University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE HIGH COURT ON CONSTITUTIONAL LAW:

THE 2015 STATISTICS

ANDREW LYNCH[*] AND GEORGE WILLIAMS[**]

This article is the latest instalment in a series, commenced in 2003, that reports the way in which the High Court as an institution and its individual judges decided the matters that came before them in the preceding calendar year.[1] Both the totality of the Court’s decisions and the subset of constitutional cases are examined. These statistical ‘snapshots’ complement substantive analyses of the Court’s decision-making, providing evidence that transcends the mere anecdotal about how the Court functions as an institution by revealing patterns in the formation and decline of coalitions between the Justices, their individual rate of participation in unanimous and joint judgments and also the frequency of dissent.

The results presented in this article have been compiled using the same methodology employed in earlier years.[2] The limitations of an empirical study of the decisions of any final court over the space of a single calendar year are ones we have long acknowledged – particularly so in respect of the constitutional cases which comprise a small portion of the High Court’s caseload. Nevertheless, the fixed parameters of each successive study period enable us to identify emerging trends or developments. We offer a longitudinal reflection on the year’s results by contrasting and comparing them with those from earlier reports.

One important caveat in interpreting the statistics is that it is important to avoid attributing influence to certain individuals simply on the basis of the frequency with which they appear in majority coalitions. The distinctive practice of the current High Court that requires the author of a judgment to ‘join in’ any judge who circulates a concurrence with the judgment means it is extremely difficult to say who is a thought-leader or coalition-builder. In the final courts of the United States and the United Kingdom, just to give two examples, the explicit assignment of an author for the majority or ‘lead’ judgment enables the role of particular individuals in shaping the Court’s reasons to be more reliably gauged.[3] But as Kiefel J has remarked of the High Court’s practice, ‘[a] judge whose judgments are more often than not agreed in by his or her colleagues will not necessarily achieve the recognition or reputation of other judges. This may result in a misconception about influence’.[4] In his remarks at the ceremonial sitting to farewell Hayne J in Canberra on 13 May 2015, French CJ addressed this point when he said that, in Justice Hayne’s 17 years and eight months on the Court, he ‘ha[d] written 412 judgments, 400 of them in Full Court matters ... [m]any of them have been published as judgments in which other members of the Court have joined’.[5] This comment might be seen as a small lifting of the veil on the Court’s practice with respect to joint judgments so as to acknowledge the full extent of the departing Justice’s contribution.

While the difficulty of specific attribution is duly noted, it is still possible to contrast the varying extent to which some members of the Court find themselves either writing with colleagues or apart – as well, of course, as the frequency of their appearance in the majority or in dissent.

Table A: High Court of Australia Matters Tallied for 2015

|

|

Unanimous

|

By Concurrence

|

Majority over Dissent

|

TOTAL

|

|

All Matters Tallied for Period

|

12

(25.00%)

|

27

(56.25%)

|

9

(18.75%)

|

48

(100%)

|

|

All Constitutional Matters Tallied for Period

|

1

(12.50%)

|

4

(50.00%)

|

3

(37.50%)

|

8

(100%)

|

A total of 48 matters were tallied for 2015. Fifty-three cases appear on the AustLII High Court database for the year,[6] but four of these (identified in the Appendix) were excluded as matters decided by a single Justice sitting alone. The fifth exclusion was the native title case of Queensland v Congoo.[7] The six judges who heard the case split 3:3, resulting in the lower court’s decision being affirmed in accordance with the procedural rule that applies when the bench is evenly divided as to whether an appeal before it should be allowed or dismissed.[8] The last occasion on which this rule was applied to a High Court decision was the 2013 case of Monis v The Queen.[9] In explaining the exclusion of that case from the 2013 study, we invoked rule (b) of the methodology applied in compiling these statistics:

(b) A Justice is considered to have dissented when he or she voted to dispose of the case in any manner different from the final orders issued by the Court. This rule will not apply in cases where the final orders are determined by application of a procedural rule (for example, resolution of deadlock between an even number of Justices through use of the Chief Justice’s casting vote). The latter type of case should be discounted from any study attempting to quantify dissent.[10]

The rationale for this approach is that ‘the complete lack of a relational dimension between the Justices themselves’ in the determination of the Court’s final orders ‘argues against tallying as dissents those opinions which are at odds with the result of the case’.[11] None of this is to deny the significance of the opinions delivered in Queensland v Congoo, but for present purposes the case is set aside.

Table A shows that, in 2015, the French Court decided over half the cases through two or more concurring opinions. The Court experienced a simultaneous decline in the rate of unanimous judgments and cases decided over a dissent from the preceding year. The reduction in unanimity was the greater of the two, being from 42.84 per cent of cases in 2014 to a quarter of all matters decided last year. Despite that steep drop, this result is not an especially low one for the Court. For example, in 2012, just 13.11 per cent of cases were decided by a unanimous bench. Previously, the French Court has alternated between high levels of unanimity and explicit disagreement in a two-year cycle. For its first two years, 2009 and 2010, the Court had very high rates of unanimous decisions (half of all cases in 2010) while those featuring a dissent contracted. In the next two-year period, 2011 and 2012, unanimous opinions became much more difficult to achieve due to Justice Heydon’s decision to act on his concerns about judicial independence within the Court by not joining in any opinions with colleagues.[12] At the same time, the frequency with which the Court divided rose (to half of all cases in 2011). After Justice Heydon’s retirement, in 2013 and 2014 we noted an increase once more in the number of unanimous opinions while disagreement as to the resolution of a case fell back to only a quarter of the matters tallied. In 2015, the French Court broke the seemingly hydraulic relationship between unanimity and disagreement that had hitherto been a feature of its decision-making pattern: cases decided in either way fell. Last year, the percentage of cases in which the Justices of the Court were in disagreement as to the result was the same as in 2010 – just 18.75 per cent, the lowest rate not only for the French era but, as we noted on that earlier occasion, the lowest rate of dissent for the Court since we began this series of annual studies.[13]

