University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

THE IMPORTANCE OF LAWYERS IN INTERNATIONAL TAX POLICY DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT: AN EXPLORATION AND EXTENSION OF THE LEGAL-ECONOMIC LITERATURE

ANN KAYIS-KUMAR[*]

The advent of the global digital economy has increased opportunities for aggressive tax planning by multinational enterprises (‘MNEs’). Governments are increasingly faced with the competing objectives of remaining internationally competitive and encouraging foreign investment while also protecting their national tax bases.

Two key trends have had a significant impact on the international tax debate. First, over the past three decades, the rise of MNEs and the prominence – and dominance – of inter-company trade as a proportion of global trade has fundamentally shifted the influence of individual governments’ tax policies. Second, even though corporate tax policy has traditionally been a field dominated by economists, there is now a shift towards ‘politicisation’ of the debate.

The focus of this article is on the importance of legal practitioners and scholars in assisting with meaningful reform at the intersection of these two trends – and examining alternative theoretical approaches to tax policy. In doing so, this article also bridges two disciplines by combining legal analysis with linear optimisation modelling (to simulate a tax-minimising MNE’s behavioural responses to both existing and proposed tax legislation).

Ultimately, it is hoped that this research will present a platform for further discussion on the tax treatment of cross-border intercompany transactions, and facilitate the development of improvements to both the tax law design and drafting.

I INTRODUCTION

Two key trends have had a significant impact on the international tax debate. First, over the past three decades, the rise of multinational enterprises (‘MNEs’) and the prominence – and dominance – of inter-company trade as a proportion of global trade has fundamentally shifted the influence of individual governments’ tax policies. Second, even though corporate tax policy has traditionally been a domain dominated by economists, the past two decades have seen a shift towards ‘politicisation’ of the debate.[1]

The focus of this article is on the importance of legal scholars and practitioners in assisting with meaningful reform at the intersection of these two trends; namely, tax policy issues arising from the cross-border transactions of multinationals. At present, cross-border inter-company transactions account for the majority of global trade in terms of value, yet these transactions remain largely beyond public scrutiny and empirical investigation.[2] Further, it is difficult to gather details (either by way of empirical evidence or anecdotal evidence) on the specific cross-border inter-company financing structures utilised by MNEs given ‘the private nature of their professionals who uphold strict codes of confidentiality’.[3]

This brings to the fore the importance of the contribution that can be made by legal practitioners and scholars. Their insights are both unique and useful, as their commentary can provide input on existing reforms and examine alternative theoretical approaches to tax policy. In this setting, legal academics such as Stewart observe that since ‘passive and active investment (and skilled labour) is increasingly mobile across borders, the “fiscal bargain” is fundamentally changed’.[4]

This brings a meaningful perspective to challenges presented by the design and structure of the existing international tax framework. In blending the two disciplines of law and economics, this article adopts an alternative legal-economic approach to tax law design and policy. This is a novel approach to conceptualising the core issues associated with the cross-border tax treatment of inter-company transactions.

The remainder of this article: first, outlines the theoretical framework in Part II; second, highlights legal design issues in the current regulatory approach in Part III; third, considers an alternative reform traditionally confined to the economic literature in Part IV; and fourth, combines legal analysis and mathematical modelling to present an alternative legal-economic approach to examining cross-border tax reforms in Part V.

II THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEUTRALITY IN TAX POLICY

This Part presents the theoretical framework for the current tax treatment of MNEs’ cross-border inter-company funding flows by: first, examining the concept of income; second, exploring the principle of tax neutrality; and third, blending these two concepts in a legal-economic approach which posits that economically equivalent inter-company flows ought to be taxed alike.

First, the literature contains competing concepts of income. These can be grouped by field – accounting,[5] economics,[6] law – and even within one particular field the definition may be unsettled.

The judicial concept of ‘the income’ has traditionally focussed on the distinction between income as a ‘flow’ and gain as ‘profit’. The seminal work in this context is Fisher’s The Nature of Capital and Income, which defines income as a ‘flow of services through a period of time’ and capital as ‘quantity of wealth ... existing at a particular instant of time’.[7]

In the tax law context, the concept of income was largely imported from trust law, such that income is ‘a “flow” from capital assets’.[8] Specifically, Woellner et al delineate the relevant flows from capital as ‘interest from debts, rents from the lease of property, royalties from the licensing of intellectual property rights, and dividends from shares’.[9] For completeness, commentators such as Prebble have questioned this characterisation and described it as one of ‘several fundamental problems with the judicial concept of income’.[10]

Second, while the term ‘tax neutrality’ can be used to refer to quite different concepts,[11] in this article it is used to refer to the principle that tax provisions – and, more generally, tax systems – ought to minimise distortions to economic decision-making and therefore have relatively little impact on the overall allocation of economic resources.[12] As observed by Musgrave and Musgrave, taxes should be designed to ‘minimize interference with economic decisions in otherwise efficient markets’.[13] As such, tax policy based on the principle of tax neutrality aims to minimise distortions and therefore minimise welfare loss.[14]

Third, the concept of ‘funding neutrality’ is currently debt/equity focussed and as such underestimates the significance of the ‘invisibility’ and ‘fungibility’ of inter-company flows. This is typified by the following observation by Bärsch:

In the case of financial instruments, the most important neutrality consideration concerns the decision on different modes of finance (financial neutrality). Business may finance investments traditionally via retained earnings, new equity issues or debt capital. In the most general form, tax neutrality would require taxation of all finance investments in the same way, with neither preference nor prejudice.[15]

However, there is a growing body of literature examining the fungibility between debt and equity financing in the context of MNEs, led by legal practitioners and legal academics such as Burnett,[16] Graetz,[17] and Benshalom,[18] among others.[19]

Further, this broadened conceptualisation is supported by tax practitioners’ publicly available recommendations outlining various techniques for the tax-effective repatriation of funds from overseas operations. Specifically, some legal practitioners group under the one umbrella of ‘Alternatives for Getting Funds Out’ the following options: dividends; redemptions of shares; interest payments/royalties/payments for services.[20]

This broader conceptualisation of looking beyond the debt bias is consistent with the reform proposal by legal academic Avi-Yonah, who in collaboration with tax law partner Halabi, suggests that thin capitalisation rules be extended ‘to other deductible payments like royalties’.[21] Legal academic Benshalom also provides an analysis of the fungibility of these activities, observing that ‘almost every type of tax reduction plan that uses affiliated financial transactions could be executed via other types of affiliated transactions’.[22] Similarly, given the increased capital mobility, allocating ownership within an MNE is also a precarious exercise.[23]

In contrast, the economic literature has not adequately considered the fungibility of funding flows beyond debt and equity financing, including licensing and leasing activities in the context of cross-border inter-company transactions. This is an understudied issue that has recently been highlighted in the context of thin capitalisation rules by legal practitioners and legal academics Frost, Paynter, Vann and Cooper.[24] This regime is the focus of the following Part.

III THE CURRENT REGULATORY APPROACH: THIN CAPITALISATION RULES

Thin capitalisation regimes have been subject to much criticism in both economics and law, with each field containing unique and insightful critiques. When critiques from these two fields are taken together, it is possible to make the observation that even though thin capitalisation rules appear to mitigate the debt bias, mitigating the debt bias ought not to be conflated with eliminating the debt bias – let alone attaining tax neutrality.

This article focuses on highlighting the legal design weaknesses identified by legal practitioners and scholars, which are currently understudied in the literature which has a predominantly economic focus. The three key legal design weaknesses inherent in the existing legislative design of thin capitalisation rules are: first, their development is ad hoc and they are not well targeted; second, these rules give rise to tax arbitrage opportunities; and third, the framework for these rules is exceedingly complicated. This is followed by an exploration of the case for adopting a broader institutional approach.

Since thin capitalisation rules are ad hoc and not well targeted, they are often bypassed by MNEs who instead utilise ‘hybrid instruments and international differences in definitions of debt and equity’.[25] A significant contribution to the debate are the unique observations by legal practitioners and legal academics in this regard. The remainder of this section highlights two key categories of observations: first, the disconnect in the characterisation of these legislative rules; and second, the challenges arising from definitional issues.

