University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE FRENCH COURT AND THE PRINCIPLE OF LEGALITY

BRUCE CHEN[*]

With the recent retirement of Robert French as Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, this article provides a retrospective on the French Court's treatment of the principle of legality. The principle of legality is a common law interpretive principle most commonly associated with the presumption that Parliament does not intend to interfere with fundamental common law rights, freedoms and immunities. This article demonstrates that the principle of legality has greatly risen in prominence during the French Court era. The article draws a narrative of the most significant principle of legality cases decided by the French Court. It identifies the unprecedented developments that have taken place, the areas in which divisions have emerged, and the implications for the principle going forward.

The retirement of the Hon Robert Shenton French AC as Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia in January 2017 marked the end of the ‘French Court’, which lasted about eight years and five months. During this time, a number of significant cases were decided on the principle of legality – a common law interpretive principle which stands for the presumption that Parliament does not intend to interfere with fundamental common law rights, freedoms, immunities and principles, or to depart from the general system of law (herein referred to collectively as ‘fundamental common law protections’), except where rebutted by clear and unambiguous language. French himself showed an undoubted interest in the principle of legality. There is a consensus amongst academics and practitioners alike that the principle has greatly risen in prominence in recent times.[1]

Much has been written about the principle of legality, but there is yet to have been a comprehensive review of the French Court’s contributions. This article seeks to provide that analytical review. Its purposes are twofold. The first aim is to demonstrate and attempt to explain the increased prominence and robustness with which the principle of legality has been applied by the French Court. The second is to identify several points of contention that arose in principle of legality cases decided by the French Court, and the varying approaches that members of that Court brought to bear on the principle’s operation.

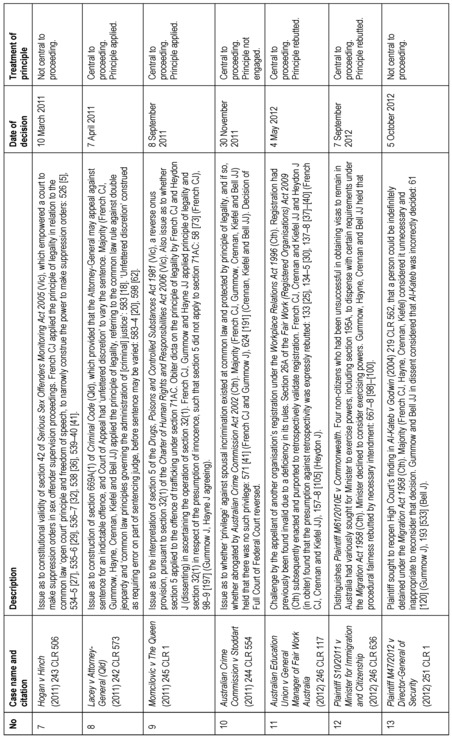

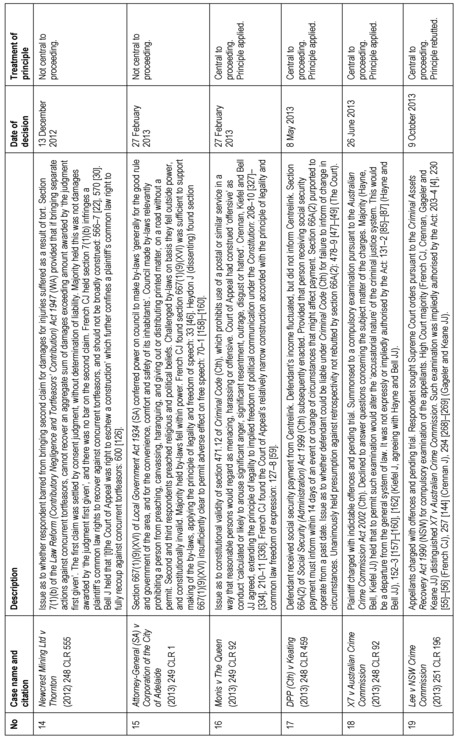

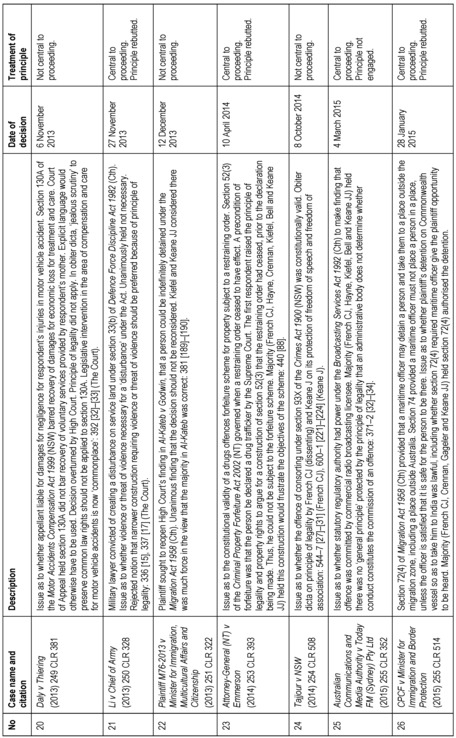

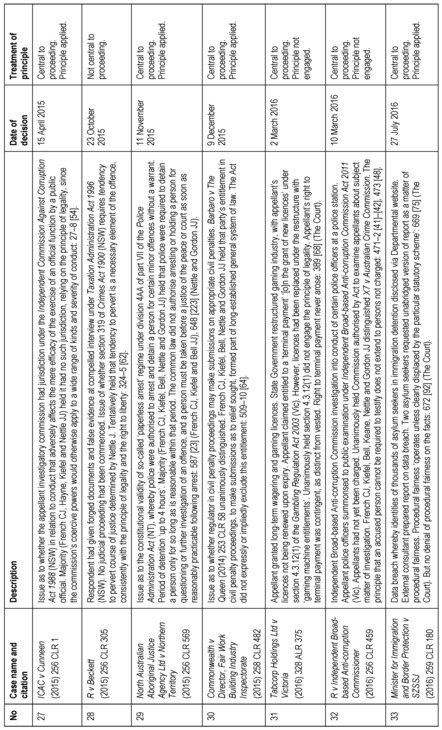

The selected cases for discussion are: Saeed v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship;[2] Lacey v Attorney-General (Qld);[3] Momcilovic v The Queen;[4] Monis v The Queen;[5] X7 v Australian Crime Commission;[6] Lee v NSW Crime Commission;[7] Independent Commission Against Corruption v Cunneen;[8] North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency v Northern Territory;[9] and R v Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commissioner.[10] These cases have been chosen on the basis that they particularly illuminate the French Court’s treatment of the principle. The cases also highlight the divisions within the French Court (most of these cases were decided by a majority, rather than unanimously). They are drawn from a larger pool of 33 cases[11] in which the principle of legality was discussed by the French Court, summarised in Appendix 1.

The discussion will consider the selected cases thematically, taking into account the changing composition of the French Court. Part II provides a brief introduction to the principle of legality. Part III outlines some contemporary developments which it is argued underlie the French Court’s treatment of the principle. The core of this article is Parts IV to IX, which examine the above-mentioned cases.

Part IV analyses the robustness with which the French Court applied the principle of legality. Part V examines the relationship between the principle of legality and constitutional law, including the interaction between the former and the presumption of constitutionality – the presumption that so far as the language permits, a statute should be interpreted so it is consistent with the Constitution. Part VI considers what insights might be drawn from the French Court’s approach to interpretation under section 32 of the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (Vic) (‘Victorian Charter’), which has been equated with the principle of legality. Part VII reviews a set of cases where the appointments of Gageler and Keane JJ created a division amongst the High Court bench with respect to the principle’s rebuttal by reference to statutory objects. Part VIII focuses on whether extrinsic materials can be drawn upon to evince Parliament’s intention that the principle is rebutted. Part IX considers an instance in which the principle was applied to a provision so as to narrow its scope, despite the provision itself not curtailing or abrogating any fundamental common law protection.

