University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE HIGH COURT ON CONSTITUTIONAL LAW: THE 2017 STATISTICS

ANDREW LYNCH[*] AND GEORGE WILLIAMS[**]

This article presents data on the High Court’s decision-making in 2017, examining institutional and individual levels of unanimity, concurrence and dissent. It does so in the context of the elevation of a new Chief Justice to lead the Court and the appointment of a new member to the bench at the commencement of the year. Recent public statements on the Court’s decision-making practices by the new Chief Justice and others inform discussion of the statistics. This article is the latest instalment in a series of annual studies conducted by the authors since 2003.

This article reports the way in which the High Court as an institution and its individual judges decided the matters that came before them in 2017. The year was a significant one in the Court’s history as it entered a new era under a new Chief Justice. Susan Kiefel is only the 13th incumbent of that office and the first woman to be sworn in as the leader of the High Court of Australia.

The year was notable in other respects. Justice James Edelman began his service on the High Court. At age 43, he is the youngest person appointed to its bench since 1930 and the fourth youngest ever. Accordingly, 2017 may be the first year of a judicial career on the Court that will continue until Justice Edelman reaches the mandatory retirement age of 70 years in 2043. Should Justice Edelman retire then and not before, he will have enjoyed the longest tenure of any justice appointed since the introduction of the age limit of 70 years by constitutional amendment in 1977.[1]

Changes such as this to the personnel of the High Court are a particular focus in this ongoing annual study of High Court decision-making.[2] In this series, which began in 2003, all the Court’s decisions and the subset of constitutional matters decided in each calendar year are examined not simply to report how the institution has responded to the cases that came before it but also to identify patterns in the decision-making of its individual members relative to each other. The formation, consistency and occasional decline of regular coalitions between the Justices, as well as the Court’s experience of disagreement between its members, are reported on and analysed.

The results presented in this article have been compiled using the same methodology that underpins others in this series.[3] The limitations of an empirical study of the decisions of any final court over the space of a single calendar year, particularly so in respect of the constitutional cases which comprise a small portion of the High Court’s caseload, are expressly acknowledged. However, as we have also regularly observed, there is a long tradition of annual studies of the decision-making in final courts, most notably that of the United States Supreme Court in the Harvard Law Review.[4] These enable specific developments to be tracked that may emerge as trends over the longer term, while also providing contemporary audiences a real-time account of how the Court and its members are working with each other to resolve current controversies.

The annual timeframe of these studies is particularly useful in scrutinising changes in approach when leadership of the Court passes from one Chief Justice to another. On this occasion, it is reasonable to anticipate a smooth transition from the era of Chief Justice French to that of Chief Justice Kiefel given the strength of their respective commitment to the High Court’s distinctive practice of ‘joining in’ to produce a single set of reasons for a number of judges.[5] In our 2017 article, we quoted from accounts of that process given by both Chief Justices.[6] Significantly, Chief Justice Kiefel’s first major address after her swearing in was to once again describe and justify this practice and emphasise the benefits it provides of institutional coherence and certainty. Her oration, titled ‘Judicial Methods in the 21st Century’, is probably the most detailed public account of the High Court’s decision-making process given by a serving Chief Justice. In it she revealed:

A first draft judgment is circulated to the other justices in order to ascertain if those of like view will agree with it. Agreement is expressed by the circulation of a judgment which states little, if anything, more than the fact of agreement with the reasons and the orders proposed. That justice is then usually ‘joined in’ to the first draft, with his or her consent. The justice’s name appears on the judgment with that of the author. If others agree they too are joined in.

Although a judgment is called the ‘judgment of the Court’ when all justices agree, or a ‘joint judgment’ (or, more controversially, a ‘judgment of the plurality’) when a number agree, it is more often the case that there is only one author. Whilst it is not unusual for suggestions, sometimes substantial in content, to be made to the author of the first draft, it is not often the case that two or more justices will work together to produce a judgment.

Suggested changes to the first draft after its circulation are usually contained in a memorandum, in which an explanation is given for the changes. It would not be usual to suggest a change in its essential reasoning or a substantial re-writing of it, although suggestions may nevertheless be of significance. The author of the first draft is not obliged to accept any proposed changes.

The effect of the High Court’s practice of ‘joining in’ is to render the author largely anonymous. Some might argue that a reader should know who the author is, although it is difficult to see what the benefit of that knowledge could be. On occasions a justice might wish the practice was otherwise, when it is felt that he or she has written a particularly good judgment, but it is always understood that if the practice were not followed justices would be encouraged to write separately more often, which is what the practice seeks to avoid.[7]

This passage is worth recording at length given its relevance to the larger project of which this article forms a part. This is so in key respects. First, it appears no longer accurate to refer to joint judgments as ‘co-authored’ and so in this article, and for any future studies, we discard that term in favour simply of ‘joining’ a judgment. Second, the passage expressly confirms a point we have always been careful to acknowledge: that individual influence should not be lightly assumed merely because some members of the Court participate in majority coalitions, especially joint opinions, with high frequency. As Chief Justice Kiefel said some years before her elevation, ‘[a] judge whose judgments are more often than not agreed in by his or her colleagues will not necessarily achieve the recognition or reputation of other judges. This may result in a misconception about influence’.[8]

In 2017, a publication appeared in which researchers used linguistic profiling software so as to identify the principal author of joint reasons delivered on the High Court under Chief Justice Anthony Mason.[9] In its title, the article directly referenced Kiefel J’s observation about the anonymity of the principal author that attends the High Court’s practice of ‘joining in’ and so signalled that it was written, at least in part, by way of response. In launching the journal issue in which that article appeared, Justice Virginia Bell decried the enterprise embarked on by the authors and defended the Court’s practice:

The results of the study by Partovi and his colleagues are introduced with Andrew Lo’s statement that ‘[o]bscuring authorship removes the sense of judicial accountability, making it harder for experts and the public alike to understand how important issues were resolved and the reasoning that led to these decisions’. With respect, this strikes me as peculiar obduracy on the part of the Academy: the names of all of the judges who subscribe to the judgment are set out above it and each judge accepts responsibility for all that appears under his or her name. To trespass on the language of management, the process is both transparent and accountable. And as for understanding how the important issues were resolved, the answer lies in the reasoned judgment.[10]

This echoes Chief Justice Kiefel’s insistence that the ‘opinion of a judge is revealed to the world by the publication of a judgment in his or her name’.[11]

