University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

(FAILED) VOLUNTARY EUTHANASIA LAW REFORM IN AUSTRALIA: TWO DECADES OF TRENDS, MODELS AND POLITICS

LINDY WILLMOTT[*], BEN WHITE[**], CHRISTOPHER STACKPOOLE[***], KELLY PURSER[****] AND ANDREW MCGEE[*****]

Euthanasia remains a topical issue in Australia. Legislative attempts

to reform the law occur regularly. In 2013 alone, three Bills seeking to

legalise voluntary euthanasia (‘VE’) or physician-assisted suicide (‘PAS’) were introduced into different state parliaments;[1] and two issues and background papers were written to inform those debates.[2] In June 2014, the Australian Greens Senator and now leader of that party, Richard Di Natale, released an exposure draft of a Bill for consultation which would enable an Australian resident to receive assistance to die.[3] In May 2015, the Victorian Legislative Council directed the Standing Committee on Legal and Social Issues to report on the need for laws to allow citizens to make ‘end-of-life choices’ (a reference that is sufficiently broad to include VE and PAS). Most recently, in December 2015, Senator David Leyonhjelm from the Liberal Democratic Party introduced a Bill into the Senate seeking reform in this field.[4] VE and PAS also became a critical policy platform for political parties during the 2013 federal election.[5] Discussion of these issues remains prevalent in the media.[6] In part, this is fuelled by the not infrequent prosecutions of family members, friends and medical practitioners who have been involved with the death of persons who were terminally ill or who otherwise requested assistance to terminate their own life.[7]

This issue is also topical internationally, as we witness a trend towards the legalisation (or decriminalisation) of VE and PAS. There has been legislative reform in the Netherlands,[8] Belgium,[9] Luxembourg,[10] the United States (Oregon,[11] Washington,[12] Vermont[13] and California)[14] and in Canada (Quebec).[15] Assisting another to die is also lawful in Switzerland provided the assistance is not given for ‘selfish motives’.[16] Last year, the Canadian Supreme Court held unanimously that criminal law provisions prohibiting physician assistance in dying contravened rights conferred by the Canada Act 1982 (UK) c 11, schedule B part I (‘Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms’).[17] In some jurisdictions, such as in British Columbia in Canada[18] and the United Kingdom,[19] VE and PAS have been the subject of specific prosecutorial guidelines.

Within Australia, there have been many attempts to pass VE legislation. From 16 June 1993[20] until the date of writing, 51 Bills have been introduced into Australian parliaments dealing with legalising VE or PAS.[21] Despite these numerous attempts, the only successful Bill was the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995 (NT) (‘ROTTIA’), which was enacted in the Northern Territory, but a short time later overturned by the controversial Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth). Yet, in stark contrast to the significant political opposition, for decades Australian public opinion has overwhelmingly supported law reform legalising VE or PAS.[22]

While there is ongoing debate in Australia, both through public discourse[23] and scholarly publications,[24] about the merits and dangers of reform in this field, there has been remarkably little analysis of the numerous legislative attempts to reform the law, and the context in which those reform attempts occurred. The aim of this article is to better understand the reform landscape in Australia over the past two decades. The information provided in this article will better equip Australians, both politicians and the general public, to have a more nuanced understanding of the political context in which the euthanasia debate has been and is occurring. It will also facilitate a more informed debate in the future. The article seeks to achieve this aim by considering two separate but related aspects of the reform attempts.

First, in Part III, the authors chart the many legislative attempts to reform the law over the previous two decades (including the circumstances surrounding the passage of the Northern Territory legislation and its demise when overturned by the Commonwealth Government), and the jurisdictions in which these reform attempts are occurring. Part III then considers some political dimensions of the debate including who has been proposing reform, relevant political affiliations and the role, more broadly, that party politics has played in the past and may play in the future. That Part also provides a detailed analysis of how far the Bills progressed through parliaments and how they were disposed of. Finally, through an analysis of parliamentary records, the authors have identified which Bills came close to passing, and comment on whether any conclusions can be drawn from the fact that these particular Bills had a greater level of political support.

The second way in which this article seeks to deepen understanding is through an in-depth examination of the 51 Bills. If there is to be legislative reform in Australia, there will and should be close scrutiny and debate about the details of the Bills. As we shall see in Part IV, there can be significant variation in the content of the legislative proposals which affects, in important ways, how the regimes would operate. Decisions made about the content of the Bill will affect issues such as eligibility criteria (restricted to adults with capacity who are terminally ill and seek assistance to die, or available to a broader cohort), safeguards (involvement of treating doctor only, or should other specialists be involved), and state oversight (should each death be independently reviewed to ensure compliance with the regime, and should such review be prospective or retrospective). Yet, to date, there has not been a comprehensive analysis of how the Australian Bills have dealt with these and other issues. We do not know whether there has been general consensus or diversity on these and other critical points in the Bills to date. A consensus in some areas but variation in others, if this is the case, may signal the issues on which there might be particular focus when these Bills are debated in future years. Part IV analyses in detail the various legislative models and notes those areas of convergence and divergence. In this analysis, particular mention is made of the features of the Bills identified in Part III as ‘close to passing’. In Part V, the authors make some concluding remarks about the Australian reform experience to date, and speculate about the implications that this may have for reform attempts in the future.

We begin, however, in Part II, by defining frequently used terms. In this debate, people can be at cross-purposes because of different understandings of the same term. It is important to clarify what we mean in this article when we use various terms.

Both in Australia and overseas, the VE and PAS debates have been undermined by semantic ambiguity. We therefore seek to clarify what we mean when we refer to the terms included in the table below.[25]

Table 1: Terminology

|

Term

|

Meaning

|

Example

|

|---|---|---|

|

Euthanasia

|

For the purpose of relieving suffering, a person performs a lethal

action[26] with the intention of

ending the life of another person

|

A doctor injects a patient with a lethal substance to relieve that person

from unbearable physical pain

|

|

Voluntary euthanasia (‘VE’)

|

Euthanasia is performed at the request of the person whose life is ended,

and that person is competent

|

A doctor injects a competent patient, at their request, with a lethal

substance to relieve that person from unbearable physical pain

|

|

Competent

|

A person is competent if he or she is able to understand the nature and

consequences of a decision, and can retain, believe, evaluate,

and weigh

relevant information in making that decision

|

|

|

Non-voluntary euthanasia

|

Euthanasia is performed and the person is not competent

|

A doctor injects a patient in a post-coma unresponsive state (sometimes

referred to as a persistent vegetative state) with a lethal

substance

|

|

Involuntary euthanasia

|

Euthanasia is performed and the person is competent but has not expressed

the wish to die or has expressed a wish that he or she does

not die

|

A doctor injects a competent patient who is in the terminal stage of a

terminal illness such as cancer with a lethal substance without

that

person’s request

|

|

Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining

treatment[27]

|

Treatment that is necessary to keep a person alive is not provided or is

stopped

|

Withdrawing treatment: A patient with profound brain damage as a

result of a heart attack is in intensive care and breathing with the assistance

of a ventilator, and a decision is made to take him or her off the ventilator

because there is no prospect of recovery

Withholding treatment: A decision is made not to provide nutrition

and hydration artificially (such as through a tube inserted into the stomach)

to

a person with advanced dementia who is no longer able to take food or hydration

orally

|

|

Assisted suicide

|

A competent person dies after being provided by another with the means or

knowledge to kill him- or herself

|

A friend or relative obtains a lethal substance (such as Nembutal) and

provides it to another to take

|

|

Physician-assisted suicide (‘PAS’)

|

Assisted suicide where a doctor acts as the assistant

|

A doctor provides a person with a prescription to obtain a lethal dose of a

substance

|

This Part of the article analyses the many attempts to reform euthanasia law in Australia’s states and territories. It commences with a detailed consideration of the first attempts to introduce VE laws and the circumstances surrounding the enactment of the Northern Territory legislation and its overturn, and then provides an overview of all reform attempts in Australia. Importantly, this Part extends beyond a description of the legislative attempts and unpacks some of the politics associated with the euthanasia reform efforts: political affiliations of proponents, voting trends of members of parliament (along party lines or not) and, more generally, the role politics has played in euthanasia reform in Australia. Next, this Part charts how far the various Bills progressed, and identifies seven Bills that garnered the most political traction. Based on identification and analysis of these seven Bills, this Part concludes with some observations and speculation about what factors may be influential in achieving reform.

