University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

1

NATIONAL EXAMS AS A TOOL FOR IMPROVING STANDARDS: CAN AUSTRALIAN FINANCIAL ADVISERS TAKE A LEAF FROM THE PROFESSIONALS’ BOOK?

HUGH BREAKEY[*] AND CHARLES SAMPFORD[**]

Can a national exam contribute to raising service standards in a particular sector – one with quasi-professional elements and aspirations? We explore this question in the specific context of financial advisers and planners in contemporary Australia and the regulation efforts and professionalisation processes occurring therein. Notwithstanding this focus, we inform the discussion by considering wider uses of the exam in other jurisdictions, and also in established professions (including accountancy, law and medicine). For this reason, the article aims to provide food for thought for any occupation-sector – including established professions, quasi-professions and other service-sectors (such as the public service) – which may have cause to consider whether an exam could improve prevailing service standards.[1]

This article’s core message is that a national exam must not be seen as a panacea to a service sector plagued by low standards – nor should it even be set down as an automatic element of a ‘check box list’ of required measures. Rather, a holistic, contextual approach is required. Reliable, high quality service standards result from an interlocking host of elements, including legal, educational, economic, institutional, socio-cultural and psychological factors: these features comprise an ‘integrity system’.[2] In some financial service integrity systems, a national exam might prove costly and redundant. In others, it might engender a perverse effect, eclipsing more effective elements, eliciting misplaced trust from clients, and stymying vital processes of professionalisation. Yet there will be cases where a carefully designed exam helps improve standards. To achieve this end, the exam needs to be strategically targeted to perform its specific role in the integrity system – and the specific role set for the exam helps dictate when the exam is performed, who sets the content, who invigilates its integrity, what it tests, and what hinges upon passing or failing.

The article proceeds as follows: Part II outlines the current situation of financial advisers in Australia – vis-à-vis their existing regulation, performance and quality standards – and noting, in particular, calls for a National Exam. We categorise these calls into three different approaches to the exam: ‘panacea’, ‘check box’ and ‘holistic’. This article aims to substantiate the superiority of the holistic ‘integrity systems’ approach. To this end, Part III outlines some basic considerations with the use of a national exam, highlighting its prima facie merits, but also observing several logistical and integrity-based issues. Part IV moves to comparative considerations, examining the use of national exams for financial advisers in other jurisdictions, comparing the exam with university certification, and then considering the use of the exam (and other standard-setting devices) by established professions. We show that the exam can be employed for different purposes, and that it is rare for the exam to exclusively shoulder the load in ensuring knowledge standards. Part V considers how the exam can be strategically inserted into an existing integrity system, considering the exam’s content and the different roles it can play – as well as surveying its potential risks. By the article’s close, we hope to have shown the complexity of the issue, and the need for considering the integrity system as a whole before deciding what purpose the exam should serve, and how it can be structured to best perform this function.

One definitional note: throughout, when we refer to the ‘National Exam’ or ‘Exam’ (capitalised thus), we refer to the employment of a single exam, or discrete suite of exams, covering the relevant knowledge domains, which must be passed before the subject is legally licensed to deliver the service in the jurisdiction.[3]

The current regulatory scheme governing financial advisers is overseen by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (‘ASIC’). ASIC licenses all businesses that deal in financial products, and its mandated array of obligations include – through Regulatory Guide 146 (‘RG146’) – standards for the training and competence of these businesses’ representatives.[4] RG146 distinguishes between more complex ‘Tier 1’ financial products and simpler ‘Tier 2’ products, which can be sold by less qualified service providers, such as brokers and bank employees.[5] For Tier 1 sales, which will routinely form the subject of financial advisers’ guidance to clients, RG146 requires diploma level training, while giving personalised advice involves additional skills requirements.[6] These education standards are to be assessed by ‘authorised assessors’, including Registered Training Organisations (‘RTOs’) and other accredited providers.[7]

Despite this suite of requirements, myriad reports and commentaries acknowledge that the existing standards are not met, and that the standards themselves are not high enough.[8] Indeed, RG146 itself declares that its educational requirements provide ‘minimum standards’, with professional organisations and others invited to ‘build on’ its basis.[9]

Financial advising is not a profession. However, the sector interrelates with other established professions like law, accounting, estate planners, and auditors, and some commentators are willing to say that the occupation is, at least, ‘in

a process of professionalization’.[10] The occupation currently possesses several quasi-professional elements, and some organisations that compare favourably with established professional organisations.[11]

In general, clients of financial advisers possess many of the multi-layered vulnerabilities facing clients of other professionals,[12] and many of the major scandals concern signature professional issues such as conflicted interests (through secret commissions and employer relationships), and the lack of a fiduciary-like duty and independence on the part of the service provider. From July 2013, legislation stemming from the Future of Financial Advice reforms took aim at these specific concerns, altering the status of commissions and ‘conflicted remuneration’, and setting down (quasi-professional) requirements to act in and to prioritise clients’ interests.[13] Stemming from these professional elements, most reform proposals are littered with the use of methods widely associated with professions, including university requirements, the legal protection of name and function,[14] and – our focus in this article – use of a National Exam.

All that said, financial advising is currently some distance from a genuine profession. While there are variations in how professions should be conceptualised, typical accounts include the notion of a public good (the social benefit that the profession is publicly committed to securing, and that justifies its privileges), a body of knowledge (giving the professionals a unique expertise, unavailable to laypeople) and a code of ethics (shaped by the deliverable public good, guaranteeing standards of competence and fiduciary duties, and bolstered with efforts at self-regulation of those standards). While some of the financial planners’ organisations rise to such standards, these remain voluntary islands of professionalism within a larger regulatory landscape.

Financial services in Australia are widely acknowledged to provide varied – and too often substandard – quality. As well as the frequent front-page scandals and corporate collapses – including Opes Prime, Westpoint Corporation,

Storm Financial and Great Southern, not to mention involvement in the

Global Financial Crisis itself[15] – ASIC’s 2013 ‘shadow-shopping’ report unearthed widespread poor standards.[16] Low education standards have long been highlighted in the popular press,[17] and these concerns extend to the pedagogical quality of courses run by RTOs.[18] While there is some debate over the precise level of complexity involved in financial planning, a rough consensus

holds that providing quality financial advice involves a bachelor degree level of educational sophistication.[19] Yet only a minority of financial advisers hold such qualifications.[20]

While poor standards of behaviour and service no doubt relate to variable standards of competence, expertise and knowledge, they also possess an ethical dimension. In a 2010 study of consumer complaints against financial advisers, failures of integrity ‘dominate the analysis’, ranking ahead of issues of incompetence.[21] Of course, failures in ethics and competence can overlap: the same study concluded that ‘individual competency levels amongst financial advisers are currently too low to allow them to resolve the complex ethical dilemmas they face in their daily practice ...’[22] Even so, the two failures differ: improving competence might do little to solve the problem if an ethical vacuum prevails.

A National Exam squarely confronts the issue of competence, but it might also hope to impact upon ethical compliance. As we will see, it is important to be clear (and realistic) about what the Exam can achieve on each level, both on its own and in combination with other integrity system elements.

Reports and inquiries aiming to raise industry standards have (at time of writing) culminated in recent draft legislation.[23] Many of the recommendations involved the imposition of either formal tertiary education or of a standard National Exam.

