University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE INNOVATIVE MAGISTRATE AND LEGITIMACY: LESSONS FOR A MOBILE ‘SOLUTION-FOCUSED’ MODEL

SARAH MURRAY,[*] TAMARA TULICH[**] AND HARRY BLAGG[***]

I think the innovation that we’re seeing now is a result of judges processing cases like a vegetable factory. Instead of cans of peas, you’ve got cases. You just move ’em, move ’em, move ’em. One of my colleagues on the bench said: ‘You know, I feel like I work for McJustice: we sure aren’t good for you, but we are fast’.[1]

Australian magistrates face many challenges in their work: heaving courtrooms, unrelenting court lists and cases involving a complex web of legally-knotted psychosocial issues. Innovative practices by a magistrate – creative ways of engaging with defendants, partnering with support services, and novel sentencing methods – can become essential for courtroom survival. Such methods may represent a challenge to the legitimacy, expectations and traditional practice of the wider court of which that magistrate forms a part.[2] However, a failure to seek new solutions can risk the court losing its relevancy.

The legitimacy/reform tussle is a challenge that all courts must face. This article focuses on the legitimacy question of a magistrate spearheading novel approaches – whether on circuit, as part of a specialist court or as one magistrate within a multi-member jurisdiction. Using a range of case examples, this article unpacks how innovation can occur in this context and suggests that innovation, while representing a challenge to a magistrate’s legitimacy, can also become the fuel generating legitimacy for the magistrate and the court which they serve. The article uses these understandings to sketch out lessons for future innovation including for a mobile ‘solution-focused’ justice model.

There’s the stresses of knowing that there’s nothing you can do to help ... you know from the social side of things that you can’t help; there’s housing difficulties, there’s welfare difficulties, there’s employment difficulties, all of which may assist them to stop offending but it’s impossible to address. So there’s the frustration of ‘I know what I want to do but we can’t do it’ and until this changes nothing’s going to change for this child, and I think anybody who is interested in their work so that it means something to them can’t but help feel those stresses on them.[3]

To be a court is to be constantly reforming and updating practice. Justice Gray observed, when he was Chief Magistrate of the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, ‘[t]here is nothing necessarily sacrosanct about the way the Courts have done their work in the past. Courts will continue to be expected to adjust their procedures and practices in the future’.[4] Research suggests that 44 per cent of magistrates surveyed in Australia rate ‘a desire to improve the court system’ as ‘important’ or ‘very important’ in attracting them to the magistracy.[5] Individual magistrates can become powerful agents of change in this context. The question is how the process of reform is manoeuvred and what this might mean for a court’s legitimacy.

What is the elusive concept of a court’s legitimacy?[6] Is it simply that a court is respected as an institution? That its decisions are obeyed and seen as binding? Is it a bundle of things that bring about ‘public trust’?[7] The concept of legitimacy has been much analysed, including by Weber[8] and Habermas.[9] Uncertainty surrounding the meaning of legitimacy has led some to question its ultimate worth as a concept.[10]

One of the prime difficulties with legitimacy as a concept is its multidimensionality. Legitimacy is said to be formed through a composite process with legal, sociological, political/institutional, and moral interplaying aspects.[11] The legal aspect relates to a decision’s legal coherence.[12] Political or institutional legitimacy denotes the acceptability or perceived appropriateness of a curially-assigned function or its exercise.[13] The morality dimension relates to the degree to which a court’s pronouncement or practice accords with moral principle.[14] The sociological aspect reflects the degree to which a court’s value and approaches resonate with the society or community. The difficulty is that, not only do these intersect and overlap, but even the sociological dimension can be further broken down into institutional, moral and more legal conceptions.[15]

Legitimacy can also be understood through an input/output analysis. Factors can be seen as ‘input’ based (institutional aspects of courts including their independence, selection, and remuneration arrangements) and ‘output’ based (the more socio-political aspects including a court’s relationships and interactions with those who appear before it but also wider governmental actors and the community at large).[16] Problematically, this linear input/output model can oversimplify this process. Designated ‘output’ aspects (eg, practices and experiences) can, in turn, feed into ‘inputs’ (eg, appointment/selection practices). The model therefore becomes circular.[17] However, the utility of legitimacy as a concept in the court context is less in unbundling it than in recognising legitimacy as a shifting, symbiotic process. A court’s legitimacy is best conceived as and through the nature of its relationships within and around the court – and, in particular, the trust imbued in these relationships.

Procedural justice plays a key role in these relationships, particularly in terms of relationships within the court. McEwen and Maiman, while noting the convolution of legitimacy theory and practice, recognise the role played by an individual’s ‘attitudes toward[s], and behavioural responses to’ decision-makers.[18] Conceptions of procedural justice provide that a range of factors shape the fairness and legitimacy assessment of a court. These factors include the degree to which a court allows litigants a ‘voice’ and engages them with the decision-making process, allows a relationship of trust to develop, provides for respectful engagement and a process that is perceived as ‘neutra[l]’.[19] For procedural justice, notions of trust, connection and respect for the process therefore become central building blocks for a court’s legitimacy.

As a court’s functions change, so do its external relationships and the community’s perceptions and expectations. While operating within a dynamic environment, the court participates in the creation, and re-creation, of its own legitimacy or perceived legitimacy. Courts ultimately want to preserve the integrity of the courts as an institution and are therefore conscious of retaining their impartiality, integrity and legitimacy quotients. Hence, they are aware of measures that could detract from these.

Legitimacy in reality, or in its perception, is mutable. Change within a court means an alteration to its wider ecosystem. Paradoxically, avoiding change and retaining a static curial approach can begin to compromise the institution just as much as reform can. The change process therefore needs to be delicately managed, consultative and respectful of the complex web of relationships in and around the court.[20] Research suggests that perceptions of legitimacy can reflect the degree to which the values or ‘interests’ of an institution are seen to mirror that of an individual community member, which highlights the need for courts to be attuned to and responsive to the needs and expectations of the wider society.[21]

There have been considerable reforms in recent years at the court level, from Aboriginal courts to new solution-focused courts (for mental health, drugs, homelessness and family violence to name a few)[22] and court-wide programs focused on self-representation, domestic violence and court support services.[23] Reforms at the Magistrates Court level can be centrally rolled out by the court or Justice Departments and can entail the mainstreaming of practices that have worked successfully in isolation.

While much court reform takes place centrally, it can be an expensive and logistically complex exercise. Change can also spring from seemingly small or inconsequential alterations in court practice which can attract momentum and become important adaptations. As former Magistrate Auty has noted:

It is increasingly recognized that some judicial officers and their courts appear to have a greater facility to moderate the operation of the Old Testament model of justice. This may be a function of the personality or philosophy of individual judicial officers, or of court staff being embedded in the local community and its concerns, or it may reflect a commitment to innovation in corrections departments. Change may also be sponsored by a combination of these or other factors.[24]

The magistrate is faced with the increasing demands on a modern magistrate and familiar with the needs and climate of their courtroom, innovation becomes a form of judicial subsistence. It also derives from key courtroom relationships. Depending on the court and its locale, a magistrate can develop crucial connections with support staff, justice personnel, Aboriginal Elders and the wider community. These affiliations can become vital catalysts for discrete legal reforms by individual justice personnel.

