University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

CRIMINAL LAW AND THE EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUGS: A NATIONAL STUDY OF THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ‘INTOXICATION’ IN AUSTRALIAN LEGISLATION

JULIA QUILTER[*], LUKE MCNAMARA[**], KATE SEEAR[***] AND ROBIN ROOM[****]

Recent years have seen intense media scrutiny, concerted policy discussion and significant law reform on the relationship between the consumption of alcohol (and other drugs) and the commission of criminal offences. Much of the debate has been dominated by the view that, particularly for crimes of violence, the state of ‘intoxication’[1] produced by the consumption of alcohol and other drugs (‘AOD’) should be regarded as an aggravating factor that adds to the seriousness of the harm done and warrants additional punishment. Some recent legislative reform measures have unambiguously embraced this position.[2] As important as it is, treating intoxication as an aggravating factor is, in fact, only one of the ways in which Australian criminal law attaches significance to AOD consumption.

We are currently undertaking a large-scale study of the ‘knowledges’ and assumptions about the relationship between intoxication and violence (and other offending and anti-social behaviours) that are reflected in Australian criminal laws. Our project compares legislative and judicial knowledges on ‘intoxication’ with scientific and social scientific expert knowledges on the effects of AOD, and the relationship between AOD consumption and violence and other criminal offending. It maps and assesses the multiple ways in which Australian criminal laws attach significance to the attribute of intoxication, and investigates the effects these approaches may have in practice. We aim to facilitate enhanced clarity, consistency and integrity in laws that attach penal significance to the fact of a person’s intoxication, and improve the criminal law’s capacity to meet the needs of the community with respect to the attribution of criminal responsibility for AOD-related anti-social behaviour, harms and risks.

In this article, we report on the first phase of the study: the collection, mapping and analysis of federal, state and territory legislative provisions that attach significance to intoxication in a ‘criminal law’[3] context – whether to justify the exercise of a police power, as a substantive element of an offence, or as an aggravating factor relevant to an element of an offence or sentencing. In addition to cataloguing the different purposes for which significance is attached to intoxication and the sorts of settings and activities in relation to which such laws are operative, we also highlight the claims about AOD consumption and effects, and the moral judgments about AOD use that underpin legislation, and examine how ‘intoxication’ is defined for various criminal law purposes.

As indicated by the title of this article, our study is concerned not only with alcohol intoxication, but also with ‘intoxication’ produced by other drugs. Historically, the concept of intoxication in the criminal law was limited to alcohol and its effects. Preferred legislative terminology included words like ‘drunk’, ‘drunkenness’ and ‘inebriates’. Over time, however, governments have extended the reach of the concept to other ‘impairing’ drugs. For example, as we have previously explained, via an illustrative study of Queensland criminal laws,[4] ‘intoxication’ may be attributable to the consumption of alcohol or a long list

of other proscribed drugs (such as cocaine, heroin, methylamphetamine, and since 2014,[5] steroid drugs such as stanozolol). As a result, the legal concept of ‘intoxication’ is now wider and more complex than when it was limited to the effects of alcohol consumption. An important question, which we consider later in this article, is whether the criminal law’s treatment of intoxication is sufficiently sensitive to the different effects of different drugs.[6]

We have three primary goals in this article. First, we show that Australian criminal laws attach significance to intoxication for a variety of purposes, reflecting different assumptions and judgments about the effects of AOD. Secondly, we show that legislative provisions that attach criminal law/policing significance to intoxication are not limited to traditional criminal harms, but extend to a number of location-based or activity-based ‘sites’ where AOD use is regarded as carrying risks of harm or anti-social behaviour, and thereby, a basis for criminalisation. Finally, we show that, contrary to the reasonable expectation that the criminal law should mark a clear line between sobriety and intoxication if the latter state is to carry penal consequences, there is no single or widely accepted definition of ‘intoxication’, and under-definition and ambiguity are widespread.

This article represents a significant and original contribution to the scholarly literature in two related respects. It represents the first national compilation and analysis of Australian criminal law and procedure legislation that attaches significance to AOD consumption and effects. To this end, and second, it deploys novel conceptual tools – in the form of typologies for classifying and understanding the multiple purposes for which significance is attached to intoxication in Australia, and for identifying and comparing the diversity of definitional approaches – that can be deployed in future analyses of the criminal law–intoxication relationship in Australia and in other countries.

Part II of this article explains the methodology for our study and presents the results. Part III analyses those findings; highlighting insights and implications, offering targeted recommendations for how the identified problems can be addressed, and proposing questions that warrant further research.

The first stage of our research design was to identify all criminal law statutes and regulations in force[7] in Australia (state, territory, Commonwealth) that attach significance to ‘intoxication’ in some way. Following McNamara and Quilter,[8] for the purpose of this study we employed a broad definition of ‘criminal law’ legislation to include any statute or regulation that:

• provides for an offence (or defines/limits a defence);

• provides for a penalty or affects sentencing decisions;

• authorises police or other state agencies to exercise a coercive power; or

• establishes procedures by which criminal offences and associated powers, and rules of evidence are administered.[9]

This definition includes a broad range of legislative provisions, from primary criminal law statutes, both substantive (eg, Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), Summary Offences Act 1966 (Vic)) and procedural (eg, Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld)); to statutes governing police powers (eg, Police Administration Act 1978 (NT)); to statutes which are primarily concerned with regulating a particular activity (eg, Dangerous Goods (Road and Rail Transport) Act 2010 (Tas), Firearms Act 1996 (ACT)) or location (eg, Casino Act 1997 (SA)), and employ criminal laws and associated powers to this end.[10]

Searches were conducted using the web-based open access AustLII database.[11] We searched each jurisdiction in turn, first searching ‘Consolidated Acts’ for the relevant Commonwealth/State/Territory within the AustLII Advanced Search function, and then searching ‘Consolidated Regulations’ for the jurisdiction. In order to be comprehensive, we used a variety of search terms – that is, not simply ‘intoxicated’ or ‘intoxication’ but also other common phrases like ‘under the influence’, ‘impaired’, ‘prescribed concentration’ etc.[12] Search results were filtered to ensure that only criminal law provisions (as defined above) were included and that the provision related to intoxication in some way. For example, there are numerous provisions concerning the supply of liquor/alcohol (eg, under section 51(2) of the Liquor Control Act 1988 (WA), ‘a person who supplies liquor in, or in the vicinity of, an unlicensed restaurant for consumption in that restaurant commits an offence’). However, these were only included in our dataset if they turned on the issue of intoxication (eg, provisions like section 108(4)(a) of the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 (Vic) that make it an offence to supply alcohol to a person who appears to be intoxicated).

We did include provisions that addressed the consumption of alcohol or drugs for two reasons. First, such provisions frequently operate in tandem with provisions on intoxication (eg, provisions that make it an offence to consume or be under the influence in certain locations). Secondly, consumption per se is the subject of a number of discrete provisions. In these cases the rationale is that consumption of AOD carries a risk of intoxication, and pre-emptive discouragement (or interruption) of consumption is an appropriate preventive measure (eg, under regulation 152 of the Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Regulation 2014 (NSW), ‘[a]n inmate must not deliberately consume or inhale any intoxicating substance’).

The second stage of our research design was to catalogue the collected criminal law-intoxication provisions across three dimensions, using the following questions:

1. for what purpose does the provision attach significance to intoxication?;

2. where, and in relation to what sorts of activities (‘sites’), does the provision apply?; and

3. how does the provision define intoxication?

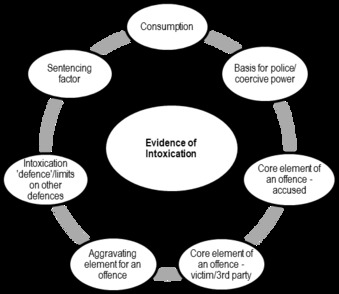

A typology for addressing the first dimension was piloted using New South Wales (‘NSW’) legislation,[13] further tested through an analysis of the raft of intoxication-related changes effected by the Safe Night Out Legislation Amendment Act 2014 (Qld),[14] and refined (see Figure 1). All provisions in the national dataset were then classified according to this typology.

