University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

HAIL TO THE CHIEF! THE ROLES AND LEADERSHIP OF AUSTRALIAN CHIEF JUSTICES AS EVIDENCED IN EXTRA-CURIAL ACTIVITY 1964–2017

KATHERINE LINDSAY[*] AND DAVID TOMKINS[**]

In this article we seek to address in combination two of the themes suggested for this thematic issue of the journal. The first is the theme of Chief Justices and judicial leadership. The second is the theme of extra-curial activity, including writing, speaking, broadcasting and interviews. In respect of the first theme, the text of the Commonwealth Constitution in section 71 clearly envisages a key leadership role for the person appointed as Chief Justice of the High Court, and thus it is an important subject for academic endeavour. As to the second, it is our contention that there has been a demonstrable change in both the quantity and variety of expressions of extra-curial activity by Chief Justices in the last fifty years. We would further argue that an analysis of this activity has the capacity to provide insight not only into individual conceptions of the role of a Chief Justice of the High Court, but also into what judicial leadership qualities might be evinced in carrying out such an extra-curial role. In methodological terms we would argue that our approach complements research on intellectual leadership in the context of the Court’s developing jurisprudence.[1]

This article is divided into five further Parts as follows: we commence our study in Part II with a consideration of the theory and literature of judicial leadership in the common law world. The theoretical literature is grounded in judicial behavioural studies within the discipline of political science,[2] although these scholarly concerns have also engaged those in the legal academy to some extent.[3] We also consider insights from comparative common law treatments of judicial leadership as well as the more ‘subjective’ literature reflecting the leadership philosophies of Australian judges. The existing literature on judicial leadership, not surprisingly, has privileged the study of leadership in the context of deciding cases and the development of a court’s jurisprudence. The categorisations and designations previously adopted in the course of undertaking studies of ‘jurisprudential’ leadership, we believe, have some corollaries in extra-curial leadership activities; however, they are not coextensive across the two leadership domains.

Part III elucidates our own typology arising from our analysis of the extra-curial activities of the six Chief Justices in our sample. Ours is a fourfold categorisation of leadership in extra-curial activities – intellectual, institutional, collaborative and individualist – and encompasses the two broader categories of ‘intellectual’ as well as ‘social leadership’ derived from David Danelski’s seminal 1961 paper emanating from his doctoral work on the role of the Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court.[4] Part IV of the article identifies the general characteristics of the leadership exercised by our sample of Chief Justices in the period from 1964 to January 2017. This involves some initial exploration of that complex and oftentimes elusory relationship between the character, talents, proclivities and interests of those individuals who have led the Court over the last half century and the social, legal and political environment in which their leadership has been exercised. The extent to which an individual might ‘stamp’ an institution like the High Court with the force of his or her personality and/or intellect is a tantalising question. It also raises the question of the extent to which these qualities reflect and shape a Chief Justice’s leadership philosophy. Our objective in this regard is nuance rather than dogma. We recognise that the zeitgeist of a particular historical, political, social and economic era will also play a role of varying weight in the capacity of individuals to make a mark upon an institution or role. It is this somewhat imponderable dimension, as well as an intellectual fascination with this interchange and relationship, which has inspired our investigation here. This is followed in Part V by our characterisation of the particular extra-curial leadership qualities of the Chief Justices in our chosen sample arising from their extra-curial practices.

The recognised pioneer in the area of judicial leadership research is political scientist David Danelski,[5] and his contributions to the study of judicial behaviour in that discipline have been the starting point also for legal scholars such as Tushnet,[6] Paterson[7] and Cornes[8] in their own explorations of aspects of judicial leadership. Amongst the relatively slight existing legal literature on judicial leadership, both Tushnet in his contribution on judicial leadership as a species of ‘dispersed democratic leadership’ and Paterson in his research on the House of Lords and Supreme Court in the United Kingdom draw on Danelski’s typology of leadership on multi-member appellate courts, namely task and social leadership.[9]

Danelski’s own initiation into the mysteries of the study of judicial behaviour in the discipline of political science came at the hands of his mentor, C Herman Pritchett, himself a trailblazer in judicial behavioural studies with his groundbreaking 1948 publication, The Roosevelt Court: A Study in Judicial Votes and Values 1937–1947.[10] A practising lawyer in Washington State, Danelski left legal practice to pursue doctoral studies with Pritchett at the University of Chicago on the topic of The Chief Justice and the [US] Supreme Court.[11]

Pritchett’s earlier work had posited the judge ‘as a particular kind of political actor whose activity took place within the context of a legal, institutional framework.’[12] This approach required the conceptualisation of a court as a small decision-making group and drew on psychosociological theory about the formation of attitudes and the importance of social background in framing attitudes and informing observable behaviour.[13] These roots can be seen in Danelski’s own, not uncontroversial,[14] doctoral work. Danelski’s method drew on Pritchett’s psychosociological approach[15] as well as the work of social and group psychologists Bales, Slater and Berkowitz.[16] Danelski’s methodology distinguished him from his more quantitively-focussed contemporaries and resulted in a particular qualitative focus on the leadership potential inherent in the role of Chief Justice.[17]

Whilst he never published his doctorate as a monograph, Danelski’s work is famous as a direct consequence of the repeated reprinting of two articles based on it in several collections of US materials on courts and judging.[18] The essence of his reasoning which has captured the attention of political scientists and legal scholars alike[19] is that a Chief Justice as a role within a multi-member court has a unique opportunity to exercise leadership.[20] Whilst such a role does not guarantee optimal leadership performance,[21] it invites in the scholar an investigation of a Chief Justice’s ‘esteem, ability, and personality and how he performs his various roles’.[22] Danelski posits that ‘[l]eadership in the [US] Supreme Court is best understood in terms of influence’, which presupposes both activity and interaction, and involves consideration of personal and collective expectations, values and attitudes in respect of the judicial role.[23]

In terms of the influence of a Chief Justice on the work of the Supreme Court, Danelski identifies four important objects of such influence: (1) ‘a majority vote for the Chief Justice’s position’, (2) ‘written opinions satisfactory to him’, (3) ‘social cohesion in the Court’, and (4) ‘unanimous decisions’.[24] He identifies judicial leaders in the core jurisprudential work of an appellate court as of two basic types: ‘task leaders’ and ‘social leaders’, although in rare instances a single judge may perform both types of leadership.[25] A ‘task leader’ is the judge who emerges as a key point of influence in terms of a court’s decision-making process.[26] In contrast, a ‘social leader’ is ‘a judge who smoothes over personal conflicts within the court’[27] and attends to the members’ emotional needs which may have been aroused through the exercise of focussed task leadership.[28] Danelski’s own case studies in the application of this theory of judicial leadership encompass the Chief Justiceships of Taft, Hughes and Stone.[29] Half a century on, both Tushnet and Paterson still found Danelski’s leadership categories of continuing relevance in analysing the work of apex courts in the US and UK. However, it is pertinent to note that Tushnet, in referring to Australian courts in the course of his broader argument, indicated that task leadership ‘might be

more difficult in a court with a tradition of so-called seriatim opinions’.[30] The significance of this statement is inescapable in the Australian context where there has been no tradition of ‘assigning opinions’ in a context of consensus decision-making, but rather a greater freedom in the individual Justice to fashion his or her reasons for judgment alone or in company.

Cornes’ work on leadership by Chief Justices in New Zealand is not broadly dissimilar in approach to the Northern Hemisphere material, although his leadership terminology differs from studies based on the Danelski typology. Cornes identifies three core ‘sets of roles’ for a New Zealand Chief Justice: as a ‘judge of the Supreme Court’, a ‘leader of the judicial branch’, and as a ‘constitutional guardian and statesperson’. His primary purpose in exploring these roles eschews an analysis of what he terms ‘in-court jurisprudential leadership’[31] – what in other contexts has been termed ‘intellectual leadership’. In exploring the third, ‘constitutional guardian and statesperson’, role for the New Zealand Chief Justice, Cornes adjudges that this dimension has ‘the most extensive and personal scope of operation’ amongst the three roles.[32] Of his four dimensions within guardianship and statesmanship, Cornes posits an extra-curial jurisprudential leadership function. In this respect Cornes’ categorisation of roles appears to align with our own research questions in this article. However, the enduring importance of Danelski’s theoretical framework also deserves attention, particularly in investigating its utility in studies of leadership issues in the extra-curial realm.

