University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

DIRECTOR APPOINTMENTS: EXPRESSING BOARD CARE AND DILIGENCE

THEA VOOGT* AND MARTIE-LOUISE VERREYNNE**

Shareholders’ rights to appoint directors in widely-held companies are effectively held by the incumbent board as ‘agents’. This article advocates for the adoption of an integrated instrument designed to enhance accountability for the composition of the board, which sits at the apex of the board’s autonomous corporate control. Formulated as a focused numbered checklist, the instrument was developed through textual and statistical analytical techniques, drawing on empirical evidence from director skills matrices disclosed by large listed Australian companies. The instrument acts as an expression of the legal duty of care and diligence that the directors discharge in selecting board members, and relies on disclosure to make the market for corporate control more efficient: if the board is more accountable, shareholders are better able to monitor and discipline the directors.

In the vast majority of companies, the dominant feature of the governance arrangements involves the allocation of day-to-day monitoring and management power to the directors or senior management, and the allocation of appointment rights to the shareholders. Conceptually, this allocation is most often explained in terms of the nexus of contracts theory of the company. This theory conceives of the company, and its governance arrangements, as simply an expression of the (notional) bargain that the principal participants in the business enterprise would have reached, but for the presence of transaction costs.[1] The allocation of management control to directors and appointment rights to shareholders are, therefore, both explained and justified by the agreement or equilibrium reached between them, according to which they are rational participants with a rational appreciation of their respective incentives.

In practical terms, however, this neat explanation is threatened in widely-held companies. In reality, it is the incumbent directors who in fact select and nominate those to be appointed to the board. While shareholders will always retain the legal ability to appoint (and remove) directors, they have little or no scope to propose nominees who are not supported by the incumbent board. The shareholders’ appointment role has thus become one of merely confirming the incumbent-proposed slate of nominees.

In this article, we advocate for the adoption of an integrated disclosure instrument that has relevance across three layers of corporate governance regulation: state-based, market-based and self-regulation.[2] The instrument acts as an expression of the legal duty of care and diligence that the directors discharge in selecting board members, and as a conceptualisation of the incumbent board’s function, under the nexus of contracts theory, as they act as ‘agents’ in providing the shareholders with appropriately skilled nominees for appointment to the board. The flexible approach of the instrument acknowledges that the board has the autonomy to make decisions about the governance mechanisms most appropriate to the circumstances of the company.[3] The instrument relies on disclosure to make the market for corporate control more efficient; if the board is more accountable, shareholders are better able to monitor and discipline the directors.[4]

There are three aspects to our argument. First, we examine the contemporary corporate governance practice, namely that boards play the key role in the appointment of directors. We consider the main advantages and acknowledge the flaws inherent in board-led director nominations. Second, we apply textual and statistical analytical techniques to develop our integrated disclosure instrument, presented in Table 5. The instrument is formulated as a focused, numbered checklist of questions, designed to enhance accountability for the composition of the board, which sits at the apex of the board’s autonomous corporate control. As we develop our instrument through the article, we disclose the numbers of the questions in the checklist presented in Table 5 to explain how we incorporate our analysis in the instrument. Last, the article considers how the application of the instrument has the capacity to return significant commercial benefits for the company and its shareholders, reduce rational shareholder apathy and facilitate minority shareholder participation in financial markets generally.

While our instrument has wide cross-jurisdictional application, at the outset, we note three limitations of the process we employed to develop the instrument. First, in mapping the roles and responsibilities of directors, we apply textual analysis to five corporate governance codes. While these are rated as leading codes, further analysis of a larger number of codes could change our theoretical universal director skills base, presented in Table 2. Second, we use empirical evidence obtained from skills matrices disclosed by the 100 largest listed companies in Australia in our statistical analysis, introducing unquantifiable country bias. We acknowledge that board skills in large listed companies may differ from those in smaller companies. Third, we recognise that there may be a disconnect between disclosed board skills and the skills actually present among board members.

From a company law perspective, shareholder rights to nominate directors differ between jurisdictions. For example, there is no minimum shareholding required to nominate directors in countries such as the United Kingdom (‘UK’), France, Germany, Australia, Sweden, Belgium and Brazil. Nevertheless, shareholders’ practical ability to bring such a resolution to the general meeting may be limited. For example in Australia, at least 100 members together, or members with at least five per cent of the votes, are entitled to do so.[5] In other countries, minimum shareholdings are imposed to nominate directors, for example in Canada (five per cent), Netherlands (one per cent) and Indonesia (10 per cent).[6] Theoretically, given these relatively low ownership hurdles, it is possible that even a small shareholding or a small number of shareholders working together can take de facto control of the director nomination process. In practice, this is unlikely to occur due to shareholder apathy and the collective action problem that still dominates behaviour, overshadowing the impact of contemporary shareholder empowerment and activism.[7]

Shareholder participation in director nominations and evaluations in Australia is largely limited to institutional shareholders who dominate share ownership on financial markets and to proxy advisory firms that control significant voting power.[8] Both groups play a significant monitoring role in the market for corporate control by expressing vocal positions on remuneration, using the power they have under the ‘two strikes rule’.[9] However, there is little evidence to suggest that they, or other shareholders, vote against director-election resolutions since these are adopted close to 100 per cent of the time.[10] In the case of institutional investors, it may be that there is little need for them to vote against incumbent-proposed directors. Tailored investor relations programs provide institutional investors with ongoing opportunities to voice their opinions and to enter into dialogue with the board and executive team on a range of matters,[11] including board nominations. Any objections they may have to the appointment of nominees are likely dealt with behind closed doors.

In Australia, as is the case in many jurisdictions, it is the board itself, or a board committee, that comes up with nominees, since this is benchmark practice in corporate governance codes, reflecting the practice long followed since the 1980s.[12] Board-led director nominations has three important advantages. First, it is a well-established norm that boards must comprise of a majority of (arguably) independent non-executive directors (‘NEDs’),[13] often as high as 80 per cent in practice.[14] This acts as a protection mechanism for shareholders against biased or inappropriate director nominations, counters management influence over the process and ensures diversity of board composition and thought.[15] Even if director nominations are delegated to a board nomination committee, corporate governance codes recommend that board nomination committees must include or comprise of a majority of independent NEDs.[16] Second, if the board is involved in the nomination process, they would be able to assess the potential of the incumbents and nominees to collaborate and engage in ‘collegial decision making’,[17] which is less likely to occur when shareholders nominate the directors. Third, directors’ main duty is to the company. If shareholders promote special interest directors, their appointment may result in a dysfunctional board.[18]

The board plays an equally prominent role in evaluating its own composition and performance. We demonstrate this in reference to five leading corporate governance codes: UK, Singapore, Australia, G20/OECD and South Africa,[19] and continue to use these codes in the rest of our study to further inform our instrument.