The first VE Bill introduced into any Australian parliament was the Voluntary and Natural Death Bill 1993 (ACT). The Bill was introduced into

the Legislative Assembly of the Australian Capital Territory by Michael

Moore (independent) on 16 June 1993.[28] The Bill was designed to achieve three purposes: (a) to facilitate VE in limited circumstances;[29] (b) to permit a doctor to withhold or withdraw treatment in limited circumstances;[30] and (c) to enable a person to give a direction about future treatment to operate when that person becomes incompetent.[31] When the Bill was introduced, the matter was referred to the Select Committee on Euthanasia, chaired by Michael Moore, whose report was tabled in Parliament on 14 April 1994.[32] The Select Committee concluded that it would not be appropriate[33] and politically inopportune[34] to pass legislation to allow for VE, and the Bill was discharged from the notice paper by Michael Moore on 11 May 1994[35] prior to the 1995 election.[36] In coming years, Michael Moore would introduce into the Legislative Assembly four further Bills to legalise or decriminalise euthanasia.[37]

On 22 February 1995, soon after the discharge of the Voluntary and Natural Death Bill 1993 (ACT), the Chief Minister of the Northern Territory, Marshall Perron,[38] tabled a private member’s Bill to legalise VE and PAS.[39] On the same day, that Bill was referred to a Northern Territory Select Committee on Euthanasia for consideration.[40] The report of the Committee, which was tabled in May 1995, provided no specific recommendations regarding whether legislation permitting VE should be introduced, although it recommended amendments to the initial Bill.[41] On 24 May 1995, Marshall Perron resigned as Chief Minister, indicating that he did not want his position to influence the manner in which the members of his party voted. After extensive debate, the Assembly divided and on a vote of 13:12, the Bill passed the second reading stage.[42] After a debate extending into the early morning of 25 May 1995, the Bill passed the committee stage and third reading on a vote of 15:10.[43] With the enactment of the ROTTIA, the Northern Territory became the first, and only, jurisdiction within Australia to introduce legislation for VE. It also became the first jurisdiction in the world to establish a legislative regime that permitted the practice.

However, the ROTTIA did not last long on the statute book. On 9 September 1996, Liberal Party member, Kevin Andrews, introduced into the Commonwealth Parliament the controversial Euthanasia Laws Bill 1996 (Cth) which sought to amend the territories’ Self-Government Acts[44] to deprive them of their capacity to pass VE or PAS legislation.[45] Despite serious remonstrations by the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory Governments, on

9 December 1996, the Euthanasia Laws Bill 1996 (Cth) passed the second reading stage 90:39,[46] and passed the committee and third reading stages with a resounding 88:35 majority.[47] The Bill was introduced into the Senate on

12 December 1996 by Senator John Herron of the Liberal Party.[48] On 24 March 1997, the Bill passed the second reading[49] and third reading stages without amendment 38:33.[50] The Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth) came into effect on

27 March 1997,[51] amending the territory Self-Government Acts and dismantling the ROTTIA. Since the passage of the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth), there have been six unsuccessful attempts by members of the Australian Democrats[52] and Australian Greens[53] to remove the limitation on the legislative power of the territories. Most recently, in December 2015, a member of the Liberal Democratic Party introduced a Bill into the Senate seeking to do the same.[54]

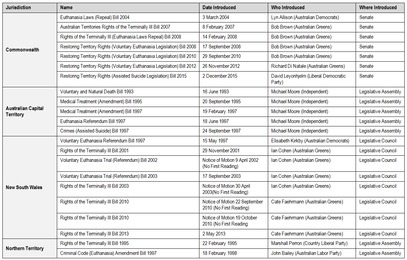

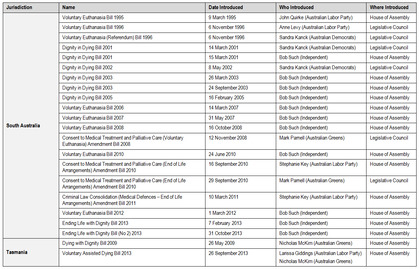

There have been 51 Bills introduced into the various Australian parliaments since 1993. The names of these Bills, when, where and by whom they were introduced are listed in the Appendix. Seven of these Bills sought to remove the prohibition on territories legislating in this area and a further five sought to hold a referendum on law reform. The remaining 39 Bills proposed a model for law reform permitting VE and/or PAS.

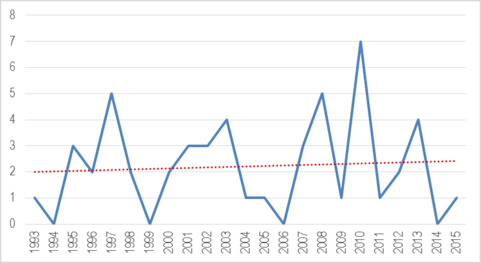

Figure 1 provides a graphic illustration of the number of these VE Bills introduced and the year of their introduction.

Figure 1: Number of VE/PAS Bills Introduced into Australian Parliaments

As demonstrated by the trendline,[55] the number of Bills introduced has been progressively increasing. The increasing trend is significant having regard to the fact that, since 1997, no Australian territory has been able to introduce a VE Bill due to the effect of the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth). Furthermore, between 1993 and 1997, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory introduced two and five VE Bills respectively into parliament, in contrast to the states’ and Commonwealth’s average of 0.67[56] Bills per jurisdiction over this same five-year period. The territories, rather than the states, were more active in introducing VE initiatives prior to the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth). Indeed, the significant decline in the number of Bills introduced between 1998 and 1999 directly correlates with the reduction in legislative attempts in the territories’ parliaments. Since 1998, the states and the Commonwealth have assumed a more active role in introducing an average of 2.22 Bills each year.[57] Since 2007, the average has increased to 2.7 Bills each year across Australia.[58] South Australia (20), New South Wales (8) and Western Australia (6) have led the states in introducing VE Bills. Tasmania has introduced two VE Bills, Victoria has only introduced one Bill, and Queensland is the only jurisdiction never to have introduced a VE or PAS Bill. There have been seven attempts at a federal level to abolish the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth).

The politics of euthanasia law reform – in particular, the extent to which euthanasia has been a political issue and the reason that this has (or has not) been the case – has received remarkably little attention in the Australian literature.[59] This article does not aim to fill that gap in the literature, but in this section, we provide information about the political positions taken (or not taken) by Australian political parties, as well as the political affiliations of those members of parliament who have proposed reform. We provide an analysis of some of the voting patterns that have occurred, and make some observations about the political nature of the debate in Australia and the implications of this on the likelihood of reform.