Part X draws together the above. This article finds that the principle of legality became a dominant principle of statutory interpretation under the French Court. It was determinative in several cases, resulting in interpretive outcomes which go beyond a statute’s literal and grammatical meaning, and in direct contradiction to explanations in extrinsic materials about how a statute should operate. At the same time, fundamental disagreements amongst members of the French Court arose, which were not entirely resolved. The principle of legality is not new – it is said to be ‘well-established’[12] and of ‘long standing’.[13] But despite this, there was actually limited consensus among the justices of the French Court about how the principle should operate. Part X concludes with where the changes to the composition of the High Court leave us now.

Finally, Appendix 1 summarises all principle of legality cases decided by the French Court.

The principle of legality is a common law principle of statutory interpretation. As early as 1908 in Potter v Minahan,[14] O’Connor J quoted approvingly from Maxwell on the Interpretation of Statutes, which said:

It is in the last degree improbable that the legislature would overthrow fundamental principles, infringe rights, or depart from the general system of law, without expressing its intention with irresistible clearness; and to give any such effect to general words, simply because they have that meaning in their widest, or usual, or natural sense, would be to give them a meaning in which they were not really used.[15]

Another authoritative exposition of the principle of legality was set out during the Hon Sir Anthony Mason’s time as Chief Justice. The majority of the High Court said:

The insistence on express authorization of an abrogation or curtailment of a fundamental right, freedom or immunity must be understood as a requirement for some manifestation or indication that the legislature has not only directed its attention to the question of the abrogation or curtailment of such basic rights, freedoms or immunities but has also determined upon abrogation or curtailment of them. The courts should not impute to the legislature an intention to interfere with fundamental rights. Such an intention must be clearly manifested by unmistakable and unambiguous language. General words will rarely be sufficient for that purpose if they do not specifically deal with the question because, in the context in which they appear, they will often be ambiguous on the aspect of interference with fundamental rights.[16]

It has been said that the Mason Court was the era in which the principle of legality ‘began its contemporary reassertion and strengthening’,[17] thus ‘herald[ing] this common law (rights) renaissance’.[18] The Mason Court decided significant and regularly-cited authorities on the principle of legality – particularly Re Bolton; Ex parte Beane;[19] Balog v Independent Commission Against Corruption;[20] Bropho v Western Australia;[21] and Coco v The Queen.[22]

The judgments of Gleeson CJ have also proven highly influential. His Honour pointed to the ‘institutional relationship between Parliament and the courts’, and drew a link between the principle of legality and the rule of law.[23] For example, in Electrolux Home Products Pty Ltd v Australian Workers’ Union,[24] Gleeson CJ described the principle of legality as:

govern[ing] the relations between Parliament, the executive and the courts. The presumption is not merely a common sense guide to what a Parliament in a liberal democracy is likely to have intended; it is a working hypothesis, the existence of which is known both to Parliament and the courts, upon which statutory language will be interpreted. The hypothesis is an aspect of the rule of law.[25]

Since the principle of legality’s existence is ‘known both to Parliament and the courts’, Parliament is taken to enact legislation with the principle in mind; and the courts will interpret the legislation according to that principle. Nevertheless, there is no clear demarcation between the judicial role and the legislative role. It is a separation of powers issue. The difficult question is: ‘Where does the constitutionally permissible territory of judicial “interpretation” end and the constitutionally impermissible territory of judicial “legislation” begin?’[26] According to French CJ, the principle of legality ‘has a significant role to play in the protection of rights and freedoms in contemporary society, while operating in a way that is entirely consistent with the principle of parliamentary supremacy’.[27]

There is a consensus that the principle of legality has in recent times been given prominence and robustly applied.[28] This is concurrent with the French Court era. French himself has described the principle of legality as ‘a strong presumption’.[29] As will be demonstrated in Part IV, the French Court has in some cases deployed the principle of legality to adopt a strained construction which is inconsistent with the literal and grammatical meaning of the statute, and inconsistent with what has been expressed in the extrinsic materials accompanying the statute. So why has the principle of legality reached ascendency under the French Court? One may speculate that there are several related factors.

The first probable factor is that a ‘“rights revolution” has swept the globe, bills of rights have been advocated on the ground that even elected legislatures in liberal democracies are prone to violate the rights of unpopular minorities’.[30] Despite several campaigns to enact a federal bill of human rights for Australia,[31] the Commonwealth Parliament has so far proven highly resistant to this revolution. At the state and territory level, only the Australian Capital Territory[32] and Victoria[33] have enacted bills of rights. The failure to enact a federal bill of human rights has isolated Australia. Australia is said to be the only democratic nation in the world without a national bill of human rights;[34] it is an outlier among Western countries.[35] Jurisdictions which share our common law pedigree have enacted national bills of human rights – Canada,[36] New Zealand,[37] Hong Kong,[38] South Africa,[39] the United Kingdom,[40] and Ireland.[41]

The judiciary have been grappling with how to protect an individual’s rights in the absence of a federal bill of human rights. For example, French CJ (extra-curially) has acknowledged that debate over a bill of human rights for Australia was ‘being pursued vigorously around the country’.[42] His Honour considered that the debate provided an ‘opportunity to reflect about’, amongst other things, the way in which ‘the common law is used to interpret Acts of Parliament and regulations made under them so as to minimise intrusion into those rights and freedoms’.[43] French CJ has also addressed audiences in the United States of America[44] and the United Kingdom,[45] which have bills of rights, where his Honour again pondered on human rights protection in Australia without a bill of human rights. His Honour acknowledged that ‘Australia is exceptional among Western democracies in not having a Bill of Rights in its Constitution, nor a national statutory Charter of Rights’.[46]

Typically, a bill of rights will require (either explicitly or implicitly) that legislation be interpreted compatibly with human rights. For example, section 32(1) of the Victorian Charter provides: ‘So far as it is possible to do so consistently with their purpose, all statutory provisions must be interpreted in a way that is compatible with human rights’. Robustly applying the principle of legality allowed the French Court to fill the void. It has been suggested that ‘the prominence of the principle of legality is at least in part owing to the lack of a federal ... bill of rights’;[47] and that the courts ‘may have used the principle to deal themselves into the business of enforcing rights’.[48] The French Court ‘has sought to fill the lacuna in formal rights protection in Australia’.[49] However, this explanation can be criticised for being a ‘backdoor means’[50] of introducing a bill of human rights without a democratic mandate.

The second possible factor relates to the judicial treatment of an existing common law interpretive principle relevant to human rights – the presumption of consistency with international law. That presumption provides ‘that a statute should be interpreted and applied, as far as its language permits’, so that it conforms with Australia’s obligations under international treaties – including international human rights treaties.[51] The French Court’s expansive deployment of the principle of legality to protect rights is therefore curious. Perhaps it is an attempt to minimise the application of the presumption of consistency with international law, with the concomitant controversy that attaches to judicial enforcement of human rights. Moreover, it may also reflect an inclination by some members of the French Court towards the common law,[52] rather than human rights law.[53]

The third potential factor is the ‘worrying trend [which] has emerged whereby parliaments at all levels have become increasingly willing to enact laws that impinge upon basic rights and freedoms’.[54] Recent studies have shown that Parliaments across Australia now frequently legislate for the abrogation or curtailment of fundamental common law protections. In a survey of Australian Commonwealth, state and territory statute books, George Williams found 350 instances of laws that infringe upon freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of association, freedom of movement, the right to protest, and basic legal rights.[55] Most of these laws have been enacted since the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.[56] Williams concluded that:

Past conventions and practices that lead parliamentarians to exercise self-restraint with regard to democratic principles were put aside in the name of responding to the threat of terrorism. Ultimately, this has come to affect not only the enactment of laws in that area, but has created a sense of permissiveness in a range of other areas as well, such as by enabling the enactment of stringent laws at the state level directed at organised crime and bikies.[57]

The French Court, in deploying the principle of legality to significant effect, may be responding to this pervasive rights-limiting environment. Interestingly though, this is incongruous with the rationale of the principle of legality.