The second category of judicial leadership literature requiring consideration is that which reveals the views of the judges themselves on leadership in courts. The more subjective contributions by the judges themselves in the form of reflection, commentary or discussion tend to concentrate on descriptions of practical leadership in the administration of courts[33] or the determination of cases.[34] They reflect by and large the personal philosophies of the judges concerned[35] and unsurprisingly contain little in the way of theoretical approaches to leadership in the judicial sphere.[36] Nevertheless, these contributions to the bifurcated literature are valuable in a number of ways. First, they demonstrate that judges do in fact consider that their judicial role has a leadership dimension. Secondly, in bringing to bear their thoughts on judicial leadership to audiences beyond the court, the judges’ contributions serve to enhance our conception of individual judicial philosophies.

In the Australian context there is one paper which makes a distinctive contribution to this more ‘subjective’ category of literature on judicial leadership. Chief Justice Doyle’s paper presented in 2009 at the International Organisation for Judicial Training 4th International Conference comes closest to a systematic and practical assessment of leadership issues for contemporary Chief Justices.[37] In that paper then Chief Justice Doyle reported on the results of the 2006 program for Australasian Chief Justices in which they identified eight key leadership qualities for a holder of that office. In order of importance to the participants were the following characteristics: ‘developing a sense of the institution, a collective commitment to justice, and communicating this throughout the court and to the public; developing a sense of collegiality; carrying out a pastoral role in relation to the judges; jurisprudential capacity or skills; moral integrity; a commitment to all aspects of the work of the court; engendering mutual trust and respect within the court; and treating judges fairly, and in particular allocating work fairly.’[38] What is ultimately instructive about this effort by the Chief Justices themselves as reported by Doyle is the degree to which non-jurisprudential factors dominate the top half of the list. ‘Jurisprudential capacity or skills’ is a middle-ranking priority. The three most significant characteristics the judges identified at the top of their list of leadership qualities are related in various ways to the extra-curial realm: ‘institutional commitment’; communication within the court and to the public; and collegiality and pastoral skill. What this list reinforces for us is the importance of studying the extra-curial realm in research about judges and judging.

As previously discussed in Part II, virtually all of the existing literature on judicial leadership addresses the curial dimension. However, it can be argued that the activities of judges outside the courtroom also have an important role to play in our understanding of the leadership role of a Chief Justice, in particular in light of the marked increase in the volume of extra-curial writing and speech making in recent decades. The growth in extra-curial activity by Chief Justices in the last half-century includes qualitative change in the sense of recourse to more diverse media and opportunities for community engagement as well as quantitative change which is reflected in the sheer volume of contemporary extra-curial output.[39] This reopens the question of what it means to exercise leadership on an apex court. The previous model of evaluating judicial leadership essentially through judgment writing and/or bringing other judges together in that process is now only part of the picture of leadership by a Chief Justice, as the role of Chief Justice is more than simply one judge among many on a multi-member court.

There is little to cavil at in the notion that the core business of courts is deciding cases according to law. In the past this notion was rarely, if ever, questioned. Contemporary scholars are only too aware that judges are undertaking the task of deciding cases in particular social and political contexts. The question for contemporary scholars then is how to harness this understanding adequately within a framework of research on judicial leadership, particularly as a reference to context must also acknowledge the demonstrable growth in the mass media and its impact on public perceptions of the work of institutions as well as a more general social decline in trust for institutions of government. These factors pose challenges for contemporary legal scholars interested in researching judicial leadership in an era of extensive extra-curial activity. In the contemporary context, courts are consciously engaging with the public as well as deciding cases. This means that there are now at least two roles for contemporary Chief Justices on apex courts: deciding cases and engaging with the public. The question remains whether the same leadership paradigm applies to each.

In addressing the question of leadership by Chief Justices in the extra-curial realm, our methodology has consciously avoided typologies from the general literature of management and leadership. Fundamentally, these seemed to us an inapposite touchstone for the distinctive context of leadership of Chapter III courts as institutions of government. Similar caveats have been expressed by Cornes in the context of his work on the role of the Chief Justices of New Zealand. He has argued, we believe persuasively, that

[t]he way leadership is conceived of, and operates, in the judicial sphere must have a distinct quality and entail ‘leading’ in a way somehow different from leadership generally. Speaking in broad terms, at the heart of the general conception of leadership is the notion of the leader being in charge, of being able to command, to say this is what we shall do and require it to be done. The notion of leadership as command sits ill in the judicial context, or at least must be significantly modified, running as it does into obvious conflict with the constitutional imperatives of judicial independence and impartiality, and the requirements of collegiality. ... Judicial leadership might best be thought of as a matter not just of the individual (although it certainly starts there), but also a collective endeavour (hence the emphasis on top courts to the concept of collegiality); a delicate balance between collaboration and individual initiative (far more so than leadership in other contexts).[40]

Cornes is not alone in positing a different quality for judicial leadership. In the Canadian context, McCormick had previously argued that judicial ‘leadership takes various forms which stretch traditional boundaries’.[41]

In seeking to assess the utility of Danelski’s concepts of ‘task leadership’ and ‘social leadership’ in an analysis of High Court leadership in the extra-curial realm we would note first that Danelski’s work and that of Tushnet and Paterson who rely on his conceptual framework are pursuing their analyses on leadership exclusively in the context of deciding cases in apex courts. When attempting to apply Danelski’s framework to extra-curial activities, we would argue that there are points of clear convergence as well as incomplete or absent corollaries. This is in part because task and social leadership in the context of deciding cases and advancing jurisprudence in an apex court are predominantly collective activities involving all the justices of the court, and in which the Chief Justice, depending on personality, temperament, and intellectual philosophy, may embody the role as a task or social leader, or vacate this space for others. By contrast, leadership in the extra-curial realm, as Cornes has previously argued,[42] is far more consciously personal than ‘in house jurisprudential leadership’ and as a result may not always conform to Danelski’s neat dichotomy.

Our study has considered half of the Chief Justices in the history of the High Court. In this period there have been significant social, political and economic changes, all of which have had an impact on the capacity of a Chief Justice to exercise independent leadership on the Court, either curially or extra-curially. In addition to this, each Chief Justice in that time has brought his own personal leadership qualities to the office. The way in which leadership might be exercised as Chief Justice could be classified in a number of different ways.[43] What is at the heart of our interest is the evidence which might be gleaned from extra-curial activity by Chief Justices of how they conceive their role and their individual contributions to both the moulding of the role and the work of the Court as an institution and what this ultimately might say about the character of their leadership as Chief Justices. We move beyond the more traditional analysis of reasons for judgment, as important as these are, to less commonly adduced sources which might allow a complementary perspective on judges, their perception of their role, and their intellectual and professional interests.