Despite the ongoing and sustained media attention on VE and public support for reform, the largest political parties in Australia, the Liberal Party, the Australian Labor Party and the National Party, have not developed policy positions on the topic. This is in stark contrast to other parties that have deemed this to be an issue that should not be ignored. The Australian Greens have consistently supported VE since the party was formed in 1992, its policy being in favour of allowing terminally ill patients to seek assistance to die from their doctor.[60] Historically, the Australian Democrats have also supported reform of the law,[61] and more recently, the Australian Sex Party and the Liberal Democratic Party. Both the Christian Democratic Party and the Family First Party have adopted a position at the other end of the spectrum, and are strongly opposed to legalising VE.

The table below provides a breakdown of the VE Bills by affiliation of the proponent to a political party, if any, as well as by jurisdiction.

Table 2: Voluntary Euthanasia Bills by Political Affiliation of Proponent and Jurisdiction

|

|

Cth

|

ACT

|

NSW

|

NT

|

SA

|

Tas

|

Vic

|

WA

|

Total

|

|

Number of Bills introduced

|

7

(14%)

|

5

(10%)

|

8

(16%)

|

2

(4%)

|

20

(39%)

|

2

(4%)

|

1

(2%)

|

6

(12%)

|

51

(100%)

|

|

Political Affiliation of Proponent

|

|||||||||

|

Independent

|

0

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

11

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

16

(31%)

|

|

Australian Democrats

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

9

(18%)

|

|

Australian Greens

|

5

|

0

|

7

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

18

(35%)

|

|

Australian Labor Party

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

5

(10%)

|

|

Country Liberal

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

(2%)

|

|

Liberal Democratic Party

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

(2%)

|

|

Australian Greens –Australian Labor Party Joint Bill

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

(2%)

|

|

* All VE Bills introduced into Australian parliaments have been private

members’ Bills.

|

|||||||||

As can be seen, the independents and the members of the Australian Greens and the Australian Democrats have been the major proponents of VE reform. The Australian Greens introduced their first VE Bill in 2001 in New South Wales, and have accounted for 37 per cent of all VE Bills introduced in parliaments across Australia,[62] while the Australian Democrats have introduced 18 per cent. Independent members have been responsible for the introduction of 31 per cent of VE Bills. While this might seem significant, all independent VE Bills have been introduced by only two individuals, Michael Moore and Dr Bob Such. Indeed, it would seem that VE has primarily been the responsibility of individual members of parliament, with only 21 individuals having introduced all 51 Bills over the past 20 years. Only six Bills have been introduced by Australian Labor Party members.[63] Significantly, only one Bill has been introduced by a member of a conservative political party, Marshall Perron, when he introduced the ROTTIA, the only Bill within Australia to have been successfully enacted.

Regardless of whether a political party has developed a policy position on VE or, if one has been developed, the stance taken, all parties have universally allowed conscience votes on the matter of VE. Nevertheless, there appears to be a strong correlation between party affiliation and voting preferences, and indeed, many decisions are determined virtually according to the chosen party lines.[64] For example, in relation to the Euthanasia Referendum Bill 1997 (ACT), every Australian Labor Party member voted against the Bill, and every Liberal Party member (except one) voted against the Bill.[65] Similarly, every Liberal and Australian Labor Party member voted against the Crimes (Assisted Suicide) Bill 1997 (ACT), a Bill that significantly mitigated penalties for medical practitioners engaging in VE, while every Australian Greens member supported the Bill.[66] Similarly, when the Voluntary Euthanasia Trial (Referendum) Bill 2003 (NSW) was introduced, every Australian Greens and Australian Democrat member voted in favour of the Bill, and every member from the Liberal and Labor Parties voted against the Bill.[67] The same occurred when voting on the Voluntary Euthanasia Referendum Bill 1997 (NSW).[68] Furthermore, in both the Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2013 (Tas) and the Rights of the Terminally Ill Bill 2013 (NSW), all members of the Liberal Party voted against the proposed VE regimes.[69] In recent times, Australian Labor Party members are more likely to have an even distribution of votes, but the tendency has continued for members of conservative political parties to vote against VE Bills.[70]

The apparent influence of political allegiances on voting practices raises the broader question of what role politics currently plays in euthanasia law reform in Australia, and will play in the future. As evident from the above, a range of political coalitions have formed. The most common coalition (in favour of VE reform) is the Australian Greens and Democrats, frequently supported by sympathetic independents. Parties with direct religious affiliations forming the foundation of their policies, such as the Family First and Christian Democratic Parties, have universally opposed the passage of VE legislation. While the Liberal and Australian Labor Parties allow conscience votes, Liberal Party members are more likely to oppose VE, and Australian Labor Party members are more likely to have an even distribution.

The role that politics will play in future attempts to reform euthanasia in Australia is an interesting question in a country where the major political parties are secular and whose policy positions are, for the most part, not born of religious influence. As we have seen, the Liberal, Labor and National Parties do not have a formal position on euthanasia, so this issue is not one in which any of these parties can differentiate themselves from one another in the electorate. It is likely that none of these parties perceive that any political advantage will be gained by making euthanasia law reform a political issue.[71] While the Christian Democratic Party has a policy that stems from its religious philosophy, it is a minor political party which currently lacks political influence.

The Australian political landscape can be contrasted with countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium where there are more political parties, frequent (and varied) coalitions are negotiated to form government and parties can be divided along secular and non-secular lines. In such environments, having an articulated position (either for or against) euthanasia provides a point of differentiation, so can be a basis upon which voters can choose one party over another. It was this secular–non-secular divide that was influential in euthanasia becoming a political issue in both the Netherlands and Belgium.[72]

Although historically, religiously based parties have had little, if any, political influence in Australia, in the current political climate, minor parties have had a great deal more influence in some jurisdictions than has ever been the case.[73] This fact, combined with the political alliances that have already formed in Australia on this issue, may mean there is an increased likelihood for euthanasia reform to become a political issue in the future. This is certainly consistent with other indicators. For example, ‘euthanasia’ is raised as a political issue on ‘Vote Compass’, an online tool that has been increasingly used and promoted in the lead-up to elections, to assist the voting public to analyse political positions of the parties. Further, position statements on the topic are emerging not only from political parties but also from some peak groups,[74] possibly an indicator that this is an issue upon which it is no longer possible or appropriate not to have a position. These developments, of course, occur against the backdrop of regular and ongoing opinion polls that reveal sustained public support for reform.

Having considered some of the political aspects of the euthanasia debate, including the political affiliations of members introducing the Bills into parliament and some of the voting patterns that have emerged, it is instructive to examine in more detail how far in the parliamentary process the Bills reached, and how they were disposed of. For law reform to occur, it is not enough to have a proponent for change. The relevant parliament must be prepared to allocate time for the Bill to be considered and debated. If a high proportion of Bills remain as notices of motion without being introduced into parliament, for example, that signals less of an appetite for reform than if they all reached the second (or third) reading stage and were debated in full. As evident from the analysis below, the 50 Bills[75] that have been introduced over the past two decades have had varying degrees of progress through and consideration by their respective parliaments. In this section, we identify the stage that all of the Bills reached and how they were disposed of, that is by being passed, withdrawn, discharged or defeated, or by lapsing.

Table 3 provides a summary of the stage that the Bills reached and the disposition of the various Bills, broken up by jurisdiction.