The unique challenges facing rural and remote magistrates present an excellent breeding ground for such innovation.[25] As King notes:

Regional courts may have only one full time judicial officer stationed at the court. In Western Australia, nine magistrates are resident in regional areas and an additional magistrate services some regional areas immediately south of the state capital of Perth. These ten magistrates cover an area not far short of a third of the continent of Australia. All regional magistrates have a circuit where they visit courts in outlying towns in their magisterial district. These magistrates have a great deal of autonomy in determining the procedure in the courts in their region.[26]

This autonomy can become the forerunner for experimentation within the magistracy. For example, Magistrate Steve Sharratt working across the Pilbara region in Western Australia, and with extensive discussion and community collaboration, helped set up the Yandeyarra circle court.[27] Similarly, South Australian Magistrate Chris Vass piloted a Nunga Court based on his experiences as a magistrate working on Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands. He explained:

I didn’t talk about it to the Chief Magistrate or the attorney-general’s office, or with any government agency. I thought that once I do that, they’ll form a committee, and nothing would happen. It was a matter of talking with Aboriginal people, listening to them.[28]

The Geraldton Alternative Sentencing Regime provides a similar example of a novel approach to regional court practice.[29] This Regime was designed to allow for a magistrate to work alongside an interdisciplinary team aligning its approach with the principles of therapeutic jurisprudence and the needs of offenders. While it was not supported through targeted funding, it was positively evaluated and became a model for innovative practice at the Magistrates Court level.[30]

However, there is always a risk that innovation in isolation can jeopardise the role and legitimacy of a magistrate. For instance, closer collaboration with allied services or a ‘treatment’ focus could be seen as an improper commingling of the legal with the non-legal, and it could be regarded as beyond a magistrate’s role to use the entry into court as a broader solution-focused opportunity for self-renewal. Similarly, a rural judge experimenting with novel sentencing practices may be perceived as too close to the community and lacking impartiality, as becoming too ‘soft’[31] and undermining his or her legitimacy. The next section examines how reform and innovation by the modern magistracy can augment or detract from the legitimacy of the institution more broadly.

How does a magistrate manage the process of reform? What factors can facilitate a magistrate embarking on innovation in a courtroom and what might work against it? Reform can cut both ways. A failure to respond to a clear need or recommendations might weaken the regard that is had for the court in just the same way as a failed reform. However, even small courtroom changes can alter the way that a court is perceived and the degree to which it is respected by the community. For example, Mack and Roach Anleu have suggested that less-adversarial and ‘engaged judging’ might hold real potential for ‘enhanc[ing] judicial authority’.[32] Drawing on the experiences of individual magistrates, this section examines the legitimacy implications of key aspects of innovative courtroom practice, to derive lessons for future innovation including for a mobile ‘solution-focused’ justice model.

The adoption of innovative practice, designed to meet the needs of the community serviced by a magistrate, can play a crucial role in enhancing legitimacy. In relation to Aboriginal Australians, local ‘innovative’ practices might range from the inclusion of community members in the courtroom, adaptations to courtroom set up and the inclusion of local Aboriginal art in the courtroom. For example, Magistrate Heath recounts the experience of Magistrate Steve Wilson in the Wiluna Court in the Mid West region of Western Australia:

Magistrate Steve Wilson noted the vast majority of accused appearing in the Wiluna Court were members of the local Aboriginal community. He, in cooperation with members of the local community invited senior members of the community to sit with him. He ceased the practice of sitting at the elevated bench and instead moved to a table in the body of the court. The tables are set out in a triangle formation with the accused at the apex, prosecution and defence counsel at the sides and the Magistrate and Elders at the base. He arranged for a number of Aboriginal paintings to decorate the courtroom. Although the Elders address the accused as to the impact of the offending on the community the sentencing is done by the Magistrate. Unfortunately a plan to develop a sentencing regime involving participation in a course of traditional skills and values run by Elders lapsed for want of funding.[33]

As this experience illustrates financial limitations can impede the ability of a magistrate to introduce the reforms they might otherwise like to.[34]

Innovative practice can be borne from the need to communicate the decisions of the court in appropriate language. At a conference[35] one magistrate was discussing her introduction to court work and how unprepared she was. She recounted reprimanding an offender for missing a hearing and her words: ‘if you are going to be late to the hairdresser, you call ... if you are going to miss your dental appointment, you let them know and ...’. At this point she was interrupted by a well-meaning Legal Aid lawyer, ‘Your Honour, with respect my client doesn’t go to the hairdresser or the dentist’. The magistrate described this encounter as an epiphany for her. She ended up paying a reformed offender to sit at the back of her courtroom to hold up ‘penalty cards’ if she needed to better explain her orders to defendants or allow him to rephrase for her (‘Her Honour is telling you to get off the gear’). New procedural justice methods such as these can enhance the respect of the judicial officer and the degree to which defendants feel heard by and involved with the court process. They also involve a recalibration of a magistrate’s relationships with court users and the community by imbuing trust and a consultative dialogue. This maintains legitimacy within the dynamic reform environment.[36]

This is not to say that the currency of legitimacy cannot be threatened by experimentation by the magistracy. Justice Hoffman, a District Court Judge in Colorado, writing extra-judicially, has lamented the influence of the therapeutic jurisprudence movement on judicial practice:

Defendants are ‘clients’; judges are a bizarre amalgam of untrained psychiatrists, parental figures, storytellers, and confessors; sentencing decisions are made off-the-record by a therapeutic team or by ‘community leaders’; and court proceedings are unabashed theater. Successful defendants – that is, defendants who demonstrate that they can navigate the re-education process and speak the therapeutic language – are ‘graduated’ from the system in festive ceremonies that typically include graduation cake, balloons, the distribution of mementos like pens, mugs, or T-shirts, parting speeches by the graduates and the judge, and often the pièce de résistance – a big hug from the judge.[37]

Objections such as these highlight concerns around the boundaries of the judicial role and legitimate judicial interactions. These concerns can be addressed by adopting evidence-based innovative practices – that is, by drawing upon the research basis for such approaches and acknowledging their possible limitations.

Specialist ‘solution-focused’ magistrates courts can present a similar opportunity for innovation. These have burgeoned considerably in the last decade and can allow magistrates to creatively address the entanglement of the law with particular societal problems such as drugs, homelessness, family violence or mental health issues. A good example of a magistrates court focused on a particular locality is the Neighbourhood Justice Centre (‘NJC’) based in Collingwood, Victoria which has been operating since 2007. The NJC houses a sole magistrate integrated with a wide range of interdisciplinary providers to create a form of ‘in-house’ holistic service provision.[38] This unique model has provided an excellent canvas for curial innovations under the guidance of Magistrate David Fanning, including the commissioning of street art to address problem graffiti,[39] integrating the work of the Court with a Crime Prevention and Community Engagement Team, and self and court referral to NJC service providers.

Many of these reforms have been influenced by therapeutic jurisprudence. Therapeutic jurisprudence is an approach focused on the potential for law to improve individual wellbeing to the extent that this is compatible with legal principle.[40] As Winick and Wexler explain, ‘therapeutic jurisprudence shed[s] light on how court structures and the conduct of individual judges can help people solve crucial life problems’.[41] Therapeutic jurisprudence has become an approach of considerable judicial and academic interest, but is part of a much broader move away from traditional judging and traditional lawyering. Non- or less-adversarial justice,[42] the vectors of the comprehensive law movement[43] or ‘new lawyering’[44] all reflect a shift towards law as a less-adversarial, less-detached and more healing-oriented profession.

Magistrate Michael King has been a pivotal driver for change, building on therapeutic and non-adversarial justice principles. Through conference papers, journal articles and a judicial bench book, Magistrate King has used his experience as a rural and metropolitan magistrate to showcase the potential for innovative practice. He has advocated a shift away from ‘problem-solving’ to ‘solution-focused’ judging, allowing for the court process to work alongside defendants to become a potential site for personal growth and renewal.[45] His work, initially in Geraldton, Western Australia, has influenced the development of a ‘Solutions Focused Sentencing Process’, now used by magistrates in other courts, including in Dandenong, Victoria.[46] This process involves a magistrate working collaboratively with an offender to develop a rehabilitation plan and future goals.[47] Magistrate Spencer has embraced this approach and describes how, ‘offenders often comment that this is the first time anyone has asked them what they need to do about their life’.[48]

The institution of courts focusing their energies on particular kinds of matters – drug courts, family violence courts, neighbourhood courts, circle sentencing courts, mental health courts – can give particular reforms in this setting more legitimacy not only through the benefit of perceived expertise, but also by fulfilling the need for this type of curial method to address particular problems. It can also potentially be easier for change to be implemented in such contexts.