The main regulator, ASIC, released two consultation papers, CP153 (in 2011) and CP212 (in 2013), both considering the use of an Exam, and the increase of formal educational requirements. In CP212, ASIC went on to suggest that the Exam’s implementation may obviate the need for formal educational requirements:

It is important to note that if a national examination is implemented, it may replace any obligation to do a training course approved in writing for advisers of Tier 1 products. That is, Tier 1 advisers would be required to pass the national examination but what they do to equip themselves to pass the examination may be up to them.[24]

Other recommendations differ: the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services’ (‘PJCCFS’) 2014 inquiry found a role for a National Exam set by a professional body. On the PJCCFS’ approach, the Exam would be sat by the aspiring financial adviser only after completing their formal degree and after a year of supervised work.[25] The Financial Planning Association of Australia’s (‘FPA’) submission to the PJCCFS recommended reforming formal education systems (as well as other factors) that would make a National Exam redundant.[26] The Financial System Inquiry: Final Report of 2014 followed a similar line of thought in requiring a bachelor degree equivalent for financial advisers, and eschewing a National Exam.[27]

In December 2015, the Treasury Department released draft legislation: Corporations Amendment (Professional Standards of Financial Advisers) Bill 2015 (Cth) (‘Bill’). The Bill contains an array of significant changes to the overall regulatory landscape, many with quasi-professional elements.[28] These include the protection of title and function and the mandated creation of a non-profit ‘Standards Body’.[29] The Standards Body is tasked with developing a code of ethics (going beyond purely legal requirements), with various ASIC-approved schemes to oversee compliance of the code.[30]

The draft Bill imposes four competency-based standards on financial advisers giving personal advice on complex financial products. Licensed advisers

must: possess a bachelor degree or equivalent, pass an Exam approved by the Standards Body, undertake a professional year, and meet the requirements for continuous professional development (‘CPD’).[31] The Exam will be approved by the Standards Body, who will also arrange its administration.[32]

When it comes to the proposed use of the National Exam as a reform initiative, the above proposals illustrate three different approaches.

This first approach places the Exam as the fundamental bulwark in the battle against low service standards. Other supplementary options may be employed, but the Exam serves as the central competency-based gateway to service entry. Other measures either have only minimal or indirect educational effects, or occur with little oversight. The panacea approach boasts an admirable simplicity; if the sector suffers from a problem of low standards of competence, then the Exam can be presented as a direct, visible response: a ‘silver bullet’ solution to a discrete problem. ASIC in CP212 approached this position when it allowed that the Exam’s effective implementation could obviate the requirement for university education.

The second approach accepts that the Exam alone cannot ensure the sector’s competence and service standards. Instead, the checklist (or ‘building blocks’) approach puts forward a laundry list of appropriate governance measures that,

in combination, aim to establish appropriate standards of quality service.[33] Requiring formal qualifications, imposing an independent Exam, keeping a register, and mandating licenses for practicing companies present a multi-layered system capable of preventing incompetent and uneducated persons from providing financial advice. The checklist approach recognises that multiple institutions and processes can fulfil different functions, and can act as a check on the others. This approach can seem commonsense. Every human system suffers from errors, misapplications or corruption on at least some scale, thus allowing problems to slip through its cracks. Providing multiple layers introduces backups and fail-safe mechanisms into the system.

If we set aside the single paragraph noted above in ASIC’s CP212, then this checklist approach would map onto ASIC’s proposed regime. In its argument for the Exam, ASIC gestures towards other jurisdictions that similarly employ a National Exam for financial advisers. By including one in the Australian regulatory landscape, we could tick the boxes for formal educational qualifications, a National Exam, a system of registration and a requirement for company licences.

The integrity systems perspective offers a different approach.[34] Like the checklist approach, it acknowledges the need for multiple, independent layers of protection. But unlike the checklist approach, the integrity systems approach looks strategically at the entire regime, working out not just what pieces are present, but what specific functions each piece serves, and how they interact. A National Exam constitutes a potentially promising candidate for incorporation into the larger integrity system. But in some cases the Exam might prove unnecessary – perversely, it might even weaken the overall system.[35] In other cases, an Exam might be a useful – even vital – part of the system. In such cases, however, the function of the Exam must be clearly understood. An Exam can play a variety of roles in helping ensure standards of knowledge – but not all these roles accord with one another, meaning the Exam needs to be designed and implemented in order to perform the specific function required in the local integrity system.

In focusing on the specific role that the Exam is required to play in a given case, the integrity systems approach prompts us to ask questions such as:

• Is the Exam the central competence-based tool, or employed in combination with other formal education standards?

• Does the Exam test competence and knowledge, or awareness of regulations and legal obligations?

• What is the Exam’s timing? Does it occur prior to any entry into the occupation, or after a period of learning and supervision?

• Who takes responsibility for administering the Exam: a government regulatory body or a professional/self-regulatory organisation?

• Who takes the Exam – all and only service providers, or some broader or narrower demographic? Are there other Exams that deal with a narrower or broader group, with proportionately higher and lower standards?

Many of the reports and inquiries noted above move beyond the checklist approach and drill down into the specific effects desired, and the way the Exam might (or might not) work with other institutions to improve standards. While

the reasoning and recommendations of the PJCCFS 2014 Inquiry,[36] the FPA’s submission,[37] and the Murray Inquiry[38] differ in terms of their proposed use of the Exam, they all looked at developing a larger system of measures into which the Exam – if employed – strategically fitted.[39]

The existing draft legislation also looks at the overall system, and proposes the Exam as one element amongst a large array of reform initiatives.

Unlike many of the above-noted proposals, the draft legislation and its accompanying explanatory material do not deal explicitly or in detail with the Exam’s function, and its interrelation to other initiatives.[40] This might seem to suggest the ‘checklist’ approach, with the Exam included simply because of its status as a common member of other regulatory systems and quasi-professional sectors. Yet the draft legislation places the Exam in the hands of its proposed Standards Body (‘Body’).[41] This action empowers the Body with the capacity to decide the Exam’s function – and subsequently its substance – in the light of the specific needs of the existing integrity system. Indeed, delegation to the Body – an institution with clear parallels to, and direct links with, professional organisations – allows the Exam to be dealt within an ongoing strategic and dynamic manner, capable of targeting the Exam’s function and substance in line with current needs.

In what follows, this article will argue that decisions about the Exam’s use and nature (either by legislation, regulation or delegated to industry bodies) need to be undertaken through such a strategic and holistic lens, in line with the integrity systems approach.

Evaluating the Exam’s costs and merits requires considering its prima facie benefits, logistical considerations, and integrity issues.

A National Exam can furnish several significant boons.[42] First, and most important, the Exam provides a check on the standard of knowledge possessed by all practitioners. While (as we will see in Part III) the Exam may suffer from various pedagogical limitations, it nevertheless contributes to ensuring a level of knowledge competence across many of the relevant knowledge domains. This result also provides a layer of quality assurance with respect to the RTOs, as RTO graduates will expect to be well-placed to pass the Exam.

Second, an Exam can standardise the knowledge that aspiring service providers should possess – and it can do so from the perspective of various stakeholders as determined through a regulatory body. This resulting standardisation (eg, of university curricula), allows settled expectations aligned across educators, students, industry (and professional) organisations, and employers.

Third, if employed in lieu of formal educational qualifications, an Exam allows diverse pathways to professional entry. Rather than being required to invest the time, effort, energy and expense of a tertiary qualification, subjects can flexibly decide what educational process they will employ to help them pass the Exam. This flexibility of pathways can expand the pool of prospective financial advisers, increasing the likelihood of attracting high quality advisers. It expands cultural diversity within the service sector (which can itself improve service quality),[43] and allows the accreditation of service providers with overseas qualifications. But in the context of financial advisers, perhaps its most important benefit lies in working as a transitional measure where existing service providers do not have educational credentials and yet may well possess, through their years of experience, sufficient expertise to warrant accreditation. The Exam offers the possibility of experienced practitioners establishing their expertise without being required to progress through the lengthy process of formal tertiary study.[44]

The logistical issues in achieving a pedagogically robust Exam look formidable.[45] The Exam’s main challenge is in assessing the wide range of sophisticated skill areas that effective financial advisers must navigate. Mark Brimble notes the knowledge domains of ‘economics, investment, tax, legal, retirement, estate, insurance, risk, business, behavioural and client engagement’.[46] ASIC itself expands this list, requiring expertise in behavioural economics, demography, budgeting, life-stages and life-events characteristics, social services, trusts, complaint processes and more.[47] Testing all these knowledge domains at a bachelor degree level presents a daunting task. The sheer number of those sitting the Exam – estimates range from 18 000 to 30 000 individuals – pose further logistical issues.[48] The issue of ‘who pays’ is also significant, as the costs of rolling out the Exam will not be small. If this cost falls on the government purse, it will further highlight the high cost to society of poor standards within the sector.[49]

In short, the Exam will require considerable pedagogical and logistical experience to avoid potentially major problems.