More generally, Chief Justice Kiefel has continued to extol the benefits of ‘fewer individual judgments’ and even the production where possible of a ‘single majority judgment’.[12] She cites their attraction as providing clarity, authority, instilling confidence in the Court’s decision and the avoidance of delay caused by the need to allow time for the filing of multiple judgments.[13] By contrast, the individual opinion, more relevantly concurrences rather than dissents, may diminish these benefits. For these opinions, Chief Justice Kiefel has appeared to endorse the term ‘vanity judgment’ coined by Lord Neuberger, the former President of the United Kingdom Supreme Court.[14] He explained:

By that I mean a judgment which is intended to agree with the lead judgment, but not to add anything other than saying ‘I have understood this case’ or ‘I think I can express it better’ or ‘I am interested in this point’ or simply ‘I am here too’.[15]

With the Chief Justice having expressed such clear views at the outset of her tenure on the institutional responsibilities of judges on a multi-member court and an aversion to individualism that may amount to mere vanity, there is no question that it remains vital to look at how the High Court decides the cases that come before it. In doing so, it helps to have some questions in mind. Does what is happening in practice accord with the views expressed by Chief Justice Kiefel? Or does it instead show that the aspiration of judicial collaboration may nevertheless prove elusive? Is it possible that the differences between individual justices that are observable in these results reflect diverse, possibly competing, perspectives on the judicial role in a multi-member court?[16]

As with earlier entries in this series, this article examines not only all the High Court’s decisions in total over the preceding year but separates out those which feature constitutional issues for distinct examination. The reasons for doing so stem from the importance and often high-profile public attention these decisions receive, and also because members of the Court have made clear that constitutional matters tend to be especially challenging in securing agreement between the Justices. Chief Justice Kiefel once acknowledged this was due ‘in large part because novel questions are presented and it is necessary for a judge to work through them, and that may require writing a complete judgment’.[17] Sir Anthony Mason once made the candid remark that differences of opinion as to questions of precedent in respect of common law matters do ‘not have the same potential to affect personal relations or to inhibit the prospect of judicial cooperation as judicial disagreement in its application to constitutional interpretation’.[18] Accordingly, the structure of these annual studies has always included a discrete examination of constitutional matters in decision-making by the Court.

TABLE A: High Court of Australia Matters Tallied for 2017

|

|

Unanimous

|

By Concurrence

|

Majority over Dissent

|

TOTAL

|

|

All Matters Tallied for Period

|

18 (35.29%)

|

17 (33.33%)

|

16 (31.37%)

|

51 (100%)

|

|

All Constitutional Matters

Tallied for Period

|

5 (45.45%)

|

4 (36.36%)

|

2 (18.18%)

|

11 (100%)

|

A total of 51 matters were tallied for 2017. Fifty-six cases appear on the AustLII High Court database for the year.[19] As the Appendix explains, six of these were excluded due to being decided by a single Justice sitting alone and one was tallied twice in accordance with our standard methodology for cases comprised of distinct matters.

The manner in which the 51 matters were decided was almost evenly distributed between unanimous judgment (35.29 per cent), by separate concurring opinions (33.33 per cent), and by majority over dissent (31.37 per cent). The percentage of matters decided by concurrence was 10 percentage points less than in the previous year, while correspondingly, the proportion of matters resolved either unanimously or over dissent both modestly increased. This represents the continuation of what was observed of the Court’s decisions of 2016: a reduction of the number of cases decided by concurrence (which was over 56 per cent of all cases in 2015) by increases in both unanimous decisions and those where a minority opinion was delivered.

Eleven of the 51 matters tallied for 2017 – or 21.57 per cent – were constitutional in character. The definitional criteria that determines our classification of matters as ‘constitutional’ remains:

that subset of cases decided by the High Court in the application of legal principle identified by the Court as being derived from the Australian Constitution ... That definition is framed deliberately to take in a wider category of cases than those simply involving matters within the constitutional description of ‘a matter arising under this Constitution or involving its interpretation’.[20]

Our only amendment to this statement as a classificatory tool has been to additionally include any matters before the Court involving questions of purely state or territory constitutional law.[21] There were no matters in 2017 that came within this additional aspect of the criteria.

In 2016, only 14.29 per cent of the matters decided by the Court were classified as having a constitutional dimension – not the lowest representation of constitutional issues in a single year since we began this annual survey, but very close to it. By contrast, 2017 saw a significant increase in the Court’s consideration of constitutional questions, assisted by the high-profile controversies of parliamentary disqualification that were heard by the High Court sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns. Four such matters are included in the tally of constitutional cases in this study.[22]

The inclusion of matters decided by the Court of Disputed Returns accounts only in part for the unusual breakdown of the way in which the constitutional matters were resolved in 2017. Of the 11, five were decided unanimously, four by concurrence and just two featured a dissenting opinion. Not since 2010 has there been more than one constitutional matter decided unanimously. The first two years of Chief Justice French’s tenure featured exceptionally high rates of unanimity generally and this translated to two unanimous constitutional cases in 2009 and three in 2010. However, in both those years, more constitutional matters were decided with a dissenting opinion than either unanimously or by concurrence. In 2003, the subject of our inaugural annual study, the Gleeson Court decided three constitutional matters unanimously, but it also decided six with a minority opinion. Against this background, the delivery of five unanimous constitutional judgments in 2017 is remarkable. It may be that the nature of some of those matters as ones heard by the Justices sitting as the Court of Disputed Returns is a relevant factor, with the desirability of a relatively swift decision possibly being conducive to greater judicial collaboration. That not implausible supposition is, however, not strongly supported by the 2017 cases since only two of the four were decided unanimously, and one was decided by four concurring opinions.[23]

The effect of this surge in consensus in constitutional matters is even better appreciated through the lens of dissent. Although in 2003, 2009 and 2010 the High Court was unanimous in more constitutional cases than usual, those in which dissent occurred remained prevalent. In 2017, the high unanimity led to a very low incidence of constitutional dissent – just two matters in which there was a minority view as to the outcome. With such matters accounting for 18.18 per cent of those decided, 2017 saw the least amount of explicit disagreement in constitutional law since this annual series was commenced.

