University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

IS THE CLASSIFICATION OF ANIMALS AS PROPERTY CONSISTENT WITH MODERN COMMUNITY ATTITUDES?

GEETA SHYAM[*]

Animals have legally been classified as property under Australian law, at least since colonialism. In recent times, however, the appropriateness of this legal status has come to be questioned. The debate between abolitionists and welfarists has become increasingly prominent; nevertheless the largely theoretical debate remains confined to the scholarly and legal world. This article reports on the results of an empirical study that took the issue to the Victorian public, measuring the level of awareness and agreement about the property status of animals. The study found that most people are unaware of the legal status of animals, and that the property status of at least some animals may not be consistent with contemporary attitudes. The results of the study further confirm that different kinds of animals are perceived differently, although they are rarely viewed as property. The findings enrich the abolitionist debate with empirical evidence while also highlighting educational opportunities.

‘It's not hard to make decisions when you know what your values are’.[1]

In recent years we have seen a number of attempts by Australian lawmakers to bring to an end practices that are harmful to animals. This includes a ban on the live export of cattle[2] and a ban on greyhound racing in New South Wales.[3] Although the bans proved to be only temporary, the underlying triggers for the bans do suggest that society is becoming less tolerant of animal cruelty and more interested in ending practices that are patently harmful to animals.

Both these attempted bans followed televised exposés by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Four Corners program and the subsequent display of public outrage.[4] Within days of the exposé on live exports in 2011, thousands of Australians signed an online petition to ban live export.[5] In fact, the public response was so intense that the websites for the RSPCA, Animals Australia and GetUp! crashed within hours of the Four Corners episode airing.[6] GetUp! National Director Simon Sheikh described the online petition as the fastest growing petition he had ever seen, noting that over 35 000 Australians had signed the petition within a period of five hours on the day after the episode aired.[7] The Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry was as a result pressured into suspending the live export of cattle to Indonesia. The federal government was prompted to act swiftly in light of such public response, even though the ban was short-lived.[8]

In the case of greyhound racing, the public reaction led to the creation of a Special Commission of Inquiry, headed by former High Court judge, Michael McHugh AC QC. The Inquiry found that the greyhound racing industry had lost its social licence to operate.[9] While the Special Commission noted the difficulty in precisely defining ‘social licence’, it accepted that the concept involves community expectations that can shift overtime.[10] The Commission accordingly expressed its view that ‘the industry has lost the integrity-based trust of the community’ as a result of the cruelties exposed.[11] The New South Wales Government responded to the report by passing legislation that would ban greyhound racing in the state, although this ban too was later revoked.[12] Irrespective of the setbacks, however, these examples illustrate the Australian society’s growing conscience for animal interests, and lawmakers’ corresponding bids to reflect these community values within the legal system. Ultimately, such growing public conscience paves the way for more progressive animal welfare laws.

Notwithstanding the public outcry that followed the two exposés, empirical evidence of community standards with respect to the welfare of animals is scarce.[13] There is an even bigger evidentiary gap regarding whether Australians support a foundational feature of Australian law: the classification of animals as property. This article contributes towards filling the evidentiary gap in this space, and provides additional context to existing literature on this topic. It reports on the results of a small empirical study that surveyed community attitudes towards the property status of animals. The survey, undertaken in Melbourne and regional parts of Victoria between December 2013 and July 2014, ascertained whether the respondents were aware of animals’ property status and whether they agreed with the status. It also recorded respondents’ attitudes towards three different categories of animals – pet animals, farm animals[14] and wild animals. The survey found that most respondents were unaware that animals are legally classified as property, and that most respondents did not agree with the property status of some or all animals. Further, the survey found that most respondents did not view animals as property, although they hold different sentiments towards different kinds of animals.

The results of the survey indicate that the legal status of animals is, to some extent, inconsistent with contemporary attitudes in Victoria. Moreover, they suggest that the Victorian community holds different attitudes towards different categories of animals. Additionally, the results reveal a lack of public awareness about the property status of animals, highlighting that there may be value in public education or awareness raising programs regarding the current legal status of animals. This education is crucial as it is difficult to have a meaningful discussion about whether the legal status of animals reflects community values if the majority of people lack an awareness of what the legal status of animals is.

This article begins by providing context to the survey. Part II thus provides a summary of contemporary debates surrounding the legal status of animals. Here, arguments for and against abolishing the property status of animals are briefly reviewed. Part III explains the relationship between law and community attitudes, thereby highlighting the importance of this study. It then provides an analysis of the survey data. In Part IV, the article suggests pathways and directions for further research to build on this new data. It highlights educational opportunities and emphasises the need to grow scholarship in this area. It further suggests that this study should be replicated on a larger scale so that attitudes towards the legal status of animals can be understood and monitored throughout Australia. Finally, Part V provides a conclusion.

The property status of animals in Australia is a legacy of the colonial common law system, which in turn was inspired by Roman Law.[15] A tripartite system existed under Roman Law that categorised everything as either persons, things or actions.[16] Within this system, animals were classed as things.[17] The legal treatment of animals as things has continued in Australia despite developments in scientific knowledge and philosophical views about animals. A distinction is drawn, however, between the legal status of domesticated and wild animals. While the former are subject to absolute property, only qualified property can exist in the latter.[18] Thus, under the common law, property cannot exist in wild animals if they are not in the possession or control of any person.[19]

Today, the property status of animals is reflected in various pieces of federal and state/territory legislation. For example, animals are included within the definition of ‘goods’ under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). The Crimes Act 1958 (Vic), which makes provisions with respect to the theft of wild animals, states that ‘[w]ild creatures, tamed or untamed, shall be regarded as property’.[20] Language equating animals to things is even enshrined in some animal welfare legislation, which label farm animals as ‘stock animals’.[21]

It is only in relatively recent times, since the publication of Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation,[22] that the legal status of animals has come under the microscopes of some scholars and lawyers.[23] Some of these scholars and legal practitioners, often referred to as abolitionists, assert that the property status of animals should be abolished and offer different approaches and reasons for doing so. Opponents of the abolition movement maintain that the property status of animals should be retained while improved outcomes for animals are pursued through better animal welfare standards. They reject the abolitionist approaches, in part because society would not approve of such a change.[24]

Gary Francione, a key figure amongst the abolitionists, calls for the abolition of all forms of animal use.[25] He argues that institutionalised animal exploitation should cease, and that animals should no longer be produced for the purposes of humans.[26] Crucial to this change is the abolition of their property status, because it is this status that underpins all forms of animal exploitation.[27] Instead, Francione asserts that the law should recognise the primary right of animals not to be treated as property.[28] According to Francione, the animal welfare framework, which is premised on the property treatment of animals, is fundamentally flawed and incapable of adequately protecting the interests of animals.[29] It allows trivial human interests, such as in entertainment, sport and cosmetics, to override the more substantial interests of animals in living and avoiding suffering.[30] Francione claims that although the welfare model attempts to balance human interests with animal interests, it is an unfair balancing tool that is skewed towards human interests: ‘When the legal system mixes rights considerations with utilitarian considerations and only one of two affected parties has rights, then the outcome is almost certain to be determined in favour of the rightholder’.[31]

In Francione’s opinion, the welfare model is always going to result in the interests of a rights-holder trumping the interests of property, which do not have rights.[32] Thus, the welfare model cannot effectively protect the interests of animals, and even facilitates their exploitation.[33] Francione therefore proposes that the only way to adequately protect the interests of animals in law is to abolish their property status and to recognise their right not to be treated as property.[34]

There are significant social, political and economic challenges to what Francione proposes. Francione himself admits that an alternative legal status for animals would ‘entail dramatic economic and social consequences’ because of human society’s economic dependence on animal exploitation.[35] The cessation of all animal use would require the entire population to stop consuming all animal products, as well as to stop using all services involving animals. Humans would also be unable to own pets. Businesses and the economy would no doubt suffer significant losses as a result of these changes. Indeed, the exact nature and extent of changes forced by the abolition of the property status of animals have not been fully documented so far. This in itself highlights the enormous uncertainty that would accompany the abolition of the property status of animals. In light of such uncertainty and the significant overhaul of lifestyles that would be forced by the abolition of the property status of animals, it is difficult to gauge the extent to which Francione’s proposal would enjoy community support in present times. A lack of community support can be problematic because, as explained in Part III below, prevailing community attitudes often influence the content and successful implementation of law and legal change.