The Exam’s ‘integrity’ refers to its resistance to deliberate subversion through cheating. If the Exam stands as just one of a series of major hurdles to service entry, then even sharp operators may decide that honesty is the best policy. But if the Exam must shoulder this task alone, then guaranteeing its integrity will prove a much harder task.

The financial services sector’s prevailing culture and incentive structures demand attention to this issue. Normal breaches of university grading integrity (such as essay plagiarism or exam cheating) tend to be performed by individual students or small groups of students, operating off their own initiative and situational opportunities.[50] But with just a single set of Exams constituting the central barrier to accreditation, the financial services industry would present a more criminogenic environment. Here, low quality training organisations could reap significant market advantages by gleaning ways of beating the Exam, and communicating the required information to their students. So too, well-resourced licensees (such as major banks) could ensure the easy accreditation of their employees if they could breach the exam’s integrity. Even the simple act of compiling a list of the questions in the Exam’s question bank would be a significant boon to these organisations, allowing their students or employees to enjoy a solid chance of passing the Exam with minimal study.

Such cynicism cannot be regarded as fanciful.[51] The industry is already plagued by public allegations of cheating on accountability exercises,[52] and the current culture across large segments of the financial services industry displays a strong resistance to – if not outright disdain towards – accountability and professionalisation efforts.[53] This culture suggests the Exam may be confronted with well-resourced, strategic players with everything to gain by breaching its integrity. As such, a multifaceted integrity systems approach can benefit by posing multiple hurdles to strategic players.

This section explores the Exam’s various purposes, effects and limitations by looking to comparative jurisdictions, different modes of raising standards of competence, and through comparison to the ways that established professions employ Exams.

In making its argument for the Exam, ASIC highlights that: ‘[in] several other jurisdictions, examinations are mandatory for satisfying the registration requirements for financial advisers’.[54] CP153 notes specifically the United States of America (‘USA’), the United Kingdom (‘UK’), Canada, Hong Kong, Singapore and New Zealand.

The reasoning appears based on a checklist approach: other jurisdictions employ an Exam, suggesting that this is an established mechanism for ensuring minimum standards. However, drilling down into the details of each jurisdiction shows the Exams play different roles.

The New Zealand Exam, for example, focuses on codes and consumer protection obligations. Rather than ensuring a core knowledge base, its purpose is to guarantee knowledge about legal and moral responsibilities.[55]

In the UK, the Exam is just one tool in a larger portfolio, including formal educational qualifications and membership in an accredited professional organisation.[56] In employing an array of interlinked mechanisms, the UK’s regime (reformed by the Retail Distribution Review in 2012) provides a multifaceted integrity systems approach.

The USA differs, taking something more like the ‘panacea’ approach

(a similar situation holds in Canada). The USA system employs different

exams (the Series 7 and Series 79) for different financial services occupations.[57] The Series 7 exam is designed, implemented and mandated by a self-regulatory body, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (‘FINRA’).[58] Aside from FINRA, professional organisations are not granted any special legal status – though such organisations exist on a voluntary basis, utilised for an

adviser’s personal branding.[59] Eschewing both formal educational credentials and mandated professional accreditation processes, the Exam stands as the lynchpin mechanism in ensuring financial advisers’ competence.

In sum, each nation’s integrity system differs from the others, and each employs its Exam in different roles.[60] Plausibly therefore, any decision to employ the Exam should be made in the context of examining the specific role that needs fulfilling in the particular context.

As we just saw, various jurisdictions use university graduation as a way of improving standards in financial advice. This accords with the widespread view that providing quality financial advice involves the equivalent of a bachelor degree level of educational sophistication.[61]

But can such levels of educational sophistication be judged by a single program of exams? One might suppose that if such a strategy was viable, that universities themselves would have installed it long ago.[62] After all, regular assessment, multiple times each semester, is costly and time-consuming, especially when we factor in resource-intensive testing such as assignments, team projects, essays and case studies.[63]

Why then do universities use such tools? Different types of testing evaluate different skill sets, professional attributes and types of knowledge.[64] Such assessments can appraise students that tend to ‘test poorly’ even though they have a strong grasp of the knowledge outside of the specific, high-pressure, time limited written exam context. Ongoing testing can also triangulate performance over a period of time, ironing out across students having ‘off days’, or battling transient health or emotional issues. So too, prolonged university testing regimes can reward students who grasp and build on prior knowledge, rather than those who cram information into their short-term memory long enough to regurgitate it in a multiple-choice exam. University exams can go into considerable depth on specific subjects, as a course’s overall assessment comprises many smaller tests.[65] The flexible and multistage assessment undertaken by universities carries other pedagogical benefits – including empowering course designers with the capacity to mitigate and learn from their own mistakes in assessment design.

A single Exam carries none of these advantages. Even a well-designed program, covering all of the key areas with sufficient and varied questions to ensure appropriate content coverage, will inevitably prove a narrow grading tool when compared to the flexible portfolio of options available to the university.[66]

The difference between the Exam and the bachelor degree extends beyond the difference in the way that each tests subjects. It also manifests in the ways university learning occurs, even if such learning does not show up in grading exercises. Submissions to the PJCCFS 2014 Inquiry noted several of these differences, stressing that degree recipients would:

• have broad, theoretical, technical and coherent knowledge as well as the skills for professional work, rather than paraprofessional;

...

• have the skills to analyse, generate and transmit solutions to unpredictable and complex problems; and

• be able to communicate their knowledge, skills and ideas to others.[67]

Further benefits accompany more sophisticated pedagogies, such as ‘authentic learning’ and ‘work-integrated learning’ processes, which teach practical skills that no Exam can hope to capture.[68] As such, while universities routinely employ exams, they also utilise other forms of learning and assessment experiences that go far beyond what a single Exam can achieve.

We noted earlier the sector’s quasi-professional elements (including those in reform proposals and draft legislation). In this connection, many professions employ an Exam alongside a variety of devices to ensure competence, including:

• Mandatory university degrees in the relevant area (garnering the above-noted learning and assessment benefits);

• Apprenticeships and/or other periods of supervised work (eg, internships, ‘professional years’);

• CPD schemes;

• Self-regulation, which includes communication and oversight of ethical codes (including competency standards).

This section considers the ways that professions have engaged with universities, exams and life-long learning initiatives.

Historically, professions have a complex relationship with employing an exam as a condition of entry. Scots and English accountants secured royal charters in the 19th century (starting with the Edinburgh Society of Accountants in 1854) and soon started setting written exams for new entrants.[69] In each case, there were multiple examinations that tested what was thought to be readily testable knowledge. This was not an isolated event. The 1854 Northcote-Trevelyan Report[70] into the British Civil Service was much taken by the idea of merit (as compared with birthright or bribery) and the Chinese Empire’s system of examinations to assess it.[71] Written examinations were introduced for the British Civil Service and, at the same time, universities started shifting from

oral to written examinations.[72] Professions setting examinations for prospective members fitted this trend. It also served professions where training had been apprentice-style with sole or small group practitioners. Even when universities provided clear routes to the professions, longstanding apprentice-style education, supplemented by examinations, provided a path to the professions. For example, while most Australian-trained lawyers studied in law schools from the 1850s,[73] there was an alternative entrance through exams right into this century. Indeed, some of Australia’s most distinguished jurists took this route.[74] However, these exams were not taken in isolation but backed up by lectures and apprentice-style learning. Solicitors had the choice of taking articles after the completion of university exams (via the university route) or before the commencement of exams (via the non-university route).