As stated in Potter, the rationale for the principle is that it ‘is in the last

degree improbable’ that the legislature would overthrow fundamental common law protections without clear and unambiguous language.[58] But put crudely, Parliament can no longer, based on its track record, be presumed to be

committed to preserving fundamental common law protections – ‘[i]t now frequently legislates for their abrogation or curtailment’.[59] Potter was decided at a time when the ‘legal culture [was] sceptical of the inroads being made by statute on judge-made law’.[60] Nowadays, a strongly-applied principle of legality ‘fails

to have due regard to the fact that the significance of the common law is diminished in the modern legal framework’.[61] In Lee, Gageler and Keane JJ quoted approvingly of Gleeson CJ’s statement that ‘“modern legislatures regularly enact laws that take away or modify common law rights” and that the assistance to be gained from the principle “will vary with the context in which it is applied”’.[62]

A fourth likely factor was the personal influence of French CJ, who expressed enthusiasm towards the principle and was keen to develop its jurisprudence. As the ‘first among equals’,[63] the position of Chief Justice is well placed to shape the intellectual direction of the High Court.[64] There were early indicators that the principle of legality would be a focus for French CJ. In a matter of months into his appointment,[65] French CJ discussed the principle in K-Generation Pty Ltd v Liquor Licensing Court[66] and R & R Fazzolari Pty Ltd v Parramatta City Council.[67] Notably, French CJ cut a lone figure; while his Honour was in the majority in both cases, the remaining members had no regard to the principle of legality.

One year after his elevation, French CJ devoted an entire speech to the principle of legality.[68] French CJ saw the principle of legality as having a ‘constitutional’ dimension. His Honour observed how the common law had been referred to as ‘the ultimate constitutional foundation in Australia’.[69] Thus, ‘[t]he exercise of legislative power in Australia takes place in the constitutional setting of a “liberal democracy founded on the principles and traditions of the common law”’.[70] But while ‘the Constitution does not in terms guarantee common law rights and freedoms against legislative incursion’, the principle of legality ‘can be regarded as “constitutional” in character even if the rights and freedoms which it protects are not’.[71]

French CJ espoused the principle of legality in extra-curial writings over the course of his tenure. A search of available speeches on the High Court website[72] reveals that his Honour referred to the principle of legality in no fewer than 27 speeches.[73] Clearly, the principle of legality was of much interest to French. His Honour was acutely aware of the Australian context in which the principle of legality operated – a jurisdiction without a federal bill of human rights. This, together with French’s description of the principle in weighty terms, reinforces the view that the principle of legality’s prominence under his stewardship was no mere coincidence.

The principle of legality applies to a statutory provision where there is ambiguity in the broad sense,[74] such that the ambiguity is ‘resolved in favour of the protection of’[75] a fundamental common law protection. Conversely, the principle may be rebutted by clear and unambiguous language – either by express words or necessary implication. But what is considered clear and unambiguous? And is this affected by the principle of legality’s heightened ‘constitutional’ status? This is where the grey area lies, and the principle’s resistance to rebuttal can be seen. According to Jeffrey Goldsworthy, the principle of legality ‘is sometimes used to rationalise judicial resistance even to relatively clear legislative decisions’.[76] He cites Lacey, and ‘arguably’ Saeed, as examples.[77] This part examines the extent to which the principle of legality was applied to preserve fundamental common law protections.

These two cases were decided in the earlier years of the French Court. Saeed[78] was decided by French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Heydon, Crennan and Kiefel JJ (Kirby J had retired by this time). In a joint judgment, their Honours – with the exception of Heydon J[79] – approved the previous dicta by Gleeson CJ in Electrolux about the principle of legality governing ‘the relations between Parliament, the executive and the courts’ and being ‘a working hypothesis, the existence of which is known both to Parliament and the courts, upon which statutory language will be interpreted’.[80]

In Saeed, the constructional issue was whether the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) excluded the common law natural justice (otherwise known as procedural fairness) hearing rule in relation to offshore visa applicants. Section 51A provided that subdivision AB of division 3, part 2 of the Act is ‘taken to be an exhaustive statement of the requirements of the natural justice hearing rule in relation to the matters it deals with’. Section 51A was inserted following a prior High Court decision. In Re Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs; Ex parte Miah[81] (itself a case on the exclusion of natural justice), the Gleeson Court held that subdivision AB did not exclude common law procedural fairness to an onshore visa applicant. The Commonwealth Parliament responded by inserting the new section 51A.

French CJ, and Gummow, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ acknowledged that section 51A was ‘plainly a response’[82] to Ex parte Miah. Nevertheless, that case was about an onshore applicant. Their Honours decided that, applying the principle of legality,[83] the natural justice hearing rule was not excluded by the new section 51A in relation to offshore visa applicants.[84] This turned upon the meaning of the phrase ‘in relation to the matters it deals with’ in section 51A. Section 57, which fell within subdivision AB, provided that certain relevant information must be given to the applicant, but that provision only applied to onshore visa applicants. The ‘matter’ which section 57 deals with was in respect of onshore visa applicants only.[85] No other provision in subdivision AB dealt with the position for offshore visa applicants. As such, the giving of information to offshore visa applicants was not a ‘matter’ dealt with by subdivision AB.[86] The common law natural justice hearing rule had not been excluded for offshore applicants.

Lacey[87] is also illustrative of the strength with which the principle of legality was applied by the French Court. The composition of the Court was the same as in Saeed, but with the addition of Bell J (replacing Kirby J). The Court considered the scope of section 669A(1) of the Criminal Code (Qld). Section 669A originally provided:

The Attorney-General may appeal to the Court against any sentence pronounced by the court of trial and the Court may in its discretion vary the sentence and impose such sentence as to the said Court may seem proper.

It was then repealed and replaced. Section 669A(1)[88] now provides:

The Attorney-General may appeal to the Court against any sentence pronounced by

...

(a) the court of trial; or

(b) a court of summary jurisdiction in a case where an indictable offence is dealt with summarily by that court; and the Court may in its unfettered discretion vary the sentence and impose such sentence as to the Court seems proper.

The legislative change at issue here was the insertion of the word ‘unfettered’ before ‘discretion’. Like Saeed, this was in response to a court decision[89] which Parliament considered to be adverse.

A 6:1 majority (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ; Heydon J dissenting) referred to the common law rule against double jeopardy,[90] as well as the more amorphous notion of ‘common law principles governing the administration of [criminal] justice’.[91] The majority held that, as a ‘specific application of the principle of legality’, in the absence of clear language the ‘unfettered discretion’ should be more narrowly construed so that error on the part of the sentencing judge was required before the discretion was enlivened.[92] Otherwise, it ‘tips the scales of criminal justice in a way that offends “deep-rooted notions of fairness and decency”’.[93]

Saeed and Lacey are considered high watermark cases for the principle of legality.[94] Saeed has been taken by commentators as the Court having accorded ‘constitutional’ status on the principle,[95] just as French CJ did in his earlier speech.[96] The French Court – in endorsing Gleeson CJ’s passage about the principle governing ‘the relations between Parliament, the executive and the courts’[97] – has ‘clothed the principle of legality in Australian constitutional garb’,[98] or ‘termed the principle a constitutional safeguard’.[99] Such a weighty status appears linked to the increased willingness of the French Court to apply the principle of legality powerfully. It is as if the ‘constitutional’ designation of the principle has afforded it ‘special judicial protection’,[100] and ‘strengthen[ed] its normative force’.[101] As Matthew Groves has said, if the principle of legality is:

somehow attributed to the Constitution, or even if it is just an interpretative hypothesis that the Constitution indirectly requires to make institutional arrangements more workable, it becomes harder to criticise as an exercise in judicial law making or a defiance of Parliament.[102]

In both cases, the French Court displayed a strict, robust approach to the principle’s application. The French Court was unforgiving of the legislative drafting. Saeed, however, was arguably still an orthodox application of the principle of legality. The statutory words in the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) were ambiguous. There was scope for the principle to operate. As the French Court reasoned, the phrase ‘in relation to the matters it deals with’ lent itself to a more restrictive, rights-protective construction. If the intention was to exclude the natural justice hearing rule for offshore applicants, this was not clearly and unambiguously conveyed in the legislative drafting. Their Honours ‘hearkened to the actual terms of s 51A’.[103]

Lacey arguably highlights the lengths to which the French Court was willing to stretch statutory language, so as not to abrogate or curtail fundamental common law protections. The words ‘appeal’ and ‘unfettered discretion’ were key in construing section 669A(1) of the Criminal Code (Qld). The majority saw ambiguity in the word ‘appeal’ – associating it with an appeal by way of rehearing, which requires error.[104] It was only once an error had been identified that ‘unfettered’ came into play, in the form of an ‘unfettered discretion’ to vary the sentence. ‘Unfettered’ was interpreted so that the discretion did ‘not actually mean without limits’.[105]