TABLE B(I): All Matters – Breakdown of Matters by Resolution and Number of Opinions Delivered[24]

|

Size of Bench

|

Number of Cases

|

How Resolved

|

Frequency

|

Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered

|

||||||

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

||||

|

7

|

17

(33.33%)

|

Unanimous

|

4 (7.84%)

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

8 (15.69%)

|

|

3

|

3

|

1

|

|

|

1

|

||

|

6:1

|

2 (3.92%)

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:2

|

2 (3.92%)

|

|

|

|

1

|

1

|

|

|

||

|

4:3

|

1 (1.96%)

|

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

|

||

|

6

|

2

(3.92%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (1.96%)

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:1

|

1 (1.96%)

|

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:2

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

3:3

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5

|

28

(54.90%)

|

Unanimous

|

9 (17.65%)

|

9

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

9 (17.65%)

|

|

6

|

3

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:1

|

10 (19.61%)

|

|

3

|

6

|

1

|

|

|

|

||

|

3:2

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

3

|

4

(7.84%)

|

Unanimous

|

4 (7.84%)

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

2:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

TABLE B(II): Constitutional Matters – Breakdown of Matters by Resolution and Number of Opinions Delivered[25]

|

Size of Bench

|

Number of Cases

|

How Resolved

|

Frequency

|

Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered

|

||||||

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

||||

|

7

|

8

(72.73%)

|

Unanimous

|

4 (36.36%)

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

2 (18.18%)

|

|

|

1

|

1

|

|

|

|

||

|

6:1

|

1 (9.09%)

|

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5:2

|

1 (9.09%)

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

|

|

||

|

4:3

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5

|

3

(27.27%)

|

Unanimous

|

1 (9.09%)

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

By concurrence

|

2 (18.18%)

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4:1

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

3:2

|

–

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Tables B(I) and (II) reveal several things about the High Court’s decision-making over 2017. First, they present a breakdown of, respectively, all matters and then just constitutional matters according to the size of the bench and how frequently it split in the ways open to it. Second, the tables record the number of opinions which were produced by the Court in making these decisions. This is indicated by the column headed ‘Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered’. Immediately under that heading are the figures 1 to 7, which are the number of opinions which it is possible for the Court to deliver. Where that full range is not applicable, shading is used to block off the irrelevant categories. Readers should note that the figures given in the fields of the ‘Cases Sorted by Number of Opinions Delivered’ column refer to the number of cases containing as many individual opinions as indicated in the heading bar.

These tables should be read from left to right. For example, Table B(I) tells us that of the two matters heard by a six-member bench, one was decided 5:1 and featured four sets of reasons. In this way, Table B(I) enables us to identify the most common features of the cases in the period under examination. The ‘most typical’ method by which a matter was resolved in 2017 was for a five-judge bench to decide 4:1. However, almost as many cases were decided by a bench of the same size either unanimously or by concurring judgments. This near parity of the three ways in which this largest subset of cases was decided reflects that of the 2017 matters generally.

In light of the admonition of those who might indulge in the delivery of ‘vanity judgments’, it is appropriate to acknowledge that these tables may be used to point out a proliferation of concurrences (though of course whether the judgments in question meet the relevant criteria outlined by Lord Neuberger must always require a substantive assessment). Only one case in 2017 featured as many opinions as there were sitting judges: Kendirjian v Lepore.[26] This was in performance of the High Court’s ‘welcome case’ tradition whereby a new justice writes the lead opinion and others separately deliver a brief concurrence.[27] On this occasion the newcomer was Edelman J, and while the tradition was essentially observed, it was not done so as seamlessly as on earlier occasions.[28] Both Nettle and Gordon JJ delivered more than a bare concurrence and made plain their adherence to views both had expressed in an earlier decision.[29]

Interestingly, in the case of Talacko v Bennett,[30] Gageler J delivered a one-line concurrence agreeing with the reasons of the joint judgment and the separate observations of Nettle J. Outside of ‘welcome cases’, such brief concurrences are very rare indeed in the Court’s modern era. They certainly cannot be described as a ‘vanity judgment’.

There were only three matters in 2017 that met the description of a ‘close call’ – that is, a case decided over a minority of more than one Justice.[31] Of those, just one came down to a single vote: Hughes v The Queen,[32] decided 4:3.

It should also be noted that the Court heard four cases with a bench of just three Justices in 2017. All four were appeals from the Supreme Court of Nauru and were decided unanimously.

Table B(II) records the same information in respect of the subset of constitutional cases. While eight of these cases were decided by all seven Judges, three were determined by a five-member bench. The most common format for the resolution of a constitutional case was a unanimous seven-judge decision – with four of the 11 matters decided in this way. Only one of these was a matter relating to parliamentary disqualification heard by the Court as the Court of Disputed Returns – the case of Re Canavan in which the fate of no fewer than seven parliamentarians was at stake.[33] The other three matters were Knight v Victoria,[34] Plaintiff S195/2016 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection,[35] and Wilkie v Commonwealth.[36] Brown v Tasmania was the constitutional matter with the most separate opinions (five) and also the only ‘close call’ constitutional case, being decided 5:2.[37]

TABLE C: Subject Matter of Constitutional Cases

|

Topic

|

No of Cases

|

References to Cases

(Italics indicate repetition)

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

45

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

45

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

2

|

45, 52

|

|

|

1

|

4

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

14

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

2

|

45, 52

|

|

|

1

|

52

|

|

|

1

|

40

|

|

|

1

|

40

|

|

|

1

|

40

|

|

|

1

|

23

|

|

|

1

|

33

|

|

|

1

|

33

|

|

|

1

|

33

|

|

|

1

|

40

|

|

|

1

|

40

|

|

|

Ch III

|

2

|

5, 29

|

|

Implied Freedom of Political Communication

|

1

|

43

|

|

State Courts, Kable principle

|

1

|

29

|

|

Whether Australian Constitution denies Commonwealth legislative or

executive power to authorise or to take part in activity in another country that

is unlawful under

domestic law of that country.

|

1

|

31

|

Table C lists the provisions of the Australian Constitution, as well as the state constitutional law issue, that arose for consideration in the 11 constitutional law matters tallied for 2017. It is assembled by reference to the catchwords accompanying each decision.