Similar stories could be told about doctors, which emerged from various guilds (including the ominously titled ‘barber surgeons’, which did not separate until 1745[75]) and hospital training. While the creation of university degrees took on a great deal of the education requirements, there remained a heavy hospital component with residency, a post-university training regime and the training and examinations of various ‘colleges’. Nursing quickly made a similar transition, with job-based training extruding much education to the university degree course (that itself recognised the critical role of in-hospital training).

In none of these cases was the examination seen as a panacea, or adopted simply on the basis of checking a box that other occupations employ. Rather, the Exam was seen as filling an important function in the standardisation of knowledge that professionals could be expected to demonstrate, and in the education of the relevant professionals.[76] In all cases, the Exam was run by professional organisations, rather than state regulators. This linked the Exam with different status and obligations, by initiating its subjects into a select community, with its own standards, demands and codes.[77]

The rise of the examination emphasised the once-off testing of knowledge, implying that education is intensive but limited in time – a stage a professional goes through rather than a process that continues through their professional life. Yet in most current-day professions, the Exam remains only one part of professional education and training, with other learning processes playing a significant role.

In contemporary contexts, the need to regularly update knowledge grew. Rapid advances in thinking, technology and practice required professionals to update their knowledge – sometimes incrementally but increasingly radically – and to develop and rethink the knowledge base of their activity.[78] These influences led to the concept of ‘life-long learning’. This was not a new idea: professional education traditionally constituted a form of lifelong learning – starting with an apprenticeship and continuing as members of tight-knit groups interacted, shared knowledge and discussed problems. Professions claimed to be, and often were, knowledge communities.[79]

University education makes up merely the most intensive learning part of a lifelong learning process in which different skills and knowledge are acquired (and then reinforced) at various stages. Post-university, education continues in placements, clerkships, pre-admission professional courses, supervised practice, discussions with mentors, professional advice hotlines and interaction with clients.[80] This learning process extends through professional life, as exemplified in CPD programs.[81]

While this use of apprenticeships, mentoring and supervised work forms part of many traditional professional integrity systems, these initiatives cannot be assumed to work the same way in all contexts. In most professions, existing members already possess a solid level of knowledge, skills and ethics. Under these circumstances, the integrity system’s goal is to ensure that new entrants meet these existing standards. But in the case of financial services, reform initiatives are required precisely because of the existing industry’s low standards, dramatised by its regular scandals.[82] In this case, reforms need to avoid inculcating novices into the existing ‘business as usual’ practices. Instead, the goal must be for leaders to learn and teach at the same time – not passing on past practices, but developing new practices.

This section’s overall lessons about education and training initiatives can be summed up in terms of competencies. Examinations are traditionally thought to be good for testing knowledge, but limited with respect to testing its application.[83] Professions long considered that competencies based on skills and client interaction were best learnt in apprentice-style environments. Even today, university attempts to do this remain a theoretical preparation for subsequent external learning.[84] Such practical competencies are not only not best taught at university – they are quintessentially not the kind of proficiencies that can be best tested by written examination rather than through oral examination and role play.

We noted earlier that many of the problems plaguing the financial advice sector were ethical failures as much as competency failures. Exams and university education are typically seen as responses to the latter issue. However, both carry implications for ethical development.

First, any substantial competency-based requirement alters service providers’ investment in their occupation. One of the things the Exam can do – and a degree course does even better – is to raise barriers to easy market entry, inflating the costs and investments in money, time and energy required to practice. When few ‘hoops’ stand in the way of market entry, the costs of being suspended or prohibited from practicing drop; a fraudster or negligent operator can simply move to another (perhaps cognate) service area with little lost investment. But practitioners who have had to undertake years of study and pass difficult Exams have begun careers. Their mentality differs from the easy-come, easy-go salesperson, and the prospect of suspension or debarment looms as a weightier consideration. They have more reason (albeit a self-interested reason) to take their ethical responsibilities seriously.

Second, even setting aside dedicated courses on professional or business ethics, university courses can impact on students’ ethical character.[85] Prolonged teaching, examination and nuanced grading can introduce the student to standards of excellence in the face of the intellectual challenges inherent in the activity (such as of giving expert advice to people in complex financial situations). The student learns how to excel at the practice in a context devoid

of skewed incentives provided by commissions or occupational rewards.[86] Furthermore, a degree course offers three years of potential community building and so of identity building, giving students an opportunity to identify themselves as part of a community, and understanding that community in ways shaped by their learning. Finally, the university degree can provide the student with mentors and future professional colleagues capable of giving independent advice and assistance in dealing with moral dilemmas arising in later professional life.

In such ways, the instruments employed to ensure knowledge competencies can impact upon ethical competencies. Weighing up the Exam’s overall impact requires factoring in the way it might (adversely or beneficially) impact ethical compliance. This point also applies to the Exam’s impact upon potential professionalisation efforts. While professions encounter their own problems with ethical compliance, professions do enjoy their own special capabilities when it comes to facilitating and standardising ethics.[87] For this reason, implementing the Exam in a way that promotes professionalism can hope to set the stage for future ethical interventions.

Summing up, universities possess teaching and assessment capabilities well beyond those offered by the Exam. Yet the educational tools employed by professional organisations extend further again. As well as professional Exams and university credentialing, professions employ various types of apprenticeships (in early years) and continued education requirements (in later years). If the goal of reform efforts is to facilitate professional standards of financial advice, then the full portfolio of professional integrity systems may need to be brought to bear.

This section considers the Exam’s potential risks, and reviews how an Exam can be strategically situated into a particular integrity system in order to perform a specific task.

Both the ‘panacea’ and the ‘checklist’ approach carry the implicit assumption that the Exam will necessarily improve competency standards. In fact, there are several ways the Exam might degrade standards. When strategically injecting the Exam into the existing integrity system, care must be taken to ensure that it complements other elements, and that it does not stymie the growth of vital new practices and institutions.

Perhaps the Exam’s most serious integrity risk manifests when it is set at a low level of difficulty and is unsupported by other competence measures. Such an Exam’s minimum standards can eclipse the significance of other competence measures.[88] The Exam may smear the distinction in the public mind, and in the thinking of clients and prospective clients, between mere salespeople/brokers, and genuine financial advisers.

While smearing this distinction would be an unintended consequence of imposing the Exam, brokers may deliberately wish to erode the distinction. Such persons have everything to gain by presenting themselves as equally competent and trustworthy as compared to members of fully-fledged professional organisations. Introducing the Exam allows brokers to assure prospective clients that they are independently vetted and that they sit the same Exam as all the other practitioners. This exact issue played out in legislative wrangling in the USA in 2012, as different sides of the Congress debated between widening the use of the minimum standards Exam operated by FINRA for brokers, versus expanding the use of a higher level professional examinations procedure. The former policy, opponents argued, would muddle the differences between brokers and professional financial advisers – meaning that an increase in regulation and standards (through imposing the low standards Exam) might perversely lead to a decrease in the quality of service provision.[89]

Top-down governmental regulation can weaken the public demand for greater self-regulation, even as it weakens the branding power of professional bodies.[90] As the government increasingly shoulders responsibility for ensuring compliance, the need diminishes within the wider community and the industry for the sector to self-regulate. With weaker demand, the prospects for professionalisation deteriorate.[91] Since effective professions tend to provide stronger levels of ethical compliance,[92] and can take upon themselves many of the costs of ensuring compliance, this could prove a considerable setback.