For example, at the Collingwood NJC, Magistrate David Fanning, through a process of consultation with Aboriginal Elders, was pivotal in introducing Hearing Days for Aboriginal people at which additional supports and services are also made available.[49] Further, he and the NJC staff have sought to develop an extensive array of support services, well above those initially funded to be

based within the Collingwood NJC building.[50] It is the ‘accretion of positive experiences’ with a centre such as this that can ultimately fuel legitimacy in the workings of the Court and the Centre as a whole.[51] Innovation in the NJC is facilitated by the fact that the model has the express legislative support of Part 2 of the Magistrates’ Court Act 1989 (Vic). The Neighbourhood Justice Court, which sits within the wider Centre, is the ‘Neighbourhood Justice Division’ of the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria (alongside the Family Violence Court, Koori Court and Drug Court Divisions). The Act specifically contemplates novel court procedures by the terms of section 4M and sentencing within the Division (under section 4Q) allows for the magistrate to be informed by a wide range of agencies, service providers or other individuals. The Act (in section 4M(5)(a)) also contemplates that the appointment process for the magistrate for the Division is to have reference to candidates’ ‘knowledge or, or experience in the application of, the principles of therapeutic jurisprudence and restorative justice’, giving weight to the use of such processes but also the magistrate’s expertise to administer them.

This is not to say that such courts undertaking reform are immune from criticism. Justice Heydon of the High Court of Australia, in the case of Kirk v Industrial Court of New South Wales, was critical of what he termed ‘specialist courts’ which can ‘become over-enthusiastic about vindicating the purposes for which they were set up’[52] and can ‘develop distorted positions’ as a result.[53] Once again this raises questions around the legitimacy of court reforms and the societal expectations placed upon them. It also highlights the significance of the emphasis, in procedural justice scholarship, on the importance of there being ‘trust in ... [the] benevolence’ of decision-makers as well as the importance of neutral and respectful processes.[54]

While Freiberg has been keen to point out that ‘specialist courts’ as a label applies to a much broader array of courts than ‘problem-oriented courts’,[55] there are potential legitimacy challenges associated with the co-location of particular types of cases. Such court models can be resource intensive and reforms in problem-oriented contexts can be required to ‘prove their worth’ to a greater extent. Further, even when they succeed, innovative magistrates may be criticised for creating separate justice systems or solutions for certain sections of the community, options which mainstream courts lack due to funding.[56] Indeed, Freiberg reports that ‘[a] very common complaint from “traditional” or mainstream court and correctional authorities is that given the same level of resources, they could achieve the same results’.[57] Magistrate Fanning responds to criticisms that the NJC is simply a ‘Rolls Royce’ success story by explaining that many of the services it partners with are not necessarily funded by the justice system but instead are on-site for the mutual benefits ‘co-location’ brings.[58]

In November 2004, Western Australian country magistrates resolved at their annual conference to subscribe to the principles of therapeutic jurisprudence. They declared that magistrates would:

seek a more comprehensive resolution of legal problems coming before the court for the greater benefit of litigants and the communities served by the court. ... In using therapeutic jurisprudence, the magistrates seek to use the authority and standing of the court to minimise any negative effect of court processes and, as far as possible, to promote the wellbeing of those affected by court processes be they victim of crime, defendant, other party to court proceedings, witness, counsel or court staff.[59]

The 2004 Country Magistrates’ Resolution was an explicit recognition of the court identifying its practice with the approach of therapeutic jurisprudence. The Resolution, however, did not stop there. It recognised explicit limits on the ability of magistrates to decide cases therapeutically. First, therapeutic jurisprudence must be implemented ‘within the context of statute and the common law’, and hence can ultimately be trumped by legal requirements if need be and can be achieved ‘consistent[ly] with traditional judicial principles such as independence, impartiality, fairness and integrity’.[60] Second, magistrates were required to ‘consult with local stakeholders and to meaningfully include professionals from other disciplines’.[61] Third, magistrates experimenting with more holistic practice should ‘consult with each other in relation to therapeutic jurisprudence related projects’ to ensure ‘that best practice may be promoted’.[62] Fourth, the Resolution recognised that no magistrate is an island and that ‘[c]ountry magistrates, court stakeholders and relevant local agencies should be included in the design and implementation of therapeutic jurisprudence related projects in their courts’.[63]

This Resolution was significant for a number of reasons. As Deputy Chief Magistrate Cannon of South Australia has explained: ‘Therapeutic jurisprudence has been practiced by many magistrates for many decades without a label. Calling it T[herapeutic] J[urisprudence] recognises and legitimises an attitude

to judging that is desirable’.[64] The identification of non-adversarial practice, therapeutic jurisprudence or solution-focused judging plays a key role in this because this labelling means they become part of the body of ‘judicial norms or procedures’ which form a key ‘wellsprin[g] of legitimacy’.[65] It also meant that magistrates exploring innovative ideas in the courtrooms could do so with the support and ‘safety’ of wider acceptance of its appropriateness, both at the court level and as a research-led practice. This means that a magistrate is not going out on a limb to the extent that they might otherwise be. The Resolution gives credence to experimentation as a ‘legitimate’ venture and one that justifies funding, where appropriate.

Criticism is not necessarily avoided in such circumstances, it may just be shared. Chief Justice Martin of the Western Australian Supreme Court, for example, has recognised the risk that for some therapeutic jurisprudence can be seen as ‘a lot of warm and fuzzy talk about being kind to crims’.[66] To this ‘soft on crime’ critique can be added the risk that the magistracy is straying into paternalism,[67] partiality,[68] or the province of the ‘amateur therapist’.[69] The alignment with a broader research-led discipline can assist here to prevent a diminution of legitimacy. This can occur in a number of ways.

First, it can occur through the promotion of methods such as therapeutic jurisprudence as an appropriate tool for judicial officers. Conferences, speeches, publications and legal education become an important landscape for dispelling concerns and informing the legal and broader community. Magistrate Michael King has been a powerful voice for this across his publications, court work and conferences he has organised and co-organised.[70] For instance, his Solution-Focused Bench Book included an introduction by then Chief Justice French of the High Court acknowledging that while ‘“therapeutic jurisprudence” may continue to raise eyebrows amongst some members of the judiciary, it reflects an important endeavour ... where the traditional judicial model of decision-making operating in isolation is inadequate to the task’.[71]

Similarly, support from peak bodies such as the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration, the Australian Law Reform Commission and the broader academy can also play an important role in giving credence to court reform.

Second, and related to the first, is evidence that therapeutic jurisprudence or court-based reforms have or are having a positive turnaround effect. For court innovations to be accepted and continue to be funded they need to have legitimacy, and to have legitimacy they need positive evaluations that show they are not too costly. Reliable and current evaluation can become key tools in the legitimacy game.[72] However, evaluations of innovative practice are not always as straightforward as standard criminological evaluation mechanisms (designed to give data about reduced recidivism or court processing times) and do not always reflect the on-the-ground reality of success for new-style reforms. For this reason, court case studies or ‘stories’ become very powerful in explaining, beyond the statistics, how the court is bringing about change and how potential concerns at such methods are misplaced. The NJC has used such stories to showcase its methods and success very powerfully.[73] Evaluations using a range of qualitative methods function in a similar way and use the words of defendants to explain how the court process has been positive or transformative.

Third, the alignment of innovative practices with a broader research-led discipline can garner acceptance from the broader community, justice personnel and political actors. Positive evaluation can be crucial within this process and can lead to greater government funding, increased support and the rolling out of innovations across and between jurisdictions. This, in turn, fuels the legitimacy ascribed to the reform and the court in which it is practised.

Much of the success in a trailblazing magistrate implementing reform comes down to the personality and acceptance of the particular magistrate. This is because the personality,[74] demeanour[75] and engagement[76] of an individual magistrate is crucial to his or her legitimacy within the community. This is particularly the case with therapeutic and non-adversarial practices which are shaped to a great extent by the person implementing them.[77] Remote areas of Western Australia tend to have a single magistrate with a deep understanding of local communities and there are many positive accounts of individual magistrates adopting innovative justice practices to better meet the needs of the Aboriginal communities in their jurisdiction. When working in the Pilbara, Magistrate Steve Sharratt is reported to have ‘had the unique situation of a community approaching the court to ask the court to sit at the community’.[78] When authors of this article observed Magistrate Sharratt in court on the West Kimberley circuit, they were struck by his ability to adapt his language to the persons appearing before him.