Of course, trying to understand this development inevitably draws attention to the nature of the Court as a multi-member institution. Australian scholarship has long tended to mark off eras in the High Court’s existence through the handover of the Court’s centre chair. This is a simple, convenient and widely accepted approach to analysis of the Court.[14] Although, in accordance with that tradition, we use the expression ‘French Court’, we readily acknowledge its limitations. One of the justifications for an annual study of this kind is that it breaks down any tendency to see the Court as an essentially stable or ‘monolithic institution’.[15] The year 2015 was one in which the dynamic nature of the institution was especially obvious, given the departure and replacement of two long-serving Justices. For that fact, as well as the inherent variation in the issues confronting the Court, there was no reason why the seventh year of what we refer to as the ‘French Court’ should see the institution maintain the trajectory of the immediately preceding years or revert to some earlier pattern of decision-making. The Court of 2015 is a new body.[16] It is legitimate to compare its performance with preceding years – even earlier eras of the Court’s history, but the point of doing so is to better appreciate the effect of changes in its formal practices, leadership, composition and individual attitudes to decision-making. This is the opposite of suggesting that the Court is, primarily, an abstract singular entity.

In 2015, the Court decided eight constitutional matters out of the 48 tallied – or 16.67 per cent. This is a modest increase from 2014 which recorded the lowest raw number of constitutional cases in any annual study across the life of this project. While the figure is not great, of the eight constitutional cases in 2015, none can be described as ones in which the constitutional issue was insignificant or tangential. For the record, the definitional criteria that determines our classification of matters as ‘constitutional’ remains that which was provided by Stephen Gageler SC, now Justice Gageler of the High Court, when he gave the inaugural annual survey of the High Court’s constitutional decisions in 2002. He viewed ‘constitutional’ matters as:

that subset of cases decided by the High Court in the application of legal principle identified by the Court as being derived from the Australian Constitution (‘Constitution’). That definition is framed deliberately to take in a wider category of cases than those simply involving matters within the constitutional description of ‘a matter arising under this Constitution or involving its interpretation’.[17]

Our only amendment to this statement as a classificatory tool has been to additionally include any matters before the Court involving questions of purely state or territory constitutional law.[18] The year 2015 saw no cases of that kind, but interestingly, half of the constitutional subset comprised cases in which the validity of a state or territory law was challenged as in breach of implications from the Commonwealth Constitution.[19]

Both generally and in respect of the eight constitutional cases, the Court resolved more matters by the delivery of concurring opinions than it did either by unanimous judgment or over a dissenting minority. This is not as common as one might think; as already noted, in recent years, the trend has been either to speak with one voice or fragment into explicit disagreement. In 2015, the Court’s members agreed with each other more often than not, but this did not translate to rates of unanimity as high as in the earlier years of the French Court. But in the context of constitutional cases, as has often been observed by members of the High Court and reflected in these studies, unanimity tends to be much more elusive.[20] By correlation, dissent is not.[21]

The set of constitutional cases comprises seven matters decided by a seven-judge panel and one decided by a panel of six. For the second year in a row, no constitutional case was decided by a five-member bench. The only unanimous constitutional matter tallied was the seven-judge decision in Duncan v New South Wales.[22]

TABLE B(I): All Matters – Breakdown of Matters by Resolution and Number of Opinions Delivered[23]

|

Size of Bench

|

Number of Cases

|

How Resolved

|

Frequency

|

Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered

|

||||||

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

||||

|

7

|

11

(22.92%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (2.08%)

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

7 (14.58%)

|

|

2

|

4

|

|

|

|

1

|

||

|

6:1

|

2 (4.17%)

|

|

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:2

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:3

|

1 (2.08%)

|

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

|

||

|

6

|

5

(10.42%)

|

Unanimous

|

2 (4.17%)

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

3 (6.25%)

|

|

3

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:2

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5

|

30

(62.50%)

|

Unanimous

|

8 (16.67%)

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

16 (33.33%)

|

|

12

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

|

|

||

|

4:1

|

5 (10.42%)

|

|

4

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

3:2

|

1 (2.08%)

|

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

|

||

|

4

|

1

(2.08%)

|

Unanimous

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

1 (2.08%)

|

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

3:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

3

|

1

(2.08%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (2.08%)

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

2:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

TABLE B(II): Constitutional Matters – Breakdown of Matters by Resolution and Number of Opinions Delivered[24]

|

Size of bench

|

Number of cases

|

How Resolved

|

Frequency

|

Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered

|

||||||

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

||||

|

7

|

7

(87.50%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (12.50%)

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

3 (37.50%)

|

|

1

|

1

|

|

|

|

1

|

||

|

6:1

|

2 (25.00%)

|

|

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:2

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:3

|

1 (12.50%)

|

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

|

||

|

6

|

1

(12.50%)

|

Unanimous

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

1 (12.50%)

|

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:2

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Tables B(I) and (II) reveal several things about the High Court’s decision-making over 2015. First, they present a breakdown of, respectively, all matters and then just constitutional matters according to the size of the bench and how frequently it split in the various possible ways open to it. Second, the tables record the number of opinions which were produced by the Court in making these decisions. This is indicated by the column headed ‘Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered’. Immediately under that heading are the figures 1 to 7, which are the number of opinions which it is possible for the Court to deliver. Where that full range is not applicable, shading is used to block off the irrelevant categories. It is important to stress that the figures given in the fields of the ‘Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered’ column refer to the number of cases containing as many individual opinions as indicated in the heading bar.