First, legal practitioner Burnett and legal academic Brown are two of few commentators who critique the ‘anti-abuse’ characterisation of thin capitalisation rules, observing that these rules are better described as structural changes aimed at mitigating the ‘excess’ deductibility of interest expenses.[26]

In relation to definitional issues, legal practitioners and legal academics in the Australian context highlight, for example, that most finance leases are currently not subject to Australia’s thin capitalisation regime due to the definition of ‘financing arrangement’ in section 974-130 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) (‘ITAA97’).[27] Further, legal academic Vann observes that new foreign direct investment (‘FDI’) in Australia is often financed at or around the legal limits and that internal debt is often not recorded in FDI statistics, suggesting that ‘what is currently regarded as portfolio debt in Australia is probably disguised FDI’.[28]

Australia’s debt-equity rules were implemented to complement the introduction of the existing thin capitalisation regime. The policy objective of these rules was to ensure a substance over form approach was adopted in the classification of these rules.[29] However, the emerging issue in recent years has been the use of hybrid financial instruments which often take advantage of the international differences in definitions of debt and equity. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (‘OECD’) makes a distinction between combating base erosion and profit shifting (‘BEPS’) by limiting interest deductibility and reducing distortions between the tax treatment of debt and equity.[30] However, it is the decision of the lawmakers to create a tax-induced debt bias which actually results in the tax base erosion, which thin capitalisation rules attempt to restrict.

Given recommendations by the OECD’s BEPS Project on Action 2,[31] policymakers are increasingly implementing specific anti-avoidance rules targeting these hybrid mismatches. In Australia, this has taken the form of the Exposure Draft of the Treasury Laws Amendment (OECD Hybrid Mismatch Rules) Bill 2017 (Cth). If implemented, this anti-avoidance provision will aim to ‘neutralise’ the tax advantage gained from arrangements giving rise to double non-taxation or double deductions by including an amount in assessable income or disallowing a deduction, respectively.

On the other hand, tax barrister Burnett notes that at the inter-company level, debt and third-party debt are substitutable.[32] Such economically equivalent funding options should have the same tax treatment to ensure tax neutrality in the context of funding arrangements. This would eliminate the need for increasingly complex rules supplemented with largely reactive anti-avoidance provisions.

C Exceedingly Complicated Framework

There is also a strong consensus that the existing thin capitalisation framework is highly technical and complicated.[33] There is a wider international tax framework including, but not limited to: complex debt and equity rules; dividend imputation and corporate shareholder taxation issues;[34] withholding taxes;[35] other jurisdictions’ interest limitation rules; bilateral tax treaties; interactions with the various versions and updates to the OECD Model Tax Convention, including articles 9(1) and 24(4); OECD Guidelines; and other OECD materials.

For instance, Australia’s existing thin capitalisation regime contained in Division 820 of the ITAA97 currently spans over 150 pages of legislation, with highly technical rules requiring complicated calculations. This calls into question whether these rules (and other associated rules) achieve simplicity and transparency. It is also arguable that the existing legal design of these rules conflicts with the effectiveness and fairness principles.[36]

Another design complexity emerges from the OECD’s BEPS Project recommendation to shift from safe harbour limits to arm’s length rules. This is exacerbated by using an arm’s length price in the cross-border inter-company context, with legal practitioners noting ‘the difficulty in using inherently indefinite concepts like an “arm’s length price”’.[37] Further, in relation to arm’s length rules, legal academics including Avi-Yonah and legal practitioners such as Taylor highlight the complexity of the current system in both design and administration.[38]

D The Importance of a Broader Institutional Approach

The above legal design weaknesses are particularly problematic given the rise of MNEs, and their ability to engage in sophisticated cross-border tax planning techniques have governments and policymakers struggling to deal with the implications. This highlights the importance of legal academics’ and practitioners’ involvement in the design, implementation and maintenance of these reforms.

There is a widespread perception that tax revenue base erosion problems can be countered by, inter alia, tightening existing anti-avoidance rules or fine-tuning these rules by implementing piecemeal amendments as issues arise.[39] However, the economic realities of the current structure of international trade and commerce have shifted dramatically compared to the time at the inception of these rules. Further, since legislation is limited by the words used, it is inevitably susceptible to uncertainty as the global economic landscape shifts.

For example, the plethora of amendments to Australia’s current thin capitalisation regime have not alleviated this uncertainty. Nearly half of all amendments to Australia’s thin capitalisation regime merely corrected omissions (denoted as ‘Omission’ in the below Table 1), while a quarter of amendments clarified or aligned the operation of the rules with the intention of the originating legislation (denoted as ‘Aligning’). On the other hand, only a quarter of amendments extended or developed the thin capitalisation regime (denoted as ‘Extended’, and in bold). This is itemised in Table 1 below.

Table 1 – Overview of Amendments to Australia’s Current Thin Capitalisation Regime

|

Year

|

Number

|

Description

|

|

2001

|

162

|

Originating

|

|

2002

|

53

|

Aligning

|

|

2002

|

117

|

Aligning

|

|

2003

|

16

|

Omission

|

|

2003

|

142

|

Aligning

|

|

2005

|

21

|

Omission

|

|

2005

|

41

|

Omission

|

|

2005

|

64

|

Extended

|

|

2006

|

58

|

Omission

|

|

2006

|

101

|

Omission

|

|

2007

|

143

|

Omission

|

|

2007

|

164

|

Omission

|

|

2008

|

97

|

Omission

|

|

2008

|

145

|

Extended

|

|

2009

|

15

|

Extended

|

|

2010

|

90

|

Extended

|

|

2012

|

115

|

Aligning

|

|

2013

|

88

|

Omission

|

|

2013

|

101

|

Aligning

|

|

2014

|

110

|

Extended

|

Accordingly, the following two-pronged approach may overcome the challenges faced by policymakers reforming cross-border tax rules: first, evolving the function of administrative agencies and law reform bodies; and second, heightening the capacity of courts and tribunals. Each will be dealt with in turn.

First, despite the introduction of Draft Tax Determination TD 2007/D20[40] (which was subsequently replaced by TR 2009/D6[41] and finalised by TR 2010/7[42]) this was only binding on the Australian Taxation Office (‘ATO’). As such, uncertainty and complexity in this area remained, and most recently culminated in the Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v Federal Commission of Taxation (No 4) case.[43] Evolving the function of administrative agencies and law reform bodies by entrusting them with preparing and updating regulations would likely result in reduced complexity and uncertainty. This is also compatible with the existing framework for thin capitalisation rules, which currently has scope for regulatory updates.[44] So, the legislature could enact high-level rules, thereby retaining control over the ultimate operation of those rules, yet leave the operational details to another level of government. Increasing the responsibilities of a central policy agency – particularly one equipped with technical experts – would likely lead to a more responsive approach. The legislature could thereby reduce the impact of issues arising from the rapidly evolving international tax landscape by enacting ‘intransitive’ laws setting out relatively high-level goals and avoiding micromanagement.[45] This approach is neither radical nor unheard of,[46] and is consistent with principles-based reform proposals contained in the literature. Notably, as observed by legal scholar and judge Avery Jones:

The real choice, I believe, is not between detailed rules that we have today and less detailed legislation, when detailed legislation wins on the ground of certainty; but between detailed rules and less detailed legislation interpreted in accordance with principles, where less detailed legislation wins on the ground of certainty because the use of principles provides predictability.[47]

The second aspect of this broader institutional approach is to heighten the capacity of courts and tribunals. This could be achieved by embedding the underlying concepts upon which a tax law is based, in order to facilitate a more purposive approach to interpretation being adopted by the judiciary. Support for this approach has been expressed by the judiciary, including the Hon Graham Hill, who suggests the inclusion of a clear and detailed statement of the design details underpinning the legislation.[48] This would have the additional benefit of crystallising the underlying concepts and principles in order to facilitate the court’s application of the rules to new circumstances – which may currently be unanticipated and ‘unanticipatable’. This further strengthens the justification for adopting a principles-based reform proposal, as outlined above.

Similarly to the usefulness of adopting a principles-based approach to tax law design, it is also important to consider economic first principles to address any shortcomings in existing policy design. Doing so is useful for both transparency and good tax design. This is the starting point of the allowance for corporate equity (‘ACE’) literature, which makes it instructive to explore the ACE in practice.

This Part focuses on the Belgian and Italian ACE-variants. While there is much practitioner commentary on and economic analysis of the Belgian and Italian ACE-variants, these critiques occur largely in isolation. Further, a longitudinal, legal analysis of ACE-variants in practice has not yet been conducted in the English-language literature.[49] As such, this Part compares the Belgian and the Italian ACE-variants with a focus on the scope and impact of the commentary of the legal profession. Most notably, the English-language literature on both these ACE-variants lacks analysis from legal academics. Rather, the academic literature is limited to economists. Nonetheless, legal practitioners have been documented as playing an active role in the analysis of these reforms.