Table 3: Summary of the Stage Reached and Disposition of Australian Voluntary Euthanasia Bills

|

|

Cth

|

ACT

|

NSW

|

NT

|

SA

|

Tas

|

Vic

|

WA

|

Total

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of Bills introduced

|

6

(12%)

|

5

(10%)

|

8

(16%)

|

2

(4%)

|

20

(40%)

|

2

(4%)

|

1

(2%)

|

6

(12%)

|

50

(100%)

|

|

Stage Bill Attained in Parliamentary

Process[76]

|

|||||||||

|

Not introduced

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

4

(8%)

|

|

First reading

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

2

(4%)

|

|

Second reading

|

6

|

4

|

3

|

1

|

15

|

2

|

1

|

6

|

38 (76%)

|

|

Committee stage/ third reading

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

5

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

5 (10%)

|

|

Passed both houses

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

(2%)

|

|

Disposition of Bills

|

|||||||||

|

Discharged

|

1

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

4

(8%)

|

|

Withdrawn

|

0

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

2

(4%)

|

|

Lapsed

|

5

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

14

|

0

|

0

|

5

|

26 (52%)

|

|

Defeated

|

0

|

3

|

3

|

1

|

5

|

2

|

1

|

1

|

16 (32%)

|

|

Passed

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

(2%)

|

As can be seen from Table 3, a high majority of the Bills (88 per cent) reached at least the second reading stage, with only 8 per cent failing to be introduced into parliament. While 88 per cent of Bills reached the second reading stage, only 12 per cent passed that stage. In this section, we consider the various stages reached by the VE Bills against the backdrop of the historical purposes of the various parliamentary phases.

The purpose of the first reading stage is to enable the relevant chamber of parliament to inform itself of the nature and content of the Bill.[77] Parliamentary practice prescribes that the first reading stage is a purely formal procedure and one in which Bills are ordinarily passed without opposition.[78] The Voluntary Euthanasia Referendum Bill 1997 (NSW), introduced by Elisabeth Kirkby on 15 May 1997, is the only VE Bill that was defeated at the first reading stage.

The second reading stage is the most important element of the legislative process. Its purpose is to debate the principle of the Bill, rather than individual clauses.[79] Accordingly, Bills containing technical defects or limitations capable of rectification by reasoned amendment should be permitted to progress to the committee or consideration in detail stages, at which time closer scrutiny can be given to any technical issues. For this reason, some parliamentary speakers have ruled it impermissible for members to discuss a Bill by debating each individual clause. Instead, it has been ruled that the second reading debate should be confined to the objectives and foundation of the legislative proposal.[80]

Despite 88 per cent of Bills (44 Bills) reaching the second reading stage, all but one of those Bills did not progress any further. Having regard to the purpose of the second reading stage, this suggests that it is the efficacy or justifiability of VE at a policy level that is the problem, rather than the perceived inadequacy of the framework or procedural safeguards contained within the relevant legislative proposals. If the majority of politicians supported the principle of VE, but objected to the procedural safeguards or regulatory framework of the proposed legislation, a larger number of Bills would be expected to pass the second reading stage, though possibly fail during the consideration in detail stage.

The consideration in detail stage involves a rigorous and detailed analysis of the specific provisions, procedures, and mechanisms of the legislative proposal.[81] The applicable standing rules and orders often provide for the consideration of each provision of the Bill in order to ensure that all provisions are properly scrutinised and evaluated, and prohibit any amendments which would negative or undermine the purpose of the Bill.[82] This is because the relevant chamber of parliament has already assented to the underlying principle of the Bill during the second reading stage, and any further debate of the objectives of the Bill would be unnecessarily duplicative, constitute a collateral attack on the previous division, and subvert the function of the consideration in detail stage. Only

12 per cent of VE Bills have reached the consideration in detail stage. Accordingly, 88 per cent of VE Bills have not been subject to a detailed

analysis of their specific clauses. Therefore, the common arguments that VE Bills lack adequate procedural safeguards, or that euthanasia cannot be safely regulated, present presumptive conclusions that often have not been adequately tested or examined by the relevant chamber of parliament.

Once introduced into parliament, and regardless of the parliamentary stage reached, there was significant variation in how the Bills were disposed of. More than half (52 per cent) of Bills lapsed, 12 per cent were discharged or withdrawn, and only 32 per cent were defeated.[83] A Bill is defeated when a division is called and a vote taken. Of interest, however, is that many of the Bills were not disposed of in this fashion. In the sections that follow, we consider circumstances in which VE Bills were discharged, withdrawn or, as is most commonly the case, lapsed.

Six of the 50 VE Bills (12 per cent) have been either discharged (4 Bills or

8 per cent) or withdrawn (2 Bills or 4 per cent). Although this is not a large number, it is worth attempting to understand why 12 per cent of VE Bills were terminated in this way rather than by being defeated or lapsing. A Bill is ‘discharged’ when it has been formally presented to parliament and is subsequently removed from the notice paper.[84] A Bill is ‘withdrawn’ when the sponsor of the Bill has recorded a notice of intention to present the legislative proposal in the notice paper and subsequently removes the notification from the notice paper prior to the first reading.[85] In each Australian jurisdiction, it is the sponsor of the Bill who most commonly is responsible for the discharge or withdrawal of the Bill.[86]

A Bill is generally withdrawn or discharged for one of the following reasons: an equivalent Bill is proceeding through another chamber of the parliament; the Bill possesses latent substantive defects which may impede its passage through parliament; the Bill is procedurally or formally noncompliant with an applicable standing rule or order; the Bill has no reasonable prospect for success; or it is considered that keeping the Bill on the notice paper is politically inconvenient.

It is difficult to obtain direct evidence on why a Bill is discharged or withdrawn by its sponsoring member. Possibly the prevailing sociopolitical circumstances and the relatively controversial nature of VE Bills may explain why some VE Bills are terminated in this way. Putting aside one New South Wales Bill,[87] the mean period in which the remaining five VE Bills were discharged or withdrawn was 249 days, or approximately eight months, from an election. In each instance, the election date was reasonably foreseeable at the time of discharge or withdrawal as it was held towards the end of the three- or four-year prescribed legislative term for the relevant jurisdiction. The fact that VE Bills were discharged or withdrawn on average within eight months of a reasonably foreseeable election date may suggest a perception among certain parliamentarians that VE Bills are politically undesirable policies to be associated with during an election campaign.

The dissolution or prorogation of parliament causes all proceedings to conclude and any outstanding Bills on the notice paper to lapse regardless of their stage of progression.[88] As more than half the VE Bills (26 Bills or

52 per cent) are disposed of by lapsing, it is important to explore why this might be the case. The authors suggest that this occurs as a result of two, integrally related, issues: the lack of appetite of the three major political parties to debate the issue; and the relatively limited amount of parliamentary time devoted to private members’ Bills.

A private member’s Bill is one that is advanced by a member of parliament which has not officially been introduced by the government.[89] All Bills introduced by independent politicians or the opposition are private members’ Bills unless formally adopted by the government. Even Bills introduced by ministers of the incumbent government will be private members’ Bills where they are not submitted as part of government business. Under the Australian Westminster parliamentary system, the majority of time in parliament is allocated to considering government business. As explained in the House of Representatives Practice handbook:

The increasing need for Governments to control House time, assisted by the growth of strong party loyalty, led to a steady curtailment of opportunities for private Members to initiate bills and motions, and procedures to expedite the consideration of government business.[90]

Although procedural changes have resulted in more time being allocated to private members’ business, it remains substantially constrained by the political and temporal exigencies of the relevant chamber of parliament.[91] For example, between 1990 and 2014, only 8.3 per cent of time within the Commonwealth House of Representatives was assigned to private members’ business, which includes legislation and motions.[92]

Private members’ motions and petitions are often limited to the private members’ business period in the chamber of parliament which, in some jurisdictions, is not assigned separate time periods from that allocated to committee and delegation business.[93] Furthermore, in many jurisdictions, private members’ motions and petitions are not heard in the order of submission, but in an order determined by a selection committee which prioritises private members’ business.[94] Finally, private members’ Bills are frequently referred to advisory committees for consideration, which further delays the progress of the Bill through parliament.

