-royal commissions of inquiry into Commonwealth law and administration have been regularly established.[150] Some of the most controversial and wide-ranging reforms to Commonwealth law over the past decades have not been from ALRC reports. The establishment and review of the national scheme to regulate human cloning and embryonic stem cell research has been achieved through a series of inquiries and reports; one by the National Health and Medical Research Council,[151] three separate parliamentary committees,[152] and two ad hoc Legislation Review Committees.[153] Similarly, the recognition of same-sex relationships by the Commonwealth[154] followed an Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission report.[155] This is notwithstanding the ALRC history and track record in health and bioscience law reform[156] and rights-based law reform.[157]

However, the most prominent ‘law reform’ entity in recent times has been the Productivity Commission. As can be seen in Table 6 the Productivity Commission dwarfs the ALRC.

Table 6: Comparison between Productivity Commission and ALRC for 2011/12

|

Indicator

|

Productivity

Commission[158]

|

ALRC[159]

|

|

Budget

|

$37.96 million

|

$2.9 million

|

|

Budget Trend from 2011

|

+0.677 million

|

-0.225 million

|

|

Staffing

|

197 equivalent fulltime

|

14.5 equivalent fulltime

|

|

Completed Reports

|

17 (9 public inquiries and 8 research studies)

|

2

|

|

Ongoing Inquiries

|

7

|

0 (2 were completed and 2 new referenced received in 2011/12)

|

|

New References

|

10

|

2

|

If size, budget trend and workload denote success then there is an argument that the Productivity Commission is more successful than the ALRC. However this is not entirely fair. The Productivity Commission has a general remit to report ‘about matters relating to industry, industry development and productivity’[160] which is potentially a wider jurisdiction than the law and legal system focus that is set out for the ALRC in its Act.[161] These statutory differences reflect the departmental alignment of the Productivity Commission and the ALRC. The Productivity Commission operates under the auspice of the Treasury and its general ambit reflects the whole of the economy and whole-of-government focus of the Treasury, while the ALRC’s relationship with the Attorney-General means that the ALRC tends to only receive references that fall within the Attorney-General’s Department’s specific responsibilities. While the Keating Labor Government did give the ALRC references concerning legislation administered by other departments,[162] this can be seen as unusual. For the period 1992 to 2012, most reports related directly to core responsibilities of the Attorney-General’s Department, such as federal courts and their processes, crime and violence in the community and regulating information in the contexts of privacy and censorship.[163] In contrast, the Productivity Commission’s reports range from gambling[164] to disability care and support,[165] international trade[166] and climate change.[167] The size, scope and activity between the two commissions can be explained in terms of their aligned departments.

But it also could be explained in terms of their approaches. At one level, the Productivity Commission and the ALRC can be seen as adopting very similar approaches. Both involve consultation and submission processes and the production of issues papers and draft reports in accordance with the community engagement approach. Both end with a substantial final report containing a list of recommendations. However, there are some clear differences between the final reports. The Productivity Commission produces and analyses its own data. The appendixes to its reports contain economic modelling supporting the recommendations. This sort of data crunching is absent from the ALRC reports. Indeed, economics, even law and economic journals, are rarely cited by the ALRC, comprising 0.15 per cent (7 out of 4428) of the total citations to journals or conference proceedings.[168] This analysis of data continues to how the Productivity Commission deals with submissions and consultations. As this study has identified, the ALRC uses submissions in its final reports as texts to be referenced. This is the ALRC taking seriously its community engagement model. By citing the stakeholder’s submission, the ALRC feels that it is respecting the submitter through showing that its submission has been read and considered. The zenith of this approach can be seen in the family violence reports. For example, in Family Violence – A National Legal Response (2010), the proposal that harm to animals should be included in the understanding of ‘family violence’ was explained as:

supported by the great majority of stakeholders, including victims of family violence who recounted personal stories of having pets threatened, stolen and tortured; and legal service providers who reported cases of violence against pets as a form of violence against their clients.[169]

This statement was footnoted, and in the footnote, 22 different submissions were cited. In contrast, the Productivity Commission in its final reports can be seen to cite submissions differently. For example, in the Paid Parental Leave: Support for Parents with Newborn Children (2009) report,[170] it received over 400 submissions, over 500 feedback emails and conducted extensive consultations and public hearings.[171] However, the report is not presented as constructed from these texts. Absent are the lengthy footnotes citing separate submissions that have been a characteristic of the ALRC reports. Instead, the Productivity Commission analyses and summarises submissions as a discrete data set. In its own words, its report ‘seeks to assess the public submissions and the relevant literature for insights and evidence, to see what they tell us about good rationales and achievable objectives’.[172] Generally ‘submissions’ are written about in the plural with one or two specific submissions cited as exemplars.[173] The report presents that there has been analysis of all submissions received by the Commission and what has been identified are themes. When submissions are cited, they are not direct authorities for a point; rather, they are authorities for an issue that is then examined using other data.