The Belgian Notional Interest Deduction (‘Belgian NID’)[50] was introduced in 2005 (effective from the 2007 tax year) to encourage equity financing following two key pressures. First, pressures from the European Commission to abandon the Belgian coordination centre regime;[51] and second, competition following the expansion of the European Union to countries with lower corporate tax rates, such as Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania and Hungary, which emphasised the need for Belgium to strengthen its position on the international tax map.

When the originating legislation was introduced the Belgian NID was very close to the pure version of the ACE.[52] This was apparent in the parliamentary focus, which appeared to be on the tax neutral characteristic of the Belgian NID with its potential to overcome the debt bias.[53] This is evinced by the originating explanatory notes,[54] which detail the political, philosophical, economic and tax policy rationales for implementing the Belgium ACE-variant, and the anticipated impact of this reform.

However, legal commentators have suggested that an alternative purpose was the underlying motivation for the implementation of the Belgian NID. Specifically, legal practitioners such as Themelin have noted that:

the introduction of the notional interest deduction had precisely the stated objective of making Belgium fiscally attractive to foreign investors and to establish a credible and competitive alternative for the coordination centers whose regime has been condemned by the European authorities.[55]

Indeed, the Belgian NID resulted in substantial investment by both local and overseas MNEs.

However, maintaining this reform has been challenging; the Belgian NID has subsequently been modified, phased down and, most recently, Parliament is considering the abolition of the Belgian NID. Legal practitioners have stressed that abolishing the Belgian NID will likely erode business confidence and diminish the attractiveness of Belgium as a destination for inbound investment:

It is therefore true that the deduction of notional interest has allowed many companies to reduce their taxable profits, but this is only the objective pursued, in full knowledge of the facts, by the political parties which are origin of the mechanism and some of which do not hesitate to criticize it sharply today ... This constant legal uncertainty leads some companies to choose more peaceful skies, sometimes by settling only a few kilometers from our borders, to the detriment of Belgium’s competitiveness, the economy and image at the international level. This is naturally regrettable.[56]

Italy provides a useful case study because it has implemented two ACE-variants under two different corporate-shareholder tax systems. This article focuses on the ACE-variant currently in place; introduced in 2011 (effective from 2012) and entitled the Aiuto alla crescita economica [Aid to economic growth] (‘Italian ACE’),[57] this was one of a plethora of reforms implemented under the emergency Salva Italia [Save Italy] decree.

Arguably sharing the main characteristics of the theoretical ACE,[58] the Italian ACE was implemented in conjunction with the local business tax, the IRAP (imposta regionale sulle attività produttive [regional tax on productive activity]), which is conceptually similar to the Comprehensive Business Income Tax (‘CBIT’).[59] This was in addition to a limit on the deductibility of interest, in force since 2008.

Its potential to overcome the debt bias was among the three-fold rationale provided in the originating legislation for the implementation of the Italian ACE, which aimed to:[60]

• stimulate the capitalisation of companies by reducing tax on income from capital funding risk;

• reduce the imbalance in the tax treatment between companies that are financed with debt and companies that are financed with equity, thereby strengthening the capital structure of Italian companies; and

• to encourage, more generally, the growth of the Italian economy.[61]

This is also expressed in the explanatory memorandum, which clearly states that the introduction of the Italian ACE:

aims to restore balance within the taxation of business income; equalising the tax burden on the different sources of financing through a reduction in the tax on equity financing, taking into account the need to strengthen the capital structure of companies and of the Italian economy in general.[62]

While the Italian ACE is still in a relatively early stage, it appears to have the support of practitioners,[63] industry,[64] government bodies[65] and regional institutions,[66] who have praised the reform as a comprehensive package consistent with preventing MNEs from undercapitalising their Italian operations.

Nonetheless, the originating legislation for the Italian ACE has not been immune to design concerns. Specifically, industry commentators have noted at least two key issues in practice.

First, definitional uncertainties arising from accounting standards have impacted the calculation of the Italian ACE base. For example, the lack of unanimity in the accounting treatment of some instruments (on whether certain instruments should be classified as liabilities or equity) resulted in their exclusion from the ACE base.[67] However, as noted by legal scholars such as Freedman, streamlining the tax law with accounting principles generally would likely give rise to tax sovereignty issues.[68]

Second, the evolution of the accounting framework has also resulted in definitional complexities which had not been problematic under the previous Italian Dual Income Tax. For example, the Italian ACE treatment of ‘reserves’ is most likely attributable to the more complex accounting standards.[69]

Even though it is still a relatively new reform, the Italian ACE experience provides a significant contrast to the Belgian NID. This is exemplified in the response of the European Commission, which observed that the Italian ACE was implemented ‘to help overcome firms’ debt bias in external funding and as such strengthen corporate balance sheets’,[70] and noted with approval the super-ACE mechanism ‘[requiring] prior authorisation on the basis of article 108 [of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union] to ensure the compatibility of state aid and the functioning of the internal market’.[71] This pragmatic approach to implementing the super-ACE effectively bypassed the problems faced in the Belgian context.

Ultimately, by cross-referencing the economic literature on the Belgian and Italian ACE-variants with legal practitioners’ commentary through a longitudinal analysis, it is possible to make two new observations about the implementation and maintenance of these regimes.

First, in the context of designing an ACE reform that will satisfy the legislative objectives, both the Belgian and Italian ACE-variant experiences suggest that there is a significant element of ‘loss aversion’ when implementing and maintaining fundamental reforms such as the ACE.[72] The key ‘lesson learnt’ should be to introduce a relatively modest ACE and gradually strengthen the ambit of this reform with a targeted approach over time.

Second, in relation to the more specific funding neutrality aspects of these ACE-variants and their suitability in the cross-border anti-avoidance context, a broader question emerges: namely, whether the implementation of an ACE would make cross-border anti-avoidance rules such as thin capitalisation rules redundant. This question remains under-explored in the literature.[73]

Mathematical optimisation is one of the most powerful and widely-used quantitative techniques for making optimal decisions. In the context of this article, the process of ‘making optimal decisions’ is expressed as MNEs’ decisions to minimise taxation for the overall group by utilising various conduit financing structures.

The Multinational Tax Planning (‘MTP’) model developed by the author presents an alternative legal-economic approach to taxing multinationals.[74] The MTP blends the top-down approach of an economist (viewing the plethora of rules as an optimisation problem focussed on an efficiency-based solution) with the bottom-up approach of a lawyer (with a detail-oriented framework of individual tax rules as they would apply to an individual multinational). This presents a novel, interdisciplinary approach to conceptual and regulatory design.

Specifically, the MTP model formulates as an algorithmic expression a hypothetical MNE’s decision to engage in tax minimising behaviour at the cross-border inter-company level, whereby the objective function is the minimisation of total tax payable (‘TTP’). Developed by using the IBM® ILOG® CPLEX® for Microsoft® Excel (‘CPLEX’) software,[75] Microsoft Excel is utilised to generate the data, delineate the parameters, and output the solution in a multidimensional format, while the CPLEX software is used to express and solve the optimisation problem. Specifically, the general optimisation problem is the minimisation of the objective function by adjusting the design variables and at the same time satisfying the constraints (namely, various types of inter-company transactions available to the MNE).

Applying the principle of tax neutrality (that, ceteris paribus, all like income should be treated alike for tax purposes) to various types of inter-company transactions results in equalising the tax treatment between otherwise fungible interest, leasing rents, certain types of royalties and dividends.[76] This is illustrated in Table 2 below.

Table 2 – Summary of Tax Treatment under ‘Funding Neutrality’

|

|

Scope of the rule

|

Distortions to funding neutrality

|

Impact on behavioural responses

|

|||

|

Interest

|

Dividends

|

Royalties

|

Rents on leasing

|

|||

|

Theory: Tax neutrality

|

✓

rD=r%

|

✓

rE=r%

|

✓

rC=r%

|

✓

rS=r%

|

Eliminates

|

Eliminates

|

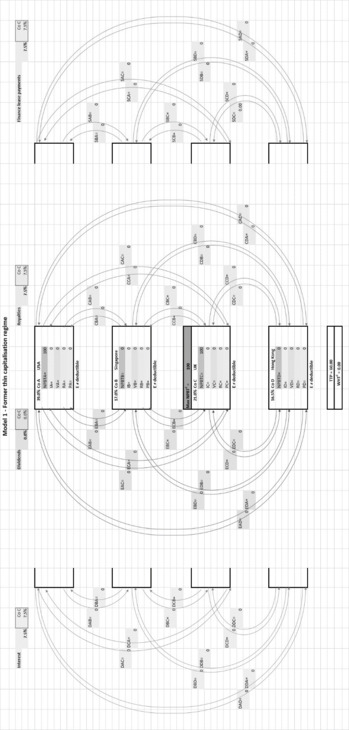

The hypothetical MNE has entities in four jurisdictions: the United States, the United Kingdom, Hong Kong and Singapore. By focussing on funding constraints and regulatory limitations directly relevant to inter-company funding decisions, the model is flexible in relation to representing both funding structure decisions and the regulations influencing those decisions. The various inter-company funding decisions, in terms of funding type and location, amount to any combination of 48 various types and directions of funding flows across the four jurisdictions and four fungible funding types. This is illustrated in the below Figure 1.