Figure 1: Purposes for which Criminal Law Statutes Attach Significance to Intoxication

The second dimension involved identifying the major ‘sites’ in which criminal law–intoxication provisions operate. For our purposes, ‘site’ is an amalgam of a number of considerations including location, activity and rationale. Four primary sites were identified which were defined at a high level of generality as follows:

1. ‘dangerous activities’ (eg, including driving, boating and the use of firearms);

2. ‘place/setting’ (eg, provisions governing public places/buildings/ transport, licensed premises and correctional/detention facilities);

3. ‘employment/workplace’ (eg, provisions making it an offence to perform certain types of work whilst intoxicated, including police/emergency services/public transport/education/correctional and detention); and

4. ‘criminal harm offences/procedures’ (eg, driving causing harm, sexual offences, drink/food spiking, defences and sentencing).[15]

A fifth category of ‘other’ was utilised to capture provisions unique to one (sometimes more) jurisdictions (eg, legislation governing sobering up centres or provisions concerned with intoxication in the domestic violence context).

Our emphasis in analysing this dimension of the dataset was to identify the major areas of concentration of intoxication-related criminal laws that are common to all or most jurisdictions as well as identifying those sites where one jurisdiction has (or a small number of jurisdictions have) taken a distinctive approach.

Analysis of the third dimension – the definition of ‘intoxication’ – required manual review of all statutory provisions in the dataset (and associated definitions and dictionary sections in the statute/regulation in question) to determine what, if any, approach to defining intoxication had been deployed.

Our search for Australian criminal law statutes and regulations that attach significance to intoxication identified 529 provisions across 115 statutes, 79 regulations and 19 by-laws (a total of 213 instruments) (see Appendix A). Table 1 summarises our findings on the purposes for which significance is attached to intoxication in each instance. It shows that the purpose typology we employed was an effective mechanism for capturing the diversity of approaches. With minor exceptions (ie, none of South Australia, Western Australia and the Commonwealth have enacted sentencing legislation expressly attaching significance to intoxication), all seven purposes were identified in all jurisdictions. NSW (99) and the Northern Territory (82) account for just over one third of all provisions, with a smaller number of provisions in other jurisdictions.

The most common purposes for which Australian criminal laws attach significance to intoxication are to provide the basis for the exercise of a coercive power by the police or another state agency (eg, a correctional centre employee) (39 per cent), and where the fact of a person’s intoxication is a core element of an offence definition (33 per cent). Section 198 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) is an example of the former:

(1) A police officer may give a direction to an intoxicated person who is in a public place to leave the place and not return for a specified period if the police officer believes on reasonable grounds that the person’s behaviour in the place as a result of the intoxication ...

(a) is likely to cause injury to any other person or persons, damage to property or otherwise give rise to a risk to public safety, or

(b) is disorderly.

A simple example of the latter is regulation 134(d) of the Fire Brigades Regulations 1943 (WA): ‘Any employee who ... consumes intoxicants or drugs to excess ... shall be guilty of an offence’. A more complex example of the latter – where intoxication forms only one of the elements of the crime – is section 16(a) of the Summary Offences Act 1966 (Vic): ‘Any person who, while drunk ... behaves in a riotous or disorderly manner in a public place’.

Although, as noted above, the volume of intoxication provisions is uneven across Australian jurisdictions, common to all states and territories is a heavy concentration on provisions that grant coercive powers (mainly to the police) and provisions that define intoxication as a core element of an offence. In Western Australia these categories account for 80 per cent of instances, and the average across all jurisdictions is 65 per cent. The most rarely used approach to attaching significance to intoxication in Australian legislation is to treat it as an aggravating element of an offence (three per cent nationally), and as a sentencing factor (two per cent nationally). This is noteworthy given the recent focus on intoxication as a factor that should increase an offender’s culpability (thus warranting harsher punishment).[18]

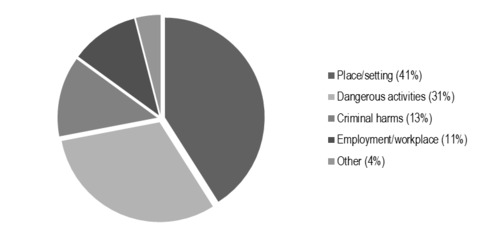

Figure 2: Site Concentrations for Intoxication Provisions in Australian Criminal Law Statutes

Of the four major sites identified in relation to which Australian criminal laws attach significance to intoxication, the distribution of provisions across these sites is illustrated in Figure 2. Forty-one per cent of the 529 criminal law provisions that attach significance to intoxication are concerned with intoxication/consumption in particular locations or settings. The next largest category is the regulation of what we have defined as inherently ‘dangerous’ activities (31 per cent). Eleven per cent of provisions relate to a particular employment/workplace context, while only 13 per cent of provisions relate to ‘classic’ criminal harms (and associated criminal procedures).

Unsurprisingly, the largest number of location-specific provisions related to intoxication in/around licensed premises (26 per cent). Despite the appearance of a trend since the 1970s and 1980s away from the criminalisation of public drunkenness in most jurisdictions,[19] public drinking and intoxication are still

the subject of a large number of criminal law provisions covering public

places generally (22 per cent) – including criminal offences, ‘welfare’-based

detention provisions,[20] move-on powers[21] and alcohol confiscation powers.[22] Other provisions apply specifically to public buildings and venues (18 per cent) and to public transport (16 per cent). Note that for the majority of the licensing and public place provisions the focus is on the mere fact of intoxication (or consumption) as the basis for criminalisation and/or police intervention (eg, section 10(1) of the Summary Offences Act 2005 (Qld) states that ‘[a] person must not be intoxicated in a public place’). The rationale appears to be risk-based and preventative, aiming to preserve public amenity and public safety and, to some extent, offer protection to intoxicated persons themselves.

Half of the dangerous activities provisions relate to driving (including familiar ‘drink driving’ offences), with a significant number of comparable boating offences (21 per cent of this category). Intoxication provisions in relation to explosives/firearms were also prominent (14 per cent). An example of this last category is section 29(1) of the Firearms Act 1977 (SA): ‘A person who handles a firearm while so much under the influence of intoxicating liquor or a drug as to be incapable of exercising effective control of the firearm is guilty of an offence’.

The majority of employment/workplace provisions provide for testing and offences for being intoxicated, applicable to employees in the transport (34 per cent) and police/emergency service (34 per cent) sectors. For example, regulation 10(2) of the State Buildings Protective Security Regulation 2008 (Qld) provides that a ‘security officer must not be under the influence of liquor or a drug to the extent the security officer is not fit to perform the security officer’s functions’.

More than half of the provisions in this category were concerned with limiting the situations in which an accused person can raise a ‘defence’ of intoxication (55 per cent). The next largest sub-category included offences directed at drink ‘spiking’, poisons administration and the administration of AOD to facilitate the commission of an offence (23 per cent). For example, under section 27(3) of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT):

A person who intentionally and unlawfully ... (b) administers to, or causes to be taken by, another person any stupefying or overpowering drug or poison or any other injurious substance likely to endanger human life or cause a person grievous bodily harm ... is guilty of an offence punishable, on conviction, by imprisonment for 10 years.

Driving offences involving the causing of harm accounted for 17 per cent of the provisions in this category. Provisions that treat intoxication as an aggravating or mitigating factor were relatively uncommon (6 per cent).

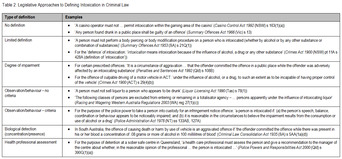

In terms of how intoxication is defined, our analysis identified seven approaches (illustrated in Table 2): (i) no definition; (ii) limited definition; (iii) degree of impairment; (iv) assessment based on observation of behaviour, but with no criteria specified; (v) assessment based on observation of behaviour, with criteria specified; (vi) biological detection (ie, prescribed concentration of alcohol (‘PCA’)/presence of a prohibited drug in breath/blood/urine); and (vii) assessment by a health professional. Note that although the colloquial use of the term ‘intoxication’ relates specifically to alcohol, criminal laws are frequently concerned with AOD. We found significant national variation in how legislatures attempt to capture both alcohol and other drugs. In some states (eg, NSW and Queensland) ‘intoxication’ is often (though not universally) defined broadly so as to include the effects of AOD. In other states (eg, Tasmania) use is made of ‘parallel’ provisions to define, respectively, an impairment offence based on alcohol, and an impairment offence based on other drugs.