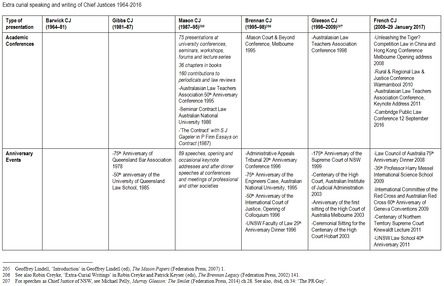

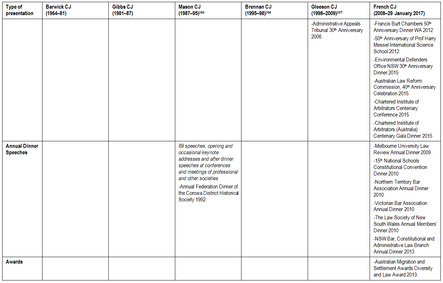

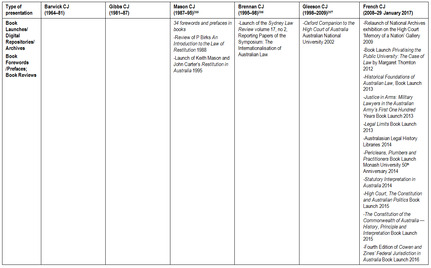

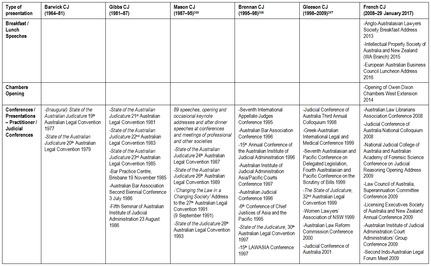

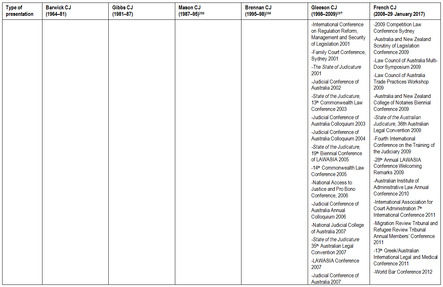

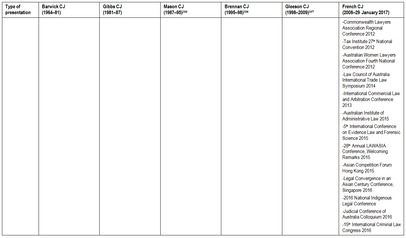

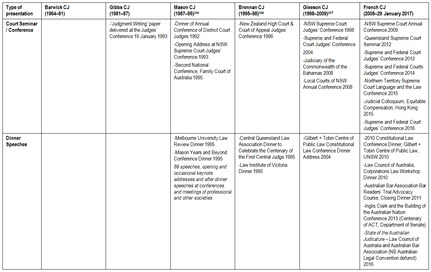

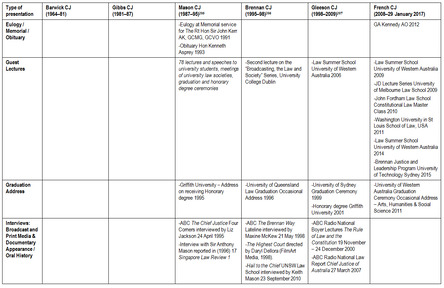

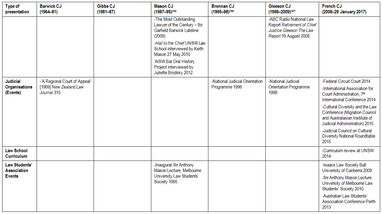

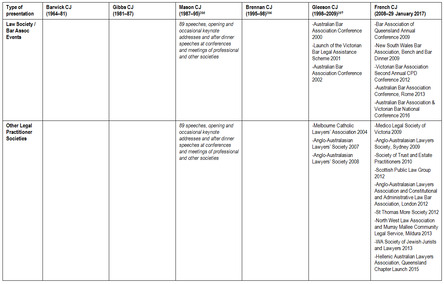

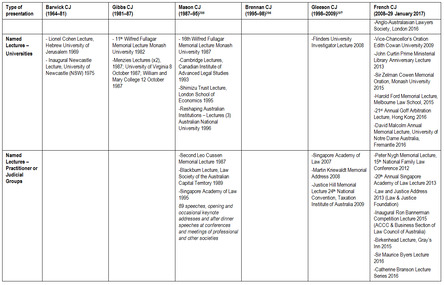

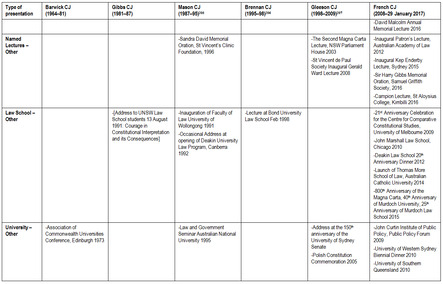

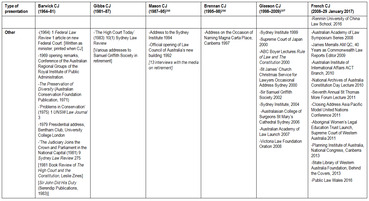

Our approach to the analysis of the empirical evidence of extra-curial practices in our sample of Chief Justices is consciously inductive. Our process of categorisation of extra-curial leadership styles has been based both on critical analysis of extra-curial activity alone, without reference to a Chief Justice’s contribution to the development of the jurisprudence of the High Court, and the consideration of the range and content of each Chief Justice’s extra-curial contributions during his time in office. This process is reflected directly in the Appendices to this article. As a result of this process, we have identified the following dimensions of leadership for Chief Justices of the High Court: intellectual, institutional, collaborative and individualist. It is also our contention that these dimensions are not mutually exclusive. The way in which this typology is exemplified in our sample is considered in detail in Part V below. In Part IV which follows, we seek to situate the leadership activity of Chief Justices in our sample within its institutional, legal, political and societal context.

In this fourth Part of our article we provide a critical assessment of the general character of the leadership of each Chief Justice appointed since 1964. In this sample an equal number achieved their position by means of direct appointment to the position of Chief Justice (the parachute model) – namely Barwick, Gleeson, and French CJJ – and by appointment by virtue of seniority on the Court (the senior puisne judge model) – Gibbs, Mason, and Brennan CJJ. There was certainly a range of reasons for the particular appointment practices of governments of the day in relation to the six most recent Chiefs,[44] but those solely political questions concerning appointment are not of any concern to our current analysis. The different appointment processes, as well as the particular personal characteristics of each appointee, are likely to have contributed to the style of leadership of each.

The limited range of existing scholarship on judicial leadership in Australia is one justification for the provision of a more general assessment of the leadership qualities of Chief Justices in our sample before highlighting the specific extra-curial leadership qualities of each of the six Chief Justices in Part V. In this way Parts IV and V of the article are designed to work symbiotically towards a deeper understanding of both judicial leadership practices and contexts. In terms of the availability of source material for our leadership analysis it is pertinent to note the relatively limited accessible intellectual biographical data on Chief Justices. The biographical method generally is not one which has been widely embraced in Australian legal scholarly circles, although there are limited signs that this is changing.[45] A number of the Chief Justices of the High Court do have full biographies,[46] but almost none of these have been written by members of the legal academy. Some of the biographies do analyse the judicial work and philosophy of the subject in some detail, most notably Phillip Ayres’ biography of Sir Owen Dixon,[47] but many more might be more generally regarded as public figure biographies rather than legal or intellectual biographies properly so called.

Intellectual biographical data is an important source of evidence for a judge’s leadership activity and incorporates, inter alia, a concern to assess the mind behind the judgments together with an assessment of those distinctive characteristics, both intellectual and otherwise, which mark out the contributions of an individual to the judicial office, in our case the Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia. We have previously employed an intellectual biographical approach with profit in seeking to mark out a role for intellectual independence as a dimension of individual judicial independence,[48] and do so again in this article in order to address the subject of judicial leadership in the extra-curial domain.

In the case of Barwick, Gibbs and Gleeson CJJ, our work of analysis has been significantly aided by the existence of full-length biographies as well as other written reflections and critiques.[49] In the case of Mason and Brennan CJJ, the presence of broadcast interviews[50] which focus on the Chief Justiceships

of each, in addition to more traditional sources,[51] has been an important and productive source of evidence for the assessment. Both the public written record and personal observation of the extra-curial activity of the most recent Chief Justice in our study, Robert French, have informed our observations.[52] One of the particularly significant elements in our analysis throughout is the use of non-textual broadcast sources in the form of television and radio interviews and documentary films. This is largely a feature of the period after the 1990s, when the curiosity of the public and journalists appears to have coincided with the interest of the High Court itself in informing the public more transparently about its work.

‘[V]ery clever, but not deep’.[53]

‘Work with Courage to Achieve’.[54]

By the time of his appointment as Chief Justice of the High Court in 1964, Sir Garfield Barwick had served in the legislature as a Member of Parliament for the NSW seat of Parramatta and in senior portfolios in the executive government as Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs. It was his realisation that he was not to rise to the position of Prime Minister that is said to have turned Barwick’s thoughts to the position of Chief Justice as a replacement for Sir Owen Dixon on his retirement.[55] Dixon had served on the Court from 1929, becoming Chief Justice in 1952 on the retirement of Sir John Latham. Barwick provided a strong contrast to Dixon in terms of both personality and experience. Dixon’s intellectual dominance of the Court was well-recognised, especially during his period as Chief Justice,[56] whereas Barwick’s reputation for legal excellence had been forged through his consummate advocacy. In his day, and before his election to Parliament in 1958, he was known as ‘a giant at the Bar’.[57] His success as an appellate advocate underlines aspects of his character which were also on display as Chief Justice: determination, drive, clear-headedness and authority.