The list of constitutional provisions and issues considered in the matters of 2017 is unusually long. This owes much to Re Nash [No 2], in which no fewer than 15 provisions are identified in the catchwords as arising for consideration.[38]

TABLE D(I): Actions of Individual Justices: All Matters

|

|

Number of Judgments

|

Participation in Unanimous Judgment

|

Concurrences

|

Dissents

|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

45

|

14 (31.11%)

|

31 (68.89%)

|

–

|

|

Bell J

|

40

|

13 (32.5%)

|

26 (65.00%)

|

1 (2.50%)

|

|

Gageler J

|

40

|

10 (25.00%)

|

24 (60.00%)

|

6 (15.00%)

|

|

Keane J

|

44

|

17 (38.64%)

|

26 (59.09%)

|

1 (2.27%)

|

|

Nettle J

|

45

|

15 (33.33%)

|

25 (55.56%)

|

5 (11.11%)

|

|

Gordon J

|

35

|

9 (25.71%)

|

23 (65.71%)

|

3 (8.57%)

|

|

Edelman J

|

34

|

13 (38.24%)

|

17 (50.00%)

|

4 (11.76%)

|

Table D(I) presents, in respect of each Justice, the delivery of unanimous, concurring and dissenting opinions in 2017. Owing to the timing of Chief Justice French’s departure, the elevation of Chief Justice Kiefel and the arrival of Justice Edelman in late January, the Court’s membership was consistent over the year, assisting in any direct comparison between Justices. However, as is well understood, not all judges sit on all cases and this differentiates the total number of opinions each delivers. Last year, the Chief Justice and Nettle J delivered the most opinions, 45 of the full tally of 51 matters, and Edelman J delivered the least, with 34 opinions (this is due to the carrying over of some cases from hearings in the preceding year prior to his taking office). With the Justices not all sitting on exactly the same matters, inevitably the opportunities for unanimity or disagreement are varied.

In the first year of the ‘Kiefel Court’, the Chief Justice was the only member not to file a minority opinion. Bell and Keane JJ, neither of whom issued a dissent in 2016, did so once each in 2017 (not in the same case).

Gageler J wrote the most dissents, with 15 per cent of all his decisions being a minority view. The last year in which Gageler J had the highest rate of dissent in cases overall was 2014 – where the same number of dissenting opinions as in 2017 (six in total) accounted for 18.60 per cent of all judgments he delivered. In 2016, the leading dissenter was Gordon J, also with six minority opinions which represented just over 15 per cent of her decisions. She dissented on three occasions in 2017. Last year also saw two other Justices – Nettle and Edelman JJ – issue more than 10 per cent of their decisions in dissent.

Interestingly, no joint dissents were issued at all and, as already noted, in only three cases was there more than a single dissenter. In addition to the 4:3 decision of Hughes v The Queen,[39] these were IL v The Queen[40] and Brown v Tasmania.[41] Of all those who dissented last year, only Gordon J was never alone in minority.

It seems fair to say that dissent remains fluid on the contemporary High Court. There is no single member who may reliably be anticipated to provide a minority or alternative voice. This has been the case since 2015, marking a break with the trend of preceding years in which the role of ‘dissenter’ was predominantly played by a specific individual on the Court.

The current lack of a habitual dissenter amongst the Court’s ranks – with a popular reputation as such and perhaps also a tendency to voice their regular opposition to the majority opinion in a forthright tone[42] – makes it somewhat curious that a topic addressed by the new Chief Justice in her first year should be ‘Judicial Courage and the Decorum of Dissent’.[43] Using Lord Atkin’s famous dissent in the wartime English case of Liversidge v Anderson as her cornerstone,[44] Chief Justice Kiefel dismissed the idea that judges display courage by disagreeing with their colleagues.[45] She proceeded to consider matters of style before concluding:

The work of these [final appellate] courts requires a level of collegiality for the efficient discharge of their work. But in the end it is the court as an institution which matters most, not the hurt feelings of judges. A judgment which ridicules other members of the court cannot but detract from the authority of the court and the esteem in which it is held. A humorous dissent may provide the author with fleeting popularity, but it may harm the image the public has of the court and its judges.[46]

It is not, of course, an objective of this article or the longitudinal series of which it is a part, to examine the substance or style of judicial disagreement. Instead, these studies aim to highlight issues of frequency and source. But the attention given by the Chief Justice to the topic of dissent is worth noting, especially given its relationship to her other public statements about judicial decision-making and the desirability of the Court’s institutional authority and reputation taking precedence over considerations that are more particular to its judicial members as individuals.

TABLE D(II): Actions of Individual Justices: Constitutional Matters

|

|

Number of Judgments

|

Participation in Unanimous Judgment

|

Concurrences

|

Dissents

|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

11

|

5 (45.45%)

|

6 (54.55%)

|

–

|

|

Bell J

|

10

|

5 (50.00%)

|

5 (50.00%)

|

–

|

|

Gageler J

|

11

|

5 (45.45%)

|

6 (54.55%)

|

–

|

|

Keane J

|

11

|

5 (45.45%)

|

6 (54.55%)

|

–

|

|

Nettle J

|

10

|

4 (40.00%)

|

6 (60.00%)

|

–

|

|

Gordon J

|

9

|

4 (44.44%)

|

4 (44.44%)

|

1 (11.11%)

|

|

Edelman J

|

9

|

5 (55.56%)

|

2 (22.22%)

|

2 (22.22%)

|

Table D(II) records the actions of individual Justices in the eleven constitutional matters tallied for 2017. Three Justices heard all 11 of those matters, while two each heard 10 and nine respectively. As already noted, the Court decided an unprecedented percentage of these constitutional matters by unanimous opinion.

The only dissentients were, perhaps surprisingly, the two Justices who sat on the fewest number of constitutional matters. Edelman J, in his first year on the Court, led constitutional disagreement with two dissenting opinions – Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection,[47] in which he differed from a single opinion of the rest of the bench on the question of the implied constitutional constraint upon the Commonwealth Parliament’s ability to restrict judicial review, and Brown v Tasmania,[48] concerning the implied constitutional freedom of political communication. Gordon J filed her only dissent in a constitutional matter in the latter case.