The most striking feature of our legislation dataset is that 41 per cent of the criminal law provisions that attach significance to alcohol contain no definition of intoxication or a very limited definition – typically, to simply include the effects of other drugs as well as alcohol. For example, section 428A of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) states: ‘intoxication means intoxication because of the influence of alcohol, a drug or any other substance’. A second notable feature is that although it is ubiquitous in the driving context, biological detection is employed relatively rarely overall (16 per cent of total provisions). Thirdly, where an attempt is made to distinguish sobriety (or ‘acceptable’ levels of alcohol consumption) from AOD consumption of a sufficient magnitude to warrant the intervention of the criminal law, multiple different forms of language are used to this end.

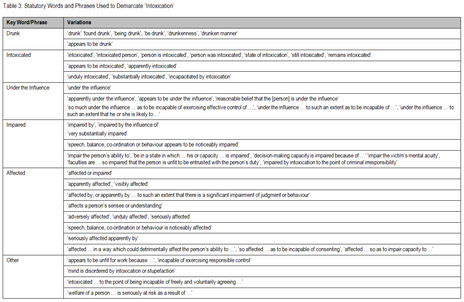

Statutory language often lacks precision and we identified numerous variations and inconsistences – differences for which there was no obvious rationale. We detected not only inter-jurisdictional differences, but differences between statutes in the same jurisdiction (and, in some cases, differences within the same statute).[23] We identified, for example, more than 50 different legislative words and phrases that were designed to demarcate a level of ‘intoxication’ that triggered criminal law legislation in one way or another (see Table 3).

While recognising that particularities of context and purpose will sometimes require variations in statutory language, the rationale for the adoption (or maintenance) of so many different ways of articulating the meaning of intoxication for criminal law purposes is hard to discern. To some extent, the variations may be explained by different drafting language having been preferred in different jurisdictions at different points in time. However, there is no obvious justification for their simultaneous operation today, and it seems very likely that operational inconsistencies will occur.

Most significantly, the multiplicity of phrases in Australian criminal law legislation that are employed in an attempt to draw a line between sobriety (or ‘acceptable’ levels of alcohol consumption) and intoxication are, frequently, poorly adapted to the task. For example, language that purports to describe a level of impairment that warrants the criminal law label ‘intoxicated’ might give the appearance of relative precision, but, on closer inspection, is frequently circular or vague, or both, and unhelpful in defining a legal category of intoxication (as the examples in Table 3 illustrate). For example, what does it mean to say that a victim of sexual assault must be ‘substantially intoxicated’ before her/his intoxication may be relied upon to vitiate consent?[24] How is it possible to determine whether a person’s ‘mind is disordered by intoxication or stupefaction’?[25] Curiously, some provisions appear to set a standard that is higher than appears warranted given the magnitude of risk associated with intoxication in the circumstances of the activity in question (eg, section 29(1) of the Firearms Act 1977 (SA), quoted above, which provides that it is an offence for a person to handle a firearm at a time when the person is ‘so much under the influence of intoxicating liquor or a drug as to be incapable of exercising effective control of the firearm’).[26]

Only a minority of statutory provisions articulate behavioural criteria for assessing intoxication. In such cases, a commonly used (and copied) test provides that a person is intoxicated if:

(a) the person’s speech, balance, coordination or behaviour appears to be noticeably impaired; and

(b) it is reasonable in the circumstances to believe the impairment results from the consumption or use of alcohol or a drug.[27]

Originally developed in the liquor licensing context as the standard

for determining when licensees should stop serving alcohol to patrons,[28] this formulation has been more widely adopted in recent years in legislation governing public order offences and police powers.[29] Even with the benefit of additional guidelines of the sort that are provided by governments to licensees,[30] observation-based assessment of intoxication is a ‘complex interpretive exercise’.[31] Rubenzer has reported that:

there is little evidence that police officers, bartenders, mental health professionals, or alcohol counselors can accurately assess intoxication of strangers at moderate levels of intoxication from informal observations. In addition, the limited evidence available suggests that even extensive experience serving drinkers or assessing drunk drivers does not substantially improve this skill without reliance on sobriety or breath tests. Significant numbers of sober or low BAC subjects were identified as intoxicated in several studies, while substantial numbers of legally intoxicated subjects escaped detection. Despite low levels of accuracy, police officers tend to be quite confident in their judgments, and the evidence is consistent in showing little relationship between confidence and accuracy.[32]

Table 4 crossmatches our typology for classifying and understanding the multiple purposes for which significance is attached to intoxication in Australia with our identification of the seven diverse forms of defining intoxication. We make four observations on this interaction.

First, there is a high correlation between provisions that provide for the exercise of a coercive power by police or other state agency, and the lack of a definition of intoxication (or the inclusion of only a very limited definition) in the legislation. This approach requires the police (or other decision-makers) to exercise discretion in determining whether a person is sufficiently affected by AOD to warrant being subjected to the power provided for by the legislation.

Secondly, where the purpose for which significance is attached is that it is a core element of an offence that the defendant was intoxicated (and to a lesser extent, where third party intoxication is an element), it is surprising – given the centrality of the alleged intoxication to the criminality of the conduct – how many such provisions provide no definition.

Thirdly, and connected to the second point, where the intoxication is an aggravating element of the offence (that is, also central to criminal responsibility, supporting increased culpability) there is considerable variation in the approach to definition. For example, while half of these provisions provide for a biological detection definition, the other half include provisions which variously provide for: no definition; an oblique form of words that purports to articulate a degree of impairment; or assessment based on behaviour, but with no criteria.

Fourthly, where the legislative provision shapes intoxication’s availability for a defence (again, a core dimension of criminal responsibility), the large majority of provisions contain no definition or only a limited definition (82 per cent).

In all of these situations, the challenging task of defining intoxication for criminal law purposes is left to decision-makers in the criminal justice system: police, prosecutors, magistrates/judges and juries. The desirability of this sort of discretion being exercised by individuals with little or no expertise in clinical judgments about AOD effects is considered further below.

Before turning to discuss our primary concerns in this article regarding purposes, sites and definitions, it is worth emphasising the sheer volume of Australian criminal law provisions that attach significance to intoxication. The total number of provisions is large (n = 529) and they are found not only in the major criminal law statutes, but in a broad range of statutes and regulations (more than 200 in total; see Appendix A) governing activities as diverse as entry to swimming pools and the handling of explosives. Although an analysis of the day-to-day operations of these provisions is beyond the scope of this article (including the relative frequency of enforcing particular offences/powers),[34] the volume and range of provisions we have identified suggest that responding to the issue of intoxication in a variety of contexts is a significant and complex national issue.

In a context where recent media and government discourse has focused on arguing for a more punitive approach to alcohol-related violence in the form of offence and sentence aggravation, such provisions account for only a small portion of the total number of criminal law provisions in Australia which attach significance to intoxication. Only 13 provisions (three per cent) treat intoxication as an aggravating element of an offence, and only 11 (two per cent) utilise it as a factor in sentencing.[35] Several jurisdictions, including Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia, do not have offences which involve intoxication as an aggravating factor. Furthermore, Western Australia, South Australia and the Commonwealth do not expressly identify intoxication as a factor relevant to sentencing. These examples show there is a gap between the popular and media-promoted image of how intoxication is related to offending (and should be treated by the criminal justice system), and the legislative reality.[36] Recent debates have tended to assume that the criminal law does not pay sufficient attention to the link between AOD use and violence (and other forms of offending and anti-social behaviour) and that what really matters is that ‘alcohol-fuelled’ offending should receive harsher treatment by the criminal justice system.[37] However, our research shows that the criminal law attends to the AOD/offending link regularly and in a multiplicity of ways.