Barwick’s appointment from outside the Court has led to longstanding discussion about whether the appointment was ‘political’ and the result has been a range of diverging assessments.[58] Perhaps the most recent reflection on Barwick as Chief Justice, including the state of the Court upon his appointment and the period immediately following, is particularly telling. Sir Anthony Mason, a later successor to the Chief Justiceship and a colleague at the Bar with a close working relationship with Barwick[59] has written recently that

he had not been an influential Chief Justice in the old Court (the Court in which he first presided). He was unfortunate in that the long shadow of Sir Owen Dixon hovered over the old Court whose members regarded themselves as the custodians of his legacy.[60]

There is also a sense in which Barwick’s transition from the executive government to the judicial branch might be seen to have been ‘uneasy’, as he was a personality whose purpose in leadership was to dominate.[61] His career was largely one of ego-driven, personal success which did not translate naturally to the Court’s quite distinctive institutional environment.

This having been said, Barwick did prove himself an effective leader of the High Court in a more modern guise than that adopted by his predecessors in the role. Barwick served an exceptionally long term as Chief Justice, from 1964 to 1981, during which time the social, economic and political landscape of the country was transformed in many ways. During the Barwick era of the High Court the legal and constitutional landscape also changed considerably; but three particular changes deserve special mention. In the period from 1968 to 1975, appeals from the High Court to the Privy Council were gradually curtailed and then abolished, the intense and overburdened workload of High Court Justices was eased with the establishment of the Federal Court in 1976, and after almost eight decades as an itinerant court, the High Court of Australia finally found a permanent home in its own building on the shores of Lake Burley Griffin in Canberra, the heart of Commonwealth governance. The hand and energy of Sir Garfield Barwick was in all of these developments to varying degrees, but it was his genius for administration and dogged persistence in a cause which saw the realisation of the vision of the Court’s permanent home,[62] together with arrangements for its budget and organisation. These qualities in Barwick had been demonstrated earlier in his time at the Bar in his skill for organisation.[63]

There can be little doubt that the assessment of Barwick’s Chief Justiceship as a whole has been overshadowed in Australia not by the greater range of his achievements in leadership of the High Court, nor by his constitutional or other jurisprudence, but by his involvement in the process by which the Whitlam Government was dismissed by the Governor-General in 1975.[64] Barwick himself has undoubtedly contributed to this particular emphasis in public perceptions through his efforts in retirement to defend his role in providing legal advice to the Governor-General concerning the exercise of the reserve powers.[65] Dogged to the last, he never lost his adversarial edge.[66]

The overwhelming character of Barwick’s leadership as Chief Justice was institutional. This left little scope for extensive forays into extra-curial speechmaking and indeed the social and legal metier of that more restrained time was unlikely to encourage excessive public pronouncements even by the most able advocates. Further, there is little evidence that Barwick’s own temperament inclined him to pursue a more ‘academic’ role in speaking and/or writing. However, one core innovation by Barwick in the extra-curial realm has stood the test of time. In 1977 Barwick delivered the first ‘State of the Judicature’ address to the Australasian Legal Convention. This address was the perfect vehicle for a leader of Barwick’s stamp. He could reflect, systematise and summarise before an informed audience. The State of the Judicature address continues as a biennial tradition to this day, even after the demise of the Australasian Legal Convention itself.[67]

In his other extra-curial speeches and publications it is not uncharitable to say that Barwick does not reveal himself as a lawyer with a natural intellectual bent. This is perhaps in contrast to his predecessor, a selection of whose papers on substantive law topics were collected for publication in 1965.[68] Barwick’s papers and speeches, not unsurprisingly, address issues associated with the operation of courts and do not tend to provide any systematised commentary on matters of substantive law. However, at this juncture, it is appropriate to acknowledge that his relatively spare extra-curial production does need to be balanced with his prodigious activity in other dimensions of the role of Chief Justice, as he conceived it, in an era in which Chief Justices were not regularly called upon by media or public institutions for public commentary.

‘Sir Harry the Healer’.[69]

‘My endeavour has been to maintain the high standards which were set by my eminent predecessors and which have, I think, earned respect for the Court not only in Australia but also elsewhere’.[70]

Sir Harry Gibbs hailed from Ipswich in Queensland[71] and in that jurisdiction was and is feted as a favourite son.[72] He was appointed to the High Court in 1970 replacing Sir Frank Kitto on his retirement. In the years immediately after Sir Harry’s appointment in 1970 the personnel of the High Court changed to such an extent by reason of retirements and deaths that within six years of appointment, Sir Harry had become the Court’s most senior member after the Chief Justice.[73] He weathered the Barwick years with his equanimity intact and rose to the position of Chief Justice by reason of seniority, appointed by the Fraser Government in 1981 on Barwick’s retirement. In some respects Gibbs’ leadership of the Court during a period of a high volume of constitutional litigation has been overlooked. This may in part be on account of his presence in the minority in key constitutional cases in the early 1980s, such as Koowarta[74] and Tasmanian Dam.[75] Another powerful reason for the more subdued interest in his Chief Justiceship may lie in the unsolicited public prominence Gibbs gained over the ‘Murphy affair’ in the later years of his tenure. Finally, the subsequent influence of his successor, Sir Anthony Mason, and the Court during his Chief Justiceship, is likely to have overshadowed Gibbs’ achievements somewhat. However, Sir Harry, too, led a court during changing times. From 1984, with the institution of the special leave process for all appeals, the High Court gained greater capacity to winnow out cases of especial legal merit.[76] Moreover, after the passage of the Australia Acts in 1986 which, inter alia, terminated all remaining appeals to the Privy Council from Australian courts, the High Court’s role as the apex appellate court for the nation was confirmed.

There are important characteristics of Gibbs as Chief Justice that require acknowledgement as pertinent to his leadership and conception of his role. First, unlike many justices of the High Court at that time and since, Gibbs did not look to Sir Owen Dixon, a product of the Melbourne Law School and Bar, as his role model. His allegiance and patterning, unsurprisingly perhaps, lay firmly in the example of the High Court’s founding Chief Justice, Sir Samuel Griffith,[77] who had played such a large part in the development and administration of the colonial Queensland legal and political system. As a consequence, it is critical to understand that Gibbs brought a philosophy of the Constitution to the High Court, a federalist philosophy.[78] In this respect he might be seen to be intellectually more like Sir Owen Dixon than might be imagined superficially,[79] and less like Barwick whose approach appears always ultimately to have been pragmatic. The application of this philosophy can be seen in action all too clearly in Gibbs’ powerfully reasoned dissents in cases involving disputes over the scope of Commonwealth legislative powers under the Constitution.

A second important characteristic of his leadership of the Court during the 1980s was his qualities of human concern and keen attention to maintaining the Court’s institutional integrity. Sir Harry’s appointment as Chief Justice was marked in the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper with the headline, ‘Sir Harry the Healer’.[80] This is at once a direct reflection on the more combative dynamics of the Barwick years as well as an acknowledgement of Gibbs’ more irenic and equable nature. This nature was tested during the difficult period from 1983 to 1986 when, as a result of the publication in national newspapers of purported conversations between judicial officers including a Justice of the High Court, criminal proceedings were instituted against them, including Justice Lionel Murphy of the High Court.

Gibbs’ handling of the ‘Murphy affair’ as it became known has been the subject of extensive commentary both at the time and since. Lionel Murphy’s own appointment to the High Court from the executive branch of government in 1975 was not uncontroversial.[81] Indeed it has been held up as a classic example of a ‘political’ appointment.[82] However, the spotlight did not fall on Gibbs directly or the Gibbs-Murphy relationship specifically until the interchange of written correspondence between the Chief and Justice Murphy over the plans of the latter to return to sitting on the High Court whilst a parliamentary commission of inquiry into Murphy’s behaviour was still sitting emerged.[83] In the correspondence between the Chief Justice and Justice Murphy at this time and which was subsequently published, each party expressed himself clearly and candidly. Two key matters emerge from Gibbs’ letter to Murphy. First, that Gibbs was genuinely concerned about Murphy’s precarious state of health, the latter having recently been diagnosed with advanced and inoperable cancer. Secondly, Gibbs, in his role as Chief Justice, is deeply attentive to the integrity of the Court as an institution in the question of whether Murphy should return to sit. In contrast, Murphy’s correspondence is both legalistic and egocentric. It cannot be doubted that it takes a particular kind of even temperament to weather the unique impact of this sort of unprecedented crisis in the Court’s history.[84] That Sir Harry had such a temperament is evidenced in his remarks during his speech at the ceremonial sitting of the High Court marking his retirement in February 1987:

I think it will always be true to say that the work of a Chief Justice of this Court is somewhat burdensome and during recent years the Court has faced unprecedented difficulties. Nevertheless I have derived much satisfaction from serving as Chief Justice of the Court. I have enjoyed the friendship of my fellow justices and have had the loyal support of the staff of the Court.