Another abolitionist, Steven Wise, is more wary of the ‘physical, economic, political, religious, historical, legal, and psychological obstacles’ that impede progress.[36] He therefore proposes an incremental approach focusing upon some animals as the initial subjects of a small set of core legal rights. In particular, he identifies animals that are similar to humans in terms of ‘practical autonomy’ as viable legal subjects for certain basic liberty rights.[37] Wise considers practical autonomy to be the appropriate criteria for the rights of animals on basis that, by virtue of sharing relevant cognitive and emotional characteristics in common with humans, the exercise of those rights would be meaningful and reflect the purposes of the law.[38] Wise believes that ‘great apes, Atlantic bottle-nosed dolphins, African elephants, and African grey parrots’ would satisfy the requirements for legal personhood, and consequently legal rights.[39]

Wise’s approach has moved beyond mere theory within the context of the cases being pursued by his Nonhuman Rights Project (‘NhRP’) in the United States’ courts. The NhRP has filed several habeas corpus claims on behalf of certain chimpanzees and elephants for their release from conditions of captivity.[40] The writ of habeas corpus allows for the release of illegally detained persons.[41] Thus, the NhRP’s task is to convince the courts that the plaintiff animals are legal persons in order to be successful.

By focusing on animals that are cognitively similar to humans, Wise’s approach is arguably more likely to garner public support in comparison to Francione’s broader approach. The animals identified by Wise as ideal candidates for legal personhood are not generally perceived as food or economic interests, particularly in western societies. Attributing rights to these animals would thus have little impact on most human communities. That is not to suggest, however, that the idea would be popular. Public comments made in response to news articles reporting on the NhRP cases are certainly divided on the issue, with many people expressing their opposition to NhRP’s aims.[42] Accordingly, although Wise’s approach might enjoy more popular support in comparison to Francione’s, the goals remain controversial.

In contrast to abolitionists, welfarists focus upon the potential for meaningful improvements in the treatment of animals through the existing legal framework and without any change to their foundational status as property. Robert Garner, one of the most prominent welfarists,[43] does not entirely disagree with the goals of the abolitionist movement but contends that the goals are unachievable in the current political climate.[44] Garner distinguishes between what is moral and what is politically achievable, and suggests that moral arguments alone are not sufficient to end animal use.[45] To demonstrate, Garner notes that the welfare of animals is protected more effectively in Britain than in the United States, notwithstanding that in both jurisdictions, animals constitute property.[46] For Garner, what is distinct in each jurisdiction are the political structures and, importantly, social attitudes that influence political decisions.[47]

According to Garner, the property status of animals is a reflection, rather than the cause, of the low value attached to animals.[48] Garner contends that animals have an interest in not suffering, and their suffering can be eliminated within the animal welfare framework and without abolishing all animal use.[49] Such an approach, according to Garner, would be more politically achievable.[50]

Jonathan Lovvorn, another welfarist, describes efforts to abolish the property status of animals as an ‘intellectual indulgence’.[51] According to Lovvorn, lawyers should not waste their time on ‘impractical theories while billions of animal[s] languish in unimaginable suffering that we have the power to change’.[52] Like Garner, Lovvorn also asserts that reform to the legal status of animals is politically unachievable because society is not ready for the change.[53] To demonstrate, Lovvorn refers to a number of polls suggesting a lack of support for banning the use of animals in medical research, product testing, hunting and clothing.[54] He suggests that ‘the law does not change society, society changes the law’.[55]

While not constituting the core of their arguments, welfarists can sometimes dismiss the prospect of changing the legal status of animals on the basis that community support for such change would be lacking. This observation, among others, is part of what prompted the survey that is the subject of this article. A study of existing literature revealed the need to investigate the extent to which abolitionist goals could be realised, or the extent to which welfarist arguments could be verified within the Australian context.

The value in studying community attitudes towards a particular legal issue lies in the relationship between law and community attitudes. Using a broad interpretation of the term ‘attitudes’, so as to include values and opinions, the connection between law and community attitudes is evident when reviewing legal, political and social studies literature. Laws that reflect community values have been found to be more likely to be accepted and considered substantively legitimate (as distinct from procedurally legitimate).[56] Public opinion polls have also been found to sway legislation and government policies.[57] The role of social values is especially important in a representative democracy like Australia, where laws are expected to reflect popular opinion. As Blumenthal nicely sums up:

if it is in fact the case that laws ... should reflect the attitudes of a populace, or of a majority thereof, then it is essential to measure, and measure accurately, the extent to which they do so. If they do not, whether through change over time, misperceptions on the part of courts or law- and policy-makers, or some other reason, then such laws may lose their moral and legal legitimacy.[58]

The influence of community attitudes on law and legal change can be observed in the evolution of marriage laws in Australia. The most recent development in this space saw the legalisation of same-sex marriage, a change heavily grounded on prevailing community attitudes. The Commonwealth Government held a plebiscite on what was considered a controversial issue in order to determine whether legislation allowing same-sex marriages ought to be introduced into the federal Parliament.[59] After a majority of Australian voters expressed their support for same-sex marriage, legislation reflecting the plebiscite results was passed by the federal Parliament relatively quickly.[60] The amendments to marriage laws were passed even though the plebiscite results were not binding. This is perhaps one of the most obvious examples of the law evolving to reflect community expectations.

Data unveiling community attitudes towards the legal status of animals can thus be important in shaping Animal Law. Such data can provide a fairer indication of whether the conception of animals as property is consistent with what the Australian society thinks, or whether an alternative legal status might better reflect community attitudes. Of course, for what is hardly debated in the public arena, an onerous measure such as a national plebiscite is unlikely to be conducted on the issue of the legal status of animals. It therefore becomes valuable for academics to empirically study community attitudes towards the legal categorisation of animals. Aside from providing data to verify the extent to which the status represents community values, this data can also be useful within academia itself. Within the emerging area of Animal Law, the data can help validate or verify the arguments of abolitionists and welfarists.

Some caveats are necessary here. It would be naïve and misleading to expect or suggest that there is consensus of values within a society, particularly in pluralist value systems.[61] Additionally, the public is not informed on many issues relating to specific laws.[62] The public therefore does not hold an opinion on many issues that affect laws applicable to them.[63] Further, there are other influences that play a much greater role in lawmaking or shaping public policy, such as interest groups and political party lines.[64] For these reasons, it is not being suggested that the legal status of animals should be changed simply to reflect the results of this empirical research. The purpose of such research is merely to add to the existing body of literature that may be considered within the lawmaking process.

There have now been several studies in Australia aimed at identifying prevailing community attitudes with respect to animal welfare.[65] These studies have unveiled a growing concern for animal welfare in Australia. For example, the Animal Tracker Australia survey commissioned by Voiceless Australia found that most Australians believe humans have an obligation not to harm animals.[66] However, the studies to date have all focused on animal welfare or protection standards provided under legislation. They have not focused on the foundational legal status of animals. Thus, they do not provide clarity on the issue of whether that status is consistent with contemporary community values.