The fact that 39 per cent of provisions are concerned with authorising

a coercive power – by police or another relevant agency or authority – is

also noteworthy. This is particularly so in light of the recognition that such exercises of power are rarely subject to any form of review or oversight, including because of the on-the-spot environments in which such decisions are made.[38] The available evidence also indicates that such powers are exercised disproportionately against marginalised populations – especially Indigenous communities.[39] We consider this aspect of our findings further below, when we turn to discuss our findings on ‘sites’ where significance is attached to intoxication, and how intoxication is defined.

A comprehensive review of scientific and social-scientific knowledges on AOD effects is beyond the scope of this article, but it is important to recognise that different criminal law provisions are underpinned by different claims about AOD consumption and effects (as well as variation in the extent to which adverse moral judgment is attached to AOD use). For example, provisions in the sexual assault context that equate intoxication with absence of consent[40] foreground a reduction in cognitive and decision-making ability; drink driving offences recognise that AOD impair fine and gross motor skills, reaction time etc; public order offences and associated police powers are said to be justified by the view that AOD use promotes anti-social behaviour and reduces the amenity of others; legislation that treats intoxication as an aggravating factor for crimes of violence[41] is said to be justified by the evidence that AOD use reduces inhibitions, elevates aggression and thus increases the risk of violence, and that, in these circumstances, a person who chooses to become intoxicated deserves adverse moral judgment and additional punishment. This diversity of motivations and objectives is also relevant to the question of how intoxication should be defined for criminal law purposes (which we discuss further below).

Our study revealed that the locations and activities in relation to which criminal laws attach significance to intoxication generally reflect sound appreciation of the areas where questions about intoxication should be relevant (eg, dangerous activities such as driving, boating, use of firearms; locations such as licensed venues). We hesitate to put the heavy regulation of intoxication in public places in this category for a number of reasons. First, when the three-way correlation between public place regulation, police powers and under-definition is recognised (see below) it becomes apparent that this particular emphasis on intoxication-related criminal laws is a significant contributor to the over-policing of Indigenous communities and other vulnerable populations including homeless and mentally ill persons.[42] Secondly, it highlights an over-emphasis on AOD risks and harms that occur in public places that tends to neglect or marginalise the possibility of equivalent AOD-related harms in private settings/places – regardless of whether the drinking that led to intoxication occurred in licensed premises or elsewhere in public or at home. We note some relevant developments below.[43]

‘Public drunkenness’ is a well-known ‘historical’ public order offence which has been abolished in most jurisdictions (but not in Queensland and Victoria).[44] However, despite apparent ‘decriminalisation’,[45] our Phase 1 national review of legislation shows that, across the country, public drinking and intoxication in public are still the subject of a large number of statutory provisions which create criminal offences and provide for police powers (22 per cent of total provisions). Examples of the latter include the power to ‘move on’ intoxicated persons in NSW (Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) section 198) and ‘paperless arrest’ powers in the Northern Territory (Police Administration Act 1978 (NT) section 133AB).

Five features of the nature and operation of public order laws concerned with intoxication are especially noteworthy. First, under-definition of ‘intoxication’ is a distinctive feature of criminal laws in this area. Numerous provisions

contain no definition of ‘intoxicated’ or ‘drunk’, or rely on behavioural criteria, which require discretion and leave decision-makers (eg, and most commonly, police officers) with considerable latitude when determining where the line should be drawn between a person who is, for example, ‘adversely affected’ or ‘unduly intoxicated’, and a person who is not. Even where more detailed criteria are provided for in legislation,[46] police officers are still required to exercise judgment, based on observation alone, as to whether there is a relationship between the observed behaviour and the consumption of alcohol or other drugs.

Secondly, these are the sorts of criminal offences that are enforced,

and powers that are exercised, on a regular basis. More than 40 000 public

order charges are finalised in Australian courts every year.[47] Many of these are intoxication related. For example, in the 12 months from July 2014 to June 2015, 65 per cent of recorded instances of offensive behaviour in NSW were alcohol related.[48] If we add to this number the additional instances in which the mode of criminal justice system engagement is an on-the-spot fine or a move-on direction, the number of people who are affected by the criminal justice system’s treatment of public intoxication grows even further.[49]

Thirdly, the contexts in which these laws are operationalised (including, literally, ‘on the street’) is such that it is rare for courts (or any non-police agency) to be given the opportunity to scrutinise how these laws are being used (including how intoxication is being assessed). As with most public order offences, intoxication-related charges attract high rates of guilty pleas, and the problem of ‘invisibility’ is exacerbated by the growing use of on-the-spot fines or ‘tickets’, laws that provide for move-on without charges, or detention that is allegedly non-punitive.[50] We note that the growth of on-the-spot fines for public order and other minor criminal offences also impacts harshly on the homeless and other financially disadvantaged persons.[51]

Fourthly, the available statistics and the research literature show a long-term pattern of disproportionate impact of intoxication-related public order laws

on Indigenous persons (and also, the homeless and youth).[52] Of course, such enforcement practices are the result of complex factors, but the manner in which relevant legislation is drafted is certainly implicated. Where on-the-spot assessment by non-experts is required (as it frequently is by public order laws), individuals who are already exposed to high levels of policing and surveillance, and in relation to whom there is a long history of alcohol-related stereotypes – including Indigenous persons and homeless persons – may be especially vulnerable to adverse characterisations of behaviour.

Fifthly, if we conceive of ‘criminalisation’ broadly[53] – to include not only criminal offence enforcement and traditional penalties, but also coercive police powers, and ‘administrative’ enforcement methods like on-the-spot fines – it is apparent that reliance on the criminal law and the criminal justice system to address the ‘problem’ of public intoxication is increasing, rather than decreasing, notwithstanding the recognised limitations and known negative effects of such an approach. Especially troubling is the raft of overlapping and harsh police detention and procedural powers that operate in the Northern Territory, many of which are triggered by intoxication in public places. In addition to the series of offences relating to intoxication in various places/settings (public places, transport and buildings),[54] police have extensive and apparently duplicate powers under the Police Administration Act 1978 (NT) to detain intoxicated persons:

• police can apprehend without arrest a person if they have reasonable grounds for believing the person is intoxicated in a public place[55] and because of the person’s intoxication one of the four possible grounds in section 128(1)(c)[56] is satisfied (section 128(1));

• police can, under section 128A, mandatorily refer persons who have been apprehended under section 128 on at least two occasions (within the relevant time periods) for assessment under the Alcohol Mandatory Treatment Act 2013 (NT);

• police can, under section 129(1), detain a person apprehended under section 128 in custody for as long as it ‘reasonably appears to the member of the Police Force in whose custody he is held that the person remains intoxicated’;

• police can demand a breath test of a person in custody who the member reasonably believes is intoxicated with alcohol (section 130A);

• police can, under section 132(2), continue the detention for up to 10 hours of a person taken into custody under section 128 (and who has already been held under section 128 for six hours), if it reasonably appears to the member that the person is still intoxicated with alcohol or a drug;[57]

• police can detain, under division 4AA (known colloquially as

the ‘paperless arrest’ provisions),[58] an intoxicated person, suspected of committing (or about to commit) an infringement notice offence (section 133AB) for a period longer than the four hours permitted generally ‘until the member believes on reasonable grounds that the person is no longer intoxicated’; and

• police can detain a person in lawful custody without charge (and without being required to bring the person before a justice or court as soon as practicable under section 137) ‘for as long as it reasonably appears to the member that the person remains intoxicated’ (section 138A(2)).