In the UK, annual formal, transparent, rigorous evaluation is required of the balance of skills, diversity and the performance of the board overall, its committees and each individual director, led by the nomination committee that consists of a majority of NEDs.[20] In the case of the Financial Times Stock Exchange (‘FTSE’) 350 companies, the evaluation must be externally facilitated at least every three years.[21] If the evaluation identifies gaps, it is the responsibility of the chairman to ensure that new board members are appointed to fill the gaps.[22] At re-appointment (which occurs annually for FTSE 350 NEDs) there must be disclosure to the shareholders of the reasons why a particular director remains suitable.[23] This director-specific disclosure is a precedent that supports our integrated disclosure instrument and demonstrates how boards can disclose how they have applied their minds to re-appointments. We incorporate the relevance of director skills at re-appointment in Question 5 of our disclosure instrument, presented in Table 5. Beyond that, the UK Code requires disclosure of the work of the nomination committee, but this is limited to policy about diversity, the nature of the talent search for new directors and how the board evaluation is performed.[24]

The Singapore Code 2018 requires a formal evaluation, led by the nomination committee, and disclosure of the nature of the process, including whether it was internally or externally facilitated.[25] The Australian Securities Exchange (‘ASX’) code requires rigorous periodic evaluation of the board as a whole, of each director and of board committees, and when this is performed, disclosure in the annual report, but limited to insights gained from the process.[26] South Africa’s King IV Code attaches high importance to annual board evaluation performed by the nomination committee, externally facilitated or in a manner different to that approved by the board every alternate year, with disclosure of: the process undertaken, results, remedial action taken and whether the evaluation process improved performance and effectiveness.[27]

None of the codes require disclosure of the outcome of the evaluation of each individual board member, leaving shareholders with little information beyond broad strokes about the board evaluation process, and reliant on the board in so far as the suitability of directors for re-appointment is concerned.

Although board-led director nomination and board evaluation is widely adopted in countries like Australia, the process suffers from more than the inherent limitations of self-evaluation and limited disclosure. First, we consider the independence of NEDs, which is a cornerstone of contemporary corporate governance.[28] As discussed above, the involvement of independent directors in the nomination process acts as a protection mechanism against bias or undue management influence over the process.

The test of director independence is structural in nature,[29] ignoring professional networks and social ties. These ties are nevertheless powerful, influencing who gets nominated for board positions, resulting in members of the board having similar backgrounds and experiences. Several studies significantly support the conclusion that nomination committee recommendations can be linked to director social networks and connections.[30] There is a risk that the social, intellectual and cultural cohesiveness of the board can result in groupthink that negatively affects the directors’ ability to express independent judgment.[31] Similarly, as boards operate in small groups, they are affected by the dynamics of small groups that tend to avoid conflict and close out alternative views and influences, which is more likely to occur if there is overt cohesion between board members.[32]

The second significant flaw of board-led director nominations is dependent upon the extent to which the chief executive officer (or one or two executives) is able to play an instrumental role in board nominations, resulting in board capture.[33] In turn, board capture can result in knowledge capture if the chief executive officer has unfettered and, rarely challenged, control over the information that the board has access to.[34] In the case of board capture, it may be that the only effective measure to address knowledge capture is significant industry experience on the part of independent directors.[35]

As we will show later, industry experience (Table 5, Question 11, how a nominee’s experience is relevant to their role) is an element of director skill and a dimension of board diversity (Table 5, Question 12, how board diversity relates to company objectives). While our proposed instrument is unable to address the influence of professional networks and social ties on board composition, it does require significant consideration of diversity on the part of the board when they identify suitable nominees. Taking into account the flaws in board-led director nominations, our instrument is built around the benefits associated with this process, and is focused on how the board may be more accountable in this role.

If it is accepted that the board is best placed to nominate directors, it is incumbent upon them to understand what directors do, so that board-proposed nominees are suitably skilled to fulfil their duties (Table 5, Question 9, board skills to manage and direct the company). While there may be an expectation on the part of the public that directors are actively involved in the business of the company, the overwhelming majority are appointed in non-executive positions. Therefore, they are not involved in the day-to-day activities of the company and are more focused on direction and oversight.[36] This practical position must be contrasted to the almost non-existent special status of NEDs under company law. While there are continued calls for greater clarity about the role of NEDs,[37] there has neither been a practical move towards a legal differentiation in the standard of conduct and the duties of executive directors when compared to NEDs,[38] nor in the benchmark roles and responsibilities of directors presented in corporate governance codes. All the directors are therefore accountable to the shareholders in the same way for the governance and performance of the company, and to direct the company,[39] despite significant variation in their roles. Similarly, all the directors should have the skills required to fulfil their legal duties.

Herein lies the first hurdle that boards are likely to face. The legal duties of directors are described as ‘extraordinarily complex, imprecise, confusing, imperfect and very much in need of reform and clarification’,[40] and require significant interpretation in reference to case law. As a consequence, it is difficult to articulate the legal skills required of directors to fulfil these duties. It is more likely that the board will turn to single-source, concise, user-friendly, easy-to-understand, practical corporate governance codes to gain an understanding of what directors ought to do generally, and what their matching skill set must be, against which director nominations may be framed (Table 5, Questions 1 and 2, the minimum skill set relevant to the company).[41]

For the same reasons, we use contemporary corporate governance code interpretations of the roles and responsibilities of directors to signpost the universal skills that nominees should have and do so in reference to the world-leading UK, Singapore, Australian, G20/OECD and South African codes, noting that subsequent to our text analysis explained below, the UK and Singaporean codes were updated in 2018.[42]

Turning first to the UK Code, it contains a list of the roles and responsibilities of audit committee members, but intersperses the responsibilities of directors throughout that code.[43] The Singaporean,[44] Australian,[45] and South African codes[46] take a more direct approach by listing the main responsibilities of directors. The Singaporean code expands on these in so far as strategy and risk is concerned.[47] The G20/OECD Principles deal with the responsibilities of the board along three themes: strategic guidance, effective monitoring of management, and board accountability to the company and its shareholders.[48]

We developed a database of director roles and responsibilities from these codes for further analysis. After extracting the text of all of these roles and responsibilities from the five codes, we applied Leximancer, a computer-aided text analysis software, to the data. Leximancer codifies text into categories (themes and concepts) based on word frequency and co-occurrence using scientific analysis conventions, and is widely used in academic research to analyse text.[49] Its use of content analytical principles, such as ontological relativity and dynamics, enables it to structure and evaluate information to identify concepts (thematic analysis) and the relationships between these concepts (semantic analysis).[50] Leximancer maps show the results of the semantic and relational analysis. The concepts, which are clustered into broader themes as indicated by the circles on the map, are based on a ranked list of terms according to its frequency within the text. The links between concepts present the co-occurrence of these terms, which is calculated using an asymmetrical co-occurrence matrix. Closeness between concepts indicates co-occurrence between concepts in the data, whereas centrality of concepts can be interpreted as the extent to which it is connected to other concepts.[51] By using Leximancer, we avoided researcher bias in analysing the universally-adopted roles and responsibilities of directors.[52] The Leximancer results of our analysis of the roles and responsibilities of directors are represented as a two-dimensional map shown in Figure 1. Four themes emerge from the analysis.

Figure 1: Two-Dimensional Map of the Roles and Responsibilities of Directors as Determined by Leximancer

The emergence of the verbs ‘setting’, ‘implementation’, ‘ensuring’, and ‘monitoring’ demonstrates that the director’s role is not characterised by passivity. The notion of a ‘sleeping director’ is not appropriate, confirmed in several Australian cases about director conduct heard since the 1990s.[53] While these activities may still lie beyond the day-to-day operations of the company, it points to the necessary time availability and active steps that directors must be able to take to fulfil their role.[54] Directors cannot use subjective reasonableness, limits on their knowledge and experience, ignorance, or inaction as an excuse for an inappropriate standard of care as they perform their duties.[55] As a precursor, the board must consider whether nominees have (or are able to acquire) ‘at least a rudimentary understanding of the business’ and are able to ‘become familiar with the fundamentals of the business’.[56] It is fair to say that directors’ actions, once appointed, must be based on knowledge that extends beyond that proposed by Romer J in Re City Equitable Fire Insurance Co Ltd that a director ‘need not exhibit in the performance of his duties a greater degree of skill than may reasonably be expected from a person of his knowledge and experience’.[57]

Directors’ knowledge cannot be static. In his influential work, published nearly 60 years ago, Sir Douglas Menzies contended that directors must consider the effect of a changing economy on the business when guiding and monitoring the management team, and in bringing an informed and independent judgement to bear on matters that come before the board.[58] We contend that a constantly changing business environment requires skills renewal on the part of directors, and that this renewal must be evident in board nominations (Table 5, Questions 6 and 10, future skills and board renewal).