There have also been surveys and studies that have measured support for the idea of bestowing animals with legal rights.[67] However, such surveys also provide limited assistance in determining whether Australians support the property categorisation of animals. This is because most of those surveys were conducted in other countries and therefore do not represent Australian values.[68] Further, they do not present the idea of animals being right holders as an alternative to being property. In fact, it is unclear whether the respondents to those surveys were aware of the current legal status of animals. Additionally, such surveys tend to present ‘animal rights’ as the only alternative to the property status of animals. They do not suggest, nor seek opinions on, other alternatives such as implementing a guardianship model,[69] creating a modified property status,[70] or establishing a new and separate legal category for animals that is distinct from property and persons.[71] Thus, while these studies do help us understand whether modern societies agree with the prospect of animals being rights holders, they do not shed light on whether there is any public consensus on whether animals should continue to be classified as property.

It follows that there is a need for research that directly addresses the extent to which the community agrees with this classification, and whether the community would be receptive to alternative classifications. Before that, there is a need to investigate the level of public awareness with respect to the legal status of animals.

In order to find answers to these questions, a survey was developed that invited respondents to anonymously answer two key questions. First, respondents were asked whether they knew that animals are legally classified as property. Second, they were asked if they agreed with the property status of animals. Thus, the survey was designed to ascertain the extent to which respondents were aware of the legal status of animals, and the extent to which they agreed with this status. The former question was important because if people are unaware that animals are legally classified as property, they would not have given much thought to whether they agree with the legal status. It would therefore make it difficult to determine whether the current legal status of animals is consistent with modern community values. It could also potentially explain why the property status of animals has remained largely unchallenged in the public domain, notwithstanding significant debate within the academic community.

The survey also asked a series of questions intended to elicit whether the property classification of animals reflected respondents’ attitudes towards specific classes of animals (pets, farm animals and wild animals). It also sought to identify the factors that influenced respondents’ opinions about animals.

The small-scale and short quantitative survey was intended to provide a snapshot of attitudes associated with the legal status of animals, and to make a modest contribution towards filling the evidentiary gap highlighted above. It therefore had a small sample of 287 respondents from the state of Victoria. Convenient sampling was employed, so there was little control exercised over the composition of the sample.[72] Convenient sampling is a non-probability method of sampling, and is therefore unlikely to be representative of the population (in this case, Victorians over the age of 18).[73] Further, the validity of the inferences drawn from the data obtained from a non-probability sample cannot be assured or tested.[74] In other words, analysis can only be made in respect of the sample surveyed. Thus, as a result of the sample size and sampling method employed, the extent to which the findings of this survey can be generalised is limited.[75] Given the exploratory nature of the research, however, non-probability sampling was considered appropriate for this survey.[76] Exploratory research explores an area that has been subject to little research, and is a first stage of inquiry designed to reveal some basic facts and formulate questions for future, more systematic research.[77] Given that community attitudes towards the legal status of animals have not been explored in Australia, this research can provide helpful guidance in conducting larger-scale empirical research in this area.

In any case, to improve sampling quality, equally sized subsamples were gathered from separate locations.[78] Almost half (49 per cent) of the respondents were chosen from Melbourne, while the remaining respondents (51 per cent) were chosen from regional Victoria. These locations were chosen for data collection in order to detect whether individuals in a regional area, who may have greater exposure to farming practices, hold the same attitudes as those living in a metropolitan area.

To reach a wide demographic, respondents were approached at train, tram and bus stations in Melbourne city, Warragul (in the Gippsland region, south-east of Victoria) and Ballarat (in the west of Victoria). Victorians who do not catch public transport or who do not access these locations were unlikely to have been captured by the survey. Nevertheless, the surveys were distributed during peak as well as off-peak hours so that a broad class of Victorians could be accessed.

The number of male and female respondents was almost evenly split – 49 per cent males and 51 per cent females. This gender divide was quite representative of the Victorian population as, according to the 2016 Census, 49 per cent of the Victorian population were males and 51 per cent females.[79] Forty-four per cent of the respondents were aged between 18–35, while 32 per cent of the respondents were aged between 36–60. Twenty-three per cent of the respondents were over the age of 60.

Passengers waiting for their trains, buses and trams were approached and asked if they wished to participate in a short survey. The survey was kept short to facilitate a high response rate, especially as passengers waiting for their respective modes of public transport had a limited amount of time to spare. Respondents were provided with a two-page self-completion questionnaire after they agreed to participate in the survey. Respondents completed and returned the survey on the spot. An explanatory statement describing the purpose of the survey was provided to the respondents after they completed the survey so that their responses were not affected by the information set out in the explanatory material.

Approval was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee before the survey was conducted.

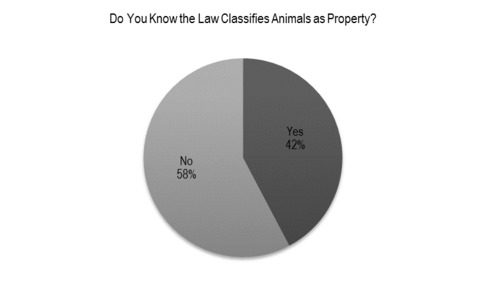

One of the central questions asked in the survey was: ‘Do you know the law classifies animals as property?’ This question was intended to ascertain the extent to which respondents were aware of the legal status of animals. It was answered by 286 respondents. Figure 1 illustrates the responses obtained.

Figure 1: Respondents’ Knowledge of the Current Legal Status of Animals

That most people are unaware of the property status of animals could explain why the legal status of animals has remained unchanged for centuries. If a community is unaware of the legal status of animals, it is unlikely to evaluate the ethical correctness or appropriateness of the status. A community is also unlikely to consider alternative ways of categorising animals in law if they do not know that animals are currently classified as property. This lack of awareness also highlights educational opportunities, which is discussed further in Part IV.

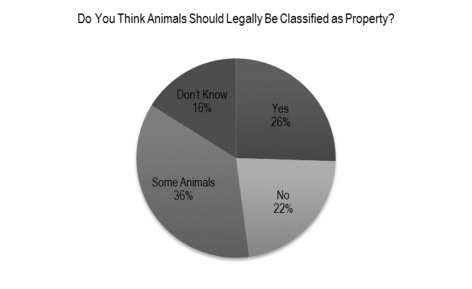

Another key question in the survey was: ‘Do you think animals should legally be classified as property?’ This question was designed to elicit respondents’ immediate and intuitive reaction to the legal status quo, and thus gain some insight into whether this sat comfortably with, or confronted, their value system.

This question was also answered by 286 respondents. The division of responses is set out in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Respondents’ Views on the Legal Status of Animals

Overall, the data collected through this survey suggests that the majority of respondents did not agree with the prevailing status quo of animals as property. Only a quarter of the respondents agreed that animals should be classified as property. Approximately three quarters of the respondents either thought that at least some animals should not be classified as property or were uncertain. These results place a spotlight on the discomfort associated with the property status of at least some animals, indicating that the legal classification may not entirely reflect contemporary attitudes. It justifies the need to rethink the property status of animals, and suggests that efforts exhausted in pushing for abolitionist arguments may not be merely an ‘intellectual indulgence’ after all.[80]

Respondents living in regional Victoria were more likely to agree entirely with the property status of animals, and less likely to entirely disagree with the property status of animals. Twenty-nine per cent of 145 respondents living in regional Victoria indicated that all animals should be property. Only 17 per cent of the regional respondents thought that animals should not be property at all. In contrast, out of the 139 respondents living in Melbourne, only 22 per cent agreed with the property status of all animals while 29 per cent disagreed entirely with the property status of animals. The majority in both groups (59 per cent and 63 per cent respectively), however, believed that only some animals should be classified as property.

Older respondents were more likely to agree with the property status of animals. Out of the 67 respondents aged over 60 who answered this question, 37 per cent indicated that they agreed with the property status of all animals. In contrast, only 22 per cent of the 92 respondents aged between 36–60 agreed with the property status of all animals. Similarly, out of 126 respondents in the 18–35 age group, only 22 per cent agreed with the property status of all animals.