A number of these powers are recent additions – including as a result of

the enactment of the Alcohol Mandatory Treatment Act 2013 (NT) and the Police Administration Amendment Act 2014 (NT) – and represent an intensification

of the policing of public intoxication four decades after the ‘decriminalisation’

of public drunkenness in the Northern Territory, in 1974.[59] These provisions represent a significant extension of police powers, with diminished opportunity for independent oversight or scrutiny. A long-term pattern of disproportionate impact on Aboriginal people is thus continued.[60]

Our final comment regarding the public order focus of much of the criminal law we have surveyed is that the tendency to conflate ‘risk of violence’ intoxication with public intoxication tends to reduce the visibility of the role of AOD in ‘private’ violence.[61] We note that some jurisdictions have taken steps towards more explicit and constructive recognition of the relationship between AOD consumption and domestic violence offending. For example, section 35 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW) enables a court to set as an apprehended violence order a prohibition or restriction that the defendant cannot approach the protected person within 12 hours of consuming intoxicating liquor or illicit drugs:

(1) When making an apprehended violence order, a court may impose such prohibitions or restrictions on the behaviour of the defendant as appear necessary or desirable to the court and, in particular, to ensure the safety and protection of the person in need of protection and any children from domestic or personal violence.

(2) Without limiting the generality of subsection (1), an apprehended violence order made by a court may impose any or all of the following prohibitions or restrictions:

...

(c) prohibiting or restricting the defendant from approaching the protected person, or any such premises or place, within 12 hours of consuming intoxicating liquor or illicit drugs, ...

See also section 84(4) of the Domestic and Family Violence Act 2007 (NT), which provides that a ‘person may be detained for a longer time if a police officer is satisfied it is necessary to do so to enable a police officer to properly give a copy of the DVO to the person because of the person’s apparent intoxication’.[62]

The development of appropriate criminal justice responses to domestic violence is a complex issue and largely beyond the scope of our current project, aside from emphasising the traditional ‘blind spot’ to which we have referred here, and noting recent statutory developments that attempt to address the role of intoxication in ‘private’ violence. We recognise that there may be practical enforcement issues with these provisions, and their operation will require close scrutiny.

The Macquarie Dictionary defines the noun ‘intoxication’ as ‘inebriation’ or ‘drunkenness’ or, more expansively, as ‘overpowering action or effect upon the mind’.[63] None of these definitions provide much guidance about how much a person must have consumed, or how incapacitated they must be in order that his/her state qualifies as ‘intoxicated’. In many social settings, and in general conversations, such specificity is relatively unimportant, and we have developed a number of colloquialisms to describe varying degrees of intoxication (eg, from ‘happy’ and ‘tipsy’ to ‘smashed’, ‘legless’ and ‘paralytic’).[64] However, where criminal punishment or the deployment of coercive state powers is a consequence of the label ‘intoxicated’ being applied, it is reasonable to expect that the line of demarcation should be drawn with clarity. Indeed, it might be expected that the proliferation of statutes that attach significance to intoxication might be associated with a trend towards greater specificity as to the meaning of intoxication. To the contrary, our analysis shows that: under-definition is widespread; there is considerable variation both within jurisdictions and nationally as to how intoxication is defined; and the language used to define and describe intoxication is frequently ambiguous, leaving considerable scope for subjective assessments to be made by persons in authority.

A further complication arises from the fact that, as discussed above, the concept of ‘intoxication’ that is operative for a range of criminal law purposes may arise not only from alcohol but also from the long list of other proscribed drugs contained in legislation in all states and territories. Yet, the increased complexity that is produced by this expansive approach has not been matched by definitional sophistication and clarity.[65] For example, there is no attempt to distinguish between the fact that different drugs have different effects – that is, they may be depressants, stimulants or hallucinogens.[66]

One of the inconsistencies revealed by our data is between the measurement of the concentration of alcohol present in a person’s body (where PCA levels denote incremental levels of impairment – eg, low-range, mid-range, high-range) and the approach to ‘other drugs’ where it is often simply the mere presence of a (prohibited) drug (no matter how much was consumed, by what means and when) that is prohibited. The policy argument might be that while alcohol is a legal drug, where the drug is illegal there is no need to set particular limits. However, if the rationale for the provision in question is a concern to manage the risks associated with drug effects (such as diminished capacity to perform a function, or reduced inhibition leading to an increased risk of violence), this argument lacks power. The current approach to drugs other than alcohol means that a person will be considered to be legally intoxicated even where there is no reason to believe that the nature and quantity of the illicit drug in their system was implicated in their alleged criminal offending – eg, MDMA (ecstasy) consumed up to 24 hours previously.[67] The significance that criminal law attaches to AOD consumption should be evidence based, and this would involve greater precision in measuring the quantum of the drug detected, and evidence about the likely effects of that concentration of the drug in question. This is so, whether the criminal law provision is concerned with functional impairment, as in the driving context, or an elevated risk of violence. Although there is evidence of a correlation between alcohol and violence,[68] the case for a link between violence and other drugs is much weaker.[69]

Because the driving context is the most familiar activity where intoxication and criminal law intersect – ‘drink driving’ being part of the vernacular and a high-volume category of criminal offending committed by a broad cross-section of Australia[70] – there may be an expectation that the specificity and objectivity of the biological detection model that is common in that context (particularly blood alcohol concentration (‘BAC’)/prescribed concentration of alcohol (‘PCA’) definitions), will apply more generally. However, our data show that this is not the case. We found that most criminal law provisions that attach significance to intoxication do not turn on biological detection of AOD. Further, the multiplicity of phrases in Australian criminal laws that attempt to draw a line between sobriety (or ‘acceptable’ levels of alcohol consumption) and intoxication – see Table 2 – are in fact poorly adapted to the task. For example, language that purports to describe a level of impairment that warrants the criminal law label ‘intoxicated’ might give the appearance of relative precision, but, on closer inspection, it is frequently circular and unhelpful in defining a legal category of intoxication. Only a minority of statutory provisions articulate meaningful behavioural criteria for making this assessment.

The result is that the vast majority of approaches to the definition of intoxication (apart from biological detection)[71] involve a human assessment that

a particular individual at a particular point in time meets the definition in question (eg, that a person was ‘seriously affected’ by alcohol). Such approaches are inherently subjective and ephemeral, and are rarely susceptible to external scrutiny or review. It is important, therefore, that the basis on which assessments are made is sound. Predicting a person’s level of intoxication based on observed behaviour is well-known to be very difficult – even for trained health professionals.[72] However, there is evidence that well-executed Standardised

Field Sobriety Tests (‘SFSTs’)[73] of the type employed by some law enforcement authorities are a reasonably reliable method for assessing BAC and impairment, and may also be employed in relation to other drugs.[74] At a minimum they offer a framework against which the decision-maker can defend or justify his/her assessment.

As Rubenzer has observed, intoxication assessments based on behavioural observation and human judgment carry a risk of error, including both over- and under- inclusion.[75] The risk of over-inclusion may be borne by the individual whose liberty is deprived as a consequence (eg, by being detained by the police), or who is charged with a crime (such as public drunkenness/intoxication). The risk of under-inclusion may be borne by members of the public or fellow employees whose safety or amenity may be jeopardised by the behaviour of a person who is, in fact, impaired by AOD.

Two categories of statutory provisions characterised by high levels of under-definition deserve specific mention. First, it is striking that intoxication is undefined in 46 per cent of the statutory instances in which intoxication is a core element of a crime. Where an assessment that a person is intoxicated produces penal consequences it is inherently unjust that the legislation that creates the offence in question does not define intoxication or establish how it is to be assessed. Secondly, to emphasise a point made earlier in the discussion of the public order context, 75 per cent of the statutory provisions which provide for the exercise of an intoxication-triggered coercive power (usually by the police) involve under-definition: either no definition, a very limited definition, or a phrase that purports to capture the requisite degree of intoxication or behavioural impairment, though without criteria for assessment. In a further 15 per cent of coercive power instances, the definition adopted is the impaired speech/balance/coordination/behaviour standard, about which, as noted above, there are serious validity and accuracy questions. We conclude that under-definition, in combination with an intense focus on public place intoxication and discretionary police powers, contributes to the over-policing of Indigenous communities and other vulnerable populations including the homeless and mentally ill persons. At a minimum, given that legislation often provides such little guidance as to where the line should be drawn between sobriety (or ‘tolerable’ levels of consumption) and intoxication that deserves to attract opprobrium because it represents a significant threat to public safety or amenity, more attention should be paid to the question of what guidance is given to those exercising these powers as to where to draw that line. How are they trained? What criteria are they provided with? How is the exercise of those powers reviewed and monitored by police agencies?