The second theme that emerges is the board’s role and responsibility in setting the corporate strategy and objectives to guide the executive or management team in formulating and implementing plans. As NEDs are tasked with constructively challenging and helping to develop strategy,[59] it is essential that they have the necessary skills and experience to do so (Table 5, Questions 4, 7 and 8, linking director skills to company strategy and risk). But our analysis shows that objective setting and strategic direction has a close proximity to implementation. Directors’ actions should therefore be focused on an ongoing assessment of the interwoven relationship between strategy, risk and the business model so as to guide implementation (Table 5, Question 9). Their assessment is a matter of public record, since it is disclosed in the strategic report in the UK,[60] and as part of the directors’ report elsewhere,[61] demonstrating an increasing disclosure of the way directors deal with risk as part of the overall strategy of the company. Our instrument links strategy and risk to director skills disclosure (Table 5, Questions 4, 5 and 8).

The third theme revolves around risk and risk management. Directors must set an appropriate risk appetite that involves determining the nature and extent of the risks they are willing to accept to meet the overall strategic objectives of the company. This necessitates a robust understanding and assessment of internal and external risks,[62] after which it is then left up to the executive and management team to design, build and implement the corporate risk management framework.[63] Change, we argue, as is perhaps most evident in the impact of rapidly evolving technology on companies, is also a risk, resulting in directors being challenged beyond their traditional knowledge and skill set. In our view, the board should be able to assess whether nominees will be able to respond to change and able to renew their skills as a consequence (Table 5, Questions 4, 5 and 6, focused on future skills suited to company strategy).

The fourth theme reflects the interdependence between the board, executive team and the shareholders. The Leximancer map reveals an almost equal theoretical prominence of the board and shareholders, which is very different to the almost absolute primacy of the board in director nominations. Our instrument strengthens the practical position of shareholders through disclosure that will make the board more accountable for director nominations.

We used the four themes of the roles and responsibilities of directors from our Leximancer map to signpost universal director skills associated with these that should be considered during the nomination process:

• The actions of directors are focused on oversight, and are different to the day-to-day activities usually performed by the executive or management team. Nominating candidates with experience in non-executive or board positions could be beneficial. We extract the skills: NED experience; board/ASX experience; leadership (Table 5, Question 11, experience relevant to the company).

• Directors focus on corporate strategy and have to monitor whether strategy implementation by the executive and management team progresses as planned. We extract the skill: strategy (Table 5, Questions 4 and 7, linking skills to company strategy and risk).

• The skill to set the risk appetite and to oversee risk management is critical to a director’s role. To apply these, the directors must have, or acquire knowledge about the business of the corporation and ideally knowledge of the industry in which the company operates. Since change impacts these aspects, we posit that technology, digital disruption and/or cyber fluency skills are good indicators of the extent to which director skills have adapted to change. We extract the skills: risk/risk management; industry experience; leadership, executive experience or operational management; cyber fluency (technology skills) (Table 5, Questions 4, 5, 6 and 11).

• The interdependence between the board and shareholders is facilitated through information. The directors’ ability to communicate effectively with shareholders and their regard for documenting (communicating) their decisions, including the reasoning for director nominations, are important. We extract the skill: communication/public relations. This skill is linked to the entirety of our instrument which is disclosure-based.

• Last, the way in which directors approach their role necessitates an understanding of the principles underlying corporate governance. We extract the skill: governance/corporate governance skills and knowledge (Table 5, Question 9, board skills to manage and direct the company).

Our analysis of the roles and responsibilities of directors described in the codes was instructive to signpost universal director skills in the first instance. Second, we take a more direct approach to establish a theoretical base for universal director skills. Turning to company law, there is little evidence of a particular list of skills that directors must have. For example, in the UK, directors must apply reasonable skill.[64] Similarly, in Australia, while the Corporations Act 2001 makes no reference to the ‘skill’ of a director within the relevant context of ‘care and diligence’,[65] the courts have nevertheless read a requirement that they apply reasonable skill into the section as evidenced in a number of cases focused on their specific duties, skills and expertise.[66] Overall, reasonable skill establishes a higher standard than that expressed in Re City Equitable Fire Insurance Co Ltd.[67]

However, it is difficult to pinpoint the specific dimensions of reasonable skill for NEDs (who make up the majority of listed company boards) from case law, since there is no particular profession linked to their non-executive role (as compared to the position of engineers, accountants etc.), further complicated by the diversity and varieties of companies.[68] Using Australia as an example, in defining an objective standard of reasonable care in AWA Ltd, Rogers CJ recognised that the duties of NEDs are intermittent and vary due to the variety of business ventures, even though a core group of professional NEDs has emerged.[69]

Corporate governance codes are more specific about director skills. All five of the codes we analysed recommend an appropriate balance of skills, experience, independence and knowledge of the company.[70] The Singapore Code 2012 goes a step further by listing examples of core director competencies: accounting/finance, business/management experience, industry knowledge, strategic planning experience, customer-based experience/knowledge.[71] Similarly, the South African code suggests that, overall, taking a broad approach, the board should consist of members with business, commercial and industry experience.[72] While we acknowledge that financial literacy is universally required of all directors,[73] recent and relevant financial experience is only required of one member in the UK Code, and required of all members of the audit committee in the South African Code (Table 5, Question 3, nominee financial literacy).[74]

Variation between directors in reference to their knowledge, skills, experience, age, culture, race and gender is important, resulting in board diversity,[75] which counteracts ‘groupthink’ (Table 5, Question 12, diversity).[76] This in turn reduces high levels of cohesiveness that can be dysfunctional.[77] The UK Code emphasises that diversity is not simply a factor of race and gender, but that it must recognise the need for differences in approach and experience (Table 5, Question 11, relevant experience).[78] Future thinking about corporate governance in the UK emphasises ethnicity.[79] Race also remains a key theme in South Africa where the social dynamic in the post-apartheid era necessitates targets for race and gender diversity.[80] Directors should also remain abreast of developments in new laws and regulations, changing commercial risks and a changing business environment (Table 5, Questions 6 and 12).[81]

It is interesting to note that despite the significant and pervasive impact of rapidly changing technology on business, none of the codes refer to technology skills, digital literacy or cyber fluency as important to directors. It is also only the South African code that includes significant benchmarks to deal with the effects of technology. Principle 12 leaves no doubt about the board’s role: ‘The governing body should govern technology and information in a way that supports the organisation setting and achieving its strategic objectives’.[82] We posit that technology related skills are crucial to directors (Table 5, Question 6).

From this direct guidance, we identify the following universal skills that should guide the director nomination process: financial literacy; industry experience; experience (board/ASX/NED); strategy; marketing/customer focus; technology; and compliance, legal, regulations and government relations.