The reluctance of the three major political parties to engage with the contentious issue of VE was considered in Part III(C). As these political parties are in government in all jurisdictions, the above practices and protocols enable governments to dictate the parliamentary agenda which, as evidenced in Table 3, has resulted in many of the VE Bills lapsing.

The practical impediments that can be encountered by the proponents of reform are illustrated by considering the procedural history of the Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 1996 (SA). The Bill was introduced into the South Australian Legislative Council on 6 November 1996 by a member of the Australian Labor Party, Anne Levy. However, as a result of frequent and protracted adjournments, the division for the second reading was not called until eight months later on 9 July 1997. On the same date, the Bill was moved for consideration by a select committee. Sandra Kanck, leader of the Australian Democrats, questioned the legitimacy of the referral of the Bill to a select committee, stating that:

I am not sure how much a select committee will achieve. We all know that the committee will disappear when the election is called, so I query its usefulness other than as a ploy to stop its becoming a controversial issue at the election. Nevertheless, I will support the committee.[95]

The Bill was referred to the Select Committee on 9 July 1997 and, after convening only twice, the Bill lapsed when Parliament was prorogued before the general election held on 11 October 1997. Despite the lapsing of the Bill, on 25 February 1998, Carolyn Pickles, leader of the Australian Labor Party in opposition, moved for the Social Development Committee to consider the Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 1996 (SA). The Bill was not reintroduced, and the report of the Social Development Committee that was tabled on 20 October 1999 recommended against the reintroduction of the Bill.

In this section of the article, we take the analysis of reform attempts one step further. We seek first to identify those Bills that came ‘close to passing’. If Bills in a jurisdiction are regularly being narrowly defeated after a considered debate in parliament, this may suggest law reform is imminent in that jurisdiction. The opposite will be the case if there is consistently so little support for the Bill in the house that they are generally disposed of without division. Second, we consider whether identifying Bills that were ‘close to passing’ sheds any light on the circumstances or environment in which it is more likely that reform will occur, or at least be seriously debated.

The process of identifying Bills that were ‘close to passing’ was an exacting and time-consuming task. A detailed investigation into each of the 50 Bills[96] was undertaken to determine whether the particular Bill was debated in parliament and, if so, whether a division was called to determine support for the Bill. The criterion to assess whether a Bill was ‘close to passing’ is necessarily subjective in nature, but that chosen by the authors was as follows: the Bill was supported by at least 70 per cent of the number of members required to pass the Bill through the house.[97]

As a result, the following Bills did not satisfy this criterion:

• Bills that were not introduced to parliament;

• Bills that were discharged or withdrawn without being debated;

• Bills that lapsed without being debated; and

• Bills that were debated but were defeated on the voices, or for which no division was called, or where less than 70 per cent of the support needed to pass the Bill was received.

Using this method, only 7 of the 50 Bills that have been proposed were ‘close to passing’. Table 4 below lists these Bills, the proponent and party affiliation (if any), the jurisdiction, how the Bill was disposed of, and the numbers that supported and opposed the Bill.

Table 4: Summary of the Australian Voluntary Euthanasia Bills ‘Close to Passing’

|

Title

|

Name

|

Affiliation

|

Jurisdiction

|

Status

|

Support

|

Oppose

|

|

Rights of the Terminally Ill Bill

1995[98]

|

Marshall Perron

|

Country Liberal

|

NT

|

Passed

|

15

|

10

|

|

Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 1996

|

Anne Levy

|

Australian Labor Party

|

SA

|

Lapsed[99]

|

12

|

8

|

|

Dying in Dignity Bill 2001

|

Sandra Kanck

|

Australian Democrats

|

SA

|

Lapsed[100]

|

10

|

9

|

|

Mark Parnell

|

Australian Greens

|

SA

|

Defeated

|

9

|

11

|

|

|

Dying in Dignity Bill 2002

|

Sandra Kanck

|

Australian Democrats

|

SA

|

Defeated

|

8

|

13

|

|

Bob Such

|

Independent

|

SA

|

Defeated

|

20

|

22

|

|

|

Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2013

|

Larissa Giddings and Nicholas McKim

|

Australian Greens–Australian Labor Party joint Bill

|

Tas

|

Defeated

|

11

|

13

|

Some observations can be made from this analysis. The first is to note that reform of the law governing VE is difficult. Of all the attempts over the past two decades, only one Bill was successful and only six others were ‘close to passing’. These seven Bills represent only 14 per cent of all attempts. This is perhaps a surprising outcome, especially in light of a high level of community support for the enactment of legislation.[101] The second observation is that there is nothing particularly remarkable about those Bills that were closer to passing than the

43 Bills that did not satisfy the criterion. There were no particular features that these Bills possessed which, as a group, distinguished them from the Bills that were not ‘close to passing’.[102] Third, these seven Bills are not all recent, nor does there seem to be a trend for the more recent Bills (those passed between 2010 and 2014) to be ‘closer to passing’. Of the 14 Bills that were introduced over the past five years, only two were in this group of ‘close to passing’.

Fourth, it is interesting to consider the extent to which political factors, including affiliation of the proponent, are influential in the progress of Bills. The proponents of the seven Bills cover the political spectrum with the proponent of the (successful) Northern Territory Bill coming from the Country Liberal Party, two proponents from the Australian Labor Party, two from the Australian Democrats, two from the Australian Greens as well as an independent. However, this distribution is not proportionate to the affiliations of the proponents of the total number of Bills that were introduced. The percentage chance of a Bill being ‘close to passing’ is greater if the Bill is introduced by a member of a major political party, namely the Country Liberal Party or the Australian Labor Party. Of the 16 attempts by independents, only one was in the top seven Bills. Of the 19 attempts by a member of the Australian Greens, only two were in the top seven Bills. Furthermore, of the nine introduced by a member of the Australian Democrats, only two were in the top seven Bills. By contrast, of the six introduced by a member of the Australian Labor Party, two were in the top seven Bills; and the one Bill introduced by a member of the Country Liberal Party in the Northern Territory was successful.

What does not appear to be significant is the political persuasion of the government in power at the time the ‘close to passing’ Bills were debated. At the time the seven ‘close to passing’ Bills were introduced, the Country Liberal Party was in government in the Northern Territory, the Australian Labor Party was in government in Tasmania, and the Liberal Party was in power on two occasions and the Australian Labor Party was in power on three occasions when Bills were introduced in South Australia.

The final, and most remarkable, feature revealed by this analysis is that all of these seven Bills were introduced in the Northern Territory, South Australia and Tasmania, and five of the seven in South Australia. None of the 26 Bills introduced in the other jurisdictions satisfied the ‘close to passing’ criterion. Without further empirical research, it is difficult to know why this is the case. We can speculate that advocacy for controversial reform of this kind is more likely to succeed in smaller jurisdictions where there are fewer politicians who need to be persuaded for the Bill to succeed.[103]

However, there are likely to be a range of other issues at play as well. The high profile of either the proponent or supporter of the Bill has been a feature in each of the Northern Territory, South Australia and Tasmania Bills that have been ‘close to passing’. In the Northern Territory, Marshall Perron was the Chief Minister for much of the time that the reform Bill was being debated, but he was also seen as a passionate and charismatic advocate for change. The 2012 South Australian Bill that was narrowly defeated by two votes, although proposed by independent member Bob Such, was supported by the Premier, Jay Weatherill, as well as two senior ministers, Pat Conlon and Paul Caica.[104] In Tasmania, the proponents of the 2013 reform attempt were the Premier and leader of the Australian Labor Party, Larissa Giddings, as well as the leader of the Australian Greens, Nicholas McKim, both powerful political figures in that state.