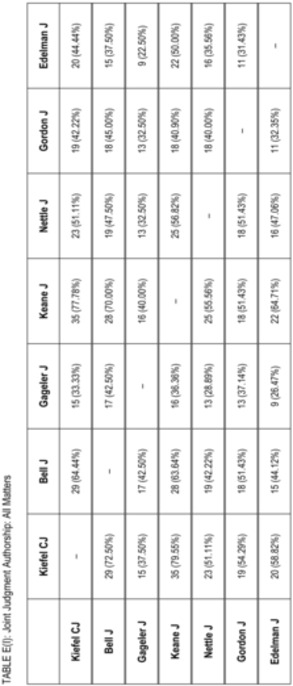

Tables E(I) and E(II) indicate the number of times a Justice joined in an opinion with his or her colleagues. These tables should be read horizontally as the percentage results vary depending on the number of judgments each member of the Court delivered over the year. As mentioned earlier, that Justices do not necessarily sit with each other on an equal number of occasions must be noted as a factor that limits opportunities for some pairings to collaborate more often – most relevantly in 2017 this was so for Gordon and Edelman JJ. However, the fact that the High Court’s membership did not change after January means that the variation in sittings between the Judges is not especially marked.

Turning to E(I) first and looking at the totality of matters for 2017, the most frequent collaboration across all cases of 2017 was between Kiefel CJ and Keane J, with them joining in 77.78 per cent of her decisions and 79.55 per cent of his. The Chief Justice was the colleague most frequently joined by Bell and Gordon JJ while Keane J was joined most by Nettle and Edelman JJ. Gageler J joined most often with Bell J.

Gageler J was the member of the Court who joined least often with all other Justices – his highest percentage of joining (42.50 per cent of his decisions, with Bell J) is notably lower than the highest percentage of joining for all others. Reciprocally, Gageler J was the member of the Court that all but Bell and Gordon JJ joined with least. Those two Justices joined less with Edelman J, but not by much and so suggesting that this is attributable to a relative limit upon opportunity.

As noted in the 2016 results, the three longest serving members of the Court show a greater tendency, certainly amongst each other, to join than do the more recent appointments. This accords with the public comments on the value of joint judgments that have been delivered by the Chief Justice and Justices Bell and Keane.[49]

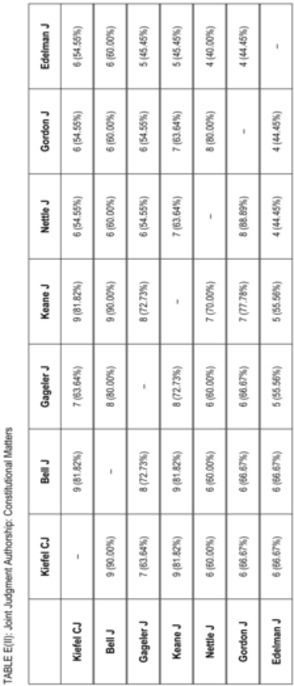

In Table E(II) we see the pattern of joint judgment authorship carried over to the subset of constitutional matters. Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ were the most frequent members of joint opinions in constitutional cases. But Nettle and Gordon JJ should also be noted; as in 2016, they joined each other on constitutional matters to a notable degree. In 2016, Gageler J joined with other Justices just once in a constitutional matter, but in 2017 he did so in 72.73 per cent of the eleven cases he decided in this area.

TABLE F(I): Joint Judgment Authorship: All Matters: Rankings

|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

Bell J

|

Gageler J

|

Keane J

|

Nettle J

|

Gordon J

|

Edelman J

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kiefel J

|

–

|

2

|

6

|

1

|

3

|

5

|

4

|

|

Bell J

|

1

|

–

|

5

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

6

|

|

Gageler J

|

3

|

1

|

–

|

2

|

4

|

4

|

5

|

|

Keane J

|

1

|

2

|

6

|

–

|

3

|

5

|

4

|

|

Nettle J

|

2

|

3

|

6

|

1

|

–

|

4

|

5

|

|

Gordon J

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

2

|

2

|

–

|

4

|

|

Edelman J

|

2

|

4

|

6

|

1

|

3

|

5

|

–

|

TABLE F(II): Joint Judgment Authorship: Constitutional Matters: Rankings

|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

Bell J

|

Gageler J

|

Keane J

|

Nettle J

|

Gordon J

|

Edelman J

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Kiefel CJ

|

–

|

1

|

2

|

1

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

Bell J

|

1

|

–

|

2

|

1

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

|

Gageler J

|

2

|

1

|

–

|

1

|

3

|

3

|

4

|

|

Keane J

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

–

|

3

|

3

|

4

|

|

Nettle J

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

–

|

1

|

4

|

|

Gordon J

|

3

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

1

|

–

|

4

|

|

Edelman J

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

2

|

3

|

3

|

–

|

The rankings of joining between the Justices indicated by Tables E(I) and (II) are the subject of Tables F(I) and (II). It should be noted that in some instances the difference between how frequently one judge wrote with various colleagues is not large, maybe just one or two decisions, so the ranking of different judges as joining with each other in these tables needs to be kept in perspective by referring back to the Tables E(I) and (II).

Chief Justice Susan Kiefel has expressed publicly, and with particular clarity, her view of how the High Court should decide the cases that come before it. She has emphasised the importance of the Court as a singular institution and expressed an aversion to individualism for its own sake. This is in contrast to the English legal tradition of seriatim judicial opinions and also the perspective held by others who instead emphasise the role of the individual judge and the value of diversity of opinion and dissent to the work of a multi-member court.

It can take many years, if at all, for the views of a Chief Justice to be reflected in the operation of a court. But interestingly, the cases decided by the High Court in 2017, the first year of Kiefel’s tenure as Chief Justice, bear a striking resemblance to her vision. This is due in part to the fact that she has come to preside over a Court in which collegiality and agreement were already its dominant characteristics. In one sense, her appointment ensures strong continuity with the tenure of her predecessor, Chief Justice French.

But it is wrong to suggest that 2017 was merely more of the same. This fails to appreciate the many distinctive features of the High Court’s decision-making last year. In key respects, the Court accorded to a higher degree with the notion that it should speak with an institutional, rather than individual, voice. One aspect is the rise in the number of cases decided unanimously. In the prior years of this study, the resolution of three constitutional cases a year through universal agreement represented a high point. Even then, decision-making over at least one dissenting opinion was more frequent. By contrast, in 2017, five constitutional matters were decided unanimously, four by concurrence and only two featured a dissenting opinion. This equated to a dissenting opinion being delivered in only 18.18 per cent of the constitutional cases last year, the lowest level since this annual series commenced in 2003.

The low rate of disagreement on the High Court is reflected across the full body of its decision-making. Compared to prior years, dissent remained unusual, and when it occurred it was typically isolated to only one Justice. In fact, of the 51 matters decided in 2017, only three saw more than one Justice in dissent. Of those, only one case involved the Court deciding the matter by a majority of one vote. Such decision-making is a far cry from earlier eras when a divided court saw a high prevalence of dissent, and the resolution of matters by a 4:3 or 3:2 majority was common.