NPBT = net profit before tax

TTP = total tax payable

Figure 1 – Simulating Inter-Company Funding Decisions

A Changes to the Corporate Income Tax Rate: The UK, Italy and Australia

In an increasingly globalising and internationally competitive business environment, governments are under considerable pressure to lower their headline corporate income tax (‘CIT’) rates. Jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom (‘UK’), the United States, Belgium, Italy and Australia are no exception with much political pressure resulting in reductions to their CIT rates to: 17 per cent,[77] 21 per cent,[78] 20 per cent,[79] 24 per cent[80] and 25 per cent,[81] respectively.

Generally, the argument is that a home jurisdiction will be able to collect more tax revenue by being more internationally competitive. It is of course conceded that the economic rent portion of funds will escape tax. The MTP model’s ability to isolate and observe the behaviour of pure profits facilitates an objective assessment of whether, ceteris paribus, a reduced CIT rate in the UK, Italy or Australia can benefit these jurisdictions. Results are expressed in terms of both the TTP and the average effective tax rate (‘AETR’).

For completeness, it is necessary to acknowledge that modelling generally involves a trade-off between realism in scope and simplicity to facilitate meaningful analysis. So, the results extracted below may not necessarily reflect the only behavioural responses suited to each variation. Rather, these figures simply reflect optimised TTP results which are based on simplified assumptions to present an abstraction of reality. This does not make the observations any less meaningful, since the purpose of model building is to learn about relations between variables.

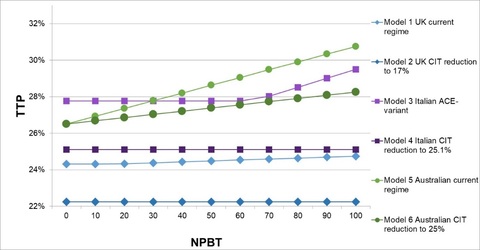

The results of modelling a headline CIT rate cut in the UK, Italy and Australia are outlined in the below Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3 – Results of Modelling a Headline CIT Rate Cut on the UK, Italian and Australian Subsidiaries

|

NPBT

|

Model 1 UK current regime

|

Model 2 UK CIT reduction to 17%

|

Model 3 Italian ACE-variant

|

Model 4 Italian CIT reduction to 25.1%

|

Model 5 Australian current regime

|

Model 6 Australian CIT reduction to 25%

|

|

0

|

24.32%

|

22.25%

|

27.76%

|

25.10%

|

26.50%

|

26.50%

|

|

10

|

24.32%

|

22.25%

|

27.76%

|

25.10%

|

26.93%

|

26.68%

|

|

20

|

24.33%

|

22.25%

|

27.76%

|

25.10%

|

27.35%

|

26.85%

|

|

30

|

24.38%

|

22.25%

|

27.76%

|

25.10%

|

27.78%

|

27.03%

|

|

40

|

24.43%

|

22.25%

|

27.76%

|

25.10%

|

28.20%

|

27.20%

|

|

50

|

24.48%

|

22.25%

|

27.76%

|

25.10%

|

28.63%

|

27.38%

|

|

60

|

24.54%

|

22.25%

|

27.76%

|

25.10%

|

29.05%

|

27.55%

|

|

70

|

24.59%

|

22.25%

|

28.03%

|

25.10%

|

29.48%

|

27.73%

|

|

80

|

24.64%

|

22.25%

|

28.52%

|

25.10%

|

29.90%

|

27.90%

|

|

90

|

24.69%

|

22.25%

|

29.01%

|

25.10%

|

30.33%

|

28.08%

|

|

100

|

24.74%

|

22.25%

|

29.50%

|

25.10%

|

30.75%

|

28.25%

|

Figure 2 – Results of Modelling a Headline CIT Rate Cut on the UK, Italian and Australian Subsidiaries

Turning first to the UK’s CIT rate cut proposed by the UK’s Autumn Statement 2016, this will see a reduction from 20 per cent to 17 per cent.[82] The MTP modelling shows that, ceteris paribus, a reduction in the CIT rate in the UK from the existing 20 per cent to an eventual 17 per cent would not only ‘ease the vulnerability of the UK to profit shifting’.[83] This is despite a lower CIT rate of 16.5 per cent available in Hong Kong being included as part of the MTP model. Indeed, a CIT rate cut to 17 per cent would make the UK the destination for profit shifting activities, with the maximum level of funds available (at 200) being diverted to the UK, whereas all other jurisdictions would receive no funds from profit shifting arrangements.

However, it is important to not conflate the UK being the top destination for profit shifting activities and it being the top beneficiary of this reform. Also, if other jurisdictions were to follow the UK’s lead by also reducing their headline CIT rates then invariably these results would not hold. Further, a sensitivity analysis using the MTP model shows that the MNE is indifferent in its behavioural response to any CIT rate reductions below 18.9 per cent. In other words, any reductions in the CIT rate below 18.9 per cent will simply forfeit tax revenue from economic rents without impacting profit shifting behaviours. This suggests that instead of a CIT rate cut to 17 per cent, the UK would be better off if it were to reduce its CIT rate to 18.9 per cent, as it would still remain the destination for profit-shifting activities while also better protecting its tax revenue base.

In relation to the Italian regime, the MTP modelling indicates that the tax revenue base is protected by the existence of the Italian fixed ratio rule – regardless of the existence of the ACE-variant. If Italy were to implement CIT rate cuts, the TTP would remain at 55.51 (an AETR of 27.8 per cent) for all increments of tax-aggressiveness until a reduction in the Italian CIT rate to 25.1 per cent. From that point onwards, there is no longer an additional incentive for profit shifting behaviour and TTP falls to a flat 50.20 (an AETR of 25.1 per cent) for all levels of tax-aggression, as shown in the above Table 3 and Figure 2.

The results from modelling both the UK and Italian CIT rate cuts puts into context an observation by Mansori and Weichenrieder that ‘[t]he (implicit) assumption of the public choice literature is that fiscal externalities between regions are positive: higher taxation of region A increases tax revenues of region B’.[84] While their model found that fiscal externalities are negative, the findings of the MTP model suggests that fiscal externalities are capped.

The proposal to cut Australia’s CIT rate to 25 per cent confirms this finding. For the most tax-aggressive MNEs (namely, those who book NPBT between 0–20), TTP remains at 53 until a fall in the Australian CIT rate to 21.5 per cent. This means that global TTP is effectively capped at 53. In other words, if Australia were to proceed with a reduction in the CIT rate from 30 per cent to 25 per cent, pure profits will not shift and economic rents will simply be forfeited. Specifically, where this variation is modelled with NPBT increments between 0–100, the AETR ranges between 26.50 per cent–8.25 per cent thereby simply enabling relatively less tax-aggressive MNEs to further reduce their TTP.

Accordingly, the MTP model shows that an MNE is indifferent to slightly higher rates of tax than those proposed in the UK, Italy and Australia. Even though this model does not consider economic rents, the concern of fiscal externalities ought not to apply since, given their immobility, they do not impact tax revenues of other jurisdictions. Further, assuming that immobile economic rents will also be taxed at a reduced rate, the findings of this article suggest that a reduction in the CIT rate to the proposed rates will result in at best, no difference in the tax benefit; at worst, a reduced tax benefit to the home jurisdiction. It should be noted that this article does not attempt to model investment behaviour over time in response to global tax changes.

B ACE-Variants in Practice: Belgian NID and Italian ACE

This section explores the effectiveness of the Belgian NID and the Italian ACE regimes by reference to the MTP model. This presents a higher-level conceptual analysis of whether an ACE in practice, implemented rigorously and consistently with its conceptual roots, presents an effective approach to achieving cross-border funding neutrality. As such, in order to model the hypothetical tax-minimising MNE’s behavioural responses to the implementation of both the Belgian and Italian ACE-variants the home jurisdiction becomes: first, Belgium and second, Italy.