The majority of male and female respondents disagreed with the property status of at least some animals, although male respondents were more likely to do so. Out of the 138 male respondents who answered this question, 63 per cent disagreed with the property status of all or some animals. On the other hand, 54 per cent of the 147 female respondents who answered this question disagreed with the property status or all or some animals.

Overall, responses to this question indicate a lack of appetite among the Victorian public for treating animals as legally akin to other goods. The fact that 58 per cent of the respondents disagreed with the property status of some or all animals adds weight to abolitionist arguments, at least in respect of some animals. Conversely, the results help counter claims that political support for abolishing the property status of animals is lacking. It does so by revealing a minority support for the property status of animals.

These results cannot be generalised for all of Victoria or Australia because of the modest sample size. So this data alone cannot justify a change in the legal status of animals in Australia. Nevertheless, when placed in the context of the wider abolition debate, the results provide a new perspective from which to approach the debate. In doing so, the results make the debate richer with evidence and, consequently, less theoretical.

It is important to point out that the results of the survey do not inform us of the kind of reform that would be politically palatable to Victorians. This is because the survey did not intend to ask respondents whether they agreed with an alternative legal status for animals. Nor did it ask respondents to identify animals that they thought should not be classed as property. The survey also did not ask respondents to share the reasoning behind their responses. Such questions can form part of future empirical studies, which can be informed by existing literature within the abolitionist debate. This is discussed further in Part IV.

The implications of these results must also be interpreted in light of the results noted above in respect of respondents’ awareness of the property status of animals. Public opinion surveys have a limitation in that they often require respondents to provide immediate responses on topics they may not be familiar with.[81] This appears to be the case here given that the majority of respondents were unaware of the property status of animals. Nevertheless, the results do provide insight into respondents’ intuitive attitudes towards the legal classification of animals.

Only one question on the survey was qualitative; respondents were asked to explain: ‘What do you think it means to classify animals as property?’ Around a third of the respondents indicated that they ‘didn’t know’ what it meant to classify animals as property. Approximately 67 per cent (191) expressed their understanding. Three key themes emerged from their responses: responsibility, ownership and legal rights.

Thirty-five per cent (66) of respondents who expressed their understanding of this legal status used the words ‘responsibility’, ‘responsible’, ‘liability’, ‘liable’ or ‘care’. Examples of such responses included:

Domestic animals need to be property so you can be responsible. Different story for wild animals, everyone's responsibility but nobody's property.

It means there is a legal relationship between an animal and a human being which gives the human being control and responsibility over the animal.

That there is someone somewhere who is responsible for the health and wellbeing of said animal, also if the animal causes harm to someone/thing then they are held legally responsible for any damages caused by the animal.

They are yours to take care of and ensure their health and safety.

To care and look after animals humanely.

[L]iable for any damage they cause – ensure safety of animal – ensure animals not neglected etc.

The use of these words indicate that these respondents perceived the property status of animals in the context of an animal owner having legal obligations to care for the animal, and to take legal responsibility for harm caused by animals.

It is also evident from these responses that many respondents thought an owner’s obligations or responsibilities towards an animal are a product of the property status of animals. It is certainly true that owners have responsibilities towards animals they own. However, such responsibilities do not stem from the property status of animals. Rather, they emanate from animal welfare laws, which actually operate as restrictions on property rights. This misconception is understandable, however, given that lay persons cannot be expected to appreciate the nuances of legal concepts such as ‘property’. Nevertheless, such responses do highlight educational opportunities.

Thirty-five per cent (66) of the 191 respondents who shared their understanding of the implications of the property status of animals referred to the words ‘own’, ‘ownership’ or ‘owned’. A few respondents also referred to an owner’s ability to dispose of property. These respondents understood that property is subject to ownership as well as trade, so that animals can be bought and sold.

They can be owned, traded, sold, and belong to owner.

Can be owned. Can sell and dispose anytime.

It means that you own the animal and that animals do not have their own rights.

It means as a vet I am sometimes forced to put down healthy pups as ‘0’ client want anyone else to have it.

If you own a pet it could be stolen and therefore considered property. Other people cannot take or abuse your property, ie, pet.

I think it is a legal definition which assist in the case of laws around owning, harming, trading and containing animals. It makes it easier eg, to legislate laws regarding dangerous dogs – to name only one example.

Despite more than half of the survey respondents being unaware that animals are classified as property, these respondents correctly recognised some of the implications of animals being classified as property. Although being subject to ownership is not the only implication of the property status, it is an important aspect of it. It enables the sale and purchase of animals. There are limitations on how an animal can be ‘disposed’ of, but it is certainly possible for an owner to relinquish their legal title over an animal.[82] With such an understanding, these respondents are in a better, more informed position to form an opinion about whether they agree with the property status of animals.

Eight per cent (15) of the respondents who expressed their understanding of the implications of classifying animals as property made reference to legal rights in their responses. However, only three of these 15 respondents thought that the property classification granted legal rights to animals. Seven respondents understood that animals lacked legal rights because they were classified as property. Five respondents referred to the rights belonging to the owner of an animal. Examples of these responses included:

Assigns rights to and responsibility for the animals affected to specific individuals that are responsible for their care.

There are so many variety of animals it is unrealistic to have a generic classification. I assume “property” assumes no freedom or rights.

I don't really know but it sounds to me that they have no "rights" and people can treat them the way they want (badly) not considering what animal is and what freedom belongs to it.

They have rights to be respected and treated humanely.

To be able to own and treat them in any manner that you deem is your right.

Gives them some rights. Responsible for them legally and ethically.

Thus, with the exception of the three respondents who thought that the property status of animals conferred legal rights to them, these respondents were again correctly able to identify some implications of being classified as property.

Respondents were asked about how they perceived three different categories of animals: pets, farm animals and wild animals. The purpose of these questions was to elicit whether respondents held the same attitude towards different categories of animals and whether any of those categories of animals were viewed as property. They were asked to select a single response from a list of options, one of which was ‘property’. These questions were placed before the key questions discussed above, so that respondents would select an answer without being influenced by questions directly focusing on the property status of animals.

Notably, in the context of this series of questions, the majority of respondents did not perceive animals in any of the three categories as property.

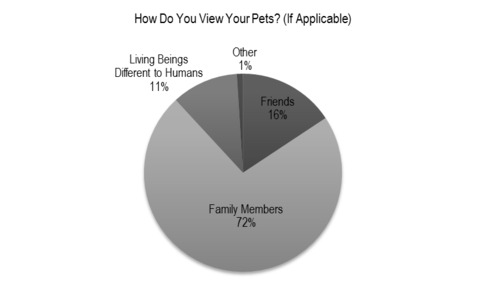

Respondents who owned pets (166) were asked: ‘How do you view your pets?’ These results are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Respondents’ Perspective of Their Pets

These responses suggest that pet animals are commonly regarded as family members rather than as property. This result does not necessarily indicate that animals are viewed as persons. Rather, these results suggest that the respondents’ concept of family extends to animals. ‘Family’ can mean different things to different people. For example, some cultures consider a family unit to comprise of parents and their children, while in other cultures a family unit also includes extended family members.[83] It seems for most pet owners, the concept of family also includes pets.[84]

These results are consistent with other Australian research that has explored the relationship between humans and pet animals. For example, in ‘The Australian Pet Ownership Survey’ conducted in 2013, approximately 90 per cent of the 1 089 pet owners surveyed considered their pets to be a member of their family.[85] An Australian report similarly found that pet owners increasingly consider their pets to be ‘part of the family’.[86]