These tables should be read from left to right. For example, Table B(I) tells us that, of the 30 matters heard by a five-member bench, five were decided 4:1, and in one of those cases three opinions were delivered.

In this way, Table B(I) enables us to identify the most common features of the cases in the period under examination. In 2009, 2010, 2013 and 2014, that was the delivery of a unanimous judgment by a five-member bench. But in 2015, as in the years 2011 and 2012, the most typical case was a 5:0 decision resolved through two concurring opinions, being 12 in number on this occasion.

Table B(II) records the same information in respect of the subset of constitutional cases. All cases were decided by seven judges except for Australian Communications and Media Authority v Today FM (Sydney) Pty Ltd,[25] which was decided by a panel of six. The most common format of a constitutional case in 2015 was a seven-judge decision decided by concurrence. The three matters decided in this way each had a different number of separate opinions – two, three and seven. The constitutional case in which each member of the Court delivered a separate judgment was the challenge brought under section 99 of the Constitution in Queensland Nickel Pty Ltd v Commonwealth.[26]

Queensland Nickel was another entry into that curious genre of ‘welcome cases’ in which a newly appointed Justice delivers the lead judgment and the rest of the bench offers an unqualified, solo concurrence. In Queensland Nickel, the only substantive opinion was written by Nettle J. In Smith v The Queen,[27] it

was Justice Gordon’s turn. Earlier instances of this practice have been noted in these annual studies, going back to the ‘welcome’ of Heydon J in 2003.[28] It is interesting that this custom is maintained by the Court despite it now, with the departure of Hayne J, having completely turned over its membership since that time.

These tables also reveal that there were just two cases in 2015 that meet

the description of a ‘close call’ – that is, a case decided over a minority of more than one Justice.[29] These were CPCF v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection[30] and Commissioner of Taxation v Australian Building Systems Pty Ltd (in liq).[31] The former was a constitutional matter.

It seems worth acknowledging that the inevitable limitations of the empirical study of judicial decision-making are made clear when one considers that McCloy v New South Wales,[32] a constitutional case of great significance in which four distinctive views were offered on fundamental aspects of the implied freedom of political communication, does not stand out in Table B(II). McCloy v New South Wales is a 6:1 decision on the result, although the presence of four separate judgments might at least be seen to indicate that behind that classification lie substantial differences of opinion.

TABLE C: Subject Matter of Constitutional Cases

|

Topic

|

No of

Cases

|

References to Cases

(Italics indicate repetition)

|

|

1

|

11

|

|

|

1

|

1

|

|

|

Chapter III Judicial Power

|

4

|

7, 13, 32, 41

|

|

1

|

12

|

|

|

1

|

13

|

|

|

1

|

41

|

|

|

Implied freedom of political communication

|

1

|

34

|

|

State constitutional law – legislative competence of parliament

|

1

|

13

|

|

State constitutional law – retrospective amendments; relevance of

Kable and Kirk principles

|

1

|

32

|

|

Territory constitutional law – Kable principle

|

1

|

41

|

Table C lists the provisions and principles of the Commonwealth Constitution that arose for consideration in the eight constitutional law matters tallied for 2015. It is assembled primarily through reference to the catchwords accompanying each decision. The table once again shows the prevalence of matters raising issues relating to Chapter III of the Constitution.

TABLE D(I): Actions of Individual Justices: All Matters

|

|

Number of Judgments

|

Participation in Unanimous Judgment

|

Concurrences

|

Dissents

|

|

French CJ

|

45

|

12 (26.67%)

|

33 (73.33%)

|

–

|

|

Hayne J

|

12

|

5 (41.67%)

|

6 (50.00%)

|

1 (8.33%)

|

|

Crennan J

|

1

|

–

|

1 (100.00%)

|

–

|

|

Kiefel J

|

40

|

10 (25.00%)

|

29 (72.50%)

|

1 (2.50%)

|

|

Bell J

|

38

|

10 (26.32%)

|

27 (71.05%)

|

1 (2.63%)

|

|

Gageler J

|

41

|

8 (19.51%)

|

30 (73.17%)

|

3 (7.32%)

|

|

Keane J

|

41

|

9 (21.95%)

|

30 (73.17%)

|

2 (4.88%)

|

|

Nettle J

|

31

|

6 (19.35%)

|

22 (70.97%)

|

3 (9.68%)

|

|

Gordon J

|

15

|

3 (20.00%)

|

11 (73.33%)

|

1 (6.67%)

|

Table D(I) presents, in respect of each Justice, the delivery of unanimous, concurring and dissenting opinions in 2015. Justice Crennan delivered only one judgment before retiring at the commencement of the year and is included merely for the sake of completeness. Her Honour is not otherwise included in the following discussion of decision-making for the year. Justice Hayne delivered just 12 opinions before his own departure from the Court a few months later. The fewer cases that both he and his replacement, Gordon J, heard mean their results are not readily comparable to those of the other Justices. Although Justice Nettle served almost a full year after being sworn in on 3 February, he understandably delivered fewer opinions than his colleagues who were already on the Court and carried cases over from 2014.