The pattern of decision-making of the Chief Justice in 2017 corresponded with that of her Court. She did not issue a single dissent in 2017. In every case, her voice joined with that of the Court in expressing its orders as to how the matter should be disposed. But a tendency to harmony rather than discord pervaded the Court – no Justice appeared to be a marked outsider to the formation of majority opinion in 2017. Dissent rates were relatively modest and what disagreement was in evidence was distributed among a number of members of the Court rather than isolated.

These outcomes speak of a Court characterised by strong internal relationships and the processes of decision-making outlined by the Chief Justice in her revealing speech on ‘Judicial Methods in the 21st Century’. It also suggests a collegiate institution in which judges are, more often than in past eras, of a like mind and not beholden to a rigid preference to speak on their own behalf, but instead open to speaking with others for the Court as an institution.

This has enabled the High Court to project a powerful sense of confidence and authority in its role as third arm of government in Australia. This was especially important in 2017 given the matters decided by the Court. Several involved areas of high political controversy, such as Wilkie v Commonwealth[50] on the fate of the Federal Government’s postal survey on same-sex marriage, and a number of matters on the disqualification of members of the federal Parliament under section 44 of the Australian Constitution. It says much about the standing of the Court that these questions were resolved in a way that attracted the unquestioning adherence of the political branches. This extended to the decision in Re Canavan to disqualify Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce,[51] thereby imperilling the position of the Coalition Government given its one seat majority in the federal Parliament. The Government readily accepted this, even though Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull had earlier declared that Joyce ‘is qualified to sit in this House, and the High Court will so hold’.[52]

The means by which the High Court resolved matters in 2017, in keeping with the preference expressed by Chief Justice Kiefel, has been particularly effective during a politically turbulent period. At such times, coherence and certainty on the part of the Court are highly valued. The uncertainty and unpredictability that can be engendered by multiple judgments and close calls would certainly be undesirable when it comes to questions such as who is entitled to sit in the federal Parliament.

It must also be recognised that this approach has its costs. Inevitably, an emphasis on joint judgments and institutional voice produces opinions with a narrower focus on the immediate decision at hand that members will more readily ‘join’. The issues in a case are dealt with efficiently, but perhaps with less creativity and certainly with less diversity of expression that may otherwise deepen the reader’s understanding of the principles upon which the Court is drawing to answer the question at hand.[53]

Certainly, not all separate concurrences are ‘vanity judgments’ and some fulfil a uniquely valuable function by explaining the majority’s decision in a way that the joint judgment is constrained from doing by virtue of the fact it has been written to gain adherents from across the Court, resulting in a certain blandness. Further, in a Court where the pungency of dissent hardly appears to be a contemporary problem inflicting reputational damage on the institution, an appreciation of the value of individuality and disagreement might be a welcome tonic to strong messages about the undoubted virtues of institutional coherence. As the Court and its Justices have shown, there is validity in both sides of this equation.

The notes identify when and how discretion has been exercised in compiling the statistical tables in this article. As the Harvard Law Review editors once stated in explaining their own methodology, ‘the nature of the errors likely to be committed in constructing the tables should be indicated so that the reader might assess for himself the accuracy and value of the information conveyed’.[54]

• Re Culleton [No 2] (2017) 341 ALR 1; [2017] HCA 4.

• Palmer v Ayres; Ferguson v Ayres (2017) 259 CLR 478; [2017] HCA 5.

• Re Day [No 2] (2017) 343 ALR 181; [2017] HCA 14.

• Rizeq v Western Australia (2017) 344 ALR 421; [2017] HCA 23.

• Knight v Victoria (2017) 345 ALR 560; [2017] HCA 29.

• Plaintiff S195/2016 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 346 ALR 181; [2017] HCA 31.

• Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection; Te Puia v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 347 ALR 350; [2017] HCA 33.

• Wilkie v The Commonwealth; Australian Marriage Equality Ltd v Cormann (2017) 349 ALR 1; [2017] HCA 40.

• Brown v Tasmania (2017) 349 ALR 398; [2017] HCA 43.

• Re Canavan; Re Ludlam; Re Waters; Re Roberts [No 2]; Re Joyce; Re Nash; Re Xenophon (2017) 349 ALR 534; [2017] HCA 45.

• Re Nash [No 2] (2017) 350 ALR 204; [2017] HCA 52.

• Mercanti v Mercanti (2017) 340 ALR 225; [2017] HCA 1 – Kiefel CJ sitting alone.

• Re Day (2017) 340 ALR 368; [2017] HCA 2 – Gordon J sitting alone.

• Re Culleton (2017) 340 ALR 550; [2017] HCA 3 – Gageler J sitting alone.

• Re Roberts (2017) 347 ALR 600; [2017] HCA 39 – Keane J sitting alone.

• Re Barrow (2017) 349 ALR 574; [2017] HCA 47 – Edelman J sitting alone.

• Dimitrov v Supreme Court of Victoria (2017) 350 ALR 191; [2017] HCA 51 – Edelman J sitting alone.

The following cases involved a number of matters but were tallied singly due to the presence of a common factual basis or questions:

• Palmer v Ayres; Ferguson v Ayres (2017) 259 CLR 478; [2017] HCA 5.

• Commissioner of State Revenue v ACN 005 057 349 Pty Ltd (2017) 341 ALR 46; [2017] HCA 6.

• Western Australian Planning Commission v Southregal Pty Ltd; Western Australian Planning Commission v Leith (2017) 259 CLR 106; [2017] HCA 7.

• Air New Zealand Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission; PT Garuda Indonesia Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2017) 344 ALR 377; [2017] HCA 21.

• New South Wales v DC (2017) 344 ALR 415; [2017] HCA 22.

• Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection; Te Puia v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 347 ALR 350; [2017] HCA 33.

• SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection; SZTGM v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 347 ALR 405; [2017] HCA 34.

• Wilkie v The Commonwealth; Australian Marriage Equality Ltd v Cormann (2017) 349 ALR 1; [2017] HCA 40.

• Cecil v Director of Public Prosecutions (Nauru); Kepae v Director of Public Prosecutions (Nauru); Jeremiah v Director of Public Prosecutions (Nauru) (2017) 349 ALR 570; [2017] HCA 46.