The willingness of an individual magistrate to adopt innovative practices to meet the needs of the communities in his or her jurisdiction is key, as is the willingness of the community to work with the magistrate with these practices. Magistrate Heath recounts the experience of Magistrate Antoine Bloeman, when he was the magistrate in the Kimberley:

The resident Magistrate ... increased his circuit to sit at a number of Aboriginal communities. When sitting at those communities he has adopted a number of approaches different to his ‘ordinary’ courts. ... Elders from the community either sit with the Magistrate or at the back of the court. Their presence is always acknowledged. ... Without the benefit of any additional court resources the Magistrate has been able to impart a large degree of community ownership of the process. In addition the decision to hold the sittings of the court at the Aboriginal communities has increased court attendance rates and saved the accused living at those communities the need to travel long distances to traditional court locations. The success of these moves could not have been achieved without spending considerable time communicating and building trust with the communities concerned.[79]

The accretion of respect for a particular magistrate and for the practices they have introduced can result in a real legitimacy gap when that respected magistrate departs.[80] As Murray notes in the neighbourhood court context:

Inevitably, a replacement of judicial personnel may mean that some projects or procedures fall away and that the court must adjust to a new range of skills and ideas. A change in a community court judicial officer therefore needs to be tightly managed to ensure that the court’s momentum or community relationships are not seriously affected.[81]

The key is for any transition in the magistracy to be carefully managed to preserve relationships and the legitimacy of the court and the programs set up within it. Shared handover periods, the retention of key staff with institutional knowledge and the involvement of the community and stakeholders are likely to assuage the uneasiness felt through this process of change.

The increasing realisation that the legal issues that bring a defendant to court are often far from the entirety of the issues that they are facing has seen courts work much more collaboratively with a range of experts, including case workers, psychologists, mental health personnel, Aboriginal liaison officers, housing officers and rehabilitation workers. From drug courts to neighbourhood courts to family violence courts, judicial officers participate in team meetings which allow for a more holistic and solution-focused approach. As Magistrate Fanning of the NJC explains:

The relationship that I have with clinicians [is key] ... [T]here is trust and understanding between those particular clinicians as to what I can do with that information [about clients] and what they can do with it.[82]

The model allows the magistrate to work collaboratively with the defendant and support staff to bring about improved outcomes from the justice process. This can pay a real legitimacy dividend when the court is seen as a place that cares and not just chastens.[83] Some NJC participants have reflected this in their comments that:

[I]f all the other courts were run like NJC a lot of people’s lives would be a lot different and a lot would have more help in their life to move on. Thanks to the NJC my life has turn[ed] round;

I was very impressed with the proceedings at NJC. I felt heard and supported in every way and the staff I dealt with were unfailingly polite, friendly and very helpful. I think this kind of court is a fantastic community facility; ...

This place is like home. Very, very safe. Thank you for that and for everything you have done for me ...[84]

Similarly, Aboriginal Sentencing Courts provide a different model for judicial collaboration which can enhance procedural justice and a defendant’s experience of the court process. As one Indigenous man recounted:

In a normal court room, a Magistrates’ Court, I get nervous. I think I’m going to get locked up and I stress out real bad ... and there’s all these charges and I don’t even know where they’re coming from. When I’m in the Koori court I feel really comfortable ‘cos I’ve got my Elders there and family.[85]

There are, however, perceived legitimacy perils associated with expert consultation. As Deputy Magistrate Popovic reveals:

I have been hearing a case involving a woman who I suspect has a mental illness. Her behaviour is most problematic and she is causing mayhem in her community. Her legal representation has been, to my subjective analysis poor. Her lawyers do not appear to have made any attempt to identify, let alone address, the issues. Have I acted appropriately by contacting the prison psychiatrist directly by email and setting out my concerns? At the next hearing of the matter, I will announce publicly that I contacted the psychiatrist – but I will not reveal the full detail of my correspondence. Since I am purging my sins, I need to confess that prior to arriving at a decision in relation to whether or not I should grant bail in this case, I spoke with two psychiatrists on the telephone. Neither of them told me what decision to make, but both assisted me to work through the issues and to make a decision based on better information. When I returned to the bench to continue with the hearing, I advised the parties that I had been discussing the matter with psychiatric professionals, but did not reveal what I discussed or what information I received.

I have no doubt that the quality of my decision making was enhanced by the enquiries I made, but I equally sure [sic] that I have impinged on the defendant’s, legal practitioners’ and community’s ‘right to know’. And, notwithstanding that I have considered the error of my ways, confronted with the same situation again, I would probably approach the matter in exactly the same way.[86]

The risk is that in departing from the traditional judicial role, through a more active judicial approach and partnering with experts, the ‘authority’ of the bench as a detached independent decision-maker will suffer,[87] or that elements of transparency or fairness will be compromised.[88] As King opines:

the judicial officer [is not] an expert in addressing underlying issues. It does not entitle the judicial officer to interfere in the activities of treatment and support agencies or to direct the form of counselling or support services to be used. These are matters beyond the expertise of the judicial officer and are best left to the appropriate treatment agency and the relevant participant to discuss and decide. Arguably, in such cases the judicial officer is at risk of promoting an anti-therapeutic effect – the resentment of the participant and agency of the judicial officer due to the interference – and of venturing beyond the judicial, supervisory role and into the province of the delivery of services.[89]

The key is monitoring the changing relationships of a magistrate with litigants, support and justice personnel, and the community so that interactions enhance, rather than erode, the judicial officer’s role[90] and consider a defendant’s legal rights.[91] This is particularly so if team meetings are occurring in the absence of a defendant, for which safeguards may be required such as counsel attending and the meeting being more exploratory than final.[92] Further, procedural justice scholarship would suggest that listening to the needs of litigants, respecting their cultural perspectives and agency through the collaborative or team process and giving them a voice through a fair court process is likely to augment a court’s legitimacy.[93] Importantly, the ‘trustworthiness’ of a judge, meaning an appraisal of the judicial officer’s ‘motives’ or whether they ‘truly car[e]’, is something likely to be significantly impacted by more solution-focused methods.[94] As Justice Warren notes, judicial

authority rests on our ability as judges to live up to those values, to meet the reasonable expectations of litigants and the public, to put a human face on who we are, what we do, and how we do it, to show that we care about the people affected by our processes and decisions – in short, to demonstrate that we are worthy of the public’s trust.[95]

The above analysis demonstrates that the most important aspect of legitimacy in the courtroom innovation/reform tussle is building relationships of trust within and around the court and ensuring courtroom innovation enhances procedural justice. This part explores legitimacy lessons for a mobile ‘solution-focused’ court model, and argues that this innovation can create and re-create the court’s legitimacy by working with community, facilitating community-owned and culturally secure solutions, and augmenting procedural justice. In line with this, it adopts a strengths-based, ‘needs-focused’ judging model;[96] that is, judging that identifies and responds to the needs, including cultural needs, of the person before the court, and that supports Aboriginal knowledge, and community-led services and solutions.[97]

Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (‘FASD’) encompasses a spectrum of disorders caused by prenatal alcohol exposure. It includes two Australian diagnostic categories: FASD with three sentinel facial features (where there is evidence of the presence of a short palpebral fissure, smooth philtrum and thin upper lip), which replaces a diagnosis of Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (‘FAS’); and FASD without three sentinel facial features (replacing the categories of Partial FAS (‘pFAS’) and Neurodevelopmental Disorder-Alcohol Exposed).[98] The issue of FASD in the West Kimberley region of Western Australia was highlighted by Bunuba women June Oscar, Emily Carter (Marninwarntikura Women’s Resource Centre) and Maureen Carter (Nindilingarri Cultural Health Services) as part of a broader campaign to reduce alcohol consumption in Fitzroy Crossing and publicise its catastrophic effects. In 2015, rates of FAS/pFAS of 12 per

100 children were reported in Fitzroy Crossing.[99] This is the highest reported prevalence in Australia, and on par with rates reported in ‘high-risk’ populations internationally.[100]

People with FASD may experience a range of cognitive, social and behavioural difficulties, including difficulties with memory, impulse control and linking actions to consequences, which make them susceptible to contact with the justice system.[101] When in contact with the justice system, difficulties with memory place young people with FASD at a disadvantage when trying to explain behaviour, give instructions to lawyers, or give evidence.[102] Repeated, negative contact with the justice system increases the likelihood of young people with FASD developing ‘secondary’ disabilities, such as mental illness, which increases their susceptibility to further contact with the justice system (as victims and offenders).[103] This cycle is particularly concerning in Western Australia, where, despite constituting only 6.7 per cent of the State’s youth,[104] they represented 76 per cent of youths in detention and 63 per cent of youths subject to community-based supervision.[105]

Aboriginal community members in Fitzroy Crossing, in particular, have expressed concern about the numbers of Aboriginal youth with FASD who are vulnerable to enmeshment in the justice system. These concerns are shared by justice professionals working in the West Kimberley. How might this be addressed? What methods would have the most benefits and be accepted and ‘owned’ by community members as well as the court? For solutions to be trusted they need to emerge out of extensive consultations with community members and justice professionals. The common thread emerging out of consultations across the West Kimberley[106] is a need for culturally secure initiatives that draw on the authority of Elders and devolve the care and management of Aboriginal youth with FASD to the Aboriginal community, particularly ‘on-country’. One part of a strategy to achieve this is community/court collaboration with the West Kimberley magistrate: a mobile ‘solution-focused’ court that draws on the techniques employed by ‘problem-oriented courts’, to promote better outcomes for Aboriginal young people with FASD and other cognitive impairments.