It might be said that ambiguity and flexibility in the definition of intoxication is more palatable (or even desirable) in this context – compared to other criminal law contexts where the consequences for a person assessed to be intoxicated are more severe, such as where intoxication is a core (or aggravating)[76] element of an offence. However, we should be wary about concluding that vagueness and ambiguity is less objectionable at the ‘lesser’ end of the spectrum of criminal law enforcement, given the frequency with which coercive police powers are employed and public order offences enforced, and the strong evidence of disproportionate impact on already marginalised individuals and communities, including the homeless, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons.[77]

To be clear, we are not suggesting that a single definition of intoxication for all criminal law purposes is realistic or desirable. The multiplicity of purposes for which significance is attached to intoxication in criminal law statutes, the different contexts in which relevant laws operate, and the effects (or assumed effects) of AOD that are foregrounded in different statutes, all militate against such simplicity. For example, in the driving context, where safety is the primary motivation and the evidence on the relationship between intoxication and driving ability is relatively clear, biological detection of a prescribed concentration of alcohol has been widely accepted as a legitimate approach to defining intoxication and attaching penal consequences. In the public order context, the precise concentration of alcohol (or other drugs) in a person’s system is arguably less important than the question of whether their presence is sufficiently disruptive, threatening or otherwise problematic that criminal justice intervention is warranted. On the other hand, it does not necessarily follow that any degree of intoxication should be regarded as a proxy for anti-social or dangerous behaviour.

Cautious consideration should be given to whether biological detection models of defining and assessing intoxication should be expanded beyond the driving (and boating) contexts to which they are largely limited. This could include contexts where the motivation for the criminal law’s attachment of significance to intoxication is to manage the risk of alcohol-related violence, it might be appropriate that legislation reflects the evidence from the experimental literature, which suggests that the likelihood of increased aggression has a threshold of about 0.10 BAC. For instance, since experimental studies show a significant increase in aggressive behaviour above a BAC of about 0.10,[78] it has been suggested that a BAC limit at or near this level be set as the operational definition of intoxication in enforcing prohibitions on selling alcohol to the already intoxicated.[79] Of course, it is important to recognise intoxication does not make everyone more aggressive, and that sociocultural expectancies about

the link between drinking and aggression can also modify behaviour.[80] Further context-specific research and wide consultation with experts and stakeholders would be an important step in any movements towards statutory amendment,

but the research findings presented in this article strongly support the

conclusion that reform is warranted. Certainly, in a broader policy environment where it is widely acknowledged that ‘“[i]ntoxication” is a widely used term

with no consistent or formally agreed definition’,[81] it is time to attend to the inconsistencies, ambiguities and gaps that we have identified on the Australian statute books.

The first major finding of our study of Australian statutes and regulations, which was generally anticipated, is that there is no singular or simple relationship between intoxication and criminal law. Significance is attached to the fact that a person has consumed AOD for a variety of purposes. Fuller examination of the rationales for the different types of significance will be the subject of our further research, including for the purpose of assessing whether current legislative arrangements, and the assumptions which underpin them, are consonant with the available scientific and social scientific evidence on the physical and psychological effects of AOD. Here, we would simply note that our survey has revealed that there is no one characterisation of AOD and their effects in Australian criminal law, and no single rationale for the attachment of significance to intoxication. In some contexts, the capacity for AOD to impair cognitive function is recognised as a factor relevant to rules governing criminal responsibility. In other contexts, the cognitive impairment effects of AOD are ignored in favour of moral judgments about the culpability of persons who allow themselves to become intoxicated to the extent that they pose a greater risk of engaging in violent behaviour than if they abstained from drinking (or drank less) alcohol, or refrained from consuming illicit drugs. In others still, the risks that are considered to be associated with AOD are foregrounded and represent the basis for criminalising intoxication (or, in some cases, consumption).

The second major finding of our study, which is more surprising and troubling, is that there is a widespread problem of under and inadequate definition of what ‘intoxication’ means in the multiple contexts in which it has criminal law significance in Australia – including for police powers, criminal responsibility and criminal punishment. Contrary to the reasonable expectation that, in criminal law contexts where a great deal may turn on the distinction, the identification of a consistent and clear line between sobriety and intoxication should be a high priority, we have found that there is no single or widely-accepted definition of ‘intoxication’ in Australian criminal law. Consistency and clarity are elusive. Many of the legislative formulations used are too vague to be suited to the task of fairly and unambiguously articulating the volume of consumption or degree of impairment (or other effects, such as disinhibition or increased risk of aggression or violence) required to warrant the label ‘intoxicated’ for one of the multiple purposes covered by criminal law statutes.

A majority of the over 500 criminal law provisions we analysed fail to offer meaningful guidance as to the location of the line between sobriety (or ‘acceptable’ levels of alcohol consumption) and intoxication by AOD. The current existence of more than 50 phrases to draw the line may be a result of the accumulation of provisions drafted at different points in Australia’s history, and exacerbated by this country’s federal system of criminal laws, but it hardly inspires confidence that robust decisions are being made about how, when and why it is appropriate to attach criminal law significance to a person’s ‘intoxication’. This is especially the case when so many ‘definitions’ are vague and ambiguous. Serious attention should be given to the national standardisation of legislative terminology.[82] At a minimum, where circumstances demand that assessment based on observed behaviour is more appropriate (or feasible) than the biological detection model, there should be uniform adoption of expressly-stated criteria for making this assessment.

The widespread inclusion of drugs other than alcohol in statutory definitions of intoxication is also problematic, particularly where intoxication is defined as the mere presence of any quantity of a drug in a person’s body, without reference to when the drug was consumed, without reference to impairment or other adverse consequences of consumption, and without recognition that different drugs have different effects. The policy objective of deterring the use of certain drugs via criminalisation[83] needs to be disentangled from the separate question of the capacity of drugs (like cannabis, ‘ice’, cocaine, and ‘ecstasy’) to produce cognitive and/or behavioural effects and risks that are relevant to the administration of criminal justice. Unease about current legal arrangements in relation to ‘drug driving’ have recently brought these issues to the fore,[84] including the need to confront the fact that ‘legal’ prescription drugs (such as diazepam (valium)) can have impairment effects.[85]

Under-definition is clearly problematic when a person’s potential exposure to criminal punishment is at stake. Greater definitional clarity is essential when the nature of the significance attached to intoxication is that it is a core element, an aggravating element of an offence or a factor that may aggravate sentence. It is unsatisfactory that the challenging task of defining intoxication for criminal law purposes, and deploying it in the context of a particular charge, trial or sentencing decision, is left to decision-makers in the criminal justice system – police, prosecutors, magistrates/judges and juries – without access to evidence-based guidance on how to interpret the available evidence of AOD consumption. We do not accept that the definitional deficiencies we have identified are less of a concern where the consequences of a person’s characterisation as ‘intoxicated’ are less punitive – eg, where they are ‘moved on’ by police, detained for their own ‘welfare’, issued with a penalty notice or charged with a minor public order detention. Indeed, given that the ‘street level’ exercise of police powers is, by its nature, both frequent and rarely subjected to independent oversight or scrutiny, it is imperative that the potential for intoxication-related provisions to operate unfairly and/or harshly is confronted.

Police forces across Australia should be urged to explain to the wider community how officers are trained to undertake the difficult task of assessing intoxication, and how officers are trained to exercise their discretion as to which of the myriad powers or offences that are available in many jurisdictions should be utilised in a given instance. It is so rare for courts to be called upon to determine the legitimacy of the use of these powers that other modes of review are essential. If police guidelines are shown to lack specificity, serious consideration should be given to updating legislation that governs intoxication-triggered public order offences and powers, including by the addition of more meaningful indicia for the identification of problematic intoxication.