It was noted above that the percentage of cases decided with a minority opinion in 2015 was the lowest ever recorded in the 13 annual studies to date (tying with a rate of 18.75 per cent in 2010). This unsurprisingly translates to the individual voting records given in Table D(I). But 2015 did not replicate earlier studies where one judge accounted for a significant portion of the minority opinions delivered. In 2010, Heydon J dissented on six of the total nine occasions the Court divided, and he dissented in all four of the constitutional cases that featured a minority judgment. Other Justices filed minority opinions, but Heydon J was clearly the dominant contributor to the institutional dissent rate. The picture is different in 2015, where no judge dissented more than three times. Accordingly, the institutional figure of nine cases decided with a minority opinion was not predominantly produced by any one member of the Court.

In 2014, the Court’s overall dissent rate of 24.49 per cent owed a lot to Gageler J who, with an individual rate of 18.60 per cent, dissented four times more often than the two judges whose rate of disagreement from the Court’s final orders was the next highest. Justice Gageler was also the most frequent dissenter in 2013, though not as dramatically so. But in 2015, he filed just three dissents as against the nine cases delivered by the Court which featured a minority. What is more, Nettle J filed the same number despite sitting in a quarter fewer cases than Gageler J, thus recording the highest individual rate of dissent in 2015. Justice Keane dissented twice and everyone else except French CJ was in the minority once. For the very first time in this series of annual studies, no member of the Court exceeded a 10 per cent rate of dissenting opinions.

The individual rates of participation in unanimous judgments display a fairly typical variation, reflecting the differently comprised courts that heard the 2015 cases. Of the Justices who sat on the Court for the entire year, French CJ participated in the most unanimous opinions (26.67 per cent of his decisions) and Gageler J participated in the least (19.51 per cent of his decisions). In almost half of his final 12 cases on the Court, Hayne J joined the entire bench to issue a single opinion.

TABLE D(II): Actions of Individual Justices: Constitutional Matters

|

|

Number of Judgments

|

Participation in Unanimous Judgment

|

Concurrences

|

Dissents

|

|

French CJ

|

8

|

1 (12.50%)

|

7 (87.50%)

|

–

|

|

Hayne J

|

5

|

1 (20.00%)

|

3 (60.00%)

|

1 (20.00%)

|

|

Crennan J

|

1

|

–

|

1 (100.00%)

|

–

|

|

Kiefel J

|

8

|

1 (12.50%)

|

6 (75.00%)

|

1 (12.50%)

|

|

Bell J

|

8

|

1 (12.50%)

|

6 (75.00%)

|

1 (12.50%)

|

|

Gageler J

|

8

|

1 (12.50%)

|

6 (75.00%)

|

1 (12.50%)

|

|

Keane J

|

8

|

1 (12.50%)

|

7 (87.50%)

|

–

|

|

Nettle J

|

6

|

1 (16.67%)

|

4 (66.67)

|

1 (16.67%)

|

|

Gordon J

|

3

|

–

|

3 (100.00%)

|

–

|

Table D(II) records the actions of individual Justices in the eight constitutional cases of 2015. Only the Chief Justice, Kiefel, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ sat on all eight matters. As already noted, the constitutional matter decided unanimously was the seven-judge decision in Duncan v New South Wales.[33] The ‘close call’ case of CPCF v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection[34] featured a joint dissent from Hayne and Bell JJ and another from Kiefel J writing alone. Justice Gageler’s dissent in a constitutional case was in North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Ltd v Northern Territory,[35] while that of Nettle J was delivered in McCloy v New South Wales.[36] Chief Justice French, Keane and Gordon JJ did not dissent in a constitutional case.

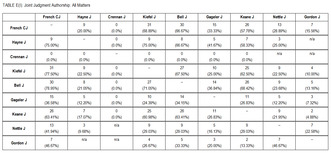

Tables E(I) and E(II) indicate the number of times a Justice jointly authored an opinion with his or her colleagues. It should be remembered that the judges do not hear the same number of cases in a year. For this reason, the tables should be read horizontally, as the percentage results vary depending on the number of cases on which each member of the Court actually sat. That Justices do not necessarily sit with each other on an equal number of occasions should also be noted as a factor that limits opportunities for some pairings to collaborate more often. A straightforward comparison across all members of the Court is obviously inhibited by the comings and goings of 2015. Justice Crennan wrote alone in her sole case for the year. The results for Hayne, Nettle and Gordon JJ are interesting as revealing with whom each wrote most frequently, but of course, the fewer number of cases they decided prevents us from contrasting their rate of participation in joint judgments with that of French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ. Lastly, the gap between how frequently one judge wrote with various colleagues is often not large, maybe just one or two decisions, so the ranking of different judges as co-authors for any particular member of the Court (made explicit in Tables F(I) and (II)) should not be over-emphasised.

Turning to Table E(I) first, French CJ was the most frequent co-author for all members of the bench – including those who served less than the full year. It should be noted that Hayne J joined just as often with Kiefel J, Keane J just as often with Bell J, and Gordon J just as often with Nettle J as each did with French CJ. Justices Kiefel and Bell were Chief Justice French’s most frequent co-authors, joining him in over 70 per cent of the cases both decided for 2015, with Keane J not far behind. Justices Kiefel and Bell were each other’s next most frequent co-author, with Justice Bell’s reasons being expressed with Kiefel J in over 70 per cent of the matters she decided. The percentage was lower for Kiefel J due to her sitting on a higher number of matters. Justice Keane’s rate of joining with Kiefel and Bell JJ was only slightly lower.