This mobile ‘solution-focused’ court model is a ‘hybrid’: it takes elements from the Aboriginal ‘Koori Court’ model, with its focus on the involvement of Elders in the court process, and the NJC model, which has a sole magistrate, a comprehensive screening process for clients when they enter the court, and rapid entry into, preferably ‘on-country’, support. This hybrid approach would facilitate greater Aboriginal community involvement in the justice process, promoting culturally secure and community-owned alternatives for Aboriginal youth with FASD – building, rather than eroding, relationships of trust within and around the court.

While adopting the terminology of ‘solution-focused’ judging, we stress that, in the Aboriginal context, solution-focused judging must be strengths and needs based, and explore opportunities for empowerment and collaboration with the relevant Aboriginal community. A ‘need-based’ approach is regarded as best practice in the context of sentencing persons with FASD: addressing a person’s ‘needs’ reduces their risk of reoffending and consequently promotes community protection.[107] A strengths-based approach acknowledges that the ‘solution’ resides not with the court or the mainstream justice process, but with the Aboriginal community. Dudgeon et al demonstrate that Aboriginal people view cultural strength and identity as key to social and emotional wellbeing, and that Aboriginal people are best placed to identify the challenges they face, and the solutions to those challenges.[108] Similarly, Baldry et al examined pathways of Aboriginal people with mental and cognitive impairments into, around and through the criminal justice system, and found that policy frameworks must be based on strategies that support ‘Indigenous-led knowledge’ and solutions, and ‘community-based services’.[109]

Aboriginal courts are a relatively new development in Australia’s court landscape, emerging in the late 1990s alongside the introduction of specialist magistrates courts to deal with particular types of offenders, such as drug offenders.[110] While not uniform, Australian Aboriginal courts tend to share the following features: involvement of Elders and respected persons in the court process; a non-adversarial, informal, and collaborative approach; awareness of the social context of the offender and offending; provision of culturally appropriate options; focus on rehabilitative outcomes and links to support services.[111] Western Australia has a patchwork of arrangements for Aboriginal offenders: a specialist Aboriginal family violence court – the Barndimalgu Family Violence Court – established in 2007 in Geraldton, as well as a handful of communities that allow Aboriginal participation in the sentencing process.

As we have highlighted, one of the most notable and successful aspects of the NJC is the quality of the intake ‘needs-based’ assessment by the clinical services team when an individual arrives at court. Such an approach has the potential to be critical to a successful, ‘FASD aware’ triage process outlined in this model. This ‘needs-focused’ approach shifts the emphasis of justice intervention from processing offenders to addressing needs: placing emphasis on the co-location of services (sorely needed in remote communities), a trauma-informed practice, a ‘no wrong door’ approach to treatment, and respect for Indigenous knowledge. The West Kimberley is likely to be an ideal place to pilot some kind of ‘mobile solution-focused court’ accompanying the magistrate’s West Kimberley circuit as it already has an innovative single magistrate with a deep understanding of local communities able to take on a ‘judicial monitoring’ role,[112] and a range of Aboriginal services, able, with the right support, to work with affected youth and their families, including ‘on-country’ options. There are many existing examples of Aboriginal Community controlled services, such as the Murulu FASD program run by Marninwarntikura in Fitzroy Crossing and the cultural health programs run by Nindilingarri Cultural Health Services, also in Fitzroy Crossing.

The strength to the proposed reform model is its support from the community and justice professionals – both in terms of the design of the model and the motivation for reform. This is a significant hurdle in the legitimacy/reform tussle. There is strong support for the creation of culturally secure initiatives that draw on the authority of Elders and devolve the care and management of Aboriginal youth with FASD to the Aboriginal community, particularly ‘on-country.’ The success of any reform initiative will be in the quality of consultation undertaken with the community serviced by the magistrate and the court, and, for Aboriginal communities, the ability of the reform to facilitate community-owned and culturally secure solutions.

Essential to the maintenance and augmentation of legitimacy is ensuring courtroom innovation enhances procedural justice. Mainstream courts can be alien environments for Aboriginal people. In the West Kimberley, for example, for many people English may be a second, third or fourth language. There is glaring need for interpreters able to assist Aboriginal people to understand and participate in the court process. A further source of alienation lies in the absence of recognisable Aboriginal cultural processes and symbols, and recognition of Aboriginal people’s own forms of cultural and legal authority, represented by Elders and other people of significance in the courtroom. Removing these sources of alienation will be crucial to the legitimacy of any mobile ‘solution-focused’ court model.

The above analysis also demonstrates that key to building trust for innovation is the personality and engagement of the regional magistrate, and that succession planning will be essential for maintaining legitimacy and longevity in the court innovation. The circuit magistrates can have deep links and understandings of the community which are likely to be central to the success of such a model. The mobile nature of the innovation will also be particularly reliant upon the magistrate’s skills in maintaining strong relationships and service delivery while shifting between communities. It would also be facilitated by targeted legislation like that employed in Victoria for Aboriginal Courts and the NJC; however, this is not routine in Australia. Arrangements in Western Australia occur under existing legislative arrangements. Legislative backing can support more innovative practices but also diversionary options and court partnerships with key agencies, all aspects central to the model’s ability to assist defendants with a range of challenges including FASD and related disorders. Legislative backing would also aid in reassuring the community that the adoption of therapeutic jurisprudential inspired court-based innovations is legitimate and supported by research-led practice, as discussed above, which can help to address objections to reform.

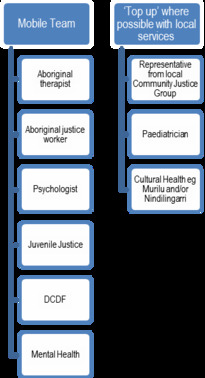

One of the key features of the proposed reform model is a mobile clinical services team able to undertake ‘needs-based’ assessment when an individual arrives at court. This assessment is critical to a successful ‘FASD aware’ triage process in the proposed court model. As noted, this ‘needs-focused’ approach emphasises the co-location of services, a trauma-informed practice, a ‘no wrong door’ approach to treatment, and respect for Aboriginal knowledges. As outlined in Figure 1, these mobile service providers will be complemented, in each community, by a range of Aboriginal services, able, with the right support, to work with youth and their families, including providing ‘on-country’ options.