Of course, this argument only goes so far. Even if the imposition of the Exam might weaken the growth of self-regulation, this concern must be weighed against the actual movement towards professionalism so far evinced. That said – and as the existing draft legislation exemplifies – government and regulators do possess tools that encourage self-regulation, such as by empowering professional membership through legally protecting title and function, that can be deployed alongside the Exam.[93] The work of the Professional Standards Council (‘PSC’) is another method by which professional bodies can be officially recognised and rewarded for high standards.[94]

Just as regulators can mistakenly suppose that an appropriately pitched Exam will necessarily improve standards, the general community may fall prey to a similar error. In creating an aura of professionalism, the Exam risks instilling false confidence in clients that the government has ‘cleaned up’ the sector. Any measures that enhance the community’s credulity without actually improving standards can work to reward wrongdoers, undermine clients’ informed consent, and set the stage for future scandals. After all, the purpose of reform is not to improve trust in a sector, but rather to render the sector trustworthy. To this extent, the Exam’s sheer visibility may prove problematic. Behind the scenes measures may work better, precisely because these encourage the community to dole out its trust on the basis of actual changes in behaviour, rather than in a perception of promised improvements.

Pitching the Exam at different levels of difficulty allows it to play different roles. Let’s term the minimum expert knowledge required to competently serve clients, perhaps in a supervised role, as the ‘standard knowledge’ (for financial advisers, this equates to a bachelor level degree). Depending upon what the integrity system needs, the Exam might test standard knowledge, or a higher standard, or a lower standard.

Pitching the Exam to test the standard knowledge can fulfil several of the roles canvassed in Part II, including standardising shared expectations and providing a layer of oversight for RTOs.[95] This last objective loomed large in ASIC’s reasoning.[96] If the RTOs display variable pedagogical quality, or can be tempted to grade their students too easily (both acknowledged features of the current environment[97]), then the Exam’s testing of the standard knowledge guards against market entry of low quality aspirants emerging from low quality RTOs. If an Exam at this level constitutes the lone competency-based initiative (for existing advisers), then it can also allow flexible modes of service entry, working as a transitional device to accredit existing financial advisers without requiring them to complete years of formal university study.

Pitching the Exam below the standard knowledge can also serve several useful functions. If the ‘standard knowledge’ constitutes the level of learning required for quality service in the most difficult and challenging service areas, then the Exam might instead be used to accredit service providers for more basic services. We noted earlier the distinctions between Tier 1 and Tier 2 financial products, and between giving personal versus general advice. Pitching the Exam at a basic level could thus accredit service providers for general advice about Tier 2 products. This would ensure a minimum level of knowledge competence across the entire financial services industry, allowing those aspiring to give complex and personal financial advice to fulfil further requirements.[98]

A lower-standards Exam can also work as a transitional measure. In an existing situation with low formal education requirements, introducing such an Exam could be swiftly implemented and applied to both existing and entering financial advisers. While the Exam’s standards may not be ideal in the longer term, it might prove a useful stopgap measure until existing advisers manage to upscale their expertise, and RTOs (including universities) develop sufficient places in appropriate courses.

An Exam may also test above the standard knowledge level. In this case, university qualifications could qualify the aspirant to enter the industry at a provisional level. The Exam would come later, after a mandatory period of supervised work or further learning. Given the Exam’s later positioning, it could test for knowledge and expertise acquired through work experience, or from additional studies. This approach parallels many professional exams, where colleges (for instance in legal and medical specialisations) test for expertise far beyond what the initial degree assessed. Such an Exam functions as the gateway into full professional status.

The Exam can thus fulfil a variety of purposes, depending upon its content and its grading standards. Equally, an Exam cannot fulfil all these purposes; it is not one size fits all. The Exam’s content and standards must reflect the function it needs to fill within the larger integrity system, given that system’s existing gaps, challenges and opportunities.

The current draft legislation, while not itself explicit about the Exam’s function, allows the Exam to be taken after a ‘professional year’ of supervised work.[99] This opens the possibility of testing not only the standard knowledge, but even a higher, more demanding level of knowledge. However, it may turn out that the most significant feature of the proposed regime is that it places the substance and administration of the Exam in the envisaged Body.[100] This allows an expert group to be strategic about exactly what role/s the Exam needs to fill, and also allows the Exam’s function to shift over time. Early on, the Exam will be crucial as a transitional device allowing (in partnership with other requirements) for the accreditation of existing advisers.[101] After just a few years however, almost all existing practitioners will have made this transition, allowing the Exam to be tailored towards a different function (such as testing high-level knowledge garnered from the period of supervised work experience).

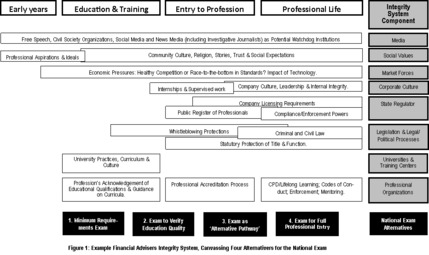

This subsection relates one illustrative case where the Exam might be strategically deployed within an integrity system to play an important role – with other measures employed to mitigate the risks such an Exam might pose. Figure 1 (see the end of this article) graphically portrays the overall integrity system, and the different alternatives for positioning the National Exam within it.

The integrity system comprises an array of diverse elements:

• licensing requirements (for individuals and/or companies);

• registers and records held by an independent body (for example, government regulator);

• education standards from RTOs or universities – themselves subject to their own integrity systems;

• government regulation (for example, through a regulator such as ASIC), including regulations about structuring and disclosing remuneration packages;

• market pressures and occupational reward mechanisms – which can create a race to the bottom in the provision of ‘invisible quality’[102] – but in other circumstances can create pressure for improved products and services;

• courts and the relevant criminal and civil law (such as for negligence or fraud), including the impact of legal indemnities;

• professional bodies, including their practices of CPD, codes of conduct and compliance measures, and other accreditation mechanisms;

• government organisations encouraging and facilitating professional organisations (for example, the PSC);

• statutory control of functions and titles (‘financial adviser’ and ‘financial planner’);

• media as a watchdog institution, impacting on the social status of financial advisers, and the political will for reform;

• whistleblowing protections – for financial advisers themselves, but also for related integrity system elements, such as university employees, and government regulators;

• the wider community’s cultural expectations of ethics and competence in the sector, and the impact these expectations have upon financial advisers at different career stages;

• leaders and mentors within the industry and its education providers;

• employers – especially banking and financial institutions – with internal integrity systems of their own.[103]

How might an Exam be situated into such a multifaceted integrity system? One role for the Exam might be employed by the professions themselves, imposed at the end of a lengthy period of probation and supervised work, as a high standards gateway to full professional accreditation (Option 4 in Figure 1). Another role may be to set ‘minimum requirements’ for any role within the financial services sector (Option 1 in Figure 1) – thus applying to paraprofessionals and salespeople offering general sales information on basic financial products. Leaving higher formal qualifications required only for financial advisers offering complex and personalised financial advice, the Exam could ensure a baseline level of competence across the industry. Alternatively, in cases where universities and RTOs fail to perform adequately, the Exam could be used directly after graduation as a check on education quality (Option 2). Finally, the Exam could work as a transitional device (perhaps in concert with other elements), providing existing financial advisers with an alternative pathway to the required accreditation (Option 3).