At the other end of the spectrum, Justice Gageler’s tendency to go it alone, noted in the earlier 2013 and 2014 results, continued. Among the Justices who served the full year, it was Gageler J with whom the others wrote less – and by a clear margin. Justice Gageler typically joined with his colleagues less than half as often as they joined with each other. Although the continuing judges all wrote with Gageler J more than they did with Nettle or Gordon JJ, who of course arrived only in February and June respectively, both newcomers wrote more often with each other than with Gageler J.

The individual rates of joint judgment for Kiefel, Gageler and Keane JJ in 2015 are consistent with their respective public reflections in the preceding year on the competing advantages and drawbacks of judicial collaboration.[37] Justice Gageler’s advocacy of each judge writing (though not necessarily publishing) separate reasons for his or her decision in a case was considered in our analysis of his lower rate of joining in 2014.[38]

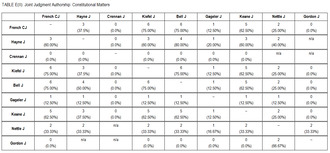

In Table E(II), we see the broader pattern of joint judgment authorship carried over to the subset of constitutional matters – though of course at just eight in number, the opportunities for collaboration are far less frequent. The Chief Justice, Kiefel and Bell JJ were the most frequent co-authors of joint opinions in these cases – not just for each other but for other members of the Court (though Hayne J joined just once more with Bell J than he did French CJ and Kiefel J, and excepting both Crennan J, who joined with no one in her single case, and Gordon J, who wrote twice with Nettle J and no one else in the three constitutional matters she heard). Justice Gageler wrote with others only once, in the unanimous judgment in Duncan v New South Wales.[39] Justice Gageler was the least frequent co-author in a constitutional case for everyone (again excepting only Crennan and Gordon JJ).

While Justice Gageler’s more individualist judicial method is once again confirmed by these results, it is important not to lose perspective on his membership of a court that experienced low levels of explicit disagreement in 2015. Additionally, as we saw in Tables D(I) and (II), Justice Gageler’s dissenting opinions were hardly over-represented in what little explicit disagreement there was on the Court last year. Accordingly, there is a limit to the extent that his tendency to write rather less with others should be seen as indicating an ‘outlier’ status. As we stated in reviewing the 2014 results, Justice Gageler’s discernible individualism on the French Court does not simply suggest he is the successor to the part played by Heydon J and, before him, Kirby J in earlier years.

For the sake of clarity, the rankings of co-authorship revealed by Tables E(I) and (II) are made explicit as the subject of Tables F(I) and (II) below. They translate the percentage figures in Tables E(I) and (II) to give a simple indication of the relative frequency with which each Justice in the left-hand column joined with his or her colleagues – in descending order from ‘1’, signifying the most frequent co-author(s). These tables should also be read horizontally.

TABLE F(I): Joint Judgment Authorship: All Matters: Rankings

|

|

French CJ

|

Hayne J

|

Crennan J

|

Kiefel J

|

Bell J

|

Gageler J

|

Keane J

|

Nettle J

|

Gordon J

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

French CJ

|

–

|

6

|

n/a

|

1

|

2

|

4

|

3

|

5

|

7

|

|

Hayne J

|

1

|

–

|

n/a

|

1

|

2

|

4

|

3

|

5

|

n/a

|

|

Crennan J

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

–

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

|

Kiefel J

|

1

|

5

|

n/a

|

–

|

2

|

4

|

3

|

5

|

6

|

|

Bell J

|

1

|

6

|

n/a

|

2

|

–

|

4

|

3

|

5

|

7

|

|

Gageler J

|

1

|

5

|

n/a

|

4

|

2

|

–

|

3

|

5

|

6

|

|

Keane J

|

1

|

5

|

n/a

|

2

|

1

|

3

|

–

|

4

|

6

|

|

Nettle J

|

1

|

5

|

n/a

|

2

|

2

|

4

|

2

|

–

|

3

|

|

Gordon J

|

1

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

3

|

2

|

4

|

5

|

1

|

n/a

|

TABLE F(II): Joint Judgment Authorship: Constitutional Matters: Rankings

|

|

French CJ

|

Hayne J

|

Crennan J

|

Kiefel J

|

Bell J

|

Gageler J

|

Keane J

|

Nettle J

|

Gordon J

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

French CJ

|

–

|

3

|

n/a

|

1

|

1

|

5

|

2

|

4

|

n/a

|

|

Hayne J

|

2

|

–

|

n/a

|

2

|

1

|

4

|

2

|

3

|

n/a

|

|

Crennan J

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

–

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

|

Kiefel J

|

1

|

3

|

n/a

|

–

|

1

|

5

|

2

|

4

|

n/a

|

|

Bell J

|

1

|

3

|

n/a

|

1

|

–

|

5

|

2

|

4

|

n/a

|

|

Gageler J

|

1

|

1

|

n/a

|

1

|

1

|

–

|

1

|

1

|

n/a

|

|

Keane J

|

1

|

2

|

n/a

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

–

|

2

|

n/a

|

|

Nettle J

|

1

|

1

|

n/a

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

–

|

1

|

|

Gordon J

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

1

|

n/a

|

The year 2015 once again confirmed why the High Court under the leadership of French CJ will be remembered for unusually high degrees of consistency and agreement. Dissent in 2015 occurred in only 18.75 per cent of cases, the equal lowest rate with 2010 (another year of the French Court) of any of these studies. Although 2015 saw less unanimity on the Court, Justices wrote separately not to disagree on the result but to explain their reasoning towards a common conclusion on the Court’s final orders. Indeed, what was striking about last year was that, despite a reduction in unanimity, there was not a single dissent in 39 out of the 48 cases tallied in this study.