Another feature that may be at play here, and identified by Plumb in her research of euthanasia reform activity in South Australia and Tasmania, is the power and influence of interest groups that support reform in those jurisdictions.[105] In South Australia, for example, there has been a long history of an active pro-euthanasia reform group. Plumb notes that the South Australian Voluntary Euthanasia Society (‘SAVES’), founded in 1983, has a large membership base and has consistently campaigned to reform the law.[106] She comments that a key strategy of SAVES is to increase visibility of the topic among politicians and the public, and refers to its monthly presence on the steps of Parliament where it distributes information pamphlets as well as displaying placards. An active pro-euthanasia lobby group, Dying with Dignity Tasmania, was also a feature in the Tasmanian 2013 campaign. In addition to running a public awareness campaign, Plumb notes that a key strategy of the group was to provide ‘good quality’ information to parliamentarians to assist them with their deliberations.[107]

The goal of Part III was to provide detail of reform attempts, the political context in which they occurred, and to make some observations about those reform attempts that came ‘close to passing’. In the next Part, we take a closer look at the Bills themselves.

Building on the above discussion of the general nature of the Bills introduced and whether they came ‘close to passing’, we will now analyse the critical features that have emerged from all the legislative models introduced into Australian parliaments. We will make specific reference to the seven Bills identified as being ‘close to passing’ to determine if there is anything significant in the legislative models adopted which may have impacted upon the ‘success’ of the Bill. Identifying the common elements of the legislative models – especially those that have been close to passing – is important because it may signal valuable information about what model might be close to achieving a consensus position in parliament. This information is useful for generating informed debate about reform in this context.

There are obviously many ways in which these legislative models can be classified and analysed. Some of these are substantive in that the law may permit different categories of behaviour, be it VE, PAS or both. Other modes of classification are structural in the sense that, if it does permit, say VE, PAS or both, there are different ways of doing so. For instance, it may provide that VE, PAS or both remain an offence, but create a defence to such conduct in certain circumstances. Alternatively, it may expressly decriminalise VE, PAS or both in certain specified circumstances. Finally, the legislative regimes can be grouped by examining procedural characteristics, including examining how eligibility is determined, for example in terms of illness and/or suffering criteria. This Part presents the analysis of the Australian legislative attempts in light of these various analytical approaches, but it should be borne in mind that there will be some overlap between them.

Perhaps the most fundamental substantive issue concerns whether the legislative models permit only VE, only PAS, or both. VE models permit the administration of a lethal substance by a physician to the patient. PAS models permit only the prescription of a lethal substance by medical practitioners – which the patient then administers to himself or herself. For some, this distinction is critical.[108]

Only one Australian Bill has been exclusively limited to VE. Subject to proposed safeguards, the Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 2010 (WA) provided that a medical practitioner may ‘administer euthanasia to the applicant by administration of a recognised drug’.[109] Clause 11(6) provided that it is unlawful for any person other than the patient’s medical practitioner to administer VE to the applicant. These provisions suggest that the legislation was limited to VE and was not intended to encompass PAS.[110] The reasons for this, and whether the omission was intentional, do not emerge from the limited debates surrounding the Bill.

The PAS model enables medical practitioners to allow patients, generally through the prescription of lethal substances, to terminate their own lives with, or without, the assistance of family members. The Medical Treatment (Physician Assisted Dying) Bill 2008 (Vic) is the only Australian Bill to permit solely PAS,[111] allowing a treating doctor to provide assistance to an ‘adult sufferer’ to terminate his or her life.[112]

All other Australian Bills allowed both VE and PAS. The ROTTIA is a prime example of this model. It provided that a patient who, in the course of a terminal illness, is experiencing pain, suffering and/or distress to an extent unacceptable to the patient, may request their doctor to assist them in terminating their life.[113] ‘Assist’ was defined to include the prescribing, preparation or giving of a substance to the patient for self-administration, and the administration of a substance to the patient.[114] By employing the phrase ‘the administration of

a substance’, the ROTTIA’s formulation of ‘assist’ exceeds mere PAS

and permits VE. This definition of ‘assist’ was also adopted, for example, in

New South Wales and Tasmanian Bills.[115] Another common approach uses the operative section, not the definitional provisions, to specify what constitutes administering VE.[116] For example, the Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 2002 (WA) expressly provided for the administration of a lethal substance to the patient by the medical practitioner, or the provision of substances for self-administration by the patient.[117]

Some South Australian Bills have widened their conception of VE. For example, the Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 2012 (SA) provided that a medical practitioner may administer VE to an adult suffering unbearable pain in the terminal phase of a terminal illness by (a) administering drugs in appropriate concentrations to end life; (b) prescribing drugs for self-administration by a patient to allow them to end their life; or (c) withdrawing or withholding medical treatment in circumstances which will result in an end to life.[118] The first ground contemplates VE; the second expands VE to incorporate PAS; while the third

ground incorporates the withholding or withdrawing of medical treatment which is legally[119] and, many would argue, conceptually or ethically distinct from VE.[120]

Legislative attempts to legalise VE can also be categorised as permissive, defence and penalty mitigation models. The permissive model provides a legislative framework, integrating appropriate safeguards, thereby positively allowing VE. This has been the most common model (35 Bills). We call it ‘permissive’ because, under such a model, if a medical practitioner complies with the requirements imposed under the framework, no offence is committed. The onus is on the prosecution to prove that the practitioner failed to comply with the provisions, beyond reasonable doubt. The defence model (2 Bills), by contrast, provides criteria which, if satisfied, will constitute an effective defence to a charge of murder or manslaughter. Under this model, VE and/or PAS would remain an offence, to which the defendant would have a defence if he or she can show, on the balance of probabilities, that he or she complied with the requirements of the defence provisions in the relevant Act. The penalty mitigation model substantially reduces associated penalties. These models will now be discussed.

The permissive model normally contains the following six critical elements:

1. power: power is conferred on treating medical practitioners to administer VE to certain eligible patients;[121]

2. immunity: immunity against civil, criminal or disciplinary liability is conferred on any persons assisting in the administration of VE in good faith;[122]

3. safeguards: protective procedures are generally prescribed to require competent requests, to provide information and to obtain psychiatric assessments; these and other safeguards are conditions precedent to exercising the relevant VE power or benefiting from the granted legal and disciplinary immunity (the safeguards are discussed further below);[123]

4. conscientious objections: a conscientious objections clause enables medical practitioners and institutions to decline to administer VE;[124]

5. avoidances: miscellaneous provisions to prevent contingency clauses in contracts, wills, insurance and annuities from adversely affecting the person’s entitlements on the basis of a request for VE;[125] and

6. oversight: various mechanisms are established for systematic oversight of the regime, for example a commission or committee that reviews deaths and/or reporting to parliament about how the legislation is being used.[126]

The ROTTIA once again illustrates the permissive model in use in Australia as it incorporates these six elements.[127]

As the permissive model actively permits the administration of VE or PAS, the safeguards employed require further discussion. The protective mechanisms in these Bills are generally directed towards ensuring the (1) accuracy of diagnosis and prognosis; (2) quality of the patient’s request including information requirements; and (3) voluntariness of the patient’s request. Quality of request refers to whether the patient has capacity and, even if he or she does, the quality of consideration that the patient has given to the decision. Voluntariness, by contrast, refers to whether the patient’s free will has been exercised to make the decision (in order for one’s will to be overborne or unduly influenced, one must at least have had the legal capacity to make the decision in the first place).