While there is no perfect solution to remove potential risks posed by the Exam, the integrity system can employ various devices to allay these possibilities. Above all, the Exam must be instituted in such a way as to resist breaches to its own integrity. Attempts at systematic, long-term, institutionally facilitated cheating should be anticipated and the Exam explicitly designed to withstand such attempts. If transitional arrangements place the Exam as the major gateway to the accreditation of existing practitioners, then other elements may be required to guard against low quality providers inculcating a new generation into their practises. For example, the regulator might require that only fully qualified financial advisers (that is, holding a formal degree and membership in an accredited professional organisation) can provide accredited supervision for new practitioners. The regulator might similarly require all licensees to employ only fully qualified advisers as compliance officers, or as managers in large companies. True, these measures may deleteriously impact upon the role and prospects of existing high quality advisers who lack formal qualifications. But without such measures, the Exam stands as the only hurdle preventing existing low quality practitioners from plying their trade, and even from taking on crucial supervisory and compliance roles where they could influence the next generation. In effect, this would be to view the exam as a panacea for the industry’s competency problems – a position this article has aimed to discredit.

As the discussion of lifelong learning underscored, the key questions surround what is to be taught and when, recognising that many elements, including formal knowledge, practical techniques, and ethical insights, will be learnt through all stages. A National Exam can play a role in testing relevant knowledge and, to a lesser extent, ethical understanding. Passing such Exams is hardly sufficient to ensure that practitioners would be either ethical or competent. But it could form part of a suite of mutually reinforcing integrity measures that provide safeguards against the kind of behaviour that not only deprived many Australian investors of their life savings but brought capitalism to the brink of global collapse.

Alongside all of the elements of the integrity system governing the Australian financial services industry, the National Exam stands as just one option for raising standards. Introducing it may well prove beneficial, but only if it is strategically placed amongst other new and existing elements, in such a way as to enhance and complement their functioning, rather than replacing or distracting from it.

[*] Research Fellow, Institute for Ethics, Governance and Law (IEGL), Griffith University. (Correspondence: h.breakey@griffith.edu.au)

[**] Director IEGL and Foundation Dean and Professor of Law and Research Professor in Ethics, Griffith University. Adjunct Professor, Strathmore, QUT and York.

The authors acknowledge the support of the Australian Research Council and the Professional Standards Councils for this work. They are also grateful for the support of professional partners to the grant, law firms Allens and Corrs. The authors also acknowledge the support of the Centre for Law Markets and Regulation at UNSW Law and the Law Futures Centre, Griffith University for this work.

[1] See, eg, Solicitors Regulation Authority (UK), ‘Consultation: Training for Tomorrow: Assessing Competence’ (Consultation, 7 December 2015) <http://www.younglegalaidlawyers.org/sites/default/

files/SRA%20SQE%20consultation%20paper.pdf>.

[2] See Noel Preston and Charles Sampford, ‘Institutionalising Ethics’ in Charles J G Sampford, Noel Preston and Carmel Conners (eds), Encouraging Ethics and Challenging Corruption (Federation Press, 2002) 32; Charles Sampford, Rodney Smith and A J Brown, ‘From Greek Temple to Bird’s Nest: Towards a Theory of Coherence and Mutual Accountability for National Integrity Systems’ (2005) 64 Australian Journal of Public Administration 96; Hugh Breakey, Timothy Cadman and Charles Sampford, ‘Conceptualizing Personal and Institutional Integrity: The Comprehensive Integrity Framework’ in Michael Schwartz, Howard Harris and Debra Comer (eds), The Ethical Contribution of Organizations to Society (Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations vol 14, Emerald Group Publishing, 2015) 1. See also Financial Planning Association of Australia, Submission No 6 to Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Inquiry into Proposals to Lift the Professional, Ethical and Education Standards in the Financial Services Industry, 5 September 2014.

[3] Exams can come in different forms, from a single online multiple-choice test, to simulations, role-plays and practical tasks measuring oral skills: see, eg, Solicitors Regulation Authority (UK), above n 1, 17 [38].

[4] Australian Securities and Investments Commission, ‘Regulatory Guide No 146: Licensing: Training of Financial Product Advisers (at July 2012) <http://download.asic.gov.au/media/1240766/rg146-published-26-september-2012.pdf> (‘RG146’).

[5] Ibid 15 [38].

[6] Ibid 6.

[7] Ibid 8 [13].

[8] Treasury (Cth), ‘Corporations Amendment (Professional Standards of Financial Advisers) Bill 2015’ (Exposure Draft Explanatory Material, 2015) 4 <http://www.treasury.gov.au/Consultationsand

Reviews/Consultations/2015/Raising-professional-standards-of-financial-advisers>.

[9] RG146, above n 4, 5.

[10] Mark Brimble et al, ‘Collaborating with Industry to Enhance Financial Planning and Accounting Education’ (2012) 6(4) Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal 79, 80. Work has also been done examining the ‘readiness’ of the industry to professionalisation: see Deen Sanders, Professional Enlightenment of Financial Planning in Australia (Professional Doctorate Thesis, Central Queensland University, 2010) <http://hdl.cqu.edu.au/10018/918259> Deen Sanders and Alex Roberts, Professional Standards Councils, ‘White Paper: Professionalisation of Financial Services’ (September 2015) <http://www.psc.gov.au/sites/default/files/NEW-PSC%20Whitepaper_final.pdf> .

[11] For example, within the sector are bodies such as the Financial Planning Association (‘FPA’), which require university degree certification and Continuing Professional Development, set down a code of ethics, and so on: see Financial Planning Association, Professionalism (2015) <http://fpa.com.au/

professionalism/>. At present, such bodies are purely voluntary, and membership is not required by law.

[12] See Hugh Breakey, ‘Supply and Demand in the Development of Professional Ethics’ in Marco Grix and Tim Dare (eds), Contemporary Issues in Applied and Professional Ethics (Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations vol 15, Emerald Group Publishing, 2016) 1.

[13] See Australian Securities and Investments Commission, ‘Licensing: Conflicted Remuneration’ (Regulatory Guide No 246, March 2013) <http://download.asic.gov.au/media/1247141/rg246.pdf> . See also Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 963E, 963G‑–963H. On prioritising client interests, see Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 961B–961J.

[14] In most established professions, only members of a full-fledged professional organisation can perform certain functions, and use certain titles.

[15] Poor or unethical financial advice feeds into a larger issue of Australian banking standards, including – at time of writing – calls for a Royal Commission: see, eg, Bill Shorten, ‘The Bank Hearings are a Political Stitch-Up Designed to Protect Them’, The Guardian (online), 4 October 2016 <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/oct/04/the-bank-hearings-are-a-political-stitch-up-designed-to-protect-the-banks>.

[16] Australian Securities and Investments Comission, ‘Licensing: Training of Financial Product Advisers – Update to RG 146’ (Consultation Paper No 212, 24 June 2013) 7–10 (‘CP212’).

[17] See, eg, Anthony Klan, ‘New Financial Advisers Less Likely to Hold University Degree’, The Australian (online), 9 December 2015 <http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/financial-services/new-financial-advisers-less-likely-to-hold-university-degree/news-story/5a0737286be5a39515f7377c1049081d> .

[18] See Australian Securities and Investments Commission, ‘Licensing: Assessment and Professional Development Framework for Financial Advisers’ (Consultation Paper No 153, Australian Securities and Investments Commission, 6 April 2011) 14 [38] <http://download.asic.gov.au/media/1332914/

cp153.pdf> (‘CP153’).

[19] CP212, above n 16, 38 [108].

[20] In late 2015, the figure was 37 per cent and trending downward: see Klan, above n 17.

[21] June Smith, ‘Ethics and Financial Advice: The Final Frontier’ (Report, Argyle Lawyers, 2010) 15 ff.

[22] Ibid 5 [12].

[23] The legislation is expected to be introduced in 2016, with the new regime beginning in 2019. See Kelly O’Dwyer, ‘Professional Standards for Financial Advisers to Benefit Consumers’ (Press Release, 17 October 2016) <http://kmo.ministers.treasury.gov.au/media-release/094-2016/> .

[24] CP212, above n 16, 16‑–17 [40]. Paragraph 40 positions the exam as the fundamental guarantor of minimum standards. See also Patrick Durkin, ‘ASIC’s Greg Medcraft Wants US-Style Exam for Financial Planners’, Australian Financial Review (online), 12 January 2015 <http://www.afr.com/

news/asics-greg-medcraft-wants-usstyle-exam-for-financial-planners-20150112-12mdyg>.