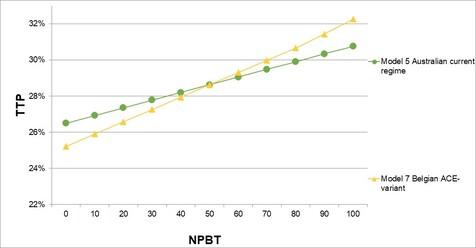

The expectation in the literature and the observations of practitioners are that the Belgian ACE-variant results in a reduction in TTP compared to a regime without it, such as the current tax system modelled with the Australian regime (‘Model 5’). The MTP model confirms this observation in the case of the more tax-aggressive MNEs (where NPBT ranges between 0–40). However, the Belgian ACE-variant is equivalent in terms of TTP collected when NPBT is 50, and it is able to collect more tax revenue from the relatively less tax-aggressive MNEs (where NPBT ranges between 60–100) compared to the Australian regime. In other words, even though the lower bound of the AETR falls from 26.50 per cent to 25.22 per cent, the upper bound increases from 30.75 per cent to 32.25 per cent.

This result is shown in the below Table 4 and Figure 3.

Table 4 – Comparison between Australia’s Current System and Belgium’s ACE-Variant

|

NPBT

|

Model 5 Australian current regime

|

Model 7

Belgian ACE-variant

|

|

0

|

26.50%

|

25.22%

|

|

10

|

26.93%

|

25.90%

|

|

20

|

27.35%

|

26.58%

|

|

30

|

27.78%

|

27.26%

|

|

40

|

28.20%

|

27.94%

|

|

50

|

28.63%

|

28.62%

|

|

60

|

29.05%

|

29.30%

|

|

70

|

29.48%

|

29.98%

|

|

80

|

29.90%

|

30.66%

|

|

90

|

30.33%

|

31.43%

|

|

100

|

30.75%

|

32.25%

|

Figure 3 – Comparison between Australia’s Current System and Belgium’s ACE-Variant

Once amendments are incorporated into the Belgian ACE-variant model to reflect the past decade of reform, a slight reduction in the TTP is observed, as shown in the below Table 5.

Table 5 – Results of Modelling the Belgian ACE-Variant over Time

|

NPBT

|

Model 8

Belgian ACE-variant at 2006

|

Model 7

Belgian ACE-variant

|

Withholding tax collected at 2006

|

Withholding tax currently collected

|

|

0

|

25.25%

|

25.22%

|

2.50

|

2.43

|

|

10

|

25.95%

|

25.90%

|

2.25

|

2.14

|

|

20

|

26.65%

|

26.58%

|

2.00

|

1.85

|

|

30

|

27.35%

|

27.26%

|

1.75

|

1.56

|

|

40

|

28.05%

|

27.94%

|

1.50

|

1.27

|

|

50

|

28.75%

|

28.62%

|

1.25

|

0.98

|

|

60

|

29.45%

|

29.30%

|

1.00

|

0.69

|

|

70

|

30.15%

|

29.98%

|

0.75

|

0.40

|

|

80

|

30.85%

|

30.66%

|

0.50

|

0.11

|

|

90

|

31.55%

|

31.43%

|

0.25

|

0.00

|

|

100

|

32.25%

|

32.25%

|

0.00

|

0.00

|

However, this reduction in TTP is exactly commensurate with the reduction in withholding tax rates, rather than being a result of the lower ACE rate. This behaviour can be expressed algorithmically as follows:

ACEBelgium(2016) = ACEBelgium(2006) – ∆WHT{Belgium(2016)– Belgium(2016)}

The remainder of this section explores behavioural responses if the home jurisdiction were Italy. Italy’s system is preferable to Australia’s current system in relation to protecting the tax revenue base from the most tax-aggressive MNEs (that is, where NPBT ranges between 0–20).

Under the Italian tax system, the lower bound of the AETR increases from 26.50 per cent to a flat 27.78 per cent for the majority of increments of MNE tax aggressiveness. However, in what appears to be a reverse of the tax implications of the Belgian NID, the upper bound under the Italian ACE decreases from 30.75 per cent to 29.50 per cent.

This result is illustrated in the below Table 6 whereby Model 35 simulates the Italian regime upon extracting the Italian ACE-variant.

Table 6 – Results of Modelling the Italian ACE-Variant over Time

|

NPBT

|

Model 9

Italian ACE-variant at 2011

|

Model 3 Italian ACE-variant

|

Model 10

Italy’s current regime ex-ACE-variant

|

|

0

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

|

10

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

|

20

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

|

30

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

|

40

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

|

50

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

|

60

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

27.76%

|

|

70

|

28.03%

|

28.03%

|

28.03%

|

|

80

|

28.52%

|

28.52%

|

28.52%

|

|

90

|

29.01%

|

29.01%

|

29.01%

|

|

100

|

29.50%

|

29.50%

|

29.50%

|

For completeness, as indicated in the above Table 6, the MNE has no behavioural response to the changes in the ACE rate. This suggests that any increase in the ACE rate would benefit the ability of the Italian reform to increase tax on economic rents without distorting MNE behaviour. Further, rather than this result being entirely attributable to the impact of the Italian ACE-variant, this result is due to Italy’s use of an ‘interest cap rule’ instead of fixed debt-to-equity ratios. It is noteworthy that Italy’s ‘interest cap rule’ is a fixed net interest to earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (‘EBITDA’) ratio, similar in operation to the OECD’s Recommendation on BEPS Action 4 (‘OECD’s Recommendation’).[85]

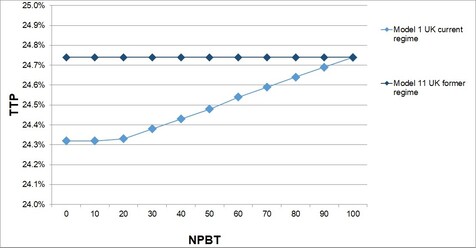

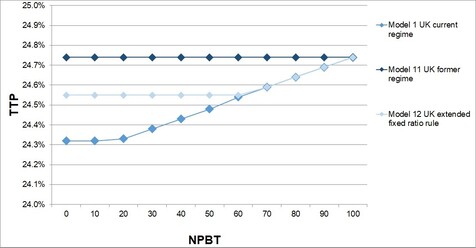

Repealed as at April 2017, the Worldwide Debt Cap (‘WWDC’) regime was replaced with a fixed ratio rule consistent with the OECD’s Recommendation.[86] Following public consultation,[87] the Her Majesty’s Treasury released its full response in December 2016, which included draft legislation restricting corporate interest tax deductibility.[88] This was updated in January 2017,[89] with legislation taking effect from 1 April 2017. This section presents a comparative analysis of these two regimes.

Following adoption of the current regime, there is a slight decline in TTP. While this presents a nominal decrease (with an overall decline in AETR ranging between 0.42 per cent to zero per cent for the most- to least-tax aggressive MNEs, respectively) the most problematic observation arising from this modelling is that a WWDC regime with a CIT rate of 20 per cent disincentives profit shifting, thereby protecting the UK’s tax revenue base more effectively than the fixed ratio rule, which is more vulnerable to profit shifting. It is noteworthy that the fixed ratio rule is however better at protecting the tax revenue base than a standard thin capitalisation rule.[90] Further, it encourages the use of the UK as a profit shifting destination for the most tax-aggressive MNEs (that is, where NPBT ranges between 0–10). This result is shown in the below Table 7 and Figure 4.

Table 7 – Comparison between the UK’s Current Fixed Ratio Rule and the Former WWDC Regime

|

NPBT

|

Model 1

UK current regime

|

Model 11

UK former regime

|

|

0

|

24.32%

|

24.74%

|

|

10

|

24.32%

|

24.74%

|

|

20

|

24.33%

|

24.74%

|

|

30

|

24.38%

|

24.74%

|

|

40

|

24.43%

|

24.74%

|

|

50

|

24.48%

|

24.74%

|

|

60

|

24.54%

|

24.74%

|

|

70

|

24.59%

|

24.74%

|

|

80

|

24.64%

|

24.74%

|

|

90

|

24.69%

|

24.74%

|

|

100

|

24.74%

|

24.74%

|

Figure 4 – Comparison between the UK’s Current Fixed Ratio Rule and the Former WWDC Regime

Broadening the scope of the thin capitalisation rules to include ‘interest and payments [which are] economically equivalent to interest’ was a key feature of the OECD’s Recommendation.[91] It is important to note that, while this presents a promising step towards a more expansive conceptualisation of inter-company funding activities than typically contemplated under thin capitalisation rules, this delineation still sits within the current paradigm of adopting a ‘debt/equity all-or-nothing’ approach.[92] For example, the OECD’s Recommendation carves out dividends from the scope of other ‘economically equivalent’ amounts with statements such as ‘payments which are not economically equivalent to interest. This could include ... dividend income’.[93] In doing so, the OECD’s Recommendation bypasses substantial economic literature suggesting that inter-company debt and equity funding are fungible, as outlined in the above Part II. Accordingly, the remainder of this Part considers the implications of applying the principle of tax neutrality to a reform proposal developed in this article; namely, an extended fixed ratio rule.