My endeavour has been to maintain the high standards which were set by my eminent predecessors and which have, I think, earned respect for the Court not only in Australia but also elsewhere.[85]

The range of Sir Harry Gibbs’ extra-curial speeches and writing throughout his professional career reflects both genuine intellectual interests and his professional ethic. Commencing in the 1950s with case notes in the University of Queensland Law Journal, the journal of his alma mater and the school at which he lectured in the early years of his professional life, to speeches in honour of the 75th Anniversary of the Queensland Bar Association, these publications reflect his deep commitment to the law and the profession. As Chief Justice, Gibbs delivered three State of the Judicature addresses in 1981, 1983, and 1985, in the last of which he did not flinch from reflecting on the critical challenges for the legal system associated with attacks on Family Court judges as well as ongoing issues for the High Court over the Murphy affair.[86] In 1982 he delivered the Wilfred Fullagar Memorial Lecture at Monash University and in 1985 returned as a valued alumnus to deliver the speech in honour of the 50th anniversary of the University of Queensland law school. Like other High Court judges of subsequent eras[87] he contributed to the ongoing professional development of members of the Bar in speaking on both appellate advocacy and appellate procedures in the High Court, once again reflecting an ethos of professional service. Only a few months after his retirement in 1987 he delivered the third series of Menzies lectures in the US, subsequently published in the Federal Law Review, a leading public law journal.[88]

It has been noted more than once that Sir Harry’s commentary on constitutional issues increased considerably after his retirement, to the surprise of some longstanding friends.[89] His leadership of the Samuel Griffith Society and membership of Australians for a Constitutional Monarchy branded him as a deep conservative in some eyes. However, these positions were not in the least inconsistent with his legal philosophy on the Court, and his contributions to conferences of the Samuel Griffith Society allowed Gibbs an outlet for his federalist viewpoint beyond the confines of academic journals.[90]

‘A quiet, penetrating man with a sharp tongue’.[91]

‘It is inevitable, with the passage of time, that the views of an individual are likely to change’.[92]

‘There are always leeways of choice’.[93]

Sir Anthony Mason, like a majority of the High Court’s justices since 1903, came from the stable of the successful NSW Bar and Bench. He was appointed to the High Court in 1972 on the death of Sir William Owen, having previously served on the NSW Court of Appeal from 1969. His position as Commonwealth Solicitor-General from 1964, after its refashioning by Sir Garfield Barwick when Attorney-General, is a distinctive characteristic of his professional career and one which will have provided unique insights into constitutional litigation in particular.[94] Mason was both successful and well-connected in the law, for example, having served as Barwick’s ‘favourite junior’.[95] In an interview for publication in the Singapore Law Review, Mason identified some key influences on his professional life and approach to the law. These he identified as his mother in terms of his professional direction,[96] and Sir Owen Dixon[97] and Lord Wilberforce in terms of his admiration for their intellectual approach to the law.[98] In fact, Mason actually declines to identify any lawyer who has particularly ‘influenced’ him beyond respect and admiration.[99] He has commented on the patterns of disagreement with senior members of the bench in his early period as a Justice, which suggests an independence of mind which can be traced throughout his judicial career.[100]

By the time of his retirement in 1995 Mason had served almost a quarter of a century on Australia’s highest court. In view of the length and quality of his contributions to the Court it is perhaps surprising that no full biographical treatment of his professional career has yet been produced.[101] Thus in an important sense, the active, nonagenarian Mason currently serves as both the custodian of and ongoing contributor to his own judicial legacy.[102] Since his retirement Mason has been in demand as a keynote speaker at university and professional conferences, a contributor to academic journals and other published collections, and as a media interviewee and constitutional commentator. This is a demand to which he has acceded with great regularity and there is little current sign of its cessation. Despite this regular public exposure there is much in Mason’s jurisprudential philosophy[103] and more general character which remains enigmatic to the external observer.[104]

Even in the absence of a judicial biography, Mason’s pivotal role in the High Court’s developing jurisprudence in the 1980s and 1990s and his contribution as Chief Justice has elicited regular media and academic commentary and critique.[105] Mason himself has recently reflected on the High Court under his leadership and identified a number of factors contributing to its particular jurisprudential and collegial dynamics. These include the controversial nature of the issues to be determined by the Court, the ‘lack of consensus as to the role of the Court, as for example, in departing from precedent ... another was the existence of deep-seated divisions within the Court’ over core approaches to key legal and constitutional issues.[106] Mason also notes that the personality dynamics ‘vary considerably and can change dramatically in an enclosed community like the High Court’.[107] However, in the same context he also maintains that ‘every Justice has a responsibility to endeavour to establish a working relationship with colleagues’.[108]

When investigating Mason’s leadership as Chief Justice, and in the absence of a full biographical treatment of his career, it is currently challenging to separate his jurisprudential[109] and extra-curial leadership, so entwined do these ultimately appear. Indeed, the content of Mason’s extra-curial interviews during his Chief Justiceship and since has regularly traversed the method[110] and outcomes[111] in high profile cases. Another feature which complicates the process of assessing the dimensions of leadership during this period is the undoubted depth and breadth of societal change[112] to which the Court was drawn to respond.[113] In this heady environment, the High Court acknowledged the need for a more concerted effort by the institution in explaining its role and its work. A product of this realisation was Mason’s innovative and unprecedented strategy in explaining the work of the High Court to the public in the print and televised media.[114] The need for the Court to engage with the education of the public about its role was acknowledged frankly and unequivocally by Mason in his inaugural interview on ABC’s Four Corners in 1995, a mere three weeks before his retirement.[115] Arguably, this acknowledgement and subsequent action under Mason radically changed the extra-curial sphere for the Chief Justice and perhaps for Australian courts more broadly. However, in the decision to be interviewed as its leader on the work of the Court, the line between the jurisprudential and the extra-curial once again becomes blurred.

This novel extra-curial work by Mason in engaging with the media has been complemented by a quite different extra-curial commitment in the form of hundreds of speeches, addresses and papers in diverse legal and non-legal contexts. These include speeches at law schools, universities, legal professional bodies, judicial organisations, as well as community groups, notably the Corowa District Historical Society at its annual federation dinner. As Chief Justice, Mason travelled far and wide throughout Australia and overseas, addressing issues of significance associated with the processes by which law develops, the administration of justice and the role and function of the judiciary in a democratic state. A distinctive characteristic of his extra-curial output is not just its quantity and variety, but the fact that so much of it appears in legal periodicals of various types, including university law reviews. Lindell in his survey of Mason’s extra-curial writing identifies 36 contributions to books and 160 published in periodicals.[116] Superficially, these figures might more readily be associated with a distinguished legal scholar in the academy rather than a Chief Justice of a nation’s highest court. In his extensive more scholarly extra-curial output, Sir Anthony Mason is unique amongst Chief Justices in our sample. There is much work to be done in this current generation of scholars to identify how this extensive corpus of publications has contributed to a changing understanding of the dynamics of a Chief Justice’s leadership role. Ironically, although Mason has undoubtedly made a very significant contribution to the work of the High Court, presiding over an intellectually ebullient court, his own conception of the role of Chief Justice is still arguably incompletely understood.