This was a departure from the provision’s literal and grammatical

reading. The majority’s construction was both strained and disjointed. First, a literal meaning of ‘unfettered’ is ‘[n]ot confined or restrained by fetters

... Unrestrained, unrestricted’.[106] Therefore, a discretion that requires error in sentencing is not ‘unfettered’. Second, the provision was not structured into two stages – identification of error and variation of sentence. Rather, the word ‘unfettered’ applied to the discretion in its totality. In a powerful dissent, Heydon J considered that the provision ‘amounted to clear language’.[107] His Honour described the majority’s construction as an ‘artificial’[108] reading: ‘A discretion which exists only in relation to the second stage and does not exist in relation to the first is not an unfettered discretion’.[109] That construction was also ‘otiose’[110] – the legislative insertion of the word ‘unfettered’ had ‘achieved precisely nothing’.[111] As to the word ‘appeal’, Heydon J found it ‘unsound’ to assume that all appeals ‘must involve the correction of error’.[112]

Arguably, the words of the statute were clear and unambiguous enough to completely rebut the principle of legality. Yet the 6:1 majority did not think so. Relying on a perceived ambiguity of the word ‘appeal’, the majority was able to apply the principle to reach what was undoubtedly a strained meaning. But the majority must have considered this manner of the principle of legality’s application to be a legitimate outcome of statutory interpretation – one that did not frustrate legislative intention; and fell within the parameters of what is judicial interpretation, rather than judicial rewriting.

Another example of the straining of statutory language was NAAJA,[113] decided in the final years of the French Court. By this time, Gummow, Heydon, Crennan and Hayne JJ had retired. They had been replaced by Gageler, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ. The main issue was the constitutional validity of a so-called ‘paperless arrest’ regime under division 4AA of part VII of the Police Administration Act 1978 (NT), whereby police were authorised to arrest and detain a person for certain minor offences without a warrant. Nevertheless, there arose a constructional issue. Section 133AB (emphasis added) provided the procedure for when a member of the police has arrested a person without a warrant:

(2) The member may take the person into custody and:

(a) hold the person for a period up to 4 hours ...

(3) The member, or any other member, on the expiry of the period mentioned in subsection (2), may:

(a) release the person unconditionally; or

(b) release the person and issue the person with an infringement notice in relation to the infringement notice offence; or

(c) release the person on bail; or

(d) under section 137, bring the person before a justice or court for the infringement notice offence or another offence allegedly committed by the person.

Section 137(1) relevantly provided:

a person taken into lawful custody under this or any other Act shall ... be brought before a justice or a court of competent jurisdiction as soon as is practicable after being taken into custody, unless he or she is sooner granted bail under the Bail Act or is released from custody.

The question was whether, as the plaintiffs argued, police had a discretion

to detain the person for any period up to this maximum of four hours, or

as the Northern Territory argued, they were required to detain the person only

for so long as is reasonable within that maximum of four hours. A majority

of the French Court (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ) held

in favour of what Gageler J called the Northern Territory’s ‘strained but

benign construction’.[114] Gageler J preferred the plaintiffs’ ‘literal and draconian construction’.[115] This favoured their respective arguments about constitutional validity (see Part V below). Keane J did not consider the issue necessary to determine in the circumstances.[116]

Beginning with Gageler J, his Honour considered that the structure of section 133AB was ‘plain enough’.[117] Section 133AB(2) provided for the detention of a person for up to four hours, with four options under section 133AB(3) regarding how to deal with the person at the end of this period.[118] The fourth option, under section 133AB(3)(d) was to bring the person before a justice of the peace or court under section 137.[119]

There was, however, a tension between section 133AB(2) and section 137(1),[120] the latter of which required that the person be brought before a justice of the peace or court as soon as is practicable after being taken into custody. According to Gageler J, this could be naturally reconciled – the requirement to bring the person before a justice of the peace or court as soon as is practicable applied only after the four hour period had expired, and where the member of police had decided to take the fourth option.[121] His Honour found additional support for this construction in the purpose underlying division 4AA,[122] identified by reference to extrinsic materials[123] (see Part VIII below).

Gageler J considered that the Northern Territory’s construction – and by implication, that adopted by the majority – was a strained one.[124] It was a ‘distortion’ of the words of section 133AB,[125] and that construction was not ‘reasonably open’.[126]

French CJ, and Kiefel and Bell JJ held that ‘[t]he common law does not authorise the arrest of a person or holding an arrested person in custody for the purpose of questioning or further investigation of an offence’.[127] It was an ‘obvious application of the principle of legality’ that, in the absence of clear words, a person must be taken before a justice of the peace or court as soon as practicable if not earlier released on bail or custody.[128] Their Honours found that ‘[a]s a matter of textual analysis’, this common law obligation was not modified by section 133AB.[129] The four hour period ‘does no more than impose a cap’ and ‘should be regarded as a maximum rather than the norm’.[130] This was regardless of whether or not section 137(1) had been enacted.[131] The Northern Territory’s construction was to be preferred.

Nettle and Gordon JJ reached the same outcome as French CJ, Kiefel and Bell JJ.[132] On the principle of legality, their Honours stated that:

s 137(1) reflects the basic common law tenet that a person must be taken before a court as soon as reasonably practicable following arrest. A statute that departs from that fundamental position would need to be expressed in unmistakably clear terms.[133]

Their Honours considered a number of further supportive textual and contextual factors.[134] Their Honours were also more willing than French CJ, Kiefel and Bell JJ[135] to consider the interaction between the provisions, finding that their construction of section 133AB(3) was ‘capable of operating harmoniously, and simultaneously, with s 137(1)’.[136]

Although NAAJA resulted in a 5:1 majority on the statutory interpretation issue, the case evinced a number of diverging approaches to the principle of legality. French CJ, Kiefel and Bell JJ greatly emphasised the principle, with their Honours’ construction turning solely upon the principle of legality. It was determinative, in the same way that it was determinative in Lacey. Nettle and Gordon JJ also raised the principle of legality, but placed much less emphasis on it. It was only one principle of statutory construction out of several relevant interpretive factors. This may ultimately signal a shift from the dominant role given to the principle for which the French Court is known. Gageler J (dissenting) was sceptical of using the principle of legality to strain the statutory words, instead giving a literal meaning to the words ‘up to 4 hours’ and ‘on the expiry of the period’.

The principle of legality interacts closely with constitutional law. Never has this relationship been as prominent as under the French Court. Logically, the meaning of a statutory provision must first be ascertained, before it can be determined whether the provision as interpreted is constitutionally invalid. Thus, the more forcefully the principle of legality is deployed in statutory interpretation, the less resort is ultimately had to constitutional principles. The application of the principle of legality can head off the issue of constitutional invalidity at the pass. This is ‘a dynamic at work in many recent constitutional cases’.[137]

As Gageler J explained in NAAJA, with a heavy dose of scepticism:

The arguments divide along battlelines not unfamiliar where questions about the constitutional validity of a law are abstracted from questions about the concrete application of that law to determine the rights and liabilities of the parties. The party seeking to challenge validity advances a literal and draconian construction, even though the construction would be detrimental to that party were the law to be held valid. The party seeking to support validity advances a strained but benign construction, even though the construction is less efficacious from the perspective of that party than the literal construction embraced by the challenger. The constructions advanced reflect forensic choices: one designed to maximise the prospect of constitutional invalidity; the other to sidestep, or at least minimise, the prospect of constitutional invalidity. A court should be wary.[138]

NAAJA was such an example. The plaintiffs argued for a construction which was harsh on their clients’ right to liberty. This was to maximise the likelihood of constitutional invalidity being found, on the basis of breach of the separation of powers[139] and undermining or interfering with the institutional integrity of the Northern Territory courts.[140] The Northern Territory argued for a less restrictive construction, so as to minimise the chances of constitutional invalidity. Only Gageler J accepted the plaintiffs’ construction. His Honour considered it necessary for the Court to ‘face up to the constitutional consequences’.[141] Gageler J in dissent found that the legislation was constitutionally invalid. French CJ, and Kiefel and Bell JJ, and Nettle and Gordon JJ, having applied the principle of legality to accept the Northern Territory’s construction, were able to find the legislation constitutionally valid.