1 Reform Proposal: An Extended Fixed Ratio Rule

This reform proposal broadens the definition of ‘interest’ to also include the returns from other types of financing within the operation of a fixed ratio rule. The MTP model shows that such an extended fixed ratio rule is either equivalent to, or more effective, from a TTP perspective than utilising the existing fixed ratio rule as adopted by the UK.

This result is shown in the below Table 8 and Figure 5.

Table 8 – Comparison between the UK’s Current Fixed Ratio Rule and an Extended Fixed Ratio Rule

|

Model 1

UK current regime

|

Model 12

UK extended fixed ratio rule

|

|

|

0

|

24.32%

|

24.55%

|

|

10

|

24.32%

|

24.55%

|

|

20

|

24.33%

|

24.55%

|

|

30

|

24.38%

|

24.55%

|

|

40

|

24.43%

|

24.55%

|

|

50

|

24.48%

|

24.55%

|

|

60

|

24.54%

|

24.55%

|

|

70

|

24.59%

|

24.59%

|

|

80

|

24.64%

|

24.64%

|

|

90

|

24.69%

|

24.69%

|

|

100

|

24.74%

|

24.74%

|

Figure 5 – Comparison between the UK’s Current Fixed Ratio Rule, the Former WWDC Regime and an Extended Fixed Ratio Rule

By adopting such an extended fixed ratio rule, the UK becomes the destination for profit shifting for the majority of MNEs; attracting both highly- and moderately-tax aggressive MNEs (that is, where NPBT ranges between 0–60). This means that the UK is able to collect a greater proportion of tax revenue at each of these increments of MNE tax-aggressiveness than under the current regime. This is a finding with significant implications for governments and policymakers.

D Australia’s Response to the OECD BEPS Recommendation on Action 4: Tightening Thin Capitalisation Rules

Both tax and legal scholars such as Vann,[94] and Ruf and Schindler[95] are increasingly challenging the traditional conception in the literature that thin capitalisation rules protect the tax revenue base. Similarly, the MTP model developed by the author contributes to this emerging literature. Specifically, previous research by the author found that the hypothetical MNE is indifferent to the existence of, and variations in, thin capitalisation rules.[96] For completeness, these results are extracted in Table 9 below.

Table 9 – Results of Modelling Thin Capitalisation Rules with Various Safe Harbour Rules

|

NPBT

|

Model 13

Australia current regime

|

Model 14

Australia loosened thin cap rules

|

Model 15

Australia tightened thin cap rules

|

|

0

|

26.50%

|

26.50%

|

26.50%

|

|

10

|

26.93%

|

26.93%

|

26.93%

|

|

20

|

27.35%

|

27.35%

|

27.35%

|

|

30

|

27.78%

|

27.78%

|

27.78%

|

|

40

|

28.20%

|

28.20%

|

28.20%

|

|

50

|

28.63%

|

28.63%

|

28.63%

|

|

60

|

29.05%

|

29.05%

|

29.05%

|

|

70

|

29.48%

|

29.48%

|

29.48%

|

|

80

|

29.90%

|

29.90%

|

29.90%

|

|

90

|

30.33%

|

30.33%

|

30.33%

|

|

100

|

30.75%

|

30.75%

|

30.75%

|

This result is at odds with the Explanatory Memorandum to the Tax and Superannuation Laws Amendment (2014 Measures No 4) Act 2014 (Cth), which states that ‘the thin capitalisation rules will be tightened to prevent erosion of the Australian tax base’.[97] However, as shown above, tightening thin capitalisation rules from a debt-to-equity ratio of 3:1 to 1.5:1 (Model 14 and Model 13, respectively), does not attain this legislative intention. Rather the MNE, which has other types of inter-company funding available to it, is able to minimise its tax payable by adopting these alternatives. Similarly, further tightening of the debt-to-equity ratio to 1:1 (Model 15), as proposed in May 2016[98] would give rise to the same result.

While this may present a counterintuitive outcome given the assumptions traditionally made by policymakers, it confirms the central thesis of this article that thin capitalisation rules are too narrow in scope given the fungibility of inter-company funding alternatives available to an MNE.

VI CONCLUSION

This article highlights the contributions of legal academics and legal professionals in providing input on existing reforms – and examining alternative theoretical approaches to tax policy. Specifically, the two bodies of literature explored in this article are: the thin capitalisation; and, the fundamental reform literature, with the latter culminating in the allowance for corporate equity as implemented in jurisdictions such as Belgium and Italy. This article also bridges these two theoretical approaches in the literature by highlighting the importance – for transparency and good tax design – of starting from economic first principles (as in the ACE literature) to address the shortcomings in the tax treatment of cross-border inter-company funding activities, with a focus on the legal and regulatory design of these rules (which is the focus of the thin capitalisation literature).

In doing so, the author presents an alternative legal-economic approach to taxing multinationals. Specifically, by combining legal analysis with linear optimisation modelling to create the MTP model, this article bridges these two disciplines. This model anticipates the impact of various legislative provisions by simulating a tax-minimising MNE’s cross-border inter-company behavioural responses to various tax regimes.

This article explores two recent tax trends: first, reductions to the headline corporate income tax rate in the UK, Italy and Australia; and second, the implementation of various restrictions on the tax deductibility of corporate interest expense across Belgium, Italy, the UK and Australia. Through analysis of these trends, the MTP model ‘makes the invisible visible’ and gives rise to the following five-fold observations.

First, it is important to consider the impact of corporate tax cuts on inter-company profit shifting activities of tax-minimising MNEs’. Specifically, an unintended consequence may be that the corporate tax revenue base is simply forfeited without increasing investment or impacting preventing profit shifting behaviours.

Second, the model developed in this article challenges the expectation in the literature and the observations of practitioners that an ACE-variant results in a reduction in global tax liability of an MNE compared to a regime with thin capitalisation rules. While this expectation holds in the case of the more tax aggressive MNEs, the modelled Belgian ACE-variant is able to collect either the same or more tax revenue from relatively less tax aggressive MNEs.

Third, a problematic observation arising from comparing the UK’s former WWDC regime with the current fixed ratio rules is that the former better protects the UK’s tax revenue base than the latter, which is more vulnerable to profit shifting.

Fourth, an extended fixed ratio rule, as proposed by this article, gives rise to either equivalent or better tax revenue collection outcomes than utilising the existing fixed ratio rule – and is particularly beneficial for the home jurisdiction.

Finally, many governments’ strategy of simply ‘tightening’ thin capitalisation rules is a largely ineffective tax revenue base protection measure. This is because tax minimising MNEs are likely utilising other forms of inter-company funding beyond traditional debt and equity financing.

Ultimately, it is hoped that this article will present a platform for further discussion on the tax treatment of cross-border inter-company transactions, and facilitate the development of improvements to both the tax design and legislative drafting of rules aimed at limiting base erosion involving interest deductions and other financial payments.

[*] Senior Lecturer, School of Taxation and Business Law (incorporating Atax), UNSW Sydney, BCom(Finance)/LLB(Hons) (UNSW), PhD (UNSW), Solicitor of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, Federal Court and High Court of Australia (non-practising), a.kayis@unsw.edu.au. An earlier version of this article was presented at the University of Cambridge Centre for Tax Law’s Tax Policy Conference: Ann Kayis-Kumar, ‘The Importance of Legal Practitioners and Scholars in Tax Policy Design and Development: An Exploration and Extension of the Legal-Economic Literature’ (Paper presented at the Tax Policy Conference 2017, Centre for Tax Law, University of Cambridge, 11 April 2017). The author is particularly grateful to Dr John Avery Jones, Dr Dominic de Cogan, Professor Maria Cecilia Fregni and Professor Judith Freedman for their helpful comments and support, and to Professor Neil Warren, Professor John Taylor and Professor Michael Walpole for their insights.