Figure 1: ‘Justice on the Road’ – A Mobile Team

|

|

However, to be successful, this mobile team based approach must avoid any perception of bias from the magistrate working in and with a team of service providers and community members. The legitimacy risk, as highlighted above, is that in departing from the traditional judicial role, the magistrate’s ‘authority’ as a detached independent decision-maker will be undermined,[113] or that elements of transparency or fairness will be compromised.[114] To ensure the maintenance of legitimacy, the changing relationships of a magistrate with litigants, support and justice personnel, and the community, need to be carefully monitored to ensure that innovations in court practices enhance the judicial officer’s role[115] and are cognisant of the defendant’s legal rights.[116]

The proposed reform implemented collaboratively by an innovative magistrate would take a number of existing justice innovations and reforms, such as NJCs, front-end diversion, family conferencing, Aboriginal courts, therapeutic jurisprudence, triage, judicial management, and so on, and blend them to create a fresh engagement space with Aboriginal knowledge and practice where inter-cultural dialogue can take place.[117] There are already a number of community-owned initiatives in this space, such as the Yiriman project, representing the four language groups, Nyikina, Mangala, Karajarri and Walmajarri, in the Fitzroy Valley, which takes young people at risk onto remote desert country to

‘build stories, strength and resilience in young people’.[118] Evaluations of these initiatives must be reliable, public and sensitive to the objectives of the programs (rather than unduly confined to economic or statistical analysis). The NJC’s experience demonstrates the power of using stories to showcase innovative methods and successes. Awareness of the most effective forms of evaluation should be built into reform proposals from the beginning.

There are many motivations for introducing court-based reform. However, to ensure that innovative practices resonate with the community the court serves and are effective in achieving their aims, community buy-in is essential. The core of the process of legitimacy creation and re-creation in this context is trust. Innovation needs to be delicately managed, consultative and respectful of the complex web of relationships in and around the court.[119] Research suggests that perceptions of legitimacy can reflect the degree to which the values or ‘interests’ of an institution are seen to mirror that of an individual, which highlights the need for courts to be attuned and responsive to the needs and expectations of the wider society.[120]

Much can be taken from these legitimacy lessons in considering the potential of reforms such as a mobile solution-focused model. In particular, how this model might best build on existing innovative practices, such as NJCs, front-end diversion, Aboriginal courts, therapeutic jurisprudence, triage, judicial management, and so on, and blend them to create a fresh engagement space with Aboriginal knowledges and practices in a way that transforms the justice experience with the confidence and trust of the community that has helped craft it.

[*] Associate Professor, Law School, University of Western Australia.

[**] Senior Lecturer, Law School, University of Western Australia.

[***] Professor, Law School, University of Western Australia.

The authors would very much like to thank Ilana Hamilton for her research assistance with this article, and the anonymous reviewers of this journal for their constructive comments on an earlier draft. All errors remain our own.

[1] Justice Kathleen Blatz, quoted in Greg Berman, ‘“What is a Traditional Judge Anyway?” Problem Solving in the State Courts’ (2000) 84 Judicature 78, 80.

[2] See, eg, Kathy Mack and Sharyn Roach Anleu, ‘Opportunities for New Approaches to Judging in a Conventional Context: Attitudes, Skills and Practices’ [2011] MonashULawRw 11; (2011) 37 Monash University Law Review 187, 192–3; Jelena Popovic, ‘Court Process and Therapeutic Jurisprudence: Have We Thrown the Baby Out with the Bath Water?’ (2007) Special Series eLaw: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 60 <http://elaw.murdoch.edu.au/archives/issues/special/court_process.pdf> .

[3] Mack and Roach Anleu, ‘Opportunities for New Approaches to Judging in a Conventional Context’, above n 2, 190.

[4] Quoted in Michael King, ‘Applying Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Regional Areas – The Western Australian Experience’ (2003) 10(2) eLaw: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law, [14] <http://www.murdoch.edu.au/elaw/issues/v10n2/king102.html> .

[5] Mack and Roach Anleu, ‘Opportunities for New Approaches to Judging in a Conventional Context’, above n 2, 203.

[6] Richard H Fallon Jr, ‘Legitimacy and the Constitution’ (2005) 118 Harvard Law Review 1787, 1852.

[7] Marc A Loth, ‘Courts in a Quest for Legitimacy: A Comparative Approach’ in Nick Huls, Maurice Adams and Jacco Bomhoff (eds), The Legitimacy of Highest Courts’ Rulings: Judicial Deliberations and Beyond (TMC Asser Press, 2009) 267, 268.

[8] Max Weber, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization (A M Henderson and Talcott Parsons trans, Oxford University Press, 1947) 124–32 ff.

[9] Jürgen Habermas, Communication and the Evolution of Society (Thomas McCarthy trans, Beacon Press, 1979) 199–201.

[10] Alan Hyde, ‘The Concept of Legitimation in the Sociology of Law’ [1983] Wisconsin Law Review 379, 398, 426; cf Craig A McEwen and Richard J Maiman, ‘In Search of Legitimacy: Toward an Empirical Analysis’ (1986) 8 Law & Policy 257, 261.

[11] Nick Huls, ‘Introduction: From Legitimacy to Leadership’ in Nick Huls, Maurice Adams and Jacco Bomhoff (eds), The Legitimacy of Highest Courts’ Rulings: Judicial Deliberations and Beyond (TMC Asser Press, 2009) 3, 14–18; Fallon, above n 6, 1793. See also McEwen and Maiman, above n 10.

[12] Huls, above n 11, 15.

[13] Ibid 14.

[14] Ibid 17; Fallon, above n 6, 1796.

[15] Fallon, above n 6, 1795.

[16] Loth, above n 7, 269; Ronald Kahn and Ken I Kersch, ‘Introduction’ in Ronald Kahn and Ken I Kersch (eds), The Supreme Court and American Political Development (University Press of Kansas, 2006) 1, 17–19.

[17] McEwen and Maiman, above n 10, 270.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Tom R Tyler, ‘Citizen Discontent with Legal Procedures: A Social Science Perspective on Civil Procedure Reform’ (1997) 45 American Journal of Comparative Law 871, 887–92. See also Tom R Tyler, Why People Obey the Law (Yale University Press, 1990); Tom R Tyler and Kenneth Rasinski, ‘Procedural Justice, Institutional Legitimacy and the Acceptance of Unpopular US Supreme Court Decisions: A Reply to Gibson’ (1991) 25 Law and Society Review 621; Tom R Tyler, ‘Procedural Justice, Legitimacy and the Effective Rule of Law’ (2003) 30 Crime and Justice 283; Michael S King, The Solution-Focused Judging Bench Book (Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration, 2009) 34–5 <https://www.aija.org.au/Solution%20Focused%20BB/SFJ%20BB.pdf>.

[20] Joel B Grossman, ‘Review Essay: Judicial Legitimacy and the Role of the Courts: Shapiro’s Courts’ [1984] American Bar Foundation Research Journal 214, 219; Sarah Murray, The Remaking of the Courts: Less-Adversarial Practice and the Constitutional Role of the Judiciary in Australia (Federation Press, 2014) 38–9.

[21] Tyler, ‘Procedural Justice, Legitimacy and the Effective Rule of Law’, above n 19, 310.

[22] Arie Freiberg, ‘Innovations in the Court System’ (Paper presented at the Crime in Australia: International Connections, Australian Institute of Criminology International Conference, Melbourne, 29–30 November 2004) <http://www.aic.gov.au/media_library/conferences/2004/freiberg.pdf> see, eg, Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, Specialist Jurisdictions (27 April 2015) <http://www.magistratescourt.vic.gov.au/

jurisdictions/specialist-jurisdictions>.

[23] Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, Court Support Services (13 December 2012) <http://www.magistrates

court.vic.gov.au/jurisdictions/specialist-jurisdictions/court-support-services>; Jelena Popovic, ‘Judicial Officers Complementing Conventional Law and Changing the Culture of the Judiciary’ (2002) 20(2) Law in Context 121, 122–5.

[24] Kate Auty, ‘Introduction’ (2007) Special Series eLaw: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 4, 5 <http://elaw.murdoch.edu.au/archives/issues/special/introduction.pdf> .

[25] King, ‘Applying Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Regional Areas’, above n 4, [8].

[26] Ibid [6].

[27] Ibid [24]. See also Denis Temby, ‘Yandeyarra Aboriginal Community Court Project’ (2007) Special Series eLaw: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 141 <http://elaw.murdoch.edu.au/archives/

issues/special/yandeyarrat.pdf>.

[28] Kathleen Daly and Elena Marchetti, ‘Innovative Justice Processes: Restorative Justice, Indigenous Justice, and Therapeutic Jurisprudence’ in Marinella Marmo, Willem de Lint and Darren Palmer, Crime and Justice: A Guide to Criminology (Lawbook, 4th ed, 2012) 455, 467.