A litigation strategy similar to the plaintiffs’ in NAAJA was adopted by the appellants in Monis.[142] However, three Justices of the Court treated the interaction between the principle of legality and constitutional law in a notably different manner.

Although the principle of legality has been accorded ‘constitutional’ status, the implications of this characterisation are not entirely clear. The predominant view is that the principle of legality is ‘small c’ constitutional,[143] in the sense that it reflects the institutional relationship between Parliament and the courts. The question is whether it will develop to extend to ‘large C’ constitutional issues?[144] Could it apply directly to Constitutional provisions which protect ‘rights’?[145] That is an issue which arose in Monis.[146]

There is another principle of statutory interpretation which already traverses this subject matter. The presumption of constitutionality is the ‘presumption that Parliament did not intend to pass beyond constitutional bounds’.[147] So far as the language permits, an enactment should be interpreted so it is consistent with the Constitution, unless the intention is clear that the statute is to operate in a way that results in constitutional invalidity.[148]

Nevertheless, in Monis, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ considered that – quite apart from this presumption – the principle of legality ‘may be applied

to constitutionally protected freedoms’.[149] In that case, section 471.12 of the Criminal Code (Cth)[150] prohibited the use of a postal or similar service in a way that reasonable persons would regard as being, in all the circumstances, menacing, harassing or offensive. Monis was charged with contraventions of section 471.12.[151] Droudis was Monis’ girlfriend, who allegedly aided and abetted him. Monis and Droudis submitted that ‘offensive’ in section 471.12 should be construed as including ‘hurt or wounded feelings’[152] – a low threshold. Although this would more severely infringe on their free speech and mean they would more likely be found guilty of the offence, such a construction aided their further submission – that section 471.12 was invalid for infringing the implied constitutional freedom of political communication.

In the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal, Bathurst CJ construed ‘offensive’ as meaning ‘calculated or likely to arouse significant anger, significant resentment, outrage, disgust, or hatred in the mind of a reasonable person in all the circumstances’.[153] Rejecting Monis and Droudis’ submission, his Honour held that it was not enough that it ‘would only hurt or wound the feelings of the recipient, in the mind of a reasonable person’.[154]

Turning to the High Court’s decision, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ agreed with Bathurst CJ’s construction. ‘Offensive’ should be ‘confined to more seriously offensive communications’;[155] ‘at the higher end of the spectrum’.[156] Significantly, their Honours applied the principle of legality to reach this construction. Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ extended the principle to the implied freedom of political communication. Their Honours applied both the presumption of constitutionality and the principle of legality to ‘read down’ section 471.12.[157] This was said to have been done with ‘an eye’[158] to the Lange test,[159] but before their Honours fully engaged with that test. In other words, this spanned both the principle of legality and constitutional validity analyses.

This reasoning has numerous implications. There are differences in operation between the principle of legality and the presumption of constitutionality that would be overlooked by essentially merging these two principles. For example,[160] Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ acknowledged that ‘[g]eneral words and expressions may sometimes give rise to difficulties’ in applying the presumption of constitutionality. That is because ‘[s]uch words may be capable of applying a provision to cases where it is within power as well as to cases where it is beyond power’.[161] In those circumstances, it has previously been said there must be legislative intention that the general words are to be read down, ‘based upon some particular standard criterion or test [that] can be discovered from the terms of the law itself or from the nature of the subject matter with which the law deals’.[162] By contrast, under the principle of legality ‘it may not be necessary to find a positive warrant for preferring a restricted meaning’.[163] Presumably this is because of the well-established notion that Parliament is aware that the principle of legality applies to read down general words.

It is also unclear how the principle of legality would sit with the broader constitutional law jurisprudence. How does one know when to read down the legislation pursuant to a constitutionally protected ‘right’, before having properly determined that the legislation is unconstitutional?[164] What other constitutional ‘rights’ might the High Court extend the principle of legality to?[165] And why did their Honours not simply apply the principle to the common law freedom of expression?[166]

By contrast, French CJ applied the principle of legality in a more conventional manner. His Honour held that the Court of Criminal Appeal’s narrower construction of ‘offensive’ ‘accorded with the principle of legality in its application to freedom of expression’[167] as a common law freedom.[168] Amongst other things, the principle indicated ‘a high threshold to be surmounted before

the content of a communication ... can be characterised as “offensive”’.[169] His Honour approached the principle of legality as an ‘anterior’ step of statutory interpretation, prior to determining constitutional validity.[170]

Subsequently in Tajjour v New South Wales,[171] Keane J stated:

Before any question arises of the [constitutional] validity of legal regulation of an activity, one must determine whether a given piece of legislation affects the activity at all; and it is in relation to this step in the analysis that the presumption against interference with the [overlapping fundamental common law protection] is to be taken into account.[172]

This appears to reject the approach of Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ in Monis. Ultimately, no member of the French Court expressed disagreement with Bathurst CJ’s restrictive construction of section 471.12.[173]

Another area for examination is the French Court’s approach to interpretation pursuant to the Victorian Charter. Section 32 is directed at the interpretation of legislation to protect and promote human rights recognised by the Victorian Charter. Sub-section (1) states that: ‘So far as it is possible to do so consistently with their purpose, all statutory provisions must be interpreted in a way that is compatible with human rights’. The Victorian Charter recognises that it may not always be ‘possible’ to interpret a statutory provision compatibly with human rights.[174]

This Part shows that there was an inconsistency in approach and attitude towards section 32(1) by certain members of the French Court in Momcilovic,[175] when compared with the principle of legality.

Momcilovic is the only significant High Court case to date on section 32(1).[176] It was decided in the earlier years of the French Court, prior to the appointments of Gageler, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ. The French Court drew comparisons between section 32(1) and the ordinary principles of statutory interpretation (of which the principle of legality is one).

Six separate judgments were produced in Momcilovic, creating considerable difficulty in identifying the exact precedent set by the French Court.[177] In respect of section 32(1), a 6:1 majority held that it did not replicate the extensive effects of section 3 of the United Kingdom Human Rights Act 1998 (‘UK HRA’). The United Kingdom approach was legislating rather than interpreting; going beyond the proper role of the courts in interpreting statutes in the Australian context. Although one may ask: could similar accusations not be levelled at the principle of legality?

Section 3(1) of the UK HRA provides that ‘[s]o far as it is possible to do so, primary legislation and subordinate legislation must be read and given effect in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights’. The United Kingdom courts have held that section 3(1) is ‘very strong and far reaching’.[178] It may ‘require a court to depart from the unambiguous meaning the legislation would otherwise bear’;[179] ‘require the court to depart from ... legislative intention, that is, depart from the intention of the Parliament which enacted the legislation’;[180] and ‘involve a considerable departure from the actual words’.[181]

The majority of the Court (Heydon J dissenting) sought to differentiate section 32(1) from section 3(1) of the UK HRA. Each member of the Court spoke of the orthodoxy of statutory interpretation.[182] French CJ spoke to the limits of statutory interpretation:

if the words of a statute are clear, so too is the task of the Court in interpreting the statute with fidelity to the Court’s constitutional function. The meaning given to the words must be a meaning which they can bear ... In an exceptional case the common law allows a court to depart from grammatical rules and to give an usual or strained meaning to statutory words where their ordinary meaning and grammatical construction would contradict the apparent purpose of the enactment. The court is not thereby authorised to legislate.[183]

French CJ was the only member of the majority to expressly find similarities between the operation of the principle of legality and section 32(1)[184] (Heydon J contrasted them in dissent). Echoing his Honour’s earlier speeches, the principle was ‘constitutional’ in character, in that ‘[t]he common law in its application to the interpretation of statutes helps to define the boundaries between the judicial and legislative functions’.[185] As to the principle’s operation, ‘[i]t requires that statutes be construed, where constructional choices are open, to avoid or minimise their encroachment upon rights and freedoms at common law’.[186] It was a ‘powerful’ principle.[187] But it operated ‘within constitutional limits’.[188] It will only afford such protection ‘as the language of the statute will allow’.[189] Where the statutory language leaves open ‘only an interpretation or interpretations which infringe one or more rights or freedoms’, the principle of legality ‘is of no avail against such language’.[190]

French CJ equated section 32(1) with the principle of legality. It ‘applies ... in the same way as the principle of legality but with a wider field of application’.[191] His Honour expressly endorsed the Victorian Court of Appeal when it observed that if Parliament had intended to make a change in the rules of statutory interpretation ‘its intention to do so would need to have been signalled in the clearest terms’.[192] Interestingly, this was French CJ applying the principle of legality – an interpretative principle protecting fundamental common law protections – to interpret section 32(1), an interpretive provision protecting human rights.