First, the most common legislative device applied to ensure the accuracy of the patient’s diagnosis and prognosis is requiring an independent physician to review the patient’s medical records, consult directly with the patient, and provide a second opinion. Variations of this requirement exist within all Australian Bills conforming to the permissive model.[128]

Second, information requirements, specialist consultations and cooling-off periods all ensure the quality of the patient’s decision. All Australian Bills make information requirements a condition of accessing VE or PAS and the medical practitioner’s personal immunity from prosecution or civil suit.[129] Information requirements enable patients to make a meaningful and autonomous decision

by informing them of the nature of their condition, its likely progress,

potential treatment options available, and the availability of supplementary support services.[130] Specialist consultations generally require the intervention of psychiatric or palliative care specialists. The principal function of the psychiatric evaluation is to ensure the patient is not adversely affected by a psychological condition affecting their capacity to make the request to receive VE or PAS. Psychiatric specialists ascertain whether the patient exhibits a treatable depressive or other psychiatric illness which may underpin the request for VE or PAS.[131] The psychiatric evaluation, therefore, operates as both an eligibility criterion and patient safeguard. The primary object of palliative care specialists is to ensure the patient is aware of palliative options to mitigate the physical, psychological and existential pain associated with their terminal illness.[132] The provision of cooling-off periods ensure the patient has the opportunity to understand information supplied by the medical practitioner and reconsider their decision. For example, the ROTTIA specified that the certificate of request could not be completed earlier than seven days from the initial request by the patient for their life to be terminated.[133]

Finally, in addition to issues that go to the capacity and quality of the decision, medical practitioners are also required to be satisfied on ‘reasonable grounds’ that the patient’s decision is voluntary and unaffected by duress or undue influence.[134] This is a separate issue from capacity, though it obviously overlaps with the issues discussed above concerning the quality of the actual decision made. We treat voluntariness separately, however, because it is normally a separately expressed requirement of its own in each of the models – whether the patient’s will has been overborne is in principle a different question from that of whether they have taken enough time to think about the decision or have made an adequately informed decision. Voluntariness is really about whether a decision in the true sense of the term has been taken by the patient at all. The requirement of ‘reasonable grounds’ imposes a positive duty on the practitioner to possess objective evidence that the request was voluntary. Supplementing the requirements of expert evaluation, most statutes regulating PAS and VE require a written request, generally within a prescribed form.[135] Writing requirements evidence both the request and that it originated from the patient rather than a third party.

As stated above, under a defence model, in strict terms, when the defence is made out, this means that the defendant has still committed an offence, but it is an offence for which he or she should not be held criminally responsible. Given this, why adopt such a model? A possible advantage of the defence model is that, by keeping VE or PAS prima facie an offence, the value of human life is considered to be protected, at least symbolically. The model represents the position that, while VE and PAS should not be actively permitted, medical practitioners subject to extraordinary demands, who elect to safely assist patients in terminating their life, should not be penalised. The disadvantage is that anyone who complies with the Act and so has a defence, has still committed an offence (it means that a doctor has effectively committed a murder or manslaughter) – it is just that the law considers it an offence for which the defendant should not

be criminally responsible. This disadvantage might explain why this model has

only been introduced sparingly within Australia – doctors or other medical practitioners probably do not want to consider themselves as committing offences for which the law will not hold them responsible and so this would make the defence model unpopular. When the defence model was introduced the one time in South Australia, it was seen as a legislative compromise designed to generate consensus regarding the legalisation of VE and PAS – that is, the advantage was privileged over the disadvantage. It was introduced as a way of attempting to respond to the failure of 16 permissive model Bills in that state.[136] Clause 3 of the Criminal Law Consolidation (Medical Defences – End of Life Arrangements) Amendment Bill 2011 (SA) would have inserted a defence to a charge of a relevant offence under the Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA). It would have been a defence to such a charge if the defendant could prove, on the balance of probabilities, that he or she acted in good faith in the ordinary course of the defendant’s employment, and that his or her conduct was a reasonable response to the patient’s suffering.[137]

There were other differences between the defence model in the South Australian Bill and the more standard permissive model. In contrast to the permissive models, the Bill merely required the request for VE or PAS to be ‘express’, as opposed to being reduced to writing or communicated within a prescribed form.[138] Furthermore, there was no requirement for expert consultation by psychiatric or palliative care specialists. The principal protective requirements were that the treating practitioner must be a qualified medical practitioner and the administration of VE or PAS must be a ‘reasonable response’ to the patient’s request.[139] Furthermore, unlike the permissive model, oversight and reporting mechanisms were notably absent. The details of whether the practitioner acted in good faith and whether the response in the circumstances was reasonable were to be left to the courts, which meant that parliament could avoid the danger of providing too many procedural requirements to be fulfilled before a practitioner could act on a patient’s request. This was a way of resolving the tension between the need to provide sufficient safeguards on the one hand, and the need to provide workable, practically orientated legislation, on the other.

The defence model adopted in the South Australian Bill contained the following elements:

• substantive defence: a person satisfying the relevant criteria incurs no civil, criminal or disciplinary liability;[140]

• exculpating criteria: these include requiring the relevant person to prove he or she was a treating practitioner;[141] that the person believed the adult to be of sound mind who was suffering from a medical condition which irreversibly rendered the patient’s quality of life intolerable;[142] that the patient expressly requested the VE;[143] and that the conduct was a reasonable response to the patient’s suffering;[144]

• accessorial liability: a defence was proposed, in certain circumstances, for any person who supported or assisted a medical practitioner in relation to the death of a person;[145]

• inchoate liability: the defences apply to circumstances where death was intended or suicide attempted, so it was not necessary to prove the patient in fact died;[146] and

• negativing fault elements: the defence could only be invoked if the conduct occurred in good faith without negligence.[147]

The penalty mitigation model was only introduced after the enactment of the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth) which withdrew the legislative competence of the Australian territories to enact legislation permitting VE or PAS. There have been two such Bills. The relevant loophole the Bills attempted to exploit was that the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997 (Cth) deprived the territories of their power to enact legislation which permits, or has the effect of permitting, VE or PAS. The Bills, by imposing minor fines for committing VE according to prescribed procedural safeguards, arguably did not permit VE or PAS insofar as the practice remained prohibited, because it was still associated with criminal penalties. Clauses 3, 5 and 6 of the Crimes (Assisted Suicide) Bill 1997 (ACT) are examples.[148] The safeguards contained within the penalty mitigation model tend to be significantly less comprehensive than those in the permissive model. The above Australian Capital Territory Bill, for example, prescribed that requests for assistance must be in writing;[149] a cooling-off period of 72 hours;[150] and an independent medical practitioner must confirm that the patient was in a terminal phase of a terminal illness and suffering severe pain or distress.[151] While the imposition of writing requirements, cooling-off periods and limited independent consultation augments patient protection, the penalty mitigation model tends to lack the comprehensive protective frameworks contained within the permissive model.

It is also possible to categorise the models in terms of the nature of the illness that must be suffered by the person seeking assistance to die. Some Bills (which we call ‘exclusive’ models) only operated if the patient suffered from a terminal illness, or even the ‘terminal phase’ of a terminal illness.[152] There were 20 of these exclusive models. Other models (‘inclusive’ models) adopt a broader conception of the illnesses, including, for example, incurable and other chronic illnesses.[153] There were nine of these inclusive models. In one South Australian Bill, a defendant would have been entitled to a defence against criminal liability if the defendant could prove, among other things, that the person whose death resulted ‘from the administration of drugs ... by the defendant’ was suffering from a ‘qualifying illness’.[154] Under that Bill, a ‘qualifying illness’ meant ‘an illness, injury or other medical condition that irreversibly impaired the person’s quality of life so that life had become intolerable to that person’.[155] This provision would have allowed somebody who suffered an accident making them a quadriplegic to end their lives if they found life as a quadriplegic intolerable.