Where there was dissent, it tended to be isolated to a single Justice. The year 2015 saw just two instances of a ‘close call’ in which a minority of more than one challenged the result favoured by the majority. These cases were CPCF v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection[40] (Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ dissenting) and Commissioner of Taxation v Australian Building Systems Pty Ltd (in liq)[41] (Keane and Gordon JJ dissenting).

Last year did not see dissent figure prominently in the judgments of any one Justice. Justice Gageler did stand out for his continued demonstration of a more individualistic conception of the judge’s role on a multi-member court, exemplified by the greater frequency with which he wrote separately from others in the majority. Indeed, in 2015, he was far less likely to participate in a joint judgment than any other Justice. Despite this, Gageler J was not a notable dissenter last year (unlike in 2013 and 2014 when he was the Court’s most frequent dissenter, with a rate of 13.95 per cent and 18.60 per cent respectively). In 2015, he dissented in only three cases, as did Nettle J. Other Justices dissented less or not at all. As a result, the rate of dissent was low across the board, with no Justice having a dissent rate above 10 per cent. This is the first time this has occurred since these annual studies began in 2003. We acknowledge, however, that this should not obscure other forms of disagreement on the Court. There were cases, such as McCloy v New South Wales, in which there was a sharp divergence on matters of legal principle, even if these did not produce different resolutions of the matter on its facts.

In 2015, disagreement as to the outcome was, while not frequent, well spread throughout the Court – to a degree that has not really been a feature of these annual studies since they were commenced. Regarding a Court where formal disagreement was as low as it was on the High Court in 2015, some might have concerns about an excessive homogeneity of outlook – or worse, the occurrence of what Heydon J referred to as ‘judicial herd behaviour’[42] or the presence of those whom Starke J called ‘parrots’.[43] But those fears can be allayed by the evident willingness across the Court’s members to dissent from the majority on occasion. Of the nine Justices who served in 2015, seven of them dissented at least once. Not only does this offer a public assurance of each member’s decisional independence, it seems a far preferable situation to having a sole Justice in regular, frustrated minority – what Professor Cass Sunstein called a ‘domesticated dissenter’, denoting such an individual as being routinely without influence among the group.[44]

Concern about the low number of cases in which there was a dissent would also be misplaced. There were only nine matters in which at least one Justice disagreed with the outcome, but there were many others in which members of the Court questioned the legal principles to be applied to reach that result. These differences sometimes revealed a fundamental divide on important questions, thereby suggesting a healthy level of disagreement in spite of what the figures alone might suggest.

The notes identify when and how discretion has been exercised in compiling the statistical tables in this article. As the Harvard Law Review editors once stated in explaining their own methodology, ‘the nature of the errors likely to be committed in constructing the tables should be indicated so that the reader might assess for himself the accuracy and value of the information conveyed’.[45]

• CPCF v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 316 ALR 1; [2015] HCA 1.

• Australian Communications and Media Authority v Today FM (Sydney) Pty Ltd (2015) 255 CLR 352; [2015] HCA 7.

• Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Queensland Rail (2015) 318 ALR 1; [2015] HCA 11.

• Queensland Nickel Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (2015) 255 CLR 252; [2015] HCA 12.

• Duncan v New South Wales (2015) 255 CLR 388; [2015] HCA 13.

• Duncan v Independent Commission Against Corruption (2015) 324 ALR 1; [2015] HCA 32.

• McCloy v New South Wales (2015) 325 ALR 15; [2015] HCA 34.

• North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Ltd v Northern Territory (2015) 326 ALR 16; [2015] HCA 41.

• Queensland v Congoo (2015) 320 ALR 1; [2015] HCA 17 – 3:3 split in which the lower court’s decision is affirmed.

• Plaintiff B15A v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 322 ALR 381; [2015] HCA 24 – Kiefel J sitting alone.

• Vella v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 326 ALR 391; [2015] HCA 42 – Gageler J sitting alone.

• Alqudsi v Commonwealth (2015) 327 ALR 1; [2015] HCA 49 – French CJ sitting alone.

• Certain Lloyd’s Underwriters Subscribing to Contract No IH00AAQS v Cross (2015) 327 ALR 41; [2015] HCA 52 – French CJ sitting alone.

The following cases involved a number of matters but were tallied singly due to the presence of a common factual basis or questions.

• Grant Samuel Corporate Finance Pty Ltd v Fletcher (2015) 254 CLR 477; [2015] HCA 8.

• Duncan v New South Wales (2015) 255 CLR 388; [2015] HCA 13.

• Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v WZAPN (2015) 254 CLR 610; [2015] HCA 22.

• AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2015) 323 ALR 605; [2015] HCA 30.

• Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 326 ALR 476; [2015] HCA 46.

• Commissioner of Taxation v Australian Building Systems Pty Ltd (in liq) (2015) 326 ALR 590; [2015] HCA 48.

• Plaintiff S297/2013 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 255 CLR 231; [2015] HCA 3 – catchwords describe the case as concerning migration and administrative law; questions of constitutional validity were raised but found unnecessary to answer. This matter was not included in the tally of constitutional cases.

• Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Queensland Rail (2015) 318 ALR 1; [2015] HCA 11 – Gageler J answers Questions 1 and 3 posed by the parties in the special case in the affirmative while the joint judgment finds Question 1 unnecessary to answer in light of the answer to Question 2 (with which Gageler J agrees, having accepted in his judgment their interrelationship) and confines its answer to Question 3 to the specific provisions of the Commonwealth and state law giving rise to inconsistency. As there is no difference for the outcome in either approach, Gageler J is tallied as concurring.

• Tomlinson v Ramsey Food Processing Pty Ltd (2015) 323 ALR 1; [2015] HCA 28 – Nettle J is tallied as dissenting because although he agrees the appeal should be allowed and paragraphs 2–5 of the orders made by the New South Wales Court of Appeal should be set aside, he would order, in the place of those orders, that the appeal to the Court of Appeal be dismissed; whereas the joint judgment orders that the matter be remitted to the Court of Appeal for determination of the issue raised by the respondent’s notice of contention.

• McCloy v New South Wales (2015) 325 ALR 15; [2015] HCA 34 – Nettle J concurs in finding division 2A of part 6 of the challenged law valid, but dissents in respect of specific sections contained in division 4A which he finds invalid. His judgment is tallied as dissenting.

• North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Ltd v Northern Territory (2015) 326 ALR 16; [2015] HCA 41 – the judgment of Keane J and the joint judgment of Nettle and Gordon JJ answer Question 1(a) of the special case in a way that is slightly different from the Court’s final orders as determined by the joint judgment of French CJ, Kiefel and Bell JJ. As the difference does not affect their rejection of the plaintiffs’ case, Keane J, and Nettle and Gordon JJ are tallied as concurring.

• Firebird Global Master Fund II Ltd v Nauru (2015) 326 ALR 396; [2015] HCA 43 – Gageler J dismisses the appeal entirely and does not share the view of the remainder of the Court that, otherwise dismissing the appeal, the lower court’s order should be varied on the issue of service and registration of the foreign judgment. Although otherwise concurring, Justice Gageler’s opinion is tallied as dissenting.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2003 Statistics’ [2004] UNSWLawJl 4; (2004) 27 University of New South Wales Law Journal 88.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2004 Statistics’ [2005] UNSWLawJl 3; (2005) 28 University of New South Wales Law Journal 14.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2005 Statistics’ [2006] UNSWLawJl 21; (2006) 29 University of New South Wales Law Journal 182.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2006 Statistics’ [2007] UNSWLawJl 9; (2007) 30 University of New South Wales Law Journal 188.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2007 Statistics’ [2008] UNSWLawJl 9; (2008) 31 University of New South Wales Law Journal 238.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2008 Statistics’ [2009] UNSWLawJl 8; (2009) 32 University of New South Wales Law Journal 181.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2009 Statistics’ [2010] UNSWLawJl 12; (2010) 33 University of New South Wales Law Journal 267.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2010 Statistics’ [2011] UNSWLawJl 42; (2011) 34 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1030.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2011 Statistics’ [2012] UNSWLawJl 33; (2012) 35 University of New South Wales Law Journal 846.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2012 Statistics’ [2013] UNSWLawJl 19; (2013) 36 University of New South Wales Law Journal 514.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2013 Statistics’ [2014] UNSWLawJl 20; (2014) 37 University of New South Wales Law Journal 544.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2014 Statistics’ [2015] UNSWLawJl 38; (2015) 38 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1078.

[*] Professor and Co-director, The Judiciary Project, Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales.

[**] Dean, Anthony Mason Professor and Scientia Professor, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales; Barrister, New South Wales Bar.

[1] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2003 Statistics’ [2004] UNSWLawJl 4; (2004) 27 University of New South Wales Law Journal 88. For a full list of the published annual studies, see the Appendix to this article. An earlier article, by one of the co-authors, examined a larger focus: Andrew Lynch, ‘The Gleeson Court on Constitutional Law: An Empirical Analysis of Its First Five Years’ [2003] UNSWLawJl 2; (2003) 26 University of New South Wales Law Journal 32.

[2] See Andrew Lynch, ‘Dissent: Towards a Methodology for Measuring Judicial Disagreement in the High Court of Australia’ (2002) 24 Sydney Law Review 470, with further discussion in Andrew Lynch, ‘Does the High Court Disagree More Often in Constitutional Cases? A Statistical Study of Judgment Delivery 1981–2003’ (2005) 33 Federal Law Review 485, 488–96.

[3] On the practice of assigning opinion authorship in the United States and the United Kingdom, see respectively Paul J Wahlbeck, ‘Strategy and Constraints on Supreme Court Opinion Assignment’ (2006) 154 University of Pennsylvania Law Review 1729; Alan Paterson, Final Judgment: The Last Law Lords and the Supreme Court (Hart Publishing, 2013) 91–4.

[4] Justice Susan Kiefel, ‘The Individual Judge’ (2014) 88 Australian Law Journal 554, 557.

[5] Transcript of Proceedings, Ceremonial – Farewell to Hayne J – Canberra [2015] HCATrans 105 (13 May 2015) (French CJ).

[6] Australasian Legal Information Institute <http://www.austlii.edu.au/> . For further information about decisions affecting the tallying of 2015 matters, see the Appendix at the conclusion of this article.

[7] [2015] HCA 17; (2015) 320 ALR 1.