Crennan and Kiefel JJ found that section 32(1) ‘does not state a test of construction which differs from the approach ordinarily undertaken by courts towards statutes’.[193] It could not ‘be said that s 32(1) requires the language of a section to be strained to effect consistency with the Charter’.[194] Any inconsistent legislation prevails. Their Honours said this ‘reaffirms the role of the legislature and makes clear that a court’s role in ascertaining the meaning of the legislation remains one of interpretation’.[195]

As for Gummow J (Hayne J agreeing), his Honour also said that section 32(1) confers an interpretive power, rather than ‘a law-making function of a character which is repugnant to the exercise of judicial power’.[196] Gummow J aligned section 32(1) with ordinary principles of statutory interpretation. His Honour also cited Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (‘Project Blue Sky’), directly quoting this authoritative passage:

the duty of a court is to give the words of a statutory provision the meaning that the legislature is taken to have intended them to have. Ordinarily, that meaning (the legal meaning) will correspond with the grammatical meaning of the provision. But not always. The context of the words, the consequences of a literal or grammatical construction, the purpose of the statute or the canons of construction[197] may require the words of a legislative provision to be read in a way that does not correspond with the literal or grammatical meaning.[198]

Gummow J may have left some room to move as to section 32(1) operating more strongly than ordinary principles of statutory interpretation.[199] His Honour said that the above reasoning ‘applies a fortiori where there is a canon of construction mandated, not by the common law, but by a specific provision such as s 32(1)’.[200]

Gummow J’s view is quite different from that of French CJ. French CJ would give an unusual or strained construction ‘[i]n an exceptional case’, only where the ordinary and grammatical meaning ‘would contradict the apparent purpose of the enactment’.[201] But such a restrictive approach is not justified by the passage in Project Blue Sky. That passage, which footnotes the principle of legality as an example of ‘the canons of construction’,[202] recognises that such canons may require statutory words to be read in a way that does not correspond with a literal or grammatical meaning.[203]

Bell J considered that, applying section 32(1), where the literal or grammatical meaning of a statutory provision unjustifiably limited human rights under the Victorian Charter, then this apparent conflict needed to be resolved ‘by giving the provision a meaning that is compatible with the human right if it is possible to do so consistently with the purpose of the provision’.[204] This includes legislation enacted prior to the Victorian Charter, which ‘may yield different, human rights compatible, meanings in consequence of s 32(1)’.[205] However, the task was ‘one of interpretation and not of legislation’ – ‘[i]t does not admit of “remedial interpretation” ... as a means of avoiding invalidity’.[206]

Heydon J was the only judge to find that section 32(1) duplicated section 3(1) of the UK HRA. However, this was one reason for his Honour to find that section 32(1) was constitutionally invalid.[207] Section 32(1) ‘[i]n effect’ permitted the courts to ‘disregard the express language of a statute’.[208] Heydon J repeatedly emphasised that section 32(1) crossed over into Parliament’s legislative function.[209] Following his retirement from the High Court, Heydon expressed the view that the principle of legality was ‘likely to be more effective’[210] than section 3(1) of the UK HRA in protecting rights – the former ‘can achieve a similar purpose without involving the courts in the dangers of creating new legislative rules’.[211] Undoubtedly, Heydon would think the same in the Victorian Charter context.

On the one hand, the general tenor of Momcilovic is a reassertion of common law statutory interpretation techniques as entirely orthodox (including, according to French CJ, the principle of legality). On the other hand, straining the statutory language and departing from the literal meaning of the text to ensure human rights compatibility was looked down upon by French CJ, Crennan, Kiefel and Heydon JJ.

Drawing from the above, did the constructions reached in Lacey and NAAJA not involve a considerable departure from the actual words? Did they not disregard the express language of the statute? Was the language not strained to effect consistency with fundamental common law protections? Were they really exceptional cases where an ordinary or grammatical meaning would contradict the apparent purpose of the statute? Did they not involve a kind of remedial interpretation? Heydon J certainly thought the majority’s construction in Lacey was ‘artificial’.[212] Gageler J described the majority’s construction in NAAJA as ‘strained’[213] and a ‘distortion’.[214] Is there a disconnect between what the French Court was saying about the principle of legality, and what it was doing with it? It appears that the principle’s operation was being promoted and applied expansively, whilst section 32(1) was being restricted and minimised – whatever gap there may have been between the two, the French Court sought to narrow it.[215]

As identified earlier, the prominent status of the principle of legality under the French Court may be, in part, a response to the lack of a federal bill of human rights in Australia. However, if this is an underlying reason, then it reveals a great irony. The Victorian Charter protects democratically sanctioned rights and section 32(1) is a statutory command given by Parliament. The function of section 32(1) was ‘to make up for the putative failure of the common law rules’.[216] Indeed, the prevailing view prior to Momcilovic was that section 32(1) was more far reaching in its strength than the principle of legality.[217] Instead, the Victorian Court of Appeal and French CJ used the principle of legality, a judicially sanctioned interpretive principle, to read down section 32(1), a democratically sanctioned interpretive provision.

Post-Momcilovic, the Victorian courts have predominantly interpreted the French Court’s decision as equating section 32(1) with the principle of legality.[218] This seems to be based on the judgment of French CJ. However, doubts have been raised in the academic commentary[219] and by Tate JA of the Victorian Court of Appeal[220] as to the correctness of this interpretation of Momcilovic.[221] It is true that section 32(1) and the principle ‘both require Parliament to express itself particularly clearly if its intention is to override’[222] human rights or fundamental common law protections respectively. But what differences in strength they possess before each is displaced is yet to be authoritatively resolved.

The appointments of Gageler and Keane JJ marked a critical juncture for the principle of legality under the French Court. Their Honours adopted a more contextual (and conservative) approach to the principle of legality.[223] This Part illustrates a divide amongst the Court about the role and weight that should be given to the objects of the statute, where it might be said that those objects are directed at the abrogation or curtailment of the fundamental common law protection. The approach of Gageler and Keane JJ has the effect of relaxing the test for rebuttal by necessary implication.

In X7,[224] the constructional question was whether the Australian Crime Commission Act 2002 (Cth) (‘ACC Act’) authorised compulsory examination of the plaintiff about the subject matter of an indictable offence for which he had been charged and was pending trial.

A majority of the French Court (Hayne and Bell JJ, Kiefel J agreeing) recognised that such questioning would depart from the general system of law ‘in a marked degree’.[225] It would alter a ‘defining characteristic of the criminal justice system’ – namely, its ‘accusatorial nature’.[226] This was ‘critical to the question of statutory construction which must be answered in this case’,[227] and thus attracted the principle of legality.[228] As to whether the principle was rebutted, Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ noted that there were no express words in the ACC Act to depart from the accusatorial nature of the criminal justice system.[229] Hence, the outcome turned upon whether there was a necessary implication.