Up to this point, we have used a theoretical approach to determine the universal skills of all directors which should be considered during the nomination process. We submit that a more practical approach, which considers the specific skills relevant to the business of a company, is also relevant. This approach is evident from the emergence of skills matrices around 2007 when the Canadian Ontario Securities Commission National Policy 58-201 introduced a detailed individual competency and skills gap analysis of current and potential directors, to be prepared by nomination committees.[83] Along similar lines, Toronto’s stock exchange guidelines require a written board mandate that must address strategic planning, risk identification and the characteristics of who should address this on the board and in management. As a result, skills matrices became prominent in Canada, but remained largely as an internal board and nomination committee tool.[84] In Australia, the ASX had the same initial intentions when it introduced skills matrices in the 2010 iteration of the Australian corporate governance code, meant as a board nomination tool to identify gaps in skills that could necessitate the appointment of new directors.[85]

The 2014 ASX Code, effective from financial years starting on or after 1 July 2014,[86] significantly elevated skills matrices by requiring disclosure of the skills mix and diversity that the board has, or is looking to achieve, without disclosing commercially sensitive information. The ASX’s purpose with this disclosure was to present ‘useful information for investors’ and increase ‘the accountability of the board on such matters’,[87] as is intended by our disclosure instrument. Initially, this radical approach to skills disclosure was seen as a controversial step, and while early adopters such as BHP Billiton disclosed significant information, others presented boilerplate, generic statements.[88] Nevertheless, this disclosure regime is still held as leading governance practice,[89] and is unique in its informational value to shareholders in setting out board skills (Table 5, Question 4, linking board skills to company strategy and risk).

Conceptually, even if it is considered that this disclosure is provided in the aggregate, skills matrices can provide two different perspectives about director skills relevant to the nomination process. First, if the matrix is framed as a historical reflection of the skill-set of the board at a particular point in time, the board can use it as a tool to consider whether a director’s current skills remain relevant and appropriate to achieve the objectives of the company, as an argument in favour of re-appointment. Second, the skills matrix can be used as an aspirational tool and statement of the skills that the board ought to have. In this sense, it guides the director nomination process and acts as a tool to build board capacity by identifying long and short-term gaps that can be addressed in director education programs.[90]

Our research found that there is little published about skills matrix disclosure. But we note a study undertaken by Ernst & Young when skills matrices were first introduced in Australia that analysed this disclosure by 57 ASX 100 first adopters. Of these, 47 companies used a historical perspective in their disclosure, while 10 disclosed aspirational skills for the board. Ernst & Young also ranked the top disclosed skills from these annual reports that are presented in Table 1.[91]

Table 1: Top Disclosed Directors Skills by 57 ASX Boards

|

Financial Acumen

|

98%

|

Risk Management

|

65%

|

|

Industry Experience

|

89%

|

People and Remuneration

|

58%

|

|

Executive Leadership

|

85%

|

Marketing and Customer

|

56%

|

|

Governance

|

76%

|

Finance and Accounting

|

55%

|

|

International

|

73%

|

Capital Management

|

51%

|

|

Strategy and Communication

|

67%

|

Digital and Technology

|

51%

|

The significant informational benefits in company-specific skills matrices will be better understood when considered against the backdrop of the universal theoretical skills required of all directors. As a consequence, we sought to compare our theoretical director skills to those disclosed in Australian skills matrices.

Our Leximancer map of the roles and responsibilities of directors, and our consideration of the specific skills of directors, as set out in the law and in the corporate governance codes that we studied, allowed us to identify a number of universal skills that all directors should have. We supplemented these two theoretical outcomes with the results from the Ernst & Young skills ranking in Table 1 and our initial dataset review, thus enabling us to establish a 15-point theoretical universal director skills base, presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Theoretical Skills Generated from Self Reports and Government Codes

|

Financial Literacy

|

Industry Experience

|

Leadership, Executive Experience or Operational Management

|

|

NED Experience

|

Governance, Corporate Governance

|

International, Global or Geographic Experience

|

|

Communication and Public Relations

|

Risk, Risk Management

|

People/Human Resources (HR), Remuneration

|

|

Digital/IT/Technology/Cyber

|

Mergers and Acquisitions, Capital or Funds Management

|

Compliance, Legal, Regulations and Government Relations

|

|

Board/ASX Experience

|

Strategy, Strategy Implementation

|

Marketing and Customer focus

|

To conduct the comparison and analysis, we created a dataset based on the skills matrices disclosed by the ASX 100 companies in their 2016 annual reports or accompanying corporate governance statements. We added the following variables to this dataset: firm size (by number of employees), industry, firm age, board size and composition (for example, demographics of board members), chief executive officer demographics, and financial data for each company by searching the ASX website at http://www.asx.com.au. We used SPSS Version 24 to analyse the data, using descriptive data analytical approaches.

Within the ASX 100 group, 93 companies disclosed skills matrices. Of the remaining companies, one was headquartered in the UK where there is no skills matrix disclosure, two held primary listings in the US, and one was externally managed. The fifth stated that it had a skills matrix, referencing the nomination committee charter as its source, but this charter is not publicly available, hence this company was excluded from our analysis. The sixth company disclosed that their board deemed this type of detail disclosure inappropriate, but disclosed the following as part of the directors’ skill set: strategic planning, international business, industry experience, financial skills, and funds and investment capital. The seventh company listed some relevant existing skills in its governance statement: industry, financials, regulatory, business acumen, listed/board experience. Representation of these 93 companies per ASX industry classification is presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Industry Classification of Dataset Companies

|

Industry

|

Number of Companies in Datasets

|

|

Consumer Discretionary

|

11

|

|

Consumer Staples

|

7

|

|

Energy

|

5

|

|

Financials

|

18

|

|

Health care

|

6

|

|

Industrials

|

9

|

|

Information Technology

|

2

|

|

Materials

|

19

|

|

Real Estate

|

8

|

|

Telecommunication Services

|

3

|

|

Utilities

|

5

|

Our initial review of the datasets highlighted that while the generally adopted legal skill standard that all directors must meet is that of financial literacy, few companies used this phrasing in their skills matrices. Instead they referred to seemingly higher standards, such as financial acumen or expertise in finance, accounting or auditing as a benchmark. As financial literacy is arguably the only specialist director skill, we took care in using three different terms in our comparison to reflect differences in knowledge and qualifications in relation to financial literacy as shown in Figure 2: financial literacy; financial acumen; expertise in finance/accounting/audit. We also found significant references to capital or funds management in the datasets, often linked to references to mergers and acquisitions, which resulted in us expanding that universal skill to: mergers and acquisitions; capital or funds management. In Figure 2, we present the results of the comparison between the theoretical skills and those disclosed in the datasets.

The overall comparison reveals a number of positive outcomes. First, all boards understood the necessity of financial literacy skills with a representation of the three concepts we used in each of the matrices, indicating a seemingly high financial literacy standard. Second, considering ‘industry experience’ and ‘risk/risk management’ together, boards seem to have the necessary background to consider risk appropriately. Third, boards understand the significant value in experience that extends across five disclosed skills areas: NED experience, board/ASX experience, industry experience, operational experience and geographical experience. Last, directors’ ability to comply with laws and regulations through good governance is also well understood in reference to the high presence of skills related to governance/corporate governance, and compliance/legal/regulations/government relations.

On the negative side, despite directors’ clear focus on strategy, fewer than three-quarters of the companies disclosed strategy or strategy implementation as a key skill for directors. Relatedly, directors are also tasked with formulating strategy as a response to risk. Fewer than three-quarters of boards disclosed risk and risk management as a key skill. Taking risk and strategy skills results together, our comparison highlights this as a key area for skills development in Australian boardrooms that ought to be considered more prominently in director nominations. We submit that board leadership must revolve around the appropriate business strategies that yield targeted returns and takes into account the associated risks. Risk and directors’ ability to manage it has been an important element of civil proceedings brought by the Australian corporate regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (‘ASIC’).[92] Any deficiencies in board skill to address risk increases the personal risk of directors, is likely to result in renewed ASIC attention, and, hence, must be a key consideration in director nominations. We also highlight that while ongoing rapid technological change affects all companies significantly and pervasively, just over half of boards regarded technology and cyber fluency as a key board skill. The potential that boards may not have the skills to appropriately address the impact of technology risk on strategy is a major concern.