A more thorough study of the relationship between humans and their pets was undertaken by Franklin in 2006.[87] He found that 88 per cent of the respondents to his study answered ‘yes’ to the question: ‘Do you think of any animals you keep as members of your family?’[88] Franklin then asked respondents about the areas in their house that their pets were allowed to access. He found that more than half of the respondents allowed their pets into their bedrooms, and over a third of the respondents allowed their pets into their children’s bedrooms.[89] Close to 80 per cent of the respondents allowed their pets into the family or lounge room, and almost half the respondents allowed their pets on furniture.[90] Over 60 per cent of the respondents also allowed their pets into meal rooms and the kitchen.[91] Franklin explained the significance of access to household space:

The symbolism of household space needs to be emphasised here. Bedrooms are largely highly private spaces, the inner sanctum of privatised societies. Partners, close friends and siblings and other close family members form the restricted group of intimates using bedrooms together. So in this sense when people in our survey stated that an animal was both a member of the family and allowed into their bedroom, it was a refined answer indicating that they were not just a member of the family but a very close intimate member ... [I]n the past when dogs were kept outside in a separate house, or when they were allowed inside but not on furniture, their separate, inferior status was being marked. To discover that half of those interviewed allowed their animals on furniture is to uncover a major shift in their status and position relative to humans and human society.[92]

While these sentiments towards pet animals are well supported by empirical research, the perception of pet animals as family members does not appear to translate into support for abolishing the property status of animals. Even though none of the pet owner respondents saw their pets as property, pet owners (22 per cent) were almost equally likely as non-pet owners (23 per cent) to say ‘no’ when asked whether animals should be classified as property. Pet owners (36 per cent) and non-pet owners (37 per cent) were also almost equally likely to say that ‘some animals’ should be classified as property. Thus, pet ownership did not make it more likely for respondents to disagree with the property status of animals.

It should also be noted that pet owners undoubtedly benefit from the property status of animals when they no longer wish to keep a pet. While it is not possible to simply abandon an animal, pet owners can surrender their pets to animal shelters. In doing so, they effectively relinquish the legal title to their animal property.[93] White examined the limited data and literature on the surrender of animals to animal shelters, and found mainly ‘owner-centric’ reasons behind the surrender.[94] These included unwanted litter, accommodation problems, owners’ health issues (eg, allergies), incompatibility of the animal with the family, a new child entering the family and lack of time.[95] White explains that his findings are in contrast to the recognition of animals as family members:

These companion animals are legally discarded, with no regulatory sanction falling upon those who relinquish their animals. There is, therefore, a striking tension in the way society regards companion animals. On the one hand, they are affectionately regarded as members of the family. On the other hand, the role of animal shelters shows that they are also regarded as dispensable, being freely discarded in significant numbers each year.[96]

It is thus evident that, although pet owners may perceive their animals as family members, during times of difficulty, inconvenience or change, many may revert to treating their animals as property.

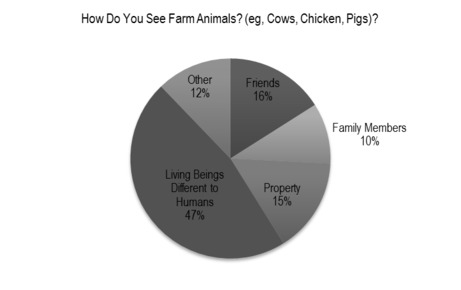

All respondents were then asked: ‘How do you see farm animals (eg cows, chicken, pigs)?’ This question was answered by 287 respondents, and the results are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Respondents’ Perspective of Farm Animals

It had been expected that respondents from regional Victoria would have been more likely to perceive farm animals as property given that animal farming is predominantly carried out in the regional parts of Victoria. It was hypothesised that respondents in these areas would be statistically more likely to live in communities whose economic health depends on animal industries, so they would be more inclined to view farm animals as property. The variation in perspectives was not as significant as expected, however. It was found that 17 per cent of the respondents living in regional Victoria saw farm animals as property, while 14 per cent of the respondents living in Melbourne also saw farm animals as property.

The fact that overall only 15 per cent of respondents saw farm animals as property may again reveal a discomfort in labelling animals as such. The category of family or friends was not largely chosen either, and instead almost half of the respondents selected ‘living beings different to humans’ as their response. It thus appears that farm animals have a special significance in the minds of these respondents, which is perhaps separate from the status of property or persons. One might deduce from these results that, rather than classify farm animals as property or persons, there may be support for the creation of a new and separate legal category for animals.[97]

The tendency to see farm animals as more than property may also align with the demonstrated concern among Australians for the welfare of farm animals. For example, the Animal Tracker Australia study made various findings with respect to community perceptions of the adequacy of animal welfare laws in Australia.[98] It found a high degree of support for improved conditions for farm animals. A majority of the respondents surveyed supported the proposition that farm animals should be given enough space to ‘exhibit their natural behaviours’ and to have access to the outdoors.[99] The study further found that most Australians believe farm animals should be afforded the same level of protection as companion animals.[100] Moreover, the study found that most Australians believe that the wellbeing of animals in the live export trade is important.[101]

Consumer trends also highlight the growing concern for the welfare of farm animals in Australia. For example, according to Woolworths’ ‘2016 Corporate Responsibility Report’, barn laid eggs offered by the supermarket accounted for less than 20 per cent in volume in the egg category, while free range eggs accounted for over 70 per cent.[102] In 2013, Woolworths announced its decision to phase out all caged eggs, based on a ‘sustained decline’ in the sale of such eggs.[103] In the same year, in response to ‘overwhelming feedback’ from customers regarding their confusion on free ranging stocking density requirements, Woolworths decided to label the relevant stocking density on egg packaging.[104] Likewise, in November 2010, Australian Pork Limited[105] (‘APL’) voluntarily committed to phasing out sow stalls by 2017.[106] APL explained it was being informed by major Australian retailers, which were ‘clearly indicating there is a growing unrest amongst customers about the industry’s use of gestation stalls’.[107] All these factors, which highlight community concerns for the welfare of farm animals, complement the finding of the present survey, that most respondents do not see farm animals as mere property.

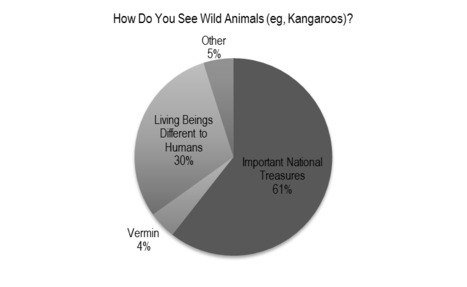

Respondents were asked: ‘How do you see wild animals (eg, kangaroos)?’ The results from the 287 respondents who answered this question are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Respondents’ Perspective of Wild Animals

While answering this question, many respondents expressed difficulty in choosing between ‘important national treasures’ and ‘vermin’. This is because the category of wild animals encompasses many varied species of animals; koalas may be seen as important national treasures, while foxes may be seen as pests. Additionally, some species of wild animals can be regarded as both. For example, kangaroos – an animal that appears on Australia’s national emblem – may be seen as important national treasures. In farming areas, however, kangaroos may be regarded as pests.[108] It became apparent based on such feedback that the category of ‘wild animals’ is too wide to make generalisations about. Accordingly, in determining whether animals should be property, it may be necessary to consider different species individually.

Irrespective of the difficulties in choosing between the two options, it is notable that none of the respondents saw wild animals as property. This may be because animals living in the wild are perceived to be ‘free’ and their behaviours are normally beyond the control of humans. Wild animals are also not generally in the possession of any person. Whatever may be the reason, respondents did not perceive wild animals as property. So far as wild animals are not property, particularly those that are not in the possession or control of humans, these results suggest that the law does align with community attitudes. This cannot be said in respect of wild animals that are subject to qualified property, or within the control and possession of humans. In the latter scenario, the results suggest the opposite.