Hayne and Bell JJ (with Kiefel J agreeing) reiterated that ‘the implication must be necessary, not just available or somehow thought to be desirable’.[230] Previous High Court authority had established that displacement of the principle by necessary implication would only occur to ‘prevent the statutory provisions from becoming inoperative or meaningless’.[231] To determine this, one looks to the purpose of the statute and its provisions. Consistently with this approach, Hayne and Bell JJ considered whether the purpose of the ACC Act and its provisions would be ‘defeated’ if the principle was not otherwise rebutted.[232] The statutory functions of the Australian Crime Commission were the gathering and dissemination of criminal information and intelligence for the purposes of investigating ‘serious and organised’ crime. Hayne and Bell JJ held that the Commission’s investigative function was ‘in no way restricted or impeded if the power of compulsory examination’ did not extend to a person already charged and who was pending trial about the subject matter of that charge.[233] Their Honours, together with Kiefel J, held that the principle of legality was not rebutted by necessary implication.[234]

French CJ and Crennan J dissented. Their Honours found the principle rebutted, by reference to the text of the provisions and existence of safeguards in the ACC Act, the extrinsic materials, and the ‘public interest’ served by the statutory functions of the Australian Crime Commission.[235]

However, the 4:3 decision in Lee,[236] which was decided a few months after X7, calls into doubt the established approach, applied by Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ, to rebutting the principle of legality by necessary implication. As in X7, the appellants had been charged with offences and were awaiting trial. The relevant legislation was the Criminal Assets Recovery Act 1990 (NSW) (‘CAR Act’). The bench included Gageler and Keane JJ. The High Court majority – which now comprised of French CJ and Crennan J (who were in the minority in X7), together with Gageler and Keane JJ – held that the CAR Act permitted the compulsory examination of the appellants about the subject matter of those charges.[237]

A substantial (but not the sole) ground relied upon by the majority to distinguish X7 was the statutory objects under the CAR Act. Here, the objects of the statute and compulsory examination provisions were the identification

and confiscation of profits and proceeds gained from serious crime (which did not require a conviction). The majority took the approach that the clearly identified objects of the CAR Act and its provisions involved the abrogation or curtailment of fundamental criminal process rights, such that the principle of legality was rebutted.[238] For example, Crennan J considered that the purposes of the compulsory examination powers – to identify and confiscate criminal profits and proceeds – ‘subsist irrespective of whether a person has been charged

with ... an offence’ and was pending trial.[239] Gageler and Keane JJ (Crennan J agreeing)[240] stated that the principle of legality:

exists to protect from inadvertent and collateral alteration rights, freedoms, immunities, principles and values that are important within our system of representative and responsible government under the rule of law; it does not exist to shield those rights, freedoms, immunities, principles and values from being specifically affected in the pursuit of clearly identified legislative objects by means within the constitutional competence of the enacting legislature.

The principle of construction is fulfilled in accordance with its rationale where the objects or terms or context of legislation make plain that the legislature has directed its attention to the question of the abrogation or curtailment of the right, freedom or immunity in question and has made a legislative determination that the right, freedom or immunity is to be abrogated or curtailed. The principle at most can have limited application to the construction of legislation which has amongst its objects the abrogation or curtailment of the particular right, freedom or immunity in respect of which the principle is sought to be invoked. The simple reason is that ‘[i]t is of little assistance, in endeavouring to work out the meaning of parts of [a legislative] scheme, to invoke a general presumption against the very thing which the legislation sets out to achieve’.[241]

French CJ accepted that ‘[w]here the public policy of a statute and its purpose are identified with sufficient clarity, the option of making a constructional choice protective of common law rights may be precluded’.[242] Nevertheless, this comment did not go as far as the approach of Gageler and Keane JJ. French CJ did not say that the principle of legality will always be of little assistance if the statutory objects are abrogation or curtailment of fundamental common law protections. Sometimes, even despite the statutory purpose, there will still be constructional choice. French CJ would adopt a ‘least infringing’ approach, whereby the correct construction is that which least interferes with fundamental common law protections within the range (if any) of possible constructions.[243] This distinction in approach between French CJ, and Gageler and Keane JJ, is made clearer in NAAJA, discussed below.

The majority’s finding in Lee that the principle of legality was rebutted was stridently criticised on several fronts by the minority, which now comprised Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ – a reversal from X7. First, Hayne J opined that ‘no relevant distinction’ had been identified between the two statutory schemes,[244] and ‘[a]ll that has changed ... is the composition of the Bench’.[245] Secondly, the minority judges criticised the majority for ‘assuming’ the answer to the ‘central question’, namely, that the authorisation of compulsory powers extended to situations where an accused is pending trial.[246] The CAR Act implied nothing to that effect. Thirdly, as Kiefel and Bell JJ observed, the objects would not be ‘frustrated’ (ie, the statute rendered inoperative or meaningless)[247] by the delay in confiscating profits and proceeds until after the concurrent criminal proceedings against the appellants had been concluded.[248]

Whilst it is open to debate whether the majority decisions in X7 and Lee are contradictory, or whether they can be justified on the basis of their respective statutory contexts,[249] the former view is the correct one.[250] In particular, the approach of Gageler and Keane JJ represents a less stringent approach than what was once thought required to rebut the principle by necessary implication. On the previous approach, one must consider whether the provision would be rendered ‘inoperative or meaningless’[251] by reference to purpose. But on the approach of Gageler and Keane JJ, if it is considered that the objects of the legislation are to infringe fundamental common law protections, then the principle of legality has little effect.

Gageler J maintained his approach in NAAJA.[252] One will recall that Gageler J dissented in finding that police had a discretion under the Police Administration Act 1978 (NT) to detain a person for certain minor offences without a warrant for any period up to a maximum of four hours. In his Honour’s view, the principle of legality was rebutted. This was based partly on the text of the operative provisions, but also on the statutory objects. In respect of the latter, Gageler J considered that the principle of legality was ‘of little assistance given that the evident statutory object is to authorise a deprivation of liberty and that the statutory language in question is squarely addressed to the duration of that deprivation of liberty’.[253]

On the other hand, French CJ, Kiefel and Bell JJ adopted a ‘least infringing’ approach to the principle of legality. Their Honours searched for ‘a construction, if one be available, which avoids or minimises the statute’s encroachment upon fundamental principles, rights and freedoms at common law’.[254] Hence, their Honours favoured a construction that a person could be detained only for so long as is reasonable within the maximum of four hours. Their Honours responded directly to Gageler J’s position and rejected it. The principle of legality:

is not to be put to one side as of ‘little assistance’ where the purpose of the relevant statute involves an interference with the liberty of the subject. It is properly applied in such a case to the choice of that construction, if one be reasonably open, which involves the least interference with that liberty.[255]

If the position of Gageler and Keane JJ in Lee and Gageler J in NAAJA were to eventually gain traction, this would represent a significant relaxation to rebutting the principle of legality by necessary implication. It would also have ramifications when the exact extent to which a provision infringes a fundamental common law protection is unclear. If a range of constructions is available, including a more restrictive, rights-protective construction, the principle of legality is unlikely to help where the statutory objects are abrogation or curtailment of that fundamental common law protection.[256]

Another contestable issue is the relevance of extrinsic materials. The question is to what extent may extrinsic materials be relied upon to demonstrate Parliament’s intention to abrogate or curtail fundamental common law protections. This Part demonstrates that the predominant view of the French Court was that extrinsic materials are given little weight in the context of the principle of legality. This is neither new nor inappropriate, when regard is had to the principle’s operation. Gageler J, however, took a different view.

Perhaps the real controversy with Saeed (where the natural justice hearing rule was not excluded for offshore visa applicants),[257] which also played a part in Lacey (where the discretion of an appellate court to vary a sentence still required an error),[258] was that the French Court endorsed a construction protective of fundamental common law protections despite extrinsic material which was clearly to the contrary. For example, in Saeed five members of the Court said: ‘Statements as to legislative intention made in explanatory memoranda or by Ministers, however clear or emphatic, cannot overcome the need to carefully consider the words of the statute to ascertain its meaning’.[259]

Louise Clegg considered that this eschewing of extrinsic materials with respect to the principle of legality is ‘a move by the Court back towards literalism in statutory interpretation’.[260] Dan Meagher has observed that there has been a reassertion of the primacy of the statutory text, but particularly in respect of the principle of legality, a strict textualism has emerged[261] ‘to the exclusion of near all else’.[262] The principle of legality has trumped legislative history.[263] It is true that the French Court has sought to emphasise the primacy of the text when interpreting legislation. Certain commentators have suggested that extrinsic materials should be sufficient – perhaps even more so than the legislative text – to demonstrate Parliament’s intention to abrogate or curtail fundamental common law protections.[264] Yet given the emphasis on legislative text, courts generally are cautious or reluctant to utilise such materials in this way.[265] This caution or reluctance is not a new development under the French Court.