‘He was a great judge and an inspirational leader’.[117]

‘[T]he mutual respect that ... all of us had, one for the other ... was ... one of the remarkable features of a Court which was ... constituted by a wonderful group of people’.[118]

Sir Gerard Brennan, the third Chief Justice of the High Court from Queensland, had the distinction of being the first appointment to the High Court from the Federal Court, which had been established in 1976 to relieve an overburdened High Court. Like Sir Anthony Mason before him, Sir Gerard was appointed as Chief Justice from the position of Senior Puisne Judge, in his case in 1995 by the Keating Government. At the time of his appointment as Chief Justice he was 67 years old and was required by section 72 of the Constitution to retire on his 70th birthday. It might be thought that such a short tenure as Chief Justice might preclude meaningful analysis of his leadership. However, there can be little doubt that Brennan brought a powerful and unique presence to the Court in these years,[119] building on his history of collegiality amongst judicial colleagues.[120] Brennan’s professional persona, more than that of any other Chief Justice considered in this article, is characterised by three interlocking commitments: relationship;[121] vocation;[122] and values.[123] He is motivated both personally and professionally by considerations which are both broad and deep, by a concern for both persons and institutional integrity. There is also evidence of the high personal esteem in which he was held by his colleagues in various courts as is reflected in an extract from Daryl Davies’ tribute, quoted at the commencement of this section.

Sir Gerard’s extra-curial writing, which is strongly marked by the themes of vocation, relationship and values, is often disarming in its modesty and self-deprecation. For example, he has often shared stories of his earliest, inept experiences in the law as his father’s associate,[124] Justice Brennan senior having served a lengthy term as the Central Judge of the Queensland Supreme Court based in Rockhampton.[125] He has judged his own university career as modest,[126] and this rather severe personal assessment does not hint at his fundamental intellectual interest in the law as an institution,[127] nor does it allude to his belief that independence of mind is an essential professional quality in the law.[128] His extra-curial contributions during his time as Chief Justice are far from groundbreaking in their intellectual content or themes. However, they clearly evince his deeply-held belief in the centrality of the rule of law to the health of civil society and the critical role of the judicial arm of government as its guardian. His contribution to the Mason Court and Beyond Conference in 1995 honoured his predecessor in Brennan’s core spirit of collegiality and relationship.[129] His speech at the 20th Anniversary of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal in 1996 acknowledged his role in establishing an important legal institution and the work of its members, his colleagues. His speeches in the 1990s at two of the new generation of law schools – Deakin and Newcastle – allowed him to speak on broad values-driven themes – judicial independence[130] and the role of the judicial branch of government.[131] On these occasions it was not only his well-chosen words which impressed, but the warmth of his human presence, and his interest in the life and work of the staff and students whom he met.[132]

Like Chief Justices before him, controversy surfaced during Brennan’s period as Chief Justice. Unlike Gibbs, it did not primarily concern the internal dynamics of the Court, but a vexed question of the traditional role of the Commonwealth Attorney-General as a defender of the Court against ill-founded criticism of its work. Brennan subscribed to this established position[133] whilst the Attorney-General of the day, Daryl Williams QC, did not. This created a frosty tension between the two which was exacerbated by (incorrect) public comments by the then Deputy Prime Minister that the High Court had deliberately delayed handing down its judgment in the Wik decision.[134] In the absence of public support from the executive branch of government, Brennan participated in a lengthy interview for the ABC current affairs program Lateline. The interview was aired on 22 May 1998, shortly before Brennan’s retirement.[135] The interview in which Brennan reprises some perennial themes with clarity, equanimity and calm, is interspersed with footage of public interactions between the Chief Justice and Attorney-General in which their chilly relationship is not in doubt. Brennan confirms the challenge for judges of deciding matters ‘in the lonely room of his or her own conscience’. He is implacable in his assessment that ‘[t]he Court will not be moved by criticism no matter how intemperate it may be nor how strong it may be’. He argues for ‘the respect that each branch of government must have for the other’ lest ‘public confidence in the institutions of government and the constitutional institutions is diminished’. He also identifies ‘informed ... criticism’ as ‘the very soul of continuing justice’.

In his Lateline interview in 1998, and also in the documentary film The Highest Court[136] released in the same year, Brennan emerges as a leader of strong ethical stature.[137] In The Highest Court, a documentary which explains the history, role, and procedure of the High Court, the director managed to negotiate access not just to the Chief Justice but to four other justices for the purpose of explaining and commenting upon the day to day work of justices in the ‘rarefied atmosphere’ of the Court.[138] Justices Toohey, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne all contribute to the discussion of the lives and work of the one of Australia’s most powerful but least known or understood institutions. Brennan’s leadership in this round table discussion is unobtrusive, collegial and cordial. The friendly banter amongst the Justices suggests that the Brennan Court operated in a cohesive professional environment. This picture is complemented by Brennan’s often repeated description of the collegial lunchtime peregrinations of four Justices around the Parliamentary Triangle.[139] In one of these retellings he names the four Justices: Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and himself.[140] Nothing could be more emblematic of the Court over which Brennan sought to preside than this collegial picture.

‘The Smiler’.[141]

‘The fact that you have a nickname doesn’t mean you’ve earned it. That just happened’.[142]

Murray Gleeson, having previously served ten years as Chief Justice of the NSW Supreme Court, was appointed as Chief Justice of the High Court in 1998 by the Howard Government upon the retirement of Sir Gerard Brennan. According to Gleeson’s biographer, ‘[f]rom day one the focus was on Gleeson.’[143] In conservative political circles, he was seen as ‘the new Barwick’,[144] although it was readily acknowledged that Gleeson had never moved actively in political circles in the way Barwick or Murphy had. On the eve of his retirement, and like others before him, Gleeson was clear in rejecting the identification of eras of the High Court as ‘activist’ or ‘conservative’. He regarded such labelling as ‘an oversimplification’.[145] In reflecting on his term as Chief Justice and the leadership he had exercised during his decade at the helm, it is possible to see his actions, both curial[146] and extra-curial, as purposeful. As an able lawyer of introverted temperament[147] and largely uninterested in self-promotion, he had no egocentric reason for extending the extra-curial activities of his role. When he made speeches their function was educative[148] and one theme dominated above all others: the rule of law. The choice and reprise of this leitmotif had a serious purpose, namely as an effort to redraw the institutional boundaries of the Court’s role in the wake of the Mason and Brennan eras. There is an immediacy and drive in Gleeson’s extra-curial output and little evidence that he was concerned to ensure that his speeches found their way into the pages of law journals. His primary role as Chief Justice was not intellectual[149] but practical, to steer the institution back into the more pacific waters of traditional legal methodology. This is abundantly evident from the early period in his speech to the Australian Bar Association Conference in New York in 2000. In the wake of this speech, his captive audience of legal professionals can have been in no doubt about the legal philosophical commitment of the Chief Justice:

The quality which sustains judicial legitimacy is not bravery, or creativity, but fidelity. That is the essence of what the law requires of any person in a fiduciary capacity, and it is the essence of what the community is entitled to expect of judges. There is often room for disagreement amongst lawyers and judges as to what the law requires, but the terms of the trust upon which judges are invested with authority set the boundaries within which the contest must be conducted. In the case of the resolution of federal issues, it is fidelity to the Constitution, and to the techniques of legal methodology, which is the hallmark of legitimacy.[150]

The most distinctive aspect of Gleeson’s extra-curial work is without doubt his Boyer Lectures delivered on ABC radio in 2000. Gleeson is the only Chief Justice of the High Court ever to have delivered the Boyer Lectures.[151] His lectures were delivered on the theme ‘The Rule of Law and the Constitution’. If Gleeson had hopes of engaging with the profession and members of the public more broadly about key institutional concerns associated with the High Court through the vehicle of the Boyer lectures, it is perhaps surprising that he should have chosen public radio as his medium. However, it is notable that Gleeson agreed to be interviewed on radio both in 2007 and before his retirement in 2008 on ABC Radio National’s Law Report at a time when he might have sought out interviews on television as had his predecessors in the role.

‘[A] life in the law is about the law and much besides. It is more than logic and principle and argument. It is informed by a vital human dimension’.[152]

‘[H]e has mostly kept a low profile as chief. He put a media ban on himself in 2013, doesn’t bother distributing his speeches and rarely says anything that might engage the wider public’.[153]

The era of the 12th Chief Justice of the High Court concluded with his retirement on 29 January 2017 after nine years in the role.[154] In a number of respects French’s appointment has broken new ground for the Chief Justiceship and the consequences for future patterns of appointment are not yet clear. French is the first Chief Justice appointed directly from the Federal Court of Australia although in recent years an increasing numbers of High Court justices have been appointed from this court. The Federal Court was established in 1976 and unlike State and Territory courts from which High Court Justices have been selected historically, its jurisdiction is statutory. Typically, its justices would be exposed to a more limited range of legal matters in comparison with their State counterparts. Furthermore, apart from his work on the National Native Title Tribunal, French had no experience as a judicial officer beyond the Federal Court itself. In contrast, other appointees to the High Court from the Federal Court had served on State Supreme Courts prior to that appointment.[155] During the period of French’s Chief Justiceship, fully half of the appointments to the High Court were from the ranks of justices of the Federal Court.[156] The significance of the appointment of an increasing number of justices from this very different curial environment has not yet been the subject of detailed analysis and critique. The differences that such appointments may bring to the practice and jurisprudence of Australia’s apex court are currently a matter for interested speculation only.