• Re Canavan; Re Ludlam; Re Waters; Re Roberts [No 2]; Re Joyce; Re Nash; Re Xenophon (2017) 349 ALR 534; [2017] HCA 45.

• Smith v The Queen; R v Afford (2017) 259 CLR 291; [2017] HCA 19 – Consists of two distinct criminal law appeals, treated separately by both the joint judgment and sole-authored opinion of Edelman J; the latter concurs in the decision that the appeal in Smith v The Queen should be dismissed, but partially dissents on the appeal in R v Afford by ordering that the matter be remitted for retrial.

• Re Day [No 2] (2017) 343 ALR 181; [2017] HCA 14 – All Justices are tallied as concurring though Gageler J and Nettle and Gordon JJ answer Question (c) by stating 1 December 2015 rather than 26 February 2016 as the date on which Mr Day became incapable of sitting as a senator; Keane J declares Question (d) ‘Unnecessary to answer’ while the rest of the Court decides that any further directions and orders necessary to finally dispose of this reference may be made by a single Justice of the Court.

• Plaintiff M96A/2016 v Commonwealth (2017) 343 ALR 362; [2017] HCA 16 – Migration case with one mention of section 51(xix) and Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs (1992) 176 CLR 1 and Al-Kateb v Godwin [2004] HCA 37; (2004) 219 CLR 562 only; not tallied as a constitutional matter.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2003 Statistics’ [2004] UNSWLawJl 4; (2004) 27 University of New South Wales Law Journal 88.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2004 Statistics’ [2005] UNSWLawJl 3; (2005) 28 University of New South Wales Law Journal 14.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2005 Statistics’ [2006] UNSWLawJl 21; (2006) 29 University of New South Wales Law Journal 182.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2006 Statistics’ [2007] UNSWLawJl 9; (2007) 30 University of New South Wales Law Journal 188.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2007 Statistics’ [2008] UNSWLawJl 9; (2008) 31 University of New South Wales Law Journal 238.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2008 Statistics’ [2009] UNSWLawJl 8; (2009) 32 University of New South Wales Law Journal 181.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2009 Statistics’ [2010] UNSWLawJl 12; (2010) 33 University of New South Wales Law Journal 267.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2010 Statistics’ [2011] UNSWLawJl 42; (2011) 34 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1030.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2011 Statistics’ [2012] UNSWLawJl 33; (2012) 35 University of New South Wales Law Journal 846.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2012 Statistics’ [2013] UNSWLawJl 19; (2013) 36 University of New South Wales Law Journal 514.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2013 Statistics’ [2014] UNSWLawJl 20; (2014) 37 University of New South Wales Law Journal 544.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2014 Statistics’ [2015] UNSWLawJl 38; (2015) 38 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1078.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2015 Statistics’ [2016] UNSWLawJl 41; (2016) 39 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1161.

• Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2016 and French Court Statistics’ (2017) 40 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1468.

[*] Professor, Head of School, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales.

[**] Anthony Mason Professor, Scientia Professor and Dean, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales; Barrister, New South Wales Bar.

We thank Zoe Graus for research assistance and the three anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions on this article.

[1] Australian Constitution s 72. It seems safe to say that the effect of the mandatory retirement age means that Justice McTiernan’s record 46-year tenure on the High Court (1930–76) will never be beaten.

[2] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2003 Statistics’ [2004] UNSWLawJl 4; (2004) 27 University of New South Wales Law Journal 88. For a full list of the published annual studies, see the Appendix to this article. An earlier article, by one of the co-authors, examined a larger focus: Andrew Lynch, ‘The Gleeson Court on Constitutional Law: An Empirical Analysis of Its First Five Years’ [2003] UNSWLawJl 2; (2003) 26 University of New South Wales Law Journal 32.

[3] See Andrew Lynch, ‘Dissent: Towards a Methodology for Measuring Judicial Disagreement in the High Court of Australia’ (2002) 24 Sydney Law Review 470, with further discussion in Andrew Lynch, ‘Does the High Court Disagree More Often in Constitutional Cases? A Statistical Study of Judgment Delivery 1981–2003’ (2005) 33 Federal Law Review 485, 488–96.

[4] For the inaugural study, see Felix Frankfurter and John M Landis, ‘The Business of the Supreme Court at October Term, 1928’ (1929) 43 Harvard Law Review 33.

[5] This was publicly affirmed early in the year by Justice Bell when she said, ‘there is no reason to think that there will be a departure from the collegial decision-making which characterised the French Court under the stewardship of Kiefel CJ’: Justice Virginia Bell, ‘Examining the Judge’ (Speech delivered at the University of New South Wales Law Journal Launch of Issue 40(2), Clayton Utz, Sydney, 29 May 2017) 2.

[6] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2016 and French Court Statistics’ (2017) 40 University of New South Wales Law Journal 1468, 1469–70.

[7] Chief Justice Susan Kiefel, ‘Judicial Methods in the 21st Century’ (Speech delivered at the Supreme Court Oration, Banco Court, Supreme Court of Queensland, 16 March 2017) 6–7.

[8] Justice Susan Kiefel, ‘The Individual Judge’ (2014) 88 Australian Law Journal 554, 557.

[9] Andisheh Partovi et al, ‘Addressing “Loss of Identity” in the Joint Judgment: Searching for “The Individual Judge” in the Joint Judgments of the Mason Court’ [2017] UNSWLawJl 25; (2017) 40 University of New South Wales Law Journal 670.

[10] Bell, above n 5, 2–3. Citation for the original reference by Partovi et al is Andrew Lo, ‘A Judicial Whodunnit: Shedding Light on Unsigned Opinions’, Cognoscenti (online), 30 July 2013 <http://cognoscenti.legacy.wbur.org/2013/07/30/unsigned-per-curiam-opinions-andrew-lo> .

[11] Kiefel, ‘Judicial Methods’, above n 7, 9. Four years earlier, Justice Kiefel declared, ‘[m]ost appellate judges in Australia would, I think, express a preference for a joint judgment where it is possible, when judges are in agreement, unless a judge has a different approach to reasoning to the same conclusion and wishes to express it or has something that he or she wishes to add’: Justice Susan Kiefel, ‘On Being a Judge’ (Speech delivered at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, 15 January 2013) 8.

[12] Kiefel, ‘Judicial Methods’, above n 7, 7–8.