Pain and/or suffering[156] tends to be an essential eligibility criterion within most proposed Australian regulatory frameworks. Although some similarities exist between Bills, significantly different notions of the ‘pain’ and/or ‘suffering’ that must be endured before a person can be assisted to die are adopted. Distinctions lie in different conceptual requirements such as ‘existential suffering’, how pain and/or suffering is ascertained, and the causal connection between the illness and the relevant pain and/or suffering.[157]

There is an important distinction between pain and suffering. A person can ‘suffer’ if they experience pain, but need not experience pain in order to ‘suffer’. ‘Suffering’ is broader than pain and can include mental suffering and emotional suffering. In the case of the Bills introduced in Australia so far, the ‘nature’ of the pain and/or suffering required turns upon the label used to describe the ‘suffering’ and whether the terms appear together, either conjunctively or disjunctively, and on whether only one term is used or more than one is used. Many Bills and statutes refer to ‘pain’, ‘distress’ and ‘suffering’;[158] others to ‘pain’ and ‘distress’;[159] while others refer simply to ‘pain’.[160] The word ‘and’ means that the patient needs to be considered to be experiencing all or both, as the case may be. Likewise, if only one of the terms is used, especially the narrower term ‘pain’, this might (subject to a point we make in the next paragraph) limit the circumstances in which a request can be made. By contrast, where the word ‘or’ is used along with ‘pain’, ‘suffering’, and ‘distress’, the provisions are more expansive.

On the other hand, considering the substantial overlap between the concepts of ‘pain’, ‘distress’ and ‘suffering’, it is unclear to what extent the use of the single term ‘pain’ is distinguishable from the more expansive ones. For example, it is possible that ‘pain’ could be interpreted to encompass physical, mental and emotional suffering. Alternatively, a narrower understanding of the term might restrict it to physical pain. Whether the expanded or narrow definition is adopted would then depend on the relevant statutory framework.[161] If both ‘pain’ and ‘suffering’ are used in the same statute, then it is likely that ‘pain’ would be given the narrower reading – for it is a rule of statutory construction that all terms used in the statute be given a meaning, so the word ‘pain’ would arguably not be interpreted in such a wide way if the words ‘suffering’ (and ‘distress’) are also used. But of course any such restriction would be overcome by the use of the other terms that give it its restricted meaning in the first place.

A Victorian Bill provided that ‘intolerable suffering’ means ‘profound suffering and/or distress, whether physical, psychological or existential,

that is intolerable to the patient’.[162] Contrasting existential with physical and psychological suffering might suggest a different meaning of the term, incorporating, for example, a lack of ‘meaning’ within a person’s life, inability to self-actualise or severe despair. That said, even if this broader definition is adopted, ‘existential suffering’ possesses significant overlap with the concept of psychological suffering and, in practice, the two concepts may frequently be indistinguishable. The broadest concept of ‘suffering’ is contained within the Medical Treatment and Palliative Care (Voluntary Euthanasia) Amendment Bill 2008 (SA). It is defined to include the irreversible impairment of a person’s quality of life.[163] ‘Quality of life’ encompasses all relevant factors which may affect a person’s capacity for pleasure or displeasure.

The regulatory frameworks examined adopted diverse formulations of ‘pain’ and ‘suffering’, which are generally defined according to degree and durability. The degree of ‘pain’ and ‘suffering’ the patient must be experiencing varied between Bills and was defined using inexact phrases such as ‘severe’, ‘considerable’, ‘unbearable’ and ‘intolerable’. For example, the Rights of the Terminally Ill Bill 2001 (NSW) requires that a medical practitioner be satisfied the patient is experiencing ‘severe pain or suffering’ without defining the concept of ‘severe’.[164] The Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 2010 (WA) refers to a patient experiencing pain, suffering or debilitation which is ‘considerable’.[165] Other Bills refer to pain the person finds ‘unbearable’,[166] and so is defined by reference to the individual’s subjective experience.[167] ‘Intolerable suffering’ is another phrase used which, again, is defined subjectively as profound suffering or distress which is intolerable to the patient.[168]

The distinction between ‘considerable’, ‘unbearable’, ‘severe’ and ‘intolerable’ pain and/or suffering is a question of degree. A patient experiencing ‘considerable’ pain may not be in ‘severe’ pain and may not be experiencing ‘unbearable’ or ‘intolerable’ pain. ‘Intolerable’ or ‘unbearable’, by contrast,

seem to be synonymous. The difference in degree only becomes relevant

as a procedural criterion where there is an objective arbiter. The Rights of

the Terminally Ill Bill 2001 (NSW) implicitly suggests that the question

as to whether the patient is suffering ‘severe’ pain will be a matter of

medical judgment.[169] However, contemporary medical practice recognises that the capacity of a person to withstand pain varies between individuals.[170] More commonly, however, Bills such as the Dying with Dignity Bill 2009 (Tas) and Medical Treatment (Physician Assisted Dying) Bill 2008 (Vic) require the patient to make the assessment, stating that the pain must be unacceptable to the patient.[171] When the patient is the arbiter of the pain, the semantic distinction between differing degrees of suffering dissolves. Some Bills, such as the Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 2010 (WA), are silent in relation to the arbiter of the degree of pain the patient suffers.[172]

The ‘durability’ of pain or suffering, or both pain and suffering, must be distinguished from the irreversibility or incurability of the illness. An illness

may be irreversible or incurable, but painless, though presumably one can

‘suffer from’ an irreversible or incurable illness. Here, though, ‘suffer’ just means to have or experience the illness and must be distinguished from the kind

of suffering that accompanies the illness or medical condition, which the use of the word ‘suffering’ is intended to refer to. Durability may be defined as continuous or long-lasting pain or suffering. The requirement of ‘durability’ or repeated requests is also contemplated within statutes with cooling-off periods.[173] Incorporated within the concept of durability is pain mitigation. This question is distinct from curability because it relates to pain palliation or, if the symptoms do not cause pain, suffering palliation. The ROTTIA, for example, imposes a requirement that palliative care must be unable to alleviate pain and/or suffering to levels acceptable to the patient.[174]

The various Bills also differ in terms of the required nexus between suffering and/or pain on the one hand, and illness on the other. Some Bills expressly require an objective causal relationship between the illness and the suffering.[175] For example, under the Medical Treatment (Physician Assisted Dying) Bill 2008 (Vic), the treating doctor must be reasonably satisfied that the sufferer has a terminal or incurable illness that is causing the patient intolerable suffering.[176] Other Bills merely require the existence of a ‘relationship’ between illness and the pain and/or suffering. For example, the Voluntary Euthanasia Bill 2010 (WA) requires the patient to experience pain, suffering or debilitation that is ‘related to the relevant terminal illness’.[177]

The concept of ‘causation’ would clearly encompass pain and/or suffering directly deriving from the illness as a causative factor, but, on a broad interpretation, may also incorporate the existential pain a professional athlete may experience on discovering that, by reason of some debilitating illness or disability, they may never compete again. In contrast, and depending on the conception of causality adopted, it would not encompass a request for VE pursuant to significant existential pain deriving from, say, a partner divorcing the patient after he or she contracts the terminal illness.