[8] Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) s 23(2)(a).

[9] (2013) 249 CLR 92.

[10] Lynch, ‘Dissent’, above n 2, 484.

[11] Ibid 482.

[12] Justice J D Heydon, ‘Threats to Judicial Independence: The Enemy Within’ (2013) 129 Law Quarterly Review 205.

[13] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2010 Statistics’ [2011] UNSWLawJl 42; (2011) 34 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1030, 1032.

[14] This is discussed in Lynch, ‘Does the High Court Disagree More’, above n 2, 492. See, eg, the various entries in this vein in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (Oxford University Press, 2001) and the chapters in Rosalind Dixon and George Williams (eds), The High Court, the Constitution and Australian Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2015). Empirical studies in other jurisdictions may also adopt incumbency of the office of Chief Justice as the means of isolating a particular court: see, eg, Peter McCormick, ‘Blocs, Swarms, and Outliers: Conceptualizing Disagreement on the Modern Supreme Court of Canada’ (2004) 42 Osgoode Hall Law Journal 99.

[15] Sir Anthony Mason, ‘Foreword’ in Haig Patapan, Judging Democracy: The New Politics of the High Court of Australia (Cambridge University Press, 2000) viii–ix.

[16] In fact, on a strict application of the concept of a ‘natural court’, which is employed by empirical studies of judicial decision-making to denote a period in which the same Justices interact with each other (see, eg, A R Blackshield, ‘Quantitative Analysis: The High Court of Australia, 1964–1969’ (1972) 3 Lawasia 1, 11), 2015 featured three natural courts: the bench as constituted before any retirement, the bench after Justice Crennan’s replacement by Nettle J, and the bench after Justice Hayne’s replacement by Gordon J.

[17] Stephen Gageler, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2001 Term’ [2002] UNSWLawJl 8; (2002) 25 University of New South Wales Law Journal 194, 195.

[18] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2007 Statistics’ [2008] UNSWLawJl 9; (2008) 31 University of New South Wales Law Journal 238, 240.

[19] The cases were Duncan v New South Wales (2015) 255 CLR 388; Duncan v Independent Commission Against Corruption [2015] HCA 32; (2015) 324 ALR 1; McCloy v New South Wales [2015] HCA 34; (2015) 325 ALR 15; North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Ltd v Northern Territory [2015] HCA 41; (2015) 326 ALR 16.

[20] See, eg, Kiefel, above n 4, 559.

[21] See, eg, Anthony Mason, ‘Personal Relations: A Personal Reflection’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (Oxford University Press, 2001) 531, 532.

[23] All percentages given in this table are of the total number of matters tallied (48).

[24] All percentages given in this table are of the total number of constitutional matters tallied (8).

[25] [2015] HCA 7; (2015) 255 CLR 352.

[26] [2015] HCA 12; (2015) 255 CLR 252 (‘Queensland Nickel’).

[27] [2015] HCA 27; (2015) 322 ALR 464.

[28] We have earlier explained that cases decided in this way are still tallied as having been decided through concurrences, since the form in which the agreement across the Court is expressed is not joint but separate: Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2013 Statistics’ [2014] UNSWLawJl 20; (2014) 37 University of New South Wales Law Journal 544, 552. For a recent analysis of the practice in respect of the ‘maiden’ speeches of Justices Crennan, Kiefel and Bell, see Kcasey McLoughlin, “A Particular Disappointment?’ Judging Women and the High Court of Australia’ (2015) 23 Feminist Legal Studies 273.

[29] Brice Dickson, ‘Close Calls in the House of Lords’ in James Lee (ed), From House of Lords to Supreme Court: Judges, Jurists and the Process of Judging (Hart Publishing, 2011) 283.

[30] [2015] HCA 1; (2015) 316 ALR 1.

[31] [2015] HCA 48; (2015) 326 ALR 590.

[32] [2015] HCA 34; (2015) 325 ALR 15.

[34] [2015] HCA 1; (2015) 316 ALR 1.

[35] [2015] HCA 41; (2015) 326 ALR 16.

[36] [2015] HCA 34; (2015) 325 ALR 15.

[37] Justice Stephen Gageler, ‘Why Write Judgments?’ [2014] SydLawRw 9; (2014) 36 Sydney Law Review 189; Kiefel, above n 4; Justice P A Keane, ‘The Idea of the Professional Judge: The Challenges of Communication’ (Speech delivered at the Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium, Noosa, 11 October 2014). For discussion, see Andrew Lynch, ‘Keep Your Distance: Independence, Individualism and Decision-Making on Multi-Member Courts’ in Rebecca Ananian-Welsh and Jonathan Crowe (eds), Judicial Independence in Australia: Contemporary Challenges, Future Directions (Federation Press, 2016) 156.

[38] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2014 Statistics’ [2015] UNSWLawJl 38; (2015) 38 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1078, 1090–1.

[40] [2015] HCA 1; (2015) 316 ALR 1.

[41] [2015] HCA 48; (2015) 326 ALR 590.

[42] Heydon, above n 12, 217.

[43] Clem Lloyd, ‘Not Peace but a Sword! – The High Court under J G Latham’ [1987] AdelLawRw 9; (1987) 11 Adelaide Law Review 175, 181.

[44] Cass R Sunstein, Why Societies Need Dissent (Harvard University Press, 2003) 80.

[45] ‘The Supreme Court, 1967 Term’ (1968) 82 Harvard Law Review 63, 301–2.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2016/41.html