Appointments to the High Court have not been evenly distributed amongst the States in the Federation and French was the first Chief Justice and only the third appointment to the Court from the state of Western Australia. Further, he was the first justice with a legal specialisation in native title law, having served as the inaugural President of the National Native Title Tribunal from 1994 to 1998. Of significance to his leadership role on the High Court is the fact that French is probably the first Chief Justice in the history of the Court whose intellectual formation has been in the sciences rather than in the humane disciplines. French completed a degree in physics before embarking on the study of law.[157] This educational background is likely to have an ongoing influence on his approach to the legal system and the operation of legal institutions.[158]

In analysing his extra-curial output, French’s approach emerges as exemplifying a commitment to modernity and empiricism. His modern, more ahistorical,[159] approach to the role of the High Court as an institution and its work in the contemporary environment can be seen clearly in his view that:

[t]he High Court of Australia is not a museum of the law and of great judges and chief justices of the past. It is a living, working and inescapably human institution. ... But the challenges that face us in this very contemporary institution are not the challenges of the past. They are the challenges of the time and they are different for our generation as they are different for every generation.[160]

For Chief Justices of earlier generations, the historical work of the Court was the foundation for current practice, and the challenges faced by succeeding generations of justices carried a timeless and unchanging quality: the need to do justice according to law without fear or favour, affection or ill-will. Chief Justice French’s identification of the centrality of the ‘human dimension of the law’ to the High Court’s work has led also to his endorsement of another powerful, contemporary concept – diversity:[161]

Within the limits of the judicial discipline there is room, as there must be, for judicial diversity. The institutions of the law are human and so long as they are, diversity is inescapable.[162]

These views expressed by French as Chief Justice arguably represent a break with the previous tradition of extra-curial engagement on the Court, which was largely formulated within an intellectual frame of reference deriving from more positivist and natural law roots. It is yet too early to assess how far this signals a fundamental change to the role of Chief Justice or shift in leadership practice.

Although the jurisprudence of the French Court is not our primary interest in this article, it would be remiss not to note the unusually high proportion of unanimous decisions of the High Court in the first years of French’s tenure. During the 2009 term of the Court, an unprecedented 44 per cent of cases heard by the High Court were decided without a dissenting judgment.[163] In 2010 this figure increased to 50 per cent.[164] However, from 2011 this early pattern of unanimity was broken with a significant drop in unanimous decisions to around 17 per cent, a pattern which was to continue thereafter.[165] French has commented on the changing dynamics caused by departures and arrivals on the Court during his tenure in a speech launching the essay collection, The High Court, the Constitution and Australian Politics in 2015:

While it is flattering to have a chapter entitled ‘the French Court’, since I was appointed Chief Justice in 2008 there have been four departures and corresponding new appointments. The fifth will occur in June this year. After Justice Hayne retires the only Justice of the High Court remaining on the Court from the date of my appointment will be Justice Susan Kiefel. Every new appointment means the withdrawal of one person and the introduction of another. That is not just one change, it is two and as one might expect these changes can lead to the development of a new dynamic within the Court. In a sense there will have been five different High Courts between my appointment and retirement between 2008 and 2017.[166]

These changes in personnel are sufficient to account for the changing patterns of concurrence and dissent without greater attention here to an assessment of French’s leadership style or the differences in jurisprudential approaches amongst particular members of the Court.

Turning to French’s extra-curial output, it is most notable in its volume. Over nine years he delivered 142 speeches in a range of contexts from legal conferences, university named lectures, annual dinner speeches, legal professional gatherings and anniversary events throughout Australia. This rate of engagement with the profession, universities and the community more generally is without doubt greater than any of his predecessors. In contrast with the substantial output of Sir Anthony Mason in his day, French has shown little interest in securing the publication of his speeches in journals, periodicals or professional publications. His regular practice in making speeches to a great diversity of groups suggests an interest at odds with the assessment by Michael Pelly of his time as Chief Justice quoted at the beginning of this section. In accord with French’s modernist outlook his speeches have strong narrative[167] and biographical[168] elements which make them accessible to wide audiences[169] and reinforce the human dimension[170] which he has stated is so significant to a life in the law.[171] It is arguable that these approaches contribute de facto to a new configuring of the persona of the Chief Justice, one which lacks the full measure of gravitas and mystique associated with the role in earlier times. In his recent David Malcolm Annual Memorial Lecture, Chief Justice French provided a definition of sorts for ‘modern judicial leadership’, which he says is:

a multi-dimensional concept reflecting the character of our courts and their relations with the other branches of Government. They are not temples from which oracles dispense the law in more or less Delphic language. They are distinctive and distinct institutions of government, each engaged fully with the community which it serves.[172]

Such a definition certainly reflects his own approach in the extra-curial realm.

In Part III above, we explicated our fourfold schema of extra-curial leadership arising from an inductive analysis of the evidence of extra-curial practice on the High Court, namely extra-curial leadership which is intellectual, institutional, collaborative or individualist in character. In linking our categories and analysis of the extra-curial practices of Chief Justices with the theoretical parameters identified for judicial leadership by Danelski, as discussed above in Part II, we would argue that our notion of intellectual leadership has a corollary in Danelski’s concept of ‘task leadership’, although it is likely to be exercised in a distinctly different fashion in extra-curial circumstances. The extra-curial intellectual leader will take the opportunity to speak and publish about matters of substantive law which do not derive their impetus from the cases before the High Court at any given time. The most conspicuous example of this in our sample is Sir Anthony Mason.

Species of institutional leadership in our spectrum of extra-curial leadership are not directly related to the decisions in immediate cases before the court (Danelski’s ‘task leadership’), but reflect the necessity that a Chief Justice is intimately concerned with the administrative functioning of the court as an institution.[173] Some Chief Justices, by temperament and personal inclination, devote more energy and time to the administrative institutional role. In our sample Sir Garfield Barwick stands out in this category. The leadership associated with these activities may have a significant effect on other Justices, as well as other staff employed by the court. We see this category of ours as more closely aligned with Cornes’ third category of ‘constitutional guardian and statesperson’,[174] especially in its manifestation of ‘speaking and writing out of court’[175] rather than finding a natural fit with either of Danelski’s categories.

Our categories of ‘collaborative’ and ‘individualist’ extra-curial leadership represent a diversity of responses to the challenge of what Danelski identifies as ‘social leadership’. ‘Individualist’ extra-curial leadership in our schema recognises the emergence in a Chief Justice of distinctive (and even robust) personality traits. In a sense when we identify ‘individualist leadership’ we may be talking about a reaction against the challenges of social leadership on the part of certain personality types. Danelski identifies the qualities of the social leader in deciding cases as tending to be ‘warm, receptive and responsive’ and amongst the best liked members of the court.[176] Where these qualities required for successful social leadership are not present in an individual leader, the tendency on their part may be in the extra-curial realm to assert a form of rugged individualism.

Amongst the Chief Justices in our sample Barwick, Mason and Gleeson all display elements of individualist leadership. Each has a professional career marked by a strong concern for personal achievement. Whilst the drive for personal success and professional excellence is not synonymous with a leadership style directly, we would suggest that it is relevant in some respects to the performance of leadership roles by individuals. Both Barwick and Gleeson identified a special and superior role for the Chief Justiceship beyond its status as primus inter pares.[177] Barwick’s leadership practice could be characterised as a rule by memorandum[178] which provides insight into its flavour. In his earliest days on the Court, Gleeson’s view that the Chief Justice was more important than other Justices was strongly challenged by Justice Gaudron: ‘You’re no longer in NSW. ... It’s not first among equals. We are all equal’.[179] We would identify Mason’s leadership style as highly individualist, whilst at the same time conceding that he is for us the most enigmatic figure to have led the Court in the last fifty years. Our identification of Mason as an individualist leader is strongly influenced by the corpus of his extra-curial writing, consisting of an abundant sequence of papers and publications individually crafted and launched on the world.