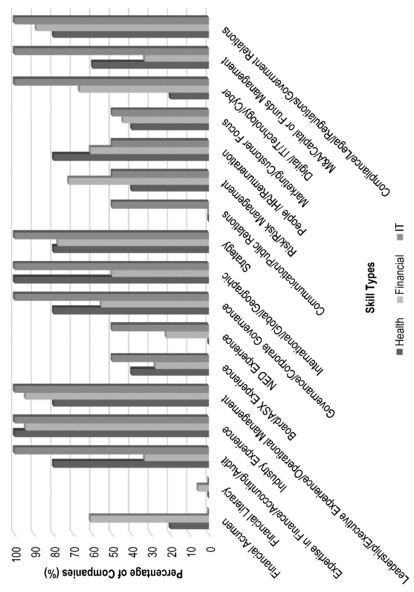

We recognise that technology and cyber fluency may have more relevance in three key industries: information technology (‘IT’) (due to the nature of their core business), health care (as significant data breaches in this sector, put the most personal of information at risk), and financials (due to the extraordinarily large proportion of the population in Australia whose personal and banking information is at risk). The comparative results of these three industries are presented in Figure 3. The IT sector fared well with regards to technology related skills. However, the results in the health and financial industries are concerning, and probably not in line with the expectations of stakeholders. ASIC sees cyber resilience as an essential element of director care and diligence, and, as stated in its corporate plan, actively monitors boards’ abilities to manage technology risk.[93] Our results indicate significant director skills deficit, even in technology-rich companies, to manage technology risk.

Figure 3: Percentage of Companies with Skills from the Health, Financial and IT Sectors

To understand the relationships between company size, age and industry with the prevalence of different skills and skill levels, we conducted Spearman’s correlational analysis.[94] Correlational analysis indicates how well two variables relate, that is, the strength and direction of association between the variables. Spearman’s correlation has an advantage over other techniques in that it does not presuppose a linear relationship between variables, which is useful when analysing categorical variables. The value of a correlation coefficient (indicated as r below), varies between -1, which is a negative perfect relationship, and +1, which is a positive perfect relationship. The significance of this relationship is indicated by the p-value below, and can be interpreted as the probability of obtaining a correlation. To illustrate, where p < .05, which is generally viewed as an acceptable cut-off point, it means that the probability of obtaining a particular correlation coefficient by chance is fewer than five times out of 100. For this analysis we only accepted results where that was the case, which led us to the following conclusions. Larger companies were more likely to have NED experience (r = .389, p = .009) and as expected, larger boards (r = .395, p = .008). Companies with a larger board were more likely to have the chief financial officer as a board member (r = .225, p = .049) and boards with chief financial officer members generally had a higher number of skills represented in the board (r = .214, p = .014). We also found a strong correlation between firms with expertise in finance and accounting and those with skills in IT and digital related areas (r = .283, p = .039).

To further explore the importance of industry for different board skills, we conducted chi-square tests of difference between companies in a particular industry with those outside that industry. The chi-square statistic (indicated by ) reveals how likely it is that the difference in a particular variable (for example, a particular board skill) occurs by chance between two sets of data (for example, between one industry as compared to the remaining industries). We found that in the finance industry, financial acumen ( = 2.983, p = .084), expertise and finance ( = 3.748, p = .053), corporate governance ( = 4.660, p = .031), and capital or funds management ( = 10.291, p = .001) skills were more likely to be present, albeit only marginally so in the case of the first two skills, where p ≤ .05 is considered to be the cut-off for significance. The only other differences that we observed were in the case of the IT industry, where NED experience ( = 7.973, p = .005) and corporate governance ( = 2.929, p = .087) were more likely to occur.

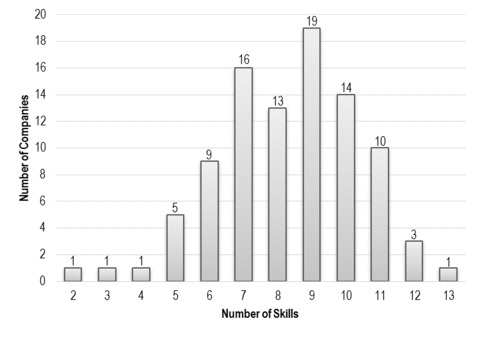

As the theoretical universal director skills shown in Table 2 presents our analysis of the minimum skills directors should have, we also performed a skills count as presented in Figure 4. None of the ASX 100 companies disclosed all or 14 of the minimum skills established through our analysis, one disclosed 13 skills, three disclosed 12 skills, thus strengthening our case for an integrated skills disclosure model that would present evidence that the board acted diligently in nominating directors.

Figure 4: Number of Skills in Table 2 Reported per Company

Last, beyond the comparison to our theoretical universal director skills base, we were also interested to determine whether skills around the contested concept of corporate social responsibility (health and safety, economic, social and environmental, and sustainability skills) are regarded as important at the largest listed companies in Australia. Our analysis showed that 37 of the ASX 100 companies in our dataset have included these skills in their matrices.

Our comparison and analysis provide evidence that skills matrix disclosure without contextualising it against a theoretical, universally required director skill set provides insufficient assurance to the shareholders that incumbent-proposed directors meet a minimum skills standard. We note four other concerns with using skills matrices in isolation. First, it may be that the development of the matrix is framed through a particular lens, reflecting particular corporate concerns – geography, leadership, the distinct skills of executives and NEDs, strategic thinking[95] – which results in too great a level of subjectivity that may not be apparent to users. Second, there is a risk that proxy advisers can use the disclosed skills matrix to justify or explain their vote against director appointments.[96] Third, the matrix is the result of self-evaluation or internal benchmarking. Last, if users are not informed about the process employed to formulate the skills matrix and how it should be used, it may not be apparent whether it presents existing, required or aspiration skills (Table 5, Question 2, the process to ensure nominees have the minimum skills). If the matrix represents current or historical board skills, it can be used to evaluate the incumbent board. If it is intended as an aspirational tool, it can guide director nominations. But both processes remain within the purview of the board.

We considered whether the 93 disclosed matrices in our study represented historical or aspirational skill sets. To do so, we classified those matrices that clearly stated that it was a summary of the board’s current skills as a historical representation. If a matrix presented statistics on how many directors possessed each listed skill, the matrix was also classified as historical. In contrast, if a matrix clearly stated it was used as a guide to assess the current directors, it was classified as aspirational. Similarly, if the disclosure stated that the board viewed the particular skills and qualifications as important, necessary or a minimum requirement, these were classified as aspirational. That left a number of hybrid matrices in which the skills were desired or seen as a necessary minimum, and that was then classified as hybrids since these statements seemed to indicate that the skills listed were regarded as the minimum standard. On this basis, we found a mixed conceptual approach to skills matrices in Australia, shown in Table 4, which may not be that apparent to users.

Table 4: Number of Companies per Conceptual Approach to Skills Matrices

|

Total

|

Historical

|

Hybrid

|

Aspirational

|

|

93

|

50

|

22

|

21

|

Our analysis of Australian skills matrices show that director nomination processes can benefit in several ways from the informational value embedded in aggregate board skills disclosure, even if viewed in isolation. But directors are appointed individually, not collectively. Therefore, we next proceed to consider what other information about incumbent directors and nominees are disclosed.