[29] King, ‘Applying Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Regional Areas’, above n 4, [13]; Michael S King and Steve Ford, ‘Exploring the Concept of Wellbeing in Therapeutic Jurisprudence: The Example of the Geraldton Alternative Sentencing Regime’ (2007) Special Series eLaw: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 9 <http://elaw.murdoch.edu.au/archives/issues/special/exploring.pdf> .

[30] King and Ford, above n 29, 18–19.

[31] See Popovic, ‘Judicial Officers’, above n 23, 131.

[32] Mack and Roach Anleu, ‘Opportunities for New Approaches to Judging in a Conventional Context’, above n 2, 193.

[33] Chief Magistrate Steven Heath, ‘Innovations in Western Australian Magistrates Courts’ (Paper presented at the Judicial Conference of Australia 2005 Colloquium, Sunshine Coast, 3 September 2005) 3 [10].

[34] King and Ford, above n 29, 25.

[35] Personal notes of Sarah Murray (Non-adversarial Justice: Implications for the Legal System and Society Conference, Melbourne, 4–7 May 2010).

[36] Members of the judiciary are also employing broader communication techniques, beyond the procedural justice toolkit, including ‘behavioural change techniques such as motivational interviewing and collaborative problem solving’: Pauline Spencer, ‘From Alternative to the New Normal: Therapeutic Jurisprudence in the Mainstream’ (2014) 39 Alternative Law Journal 222, 224; see also King, The Solution-Focused Judging Bench Book, above n 19; David B Wexler, ‘Guiding Court Conversations along Pathways Conducive to Rehabilitation: Integrating Procedural Justice and Therapeutic Jurisprudence’ (2016) 1(1) International Journal of Therapeutic Jurisprudence 367.

[37] Morris B Hoffman, ‘Therapeutic Jurisprudence, Neo-rehabilitationism, and Judicial Collectivism: The Least Dangerous Branch Becomes Most Dangerous’ (2002) 29 Fordham Urban Law Journal 2063, 2066 (citations omitted). For a response to Hoffman, see Nigel Stobbs, ‘In Defence of Therapeutic Jurisprudence: Threat, Promise and Worldview’ (2015) 8 Arizona Summit Law Review 325.

[38] See generally Sarah Murray, ‘Keeping it in the Neighbourhood? Neighbourhood Courts in the Australian Context’ [2009] MonashULawRw 6; (2009) 35 Monash University Law Review 74.

[39] Neighbourhood Justice Centre, Fighting Vandalism with Spray Paint? It Works! (12 July 2016) <http://www.neighbourhoodjustice.vic.gov.au/home/news+and+resources/news/fightingvandalism> .

[40] See, eg, Michael S King, ‘Restorative Justice, Therapeutic Jurisprudence and the Rise of Emotionally Intelligent Justice’ [2008] MelbULawRw 34; (2008) 32 Melbourne University Law Review 1096; David B Wexler and Bruce J Winick (eds), Law in a Therapeutic Key: Developments in Therapeutic Jurisprudence (Carolina Academic Press, 1996); Bruce J Winick and David B Wexler (eds), Judging in a Therapeutic Key: Therapeutic Jurisprudence and the Courts (Carolina Academic Press, 2003); Michael S King, ‘Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Australia: New Directions in Courts, Legal Practice, Research and Legal Education’ (2006) 15 Journal of Judicial Administration 129; Michael King, ‘Realising the Potential of Judging’ [2011] MonashULawRw 10; (2011) 37 Monash University Law Review 171.

[41] Winick and Wexler, Judging in a Therapeutic Key, above n 40, 8.

[42] Michael King et al, Non-Adversarial Justice (Federation Press, 2nd ed, 2014).

[43] Susan Daicoff, ‘Law as a Healing Profession: The “Comprehensive Law Movement”’ (2006) 6 Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal 1.

[44] Julie MacFarlane, The New Lawyer: How Settlement is Transforming the Practice of Law (University of British Columbia Press, 2008).

[45] Michael S King, ‘Should Problem Solving Courts be Solution-Focused Courts’ (Research Paper No 2010/03, Monash University Faculty of Law, 2010).

[46] Pauline Spencer, ‘To Dream the Impossible Dream? Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Mainstream Courts’ (International Conference on Law & Society, Hawaii, 5–8 June 2012) 9 n 10.

[47] Ibid 8–9.

[48] Ibid 9.

[49] David Fanning, Submission to the Family Law Council, Families with Complex Needs and the Intersection of the Family Law and Child Protection Systems (June 2015) 7 <https://www.ag.gov.au/

FamiliesAndMarriage/FamilyLawCouncil/Documents/FLC-submissions/David-Fanning.pdf>.

[50] Ibid 7–8.

[51] Michael Rempel et al, ‘What Works and What Does Not – Symposium’ (2002) 29 Fordham Urban Law Journal 1929, 1939.

[52] (2010) 239 CLR 531, 590 [122].

[53] Ibid, quoting Louis L Jaffe, ‘Judicial Review: Constitutional and Jurisdictional Fact’ (1957) 70 Harvard Law Review 953, 963.

[54] Tyler, ‘Citizen Discontent with Legal Procedures’, above n 19, 890.

[55] Freiberg, ‘Innovations in the Court System’, above n 22, 3.

[56] Arie Freiberg, ‘Specialised Courts and Sentencing’ (Probation and Community Corrections: Making the Community Safer Conference, Perth, 23–24 September 2002) 10 <http://www.aic.gov.au/media_library/

conferences/probation/freiberg.pdf>.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Fanning, above n 49, 8.

[59] Michael King and Stephen Wilson, ‘Country Magistrates’ Resolution on Therapeutic Jurisprudence’ (2005) 32(2) Brief 23, 24.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Andrew Cannon, ‘Therapeutic Jurisprudence in the Magistrates Court: Some Issues of Practice and Principle’ in Greg Reinhardt and Andrew Cannon (eds), 3rd International Conference in Therapeutic Jurisprudence: Transforming Legal Processes in Court and Beyond (Australian Institute of Judicial Administration, 2007) 129, 132.

[65] Kahn and Kersch, above n 16, 17.

[66] Quoted in Cannon, above n 64, 135.

[67] King, ‘Restorative Justice, Therapeutic Jurisprudence and the Rise of Emotionally Intelligent Justice’, above n 40, 1116.

[68] Mack and Roach Anleu, ‘Opportunities for New Approaches to Judging in a Conventional Context’, above n 2, 212.

[69] Hoffman, above n 37, 2072. See also the caution expressed in Chief Justice R S French, ‘The State of the Australian Judicature’ (Speech delivered at the 36th Australian Legal Convention, Perth, 18 September 2009) 16–20 <http://www.hcourt.gov.au/assets/publications/speeches/current-justices/frenchcj/

frenchcj18sep09.pdf>.

[70] Auty, above n 24, 4.

[71] King, The Solution-Focused Judging Bench Book, above n 19, viii.

[72] See, eg, Stuart Ross, ‘Evaluation of the Court Integrated Services Program’ (Final Report, University of Melbourne, December 2009) <https://www.magistratescourt.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Default/CISP_

Evaluation_Report.pdf>, which led to an expansion of the Court Integrated Services Program; KPMG, ‘Evaluation of the Drug Court of Victoria’ (Final Report, 18 December 2014) <https://www.magistrates

court.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/141218%20Evaluation%20of%20the%20Drug%20Court%20of%20Victoria.pdf>, which led to an expansion of the Drug Court of Victoria.

[73] Neighbourhood Justice Centre, ‘Reflections on Practice the First Six Years: The Neighbourhood Justice Centre Experience of “Doing Justice Locally”’ (Report, May 2012) <http://assets.justice.vic.gov.au/

njc/resources/003dc268-066d-4fd7-abf1-81359b25def6/reflections+on+practice.pdf>.

[74] For example, George Everson reports that ‘[t]hese studies of the work of the magistrates’ records in the New York courts are startling because they show us so clearly to how great an extent justice resolves itself into the personality of the judge’: George Everson, ‘The Human Element in Justice’ (1919) 10 Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology 90, 99; Elena Marchetti and Janet Ransley, ‘Applying the Critical Lens to Judicial Officers and Legal Practitioners Involved in Sentencing Indigenous Offenders: Will Anyone or Anything Do?’ [2014] UNSWLawJl 1; (2014) 37 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1, 31.