[13] Ibid 8, 10.

[14] See Lord Neuberger, ‘Open Justice Unbound?’ (Speech delivered at the Judicial Studies Board Lecture, London, 16 March 2011) 10 [24]; Lord Neuberger, ‘Sausages and the Judicial Process: The Limits of Transparency’ (Speech delivered at the Annual Conference of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, Sydney, 1 August 2014) 15 [32].

[15] Neuberger, ‘Sausages and the Judicial Process’, above n 14, 15 [32].

[16] See Andrew Lynch, ‘Keep Your Distance: Independence, Individualism and Decision-Making on Multi-member Courts’ in Rebecca Ananian-Welsh and Jonathan Crowe (eds), Judicial Independence in Australia: Contemporary Challenges, Future Directions (Federation Press, 2016) 156.

[17] Kiefel, ‘The Individual Judge’, above n 8, 559.

[18] Anthony Mason, ‘Personal Relations: A Personal Reflection’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia (Oxford University Press, 2001) 531, 532.

[19] Australasian Legal Information Institute <https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewtoc/au/cases/cth/HCA/2017/>. For further information about decisions affecting the tallying of 2017 matters, see the Appendix – Explanatory Notes at the conclusion of this article.

[20] Stephen Gageler, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2001 Term’ [2002] UNSWLawJl 8; (2002) 25 University of New South Wales Law Journal 194, 195.

[21] Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2007 Statistics’ [2008] UNSWLawJl 9; (2008) 31 University of New South Wales Law Journal 238, 240.

[22] Re Culleton [No 2] [2017] HCA 4; (2017) 341 ALR 1; Re Day [No 2] (2017) 343 ALR 181; Re Canavan (2017) 349 ALR 534; Re Nash [No 2] [2017] HCA 52; (2017) 350 ALR 204.

[23] A longitudinal examination of decision-making in cases heard as the Court of Disputed Returns, and contrasting this with rates of unanimity more generally, presents itself as a worthwhile study, but is obviously outside the scope of this article.

[24] All percentages given in this table are of the total number of matters tallied (51).

[25] All percentages given in this table are of the total number of constitutional matters tallied (11).

[26] [2017] HCA 13; (2017) 259 CLR 275.

[27] We have earlier explained that cases decided in this way are still tallied as having been decided through concurrences, since the form in which the agreement across the Court is expressed is not joint but separate: Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2013 Statistics’ [2014] UNSWLawJl 20; (2014) 37 University of New South Wales Law Journal 544, 552.

[28] We have identified these earlier instances in each annual study as relevant. However, the practice predates this series and was observed in respect of the arrival of Gummow J (see David Grant & Co Pty Ltd (rec apptd) v Westpac Banking Corporation (1995) 184 CLR 265) and before him McHugh J (see Jones v Hyde [1989] HCA 20; (1989) 85 ALR 23). We are grateful to James Lee for drawing these earlier examples to our attention.

[29] An earlier occasion in which the ‘welcome’ tradition did not see bare concurrences from all other members of the Court was Queensland Premier Mines Pty Ltd v French [2007] HCA 53; (2007) 235 CLR 81, in which Kirby J delivered a substantive concurrence alongside the lead judgment of newcomer Kiefel J: see Andrew Lynch and George Williams, ‘The High Court on Constitutional Law: The 2007 Statistics’ [2008] UNSWLawJl 9; (2008) 31 University of New South Wales Law Journal 238, 243. See also A J Brown, Michael Kirby: Paradoxes & Principles (Federation Press, 2011) 401.

[30] [2017] HCA 15; (2017) 260 CLR 124.

[31] Brice Dickson, ‘Close Calls in the House of Lords’ in James Lee (ed), From House of Lords to Supreme Court (Hart Publishing, 2011) 283.

[32] [2017] HCA 20; (2017) 344 ALR 187.

[34] [2017] HCA 29; (2017) 345 ALR 560.

[35] [2017] HCA 31; (2017) 346 ALR 181.

[36] [2017] HCA 40; (2017) 349 ALR 1.

[38] [2017] HCA 52; (2017) 350 ALR 204.

[39] [2017] HCA 20; (2017) 344 ALR 187.

[42] In this respect, consider Brown, above n 29, 290–2, 391–3 (regarding Kirby J) and Gabrielle Appleby and Heather Roberts, ‘He Who Would Not Be Muzzled: Justice Heydon’s Last Dissent in Monis v The Queen (2013)’ in Andrew Lynch (ed), Great Australian Dissents (Cambridge University Press, 2016) 335 (regarding Heydon J).

[43] Chief Justice Susan Kiefel, ‘Judicial Courage and Decorum of Dissent’ (Speech delivered at the Selden Society Lecture, Supreme Court of Queensland, 28 November 2017).

[44] [1941] UKHL 1; [1942] AC 206.

[45] Kiefel, ‘Judicial Courage’, above n 43, 8. See further, Andrew Lynch, ‘Introduction – What Makes a Dissent “Great”?’ in Andrew Lynch (ed), Great Australian Dissents (Cambridge University Press, 2016) 1, 11–12.

[46] Kiefel, ‘Judicial Courage’, above n 43, 10.

[47] [2017] HCA 33; (2017) 347 ALR 350.

[49] See Kiefel, ‘Judicial Methods’, above n 7; Kiefel, ‘The Individual Judge’, above n 8; Bell, above n 5; and earlier Justice P A Keane, ‘The Idea of the Professional Judge: The Challenges of Communication’ (Speech delivered at the Judicial Conference of Australia Colloquium, Noosa, 11 October 2014).

[50] [2017] HCA 40; (2017) 349 ALR 1.

[52] Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 14 August 2017, 8265 (Malcolm Turnbull).

[53] For an interesting contrast drawn between judgments produced using the High Court’s current decision-making approach and that of intermediate courts, see Justice Margaret Beazley, ‘Judgment Writing in Final and Intermediate Courts of Appeal: “A Dalliance on a Curiosity”’ (Paper presented at the 20th Anniversary of the Victorian Court of Appeal, Melbourne, 20 August 2015).

[54] Louis Henkin, ‘The Supreme Court, 1967 Term’ (1968) 82 Harvard Law Review 63, 301–2.

[55] The purpose behind multiple tallying in some cases – and the competing arguments – are considered in Lynch, ‘Dissent’, above n 3, 500–2.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2018/39.html