The corporate governance codes that we analysed recommend significant disclosure of current and potential directors’ experience, qualifications and time availability. For example, the Singapore Code 2012 suggests disclosure of each director’s academic and professional qualifications, shareholding in the company, the committees they serve on, other directorships and possible conflicts of interest.[97] The UK Code requires disclosure of similar biographical details of those put forward for election or re-election.[98] Similarly, the South African code requires disclosure of each director’s qualifications, status as executive or NED, age, professional memberships and experience, which is further supplemented by disclosure of whether the board is satisfied that its composition reflects an appropriate mix of knowledge, skill, experience, diversity and independence, and of the targets for and progress made on race and gender board representation.[99] Seen in isolation, such disclosures allow an assessment of the potential to act as a director, provide evidence of acquired knowledge and experience, and assist the board in assessing whether nominees are overextended due to other commitments. But, seen in isolation, this type of disclosure does not allow for ease of comparison against universally required skills, nor of a nominee’s suitability to be a director in the specific company (Table 5, Question 13, relevance of nominee biographical information to company strategy and risk).

Then, turning to a different aspect, shareholders also have information about the strategic direction of the company, the key objectives that must be achieved, the general business environment in which the company operates, significant changes that have, or may affect the business, and the principal risks that affect the company. This disclosure is currently achieved in three ways: voluntary benchmark disclosure as described in corporate governance codes,[100] disclosure mandated through the listing rules of stock exchanges,[101] and compulsory disclosure as is required by law, often in directors’ reports,[102] or in a more focused manner in the strategic report required in the UK.[103] The usefulness of this disclosure lies in that shareholders would be able to gain an understanding of how the directors plan to achieve long-term shareholder wealth given the main business risks. This in turn should inform the directors’ nomination of board candidates (Table 5, Questions 4, 7 and 12, linking skills to company strategy and risk).

Our analysis showed that significant information is already disclosed detailing the biographical information of directors and nominees. On the other side of the spectrum, there is disclosure of the strategic objectives and goals that the directors have set for the company, and information about the key risks that the company faces. In Australia, there is also disclosure of board skills in the aggregate, either as a historical reflection, aspirational forecast or presented in a mixed approach in a skills matrix. Separate from this disclosure, there will be a closed record, available to the board, of the process to nominate directors and the evidence and results of the evaluation of the board and each individual director.

With this information already available, prepared for different purposes, our recommendation that an additional integrated statement be prepared and disclosed by the board is unlikely to be onerous or costly, particularly seen against the commercial benefits to the company of its preparation. Our integrated statement seeks to publicly clarify how the directors have diligently applied themselves to nominate directors who have skills appropriate to the strategy and future risks within the company (Table 5, Questions 4, 5, 7 and 9).

First, there ought to be disclosure of the minimum skills (legally and practically) that the board believes all the directors must have and how the board ensures whether (or the extent to which) current directors and nominees meet this standard (Table 5, Question 1). Establishing a company-specific baseline of skills against which the directors can apply care and diligence when they nominate candidates reduces their personal risk, reduces nomination bias, and increases managerial and practical control standards, returning commercial benefits to the company. Continued professional development for directors can address shortcomings.[104] Board engagement with a minimum standard also has the potential to reveal a significant number of shortcomings for one director or nominee, and for the board collectively, before it has negative implications for the company, its shareholders or individual directors. Our intention with this disclosure is not that it should act as a checklist against which each director or nominee is measured, but that shareholders may take assurance that the board has engaged with minimum skills as they nominate and self-evaluate, and as they continuously critically evaluate what is required to direct the business generally given that business circumstances continually change.

Second, there is already disclosure of the strategic direction of the company, the objectives that the board wants to achieve, information about the general business environment, significant changes thereto and the principle risks in the company. Therefore, we argue that it would be possible for boards to engage with and prepare disclosure that details the key director skills which are most critical to achieving the objectives and addressing each principle risk. In Australia, since aggregate director skills are already disclosed in a matrix, we propose that skills matrices should be expanded to indicate how board skills relate to strategy and risk. From an ease of use perspective, since skills matrices are presented in a condensed format, often as a list or in a table, the addition of a separate column detailing the strategy and risk aspects addressed by each skill will provide significant insights into how the board applied themselves diligently to director nominations. From a board perspective, a conscious consideration of the extent to which a director’s or nominee’s skills are suited to address key current and future risks in the company will have several significant commercial benefits that outweigh the cost of preparing our proposed integrated skills-related disclosure.

The first benefit is that this process will highlight any disconnect between the important risks in the company and directors’ potential to address these based on their skills. Such a disconnect is evident from our analysis of Australian skills matrices that highlighted that despite technology risk being significant and pervasive in all companies, more than half of boards did not disclose technology skills in their matrices. By paying focused attention to the risk-skill intercept, directors will be able to take proactive steps to strengthen their ability to guide risk management, seen as a key aspect of their role (Table 5, Questions 4, 5 and 8).

Second, by paying focused attention to the future risk-skills intercept, the board will be able to plan for and have sufficient time to recruit nominees with the skills to provide the company with a competitive edge in dealing with future risks. The emerging trend of specialist digital director appointments at large companies across the globe is an example of how future risk and director skills intersect to create value (Table 5, Question 6).[105]

Third, we identified board renewal as an important aspect of Theme 1 from our Leximancer map. If boards continuously consider the intersect between skills and significant or expected changes in the business environment, they will be able to assess whether there is sufficient board renewal, which is critical to performance if they are to be well-positioned to face new challenges (Table 5, Question 10).[106]

The last advantage concerns diversity, which is an important aspect of board composition. Diversity for the sake of it holds fewer benefits than board diversity which is linked to the future direction of the corporation, its principle risks and expected significant future changes. Board engagement with the risk-skills intercept can be instructive to consider the commercial benefits of diversity factors in director nominations (Table 5, Question 12).

The third aspect of our integrated disclosure instrument seeks to use the already available biographical information about directors and nominees differently. We suggest that it should be linked to the minimum skills that the board assess are relevant to all directors, as well as to the key risks within the company. This approach does not mean that biographical information must be used as a checklist. Rather, a disclosed link enables a focused assessment of the extent to which the current or potential suitability of nominees has been taken into account in the nomination process, as is required in the case of FTSE 350 NEDs.[107]

Taken together, the three elements of our integrated skills disclosure instrument presents a concrete expression of the conceptual care and diligence that directors apply in nominating board candidates, as they act as the shareholders’ agents. Our instrument does not propose that the roles, responsibilities or skills of directors should be amended nor addressed differently with a view to return appointment rights to shareholders. Neither do we suggest that there is any particular standard for the skills that all directors should have. Rather, our instrument supports the autonomy of the board and that they are best placed to decide which skills are important to their vision of how the company should be directed. Our instrument facilitates accountability through disclosure. Even if shareholders decide not to vote for nominees (which rarely happens), or opt not to read or rely on the instrument, the significant commercial benefits to the company in engaging in a more focused manner with the strategy-risk-skills intercept supports its wide implementation. We formulate our instrument’s disclosure elements as a checklist of questions, presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Integrated Skills Disclosure Instrument

|

Question

|

How Is This Achieved?

|

|

1. Are shareholders able to identify what the minimum skills of all

directors should be?

|

|

|

2. Did the board inform shareholders about the processes to ensure that all

nominees have the minimum skills required of all directors?

|

|

|

3. Is there clear disclosure that each nominee is financially

literate?

|

|

|

4. Is there clear, concise, focused disclosure of the aggregate skills

required of the board, and how these skills relate to the company’s

strategy and each of the disclosed key risk categories? Have each of the key

risks been addressed by specific skills?

|

|

|

5. If directors stand for re-election, is there clear disclosure of the

reasons why their skills are suited to address the current

and future risks in

the company?

|

|

|

6. Is there clear disclosure of the future skills required of directors to

address future risks such as those associated with technology?