[25] Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Parliament of Australia, Inquiry into Proposals to Lift the Professional, Ethical and Education Standards in the Financial Services Industry (2014) 47–8 (‘PJCCFS 2014 Inquiry’). For an approach similarly building on existing integrity system elements, see Mark Brimble, ‘Why We Still Don’t Expect Financial Planners to Sit an Exam’, The Conversation (online) 15 January 2015 <https://theconversation.com/why-we-still-dont-expect-financial-planners-to-sit-an-exam-36208> (‘Financial Planners Exam’).

[26] Financial Planning Association of Australia, above n 2.

[27] Commonwealth, Financial System Inquiry, Final Report (2014) 222 ff (‘Murray Inquiry’). In a similar vein, Smith’s report on ethical failures recommends introducing an undergraduate degree requirement, but not an Exam: Smith, above n 21, 7 [31].

[28] These are described in detail in Treasury (Cth), ‘Exposure Draft Explanatory Material’, above n 8.

[29] Ibid 5, 11–12, 29.

[30] Ibid 15 [2.8].

[31] Ibid 7 [1.3]–[1.4].

[32] Ibid 30 [4.9]; O’Dwyer, above n 23.

[33] The FPA, in their 2014 submission to PJCCFS’ inquiry, invoke the language of a ‘checklist type approach’: Financial Planning Association of Australia, above n 2, 51.

[34] The integrity systems approach arose out of the recognition that the best way of combating corruption and promoting integrity is not through a single law and anti-corruption agency (the Hong Kong Independent Commission Against Corruption model). First, what is needed is a combination of state institutions and agencies (courts, parliament, police, prosecutors), state watchdog agencies (ombudsman, auditor general, parliamentary committees), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the norms (including values and laws) and incentive mechanisms by which relevant groups live. Second, this combination of interconnecting norms, institutions and mechanisms is primarily directed at promoting the positive goal of good governance rather than merely containing corruption (which is one form of governance failure): see Charles Sampford, ‘Law, Institutions and the Public/Private Divide’ (1991) 20 Federal Law Review 185. This combination of institutions has been given various names, including an ‘ethics regime’: see, eg, Charles Sampford, ‘Institutionalising Public Sector Ethics’ in Noel Preston (ed), Ethics for the Public Sector: Education and Training (Federation Press, 1994) 14; and an ‘ethics infrastructure’: see, eg, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Trust in Government: Ethics Measures in OECD Countries (2000) 23–5). Here, we employ the preferred term, ‘integrity system’ from Jeremy Pope, Confronting Corruption: The Elements of a National Integrity System (Transparency International, 1st ed, 2000).

[35] See Part IV.

[36] PJCCFS 2014 Inquiry, above n 25. Brimble follows a similarly holistic approach when weighing whether a National Exam could form ‘part of a broader framework that builds on existing elements such as higher education degrees in financial planning, professional associations and the Professional Standards Councils framework’: Brimble, Financial Planners Exam, above n 25.

[37] Financial Planning Association of Australia, above n 2.

[38] Murray Inquiry, above n 27, 222 ff. In a similar vein, Smith’s report on ethical failures recommends introducing an undergraduate degree requirement, but does not recommend a National Exam: Smith, above n 21, 7 [31].

[39] In its reform proposal, the FPA submission specifically critiqued a ‘checklist type approach’: Financial Planning Association of Australia, above n 2, 51.

[40] Treasury (Cth), ‘Exposure Draft Explanatory Material’ above n 8.

[41] Ibid 7.

[42] Many of these benefits, in the context of the legal profession, are considered in the recent consultation on a UK Solicitors Exam: see Solicitors Regulation Authority (UK), above n 1, 15 [36]–[37]. By comprehensively canvasing the merits, costs and possible unintended consequences for different stakeholders, the Solicitors Regulation Authority consultation presents an excellent example of the integrity systems approach.

[43] The Exam may be able to mitigate any ‘unnecessary barriers’ that current educational pathways pose to particular groups: see especially Solicitors Regulation Authority (UK), above n 1, 8 [10].

[44] See, eg, Peter Ryan, 'Financial Planners May Quit If University Degree Requirements Mandated', ABC News (online), 25 January 2016 <http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-01-25/financial-planners-will-need-degrees/7112554> . The existing draft legislation appeared to require existing advisers to complete both formal qualifications and the Exam – mitigating the latter’s role as a transitional measure: see Treasury (Cth), ‘Exposure Draft Explanatory Material’, above n 8, 7. However, the Minister recently clarified that existing advisers may avoid degree courses through approved bridging courses: see Treasury, Australian Government, ‘Progressing Professional Standards Reforms’ (Media Release, 28 April 2016) <http://kmo.ministers.treasury.gov.au/media-release/045-2016/> .

[45] Brimble, Financial Planners Exam, above n 25.

[46] Ibid.

[47] CP212, above n 16, 51 ff.

[48] Brimble, Financial Planners Exam, above n 25. Many of those who fail the Exam will want to resit, adding to these numbers.

[49] In the context of the draft legislation for Australian financial advisers, at time of writing, the initial costs of the standards body will be met by Australia’s major financial institutions. The ongoing industry funding model for the body (and, relatedly, the Exam) is still being developed: see O’Dwyer, above n 23.

[50] An exception to this, where students can access well-resourced institutional backing, would be wealthy students using established industry to ghostwrite their essays: Kylar Loussikian ‘Ghostwriting Haunts Academic Appraisal’, The Australian (online), June 24, 2015.

[51] If an industry requires increased oversight because of the demonstrable presence of sharp operators, negligent practitioners and/or flagrant fraudsters, then any new accountability measures must realistically take into account how such mendacious actors will predictably respond to them: see Hugh Breakey, ‘Wired to Fail: Virtue and Dysfunction in Baltimore’s Narrative’ in Michael Schwartz and Howard Harris (eds), The Contribution of Fiction to Organizational Ethics (Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations vol 11, Emerald Group Publishing, 2014) 51, 59.

[52] Adele Ferguson and Ben Butler, ‘Cheating Rife in Financial Planning’, The Sydney Morning Herald (online), 16 August 2014 <http://www.smh.com.au/business/banking-and-finance/cheating-rife-in-financial-planning-20140815-104gkn.html> .

[53] See, eg, Andrew F Tuch, ‘The Self-Regulation of Investment Bankers’ (2014) 83 George Washington Law Review 101, 123.

[54] CP153, above n 18, 18–19 [55]; see also Durkin, above n 24.

[55] CP153, above n 18, 18–19 [55].

[56] For an overview, and for links to specific parts of the competency regime, see Financial Conduct Authority, Training and Competence (28 June 2016) <https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/training-competence>.

[57] The application of the FINRA standards to financial planners as well as to mere broker-dealers has not been uncontroversial: see Aegis J Frumento and Stephanie Korenman, ‘Professionalism and Investment Advisers’ (2013) 14 Journal of Investment Compliance 32.

[58] Tuch, above n 53, 204.

[59] Ibid, 120; Frumento and Korenman, above n 57.

[60] Finer-grained analysis reveals further differences. Even though Australia, Hong Kong and the USA all have professional organisations offering the CPA, differences prevail in each country’s professional culture. For this reason, each country may require different integrity system elements to respond to the different resulting challenges: see generally Ken Bruce and Abdullahi D Ahmed, Conceptions of Professionalism: Meaningful Standards in Financial Planning (Gower Publishing, 2014).

[61] See CP212, above n 16, 38 [108].