[75] Kathy Mack and Sharyn Roach Anleu, ‘Performing Impartiality: Judicial Demeanor and Legitimacy’ (2010) 35 Law & Social Inquiry 137, 142.

[76] Michael King, ‘Applying Therapeutic Jurisprudence from the Bench: Challenges and Opportunities’ (2003) 28 Alternative Law Journal 172, 174.

[77] Auty, above n 24, 5; ibid 175.

[78] Heath, above n 33, 2 [8].

[79] Ibid 2 [5]–[7].

[80] Spencer, ‘To Dream the Impossible Dream’, above n 46, 16.

[81] Murray, ‘Keeping it in the Neighbourhood’, above n 38, 92 (citations omitted).

[82] Stuart Ross et al, ‘Evaluation of the Neighbourhood Justice Centre, City of Yarra’ (Final Report, University of Melbourne, Brotherhood of St Lawrence and Flinders University, December 2009) 98.

[83] Ibid 116.

[84] Ibid 117.

[85] Popovic, ‘Court Process and Therapeutic Jurisprudence’, above n 2, 74.

[86] Ibid 61–2.

[87] Timothy Casey, ‘When Good Intentions Are Not Enough: Problem-Solving Courts and the Impending Crisis of Legitimacy’ (2004) 57 Southern Methodist University Law Review 1459, 1493, 1494, 1500; Mack and Roach Anleu, ‘Opportunities for New Approaches to Judging in a Conventional Context’, above n 2, 212; Hoffman, above n 37, 2072.

[88] Popovic, ‘Court Process and Therapeutic Jurisprudence’, above n 2, 64–6.

[89] King, ‘Realising the Potential of Judging’, above n 40, 184 (citations omitted).

[90] See, eg, ABC Radio National, ‘One-Stop Legal Shop’, The Law Report, 3 April 2007 <http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/lawreport/one-stop-legal-shop/3400580#transcript> .

[91] Popovic, ‘Court Process and Therapeutic Jurisprudence’, above n 2, 61; King, The Solution-Focused Judging Bench Book, above n 19, 202; Tina Previtera, ‘Responsibilities of TJ Team Members v Rights of Offenders’ (2007) Special Series eLaw: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 51.

[92] King, The Solution-Focused Judging Bench Book, above n 19, 202.

[93] See above n 19; Michael S King, ‘The Therapeutic Dimension of Judging: The Example of Sentencing’ (2006) 16 Journal of Judicial Administration 92, 95.

[94] Roger K Warren, ‘Public Trust and Procedural Justice’ (2000) 37 (Fall) Court Review 12, 14–15.

[95] Ibid 16.

[96] Harry Blagg, Tamara Tulich and Zoe Bush, ‘Placing Country at the Centre: Decolonising Justice for Indigenous Young People with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)’ (2016) 19(2) Australian Indigenous Law Review 4; Harry Blagg, Tamara Tulich and Zoe Bush, ‘Diversionary Pathways for Indigenous Youth with FASD in Western Australia: Decolonising Alternatives’ (2015) 40 Alternative Law Journal 257.

[97] Eileen Baldry et al, ‘A Predictable and Preventable Path: Aboriginal People with Mental and Cognitive Disabilities in the Criminal Justice System’ (Report, UNSW Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, October 2015) 161–4. <https://www.mhdcd.unsw.edu.au/sites/www.mhdcd.unsw.edu.au/files/u18/pdf/a_

predictable_and_preventable_path_final.pdf>.

[98] Carol Bower and Elizabeth J Elliott, ‘Australian Guide to the Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)’ (Report, Department of Health (Cth), April 2016) 4–5 <http://www.apsu.org.au/

assets/Uploads/20160505-rep-australian-guide-to-diagnosis-of-fasd.pdf>.

[99] James P Fitzpatrick et al, ‘Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in a Population-Based Sample of Children Living in Remote Australia: The Lililwan Project’ (2015) 51 Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 450, 453–4.

[100] Ibid 450, 455.

[101] Heather Douglas, ‘The Sentencing Response to Defendants with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder’ (2010) 34 Criminal Law Journal 221, 223–5.

[102] Legislative Assembly Education and Health Standing Committee, Parliament of Western Australia, Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: The Invisible Disability (2012) 75.

[103] Douglas, above n 101, 225, citing Gideon Koren, Idan Roifman and Irena Nulman, ‘Hypothetical Framework: FASD and Criminality – Causation or Association? The Limits of Evidence-Based Knowledge’ (2004) 2 Journal of FAS International 1, 4.

[104] Commissioner for Children and Young People, ‘The State of Western Australia’s Children and Young People’, (Report, Commissioner for Children and Young People, July 2014) 38 <https://www.ccyp.wa.

gov.au/media/1726/the-state-of-western-australia-s-children-and-young-people-edition-two-final-web-version-14-july-2014-1.pdf>.

[105] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Western Australia: Youth Justice Supervision in 2015–16’ (Youth Justice Fact Sheet No 82, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017) 2 <http://www.aihw.

gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129559069>.

[106] We undertook fieldwork in 2015 and 2016, which involved a range of interviews and focus groups in Broome, Fitzroy Crossing and Derby. Our research was based upon a participatory model that respects and integrates Indigenous perspectives into the research process. To this end we favoured an approach fitting broadly into the ‘Appreciative Inquiry’ paradigm, in that it is concerned with identifying strengths (or potential sources of strength) rather than continuously focusing on deficits and weaknesses: Gwen Robinson et al, ‘Doing “Strengths-Based” Research: Appreciative Inquiry in a Probation Setting’ (2013) 13 Criminology and Criminal Justice 3. This project was supported by a grant from the Australian Institute of Criminology through the Criminology Research Grants Program (CRG 35/14-15: ‘Developing Diversionary Pathways for Indigenous Youth with Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD): A Three Community Study in Western Australia’). The views expressed are the responsibility of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Institute of Criminology.

[107] Douglas, above n 101; David Milward, ‘The Sentencing of Aboriginal Accused with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: A Search for Different Pathways’ (2014) 47 University of British Colombia Law Review 1025.

[108] Pat Dudgeon et al, ‘Voices of the People: The National Empowerment Project’ (Research Report, 2015) 6, 115–6. <http://media.wix.com/ugd/396df4_85c3278f13ce47149bc394001d69dad6.pdf> .

[109] Baldry et al, above n 97, 161–4.

[110] Paul Bennett, Specialist Courts for Sentencing Aboriginal Offenders: Aboriginal Courts in Australia (Federation Press, 2016) 2.

[111] Ibid 4–5; King et al, above n 42.

[112] Harry Blagg, ‘Problem-Oriented Courts: Project 96’ (Research Paper, Law Reform Commission of Western Australia, March 2008) 7; King et al, above n 42.

[113] Casey, ‘When Good Intentions Are Not Enough’, above n 87, 1493, 1494, 1500; Mack and Roach Anleu, ‘Opportunities for New Approaches to Judging in a Conventional Context’, above n 2, 212; Hoffman, above n 37, 2072.

[114] Popovic, ‘Court Process and Therapeutic Jurisprudence’, above n 2, 64–6.

[115] See, eg, ABC Radio National, above n 90.

[116] Popovic, ‘Court Process and Therapeutic Jurisprudence’, above n 2, 61; King, The Solution-Focused Judging Bench Book, above n 19, 202; Previtera, above n 91.

[117] Martin Nakarta, ‘Indigenous Knowledge and the Cultural Interface: Underlying Issues at the Intersection of Knowledge and Information Systems’ (2002) 28 IFLA Journal 281, 285–6.

[118] Harry Blagg, ‘Reimagining Youth Justice: Cultural Contestation in the Kimberley Region of Australia since the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody’ (2012) 16 Theoretical Criminology 481, 491, quoting David Palmer, ‘“Opening Up to Be Kings and Queens of Country”: An Evaluation of the Yiriman Project’ (Report, November 2010) 10.

[119] Grossman, above n 20, 219; Murray, The Remaking of the Courts, above n 20, 38–9.

[120] Tyler, ‘Procedural Justice, Legitimacy and the Effective Rule of Law,’ above n 19, 310.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2017/32.html