How will the

shareholders know which of the nominees have these skills?

|

|

|

7. Will shareholders know how the existing skills of the board fit into the

future strategy set for the company?

|

|

|

8. How is the experience of nominees relevant to the strategic objectives

and risks in the company?

|

|

|

9. Will shareholders be able to form an opinion about how the directors aim

to govern, manage and direct the corporation by considering

the skills required

of the board?

|

|

|

10. Will shareholders be able to determine how nominees are able to make a

contribution to board renewal?

|

|

|

11. Are shareholders able to see how nominees’ experience,

particularly industry experience, is relevant to their role?

|

|

|

12. If a nominee makes the board more diverse, in what way does their

diversity relate to the company’s strategic objectives?

|

|

|

13. Has the biographical information disclosed of nominees explained how

their qualifications, professional memberships, gender and

time availability (in

reference to other positions they hold) relate to the company’s strategy

and key risks?

|

|

|

14. Will shareholders have access to all these relevant aspects prior to

the AGM so that they have sufficient time to appoint and

instruct a proxy?

|

|

As foreshadowed in the introduction, we have already outlined the commercial benefits of the application of our instrument, which reinforces the board’s autonomy to decide how companies should be run. There are two further benefits that deserve consideration associated with rational shareholder apathy and the position of minority shareholders particularly in an Australian context.

Information is central to the rational apathy theory which dictates that shareholders in widely-held companies will not act to monitor and discipline the directors since their cost to obtain appropriate information, to analyse it and to find time to attend meetings to vote is not outweighed by the benefits. Information costs are therefore borne by the few who can afford it and there is little incentive for them to share their costly information, resulting in a degree of distorted corporate control to the side of the board and some institutional investors, leaving particularly minority shareholders largely (but rationally) outside of the process.[108] Our instrument addresses this asymmetry through its focused disclosure, which is an expression of the way in which the directors apply care and diligence in acting as agents for the shareholders in relation to their appointment rights.

In Australia, it is not only the cost of obtaining information that results in rational apathy for shareholders, but also the timing of annual general meetings (‘AGMs’). The vast majority of ASX listed companies report in a six to eight week peak proxy season in October and November.[109] Institutional investors regularly use the services of proxy firms to vote on their behalf on matters, including the appointment of directors, since they are unable to attend all meetings.[110] However, this is an unaffordable option for minority shareholders with diversified portfolios. We found limited recent data about shareholder voting in Australia. Research conducted in the 2016 reporting period reveal that the average proportion of all shares voted per resolution across ASX 300 companies was just under 67 per cent.[111] But traditionally, the number of shareholders who attend AGMs is low. Among the ASX 200, the number of AGMs attracting fewer than 100 shareholders increased from 23.2 per cent in 2001 to 41.3 per cent in 2007. Among the same group, AGMs attracting more than 300 shareholders fell from 35.7 per cent in 2001 to 11.1 per cent in 2007.[112] In so far as director appointments are concerned, in 2015, shareholder resolutions to remove directors were among the top five resolutions in Australia, China, Hong Kong, Japan and Singapore, but the highest percentage of votes were cast against these resolutions in favour of the incumbents.[113] In the 2009 and 2010 reporting seasons, looking at 471 ASX main board company resolutions, the average dissent on director appointment resolutions put forward by management was only 3.59 per cent.[114]

We propose no solution for diversified minority shareholders so that they are able to attend multiple AGMs during the peak reporting season to vote for director appointments. However, our instrument provides shareholders with assurance that the directors have acted with care and diligence as their agents in the nomination process through valuable information disclosed to them at no further cost to them. If the shareholders choose to vote on director appointments, our instrument, when disclosed before the AGM, has the capacity to facilitate informed participation in director appointments using a different avenue prior to the AGM. We have in mind that since our instrument better informs shareholders about nominees prior to the AGM, they can express their views on the suitability of nominees by appointing a proxy and instructing the proxy to vote in a specific way on director appointments (Table 5, Question 14).[115]

Over the past decade, several associated shareholder participation problems in director elections have become prominent in Australia: a lack of useful information upon which to base board voting decisions, insufficient emphasis on nominees’ experience and qualifications for the role,[116] and a lack of transparency about the appointment process.[117] Our instrument effectively addresses all of these concerns. Research conducted by the Australian Institute of Company Directors further reveals that institutional investors feel there is too much emphasis on remuneration and advisory two-strike ‘say on pay’ votes, diverting attention from three key issues, one of which is the broader question of the capability of directors.[118] Similarly, the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors’ 2015–16 annual report stated that their members will more critically examine board structures to ensure three things: diversity, independence, and that directors are held accountable for their prior decisions.[119] While factors such as experience, qualifications and diversity are relevant at election, foremost, they must play a significant part in determining who should be nominated as a director.

Then, the extent to which minority shareholders (who we regard as typically individual retail investors) are able to play an effective role in corporate governance generally, and specifically in director appointments, is limited. Minority shareholders face the real risk that even if they attend general meetings and vote against nominees, the matter has already been settled through proxy votes. Nevertheless, the relative position of minority shareholders in Australia is significant when compared to other countries. Australia boasts one of the highest rates of individual share ownership in the world,[120] and has a strong ranking for minority shareholder protection when compared, for example, to the UK and the United States.[121] The 2017 ASX Australian investor study revealed that 31 per cent of the 11.2 million adults in Australia owned publicly traded shares directly outside of their institutional superannuation (pension) funds and that they were actively transacting since 40 per cent of them had done so in the 12 month review period of the study. The strong presence of individual retail minority shareholders is further underscored when it is considered that 1.1 million Australians are members of self-managed superannuation funds that hold about 45 per cent of their investments in the form of shares.[122]

On this basis, by extending skills matrix disclosure through the application of our integrated disclosure instrument, we advance two key propositions. First, that increased minority shareholder participation in the key decision to appoint directors can be influential in the financial markets in Australia. Second, that the implementation of our instrument has the potential to increase the country’s overall financial literacy levels since it provides all shareholders with useful insights into corporate governance and how the directors act as their agents.

Lastly, we note that our instrument addresses information or disclosure overload, which, as a result of regulatory compliance, has become a recent feature of corporate governance. The instrument does this by providing useful information that links director skills to company strategy, governance and risk. While integrated reporting presents the links between organisational strategy, governance and financial performance, and social, environmental and economic contexts within which a company operates,[123] our instrument is succinct and focused, making it meaningful.

We conclude first with the affirmation that shareholders have a fundamental right to vote for the appointment of directors, irrespective of the size of their shareholding. Second, we affirm our support for the argument that it is the board that must decide how a company should be run. As a consequence, the incumbent directors should have the autonomy to select and nominate those to be appointed to the board. While the shareholders’ appointment role has thus become one of merely confirming the incumbent-proposed slate of nominees, greater accountability over the nomination process provides a discipline over the board so that there is a concrete expression of how the incumbent directors apply care and diligence as they effectively act as the agents of shareholders.

Without altering recommended practices describing the roles, responsibilities or skills of directors, and director nomination or evaluation processes, our integrated skills disclosure instrument uses information already available to the board in a concise and focused manner. Even if shareholders choose not to use the instrument, its benefit is much wider and lies significantly in the board’s specific engagement of the intercept between their skills and company strategy and risk.

* Lecturer, TC Beirne School of Law, University of Queensland.

** Professor in Strategy, UQ Business School, University of Queensland.

1 Michael C Jensen and William H Meckling, ‘Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure’ (1976) 3 Journal of Financial Economics 305, 308–11.