[1] John Snape, ‘Corporate Tax Reform – Politics and Public Law’ [2007] British Tax Review 374, 382–3.

[2] International Chamber of Commerce Commission on Taxation and the International Chamber of Commerce Committee on Customs and Trade Regulations, ‘Transfer Pricing and Customs Value’ (Policy Statement Document No 180/103-6-521, February 2012) 2; Kevin S Markle and Douglas A Shackelford, ‘Cross-Country Comparisons of the Effects of Leverage, Intangible Assets, and Tax Havens on Corporate Income Taxes’ (2012) 65 Tax Law Review 415, 432.

[3] Hooi May Hen, Sub-elites as Fiduciary Gatekeepers of Global Elites: A Fiscal Anthropology of the Cayman Islands and Offshore Financial Industry (Master of Arts Thesis, Simon Fraser University, 2015) v.

[4] Miranda Stewart, ‘International Tax, the G20 and the Asia Pacific: From Competition to Cooperation?’ (2014) 1 Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 484, 484.

[5] Irving Fisher, ‘Income in Theory and Income Taxation in Practice’ (1937) 5 Econometrica 1, 1 (emphasis in original):

Originally ‘income’ was probably thought of as simply incoming money. Incoming payments of money naturally appeared in sharp contrast with outgoing payments of money. A business man, in his shop, could easily subtract the outgoings from the incomings, call what was left his ‘net income’, and physically take this ‘net income’ out of his business shop into his home. It was called net income because it was the net money coming in to his home from his business. But today such simple accounting has been superseded, or overlaid, by many complicated procedures; modern accountancy has evolved into an elaborate art. It has done so almost without help from economists. The result is that the chasm between accountancy and economics has become wide.

[6] As observed by Parsons:

it is instructive to consider what is meant by income in the thinking of those economists who identify income with ‘accretions to economic power’. These economists would say that an income tax has a rational and appropriate operation so far as it taxes such accretions, and taxes only such accretions.

R W Parsons, ‘Income Taxation in Australia: Principles of Income, Deductibility and Tax Accounting’ (Digital Text, University of Sydney Library, 2001) [1.45].

[7] Irving Fisher, The Nature of Capital and Income (Macmillan, 1906) 51–2 (emphasis altered). Fisher’s analysis is particularly relevant in the social welfare context, which is beyond the scope of this study.

[8] Robin H Woellner, Trevor J Vella and Lee Burns, Australian Taxation Law (CCH Australia, 4th ed, 1993) 335–6.

[9] Importantly, the courts have emphasised that the judicial notion of income is ‘income according to ordinary concepts and usages of mankind’, which are subject to change over time to reflect changes in society: see Robin Woellner et al, Australian Taxation Law (Oxford University Press, 26th ed, 2016) 111–12.

[10] John Prebble, ‘Income Taxation: A Structure Built on Sand’ (2002) 24 Sydney Law Review 301, 301.

[11] Douglas A Kahn, ‘The Two Faces of Tax Neutrality: Do They Interact or Are They Mutually Exclusive?’ (1990) 18 Northern Kentucky Law Review 1, 1.

[12] Neil Warren, ‘Benchmarking Australia’s Intergovernmental Fiscal Arrangements’ (Final Report, NSW Treasury, 23 May 2006) 58.

[13] Richard A Musgrave and Peggy B Musgrave, Public Finance in Theory and Practice (McGraw-Hill, 2nd ed, 1976) 210.

[14] Institute for Fiscal Studies, Tax by Design: The Mirrlees Review (Oxford University Press, 2011) 40 (‘Mirrlees Review’); see also Warren, above n 12.

[15] Sven-Eric Bärsch, Taxation of Hybrid Financial Instruments and the Remuneration Derived Therefrom in an International and Cross-Border Context: Issues and Options for Reform (Springer, 2012) 45.

[16] Chloe Burnett, ‘Intra-Group Debt at the Crossroads: Stand-Alone versus Worldwide Approach’ (2014) 6 World Tax Journal 40, 44, 63, 67.

[17] Michael J Graetz, ‘A Multilateral Solution for the Income Tax Treatment of Interest Expenses’ (2008) 62 Bulletin for International Taxation 486, 487.

[T]he treatment of cross-border interest payments is now one of the most complex aspects of income tax law. Rules differ among countries and contexts ... because money is fungible, it is difficult in both theory and practice to know the ‘purpose’ of specific borrowing. Nevertheless, many countries attempt to ‘trace’ borrowed funds to their use, creating opportunities for creative tax planning and inducing inevitable disputes between taxpayers and tax collectors.

[18] Ilan Benshalom, ‘Taxing the Financial Income of Multinational Enterprises by Employing a Hybrid Formulary and Arm’s Length Allocation Method’ (2009) 28 Virginia Tax Review 619, 642.

The most startling example is withholding taxes on financial payments. While dividend payments are typically subject to withholding taxes, interest payments and income derived from financial derivatives are typically exempt by double taxation treaties from withholding source taxes. This discontinuity is ridiculous given taxpayers’ ability to replicate equity investments with the use of hybrid financial derivatives.

See also Ilan Benshalom, ‘The Quest to Tax Financial Income in a Global Economy: Emerging to an Allocation Phase’ (2008) 28 Virginia Tax Review 165.

[19] Michael Kobetsky, International Taxation of Permanent Establishments: Principles and Policy (Cambridge University Press, 2011) 266.

The task of objectively determining a particular branch’s equity capital is significant since money is fungible and both equity capital and debt capital may be moved between different parts of an international bank with ease.

See generally H David Rosenbloom, ‘Banes of an Income Tax: Legal Fictions, Elections, Hypothetical Determinations, Related Party Debt’ [2004] SydLawRw 2; (2004) 26 Sydney Law Review 17. Beyond the tax law literature see, eg, ‘we will focus on debt financial structuring by multinationals although some of the analysis we provide could be easily applied to leasing and insurance structuring’: Jack M Mintz and Alfons J Weichenrieder, The Indirect Side of Direct Investment: Multinational Company Finance and Taxation (MIT Press, 2010) 10; see also, ‘[b]ecause the roles of debt, equity, and hybrid debt-equity instruments in the capital structure of the firm are to a significant extent interchangeable ... a formal legal distinction between debt and equity in insider trading law does not make sense’: Alan Strudler and Eric W Orts, ‘Moral Principle in the Law of Insider Trading’ (1999) 78 Texas Law Review 375, 392–3; see also Hui Huang, International Securities Markets: Insider Trading Law in China (Kluwer Law International, 2006) 155.

[20] Martin Barreiro et al, ‘Techniques for Repatriation of Funds’ (Presentation presented at the Baker & McKenzie 11th Annual Latin American Tax Conference, the Biltmore Hotel, Florida, 10–11 March 2010) 7. However, payments for services are beyond the scope of this article given its focus on capital mobility, rather than both capital and labour mobility.

[21] Reuven S Avi-Yonah and Oz Halabi, ‘A Model Treaty for the Age of BEPS’ (Working Paper No 103, University of Michigan Law School, 1 January 2014) 3.

[22] Benshalom, ‘Quest to Tax Financial Income’, above n 18, 193–5; see also Ilan Benshalom, ‘Sourcing the “Unsourceable”: The Cost Sharing Regulations and the Sourcing of Affiliated Intangible-Related Transactions’ (2007) 26 Virginia Tax Review 631.

[23] Benshalom, ‘Sourcing the “Unsourceable”’, above n 22, 660–1.

[24] ‘Hence many finance leases are treated in the same way as other leases, and only a small subset of leases, recharacterised as a sale and loan, are subjected to thin capitalisation rules’: Greenwoods & Herbert Smith Freehills and Herbert Smith Freehills, Submission to the Treasury, Implementing a Diverted Profits Tax, 24 June 2016, 11.

[25] Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards, Changing Banking for Good: Report of the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards – Volume IX: Oral and Written Evidence Taken by Sub-Committees H, I, J and K, House of Lords Paper No 27-IX, House of Commons Paper No 175-IX, Session 2013–14 (2013) H Ev 257.

[26] Burnett, above n 16, 45; Patricia Brown, ‘General Report’ in International Fiscal Association (eds), Studies on International Fiscal Law: The Debt–Equity Conundrum, (Sdu Uitgevers, 2012) vol 97b, 40‑–1.

[27] ‘Hence many finance leases are treated in the same way as other leases, and only a small subset of leases, recharacterised as a sale and loan, are subjected to thin capitalisation rules’: Greenwoods & Herbert Smith Freehills and Herbert Smith Freehills, above n 24.