Without doubt Sir Garfield Barwick was the most institutionally focussed of the Chief Justices, which may relate directly to his background in the executive government. Barwick was centrally concerned with the prestige and standing of the High Court as an institution of government alongside the two political branches and this is illustrated clearly in his drive and determination to secure a permanent home for the Court in Canberra.[180] Gleeson, too, arguably took an institutional focus for his leadership but in a distinctive fashion. We would characterise his leadership as founded in a commitment to the rule of law

as a key touchstone for both the institutional credibility of the Court and

its operational efficacy.[181] Gibbs in a sense also displayed elements of an institutional leadership style. He had been a member of the Court for a long time before being elevated to the Chief Justiceship and from this position was thoroughly familiar with the changing personal dynamics of the institution. His commitment to upholding the institutional integrity of the High Court was challenged considerably in relation to the Murphy affair.[182] We would also see the institutional dimension of Gibbs’ leadership as influenced fundamentally by the fact of his modelling of his judicial persona on Griffith rather than Dixon, and as a consequence his conception of the role of the High Court as an essential mediator in relation to the federal compact.[183]

In terms of collaborative leadership style, Brennan is the exemplar.[184] The clear and unequivocal message from his extra-curial activity in all its variety is his objective at every instance to promote the existence of strong collegial relations on the court. This is well-illustrated in his often quoted description of the lunchtime perambulations of a majority of the Court’s members during sittings in Canberra,[185] and in his collegial approach to the roundtable discussions of the Court’s work in the Highest Court documentary.[186] Gibbs’ natural interest in people led to a more collaborative approach to leadership of the Court as a reaction against some of the characteristics of the Barwick era. The circumstances of the Murphy Affair and the attendant challenges to the Court’s institutional integrity also invited a more collaborative style of leadership.[187]

In the history of the Court, intellectual leadership in its fullest sense has fallen to very few. There can be little doubt that the long shadow cast by the entrenched view of the intellectual/jurisprudential dominance of Sir Owen Dixon in his 35 years on the bench, particularly during his time as Chief Justice, has cast something of a pall over the assessment of the intellectual leadership of his successors. In the 50 years encompassing our research initiative the contributions made in terms of intellectual jurisprudential leadership arguably do not equal Dixon’s. However, in the extra-curial realm, it is arguable that Sir Anthony Mason has surpassed Dixon whom Mason himself has acknowledged as one of his judicial influences.[188] As the guardian of the legacy of the Mason Court,

Sir Anthony has been a robust and consistent defender of its decisions

and methodology both in print and in broadcast interviews.[189] The gatekeeping function which he has adopted since retirement has both institutional and intellectual dimensions. However, the pattern and vigour of Mason’s continued engagement with the legal system and the work of courts since retirement is diametrically opposed to Dixon’s own practice. As has been the case with other retired High Court Justices, notably Sir William Deane in recent times, Sir Owen Dixon showed no continuing interest in the law in any respect after his retirement from the High Court in 1964. In fact, he turned his face from the law back to the world of classical literature, his first love.[190] This is very far from Mason’s ongoing active engagement with a variety of dimensions of the law including legal education,[191] legal research[192] and broader legal professional concerns.[193] He is still a sought-after speaker at legal events nationally and is generous with his time and experience. As such he provides a powerful model of extra-curial leadership both during his time as a sitting Justice and beyond the confines of tenure on the High Court.

Turning to the question of intellectual leadership of other Chief Justices, it is important to reiterate that Sir Harry Gibbs came to the Court with a mature jurisprudential philosophy.[194] During his Chief Justiceship he might be seen to have forged a jurisprudential leadership of dissent in his consistent application of federalist philosophy in some of the most significant constitutional cases of the day.[195] Like Mason, Gibbs continued to contribute in the extra-curial realm after retirement, most notably in the context of the Samuel Griffith Society,[196] at times facilitating the participation of others, such as his presentation of a paper by the elderly, blind Sir Garfield Barwick at the Society’s conference in 1995.[197] Such ongoing contributions by retired High Court justices have been facilitated in recent decades by their longevity, good health and mental acuity, as well as the introduction of a constitutionally-mandated retirement age for High Court justices in 1977. Sir Anthony Mason has noted that a characteristic of some, but not all, High Court judges is their genuine interest in the law itself.[198] Such personalities are likely to take opportunities to contribute to contemporary debates about law and the legal system.

Gleeson’s practice of ‘speak[ing] in his own voice’[199] in concurring majority judgments to explain the more complex jurisprudence of his colleagues demonstrates another, perhaps lesser, manifestation of the jurisprudential leadership role. In fact this might be better characterised as an interpretive dimension of leadership for a Chief Justice rather than a sub-class of intellectual. His contribution in the extra-curial role is consistent and largely monothematic, most notably in his presentation of the Boyer lectures.[200] Brennan’s contribution to High Court jurisprudence during his 17 years on the Court is a worthy subject for more detailed exploration and it can only be hoped that a ready biographer might be found in the near future to undertake this important task. However, Brennan’s Chief Justiceship was short and in some respects seems broadly to reflect the continued intellectual momentum of the Mason years but with tempering in judicial approaches on some issues.[201] However, in terms of extra-curial leadership, Brennan’s term is most clearly characterised in terms of collaboration and collegiality. These more social concerns emerging during Brennan’s tenure speak significantly to his personal character.[202] From an early dominance of unanimity in cases decided by the French Court, the pattern over time became more diffuse. This may reflect in part French’s commitment to diversity in judicial approaches within the broad parameters of judicial method. We have previously made a case for the significance of the intellectual independence of both Justices Heydon and Gageler, both members of the French High Court.[203] French’s extra-curial contribution during his time in office is significant both in its breadth and its volume. His many speeches in the great variety of contexts in which they were made neatly highlight core leadership qualities identified by Chief Justices in 2006, and in particular, ‘developing a sense of the institution, a collective commitment to justice, and communicating this throughout the court and to the public’.[204]

In this article we have explored dimensions of the leadership practices of the most recent six Chief Justices of the High Court from the appointment of Sir Garfield Barwick until the retirement of Robert French in January 2017. A consideration of the theory and literature of judicial leadership since its inception in the 1960s has facilitated our own inductive process of analysing the extra-curial leadership practices of our sample. This is complemented by a discussion of the relevant contexts within which each Chief Justice exercised his particular leadership qualities. The novelty we would claim for our work lies in the combination of our focus on extra-curial activities as an arena within which leadership may be exercised by a Chief Justice, the promulgation of our fourfold schema of extra-curial leadership characteristics arising from our analysis of extra-curial activity by Chief Justices over 50 years and the utilisation in our research of some less traditional sources, particularly interviews conducted for the broadcast media. This combination of approaches potentially opens up for the future some new questions and qualitative research approaches for scholars of judicial leadership and legal biography more broadly.

[*] MA, LLB (Qld), LLM (Newc). Senior Lecturer in Law, Newcastle Law School.

[**] BCom, LLB (Hons) (Western Sydney), LLM (Trier), BCL, DPhil (Oxon). Lecturer in Law, Newcastle Law School.

The authors would like to thank participants in the 2016 Society of Legal Scholars conference in Oxford for comments on an earlier draft and the anonymous reviewers of this article for their comments and suggestions.

[1] See, eg, Jason L Pierce, Inside the Mason Court Revolution: The High Court of Australia Transformed (Carolina Academic Press, 2006); Mark Tushnet, ‘Judicial Leadership’ in John Kane, Haig Patapan and Paul ‘t Hart (eds), Dispersed Democratic Leadership: Origins, Dynamics, and Implications (Oxford, 2009) 141; Alan Paterson, Final Judgment: The Last Law Lords and the Supreme Court (Hart Publishing, 2013).

[2] Nancy Maveety, ‘The Study of Judicial Behavior and the Discipline of Political Science’ in Nancy Maveety (ed), The Pioneers of Judicial Behavior (University of Michigan Press, 2003) 1.

[3] Ibid 30.

[4] David J Danelski, ‘The Influence of the Chief Justice in the Decisional Process’ in Walter F Murphy and C Herman Pritchett (eds), Courts, Judges and Politics: An Introduction to the Judicial Process (Random House, 1961) 497.