[2] J Kirkbride, S Letza and X Sun, ‘Corporate Governance: Towards a Theory of Regulatory Shift’ (2005) 20 European Journal of Law and Economics 57, 58, 64–5, 67.

[3] Dimity Kingsford Smith, ‘Governing the Corporation: The Role of “Soft Regulation”’ [2012] UNSWLawJl 16; (2012) 35 University of New South Wales Law Journal 378, 379, 387, 389–91; Jeroen Veldman, ‘Self-Regulation in International Corporate Governance Codes’ in Jean J du Plessis and Chee Keong Low (eds), Corporate Governance Codes for the 21st Century – International Perspectives and Critical Analyses (Springer, 2017) 77, 82; Junhai Liu, ‘Globalisation of Corporate Governance Depends on Both Soft Law and Hard Law’ in Jean J du Plessis and Chee Keong Low (eds), Corporate Governance Codes for the 21st Century – International Perspectives and Critical Analyses (Springer, 2017) 275, 276–7; ASX Corporate Governance Council, ‘Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations’ (Australian Securities Exchange, 2014) 3 (‘ASX Corporate Governance Principles’). See generally Robert P Austin and Ian M Ramsay, Ford, Austin and Ramsay’s Principles of Corporations Law (LexisNexis Butterworths, 16th ed, 2015) 25, 385; Jean Jacques du Plessis et al, Principles of Contemporary Corporate Governance (Cambridge University Press, 3rd ed, 2015) 189–91, 194–208.

[4] Andrew Keay, ‘Exploring the Rationale for Board Accountability in Corporate Governance’ (2014) 29 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 115, 143, 145; Praveen Kumar, Nisan Langberg and K Sivaramakrishnan, ‘Voluntary Disclosures, Corporate Control, and Investment’ (2012) 50 Journal of Accounting Research 1041, 1042–3. See generally Austin and Ramsay, above n 3, 25–6, 383–5.

[5] Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 249N(1).

[6] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ‘Board Member Nomination and Election’ (Report, 2012) 11, 28.

[7] See, eg, Daniel Attenborough, ‘The Vacuous Concept of Shareholder Voting Rights’ (2013) 14 European Business Organization Law Review 147, 149, 151, 155–6; John C Coffee Jr and Darius Palia, ‘The Wolf at the Door: The Impact of Hedge Fund Activism on Corporate Governance’ (2016) 41 Journal of Corporation Law 545, 553, 556–8; Geof Stapledon et al, ‘Proxy Voting in Australia’s Largest Companies’ (Research Report, Centre for Corporate Law and Securities Regulation, The University of Melbourne, and Corporate Governance International, 2000) 11–12.

[8] Sorin Blaga, ‘Australian Corporate Governance and Distribution of Power’ (2011) 4(1) Review of Economic Studies and Research Virgil Madgearu 5, 18.

[9] Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 249L(2), 250V, 300A(1)(g). See generally Puspa Muniandy, George Tanewski and Shireenjit K Johl, ‘Institutional Investors in Australia: Do They Play a Homogenous Monitoring Role?’ (2016) 40 Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 266, 268–9.

[10] Geof Stapledon et al, above n 7, 18–22.

[11] ASX Corporate Governance Principles, above n 3, 26.

[12] See, eg, Financial Reporting Council, ‘The UK Corporate Governance Code’ (April 2016) 11 (‘UK Code’); Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ‘G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance’ (Report, September 2015) 22–3 (‘G20/OECD Principles’); Szymon Kaczmarek, Satomi Kimino and Annie Pye, ‘Antecedents of Board Composition: The Role of Nomination Committees’ (2012) 20 Corporate Governance: An International Review 474, 474–5; P M Vasudev, ‘Law, Economics, and Beyond: A Case for Retheorizing the Business Corporation’ (2010) 55 McGill Law Journal 911, 944–5.

[13] See, eg, G20/OECD Principles, above n 12, 26; United States Securities and Exchange Commission, ‘NASD Rulemaking: Rule 4350(c)’ (Release No 34-47516, 17 March 2003).

[14] See, eg, PricewaterhouseCoopers South Africa, ‘Non-executive Directors: Practices and Remuneration Trends Report’ (January 2017) 23; Australian Council of Superannuation Investors, ‘Board Composition and Non-executive Director Pay in ASX200 Companies’ (Research Report, November 2016) 11–12 <https://www.acsi.org.au/images/stories/ACSIDocuments/detailed_research_papers/BoardCompandNEDPayTop200Companies2015.Nov16.pdf >; Korn Ferry Hay Group, ‘Non-executive Directors in Europe 2015 – Pay Practices, Structures and Diversity of Leading European Companies’ (Report, 2015) 12.

[15] Joanna Tochman Campbell et al, ‘Shareholder Influence over Director Nomination via Proxy Access: Implications for Agency Conflict and Stakeholder Value’ (2012) 33 Strategic Management Journal 1431, 1435–8; Michael E Murphy, ‘The Nominating Process for Corporate Boards of Directors: A Decision‑Making Analysis’ (2008) 5 Berkeley Business Law Journal 131, 148, 164–5. See generally Stephen M Bainbridge, ‘The Politics of Corporate Governance’ (1995) 18 Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy 671, 674–5.

[16] See, eg, UK Code, above n 12, 11. See generally ICSA: The Governance Institute and Ernst & Young, ‘The Nomination Committee – Coming Out of the Shadows’ (Report, May 2016) 9, 13.

[17] Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services, Parliament of Australia, Better Shareholders – Better Company: Shareholder Engagement and Participation in Australia (2008) 58 [4.71] (‘Better Shareholders Report’).

[18] Jennifer G Hill, ‘The Rising Tension between Shareholder and Director Power in the Common Law World’ (2010) 18 Corporate Governance: An International Review 344, 350.

[19] KPMG International Cooperative and Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, ‘Balancing Rules and Flexibility – A Study of Corporate Governance Requirements across 25 Markets’ (Research Report, November 2014) 16, 19, 30–1, 33, 69; G20/OECD Principles, above n 12, 3.

[20] UK Code, above n 12, 9, 11, 18.

[21] Ibid 14.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid 15.

[24] Ibid 11–28.

[25] Monetary Authority of Singapore, ‘Code of Corporate Governance’ (6 August 2018) [5]–[5.2] (‘Singapore Code 2018’).

[26] ASX Corporate Governance Principles, above n 3, 13.

[27] Institute of Directors in Southern Africa, ‘King IV – Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa 2016’ (November 2016) pt 5, 56 [60], 58 [71]–[75] (King IV Code’).

[28] See, eg, Reinier Kraakman et al, The Anatomy of Corporate Law a Comparative and Functional Approach (Oxford Scholarship, 3rd ed, 2017) 62, 63.

[29] ASX Corporate Governance Principles, above n 3, 16.

[30] See, eg, Jay Cai, Tu Nguyen and Ralph Walkling, ‘Director Appointments – It Is Who You Know’ (Paper presented at 28th Annual Conference on Financial Economics and Accounting, Fox School of Business, Temple University, 11 November 2017) 8–9, 31–2; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ‘Board Member Nomination and Election’, above n 6, 13, 19–20; Love Bohman, ‘Bringing the Owners Back In: An Analysis of a 3-Mode Interlock Network’ (2012) 34 Social Networks 275, 276–7, 283–6.

[31] Donald C Langevoort, ‘The Human Nature of Corporate Boards: Law, Norms, and Unintended Consequences of Independence and Accountability’ (2001) 89 Georgetown Law Journal 797, 810.

[32] Sally Wheeler, ‘Independent Directors and Corporate Governance’ (2012) 27 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 168, 176, 179, 183–6; Langevoort, above n 31, 811; Keay, above n 4, 134.