[28] Richard Vann, ‘Corporate Tax Reform in Australia: Lucky Escape for Lucky Country?’ [2013] British Tax Review 59, 71.

[29] Explanatory Memorandum, New Business Tax System (Thin Capitalisation) Bill 2001 (Cth) 30 [2.7].

[30] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ‘Limiting Base Erosion Involving Interest Deductions and Other Financial Payments – Action 4: 2015 Final Report’ (Final Report, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2015), 47.

[31] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ‘Neutralising the Effects of Hybrid Mismatch Arrangements – Action 2: 2015 Final Report’ (Final Report, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, 2015).

[32] Burnett, above n 16, 65, and studies cited therein.

[33] See, eg, Antony Ting, ‘Base Erosion by Intra-group Debt and BEPS Project Action 4’s Best Practice Approach – A Case Study of Chevron’ [2017] British Tax Review 80, 90.

[34] See C John Taylor, ‘Approximating Capital-Export Neutrality in Imputation Systems: Proposal for a Limited Exemption Approach’ (2003) 57 Bulletin for International Taxation 135; C John Taylor, ‘Development of and Prospects for Corporate-Shareholder Taxation in Australia’ (2003) 57 Bulletin for International Taxation 346.

[35] Importantly, the Henry Review criticised Australia’s current treatment of foreign debt as complex and distortionary, recommending a reduction in the interest withholding tax rate to zero among tax treaty partners. With an effective interest withholding tax rate of 3.5 per cent, liability for withholding tax would likely not outweigh the advantages of interest deductibility given comparative levels of corporate tax. While the literature has recognised the debt bias as prevalent in the foreign debt context, policymakers have called for the reduction of interest withholding tax to 0 per cent provided appropriate safeguards exist to limit tax avoidance: ‘Recommendation 34: Consideration should be given to negotiating, in future tax treaties or amendments to treaties, a reduction in interest withholding tax to zero so long as there are appropriate safeguards to limit tax avoidance’: Commonwealth, Australia’s Future Tax System Review, Australia’s Future Tax System: Report to the Treasurer (Treasury, 23 December 2009) 87 (‘Henry Review’).

[36] Stuart Webber, ‘Thin Capitalization and Interest Deduction Rules: A Worldwide Survey’ (2010) 60 Tax Notes International 683.

[37] Adrian O’Shannessy and Ryan Leslie, ‘Top 10 Tax Developments in 2015’ (Report, Greenwoods & Herbert Smith Freehills, 22 December 2015) 3 <http://www.greenwoods.com.au/media/1732/top-10-tax-developments-2015.pdf> .

[38] Reuven S Avi-Yonah and Kimberly Clausing, ‘A Proposal to Adopt Formulary Apportionment for Corporate Income Taxation: The Hamilton Project’ (Law & Economics Working Paper No 70, University of Michigan Law School, April 2007) 9; President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform, ‘Sixth Meeting’ (Transcript, March 31 2005) 12 (Willard Taylor).

[39] Kerrie Sadiq, Adrian Sawyer and Bronwyn McCredie, ‘Tax Design and Administration in a Post – BEPS Era: A Study of Key Reform Measures in 16 Countries’ (Working Paper, 2018) 18; Ann Kayis-Kumar, ‘Thin Capitalisation Rules: A Second-Best Solution to the Cross-Border Debt Bias?’ (2015) 30 Australian Tax Forum 299.

[40] Australian Taxation Office, Income Tax: Where There Is No Excess Debt under Division 820 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 Can the Transfer Pricing Provisions Apply to Adjust the Pricing of Costs That May Become Debt Deductions, For Example, Interest and Guarantee Fees?, TD 2007/D20, 28 November 2007.

[41] Australian Taxation Office, Income Tax: The Interaction of Division 820 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 and the Transfer Pricing Provisions in Relation to Costs That May Become Debt Deductions, For Example, Interest and Guarantee Fees, TR 2009/D6, 16 December 2009.

[42] Australian Taxation Office, Income Tax: The Interaction of Division 820 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 and the Transfer Pricing Provisions, TR 2010/7, 27 October 2010.

[43] Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (No 4) [2015] FCA 1092; (2015) 102 ATR 13 (‘Chevron’).

[44] For example, regulations can currently be made to further specify what falls within the scope of a ‘debt deduction’ and a ‘financial benefit’: Australian Taxation Office, Income Tax: What Type of Costs are Debt Deductions within Scope of Subparagraph 820-40(1)(a)(iii) of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997?, TD 2018/D5, 1 August 2018.

[45] ‘For very difficult and complex problems ... [intransitive laws] grant agency officials limited discretion to decide about initial measures to take, and to introduce new measures as they gain experience’: Ann Seidman, Robert B Seidman and Nalin Abeyesekere, Legislative Drafting for Democratic Social Change: A Manual for Drafters (Kluwer Law International, 2001) 157; see also Stanley S Surrey, ‘Complexity and the Internal Revenue Code: The Problem of the Management of Tax Detail’ (1969) 34 Law and Contemporary Problems 673, 695–7, 699–700.

[46] John Avery Jones, ‘Tax Law: Rules or Principles?’ (1996) 17(3) Fiscal Studies 63, 87–8.

[47] Ibid 80.

[48] Graham Hill, ‘The Judiciary and its Role in the Tax Reform Process’ (1999) 2 Journal of Australian Taxation 66, 79–80.

[49] For a detailed longitudinal, legal analysis of ACE-variants in practice, see Ann Kayis-Kumar, Taxing Multinationals: Preventing Tax Base Erosion through the Reform of Cross-Border Intercompany Deductions (Oxford University Press, 2019).

[50] The Belgian NID (otherwise known as the ‘Intérêts notionnels et déduction fiscales pour capital à risque’, ‘Notionele Interestaftrek’ or ‘Risk Capital Deduction’) allows a deduction for the notional cost of equity by multiplying the notional interest rate with the adjusted equity balance. The notional interest rate is based on the average 10-year government bond rate. For qualifying small to medium-sized enterprises the notional interest rate is increased by 0.5 per cent. The adjusted equity balance corresponds to the accounting equity balance, as listed on the non-consolidated accounts, adjusted to prevent double counting and potential misuses. However, this calculation has received much criticism in the literature, including that companies do not need to generate new investments to benefit from the Belgian NID.

[51] Marc Quaghebeur, ‘Belgium Targets Risk Capital Deduction Abuses’ (2007) 48 Tax Notes International 627, 627.

[52] Marcel Gerard, ‘Belgium Moves to Dual Allowance for Corporate Equity’ (2006) 64 European Taxation 156, 158–9; André Decoster, Marcel Gerard and Christian Valenduc, ‘Tax Revenue and Tax Policy: A Decade of Tax Cuts’ in Etienne De Callataÿ and Françoise Thys-Clément (eds), The Return of the Deficit: Public Finance in Belgium over 2000–2010 (Leuven University Press, 2012) 95, 111–12.

[53] Decoster, Gerard and Valenduc, above n 52, 112.

[54] Belgium, Full Report with a Summary Record of Translated Interventions, House of Representatives, 2 June 2005, Document No CRIV 51 PLEN 143 [author’s trans] [15.01], 58–9. See also Loi Instaurant une Déduction Fiscale pour Capital à Risque [Law Introducing a Tax Deduction for Risk] (Belgium) Moniteur Belge [No 2005003577] (‘Originating legislation for the Belgian ACE’).

[55] Nicolas Themelin, The Only Consequence of the Announcement Effects of Notional Interest: The Legal Uncertainty (19 September 2013) Afshrift <www.afschrift.com>.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Disposizioni di attuazione dell'articolo 1 del decreto-legge 6 dicembre 2011, n 201 concernente l’Aiuto alla crescita economica (Ace) [Provisions for the implementation of article 1 of Decree-Law of 6 December 2011, No. 201 concerning the Aid for economic growth (Ace)] (Italy) 14 March 2012, Gazzetta Ufficiale, 12A03200 (‘Italian Official Gazette’) [author’s trans].

[58] Nicola Branzoli and Antonella Caiumi, ‘How Effective is an Incremental ACE in Addressing the Debt Bias? Evidence from Corporate Tax Returns’ (Working Paper No 72, Taxation Papers, European Commission, 2 January 2018).

[59] Marco Manzo and Maria Teresa Monteduro, ‘From IRAP to CBIT: Tax Distortions and Redistributive Effects’ (Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper No 28070, 13 August 2010) 5.