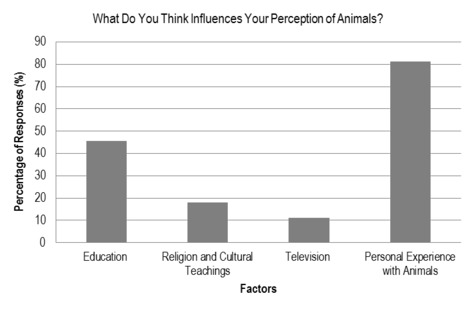

Respondents were asked: ‘What do you think influences your perception of animals?’ There were 277 responses to this question. They were allowed to choose more than one option as their response here as it is possible for a person to be influenced on an issue by several factors. These results are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Influences over Respondents’ Perception of Animals

Respondents’ personal experience with animals was by far the most influential factor in shaping their perceptions about animals. This may explain why they perceived different categories of animals differently. They were more likely to perceive their pets, which provide companionship and would probably share intimate space in their homes, as family members or friends. Other categories of animals, which generally do not share similarly close bonds with humans, were not predominantly viewed as such.

The second most influential factor was education. The fact that most respondents were unaware of the property status of animals can be explained by the fact that they have not been educated about this. Lack of education on issues relating to the property status of animals might also explain why most respondents did not perceive any of the categories of animals as property. Indeed, children are not taught about the legal status of animals in schools. Until the recent introduction of Animal Law units in Australian universities, even students enrolled in tertiary education were unlikely to have learnt about the legal status of animals.[109]

The fact that only 18 per cent of the respondents attributed their perceptions to religious influences is also noteworthy, given that the current legal status of animals as property is, to a certain extent, an inheritance of Judeo-Christian theology. William Blackstone, for instance, explained that:

In the beginning of the world, we are informed by holy writ, the all-bountiful creator gave to man “dominion over all the earth; and over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.” This is the only true and solid foundation of man’s dominion over external things, whatever airy metaphysical notions may have been started by fanciful writers upon this subject. The earth, therefore, and all things therein, are the general property of all mankind, exclusive of other beings, from the immediate gift of the creator.[110]

Seventeenth century philosopher John Locke shared similar views. He contended that the earth, the fruits it bore and the beasts that roamed on it were all God’s gift to men. He explained: ‘yet being given for the use of Men, there must of necessity be a means to appropriate them some way or other before they can be of any use, or at all beneficial to any particular Man’.[111]

However, since Blackstone and Locke justified the property classification of animals, science has shed more light on the relationship between humans and animals. Charles Darwin is credited for displacing the assumption that humans are a unique type of evolutionary being. Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is considered to be authority for the modern understanding that humans have evolved from animals, and that the difference between human and non-human animals is a matter of degree rather than kind.[112] This theory is now a part of the national curriculum for Year 10 students in Australia, so young people in contemporary Australia are learning about the nature of this evolutionary link between humans and non-human animals.[113]

With education being a greater influence than religion in shaping respondents’ perceptions of animals today, less people’s views may be aligned with Blackstone’s and Locke’s positions with respect to animals. This may again explain why many respondents disagreed with the property status of some or all animals.

This empirical study reports that most people are unaware of the property classification of animals under Australian law. This knowledge gap potentially explains why the legal status of animals has remained static. One cannot be expected to challenge the status if they are unaware of its existence. Given that education plays an important role in influencing perspectives about animals, however, this stagnancy can potentially be unclogged.

Educational opportunities have been highlighted by these results. Public awareness campaigns may have value in making the Australian community aware of the property status of animals and the issues surrounding the status. Educational campaigns could cover the history and reasons behind the property classification of animals, the implications of being property, and alternative ways of legally classifying animals. Embedding such knowledge within the school education system is also likely to be valuable given that education was reported to be influential in shaping attitudes towards animals. Such knowledge would place the Australian community in a more informed position to decide whether or not they agree with the property status of animals. This would have the effect of bringing the abolition debate from the legal and academic space into the public arena. It would ultimately help policymakers in measuring and understanding community attitudes towards the legal status of animals.

This survey has also shown that there may now be many Australians who do not agree with the property classification of animals. If that is indeed the case, the case for abolishing the property status of animals is strengthened. If the legal status of animals is no longer consistent with contemporary attitudes, it is also essential to know what the alternatives may be and whether the alternative statuses would better align with community attitudes. For this reason, the abolition and welfare debate should be kept alive. Reasons for and against maintaining the property status of animals need to be thoroughly examined, and all possible alternatives need to be explored. The implications of abolishing the property status of animals and adopting alternative statuses also need to be investigated. Such scholarly efforts can then inform the content of educational campaigns, school curriculums and eventually lawmakers.

It is also important to replicate this study in other Australian states and territories to determine whether the views of the Victorian population are shared widely in the country. Further, as awareness and debate about the property status of animals increases, it will be imperative to continue monitoring community support for either maintaining the property status of animals or changing the status. Such surveys should therefore continue to be conducted in the future, ideally on a larger scale. Such surveys can also elicit views on alternative legal statuses for animals, providing greater insight into whether the current legal status of animals is the most reflective of contemporary attitudes. Further, if different animals are to be categorised differently, the more comprehensive surveys should seek to identify the classes of animals that should not be property in the community’s view. Again, such evidence would further enrich the existing body of literature on the abolition debate with empirical data, and also help policymakers in taking a stand when the debate reaches and intensifies in the public forum.

The debate between abolitionists and welfarists does prompt one to wonder whether the Australian society would want to see the legal status of animals change. This empirical study has been the first attempt in Australia to measure community attitudes towards the property status of animals. The results of this survey contribute to the debate, currently confined in philosophical and legal circles, by providing insight into the public domain. Accepting the connection between law and community attitudes, this research offers a new angle to the abolition debate and enriches it with additional evidentiary support.

Before the community can form and express their opinions on the property status of animals, however, they need to actually be aware of this status and all of its implications – symbolic, ethical and practical. This study has revealed that most people may not be aware that animals are legally classified as property. It has highlighted the need for greater community education about the legal status of animals.

Based on this initial empirical research, there does appear to be support for changing the legal status of at least some animals. That is not surprising given that, as this study confirmed, different kinds of animals are perceived differently. Further research is now needed to determine which animals are, according to public opinion, worthy of an elevated legal status and what that alternative status might be. Not only will such research bring the theoretical debate to people’s dining tables, it will ultimately give direction to Australian lawmakers.

[*] PhD candidate at Monash University. The author is grateful to the four peer reviewers for their valuable feedback on this article. The author is also thankful to Professor Paula Gerber and Dr Joanna Kyriakakis for their guidance in conducting this research.

[1] Roy Disney, quoted in Elizabeth A Minton and Lynn R Kahle, ‘Religion and Consumer Behaviour’ in Catherine V Jansson-Boyd and Magdalena J Zawisza (eds), Routledge International Handbook of Consumer Psychology (Routledge, 2017) 292, 292.

[2] See Joe Ludwig, ‘Minister Suspends Live Cattle Trade to Indonesia’ (Media Release, DAFF11/174L, 8 June 2011).

[3] Greyhound Racing Prohibition Bill 2016 (NSW).

[4] A Bloody Business (Directed by Dave Everett, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2011); Making a Killing (Directed by Dave Everett, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2015).

[5] See Brian’s Story – Indonesian Live Export Investigation (Animals Australia); Katrina J Craig, ‘Beefing Up the Standard: The Ramifications of Australia’s Regulation of Live Export and Suggestions for Reform’ [2013] MqLawJl 5; (2013) 11 Macquarie Law Journal 51, 56 <https://www.mq.edu.au/about/about-the-university/faculties-and-departments/faculty-of-arts/departments-and-centres/macquarie-law-school/macquarie-law-journal>.