Finally, having raised a number of concerns about the way in which Australian criminal law statutes and regulations attach significance to intoxication, we would like to draw attention to some positive steps that have been taken towards grappling with the reality that intoxication is not only associated with public behaviour and violence, but is strongly implicated with domestic and family violence that often occurs in private settings. All jurisdictions should consider adopting the provisions currently in force in NSW that allow a court to impose, as a condition of an apprehended domestic violence order, a requirement that the person against whom the order is made, must refrain from AOD consumption for 12 hours prior to communication with the person for whose protection the order is made,[86] and provisions in the Northern Territory and Queensland that authorise the police to hold a person until they have sobered up, if this is considered necessary in order for them to understand the nature, significance and obligation of an apprehended domestic violence order with which they are to be served.[87] Consistent with the major findings of our study, the means by which police and courts assess intoxication should be scrutinised in this context, as in all sites of criminal justice decision-making.

Acts

Children and Young People Act 2008

Corrections Management Act 2007

Criminal Code 2002

Intoxicated People (Care and Protection) Act 1994

Public Bathing Act 1956

Rail Safety National Law (ACT) Act 2014

Road Transport (Alcohol and Drugs) Act 1977

Road Transport (Safety and Traffic Management) Act 1999

Regulations

Health Professionals Regulation 2004[88]

Road Transport (Public Passenger Services) Regulation 2002

Acts

Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Act 1999

Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007

Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999

Intoxicated Persons (Sobering Up Centres Trial) Act 2013

Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002

Rail Safety National Law (NSW)

Regulations

Children (Detention Centres) Regulation 2010[89]

Crimes (Administration of Sentences) Regulation 2014

Education and Care Services National Regulations

Lord Howe Island Regulation 2014

Management of Waters and Waterside Lands Regulations – NSW 1972

Passenger Transport (Drug and Alcohol Testing) Regulation 2010

Passenger Transport Regulation 2007

Rail Safety (Adoption of National Law) Regulation 2012

Sydney Olympic Park Authority Regulation 2012

Zoological Parks Regulation 2014

By-Laws

Crown Lands (General Reserves) By-Law 2006

Racecourses (General) By-Law 1990

Randwick Racecourse By-Law 1981

Acts

Criminal Code Act 1983

Domestic and Family Violence Act 2007

Liquor Act 1978

Police Administration Act 1978

Totalisator Licensing and Regulation Act 2000

Regulations

Correctional Services (Non-Custodial Orders) Regulations 2011

Courtesy Vehicle Regulations 2003

Crown Lands (Recreation Reserve) Regulations 1938

Dangerous Goods Regulations 1985

Marine (Passenger) Regulations 1982

Motor Vehicle (Hire Car) Regulations 1985

Motor Vehicles Regulations 1977

Private Hire Car Regulations 1992

Tourist Vehicles Regulations 1992

Youth Justice Regulations 2006

By-Laws

Charles Darwin University (Site and Traffic) By-Laws 2004

Darwin City Council By-Laws 1994

Darwin Waterfront Corporation By-Laws 2010

Jabiru Town Development (Community Hall) By-Laws 1983

Jabiru Town Development (Swimming Pool Complex) By-Laws 1982

Katherine Town Council By-Laws 1998

Palmerston (Public Places) By-Laws 2001

Port By-Laws 1964[91]

Acts

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities (Justice, Land and Other Matters) Act 1984

Community Services (Aborigines) Act 1984

Community Services (Torres Strait) Act 1984

Criminal Code Act 1899

Domestic and Family Violence Protection Act 2012

Penalties and Sentences Act 1992

Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000

Police Service Administration Act 1990

South Bank Corporation Act 1989

Transport (Rail Safety) Act 2010

Transport Operations (Marine Safety) Act 1994

Transport Operations (Passenger Transport) Act 1994

Transport Operations (Road Use Management) Act 1995

Regulations

Coal Mining Safety and Health Regulation 2001

Corrective Services Regulation 2006

Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health Regulation 2001

State Buildings Protective Security Regulation 2008

Transport Operations (Passenger Transport) Standard 2010

Youth Justice Regulation 2003

Acts

Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935

Harbors and Navigation Act 1993

Security and Investigation Industry Act 1995

Regulations

Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium Regulations 2007

Passenger Transport Regulations 2009

Recreation Grounds Regulations 2011

Acts

Criminal Code Act 1924

Criminal Law (Detention and Interrogation) Act 1995

Dangerous Goods (Road and Rail Transport) Act 2010

Marine Safety (Misuse of Alcohol) Act 2006

Road Safety (Alcohol and Drugs) Act 1970

Security and Investigations Agents Act 2002

Sex Industry Offences Act 2005

Regulations

National Parks and Reserved Land Regulations 2009

Wellington Park Regulations 2009

Acts

Gambling Regulation Act 2003

Liquor Control Reform Act 1998

Marine (Drug, Alcohol and Pollution Control) Act 1988

Rail Safety (Local Operations) Act 2006

Serious Sex Offenders (Detention and Supervision) Act 2009

Regulations

Bus Safety Regulations 2010

Corrections Regulations 2009

Dangerous Goods (Explosives) Regulations 2011

Metropolitan Fire Brigades (General) Regulations 2005

Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulations 2008

Transport (Conduct) Regulations 2005

Transport (Passenger Vehicles) Regulations 2005

Acts

Conservation and Land Management Act 1984

Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913

Health Act 1911

Sentence Administration Act 2003

Western Australian Marine Act 1982

Regulations

Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 1974

Conservation and Land Management Regulations 2002

Dangerous Goods Safety (Storage and Handling of Non-Explosives) Regulations 2007

Education and Care Services National Regulations 2012

Fire Brigades Regulations 1943

Land Administration (Land Management) Regulations 2006

Library Board (Registered Public Libraries) Regulations 1985

Liquor Control (Kunawarritji Restricted Area) Regulations 2011

Mines Safety and Inspection Regulations 1995

Police Force (Member Testing) Regulations 2011

Port Authorities Regulations 2001

Public Transport Authority Regulations 2003

Racing and Wagering Western Australia Regulations 2003

Road Traffic Code 2000

Road Traffic (Authorisation to Drive) Regulations 2014

Road Traffic (Omnibus) Regulations 1975

Western Australian Meat Industry Authority Regulations 1985

By-Laws

Byford Recreation Reserve By-Laws 1937

Djarindjin Aboriginal Community By-Laws 1997

Evaporites (Lake MacLeod) (Cape Cuvier Berth) By-Laws 1991

Government Railways (Sale and Consumption of Liquor) By-Law 1971

Hamersley Iron (Port of Dampier) By-Laws 1971

Iron Ore (Robe River) Cape Lambert Ore and Service Wharves By-Laws 1995

National Trust of Australia (WA) By-Laws 1972

Pemberton National Park and Recreational Reserve By-Laws 1931

Acts

Australian Border Force Act 2015

Australian Federal Police Act 1979

Criminal Code Act 1995

Defence Force Discipline Act 1982

International Criminal Court Act 2002

Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Act 2012

Regulations

Airports (Control of On-Airport Activities) Regulations 1997

Australian National Maritime Museum Regulations 1991

Australian War Memorial Regulations 1983

Civil Aviation Regulations 1988

National Gallery Regulations 1982

National Library Regulations 1994

[*] Associate Professor in the School of Law at the University of Wollongong. The research on which this article reports is funded by the Australian Institute of Criminology’s Criminology Research Grants Program 2014–15. We acknowledge the excellent research assistance provided by Amy Davis.

[**] Professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of New South Wales and Visiting Professor at the University of Wollongong.

[***] Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award Fellow and Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Law at Monash University and Adjunct Fellow in the Social Studies of Addiction Concepts Research Program at the National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University.

[****] Professor and Director of the Centre for Alcohol Policy Research at La Trobe University, and Professor at Stockholm University.