In Lacey, the French Court did controversially determine that the concept

of legislative intention is a product of the statutory interpretation process

itself, rather than something that is pre-existing and subsequently ascertained through the statutory interpretation process.[266] This questions the authenticity

of legislatures having intentions,[267] and perhaps also the argument that such intentions are reflected in extrinsic materials.

But even before this notion gained favour, the approach was that legislative intention involved ascertaining the objective intention of Parliament, rather than the subjective intention of, for example, an individual Minister or parliamentarian.[268] Therefore, ‘[t]he words of the statute, not non-statutory words seeking to explain them, have paramount significance’.[269] Where the words are clear and unambiguous, extrinsic materials cannot be used to displace them.[270] Conversely, extrinsic materials cannot be used to supply clear meaning to the text in order to abrogate or curtail fundamental common law protections.[271] So much was recognised in the principle of legality case of Re Bolton; Ex parte Beane,[272] where Mason CJ, Wilson and Dawson JJ said that a Minister’s words ‘must not be substituted for the text of the law’.[273] Such principles continued to be applied by the French Court in Lacey.[274]

That is not to say that extrinsic materials have been completely excluded when the principle of legality is being considered. French CJ and Crennan J were both part of the majority in Lacey. But in X7, their Honours made reference to the extrinsic materials, saying there was ‘nothing’ which ‘throws any doubt on the conclusion, based on the text and purpose of the provisions’ that the compulsory examination powers under the ACC Act can be exercised after charges have been laid.[275] In Lee, Crennan J referred not only to the expressly stated objects of the CAR Act, but also the second reading speech in identifying that Act’s purpose, before going on to find that applying the principle of legality would frustrate the Act’s objects.[276] In these cases, extrinsic materials were used by their Honours as supportive, rather than determinative, factors for rebuttal of the principle – an outcome which they would have likely reached in any event.

Meagher has questioned the coherence of ‘privileging’ the principle of legality over extrinsic materials.[277] Both sit external to the statute.[278] Moreover, he has noted that in general statutory interpretation, where the principle of legality is not engaged or at issue, extrinsic materials are used liberally.[279] Elsewhere, the French Court has unanimously said that ‘[t]he statutory text must be considered in its context. That context includes legislative history and extrinsic materials’.[280] With respect to the principle of legality though, extrinsic materials hold lesser weight. Meagher has argued that this ‘might be justified if the principle of legality is understood as a quasi-constitutional clear statement rule the application of which to legislation vindicates important Australian constitutional principles and values’.[281] But the principle of legality need not go so far.

Its modus operandi is that intention for rebuttal must be ‘manifested’[282] or ‘express[ed]’[283] in clear and unambiguous language in the statute. Where resort is necessary to extrinsic materials, this is indicative that the requisite language is lacking.

Gageler J in NAAJA took a different approach to Saeed and Lacey. As discussed above, Gageler J dissented on the basis that the ‘evident statutory object’[284] of the legislation was to infringe a fundamental common law protection. His Honour identified this object by reference to extrinsic materials.[285] By contrast, while French CJ, Kiefel and Bell JJ referred to extrinsic materials, their Honours did so only for the question of constitutional validity of

the legislation.[286] Their Honours did not refer to the extrinsic materials when considering the operation of the principle of legality. The remainder of the majority, Nettle and Gordon JJ, expressly rejected giving weight to the extrinsic materials,[287] citing Re Bolton; Ex parte Beane.

The contrasting approaches of the majority, and Gageler J in the minority, reflect a difference in attitude towards extrinsic materials in the context of the principle of legality. It also reflects a more recent divergence regarding the use of extrinsic materials in statutory interpretation generally to identify the statute’s object. In Gageler J’s view, extrinsic materials can freely be used to ascertain purpose. By contrast, the predominant approach of the French Court is far more cautious – ‘[t]he purpose of a statute is not something which exists outside the statute. It resides in its text and structure’.[288] Despite such language,[289] once again this has not led to complete exclusion of extrinsic materials under the principle of legality[290] or in general statutory interpretation.[291] Nevertheless, it is fair to say that for the purposes of rebutting the principle of legality, the predominant approach very much de-emphasises the identification of statutory objects by reference to extrinsic materials. In NAAJA, the majority did not even consider them relevant.

Gageler J’s approach to the use of extrinsic materials can be linked to Gageler and Keane JJ’s approach to statutory objects, which is in turn linked to a less robust principle of legality. Gageler J considers it permissible to rely heavily on extrinsic materials to identify a statutory object, and if those materials make clear that the object is to abrogate a fundamental common law protection, then the principle of legality has little (if any) role to play. On the other hand, according to the majorities in Lacey and NAAJA, identification of a statutory object is predominantly text-based, and rebuttal of the principle of legality is also text-based. Even where the statutory object according to the text is to abrogate a fundamental common law protection, but the text leaves constructional choices open, there is still work for the principle of legality to do, with a ‘least infringing’ construction being adopted.

There is a further, related issue with respect to extrinsic materials: where the legislation is enacted in jurisdictions which provide for a pre-legislative scrutiny process against human rights standards. Can ‘statements of compatibility’ influence the operation of the principle of legality?

As part of the human rights frameworks provided by the Victorian Charter and the Australian Capital Territory’s Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT), what are known as ‘statements of compatibility’ are to be prepared for Parliament when a Bill is introduced.[292] This is usually by the relevant Minister or the Attorney-General.[293] The statement of compatibility must state whether, in that person’s opinion, the Bill is compatible with human rights; or if the Bill is not compatible with human rights, how it is not.[294] At the federal level, a standalone scrutiny process has been enacted under the Human Rights (Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth).[295] Statements of compatibility prepared for Commonwealth Bills[296] are measured against seven major international human rights treaties,[297] rather than domestically incorporated human rights.

There is a possibility that statements of compatibility, as extrinsic materials,[298] may influence statutory interpretation.[299] Taken further, the analysis in statements of compatibility could potentially affect the operation of the principle of legality. Where there is an overlap between a human right and a fundamental common law protection, and a statement of compatibility considers the human right, the question is whether this can be relied on to find that Parliament intended (or conversely, did not intend) to abrogate or curtail the equivalent fundamental common law protection.

This issue has yet to be decided by the High Court. It was raised solely by Gageler J in R v IBAC.[300] As we have seen from NAAJA, his Honour is willing to give significant weight to extrinsic materials.

R v IBAC was another case about the common law privilege against self-incrimination and compulsory examination powers (further to X7 and Lee) – this time pursuant to Victorian legislation. Gageler J considered that the statement of compatibility to the relevant Bill[301] ‘explained the balance struck ... to be compatible with’ the human right not to be compelled to testify against himself or herself or to confess guilt, ‘in part by reference to the express abrogation of the privilege against self-incrimination’.[302] His Honour expressed concerns about resort to the principle of legality where the legislation has been developed within a human rights framework. Gageler J said:

An interpretative technique which involves examining a complex and prescriptive legislative scheme designed to comply with identified substantive human rights norms in order to determine whether, and if so to what extent, that legislative scheme might butt up against a free-standing common law principle is inherently problematic.[303]

Not dissimilarly, the Solicitor-General for Victoria, Richard Niall QC,

has suggested that an ‘over-zealous reliance’ on the principle of legality

‘fails to recognise that legislation today is often about the balance between

rights and interests and the application of the principle may distort the

balance that Parliament has struck’.[304] While it is arguable that the principle of legality inherently does, or should, involve justification and proportionality considerations,[305] the predominant judicial viewpoint is that such considerations have no role to play.[306] This can be contrasted with bills of human rights, such as the Victorian Charter, which ‘provides a clear and effective framework for considering the limits that may be placed on human rights, having regard to competing public interests and policy objectives’.[307]

The reliance on statements of compatibility by the lower courts is

relatively rare and has been mixed.[308] But since the dicta of Gageler J in

R v IBAC, it appears the Victorian courts have become more willing to give weight to them.[309] Nevertheless, statements of compatibility are not binding on

courts and tribunals.[310] They represent the subjective intention of a Minister or parliamentarian introducing a Bill, rather than any actual intention of Parliament. Based on past practice, it seems unlikely that the High Court (Gageler J aside) would greatly rely on a statement of compatibility so as to affect the principle of legality’s operation.