[6] Animals Australia, ‘RSPCA, Animals Australia, GetUp! Websites Crash under Huge Demand in Live Export Campaign’ (Media Release, 31 May 2011).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Joe Ludwig, ‘Government Lifts Live Cattle Export Suspension’ (Media Release, DAFF/192L, 6 July 2011).

[9] New South Wales, Special Commission of Inquiry into the Greyhound Racing Industry in New South Wales, Report (2016) vol 1, 18 [1.113].

[10] Ibid 17 [1.107].

[11] Ibid 18 [1.113].

[12] Mike Baird, ‘Greyhound Racing Given One Final Chance under Toughest Regulations in the Country’ (Media Release, 11 October 2016).

[13] Productivity Commission, ‘Regulation of Australian Agriculture’ (Inquiry Report No 79, Australian Government, 15 November 2016) 11.

[14] These are animals that are farmed for food, such as cows, chickens and pigs.

[15] Alain Pottage, ‘Introduction: The Fabrication of Persons and Things’ in Alain Pottage and Martha Mundy (eds), Law, Anthropology and the Constitution of the Social: Making Persons and Things (Cambridge University Press, 2004) 1, 4; Deborah Cao, Katrina Sharman and Steven White, Animal Law in Australia (Thomson Reuters, 2nd ed, 2015) 66, 70.

[16] Cao, Sharman and White, above n 15, 70.

[17] Ibid 71.

[18] Yanner v Eaton [1999] HCA 53; (1999) 201 CLR 351, 368 [24] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ).

[19] Ibid 368 [24]–[25] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ).

[20] Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) s 73(7).

[21] See, eg, Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1979 (NSW) s 4; Animal Welfare Act 1999 (NT) s 4.

[22] Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (Jonathan Cape, 1976).

[23] See Tom Regan, The Case for Animal Rights (University of California Press, 1983) 347–9; Gary L Francione, Animals, Property and the Law (Temple University Press, 1995); Steven Wise, Rattling the Cage: Towards Legal Rights for Animals (Perseus Publishing, 2000).

[24] See Robert Garner, ‘Political Ideology and the Legal Status of Animals’ (2002) 8 Animal Law 77; Jonathan R Lovvorn, ‘Animal Law in Action: The Law, Public Perception, and the Limits of Animal Rights Theory as a Basis for Legal Reform’ (2006) 12 Animal Law 133.

[25] Gary L Francione, Animals as Persons: Essays on the Abolition of Animal Exploitation (Columbia University Press, 2008); Gary L Francione, ‘Animals – Property or Persons?’ (Faculty Paper No 21, Rutgers Law School, 2004); Gary L Francione, Rain without Thunder: The Ideology of the Animal Rights Movement (Temple University Press, 1996); Francione, Animals, Property, and the Law, above n 23.

[26] Francione, ‘Animals – Property or Persons?’, above n 25, 42.

[27] Ibid 14.

[28] Ibid 40.

[29] Ibid 14–21.

[30] Ibid 15, 43.

[31] Francione, Animals, Property, and the Law, above n 23, 107.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Francione, Rain without Thunder, above n 25, 146; Francione, Animals, Property, and the Law, above n 23, 258.

[34] Francione, Rain without Thunder, above n 25, 146.

[35] Francione, Animals, Property, and the Law, above n 23, 261.

[36] Steven M Wise, ‘Animal Rights, One Step at a Time’ in Cass R Sunstein and Martha C Nussbaum (eds), Animal Rights: Current Debates and New Directions (Oxford University Press, 2004) 19, 19.

[37] Ibid 32.

[38] Ibid 40.

[39] Ibid 41.

[40] See Nonhuman Rights Project, Litigation: Confronting the Core Issue of Nonhuman Animals’ Legal Thinghood (2018) <https://www.nonhumanrights.org/litigation/>.

[41] See David Clark and Gerard McCoy, Habeas Corpus (Federation Press, 2000).

[42] See, eg, the public comments published in response to Alan Yuhas, ‘Chimpanzees Are Not People, New York Court Decides’, The Guardian (online), 5 December 2014 <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/04/court-denies-legal-personhood-of-chimpanzees>; Karin Brulliard, ‘Chimpanzees Are Animals. But Are They “Persons”?’, The Washington Post (online), 16 March 2017 <https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/animalia/wp/2017/03/16/chimpanzees-are-animals-but-are-they-persons/?utm_term=.f0329a3abe8a>.

[43] Francione describes Garner as a ‘new-welfarist’, but Garner prefers to use the terminology ‘protectionist’: Robert Garner, ‘A Defense of a Broad Animal Protectionism’ in Gary L Francione and Robert Garner (eds), The Animal Rights Debate: Abolition or Regulation? (Columbia University Press, 2010) 103, 104.

[44] Ibid 168; Robert Garner, ‘Animals, Politics and Democracy’ in Robert Garner and Siobhan O’Sullivan (eds), The Political Turn in Animal Ethics (Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016) 103, 104.

[45] Garner, ‘A Defense of a Broad Animal Protectionism’, above n 43, 105.

[46] Ibid 131; ‘Garner, ‘Political Ideology and the Legal Status of Animals’, above n 24, 85.

[47] Garner, ‘Political Ideology and the Legal Status of Animals’, above n 24, 85.

[48] Garner, ‘A Defense of a Broad Animal Protectionism’, above n 43, 131.

[49] Ibid 128; Garner, ‘Political Ideology and the Legal Status of Animals’, above n 24, 81–6.

[50] Garner, ‘A Defense of a Broad Animal Protectionism’, above n 43, 168–9.

[51] Lovvorn, above n 24, 139.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid 136–7.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid 149.

[56] Tom R Tyler and John M Darley, ‘Building a Law-Abiding Society: Taking Public Views about Morality and the Legitimacy of Legal Authorities into Account when Formulating Substantive Law’ (2000) 28 Hofstra Law Review 707; Mike Vuolo, ‘Incorporating Consensus and Conflict into the Legitimacy of Law’ (2014) 62 Crime, Law & Social Change 155.

[57] Edith J Barrett, ‘The Role of Public Opinion in Public Administration’ (1995) 537 Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 150; H Whitt Kilburn, ‘Personal Values and Public Opinion’ (2009) 90 Social Science Quarterly 868; Edward Alsworth Ross, ‘Social Control II: Law and Public Opinion’ (1896) 1 American Journal of Sociology 753; Richard A Pride, ‘Public Opinion and the End of Busing: (Mis)Perceptions of Policy Failure’ (2000) 41 Sociological Quarterly 207; Jeff Manza and Clem Brooks, ‘How Sociology Lost Public Opinion: A Genealogy of a Missing Concept in the Study of the Political’ (2012) 30 Sociological Theory 89.

[58] Jeremy A Blumenthal, ‘Who Decides? Privileging Public Sentiment about Justice and the Substantive Law’ (2003) 72 University of Missouri-Kansas City Law Review 1, 2 (emphasis in original).

[59] See Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1800.0 – Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey, 2017 (15 November 2017) <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1800.0> .

[60] Marriage Amendment (Definition and Religious Freedoms) Act 2017 (Cth).

[61] Lawrence R Jacobs, ‘The Contested Politics of Public Value’ (2014) 74 Public Administration Review 480, 482; Thomas E Nelson, ‘Policy Goals, Public Rhetoric, and Political Attitudes’ (2004) 66 Journal of Politics 581, 581.

[62] Blumenthal, above n 58, 13.

[63] Paul Burstein, ‘Why Estimates of the Impact of Public Opinion on Public Policy Are Too High: Empirical and Theoretical Implications’ (2006) 84 Social Forces 2273, 2285.

[64] Sanel Susak, ‘How Does Public Opinion Influence the Law?’ (2013) 22 Nottingham Law Journal 167, 167; Jacobs, above n 61, 482.