[1] In this article we will generally use the term ‘intoxication’ when referring to the state/effects produced by AOD use with which the criminal law is concerned, though noting that the meaning of the term ‘intoxication’ is by no means self-evident, and legislation uses a multitude of words, phrases and signifiers to describe the state in question (eg, ‘drunk’, ‘under the influence’, ‘impaired’ etc). Indeed, the inherent ambiguity in much of the statutory language used in Australia is one of our chief concerns.

[2] For example, the offence of assault causing death while intoxicated (Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) ss 25A, 25B), introduced in NSW in 2014: see Julia Quilter, ‘One-Punch Laws, Mandatory Minimums and “Alcohol-Fuelled” as an Aggravating Factor: Implications for NSW Criminal Law’ (2014) 3(1) International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 81.

[3] Our understanding of what constitutes ‘criminal law’ legislation is defined below in Part II(A).

[4] Julia Quilter et al, ‘The Definition and Significance of “Intoxication” in Australian Criminal Law: A Case Study of Queensland’s “Safe Night Out” Legislation’ (2016) 16(2) QUT Law Review 42, 47.

[5] See Drugs Misuse Regulation 1987 (Qld) sch 1, as amended by Safe Night Out Legislation Amendment Act 2014 (Qld).

[6] See generally Thomas Babor et al, Lexicon of Alcohol and Drug Terms (World Health Organization, 1994).

[7] As at May 2015.

[8] Luke McNamara and Julia Quilter, ‘Institutional Influences on the Parameters of Criminalisation: Parliamentary Scrutiny of Criminal Law Bills in New South Wales’ (2015) 27 Current Issues in Criminal Justice 21, 25.

[9] On the rationale for a ‘thick’ conception of criminalisation, see Luke McNamara, ‘Criminalisation Research in Australia: Building a Foundation for Normative Theorising and Principled Law Reform’ in Thomas Crofts and Arlie Loughnan (eds), Criminalisation and Criminal Responsibility in Australia (Oxford University Press, 2015) 33.

[10] See Appendix A for a full list of the statutes and regulations surveyed.

[11] It is recognised that there are limitations in using AustLII as it does not contain official legislation; however, we found ultimately by cross-checking against official state-based legislation sites, that AustLII was a more effective search tool for national coverage.

[12] The full list of search terms were: intoxic*; drunk*; under the influence; concentration and alcohol; concentration and blood; prescribed and concentration; permitted and concentration; impair* and alcohol; impair* and liquor; incapacit* and alcohol; incapacit* and liquor; inebriat*; alcohol and consum*; liquor and consum*; stupef*; blood and alcohol; and alcohol limit.

[13] Julia Quilter et al, ‘New National Study Examines Intoxication in Criminal Law’ (2015) 15 LSJ: Law Society of NSW Journal 76.

[14] Quilter et al, ‘The Definition and Significance of “Intoxication” in Australian Criminal Law’, above n 4.

[15] We recognise that these categories are not mutually exclusive and there is overlap between them.

[18] See Quilter, ‘One-Punch Laws, Mandatory Minimums and “Alcohol-Fuelled” as an Aggravating Factor’, above n 2.

[19] See Luke McNamara and Julia Quilter, ‘Public Intoxication in NSW: The Contours of Criminalisation’ [2015] SydLawRw 1; (2015) 37 Sydney Law Review 1, 6, 11–16; Clayton Utz, ‘Review of the Implementation of the Recommendations of the RCIADIC’ (Report, Amnesty International Australia, May 2015) 233 <https://changetherecord.org.au/review-of-the-implementation-of-rciadic-may-2015>.

[20] See, eg, Public Intoxication Act 1984 (SA) s 7.

[21] See, eg, Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) s 198.

[22] See, eg, Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) s 642.

[23] See, eg, the Liquor Act 1992 (Qld), as amended by Safe Night Out Amendment Act 2014 (Qld), which uses both the terms ‘intoxicated’, with a definition of ‘unduly intoxicated’ in s 9A, and ‘drunkenness’ (s 128B(2)), with no definition provided. Section 10(2) of the Summary Offences Act 2005 (Qld), as amended by Safe Night Out Amendment Act 2014 (Qld), provides that ‘intoxicated means drunk or otherwise adversely affected by drugs or another intoxicating substance’ (emphasis in original).

[24] Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 61HA(6)(a) (emphasis added).

[25] Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913 (WA) sch s 28(1) (emphasis added).

[26] (Emphasis added).

[27] Police Administration Act 1978 (NT) s 127A.

[28] See, eg, Liquor Act 1992 (Qld) s 9A; Liquor Control Reform Act 2008 (Vic) s 3AB(1).

[29] See, eg, Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) s 198(5); Police Administration Act 1978 (NT) s 127A.

[30] See, eg, Department of Racing, Gaming and Liquor (WA), ‘Identifying the Signs of Intoxication’ (Guideline, December 2010); Department of Justice (NSW), ‘Intoxication Guidelines’ (Fact Sheet, August 2015).

[31] Amy Pennay, ‘Identifying Intoxication: Challenges and Complexities’ in Elizabeth Manton et al (eds), Stemming the Tide of Alcohol: Liquor Licensing and the Public Interest (Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education, 2014) 109, 113. See also Sarah MacLean, Amy Pennay and Sarah Callinan, ‘The Relationship between Blood Alcohol Content and Harm for Non-drivers: A Systematic Review’ (Report, Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre, June 2012).

[32] Steve Rubenzer, ‘Judging Intoxication’ (2011) 29 Behavioral Sciences and the Law 116, 119.

[34] For example, it is safe to assume that the offence under Libraries Regulations 2013 (SA) reg 7(b) (‘A person must not, while in a library ... behave in a threatening, intoxicated, indecent or otherwise disorderly or offensive manner or create any disturbance’) is less frequently employed than the power to ‘move on’ an intoxicated person (Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW) s 198): see below n 46.

[35] While sentencing legislation appears to be lightly touched by the express concern with intoxication, it is appropriate to acknowledge that such provisions, as have been enacted in some jurisdictions, typically apply generally to any offender being sentenced for a criminal offence. To that extent, in terms of scope and impact, sentencing provisions are not directly comparable to other provisions that attach significance to intoxication that might be more voluminous in the statute books (ie, exercise of power/intoxication as an element of an offence) but which are confined to their specific sphere of operation. In addition, and as we are exploring in further research, sentencing decisions are also influenced by common law principles on the relevance of intoxication evidence: see, eg, Hasan v The Queen [2010] VSCA 352; (2010) 31 VR 28.

[36] See, eg, Lisa Cornish, ‘Scourge of Violence Spreads from Melbourne’s CBD’, Herald Sun (online), 11 January 2014 <http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/law-order/scourge-of-violence-spreads-from-melbournes-cbd/story-fni0fee2-1226799718151> David Meddows, ‘Ice Killers: How the Toxic Drug Affects the Brain to Fuel Rage and Violence’, The Daily Telegraph (online), 7 December 2015 <http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/ice-killers-how-the-toxic-drug-effects-the-brain-to-fuel-rage-and-violence/news-story/f4b941de52807a7a811297f4b3c486f3> see also Julia Quilter, ‘Populism and Criminal Justice Policy: An Australian Case Study of Non-punitive Responses to Alcohol-Related Violence’ (2015) 48 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 24; Asher Flynn, Mark Halsey and Murray Lee, ‘Emblematic Violence and Aetiological Cul-de-Sacs: On the Discourse of “One-Punch” (Non)Fatalities’ (2016) 56 British Journal of Criminology 179; Denise Azar et al, ‘“Something’s Brewing”: The Changing Trends in Alcohol Coverage in Australian Newspapers 2000–2011’ (2014) 49 Alcohol and Alcoholism 336.

[37] Quilter, ‘One-Punch Laws, Mandatory Minimums and “Alcohol-Fuelled” as an Aggravating Factor’, above n 2; Julia Quilter, ‘Assault Causing Death Crimes as a Response to “One Punch” and “Alcohol Fuelled” Violence: A Critical Examination of Australian Laws’ in Thomas Crofts and Arlie Loughnan (eds), Criminalisation and Criminal Responsibility in Australia (Oxford University Press, 2015) 82; Quilter, ‘Populism and Criminal Justice Policy’, above n 36.