For example, in the Paid Parental Leave: Support for Parents with Newborn Children (2009) report, the Productivity Commission used submissions to identify a theme concerning the risks to health and wellbeing of mothers and infants when a mother returns to work.[174] Several of these submissions were summarised in an in-text box.[175] However, having identified the concern, the Commission then discussed it using statistics concerning return to work rates and examined Australia, UK and USA from secondary academic sources on the time it takes new mothers to recover from the birth and newborn period, the productivity of women returning to work after different maternity leave periods and the health and wellbeing of mothers and infants from different maternity leave periods. It concluded:

the evidence suggests that recovery from pregnancy and childbirth and the return to full functionality can be prolonged. There also appears to be a positive relationship between the length of maternity leave in the short term and maternal health and wellbeing.[176]

What is suggested by this examination of a Productivity Commission report is that on the gradient of approaches to institutional law reform, the Productivity Commission is more towards the research institute model and the ALRC towards the community engagement approach.

While MacDonald identified the community engagement model as emerging from criticisms of the research institute approach in the 1970s, the Productivity Commission’s prominence as a source of Commonwealth-level law reform does suggest that in the 2010s there has been a restoration of faith in rationality and ‘human artifice [in] ... improving the material conditions of society.’[177] It can be seen that the Productivity Commission reports generate authority through discussion of the ‘evidence’, the production and analysis of data and the provision of numbers and graphs. Its ‘success’ cannot just be explained in terms of alignment with a larger and more dominate department, but that its reports seem more in tune with an era of ‘evidence-based policy-making’.[178] Although not without its own critical literature,[179] the Productivity Commission’s approach does seem to strike a different balance between the community engagement and the research institute approach.

The ALRC can be seen to be making steps in this direction. In the recent Classification – Content Regulation and Convergent Media (2012) reference, the ALRC undertook two activities that are more consistent with a research institute approach. First, it undertook a qualitative thematic analysis of the submissions it received.[180] Secondly, it commissioned social scientific research into community attitudes to ‘higher level media content’.[181] What these undertakings allowed was the final report to be more focused and streamlined. The ALRC was able to refer to the findings from those studies as evidence of contemporary community attitudes towards challenging media content.[182] This was only a small step towards the research institute approach, for the bulk of that report still evidenced the in-text sifting through of individual submissions with an above average of 54 per cent (910 out of 1684) of the citations in that report to submissions. However, what it does show is the ALRC incorporating, to a much greater degree than in the other reports in the sample, a more research institute approach.

This article reports a study into the citation patterns of the ALRC in its final reports from 1992 to 2012. It found that in its final reports the sources that the ALRC most cited were submissions and consultations. This finding substantiates the ALRC’s claim that its approach to law reform is through community engagement. However, this approach also has its risks. The study also found that a low citation count to secondary academic material. The challenge for the community engagement model is the problem of the anecdotal becoming prioritised over representative data. In an era of ‘evidence-based policy’, the Productivity Commission’s more research institute approach demonstrated by more engagement with secondary academic material in the final reports and its own data gathering and analysis activities suggests an alternative balance between ‘community’ and ‘research’ for law reform.

[*] BSc, LLB (Hons), PhD, Senior Lecturer, Griffith Law School, Griffith University.

This research was funded under the Griffith University New Researcher Grant Scheme. I would like to thank Damien Martin, Emanuele Gelsi, Ryan Anderson and Emma Wagstaff for their careful research assistance. Preliminary data from this study was presented at the 2012 Australasian Law Reform Agencies Conference, Australian National University, College of Law, Canberra, 14 September 2012. A further draft of this paper was workshopped with staff from the ALRC in Sydney on 21 February 2013. I would particularly like to thank President Professor Rosalind Croucher, Commissioner Professor Jill McKeough, Bruce Alston and other staff for their comments and feedback on the draft. Nevertheless, the opinions, representations and mistakes in this paper are my own and not that of the ALRC.