[65] See, eg, Peter John Chen, Animal Welfare in Australia: Politics and Policy (Sydney University Press, 2016); Humane Research Council, ‘Animal Tracker Australia: Baseline Survey Results’ (Report, Voiceless, June 2014); Grahame Coleman, ‘Public Perceptions of Animal Pain and Animal Welfare’ (Paper presented at the Australian Animal Welfare Strategy Science Summit on Pain and Pain Management, May 2007); Grahame Coleman, ‘Tools to Assess Community Attitudes and Consumer Responses to Animal Welfare’ (Final Report APL Project 2009/2264, Department of Agriculture, June 2009); Ihab Erian and Clive J C Phillips, ‘Public Understanding and Attitudes towards Meat Chicken Production and Relations to Consumption’ (2017) 7(3) Animals <https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/7/3>; Tania D Signal and Nicola Taylor, ‘Attitudes to Animals: Demographics within a Community Sample’ (2006) 14 Society & Animals 147.

[66] Humane Research Council, above n 65, 6.

[67] Rebecca Riffkin, In US, More Say Animals Should Have Same Rights as People (18 May 2015) Gallup <http://www.gallup.com/poll/183275/say-animals-rights-people.aspx> Peter Moore, Majority Endorse Animal Rights (29 April 2015) YouGov <https://today.yougov.com/topics/lifestyle/articles-reports/2015/04/29/majority-endorse-animal-rights>; Colin Jerolmack, ‘Tracing the Profile of Animal Rights Supporters: A Preliminary Investigation’ (2003) 11 Society & Animals 245; Adrian Franklin, Bruce Tranter and Robert White, ‘Explaining Support for Animal Rights: A Comparison of Two Recent Approaches to Humans, Nonhuman Animals, and Postmodernity’ (2001) 9 Society & Animals 127; C J C Phillips et al, ‘Students’ Attitudes to Animal Welfare and Rights in Europe and Asia’ (2012) 21 Animal Welfare 87; Michael Vigorito, ‘An Animal Rights Attitude Survey of Undergraduate Psychology Students’ (1996) 79 Psychological Reports 131.

[68] Riffkin, above n 67; Moore, above n 67; Jerolmack, above n 67; Phillips et al, above n 67; Vigorito, above n 67.

[69] See David Favre, ‘Equitable Self-Ownership for Animals’ (2000) 50 Duke Law Journal 473.

[70] See David Favre, ‘Living Property: A New Status for Animals within the Legal System’ (2010) 93 Marquette Law Review 1021 (where Favre suggests a ‘living property’ model); Susan J Hankin, ‘Not a Living Room Sofa: Changing the Legal Status of Companion Animals’ (2007) 4 Rutgers Journal of Law & Public Policy 314 (where Hankin suggests a separate category of property for companion animals).

[71] For a discussion on some European countries that may have created a separate legal category for animals, see Geeta Shyam, ‘The Legal Status of Animals: The World Rethinks Its Position’ (2015) 40 Alternative Law Journal 266.

[72] Martin Brett Davies, Doing a Successful Research Project: Using Qualitative or Quantitative Methods (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007) 56.

[73] Anthony M Graziano and Michael L Raulin, Research Methods: A Process of Inquiry (Pearson, 6th ed, 2007) 325; Sotirios Sarantakos, Social Research (Macmillan Publishers, 2nd ed, 1998) 141.

[74] Martin Frankel, ‘Sampling Theory’ in Peter V Marsden and James D Wright (eds), Handbook of Survey Research (Emerald Group Publishing, 2nd ed, 2010) 83, 83.

[75] Alan Bryman, Social Research Methods (Oxford University Press, 3rd ed, 2008) 183.

[76] Sarantakos, above n 73, 151.

[77] W Lawrence Neuman, Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (Pearson, 7th ed, 2011) 38.

[78] Davies, above n 72, 55.

[79] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016 Census QuickStats (23 October 2017) <http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/2?opendocument> .

[80] As claimed by Lovvorn. See Lovvorn, above n 24, 139.

[81] David A Rochefort and Carol A Boyer, ‘Use of Public Opinion Data in Public Administration: Health Care Polls’ (1988) 48 Public Administration Review 649, 656; Burstein, above n 63, 2285.

[82] For example, by surrendering their animal to an animal shelter. However, abandoning of animals may be prohibited by law: see, eg, Animal Care and Protection Act 2001 (Qld) s 19.

[83] Mary Patricia Treuthart, ‘Adopting a More Realistic Definition of “Family”’ (1990) 26 Gonzaga Law Review 91, 96–7.

[84] See also Susan Phillips Cohen, ‘Can Pets Function as Family Members?’ (2002) 24 Western Journal of Nursing Research 621, 621.

[85] Animal Health Alliance, ‘Pet Ownership in Australia’ (Report, 2013) 27.

[86] Australian Companion Animal Council, ‘Contribution of the Pet Care Industry to the Australian Economy’ (Report, 7th ed, Animal Health Alliance, 2010) 42.

[87] Adrian Franklin, Animal Nation: The True Story of Animals and Australia (University of New South Wales Press, 2006).

[88] Ibid 208–11.

[89] Ibid 210–11.

[90] Ibid.

[91] Ibid.

[92] Ibid 211–12 (emphasis in original).

[93] Steve White, ‘Companion Animals: Members of the Family or Legally Discarded Objects?’ [2009] UNSWLawJl 42; (2009) 32 University of New South Wales Law Journal 852, 853.

[94] Ibid 868.

[95] Ibid.

[96] Ibid 869.

[97] The creation of a new legal category, called non-personal subjects of law, has been proposed in Tomasz Pietrzykowski, ‘The Idea of Non-personal Subjects of Law’ in Visa A J Kurki and Tomasz Pietrzykowski (eds), Legal Personhood: Animals, Artificial Intelligence and the Unborn (Springer, 2017) 49.

[98] Humane Research Council, above n 65.

[99] Ibid 10.

[100] Ibid 3.

[101] Ibid 2.

[102] Woolworths Group, ‘2016 Corporate Responsibility Report’ (2016) 21.

[103] Woolworths Limited, ‘Corporate Responsibility Report 2013’ (2013) 22.

[104] Ibid.

[105] APL is an industry body representing pork producers in Australia.

[106] APL, ‘World First for Australian Pork Producers’ (Media Release, 17 November 2010).

[107] Ibid.

[108] See also Dale G Nimmo, Kelly K Miller and Robyn Adams, ‘Managing Feral Horses in Victoria: A Study of Community Attitudes and Perceptions’ (2007) 8 Ecological Management & Restoration 237. The authors of this article note that public opinion concerning the management of feral horses is divided because there are differences in how feral horses are perceived. Some consider feral horses to be introduced pests, while some see them as icons of national identity: at 238.

[109] Even today, Animal Law is offered, as an elective unit, in only 15 universities. It is also offered as an elective unit in some schools of animal and veterinary sciences. Overall, the education reaches a very small section of the Australian population: Voiceless, Study Animal Law (2018) Animal Law Education <https://www.voiceless.org.au/animal-law/study-animal-law>; Alexandra L Whittaker, ‘Animal Law Teaching in Non-law Disciplines: Incorporation in Animal and Veterinary Science Curricula’ (2013) 9 Australian Animal Protection Law Journal 113, 114.

[110] William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (Clarendon Press, 3rd ed, 1768) vol 2, 2–3.

[111] Peter Laslett (ed), John Locke: Two Treatises of Government (Cambridge University Press, 1988) 286–7.

[112] Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man (Princeton University Press, first published 1871, 1981 ed) 208–34.

[113] Australian Curriculum, Biology <https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/senior-secondary-curriculum/science/biology/?unit=Unit+3>.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2018/47.html