[62] In fact, universities did employ this method long ago; up until the 1970s, almost all university testing of knowledge was by examination. For an illustrative historical review of the use of the exam in legal education in England, highlighting its significance after the mid-nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, see Steve Sheppard, ‘An Informal History of How Law Schools Evaluate Students, with a Predictable Emphasis on Law School Final Exams’ (1997) 65 UMKC Law Review 657, 659–64. After this period, most universities developed mixed models of assessment.

[63] In some cases of professional education (such as German legal education), final exams are prioritised in lieu of continuous assessment. In this case, however, an array of other devices furnish additional support, and enculturation is achieved through different university pedagogies: see András Jakab, ‘Dilemmas of Legal Education: A Comparative Overview’ (2007) 57 Journal of Legal Education 253, 254.

[64] For a discussion in the context of the legal profession, see ibid 262–63.

[65] In the context of financial advisors, Brimble specifically notes the limitations of a single exam to cover sufficient depth in content: Mark Brimble, ‘Why We Still Don’t Expect Financial Planners to Sit an Exam’, The Conversation (online), 15 January 2015 <https://theconversation.com/why-we-still-dont-expect-financial-planners-to-sit-an-exam-36208>

[66] Prolonged and multifaceted university testing also poses challenges to cheats – an issue noted in Part II.

[67] PJCCFS 2014 Inquiry, above n 25, 41 [3.25] quoting CPA Australia and Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, Submission No 15 to Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Inquiry into Proposals to Lift the Professional, Ethical and Education Standards in the Financial Services Industry, 5 September 2014, 7.

[68] Brimble et al, above n 10, 82–3 provides examples of these ‘authentic learning’ and ‘work-integrated learning’ processes in the financial services context.

[69] R W Perks, Accounting and Society (Chapman and Hall, 1993) 16.

[70] Stafford H Northcote and C E Trevelyan, Report on the Organisation of the Permanent Civil Service, House of Commons (1854) <http://www.civilservant.org.uk/library/1854_Northcote_Trevelyan_

Report.pdf>.

[71] Damian Grace and Stephen Cohen, Business Ethics (Oxford University Press, 5th ed, 2013) 173.

[72] Sheppard, above n 62, 662–3.

[73] The law schools began at the University of Sydney in 1855 and the University of Melbourne in 1857.

[74] The Hon Justice Susan Kiefel sat the Queensland Barristers Board examinations during the 1970s while working as a legal secretary: see George Brandis, Attorney-General (Cth), Address at the Swearing-In of The Honourable Susan Kiefel AC as Chief Justice of Australia (30 January 2017) <https://www.attorney

general.gov.au/Speeches/Pages/2017/FirstQuarter/Address-at-the-swearing-in-of-the-honourable-susan-kiefel-ac-as-chief-justice-of-australia.aspx>.

[75] Royal College of Surgeons (UK), History of the College <https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/about-the-rcs/history-of-the-college/>.

[76] In some professional contexts, such as the US legal profession, ‘Bar exams’ are applied to university graduates, testing what they have generally passed in university. For an overview of different examination regimes in law, see Jakab, above n 63. In other cases, such as for specialised areas of medicine and law, the exam was used to test higher-level knowledge than that required of ordinary (general) practitioners. See Part IV for discussion of the various possible functions of the Exam.

[77] See Tuch, above n 53, 113; see Breakey, ‘Supply and Demand’, above n 12, 14, 17, 20–1.

[78] For a striking analysis of the unfolding relationship between professions and technology, and its potential implications, see Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind, The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts (Oxford University Press, 2015).

[79] When university education became an important part of professional education, this involved another knowledge community designed for learning and reflection. The claim of a service group to possess a privileged (and perhaps even monopolistic) domain of knowledge played a key role in the development of the professions: see Keith M Macdonald, The Sociology of the Profession (Sage, 1999) 9–11, 23–32.

[80] The key questions are not just what has to be taught and which stage it is taught in, but how the various forms of knowledge and skills are developed and reinforced over later stages: see, eg, C Sampford and S Condlln, ‘Educating Lawyers for Changing Process’ in Charles Sampford, Sophie Blencowe and Suzanne Condlln (eds), Educating Lawyers for a Less Adversarial System (Federation Press, 1999) 173.

[81] Historically, the largest law and accountancy firms were among the first to create strong CPD programs for their new graduates and programs for existing staff. Other professions then began mandating CPD for all their members. At the same time, there was a growth in specialised masters courses for more in-depth studies in particular areas of professional knowledge.

[82] Almost all reform proposals include schemes of supervised work: PJCCFS 2014 Inquiry, above n 25, 49 [3.62], 51 [3.74]; CP153, above n 18, 26–9; Treasury (Cth), ‘Exposure Draft Explanatory Material’, above n 8.

[83] Case studies provide one way of testing knowledge application skills – though even here examinations are not necessarily the best way to measure such knowledge application skills.

[84] But see Brimble et al, above n 10, 82–3.

[85] See, eg, Neil Hamilton and Verna Monson, ‘Legal Education’s Ethical Challenge: Empirical Research on How Most Effectively to Foster Each Student’s Professional Formation (Professionalism)’ (2011) 9 University of St Thomas Law Journal 325; Hugh Breakey and Charles Sampford, ‘Reflection: Educating Ethical Lawyers’ in Charles Sampford and Hugh Breakey (eds), Law, Lawyering and Legal Education: Building an Ethical Profession in a Globalizing World (Routledge, 2017) 203.

[86] This pursuit of excellence can motivate the virtues that help shape the practice: Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (Duckworth, 1st ed, 1981) 175–8; Breakey,‘Supply and Demand’, above n 12, 14–15.

[87] See Hugh Breakey, ‘Building Ethics Regimes: Capabilities, Obstacles and Supports for Professional Ethical Decision-Making’ [2017] UNSWLawJl 13; (2017) 40 University of New South Wales Law Journal 322. See also Breakey, ‘Supply and Demand’, above n 12, 5, 7, 10–13.

[88] See Sanders and Roberts, above n 10, 18.

[89] Frumento and Korenman, above n 57.

[90] See Philippa Baker, Mark Brimble and Brett Freudenberg, ‘Does CP153 Support the Move to a Profession?’, Financial Planning Magazine (online), 1 May 2014.

[91] See Sanders and Roberts, above n 10, 20; Sanders, above n 10, 166–71; Breakey, ‘Supply and Demand’, above n 12.

[92] Smith’s study reported ‘significantly higher ethical reasoning’ on the part of Certified Financial Planner (‘CFP’) professionals, as compared with other financial advisers: Smith, above n 21, 32. See also Part III above.

[93] Treasury (Cth), ‘Exposure Draft Explanatory Material’, above n 8.

[94] See Sanders and Roberts, above n 10.

[95] For example, the bar exam can work as ‘[an] indirect and soft form of quality assurance’: Jakab, above n 63, 264.

[96] See CP153, above n 18, [38].

[97] Ibid [49].

[98] This situation resembles the current USA landscape: see Frumento and Korenman, above n 51, 37.

[99] In one of the Explanatory Memorandum’s examples (for new financial advisers), the professional year is done before sitting the Exam: Treasury (Cth), ‘Exposure Draft Explanatory Material’, above n 8, 10 [1.17].

[100] Ibid 7 [1.5].

[101] The new regime (intended to commence in 2009) strategically employs the capability of the Exam to work as a transitional measure, with existing advisers having until January 2021 to pass the new Exam, but having until January 2024 to reach degree equivalent status: see O’Dwyer, above n 23; see also Ryan, above n 44; see also Treasury, Australian Government, ‘Progressing Professional Standards Reforms’, above n 44.

[102] Michael Davis, ‘Professionalism Means Putting Your Profession First’ (1988) 2 Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 341, 353.

[103] See Charles Sampford, ‘Adam Smith’s Dinner’ in Iain MacNeil and Justin O’Brien (eds), The Future of Financial Regulation (Hart Publishing, 2010) 23, 33–4.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2017/15.html